I. Introduction

This study has an interdisciplinary perspective that touches upon several fields of studies including software requirements, systems theory, ontology, process philosophy, and process techniques (e.g., a workflow). Our purpose is to build a foundation for conceptual modeling as a high-level representation of a targeted domain of reality, focusing on key elements without delving into implementation details. The conceptual model is used to understand, communicate, and design systems in fields such as software engineering, database design, and business process management.

A. Focus and Orientation

Specifically, we focus on process-based modeling. Commonly, a process is viewed as a sequencing of tasks, actions or operations that transform inputs into outputs to achieve a specific outcome. Typically, this definition is represented in the known input–process–output model. Additionally, this paper is oriented toward generality so as to provide an understanding of the targeted portion of reality (e.g., a business) in the context of conceptual modeling. Such a venture should absorb and supplement our current knowledge and technicalities (e.g., in software engineering). Analyzing and exploring the meta-theoretical considerations can be seen not only as a much-needed theoretical clarification of the humanist aspects underlying the practice of both engineers and developers but also as a foundation for further profitable future reflections and speculations [

1].

B. Process and Events

Processes are said to refer to “goings-on,” happening, doing, sensing, being, and becoming [

2]. The term “process” may indicate different meanings presented in the literature. An analysis of literature sources showed no integrated approach in this context [

3]. The earliest description of the process comes from Adam Smith: “One worker drew the wire, another straightened it, the third cut it, the fourth cut the tip, and the fifth, sixth, and seventh cut the head. The head took three separate operations: placing the head on a pin is one operation; polishing a pin is another… . In this way, the production of pins is broken down into about eighteen different operations” [

3].

According to Seibt [

4], despite Aristotle’s sophisticated investigations of change and interactive development, and despite Whitehead’s bold attempt at comprehensive process metaphysics, the traditional research focus in ontology has been on “static” entities such as objects (substances), properties, relations, and facts. Those contemporary ontological schemes that are deemed “revisionary” denote the primacy of “substances” merely to turn to other types of static particulars, such as tropes or states of affairs.

Process philosophy is linked to a metaphysical tradition stemming from Heraclitus, Plato, and Aristotle in antiquity. In the general process theory, A. N. Whitehead observed physical processes. Henri Bergson saw biological processes as fundamental and conceived of the world in essentially organismic terms. William James based his ideas of process on a psychological model [

5].

For a more modern view of the notion of process, consider the writing of Rescher [

5], which has influenced the work in this paper, especially in relating process to events. According to Rescher [

5], “A process is a coordinated group of

changes in the complexion of reality, an organized family of occurrences that are systematically linked to one another either causally or functionally” (italics added). Rescher [

5] continued that “It is emphatically not necessarily a change in or of an individual thing, but can simply relate to some aspect of the general ‘

condition of things’” (italics added). Furthermore, according to Rescher [

5], “A process consists in an integrated series of connected developments unfolding in conjoint coordination in line with a definite program.

Processes are correlated with occurrences or events [underline added for emphasis

]: Processes always involve various

events, and

events exist only in and through processes” (italics added). Just as the static complexity of a set of (filmstrip-like) photographs of a flying arrow does not adequately capture its dynamic motion, the conjunctive complexity of a process’ description does not adequately capture its transtemporal dynamics [

5].

Alfred North Whitehead, in his early writing, considered that events are the metaphysical building blocks used to account for the temporal and spatial extensiveness of reality [

6]. In the words of Whitehead,

The ultimate facts of nature, in terms of which all physical and biological explanation must be expressed, are events connected by their spatio-temporal relations, and that these relations are in the main reducible to the property of events that they can contain (or extend over) other events which are parts of them. In philosophy, events are more ultimate than space and time, constituting them as interconnected […]

The ultimate facts of nature, in terms of which all physical and biological explanation must be expressed, are events connected by their spatiotemporal relations, and that these relations are in the main reducible to the property of events that they can contain (or extend over) other events which are parts of them. [

6]

A distinction of ontological category is often drawn between events and processes where process is understood as “the stuff of time” [

7]. Heaton [

7] considered individual processes as dynamic, growing entities and defended the position that recognizes events and processes as belonging to distinct metaphysical categories. Davidson did not recognize an event–process distinction [

8].

C. Aim

In this paper, we develop a model framework for this idea of

processes in terms of events, utilizing the thinging machine (TM) model [

9]. In the TM model, a process is an event or constellation of events (e.g., chronology of events). The general thesis of this paper is unifying the notions of events, changes and processes. In TM, generic events (create, process, release, transfer, and receive) are units of change. Changes (generic or complex) are processes

per se in a larger sense.

D. Sections

For the sake of a self-contained paper, the next section includes a brief review of the TM model’s theoretical foundation. Section 3 provides illustrative examples of the TM modeling. Section 4 includes reflections on the notions of event, change, and process that clarify the ontological foundation of TM modeling. Section 5 includes a discussion about the notion of change limit. Section 6 presents examples that discuss business processes.

II. TM Modeling

In contrast to world-comprising substantial things and relationships, as philosophers have overwhelmingly supposed, process-oriented approaches view that existence is best understood in terms of processes rather than things and insist on seeing process as a constituting and essential aspect of everything that exists [

5]. Existence is “a matter of ‘putting in an appearance,’ of something projecting itself into reality by way of taking up a position on the world’s stage” [

5]. The TM model is a venture in this direction.

The TM model provides an ontological representation of reality based on

thimacs (

thing/

machine). A thimac has two modes: a thing and a machine. It is similar to Rescher’s [

5] Janus-faced processes: “They look in two directions at once, inwards and outwards. They form part of wider (outer) structures but themselves have an inner structure of some characteristic sort.” In ordinary language, thimacs may be thought of as phenomena. If so, then the phenomenon in TM has a static form (called region) and a dynamic form (called event or existents). The latter involves a region plus time.

A. The TM World

The world is divided into thimacs, and various thimacs overlap or combine to form the texture of the whole as a grand thimac. The outside of this thimac (world) may contain non-thimacs and may be scattered constellations of generic actions that lack thimac structure. The thimac structure is built upon five genetic actions: create, process, release, transfer, and receive. In the TM model, every action must belong to a thimac. The TM world is a tightly interwoven fabric of thimacs and their actions.

B. The Generic Actions

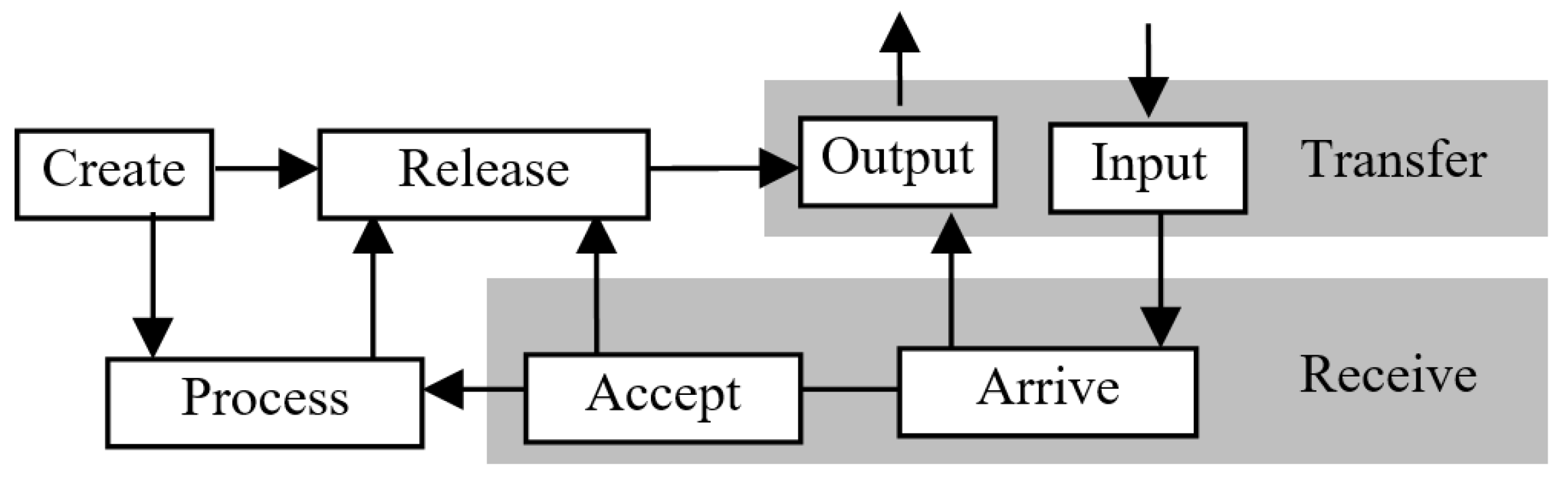

Thimacs are defined in terms of bundles of generic (i.e., no sub-action) actions structured as shown in

Figure 1.

Things, numbers, sets, concepts, rainstorms, heat waves, songs, headaches, and propositions are thimacs. The thimac is an all-inclusive notion of a whole, integrated representation of all elements (e.g., things, events, universals, particulars). It encompasses static and dynamic modes.

C. The Thimac

A generic thimac has an internal cloudlike structure of actions: create, process, release, transfer, and receive. The thimac’s constituents are formed from the makeup of these actions. Note that we use the term process in two senses: as one of the TM generic actions and as the meaning of process used in the general literature. The intended meaning is clear from the context.

A thimac is a complex bundle of the five coordinated actions. The actions combine to constitute the sum total of the thimac that is preserved even when passing from one action to another and persisting in the same action (note that the thimac can be an object to actions of other thimacs or a subject that acts on other thimacs).

Despite the differences among actions, the totality of the thimac focuses on what they have in common: actionality (changability). An action is a unit of actionality. The TM modeling is built upon the primacy of actionality structured as a thimac.

D. The Thimac as a Thing and as Machine

In its full manifestation, a thimac is a machine (i.e., what acts on) that creates, processes, releases, transfers, and receives some other thimacs; simultaneously, a thimac is a thing (i.e., what is acted on) that is being created, processed, released, transferred, and received by some other thimacs. Thus, a thimac as a thing is a patient that undergoes changes (created, processed, released, transferred, and received) and as a machine that serves as an agent that brings about changes to other thimacs or itself (e.g., a doctor treats herself).

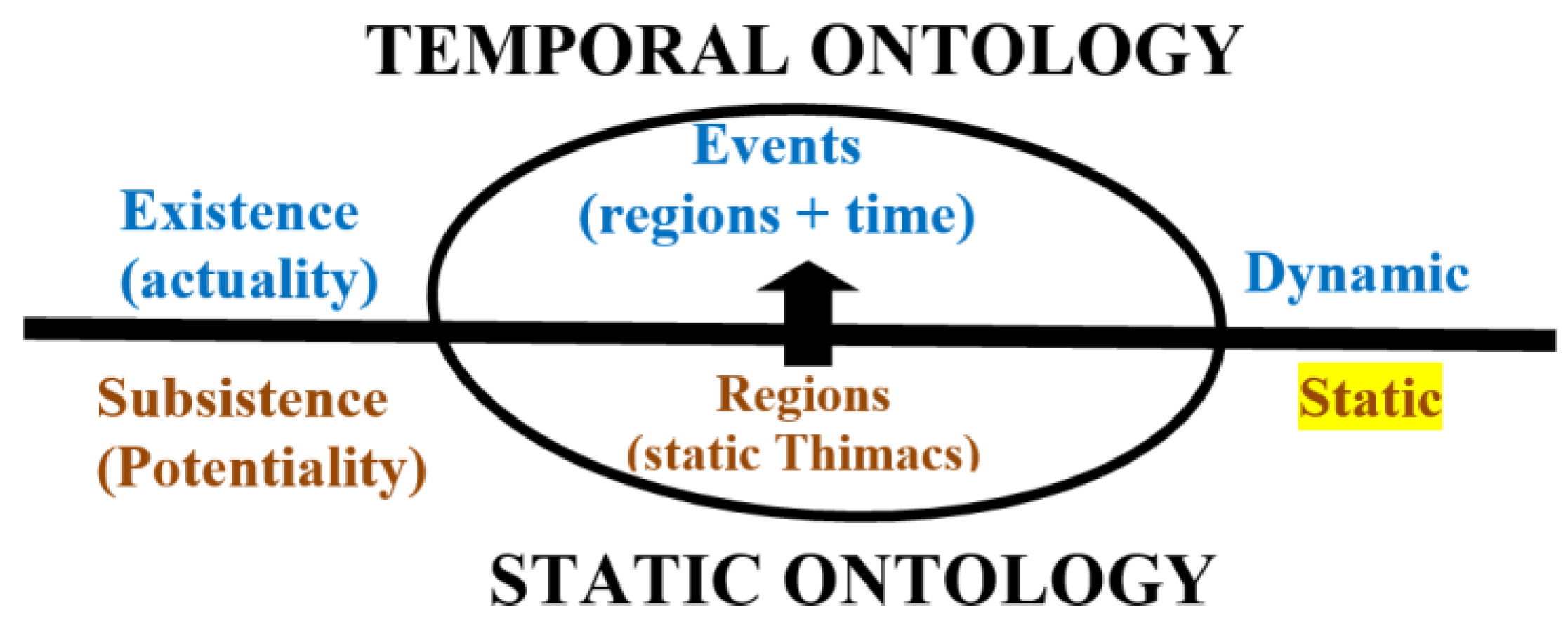

E. Thimac as a Region and as an Event

The thimac-oriented model views reality in terms of static thimacs (regions) and time-based containers that form events. Thimacs can be conceptualized in two modes: actual (dynamic) and potential (static) thimacs. A TM static diagram or sub-diagram is called a

region at the static-modeling level.

