1. Introduction

Hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) diseases such as hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and complex benign conditions often require high-stakes surgical intervention. Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of curative treatment for many of these diseases, but HPB operations are among the most challenging in abdominal surgery due to intricate anatomy, critical vasculature, and narrow margins for error. Even in experienced centers, outcomes like negative resection margins, complication rates, and long-term survival are closely tied to the quality of preoperative imaging, the surgeon

’s planning, and real-time intraoperative judgment [

1]. In recent years, HPB surgery has also trended toward minimally invasive approaches (laparoscopic and robotic surgery) to improve recovery, although these techniques demand even greater precision and visualization given the reduced tactile feedback and view [

2].

Artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly advanced in medicine and offers powerful tools to address some of these needs. AI – particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning algorithms – excels at detecting patterns in complex data, often surpassing human performance in tasks like image recognition. In the domain of medical imaging, AI applications have grown exponentially; a recent bibliometric analysis identified 2,552 publications on AI in HPB surgery from 2014 to 2024, with

“diagnosis” and

“CT” among the most frequent keywords [

3]. This reflects a contemporary research focus on using AI for disease detection and characterization in imaging, especially for liver and pancreatic tumors. Indeed, AI-driven image analysis can potentially identify subtle features on radiologic scans or intraoperative ultrasound that might be missed by the human eye, or predict tumor behavior (such as malignancy or likelihood of recurrence) from quantitative patterns (

“radiomics”). Beyond preoperative imaging, AI techniques are being explored for patient risk stratification (e.g. predicting postoperative complications), operative planning (e.g. automated 3D reconstructions and virtual simulations), and intraoperative guidance (e.g. augmented reality overlays and real-time video analysis) [

4]. The breadth of

“digital tools” thus encompasses not only AI/ML algorithms but also computer vision, sensor fusion, and enhanced reality systems – all aiming to support surgical decision-making from start to finish [

5,

6].

Early results specific to HPB surgery are encouraging. For instance, multiple studies have shown that ML models can predict postoperative pancreatic fistula more accurately than traditional surgeon-calculated scores [

7,

8]. On the imaging front, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been trained to detect liver tumors or differentiate pancreatic lesions on scans with high sensitivity – in some cases identifying tumors months earlier than standard diagnostics [

9,

10]. In the operating room, augmented reality (AR) systems have been piloted to project virtual anatomy onto the surgical field to help surgeons navigate internal structures [

11,

12,

13] . Computer vision algorithms can process laparoscopic video in real time; for example, by recognizing unsafe tissue planes or early signs of bleeding and alerting the team, allowing proactive intervention [

14]. These developments align with the broader trend of

“smart surgery,” wherein digital technology acts as a co-pilot to the surgeon.

Despite growing interest and a proliferation of pilot studies, there remains a gap before these innovations are widely adopted in clinical practice. Most AI tools in HPB surgery are still in the developmental or experimental stage, tested on retrospective datasets or small case series. Validation in prospective clinical trials is needed for regulatory approval and to build clinical confidence. Surgeons must also be able to trust and seamlessly interact with these systems during real operations. Additionally, issues of integration (how to incorporate AI outputs into surgical workflows), regulation, and ethics (such as liability and transparency of AI decision-making) need to be addressed. Given the rapid pace of new data, a timely systematic review is warranted to synthesize the current evidence, evaluate study quality, and guide clinicians and researchers on future directions of AI in HPB surgery. Herein, we present a comprehensive systematic review of AI and digital tools in HPB surgery, adhering to PRISMA 2020 guidelines, and discuss the clinical advances and challenges in this emerging field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. The review protocol (objectives, search strategy, inclusion criteria, and analysis methods) was formulated prior to commencing study selection. The protocol was not registered in a public database; however, all methods followed PRISMA recommendations for transparent reporting [

15].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We included studies of any design (retrospective or prospective clinical studies, case series, or technical feasibility studies) that evaluated an AI-driven or digital tool in the context of HPB surgical care. Specifically, studies were eligible if they involved an application of AI, machine learning (including deep learning), computer vision, augmented or mixed reality, or related digital navigation tools in any phase of HPB surgery: preoperative imaging interpretation, surgical planning or simulation, intraoperative guidance or decision support, or postoperative outcome prediction relevant to HPB diseases. We included both liver and pancreatic surgery applications (and biliary surgery where applicable), with no restrictions on disease type (malignant or benign) as long as a surgical context was present. Only articles in English were included. We excluded conference abstracts lacking full data, editorials/commentaries, and purely animal or phantom model studies without any intended clinical translation, while mining the references of review articles. If multiple papers reported on the same cohort or AI tool, we included the most comprehensive or latest report to avoid duplicate data. Both peer-reviewed journal articles and relevant high-quality preprints were considered if they contained sufficient methodology and results.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in four databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus. We also searched engineering and specialty databases – IEEE Xplore and ACM Digital Library – for relevant technical papers on surgical navigation or AR that might not be indexed in the medical databases. Additionally, the Cochrane Library was searched for any pertinent systematic reviews. The search was first performed in May 2025 and updated in June 2025 to capture newly published studies.

The search strategy combined keywords and controlled vocabulary terms related to two domains: (1) HPB surgery (e.g. “hepato-pancreato-biliary” OR “HPB” OR “liver surgery” OR “hepatectomy” OR “pancreatic surgery” OR “Whipple” OR “bile duct surgery”, etc.) and (2) Artificial Intelligence/Digital Tools (e.g. “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural network” OR “radiomics” OR “augmented reality” OR “mixed reality” OR “surgical navigation” OR “image-guided surgery” OR “3D reconstruction” OR “robotic surgery” OR “decision support” OR “predictive model”, etc.).

These were combined with Boolean operators AND/OR. A sample PubMed query was:

(("hepato-pancreato-biliary" OR HPB OR hepatobiliary OR pancreatic OR pancreatoduodenectomy OR hepatectomy OR "liver resection" OR "pancreatic resection”)

AND

("artificial intelligence" OR "machine learning" OR "deep learning" OR radiomics OR "augmented reality" OR "mixed reality" OR "image-guided" OR navigation OR "3D planning" OR "3D reconstruction" OR robotic OR "decision support" OR "predictive model"))

AND 2018:2023[dp] AND english[lang].

Similar queries were adapted for the other databases. We also hand-searched reference lists of relevant articles and conference proceedings to ensure completeness. No date restrictions were imposed initially, but practically most retrieved studies were from the last decade given the nascent nature of AI in surgery.

