1. Introduction

Immersive technologies such as virtual reality (VR) rhythm games (e.g.,

Beat Saber [

2] and

Supernatural [

18]) demonstrate that bodily movement can be powerfully entwined with sound. Yet VR isolates users from the physical context that often inspires music making. Recent advances in room-scale scene mapping and marker-less hand tracking on devices like Meta Quest 3 open an opportunity to situate musical interactions directly within users’ everyday environments.

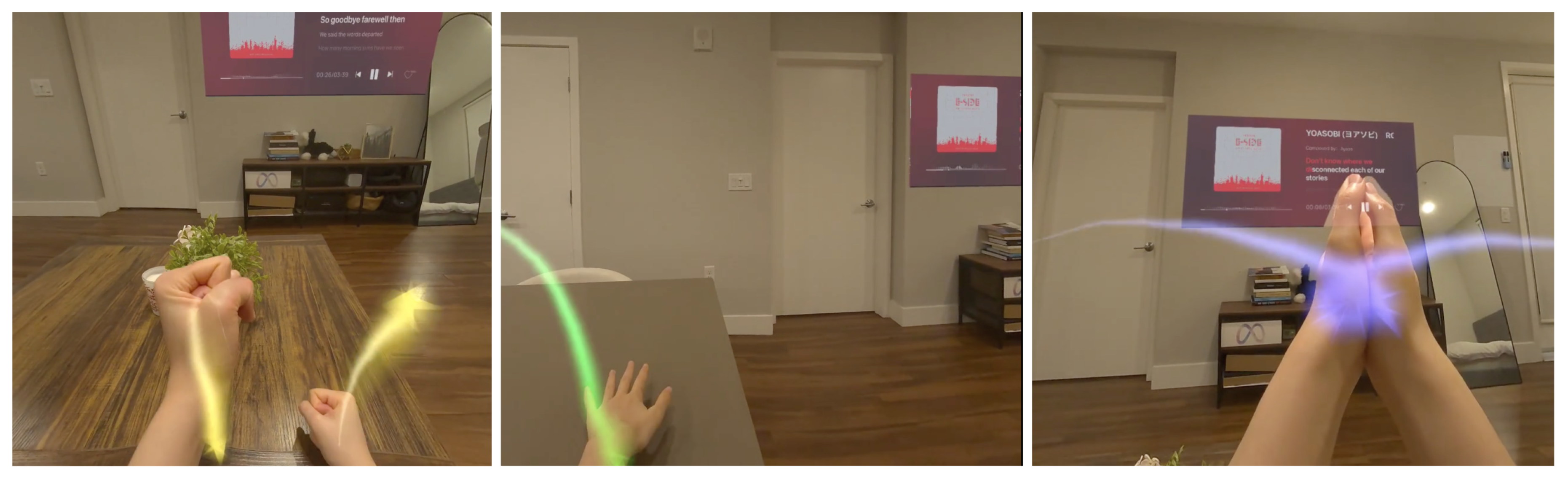

This paper presents a novel AR music application developed for the Meta Quest 3 that integrates spatial scene understanding with real-time hand gesture recognition. The headset’s scene-understanding subsystem continuously reconstructs a semantic mesh of physical objects—such as tables, beds, and walls—so that users can strike those surfaces to trigger sound. Simultaneously, on-device hand tracking detects collisions and measures fingertip–palm and inter-hand distances to distinguish taps, punches, and claps. Each gesture–surface pair produces immediate audio feedback (e.g., drum-crash, kick drum, clap), allowing performers to “play" their surroundings (

Figure 1). A video demonstration is available at

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1hsBnGtLe18VTOSytthU6lppdsWV0b0Wu/view.

We introduce SAGeM, a scene-aware AR framework that turns walls, tables, and even sofas into percussive controllers, enabling “room-as-instrument" performance. Our contributions are threefold:

A software architecture that fuses Meta’s real-time scene mesh with a lightweight gesture recogniser at <20 ms median latency.

A set of intuitive surface-linked gestures (tap, punch, clap) that map bodily motion to percussion.

An initial empirical evaluation demonstrating technical viability and positive user reception.

