Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

11 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Can activation functions derived from fractal series be used in neural networks like standard activations, and how do they affect performance?

- Do such fractal activations increase the expressive capacity of neural networks compared with existing choices?

- (i)

- We present a general recipe for converting Weierstrass- and Blancmange-type series into computationally stable activation functions (Section 2.3) and demonstrate their usability on ten public classification datasets.

- (ii)

- We quantify their expressivity through trajectory-length diagnostics, revealing super-ReLU growth and distinctive oscillatory fingerprints (Section 4).

2. Methodology

2.1. Neural Networks

2.2. Fractal Functions

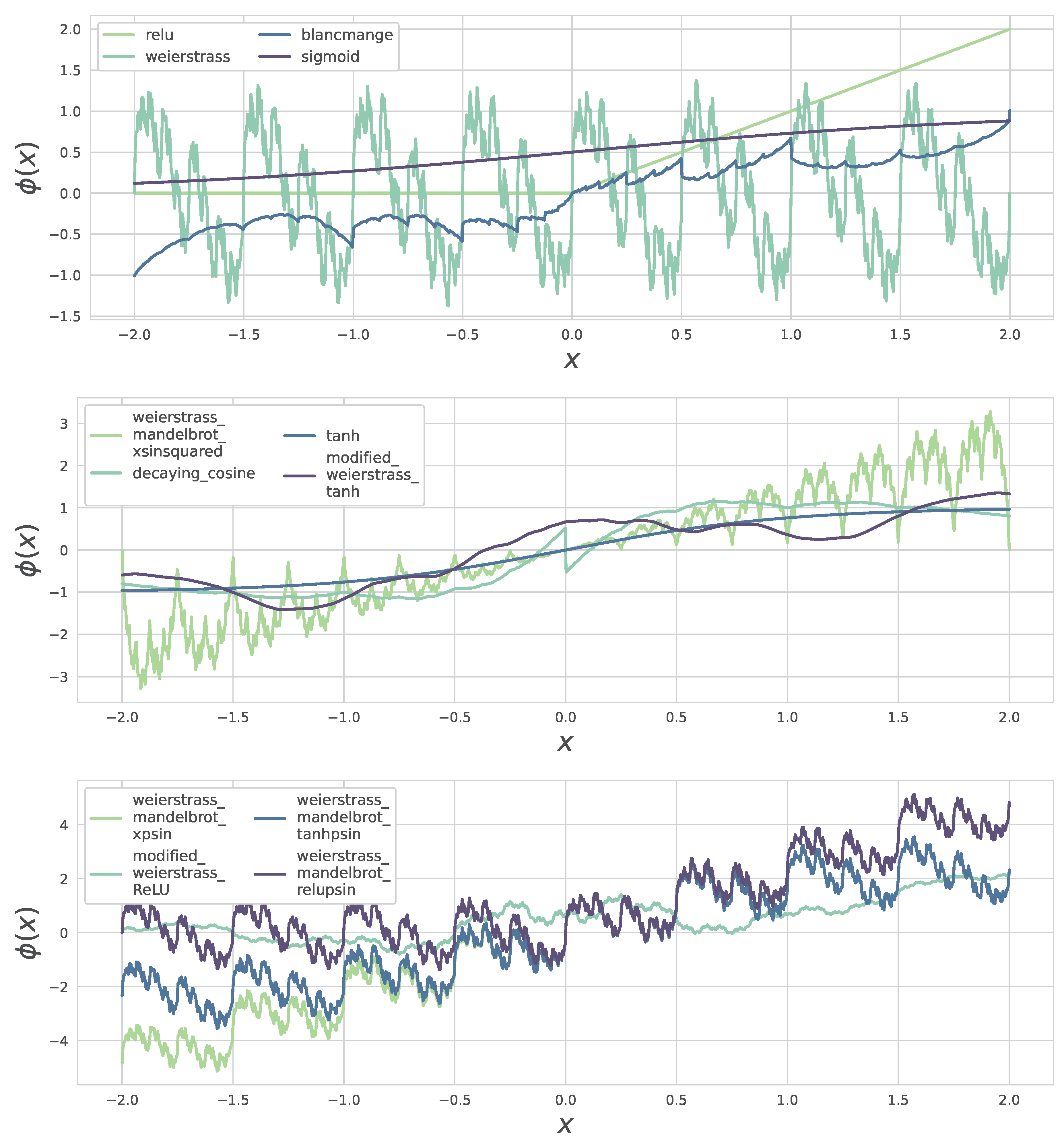

- They inject high-frequency detail even in shallow layers, increasing functional richness without extra parameters.

