Submitted:

04 August 2025

Posted:

05 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

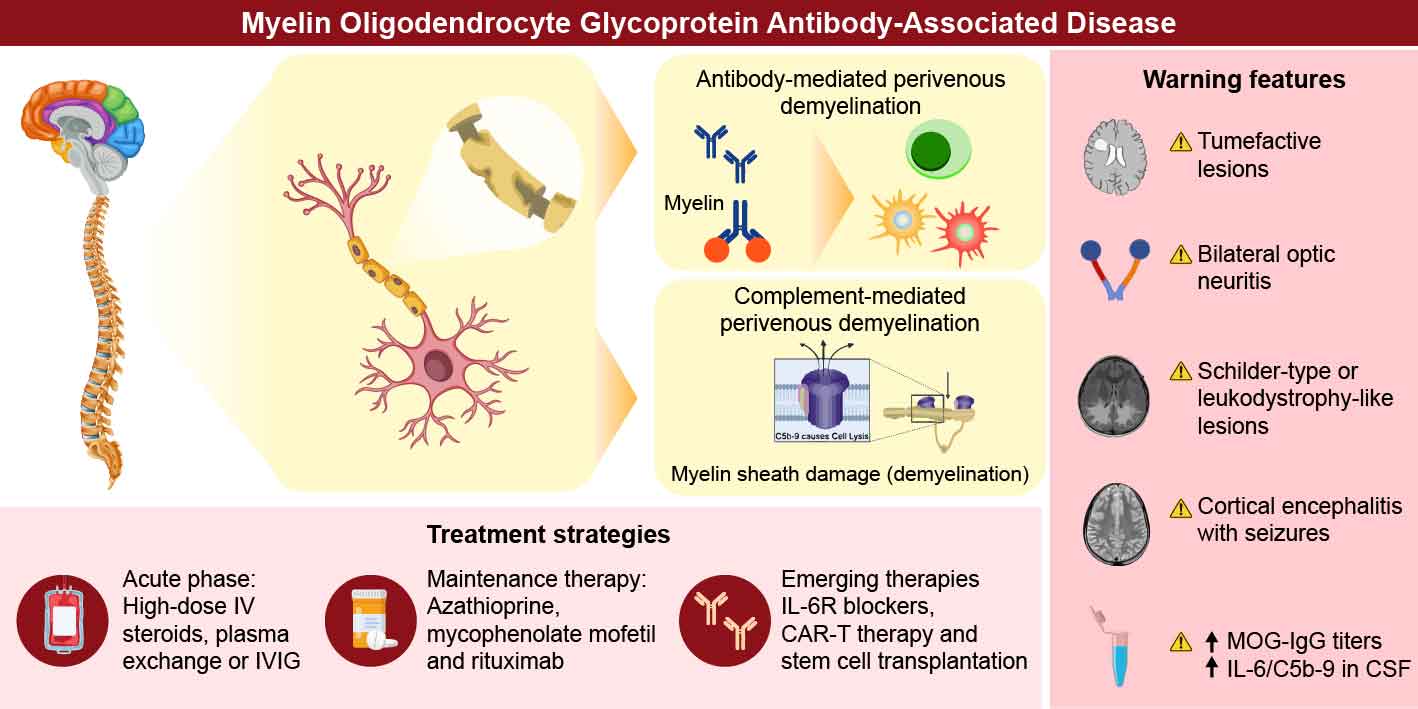

2. Pathological Insights

2.1. Pathological Features of MOGAD

2.2. Complement-Mediated

2.3. Antibody-Mediated

3. Clinical Features of MOGAD

- (1)

- Red flags for severe MOGAD

3.1. Transverse Myelitis

3.2. Optic Neuritis

3.3. Encephalopathy and Seizures

- (2)

