Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: In recent decades, climate change has increasingly concerned the scientific community not only due to its environmental impact but also due to its direct and indirect impact to human health. The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the current evidence on the impacts of several climate parameters -such as temperature, floods, humidity, air pollution, wildfires and dust- on human health in terms of both mortality and morbidity. Methods: Systematic search for observational studies on climate change effect on human mortality and morbidity published in the last ten years in PubMed, EBSCOhost and Scopus. Results: A total of 57 articles were included in this systematic review. A positive association between extreme heat/cold events, temperature variation and air pollution with mortality was reported from most studies. Moreover, floods might be associated with infant mortality. Cardiovascular diseases are attributed to extreme temperature conditions and humidity is linked to cardiovascular diseases. The chronic exposure to air pollution is strongly associated with respiratory diseases. Floods and wildfires cause mainly respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses, while dust exacerbates respiratory diseases like asthma. Conclusions: The data derived from the studies confirm the significant impact of temperature, air pollution, humidity, floods, wildfires and dust on both physical and mental health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

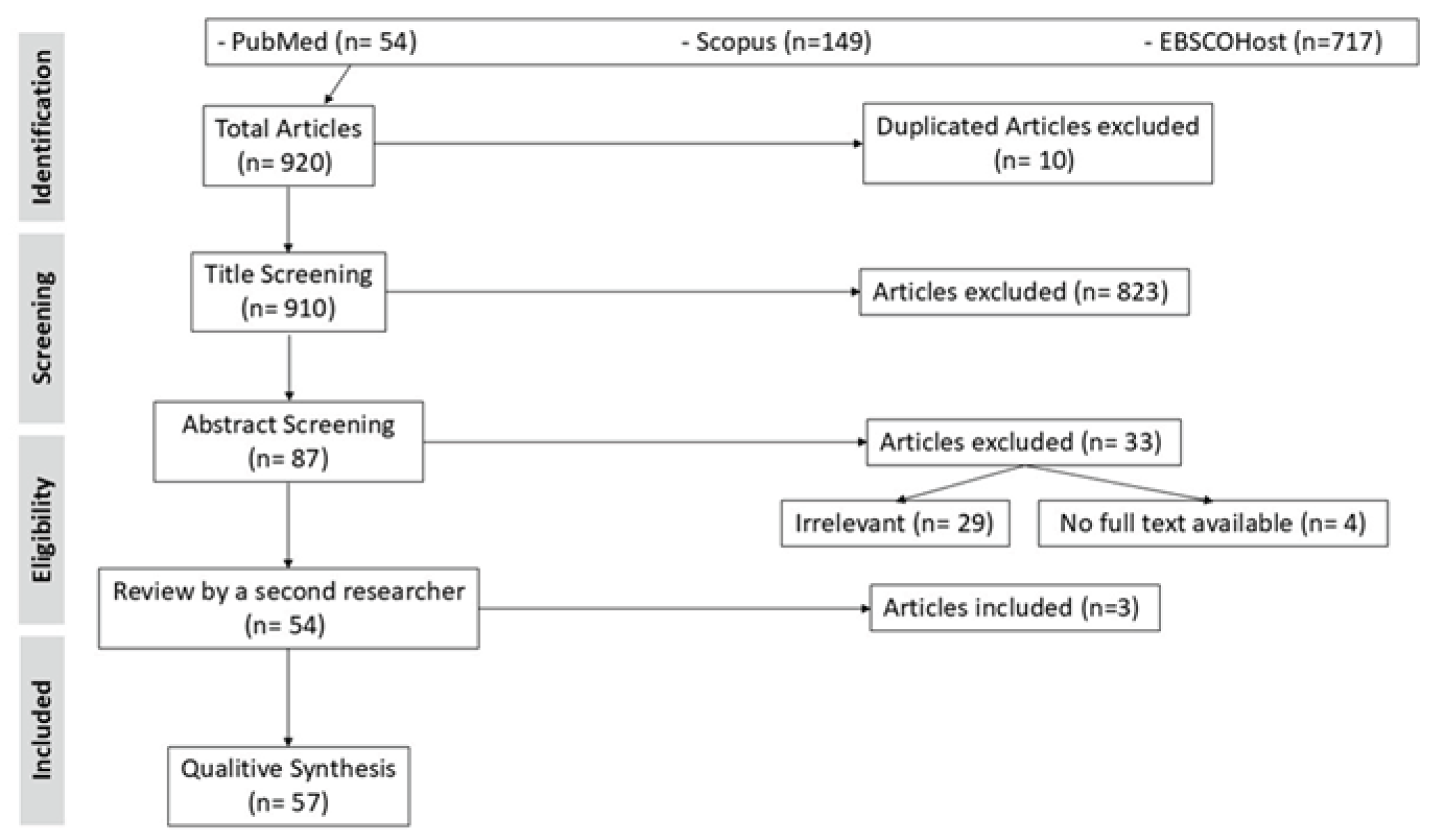

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Screening Criteria

- Types of studies: Observational studies written in English which were published in peer-reviewed journals.

- Publication period: between January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2024.

- Types of exposures: Studies on the health effects of extreme weather events, such as extreme temperature, HWs, cold waves, droughts, dust, floods, storms and wildfires were included.

- Types of outcomes: Health outcomes including total mortality, cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, respiratory mortality and morbidity, and mental health were considered. Food- and water-borne infectious diseases were also included as they might be highly relevant to direct post-flood mortality and morbidities. [24]

