Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Concept | Physical Definition | Pulmonary Application | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | Force per unit area (f/A) | Transpulmonary pressure (PTP) | cmH₂O |

| Strain | Relative deformation (dX-dX₀)/dX₀ | Tidal volume/Functional residual capacity (VT /FRC) | Dimensionless |

| Strain rate | Deformation velocity | Flow/FRC | s⁻¹ |

| Young's Modulus (EY) | Proportionality constant between stress and strain | Specific lung elastance (ESL) | cmH₂O |

| Driving pressure (DP) | Difference between plateau pressure and PEEP | Clinical approximation to pulmonary stress | cmH₂O |

| Mechanical power (MP) | Energy per unit time | Energy delivered to respiratory system per minute | J/min |

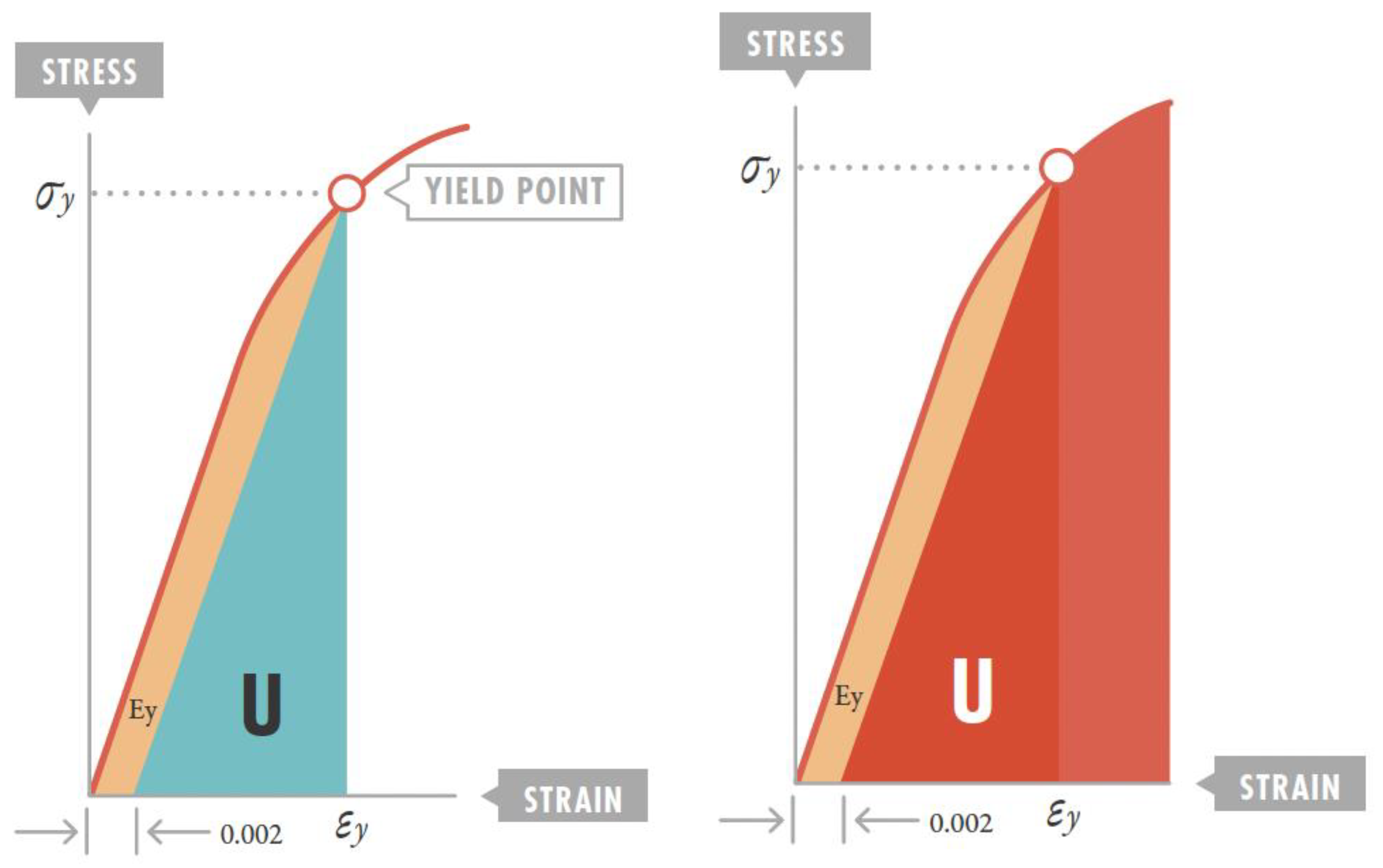

| Resilience | Maximum energy storable without permanent deformation | Energy threshold to prevent VILI | J/m³ |

