1. Introduction

The phytoplankton communities that inhabit Earth’s marine and freshwater bodies are a diverse collection of organisms that perform a wide array of ecological and biogeochemical functions that span a wide range of sizes from sub-micron to millimeters (Chisholm, 1992; Finkel et al., 2010; le Quéré et al., 2005; Marañón et al., 2012). Understanding how these communities are organized – often referred to as phytoplankton community composition (PCC) – can reveal fundamental information on the uptake of atmospheric CO2 through photosynthesis, how much of that photosynthetically fixed carbon sinks to the deep ocean over climate-relevant time scales, and how efficiently their energy is transferred to higher trophic levels such as economically important fisheries species.

Given the fundamental control that phytoplankton exert on global carbon cycling and food security, increasing emphasis has been placed on realistic PCC representation in ecosystem and Earth System models, although little consensus has been reached on the most realistic approaches to achieve this (Shimoda and Arhonditsis, 2016). Typically phytoplankton communities are represented as size classes or taxonomic groupings (Bopp et al., 2013; Dutkiewicz et al., 2015; Follows et al., 2007; le Quéré et al., 2005). However, measurements of phytoplankton taxonomy are, by the very nature of oceanographic sampling, very sparse.

1.1. Remote Sensing Approaches for PCC Retrieval

Over the past two decades, several efforts have been made to develop approaches for characterizing PCC from satellite ocean color sensors in order to address the temporal and spatial paucity of such measurements (IOCCG, 2014; Mouw et al., 2017). These existing methods can be separated into three different types of approaches: i) Abundance approaches that utilize satellite derived chlorophyll-a (Chl a) to derive a phytoplankton size class or taxonomic grouping. This is based on empirical relationships previously determined between in situ high precision liquid chromatography (HPLC)-measured phytoplankton marker pigments and total Chl a (Brewin et al., 2011; IOCCG, 2014); ii) Spectral based methods that rely on the relationships between spectral features in remote sensing reflectance, imparted by absorption and scattering by various phytoplankton groups, again, using HPLC pigments as taxonomic grouping proxies (Kostadinov et al., 2009) ; and iii) Ecological approaches that utilize ocean color and other satellite measurements of environmental data (e.g. irradiance, sea surface temperature, wind) to delineate ecological niches associated with the occurrence of certain phytoplankton communities (Raitsos et al., 2008). More recently, others have investigated the relationships between HPLC pigments and the results of spectral derivative analysis, Gaussian curve fitting, EOF analysis and hierarchical clustering to elucidate information on PCC (Catlett and Siegel, 2018; Chase et al., 2017; Kramer and Siegel, 2019, 2022; Lange et al., 2020).

Each of these approaches have their strengths and weaknesses, with some better able to predict the relative components of PCC than others (e.g. see the intercomparison and uncertainty analyses by Brewin et al. (2017, 2011)). However, the limitation common to all pigment-based approaches is the use of an imperfect proxy of PCC. HPLC-determined taxonomic marker pigments are imperfect descriptors of natural assemblages, which can co-occur across very different taxonomic groupings and size classes. Their absolute and relative abundances can be strongly affected by numerous environmental and physiological factors, meaning that the empirically derived model relationships may not hold in environments not included in the model training dataset or in a future ocean where phytoplankton pigment organization may be modified substantially compared with present day scenarios (Bracher et al., 2017). Additionally, the spectral-based approaches assume that the only particles responsible for imparting backscattering signatures in remote sensing reflectance are phytoplankton - an assumption that breaks down frequently in optically complex waters that may have non-phytoplankton suspended particles present. Finally, the ecologically based approaches impose preconceived notions of what the proximate controlling factors are in structuring PCC. While these assumptions may hold in some scenarios, the complexity of the interacting factors that control PCC are extremely difficult to accurately generalize (Hutchinson, 1961).

1.2. Study Contribution and

Approach

In this study, we use a scalable, high-performance ensemble learning algorithm; extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) (Chen and Guestrin 2016) to identify phytoplankton community composition from satellite ocean color data. The ensemble aspect of this algorithm makes it more resistant to overfitting and, in terms of interpretability, XGBoost is less opaque than neural networks. Finally, XGBoost is robust to data issues that are problematic for other machine learning models such as neural networks, including highly correlated (spectral) data or data of varying scales.

In previous studies, XGBoost outperformed alternative approaches in applications such as harmful algal bloom detection (Izadi et al. 2021) and phytoplankton biomass estimation (Yan et al. 2025), which suggests the suitability of the approach for remote sensing applications. Our work aligns with the objectives of the PACE mission by contributing an advanced classification algorithm that enhances hyperspectral monitoring of phytoplankton diversity (Zhang et al. 2024). To our knowledge, this is the first application of XGBoost for PCC classification in ocean color remote sensing, offering a robust alternative to traditional retrieval methods.

Our approach was to leverage a large dataset of simulated hyperspectral remote sensing reflectance () and associated environmental variables to improve both the discrimination of functional groups and the quantification of their biomass. Previous remote sensing algorithms often classified only a dominant PCC or broad size class (Mouw et al. 2017) and relied on empirical band relationships that lacked generalizability (Hirata et al. 2011). By utilizing a machine learning framework capable of integrating multiple features, our approach reduces classification errors and enhances retrieval precision. Moreover the application of eXplainable AI (XAI) techniques to relate predictions to their input may further guide future efforts to improve PCC quantification.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Preparation and Feature