Figure 2 shows an ontological picture that outlines the two levels of the TM scheme.

F. The Action: Create

The thimac is a universal, totalizing construct that must include

create within its structure (

Figure 1). Samples of thimacs include the following:

Create,

Create→release→transfer,

Create→process,

Create and transfer→receive→process→release→transfer

Examples of an illegal construct include the following:

Create→transfer

Process→create (i.e., processing of an old thing cannot make it a new thing). Process can be related to Create as Process ---> create, where the dashed arrow indicates triggering, as will be explained later. Note again that the term process is used in this paper in two senses: (1) as one of the five TM actions and as (2) the general notion of process.

G. Actions

At the most basic explanatory level, we conceive the thimac as constituted by two kinds of capacity, which we label thing and machine. A thing constitutes the thimac’s capacity to be affected, whether by itself (i.e., one “part” or capacity of the thimac affecting another) or some other thimac (machine). In contrast, the power of machinery is an ability to initiate its actions from itself on other thimacs (things).

The thimac is a thing with a “structure” formed by the flow of other thimacs through it. It is a machine with five actions that operate on things. The flow among thimacs provides a world’s looseness of structure (e.g., a bird now perched on yonder telegraph pole is, a moment later, on the branch of a tree) [

10].

A thimac’s actions, shown in

Figure 1, are described as follows:

-

1)

Arrive: A thing arrives at a thimac.

-

2)

Accept

: A thing enters a thimac. For simplification, the arriving things are assumed to be

accepted (see

Figure 1); therefore,

arrive and

accept actions are combined into the

receive action.

-

3)

Release

: A thing is ready for transfer outside the thimac.

-

4)

Process

: A thing is changed, handled, and examined, but no new thimac is generated.

-

5)

Transfer

: A thing crosses a thimac’s boundary as an input or output.

-

6)

Create

: Creation here refers to producing a thing that is new to the world (of the model); therefore, a new thimac is registered as an ontological unit. It indicates the birth or coming-into-thimac (i.e., must make it out of other thimacs). At the static level, create is a logical possibility of realization at the dynamic level.

Additionally, the TM diagrammatic model includes storage (represented as a cylinder in the TM diagram) and triggering (denoted by a dashed arrow). Triggering transforms from one series of actions to another (e.g., electricity process triggers create heat).

III. Example

Consider the following example: You have just reached the airport. You are due to fly to London. You have collected your boarding pass. You have two bags that you would like checked in. The person at the counter asks for your boarding pass in order to process the bags. This done, you proceed to the immigration counter, passport and boarding pass in hand. Your next stop is the security counter. And you find yourself in the queue to board the aircraft. Again, you undergo quick, careful rounds of verification by the aircraft crew before you find yourself ensconced in your seat [

11].

A. Static TM Model

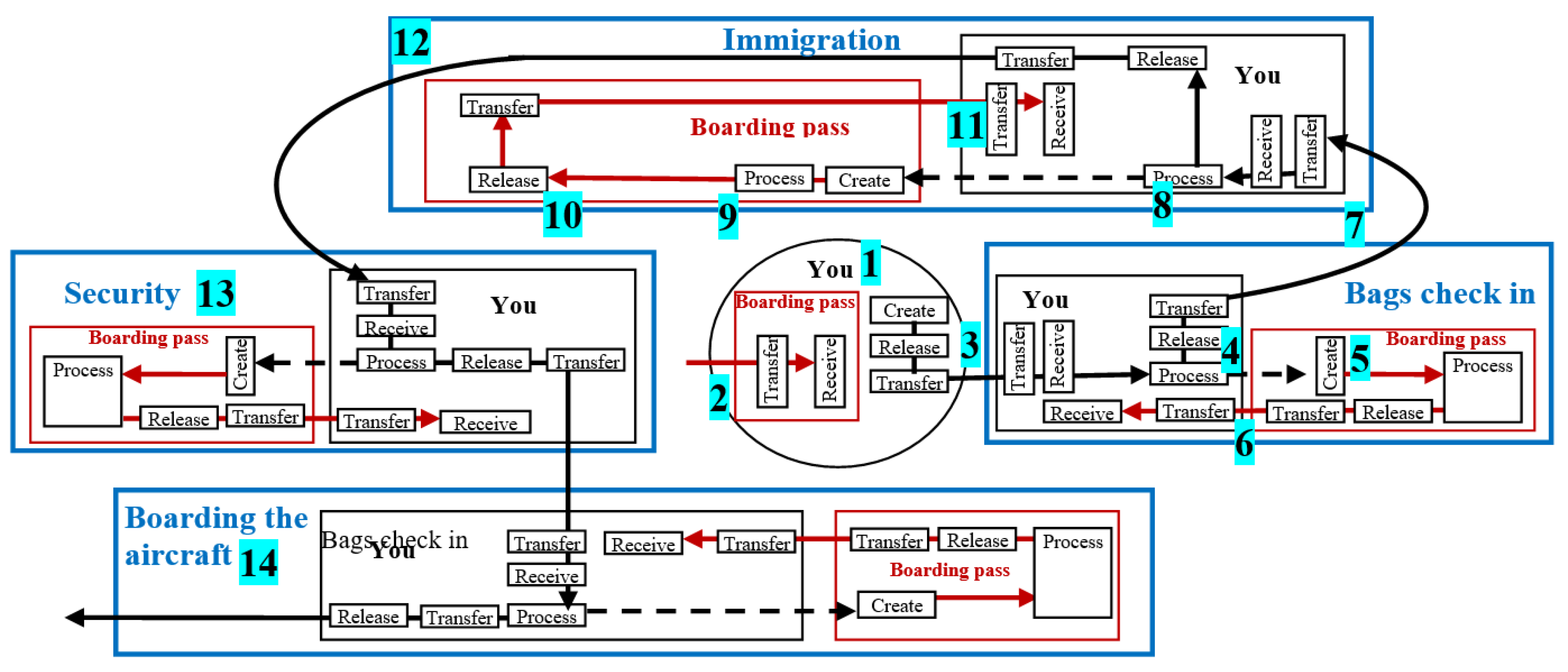

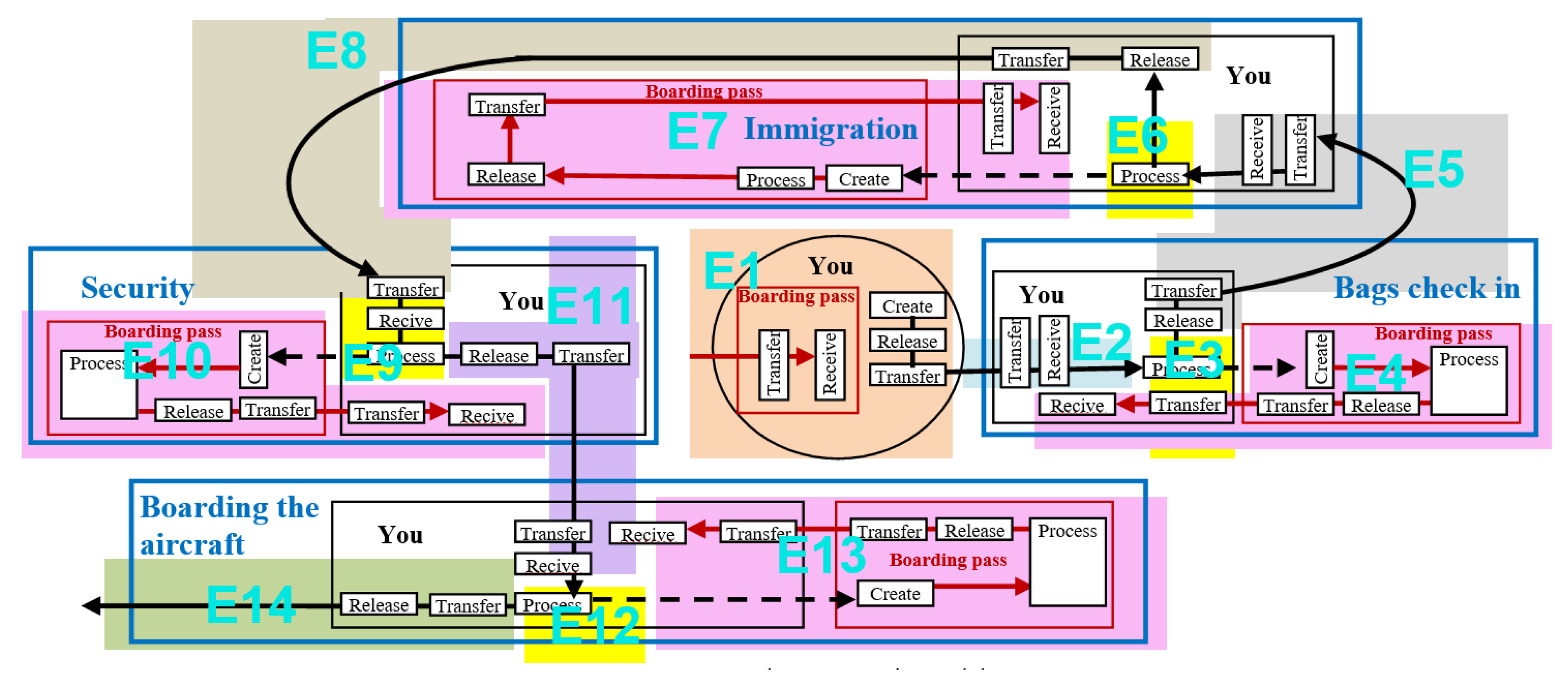

Figure 3 shows the corresponding static TM model described as follows:

The circle (instead of a rectangular for further illustrative purpose) in the middle represents You (number 1 in the figure) receiving the Boarding pass (2).

Accordingly, You (with your Boarding pass) move (3) to the thimac called Bags check in.

In the Bags check in thimac, You are processed (4) by providing your Boarding pass (5). Note, Creating your Boarding pass means the appearance of the Boarding pass in this thimac for the first time as a separate entity.

The Boarding pass is returned (6) to You, and You leave the Bags check in thimac to the Immigration thimac (7).

In the Immigration thimac, You are processed (8) by surrendering your Boarding pass (9) to be processed (10) and given back to You (11). Accordingly, You move to Security (12).

In Security (13), You are processed as before in order to move to the thimac of Boarding the aircraft (14).

