1. Introduction

Virtual Reality (VR) has become a powerful learning environment, enhancing engagement, comprehension, and retention, in engineering higher education. [

1,

2,

3,

4] It offers a transformative opportunity to enhance educational experiences through personalized approaches tailored to individual learning styles. As educators adapt instructional methods to accommodate diverse cognitive preferences, understanding the complex interplay between learning styles, cognitive load, and outcomes becomes paramount. Researchers highlight that internal learner factors, such as the ability to absorb and process information, significantly influence knowledge acquisition in VR environments [

5].

Research on learning styles and VR shows mixed results. Some studies find that learning styles may affect the sense of presence and cognitive load in VR environments [

6] and highlight benefits for concrete or sensing-type learners [

7,

8]. Other research suggests learning styles do not significantly influence VR learning outcomes [

9,

10]. In relation with the learning factors, studies indicate that VR has a strong potential to induce flow, which is positively associated with continued use of VR [

11]. Flow experience mediates the impact of VR immersion on learning outcomes, enhancing motivation, curiosity, and cognitive benefits [

12].

While the educational community continues to debate the prescriptive value of learning style models and on the learning, factors influencing VR efficiency, this study approaches learning preferences not as rigid labels, but as flexible cognitive tendencies. We argue that the highly sensorimotor and immersive nature of VR creates a unique context where these underlying preferences in perceiving and processing information become more pronounced, influencing engagement and flow. Thus, our research explores these relationships to inform more adaptive VR learning design, rather than to validate the learning style models themselves.

The custom-built VR environment, namely Submarine Simulator software, has been developed to support and enhance the process of learning underwater engineering by enabling users to create 3D models of small-scale submarines and rigorously test them in a realistic simulated underwater setting.

This interdisciplinary approach aims to bring contributions to understanding the underlying factors for learning efficiency, but also to developing new educational VR tools, by answering the following research questions:

To what extent do immersive engagement and flow state mediate the relationship between learning styles and learning outcomes in a VR-based Submarine Simulator?

How does the quality of the VR software influence students’ performance across different learning styles in a VR-based learning environment?

2. Learning Styles in VR

Learning styles refer to the observable strategies and preferences learners use in educational contexts [

13]. Comprehensive reviews have analysed various learning style models and their implications for learning process [

14,

15,

16]. Recognizing and understanding diverse learning styles enables learners to customize their study techniques and empowers educators to adapt their teaching methods, fostering greater engagement and deeper comprehension.

Personalized learning in virtual reality (VR) demonstrates considerable potential, particularly when adapted to individual learners’ preferences and cognitive characteristics, as it supports individual variability and contributes to improved educational outcomes [

9,

17].

Investigating the effects of a virtual reality (VR)-based learning environment on learners with different learning styles, specialists found that there was no significant difference in the cognitive and affective learning outcomes for students with different learning styles in a VR-based learning environment [

9,

10,

18]. This demonstrates that VR-based learning environments hold significant potential for accommodating diverse learning styles and individual differences.

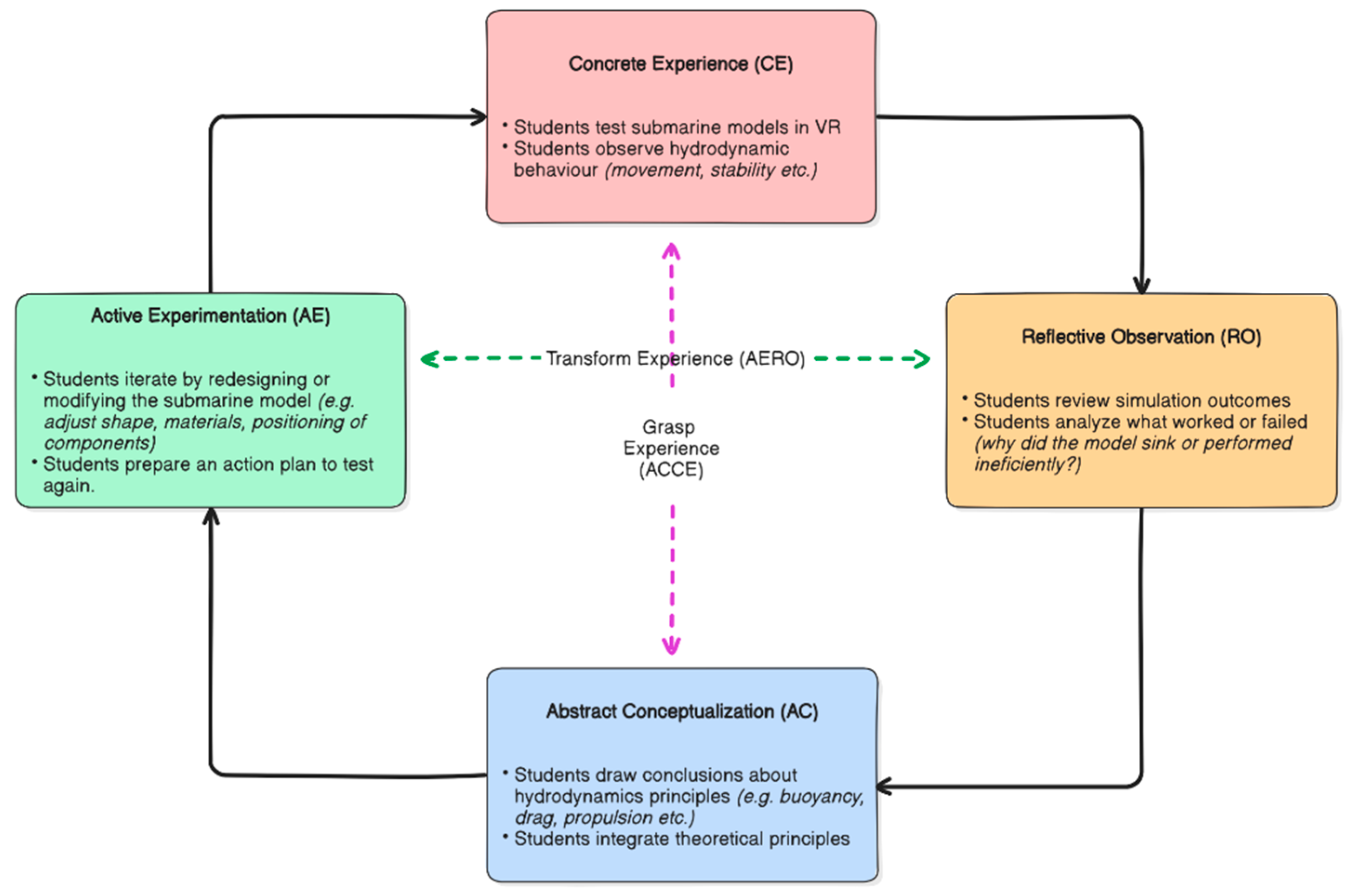

The application of Kolb’s experiential learning cycle (1984) in designing VR activities has been proposed to align experiences with learner profiles [

8] and to enhance student learning outcomes [

19,

20]. Different studies have integrated Kolb’s experiential learning model with VR to investigate factors affecting students’ intention to use VR in learning [

8] and to design personalized VR workspaces [

21]. In Kolb-based designs, concrete experience appears to drive behavioural intention and adoption, as in combined Kolb’s model with the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) to investigate students’ intention to use VR [

8]. Overall, research suggests that Kolb-based learning in VR improves motivation, intention to use, and even test performance [

8,

19,

21].

Kolb’s experiential learning theory outlines a four-stage cycle: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. While Kolb’s original experiential learning model defined four primary learning styles—Diverging, Assimilating, Converging, and Accommodating—these stem from earlier iterations of his theory. In more recent updates, particularly with the Kolb Learning Style Inventory (KLSI) 4.0, Kolb has refined and expanded this framework into nine styles to provide greater granularity across the learning quadrants: Experiencing, Imagining, Reflecting, Analysing, Thinking, Deciding, Acting, Initiating, and Balancing. Each learning style represents an individual’s preference for a distinct phase of Kolb’s learning cycle, shaped by how they engage with, reflect on, conceptualize, and experiment with new information. Some research suggests that VR may benefit certain learning styles, such as concrete experiential learners [

8] and sensing-type learners [

7].

While learning styles may not directly impact outcomes, they can affect students’ sense of presence and cognitive load in VR [

6]. Overall, VR appears to offer potential benefits for learners across different styles, and new research will contribute to fully understand its impact on diverse learning preferences [

22].

3. VR as a Learning Environment: Flow and Personalization

A key aspect related to learning styles is the flow state, which plays a critical role in optimizing the learning process. Flow in VR is characterized by deep absorption, loss of time perception, and improved performance [

23]. VR provides immersive, interactive experiences that enhance learners’ engagement and motivation. Studies show that VR strongly supports the flow experience, which is associated with improved motivation and performance [

11,

12]. Immersion is a prerequisite for achieving flow, significantly impacting user satisfaction and the intention to continue engaging with VR environments. [

11,

24].

The experience of flow in VR can explain the relationship between VR visualization technology and learning outcomes [

25]. Incorporating flow theory principles in VR design may optimize the learning state and the leaning performance, through cognitive absorption [

17]. These findings highlight the importance of considering individual cognitive differences in VR design and research.

At the same time, spatial design in VR environments can influence cognitive load, although evidence suggests minimal impact on spatial reasoning tasks [

26]. However, the design can still play a role in enhancing learning efficacy by providing immersive and engaging experiences [

26]. Adaptive VR learning systems that align with individual learning styles can enhance motivation and improve learning outcomes by minimizing extraneous cognitive load while optimizing relevant cognitive engagement [

27].

Other individual cognitive-personal factors, such as spatial thinking and field dependence, can affect task performance in VR, with spatial cognitive load playing a significant role in learning success [

28]. The use of eye-tracking and physiological data in VR can help tailor cognitive workload to the learner’s ability, ensuring the task is neither too challenging nor too easy, which is crucial for learners with varying intelligence levels [

29].

In engineering education, VR systems are designed to cater to individual learning preferences, enhancing student engagement and performance [

30]. Research indicates that while learning styles do not significantly affect learning performance in VR, they do influence attention levels, with visual learners showing higher attention than verbal learners [

31].

Starting by these premises and by applying Kolb’s experiential learning principles, we seek to explore how customized VR experiences can enhance personalization, increase engagement, and improve educational outcomes, ultimately fostering more adaptive and effective instructional strategies in engineering higher education.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Aim

In this study, we leverage Kolb’s experiential learning framework to assess the instructional effectiveness of VR software applications within the field of underwater engineering. Specifically, we employ Kolb’s model to examine how diverse learning styles interact with immersive environments, influencing knowledge acquisition and skill development. Drawing on the framework’s evolution, including its refined nine-style granularity (Experiencing, Imagining, Reflecting, Analysing, Thinking, Deciding, Acting, Initiating, and Balancing), our investigation evaluates these styles in relation to flow states, satisfaction in VR use and learning outcomes among engineering students.