2.4. Study Selection

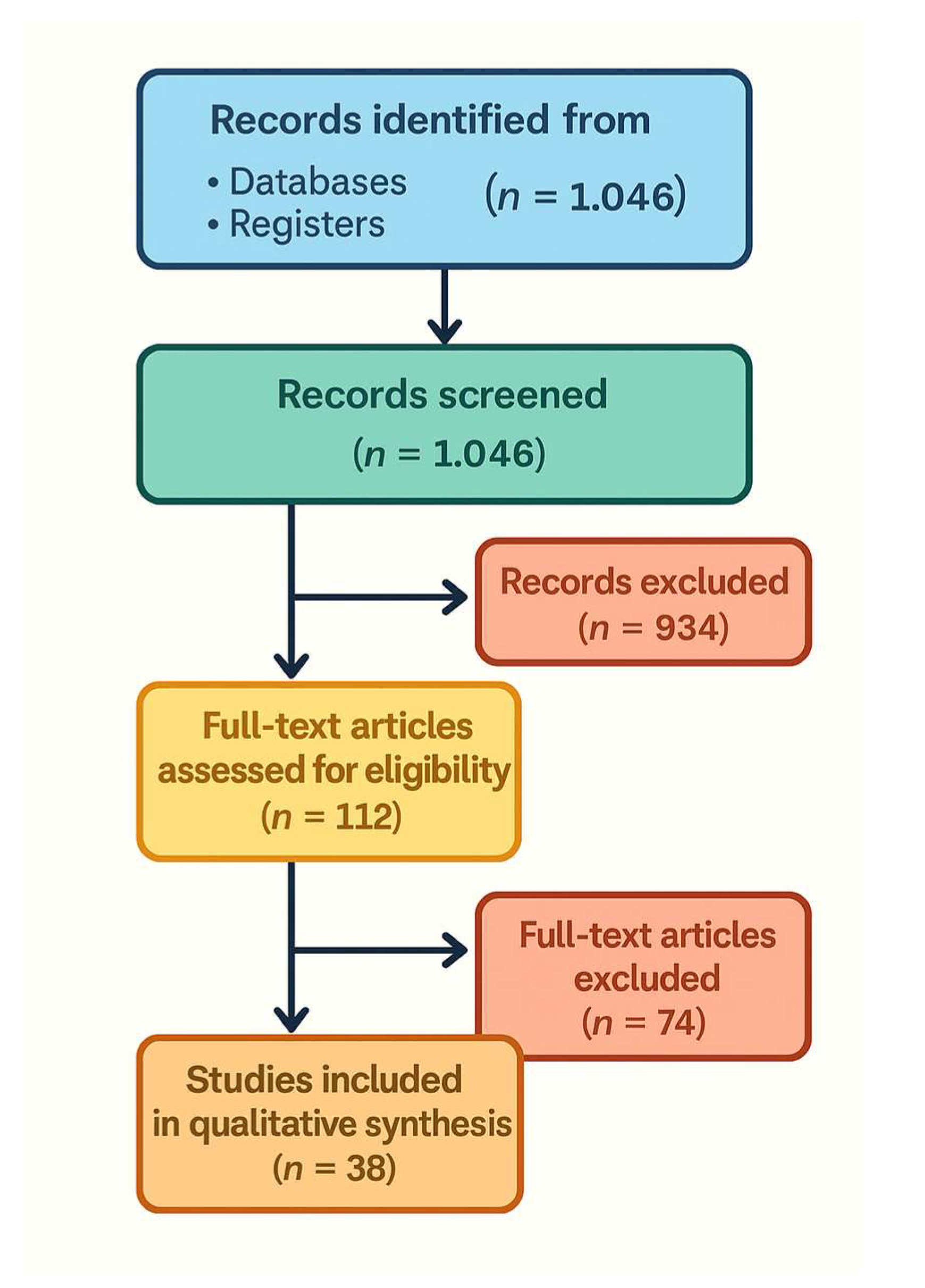

All identified records were imported into a reference manager, and duplicates were removed. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance. Studies deemed potentially eligible or unclear were retrieved in full text. The same two reviewers then independently evaluated full-text articles against the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus, involving a third reviewer if needed. A PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1) details the number of records identified, screened, excluded, and finally included. The most common reasons for exclusion at full text were absence of any AI/digital tool specific to HPB surgery (e.g. purely diagnostic radiology studies without surgical context), non-clinical studies (e.g. algorithm papers with no clinical validation), or outcomes not relevant to surgical planning or outcomes.

2.5. Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data using a standardized form. From each included study, we collected: author, year, study design (retrospective, prospective, etc.), sample size and population (e.g. number of patients or images, disease focus like HCC or PDAC), type of AI or digital tool (including details of algorithms or platforms), the application domain (imaging diagnosis, risk prediction, planning, intraoperative guidance, etc.), and key outcomes or findings. For prediction model studies, we noted performance metrics like AUC, sensitivity, specificity, etc. For AR/ navigation tools, we noted qualitative and quantitative outcomes such as registration error, time saved, or user feedback on usefulness. Any additional notable findings (e.g. technical challenges) were also recorded. The two extractors compared their results and resolved discrepancies by consensus.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

We assessed methodological quality and risk of bias using appropriate tools for each study design. For prediction model studies (e.g. algorithms to predict postoperative complications or recurrence), we used the Prediction Model Risk of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) [

16]. This evaluates bias across four domains (participants, predictors, outcome, analysis), rating each as low, high, or unclear risk of bias. For diagnostic accuracy studies of AI in imaging, we applied criteria based on QUADAS-2 to judge bias in patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow/timing [

17]. For exploratory/feasibility studies of intraoperative tools where formal checklists didn

’t directly apply, we qualitatively considered factors such as highly selective samples or lack of appropriate comparator. Two reviewers performed the quality assessments independently, and disagreements were resolved by discussion. We incorporated risk-of-bias findings into our interpretation of results, giving more weight to findings from higher-quality studies. Overall, many included studies had at least some risk of bias (often due to retrospective designs or single-center data); these limitations are noted in our discussion.

2.7. Data Synthesis

Given heterogeneity of interventions and outcome metrics, a meta-analysis was not feasible. We therefore conducted a narrative synthesis organized by major application domains of AI/ digital tools in HPB surgery. We grouped results into categories corresponding to stages of surgical care:

- (1)

Preoperative Imaging and Diagnosis

- (2)

Risk Prediction (outcomes)

- (3)

Surgical Planning and Simulation

- (4)

Intraoperative Guidance and Navigation

- (5)

Surgical Video Analysis/Robotics

Within each category, we summarize the performance of AI tools and any reported impact on clinical decision-making or patient outcomes. We also tabulated key characteristics of representative studies for clarity

(Table 1). Where appropriate, we compare AI tool performance to conventional standards (e.g. AI vs human radiologist, or vs existing risk scores). All analyses are descriptive; no pooled summary measures were calculated due to diverse data. Instead, we highlight trends, such as areas where multiple studies consistently show benefit versus areas of conflicting or limited evidence.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

The database search yielded 1,046 unique records. After title/abstract screening, 112 articles remained for full-text review. Of these, 38 studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis

(Figure 1). The PRISMA flow diagram

(Figure 1) illustrates the study selection process and reasons for exclusion. The included studies span publication years 2017–2025 (with a majority in 2020– 2025, reflecting the rapid growth of this field) and originate from a range of countries (notably the United States, China, several European countries, and Japan). Study designs were predominantly retrospective observational studies or feasibility pilots; a few prospective studies were identified, but no multicenter randomized trials of AI interventions in HPB surgery were found at the time of our search.

3.2. Preoperative AI and 3D Planning (Imaging and Diagnosis)

Several studies applied AI to interpret preoperative imaging for HPB diseases – such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and MRI – with the aim of improving diagnostic accuracy.

Machine learning for tumor detection and characterization: In liver imaging, AI algorithms (often CNNs) have shown high accuracy in identifying liver tumors and classifying lesion types. For example, one study combined radiomics features with a CNN to differentiate hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from liver metastases on ultrasound images, achieving AUC ~0.85–0.90 [

4]. In another, a deep learning model (ResNet-50) trained on endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) images distinguished pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) from chronic pancreatitis with an AUC of 0.95 [

18] . These accuracies are on par with, or exceeding, expert radiologist performance in these tasks. A recent systematic review of AI in liver imaging noted that most algorithms focus on lesion classification (particularly on CT scans) and report high internal accuracies, but a common limitation is lack of external validation [

24] – suggesting potential optimism bias in those results.

Beyond simply detecting lesions, AI has been used to

predict tumor biology or staging from preoperative scans. For instance, radiomic models analyzing preoperative CT have shown ability to predict early HCC recurrence after resection better than conventional clinical staging, by identifying subtle textural features associated with tumor aggressiveness [

26]. In pancreatic cancer, one model automatically quantified vascular involvement on CT to classify tumors as resectable vs. locally advanced unresectable, with high agreement to expert assessments [

27]. Tools like this could aid surgical decision-making by more objectively staging tumors preoperatively (e.g., determining which patients should go straight to surgery vs. need neoadjuvant therapy).

Some digital tools also bridge into

intraoperative imaging enhancement. For example, an experimental system used an AI algorithm to register real-time intraoperative ultrasound with preoperative CTimages [

28]. This kind of image fusion could improve the surgeon

’s ability to locate tumors during laparoscopic ultrasound by correlating it with pre-op imaging. In summary, AI in preoperative imaging has shown high diagnostic performance in identifying and characterizing HPB tumors. The challenge ahead lies in translating these algorithms into clinical workflows and ensuring they maintain accuracy in the real-world setting. As noted in the literature, prospective validation is needed: e.g., Bektas et al. (2024) concluded that while ultrasound-based AI models showed AUCs up to 0.98 in differentiating tissue types, prospective studies are required to confirm consistent performance externally [

4] .

In parallel, advanced 3D imaging and visualization tools are augmenting preoperative planning.

Automated 3D reconstruction: Several studies highlighted the use of AI to perform 3D reconstructions of liver and pancreatic anatomy from CT/MRI scans. This includes segmenting the liver into anatomical units and delineating tumors, vessels, and ducts [

29,

30]. Historically, creating patient-specific 3D models was time-consuming (often requiring hours of manual work by radiologists). AI-based image segmentation significantly accelerates this. For example, a deep learning algorithm in one study reduced liver 3D model processing time by ~94% compared to manual methods. Rapid model generation makes it feasible to use 3D visualization for every complex case. Surgeons can then virtually plan their resections – determining optimal resection planes, estimating future liver remnant volume, and even rehearsing the surgery on a computer [

31,

32]. One recent randomized study even incorporated 3D-printed models: Li et al. (2025) reported that using AI-assisted 3D printed liver models for surgical planning led to significantly less intraoperative blood loss compared to standard planning without such models. This suggests that enhanced planning can translate to improved intraoperative outcomes [

33].