2. Related Work

2.1. Embodied and Interactive Music in AR/VR

Early VR rhythm titles such as

Beat Saber [

2],

Supernatural [

18], and

SoundStage VR [

3] demonstrated that whole-body gestures can be tightly coupled to musical feedback, but they isolate performers from their physical surroundings. Several AR prototypes attempt to re-embed music in real space—for example,

AR Pianist overlays virtual notes on a real piano keyboard [

19], while

HoloDrums gives users volumetric drum pads in mixed reality [

6]. These systems, however, either rely on marker-based alignment or support only a small set of predefined instruments. Our work differs by treating the room itself as a dynamically mapped instrument whose surfaces acquire sonic affordances on-the-fly.

2.2. Scene Understanding and Spatial Mapping

Current head-mounted displays (HMDs) reconstruct dense meshes with semantic labels in real time [

4,

5]. Researchers have leveraged such meshes for spatial storytelling [

7], context-aware widgets [

12], and safety boundaries in VR games [

11]. Few studies, however, pair scene semantics with audio interaction.

Tangible AR Sound laid early groundwork by placing virtual strings on planar surfaces [

10], but lacked per-surface classification or hand-tracking precision. SAGeM extends this line by fusing per-triangle collisions with semantic tags (e.g., “wall,” “table”) to yield context-sensitive timbres.

2.3. Hand and Gesture Interaction for XR

Markerless hand tracking has advanced to sub-10 mm accuracy at 60–120 Hz on commodity HMDs [

13,

14]. Gesture sets for mid-air AR input typically centre on pinching and pointing, optimised for UI control [

16]. In sonic contexts, prior work explored air-guitar chords [

15] and mid-air DJ knobs [

17], but required external cameras or fiducials. Our classifier uses only on-device hand poses plus surface-aware collisions, enabling robust, low-latency recognition of tap, punch, and clap even when hands occlude each other.