- Clinical indicators of refractory activity

4. MRI and Other Biomarkers Predicting Severity

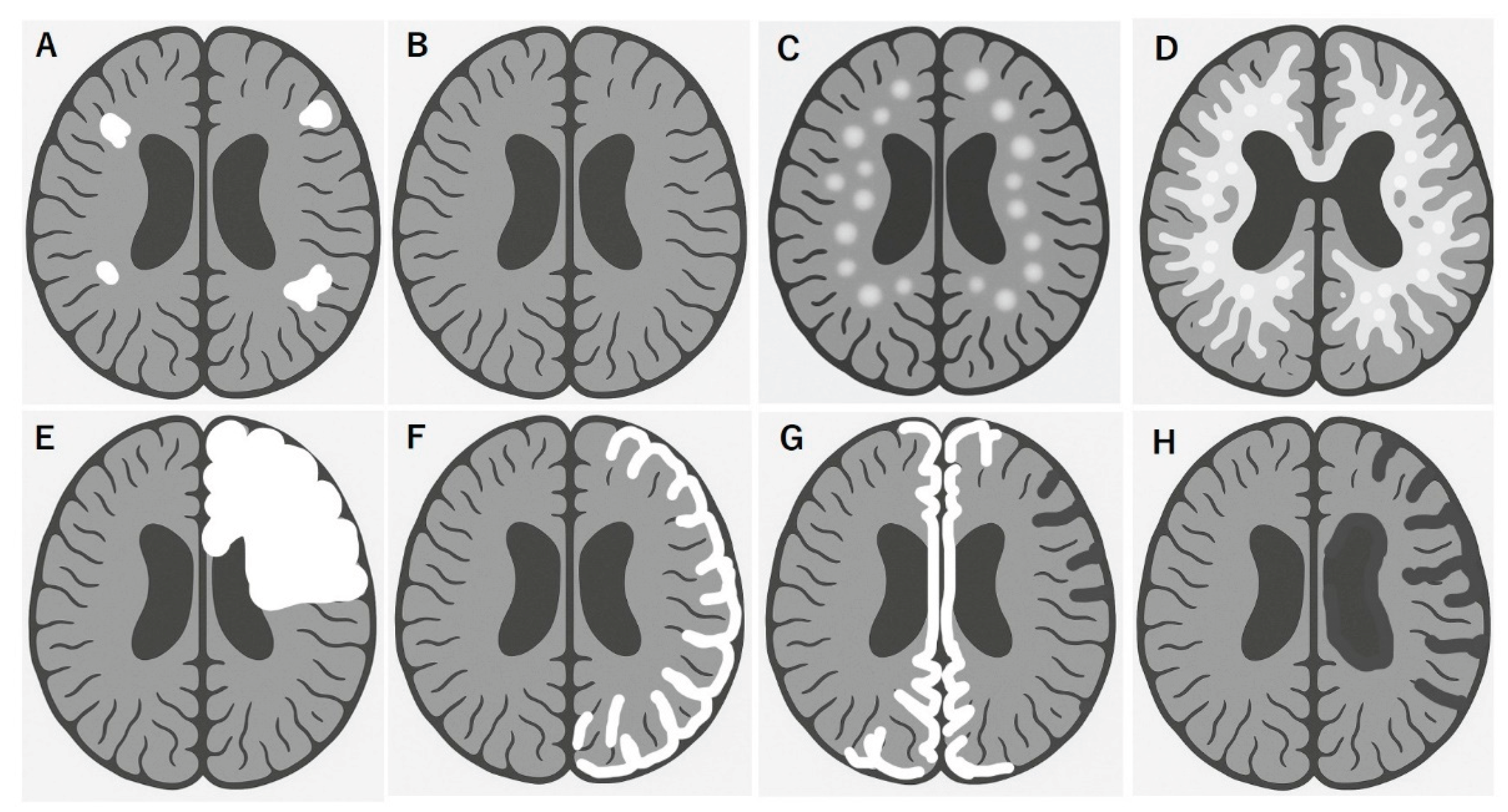

4.1. Typical MRI Features

4.2. MRI Features Predicting Severe and Refractory MOGAD

4.3. Biomarkers Predicting Severe and Refractory MOGAD

- Serum and CSF cytokine and chemokine profiles, such as elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) [85,86,87], IL-8 [86,87] , and B-cell activating factor (BAFF) [87] levels, reflect active B-cell-mediated inflammation and predict the need for aggressive therapy [85,86,87,88], associated with disease severity in general, of which BAFF levels predicted lower risk of relapse [89]

5. MOGAD Treatment

- (1)

- Acute-phase treatments

- (2)

- Maintenance therapy

- (3)

- Emerging therapies in clinical trials and others

- (4)

- Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell Therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

6. Discussion: Toward a Clinical Algorithm for Difficult-to-Treat MOGAD

- First-line acute therapy: IV methylprednisolone (1 g/day × 3–5 days), followed by oral steroid taper over ≥3 months

- If response is incomplete: consider IVIG (2 g/kg) or PLEX (5–7 sessions)

- Persistent or early relapse: initiation of maintenance immunotherapy, often beginning with monthly IVIG or oral azathioprine/MMF/Tacrolims

- Second-line biologics: Tocilizumab, satralizumab, and rituximab for patients with frequent relapses.

- Other options: In severe multiphasic cases, options include aHSCT or anti-CD19 CAR T cells under specialized care.

1. Future directions and research priorities

7. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Reindl, M.; Di Pauli, F.; Rostasy, K.; Berger, T. The spectrum of MOG autoantibody-associated demyelinating diseases. Nat Rev Neurol 2013, 9, 455-461. [CrossRef]

- Marignier, R.; Hacohen, Y.; Cobo-Calvo, A.; Pröbstel, A.K.; Aktas, O.; Alexopoulos, H.; Amato, M.P.; Asgari, N.; Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.; et al. Myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 762-772. [CrossRef]

- Fadda, G.; Armangue, T.; Hacohen, Y.; Chitnis, T.; Banwell, B. Paediatric multiple sclerosis and antibody-associated demyelination: Clinical, imaging, and biological considerations for diagnosis and care. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 136-149. [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Calvo, A.; Ruiz, A.; Maillart, E.; Audoin, B.; Zephir, H.; Bourre, B.; Ciron, J.; Collongues, N.; Brassat, D.; Cotton, F.; et al. Clinical spectrum and prognostic value of CNS MOG autoimmunity in adults: The MOGADOR study. Neurology 2018, 90, e1858-e1869. [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Calvo, A.; Ruiz, A.; Rollot, F.; Arrambide, G.; Deschamps, R.; Maillart, E.; Papeix, C.; Audoin, B.; Lepine, A.F.; Maurey, H.; et al. Clinical Features and Risk of Relapse in Children and Adults with Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. Ann Neurol 2021, 89, 30-41. [CrossRef]

- Hacohen, Y.; Wong, Y.Y.; Lechner, C.; Jurynczyk, M.; Wright, S.; Konuskan, B.; Kalser, J.; Poulat, A.L.; Maurey, H.; Ganelin-Cohen, E.; et al. Disease Course and Treatment Responses in Children With Relapsing Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. JAMA Neurol 2018, 75, 478-487. [CrossRef]

- Armangue, T.; Olivé-Cirera, G.; Martínez-Hernandez, E.; Sepulveda, M.; Ruiz-Garcia, R.; Muñoz-Batista, M.; Ariño, H.; González-Álvarez, V.; Felipe-Rucián, A.; Jesús Martínez-González, M.; et al. Associations of paediatric demyelinating and encephalitic syndromes with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies: A multicentre observational study. The Lancet Neurology 2020, 19, 234-246. [CrossRef]

- de Mol, C.L.; Wong, Y.; van Pelt, E.D.; Wokke, B.; Siepman, T.; Neuteboom, R.F.; Hamann, D.; Hintzen, R.Q. The clinical spectrum and incidence of anti-MOG-associated acquired demyelinating syndromes in children and adults. Mult Scler 2020, 26, 806-814. [CrossRef]

