Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The motivation and rationale for collaborative learning, with an emphasis on application scenarios and system constraints [10].

- A taxonomy of collaborative learning frameworks, including split learning, federated learning, and knowledge distillation, and their adaptations for heterogeneous model collaboration.

- Technical challenges inherent to collaborative learning, such as latency, energy consumption, model heterogeneity, and security, along with potential mitigation strategies.

- An overview of real-world systems and platforms that support collaborative learning, including hardware, software, and network considerations.

- Open research questions and future directions, including the role of foundation models, personalized learning, adaptive collaboration strategies, and standardization efforts [11].

2. Problem Formulation

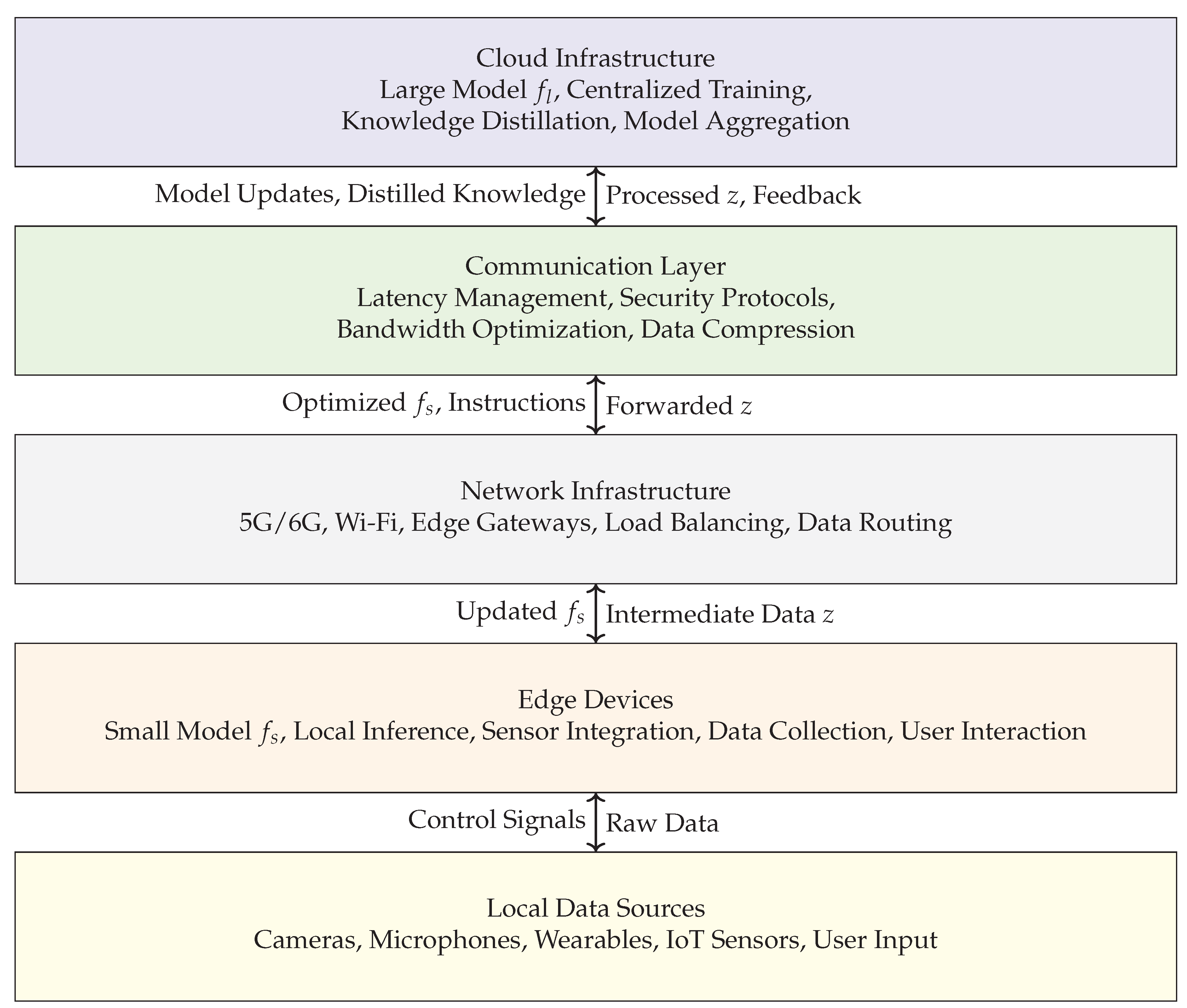

3. System Architecture

4. Comparison of Collaborative Learning Paradigms

5. Challenges and Research Opportunities

6. Applications and Case Studies

7. Future Directions and Emerging Trends

8. Conclusions

References

- Don-Yehiya, S.; Venezian, E.; Raffel, C.; Slonim, N.; Choshen, L. ColD Fusion: Collaborative Descent for Distributed Multitask Finetuning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Rogers, A.; Boyd-Graber, J.; Okazaki, N., Eds., Toronto, Canada, 2023; pp. 788–806. [CrossRef]

- Givón, T. Verb serialization in Tok Pisin and Kalam: A comparative study of temporal packaging. Melanesian Pidgin and Tok Pisin 1990, 19–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, M.J. Computational Complexity of Machine Learning. PhD thesis, Department of Computer Science, Harvard University, 1989.

- Lee, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, J.; Shin, D.; Han, D.; Yoo, H.J. The hardware and algorithm co-design for energy-efficient DNN processor on edge/mobile devices. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2020, 67, 3458–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barisin, T.; Horenko, I. On entropic sparsification of neural networks. Pattern Recognition Letters 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, T.; Schütze, H. It’s Not Just Size That Matters: Small Language Models Are Also Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Langer, M.; He, Z.; Rahayu, W.; Xue, Y. Distributed training of deep learning models: A taxonomic perspective. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2020, 31, 2802–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomron, G.; Gabbay, F.; Kurzum, S.; Weiser, U. Post-training sparsity-aware quantization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 17737–17748. [Google Scholar]

- Niven, T.; Kao, H.Y. Probing Neural Network Comprehension of Natural Language Arguments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019, pp. 4658–4664.

- Shrotri, A.A.; Narodytska, N.; Ignatiev, A.; Meel, K.S.; Marques-Silva, J.; Vardi, M.Y. Constraint-driven explanations for black-box ML models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022, Vol. 36, pp. 8304–8314.

- Author, N.N. Suppressed for Anonymity, 2021.

- Nalisnick, E.; Smyth, P. Stick-breaking variational autoencoders. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hayou, S.; Ton, J.F.; Doucet, A.; Teh, Y.W. Robust pruning at initialization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.08797. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. BFP: Balanced Filter Pruning via Knowledge Distillation for Efficient Deployment of CNNs on Edge Devices. Neurocomputing 2025, 130946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansare, N.; Katukuri, J.; Arora, A.; Cipollone, F.; Shaik, R.; Tokgozoglu, N.; Venkataraman, C. Learning compressed embeddings for on-device inference. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2022, 4, 382–397. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Sparsert: Accelerating unstructured sparsity on gpus for deep learning inference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM international conference on parallel architectures and compilation techniques, 2020, pp. 31–42.

- Durbin, J. airoboros: Customizable implementation of the self-instruct paper. https://github.com/jondurbin/airoboros, 2024.

