Background

Cultural and Religious Influences on Elder Care Practices

Culture refers to the shared values, norms, and traditions that influence caregiving expectations (Eagleton, 2016). Religion is a system of beliefs, practices, and moral values centered on the worship of a higher power or divine being, and it provides a framework for understanding caregiving experiences (Jensen, 2019). Christianity, as both a religious and cultural system, shapes caregiving through biblical teachings and religious obligations (Gunn et al., 2019). This religious-cultural convergence aligns with cultural expectations (Ezulike et al., 2024; Zarzycki et al., 2023) and religious beliefs (Hinton et al., 2008; Kristanti et al., 2019; Zahed et al., 2019), framing caregiving as both a religious duty and a societal expectation.

Confucian filial piety mandates elder care as both an ethical and quasi-religious obligation (Canda, 2013; Fan, 2007). While Christianity also emphasizes respect for parents, its principles frame caregiving as an expression of love, service, and obedience to God rather than a hierarchical duty (Esiaka & Luth, 2023; Ziettlow & Cahn, 2015). Despite modernization, filial piety continues to shape elder care practices (Chadwin, 2023; Li et al., 2010; Nguyen, 2023; Theixos, 2013). Similarly, among Nigerian Christians, caregiving is guided by biblical teachings, particularly the command to "Honor your father and mother," (Biblica, 2011) which reinforces intergenerational caregiving as a divine obligation (Esiaka & Luth, 2023). This interplay between cultural and religious ideologies highlights how elder care practices extend beyond practical caregiving to reinforce broader values of respect, duty, and intergenerational continuity (Andruske O'Connor, 2020; Rutagumirwa et al., 2020).

Religious teachings further integrate caregiving into moral obligations. In Christianity, caregiving is a religious act, modeled after Christ’s compassion and service (Rieg et al., 2018). Islam, by contrast, frames elder care as both a family duty and a religious responsibility, guided by Quranic and Hadith principles (Ahmad Ramli et al., 2021). While both view caregiving as an obligation, Christianity emphasizes service as an expression of religious devotion, whereas Islam integrates familial and communal responsibility. Among Nigerian Christians, caregiving is deeply intertwined with church communities, where religious networks provide support and reinforce caregiving responsibilities as a religious duty (Ebimgbo et al., 2018).

Caregiving traditions similarly intertwine familial obligations with religious imperatives, reinforcing intergenerational care as an expression of respect and devotion (Esiaka et al., 2020; Twum-Danso, 2009). However, caregiving expectations among Nigerian Christians are influenced by both cultural traditions and the pressures of migration, creating tensions between religious ideals and contemporary realities (Esiaka & Luth, 2023). Modernization, migration, and shifting family structures complicate culturally rooted caregiving expectations, creating tensions between cultural norms and contemporary realities (Esiaka & Luth, 2023; Nguyen, 2023). Providing financial and instrumental support to parents is a public demonstration of respect, strengthening social cohesion (Esiaka & Luth, 2023; Esiaka et al., 2020).

Religious traditions reinforce these obligations across cultures. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam emphasize elder care as both a divine and ethical duty (Halim et al., 2024; Clarfield et al., 2003). In Islam, the Quran and Hadith advocate comprehensive support for elders (Abdalla & Patel, 2010; Halim et al., 2024), while Christianity upholds the biblical command to "Honor your father and mother," extending caregiving beyond physical support to religious and emotional care (Esiaka, 2019; Ziettlow & Cahn, 2015). While religious imperatives strengthen caregiving norms, they can also create pressure, particularly where formal support systems are lacking. Failing to provide elder care carries both religious and social consequences, reinforcing its obligatory nature (Imoh, 2022; Twum-Danso, 2009).

Moral scrutiny further complicates caregiving, when societal and religious expectations clash with economic and practical constraints (Lee, 2016; Shrestha et al., 2023; Theixos, 2013; Ziettlow & Cahn, 2015). Religious beliefs serve as both a source of obligation and motivation. Many caregivers draw strength from religious teachings that emphasize compassion and duty (Kristanti et al., 2019). For Nigerian Christians, caregiving is also an extension of religious beliefs, with prayer, scripture, and church guidance playing a central role in care decisions (Esiaka & Luth, 2023). Elder care fosters harmony and preserves ancestral connections (Magesa, 2014). Unlike Hinduism, which integrates karma and reincarnation into caregiving (Hinton et al., 2008; Dewar et al., 2015), Christianity frames caregiving as a direct reflection of religious commitment and a means of fulfilling divine purpose (Gunn et al., 2019; Rieg et al., 2018). These religious and cultural influences shape caregiving across societies, sustaining intergenerational ties while adapting to evolving social landscapes.

Religious and Cultural Motivations for Caregiving

While existing studies on religious motivation and caregiving do not specifically focus on Nigerian Christian caregivers, the framework of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity offers a lens to understand how religiosity influences caregiver well-being and stress. Four types of religious motivation intrinsic (internalized religious commitment), self-determined extrinsic (personal values with external influence), non-self-determined extrinsic (external pressures), and amotivation (lack of intent) shape caregiving experiences (O'Connor & Vallerand, 1990). Intrinsic and self-determined extrinsic motivations support sustained caregiving, while non-self-determined extrinsic motivation may increase stress, and amotivation can lead to disengagement (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Intrinsic religiosity is linked to higher self-esteem and lower depression (Lavretsky, 2010; Nelson, 1990; Zimmer et al., 2016), whereas extrinsic religiosity, driven by external rewards or pressures, often correlates with anxiety and depression (Kuyel et al., 2012; Mazloomi Mahmoodabad et al., 2016). These associations vary, with some studies reporting weak correlations (Kuyel et al., 2012). For Christian caregivers, balancing religious motivation with external demands can shape their caregiving resilience, burden, and overall well-being (Fider et al., 2019). Religiosity remains a strong predictor of psychological adjustment (Salsman & Carlson, 2005), and individuals high in both intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity tend to adjust better (Milevsky & Levitt, 2004). Understanding these distinctions clarifies how religious beliefs influence caregiver resilience, burden, and well-being. Informal caregiving motivations stem from cultural and societal influences, along with personal and relational factors. Key motivators include reciprocity, altruism, moral responsibility, and the desire for peaceful longevity (Ezulike et al., 2024).