Selection

A global ocean physical-biogeochemical model (Gregg and Rousseaux, 2017) was used to simulate

over 31 days corresponding to December 2021. The model was configured to emulate the ocean color instrument (OCI) on the PACE satellite with a spectral resolution of 1 nm spanning 350-750 nm. Specifically, the NASA Ocean Biogeochemical Model (NOBM) was coupled to the Ocean-Atmosphere Spectral Irradiance Model (OASIM). Circulation was simulated using the Poseidon ocean general circulation model. A full description of the model can be found in Arteaga and Rousseaux (2023) and

https://gmao.gsfc.nasa.gov/reanalysis/MERRA-NOBM/model_description.php. We conducted an initial exploratory analysis and observed strong correlations among many of the channels. Therefore, to reduce redundancy while preserving essential spectral information, we retained 51 channels by selecting one channel every ten. A comparison of XGBoost results from the data at 1 nm versus 10 nm resolution (not shown) revealed that subsampling to 10 nm had a negligible effect on model performance metrics. Note that, despite this feature subsampling, spectral features are characterized by a high degree of correlation, suggesting that further dimension reduction, such as principal component analysis, may be needed. However, we opted against applying principal component analysis for two important reasons: 1) to avoid overemphasizing the blue water signal from the extensive open ocean regions present in the simulated global satellite scene, and which could mask coastal processes of interest; and 2) tree-based algorithms such as XGBoost are resilient to input multicollinearity. To further contextualize the ocean color signal, we also included auxiliary environmental variables such as temperature and latitude. Though not available from actual PACE measurements, climatology including temperature could be readily sourced elsewhere to augment observations on hand.

The dataset was divided into training and test sets using an 80/20 split. The training set was exclusively used for model development and hyperparameter optimization (see next section), while the test set was set aside until the final validation of model performance.

2.2. Model Choice

We employed an XGBoost Regressor model with a multi-output regression head to predict simultaneously multiple phytoplankton functional groups as well as total chlorophyll-a concentration. XGBoost is a high-performance, scalable implementation of gradient boosting that has become a popular choice for a wide range of regression and classification tasks (Chen and Guestrin 2016). This approach consists of building an ensemble of decision trees sequentially, where each new tree attempts to correct the errors made by the previous trees. By optimizing a regularized objective function, XGBoost effectively controls overfitting while enhancing prediction accuracy. Its efficient handling of highly correlated data, support for parallel computation, and flexible regularization mechanisms make it particularly well-suited for complex modeling tasks.

2.3. Hyperparameter Optimization and Model

Training

Given the complexity of the problem and the high dimensionality of the input features, it was critical to optimize the hyperparameters to achieve robust performance and prevent overfitting. To this end, we conducted hyperparameter optimization using the Optuna library (Akiba et al. 2019). Specifically, we employed the efficient Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) algorithm (Bergstra et al. 2011). TPE is a Bayesian optimization method that iteratively builds probabilistic models of the hyperparameter space based on past evaluation results. By modeling the distributions of promising and less promising hyperparameter configurations, TPE suggests new parameter sets to explore, focusing the search on regions likely to yield improved performance. To further enhance the efficiency of the optimization process, we utilized Optuna’s MedianPruner with n_warmup_steps=5. This pruner automatically stops unpromising trials during the early stages of training (after at least 5 steps) if their intermediate results indicate they are unlikely to outperform the median performance of completed trials. The optimization step used an objective function to minimize the root mean squared error (RMSE) computed via three-fold cross-validation on the training set. The hyperparameters under investigation are the learning rate, maximum tree depth, number of estimators, subsample ratio, column subsample ratio, and gamma (the minimum loss reduction required to make a further partition on a leaf node);

cf Table 1 for further details. The Bayesian optimization procedure allowed us to efficiently explore the hyperparameter space by leveraging past trial information to prune unpromising candidate parameter sets early, thereby reducing overall computational cost.

Once the optimization step was complete, we instantiated the XGBoost model with the best set of hyperparameters and trained it on the full training set.

2.4. Sensitiviy Analysis of Spectral Resolution through Band

Downsampling

To assess the impact of spectral resolution on model performance, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by subsampling the hyperspectral input data to approximate the band configurations of MODIS and VIIRS sensors. Specifically, we selected the closest available channels in our simulated dataset to match the central wavelengths of MODIS and VIIRS ocean color bands (limited to <750 nm), while retaining temperature as an auxiliary predictor. For both sensor configurations, we trained new models using the original set of hyperparameters optimized for the full hyperspectral dataset. This approach enabled a controlled comparison in which only the input features were varied, allowing us to isolate the impact of reduced spectral resolution on predictive skill. The same train/test split used in the initial model development was retained to ensure comparability of performance metrics across configurations, with the goal of measuring sensitivity rather than generalizability.

2.5. Model Evaluation and eXplainable AI

(XAI)

Once the optimal hyperparameter combination was identified, we retrained the final XGBoost model on the full training set using these optimized settings. Finally, we evaluated the performance of the retrained model on the held-out test set to assess its generalizability.

2.5.1. Prediction

Explainability

To enhance interpretability and gain insights into how different input features influence model predictions, we employed Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), a widely used explainable AI (XAI) framework for interpreting complex machine learning models. SHAP is named after the concept of Shapley values, which consists of assigning importance values to each input feature by estimating its contribution to the model’s predictions across different samples. The method is rooted in cooperative game theory, and guarantees a fair distribution of importance scores among features (Lundberg and Lee 2017).

Given the computational complexity of our XGBoost model and the high dimensionality of the dataset, we conducted SHAP analysis on a random subsample of 10,000 observations from the test set. This subset was selected to balance computational feasibility while maintaining a representative sample of phytoplankton spectral diversity.

We generated SHAP summary plots, which provide a comprehensive visualization of feature importance and the directionality of their influence on model outputs. These plots display the magnitude of each feature’s impact across all predictions, helping to identify the most influential spectral and environmental variables in determining phytoplankton functional group composition. The insights gained from SHAP analysis aid in validating model behavior and ensuring its ecological plausibility.

2.5.1.1. Code Availability

3. Results

3.1. Hyperparameter Optimization

(HPO)

We performed hyperparameter optimization using a Bayesian optimization framework implemented with Optuna. The metric used for optimization was the average RMSE (in units of ) computed over the cross-validation folds and across all target compartments. The “full HPO run” best parameters indicate a relatively aggressive model, characterized by deep trees with many estimators, a moderate learning rate, and little regularization via gamma.