- Wang, H.; Sayadi, H.; Mohsenin, T.; Zhao, L.; Sasan, A.; Rafatirad, S.; Homayoun, H. Mitigating cache-based side-channel attacks through randomization: A comprehensive system and architecture level analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1414–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, M.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.; Liu, B.; Wang, F.; Chen, Z. Fine-grained hierarchical singular value decomposition for convolutional neural networks compression and acceleration. Neurocomputing 2025, 636, 129966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Bohlender, B.; Viehmann, C.; Hane, V.; Adamson, Y.; Khuri, J.; Brossmann, J.; Pfeiffer, J.; Gurevych, I. Adapterhub playground: Simple and flexible few-shot learning with adapters. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.08103. [Google Scholar]

- Passalis, N.; Raitoharju, J.; Tefas, A.; Gabbouj, M. Efficient adaptive inference for deep convolutional neural networks using hierarchical early exits. Pattern Recognition 2020, 105, 107346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xiang, W. X-pruner: explainable pruning for vision transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2023, pp. 24355–24363.

- Aribandi, V.; Tay, Y.; Schuster, T.; Rao, J.; Zheng, H.S.; Mehta, S.V.; Zhuang, H.; Tran, V.Q.; Bahri, D.; Ni, J.; et al. ExT5: Towards Extreme Multi-Task Scaling for Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Gan, L.; Wang, G.; Hu, Y.; Shen, T.; Yang, H.; Kuang, K.; Wu, F. Retrieval-Augmented Mixture of LoRA Experts for Uploadable Machine Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.16989. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.; Binici, K.; Mitra, T. Chameleon: Dual memory replay for online continual learning on edge devices. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Simonyan, K.; Yang, Y. Darts: Differentiable architecture search. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.09055. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, W.J.; Meyer, B.H.; Ardakani, A. Hardware-aware design for edge intelligence. IEEE Open Journal of Circuits and Systems 2020, 2, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkerdawy, S.; Elhoushi, M.; Singh, A.; Zhang, H.; Ray, N. One-shot layer-wise accuracy approximation for layer pruning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE; 2020; pp. 2940–2944. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Pappas, N.; Yogatama, D.; Schwartz, R.; Smith, N.; Kong, L. Random Feature Attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Liu, Q.; Lin, B.Y.; Pang, T.; Du, C.; Lin, M. LoraHub: Efficient Cross-Task Generalization via Dynamic LoRA Composition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2307.13269. [Google Scholar]

- Gadosey, P.K.; Li, Y.; Yamak, P.T. On pruned, quantized and compact cnn architectures for vision applications: an empirical study. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Information Processing and Cloud Computing, 2019, pp. 1–8.

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial intelligence and statistics. PMLR; 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, R.S.; Carbonell, J.G.; Mitchell, T.M. (Eds.) Machine Learning: An Artificial Intelligence Approach, Vol. I; Tioga: Palo Alto, CA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Van Hoof, H. Model-based meta reinforcement learning using graph structured surrogate models and amortized policy search. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2022; pp. 23055–23077. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, A.; Ponti, E.M.; Pfeiffer, J.; Ruder, S.; Glavaš, G.; Vulić, I.; Korhonen, A. MAD-G: Multilingual Adapter Generation for Efficient Cross-Lingual Transfer. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, 2021, 4762–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep learning; Vol. 1, MIT Press, 2016.

- Zhu, Y.; Peng, H.; Fu, A.; Yang, W.; Ma, H.; Al-Sarawi, S.F.; Abbott, D.; Gao, Y. Towards robustness evaluation of backdoor defense on quantized deep learning models. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 255, 124599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workshop, B.; Scao, T.L.; Fan, A.; Akiki, C.; Pavlick, E.; Ilić, S.; Hesslow, D.; Castagné, R.; Luccioni, A.S.; Yvon, F.; et al. BLOOM: A 176b-parameter open-access multilingual language model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.05100. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Shao, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, P.; Yan, H.; Qiu, X.; Huang, X. Learning sparse sharing architectures for multiple tasks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, Vol.

