Submitted:

05 August 2025

Posted:

06 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. RNA-Seq Quality and Alignment Statistics

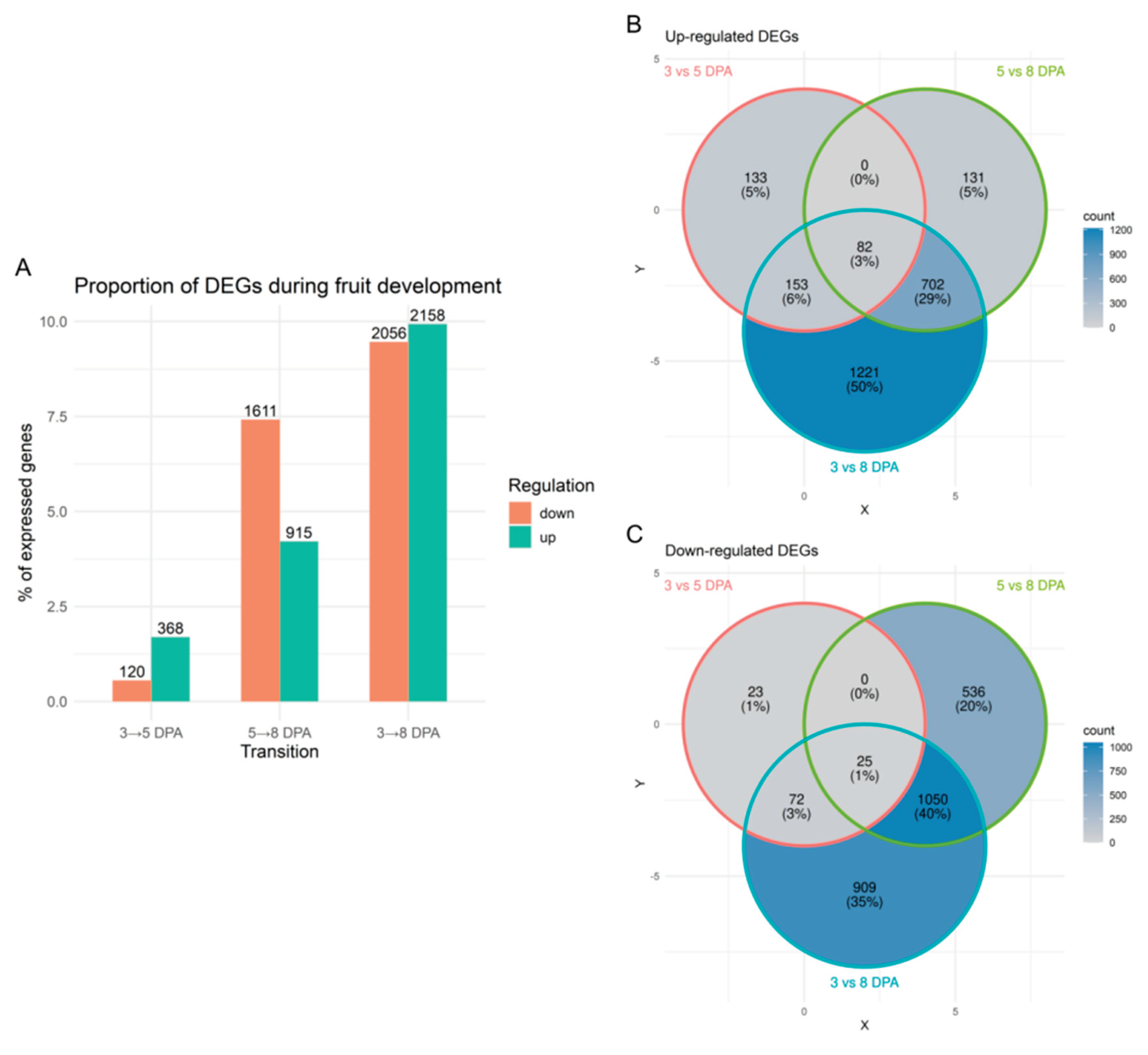

2.2. Differential Expression Shows Stage-Specific Transcriptional Changes

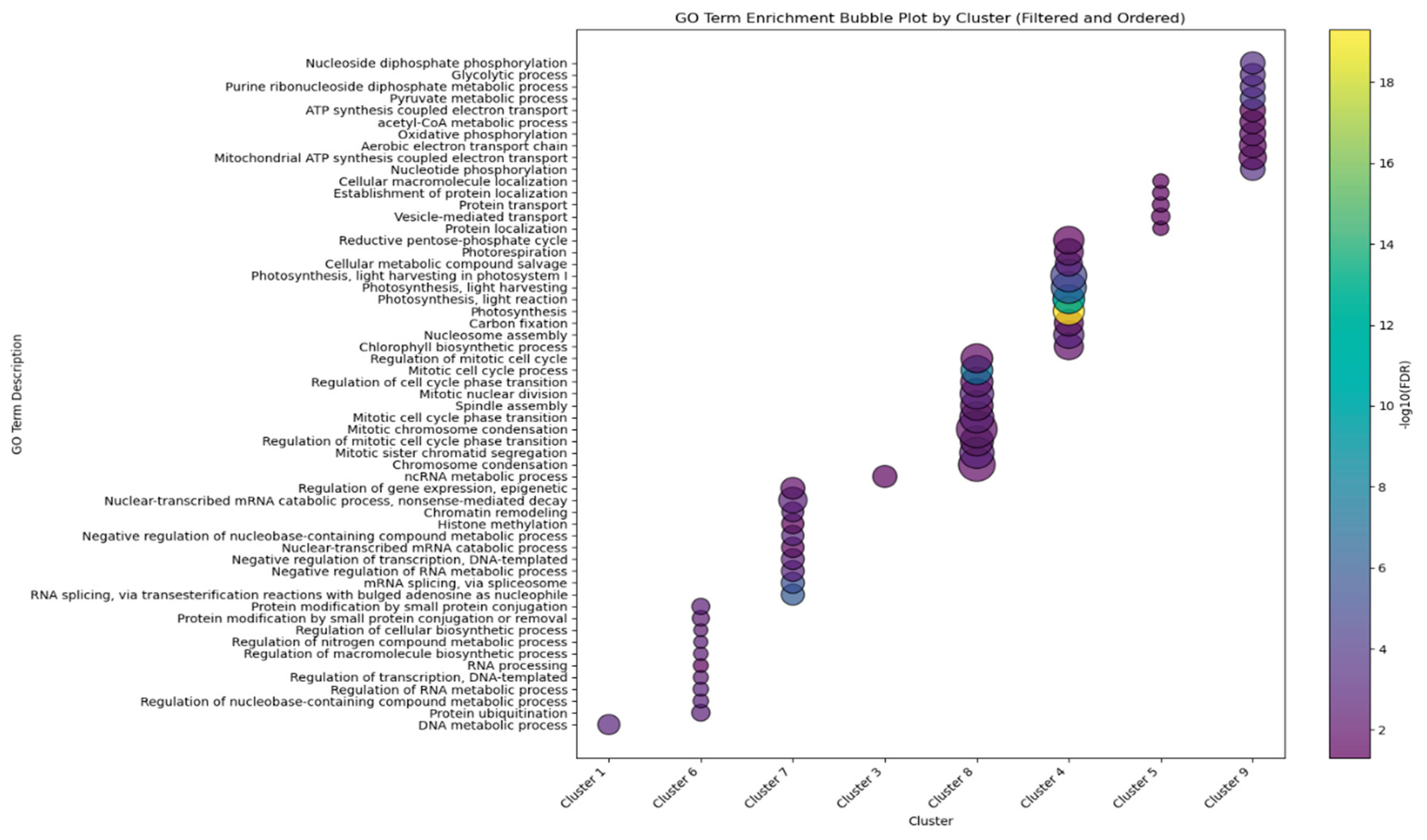

2.3. Distinct Expression Clusters Mark Developmental Transitions

- Figure 4. Heatmap and predicted interaction network of cell cycle–related genes from cluster 8. A- Heatmap showing the expression profiles of 50 cell cycle related genes from cluster 8 across the three developmental stages. Gene symbols are provided in parentheses for annotated genes The heatmap was generated using the Morpheus tool (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus). B- Predicted protein–protein interaction network based on conserved interactions from homologs in other organisms, as retrieved from the STRING database. Line thickness represents the strength of evidence supporting each interaction.