Cultural values, beliefs, and societal norms significantly shape caregiving motivations, with religion and culture serving as underlying factors (Zarzycki et al., 2022). The concept of cultural self-identity emerges as an overarching explanatory factor, influencing cultural duty, obligations, and values (Zarzycki et al., 2022). Personal and relational motivations encompass reciprocity, affection, family values, and caregiving obligations (Zarzycki et al., 2022). Reciprocity shapes caregiving in Nigeria, where support is often mutual. (Ezulike et al., 2024). This framing, positions caregiving as a cultural responsibility to older adults, who are honored as protectors of traditions, ancestral links, and spiritual mediators (Eboiyehi, 2019).

Religious and Cultural Connections in Transnational Setting

Religion and culture shape migrant caregiving practices, serving as coping mechanisms and tools for preserving identity (Machoko, 2013; Mensah et al., 2013). Migrant-specific religious organizations have emerged not only due to gaps in inclusivity within mainstream Western institutions but also from a strong desire for belonging and the preservation of national or regional religious practices, cultures, and denominations through language, music, and worship (Baffoe, 2011; Este & Tachble, 2009). These spaces foster belonging and transmit values across generations. However, in secular and diverse host societies, this reliance may prioritize cultural preservation over cross-cultural engagement (Burr et al., 2015). Religious beliefs and cultural practices influence caregiving attitudes but can create tensions when navigating differing norms (Nurunnaher et al., 2023; Regan, 2016). These dynamics illustrate the complex role of religion and culture in both facilitating resilience and creating friction for migrant caregivers.

The transmission of religiosity across generations refers to the ways in which religious beliefs, practices, and values are passed from parents to children through shared worship, moral instruction, and everyday caregiving routines. This process has been linked to stronger eldercare norms and familistic values, particularly during emerging adulthood (Bengtson et al., 2009; Silverstein et al., 2023). For migrant families, the intergenerational transmission of religiosity may be intensified after migration, as religious participation becomes a key strategy for coping with past traumas and navigating the challenges of resettlement and cultural adjustment (Hurly, 2019; Levitt, 2003). Religious spaces offer migrants a sense of belonging and address unique concerns that mainstream social or cultural groups may overlook, reinforcing the essential role of religion in community building and emotional well-being (Machoko, 2013; Kgomo, 1986; Stewart et al., 2015). Religion often functions as a means of maintaining transnational ties, providing migrants with emotional and social support during the process of migration and integration (Machoko, 2013; Mensah et al., 2013). Religious socialization, for example, has been found to play a more vital role than leisure activities, such as sports, in helping migrants process trauma and adjust to new environments (Hurly, 2019).

Transnational caregiving involves complexities that immigrant caregivers navigate while balancing personal responsibilities and care from a distance. Religious connection help manage these demands by offering emotional and practical support, reinforcing caregivers' sense of purpose and connection (Reyes-Espiritu, 2022). Global care chains (Hochschild, 2000) refer to the transnational transfer of caregiving responsibilities. Understanding these dynamics is crucial (Brijnath, 2009). Religious identities and cultural connections facilitate the exchange of resources, values, and social networks between home and host countries (Ebaugh, 2004; Levitt, 2003). While these social connections foster resilience, they can also increase caregiving pressures by reinforcing culturally rooted obligations that are hard to meet across borders (Spitzer et al., 2003). Caregivers may use religious coping strategies, such as prayer, sacred ceremonies, and visits to religious places, to manage stress and enhance resilience (Abu-Raiya & Pargament, 2015; Malhotra & Thapa, 2015).

Religious community support is a key factor in predicting caregivers' quality of life, with friendships within religious communities contributing to well-being (Burgener, 1999). However, caregivers often experience lower levels of public religious engagement and report reduced satisfaction with the support provided by religious communities compared to non-caregivers (Malhotra & Thapa, 2015). More context-specific models are needed to align with caregivers' diverse experiences. Additionally, while religious coping varies across traditions, integrating these practices into mental health frameworks could provide benefits, emphasizing the importance of collaboration between mental health professionals and religious communities (Malhotra & Thapa, 2015). Further research is needed to explore how these practices evolve within diverse caregiving scenarios, as well as their potential to adapt to shifting cultural and social landscapes (Abu-Raiya & Pargament, 2015; Malhotra & Thapa, 2015; Reyes-Espiritu, 2022).