- Jarius, S.; Pellkofer, H.; Siebert, N.; Korporal-Kuhnke, M.; Hummert, M.W.; Ringelstein, M.; Rommer, P.S.; Ayzenberg, I.; Ruprecht, K.; Klotz, L.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies. Part 1: Results from 163 lumbar punctures in 100 adult patients. Journal of neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 261. [CrossRef]

- Takai, Y.; Misu, T.; Kaneko, K.; Chihara, N.; Narikawa, K.; Tsuchida, S.; Nishida, H.; Komori, T.; Seki, M.; Komatsu, T.; et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: An immunopathological study. Brain 2020, 143, 1431-1446. [CrossRef]

- Hoftberger, R.; Guo, Y.; Flanagan, E.P.; Lopez-Chiriboga, A.S.; Endmayr, V.; Hochmeister, S.; Joldic, D.; Pittock, S.J.; Tillema, J.M.; Gorman, M.; et al. The pathology of central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disease accompanying myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein autoantibody. Acta Neuropathol 2020, 139, 875-892. [CrossRef]

- Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.L.; Marignier, R.; Kim, H.J.; Brilot, F.; Flanagan, E.P.; Ramanathan, S.; Waters, P.; Tenembaum, S.; Graves, J.S.; et al. Diagnosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: International MOGAD Panel proposed criteria. Lancet Neurol 2023, 22, 268-282. [CrossRef]

- Hacohen, Y.; Mankad, K.; Chong, W.K.; Barkhof, F.; Vincent, A.; Lim, M.; Wassmer, E.; Ciccarelli, O.; Hemingway, C. Diagnostic algorithm for relapsing acquired demyelinating syndromes in children. Neurology 2017, 89, 269-278. [CrossRef]

- Hor, J.Y.; Fujihara, K. Epidemiology of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: A review of prevalence and incidence worldwide. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1260358. [CrossRef]

- López-Chiriboga, A.S.; Majed, M.; Fryer, J.; Dubey, D.; McKeon, A.; Flanagan, E.P.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Kothapalli, N.; Tillema, J.M.; Chen, J.; et al. Association of MOG-IgG Serostatus With Relapse After Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis and Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for MOG-IgG-Associated Disorders. JAMA Neurol 2018, 75, 1355-1363. [CrossRef]

- Lassmann, H. The contribution of neuropathology to multiple sclerosis research. Eur J Neurol 2022, 29, 2869-2877. [CrossRef]

- Misu, T.; Takai, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Nakashima, I.; Fujihara, K.; Aoki, M. Perivenous demyelination: Association with anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody. Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology 2020, 11, 22-27. [CrossRef]

- Young, N.P.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Parisi, J.E.; Scheithauer, B.; Giannini, C.; Roemer, S.F.; Thomsen, K.M.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Erickson, B.J.; Lucchinetti, C.F. Perivenous demyelination: Association with clinically defined acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and comparison with pathologically confirmed multiple sclerosis. Brain 2010, 133, 333-348. [CrossRef]

- Körtvélyessy, P.; Breu, M.; Pawlitzki, M.; Metz, I.; Heinze, H.-J.; Matzke, M.; Mawrin, C.; Rommer, P.; Kovacs, G.G.; Mitter, C.; et al. ADEM-like presentation, anti-MOG antibodies, and MS pathology: TWO case reports. Neurology® Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2017, 4, e335. [CrossRef]

- Misu, T.; Höftberger, R.; Fujihara, K.; Wimmer, I.; Takai, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Nakashima, I.; Konno, H.; Bradl, M.; Garzuly, F.; et al. Presence of six different lesion types suggests diverse mechanisms of tissue injury in neuromyelitis optica. Acta Neuropathologica 2013, 125, 815-827. [CrossRef]

- Asavapanumas, N.; Tradtrantip, L.; Verkman, A.S. Targeting the complement system in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2021, 21, 1073-1086. [CrossRef]

- Dunkelberger, J.R.; Song, W.-C. Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Research 2010, 20, 34-50. [CrossRef]

- Bradl, M.; Misu, T.; Takahashi, T.; Watanabe, M.; Mader, S.; Reindl, M.; Adzemovic, M.; Bauer, J.; Berger, T.; Fujihara, K.; et al. Neuromyelitis optica: Pathogenicity of patient immunoglobulin in vivo. Ann Neurol 2009, 66, 630-643. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, H.; Fujihara, K.; Takano, R.; Takai, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Misu, T.; Nakashima, I.; Sato, S.; Itoyama, Y.; Aoki, M. Increase of complement fragment C5a in cerebrospinal fluid during exacerbation of neuromyelitis optica. J Neuroimmunol 2013, 254, 178-182. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Murakami, K.; Sakata, M.; Nakayama, Y.; Kuwahara, M.; Inoue, N. Predictive complement biomarkers for relapse in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2025, 94, 106282. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, H.N.; Guempelein, L.; Schikora, J.; Pauly, D. C3a Mediates Endothelial Barrier Disruption in Brain-Derived, but Not Retinal, Human Endothelial Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Kuroda, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Sakamoto, N.; Yamazaki, N.; Yamamoto, N.; Umezawa, S.; Namatame, C.; Ono, H.; Takai, Y.; et al. Different Complement Activation Patterns Following C5 Cleavage in MOGAD and AQP4-IgG+NMOSD. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2024, 11, e200293. [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, M.; Winklmeier, S.; Beltrán, E.; Macrini, C.; Höftberger, R.; Schuh, E.; Thaler, F.S.; Gerdes, L.A.; Laurent, S.; Gerhards, R.; et al. Pathogenicity of human antibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Ann Neurol 2018, 84, 315-328. [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, K.; Nishida, H.; Kaneko, K.; Misu, T.; Nakashima, I.; Sakuma, H. Complement-dependent cytotoxicity of human autoantibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Front Neurosci 2023, 17, 1014071. [CrossRef]