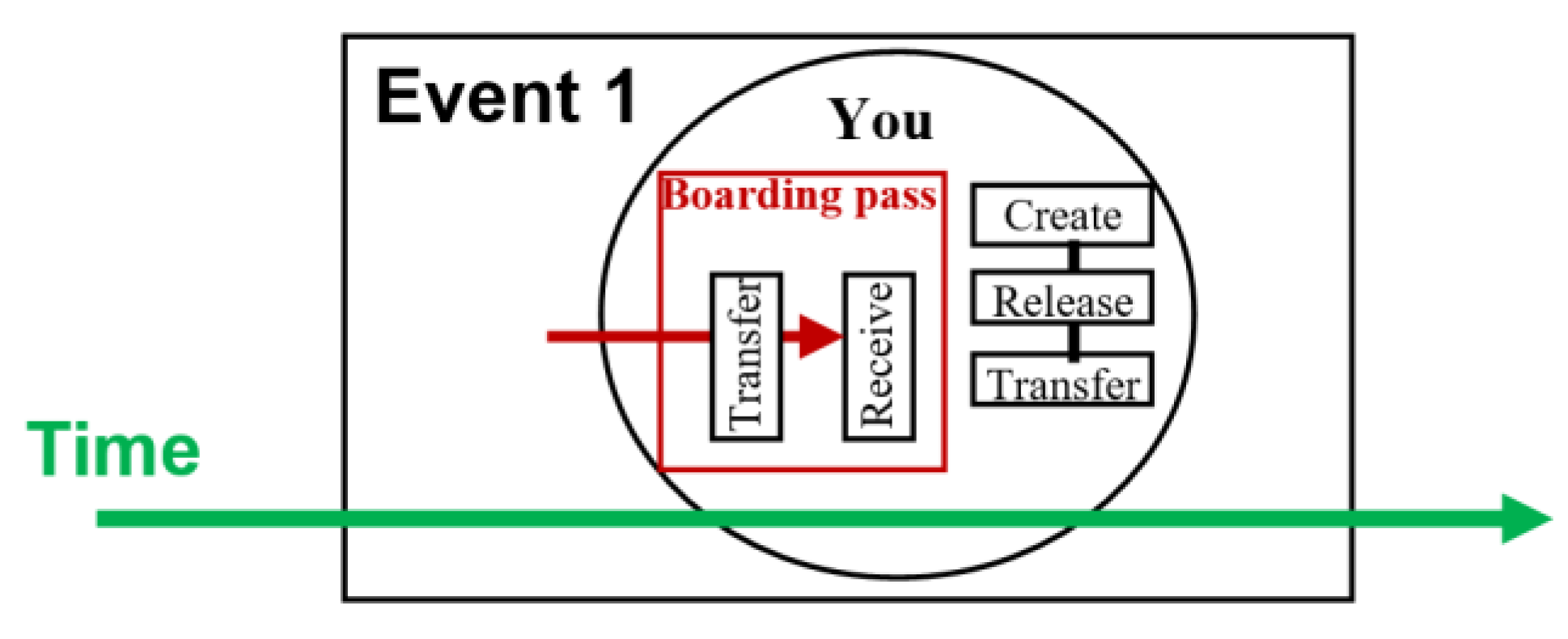

B. Dynamic Model

In the dynamic model, an event is defined in terms of subgraphs (called regions) in the static model plus time. A sample event is given in

Figure 4. For simplicity’s sake, events will be represented by their regions. Accordingly, we can specify the events as follows (see

Figure 5):

E1: You receive the Boarding pass.

E2: You move to the Bags check in.

E3: You are processed in Bags check in.

E4: You present your Boarding pass to be processed and returned to you.

E5: You move to Immigration.

E6: You are processed in Immigration.

E7: In the Immigration, You present your Boarding pass to be processed and returned to you.

E8: You move to Security.

E9: You are processed in Security.

E10: In Security, You present your Boarding pass to be processed and returned to you.

E11: You move to Boarding the aircraft.

E12: You are processed in Boarding the aircraft.

E13: In the Boarding the aircraft, You present your Boarding pass to be processed and returned to you.

E13: You move to board the aircraft.

Figure 6 shows the corresponding chronology of events.

IV. Processes as Events

In the Introduction, we declared adopting the main thesis in this paper that

processes are

events. Furthermore, Rescher [

5] described a

process as a coordinated group of

changes. Hence, it is essential to state the notion of change in TM to provide our thesis that

a process is a TM event. The rest of this paper is an attempt to clarify and justify this claim.

A. Anti-Thesis: Aristotle’s Change

Aristotle defines change as “the actuality of that which is in potentiality, as such (or as potential)” [

12]. According to Gill [

12], “If we aim to specify the change that yields a house, we are not interested in the actuality that the patient is in its own right (say bricks and stones [i.e., house itself]). Nor are we interested in the actuality of the patient's potentially to be a house. Rather, we are interested in the actuality of the patient, as

potentially a house and not actually a house.”

In contrast, in the context of TM, we understand from this that Aristotle’s change, in the example, is that the change is the

becoming of the house and not the

existence of the house. From the TM point of view, the existence of a thing (thimac) is an event (create) and, hence, a change. A generic TM change is defined as a generic event (i.e., creation, processing, releasing, transferring, or receiving is change). We are, here, using the TM definition of an event; in this usage, we follow A. N. Whitehead’s (1861–1947) process philosophy in which objects (e.g., a house) and events are things of the same kind [

13]. Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000) argued that “physical objects” are not to be distinguished from events or processes [

14].

According to Rescher [

5], “Things simply are what they do.” In TM, thimacs (things) are what they create, process,

transfer, and receive AND what are being created, processed, released, transferred, and received. Furthermore, in TM, a generic event (create, process, release, transfer, and receive) is a unit of change. Changes (generic or complex) are processes per se in a larger sense.

For example, Aristotle claimed, as reported by Gill [

12], that “Nutrition is not a change, because the ‘motion’ does not lead the organism into a

state other than the one it was previously in. Nutrition and the organism’s other natural functions, such as perception, are activities which express the organism's nature. By means of activity, the organism preserves and enhances what it already is.” By contrast, in TM, a generic change is a generic event, which is a temporal change (i.e., a change in a thimac implies the passage of time). Because the TM

region of nutrition involves many TM events that trigger the

creation of nutrition, events reflect, from the TM point of view, many changes in achieving nutrition.

B. States Are Also TM Events

Philosophical positions differ greatly in defining what an event is. For example, some researchers have denied the existence of events: “the ‘being’ of events is to take place, happen, occur but not to ‘exist.’ A volcano exists, but an eruption of a volcano cannot exist. The death of Caesar never existed, it took place. Caesar existed and the event of his death was the termination of his existence” [

14]. In TM, the eruption happens in a specific time; hence, the volcano and eruption exist, so they are events. Caesar’s death is an event in time that results in transforming Caesar from existence to subsistence. In TM, an event can be anything: from somebody’s life to the history of the universe [

15].

Additionally, in TM, states are events. An event–state distinction is usually specified by saying that events

happen, whereas states do not; that is, states

obtain [

8]. According to Steward [

8], happening, but not obtaining, necessarily involves

change. Furthermore, it would be a mistake to suppose that states are merely long events; that is, simple duration is the key to understanding the temporal differences between the two categories [

8]. There can be long events (e.g., one hundred years) and short-lived states (e.g., a liquid’s existence at boiling point on an occasion where it reaches a boiling point only for a few seconds and then cools rapidly again). It is not duration but something else, which marks the crucial difference between the two categories [

8].

In TM, complex events are composited, at the basic level, of generic events. A decomposing of an event refers to TM sub-events of subregions of the region of event. Events involve changes because generic events are changes. In TM, states are events. Consider the example given in Steward [

8], wherein the temperature and “pressure states in gases bear an important relation to movements (changes in position) of the molecules of the gases; and states of equilibrium in certain chemical systems might involve the constant passage of molecules between their liquid and gaseous states.” Such states necessarily involve change. In TM, generic events are units of change; hence, events are composed of generic changes.

Change is typically viewed in terms of events and processes where change is involved. According to Mumford [

16], an event may involve just a single change (i.e., a TM genetic event), whereas a process suggests a complex series of more than one change in a particular order (i.e., a complex TM event, e.g., a chronology of events). A change could be a gain or loss of a property (an Arizonian term corresponding to a TM sub-thimac), the coming into or going out of existence (TM create) of something, or a change within one property [

16].

V. Applications of TM Change

In the previous section, we unified the notions of process (in the general meaning), event, and change. In this section, we show a limit on change: repeated change (e.g., the operation of halving a distance) ceases when reaching a single thimac.

Events are thimacs because the TM world is made up of thimacs. Consequently, moving from the geometric point X to point Y is moving (i.e., transfer, release, transfer, and receive) from thimac X to thimac Y, in addition to passing through the thimacs between them.

A. Zeno’s Paradoxes: TM View

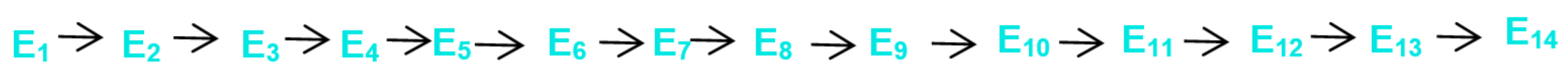

In the famous Zeno’s paradox, each of the half distances between X and Y is a thimac with its transfer, receive, release, and transfer. In TM modeling, this “half-ing” ceases to be applied at a thimac that neighbors point Y. This thimac just before Y is a singleton thimac that has no sub-thimac; in other words, it is a point that contains no other point. In TM, a point cannot be infinitely divisible because the limit of repeated division of a point reaches a thimac. Accordingly, in the last thimac that neighbors point Y, actions release and transfer to Y. Arriving at Y is guaranteed no matter how many thimacs exist between X and Y.

The TM modeling can be applied to the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise. Achilles will never reach the tortoise, as every time Achilles reaches the point where the tortoise was, the tortoise has moved farther ahead. The paradox has remained unexplained until now [

17]. According to Huggett [

18], this paradox brings out most vividly the problem of completing a series of actions that have no final member.

In TM, Achilles catches the tortoise at the point when Achilles transferred-received from the last thimac to the tortoise position, whereas the tortoise released-transferred from its thimac. These events coincide just as the coordination of two persons: one is in the process of leaving a chair while the other is in the process of sitting on it without a collision:

Achilles: transfer-receive

The tortoise: release-transfer

As shown in

Figure 7, the result identifies the point when Achilles catches the tortoise. It depends on the generic actions receive, release, and transfer as a fundamental concept of movement.

This raises the issues of basic quantities of time and the length of these generic events. The conceptual matter, here, reminds us of the theoretical physics Planck time and Planck length.