2. Materials and Methods

Theoretical Framework: Cultural Relativism

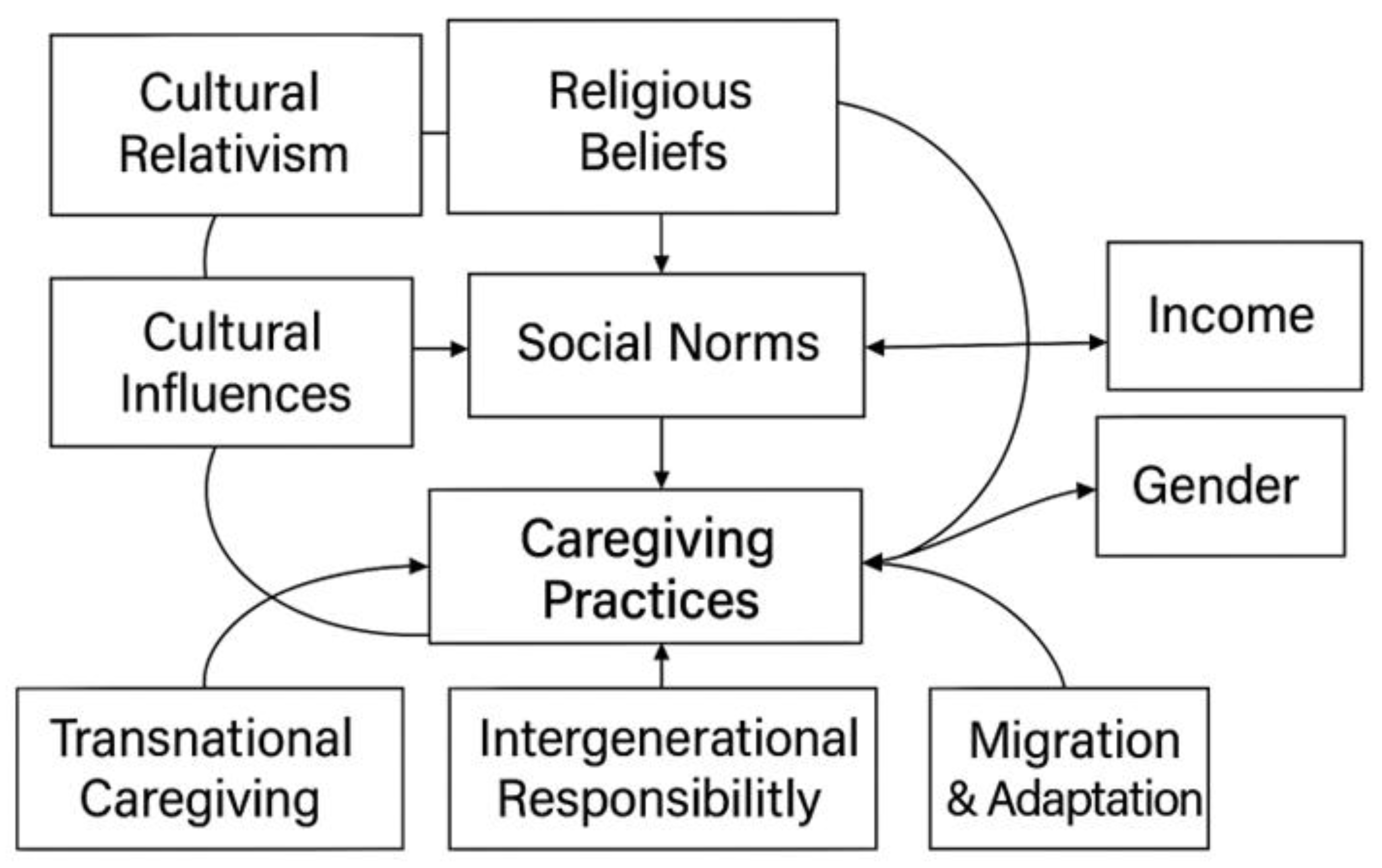

Cultural relativism is a concept that emerged from anthropology and has critical implications for understanding human behavior, ethics, and social norms (

Figure 1). It originated before anthropology's emergence and was popularized by Franz Boas to establish holistic cultural descriptions (Hahn, 2023). Boas argued that civilization is not absolute but relative, and our ideas and conceptions are true only as far as our civilization goes (Bargheer, 2017). Boas’s students, such as Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead, further developed these ideas, emphasizing the diversity of cultural practices and the importance of understanding them within their own contexts (Bargheer, 2017). The theoretical framework of cultural relativism provides a lens for understanding caregiving practices as deeply embedded within the cultural, social, and moral norms of specific communities. While it promotes appreciation of cultural diversity and challenges ethnocentrism, critics argue it may hinder critical assessment of cultural conflicts and human rights violations (Hahn, 2023; Singer, 1999).

Cultural relativism emphasizes the need to understand cultural practices within their historical and social contexts, rather than judging them by external standards (Boas, 1940). This principle can be applied to caregiving practices, encouraging an appreciation of how caregiving norms are shaped by specific cultural and contextual factors (Hahn, 2023; Singer, 1999). This framework is particularly relevant in exploring caregiving among diverse populations and transnational caregiving contexts, where cultural norms and values influence caregiving behaviors, obligations, and expectations. Cultural relativism posits that cultural practices must be understood within their unique contexts rather than judged by external or universal standards (Herskovits, 1958; Kozaitis, 2018; Tilley, 2000).

When applied to intergenerational transnational caregiving, this perspective reflects how caregiving practices are shaped by religious beliefs, cultural traditions, and historical legacies. These influences create caregiving approaches that reflect the values of their cultural heritage while being adapted to the realities of a new sociocultural environment. For instance, in collectivist societies, including Nigerian Christian communities (Ebimgbo et al., 2018), caregiving is often viewed as a communal responsibility, shaped by interdependence, reciprocity, and religious duty (Hanssen & Tran, 2019; Pyke & Bengtson, 1996). African cultural traditions, such as the Ubuntu philosophy which upholds the belief that a person’s well-being is tied to the community frame caregiving as a moral obligation to support older adults as custodians of cultural and religious heritage, emphasizing community well-being over individual autonomy (Ikeorji, 2024; Rutagumirwa et al., 2020). In contrast, caregiving in individualist societies often prioritizes personal choice and autonomy, with formalized care systems supplementing familial roles (Funk & Kobayashi, 2009; Pyke & Bengtson, 1996).