Augmented and mixed reality for planning: In addition to screen-based 3D models, some teams have explored using augmented reality (AR) or mixed reality to aid preoperative planning. For instance, holographic visualization of patient anatomy via AR headsets has been tested as a planning tool. In a pilot study for pancreatic tumor resection using mixed reality, surgeons could visualize major arteries and veins holographically in 3D prior to surgery, which reportedly improved their confidence in dissection around those structures (though quantitative outcomes were not yet measured)[

34,

35].

These technologies blur the line between preoperative planning and intraoperative guidance, as the same AR models can potentially be brought into the OR (see below).

3.3. Predictive Analytics (AI for Risk and Outcome Prediction)

Another major application of AI in HPB surgery is prediction of operative risk and postoperative outcomes. These AI-driven predictive analytics models use preoperative or intraoperative data to forecast complications and aid in risk stratification and clinical decision-making.

Postoperative complication risk models: A prototypical example is predicting postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF), one of the most common and feared complications after pancreatic resection. Traditional risk scores (like the Fistula Risk Score, FRS) use a few surgeon-assessed variables and have moderate accuracy (AUC often ~0.6) [

36]. Several included studies developed ML models that substantially improved prediction of clinically relevant POPF. Müller et al. (2025) applied an ensemble of ML algorithms to ~300 pancreaticoduodenectomies; their model incorporated dozens of clinical and radiologic features and achieved an AUC around 0.80 for POPF on validation, significantly outperforming the conventional FRS (~0.56 AUC) [

20]. This highlights AI

’s value in personalized risk stratification by analyzing complex, high-dimensional perioperative data that surgeons cannot easily synthesize alone. Similarly, other studies used ML to predict complications like liver insufficiency after hepatectomy or severe bile leak after bile duct injury repair, often reporting improved accuracy over logistic regression models [

37,

38]. Notably, most AI-based risk models to date have been developed retrospectively; prospective testing is still scarce. A consistent finding, however, is that combining human expertise with AI can be synergistic – e.g., an AI model might quickly flag high-risk patients, which the surgical team can then further evaluate and proactively manage (such as closer postoperative monitoring or preemptive interventions) [

39,

40].

Outcome prediction and decision support: Beyond immediate complications, AI has been used to predict oncologic outcomes like cancer recurrence or long-term survival. Models integrating tumor genomic data, radiologic features, and patient comorbidities have shown promise in forecasting which patients are likely to have early recurrence after resection, which could influence adjuvant therapy decisions. For example, one radiomics study could predict early recurrence of HCC from preoperative imaging and lab data, raising the prospect of tailoring follow-up intensity for high-risk patients [

41]. Another AI tool predicted which patients might not benefit from surgery at all due to very aggressive tumor biology, potentially guiding multidisciplinary discussions on alternative treatments [

42]. These predictive analytics tools carry ethical implications: using an AI to recommend against surgery or to alter standard treatment must be approached cautiously and transparently. Nonetheless, they offer an avenue for more data-driven clinical decisions in HPB oncology.

In summary, AI-based predictive models in HPB surgery show clear potential to enhance risk assessment, but their clinical integration is still in early phases. Surgeons could use such models to better inform patients of risks, optimize perioperative planning (e.g., allocate ICU beds for high-risk cases), or select patients for certain interventions. Importantly, any AI risk estimate must be interpreted in context – these tools should assist, not replace, clinician judgment. Most models need prospective validation; as one study pointed out, it will be critical to test AI risk predictions in real-time and see if acting on them actually improves patient outcomes. Moreover, issues of bias and generalizability exist: many models were trained on single-institution data and may not perform as well elsewhere (some risk factors might be center-specific). The push for external validation and eventual randomized trials (e.g., using AI risk tools versus standard care) is ongoing. [

43]

3.4. Intraoperative AR and Navigation

One of the most visually compelling applications of these technologies is augmented reality (AR) for intraoperative guidance. AR in surgery involves overlaying digital information (such as anatomical models, tumor locations, or navigation markers) onto the surgeon

’s field of view in real time, effectively providing a

“surgical GPS.” This can be implemented via specialized goggles or head-mounted displays (like the Microsoft HoloLens), or by overlaying on laparoscopic/robotic camera feeds on a monitor. [

22]

AR for open and minimally invasive surgery: Several pilot studies in our review implemented AR during liver or pancreatic resections. The common workflow is: a 3D model of the patient

’s anatomy (from preoperative imaging) is created and then registered to the patient on the operating table. Registration often uses surface landmarks or fiducial markers so that the virtual model aligns correctly with the real organ. For example, in an AR-guided liver surgery study, a CT-based 3D model of the liver (with tumor and vessels) was projected onto the live laparoscopic camera view [

44]. For instance, a snapshot of such an AR overlay is being shown to the surgeon for a planned segment 5 liver resection, with the tumor (green) and planned transection plane (red) delineated. By seeing this overlay, the surgeon gets a form of

“X-ray vision” – the ability to visualize hidden structures beneath the liver surface. This can guide where to cut and help avoid critical vessels that are not visible externally [

22,

45]

Technical feasibility and accuracy: The feasibility of AR has been demonstrated in small case series. Giannone et al. (2021) reported using an AR overlay in 3 cases of robotic liver resection. The AR model was displayed in the surgeon

’s console view, showing tumor and vasculature projections during the robotic hepatectomies. Surgeons found it helped localize lesions and plan transections. However, a noted limitation was the need for improved registration accuracy – misalignment of the virtual overlay by even a few millimeters could erode trust in the system. Organ deformation is a major issue: in soft tissues like the liver, once surgery begins and the organ is mobilized or resected partially, it changes shape, making static preoperative overlays increasingly inaccurate [

22]. Future solutions may involve real-time organ tracking or deformable models (potentially using AI to adjust the overlays continuously based on intraoperative imaging or sensors) [

46,

47]. Indeed, Giannone et al. specifically noted issues with organ deformation and lack of widespread support for the technology at present [

22].

Navigation and workflow: Despite these challenges, AR clearly adds value as a navigation aid. For example, AR has been used to guide the placement of trocars (ports) in minimally invasive HPB surgery by projecting an optimal port map onto the patient

’s abdomen [

22,

48]. It has also been applied to help locate small tumors during parenchymal transection by projecting their approximate depth/location [

48]. Surgeons generally still rely on tactile feedback or intraoperative ultrasound for confirmation, but AR provides an extra layer of information. In a recent mixed-reality study for pancreatic tumor resection, surgeons could see major blood vessels holographically

“through” the pancreatic tissue, which improved their confidence in dissecting around those structures (qualitatively reported) [

49].

Current evidence for AR

’s benefits is still low-level (case series and simulation studies), but almost all reports indicate it is technically achievable and subjectively improves the surgeon

’s situational awareness. Quantitative outcome improvements (like reduced positive margin rates or operative time) have yet to be robustly demonstrated. There is also a learning curve and significant setup required (segmentation, calibration in the OR). A 2021 review noted that AR in HPB surgery is

“far from standardized” due to high complexity and cost [

22]. Nonetheless, rapid improvements in computing power and graphics are making real-time AR more viable. We recommend that high-volume HPB centers and device companies continue to refine AR navigation systems, focusing on improving registration accuracy and user ergonomics. Meanwhile, practicing surgeons should consider participating in trials of AR guidance, as these technologies could foreseeably reduce guesswork in the future – for example, ensuring a bile duct tumor margin is clear by seeing ducts highlighted, or avoiding critical arteries in a difficult resection by having them virtually outlined [

50].

3.5. Robotics and AI Augmentation (Computer Vision in Surgery)

Another frontier is the use of AI-driven computer vision to analyze surgical video in real time, particularly in minimally invasive surgery. HPB procedures like laparoscopic cholecystectomy, liver resection, or pancreaticoduodenectomy generate rich video data from the endoscopic camera. By applying computer vision algorithms (usually deep learning models), this video stream can be analyzed to identify structures, surgical phases, or impending dangers, and then provide feedback or alerts to the operating surgeon [

51,

52,

53].

Automatic landmark and safety identification: A prominent example is objective recognition of the Critical View of Safety (CVS) during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. CVS is a method to ensure the cystic duct and artery are clearly identified before cutting, to prevent common bile duct injuries. Achieving CVS is typically a subjective assessment by the surgeon. One included study by Kawamura et al. (2023) developed an AI system to automatically detect when CVS had been attained. They trained a deep CNN on ~23,000 laparoscopic cholecystectomy video frames, labeled for presence or absence of key CVS criteria. The best model achieved ~83% accuracy in determining if CVS was achieved, operating at ~6 frames per second (nearly real-time). Such a system could potentially alert a surgeon if they have not yet adequately exposed critical structures [

19]. In effect, the AI serves as a

“safety coach” in the OR. Considering bile duct injuries are among the most dreaded complications in HPB surgery, this application has high significance. A recent review echoed that AI can reliably identify safe vs. unsafe zones during gallbladder dissection, reinforcing its potential to improve surgical safety [

54].