- Spadaro, M.; Gerdes, L.A.; Mayer, M.C.; Ertl-Wagner, B.; Laurent, S.; Krumbholz, M.; Breithaupt, C.; Högen, T.; Straube, A.; Giese, A.; et al. Histopathology and clinical course of MOG-antibody-associated encephalomyelitis. Annals of clinical and translational neurology 2015, 2, 295-301. [CrossRef]

- Takai, Y.; Misu, T.; Fujihara, K.; Aoki, M. Pathology of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: A comparison with multiple sclerosis and aquaporin 4 antibody-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1209749. [CrossRef]

- Lerch, M.; Schanda, K.; Lafon, E.; Würzner, R.; Mariotto, S.; Dinoto, A.; Wendel, E.M.; Lechner, C.; Hegen, H.; Rostásy, K.; et al. More Efficient Complement Activation by Anti-Aquaporin-4 Compared With Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibodies. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2023, 10, e200059. [CrossRef]

- Misu, T.; Fujihara, K.; Nakashima, I.; Sato, S.; Itoyama, Y. Intractable hiccup and nausea with periaqueductal lesions in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2005, 65, 1479-1482. [CrossRef]

- Macrini, C.; Gerhards, R.; Winklmeier, S.; Bergmann, L.; Mader, S.; Spadaro, M.; Vural, A.; Smolle, M.; Hohlfeld, R.; Kumpfel, T.; et al. Features of MOG required for recognition by patients with MOG antibody-associated disorders. Brain 2021, 144, 2375-2389. [CrossRef]

- Mader, S.; Ho, S.; Wong, H.K.; Baier, S.; Winklmeier, S.; Riemer, C.; Rübsamen, H.; Fernandez, I.M.; Gerhards, R.; Du, C.; et al. Dissection of complement and Fc-receptor-mediated pathomechanisms of autoantibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2023, 120, e2300648120. [CrossRef]

- Hofer, L.S.; Ramberger, M.; Gredler, V.; Pescoller, A.S.; Rostásy, K.; Sospedra, M.; Hegen, H.; Berger, T.; Lutterotti, A.; Reindl, M. Comparative Analysis of T-Cell Responses to Aquaporin-4 and Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein in Inflammatory Demyelinating Central Nervous System Diseases. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, Volume 11 - 2020, 1188. [CrossRef]

- Ono, H.; Misu, T.; Namatame, C.; Matsumoto, Y.; Takai, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Kuroda, H.; Takahashi, T.; Nakashima, I.; Fujihara, K.; et al. CD4-Positive T-Cell Responses to MOG Peptides in MOG Antibody-Associated Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 3606. [CrossRef]

- Dale, R.C.; Tantsis, E.M.; Merheb, V.; Kumaran, R.Y.; Sinmaz, N.; Pathmanandavel, K.; Ramanathan, S.; Booth, D.R.; Wienholt, L.A.; Prelog, K.; et al. Antibodies to MOG have a demyelination phenotype and affect oligodendrocyte cytoskeleton. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2014, 1, e12. [CrossRef]

- Yandamuri, S.S.; Filipek, B.; Obaid, A.H.; Lele, N.; Thurman, J.M.; Makhani, N.; Nowak, R.J.; Guo, Y.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Flanagan, E.P.; et al. MOGAD patient autoantibodies induce complement, phagocytosis, and cellular cytotoxicity. JCI Insight 2023, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.L.; Costello, F.; Chen, J.J.; Petzold, A.; Biousse, V.; Newman, N.J.; Galetta, S.L. Optic neuritis and autoimmune optic neuropathies: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. The Lancet Neurology 2023, 22, 89-100. [CrossRef]

- Jurynczyk, M.; Messina, S.; Woodhall, M.R.; Raza, N.; Everett, R.; Roca-Fernandez, A.; Tackley, G.; Hamid, S.; Sheard, A.; Reynolds, G.; et al. Clinical presentation and prognosis in MOG-antibody disease: A UK study. Brain 2017, 140, 3128-3138. [CrossRef]

- Armangue, T.; Olive-Cirera, G.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; Sepulveda, M.; Ruiz-Garcia, R.; Munoz-Batista, M.; Arino, H.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, V.; Felipe-Rucian, A.; Jesus Martinez-Gonzalez, M.; et al. Associations of paediatric demyelinating and encephalitic syndromes with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies: A multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol 2020, 19, 234-246. [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, R.; Nakashima, I.; Takahashi, T.; Kaneko, K.; Akaishi, T.; Takai, Y.; Sato, D.K.; Nishiyama, S.; Misu, T.; Kuroda, H.; et al. MOG antibody-positive, benign, unilateral, cerebral cortical encephalitis with epilepsy. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2017, 4, e322. [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, J.; Takai, Y.; Nakashima, I.; Sato, D.K.; Takahashi, T.; Kaneko, K.; Nishiyama, S.; Watanabe, M.; Tanji, H.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. Bilateral frontal cortex encephalitis and paraparesis in a patient with anti-MOG antibodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017, 88, 534-536. [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Calvo, A.; Ruiz, A.; Rollot, F.; Arrambide, G.; Deschamps, R.; Maillart, E.; Papeix, C.; Audoin, B.; Lépine, A.F.; Maurey, H.; et al. Clinical Features and Risk of Relapse in Children and Adults with Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. Ann Neurol 2021, 89, 30-41. [CrossRef]

- Duchow, A.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Friede, T.; Aktas, O.; Angstwurm, K.; Ayzenberg, I.; Berthele, A.; Dawin, E.; Engels, D.; Fischer, K.; et al. Time to Disability Milestones and Annualized Relapse Rates in NMOSD and MOGAD. Annals of Neurology 2024, 95, 720-732. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Pittock, S.J.; Krecke, K.N.; Morris, P.P.; Sechi, E.; Zalewski, N.L.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Shosha, E.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Fryer, J.P.; et al. Clinical, Radiologic, and Prognostic Features of Myelitis Associated With Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Autoantibody. JAMA Neurol 2019, 76, 301-309. [CrossRef]