The principle of cultural relativism is particularly important in understanding caregiving norms across different religious and cultural contexts, as seen in Confucian filial piety, which frames caregiving as an ethical duty tied to societal harmony (Canda, 2013; Nguyen, 2023). Judeo-Christian traditions view it as a divine obligation linked to spiritual rewards (Blidstein, 2005; Trimm, 2017). Islamic teachings emphasize caregiving as a religious obligation, prioritizing respect and compassion (Abdalla & Patel, 2010; Halim et al., 2024). Hinduism views caregiving as a moral duty rooted in karma, reincarnation, and family roles (Dewar et al., 2015; Hinton et al., 2008). These diverse caregiving frameworks stress the need to interpret caregiving practices within their cultural and religious contexts rather than through a universal lens.

Cultural relativism also provides a critical framework for analysing caregiving practices in transnational contexts, where caregivers often navigate conflicting cultural norms between their home and host countries (Andruske & O'Connor, 2020; Brijnath, 2009; Spitzer et al., 2003. Migrant caregivers often navigate cross-cultural caregiving tensions as they balance norms with the realities of living in new socio-cultural settings (Andruske & O'Connor, 2020). These tensions underscore the importance of understanding caregiving as a dynamic and culturally contingent practice shaped by migration, globalization, and changing family structures (Baldassar et al., 2014; Schmalzbauer, 2004).

A key strength of cultural relativism is its emphasis on the moral and ethical diversity of cultural practices (Kozaitis, 2018; Tilley, 2000). Applied to caregiving, this perspective recognizes that caregiving is not a universal experience but is shaped by the specific cultural, religious, and social contexts in which it occurs. This framework offers an alternative to ethnocentrism, which is the tendency to view one's own culture as superior. Cultural relativism provides a perspective for understanding cultural variations within their own contexts rather than imposing external value judgments. In global ethics, it raises debates about the tension between cultural specificity, human rights, and universal values (Freeman, 2013). While it promotes tolerance and understanding, it also raises questions about the universality of human rights, as cultural differences influence what is recognized as a right (Tilley, 2000). The concept rejects universal truths and values, asserting that concepts of right and wrong are only valid within specific cultural frameworks (Singer, 1999).

Despite its merits in challenging assumptions and promoting open-mindedness, some philosophers argue that cultural relativism may allow repugnant practices to go unchallenged (Ulin, 2007). The debate surrounding cultural relativism continues to shape anthropological discourse and its application in understanding diverse societies (Kozaitis, 2018; Ulin, 2007). Critics argue that an overemphasis on cultural specificity may obscure power dynamics, gender inequalities, or ethical tensions within caregiving practices. Some argue that it can lead to moral relativism, where any practice, no matter how harmful, can be justified based on cultural context (Tilley, 2000). For instance, caregiving norms in many societies disproportionately burden women, perpetuating gendered expectations that limit their autonomy and well-being (Arroyo et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2016). Additionally, the framework’s resistance to universal standards may hinder efforts to establish global caregiving policies or address systemic caregiving challenges, such as those arising from migration and aging populations (Dunn & Gallagher, 2021; Zechenter, 1997). These critiques emphasize the need to balance cultural relativism with critical analyses of power, equity, and structural factors. Despite these limitations, cultural relativism provides a valuable theoretical framework for understanding caregiving as a practice deeply embedded in cultural and religious contexts. It shows how caregiving is influenced by social norms, religious beliefs, and historical backgrounds, offering a more comprehensive and respectful perspective on diverse caregiving practices. This study explores how they navigate these responsibilities, balancing religious beliefs, cultural traditions, and the realities of caregiving across borders.

Research Focus

Guided by the framework of cultural relativism, this study focuses on how Nigerian Christian immigrants in northern British Columbia interpret and practice elder care across borders through the lens of their cultural and religious values. It explores how caregiving responsibilities are shaped by Christian teachings, moral obligations, and Nigerian cultural expectations. The central research question asks: How do Nigerian Christian immigrants in northern BC integrate religion and culture into their transnational caregiving practices? The study further describes how these caregivers adapt to the complexities of caregiving in a Canadian context, how intergenerational caregiving values are sustained, and how participants negotiate cultural continuity and change in a transnational setting.

Data Collection and Analysis

A pre-interview survey was conducted to gather foundational demographic, socioeconomic, and caregiving experiences as they relate to religion and culture from the study participants. This ensured a detailed understanding of the participants’ backgrounds. Narrative interviews, averaging one hour, provided in-depth insights into participants’ caregiving roles, motivations, and challenges. Through open-ended questions, participants were prompted to share their thoughts on how religion and culture impact their caregiving roles, discussing societal norms and family dynamics that influence caregiving responsibilities. Participants reflected on the cultural and religious norms that shaped their caregiving practices, highlighting how these influences impacted their sense of responsibility, their emotional experiences, and their interactions with family members. Participants were encouraged to describe their caregiving approaches before and after immigrating to Canada, sharing how their caregiving choices and responsibilities evolved as they adjusted to life in a northern Canadian context. This conversational and adaptable approach facilitated open discussions that illuminated how religion and culture interact to influence caregiving practices in transnational contexts, particularly in navigating longstanding approaches expectations and adapting to new caregiving environments.

Thematic analysis was used to explore participants’ narratives and identify recurring themes related to the role of religion and culture in caregiving (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This method was selected for its adaptability and thoroughness in capturing both overt and subtle meanings within the data, making it particularly effective for examining the intricate intersections of religion, cultural expectations, and caregiving dynamics. The analysis adhered to Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework, ensuring a methodical and detailed examination. The process began with an immersion phase, involving multiple readings of transcripts to become well-acquainted with the depth and nuances of each participant's narrative. Initial codes were generated in an inductive manner, concentrating on both explicit content and underlying meanings linked to religious obligations, cultural expectations, and caregiving motivations. Through this iterative process, recurring elements were identified and categorized into distinct themes and subthemes.