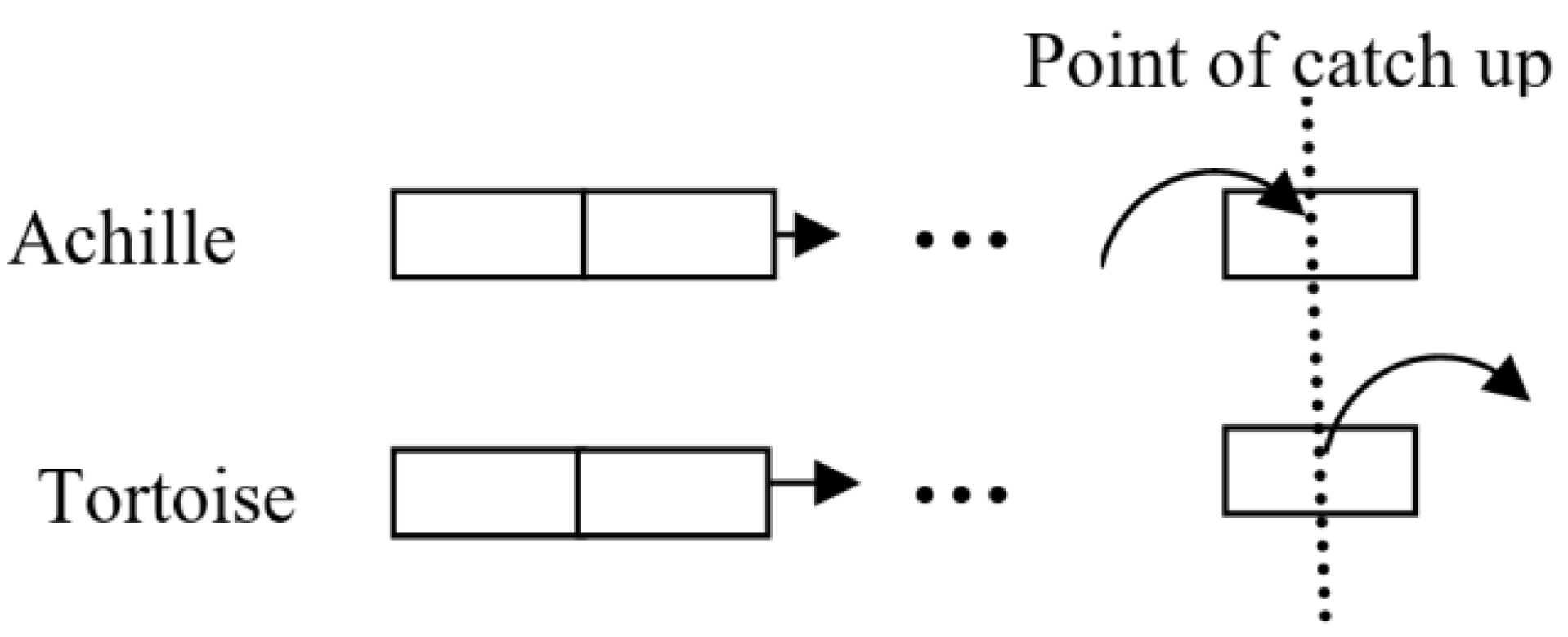

B. Relativistic Time: TM View

Let us reflect on the notion of TM change in the context of relativistic time. Einstein replaced absolute time with new definitions that depend on the state of motion of an observer. Consider two observers and a train [

19]. One observer stands alongside a straight track; the other rides a train moving at a constant speed along the track. The fixed observer measures distance from a mark inscribed on the track and measures time with his watch; the train passenger measures distance from a mark inscribed on his railroad car and measures time with his own watch.

Suppose the train moves 40 km per hour. One hour after it sets out, a tree 60 km from the train’s starting point is struck by lightning. Here comes the issue of

simultaneity. The two people do not actually observe the lightning strike at the same time. Even at the speed of light, the image of the strike takes time to reach each observer, and, because each is at a different distance from the event, the travel times differ [

19].

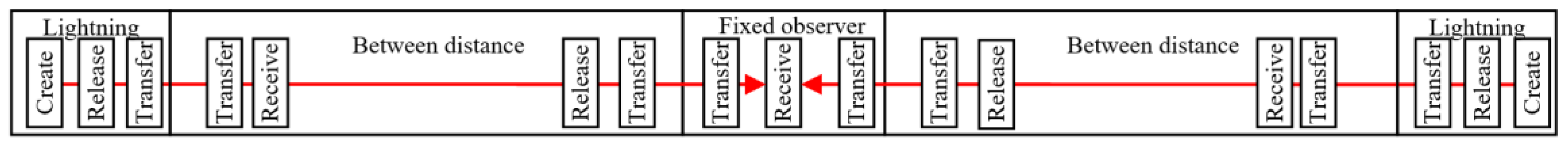

Suppose lightning strikes two trees, one 60 km ahead of the fixed observer and the other 60 km behind, exactly as the moving observer passes the fixed observer (see

Figure 8). Each image travels the same distance to the fixed observer, and so he certainly sees the events simultaneously. The motion of the moving observer brings him closer to one event than the other, however, and he thus sees the events at different times [

19].

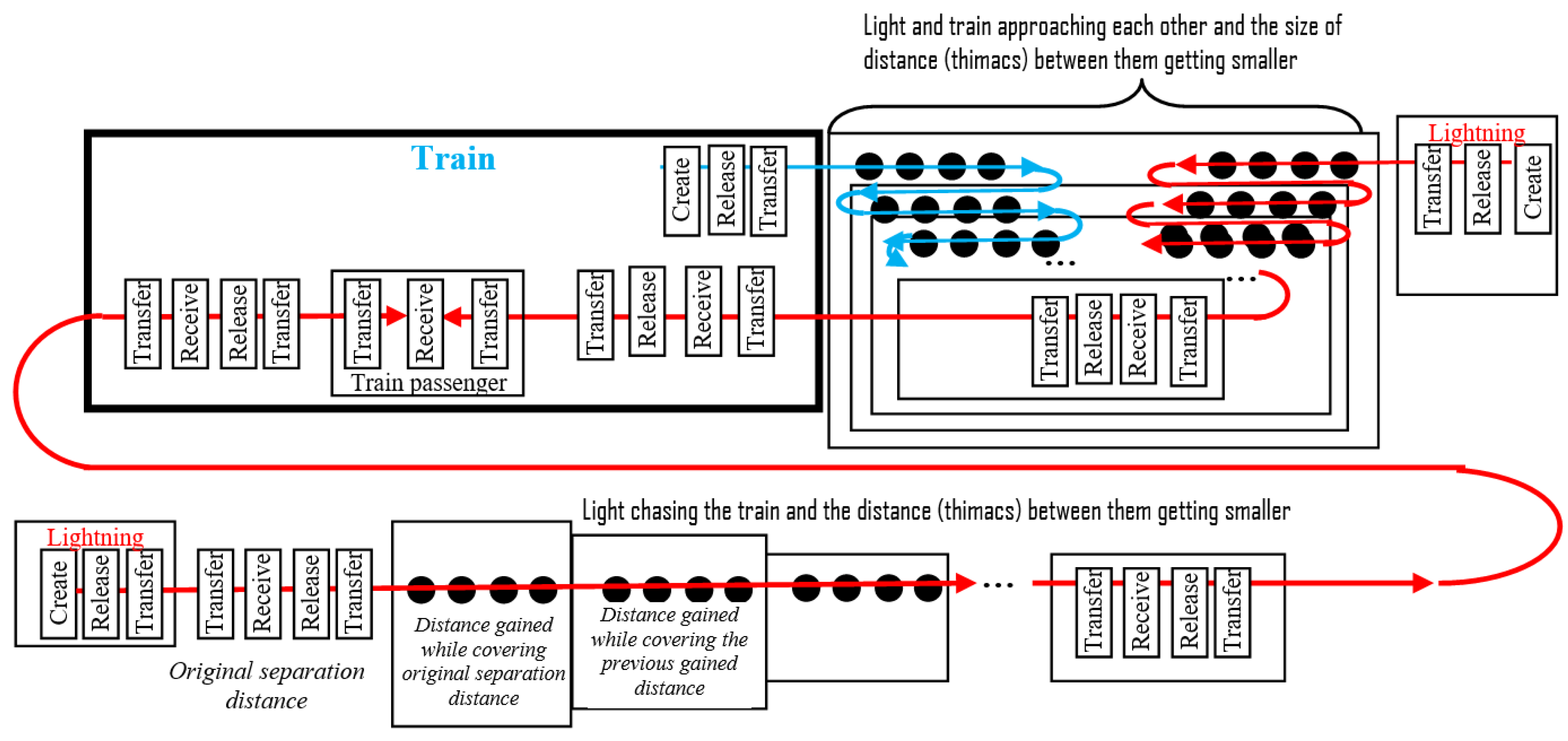

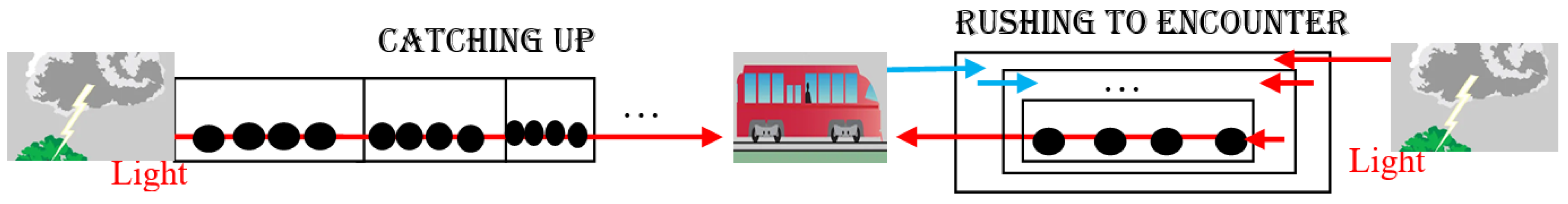

In TM, as seen in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the two progressions of events of the fixed observer and train passenger are

different. Here, events are represented by their regions. In

Figure 9, for the fix observer, the two lightening events are created; hence, each resulting light flows from its place of birth through the distance between this place and the fixed observer to reach him. These two light flows of the fixed observer are the same but opposite in direction. They comprise a process (i.e., complex event) and its opposite (flow) process, sharing the same time slot (called

exicon in [

20]). This is simultaneity. The two processes are the same and opposite in direction.

On the other hand, in

Figure 10, there is no reason to expect this simultaneity for the train passenger.

Figure 10 shows the progressions of events of the two lightening events to the train passenger. In this case, the two flows of events of the train passenger comprise two

different processes of light: the process of catching up to the train and the process of rushing to meet the approaching train. The time slots (exicons) of the two processes partially overlap but do not necessarily occupy the same exicon.

Note the successive decreasing distance between the approaching train and light. Each distance (thimac) is

inside its previous one. On the other hand, when the light pursues the train, each distance between them

follows but is shorter than the previous one.

Figure 11 illustrates this difference in distances.

The issue here is that the discrepancy in the timing of the two lights may be caused by the difference in the two chronologies of events for the train passenger.

Accordingly, simultaneity involves not only the original event but also how the events reaches the observer. This may be what Bergson [

21] meant when he stated that “simultaneity thus understood is easily established between moments in two flows only if the flows pass by ‘at the same place.’” Place, here, means thimacs. Originally, Einstein defined time simply as a judgment of the simultaneity of events [

22].

As we mentioned earlier, generic events are generic changes. Thus, the phenomenon of light in the two chronologies underwent different series of changes to reach the train passenger, creating a discrepancy in arrival. Referring again to Bergson’s ideas, time is the continuation of change.

VI. Business Process

Process, qualified as a business process, was defined in various ways at the end of the 20th century (see [

3]):

- -

A logical organization of people, materials, energy, equipment, and procedures in an organization’s activities, designed to achieve a specific end result.

- -

An organized, measurable set of activities aimed at producing a specific output.

- -

A series of actions or operations conducing to an end.

- -

A sequence of repeatable activities executed within an organization.

- -

Activities that represent the steps required to achieve an objective.

- -

A dynamic ordering of work activities across time and place, with a beginning, an end, and clearly identified inputs and outputs.

Clearly, such a description is based on static logical conceptualization. Davenport and Short [

23] provided examples of processes:

- -

Developing a new product

- -

Ordering goods from a supplier

- -

Creating a marketing plan

- -

Processing and paying an insurance claim

- -

Writing a proposal for a government contract

Bandor [

24] distinguished between process and procedure: “A process defines ‘what’ needs to be done and which roles are involved. A procedure defines ‘how’ to do the task and usually only applies to a single role.” Bandor [

24] mentioned another dictionary definition: A continuous action, operation, or series of changes taking place in a definite manner (i.e., the process of decay).