- Study type: Reviews, letters to the editor, or opinion papers

- Publication date: Published before 2015

2.3. Quality Appraisal of Studies

3. Results

3.1. Data Management

3.2. Quality Appraisal of the Included Studies

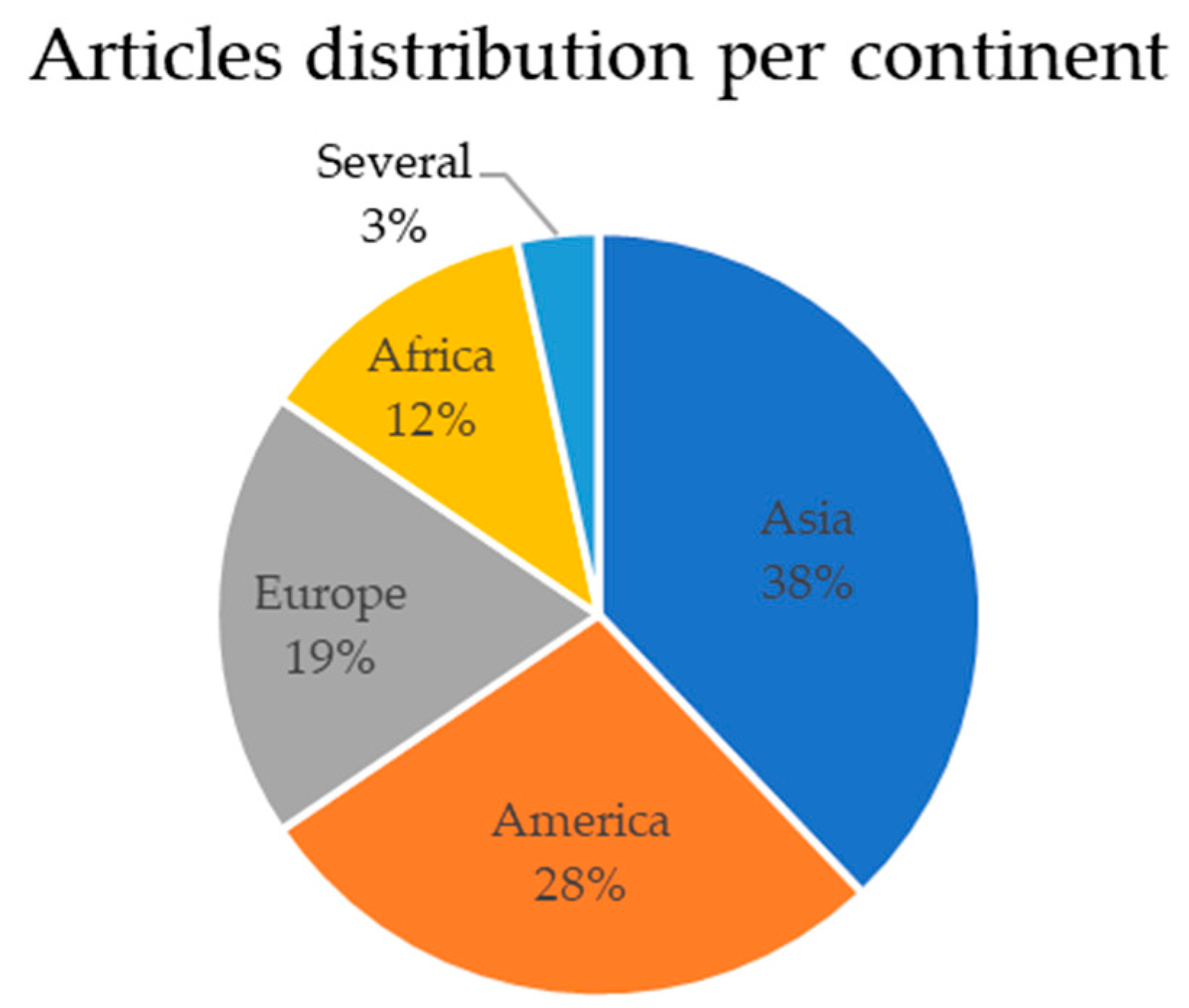

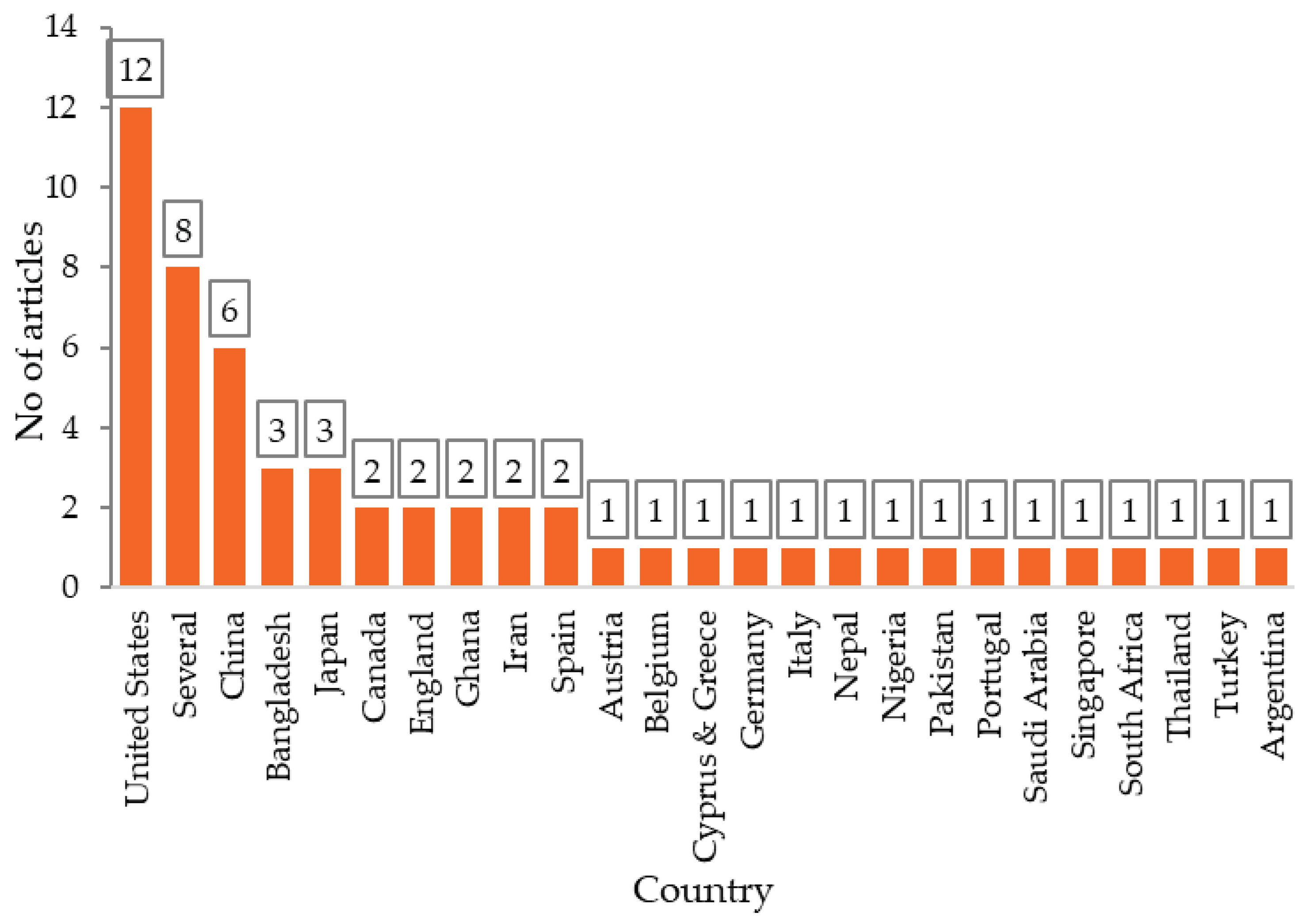

3.3. Characteristics of Included Studies

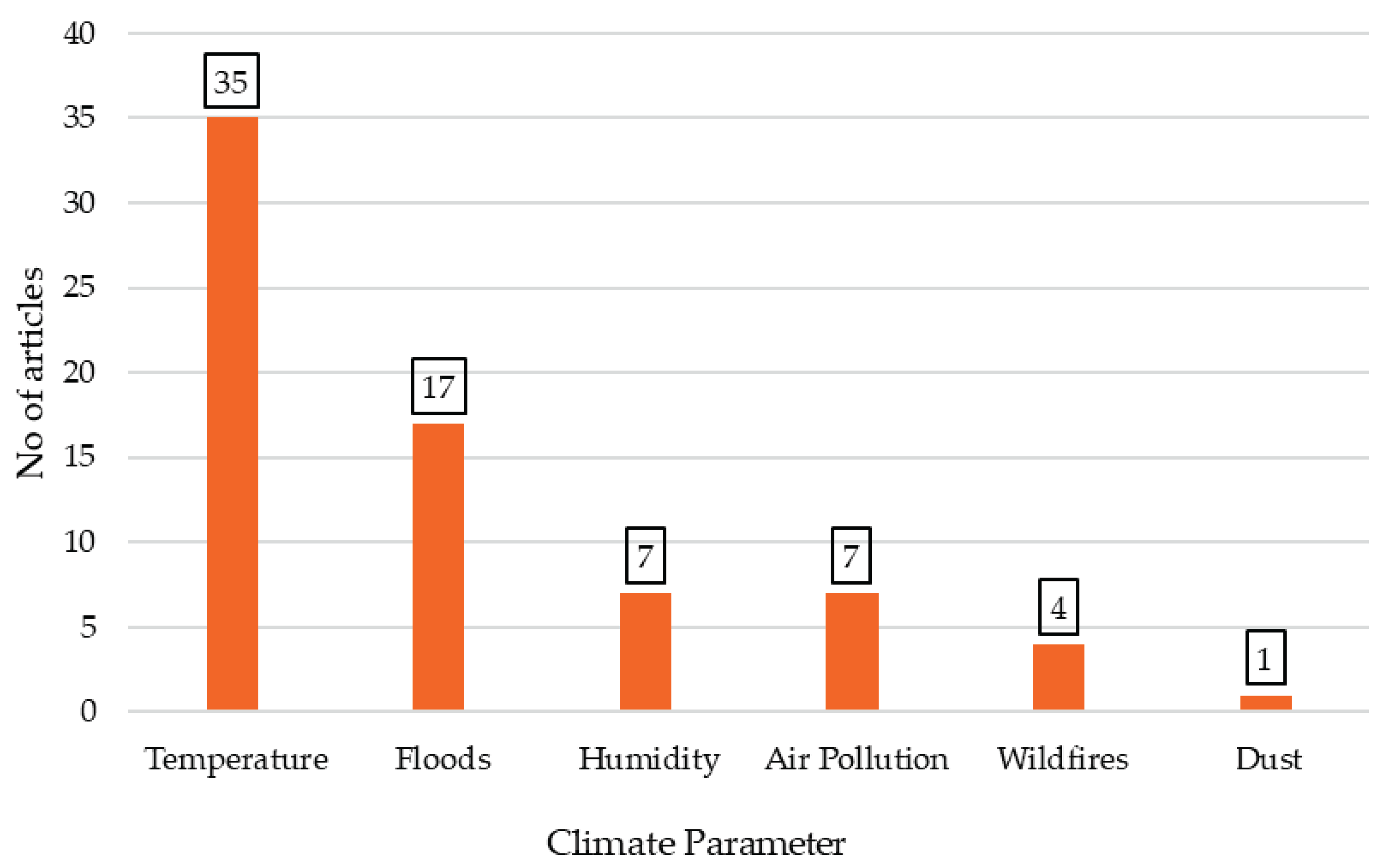

3.4. Distribution of Articles Based on Climate Parameter

3.4.1. Temperature

3.4.2. Air Pollution

3.4.3. Wildfires

3.4.4. Dust

3.4.5. Floods

3.4.6. Humidity

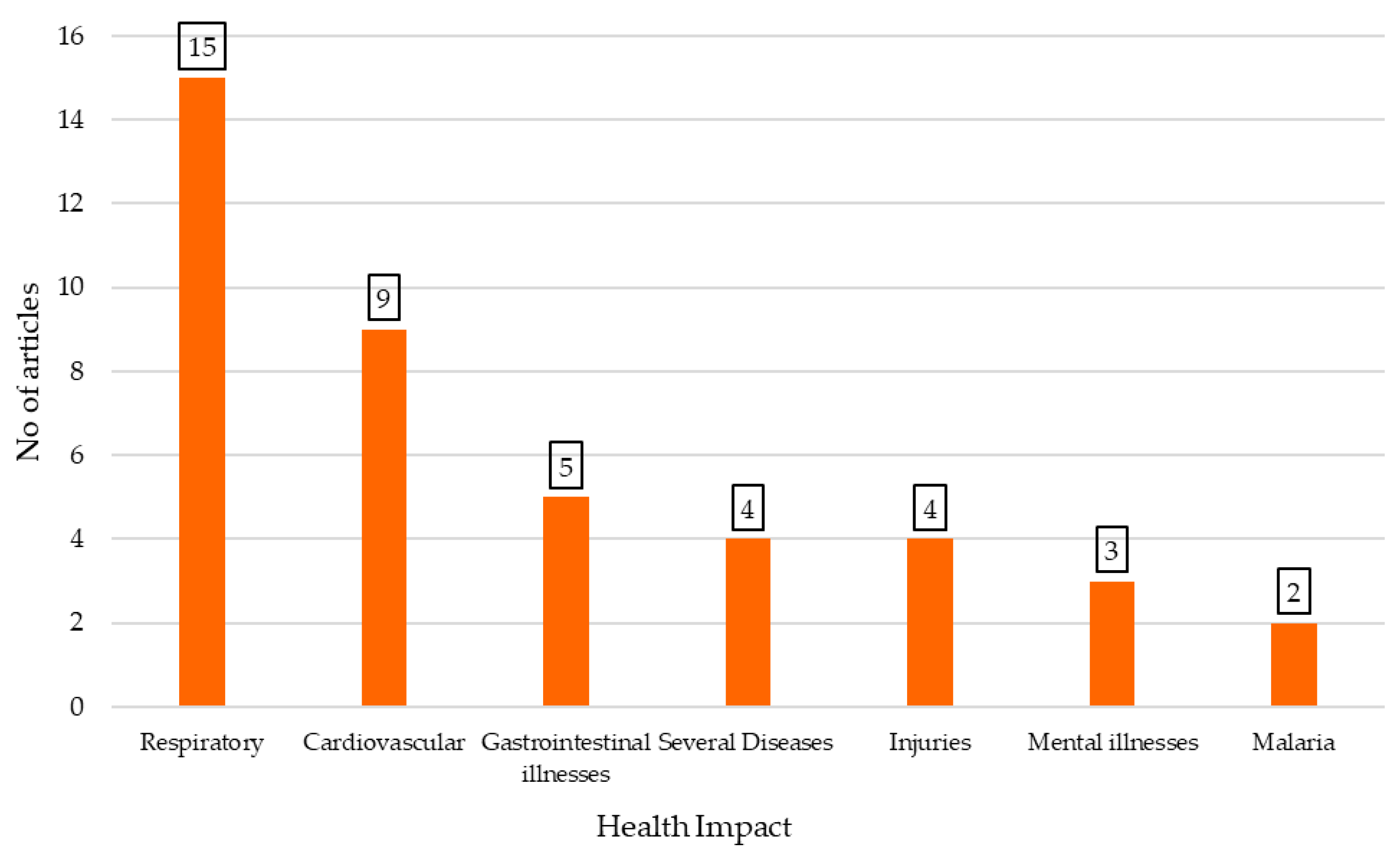

3.5. Classification of Articles by Health Outcomes: Mortality and Morbidity

3.5.1. Mortality

3.5.2. Morbidity

Cardiovascular Morbidity

Respiratory Morbidity

Gastrointestinal Disease

Mental Illnesses

Data on Climate Change and Injuries

Heat Illnesses

Malaria

Data on Climate Change and Additional Health Conditions

4. Discussion

Molecular Mechanisms Linking Climate-Related Environmental Stressors to Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality

Novel Findings on Health Impacts and Inequities in the Climate Crisis

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary lung disease |

| WHO | World health organization |

| DDS | Desert dust storms |

| PRISMA | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses |

| ED | Emergency department |

| STEMI | ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

| AMI | Acute myocardial infarction |

| CO | Carbon oxides |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| CMDs | Common mental disorders |

| HWs | Heat waves |

| HE | Heat exhaustion |

| NO2 | Nitrogen dioxide |

| OHCA | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest |

| EHIs | Exertional heat illnesses |

| MNH | Maternal and newborn healthcare |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