To bolster the reliability and depth of the analysis, the coding process was conducted iteratively, involving several rounds of refinement and review. Themes and subthemes were further honed through constant comparison, ensuring they accurately represented the diversity and intricacy of participants’ experiences. Thematic analysis was particularly effective in pinpointing patterns of meaning throughout the data while also recognizing unique and context-sensitive viewpoints (Clarke & Braun, 2014). To maintain credibility, themes were consistently cross verified against the original transcripts, ensuring they aligned with participants' narratives and upheld the integrity of the data (Nowell et al., 2017). The analysis also embraced reflexivity, critically assessing the research process to minimize bias and ensure an accurate representation of participants’ perspectives. This method revealed both the endurance of cultural norms and their adjustment in the transnational context, providing rich insights into the interaction of religion, migration, culture, and caregiving. By systematically analyzing narratives, the analysis showcased recurring themes while also acknowledging the unique experiences that contribute to broader culture and religion (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Clarke & Braun, 2014). Rigor in this qualitative research was established through strategies designed to ensure trustworthiness, including prolonged engagement with the data, iterative coding, and the refinement of themes (Hamilton, 2020; Morse, 2015).

3. Results

This research involved ten Nigerian immigrant caregivers living in Northern British Columbia. Participants were selected using a mix of snowball and purposeful sampling methods to capture a range of diverse and insightful viewpoints on the dynamics of transnational caregiving related to religion and culture.

Table 1 represents the participants’ demographics. The sample reflects an equal gender distribution of five women and five men. The age of the participants ranged from mid-20s to early 50s, reflecting a broad spectrum of caregiving experiences shaped by different stages of life. The educational attainment of participants was notably high, with seven participants having earned postgraduate degrees (master’s or PhD), while three have bachelor’s degrees. Moreover, participants represented a range of professional fields, including nursing, physiotherapy, social work, community services, and business analysis. These professional experiences offered a variety of perspectives for understanding and navigating duties, especially striking a balance between personal and professional caregiving responsibilities. Nine of the participants were married, and one participant was single, which adds depth to the analysis. The study involved participants with varying lengths of stay in Canada (2 to 15 years). This reflects differences in integration into Canadian society and exposure to local caregiving norms and perspectives, allowing us to explore how caregiving roles evolve with time spent in the host country.

Overview of Themes and Subthemes

This section introduces the main themes and subthemes that capture how participants make meaning of transnational caregiving through religious and cultural lenses. Based on the thematic structure presented in

Table 2, two overarching themes were identified: the role of religion in caregiving and the role of culture in caregiving. The religious theme includes three subthemes: caregiving as a moral and religious duty, spiritual and parental blessings as rewards for caregiving, and religious fulfillment in transnational caregiving. The cultural theme comprises four subthemes: cultural obligation and social expectations, intergenerational transmission of caregiving responsibilities, resistance to institutionalized care and cultural adaptation, and the role of family networks. The themes and subthemes that follow provide insight into the intersecting moral, social, and emotional dimensions of caregiving across borders, drawing directly on participants lived experiences.

The Role of Religion in Caregiving

Participants emphasized the influence of religious teachings in shaping their approach to elder care, viewing it as a religious duty closely tied to honoring their parents. For many, caregiving is deeply rooted in their religious beliefs and perceived as both a moral and spiritual obligation. This commitment remains strong even across borders, as participants continue to provide care from a distance, drawing strength from their religious beliefs to navigate the emotional and logistical challenges of transnational caregiving.

Religious Teachings Framed Caregiving as a Moral Obligation

Participants framed caregiving as a religious duty, guided by biblical teachings. Religious values reinforced their commitment to elder care, even across borders, as they viewed caregiving as an act of obedience to God. P10, Male, emphasized the biblical foundation of caregiving: "I’m a Christian by practice, and the Bible speaks about honoring our parents… taking care of our parents, and I’m a strong believer of that.” Similarly, P7, Male, described caregiving as an extension of his religious beliefs: "I naturally also feel obligated to do that for them... The next big thing that has influenced my decision to take care of my folks is religion." For some, religious teachings shaped their early understanding of caregiving as a moral responsibility, which they carried with them even after migrating. P1, Female, linked her motivation to her Catholic upbringing: "Growing up as a Catholic, I was taught that it’s your responsibility to help others... It doesn’t matter if I know you, if you're in need, it becomes my responsibility." P5, Female, also reflected on how religious beliefs influenced her caregiving role: "I do believe that those religious teachings have actually influenced how I have come to believe about taking care of my parents."

Religious beliefs reinforced a sense of duty in long-distance caregiving. P3, Female, highlighted biblical teachings on obedience: "There’s definitely a lot of 'obey your parents,' and this is what Christ would like..." For P8, Male, religion also reinforced cultural caregiving values, strengthening their sense of responsibility even while living abroad. P8, Male, noted: "Religion has just come to reposition the value of our ancestors... to take care of their loved ones as the Bible instructs." This suggests that for many caregivers, religious teachings did not replace cultural expectations but rather reinforced them, creating a dual sense of duty that persisted across borders. By framing caregiving as a religious obligation, participants found ways to remain actively involved in their parents' care despite being geographically distant. Religious beliefs not only shaped their motivation to provide care but also influenced how they provided support transnationally.

Spiritual and Parental Blessings as Rewards for Caregiving

Caregiving was not just a duty but also a source of blessings, reinforcing commitment to elder care despite the demands of transnational caregiving. P8, Male, emphasized the rewards: "There is a blessing that comes with it." Parental blessings were particularly significant. P4, Female, shared: "My mother prayed for me, she said, ‘What you did for me, your child will do for you.’" P2, Female, viewed prayers as encouragement: "I always saw it as a kind of blessing... Just their prayers and the fact that they would say ‘thank you’ would somehow help you out in the future" [implying that parental prayers were believed to bring divine favor and future well-being].