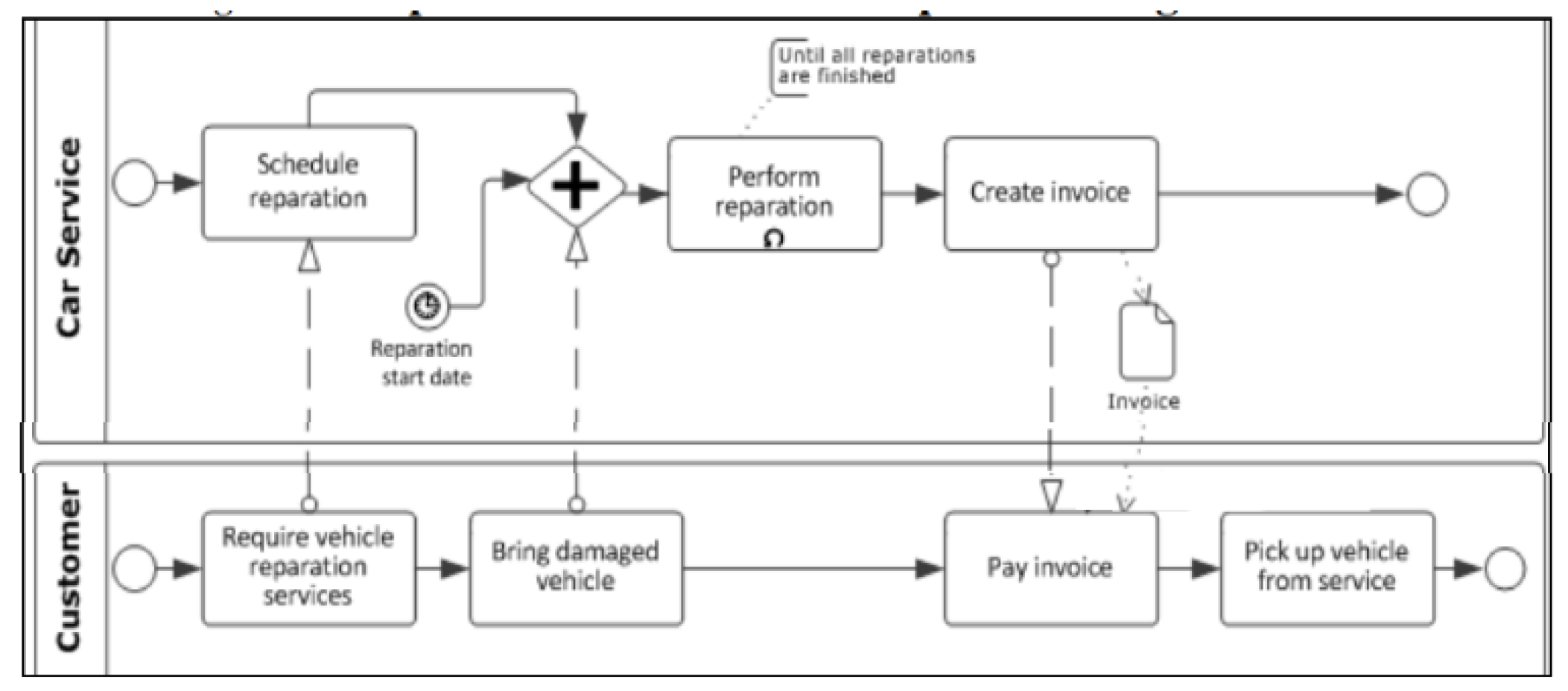

A. Process in BPMN: Example I

Modeling is one of the essential steps for building information systems of the real-world businesses. Process-oriented modeling can be applied to business when adopting the view that businesses are not fixed structures but dynamic systems of interconnected processes, constantly evolving through interactions with employees, customers, markets, and environments [

25]. According to Venera [

25], the first step in improving business is to use an adequate business process modeling language to represent business processes. The two most widely used graphical notations for business processes are business process modeling and notation (BPMN) and UML activity diagram (UML AD).

According to Catalano, Magnani, and Montesi [

26], BPMN enables the representation of three important aspects of business processes, making it a unique modeling tool. First, we can represent choreography of processes. Second, we can represent the orchestration of a process. Third, BPMN allows for the representation of the same information at various levels of detail.

Venera [

25] analyzed BPMN from three perspectives: how easily the users can understand them, how well the graphical elements represent the real business processes of an organization, and how easily these BPMN be mapped to business process execution languages. A case study was used to analyze the graphical symbols used by BPMN for representing the business processes.

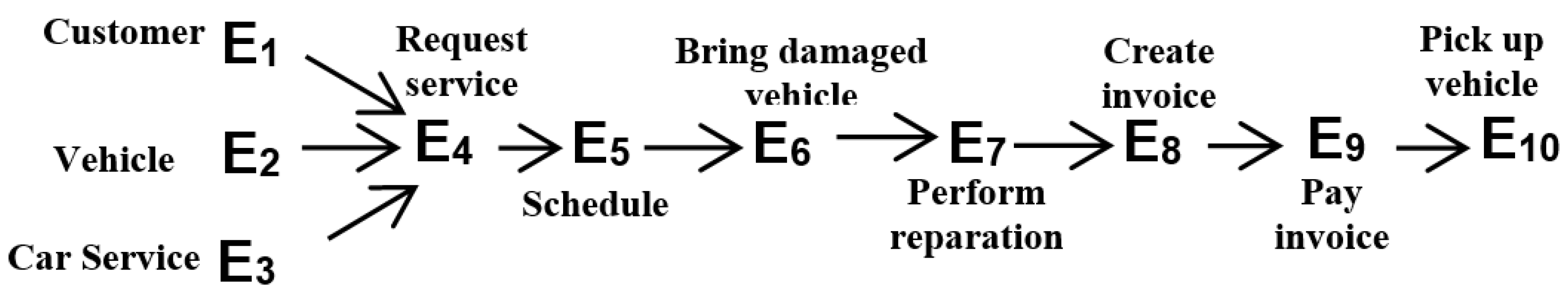

Venera [

25] selected to describe the processes involved by the reparations performed by a car service for the damaged vehicles brought by their customers. The process begins with the request made by the customer to the car service for vehicle reparation. The car service schedules the reparation. When the reparation start day comes, the customer brings in his vehicle, and the car service performs the required reparations. When all the reparations are finished, the car service creates an invoice that must be paid by the customer in order to pick up his repaired vehicle (see

Figure 12).

In this section, we aim to contrast the general methodology of BPMN with TM modeling, especially with regard to representing processes. Apparently, it is an elaborate task because they are based, to a large extent, on factors such as understandability and appreciation of the notion of process theory. A straightforward way to accomplish that is to put different diagrammatic depictions side by side and judge them accordingly. Therefore, we will TM model Venera’s [

25] car service processes so that, at the end, we are able to observe and contrast the two models.

TM Modeling

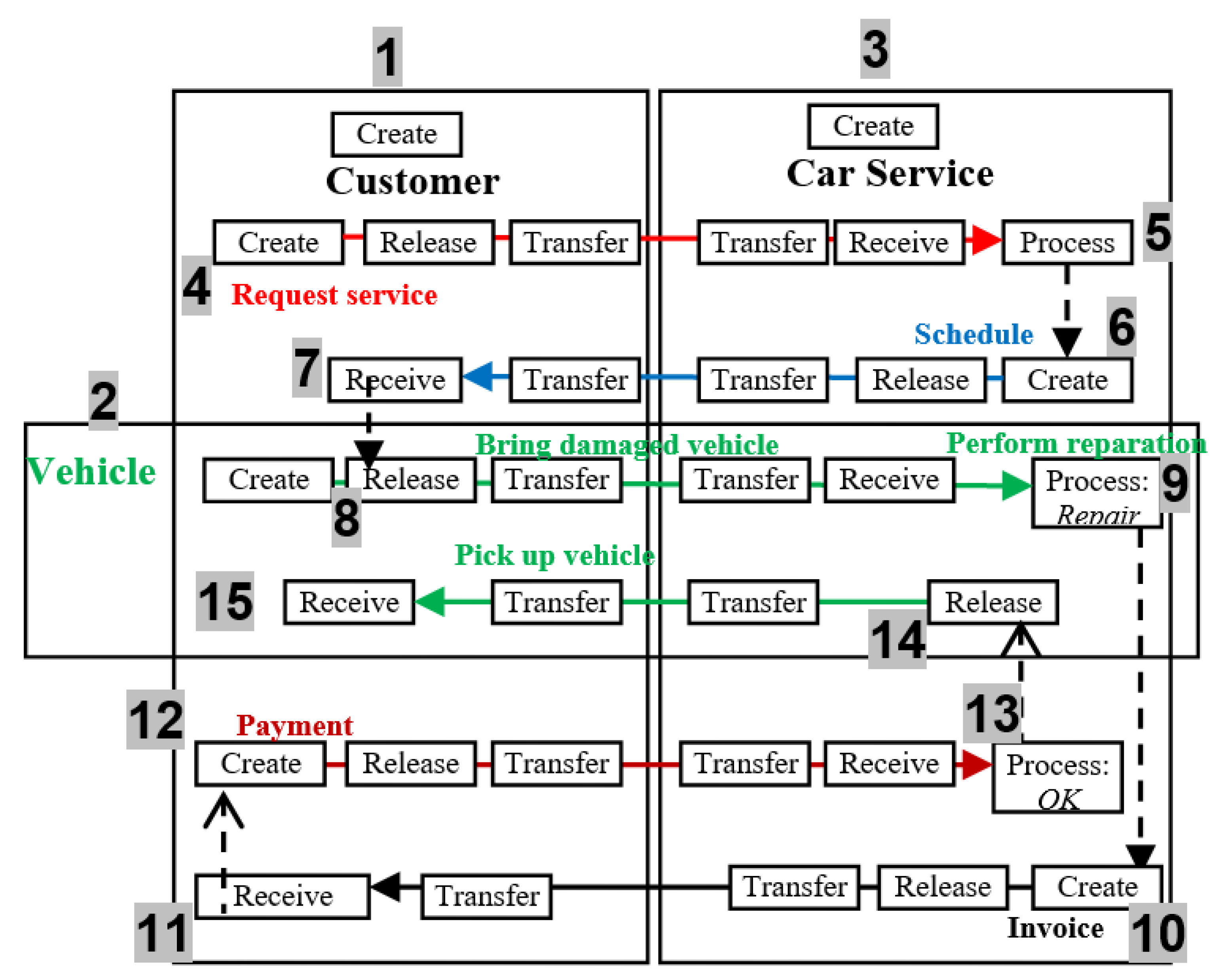

Figure 13 shows the TM static model, which is described as follows:

- The model involves three thimacs: customer, vehicle, and car service—indicated in the diagram by the numbers 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

- The customer generates and sends a request for a service

(4) that flows to the car service where it is processed (5) to

trigger the creation of a schedule appointment (6) that

flows to the customer (7).

Note that the schedule is a timing message and that reading it triggers the action of bringing the vehicle to the car service at the specified time.

- Accordingly, the customer brings the vehicle to the car service (8) where it is processed (9).

- Following the preparation, an invoice is issued (10) and sent to the customer (11).

- The customer generates a payment (12) that is received

by the car service (13).

- The customer picks up the car (14 and 15).

Note that, sometimes, for the sake of simplicity, the action create is omitted under the assumption that the rectangle of the thimac is sufficient to denote its presence.