- They retain bounded outputs and controlled Lipschitz constants when and is Lipschitz continuous, [14].

- Most importantly, for gradient-based optimization, automatic differentiation remains well defined through finite truncation used in code.

- a)

- Exponential envelope. Multiplying by localises the oscillations and keeps activations bounded for large .

- b)

- Non-linear carriers. Replacing the cosine by , or injects asymmetric slopes that interact well with SGD-like optimisers.

2.3. Fractal Activation Functions

2.3.1. Modulated Blancmange Curve blancmange

2.3.2. Decaying Cosine Function decaying_cosine

2.3.3. Modified Weierstrass–Tanh modified_weierstrass_tanh

2.3.4. Modified Weierstrass–ReLU modified_weierstrass_ReLU

2.3.5. Classical Weierstrass Function weierstrass

2.3.6. Weierstrass–Mandelbrot Variants

3. Classification Experiments

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Classification Results

Dominant Fractal Variants

Classical Baselines

Variance and Optimiser Effects

Sanity Check: Classical Weierstrass

Summary

4. Expressivity of Fractal Activations

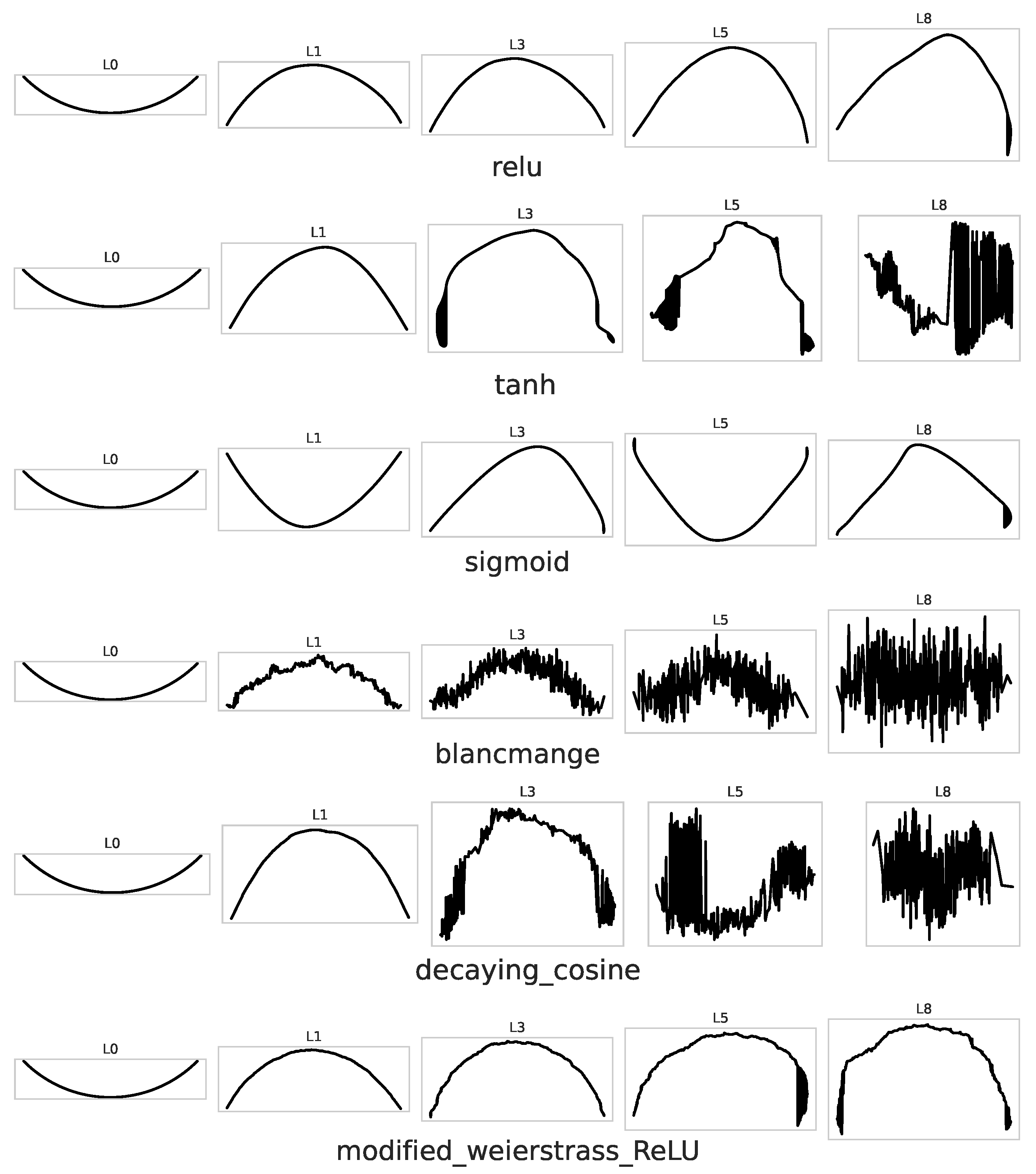

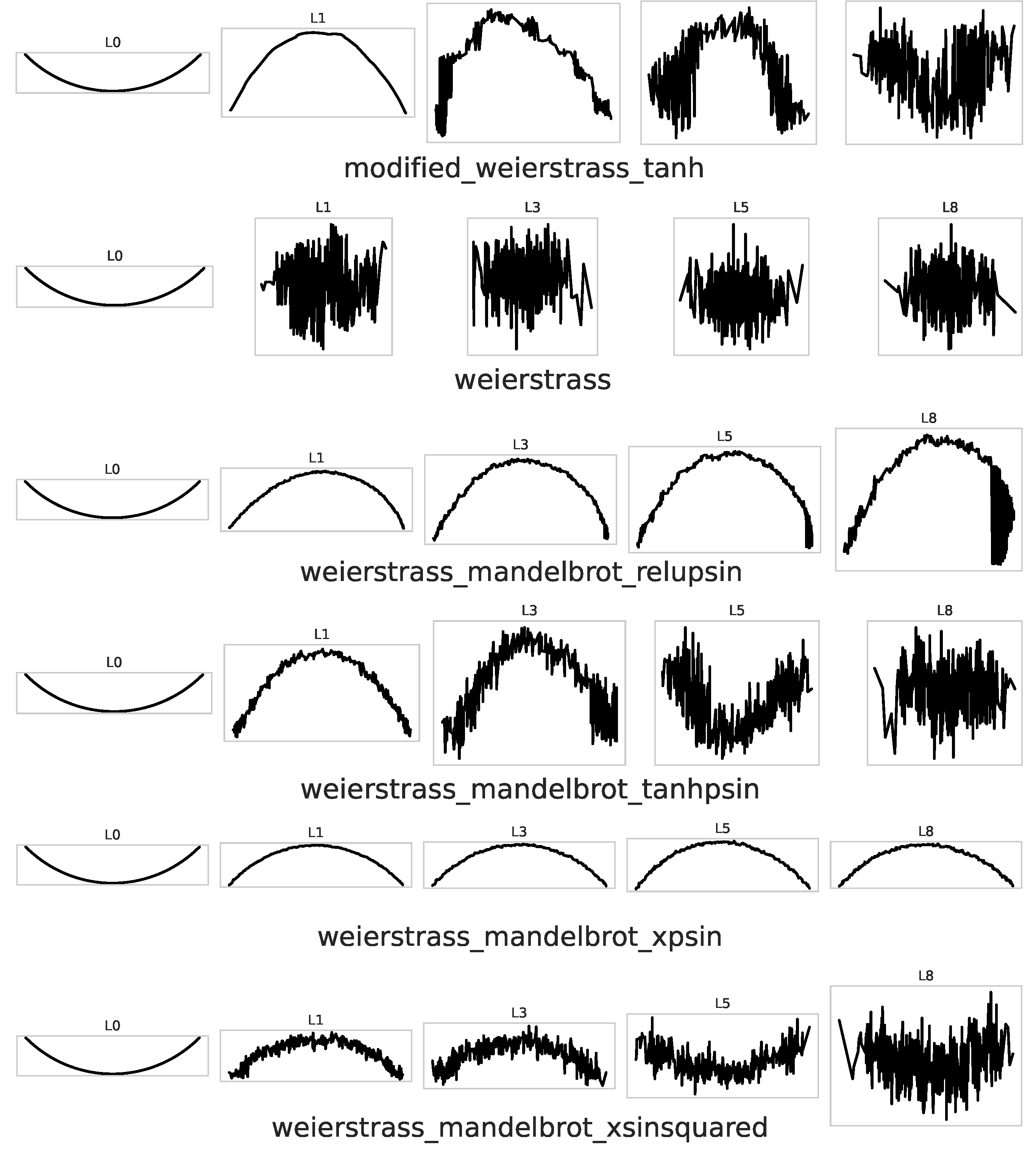

- (a)

- Trajectory length points. Exponential growth with ℓ indicates that the network is bending and stretching the curve, hence can represent highly non-linear functions.

- (b)

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis) strip We project onto the first two principal components for layers to visualise how folds accumulate.