Biblical teachings reinforced the belief that honoring parents brings divine favor. P3, Female, stated: "One of my religious beliefs is that if you honor your father and mother, you will live a long life." P8, Male, added: "The Bible says honor your parents so that it may be well with you." Certain participants found lifelong reassurance in these beliefs. P6, Male, reflected on his father’s final words: "Before my dad passed on, he said, 'My God will bless you.' Those words are eternal." He further emphasized the biblical promise: "The Bible says if you honor your parents, your days will be long." These narratives illustrate how religious teachings shaped caregiving for these participants as both a moral duty and a pathway to spiritual and familial rewards. The principle of honoring one's parents, deeply embedded in biblical and cultural traditions, was reflected in their lived experiences. It motivated care through the promise of divine favor and future blessings. For these participants, such beliefs offered ongoing reassurance and reinforced their commitment to elder care, even when faced with distance, pressure, and sacrifice.

Fulfilment in Transnational Caregiving

Participants described a deep sense of fulfilment rooted in their religious values, reinforcing their commitment to elder care despite geographical distance. P1, Female, linked this fulfilment to biblical teachings on kindness: "The Bible encourages us to care for others... It’s not all about you, it’s about kindness, and that gives me a sense of fulfilment." This highlights how caregiving aligns with both personal and religious values, providing emotional and moral satisfaction beyond its practical responsibilities. P9, Male, expressed a similar sense of fulfilment: "The fulfilment ... brings a lot of relief and a lot of joy. ... Knowing also that not only am I able to support my parents but also support the people that are caring for them financially, emotionally, even with the level of the knowledge I have had since coming to Canada about caregiving." P9, Male, found reassurance in knowing his parents were well cared for, regardless of location: "Those are other fulfilment[s] that I found in that. Knowing fully well that whether I'm in Nigeria or here in Canada, my parents are adequately cared for, and they are being taken care of." These narratives demonstrate how caregiving, shaped by religious beliefs, provides a sense of purpose, emotional comfort, and moral reward, sustaining participants' involvement in elder care across borders.

The Role of Culture in Caregiving

Participants recounted how culture played a vital role in their motivation to provide care and support to family members transnationally. The following themes- obligation and social expectations, intergenerational transmission of caregiving responsibilities, resistance to institutionalized care and cultural adaptation and family networks- emerged from culture as it relates to transnational elder care for Nigerian elderly.

Cultural Obligation and Social Expectations

In Nigerian cultures, caregiving is a shared duty embedded in societal values and expected across religious and ethnic lines. P4, Female, emphasized: "Whether you're Muslim, Christian, or a pagan worshipper, it just doesn't matter. That aspect of life [caring for one’s parents]is something that cuts across all ethnic groups and religions in Nigeria." This obligation extends beyond presence, shaping how care continues from abroad. P10, Male, stated: "Culture is a vital component of caregiving. In Africa, caregiving is embedded into our culture. You grow up knowing that it's your responsibility to care for your parents." P9, Male, added: "Our culture pays homage and holds in high regard children who take care of their parents." Even at a distance, caregiving remains essential, with migrants ensuring parental well-being through financial and emotional support.

Failing to provide care carries consequences. P3, Female, noted: "If you don’t do what is expected, you’re being discriminated against." P9, Male, reinforced this: "As a child, for instance, if you are not able to take care of your parent, society frowns at it. In fact, it may be considered taboo." The expectation to provide care remains strong, even when migration limits physical involvement. Social exclusion can follow neglect. P7, Male, stated: "If you don’t look after your parents, from my culture, people may excommunicate you. You may be excommunicated from your community, and people may start keeping distance from you." P9, Male, explained: "If parents are growing old and their children are not taking care of them, it will be considered an act of irresponsibility. That’s the way our culture views it." These narratives show that migration does not erase caregiving duties but reshapes them, with transnational caregivers fulfilling obligations through ongoing support despite physical separation.

Intergenerational Transmission of Caregiving Responsibilities

Caregiving is passed down through generations, shaping obligations that persist across borders. Participants described learning caregiving practices by observing their parents, reinforcing caregiving as both a familial and cultural expectation. P10, Male, explained, "I'll say it's something that was instilled in me because I saw them do it for their own folks, so I naturally also feel obligated to do that for them." P6, Male, shared, "I watched my dad take care of his mother... that encourages you to do the same." P2, Female, reflected on caregiving as a generational responsibility: "When she did that, and she's speaking to me from her lived experience of taking care of her mother-in-law and her dad, I just felt it's something I should also take after as well."

Caregiving is also modelled for younger generations, reinforcing long-term expectations despite distance. P6, Male, noted, "My kids are also looking at me to do it for my parents... they are really learning." He added, "We do it so that as we are doing it, our own children would see that we are involved in taking care of our own parents. So that in essence, they will learn it." P4, Female, connected this to cultural teachings: "There’s an adage in Igbo land that says that when a parent finishes training a child, the child trains the parents, and it relates to caregiving." These narratives highlight how caregiving remains a transgenerational duty, shaping the way participants continue to care for aging parents from afar. Even in transnational contexts, caregiving is sustained through financial, emotional, and logistical support, ensuring that cultural expectations are upheld across generations.