3. System Overview

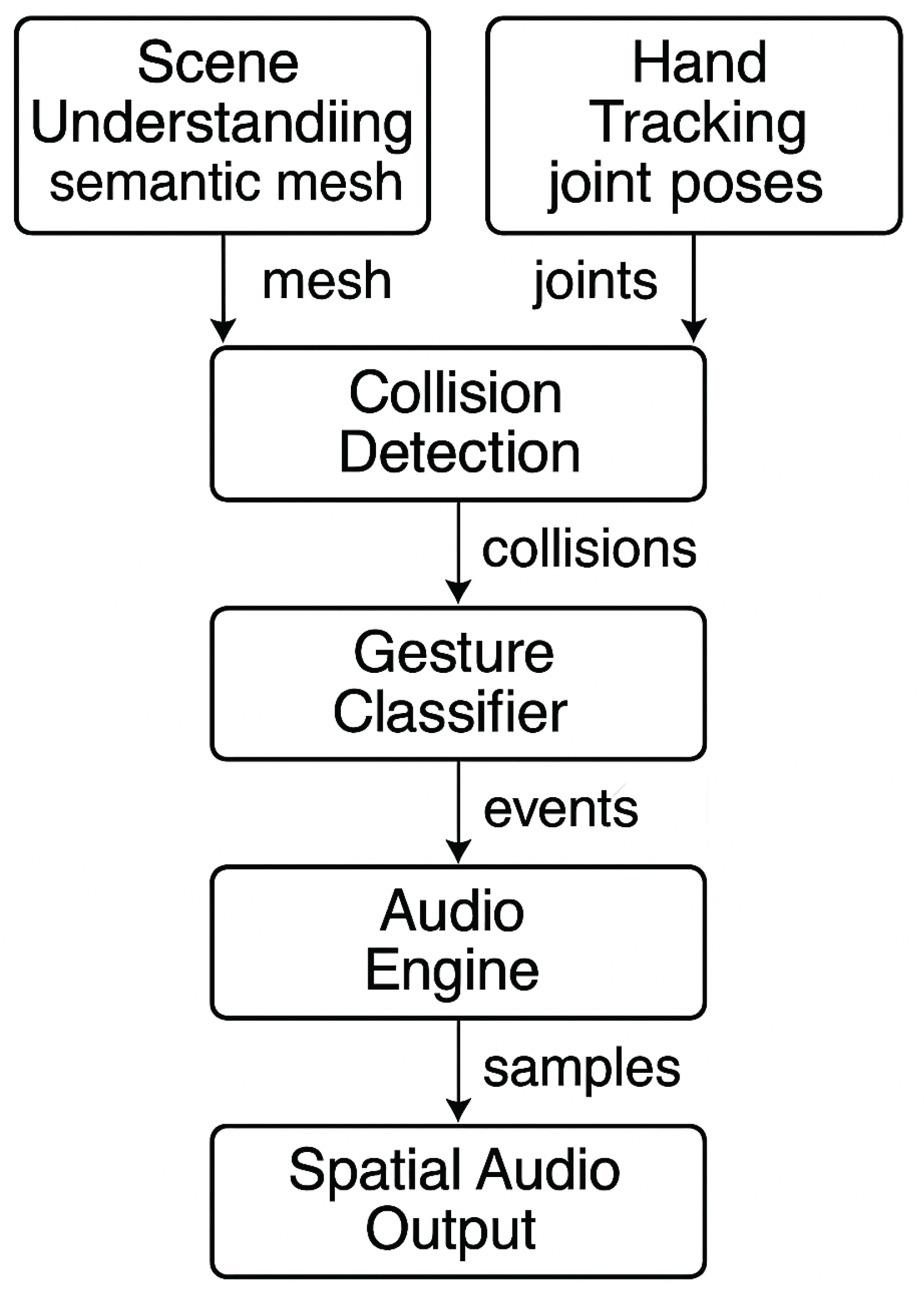

Figure 2 presents the five-stage dataflow that drives

SAGeM:

Scene Mesh Acquisition & Labelling. A background thread polls the Meta XR SDK at 30 Hz, retrieving the raw triangle mesh of the room. The headset’s on-device semantic segmentation service then attaches class labels (

plane,

table,

wall, …) to each vertex. The labelled mesh is cached in a spatial hash so surface look-ups during collision tests are

. Beyond semantic labels, automated image-derived texture metrics (e.g., roughness) can be attached to mesh elements using methods like Lu et al., enabling timbre choices that reflect surface character [

8].

Hand Pose Streaming. Unity’s Hand Interaction API delivers a 21-joint pose for each hand at 60 Hz. We apply a 5-sample exponential moving average to damp jitter while preserving responsiveness.

GPU-Accelerated Collision Detection. Palm and fingertip colliders are sent to an HLSL compute shader that intersects them with the semantic mesh every frame (budget: 2 ms). Each hit yields a contact record .

Gesture Classification. A finite-state machine buffers contact records in a 200 ms sliding window and classifies the interaction as a tap, punch, or clap using features such as fingertip–palm distance, inter-hand distance, contact impulse, and duration.

Audio Rendering. The Audio Engine receives the classified event, selects one of 24 pre-buffered percussion samples based on the surface label and gesture, applies distance-based attenuation, and spatialises the sound with the Quest 3 spatialiser. The median end-to-end latency from physical impact to audible onset is 19 ms (90th percentile = 24 ms).

4. Technical Implementation

Collision Detection.

Each hand carries two kinematic rigid-body colliders: a 4-cm sphere centred on the palm and a 1.2-cm capsule covering all five fingertips. Per-frame collision tests are off-loaded to a compute shader that projects collider vertices into the decimated scene mesh (∼15k triangles) stored in a structured buffer. The kernel runs in parallel across 256 threads, completes in 1.7 ms (average), and emits a contact record . CPU involvement is limited to dispatching the shader and reading back a 64-byte result buffer.

Gesture Classification.

A lightweight three-state finite-state machine (FSM) operates on a 200 ms sliding window. Features include: fingertip–palm distance, inter-hand distance, collision impulse, and contact duration. Thresholds were tuned via grid search on a 1 200-frame labelled dataset collected from six pilot users. The resulting model attains

96.3 % accuracy (macro-F

1 =0.95). The FSM requires 0.02 ms per frame on the CPU—negligible in the overall budget. As we migrate from a finite-state machine to a lightweight neural classifier, Luo et al.’s TR-PTS (task-relevant parameter and token selection) enables on-device fine-tuning within our latency and memory budgets [

9].