4.1. Observed Behaviour

Arc-length growth.

PCA Strips

Summary

5. Discussion/Conclusion

- (a)

- Depth replacement. Measure whether a shallow network equipped with fractal activations can match or outperform a deeper classical model on the same task. Such a study would clarify how much “effective depth’’ the fractal folding provides.

- (b)

- (c)

- Parameter search. Systematically tune the geometric weights of the Weierstrass sums and the envelope decay to balance expressivity and gradient magnitude. A Bayesian search over this small hyper-space may yield task-specific defaults.

- (d)

- Complexity/Multidimensionality of a Dataset Another interesting perspective would be to analyze datasets for their complexity, e.g., using support vector machines and counting the kernel dimensions, and then relating this sort of complexity/data dimensionality to the usage of fractal activation functions for normalized neural network architectures. I.e., finding out whether the induced fractal folding can compensate for high-dimensional data complexity and thus improve accuracy.

- (e)

- Convolutional and/or Transformer Architectures

Code Availability

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Neural Networks for Pattern Recognition, first ed.; Advanced Texts in Econometrics, Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; p. 502. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y. Theoretical Framework for Back-Propagation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1988 Connectionist Models Summer School; Touretzky, D.; Hinton, G.; Sejnowski, T., Eds., Pittsburgh, PA, 1988; pp. 21–28. Accessed on 2025-05-22.

- Householder, A.S. A Theory of Steady-State Activity in Nerve-Fiber Networks: I. Definitions and Preliminary Lemmas. The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 1941, 3, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2010), Haifa, Israel, 06 2010.

- Poole, B.; Lahiri, S.; Raghu, M.; Sohl-Dickstein, J.; Ganguli, S. Exponential Expressivity in Deep Neural Networks Through Transient Chaos. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 29; Lee, D.D.; Sugiyama, M.; von Luxburg, U.; Guyon, I.; Garnett, R., Eds., Barcelona, Spain; 2016; pp. 3360–3368. [Google Scholar]

- Raghu, M.; Poole, B.; Kleinberg, J.; Ganguli, S.; Sohl-Dickstein, J. On the Expressive Power of Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; Precup, D.; Teh, Y.W., Eds., Sydney, Australia, 06–11 Aug 2017; Vol. 70, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2847–2854.

- Sohl-Dickstein, J. The boundary of neural network trainability is fractal, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2402.06184].

- Takagi, T. A Simple Example of the Continuous Function without Derivative. Proceedings of the Physico–Mathematical Society of Japan, Series II 1903, 1, 176–177. [Google Scholar]