Beyond CVS, computer vision has been used to detect other anatomical landmarks in real time. Algorithms have been trained, for instance, to recognize the cystic duct, cystic artery, and common bile duct, or specific liver segments in the laparoscopic view. Early results are promising: a 2025 review by Kehagias et al. reported that such AI systems can detect landmarks with reasonable sensitivity, though challenges remain when the view is obscured by bleeding or fat [

55].

Real-time hazard detection: Another cutting-edge application is automatic detection of intraoperative bleeding and other hazards. In complex HPB surgeries, bleeding from small vessels can sometimes go unnoticed for critical seconds if the surgeon

’s focus is elsewhere. One innovative study (Crisan et al., 2023) designed a hazard detection system using the YOLOv5 deep learning model to identify bleeding in endoscopic video and immediately display alerts via an AR headset. The system distinguished true bleeding from look-alike events (such as spilled irrigating fluid) with high accuracy, highlighting the bleed with a bounding box on the surgeon

’s display in real time. Essentially, this is an AI-driven early warning system – a digital

“co-pilot” that never blinks, constantly scanning the operative field for hazards. In testing across recorded procedures, the system successfully alerted surgeons to bleeding events that were at times outside the central field of view or at the periphery. Such technology could reduce response time to hemorrhage, potentially improving patient safety in major liver or pancreatic resections where even a brief delay in controlling bleeding can have serious consequences [

23].

Robotic surgery integration: In robotic surgery, integration of AI is also advancing. The da Vinci surgical system already allows some digital interfacing – for example, the TileProTM feature can display auxiliary imaging (like preoperative scans or ultrasound) side-by-side with the operative view [

56]. Researchers are going further by embedding AI into robotic workflows. One aspect is surgical skill analysis – computer vision can analyze the motion of instruments (captured via the robot

’s kinematic data or video) to grade the surgeon

’s skill or identify suboptimal technique. While our review focused on clinical outcome tools, it

’s worth noting that some surgery studies have used AI to assess technique quality for training purposes [

57].

Perhaps the most futuristic concept is partially or fully autonomous robotic actions. In experimental settings outside HPB, AI has been used to automate certain surgical subtasks. For example, a research group demonstrated an autonomous laparoscopic intestinal anastomosis where an AI-guided robot performed suturing in an animal model [

58]. Moreover, there is a report of an autonomous camera navigation system: an AI controlled the endoscope to keep the instruments and target in view at all times, which could impact minimally invasive HPB surgeries in the future. While these early autonomies do not directly improve patient outcomes yet, they reduce the need for an assistant and provide steadier visualization. In our review, no study reported a fully autonomous major surgical step in humans (nor would that be ethical at present), but these developments lay the groundwork. Experts envision that AI might handle routine parts of surgery (like optimally adjusting the camera or monitoring for bleeding) so that surgeons can focus on critical decisions and maneuvers [

59].

3.6. Postoperative Video Analytics

A concrete benefit of these advances, already being realized, is in operative documentation and analysis. AI can automatically segment surgical video post hoc into key phases (induction, dissection, resection, anastomosis, closure, etc.. This can aid in efficient review of surgeries, training (surgeons can get a summary of where time was spent in each phase), and even research correlating technique with outcomes. For instance, if an adverse event occurs, AI- analyzed video might pinpoint that a certain landmark was not identified or a wrong plane was entered, offering insights for quality improvement [

60,

61].

In summary, computer vision in HPB surgery is enabling a new level of intraoperative awareness. By recognizing anatomy, guiding the surgeon through critical steps (like confirming CVS), and flagging dangers, these AI systems act as an intelligent assistive layer over the surgical procedure. While still early-stage, evidence suggests such tools are feasible and can perform near expert-level in narrow tasks (e.g., identifying a specific landmark or bleeding source) [

52,

62,

63,

64]. They must, however, be rigorously tested for reliability, because false negatives or false positives could themselves pose risks (a missed alert or a false alarm could distract the team). Proper development and validation will be key. If successful, these systems could significantly enhance safety – one can envision essentially eliminating bile duct injuries or uncontrolled bleeding through earlier detection and standardized guidance [

65]. Importantly, the surgeon remains in control at all times; the AI

’s role is to support and enhance human performance, not replace it.

4. Discussion

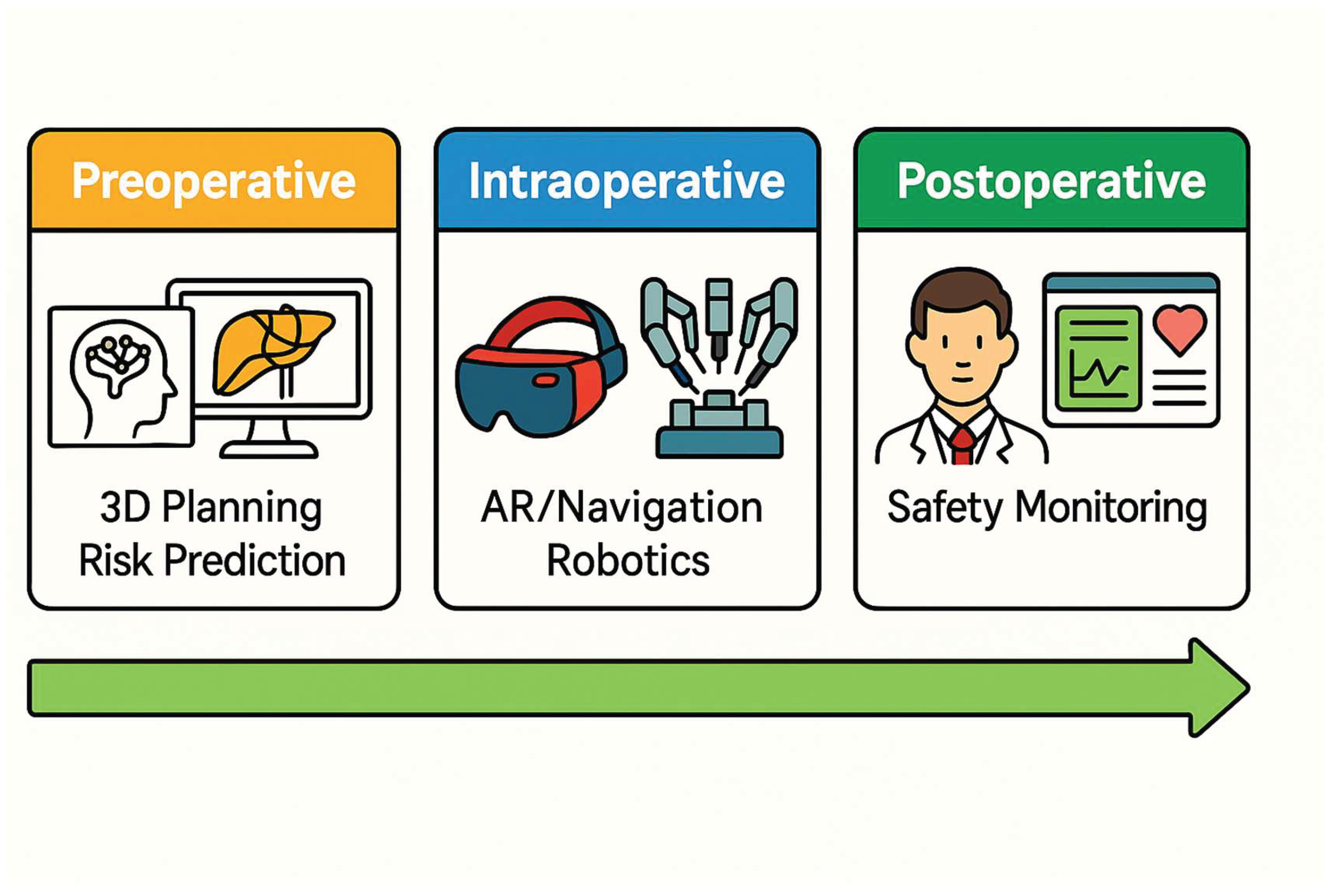

This systematic review reveals that the integration of AI and digital tools into HPB surgery is no longer theoretical – numerous proof-of-concept studies and early clinical evaluations have been conducted across the surgical pathway.