The Submarine Simulator VR software was custom-developed for this study to provide a dedicated pedagogical platform that integrates three key elements: a realistic underwater physics engine for authentic hydrodynamic feedback, an in-VR 3D modeling toolkit that allows for direct hands-on design and iteration, and a gamified competitive framework featuring head-to-head racing challenges.

4.2. Hypothesis

We tested the following hypothesis:

H1. The perceived quality of the VR learning environment, in conjunction with students’ learning styles, significantly predict the level of immersive engagement and the overall satisfaction of the learning experience.

H2. Learning styles significantly influence students’ performance in the VR-based Submarine Simulator.

H3. Immersive engagement and the flow state in VR mediates the relationship between learning styles and learning outcomes.

H4. Learning styles significantly influence students perceived immersion and flow state in the VR-based Submarine Simulator.

H5. Students’ performance in VR conditions are influenced by the perceived quality of VR software.

4.3. Target Group

The research protocol was tested on a group of 26 students, in their 4th year at MINES Paris - PSL, during the underwater engineering course. The course was conducted on a full-time basis over a 10-week on-campus period, during which students were not enrolled in any other courses. Each student completed all three phases described in the research protocol (subchapter 4.5). Following each phase, the facilitator conducted a brief 10-minute interview to ensure the experience was well-received, confirming that students enjoyed the session and felt comfortable, without experiencing nausea or discomfort.

All students signed an agreement to participate in research protocol and were informed that during the research and their dissemination the anonymity of the participants will be respected. For the reference purposes, during the phase of data processing stage, only randomly assigned numerical codes have been used. The characteristics of the group, from the point of view of the learning styles, flow, immersion, satisfaction and performance. are presented in Appendix 2.

4.4. Methods

To highlight the research variables, the following instruments and tests were used:

- 1.

-

The Kolb Experiential Learning Profile (KELP) is a practical self-assessment instrument that can help us assess our unique learning styles and has the advantage of only taking 15-25 minutes to complete [

32]. Based on the results of the test, students have received a scored on the following four quadrants, describing how they process and transform experiences into knowledge:

- (1)

Concrete Experience (CE) - Learners immerse themselves fully, openly, and without preconceived biases in novel experiences, emphasizing direct involvement and sensory engagement.

- (2)

Reflective Observation (RO) - They contemplate and examine these experiences from diverse viewpoints, fostering introspection and nuanced understanding.

- (3)

Abstract Conceptualisation (AC) - They synthesize observations into coherent concepts, forming logically robust theories that explain patterns and relationships.

- (4)

Active Experimentation (AE) - They apply these theories practically to inform decision-making and address real-world problems, testing ideas through action.

Drawing from these quadrants, Kolb’s refined framework identifies nine distinct learning styles, each offering greater granularity and reflecting unique preferences in how individuals navigate the learning cycle: experiencing; imagining; reflecting; analyzing; thinking; deciding; acting; initiating; balancing (Appendix 1). The analysis of the questionnaire involved characterizing the group in terms of learning dimensions, learning styles, and flex learning styles.

Learning styles are determined by an individual’s preferences along two key bipolar dimensions, which are calculated as difference scores from questionnaire responses. These dimensions capture how people balance opposing approaches to perceiving (grasping information) and processing (transforming information): ACCE (Abstract Conceptualization minus Concrete Experience) and AERO (Active Experimentation minus Reflective Observation) (Appendix 1).

In Kolb’s experiential learning theory, a student’s primary learning style reflects their preferred approach to the learning cycle. This primary style is a preference, not a rigid limitation, indicating where a learner naturally feels most comfortable. Alongside this, students exhibit flex styles where they also perform effectively, showcasing their adaptability. Non-flex styles, or developing styles, are areas where learners are less proficient but can improve through practice and self-awareness, leading to a more complete and balanced learning profile.

- 2.

-

The Flow State Scale (FSS), developed by Jackson and Marsh (1996), is a 36-item psychometric tool designed to measure the nine dimensions of flow as outlined by Csikszentmihalyi, capturing the optimal psychological state of complete immersion and engagement in an activity [

33]. These dimensions include:

Challenge-Skill Balance: Perceiving that personal skills match the task’s demands.

Action-Awareness Merging: Experiencing seamless integration of actions and awareness.

Clear Goals: Having a clear understanding of objectives.

Unambiguous Feedback: Receiving immediate, clear feedback on performance.

Concentration on the Task: Maintaining deep focus without distractions.

Sense of Control: Feeling in command of the activity.

Loss of Self-Consciousness: Becoming less aware of self and external judgments.

Transformation of Time: Perceiving time as altered, either speeding up or slowing down.

Autotelic Experience: Finding the activity intrinsically rewarding.

Each dimension is assessed through four items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), enabling precise measurement of flow intensity. The FSS’s use in this study was approved by Mind Garden, Inc., on March 6, 2024, ensuring ethical compliance.

For each dimension, the four item scores are summed and divided by four to calculate an average score. This method quantifies flow experiences, facilitating analysis of their relationship with learning styles and performance outcomes in immersive VR settings like the Submarine Simulator, where engagement is key to learning.

- 3.

Immersive Tendencies Questionnaire (ITQ) was developed by Bob G. Witmer and Michael J. Singer (1998) and it was designed to assess an individual’s inherent propensity or tendency to become immersed in everyday activities, media, and environmental situations, particularly as a predictor of how readily they might experience presence in virtual environments (VEs) [

34]. Presence, in this context, refers to the psychological state of feeling "there" in a mediated or simulated environment, and the ITQ aims to capture individual differences that could influence immersion levels. It is typically administered prior to VE exposure to stratify participants, predict performance, or identify factors contributing to immersion, such as involvement in activities like reading, watching movies, or playing games. The questionnaire is supported by correlations with related measures like the Tellegen Absorption Scale (r ≈ .40-.60). Factor analysis in follow-up research confirms loadings on immersion-related constructs. Higher ITQ scores have been linked to better VE performance and higher presence ratings in some studies. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert-type, higher scores indicate stronger immersive tendencies.

- 4.

The Basic Needs in Games (BANG) scale is an open-access, free-to-use questionnaire developed to evaluate the satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—experienced by players during video game play, rooted in Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [

35]. The BANG scale includes six subscales—three assessing satisfaction (autonomy, competence, relatedness) and three measuring frustration—allowing researchers to compute mean scores for each need separately, offering detailed and interpretable insights into how well a game supports these psychological needs.

The "Satisfaction" dimension of the BANG results measures the fulfilment of three core needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—which significantly enhance player enjoyment, engagement, and psychological well-being. Autonomy satisfaction arises from players’ control over meaningful choices, competence satisfaction from mastering challenges and achieving goals, and relatedness satisfaction from forming social connections with others, including players and non-player characters. Fulfilling these needs fosters motivation, immersion, and sustained engagement, contributing to a rewarding gaming experience.

The scale has been statistically validated through rigorous psychometric testing, with initial studies demonstrating good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha values typically exceeding 0.80 for the satisfaction subscales) and construct validity, confirmed through factor analysis that aligns with SDT constructs. Furthermore, its reliability and applicability have been supported across diverse gaming contexts and populations, with ongoing research continuing to refine its sensitivity and predictive power.

This validation ensures that the BANG scale provides a robust tool for researchers and designers to assess and enhance the psychological impact of games, making the "Satisfaction" dimension a critical metric for optimizing player-centered design in virtual environments.

- 5.

-

Scoring on the Performance - to examine the interplay between learning styles, immersion and flow states, and learning outcomes in the Submarine Simulator VR environment, a tailored scoring system was established. This system draws on the distinct tasks across the three phases of software interaction, assigning scores that capture objective performance in each phase:

Phase 1 (Basic Submarine Construction and Testing, scored on a 0–20 Scale): This structured phase emphasizes foundational building and initial testing.

Phase 2 (Designing Tight and Loose Spiral Models, scored on a 0–2 Scale): Focused on strategic planning and iterative refinement, the binary scoring reflects a pass/fail mechanism for the two required models: 2 points for successfully completing both, 1 point for one, and 0 points for none.

Phase 3 (Competitive Racing on Tracks, scored on a 0–20 Scale): This dynamic phase demands real-time adaptation and quick decision-making. The scoring system was designed to be simple yet engaging. Points were awarded in accordance with finishing the race on each track, with 1 point for Track 1, 2 points for Track 2, and 3 points for the more complex Track 3. Additional points would be awarded after winning the race against an opponent.

Statistical methods. A Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM) [

36] was employed to examine whether virtual reality (VR) experience—including Flow, Immersion, Satisfaction and Mindset—mediates the relationship between learning styles and learning performance across three instructional phases (Points1, Points2, Points3). As a valuable for understanding causal processes and testing mediation effects, SEM analysis combines aspects of factor analysis – learning styles components, cognitive, affective and mindset aspects, and path analysis to test and to assess the relationships among variables.