- Allaart, P.C.; Kawamura, K. The Takagi Function: A Survey. Real Analysis Exchange 2011, 37, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zähle, M.; Ziezold, H. Fractional derivatives of Weierstrass-type functions. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 1996, 76, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B.B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature, 1st ed.; W. H. Freeman and Company: San Francisco, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Weierstraß, K. , die für Keinen Werth des Letzteren Einen Bestimmten Differentialquotienten Besitzen. In Ausgewählte Kapitel aus der Funktionenlehre: Vorlesung, gehalten in Berlin 1886 Mit der akademischen Antrittsrede, Berlin 1857, und drei weiteren Originalarbeiten von K. Weierstrass aus den Jahren 1870 bis 1880/86; Springer Vienna: Vienna, 1988; pp. 190–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, G.H. Weierstrass’s Non-Differentiable Function. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1916, 17, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuev, S.; Kabalyants, P.; Polyakov, V.; Chernikov, S. Fractal Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Energy Technologies (ICECET); 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Gao, Z.; Wang, J.; Lu, M.; Shi, J. Fractal graph convolutional network with MLP-mixer based multi-path feature fusion for classification of histopathological images. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 212, 118793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, G.F.; Lumini, A.; Neves, L.A.; do Nascimento, M.Z. Fractal Neural Network: A new ensemble of fractal geometry and convolutional neural networks for the classification of histology images. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 166, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.Y. Fuzzy Hopfield neural network clustering for single-trial motor imagery EEG classification. Expert Systems with Applications 2012, 39, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Muhammad, K. Characterizing Complexity and Self-Similarity Based on Fractal and Entropy Analyses for Stock Market Forecast Modelling. Expert Systems with Applications 2020, 144, 113098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubitzek, S.; Neubauer, T. A fractal interpolation approach to improve neural network predictions for difficult time series data. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 169, 114474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubitzek, S.; Neubauer, T. Taming the Chaos in Neural Network Time Series Predictions. Entropy 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souquet, L.; Shvai, N.; Llanza, A.; Nakib, A. Convolutional neural network architecture search based on fractal decomposition optimization algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 213, 118947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florindo, J.B. Fractal pooling: A new strategy for texture recognition using convolutional neural networks. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 243, 122978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, H.; Monro, S. A Stochastic Approximation Method. Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1951, 22, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukkamala, M.C.; Hein, M. Variants of RMSProp and Adagrad with Logarithmic Regret Bounds. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2017), Sydney, Australia, 08 2017; Vol. 70, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 2014, arXiv:1412.6980 2014, v9, 01–13v9, 01–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchi, J.C.; Hazan, E.; Singer, Y. Adaptive Subgradient Methods for Online Learning and Stochastic Optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2121–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, M.D. ADADELTA: An Adaptive Learning Rate Method. CoRR 2012, abs/1212.5701, 01–13, [1212.5701]. Accessed 21 May 2025.

- Herrera-Alcántara, O.; Castelán-Aguilar, J.R. Fractional Gradient Optimizers for PyTorch: Enhancing GAN and BERT. Fractal and Fractional 2023, 7, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Alcántara, O. Fractional Derivative Gradient-Based Optimizers for Neural Networks and Human Activity Recognition. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera-Martin, E.; Gómez-Aguilar, J.F.; Solís-Pérez, J.E.; Hernández-Pérez, J.A.; Escobar-Jiménez, R.F. Artificial neural networks: a practical review of applications involving fractional calculus. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 2022, 231, 2059–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubitzek, S.; Mallinger, K.; Neubauer, T. Combining Fractional Derivatives and Machine Learning: A Review. Entropy 2023, 25, 01–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Xu, Z. λ-FAdaMax: A novel fractional-order gradient descent method with decaying second moment for neural network training. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 279, 127156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Because converges when . |

| 2 | Unless noted otherwise we use the same truncation depths in the expressivity experiments of Section 4. |

| 3 | Means and standard deviations are taken over 40 random splits; Std measures robustness, i.e. the error over 40 splits. |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sgd | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.9148 | 0.0203 | 0.9506 | 0.8642 |

| sgd | sigmoid | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| sgd | tanh | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| adadelta | blancmange | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| sgd | relu | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| adam | blancmange | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| adadelta | sigmoid | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| sgd | blancmange | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| rmsprop | blancmange | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| adam | sigmoid | 0.9140 | 0.0196 | 0.9444 | 0.8642 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adam | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7666 | 0.0231 | 0.8225 | 0.7013 |

| adadelta | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7646 | 0.0207 | 0.8139 | 0.7273 |

| rmsprop | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7644 | 0.0220 | 0.8225 | 0.7143 |