The best trial finished with an RMSE of . Below is the list of hyperparameters researched, the optimal values found, and an interpretation of these values:

Learning Rate (learning_rate): - This moderate learning rate suggests the model takes reasonably sized steps when updating that are neither too aggressive (which might lead to overshooting the optimum) nor too conservative (which could slow down convergence).

Max Depth (max_depth): 10 - A depth of 10 allows the trees to capture complex interactions. This may indicate that the data has non-linear relationships that benefit from deeper trees. Such a depth can be associated with overfitting. The cross-validation process during HPO should minimize this, however.

Number of Estimators (n_estimators): 466 -Building around 466 trees indicates the ensemble haa to tackle inherent complexity in the data that was not apparetn during the Exploratory Data Analysis phase. A larger number of trees generally improves performance—up to a point before overfitting becomse a risk. This number in conjunction with the cross validation process suggest this number strikes a balance between performance and overfitting.

Subsampling (subsample): - This indicates each of the 466 trees is using roughly 66% of the data. This introduces randomness that helps prevent overfitting as not all samples in any cross-validation fold are used to build every tree.

Features used per tree (colsample_bytree): - Using about 89% of the features per tree indicates that most features are informative, and the model is allowed to consider almost the full feature set at each split. - See features used in the Methods section.

Gamma (gamma): - An extremely low gamma value means that almost no minimum loss reduction is required to make a split. This implies that the algorithm will split more readily, potentially capturing fine details. Awareness of this hyperparameter values is important as low gamma can risk overfitting.

3.2. Optimized Model

Validation

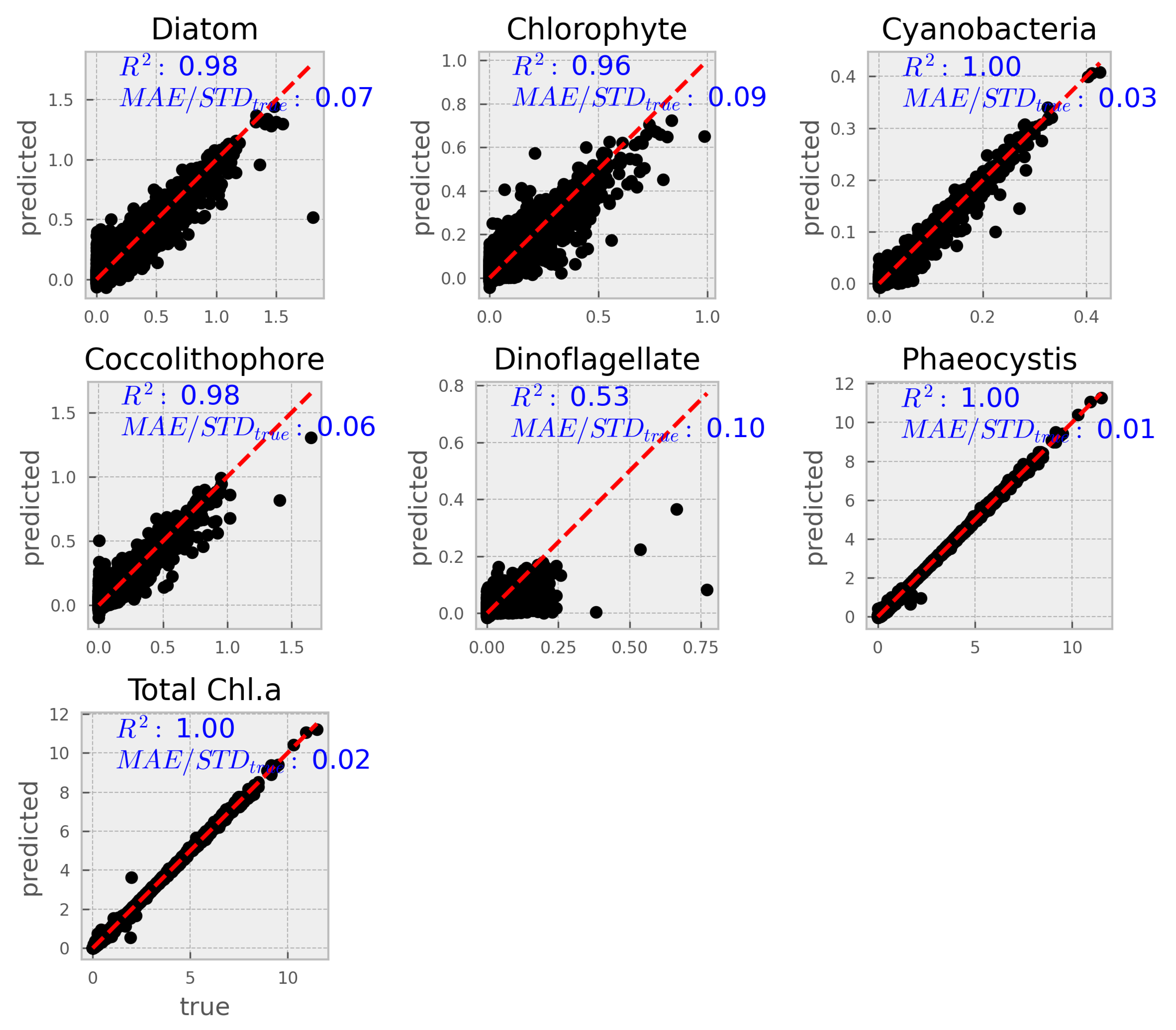

The next step was to load the best set of hyperparameters (listed above) into the model and retrain it on the entire training set. The resulting optimized model was then validated using the test set, which had been set aside before the hyperparameter optimization (HPO) process.