First, this swinging process of going back and forth in

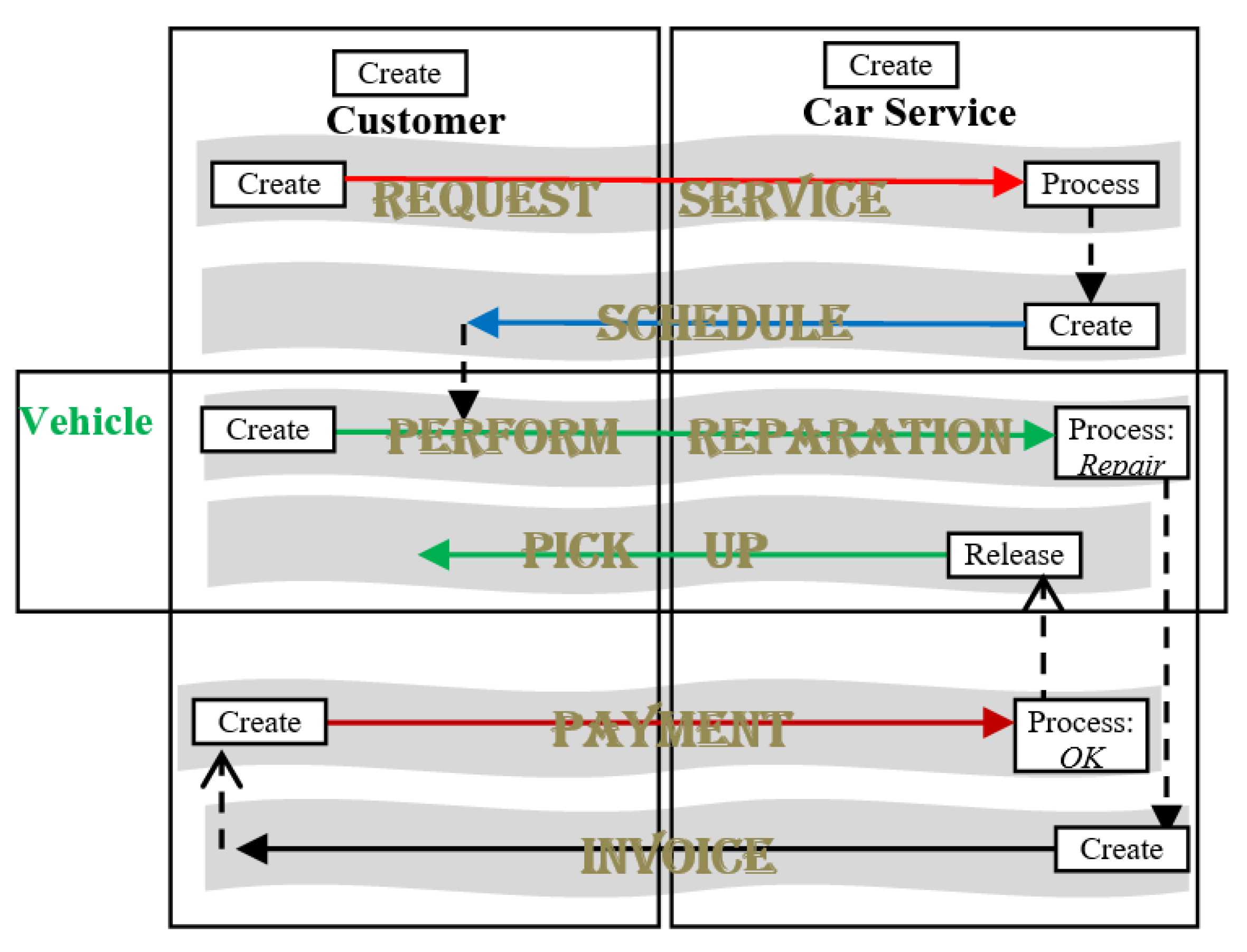

Figure 13 is reminiscent of Henri Bergson’s duration wherein he viewed a continuous flow of processes, such as swinging musical notes, thus reflecting a dynamic, evolving process rather than a collection of static notes. Additionally, for those who like simplicity,

Figure 13 can be simplified by eliminating release, transfer, and receive by assuming that the arrow direction is sufficient to indicate the flow in the diagram, as shown in

Figure 14.

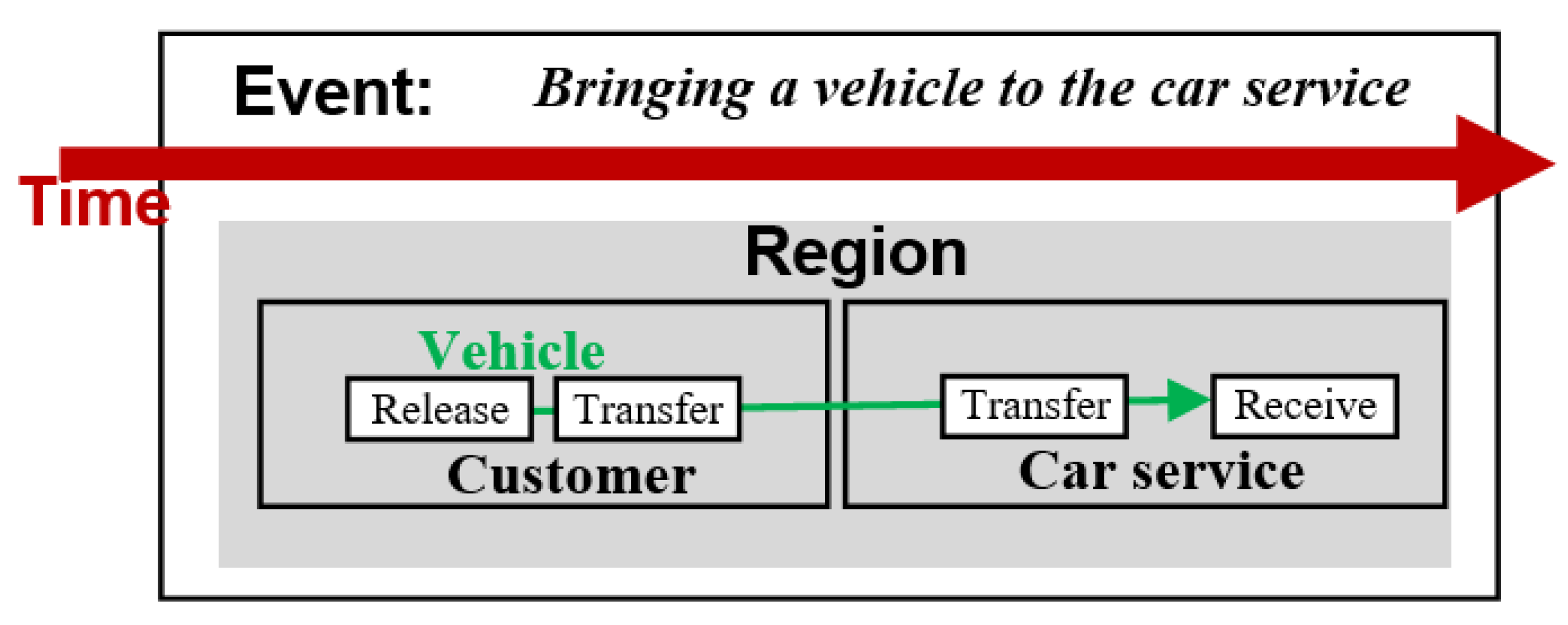

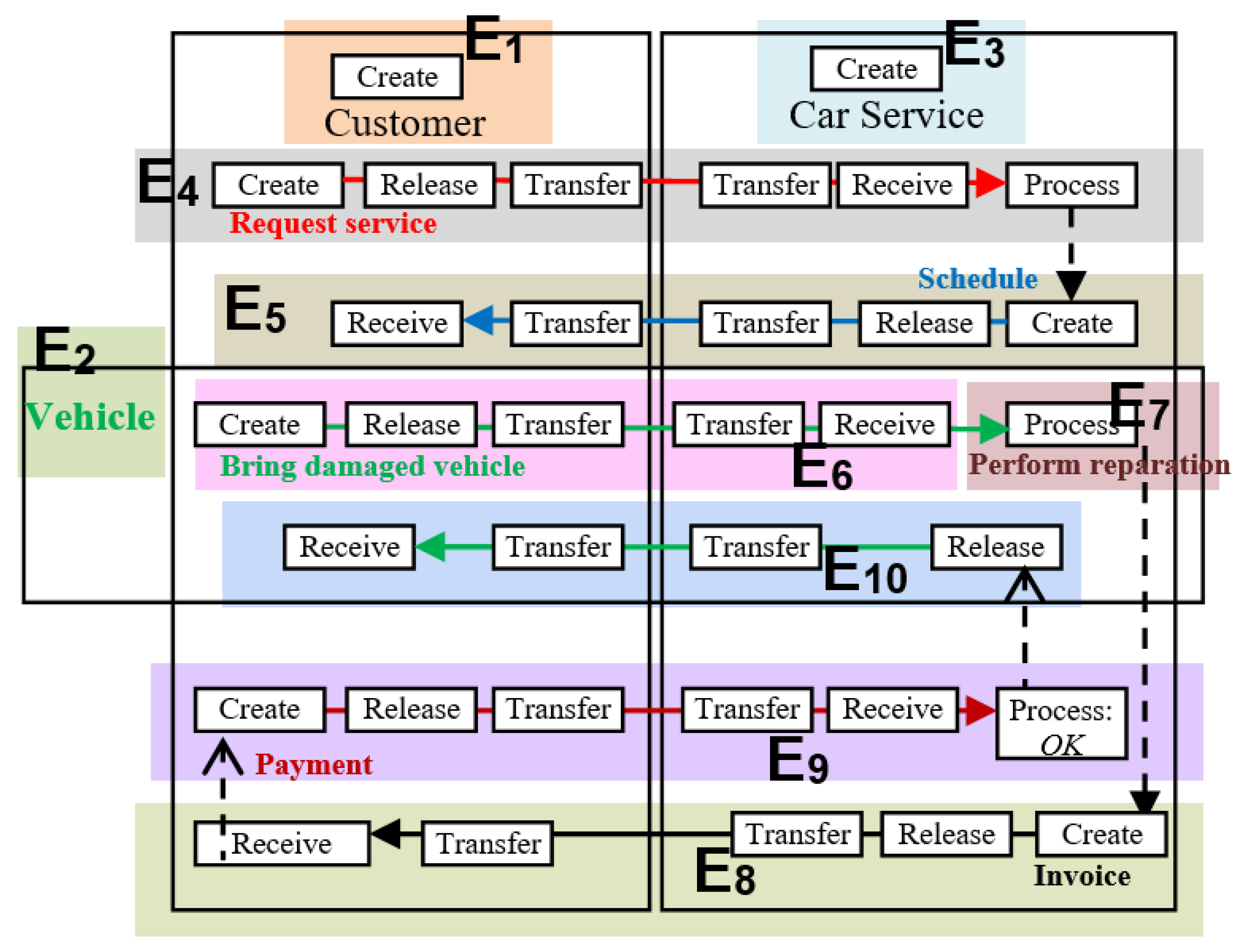

A TM event is defined in terms of a sub-diagram of the static model plus time.

Figure 15 shows the representation of the event

Bringing a vehicle to the car service.

Figure 16 shows a corresponding dynamic model where it is assumed that the region represents the event. It includes ten events, E

1, …, E

10, that partition the model. This means the dynamic model includes ten processes because we define processes in terms of events. In fact, the whole dynamic is a multitude of processes because we define processes as events.