| adadelta | relu | 0.7609 | 0.0213 | 0.7965 | 0.7143 |

| adagrad | sigmoid | 0.7583 | 0.0210 | 0.8095 | 0.7143 |

| adagrad | tanh | 0.7554 | 0.0275 | 0.7965 | 0.6537 |

| adagrad | relu | 0.7506 | 0.0288 | 0.8009 | 0.6623 |

| adadelta | tanh | 0.7472 | 0.0222 | 0.7835 | 0.6970 |

| adam | tanh | 0.7420 | 0.0255 | 0.7922 | 0.6623 |

| adam | relu | 0.7409 | 0.0241 | 0.7922 | 0.6710 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adadelta | decaying_cosine | 0.5923 | 0.0700 | 0.7538 | 0.3846 |

| rmsprop | decaying_cosine | 0.5923 | 0.0689 | 0.7846 | 0.3846 |

| adam | decaying_cosine | 0.5869 | 0.0635 | 0.7077 | 0.3846 |

| adadelta | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xpsin | 0.5819 | 0.0624 | 0.7231 | 0.4615 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xpsin | 0.5696 | 0.0703 | 0.7077 | 0.4000 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xsinsquared | 0.5669 | 0.0500 | 0.6615 | 0.4615 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_tanhpsin | 0.5669 | 0.0675 | 0.7077 | 0.4154 |

| sgd | tanh | 0.5650 | 0.0680 | 0.7231 | 0.4615 |

| adadelta | blancmange | 0.5581 | 0.0713 | 0.7077 | 0.4000 |

| adam | tanh | 0.5558 | 0.0696 | 0.6923 | 0.4000 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adam | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.9038 | 0.0271 | 0.9434 | 0.8396 |

| adam | relu | 0.8983 | 0.0354 | 0.9623 | 0.8302 |

| rmsprop | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.8965 | 0.0296 | 0.9340 | 0.8302 |

| adadelta | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.8936 | 0.0324 | 0.9434 | 0.8208 |

| rmsprop | relu | 0.8899 | 0.0395 | 0.9528 | 0.8113 |

| adadelta | relu | 0.8849 | 0.0494 | 0.9623 | 0.7547 |

| sgd | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.8686 | 0.0317 | 0.9151 | 0.8019 |

| adam | tanh | 0.8642 | 0.0346 | 0.9340 | 0.7925 |

| rmsprop | tanh | 0.8434 | 0.0415 | 0.9151 | 0.7736 |

| adam | decaying_cosine | 0.8413 | 0.0336 | 0.9057 | 0.7642 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adadelta | decaying_cosine | 0.9306 | 0.0376 | 0.9778 | 0.8444 |

| rmsprop | decaying_cosine | 0.9272 | 0.0372 | 0.9778 | 0.8222 |

| adam | decaying_cosine | 0.9256 | 0.0420 | 1.0000 | 0.8000 |

| sgd | relu | 0.9039 | 0.0675 | 1.0000 | 0.7333 |

| adagrad | relu | 0.8700 | 0.1242 | 1.0000 | 0.4889 |

| adam | relu | 0.8694 | 0.0737 | 1.0000 | 0.6667 |

| adadelta | relu | 0.8667 | 0.0790 | 1.0000 | 0.6444 |

| adadelta | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xpsin | 0.8656 | 0.0502 | 1.0000 | 0.7778 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xpsin | 0.8606 | 0.0494 | 0.9556 | 0.7556 |

| rmsprop | relu | 0.8594 | 0.0738 | 0.9778 | 0.6667 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adadelta | decaying_cosine | 0.8933 | 0.0406 | 0.9683 | 0.7937 |

| rmsprop | decaying_cosine | 0.8897 | 0.0405 | 0.9524 | 0.7937 |

| adam | decaying_cosine | 0.8893 | 0.0330 | 0.9524 | 0.8254 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_tanhpsin | 0.8885 | 0.0399 | 0.9683 | 0.8095 |

| adadelta | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xpsin | 0.8853 | 0.0424 | 0.9683 | 0.7937 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xpsin | 0.8841 | 0.0378 | 0.9524 | 0.8095 |

| adadelta | weierstrass_mandelbrot_tanhpsin | 0.8750 | 0.0399 | 0.9524 | 0.7937 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_xsinsquared | 0.8730 | 0.0478 | 0.9365 | 0.7302 |

| sgd | tanh | 0.8730 | 0.0517 | 0.9524 | 0.7619 |

| rmsprop | weierstrass_mandelbrot_relupsin | 0.8687 | 0.0344 | 0.9365 | 0.7619 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adagrad | relu | 0.8083 | 0.0344 | 0.8646 | 0.7153 |