Audio Engine.

Twenty-four percussion samples (44.1 kHz, 16-bit PCM) are pre-buffered into FMOD’s Sample Data heap at app launch (12 MB total). For each gesture event the engine:

selects a sample from a 3 × 3 lookup table (gesture × surface tag),

applies distance-based attenuation and an exponential roll-off above 4 kHz for far-field hits,

routes the signal through FMOD’s built-in 3-D panner.

A ring buffer timestamps every gesture and corresponding

playSound() call; profiling across 1 000 events yields a median

end-to-end latency of 19 ms (90th percentile = 24 ms), well below the 50 ms threshold for perceived immediacy in musical interaction [

1].

5. Evaluation

5.1. Performance Benchmark

We profiled end-to-end latency across 1,000 events, measuring a median of 19 ms and 90th-percentile of 24 ms. CPU usage remained below 18% on average.

5.2. User Study

Eight participants (4 novice, 4 musically trained, 2 female, ages 22–35) performed a free improvisation task for 10 minutes each. System Usability Scale (SUS) averaged 82.1 (sd = 6.4). Participants highlighted the immediacy of feedback and the novelty of “playing furniture.”

Table 1.

Participant demographics (N=8).

Table 1.

Participant demographics (N=8).

| Attribute |

Count |

Percentage |

| Experience: Novice |

4 |

50% |

| Experience: Musically trained |

4 |

50% |

| Gender: Female |

2 |

25% |

| Gender: Male |

6 |

75% |

| Age Range |

22–35 |

| Task Duration |

10 min each |

Participants were grouped by self-reported musical background: novice (little or no formal training and only casual music making) and musically trained (at least three years of instruction or regular performance). This stratification lets us examine whether prior musical expertise influences interaction quality.

The System Usability Scale is a ten-item questionnaire that yields a single score from 0 (“poor”) to 100 (“excellent”). A value of 68 is commonly considered the benchmark for “average” usability, whereas scores above 80 typically fall in the “excellent” range. The mean score of 82.1 therefore indicates that participants rated SAGeM as highly usable.

Table 2.

System Usability Scale (SUS) results.

Table 2.

System Usability Scale (SUS) results.

| Metric |

Value |

| Mean SUS |

82.1 |

| Standard Deviation |

6.4 |

6. Future Works

To enhance the AR music application’s immersive experience, several improvements are planned. First, refine audio responses based on surface interactions (e.g., beds, tables, couches, walls), each producing distinct sounds to enrich engagement. Second, enable real-time environmental analysis, allowing adaptive responses to movement, such as walking or running, for seamless integration into dynamic real-world scenarios. Finally, implement a segmented musical structure, dynamically adjusting background music by lowering volume or removing elements like drums or bass. User interactions can then introduce or modify these elements, enabling interactive composition through gestures.

7. Discussion

Participants often described the experience with metaphors such as “my room became a drum kit” and “I felt like I was literally playing the furniture,” underscoring a strong sense of spatial embodiment. Despite this enthusiasm, two technical limitations emerged:

Mesh quality under adverse lighting. Low-lux scenes and highly reflective surfaces (glass coffee tables, stainless-steel appliances) impaired the Quest 3 depth estimator, producing sparse or jittery triangles. Roughly 7 % of collision attempts in those zones failed to register, breaking rhythmic flow.

Static timbre mapping. Each gesture–surface pair was hard-coded to a single percussion sample. Several players wanted softer dynamics when striking cushions and sharper attacks on stone countertops, suggesting a need for context-adaptive timbre.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

We introduced SAGeM, a scene-aware AR music application that instantly turns the physical environment into a percussive instrument. Our technical pipeline achieves 19 ms median input-to-sound latency, 96.3 % gesture-classification accuracy, and sustains real-time performance entirely on-device. An eight-person user study yielded a mean System Usability Scale score of 82.1—well inside the “excellent” bracket—and qualitative metaphors such as “my room became a drum kit,” pointing to deep spatial embodiment and creative engagement.