References

- Bhatta, K. , Pahari, S. ; Vulnerability to Heat Stress and its Health Effects among People of Nepalgunj Sub-Metropolitan. J. Nepal Health Res. Counc. 2020, 18, 763–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Sutherland, M.; Raslan, Sh.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Natural Disasters Related Traumatic Injuries/ Fatalities in the United States and Their Impact on Emergency Preparedness Operations. J. Trauma Nurs. 2021, 28, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; He, Ch.; Kim, H.; Honda, Y.; Lee, Wh.; Hashizume, M.; Chen, R.; Kan, H. The burden of heat-related stroke mortality under climate change scenarios in 22 East Asian cities. Environment International 2022, 170, 107602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Evelyn, S.M.; Jung, J.; Alvarado, E.; Baumgartner, J.; Caligiuri, P.; Hagmann, R.K.; Henderson, S.B.; Hessburg, P.F.; Hopkins, S.; Kasner, E.J.; et al. Wildfire, Smoke Exposure, Human Health, and Environmental Justice Need to be Integrated into Forest Restoration and Management. Current Environmental Health Reports 2022, 9, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Jin, Y.; Scaduto, E.; Moritz, M. A.; Goulden, M. L.; Randerson, J.T. Climate, fuel, and land use shaped the spatial pattern of wildfire in California’s Sierra Nevada. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2021, 126, e2020JG005786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Li, M.; Montgomery, S.; Fang, B.; Wang, Ch.; Xia, T.; Cao, Y. Short-Term Associations of Fine Particulate Matter and Synoptic Weather Types with Cardiovascular Mortality: An Ecological Time-Series Study in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez, P.D.; Ramesh, A.; Hood, D.B.; Alcendor, D.J.; R. Valdez, B.; Aramandla, M.P.; Tabatabai, M.; Matthews-Juarez, P.; Langston, M.A.; Al-Hamdan, M.Z. The effects of air pollution, meteorological parameters, and climate change on COVID-19 comorbidity and health disparities: A systematic review. Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology 2022, 4, 194–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Su, B.B.; Xue, L.; Xie, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Dong, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, M.; Song, Y.; Ma, J. ; Zheng. X. Temperature variability and common diseases of the elderly in China: a national cross-sectional study. Environmental Health. [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Kliengchuay, W. , Suwanmaneed, S.; Aung H.W.; Sahanavine, N.; Siriratruengsukf, W.; Kawichaig, S.; Tawatsupah, B.; Xua, R.; Lia, Sh.; Guoa, Y.; Tantrakarnapa, K. Association of cause-specific hospital admissions with high and low temperatures in Thailand: a nationwide time series study. The lancet 2024, 46, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yussuf, E.; Muthama, J.N.; Mutai, B.; Marangu, D.M. Impacts of air pollution on pediatric respiratory infections under a changing climate in Kenyan urban cities. East African Journal of Science, Technology and Innovation. [CrossRef]

- Onozuka, D.; Hagihara, A. Extreme temperature and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Japan: A nationwide, retrospective, observational study. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 575, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Ch.; Yin, P.; Chen, R.; Gao, Y.; Liu, W.; Schneider, A.; Bell, M.L.; Kan, H.; Zhou, M. Cause-specific accidental deaths and burdens related to ambient heat in a warming climate: A nationwide study of China. Environment International 2023, 180, 108231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.A.; Vargo, J.; Milet, M.; French, N.H.F.; Billmire, M.; Johnson, J.; Hoshiko, S. The San Diego 2007 wildfires and Medi-Cal emergency department presentations, inpatient hospitalizations, and outpatient visits: An observational study of smoke exposure periods and a bidirectional case-crossover analysis. PLoS Med 2018, 15, 1002601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blando, J.; Allen, M.; Galadima, H.; Tolson, T.; Akpinar-Elci, M.; Szklo-Coxe, M. Observations of Delayed Changes in Respiratory Function among Allergy Clinic Patients Exposed to Wildfire Smoke. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouis, P.; Papatheodorou, S.I.; Kakkoura, M.G.; Middleton, N.; Galanakis, E.; Michaelidi, E.; Achilleos, S.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Neophytou, M.; Stamatelatos, G.; et al. The MEDEA childhood asthma study design for mitigation of desert dust health effects: implementation of novel methods for assessment of air pollution exposure and lessons learned. BMC Pediatrics 2021, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunene, Z.; Kapwata, Th.; Mathee, A.; Sweijd, N.; Minakawa, N.; Naidoo, N.; Wright, C.Y. Exploring the Association between Ambient Temperature and Daily Hospital Admissions for Diarrhea in Mopani District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadia, M.; Heidari, H.; Charkhloo, E.; Dehghani, A. Heat stress and physiological and perceptual strains of date harvesting workers in palm groves in Jiroft. Work 2020, 66, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherratt, S. Hearing Loss and Disorders: The Repercussions of Climate Change. American Journal of Audiology 2023, 32, 793–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, L.; Sturm, R. Mortality in extreme heat events: an analysis of Los Angeles County Medical Examiner data. Public Health 2024, 236, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiman, L.; Anderson, H.; Tomasallo, C. Hypothermia-Related Deaths — Wisconsin, 2014, and United States, 2003–2013. Morbidity and Mortality. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015, 64, 141–143. [Google Scholar]

- Tabassum, Sh.; Raza, N.; Shah, S.Zh. Outcome of heat stroke patients referred to a tertiary hospital in Pakistan: a retrospective study. EMHJ 2019, 25, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, A.; Malilay, J.; Schramm, P.; Saha, Sh. Heat-Related Deaths — United States, 2004–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020, 69, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oheneba Dornyo, T.V.; Amuzu, S.; Maccagnan, A.; Taylor, T. Estimating the Impact of Temperature and Rainfall on Malaria Incidence in Ghana from 2012 to 2017. Environmental Modeling & Assessment 2022, 27, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, K.; Turner, L.A.; & Tong, Sh.; Tong, Sh. Floods and human health: A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2012, 47, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achebak, H.; Devolder, D.; Ballester, J. Heat-related mortality trends under recent climate warming in Spain: A 36-year observational study. PLOS Medicine 2018, 15, e1002617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alho, A.M.; Oliveira, A.P.; Viegas, S.; Nogueira, P. Effect of heatwaves on daily hospital admissions in Portugal, 2000–18: an observational study. The Lancet Planetary Health 2024, 8, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafoggia, M.; de’ Donato, F.; Ancona, C.; Ranzi, A.; Michelozzi, P. Health impact of air pollution and air temperature in Italy: evidence for policy actions. Epidemiol Prev. 2023, 47, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, H.K.; Andrews, N.; Armstrong, B.; Bickler, G.; Rebody, R. Mortality during the 2013 heatwave in England – How did it compare to previous heatwaves? A retrospective observational study. Environmental Research 2016, 147, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, A.; Tomlins, K.; Sanni, L.; Omohimi, C.; Thomas, F.; Tran, Th. Exposure to air pollutants and heat stress among resource-poor women entrepreneurs in small-scale cassava processing. Environ. Monit. Assess 2019, 191, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figgs, L.W. Emergency department asthma diagnosis risk associated with the 2012 heat wave and drought in Douglas County NE, USA Heart & Lung 2019, 48, 250257. [CrossRef]

- Figgs, L.W. Elevated chronic bronchitis diagnosis risk among women in a local emergency department patient population associated with the 2012 heatwave and drought in Douglas County, NE USA. Heart & Lung 2020, 49, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawiah, K.; Asosega, K.A.; Ansah, R.K.; Appiah, S.T.; Otoo, D.; Aponye, I.A.; Tinbil, T.; Addai, I.M. Confirmed Malaria Cases in Children under Five Years: The Influence of Suspected Cases, Tested Cases, and Climatic Conditions. Health & Social Care in the Community. [CrossRef]