Resistance to Institutionalized Care and Cultural Adaptation

Participants highlighted the contrast between caregiving practices in Nigeria and Canada, emphasizing the strong preference for family-based elder care in Nigerian culture. Placing aging parents in care homes is widely considered unacceptable. P3, Female, described her reaction to Canadian practices: "It was a culture shock for me seeing a lot of elderly people in homes, as back home we don’t have homes for them." P4, Female, reinforced this view: "It would be unheard of to place your parents in a home. It’s considered a taboo in our culture." Maintaining direct family involvement in elder care remains a priority, even in transnational settings. P5, Female, explained, "From my culture, it’s taboo for you not to take care of your elderly ones. In Canada here, once your parents are aging, you can take them to the Old People's Home." P2, Female, added, "So it's a cultural thing, even if they are staying alone, there would always be like someone that would take care of the person, who is either a close relative or a paid caregiver. But care homes are not common. You either do it or you get someone who can help you take care of the elderly."

While some participants acknowledged the social benefits of institutional care, such as opportunities for older adults to socialize, they still prioritized family oversight. P2, Female, shared, "I would like my father-in-law to go to a care home just to socialize with others, but I still think it’s important to have someone closely connected to the family to keep an eye on him." P8, Male, emphasized cultural expectations against institutionalized care: "In our community, people are expected to care for their older adults within the home. Sending an elderly parent to a care facility is often frowned upon." These perspectives illustrate how Nigerian cultural norms shape caregiving expectations, even across borders. Despite exposure to different elder care systems in Canada, participants continue to prioritize family involvement, adapting caregiving strategies to uphold culturally rooted values while managing transnational responsibilities. This ongoing preference is not simply due to a lack of long-term care infrastructure in Nigeria but rather reflects deeply ingrained cultural norms that value home-based elder care. Even after migration, Canadian models of institutional care have limited influence, as participants maintain strong commitments to family-centered caregiving shaped by cultural expectations.

Extended Family Involvement in Caregiving

Caregiving is characterized by collective effort within the extended family. P5, Female explained, "I had other family members step in to assist me too," illustrating the shared nature of caregiving responsibilities. P1, Female further elaborated on the communal aspect of caregiving, noting, "In Nigeria, caregiving is more communal... It’s not just on one person; the family comes together to help." These reflections demonstrate how family networks distribute caregiving duties, easing the burden on any single individual. While caregiving was a shared responsibility, P7, Male also noted that this structure remains influential even in a transnational context, where those living abroad rely on family networks back home to provide direct care. He explained, "We have to ensure other systems are put in place, so that it becomes a smooth aging process for my family, and at the same time, being able to enhance the life of those at home who now play the roles of caregiving." These accounts highlight how caregiving is sustained through collective family efforts, ensuring that older adults receive support both from those present and from relatives living abroad who contribute in various ways.

4. Discussion

This study examines the role of religion and culture in shaping caregiving practices among Nigerian immigrants in Northern BC. By acknowledging caregiving as deeply embedded within the participants’ cultural, social, and religious frameworks, cultural relativism helps illuminate how traditions, religious beliefs, and migration intersect to shape participants’ caregiving responsibilities and decisions. Among Nigerian immigrants, caregiving is both a religious practice and a social responsibility, upheld by Christian ethics as a sacred duty across borders. Christian beliefs emerge as a key motivator for caregiving, with participants viewing it as a sacred duty rooted in biblical commandments, particularly honoring father and mother as an act of obedience to God. Among Nigerian immigrants, caregiving is reinforced as both a spiritual practice and a social responsibility, where Christian ethics uphold caregiving as a sacred duty despite the challenges of transnational caregiving.

The findings are consistent with existing research, which identifies religion as both a source of emotional support and a framework for cultural expectations in caregiving (Hinton et al., 2008; Kristanti et al., 2019; Zahed et al., 2019). Religious beliefs frame caregiving as a moral and divine duty, reinforcing behaviors that align with teachings on compassion, respect, and responsibility (Abdalla & Patel, 2010; Halim et al., 2024). These religious frameworks are culturally embedded, varying across contexts yet carrying equal significance within their communities (Kozaitis, 2018; Tilley, 2000). Previous literature also found that religious teachings, serve not only as a familial obligation but also as a means of preserving social cohesion and moral integrity (Esiaka & Luth, 2023; Ezulike et al., 2024; Rutagumirwa et al., 2020).

The study reveals the role of culture in shaping transnational eldercare among Nigerian immigrants in Canada. These practices remain central to their cultural identity, even as they provide care across borders. This dynamic aligns with broader patterns observed in other cultural contexts. For instance, in East Asian societies, filial piety strongly influences family interactions, positioning the care of elderly parents as both a moral duty and a source of pride, underscoring its deep cultural significance (Canda, 2013; Nguyen, 2023). Similarly, research has shown that transnational caregivers often reshape customary caregiving models to accommodate the realities of migration while maintaining cultural values (Hossain et al., 2024; Spitzer et al., 2003; Yoon, 2024).

The findings indicate that caregiving responsibilities are viewed as intergenerational expectations, passed down through role modelling. Parents in Canada model caregiving to their children, sustaining this value across borders. Participants observed their parents caring for their parents and older members of their family and viewed this as a blueprint for their own caregiving roles. This aligns with research showing that observed family caregiving shapes motivation and sustains caregiving practices across generations. (Piercy & Chapman, 2001; Rutagumirwa et al., 2020). This intergenerational continuity underlines how caregiving is rooted in communal values of reciprocity and interdependence (Kozaitis, 2018; Tilley, 2000). These norms contrast sharply with individualistic caregiving models, where formal care systems may augment or replace familial responsibilities (Pyke & Bengtson, 1996). Migration complicates this dynamic, requiring caregivers to adapt longstanding practices to new socio-cultural settings (Andruske & O'Connor, 2020; Brijnath, 2009).