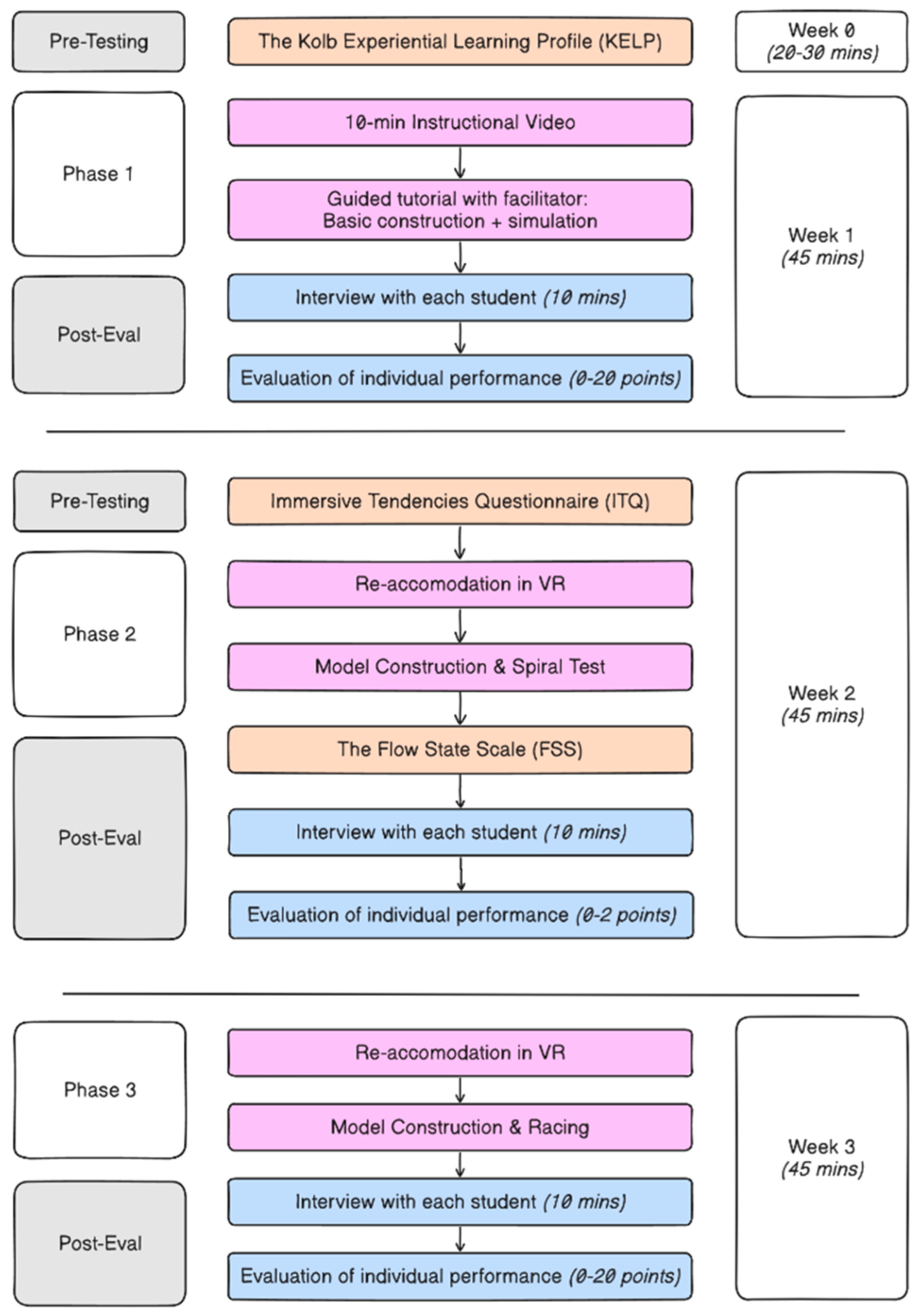

4.5. Research Protocol

To investigate the interplay between learning styles, flow state, and learning outcomes within the immersive VR environment of the

Submarine Simulator software application—a custom tool designed for underwater engineering education—we developed a structured research protocol. This protocol comprises sequential phases meticulously aligned with Kolb’s experiential learning cycle (Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation), ensuring a holistic approach that accommodates diverse learner preferences and promotes deeper engagement. (

Figure 1)

The VR simulation replicates authentic hydrodynamics and intricate underwater physics, posing challenges that are hard to envision or grasp without immersive tools. This cutting-edge and novel VR environment presents a unique challenge for participants, most of whom have little to no prior experience with VR technology or advanced underwater simulations. It demands a seamless blend of creative problem-solving and precise interaction, pushing the boundaries of realistic 3D modelling and navigation tasks. By mirroring Kolb’s framework, the protocol not only facilitates hands-on interaction but also encourages reflection, theoretical integration, and practical application, ultimately aiming to quantify how these elements influence knowledge acquisition, skill retention, and motivational flow in a simulated submarine modelling and testing scenario. The protocol unfolds in four primary phases, as detailed in

Table 1.

The learning outcomes are assessed through repeated VR sessions, enabling the evaluation of improvements in engineering competencies, such as problem-solving and technical precision. This dynamic process, rooted in Kolb’s learning cycle, fosters adaptive learning in the novel VR context, where participants can test hypotheses and refine skills in a realistic, immersive setting, ultimately strengthening their ability to tackle complex engineering challenges.