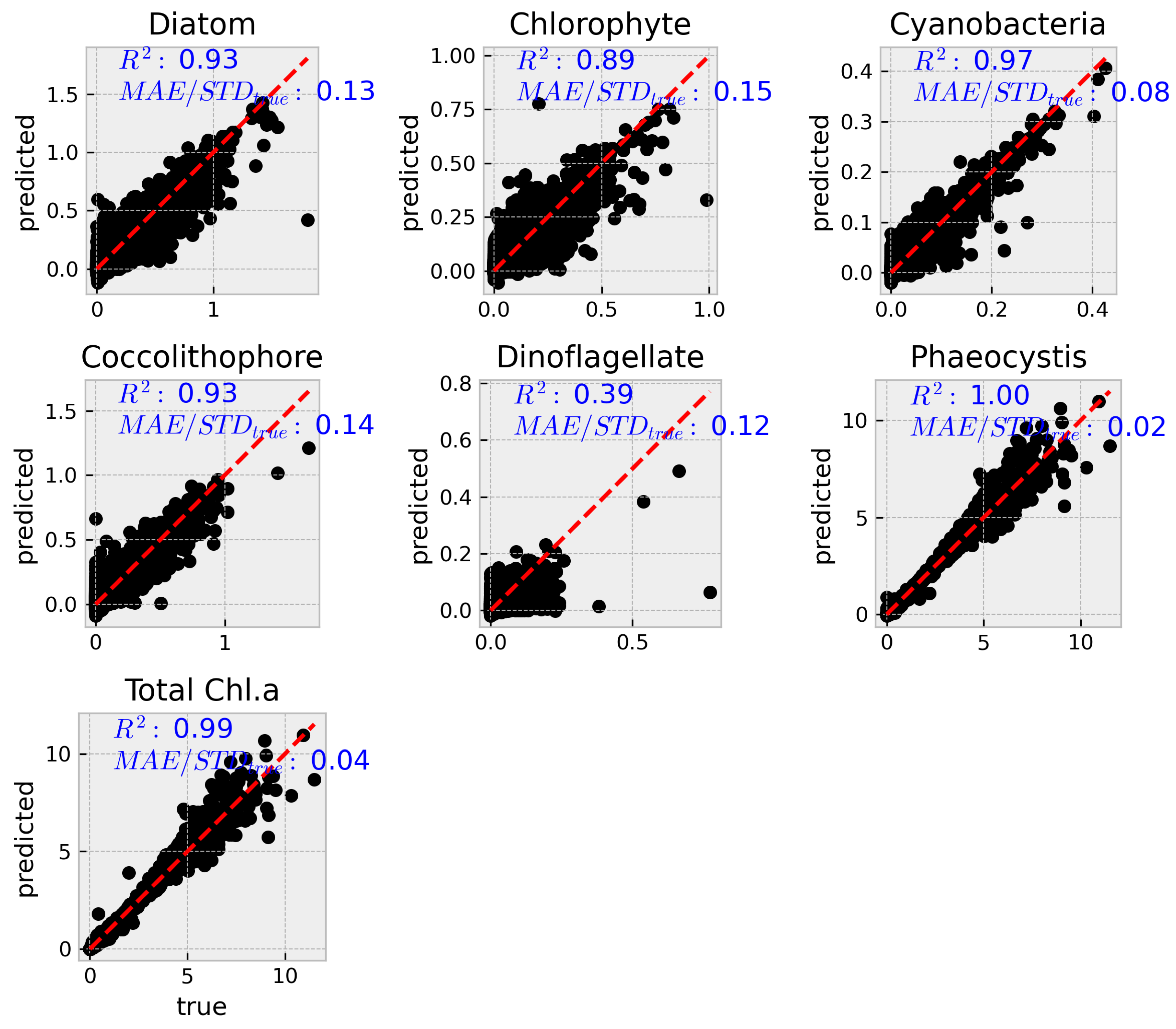

A more complete set of metrics are summarized in table

Table 2 See further below for metrics explanation.

3.2.1. Explanation of metrics

-

Mean Squared Error (MSE):

MSE is the average of the squared differences between the predicted and true values. Squaring the errors emphasizes larger deviations, making MSE sensitive to outliers. In our context, MSE is expressed in units of (mg m−3 Chl a)2. Lower MSE values indicate better model performance.

-

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE):

RMSE is the square root of the MSE, bringing the error metric back to the original units (mg m−3 Chl a)2. It provides a direct measure of the average prediction error magnitude. Lower RMSE values suggest that the model’s predictions are closer to the true values.

-

Mean Absolute Error (MAE):

MAE calculates the average absolute difference between predicted and true values. Unlike MSE, it does not square the errors, so it is less sensitive to large outliers. MAE is also expressed in the same units as the target variable (mg m−3 Chl a)2. A lower MAE indicates better predictive accuracy.

-

Coefficient of Determination (R-squared):

R-squared measures the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. It ranges from 0 to 1, where a value closer to 1 indicates that the model explains a high proportion of the variance in the data. In our results, high R-squared values generally indicate strong model performance, although lower values (e.g., for dinoflagellates) suggest room for improvement.

-

MAE/StDevtrue:

This ratio compares the mean absolute error to the standard deviation of the true values. It provides a relative measure of error by indicating how the average error compares to the inherent variability in the data. A lower ratio implies that the model’s prediction error is small relative to the natural variability of the observations.