- Satukijchai, C.; Mariano, R.; Messina, S.; Sa, M.; Woodhall, M.R.; Robertson, N.P.; Ming, L.; Wassmer, E.; Kneen, R.; Huda, S.; et al. Factors Associated With Relapse and Treatment of Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease in the United Kingdom. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2142780. [CrossRef]

- Sechi, E.; Cacciaguerra, L.; Chen, J.J.; Mariotto, S.; Fadda, G.; Dinoto, A.; Lopez-Chiriboga, A.S.; Pittock, S.J.; Flanagan, E.P. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD): A Review of Clinical and MRI Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 885218. [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Mohammad, S.; Tantsis, E.; Nguyen, T.K.; Merheb, V.; Fung, V.S.C.; White, O.B.; Broadley, S.; Lechner-Scott, J.; Vucic, S.; et al. Clinical course, therapeutic responses and outcomes in relapsing MOG antibody-associated demyelination. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018, 89, 127-137. [CrossRef]

- Fadda, G.; Flanagan, E.P.; Cacciaguerra, L.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Solla, P.; Zara, P.; Sechi, E. Myelitis features and outcomes in CNS demyelinating disorders: Comparison between multiple sclerosis, MOGAD, and AQP4-IgG-positive NMOSD. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 1011579. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Narayan, R.; Greenberg, B. Anti-Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody Associated With Gray Matter Predominant Transverse Myelitis Mimicking Acute Flaccid Myelitis: A Presentation of Two Cases. Pediatr Neurol 2018, 86, 42-45. [CrossRef]

- Mariano, R.; Messina, S.; Kumar, K.; Kuker, W.; Leite, M.I.; Palace, J. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes of Transverse Myelitis Among Adults With Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody vs Aquaporin-4 Antibody Disease. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e1912732. [CrossRef]

- Ringelstein, M.; Ayzenberg, I.; Lindenblatt, G.; Fischer, K.; Gahlen, A.; Novi, G.; Hayward-Könnecke, H.; Schippling, S.; Rommer, P.S.; Kornek, B.; et al. Interleukin-6 Receptor Blockade in Treatment-Refractory MOG-IgG-Associated Disease and Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2022, 9, e1100. [CrossRef]

- Handzic, A.; Xie, J.S.; Tisavipat, N.; O'Cearbhaill, R.M.; Tajfirouz, D.A.; Chodnicki, K.D.; Flanagan, E.P.; Chen, J.J.; Micieli, J.; Margolin, E. Radiologic Predictors of Visual Outcome in Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein-Related Optic Neuritis. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 170-180. [CrossRef]

- Trewin, B.P.; Brilot, F.; Reddel, S.W.; Dale, R.C.; Ramanathan, S. MOGAD: A comprehensive review of clinicoradiological features, therapy and outcomes in 4699 patients globally. Autoimmun Rev 2025, 24, 103693. [CrossRef]

- Hennes, E.-M.; Baumann, M.; Schanda, K.; Anlar, B.; Bajer-Kornek, B.; Blaschek, A.; Brantner-Inthaler, S.; Diepold, K.; Eisenkölbl, A.; Gotwald, T.; et al. Prognostic relevance of MOG antibodies in children with an acquired demyelinating syndrome. Neurology 2017, 89, 900-908, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004312.

- Baumann, M.; Hennes, E.-M.; Schanda, K.; Karenfort, M.; Kornek, B.; Seidl, R.; Diepold, K.; Lauffer, H.; Marquardt, I.; Strautmanis, J.; et al. Children with multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and antibodies to the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG): Extending the spectrum of MOG antibody positive diseases. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2016, 22, 1821-1829. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, R.; Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Q. Two rare cases of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorder in children with leukodystrophy-like imaging findings. BMC Neurol 2023, 23, 247. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, R.K.; Vibha, D.; Gaikwad, S.; Tripathi, M. Drug refractory epilepsy in MOGAD: An evolving spectrum. Neurol Sci 2024, 45, 1779-1781. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo, M.; Khattak, J.F.; Redenbaugh, V.; Britton, J.; Sanchez, C.V.; Datta, A.; Tillema, J.-M.; Chen, J.; McKeon, A.; Pittock, S.J.; et al. Acute symptomatic seizures secondary to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 3180-3191. [CrossRef]

- Budhram, A.; Mirian, A.; Le, C.; Hosseini-Moghaddam, S.M.; Sharma, M.; Nicolle, M.W. Unilateral cortical FLAIR-hyperintense Lesions in Anti-MOG-associated Encephalitis with Seizures (FLAMES): Characterization of a distinct clinico-radiographic syndrome. Journal of Neurology 2019, 266, 2481-2487. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.R.; Kim, K.H.; Hyun, J.W.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.J. Efficacy of tocilizumab in highly relapsing MOGAD with an inadequate response to intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: A case series. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2024, 91, 105859. [CrossRef]

- Sbragia, E.; Boffa, G.; Varaldo, R.; Raiola, A.M.; Ghiso, A.; Gambella, M.; Benedetti, L.; Angelucci, E.; Inglese, M. An aggressive form of MOGAD treated with aHSCT: A case report. Mult Scler 2024, 30, 612-616. [CrossRef]

- Caicedo, C.N.; Jimenez, S.; Li, X.; Fang, X. Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis with Elevated MOG Antibodies: A Case of Overlapping Autoimmune Syndromes (P10-8.008). Neurology 2025, 104, 5294, doi:doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000212268.