- Oray, N.C.; Oray, D.; Aksay, E.; Atilla, R.; Bayram, B. The impact of a heat wave on mortality in the emergency department. Medicine 2018, 97, 13815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, V.; Breitner-Busch, S.; He, Ch.; Matthies-Wiesler, F.; Peters, A.; Schneider, A. Heat-Related Mortality in the Extreme Summer of 2022. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2024, 121, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesini, F. , Herrera, N.; Maria de Los Milagros Skansi, M.; Carolina González Morinigo, C.G.; Fontán, S.; Savoy, F.; Ernesto de Titto, E. Mortality risk during heat waves in the summer 2013-2014 in 18 provinces of Argentina: Ecological study. Cien Saude Colet 2022, 27, 2071–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparrini, A.; Guo, Y.; Hashizume, M.; Lavinge, E.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J.; Tobias, A.; Tong, Sh.; Rocklöv, J.; Forsberg, B.; et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. The Lancet 2015, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogne, T.; Wang, R.; Wang, P.; Deziel, N.C.; Metayer, C.; Wiemels, J.L.; Chen, K.; Warren, J.L.; Ma, X. High ambient temperature in pregnancy and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: an observational study. The Lancet Planetary Health 2024, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H.; Bao, W.; Lou, P.; Chen, P.; Zhang, P.; Chang, G.; Hu, X.; Zhao, X.; Huang, S.; Yang, Y. Relationship between temperature and acute myocardial infarction: a time series study in Xuzhou, China, from 2018 to 2020. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.S.; Jin, D.H.; Ma, W.J.; Liu, T.; Xu, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.E.; Zhou, Ch. L. The Impact of Non-optimum Ambient Temperature on Years of Life Lost: A Multi-county Observational Study in Hunan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienbacher, C.L.; Kaltenberger, R.; Schreiber, W.; Tscherny, K.; Fuhrmann, V.; Roth, D.; Herkner, H. Extreme weather conditions as a gender-specific risk factor for acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 43, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, H.; Hattori, S.; Yoshida, K.; Maeda, H.; Kitamura, T.; Morii, E. Association of atmospheric temperature with out-of-hospital natural deaths occurrence before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Osaka, Japan. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 18529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aik, J.; Onga, J.; Ng, L.Ch. The effects of climate variability and seasonal influence on diarrhoeal disease in the tropical city-state of Singapore – A time-series analysis. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 2020, 227, 11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidnezhad, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Ghavamabadi, L.I. , The role of ambient parameters on transmission rates of the COVID-19 outbreak: A machine learning model. Work 2021, 70, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelieveld, J.; Haines, A.; Burnett, R.; Tonne, C.; Klingmüller, K.; Münzel, T.; Pozzer, A. Air pollution deaths attributable to fossil fuels: observational and modelling study. BMJ 2023, 383, 077784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoran, M.A.; Savastru, R.S.; Savastru, D.M.; Tautan, M.N. Peculiar weather patterns effects on air pollution and COVID-19 spread in Tokyo metropolis. Environmental Research 2023, 228, 115907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsiak, J.; Pinault, L.; Christidis, T.; Burnett, R.T.; Abrahamowicz. M.; Weichenthal, Sc. Long-term exposure to wildfires and cancer incidence in Canada: a population-based observational cohort study. The Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, E.N.; Jain, S.; Higa, J.; Fontenot, J.; Bertolucci, R.; Huynh, Th.; Hammer, G.; Brodkin, A.; Thao, M. , Brousseau, B. ; et al. Outbreak of Norovirus Illness Among Wildfire Evacuation Shelter Populations — Butte and Glenn Counties, California, Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2018, 69, 613–617. [Google Scholar]

- Baten, A.; Wallemacq, P.; Loenhout, J.A.; Guha-Sapir, D. Impact of Recurrent Floods on the Utilization of Maternal and Newborn Healthcare in Bangladesh Matern Child. Health J. 2020, 24, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, Z.S.; Parrish, C.; Sabbatini, A.K.; et al. Emergency Care, Hospitalization Rates, and Floods JAMA Netw. 2025, 8, 250371. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; He, Ch.; Bachwenkizi, J.; Fatmi, Z.; Zhou, L.; Lei, J.; Liu, C.; Kan, H.; Chen, R. Burden of infant mortality associated with flood in 37 African countries. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 10171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamos, I.; Diakakis, M. ; Mapping Flood Impacts on Mortality at European Territories of the Mediterranean Region within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Framework. Water 2024, 16, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, B.; Kunawotor, M.E.; Appiah-Konadu, P. Mortality rate and life expectancy in Africa: the role of flood occurrence. International Journal of Social Economics 2023, 50, 910–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerolle, F.; Arnolda, B.F.; Benmarhnia, T. ; Excess risk in infant mortality among populations living in flοod-prone areas in Bangladesh: A cluster-matched cohort study over three decades, 1988 to 2017. PNAS 2023, 120, 2218789120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, R.; Baldassarre, G.D.; Brandimarte, L.; Wesselink, A. The interplay between structural flood protection, population density, and flood mortality along the Jamuna River, Bangladesh. Regional Environmental Change 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.; White, P.; Cotton, J.; McManus, S. Flood- and Weather-Damaged Homes and Mental Health: An Analysis Using England’s Mental Health Survey. Int. J. Environ Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwer, L.M.; Jonkman, S.N. Global mortality from storm surges is decreasing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 014008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. , Liu, Zh.; Ding, G.; Jiang, B. Projected burden of disease for bacillary dysentery due to flood events in Guangxi, China. Sci. Total Environ. 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanasse, A.; Cohen, A.; Courteau, J.; Bergeron, P.; Dault, R.; Gosselin, P.; Blais, C.; Bélanger, D.; Rochette, L.; Chebana, F. Association between Floods and Acute Cardiovascular Diseases: A Population-Based Cohort Study Using a Geographic Information System Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele-Eich, I.; Burkart, K.; Simmer. C.; Trends in Water Level and Flooding in Dhaka, Bangladesh and Their Impact on Mortality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1196–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yezli, S.; Ehaideb, S.; Yassin, Y.; Alotaibi, B.; Bouchama, A. Escalating climate-related health risks for Hajj pilgrims to Mecca. Journal of Travel Medicine 2024, 31, 042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripp, B.L.; Eberman, L.E.; Smith, M.S. ; Exertional Heat Illnesses and Environmental Conditions During High School Football Practices. Am. J. Sports Med. 2015, 43, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achebak, H.; Rey; G. , Lloyd, S.L.; Quijal-Zamorano, M.; Méndez-Turrubiates R.F.; Joan Ballester, J. Drivers of the time-varying heat-cold-mortality association in Spain: A longitudinal observational study. Environment International 2023, 182, 108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. 2023.

- WHO. Climate Change and Health. /: Organization, 2021. https, 2021.