2. Refutation of Classical VILI Theories. New VILI Concepts

3. New VILI Concepts Related to Rheological Theory

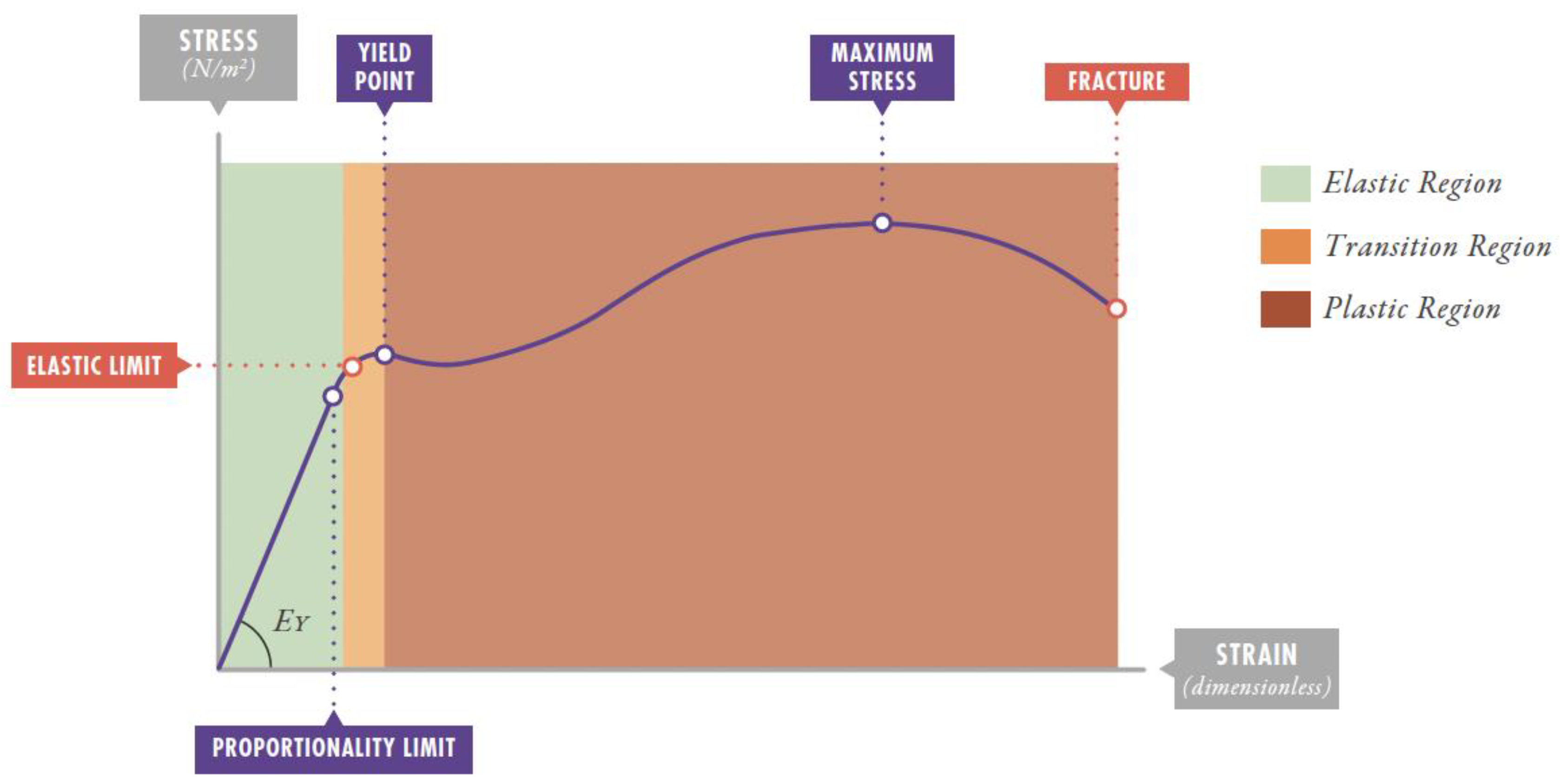

3.1. The Lung as an Elastic Solid

3.2. Strain Threshold and VILI Development

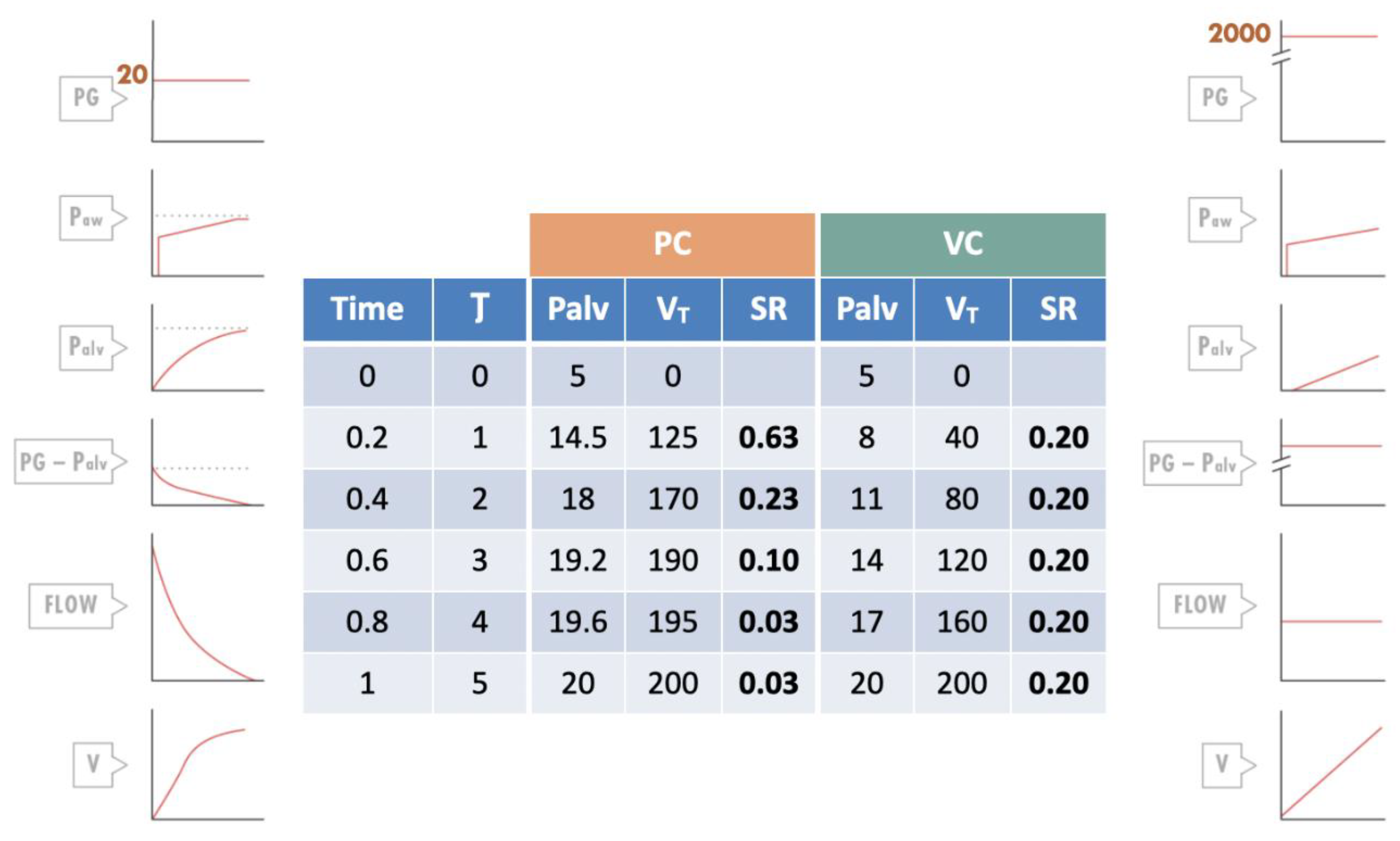

3.3. Stress and Strain Estimation with the Ventilator

3.4. Mechanical Power and Injury Threshold

4. Ventilatory Strategy in ARDS from Rheological Perspective

4.1. Mechanical Power Adjustment by Ideal Weight or Compliance

- Normalized MP (J/min/kg) = Total MP (J/min)/Ideal weight (kg).

- Specific MP (J/min/L) = Total MP (J/min)/Static compliance (L/cmH₂O)

4.2. VILI Development Dynamics and Recruitment. Optimal PEEP

4.3. Importance of Respiratory Rate

4.4. Importance of Flow

4.5. Importance of Ventilatory Mode

4.6. Tidal Volume and Driving Pressure

4.7. Resilience Implication in ARDS Ventilatory Strategy

4.8. Self-Inflicted Lung Injury (SILI)

5. Rheological Model Limitations

5.1. Regional Lung Variability Not Captured by the Model