- Kaneko, K.; Sato, D.K.; Kurosawa, K.; Misu, T.; Nakashima, I.; Fujihara, K.; Aoki, M. Case of autoantibodies against N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor+/antibodies against myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein+ multiphasic acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). Clinical and Experimental Neuroimmunology 2014, 5, 49-51. [CrossRef]

- Titulaer, M.J.; Hoftberger, R.; Iizuka, T.; Leypoldt, F.; McCracken, L.; Cellucci, T.; Benson, L.A.; Shu, H.; Irioka, T.; Hirano, M.; et al. Overlapping demyelinating syndromes and anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Ann Neurol 2014, 75, 411-428. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tan, C.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Hong, S.; Yuan, P.; Zheng, H.; Fan, X.; Han, W. Clinical features of the first attack with leukodystrophy-like phenotype in children with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disorders. Int J Dev Neurosci 2023, 83, 267-273. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, E.; Ankar, A.; Malani Shukla, N. Refractory MOG-Associated Demyelinating Disease in a Pediatric Patient. Child Neurol Open 2022, 9, 2329048x221079093. [CrossRef]

- Nosadini, M.; Eyre, M.; Giacomini, T.; Valeriani, M.; Della Corte, M.; Praticò, A.D.; Annovazzi, P.; Cordani, R.; Cordelli, D.M.; Crichiutti, G.; et al. Early Immunotherapy and Longer Corticosteroid Treatment Are Associated With Lower Risk of Relapsing Disease Course in Pediatric MOGAD. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2023, 10, e200065. [CrossRef]

- Cortese, R.; Prados Carrasco, F.; Tur, C.; Bianchi, A.; Brownlee, W.; De Angelis, F.; De La Paz, I.; Grussu, F.; Haider, L.; Jacob, A.; et al. Differentiating Multiple Sclerosis From AQP4-Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder and MOG-Antibody Disease With Imaging. Neurology 2023, 100, e308-e323. [CrossRef]

- Salama, S.; Khan, M.; Shanechi, A.; Levy, M.; Izbudak, I. MRI differences between MOG antibody disease and AQP4 NMOSD. Mult Scler 2020, 26, 1854-1865. [CrossRef]

- Mariano, R.; Messina, S.; Roca-Fernandez, A.; Leite, M.I.; Kong, Y.; Palace, J.A. Quantitative spinal cord MRI in MOG-antibody disease, neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis. Brain 2020, 144, 198-212. [CrossRef]

- Carandini, T.; Sacchi, L.; Bovis, F.; Azzimonti, M.; Bozzali, M.; Galimberti, D.; Scarpini, E.; Pietroboni, A.M. Distinct patterns of MRI lesions in MOG antibody disease and AQP4 NMOSD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 54, 103118. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Ohyama, A.; Kubota, T.; Ikeda, K.; Kaneko, K.; Takai, Y.; Warita, H.; Takahashi, T.; Misu, T.; Aoki, M. MOG Antibody-Associated Disorders Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 845755. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Misu, T.; Mugikura, S.; Takai, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Kuroda, H.; Takahashi, T.; Fujimori, J.; Nakashima, I.; Fujihara, K.; et al. Distinctive lesions of brain MRI between MOG-antibody-associated and AQP4-antibody-associated diseases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020, 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324818, 682–684. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; López-Chiriboga, A.S.S.; Fryer, J.P.; Leavitt, J.A.; Weinshenker, B.G.; McKeon, A.; Tillema, J.M.; Lennon, V.A.; et al. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Positive Optic Neuritis: Clinical Characteristics, Radiologic Clues, and Outcome. Am J Ophthalmol 2018, 195, 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, R.; Arrambide, G.; Banwell, B.; Rovira, À.; Cortese, R.; Lassmann, H.; Messina, S.; Rocca, M.A.; Waters, P.; Chard, D.; et al. The influence of MOGAD on diagnosis of multiple sclerosis using MRI. Nat Rev Neurol 2024, 20, 620-635. [CrossRef]

- Cacciaguerra, L.; Morris, P.; Tobin, W.O.; Chen, J.J.; Banks, S.A.; Elsbernd, P.; Redenbaugh, V.; Tillema, J.M.; Montini, F.; Sechi, E.; et al. Tumefactive Demyelination in MOG Ab-Associated Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, and AQP-4-IgG-Positive Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Neurology 2023, 100, e1418-e1432. [CrossRef]

- Sato, D.K.; Callegaro, D.; Lana-Peixoto, M.A.; Waters, P.J.; de Haidar Jorge, F.M.; Takahashi, T.; Nakashima, I.; Apostolos-Pereira, S.L.; Talim, N.; Simm, R.F.; et al. Distinction between MOG antibody-positive and AQP4 antibody-positive NMO spectrum disorders. Neurology 2014, 82, 474-481. [CrossRef]

- Stredny, C.M.; Steriade, C.; Papadopoulou, M.T.; Pujar, S.; Kaliakatsos, M.; Tomko, S.; Wickström, R.; Cortina, C.; Zhang, B.; Bien, C.G. Current practices in the diagnosis and treatment of Rasmussen syndrome: Results of an international survey. Seizure - European Journal of Epilepsy 2024, 122, 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, E.-J.; Kim, S.; Choi, L.-K.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, K.-K.; Lim, Y.-M. Serum biomarkers in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody–associated disease. Neurology Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2020, 7, e708, doi:doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000000708.

- Waters, P.; Fadda, G.; Woodhall, M.; O’Mahony, J.; Brown, R.A.; Castro, D.A.; Longoni, G.; Irani, S.R.; Sun, B.; Yeh, E.A.; et al. Serial Anti–Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody Analyses and Outcomes in Children With Demyelinating Syndromes. JAMA Neurology 2020, 77, 82-93. [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, M.; Foiadelli, T.; Greco, G.; Scaranzin, S.; Rigoni, E.; Masciocchi, S.; Ferrari, S.; Mancinelli, C.; Brambilla, L.; Mancardi, M.; et al. Prognostic relevance of quantitative and longitudinal MOG antibody testing in patients with MOGAD: A multicentre retrospective study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2023, 94, 201-210. [CrossRef]

- Virupakshaiah, A.; Moseley, C.E.; Elicegui, S.; Gerwitz, L.M.; Spencer, C.M.; George, E.; Shah, M.; Cree, B.A.C.; Waubant, E.; Zamvil, S.S. Life-Threatening MOG Antibody-Associated Hemorrhagic ADEM With Elevated CSF IL-6. Neurology Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2024, 11, e200243, doi:doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000200243.