4.6. Research Design

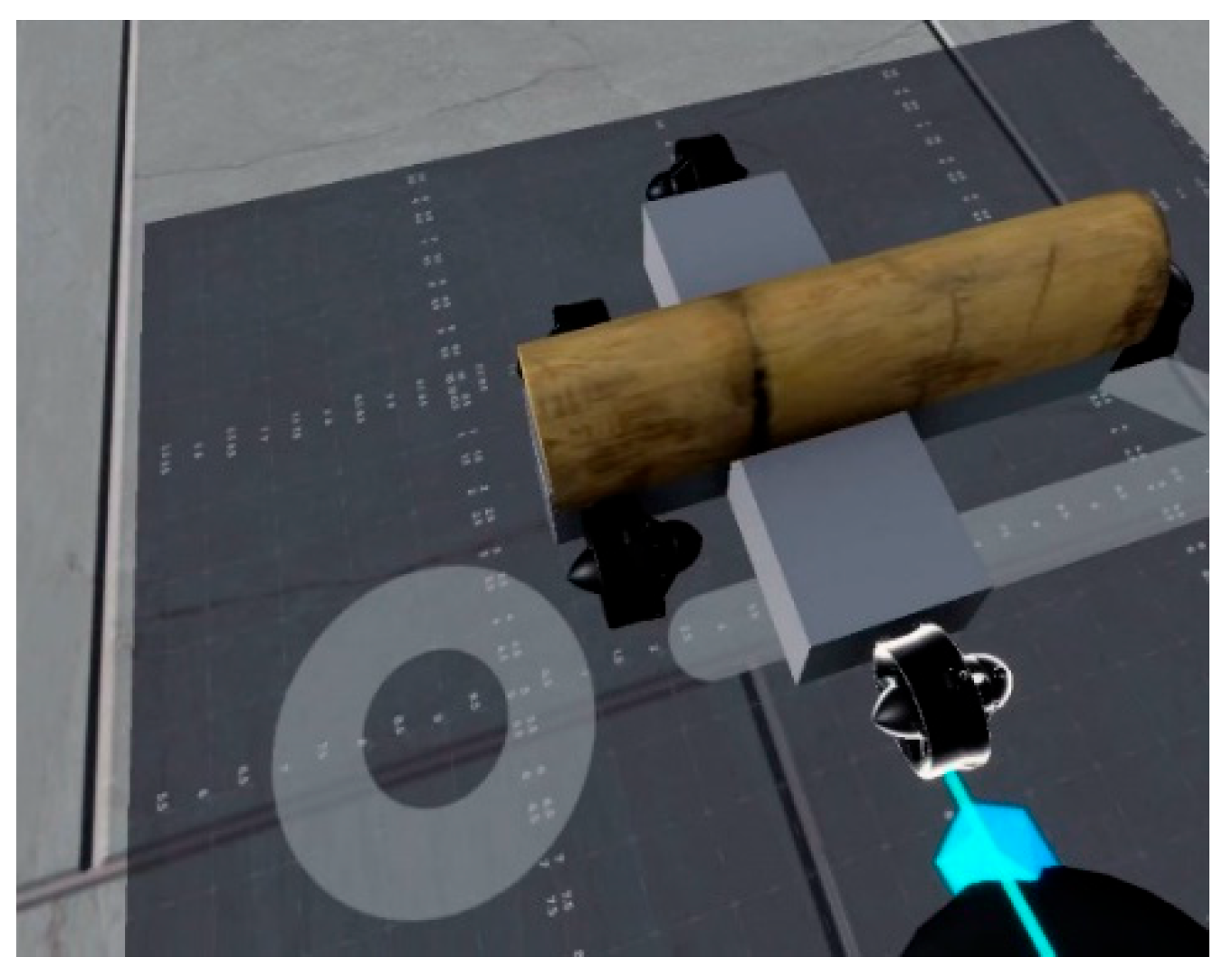

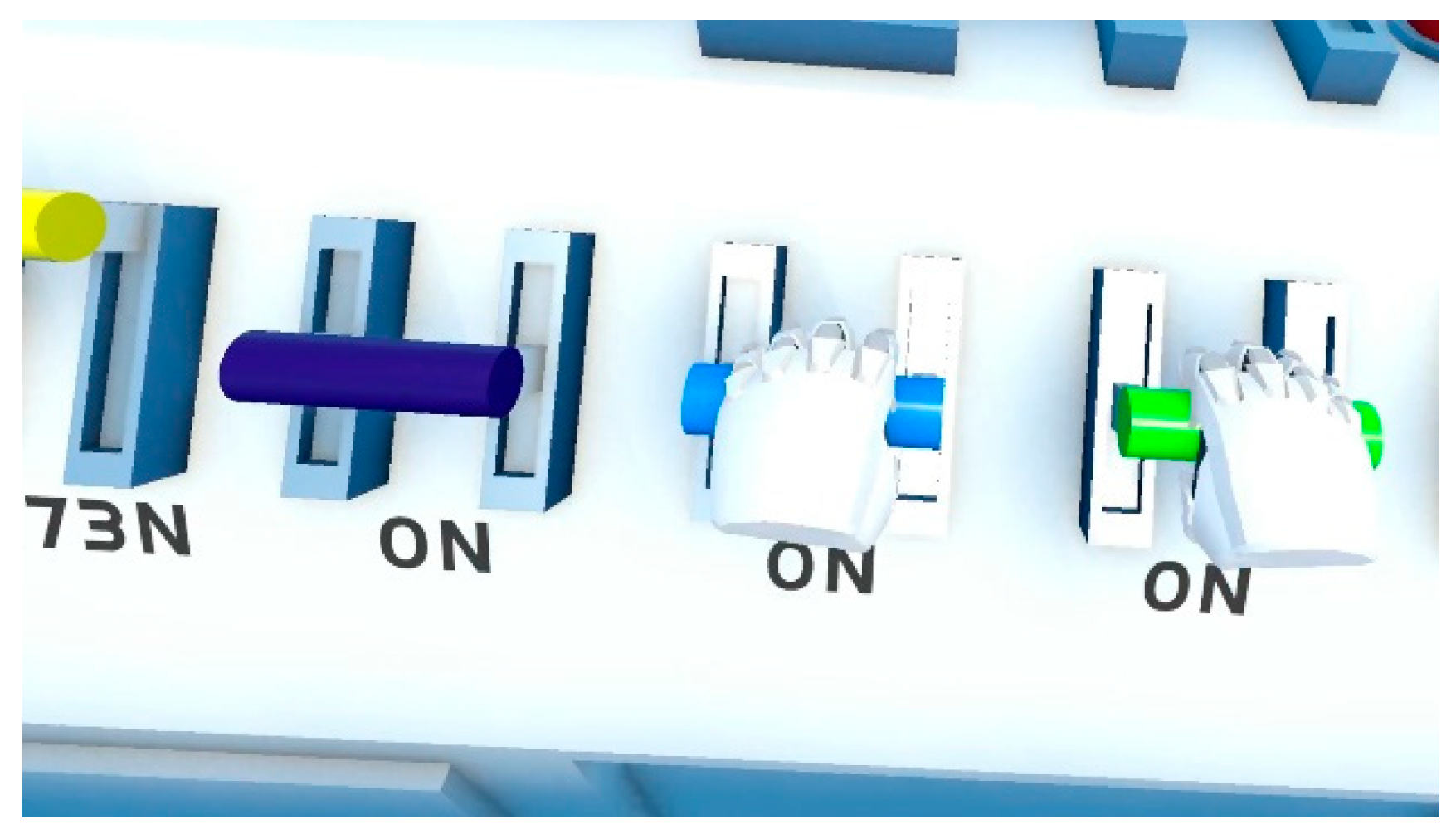

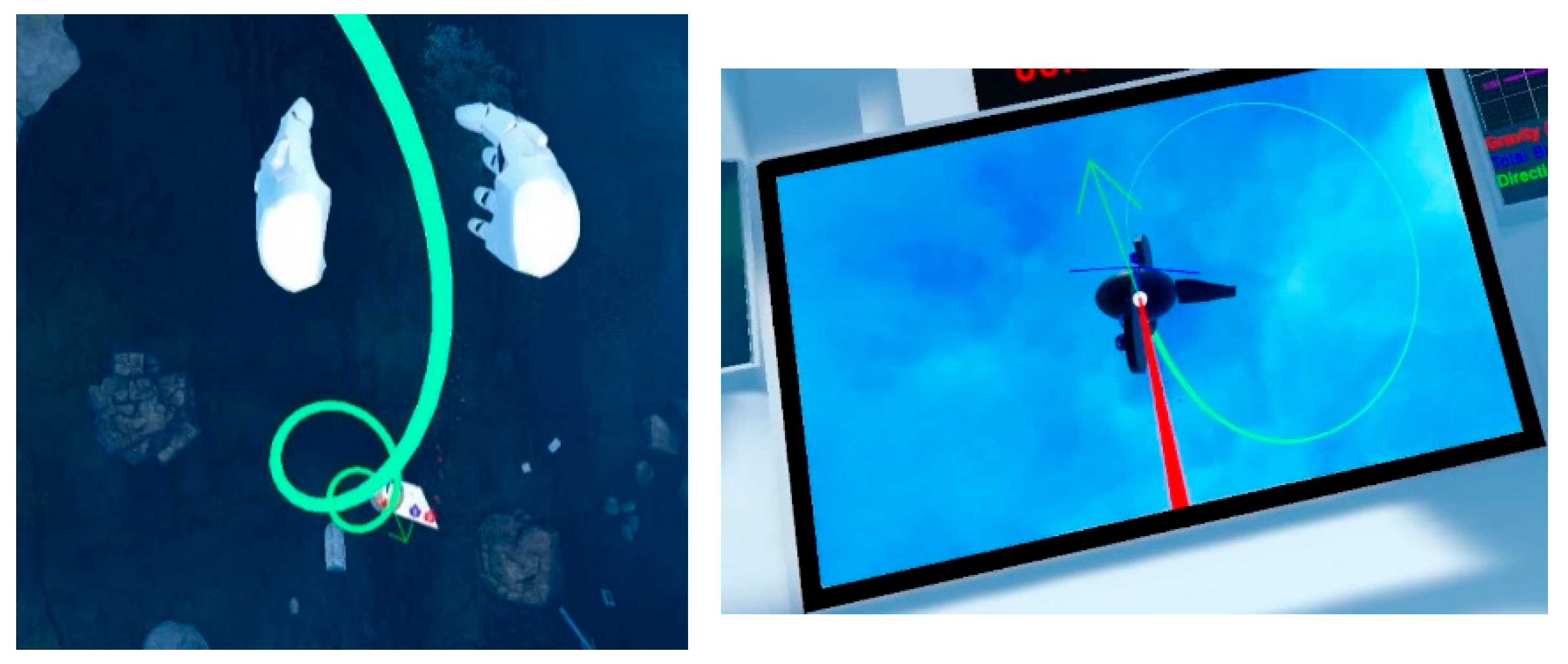

This study adopted a multi-phase experimental design, carefully structured to align with Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, ensuring a scaffolded progression that fosters both practical engagement and theoretical understanding. Each phase was tailored to build upon the previous one, creating a cohesive framework that supports iterative learning, accommodates diverse learning styles, and captures nuanced data on participant performance and psychological states. This methodical design enhances the study’s ability to generate reliable, actionable insights into the efficacy of VR-based instruction in STEM education. All figures presented in this section are screenshots captured directly from the original Submarine Simulator VR software.

In the initial phase of the protocol, participants were gradually introduced to the virtual reality (VR) platform, with the main goal of helping them feel comfortable and confident in using it. This introductory session focused on familiarizing them with the system’s interactive features, including user-friendly navigation controls and tools for building models.

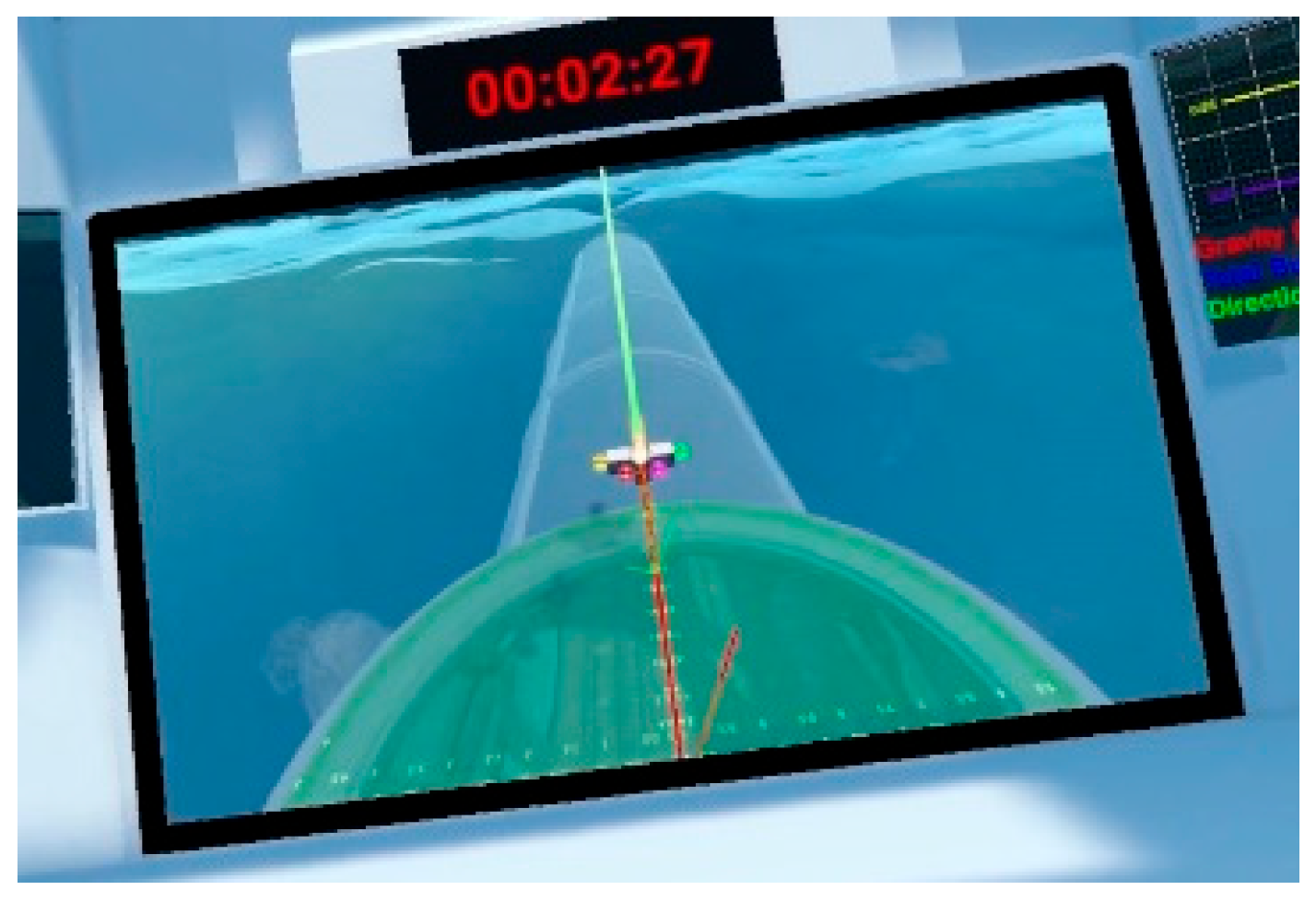

Through guided, hands-on tutorials led by a facilitator, learners actively engaged in practical exercises, learning to create submarine prototypes (

Figure 2) and conducting initial tests of navigation dynamics in the virtual underwater environment (

Figure 3).

The primary focus was on cultivating a core understanding of hydrodynamic principles, buoyancy, and propulsion mechanisms relevant to submarine design. This study does not evaluate performance metrics during this phase; instead, it functions as a preparatory stage to ensure all participants achieve a consistent baseline proficiency. Phase 1 allocated a strict 45-minute duration for each participant to complete, ensuring uniform timing across all sessions.

During phase 1, the following steps describe the instructions received (

Table 2).

Building upon the foundational skills developed in Phase 1, Phase 2 prioritizes independent design and iterative refinement within the Submarine Simulator VR environment. Participants commenced with a low-tech activity, sketching preliminary submarine designs on paper to promote conceptual planning and creative visualization unconstrained by digital tools. This approach cultivates deliberate ideation, enabling learners to freely explore concepts prior to immersing themselves in the VR platform. The underlying intention of this protocol was to examine whether VR tends to suppress creativity.