- Romanello M, McGushin A, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, Hughes N, Jamart L, Kennard H, Lampard P, Solano Rodriguez B, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Cai W, Campbell-Lendrum D, Capstick S, Chambers J, Chu L, Ciampi L, Dalin C, Dasandi N, Dasgupta S, Davies M, Dominguez-Salas P, Dubrow R, Ebi KL, Eckelman M, Ekins P, Escobar LE, Georgeson L, Grace D, Graham H, Gunther SH, Hartinger S, He K, Heaviside C, Hess J, Hsu SC, Jankin S, Jimenez MP, Kelman I, Kiesewetter G, Kinney PL, Kjellstrom T, Kniveton D, Lee JKW, Lemke B, Liu Y, Liu Z, Lott M, Lowe R, Martinez-Urtaza J, Maslin M, McAllister L, McMichael C, Mi Z, Milner J, Minor K, Mohajeri N, Moradi-Lakeh M, Morrissey K, Munzert S, Murray KA, Neville T, Nilsson M, Obradovich N, Sewe MO, Oreszczyn T, Otto M, Owfi F, Pearman O, Pencheon D, Rabbaniha M, Robinson E, Rocklöv J, Salas RN, Semenza JC, Sherman J, Shi L, Springmann M, Tabatabaei M, Taylor J, Trinanes J, Shumake-Guillemot J, Vu B, Wagner F, Wilkinson P, Winning M, Yglesias M, Zhang S, Gong P, Montgomery H, Costello A, Hamilton I. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet 2021, 398, 1619–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bouchama A, Knochel JP. Heat stroke. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346, 1978–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicedo-Cabrera AM, Scovronick N, Sera F, Royé D, Schneider R, Tobias A, Astrom C, Guo Y, Honda Y, Hondula DM, Abrutzky R, Tong S, de Sousa Zanotti Stagliorio Coelho M, Saldiva PHN, Lavigne E, Correa PM, Ortega NV, Kan H, Osorio S, Kyselý J, Urban A, Orru H, Indermitte E, Jaakkola JJK, Ryti N, Pascal M, Schneider A, Katsouyanni K, Samoli E, Mayvaneh F, Entezari A, Goodman P, Zeka A, Michelozzi P, de'Donato F, Hashizume M, Alahmad B, Diaz MH, De La Cruz Valencia C, Overcenco A, Houthuijs D, Ameling C, Rao S, Ruscio FD, Carrasco-Escobar G, Seposo X, Silva S, Madureira J, Holobaca IH, Fratianni S, Acquaotta F, Kim H, Lee W, Iniguez C, Forsberg B, Ragettli MS, Guo YLL, Chen BY, Li S, Armstrong B, Aleman A, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, Dang TN, Dung DV, Gillett N, Haines A, Mengel M, Huber V, Gasparrini A. The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change. Nat Clim Chang. 2021, 11, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Åström DO, Forsberg B, Rocklöv J. Heat wave impact on morbidity and mortality in the elderly population: a review of recent studies. Maturitas 2011, 69, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Beagley J, Belesova K, Boykoff M, Byass P, Cai W, Campbell-Lendrum D, Capstick S, Chambers J, Coleman S, Dalin C, Daly M, Dasandi N, Dasgupta S, Davies M, Di Napoli C, Dominguez-Salas P, Drummond P, Dubrow R, Ebi KL, Eckelman M, Ekins P, Escobar LE, Georgeson L, Golder S, Grace D, Graham H, Haggar P, Hamilton I, Hartinger S, Hess J, Hsu SC, Hughes N, Jankin Mikhaylov S, Jimenez MP, Kelman I, Kennard H, Kiesewetter G, Kinney PL, Kjellstrom T, Kniveton D, Lampard P, Lemke B, Liu Y, Liu Z, Lott M, Lowe R, Martinez-Urtaza J, Maslin M, McAllister L, McGushin A, McMichael C, Milner J, Moradi-Lakeh M, Morrissey K, Munzert S, Murray KA, Neville T, Nilsson M, Sewe MO, Oreszczyn T, Otto M, Owfi F, Pearman O, Pencheon D, Quinn R, Rabbaniha M, Robinson E, Rocklöv J, Romanello M, Semenza JC, Sherman J, Shi L, Springmann M, Tabatabaei M, Taylor J, Triñanes J, Shumake-Guillemot J, Vu B, Wilkinson P, Winning M, Gong P, Montgomery H, Costello A. The 2020 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet 2021, 397, 129–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Romanello M, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, Green C, Kennard H, Lampard P, Scamman D, Arnell N, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Ford LB, Belesova K, Bowen K, Cai W, Callaghan M, Campbell-Lendrum D, Chambers J, van Daalen KR, Dalin C, Dasandi N, Dasgupta S, Davies M, Dominguez-Salas P, Dubrow R, Ebi KL, Eckelman M, Ekins P, Escobar LE, Georgeson L, Graham H, Gunther SH, Hamilton I, Hang Y, Hänninen R, Hartinger S, He K, Hess JJ, Hsu SC, Jankin S, Jamart L, Jay O, Kelman I, Kiesewetter G, Kinney P, Kjellstrom T, Kniveton D, Lee JKW, Lemke B, Liu Y, Liu Z, Lott M, Batista ML, Lowe R, MacGuire F, Sewe MO, Martinez-Urtaza J, Maslin M, McAllister L, McGushin A, McMichael C, Mi Z, Milner J, Minor K, Minx JC, Mohajeri N, Moradi-Lakeh M, Morrissey K, Munzert S, Murray KA, Neville T, Nilsson M, Obradovich N, O'Hare MB, Oreszczyn T, Otto M, Owfi F, Pearman O, Rabbaniha M, Robinson EJZ, Rocklöv J, Salas RN, Semenza JC, Sherman JD, Shi L, Shumake-Guillemot J, Silbert G, Sofiev M, Springmann M, Stowell J, Tabatabaei M, Taylor J, Triñanes J, Wagner F, Wilkinson P, Winning M, Yglesias-González M, Zhang S, Gong P, Montgomery H, Costello A. The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 2022, 400, 1619–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Middleton N, et al. Desert dust and health: a Central Asian review. Sci Total Environ. 2018, 612, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Nabi, S.S.; Al Karaki, V.; Khalil, A.; El Zahran, Th. ; Climate change and its environmental and health effects from 2015 to 2022: A scoping review. Heliyon 2024, 11, e42315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archad, F.S.; Hod, R.; Ahmad, N.; Ismail, R.; Mohamed, N.; Baharom, M.; Osman, Y.; Mohd Radi, M.F.; Tangang, F. The Impact of Heatwaves on Mortality and Morbidity and the Associated Vulnerability Factors: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazish, A.; Abbas, K.; Sattar, E. Health impact of urban green spaces: a systematic review of heat-related morbidity and mortality. BMJ Open 2024, 14, 081632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocque, R.J.; Beaudoin, C.; Ndjaboue, R.; Cameron, L.; Poirier-Bergeron, L.; Poulin-Rheault, R.A.; Fallon, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Witteman, H.O. Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, 046333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman K, Turner LR, Tong S. Floods and human health: a systematic review. Environ Int. 2012, 47, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanke C, Murray V, Amlôt R, Nurse J, Williams R. The effects of flooding on mental health: Outcomes and recommendations from a review of the literature. PLoS Curr. 2012, 4, e4f9f1fa9c3cae. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez A, Black J, Jones M, Wilson L, Salvador-Carulla L, Astell-Burt T, Black D. Flooding and mental health: a systematic mapping review. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0119929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A., 3rd; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Al-Kindi, S.G.; Brook, R.D. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2054–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Sørensen, M.; Gori, T.; Schmidt, F.P.; Rao, X.; Brook, J.; Rajagopalan, S.; Brook, R.D. Environmental stressors and cardiometabolic disease: Part I–Epidemiologic evidence supporting a role for oxidative stress. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C.A.; Bhatnagar, A.; McCracken, J.P.; Abplanalp, W.; Conklin, D.J.; O’Toole, T.E. Exposure to fine particulate air pollution is associated with endothelial injury and systemic inflammation. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrousos, G.P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thayer, J.F.; Åhs, F.; Fredrikson, M.; Sollers, J.J., 3rd; Wager, T.D. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart–brain neurophysiology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 33, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, R.A.; Dimmeler, S. MicroRNAs in myocardial infarction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari-Jahantigh, M.; Wei, Y.; Schober, A. MicroRNA-specific regulatory mechanisms in atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 3020–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, A.J.; Becher, H.; Ziegler, C.M.; Lichy, C.; Buggle, F.; Kaiser, C.; Lutz, R.; Bültmann, S.; Winter, B. Association of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 with risk of ischemic stroke. Stroke 2004, 35, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogne T, Wang R, Wang P, Deziel NC, Metayer C, Wiemels JL, Chen K, Warren JL, Ma X. High ambient temperature in pregnancy and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: an observational study. Lancet Planet Health 2024, 8, e506–e514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- WHO. Operational framework for building climate-resilient health systems. World Health Organization, 2015.