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, M.; Li, P.; Li, R.; Xiong, N.N. An adaptive federated learning scheme with differential privacy preserving. Future Generation Computer Systems 2022, 127, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.; Fournarakis, M.; Bondarenko, Y.; Blankevoort, T. Overcoming oscillations in quantization-aware training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2022; pp. 16318–16330. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier-Boisvert, M.; Bahdanau, D.; Lahlou, S.; Willems, L.; Saharia, C.; Nguyen, T.H.; Bengio, Y. BabyAI: First Steps Towards Grounded Language Learning With a Human In the Loop. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. LlamaIndex, a data framework for your LLM applications. https://github.com/run-llama/llama_index, 2024.

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stich, S.U. Local SGD converges fast and communicates little. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1805.09767. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyat, M.; Nadeem, T.; Krawczyk, B. ClassyNet: Class-Aware Early Exit Neural Networks for Edge Devices. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.; Nguyen, V.; Zohren, S.; Roberts, S. Hierarchical Indian Buffet Neural Networks for Bayesian Continual Learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.02290. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, A.; Rosenbloom, P.S. Mechanisms of Skill Acquisition and the Law of Practice. In Cognitive Skills and Their Acquisition; Anderson, J.R., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gim, I.; Ko, J. Memory-efficient DNN training on mobile devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, 2022, pp. 464–476.

- Chronopoulou, A.; Pfeiffer, J.; Maynez, J.; Wang, X.; Ruder, S.; Agrawal, P. Language and Task Arithmetic with Parameter-Efficient Layers for Zero-Shot Summarization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.09344. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, E.; Strub, F.; De Vries, H.; Dumoulin, V.; Courville, A. FiLM: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018, Vol. 32.

- Bengio, Y.; LeCun, Y. Scaling Learning Algorithms Towards AI. In Large Scale Kernel Machines; MIT Press, 2007.

- Zhong, Z.; Bao, W.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X. Flee: A hierarchical federated learning framework for distributed deep neural network over cloud, edge, and end device. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 2022, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhovich, A.; Tax, D.M.; Sluiter, M.H.; Bessa, M.A. Continual prune-and-select: class-incremental learning with specialized subnetworks. Applied Intelligence 2023, 53, 17849–17864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tsvetkov, Y.; Firat, O.; Cao, Y. Gradient Vaccine: Investigating and Improving Multi-task Optimization in Massively Multilingual Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Ji, S.; Xiong, H.; Dou, D. From distributed machine learning to federated learning: A survey. Knowledge and Information Systems 2022, 64, 885–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, S. Efficient on-device models using neural projections. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 5370–5379. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, J.; Prasanna, P.; Ravindran, B.; Khapra, M.M. Attend, Adapt and Transfer: Attentive Deep Architecture for Adaptive Transfer from multiple sources in the same domain. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Wallace, E.; Feng, S.; Klein, D.; Singh, S. Calibrate Before Use: Improving Few-shot Performance of Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; Meila, M.; Zhang, T., Eds. PMLR, 18–24 Jul 2021, Vol. 139, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 12697–12706.

- Zhou, H.; Lan, J.; Liu, R.; Yosinski, J. Deconstructing lottery tickets: Zeros, signs, and the supermask. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2019; pp. 3597–3607. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhou, M. EnsLM: Ensemble language model for data diversity by semantic clustering. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2021, pp. 2954–2967.

- Velliangiri, S.; Alagumuthukrishnan, S.; et al. A review of dimensionality reduction techniques for efficient computation. Procedia Computer Science 2019, 165, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzidi, H.; Odema, M.; Ouarnoughi, H.; Al Faruque, M.A.; Niar, S. HADAS: Hardware-aware dynamic neural architecture search for edge performance scaling. In Proceedings of the 2023 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). IEEE; 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, J. Resource-constrained edge ai with early exit prediction. Journal of Communications and Information Networks 2022, 7, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mishra, S.; Alipoormolabashi, P.; Kordi, Y.; Mirzaei, A.; Arunkumar, A.; Ashok, A.; Dhanasekaran, A.S.; Naik, A.; Stap, D.; et al. Benchmarking Generalization via In-Context Instructions on 1,600+ Language Tasks, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Standley, T.; Zamir, A.; Chen, D.; Guibas, L.; Malik, J.; Savarese, S. Which tasks should be learned together in multi-task learning? In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 9120–9132. [Google Scholar]