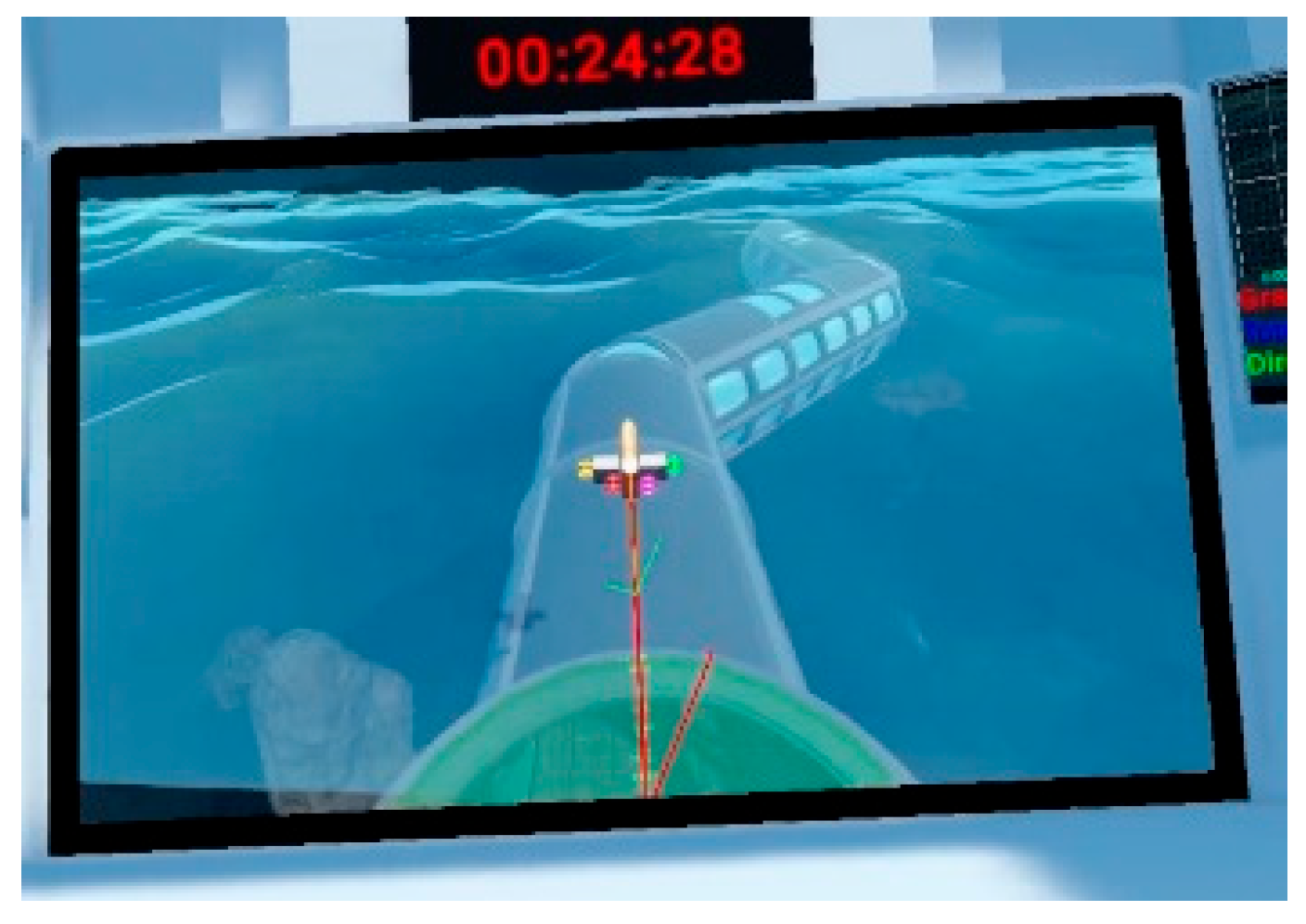

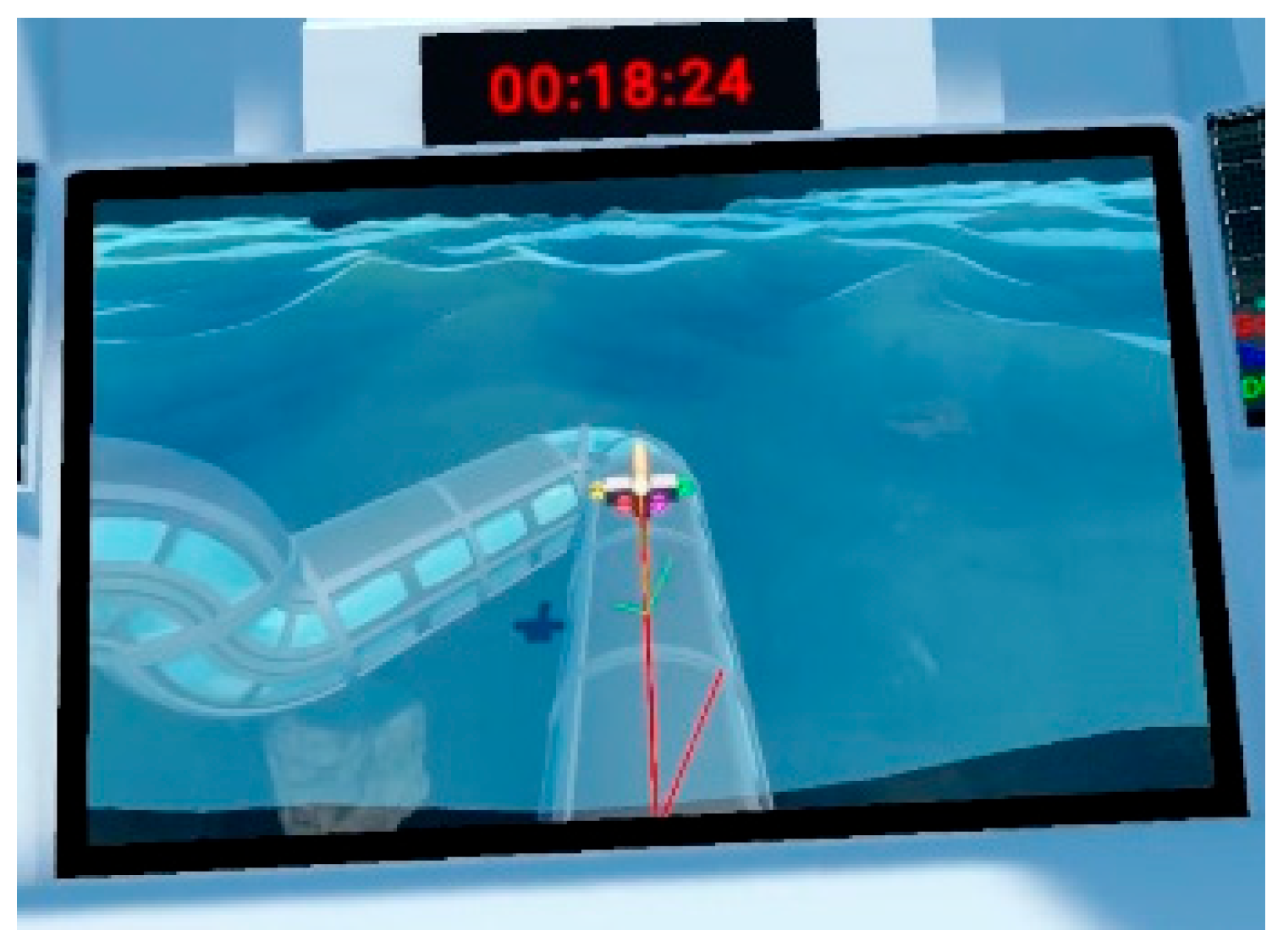

In the VR environment, the primary task during the phase involved designing submarines capable of navigating two distinct spiral trajectories in the simulated underwater setting (

Figure 4):

Tight spirals: Requiring high precision and small radius, challenging participants to optimize control and maneuverability.

Loose spirals: Emphasizing stability over larger radius, testing the model’s structural integrity under varying conditions.

Real-time feedback during testing provides data on trajectory accuracy, speed, and stability, enabling participants to refine their designs iteratively. This phase aimed to enhance problem-solving, adaptive design thinking, and practical application of hydrodynamic principles. Each participants had 35 minutes in VR during this phase.

Following Phase 2, a brief 10-minute interview was conducted to assess the students’ planning approaches for the submarine design task. Based on these interviews, participants were divided into three categories: (1) those who started with an initial plan but adapted it iteratively, based on intuition and observations (75%); (2) those who proceeded without a predefined plan, adapting dynamically along the way (20%); and (3) those who entered VR with a well-defined plan and followed it consistently throughout the phase (5%).

In the final phase of the study, a competitive twist was added by pairing participants into 13 teams, encouraging teamwork within each pair and friendly rivalry between groups. Each team collaborated to brainstorm ideas, then worked individually to design submarine models optimized for three increasingly challenging virtual underwater race tracks. These tracks were designed to reflect real-world engineering challenges, testing navigation, performance, and design skills in a dynamic, engaging and gamified way.

Track 1 - Straight-Line Navigation: Teams engineered submarine prototypes optimized for seamless straight-line propulsion, emphasizing robust propulsion mechanisms and consistent directional stability to prevent any unintended deviations from the intended path (

Figure 5).

Track 2 - Horizontal Maneuverability: This race track challenged teams to design submarine models capable of executing precise left and right maneuvers, integrating effective buoyancy adjustments, depth regulation, and thrust management to navigate the course successfully (

Figure 6).

Track 3 - Multi-Directional Agility: The most challenging track demanded complete maneuverability, requiring submarine models to execute fluid up, down, left, and right movements while maintaining precise control within a highly complex virtual underwater environment (

Figure 7).

In the concluding phase, participants put their submarine designs to the test through timed virtual simulations, where evaluations centered on key factors like whether the model fully completed the course.

Scoring was straightforward and motivating: for each track, points were allocated based on achievement—Track 1, which involved straightforward linear paths, offered 1 point if completed; Track 2 granted 2 points; and the more intricate Track 3 provided 3 points.

To heighten the excitement and competitive spirit, an additional layer was added: individuals could gain 1 bonus point by outperforming a rival in a direct race, with the opponent’s performance visualized as a "shadow" submarine (

Figure 8).

For clarity, this shadow wasn’t a live competitor, but a digital replay drawn from a prior participant’s successful run on the same track, enabling the current user to race alongside this ghostly echo in real-time within the immersive VR world, fostering a sense of head-to-head rivalry while building on collective progress.

If the current student finished the race ahead of this shadow opponent based on time, they would secure the additional point, adding a layer of competitive incentive to the exercise.

This phase emphasized interpersonal dynamics, such as competition and contentiousness, within a paired setting. Phase 3 spanned about 45 minutes, including team brainstorming, design collaboration, individual building, and racing. It is important to note that students could attempt the same track until successful or could change the track.

To conclude, the research design included three evaluation phases, each with its own set of instructions and a specific system for assessing the level of learning. (

Figure 9)

5. Results

This section outlines the findings from the empirical analyses, exploring the connections between learning styles, the immersive VR experience, and learning outcomes.