Figure 2 provides a visual summary of the main categories of AI application during the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative stages Overall, AI applications show tremendous promise in augmenting surgeon capabilities, from improving diagnostic accuracy preoperatively to enhancing decision-making and precision intraoperatively. At the same time, our review highlights that most studies to date are preliminary, single-center investigations with relatively small sample sizes or short follow-up. Therefore, while the results are encouraging, broad claims of AI

’s superiority should be tempered until larger-scale validation is achieved.

4.1. Key Findings and Current Evidence

Across the domains we examined, some key themes emerge. In the preoperative phase, AI systems (especially deep learning models) have demonstrated expert-level performance in interpreting imaging for HPB diseases. For instance, algorithms can identify tiny liver lesions or subtle textural differences indicative of tumor aggressiveness that radiologists might overlook [

66,

67]. A striking example from our review was an AI that detected pancreatic cancer on EUS with 95% accuracy, a task that can be challenging even for experienced endosonographers. In the risk prediction domain, ML models integrated numerous patient features to outperform traditional risk scores for complications like pancreatic fistula [

68,

69]. These models highlight how AI can synthesize complex clinical data into usable risk estimates, potentially guiding surgeons in perioperative management (e.g., decisions on drain placement or enhanced monitoring for high-risk patients). In surgical planning, AI-assisted 3D modeling and simulation give surgeons better

“maps” of patient anatomy and possible resection approaches; our findings suggest this may improve intraoperative confidence and could lead to better outcomes (as evidenced by the RCT of AI-enhanced 3D planning showing reduced blood loss). Intraoperatively, augmented reality and computer vision provide surgeons with tools to visualize the invisible and to maintain awareness of critical details – effectively enhancing the surgeon

’s sensory and decision environment in real time. [

33,

70]. From recognizing the CVS to highlighting bleeding, these tools function as a vigilant assistant.

However, it must be emphasized that current evidence is largely Level IV (case series) and observational. Few studies directly measured improvements in patient outcomes attributable to these technologies. Many reported surrogate endpoints (accuracy of detection, time saved, user ratings, etc.). The leap from demonstrating an AI tool works in principle to proving it tangibly improves surgical outcomes is one that the field has yet to comprehensively make. We identified only one randomized controlled trial involving an AI tool (the 2025 study on 3D model use in planning), and even that had a moderate sample size (n=64) [

33]. No trials yet exist, for example, randomizing surgeries with vs. without AR navigation to see differences in margin status or complication rates. Therefore, the quality of evidence is moderate for diagnostic imaging applications (where multiple independent studies concur on high accuracy) and low-to-moderate for intraoperative guidance (where reports are few and heterogeneous).

4.2. Evidence Quality and Bias

Many included studies had methodological limitations. Common issues were small sample sizes, retrospective designs, single-center data, and lack of external validation – all of which raise risk of bias. Using PROBAST [

16], we found that a number of prediction model studies had

“unclear” or

“high” risk of bias in the analysis domain, often due to lack of independent validation or non-transparent model building (e.g., some did not report how hyperparameters were optimized, raising concerns of overfitting). For diagnostic AI studies, patient selection bias was an issue – e.g., using only

“ideal” images or excluding very challenging cases. There is also potential publication bias: successful applications are more likely reported than negative or neutral findings. We attempted to mitigate this by comprehensive searching and broad inclusion criteria, but it

’s possible that unsuccessful AI projects remained unpublished, skewing the literature toward positive results.

In terms of evidence grading, applying GRADE criteria is tricky for such heterogeneous literature. Broadly, evidence for AI in imaging diagnosis could be considered moderate to high in certain niches (for instance, AI for detecting liver tumors has been reproduced in several settings, lending confidence to generalizability). On the other hand, evidence for AR and intraoperative AI is low to moderate – mostly limited to feasibility studies or small series without definitive proof of outcome benefit. No large trials or meta-analyses exist yet. This indicates we are at an early evidence level for intraoperative guidance tools.

Crucially, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or other high-quality prospective studies are needed. We acknowledge RCTs are challenging in surgical technology research, but for AI we may need creative trial designs. For instance, cluster-RCTs where certain centers adopt the AI tool and others use standard care, or stepped-wedge designs as AI tools become available. Without such evidence, widespread adoption will lag, and clinicians will remain uncertain about true benefit. Encouragingly, some trials are underway – e.g., an international trial on AI-based coaching during cholecystectomy (using an AI to guide trainees) showed improved safety for trainees [

71], though that pertains more to education than direct patient outcome. As more data emerge, future systematic reviews can better quantify effect sizes of AI interventions.

4.3. Safety and Ethical Considerations

The introduction of AI and advanced digital tools into surgery brings significant safety and ethical considerations. First is the question of responsibility and liability. If an AI system provides a recommendation or alert that leads the surgical team astray (for example, a false overlay that misidentifies anatomy, or an erroneous risk prediction that influences a treatment decision), who is accountable for the outcome? Ultimately, the surgeon of record is responsible for patient care, and AI is an assistive tool. However, as AI advice becomes more influential, ambiguity in attributing error may arise. Clear guidelines and possibly legal frameworks will be needed to delineate accountability for AI-driven decisions.

Transparency of AI algorithms is also critical. Many AI models, particularly deep learning, are “black boxes” that do not explain their reasoning. In a high-stakes domain like surgery, blind trust in an opaque model is risky. Surgeons and patients will demand some level of interpretability or at least robust validation to trust these systems. There is a push in the AI community for “explainable AI,” which could help – for example, heatmaps that show which part of an image led to a tumor prediction. Regulatory agencies may eventually require explainability for clinical AI tools.

Data privacy and security is another concern. AI models often require large datasets of patient images and records for training. This raises issues of how that data is stored and shared. Initiatives to create multi-institutional surgical video databases are underway, but must address patient consent and anonymization properly. Surgeons using wearable AR devices or recording surgeries for AI analysis need to ensure compliance with privacy laws (e.g., HIPAA). Additionally, AI tools integrated with hospital systems could become targets for cyberattacks; a hacked system could theoretically display incorrect guidance or steal data.

Algorithmic bias is well-documented in AI: if the training data is not representative, the AI’s performance can be worse for certain patient groups, inadvertently perpetuating healthcare disparities. For example, an AI trained mostly on data from high-resource hospitals might perform poorly in low- resource settings or with atypical patient demographics. Ensuring diverse and representative training data is important so that AI tools are equitable and do not underserve minorities or rare conditions.

Patient autonomy and consent also come into play. Should patients be informed that an AI will assist in their surgery or in their care plan? We believe transparency with patients is paramount. Just as one would inform a patient about a trainee assisting in surgery, it may be prudent (and trust-building) to tell patients about the use of an AI tool in their surgical care. Some scenarios are straightforward (e.g., an AI used preoperatively to measure liver volume need not be explicitly consented beyond usual radiology practice), but others might require discussion (e.g., if a surgeon plans to rely on an AR device during a resection).

From an educational standpoint, surgeons should guard against over-reliance on AI. There is a potential risk that future trainees become too dependent on navigation aids and do not develop the same level of anatomic skill and vigilance – somewhat akin to how GPS affects drivers

’ navigational skills. In fact, an editorial on large language models (LLMs) in surgery noted that overreliance on AI for decision support could compromise critical thinking development in trainees [

72]. Thus, training curricula will need to balance AI use with fundamental surgical education.

Finally, the regulatory oversight of AI in surgery is evolving. Many AI tools would fall under medical device regulations. Bodies like the U.S. FDA have started frameworks for

“Software as a Medical Device (SaMD)” which would include certain AI algorithms [

73,

74]. Dynamic, learning systems pose a challenge – an AI that continually improves with more data is a moving target for approval. We may see requirements for periodic re-certification of AI tools, and guidelines specifically tailored to AI in the surgical domain (some have called for an

“AI in Surgery” guideline or checklist). Indeed, an international consensus (the FUTURE-AI guidelines) has outlined principles for trustworthy AI in healthcare, including fairness, transparency, accountability, and reliability [

75] – these certainly apply to surgical AI as well.

In summary, safety and ethics must remain at the forefront as we integrate AI into HPB surgery. The surgical community should proactively engage with ethicists, legal experts, and regulators to establish standards ensuring these tools improve patient care without introducing new risks. Principles such as transparency, justice (equitable performance across populations), and surgeon oversight should guide AI deployment. For example, Arjomandi et al. (2025) emphasize developing robust ethical frameworks and regulatory guidelines for safe AI implementation in surgical practice [

76]. Ultimately, AI should be viewed as a means to enhance human decision-making, and maintaining patient trust will be crucial for its acceptance.