- Haines A, Ebi K. The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors & Year of Publication |

Study Population |

Study Location |

Study Period |

Climate Parameter | Health Outcome | JBI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou et al., 2022 | Stroke deaths | 22 towns of East Asian countries | 1972-2015 | Heat exposure | Heat exposure was significantly associated with high stroke mortality. In total, 287,579 stroke deaths were recorded during the warm season. | Moderate |

| Achebak et al., 2018 | Record of deaths | Several cities in Spain | 1980-2015 | Heat | The findings showed that the risk of mortality due to respiratory diseases was high, particularly among women. In Spain, heat vulnerability decreased as a result of enhanced healthcare services, air conditioning use, and effective public health measures. | High |

| Huber et al., 2024 | Daily all-cause mortality linked to daily mean temperatures | Germany | 2000-2023 | Heat | During the summer of 2022, around 9,100 deaths in Germany were linked to extreme heat exposure. | Moderate |

| Chesini et al., 2022 | 22 million residents | Argentina | 2013-2014 | Heat waves | This study demonstrated that high mortality rates were mainly associated with respiratory, cardiovascular, diabetes, and renal illnesses. People above 60 years old were particularly affected. | High |

| Baker et al., 2024 | Population of about 10 million (8 million adults) | Los Angeles County | 1/1/2014 to 12/31/2019 | Heat waves | Moderate heat risk was associated with an increase in mortality, confirming the significant impact of heat events on death rates. | Moderate |

| Oray et al., 2018 | ED visits and mortality rates | Izmir, Turkey | 17th and 25th June 2016 | Heat waves | During periods of extreme heat, an increase in both emergency department visits and in-hospital death rates is observed. Therefore, the implementation of effective adaptation strategies is required. | Moderate |

| Yezli et al., 2024 | Rates of HS & HE (Two million people from over 180 countries) | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | Mecca meteorological data (1980–2021) and the incidence of HS and HE during Hajj (1980–2019) | Heat waves | High ambient temperatures show a strong correlation with higher incidence rates of heat stroke (HS) and heat exhaustion (HE). | Moderate |

| Alho et al., 2024 | Hospital admissions | Portugal | 2000-2018 | Heat waves | Heatwaves have been significantly linked to elevated hospitalization rates for all major health conditions and across all age demographics. | Moderate |

| Tabassum et al., 2019 | Data on hospital | Pakistan | 20-27 June 2015 | Heat (heat stroke) | During the heatwave period, 315 patients visited the Emergency Room (ER). Some of them were expired, but the majority survived. Among them, 55% were men, while 60% of patients were fully mobile. | Low |

| Green et al., 2016 | Civil deaths in England and Wales | England & Wales | 2013 summer | Heatwaves | In 2013, during a heatwave period, 195 deaths were recorded among individuals aged 65 and over. | Moderate |

| Figgs et al., 2019 | Admissions to Douglas County | Douglas County, NE | 2011-2012 | Heatwave | Asthma diagnosis in the emergency department did not show a significant increase in 2012 compared to 2011. However, the risk was higher among individuals under 19 years old and among African American individuals, after adjusting for exposure to heatwaves. | Moderate |

| Figgs et al., 2020 | Admissions to Douglas County | Douglas County, NE | 2011-2012 | Heatwave | During the 2012 risk period, females had almost 4 times more odds of developing chronic bronchitis at emergency department in comparison with females during the equivalent period in 2011. | High |

| Bhatta et al., 2020 | 366 research participants | Nepalgunj Sub-metropolitan | June to December 2019 | Heat | In this study, most participants showed symptoms associated with heat exposure. | Moderate |

| He et al., 2023 | Record of deaths in several Chinese regions | China | 2013-2019 | Ambient heat | The results show the association between elevated summer temperatures and a greater likelihood of accidental mortality. The findings demonstrate that the risk is notably higher among males and younger individuals, suggesting that existing assessments of climate change’s health impacts may underestimate the risks, especially for younger demographics. | High |

| Oheneba-Dornyo et al., 2022 | Malaria cases in several regions of Ghana | Ghana | January 2012 to May 2017 | Heat and rainfall | In the region of Ghana, higher maximum temperatures exhibit a statistically significant negative effect on malaria incidence, while rainfall—lagged by two months—shows a statistically significant positive effect. | Moderate |

| Vaidyanathan et al., 2020 | Record of deaths | United States | 2004-2018 | Heat | Exposure to heat contributed to deaths associated with specific chronic health conditions and various external causes. | High |

| Mohammadia et al., 2019 | Working in palm groves | Jiroft, Southeastern Iran | August to September, 2017 | Heat | The findings of this study showed that date harvesters were exposed to heat stress levels exceeding the WBGT reference limit set by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). In the palm groves of Jiroft, harvesters indicated a low level of physiological strain and a moderate level of perceived strain due to heat exposure. | Moderate |

| Tripp et al., 2015 | Athletes at different high schools in Florida | Florida | August-October 2013 | Heat | The incidence of exertional heat illnesses (EHIs) peaked in August. Training sessions during that month which exceeded the recommended duration of three hours, were linked to an increased risk of heat-related illnesses. Overall, the rate of EHIs among the high school football players observed in the study was lower than the rates reported for collegiate football athletes in the same region. | Moderate |

| Gasparrini et al., 2015 | Analysis of premature deaths | 384 locations (13 countries) |

1985-2012 | Non-optimum ambient temperature | A total of 7.71% of all recorded deaths were associated with non-optimal temperatures. Low temperatures accounted for a significantly higher rate of these deaths compared to heat. The proportion of deaths related to non-optimal temperatures differed across countries. | High |

| Achebak et al., 2023 | All-cause mortality | 8 prov inces in Spain | 1980-2018 | Heat and cold | High vulnerability of mortality related to cold conditions is presented among older individuals. Demographic and socioeconomic factors play a significant role in vulnerability of mortality related to heat- and cold. | High |

| Rogne et al., 2024 | California birth records | California | Jan 1, 1988, to Dec 31, 2015 | High ambient temperature | The highest relation between ambient temperature and the risk of acute lymphoblastic leukemia occurred during the 8th week of gestation, with a 5°C rise in temperature linked to a 1.07% increase in the odds ratio. | High |

| Kienbacher et al., 2022 | 1109 adults’ patients with STEMI | Austria | March 2012 to July 2017 | Heat or cold exposure | On cold days, 85% of patients with STEMI were male, whereas the proportion was lower on hot days (71%) and on days with moderate temperatures (72%). Warm days did not show any notable differences between genders. | High |

| Ling-Shuang et al., 2020 | Record of deaths per day | 70 counties in Hunan, China | 1 January 2013 to 31 December 2017 | Non-optimum Ambient Temperature | Environmental temperature contributed significantly to the burden of years of life lost (YLL), accounting for 10.73% of YLL from non-accidental deaths and 16.44% from cardiovascular-related deaths. | High |

| Miao et al., 2024 | 27712 patients with fatal AMI | Xuzhou, China | January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2020 | Temperature | The risk of fatal acute myocardial infarction (AMI) rises significantly during cold weather, while no such increase is observed in hot days. | High |

| Yoshizawa et al., 2023 | Out-of-hospital natural deaths | Osaka, Japan | 2018 to 2022 | Temperature | The relative risk of out-of-hospital non-COVID-19 deaths increased at both cold and hot temperatures in the period following the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to the period before it. This suggests a high sensitivity to temperature extremes after the pandemic. | Moderate |

| Onozuka et al., 2016 | Daily data on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest OHCAs | 47 prefectures of Japan | 2005-2014 | Temperature | Exposure to extreme temperatures is linked to a higher risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). | High |

| Wen et al., 2023 | Weather data in 181 towns | China | 2015 | Temperature | This study showed that long-term exposure to temperature variability (TV) was linked to the prevalence of major diseases among older adults. | Moderate |

| Kunene et al., 2023 | Record of diarrheal cases per day in hospitals | Rural site in South Africa | 2007-2016 | Temperature | An increase in average daily temperature was associated with a higher rate of hospital admissions for diarrhea disease, affecting individuals of all ages, with a notable impact on those over the age of five. | Moderate |