5.1. Path Analyses

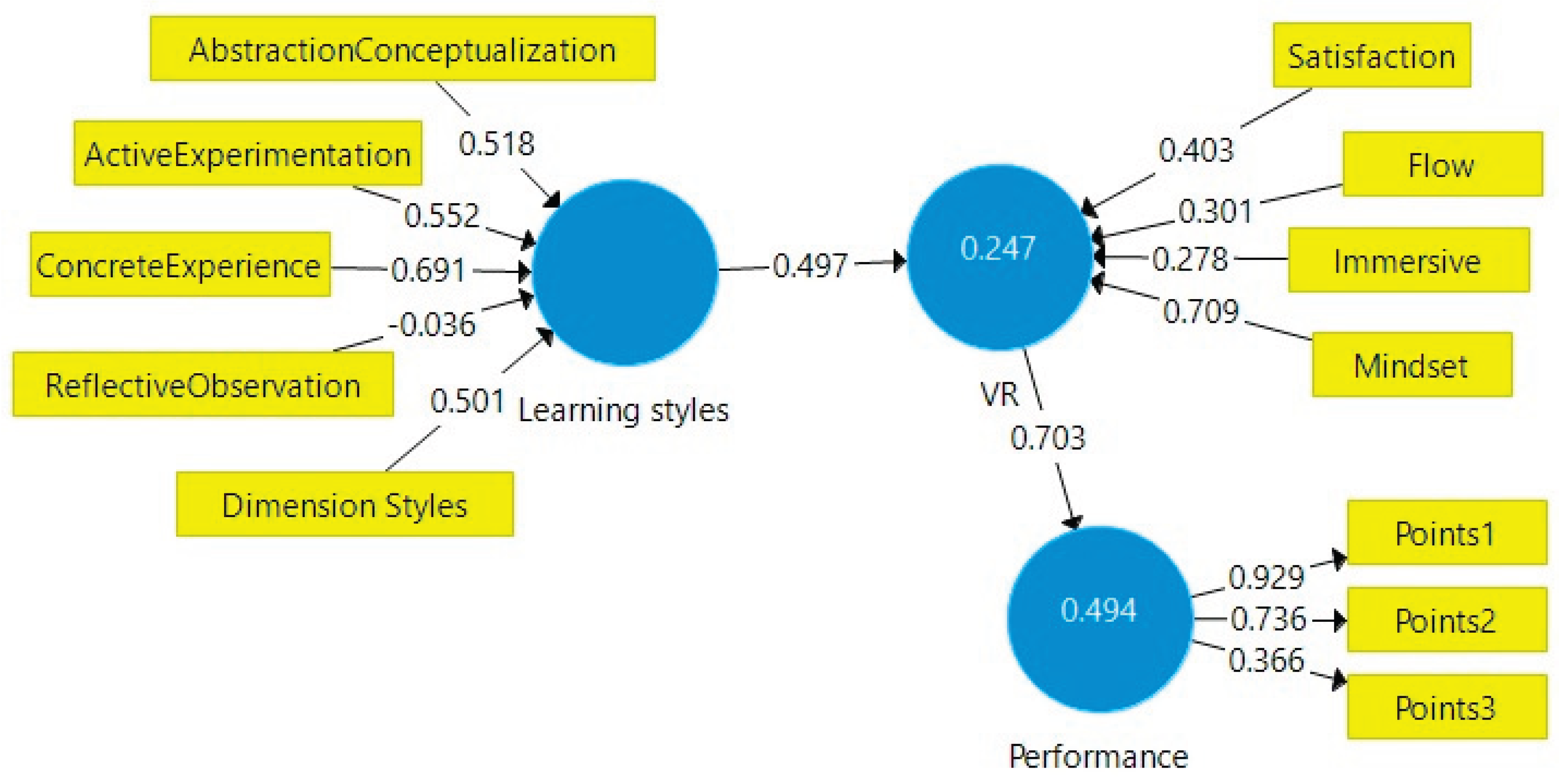

The model demonstrated good explanatory power, with R² = 0.247 for the VR latent variable and R² = 0.494 for Performance, indicating moderate to substantial effect sizes (

Figure 10).

The path coefficient from Learning Styles to VR was statistically meaningful (β = 0.497), suggesting that individual cognitive preferences (especially Active Experimentation and Concrete Experience, with loadings of 0.552 and 0.691, respectively) strongly influence the degree of VR engagement. Additionally, the path from VR to Performance was strong (β = 0.703), indicating that perceived experiential quality within the VR environment is a critical determinant of learner success (

Figure 10). H1 is confirmed.

The direct effect of Learning Styles on Performance was comparatively weaker (β = 0.290), but still statistically relevant, indicating that learning preferences have an independent albeit smaller impact on outcomes. However, the indirect effect—estimated as the product of the Learning Styles → VR and VR → Performance paths (0.497 × 0.703 ≈ 0.349)—was stronger than the direct path, supporting a partial mediation model (

Figure 10). H2 is partially confirmed, meaning that there are also additional factors that influence student’s performance.

These findings align with recent research emphasizing the role of immersive engagement (Flow and Presence) in VR-based learning (Hassan et al., 2020; Rutrecht et al., 2021). The observed mediation effect supports the hypothesis that adaptive instructional design in VR should not merely align with learner preferences, but should also optimize experiential features that facilitate cognitive absorption and sustained motivation.

5.2. Covariance Analysis of Latent Constructs

The covariance matrix for the latent variables provides additional insight into the structural relationships within the model. As shown in

Table 3, the strongest covariance emerged between the VR experience construct and Performance (Cov = 0.703), indicating a substantial shared variance between learners’ immersive engagement (Flow, Immersion, and Mindset) and their performance outcomes across the VR learning phases, confirming H3.

A moderate covariance was observed between Learning Styles and VR (Cov = 0.497), suggesting that individual cognitive preferences are meaningfully aligned with how learners perceive and engage with the VR environment. In contrast, the Learning Styles–Performance covariance was weaker (Cov = 0.290), reinforcing the interpretation that learning styles alone are not sufficient predictors of learning performance in immersive environments. The H4 hypothesis is partially confirmed, meaning that students have been able to adapt to the VR environment despite any learning style preference.

These results align with prior work highlighting the mediating role of engagement and flow in technology-enhanced learning [

11,

25] and suggest that instructional designers should prioritize experiential elements that activate learner motivation and presence over static alignment with predefined learning style categories.

The model’s explanatory power was assessed using R² and f² values for the endogenous constructs. The results indicated that the VR latent construct (comprising Flow, Immersion, and Mindset) was explained by Learning Styles with an R² value of 0.247, suggesting that approximately 24.7% of the variance in VR experience could be attributed to individual learning preferences. So, H4 was partially confirmed and the relation between learning styles, flow and immersion, but also satisfaction, needs more studies in this direction.

In turn, Performance (aggregated across three instructional phases) showed a higher R² of 0.494, meaning nearly half of the variance in student outcomes was accounted for by the model’s predictors—primarily the VR construct (

Table 4).

Effect size estimates using Cohen’s f² revealed that Learning Styles had a moderate effect on VR (f² = 0.329), while VR had a very large effect on Performance (f² = 0.977), far exceeding the threshold for a large effect. [

36] These findings reinforce the mediating role of the VR experience, suggesting that its quality is a far stronger predictor of learning outcomes than learning styles alone. H5 is confirmed. The high f² for VR on Performance underscores the central importance of immersive and engaging instructional design in achieving measurable academic gains in VR-based learning environments (

Table 4).

5.3. Construct Reliability and Validity

To assess the internal consistency and convergent validity of the latent variables, multiple reliability indices were examined, including Cronbach’s alpha, rho_A, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE). The Learning Styles and VR constructs exhibited excellent internal consistency, each achieving perfect reliability across all indices (Cronbach’s α = 1.000, rho_A = 1.000, and composite reliability = 1.000). This reflects high inter-item correlation among the indicators used for these latent variables (

Table 5).

The Performance construct showed acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.741 and composite reliability of 0.738, both exceeding the standard minimum threshold of 0.70. [

37] Furthermore, its AVE value of 0.513 surpassed the 0.50 benchmark, confirming adequate convergent validity—indicating that more than half of the variance in observed indicators was captured by the construct. Collectively, these metrics support the robustness and psychometric adequacy of the measurement model (

Table 5).

5.4. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity among the latent constructs was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which compares the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct with its correlations with other constructs. As shown in

Table 6, the square root of the AVE for Performance was 0.716, which exceeded its correlations with Learning Styles (r = 0.290) and VR (r = 0.703). Similarly, the square root of the AVE for VR (0.703) was higher than its correlation with Learning Styles (r = 0.497). These results confirm that each latent variable shares more variance with its indicators than with any other construct, thereby satisfying the criterion for adequate discriminant validity. [

39] This supports the distinctiveness of the latent dimensions measured in the model, ensuring that Learning Styles, VR experience, and Performance are empirically separable constructs (

Table 6).

Multicollinearity diagnostics were assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All indicator VIF values ranged between 1.017 and 3.036, which are well below the conservative threshold of 3.3 [

39]. This confirms that multicollinearity is not a concern in the measurement model.

The highest VIF was observed for Active Experimentation (3.036), yet it remained within acceptable limits. These results affirm the stability of the model estimation process and the robustness of path coefficient calculations (

Table 7).

5.5. Model Fit

The overall model fit was evaluated using several common indices within the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) framework. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.096 for the saturated model and 0.097 for the estimated model—both values falling below the conservative threshold of 0.10, indicating an acceptable model fit [

37].

The discrepancy measures d_ULS (0.724–0.730) and d_G (0.449–0.454) were low, further supporting the structural integrity of the model. The Chi-square values (44.431 and 44.725) provide additional support for a moderate-to-adequate fit, although chi-square statistics in PLS-SEM are typically interpreted with caution due to distributional assumptions [

40] (

Table 8).

5.6. Bootstrapping Path Coefficients

The significance of the structural model paths was assessed using a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 subsamples. The path from Learning Styles to VR experience was statistically significant, with a standardized coefficient of β = 0.497, t(df) = 2.723, p = .007. [

39] This indicates that learners’ cognitive preferences (e.g., Concrete Experience, Active Experimentation) positively and significantly influence their perceived engagement and flow within the VR environment. The strength of this relationship underscores the importance of tailoring immersive environments to accommodate cognitive variability (

Table 9).

In turn, the path from VR experience to Performance was also strong, with a standardized coefficient of β = 0.703, suggesting a substantial impact of experiential quality on learning outcomes. While no p-value is listed in the table for this path, the high coefficient aligns with previous model outputs (e.g., R² = 0.494 for Performance), reinforcing the mediating role of VR in translating cognitive predispositions into successful performance. These results lend empirical support to the conceptual model in which VR acts as a critical conduit through which learning styles exert their effect on performance (

Table 9).

6. Disscusions

A central finding of this study is the strong mediating role of the VR experience, encompassing flow, immersion, and satisfaction, between learning styles and performance. This shows that while learning preferences influence how students engage with the virtual environment, the quality of the immersive experience itself is the more potent predictor of success. The actual experience acts as a strong mediator because it leverages multisensory and interactive elements that can adapt to various learning styles, creating a unified engagement pathway that transcends individual preferences and directly enhances cognitive processing and retention.

By inducing states of flow and immersion, the learning environment minimizes distractions and boosts intrinsic motivation, allowing all learning styles to yield learning performance through emotional satisfaction and sustained focus. Ultimately, while learning styles shape initial engagement, the immersive VR experience’s ability to deliver universal psychological benefits, such as heightened focus and motivation, establishes it as the primary driver of learning outcomes.

It is possible that a well-designed VR environment acts as a cognitive ’levelling field,’ providing multiple, simultaneous pathways for understanding (kinesthetic, visual, and analytical) that cater to a wide range of learners. In such an environment, the user’s ability to achieve a state of flow may override their initial cognitive predispositions, becoming the primary driver of learning outcomes.

So, the results support the proposed mediation effect: flow and immersive presence partially bridge the relationship between learning styles and performance outcomes. This aligns with prior work on VR personalization and supports the notion that cognitive adaptation—both by learners and systems—enhances digital learning outcomes [

17].

Our results indicate that VR can effectively support experiential learning, confirming the literature data [

19,

20]. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of VR hinges greatly on its ability to facilitate the full cyclical learning process. Experiential learning does not involve confining the learner to their main learning style throughout the entire experience; instead, it entails granting entry into the learning cycle via their preferred style and guiding them through the complete cycle, thereby fostering growth in both their flexible styles and emerging styles.

In engineering education research, the Assimilating and Converging styles, referred to as Analyzing and Deciding in Kolb’s latest framework used in this paper, demonstrate greater task effectiveness in model-building simulations. In contrast, the Accommodating style, termed Initiating in the same framework, shows a negative correlation with non-personalized descriptive tasks, indicating underperformance in non-hands-on phases unless adapted [

21]. Our study’s findings suggest that while learning styles play a role, other factors more strongly influence performance, as evidenced by a weaker correlation with learning styles alone.