- Bingel, J.; Søgaard, A. Identifying beneficial task relations for multi-task learning in deep neural networks. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Friedman, D.; Chen, D. Factual Probing Is [MASK]: Learning vs. Learning to Recall. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Gururangan, S.; Dettmers, T.; Lewis, M.; Althoff, T.; Smith, N.A.; Zettlemoyer, L. Branch-train-merge: Embarrassingly parallel training of expert language models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.03306. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarevich, I.; Kozlov, A.; Malinin, N. Post-training deep neural network pruning via layer-wise calibration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 798–805.

- Hui, D.Y.T.; Chevalier-Boisvert, M.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. BabyAI 1.1. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Qin, Y.; Yang, G.; Wei, F.; Yang, Z.; Su, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, Y.; Chan, C.M.; Chen, W.; et al. Delta tuning: A comprehensive study of parameter efficient methods for pre-trained language models. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S. Temporal credit assignment in reinforcement learning. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 1984.

- Guo, X.; Wang, W.S.; Zhang, J.; Gong, L.S. An Online Growing-and-Pruning Algorithm of a Feedforward Neural Network for Nonlinear Systems Modeling. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.; Wang, T.; Munkhdalai, T.; Sordoni, A.; Trischler, A.; Mattarella-Micke, A.; Maji, S.; Iyyer, M. Exploring and predicting transferability across NLP tasks. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yu, D.; Zou, Y.; Yu, J.; Cheng, X. Decentralized wireless federated learning with differential privacy. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2022, 18, 6273–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Fan, C.; Wei, W.; Qu, X.; Chen, D.; Cheng, Y. Twin-Merging: Dynamic Integration of Modular Expertise in Model Merging. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.15479. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P.; Cowhey, I.; Etzioni, O.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A.; Schoenick, C.; Tafjord, O. Think you have solved question answering? try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ran, X. Deep learning with edge computing: A review. Proceedings of the IEEE 2019, 107, 1655–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccia, L.; Ponti, E.; Su, Z.; Pereira, M.; Roux, N.L.; Sordoni, A. Multi-Head Adapter Routing for Cross-Task Generalization. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2211.03831. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, S.; Swany, M. ScaDLES: Scalable Deep Learning over Streaming data at the Edge. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE; 2022; pp. 2113–2122. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, D.; Luo, J.; Fu, X.; Chen, G.; Xu, Z.; King, I. A survey of trustworthy federated learning: Issues, solutions, and challenges. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2024, 15, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, V.E.; Braeken, A.; Segers, L.; Silva, B.d. Secure Tiny Machine Learning on Edge Devices: A Lightweight Dual Attestation Mechanism for Machine Learning. Future Internet 2025, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Kim, D.; Jang, J.; Shin, J.; Seo, M. Guess the Instruction! Flipped Learning Makes Language Models Stronger Zero-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, T.; Mishra, V.; Goswami, A.; Sarangapani, J. A comprehensive survey on model compression and acceleration. Artificial Intelligence Review 2020, 53, 5113–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragman, F.J.; Tanno, R.; Ourselin, S.; Alexander, D.C.; Cardoso, J. Stochastic filter groups for multi-task cnns: Learning specialist and generalist convolution kernels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2019, pp. 1385–1394.