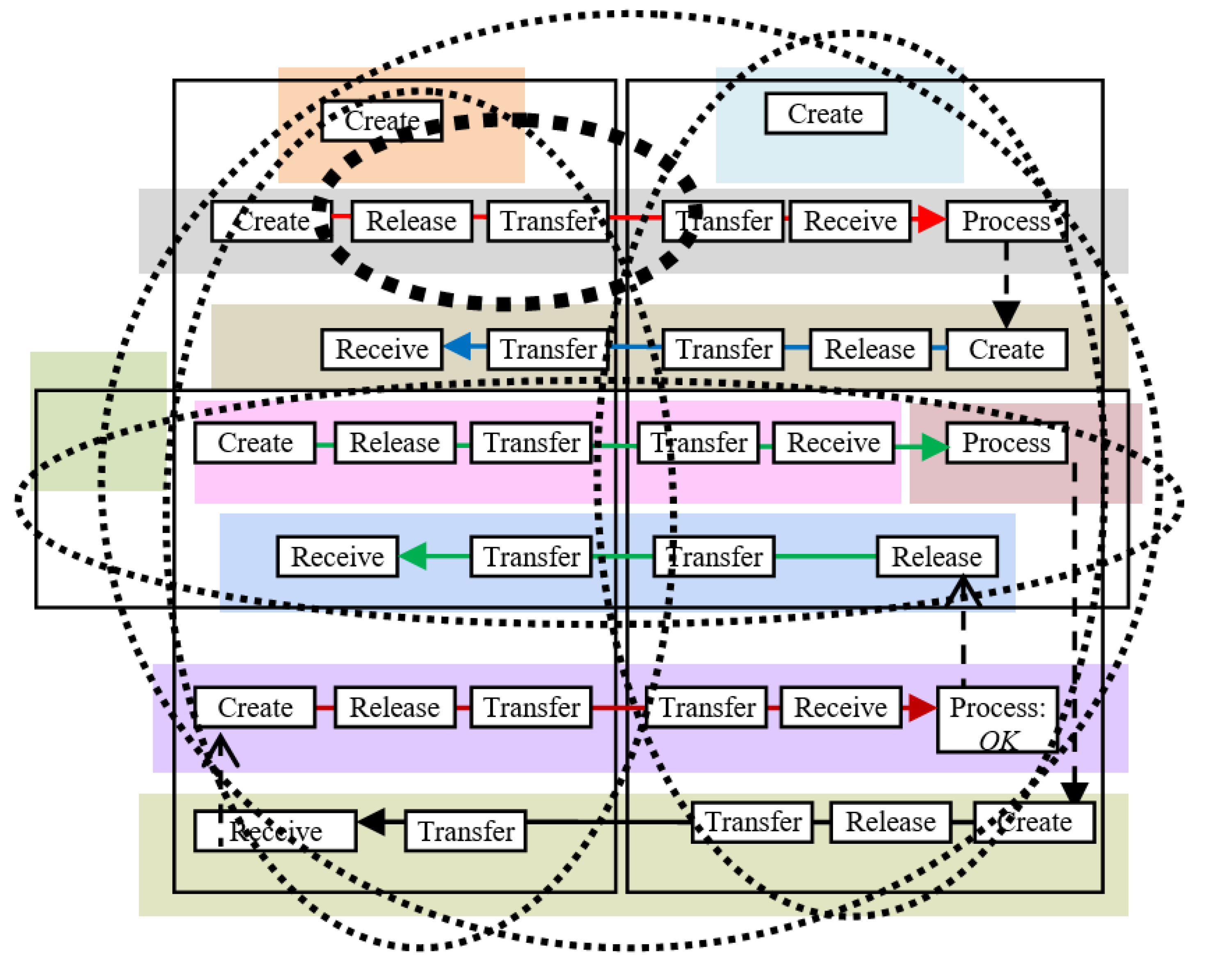

Figure 17 shows samples of these processes. First, there are generic processes that correspond to generic actions, and there are the selected processes E

1, …, E

10.

The complex process Customer denotes that all subprocesses relate to customer (e.g., The customer sends a request shown in thick ellipse). Finally, the whole dynamic model is a complex process, and the designer’s job is to select the appropriate set of sub-processes to represent the intended domain.

B. Process in BPMN: Example II

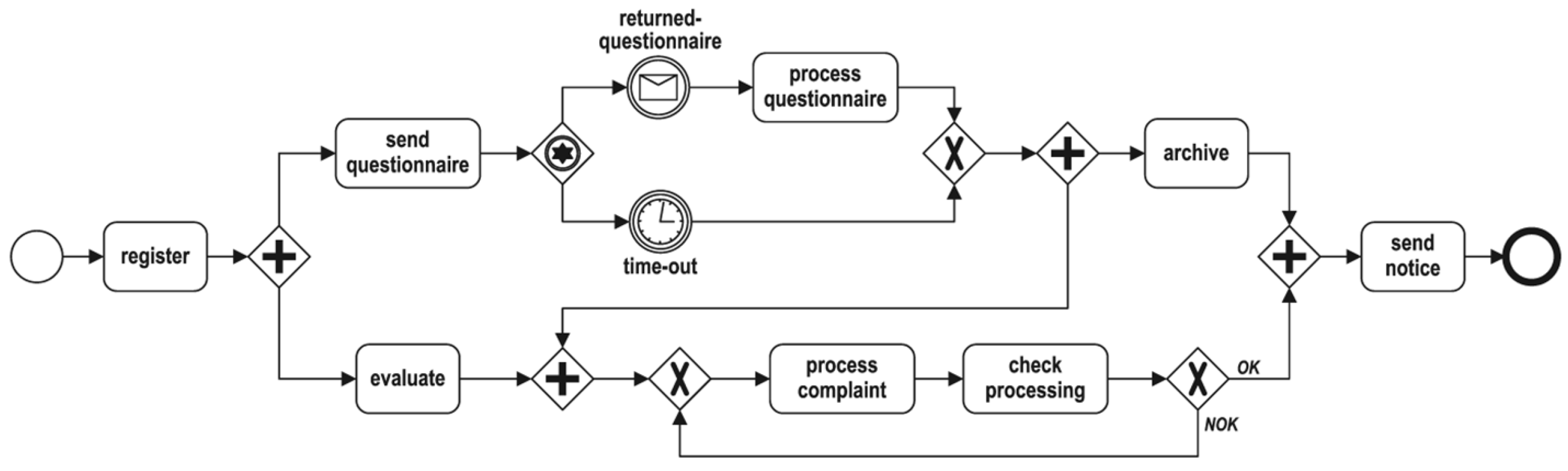

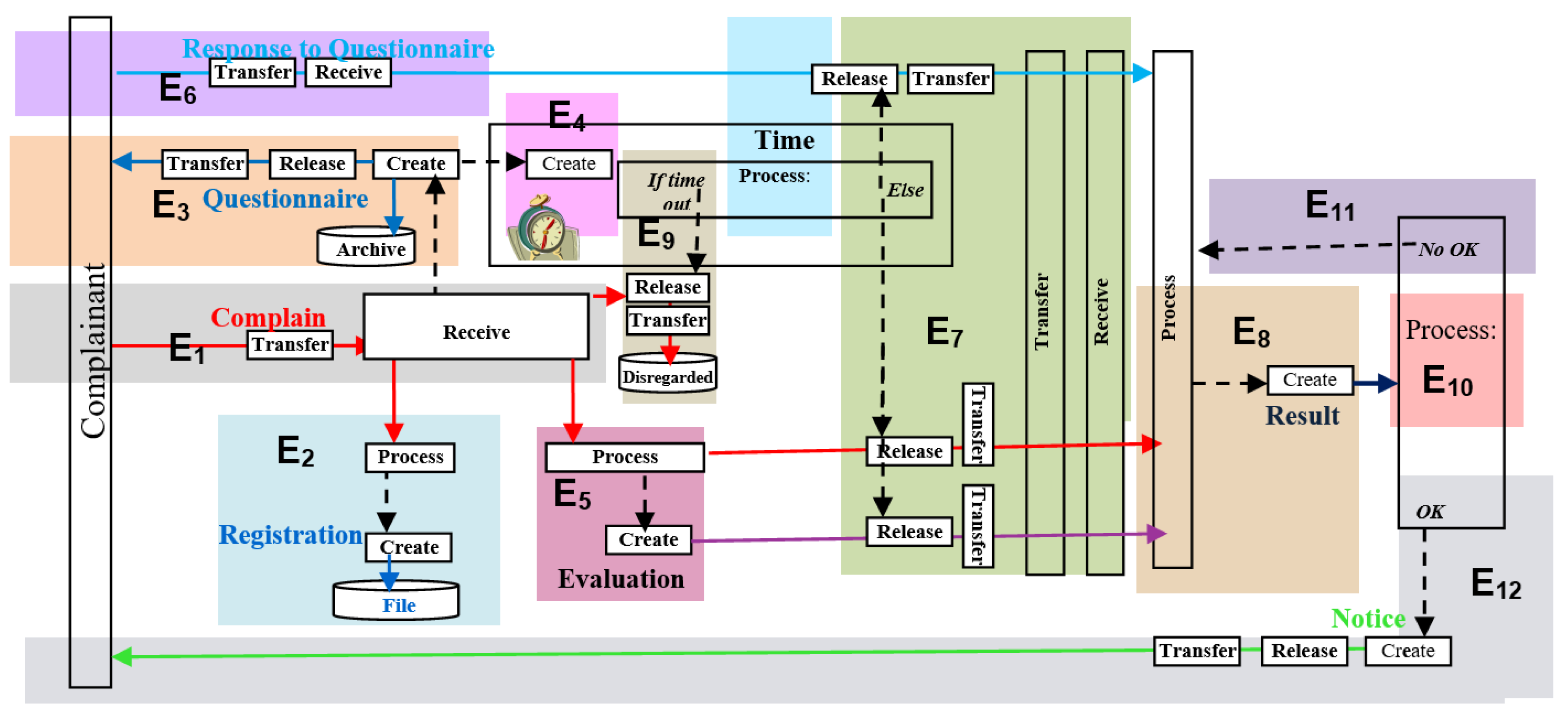

According to [

27], BPMN has attained a level of adoption among business analysts and system architects as a language for defining business process blueprints for subsequent implementation. The authors [

27] gave a sample BPMN complaint-handling process model, as shown in

Figure 19.

First, the complaint is registered (task register); then, in parallel, a questionnaire is sent to the complainant (task send questionnaire), and the complaint is evaluated (task evaluate). If the complainant returns the questionnaire within two weeks (event returned questionnaire), the task process questionnaire is executed. Otherwise (event time-out), the result of the questionnaire is discarded. After either the questionnaire is processed or a time-out has occurred, the result needs to be archived (task archive); in parallel, if the complaint evaluation has been completed, the actual processing of the complaint (task process complaint) can start. Next, the processing of the complaint is checked via task check processing.

If the check result is not okay, the complaint requires reprocessing. Otherwise, if the check result is okay, and the questionnaire has been archived, a notice will be sent to inform the complainant about the completion of the complaint handling (task send notice). Note that the labels okay and not okay on the outgoing flows of a data-based XOR decision gateway are abstract representations of conditions on these flows [

27].

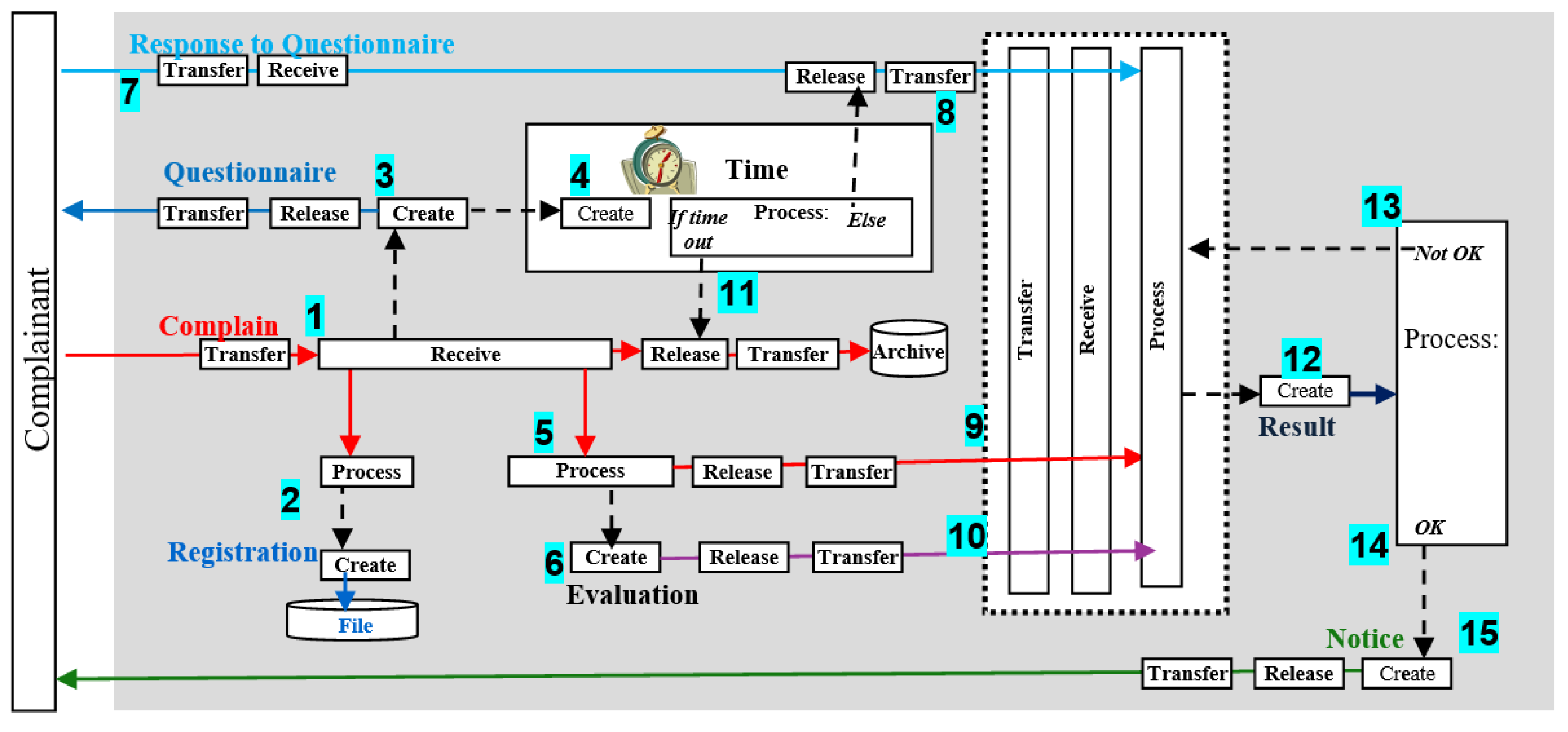

TM Static Model

The static model shown in

Figure 20 is described as follows:

- -

A complaint is received (1).