The results from another study indicate that learners derive the greatest benefits from the VR guided exploration mode, regardless of their individual learning styles, highlighting the potential of VR-based environments to effectively accommodate diverse learning preferences [

9]. This finding resonates with our own research process, as it partially confirms Hypothesis 2, demonstrating that all students, irrespective of their learning style, were able to adapt and perform successfully to some extent across all three phases of our study.

Interestingly, learners identified as “balanced” (with near-zero AERO and ACCE scores) maintained consistent flow across all task types, reinforcing the value of flexibility in learning approaches, which is crucial for student development as it enables them to adapt to circumstances by flexing into all learning styles. This group’s performance suggests that versatile cognitive strategies can help navigate the diverse demands of VR environments.

7. Conclusions

Learning environments built in virtual reality, like the Submarine Simulator, are powerful tools for nurturing these developing styles. By engaging students in immersive tasks—such as designing and testing submarine models, VR encourages experimentation, reflection, and refinement, helping learners strengthen unfamiliar learning styles. However, achieving full-cycle learning, where students adeptly navigate all stages, relies on a supportive learning environment. A well-crafted VR platform, combined with guided instruction and reflective opportunities, creates an ideal setting to enhance engagement and foster growth across all learning styles, enabling students to become versatile, well-rounded learners.

Adaptive instructional design, grounded in theoretical frameworks like Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, is essential to create inclusive and effective VR-based learning environments by tailoring content and interactions to accommodate diverse learner preferences, such as reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, concrete experience, and active experimentation. This approach not only enhances individual learner engagement and retention but also addresses potential disparities in cognitive load, ensuring that VR tools are accessible and beneficial across a wide range of educational contexts, from technical training to creative skill development.

Moreover, the modality effect highlights the importance of thoughtfully designing how information is presented in VR, as it can variably affect cognitive load. Although VR provides notable benefits for improving cognitive functions, it is critical to address potential issues like cognitive overload and prioritize effective instructional design to optimize learning results.

By creating feedback loops between students, educators, and developers, we can cultivate an ecosystem that continuously evolves, ensuring that VR tools remain relevant and impactful in addressing the complexities of modern education. In addition to the importance of user feedback, it is crucial to explore the role of interdisciplinary collaboration in enhancing VR learning environments.

Our findings translate into actionable guidance for instructional designers. To better support learners with a preference for reflective observation (negative AERO scores), VR platforms should include features that allow for replaying and analyzing their performance from multiple perspectives. Conversely, for learners with a high preference for abstract conceptualization (positive ACCE scores), embedding access to theoretical principles and real-time data visualizations directly within the VR environment could be crucial for bridging the gap between theory and application.

Thus, continued research and innovative practices are essential to fully harness the transformative power of VR in education, enabling the development of tailored learning experiences that cater to diverse student needs and learning styles. This ongoing exploration should focus on refining VR technologies and pedagogical strategies to maximize engagement, enhance skill acquisition, and foster critical thinking, thereby preparing students for a future where technology is an integral and dynamic component of their learning journeys across various disciplines and contexts.

7.1. Limitations

This holistic approach, which includes comprehensive teacher training and the incorporation of user feedback, will be vital in maximizing the potential of VR technologies in fostering inclusive and engaging learning environments. The study involved a single group of students enrolled in the underwater engineering course and was relatively homogeneous, which may be considered a limitation as it could restrict the generalizability of the findings across more diverse populations. A notable limitation is that the experiment was heavily dependent on a facilitator to guide participants. While this ensured a baseline proficiency, it also suggests that complex, open-ended educational VR tools like the Submarine Simulator may not yet be suitable for fully independent learning. This can be viewed as an interesting finding for practical implementation: the role of the educator evolves from a knowledge dispenser to a ’VR facilitator,’ who is very important for scaffolding the experience, managing cognitive load, and ensuring pedagogical goals are met.

The time interval between phases was strictly capped at a maximum of 7 days, allowing for some degree of individual variation among students, though additional constraints could potentially be applied in future studies to refine this aspect.

Future research should investigate the incorporation of real-time monitoring, including metrics like Heart-Rate Variability, Heart Rare and other physiological sensors, to dynamically adapt and personalize VR experiences based on learners’ immediate states. Gaining a deeper understanding of this intricate interplay between physiological responses and virtual learning environments will be crucial, particularly in engineering education, where optimizing performance and sustaining high levels of engagement are paramount for success. Thus, continued research and innovative practices are necessary to fully harness the transformative power of VR in education, preparing students for a future where technology plays an integral role in their learning journeys.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, ABS, ST and RVR.; methodology, ABS, ST and RVR; software, ABS.; validation, ABS, ST, RVR and RBMT.; formal analysis, ABS, ST, RVR and RBMT.; investigation, ABS.; data curation, ABS, ST and RVR.; writing—original draft preparation, ABS, ST, RVR and RBMT.; writing—review and editing, ABS, ST, RVR and RBMT; visualization, ABS, ST, RVR and RBMT; supervision, ST and RVR. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Acknowledgments

The research was run within doctoral studies and supervised by the coordinators from MINES Paris - PSL and National University of Science and Technology “POLITEHNICA” Bucharest. The main author (ABS) is an Experiential Learning Practitioner and Facilitator, certified by the Institute for Experiential Learning. Certification IDs: 1a500d6d-db52-4f46-ac23-6a8abe4cc321 and 0f037352-d1f4-4cfc-81e9-1110742f0c2c.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1

The Kolb Experiential Learning Profile (KELP) is based on the experiential theory and model of learning developed by David Kolb (1984) and on the seminal contributions of John Dewey, Kurt Lewin & Jean Piaget. Based on the results of the test, students have received a scored on the following four quadrants, describing how they process and transform experiences into knowledge:

- (1)

Concrete Experience (CE) - Learners immerse themselves fully, openly, and without preconceived biases in novel experiences, emphasizing direct involvement and sensory engagement.

- (2)

Reflective Observation (RO) - They contemplate and examine these experiences from diverse viewpoints, fostering introspection and nuanced understanding.

- (3)

Abstract Conceptualisation (AC) - They synthesize observations into coherent concepts, forming logically robust theories that explain patterns and relationships.

- (4)

Active Experimentation (AE) - They apply these theories practically to inform decision-making and address real-world problems, testing ideas through action.

Drawing from these four quadrants, Kolb’s refined framework identifies nine distinct learning styles, each offering greater granularity and reflecting preferences in how individuals navigate the learning cycle:

Experiencing: Thrives on hands-on engagement, relying on intuition and emotional connection to immerse fully in new experiences.

Imagining: Combines creativity and reflection, brainstorming innovative ideas by exploring diverse perspectives with empathy.

Reflecting: Focuses on deep observation, analyzing experiences from multiple angles to uncover patterns and insights.

Analyzing: Excels at systematic analysis, organizing observations into structured, logical frameworks.

Thinking: Prioritizes logical reasoning, developing precise, theory-driven solutions through objective analysis.

Deciding: Focuses on practical problem-solving, using theories to make informed decisions and achieve measurable outcomes.

Acting: Thrives in dynamic settings, implementing ideas and adapting quickly to achieve tangible results.

Initiating: Proactively embraces new challenges, combining risk-taking with enthusiasm to explore innovative solutions.

Balancing: Adapts flexibly across all learning cycle stages, seamlessly integrating experiencing, reflecting, theorizing, and acting.

These dimensions capture how people balance opposing approaches to perceiving (grasping information) and processing (transforming information):

ACCE (Abstract Conceptualization minus Concrete Experience): This represents the "perceiving" dimension, measuring an individual’s preference for abstract thinking versus concrete feeling when grasping new information. A positive ACCE score indicates a stronger inclination toward AC—favoring logical analysis, theoretical models, and objective reasoning (e.g. conceptualizing principles like buoyancy in a submarine simulation). A negative score leans toward CE, emphasizing tangible, hands-on experiences and intuitive, relational approaches (e.g., immersing in sensory feedback from the VR environment). This dimension highlights how learners prefer to initially encounter and internalize experiences, with balanced scores suggesting flexibility between the two.

AERO (Active Experimentation minus Reflective Observation): This is the "processing" dimension, assessing the preference for active doing versus reflective watching when transforming experiences into knowledge. A positive AERO score points to a bias toward AE—prioritizing practical application, experimentation, and risk-taking to test ideas (e.g., iteratively redesigning a submarine model and running tests). A negative score favors RO, focusing on careful observation, contemplation, and diverse viewpoints before acting (e.g., reviewing simulation outcomes to understand failures). Like ACCE, this dimension underscores processing strategies, and neutral scores indicate adaptability.

Appendix 2

Descriptive Statistics of Learning Styles and Dimensions Within Target Group

Below are the key descriptive statistics for the core Kolb dimensions (CE, RO, AC, AE) and their differences (ACCE, AERO). (Table 2.1) These provide an overview of central tendencies and variability. The group shows a clear preference for Abstract Conceptualization (higher mean AC vs. CE, positive ACCE), aligning with analytical and logical thinking in Kolb’s model. The near-zero mean AERO indicates balance between reflection and action overall, with moderate variability suggesting individual differences. (Table 2.1.)

Table 2.1.

Learning styles of the target group members.

Table 2.1.

Learning styles of the target group members.

| Dimension |

Mean |

Std Dev |

Min |

25% |

Median |

75% |

Max |

| CE (Concrete Experience) |

20.0 |

6.7 |

11 |

16.0 |

17.0 |

22.0 |

37 |

| RO (Reflective Observation) |

26.6 |

5.5 |

16 |

22.3 |

26.5 |

29.5 |

39 |

| AC (Abstract Conceptualization) |

35.1 |

5.9 |

24 |

30.3 |

36.0 |

39.0 |

44 |

| AE (Active Experimentation) |

27.3 |

5.9 |

14 |

25.0 |

27.0 |

29.0 |

41 |

| ACCE (AC - CE) |

15.1 |

8.5 |

-9 |

11.0 |

16.5 |

20.0 |

27 |

| AERO (AE - RO) |

0.7 |

8.8 |

-15 |

-5.8 |

0.0 |

8.3 |

15 |

In table 2.2, we represent the distribution of the main learning style. Analysing dominates (38.5%), followed by Thinking, indicating a sample skewed toward assimilative (high AC/RO) and convergent (high AC/AE) styles in Kolb’s framework.

Table 2.2.

Distribution of Main Learning Styles.

Table 2.2.

Distribution of Main Learning Styles.

| Main Style |

Count |

Percentage |

| Analyzing |

10 |

38.5% |

| Thinking |

6 |

23.1% |

| Acting |

3 |

11.5% |

| Reflecting |

2 |

7.7% |

| Balancing |

2 |

7.7% |

| Initiating |

2 |

7.7% |

| Deciding |

1 |

3.8% |

The target group was also characterized through their flex learning style (in Kolb model). Flex styles were split and counted across all participants (total mentions=101, average ~3.9 per person). The counts are taken from the analysis: Balancing (20), Reflecting (19), Thinking (13), Analyzing (11), Imagining (11), Deciding (10), Experiencing (7), Acting (7), Initiating (3), totaling 101 mentions across 26 participants (average ~3.9 flexes per person). (Table 2.3)

Table 2.3.