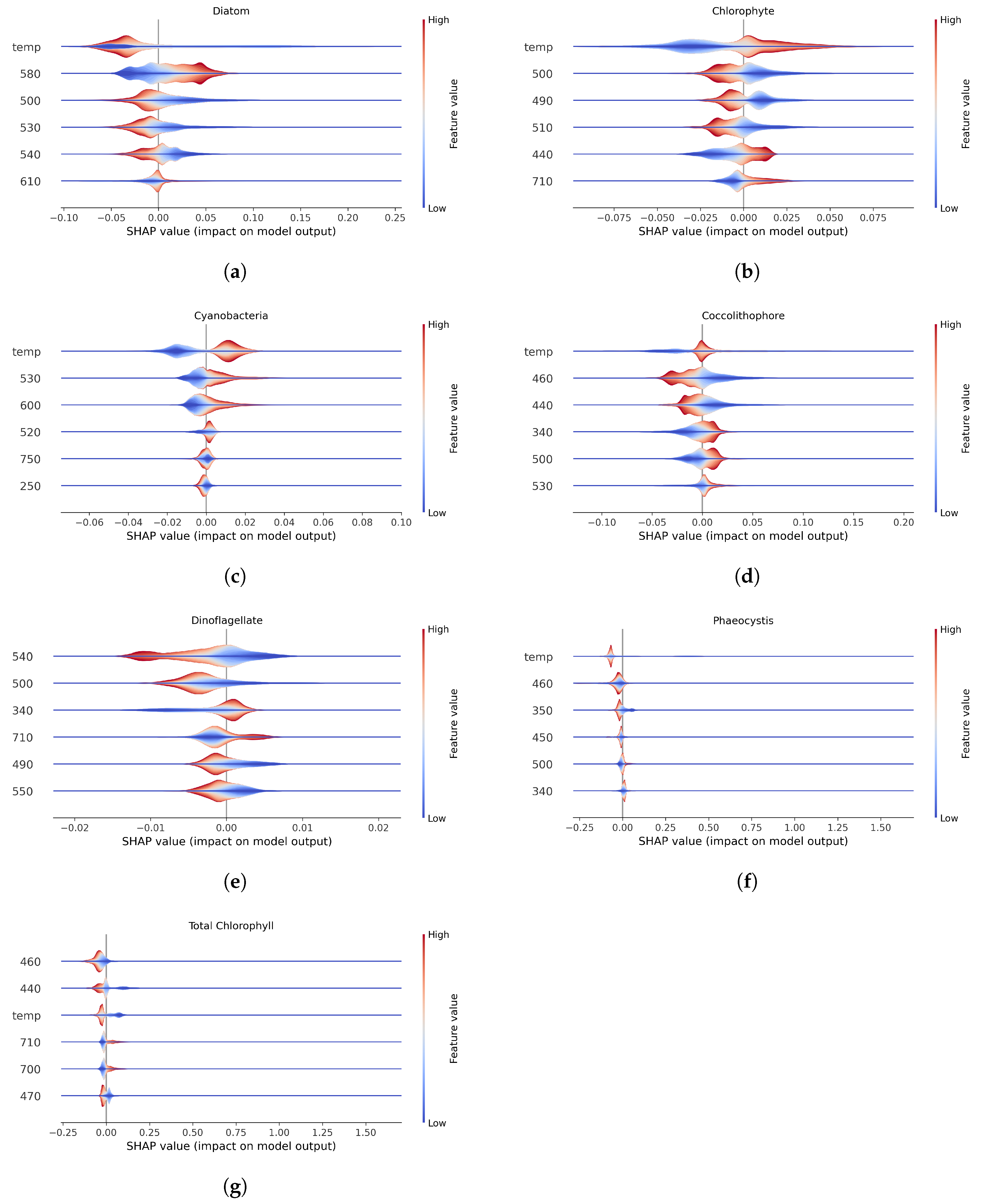

3.3. XAI with Shapley Values

The SHAP summary plots (

Figure 2) provides insights into feature importance and their effects on model predictions for phytoplankton community composition. Features are ordered by overall importance, from most to least impactful (top to bottom). Each horizontal violin plot shows the distribution of SHAP values for a given feature across all observations. The x-axis represents SHAP values, which quantify how much each feature contributes to the model’s prediction relative to a baseline. A SHAP value of 0 means the feature has no effect on the prediction for that observation—i.e., the model’s output would be the same whether or not that feature were included. Positive SHAP values indicate that the feature increases the predicted chlorophyll-a concentration; negative values indicate a decreasing effect. The thickness of the violin at each x-position reflects the density of observations with similar SHAP values—wider sections indicate more frequent effect sizes. Color represents the original feature value for each observation (red = high, blue = low). The midpoint of the color scale is defined by a percentile-based central value and does not necessarily reflect the mean or median.

Most saliently, temperature was the top factor for all phytoplankton groups but is not a primordial feature in quantifying dinoflagellates. This is unsurprising given that the model used to generate the synthetic dataset uses temperature to drive mixing rates, ocean mixed layer depths, and thus, nutrient availability. Dinoflagellates emerge once iron has been depleted by diatom growth, which may correspond with a shoaling mixed layer and, sometimes, increased temperature. In short, the processes driving dinoflagellate growth are complex and non-linear (Arteaga and Rousseaux, 2023) and, at least for this dataset, the XGBoost approach does not accurately predict their abundance.