- Kaneko, K.; Sato, D.K.; Nakashima, I.; Ogawa, R.; Akaishi, T.; Takai, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Takahashi, T.; Misu, T.; Kuroda, H.; et al. CSF cytokine profile in MOG-IgG+ neurological disease is similar to AQP4-IgG+ NMOSD but distinct from MS: A cross-sectional study and potential therapeutic implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018, 89, 927-936. [CrossRef]

- Villacieros-Álvarez, J.; Espejo, C.; Arrambide, G.; Dinoto, A.; Mulero, P.; Rubio-Flores, L.; Nieto, P.; Alcalá, C.; Meca-Lallana, J.E.; Millan-Pascual, J.; et al. Profile and Usefulness of Serum Cytokines to Predict Prognosis in Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2025, 12, e200362. [CrossRef]

- Horellou, P.; Wang, M.; Keo, V.; Chrétien, P.; Serguera, C.; Waters, P.; Deiva, K. Increased interleukin-6 correlates with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in pediatric monophasic demyelinating diseases and multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2015, 289, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Villacieros-Álvarez, J.; Lunemann, J.D.; Sepulveda, M.; Valls-Carbó, A.; Dinoto, A.; Fernández, V.; Vilaseca, A.; Castillo, M.; Arrambide, G.; Bollo, L.; et al. Complement Activation Profiles Predict Clinical Outcomes in Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2025, 12, e200340. [CrossRef]

- Akaishi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Misu, T.; Kaneko, K.; Takai, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Ogawa, R.; Fujimori, J.; Ishii, T.; Aoki, M.; et al. Difference in the Source of Anti-AQP4-IgG and Anti-MOG-IgG Antibodies in CSF in Patients With Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. Neurology 2021, 97, e1-e12. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Kaneko, K.; Takahashi, T.; Takai, Y.; Namatame, C.; Kuroda, H.; Misu, T.; Fujihara, K.; Aoki, M. Diagnostic implications of MOG-IgG detection in sera and cerebrospinal fluids. Brain 2023, 146, 3938-3948. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.N.; Kim, B.; Kim, J.S.; Mo, H.; Choi, K.; Oh, S.I.; Kim, J.E.; Nam, T.S.; Sohn, E.H.; Heo, S.H.; et al. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein-Immunoglobulin G in the CSF: Clinical Implication of Testing and Association With Disability. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2022, 9, e1095. [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Risi, M.; Masciocchi, S.; Businaro, P.; Rigoni, E.; Zardini, E.; Scaranzin, S.; Morandi, C.; Diamanti, L.; Foiadelli, T.; et al. Clinical, prognostic and pathophysiological implications of MOG-IgG detection in the CSF: The importance of intrathecal MOG-IgG synthesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2024, 95, 1176-1186. [CrossRef]

- Keller, C.W.; Lopez, J.A.; Wendel, E.M.; Ramanathan, S.; Gross, C.C.; Klotz, L.; Reindl, M.; Dale, R.C.; Wiendl, H.; Rostásy, K.; et al. Complement Activation Is a Prominent Feature of MOGAD. Ann Neurol 2021, 90, 976-982. [CrossRef]

- Mariotto, S.; Gastaldi, M.; Grazian, L.; Mancinelli, C.; Capra, R.; Marignier, R.; Alberti, D.; Zanzoni, S.; Schanda, K.; Franciotta, D.; et al. NfL levels predominantly increase at disease onset in MOG-Abs-associated disorders. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2021, 50, 102833. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.-W.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.; Park, N.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, H.J. Absence of attack-independent neuroaxonal injury in MOG antibody-associated disease: Longitudinal assessment of serum neurofilament light chain. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2022, 28, 993-999. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Chen, Y.; Mao, S.; Jin, J.; Liu, C.; Zhong, X.; Sun, X.; Kermode, A.G.; Qiu, W. Serum neurofilament light chain in adult and pediatric patients with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: Correlation with relapses and seizures. Journal of Neurochemistry 2022, 160, 568-577. [CrossRef]

- Wendel, E.-M.; Bertolini, A.; Kousoulos, L.; Rauchenzauner, M.; Schanda, K.; Wegener-Panzer, A.; Baumann, M.; Reindl, M.; Otto, M.; Rostásy, K. Serum neurofilament light-chain levels in children with monophasic myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-associated disease, multiple sclerosis, and other acquired demyelinating syndrome. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2022, 28, 1553-1561. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Sato, D.K.; Nakashima, I.; Nishiyama, S.; Tanaka, S.; Marignier, R.; Hyun, J.W.; Oliveira, L.M.; Reindl, M.; Seifert-Held, T.; et al. Myelin injury without astrocytopathy in neuroinflammatory disorders with MOG antibodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016, 87, 1257-1259. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Huang, W.; Wang, L.; ZhangBao, J.; Zhou, L.; Lu, C.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; et al. Serum Neurofilament Light and GFAP Are Associated With Disease Severity in Inflammatory Disorders With Aquaporin-4 or Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibodies. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, Volume 12 - 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Pittock, S.J.; Stern, N.C.; Tisavipat, N.; Bhatti, M.T.; Chodnicki, K.D.; Tajfirouz, D.A.; Jamali, S.; Kunchok, A.; et al. Visual Outcomes Following Plasma Exchange for Optic Neuritis: An International Multicenter Retrospective Analysis of 395 Optic Neuritis Attacks. Am J Ophthalmol 2023, 252, 213-224. [CrossRef]