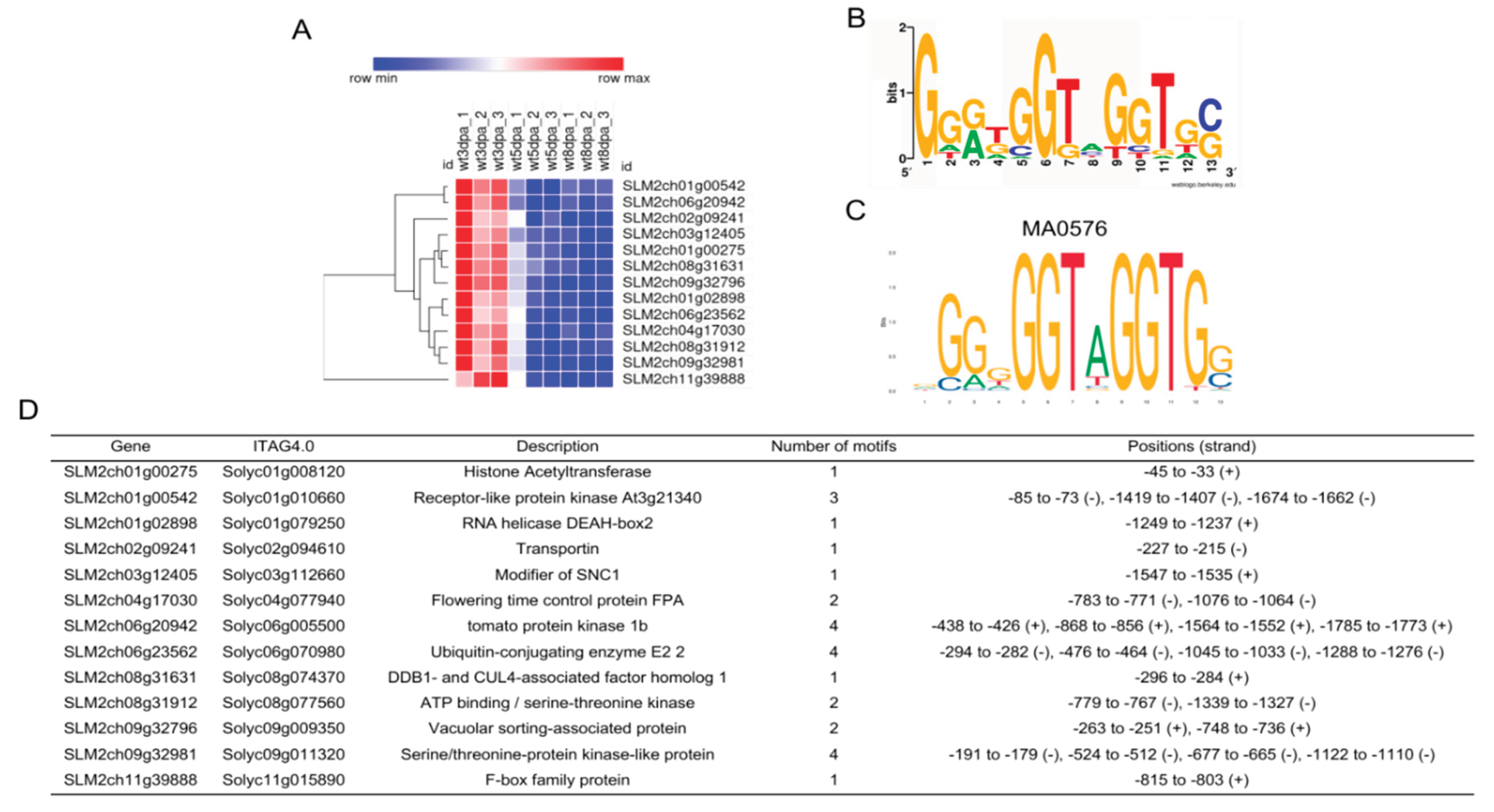

2.4. Different Transcription Factors May Regulate Early Fruit Development

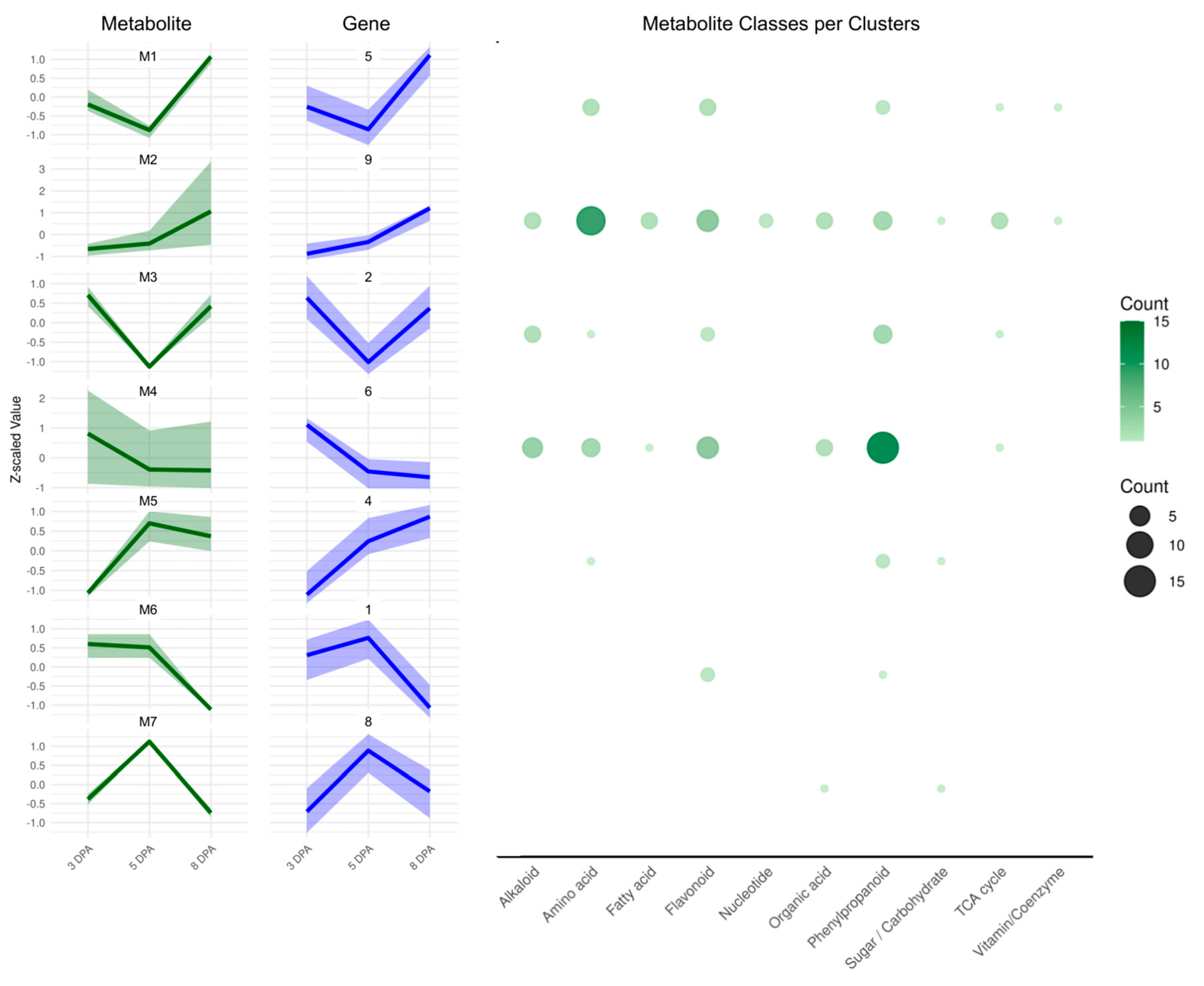

2.5. Integration of Metabolite Clusters with Gene Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. RNA Sequencing

4.2. Read Mapping and Transcript Quantification

4.3. Differential Expression Analysis

4.4. Expression Clustering

4.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.6. Transcription Factor Prediction and Analysis