3.4. Spectral Resolution Sensitivity

Analysis

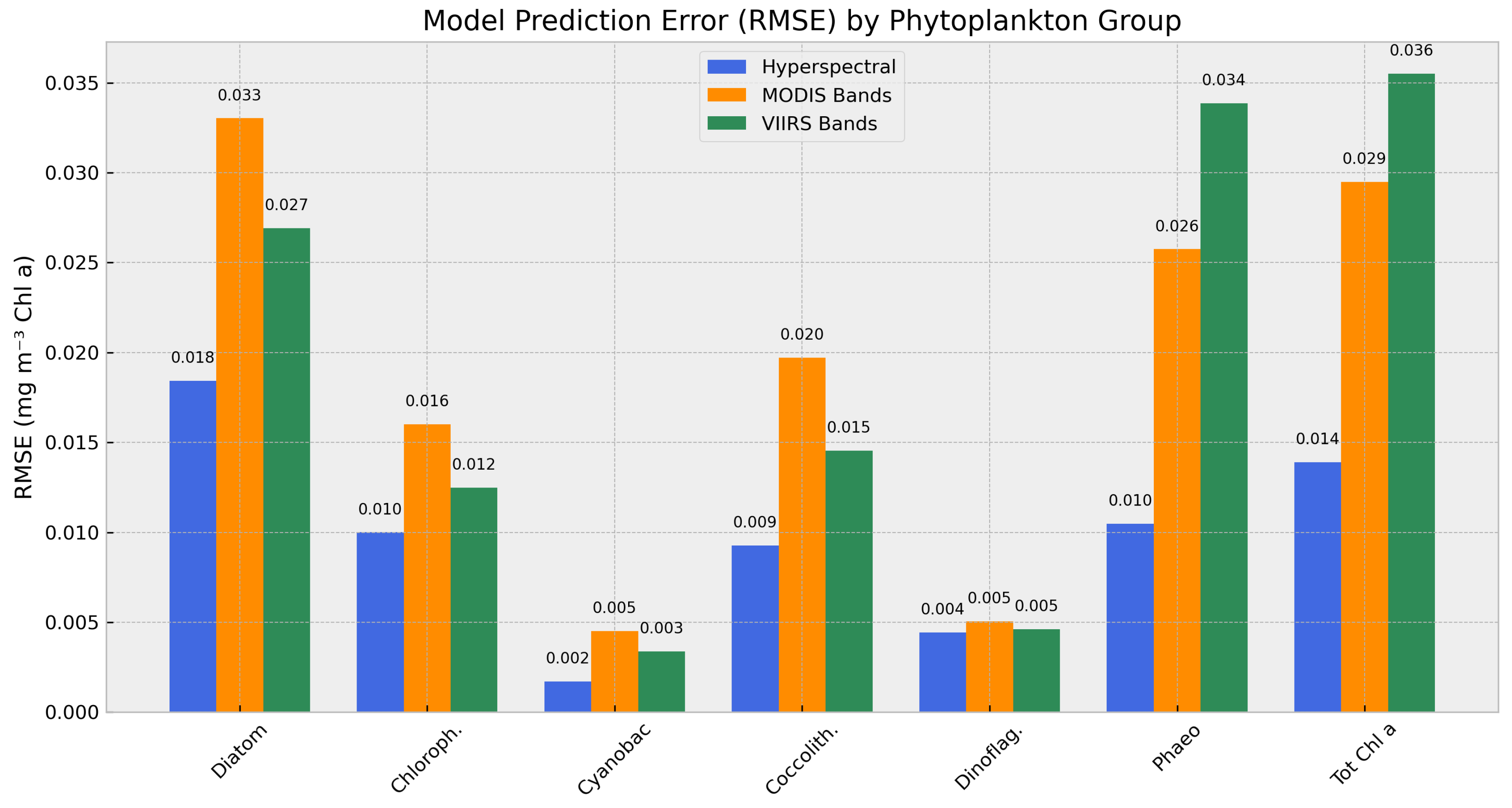

To evaluate the sensitivity of model performance to spectral input resolution, we conducted additional experiments using reduced-band versions of the input data, corresponding to the band configurations of the MODIS and VIIRS ocean color sensors. For each sensor-specific dataset, we selected the closest matching channels from the original simulated hyperspectral inputs (limited to <750 nm), while retaining temperature as an auxiliary predictor.

All modeling conditions—hyperparameters, training procedure, and the original 80/20 train-test split—were held constant to isolate the effect of spectral resolution. Model performance was evaluated using multiple regression metrics across PCCs, including diatoms, chlorophytes, cyanobacteria, coccolithophores, dinoflagellates, and prasinophytes, as well as total chlorophyll-a.

Figure 3 summarizes the RMSE values for each model configuration. As expected, both band-limited models showed increased prediction error relative to the full hyperspectral model. The MODIS-band model exhibited an RMSE increase of 1.5–2.5× across most groups, with declines in R² particularly evident for diatoms, coccolithophores, and total chlorophyll. The VIIRS-band model showed consistently lower errors and higher explained variance than the MODIS counterpart, indicating better preservation of model skill under reduced spectral input. This reinforces the fact that hyperspectral resolution, even at the 10 nm subsetting used in this study, significantly improves our ability to differentiate phytoplankton groups - a fact that was often questioned during the formulation stage of hyperspectral missions such as PACE.