Limitations.

Performance degrades in extremely low-lux or highly reflective environments, leading to occasional missed collisions. Timbre mapping is currently discrete and pre-recorded, limiting dynamic range and expressiveness.

Future Directions.

We see three immediate avenues for expansion:

Collaborative Jamming. Networking multiple headsets so performers can share the same semantic mesh and hear one another’s actions with sub-30 ms end-to-end latency.

Adaptive Accompaniment. Integrating real-time beat-tracking and generative rhythm models so the system can layer autonomous grooves that react to user timing and dynamics.

Broader Gesture Vocabulary. Employing lightweight neural classifiers to recognise continuous hand-surface interactions (e.g. slides, rolls, scrapes) and modulate synthesis parameters for richer timbre.

Longer term, we envision SAGeM as a platform for mixed-reality composition classes, therapeutic motor-skill training, and public installations where entire rooms become communal instruments. By bridging semantic perception and embodied audio feedback, our work pushes AR toward genuinely spatial musical interaction and opens a fruitful design space for future research and creative practice.

References

- Dahl, L. Dahl, L., Wang, G.: Latency and the performer: How much is too much? In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME). pp. 173–177. Goldsmiths, University of London, London, United Kingdom (2014), https://www.nime.org/proceedings/2014/nime2014_173.pdf.

- Games, B.: Beat saber (2018), https://beatsaber.com/, version x.x, VR rhythm game, Meta Quest, PCVR, PSVR.

- Heuer, J., Wu, G.: Soundstage vr: Immersive studio production in virtual reality. In: Proceedings of the 2017 New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME). p. TBD. NIME (2017).

- Inc., A.: Roomplan: Room-scanning api for ios 17. https://developer.apple.com/documentation/roomplan (2023), accessed 15 Jun 2025.

- Inc., M.P.: Meta xr all-in-one sdk v66: Developer documentation (2024).

- Lee, S., Park, E., Choi, J.: Holodrums: Volumetric drum pads in mixed reality. In: Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces (AVI). p. TBD (2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, C., et al.: Storymaker: Context-aware ar storytelling. In: Proceedings of ACM UIST (2021).

- Lu, B., Dan, H.C., Zhang, Y., Huang, Z.: Journey into automation: Image-derived pavement texture extraction and evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.02414 (2025).

- Luo, S., Yang, H., Xin, Y., Yi, M., Wu, G., Zhai, G., Liu, X.: Tr-pts: Task-relevant parameter and token selection for efficient tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.22872 (2025).

- Mulloni, A., et al.: Indoor navigation with mixed reality world in miniature. In: Proceedings of ISMAR (2010).

- Nie, X., Li, J., Fuchs, H.: Guardian ghost: Dynamic scene-aware safety boundaries for vr. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR). p. TBD (2021). [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y., et al.: Contextual uis on scene-aware head-mounted displays. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (TVCG) (2023).

- Research, G.: Mediapipe hands: Real-time hand tracking on mobile. https://google.github.io/mediapipe/solutions/hands (2020), accessed 15 Jun 2025.

- Rogers, K., et al.: Low-latency hand tracking for mobile vr/ar. In: Proceedings of IEEE ISMAR (2019).

- Schofield, N., Mitchell, T.: Airguitar++: Real-time mid-air guitar chord recognition using hand tracking. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME). p. TBD (2021).

- Sra, M., Maes, P.: Handuis: Designing mid-air hand-tracking interfaces for head-worn ar. In: Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST). p. TBD (2022). [CrossRef]

- n, Y., Liu, C., Wang, W.: Airdj: Mid-air turntables for interactive dj performance. In: Proceedings of the ACM Multimedia Conference (MM). p. TBD (2020). [CrossRef]

- Within Unlimited, I.: Supernatural (2020), https://www.getsupernatural.com/, vR fitness app, Meta Quest.

- Yang, K., Chiu, Y., Liu, Y.: Ar pianist: Augmented reality sight reading on a physical piano. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR). p. TBD (2019). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).