| adagrad | tanh | 0.7616 | 0.0508 | 0.8542 | 0.6319 |

| adagrad | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7547 | 0.0899 | 0.8611 | 0.4444 |

| adadelta | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7545 | 0.0256 | 0.8264 | 0.7153 |

| adam | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7503 | 0.0253 | 0.8056 | 0.7083 |

| adam | relu | 0.7500 | 0.0277 | 0.8090 | 0.7083 |

| rmsprop | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7498 | 0.0263 | 0.8125 | 0.6979 |

| adadelta | relu | 0.7443 | 0.0257 | 0.8160 | 0.7049 |

| rmsprop | relu | 0.7400 | 0.0257 | 0.8021 | 0.7049 |

| adagrad | sigmoid | 0.7237 | 0.0261 | 0.7917 | 0.6736 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adam | relu | 0.7973 | 0.0281 | 0.8543 | 0.7205 |

| rmsprop | relu | 0.7957 | 0.0304 | 0.8583 | 0.7244 |

| adadelta | relu | 0.7912 | 0.0293 | 0.8504 | 0.7362 |

| sgd | relu | 0.7857 | 0.0256 | 0.8425 | 0.7323 |

| adam | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7685 | 0.0304 | 0.8268 | 0.6969 |

| rmsprop | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7633 | 0.0330 | 0.8150 | 0.6614 |

| adadelta | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.7582 | 0.0286 | 0.8386 | 0.7008 |

| adam | tanh | 0.7541 | 0.0281 | 0.8110 | 0.6969 |

| adadelta | tanh | 0.7511 | 0.0309 | 0.8071 | 0.6890 |

| rmsprop | tanh | 0.7455 | 0.0374 | 0.8031 | 0.6575 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sgd | tanh | 0.8376 | 0.0310 | 0.9032 | 0.7742 |

| adadelta | tanh | 0.8215 | 0.0393 | 0.8817 | 0.7204 |

| adadelta | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.8185 | 0.0359 | 0.8817 | 0.7312 |

| adam | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.8172 | 0.0345 | 0.8710 | 0.7527 |

| rmsprop | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.8172 | 0.0348 | 0.8710 | 0.7527 |

| adam | tanh | 0.8156 | 0.0428 | 0.8925 | 0.7204 |

| rmsprop | tanh | 0.8142 | 0.0409 | 0.8925 | 0.7204 |

| rmsprop | relu | 0.8086 | 0.0406 | 0.8817 | 0.7204 |

| adadelta | relu | 0.8081 | 0.0416 | 0.8817 | 0.7097 |

| adam | relu | 0.8073 | 0.0438 | 0.8817 | 0.6882 |

| Optimizer | Activation | Mean | Std | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adam | blancmange | 0.9528 | 0.0275 | 1.0000 | 0.8889 |

| rmsprop | blancmange | 0.9500 | 0.0344 | 1.0000 | 0.8333 |

| adadelta | blancmange | 0.9472 | 0.0330 | 1.0000 | 0.8704 |

| adam | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.9463 | 0.0271 | 1.0000 | 0.8889 |

| adadelta | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.9431 | 0.0276 | 0.9815 | 0.8889 |

| rmsprop | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.9417 | 0.0378 | 1.0000 | 0.8148 |

| sgd | relu | 0.9384 | 0.0454 | 1.0000 | 0.8333 |

| adadelta | relu | 0.9352 | 0.0478 | 1.0000 | 0.8148 |

| adam | relu | 0.9343 | 0.0490 | 1.0000 | 0.7963 |

| sgd | modified_weierstrass_tanh | 0.9315 | 0.0408 | 1.0000 | 0.8333 |

| Activation function |

arc-len |

arc-len |

Activation function |

arc-len |

arc-len |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| relu | weierstrass mandelbrot relupsin |

||||

| tanh | weierstrass mandelbrot tanhpsin |

||||

| sigmoid | blancmange | ||||

| weierstrass | decaying cosine |

||||

| weierstrass mandelbrot xpsin |

modified weierstrass tanh |

||||

| weierstrass mandelbrot xsinsquared |

modified weierstrass ReLU |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).