The contrast between family-based care in Nigeria and institutionalized elder care in Canada was a recurring theme. Participants expressed a strong preference for family caregiving, reflecting Nigerian cultural norms that view placing older adults in care homes as taboo. However, this was not a uniform preference, as some acknowledged the social benefits of care homes. There was no clear correlation between length of time in Canada and greater acceptance of institutionalized care. While participants did not directly state that being in Canada was a dereliction of duty, some acknowledged a tension between migration and their caregiving responsibilities. Rather than seeing their absence as neglect, they adapted by providing financial, emotional, and logistical support from a distance. This aligns with studies underscoring the cultural significance of familial elder care in African societies (Imoh, 2022). While participants recognized the social benefits of care homes, they emphasized the necessity of family involvement. Cultural relativism contextualizes this preference within Nigerian caregiving values of reciprocity and communal responsibility. While migration exposes caregivers to alternative elder care models, such as institutional care in Canada, these influences do not easily override cultural norms. Instead, some participants adopt hybrid approaches blending customary expectations with selective elements of Canadian systems while still prioritizing home-based care as a moral and cultural duty (Baldassar & Merla, 2014).

Implications for Transnational Caregivers

The findings show that while Nigerian immigrants navigate geographical distance, they adjust transnational caregiving to align cultural expectations with migration realities, maintaining caregiving as a cultural and religious responsibility. Family members collectively support older adults, reducing the burden on individuals but requiring coordination from those abroad. As these caregiving practices continue across borders, there is a need for policies and resources that reflect these values. Religious organizations and cultural institutions could play a crucial role in reinforcing this communal model by facilitating resource-sharing and building transnational networks that support caregivers’ efforts. For example, organized support groups for Nigerian caregivers in Canada could serve as hubs for exchanging strategies, providing emotional support, and mobilizing financial assistance for elder care in Nigeria (Machoko, 2013; Mensah et al., 2013). Such initiatives could include diaspora-led caregiving workshops or financial support programs to ease the burden of cross-border caregiving.

The communal approach is a defining feature of Nigerian caregiving practices, but migration can complicate this culturally rooted model. Many caregivers rely on extended family in Nigeria to share responsibilities, reinforcing the need for strong transnational ties. Yet, sustaining elder care across borders is fraught with tension, requiring constant negotiation and adaptability. Maintaining these connections ensures that caregiving duties are distributed among family members, even when some live abroad. However, distance can limit direct involvement, making it necessary to find alternative ways to stay engaged. Policies and programs that support family reunification, visits, or remote coordination could strengthen these efforts, allowing caregivers to fulfil their roles while navigating the complexities of transnational caregiving.

Migration exposes caregivers to alternative eldercare practices, such as institutionalized care, which contrasts with the culturally ingrained preference for family-based caregiving in Nigerian society. While participants recognized the potential social benefits of care homes, they highlighted the importance of maintaining family oversight. This openness suggests that hybrid caregiving models integrating elements of family and institutional care could be explored. It also reflects a shift in long-standing caregiving expectations, showing how culturally rooted perspectives may be adapting within transnational contexts to accommodate new demands, resources, and realities. This nuanced perspective highlights the adaptability of transnational caregivers, who often adopt hybrid caregiving approaches that integrate elements of both cultural and institutionalized care models (Baldassar, 2008; Pyke & Bengtson, 1996). Policymakers and service providers could facilitate these hybrid approaches by offering culturally sensitive eldercare services that combine communal caregiving values with formal support structures. For example, Nigerian diaspora organizations could collaborate with local institutions to establish culturally tailored eldercare programs in Nigeria, ensuring that older adults receive professional care while maintaining strong family connections. In Canada, this might involve providing resources for diaspora communities to support their transnational caregiving roles, such as tax incentives for remittances used for elder care.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides valuable insights into the role of religion and culture in shaping transnational caregiving practices among Nigerian immigrants in Canada, several limitations While these participants provided rich qualitative insights, the focus on caregivers in Northern British Columbia offers a context-specific lens into caregiving experiences. Rather than aiming for broad generalizability, this study provides an in-depth understanding of how caregiving is shaped within a particular social, cultural, and geographical setting. Additionally, the sample's homogeneity- comprising exclusively Christian and highly educated participants- further narrows the scope of the study. This approach may overlook the diverse experiences of Nigerian caregivers from different religious, socio-economic, and educational backgrounds. It presents an opportunity for further investigation into how these additional intersectional factors influence caregiving motivations, practices, and challenges within transnational contexts.

The study’s emphasis on caregivers leaves unexplored the perspectives of elderly recipients of care, particularly how caregiving practices influenced by migration align with or diverge from older adults’ expectations and cultural values. This limits the understanding of how caregiving practices are perceived and experienced by the older adults themselves. It also excludes the perspectives of other family members in Nigeria who support caregiving duties, which could offer further insight into how care is coordinated across households and borders. Additionally, the reliance on participants' self-reported narratives introduces potential biases, such as social desirability bias or selective recall. Future research should aim to address these limitations by adopting a more diverse and representative sample, including caregivers from different religious, educational, and geographic backgrounds. Incorporating the voices of elderly care recipients would offer a more comprehensive understanding of transnational caregiving dynamics and reveal how caregiving practices are received and experienced on both ends. Additionally, longitudinal studies could provide deeper insights into how migration and cultural adaptation shape caregiving practices over time.

Exploring caregiving roles beyond the Nigerian and Christian context would enrich the field by offering comparative analyses across various cultural and religious groups. This could illuminate commonalities and differences in caregiving practices, further advancing the understanding of how cultural and religious frameworks intersect with transnational caregiving responsibilities. Despite these limitations, the study contributes to the literature by offering critical insights into transnational Nigerian caregivers, focusing on the importance of cultural and religious influences in shaping caregiving practices and offering avenues for more inclusive policy development and support systems.