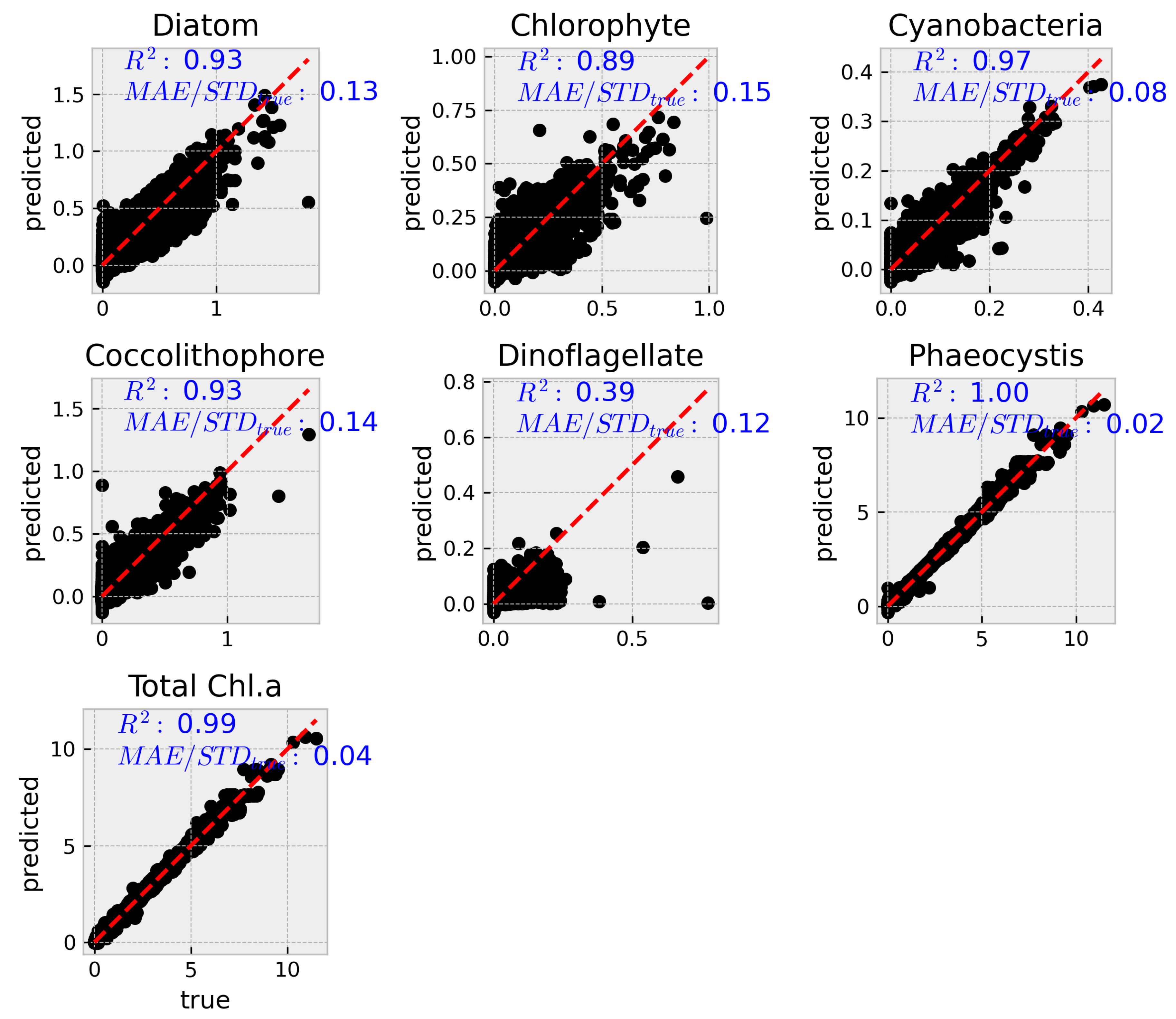

To complement the aggregated metrics,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show predicted versus true values for each group using the MODIS and VIIRS subsets, respectively. While both reduced models show reasonable alignment along the 1:1 line, greater scatter and bias are evident relative to the hyperspectral model, particularly for diatoms and dinoflagellates.

4. Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate that machine learning, specifically XGBoost, can effectively predict phytoplankton community composition (PCC) and the respective abundances for each group, along with total chlorophyll a from hyperspectral and auxiliary variables. The model performed well across most phytoplankton groups, with root mean squared error (RMSE) values under and values exceeding 0.95. The exception was dinoflagellates, which exhibited significantly lower predictive accuracy (), a result also reflected in their higher normalized MAE and MAPE values.

Feature importance analysis using SHAP values revealed that temperature was among the top six predictors for all groups except dinoflagellates, for which no strong dependence on any single environmental feature emerged. These patterns point to functional differences in ecological drivers between phytoplankton groups. In particular, the centrality of temperature for most groups highlights its role as a proxy for environmental gradients, biogeography, and metabolic scaling, or, in other words, a ’holistic simplifier’ (Craig et al. 2015; Li et al., 2006; Morán et al., 2010).

The strength of the model, particularly for diatoms, coccolithophores, and phaeocystis, suggests that important spectral and environmental signals are being captured despite substantial dimensionality reduction. This supports the feasibility of operational PCC prediction using compressed hyperspectral data, especially when paired with interpretable machine learning models.

It should be noted that this study is based on simulated , and real world deployment will depend on atmospheric correction, instrument fidelity, and access to reliable ancillary predictors. Future work should validate the model on real PACE observations and incorporate additional features—such as nutrient proxies, light attenuation, and mixed layer depth—to better capture ecological dynamics across all functional groups.

5. Conclusion

This study presents a novel, explainable machine learning framework for predicting the abundance of six phytoplankton groups from simulated hyperspectral . Using an XGBoost model trained on reduced spectral features and auxiliary inputs such as temperature and latitude, we achieved high predictive performance across most functional groups and total chlorophyll-a. Model interpretation using SHAP values revealed that temperature was a key predictor for all groups except dinoflagellates, whose distribution appears to be driven by a broader suite of ecological factors such as stratification, nutrient limitation, and mixotrophy.

These findings reinforce the importance of tailoring remote sensing algorithms to the ecological and physiological diversity of phytoplankton groups. They also demonstrate that physically interpretable, high-performing models can be built even when using compressed hyperspectral inputs. However, the data tested is still simulated. Confirmation studies focusing on real sensor data (e.g., from the PACE mission) and incorporating additional oceanographic predictors to improve performance across all phytoplankton groups—especially those, like dinoflagellates, whose success is governed by indirect or emergent environmental conditions.

References

- Akiba, Takuya, Shotaro Sano, Toshihiko Yanase, Takeru Ohta, and Masanori Koyama. 2019. “Optuna: A Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework.” In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), 2623–31. ACM. [CrossRef]

- Alvain, S., C. Moulin, Y. Dandonneau, and F. M. Bréon. 2005. “Remote Sensing of Phytoplankton Groups in Case 1 Waters from Global SeaWiFS Imagery.” Deep-Sea Research I 52 (11): 1989–2004. [CrossRef]

- Alvain, S., C. Moulin, Y. Dandonneau, and H. Loisel. 2008. “Seasonal Distribution and Succession of Dominant Phytoplankton Groups in the Global Ocean: A Satellite View.” Global Biogeochemical Cycles 22 (3): GB3S04. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Thomas R, Erik T Buitenhuis, Corinne Le Quéré, and Andrew Yool. 2021. “Marine Phytoplankton Functional Types Exhibit Diverse Responses to Thermal Change.” Nature Communications 12 (1): 5126. [CrossRef]

- Bergstra, James, Rémi Bardenet, Yoshua Bengio, and Balázs Kégl. 2011. “Algorithms for Hyper-Parameter Optimization.” In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, edited by J. Shawe-Taylor, R. Zemel, P. Bartlett, F. Pereira, and K. Q. Weinberger. Vol. 24. Curran Associates, Inc. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2011/file/86e8f7ab32cfd12577bc2619bc635690-Paper.pdf.