4.4. Clinical Guidance for Surgeons

Based on our findings, we can distill some practical guidance for HPB surgeons regarding adoption of AI and digital tools:

•Preoperative Planning: Surgeons should start leveraging available digital planning tools, especially for complex cases. Even if advanced AI is not readily at hand, using 3D reconstructions (which can often be generated with current software) can improve understanding of anatomy. If your center has access to AI-assisted volumetry or tumor segmentation tools, consider incorporating them into pre-surgical workflow. They can provide objective data on tumor size, location, and resection volume that complement the surgeon’s assessment.

• Augmented Reality in the OR: If participating in a program or trial with AR navigation, approach it as an adjunct, not a replacement, for traditional guidance techniques. Ensure that you double-check AR information with real-world cues (e.g., confirming a virtually highlighted vessel by ultrasound or direct visualization when possible). Early adopters of AR should be prepared for technical hiccups and have a low threshold to abandon the technology mid- procedure if it is not aligning well – patient safety comes first. However, engaging with AR is valuable; it gives the surgeon insight into the potential and limitations of the system. Surgeons can also help engineers improve these systems by providing feedback on what information is most useful intraoperatively.

• Robotic Surgery Integration: Robotic HPB surgeons should take full advantage of existing digital features on their platforms. For instance, use the TilePro function to display imaging (CT/ MR or ultrasound) in your console during resections. As new AI-driven robotic features become available (such as automatic camera tracking or instrument tip identification), incorporate them gradually and evaluate their impact on workflow. Be aware that current-generation robots are mostly teleoperative (surgeon-controlled), but future models may offer more automation – maintain situational awareness and do not become complacent even if an AI is managing a subtask. Always supervise any autonomous function closely.

• AI-Based Decision Support: If using an AI risk calculator or predictive model for clinical decisions, use it to inform rather than dictate decisions. For example, if an ML model predicts a high risk of liver failure for a planned extended hepatectomy, use that information to revisit the plan – perhaps stage the resection or ensure optimal patient conditioning beforehand. But also scrutinize whether the model’s factors make sense (e.g., if it weights age heavily, consider the patient’s physiological vs chronological age). In essence, combine the “wisdom” of the model with your clinical acumen. Document such decisions and discussions (for medicolegal protection, note that an AI tool was used as a decision aid).

• Training and Team Preparation: When introducing new digital tools, educate the entire OR team. Everyone – anesthesiologists, nurses, assistants – should know what the AI or AR system is supposed to do and what its limitations are. For example, if using an AR overlay, the team should discuss the backup plan if the system fails or shows something unexpected. Similarly, if relying on AI monitoring (like automatic bleeding alerts), ensure that human monitoring is still happening and that the team doesn’t become less vigilant due to a false sense of security. Essentially, don’t let the team’s guard down just because an AI is on duty.

• Continuous Learning: The field of AI in surgery is evolving rapidly. Surgeons should consider at least a basic education in data literacy and AI principles. Many training programs and workshops are emerging for surgeons to learn about AI. Understanding how algorithms work (even conceptually) can help in critically appraising their output. HPB surgeons should also keep an eye on new guidelines or consensus statements; professional societies may soon issue recommendations on using AI in surgical practice (for example, guidelines on reporting surgical AI studies, or credentialing requirements for using AR systems).

• Patient Communication: Integrate discussions about digital tools into patient consultations when appropriate. For instance, you might tell a patient, “We will create a 3D model of your liver to help plan the surgery” – most patients find that reassuring. If using an experimental AI or participating in a trial, obtain proper informed consent and explain the potential benefits and unknowns. In our experience, patients are generally receptive to the idea of advanced technology assisting their surgeon, as long as it’s clear the surgeon is still in charge.

By following these techniques, surgeons can responsibly embrace technology while maintaining high standards of care. The goal is to become “digitally augmented surgeons” – using all available tools to benefit patients, but remaining the captain of the ship.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

This review is one of the first comprehensive systematic reviews focusing specifically on AI in HPB surgery (as opposed to AI in surgery generally, or AI in radiology alone). By combining disparate study types under one umbrella, we provide HPB clinicians with a panoramic perspective of how AI might impact every step of the surgical process. A strength of our review is this breadth: readers can appreciate the continuum from preoperative AI diagnostics to intraoperative guidance and even postoperative analytics, all in the HPB context. We also included the most recent studies (through mid-2025), capturing very up-to-date advances such as AR-guided pancreatic surgery and AI-enhanced fluorescence imaging that were not covered in earlier reviews. We applied a robust multi-database search and used independent dual screening, which reduces the chance that we missed major relevant articles. Additionally, we assessed risk of bias and discuss evidence quality, adding a critical lens to interpret the findings responsibly rather than simply hyping technology.

On the flip side, by covering such breadth, our review sacrifices some depth in each subdomain. Each of the areas (e.g., radiomics for HCC, or AR for liver surgery) could warrant its own in-depth review or meta-analysis. We aimed for a balanced discussion relevant to clinical readers rather than data scientists, which means some technical details (like specific algorithm architectures or training techniques) are glossed over. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of included studies, which precluded meta-analysis. We could not quantitatively synthesize effects, so our conclusions are qualitative and potentially subject to our interpretation bias. We also did not systematically examine cost-effectiveness – an important consideration for adopting these technologies. Currently, many tools are prototypes and cost data are scarce, but as tools mature, formal cost–benefit analyses will be needed (e.g., is an expensive AR system justified by a reduction in complications?).

Some limitations temper our findings such as 89% of studies were retrospective, risking selection bias, only 5/38 tools were externally validated, raising questions about scalability and ethical frameworks for AI-assisted surgery (e.g., informed consent protocols) remain undefined. Out of 38 studies, 62% had high risk of bias in analysis (PROBAST), primarily due to inadequate validation.

Furthermore, our search focused on published literature; we might have missed very recent conference abstracts or industry research not in the public domain. However, by updating through mid-2025 and scanning references of relevant articles, we believe we captured the major developments. We also acknowledge that our review can become outdated quickly given the rapid evolution of AI – this is an inherent limitation when covering a fast-moving field. Our work is a “snapshot” up to mid-2025; readers should stay alert to new studies emerging literally every month.

Despite these limitations, we have tried to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date synthesis, with critical appraisal, to guide both surgeons interested in adopting new technologies and researchers aiming to identify gaps for future study.

5. Future Directions

The trajectory of AI in HPB surgery is clearly toward more integrated and intelligent systems. We anticipate that various AI components – imaging analysis, risk prediction, navigation, and vision assistance – will converge into unified platforms. For example, one can imagine an “HPB Surgery AI Suite” where a patient’s data are processed end-to-end: preoperatively, the system analyzes imaging and predicts potential difficulties; intraoperatively, it provides AR overlays and safety alerts; postoperatively, it analyzes surgical video to produce an operative report and even recommends improvements for the surgeon’s technique. Achieving this vision will require collaboration between surgeons, computer scientists, and industry engineers. Priority areas for robotic-AI integration include real-time instrument tracking, safety-critical alerts such as vessel proximity and standardized API frameworks for interoperability.

Data sharing and large datasets will be fundamental. As mentioned, many current models are limited by training data volume and diversity. Initiatives to create multi-institutional databases of annotated surgical videos (with proper anonymization and consent) are in progress and should be supported [

77,

78]. These will provide the

“fuel” (big data) needed for robust algorithm development. Efforts like international surgical AI consortia or the establishment of shared video repositories can facilitate data sharing and standardize how surgical events are labeled.

Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, LLaMA, Mistral and similar, represent another frontier that might intersect with HPB surgery. While LLMs are not directly performing surgical tasks, they could serve supporting roles in aggregating and delivering knowledge. For instance, an LLM-based assistant might be queried in real time for advice on an unusual intraoperative finding (

“What are the management options if I encounter tumor thrombus in the portal vein?”) and it could rapidly provide synthesized knowledge from guidelines or literature. A recent editorial by Chen et al. (2025) discussed how LLMs demonstrate potential in clinical documentation automation, complex data analysis, and real-time decision support in HPB surgery, but also highlighted challenges like AI

“hallucinations” (confidently generating false information) and the need for oversight [

79]. It

’s conceivable that future ORs might have voice-activated AI assistants – a surgeon could ask for recommended maneuvers or retrieve patient data hands-free. Before that happens reliably, LLMs need to become more accurate and context-aware, and hospitals would need to permit their use under secure conditions.