4.7. Transcription Factor Motif Mapping and Enrichment Analysis

4.8. Integration of Metabolomics Data

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Musseau, C.; Just, D.; Jorly, J.; Gévaudant, F.; Moing, A.; Chevalier, C.; Lemaire-Chamley, M.; Rothan, C.; Fernandez, L. Identification of Two New Mechanisms That Regulate Fruit Growth by Cell Expansion in Tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauxion, J.-P.; Chevalier, C.; Gonzalez, N. Complex Cellular and Molecular Events Determining Fruit Size. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 1023–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, M.A.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Tao, J.; Ge, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gai, W.; Dong, H.; Zhang, Y. Altered Brassinolide Sensitivity1 Regulates Fruit Size in Association with Phytohormones Modulation in Tomato. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrani, J.C.; Sanjuán, R.; Ruiz-Rivero, O.; Fos, M.; García-Martínez, J.L. Gibberellin Regulation of Fruit Set and Growth in Tomato. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki, Y.; Hao, S.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Ozeki-Iida, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Fei, Z.; Zhong, S.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Rose, J.K.C.; et al. Ethylene Suppresses Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) Fruit Set through Modification of Gibberellin Metabolism. Plant J.: Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 83, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Y.-L.; Patrick, J.W.; Bouzayen, M.; Osorio, S.; Fernie, A.R. Molecular Regulation of Seed and Fruit Set. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldet, P.; Hernould, M.; Laporte, F.; Mounet, F.; Just, D.; Mouras, A.; Chevalier, C.; Rothan, C. The Expression of Cell Proliferation-Related Genes in Early Developing Flowers Is Affected by a Fruit Load Reduction in Tomato Plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Radovich, C.; Welty, N.; Hsu, J.; Li, D.; Meulia, T.; van der Knaap, E. Integration of Tomato Reproductive Developmental Landmarks and Expression Profiles, and the Effect of SUN on Fruit Shape. BMC Plant Biol. 2009, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L.; Figueroa, C.R.; Valdenegro, M. Recent Advances in Hormonal Regulation and Cross-Talk during Non-Climacteric Fruit Development and Ripening. Horticulturae 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; He, Y.; Yan, S.; Sun, Z.; Cai, R.; Zhang, Y. Histological, Transcriptomic, and Gene Functional Analyses Reveal the Regulatory Events Underlying Gibberellin-Induced Parthenocarpy in Tomato. Hortic. Plant J. 2024, 10, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Knaap, E.; Chakrabarti, M.; Chu, Y.H.; Clevenger, J.P.; Illa-Berenguer, E.; Huang, Z.; Keyhaninejad, N.; Mu, Q.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. What Lies beyond the Eye: The Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Tomato Fruit Weight and Shape. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Nicolás, E.; Montero-Pau, J.; Gimeno-Paez, E.; Garcia-Carpintero, V.; Ziarsolo, P.; Menda, N.; Mueller, L.A.; Blanca, J.; Cañizares, J.; van der Knaap, E.; et al. Exploiting the Diversity of Tomato: The Development of a Phenotypically and Genetically Detailed Germplasm Collection. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, K.; Du, Y.; Gu, L.; Cui, X. Spatiotemporal Transcriptome Provides Insights into Early Fruit Development of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissner, R.; Jacobson, Y.; Melamed, S.; Levyatuv, S.; Shalev, G.; Ashri, A.; Elkind, Y.; Levy, A. A New Model System for Tomato Genetics. Plant J. 1997, 12, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukura, C.; Aoki, K.; Fukuda, N.; Mizoguchi, T.; Asamizu, E.; Saito, T.; Shibata, D.; Ezura, H. Comprehensive Resources for Tomato Functional Genomics Based on the Miniature Model Tomato Micro-Tom. Curr. Genomics 2008, 9, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.L.T.; Nguyen, C.V.; Hill, T.; Cheng, K.L.; Figueroa-Balderas, R.; Aktas, H.; Ashrafi, H.; Pons, C.; Fernández-Muñoz, R.; Vicente, A.; et al. Uniform Ripening Encodes a Golden 2-like Transcription Factor Regulating Tomato Fruit Chloroplast Development. Science 2012, 336, 1711–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaki, H.; Shirasawa, K.; Hoshikawa, K.; Isobe, S.; Ezura, H.; Aoki, K.; Hirakawa, H. Genomic Variation across Distribution of Micro-Tom, a Model Cultivar of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum). DNA Res. 2024, 31, dsae016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasawa, K.; Ariizumi, T. Near-Complete Genome Assembly of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum) Cultivar Micro-Tom. Plant Biotechnol. 2024. advpub. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matas, A.J.; Yeats, T.H.; Buda, G.J.; Zheng, Y.; Chatterjee, S.; Tohge, T.; Ponnala, L.; Adato, A.; Aharoni, A.; Stark, R.; et al. Tissue- and Cell-Type Specific Transcriptome Profiling of Expanding Tomato Fruit Provides Insights into Metabolic and Regulatory Specialization and Cuticle Formation. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3893–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Tabata, S.; Hirakawa, H.; Asamizu, E.; Shirasawa, K.; Isobe, S.; Kaneko, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Shibata, D.; Aoki, K.; et al. The Tomato Genome Sequence Provides Insights into Fleshy Fruit Evolution. Nat. 2012 485:7400 2012, 485, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tao, X.; Li, L.; Mao, L.; Luo, Z.; Khan, Z.U.; Ying, T. Comprehensive RNA-Seq Analysis on the Regulation of Tomato Ripening by Exogenous Auxin. PLOS One 2016, 11, e0156453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitalo, O.W.; Kang, S.W.; Tran, L.T.; Kubo, Y.; Ariizumi, T.; Ezura, H. Transcriptomic Analysis in Tomato Fruit Reveals Divergences in Genes Involved in Cold Stress Response and Fruit Ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Li, F.; Ding, J.; Fu, X.; Shang, J.; Kong, X.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, X. Comparative RNA-Seq Analysis of Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Provides Insights into Natural and Postharvest Ripening. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 216, 113079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, P.; Shinozaki, Y.; Powell, A.; Philippe, G.; Snyder, S.I.; Bao, K.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Courtney, L.; Vrebalov, J.; et al. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Tomato Fruit Transcriptome under Prolonged Water Stress. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2557–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurgeirsson, B.; Emanuelsson, O.; Lundeberg, J. Sequencing Degraded RNA Addressed by 3’ Tag Counting. PLOS One 2014, 9, e91851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, P.N.; de Souza, L.P.; Ferreira, P.B.; Mauxion, J.P.; da Silva, L.F.C.; Chang, A.I.; Saleme, M. de L.S.; Zhu, F.; García, S.S.; De Beukelaer, H.; et al. Modulating the Activity of the APC/C Regulator SISAMBA Improves the Sugar and Antioxidant Content of Tomato Fruits. Plant Biotechnology Journal n/a. [CrossRef]