- MacRae, R.; Race, J.; Schuette, A.; Waltz, M.; Casper, T.C.; Rose, J.; Abrams, A.; Rensel, M.; Waubant, E.; Virupakshaiah, A.; et al. Limited early IVIG for the treatment of pediatric myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2025, 97, 106345. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Flanagan, E.P.; Bhatti, M.T.; Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Dubey, D.; Lopez Chiriboga, A.S.S.; Fryer, J.P.; Weinshenker, B.G.; McKeon, A.; Tillema, J.M.; et al. Steroid-sparing maintenance immunotherapy for MOG-IgG associated disorder. Neurology 2020, 95, e111-e120. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Huda, S.; Hacohen, Y.; Levy, M.; Lotan, I.; Wilf-Yarkoni, A.; Stiebel-Kalish, H.; Hellmann, M.A.; Sotirchos, E.S.; Henderson, A.D.; et al. Association of Maintenance Intravenous Immunoglobulin With Prevention of Relapse in Adult Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease. JAMA Neurol 2022, 79, 518-525. [CrossRef]

- Kamijo, Y.; Usuda, M.; Matsuno, A.; Katoh, N.; Morita, Y.; Tamaru, F.; Kasamatsu, H.; Sekijima, Y. Successful Maintenance Therapy with Intravenous Immunoglobulin to Reduce Relapse Attacks and Steroid Dose in a Patient with Refractory Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-positive Optic Neuritis. Intern Med 2025, 64, 775-779. [CrossRef]

- Whittam, D.H.; Cobo-Calvo, A.; Lopez-Chiriboga, A.S.; Pardo, S.; Gornall, M.; Cicconi, S.; Brandt, A.; Berek, K.; Berger, T.; Jelcic, I.; et al. Treatment of MOG-IgG-associated disorder with rituximab: An international study of 121 patients. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020, 44, 102251. [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, J.; Zhu, R.; Li, N. A comparison of the effects of rituximab versus other immunotherapies for MOG-IgG-associated central nervous system demyelination: A meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2021, 53, 103044. [CrossRef]

- Barreras, P.; Vasileiou, E.S.; Filippatou, A.G.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Levy, M.; Pardo, C.A.; Newsome, S.D.; Mowry, E.M.; Calabresi, P.A.; Sotirchos, E.S. Long-term Effectiveness and Safety of Rituximab in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder and MOG Antibody Disease. Neurology 2022, 99, e2504-e2516. [CrossRef]

- Bayry, J.; Misra, N.; Latry, V.; Prost, F.; Delignat, S.; Lacroix-Desmazes, S.; Kazatchkine, M.D.; Kaveri, S.V. Mechanisms of action of intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Transfus Clin Biol 2003, 10, 165-169. [CrossRef]

- Remlinger, J.; Madarasz, A.; Guse, K.; Hoepner, R.; Bagnoud, M.; Meli, I.; Feil, M.; Abegg, M.; Linington, C.; Shock, A.; et al. Antineonatal Fc Receptor Antibody Treatment Ameliorates MOG-IgG–Associated Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Neurology Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation 2022, 9, e1134, doi:doi:10.1212/NXI.0000000000001134.

- Redenbaugh, V.; Flanagan, E.P. Monoclonal Antibody Therapies Beyond Complement for NMOSD and MOGAD. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 808-822. [CrossRef]

- Digala, L.; Katyal, N.; Narula, N.; Govindarajan, R. Eculizumab in the Treatment of Aquaporin-4 Seronegative Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: A Case Report. Frontiers in Neurology 2021, Volume 12 - 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, M.; Wang, C.; Guo, S. Successful sequential therapy with rituximab and telitacicept in refractory Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis and MOG-associated demyelination: A case report and literature review. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1509143. [CrossRef]

- Derdelinckx, J.; Reynders, T.; Wens, I.; Cools, N.; Willekens, B. Cells to the Rescue: Emerging Cell-Based Treatment Approaches for NMOSD and MOGAD. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 7925. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Maqueda, J.M.; Sepulveda, M.; García, R.R.; Muñoz-Sánchez, G.; Martínez-Cibrian, N.; Ortíz-Maldonado, V.; Lorca-Arce, D.; Guasp, M.; Llufriu, S.; Martinez-Hernandez, E.; et al. CD19-Directed CAR T-Cells in a Patient With Refractory MOGAD: Clinical and Immunologic Follow-Up for 1 Year. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2024, 11, e200292. [CrossRef]

| benign factors | malignant factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset age | Younger less than 10 years (monophasic > multiphasic) | Older age in adults (relapsing and poor recovery) |

| Clinical course | monophasic | multiphasic/relapsing |

| Onset symptoms | optic neuritis | |

| myelitis/encephalitis/brainstem | ||

| (mostly monophasic) | (incomplete recovery from onset) | |

| Cognition | none | consciousness disturbance/epilepsy |

| Therapeutic response | markedly improved in 1st IVMP | Refractory to 1st and 2nd IVMP |

| No relapse in maintenance treatment | disease activity in 2nd line treatment | |

| No residual symptoms after onset | Residual symptoms after treatment | |

| IVMP within 1 week (monophasic) | delayed IVMP (multiphasic course) | |

| MOG-IgG titers | seronegative conversion | high in ADEM, cortical encephalitis |

| isolated serum for optic neuritis | CSF persistent for disease worsening | |

| MRI | Vanishing lesion in initial treatment | residual lesions after treatment |

| Gd-enhancement initially subsided | Persistent Gd-enhancement | |

| No atrophy | Progressive atrophy | |

| ADEM like monophasic | Multiphasic ADEM | |

| Isolated multiple lesions | Leukodystrophy-like diffuse lesion | |

| (Transitional type/Schilder type) | ||

| Biomarkers | ||

| Nf-L/Tau | low in serum | high in acute stage |

| IL-6 | low in serum and CSF | high in acute stage severely disabled |

| C5b-9 | low in serum and CSF | high in patients with EDSS > 3.0. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).