5.2. Interaction Between Mechanical Ventilation and Inflammation Not Completely Explained

5.3. Challenges for Determining the "Baby Lung" Precisely at Patient Bedside

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.H. Polymer viscoelasticity. Basics, molecular theories and simulations. 2nd ed Singapur: World Scientific Publishing Co; 2011.

- Mead, J.; Takishima, T.; Leith, D. Stress distribution in lungs: A model of pulmonary elasticity. J Appl Physiol. 1970, 28, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesto, I.; Alapont, V.; Aguar Carrascosa, M.; Medina Villanueva, A. Stress, strain and mechanical power: Is material science the answer to prevent ventilator induced lung injury? Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2019, 43(3), 165-175.

- Modesto i Alapont, V.; Medina Villanueva, A.; Aguar Carrascosa, M.; et al. Stress, strain y potencia mecánica. La ciencia para prevenir la lesión inducida por el ventilador (VILI). Apéndice 1. Manual de Ventilación Mecánica Pediátrica y Neonatal. e-book. 6ª edición. Tesela Ediciones; 2022.

- Pilkey, W.D. Formulas for stress, strain and structural matrices. 2 nd ed John, Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2005.

- Cortés-Puentes, G.A.; Keenan, J.C.; Adams, A.B.; et al. Impact of chest wall modifications and lung injury on the correspondence between airway and transpulmonary driving pressure. Crit Care Med. 2015, 43, e287–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiumello, D.; Carlesso, E.; Brioni, M.; et al. Airway driving pressure and lung stress in ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2016, 20, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gattinoni, L.; Tonetti, T.; Cressoni, M.; et al. Ventilator-related causes of lung injury: the mechanical power. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 1567–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfuss, D.; Saumon, G. Ventilator-induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998, 157, 294–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network; Brower, R. G.; Matthay, M.A.; Morris, A.; et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342, 1301–8.