Another area is integrating precision medicine into surgical AI. As precision oncology advances, surgery will not remain an isolated discipline. We foresee AI enabling integration of genomic and molecular data into surgical decision-making. For example, if a patient

’s tumor genomics suggest indolent disease, perhaps a limited resection or ablation could suffice versus an aggressive surgery. Conversely, high-risk biology might prompt a more extensive resection or multi-modal approach. Some groundwork for such

“radiogenomic” models exists already [

80]. In future HPB, one could imagine combining liver tumor genomics, imaging AI features, and anticipated regenerative capacity to tailor how much liver to resect for an optimal outcome. Though speculative, this aligns with the trend towards individualized therapy.

Usability and workflow integration: Future tools must be user-centric. One reason some technologies fail to gain traction is poor usability. Surgeons are busy and will not adopt something that significantly slows them down or is overly complex [

81]. Future AR systems, for instance, should be near plug-and-play – automatically registering without lengthy manual calibration. The user interface should be intuitive, providing information in a minimally intrusive way (perhaps selectively showing critical info rather than cluttering the view). Haptic feedback or auditory alerts could complement visual AR to avoid information overload. The next generation of surgical robots might come with native AI integration, designed from the ground up with these features rather than tacked on after the fact. We expect upcoming robotic platforms (beyond da Vinci, such as newer systems by various companies) to advertise AI capabilities like automated sub-tasks, built-in AR imaging, and smart safety features (e.g., auto-pausing if an instrument nears a vital structure unexpectedly).

Validation and certification: Before routine clinical use, rigorous validation is needed. We anticipate more prospective trials in the next 5–10 years. Perhaps certain AI tools will undergo phase I/II style trials (assessing safety and feasibility, then efficacy). Regulatory bodies might stipulate that surgical AI meet specific performance benchmarks (for example, ≥95% sensitivity for critical structure detection). There may also be a role for simulation in validation – e.g., testing AI on recorded surgeries to see how often it would have prevented an adverse event or given false alarms. A kind of “digital twin” of clinical trials can be run on retrospective data to justify prospective testing. Post-market surveillance will also be crucial: AI systems might require periodic re-validation to ensure they perform as expected as data drifts over time.

Education and training: The surgeon of the future needs to be adept with technology. Surgical residency programs may incorporate formal training on digital tools – for instance, sessions on how to interpret AI outputs, use AR goggles, or troubleshoot a robot’s AI feature. Just as surgical simulation is now part of training, we might see AI-assisted simulators where residents operate with an “AI mentor” that provides feedback. However, caution is warranted that reliance on AI doesn’t diminish the development of fundamental surgical skills and judgment. Training curricula will have to emphasize AI as a support tool and ensure trainees can perform without it as well. Interestingly, AI might also personalize training – analyzing a trainee’s performance over cases and identifying specific areas to improve (e.g., speed of attaining CVS or economy of motion in suturing).

Interdisciplinary collaboration: We predict increasing collaboration between surgeons and data scientists. Some hospitals now have “clinical AI” teams that pair clinicians with AI developers to solve problems. In HPB surgery, surgeons should actively contribute to the development process: for example, by helping label data (what is important to identify in a video), defining clinical requirements (what accuracy would make a tool useful), and piloting prototypes. This co-development will ensure the final products truly meet clinical needs rather than being tech demos. The role of surgeon–data- scientist is even emerging – clinicians who gain expertise in AI and drive projects from within.

Regulations and guidelines: The surgical community may develop its own guidelines for AI use, analogous to how societies issue guidelines on new technology adoption. We might see position statements on “Safe Use of Augmented Reality in Surgery” or “Standards for Reporting Surgical AI Studies” (some of which are already being discussed). As noted, the FUTURE-AI consortium has published principles for trustworthy AI in healthcare. Expect future guidelines to explicitly call for things like continuous monitoring of AI performance post-deployment and involving patients in decisions about AI use. Professional surgical bodies may also integrate AI topics into training curricula and certification (for example, mandates that surgeons demonstrate understanding of an AI tool before using it clinically).

In conclusion of future directions, the coming decade will likely transform how HPB surgery is planned and performed. We will move from the current phase of isolated pilot studies to integrated systems that assist the surgeon at each step. Realizing this future requires careful work on many fronts: technical innovation, clinical validation, ethical oversight, and surgeon education. If done correctly, HPB surgeons of the future will operate with greater knowledge (thanks to AI analysis), greater precision (thanks to real-time guidance), and greater confidence (thanks to predictive analytics and automation of tedious tasks). The focus must remain on patient outcomes – technology for its own sake is not the goal, but rather a means to safer, more effective, and more personalized surgical care.

6. Conclusions

AI and digital technologies are poised to revolutionize HPB surgery, bringing us into an era of augmented surgical intelligence. Our systematic review shows that from imaging to intraoperative guidance, AI applications have demonstrated the ability to enhance the precision, safety, and efficacy of HPB surgical care. In preoperative imaging, AI algorithms can now detect and characterize liver and pancreatic tumors with accuracies matching or exceeding expert radiologists, which could lead to earlier diagnoses and better surgical planning. Machine learning models improve risk stratification, enabling more personalized patient management by predicting complications like pancreatic fistula or tumor recurrence with greater fidelity than traditional scores. During surgical planning, automated 3D reconstructions and simulations allow surgeons to rehearse and map out complex resections in ways not possible with conventional 2D imaging alone. In the operating room, augmented reality offers surgeons “X-ray vision” – the ability to visualize hidden anatomical details – while computer vision monitors the surgical field for critical landmarks and hazards, acting as a real-time patient safety net.

Importantly, these advances do not replace the surgeon; rather, they empower the surgical team with better information and tools for decision-making. We are witnessing the maturation of the concept of the “digital surgeon,” who leverages data and AI support much like a pilot relies on avionics. The ultimate beneficiary is the patient: these technologies, once validated and appropriately implemented, should translate to safer surgeries, fewer complications, and possibly better long-term outcomes through more accurate resections and tailored therapies.

Yet, the journey from promising studies to routine practice requires continued effort. We emphasize that robust clinical trials are needed to demonstrate that using a given AI tool actually improves patient outcomes or workflow efficiency, beyond anecdotal or surrogate measures. Surgeons should be involved in the development and validation process to ensure these tools address real-world needs and are user-centric. Issues of interoperability also must be solved – for instance, integrating AI software with hospital IT systems and various surgical devices seamlessly. Training will be key: future surgeons need education not only in operative techniques but also in interpreting AI outputs and understanding their limitations. On the research front, adherence to reporting standards (like CONSORT-AI for trials or the upcoming PRISMA-AI for reviews) will help the field accumulate high-quality evidence and avoid hype-driven adoption. We anticipate that as evidence grows, professional guidelines will emerge on best practices for incorporating AI into surgical care.

In summary, the field of HPB surgery is at a transformative moment. The synergy of surgical domain knowledge with cutting-edge AI has begun to yield tangible improvements, as documented in this review. As technology continues to advance and more 2024–2025 studies emerge (including those exploring LLMs and next-generation smart robotics), we anticipate that the next decade will see AI ingrained in the standard of care for HPB surgery. To prepare for this future, a close partnership between surgeons, engineers, and regulatory bodies is essential. By maintaining scientific rigor and focusing on patient-centered outcomes, we can ensure that these digital innovations truly fulfill their promise: making hepatopancreatobiliary surgery safer, more effective, and more precise than ever before.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception, design, and execution. Mr. Efstathiou and Mrs. Charitaki performed the literature search and data extraction. Mrs Triantopoulou and Mr. Delis assessed risk of bias and quality. Mr. Efstathiou drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically reviewed and edited it. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable (systematic review of published studies).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable (no new patient data).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our colleagues in the HPB surgery and biomedical engineering departments for their insightful discussions and support during this project. We are grateful to the Journal of Clinical Medicine editorial team for the opportunity to contribute to this special issue on advances in HPB surgery.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