Distribution of flex (secondary) learning style.

Table 2.3.

Distribution of flex (secondary) learning style.

| Flex |

Count |

Percentage of Total Mentions |

| Balancing |

20 |

19.8% |

| Reflecting |

19 |

18.8% |

| Thinking |

13 |

12.9% |

| Analyzing |

11 |

10.9% |

| Imagining |

11 |

10.9% |

| Deciding |

10 |

9.9% |

| Experiencing |

7 |

6.9% |

| Acting |

7 |

6.9% |

Balancing and Reflecting are most common, appearing in 77% and 73% of profiles, respectively. 84.6% (22/26) of participants include "Balancing" in main style or flexes. High prevalence of Balancing implies versatility, allowing adaptation across Kolb’s cycle (experiencing, reflecting, thinking, acting). This could indicate a mature or trained group, as Kolb emphasizes balanced styles for effective learning.

The results obtained by the participants to the other tests are presented below. (Table 2.4.)

Table 2.4.

Performance scores and questionnaire results for each participant.

Table 2.4.

Performance scores and questionnaire results for each participant.

| UserID |

Main Learning Style |

Flow Result (FSS) |

Immersive Result (IQT) |

BANG Result (Satisfaction) |

Learning Outcome Phase 1 |

Learning Outcome Phase 2 |

Learning Outcome Phase 3 |

| 290 |

Thinking |

3.778 |

4.071 |

15 |

20 |

2 |

12 |

| 709 |

Acting |

4.028 |

3.429 |

17 |

19 |

2 |

11 |

| 227 |

Analyzing |

4.528 |

4.286 |

14.5 |

20 |

2 |

10 |

| 512 |

Initiating |

4.222 |

3.857 |

17 |

19 |

2 |

8 |

| 177 |

Balancing |

4.389 |

3.893 |

16 |

17 |

2 |

4 |

| 443 |

Balancing |

4.194 |

3.929 |

18.5 |

18 |

2 |

3 |

| 187 |

Initiating |

3.972 |

4.214 |

15.5 |

17 |

2 |

2 |

| 159 |

Thinking |

4.333 |

4.179 |

12 |

17 |

2 |

2 |

| 830 |

Analyzing |

4.194 |

3.571 |

17.5 |

17 |

2 |

0 |

| 670 |

Thinking |

3.778 |

4.464 |

17.5 |

20 |

2 |

0 |

| 590 |

Analyzing |

3.556 |

4.071 |

17.5 |

18 |

2 |

0 |

| 595 |

Analyzing |

3.361 |

4.036 |

16 |

19 |

1 |

5 |

| 682 |

Deciding |

3.972 |

4.071 |

15.5 |

16 |

1 |

3 |

| 341 |

Reflecting |

4.361 |

4.536 |

15.5 |

19 |

1 |

2 |

| 411 |

Thinking |

3.861 |

3.893 |

15 |

18 |

1 |

2 |

| 840 |

Analyzing |

3.194 |

3.679 |

16.5 |

15 |

1 |

2 |

| 388 |

Analyzing |

3.972 |

3.857 |

16 |

18 |

1 |

1 |

| 723 |

Analyzing |

4.111 |

4.143 |

14.5 |

17 |

1 |

0 |

| 985 |

Reflecting |

2.528 |

3.786 |

18.5 |

17 |

1 |

0 |

| 779 |

Thinking |

3.361 |

4.179 |

20 |

18 |

1 |

0 |

| 298 |

Acting |

3.333 |

4.286 |

13 |

18 |

1 |

0 |

| 484 |

Acting |

4.528 |

3.679 |

16.5 |

16 |

1 |

0 |

| 770 |

Analyzing |

3.222 |

4.036 |

15.5 |

16 |

1 |

0 |

| 955 |

Thinking |

3.722 |

4.179 |

15.5 |

15 |

1 |

0 |

| 642 |

Analyzing |

2.500 |

3.750 |

13 |

14 |

1 |

0 |

| 256 |

Analyzing |

3.778 |

3.500 |

17 |

15 |

0 |

4 |

References

- Wong, J.Y.; Azam, A.B.; Cao, Q.; Huang, L.; Xie, Y.; Winkler, I.; Cai, Y. Evaluations of Virtual and Augmented Reality Technology-Enhanced Learning for Higher Education. Electronics 2024, 13, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, J.; Martínez, A.; Mula, F.; Contero, M. Learning by Doing in VR: A User-Centric Evaluation of Lathe Operation Training. Electronics 2024, 13, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, A.K. Ab. Aziz, N.A.; Ab. Aziz, K.; Tse Kian, N. The usage of virtual reality in engineering education. Cogent Education 2024, 11, 2319441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, F.; Alomar, M.A.; Alotaibi, F.M.; Serbaya, S.H.; Rizwan, A.; Hasan, F. Leveraging Virtual Reality in Engineering Education to Optimize Manufacturing Sustainability in Industry 4.0. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyed, F.A.S.; Tehseen, M.; Tariq, S.; Muhammad, A.K.; Yazeed, Y.G.; Habib, H. Integrating educational theories with virtual reality: Enhancing engineering education and VR laboratories. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 2024, 10, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.L.; Luo, Y.F.; Yang, S.C.; Lu, C.M.; Chen, A.S. Influence of Students’ Learning Style, Sense of Presence, and Cognitive Load on Learning Outcomes in an Immersive Virtual Reality Learning Environment. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2019, 58, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptman, H.; Cohen, A. The synergetic effect of learning styles on the interaction between virtual environments and the enhancement of spatial thinking. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 2106–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Ho, J.; Kuo, T.; Luong, T.H. Behavioral Intention of Using Virtual Reality in Learning. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion; 2017; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Seong, C.T.; Wan, M.F.; Wan, I. Are Learning Styles Relevant to Virtual Reality? Journal of Research on Technology in Education 2005, 38, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedram, S.; Howard, S.; Kencevski, K.; Perez, P. Investigating the Relationship Between Students’ Preferred Learning Style on Their Learning Experience in Virtual Reality (VR) Learning Environment. In Human Interaction and Emerging Technologies. IHIET 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Ahram, T., Taiar, R., Colson, S., Choplin, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.; Jylhä, H.; Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Flow in VR: A Study on the Relationships Between Preconditions, Experience and Continued Use. In Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Tamez, C.R. The Impact of Immersion through Virtual Reality in the Learning Experiences of Art and Design Students: The Mediating Effect of the Flow Experience. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolis, C.; Burns, D.J.; Assudani, R.; Chinta, R. Assessing experiential learning styles: A methodological reconstruction and validation of the Kolb Learning Style Inventory. Learning and Individual Differences 2013, 23, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, L.; Ally, M. Considering Learning Styles When Designing for Emerging Learning Technologies. In Emerging Technologies and Pedagogies in the Curriculum. Bridging Human and Machine: Future Education with Intelligence; Yu, S., Ally, M., Tsinakos, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, G.M. Learning Styles: Lack of Research-Based Evidence. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 2023, 96, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, U.; Slam, S.; Choo, Y.H.; Alamoush, A.; Al Qallab, K. Automatic prediction of learning styles: a comprehensive analysis of classification models. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics (BEEI) 2024, 13, 7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampling, H. The Role of Immersive Virtual Reality in Individual Learning. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Lin, H.-C. K.; Wang, T.H. Integrating the STEAM-6E Model with Virtual Reality Instruction: The Contribution to Motivation, Effectiveness, Satisfaction, and Creativity of Learners with Diverse Cognitive Styles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konak, A.; Clark, T.K.; Nasereddin, M. Using Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle to improve student learning in virtual computer laboratories. Comput. Educ. 2014, 72, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majgaard, G.; Weitze, C. Virtual Experiential Learning, Learning Design and Interaction in Extended Reality Simulations. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Games Based Learning ECGBL 2020, 24–25 September 2020, a Virtual Conference Supported by the University of Brighton; Academic Conferences and Publishing International; pp. 372–379. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344412172_Virtual_Experiential_Learning_Learning_Design_and_Interaction_in_Extended_Reality_Simulations (accessed on 5 march 2025).

- Horváth, I. An Analysis of Personalized Learning Opportunities in 3D VR. Front. Comput. Sci., 2021, 3, 673826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharias, P.; Andreou, I.; Vosinakis, S. Educational Virtual Worlds, Learning Styles and Learning Effectiveness: an empirical investigation. 2010. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:14092908.

- Rutrecht, H.; Wittmann, M.; Khoshnoud, S.; Igarzábal, F.A. Time Speeds Up During Flow States: A Study in Virtual Reality with the Video Game Thumper. Timing & Time Perception 2021, 9, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mütterlein, J. The Three Pillars of Virtual Reality? Investigating the Roles of Immersion, Presence, and Interactivity. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2018. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/50061.

- Mulders, M. Experiencing flow in virtual reality: an investigation of complex interaction structures of learning-related variables. IADIS International Conference Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Li, Y. Impact of Spatial Environment Design on Cognitive Load. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality Workshops (VRW); 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Shunbo, W.; Yangfan, L. The study of virtual reality adaptive learning method based on learning style model. Computer Applications in Engineering Education 2021, 30, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilova, T.; Zhigalova, O.P.; Baranova, V.A. The Success of the Educational Task for Visual-Motor Coordination among Virtual Reality: Cognitive-Personal Factors. Perspektivy nauki i obrazovania - Perspect. Sci. Educ. 2023, 61, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, D.; Harvey, M.; Deligianni, F. Predictive Modelling of Cognitive Workload in VR: An Eye-Tracking Approach. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, S. The Study and Application of Adaptive Learning Method Based on Virtual Reality for Engineering Education. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1015, pp. 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; He, M.; Wang, H. Effects of Attention Level and Learning Style Based on Electroencephalo-Graph Analysis for Learning Behavior in Immersive Virtual Reality. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 53429–53438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. The Kolb Experiential Learning Profile A Guide to Experiential Learning Theory, KELP Psychometrics and Research on Validity. The Kolb Experiential Learning Profile (KELP) Tech Guide. 2021. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/87570273/The_Kolb_Experiential_Learning_Profile_A_Guide_to_Experiential_Learning_Theory_KELP_Psychometrics_and_Research_on_Validity.

- Jackson, S.A.; Marsh, H. Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 1996, 18, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witmer, B.G.; Singer, M.J. Measuring Presence in Virtual Environments: A Presence Questionnaire. Presence 1998, 7, 225–240. Available online: https://cs.uky.edu/~sgware/reading/papers/witmer1998measuring.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ballou, N.; Denisova, A.; Ryan, R.; Scott Rigby, C.; Deterding, S. The Basic Needs in Games Scale (BANGS): A new tool for investigating positive and negative video game experiences. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2024, 188, 103289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3 Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH: Boenningstedt 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modelling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laar, S.; Braeken, J. Caught off Base: A Note on the Interpretation of Incremental Fit Indices. Struct. Equ. Model. 2022, 29, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).