- Riou-Khamlichi, C.; Menges, M.; Healy, J.M.; Murray, J.A. Sugar Control of the Plant Cell Cycle: Differential Regulation of Arabidopsis D-Type Cyclin Gene Expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 4513–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Sun, X.; Liu, L. Action of Salicylic Acid on Plant Growth. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrequieta, A.; Ferraro, G.; Boggio, S.B.; Valle, E.M. Free Amino Acid Production during Tomato Fruit Ripening: A Focus on L-Glutamate. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Dong, L.; Kandel, S.L.; Jiao, Y.; Shi, L.; Yang, Y.; Shi, A.; Mou, B. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis Provides Insights into the Fruit Quality and Yield Improvement in Tomato under Soilless Substrate-Based Cultivation. Agronomy 2022, 12, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, W. RSeQC: Quality Control of RNA-Seq Experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2184–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinform. (oxf. Engl.) 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; Oshlack, A. A Scaling Normalization Method for Differential Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Nishiyama, T.; Shimizu, K.; Kadota, K. TCC: An R Package for Comparing Tag Count Data with Robust Normalization Strategies. BMC Bioinf. 2013, 14, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING Database in 2023: Protein-Protein Association Networks and Functional Enrichment Analyses for Any Sequenced Genome of Interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Hu, E.; Cai, Y.; Xie, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhan, L.; Tang, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Wang, R.; et al. Using clusterProfiler to Characterize Multiomics Data. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 3292–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Yang, D.-C.; Meng, Y.-Q.; Jin, J.; Gao, G. PlantRegMap: Charting Functional Regulatory Maps in Plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D1104–D1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Silva, F.; Peer, Y.V. de Planttfhunter: Identification and Classification of Plant Transcription Factors. 2023.

- Gryffroy, L.; Ceulemans, E.; Manosalva Pérez, N.; Venegas-Molina, J.; Jaramillo-Madrid, A.C.; Rodrigues, S.D.; De Milde, L.; Jonckheere, V.; Van Montagu, M.; De Coninck, B.; et al. Rhizogenic Agrobacterium Protein RolB Interacts with the TOPLESS Repressor Proteins to Reprogram Plant Immunity and Development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023, 120, e2210300120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirauch, M.T.; Yang, A.; Albu, M.; Cote, A.G.; Montenegro-Montero, A.; Drewe, P.; Najafabadi, H.S.; Lambert, S.A.; Mann, I.; Cook, K.; et al. Determination and Inference of Eukaryotic Transcription Factor Sequence Specificity. Cell 2014, 158, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Mondragon, J.A.; Riudavets-Puig, R.; Rauluseviciute, I.; Berhanu Lemma, R.; Turchi, L.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Lucas, J.; Boddie, P.; Khan, A.; Manosalva Pérez, N.; et al. JASPAR 2022: The 9th Release of the Open-Access Database of Transcription Factor Binding Profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D165–D173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C.E.; Bailey, T.L.; Noble, W.S. FIMO: Scanning for Occurrences of a given Motif. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1017–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Raw read pairs | Clean read pairs | Q30 % (Before) | Q30 % (After) | Uniquely mapped % | Multi-mapping % | Unmapped % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DPA_R1 | 38108973 | 33199719 | 91.49 | 94.61 | 90.86 | 4.69 | 4.44 |

| 3DPA_R2 | 36774120 | 30619852 | 91.42 | 94.76 | 92.44 | 4.21 | 3.34 |

| 3DPA_R3 | 43253948 | 33210737 | 90.26 | 95.03 | 92.41 | 4.26 | 3.33 |

| 5DPA_R1 | 36012854 | 28486863 | 91.16 | 95.10 | 92.21 | 4.56 | 3.22 |

| 5DPA_R2 | 39869504 | 32194417 | 89.80 | 94.76 | 90.62 | 4.49 | 4.90 |

| 5DPA_R3 | 35938412 | 28865298 | 90.46 | 94.79 | 90.37 | 4.49 | 5.14 |

| 8DPA_R1 | 38193796 | 32379259 | 91.89 | 94.91 | 92.76 | 4.46 | 2.78 |

| 8DPA_R2 | 38321852 | 27953423 | 89.58 | 95.05 | 91.90 | 4.69 | 3.41 |

| 8DPA_R3 | 35581593 | 28852087 | 90.92 | 94.67 | 92.78 | 4.59 | 2.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).