- Qin, C.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y. Slow learning and fast inference: Efficient graph similarity computation via knowledge distillation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 14110–14121. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-bert: Sentence embeddings using siamese bert-networks. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, Y.W.; Görür, D.; Ghahramani, Z. Stick-breaking Construction for the Indian Buffet Process. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS 2007); 2007; pp. 556–563. [Google Scholar]

- Bourechak, A.; Zedadra, O.; Kouahla, M.N.; Guerrieri, A.; Seridi, H.; Fortino, G. At the confluence of artificial intelligence and edge computing in iot-based applications: A review and new perspectives. Sensors 2023, 23, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, M.; Jin, C.; Dong, X.; Yuan, J.; Jin, X.; Huang, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Melon: Breaking the memory wall for resource-efficient on-device machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, 2022, pp. 450–463.

- Goyal, A.; Lamb, A.; Gampa, P.; Beaudoin, P.; Levine, S.; Blundell, C.; Bengio, Y.; Mozer, M. Object files and schemata: Factorizing declarative and procedural knowledge in dynamical systems. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Luo, J.; Wang, F.; Peng, C.; Fan, P.; Letaief, K.B. Fedlp: Layer-wise pruning mechanism for communication-computation efficient federated learning. In Proceedings of the ICC 2023-IEEE International Conference on Communications. IEEE; 2023; pp. 1250–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney, C.; Li, X.; Yan, Y.; Zong, Z. Parallel blockwise knowledge distillation for deep neural network compression. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2020, 32, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Ouyang, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W. Mixed-precision neural network quantization via learned layer-wise importance. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer; 2022; pp. 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Tam, D.; Muqeeth, M.; Mohta, J.; Huang, T.; Bansal, M.; Raffel, C. Few-Shot Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning is Better and Cheaper than In-Context Learning, 2022.

- Shi, Y.; Yuan, L.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J. Continual learning via bit-level information preserving. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 16674–16683.

- Sung, Y.L.; Nair, V.; Raffel, C. Training Neural Networks with Fixed Sparse Masks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Beygelzimer, A.; Dauphin, Y.; Liang, P.; Vaughan, J.W., Eds. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clune, J.; Mouret, J.B.; Lipson, H. The evolutionary origins of modularity. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological sciences 2013, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhbaatar, S.; Golovneva, O.; Sharma, V.; Xu, H.; Lin, X.V.; Rozière, B.; Kahn, J.; Li, D.; Yih, W.t.; Weston, J.; et al. Branch-Train-MiX: Mixing Expert LLMs into a Mixture-of-Experts LLM. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07816. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, P.L.; Harb, J.; Precup, D. The option-critic architecture. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2017, Vol. 31.

- Ha, D.; Dai, A.; Le, Q.V. HyperNetworks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dun, C.; Garcia, M.H.; Zheng, G.; Awadallah, A.H.; Sim, R.; Kyrillidis, A.; Dimitriadis, D. FedJETs: Efficient Just-In-Time Personalization with Federated Mixture of Experts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.08586. [Google Scholar]

| Aspect | Split Learning | Federated Learning | Knowledge Distillation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Partitioning | Model is split between edge and cloud at an intermediate layer | Full model resides on each edge device; no split | Small model on device, large teacher in cloud |

| Data Locality | Raw data stays on edge; only intermediate activations sent | Raw data stays on edge; only model updates sent | Raw data may stay on edge; soft labels or logits exchanged |

| Communication Pattern | Frequent bidirectional transfer of activations and gradients per sample/batch | Periodic upload of model updates; occasional downloads | Irregular transfer of predictions or distilled knowledge |

| Privacy Preservation | Moderate; activations may leak some data | High; only updates transmitted | Variable; depends on distillation method used |

| Edge Computation Load | Low to moderate; partial forward/backward pass | High; full training/inference on device | Low; primarily forward pass |

| Cloud Computation Load | High; completes forward/backward pass for each sample | Low to moderate; model aggregation or central training | High; teacher model training and distillation |

| Latency Sensitivity | High; real-time communication needed for inference/training | Low to moderate; training is asynchronous | Low; distillation can be scheduled flexibly |

| Typical Use Cases | Real-time inference, privacy-sensitive settings | Large-scale collaborative training, personalization | Model compression, continual learning, personalization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).