References

- Agrawal, H.; Tanwar, H.; Gupta, N. Revolutionizing hepatobiliary surgery: impact of three-dimensional imaging and virtual surgical planning on precision, complications, and patient outcomes. Artif Intell Gastroenterol. 2025, 6, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zureikat, A.H.; Postlewait, L.M.; Liu, Y.; Gillespie, T.; Weber, S.M.; Abbott, D.E.; et al. A multi-institutional comparison of perioperative outcomes of robotic and open pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2016, 264, 640–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.J.; Li, D.L.; Lin, H.M.; Wang, J.F.; Luo, Y.M.; Tang, Y.; et al. Bibliometrics of artificial intelligence applications in hepatobiliary surgery from 2014 to 2024. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2025, 17, 104728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bektaş, M.; Chia, C.M.; Burchell, G.L.; Daams, F.; Bonjer, H.J.; van der Peet, D.L. Artificial intelligence-aided ultrasound imaging in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery: where are we now? Surg Endosc. 2024, 38, 4869–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadebecq, F.; Vasconcelos, F.; Mazomenos, E.; Stoyanov, D. Computer vision in the surgical operating room. Visc Med. 2020, 36, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, T.; Liu, S.; Dai, Y.; Jin, Y. Real-time image fusion and Apple Vision Pro in laparoscopic microwave ablation of hepatic hemangiomas. npj Precis Onc. 2025, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Chen, G.; et al. Deep learning-based prediction of post-pancreaticoduodenectomy pancreatic fistula: development and validation of preoperative and perioperative models. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 51777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Balian, J.; Hadaya, J.; Premji, A.; Shimizu, T.; Donahue, T.; Benharash, P. Machine Learning-based Prediction of Postoperative Pancreatic Fistula Following Pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2024 Aug 1;280, 325–331. [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Gupta, S. Automated diagnosis and classification of liver cancers using deep learning techniques: a systematic review. Discover Appl Sci. 2024, 6, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlani, P.; Ghosh, N.K.; Kumar, A. Role of artificial intelligence in the characterization of indeterminate pancreatic head mass and its usefulness in preoperative diagnosis. Artif Intell Gastroenterol. 2023, 4, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades Pérez, M.; Espin Álvarez, F.; Pardo Aranda, F.; Navinés López, J.; Vidal Piñeiro, L.; Zarate Pinedo, A.; Piquera Hinojo, A.M.; Sentí Farrarons, S.; Cugat Andorra, E. Augmented reality in hepatobiliary-pancreatic surgery: a technology at your fingertips. Cirugía Española. 2023, 101, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman J, Sengul I, Němec M, Sengul D, Penhaker M, Strakoš P, et al. Augmented and mixed reality in liver surgery: a comprehensive narrative review of novel clinical implications on cohort studies. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2025, 71, e20250315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntourakis, D.; Memeo, R.; Soler, L.; et al. Augmented reality guidance for the resection of missing colorectal liver metastases: an initial experience. World J Surg. 2016, 40, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Yeerkenbieke, P.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Automatic bleeding detection in laparoscopic surgery based on a faster region-based convolutional neural network. Ann Transl Med. 2022 May;10, 546. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372:n71. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, R.F.; Moons, K.G.M.; Riley, R.D.; Whiting, P.F.; Westwood, M.; Collins, G.S.; et al. PROBAST: a tool to assess risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med. 2019, 170, 51–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.S.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011, 155, 529–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Gu, J.; Xu, D.; Song, L.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Deep learning radiomics based on contrast-enhanced ultrasound images for assisted diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, M.; Endo, Y.; Fujinaga, A.; Orimoto, H.; Amano, S.; et al. Development of an artificial intelligence system for real-time intraoperative assessment of the Critical View of Safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37(11), 8755–8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.C.; Erdem, S.; Müller, B.P.; Künzli, B.; Gutschow, C.A.; Hackert, T.; Diener, M.K. Artificial intelligence and image guidance in minimally invasive pancreatic surgery: current status and future challenges. Artif. Intell. Surg. 2025, 5, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhou, B.; Tang, L.; Liang, Y. Integrating mixed reality, augmented reality, and artificial intelligence in complex liver surgeries: Enhancing precision, safety, and outcomes. iLiver 2025, 4(2), 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannone, F.; Felli, E.; Cherkaoui, Z.; Mascagni, P.; Pessaux, P. Augmented Reality and Image-Guided Robotic Liver Surgery. Cancers 2021, 13(24), 6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, N.; Gherman, B.; Radu, C.; Tucan, P.; Iakab, S.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Based Hazard Detection in Robotic-Assisted Single-Incision Oncologic Surgery. Cancers 2023, 15(13), 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomohaci, M.D.; Grasu, M.C.; Băicoianu-Nițescu, A.; Enache, R.M.; Lupescu, I.G. Systematic Review: AI Applications in Liver Imaging with a Focus on Segmentation and Detection. Life 2025, 15(2), 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Xu, H.; Peng, B.; Huang, X.; Hu, Y.; et al. Illuminating the future of precision cancer surgery with fluorescence imaging and artificial intelligence convergence. npj Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, Article 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, W.; Qiu, J.; et al. Radiomics analysis of preoperative CT for prediction of early recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. Cancer Imaging. 2021, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereska, J.I.; Janssen, B.V.; Nio, C.Y.; Kop, M.P.M.; Kazemier, G.; et al. Artificial intelligence for assessment of vascular involvement and tumor resectability on CT in patients with pancreatic cancer. Eur Radiol Exp. 2024, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Azadvar, S.; Heiselman, J.; Jiang, X.; Miga, M.I.; Wang, L. LIBR+: Improving intraoperative liver registration by learning the residual of biomechanics-based deformable registration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.06901 [Preprint]. 2024 Mar 11. arXiv:2403.06901 [Preprint]. 2024 Mar 11. [CrossRef]

- Sethia, K., Strakos, P., Jaros, M. et al. Advances in liver, liver lesion, hepatic vasculature, and biliary segmentation: a comprehensive review of traditional and deep learning approaches. Artif Intell Rev 58, 299 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Moglia, A.; Cavicchioli, M.; Mainardi, L.; et al. Deep learning for pancreas segmentation on computed tomography: a systematic review. Artif Intell Rev. 2025, 58, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamoto, T.; Ban, D.; Nara, S.; Mizui, T.; Nagashima, D.; Esaki, M.; Shimada, K. Automated three-dimensional liver reconstruction with artificial intelligence for virtual hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022 Oct;26, 2119–2127. [CrossRef]

- Kazami, Y.; Kaneko, J.; Keshwani, D.; Kitamura, Y.; Takahashi, R.; Mihara, Y.; et al. Two-step artificial intelligence algorithm for liver segmentation automates anatomic virtual hepatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2023 Nov;30, 1205–1217. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Dong, B.; et al. Randomized comparison of AI-enhanced 3D printing and traditional simulations in hepatobiliary surgery. npj Digit Med. 2025, 8, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaheri, H.; Ghamarnejad, O.; Bade, R.; Lukowicz, P.; Karolus, J.; Stavrou, G.A. Beyond the visible: preliminary evaluation of the first wearable augmented reality assistance system for pancreatic surgery. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2024, 19, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, M.; Kausar, A. Can 3D visualisation and navigation techniques improve pancreatic surgery? A systematic review. Artif Intell Surg. 2023, 3, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.; Shin, S.H.; Park, D.J.; Kim, N.; Heo, J.S.; Choi, D.W.; Han, I.W. Validation of original and alternative fistula risk scores in postoperative pancreatic fistula. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019 Jul 1;26, 354–359. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mai, R.Y.; Liu, Y.W.; Lu, H.J.; Li, L.; Liu, H.; et al. Machine learning prediction model for post-hepatectomy liver failure in hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter study. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 986867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaf, A.; Munir, M.M.; Khan, M.M.M.; Rashid, Z.; Khalil, M.; Guglielmi, A.; et al. Machine learning based prediction model for bile leak following hepatectomy for liver cancer. HPB (Oxford). 2025, 27, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, M.; Almaatouq, A.; Malone, T. When combinations of humans and AI are useful: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat Hum Behav. 2024, 8, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Puri, S.; Ozrazgat-Baslanti, T.; Bhat, R.; Feng, Z.; Momcilovic, P.; et al. Comparing Clinical Judgment with MySurgeryRisk Algorithm for Preoperative Risk Assessment: A Pilot Study. Crit Care. 2018, 22, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.D.; Guan, M.J.; Bao, Z.Y.; Shi, Z.J.; Tong, H.H.; Xiao, Z.Q.; et al. Radiomics analysis based on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for predicting early recurrence after hepatectomy in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 22240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Galicia, A.E.; Rincón-Sánchez, M.N.; Ramírez-Mejía, M.M.; Méndez-Sánchez, N. Outcome prediction for cholangiocarcinoma prognosis: embracing the machine learning era. World J Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 106808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenig, N.; Monton Echeverria, J.; Muntaner Vives, A. Artificial intelligence in surgery: a systematic review of use and validation. J Clin Med. 2024 Nov 24;13, 7108. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.Y.; Yoon, K.C.; Hyeon, S.; Jang, T.; et al. Navigating the future of 3D laparoscopic liver surgeries: visualization of internal anatomy on laparoscopic images with augmented reality. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2024, 34, —. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalhinho, J.; Yoo, S.; Dowrick, T.; Koo, B.; Somasundaram, M.; et al. The value of augmented reality in surgery—a usability study on laparoscopic liver surgery. Med Image Anal. 2023, 86, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]