- Bopp, L., O. Aumont, P. Cadule, S. Alvain, and M. Gehlen. 2005. “Response of Diatoms Distribution to Global Warming and Potential Implications: A Global Model Study.” Geophysical Research Letters 32 (19): L19606. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, P. W. , and S. C. Doney. 2002. “Modelling Regional Responses by Marine Pelagic Ecosystems to Global Climate Change.” Geophysical Research Letters 29 (19): 53-1-53-4. [CrossRef]

- Brewin, R. J. W., S. Sathyendranath, T. Hirata, S. J. Lavender, R. Barciela, and N. J. Hardman-Mountford. 2010. “A Three-Component Model of Phytoplankton Size Class for the Atlantic Ocean.” Ecological Modelling 221 (11): 1472–83. [CrossRef]

- Buitenhuis, Erik T. et al. 2013. “Biogeochemical Fluxes Through Microzooplankton.” Global Biogeochemical Cycles 27 (3): 847–58. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Tianqi, and Carlos Guestrin. 2016. “XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System.” In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), 785–94. [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, A. M., M. R. Lewis, and J. J. Cullen. 2002. “Assessment of the Relationships Between Dominant Cell Size in Natural Phytoplankton Communities and the Spectral Shape of the Absorption Coefficient.” Limnology and Oceanography 47 (2): 404–17. [CrossRef]

- Dierssen, H. M., M. M. Gierach, L. S. Guild, A. Mannino, J. Salisbury, S. Schollaert Uz, J. Scott, et al. 2023. “Synergies Between NASA’s Hyperspectral Aquatic Missions PACE, GLIMR, and SBG: Opportunities for New Science and Applications.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 128 (10): e2023JG007574. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Kevin J. et al. 2013. “Misuse of the Phytoplankton–Zooplankton Dichotomy: The Need to Assign Organisms as Mixotrophs Within Plankton Functional Types.” Journal of Plankton Research 35 (1): 3–11. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Feixue et al. 2012. “Interactions Between Changing pCO2, n Availability, and Temperature on the Marine Nitrogen Fixer Trichodesmium.” Global Change Biology 18 (10): 3079–92. [CrossRef]

- Glibert, Patricia M. 2020. “Harmful Algal Blooms: A Climate Change Co-Stressor in Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems.” Harmful Algae 91: 101590. [CrossRef]

- Glibert, Patricia M. et al. 2001. “The Role of Eutrophication in the Global Proliferation of Harmful Algal Blooms.” Oceanography 14 (2): 66–74. [CrossRef]

- Gregg, Watson W., and Cecile S. Rousseaux. 2019. “Decadal Changes in Global Phytoplankton Composition: Observations and Modeling.” Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 124 (2): 983–1003. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T., N. J. Hardman-Mountford, R. J. W. Brewin, J. Aiken, R. Barlow, K. Suzuki, T. Isada, et al. 2011. “Synoptic Relationships Between Surface Chlorophyll-a and Diagnostic Pigments Specific to Phytoplankton Functional Types.” Biogeosciences 8 (2): 311–27. [CrossRef]

- IOCCG. 2014. Phytoplankton Functional Types from Space.

- Izadi, Moein, Mohamed Sultan, Racha El Kadiri, Amin Ghannadi, and Karem Abdelmohsen. 2021. “A Remote Sensing and Machine Learning-Based Approach to Forecast the Onset of Harmful Algal Bloom.” Remote Sensing 13 (19): 3863. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Hae Jin et al. 2010. “Mixotrophy in the Marine Dinoflagellate Population: Physiological Roles, Relationships, and Regulation.” Harmful Algae 9 (2): 154–65. [CrossRef]

- Kibler, Sarah R. et al. 2015. “Geographic and Vertical Distribution of Dinoflagellates in the Gulf of Mexico.” Journal of Phycology 51 (4): 606–18. [CrossRef]

- Laufkötter, C., M. Vogt, N. Gruber, O. Aumont, L. Bopp, S. C. Doney, J. P. Dunne, et al. 2016. “Projected Decreases in Future Marine Export Production: The Role of the Carbon Flux Through the Upper Ocean Ecosystem.” Biogeosciences 13 (13): 4023–47. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, Scott M., and Su-In Lee. 2017. “A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions.” In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 30:4768–77. Curran Associates, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Marañón, E. , and Mouriño-Carballido B. Cermeño P. Huete-Ortega M. López-Sandoval D. C. 2014. “Resource Supply Overrides Temperature as a Controlling Factor of Marine Phytoplankton Growth.” PLoS ONE 10 (6). [CrossRef]

- Mouw, Colleen B., Neil J. Hardman-Mountford, Sylvie Alvain, Astrid Bracher, Robert J. W. Brewin, Annick Bricaud, Aurea M. Ciotti, et al. 2017. “A Consumer’s Guide to Satellite Remote Sensing of Multiple Phytoplankton Groups in the Global Ocean.” Frontiers in Marine Science 4: 41. [CrossRef]

- Peperzak, Louis. 2003. “Climate Change and Harmful Algal Blooms in the North Sea.” ICES Journal of Marine Science 60 (2): 271–76. [CrossRef]

- Smayda, Theodore J., and Colin S. Reynolds. 2001. “Community Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms in Coastal Upwelling Ecosystems.” ICES Journal of Marine Science 58 (2): 374–76. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Zhaojiang, Chong Fang, Kaishan Song, Xiangyu Wang, Zhidan Wen, Yingxin Shang, Hui Tao, and Yunfeng Lyu. 2025. “Spatiotemporal Variation in Biomass Abundance of Different Algal Species in Lake Hulun Using Machine Learning and Sentinel-3 Images.” Scientific Reports 15: 2739. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yuan, Fang Shen, Renhu Li, Mengyu Li, Zhaoxin Li, Songyu Chen, and Xuerong Sun. 2024. “AIGD-PFT: The First AI-Driven Global Daily Gap-Free 4 Km Phytoplankton Functional Type Data Product from 1998 to 2023.” Earth System Science Data 16: 4793–4816. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).