- -

The complaint is registered (2).

- -

A questionnaire is sent to the complainant (3), and a deadline for a response is set to two weeks (4).

- -

The complaint is processed (5) to generate an evaluation (6).

- -

The complainant responds to the questionnaire (7) within the deadline; hence, it is forwarded to be actually processed (8) along with the complaint (9) and evaluation (10).

- -

The deadline for a response has passed; hence, the questionnaire is discarded (11).

- -

The result of the actual processing of the complaint is checked (12).

- -

If the check result is not okay (13), the complaint requires reprocessing. Otherwise, if the check result is okay (14) and the questionnaire has been archived, a notice will be sent to inform the complainant (15) about the completion of the complaint handling.

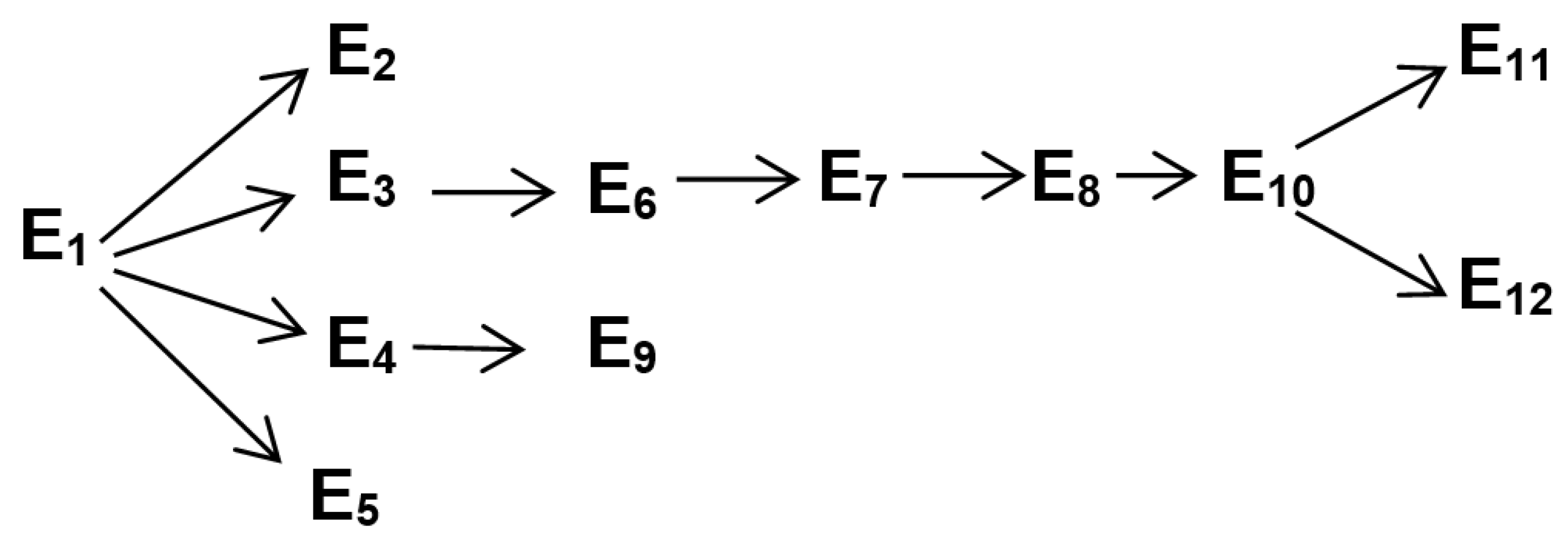

TM Dynamic Model

The dynamic model is shown in

Figure 21. The set of events is as follows:

- -

E1: A complaint is received.

- -

E2: A complaint is registered.

- -

E3: A questionnaire is sent to the complainant.

- -

E4: A deadline for a response is set to two weeks.

- -

E5: A complaint is processed to generate an evaluation.

- -

E6: The complainant responds to the questionnaire within the deadline.

- -

E7: A complaint’s response is forwarded to be actually processed along with its complaint copy and evaluation copy.

- -

E8: The actual process is executed for a complaint, and a result is generated.

- -

E9: The deadline for a complainant’s response has passed; hence, the questionnaire is discarded.

- -

E10: The result of the actual processing of the complaint is checked (12).

- -

E11: The result is not okay (13); hence, the complaint is reprocessed.

- -

E12: The result is okay, and the questionnaire has already been archived; hence, a notice is sent to inform the complainant about the completion of the complaint handling.

Figure 22 shows the chronology of events for the complaint

-handling process.

Conclusion

This study has an interdisciplinary perspective that serves such fields as software requirements, systems theory, ontology, process philosophy, and process techniques (e.g., a workflow). The purpose is building a foundation for conceptual modeling as a high-level representation of a targeted domain in reality. Specifically, the focus is on process-based conceptual modeling with the aim of providing a general application of the notion of process based on the conceptual representation called TM modeling.

We proposed to define the notion of process in terms of TM events because these events form a generalized apparatus of the idea of sequencing actions that transform inputs into outputs. This paper’s discussion reinforced the idea that processes are events. We showed that TM generic events are units of change. Changes (generic or complex) are processes per se in a larger sense. Such an understanding of processes is applied to BPMN samples. The result seems to indicate the viability of developing a pure process modeling notation.

References

- M. Mazzara, M. Farina, A. Krylová, E. Semenova, and M. Mohamed, “Software engineering as an alchemical process: establishing a philosophy of the discipline,” Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci., vol. 1523, pp. 12-31, 2021, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11023-011-9234-2.

- SFGPage, Transitivity, accessed July 2025, https://www.alvinleong.info/sfg/sfgtrans.html#:~:text=A%20material%20process%20is%20a,%22%20or%20%22what%20happened%3F%22&text=Because%20the%20material%20process%20involves,was%20playing%20ping%20pong%20yesterday%22.

- P. Senkus, W. Glabiszwski, A. Wysokińska-Senkus, and A. Pańka, “Process definitions - critical literature review,” Eur. Res. Stud., vol. XXIV, no. 3, pp. 241-255, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Seibt, “Free process theory: towards a typology of occurrings,” Axiomathes, vol. 14, pp. 23-55, 2004, https://www.academia.edu/59939726/Free_Process_Theory_Towards_a_Typology_of_Occurrings.

- N. Rescher, Process Metaphysics: An Introduction to Process Philosophy, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996, https://compress-pdf-free.obar.info/download/compresspdf.

- K. C. Masong, “Recuperating the concept of event in the early whitehead,” Hapág, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 31-46, 2014, https://philarchive.org/archive/MASRTC-3.

- J. Heaton and N. Simon, “What is the nature of the distinction between events and processes?” (Thesis), Department of Philosophy, Birkbeck College, The University of London, 2014, https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40087/1/Jasper%20Noel%20Simon%20Heaton%2012804862%20MPhilStud%20Thesis%20What%20is%20the%20Nature%20of%20the%20Distinction%20between%20Events%20and%20Processes.pdf.

- H. Steward, The Ontology of Mind: Events, Processes, and States, Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1997, https://epdf.pub/queue/the-ontology-of-mind-events-processes-and-states-oxford-philosophical-monographs.html.

- S. Al-Fedaghi, “Preconceptual modeling in software engineering: metaphysics of diagrammatic representations,” HAL Archives, 2024, https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-04576184.

- G. P. Adams, “The relation between form and process,” Univ. Calif. Publ. Phil., vol. 13, pp. 191-217, 1930.

- 11. R. N. Prasad and Seema Acharya, “Multidimensional data modeling, chapter 7,” in Fundamentals of Business Analytics, Wiley: Pvt. Ltd., January 1, 2016.

- M. L. Gill, “Aristotle’s distinction between change and activity,” Axiomathes, vol. 14, pp. 3-22, 2004.

- L. B. McHenry, The Event Universe: The Revisionary Metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015. [CrossRef]

- P. M. S. Hacker, “Events and objects in space and time, mind,” Mind, vol. 91 (361), pp. 1-19, 1982. [CrossRef]

- A. F. Holmes, “A synopsis of process philosophy,” Systems, Design and Inquiry, September 18, 2016, https://csl4d.wordpress.com/2016/09/18/a-synopsis-of-process-philosophy/.

- S. Mumford, “’What is a change?’, metaphysics: a very short introduction,” in Very Short Introductions , Oxford, UK: Oxford Academic, 2013.

- G. Gori, “The solution of the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise,” Accessed July 15, 2025, https://gori70.medium.com/the-solution-of-the-paradox-of-achilles-and-the-tortoise-f618b23c25e.

- N. Huggett, “Zeno’s paradoxes,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2024 Edition), E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman, Eds. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2024/entries/paradox-zeno/.

- S. Perkowitz, “Special relativity,” Encyclopedia Britannica, June 21, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/science/relativity/Intellectual-and-cultural-impact-of-relativity.

- S. Al-Fedaghi, “Exploring conceptual modeling metaphysics: existence containers, Leibniz’s monads and Avicenna’s essence,” arXiv preprint, arXiv:2405.01549, February 20, 2024.

- H. Bergson, Duration and Simultaneity, New York, NY: Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc., 1965, https://dn790008.ca.archive.org/0/items/DurationAndSimultaneityHenriBergson/Duration%20and%20Simultaneity_Henri%20Bergson_text.pdf.

- L. Vinck, “Revisiting the Einstein–Bergson debate” (Online manuscript), no date, https://philarchive.org/archive/VINRTE.

- T. H. Davenport and J. E. Short, “The New Industrial Engineering: Information Technology and Business Process Redesign,” Sloan Manag. Rev, pp. 11-27, 1990.

- M. Bandor, “Process and procedure definition: a primer,” CMU SIE, 2007, https://insights.sei.cmu.edu/documents/3263/2007_017_001_23937.pdf.

- C. Venera, “Geambaşu, BPMN vs. UML activity diagram for business process modeling,” Acc. Manag. Inf. Syst., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 637-651, 2012.

- A. Catalano, M. Magnani, and D. Montesi, “Modeling with BPMN and Chorda: a top-down, data-driven methodology and tool,” 11th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Information Systems Analysis and Specification, pp. 389-392, 2009.

- C. Ouyang, M. Dumas, A. H. M. ter Hofstede, and W. M. P. van der Aalst, “Pattern-based translation of BPMN process models to BPEL web services,” Int. J. Web Serv. Res., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 42-62, 2007, https://www.vdaalst.com/publications/p427.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).