| Wen et al., 2024 | Outpatient and inpatient admissions | Thailand | January 2013 to August 2019 | Temperature | According to the findings, both low and high temperatures effect on hospital admissions, with the strongest effects observed among females, as well as children and adolescents aged between 0 and 19 years. | High |

| Jamshidnezhad et al., 2021 | 31 provinces of Iran | Iran | 04/03/2020 and 05/05/2020 | Temperature | This study clearly demonstrated that as outdoor temperatures rise, the use of air conditioning to maintain indoor comfort, becomes inevitable. Consequently, this may contribute to an increase in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. | Moderate |

| Meiman et al., 2015 | Record of deaths due to hypothermia | United States | 2003-2013 | Cold | In the United States, extreme cold contributes to an increase of weather-related deaths. Factors that increase the risk of hypothermia-related mortality include older age, mental health disorders, sex, and drug intoxication. | Moderate |

| Lelieveld et al., 2023 | Globally deaths | Global | 2019 | Air pollution (fine | Fine particulate matter and ozone air pollution are estimated to contribute to approximately 8.34 million excess deaths globally per year. | Moderate |

| Zoran et al., 2023 | Record of COVID cases | Tokyo | March 1, 2020- 2022, 1 October | Air quality and climate variability | The elevated daily COVID-19 cases and death rates observed in Tokyo, during the seventh wave may be linked to increased concentrations of air pollutants and viral pathogens. | Low |

| Stafoggia et al., 2023 | Population data (people aged 30 years and over) | Italy | 2016-2019 | Air pollution & high temperature | All-cause mortality is associated with the effects of acute exposure to air temperature, while cause-specific mortality is primarily linked to the long-term impacts of chronic exposure to air pollution. | High |

| Tian et al., 2020 | CVD deaths | Shanghai, China | 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2014 | Ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and extreme weather conditions | Short-term exposure to PM2.5 was linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality, with evidence of lagged effects. However, cold weather may present a potential antagonistic interaction of PM2.5. | High |

| Parmar et al., 2019 | Household women | Nigeria | January 2019 | Air pollution | In Nigeria, the concentration of particulate matter (PM), carbon monoxide (CO), and thermal stress, are unhealthy, with women and young children being the most vulnerable groups. | Moderate |

| Yussuf et al., 2023 | The data obtained was temporal and averaged monthly from the sources | Mombasa, Nakuru, and Nairobi | 1990-2020 | Air pollution | The effect of PM2.5, carbon monoxide, and sulfur dioxide is different on lower respiratory infections among children across all cities. | Moderate |

| Korsiak et al., 2022 | 2 million people | Canada | 1996-2015 | Wildfires | Exposure to wildfire smoke increases the incidence of lung cancer and brain tumors. | High |

| Hutchinson et al., 2018 | Medi-Cal recipients | San Diego | 2007 | Wildfires | During wildfires, some respiratory diseases, such as asthma, increased among vulnerable populations. | Moderate |

| Blando et al., 2022 | Medical records of a clinic | A small town less than 40,000 residents (United States) | 1st fire (from 9 June through 7 October 2008) & 2nd fire (from 4 August through 11 October 2011) | Wildfires | A decline in peak respiratory flow was observed among allergy clinic patients one year following each wildfire incident. | Moderate |

| Karmarkar et al., 2020 | People in evacuation shelters | California | November 2018 | Wildfires | Between November 8 and 30, a total of 292 cases of norovirus illness, including 16 confirmed and 276 probable cases, were identified among a fluctuating population of approximately 1,100 evacuees across eight of nine shelters. | High |

| Kouis et al., 2021 | 211 children | Cyprus and Greece-Crete | February-May 2019 February-May 2020 February-May 2021 | Desert dust | Dust outbreaks with high PM10 levels are linked to increases in overall and specific mortality rates, as well as higher hospital admissions for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). | High |

| Baten et al., 2020 | 17863 ever-married women | Bangladesh | 2011-2014 | Floods | The study reveals that floods can have a detrimental effect on the utilization of MNH. Additionally, repeated floods have a worse effect on MNH utilization than incidental floods. | Moderate |

| Wettstein et al., 2025 | Exposure of extreme flood events | United States | January 1, 2008, to December 31, 2017 | Floods | Increased health care use and costs are linked with flood exposure, indicating the necessity for targeted public health strategies and enhanced disaster preparedness, particularly for older adults. | High |

| Zhu et al., 2024 | Demographic and Health data on birth mortality | Africa | 1990-2020 | Floods | Exposure to floods is linked to high risks of infant mortality across several time periods, with these risks remaining high for up to four years after the flood event. | High |

| Stamos et al., 2024 | International disaster and fatality datasets | Mediterranean regions | 1900-2023 and 1980-2023 | Floods | Flood mortality is related to geographic variations and generally inconclusive temporal trends. | Moderate |

| Osei et al., 2022 | Population | 53 African countries | 2000-2018 | Floods | This study showed that foods lead to destruction of health infrastructure and to the dispersion of illnesses, thereby reducing life expectancy. In 53 African countries, the mortality rate increases due to floods. | Moderate |

| Rerolle et al., 2023 | Almost 600000 mothers interviewed in several regions using surveys | Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and northern India | 1988-2017 | Floods | High-resolution data on flood risk and population distribution reveal an excess of infant deaths in flood-prone regions of Bangladesh over the past 30 years, with notable variations in the burden across different regions. | High |

| Ferdous et al., 2020 | Flood mortality rate in a region of Bangladesh | Bangladesh | 2017 | Floods | During the 2017 flooding in Bangladesh, regions with lower levels of flood protection presented lower mortality rates. | Moderate |

| Graham et al., 2019 | Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey | England | May 2014 to September 2015 | Floods | Floods and storms are closely linked to common mental disorders due to its high frequency and intensity. For this reason, community resilience and disaster preparedness have to be enhanced. | High |

| Bouwer et al., 2018 | Data on flood events, and related number of diseases and mortality | Belgium | before & after 1980 | Floods | Flash floods cause the highest mortality rate, following by storm surges and river floods. | Moderate |

| Liu et al., 2017 | Data of bacillary dysentery illness per month | Guangxi, China | January 2004 to December 2010 | Floods | Flood events can cause an increase in bacillary dysentery diseases. By 2030, an 8.0% increase is expected in Guangxi. | High |

| Vanasse et al., 2016 | Adult populations | Quebec, Canada | 2010-2011 | Floods | Previous studies have shown a connection between natural disasters and cardiovascular disease (CVD), but this study suggests that the number of individuals impacted by the flood is limited. | Moderate |

| Thiele-Eich et al., 2015 | Record of deaths | Bangladesh | 1909-2009 | Floods | Between the period 2003-2007, two intense flood events are recorded in 2004 and 2004. The increased water levels are not related to the high mortality rate, as a good level of adaptation and effective flood management are in place. | Moderate |

| Aik et al., 2020 | Record of diarrhea disease | Singapore | 2005-2018 | Climate variability (Humidity, ambient air temperature) | Diarrheal diseases are highly seasonal and are closely linked to climate variability. | High |

| Gill et al., 2021 | Traumatic injuries and deaths caused by natural disasters | United States | 2014-2019 | Natural Disasters (Floods, wildfires, hurricanes and tropical storms) |

The number of traumatic injuries and fatalities from certain natural disasters in the United States has significantly increased between 2014 and 2019. | Moderate |

| Tawiah et al., 2023 | Children at hospitals | Bono Region, Ghana | 2010-2021 | Rainfall, humidity, and temperature | The findings show that both malaria cases conducted and climate parameters have a significant impact on confirmed malaria cases among children under 5 years. | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).