- Amato, MBP, Barbas, CSV, Medeiros, DM, et al. Beneficial effects of the “open lung approach“ with low distending pressures in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective randomized study on mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995, 152, 1835–46.

- Slutsky, A.; Tremblay, L. Multiple system organ failure: is mechanical ventilation a contributing factor? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998, 157, 1721–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutsky, A.S.; Ranieri, V.M. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2013, 369, 2126–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González López, A.; Garcia Prieto, E.; Batalla Solís, E.; et al. Lung strain and biological response in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 240–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahaman, U. Mathematics of ventilator-induced lung injury. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017, 21, 521–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffey, J.F.; Bellani, G.; Pham, T.; et al. Potentially modificable factors contributing to outcome from acute respiratory distress syndrome: the LUNG SAFE study. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 1865–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.B.P.; Meade, M.O.; Slutsky, A.S.; et al. Driving pressure and survival in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 747–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protti, A.; Votta, E.; Gattinoni, L. Which is the most important strain in the pathogenesis of ventilator-induced lung injury: dynamic or static? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014, 20, 33–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Carlesso, E.; Cadringher, P.; et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 178, 346–55. [Google Scholar]

- Protti, A.; Cressoni, M.; Santini, A.; et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation: Any safe threshold? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011, 183, 1354–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Carlesso, E.; Cadringher, P.; et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008, 178, 346–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chiumello, D.; Chidini, G.; Calderini, E.; et al. Respiratory mechanics and lung stress/strain in children with acute respiratory distres syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2016, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiumello, D.; Carlesso, E.; Brioni, M.; Cressoni, M. Airway driving pressure and lung stress in ARDS patients. Critical Care. 2016, 20, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, C.; Roberts, F. Anaesthesia data. En: Allman, K.; editor. Oxford Handbook of anesthesia. 4 th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Cressoni, M. ; Chiurazzi Ch, Gotti M et al. Lung inhomogeneities and time-course of ventilator-induced mechanical injuries. Anesthesiology. 2015, 123, 618–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gattinoni, L.; Tonetti, T.; Cressoni, M.; et al. Ventilator-related causes of lung injury: the mechanical power. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 1567–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppola, S.; Caccioppola, A.; Froio, S.; et al. Effect of mechanical power on intensive care mortality in ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2020, 24, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.L.V.; Slutsky, A.S.; Brochard, L.J.; et al. Ventilatory variables and mechanical power in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021, 204, 303–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Takeuchi, M.; Inata, Y.; et al. Normalization to Predicted Body Weight May Underestimate Mechanical Energy in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022, 205, 1360–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonetti, T.; Vasques, F.; Rapetti, F.; et al. Driving pressure and mechanical power: new targets for VILI prevention. Ann Transl Med. 2017, 5, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilia, S.; Geromarkaki, E.; Briassoulis, P.; et al. Effects of increasing PEEP on lung stress and strain in children with and without ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 1315–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilia, S.; Geromarkaki, E.; Briassoulis, P.; et al. Longitudinal PEEP Responses Differ Between Children With ARDS and at Risk for ARDS. Respir Care. 2021, 66, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Marini, J.J.; Pesenti, A.; et al. The "baby lung" became an adult. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 42, 663–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpa Neto, A.; Deliberato, R.O.; Johnson, A.E.W.; et al. Mechanical power of ventilation is associated with mortality in critically ill patients: an analysis of patients in two observational cohorts. Intensive Care Med. 2018, 44, 1914–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, T.; van der Staay, M.; Schädler, D.; et al. Calculation of mechanical power for pressure-controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45(9), 1321–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumello, D.; Gotti, M.; Guanziroli, M.; et al. Bedside calculation of mechanical power during volume- and pressure-controlled mechanical ventilation. Crit Care. 2020, 24(1), 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, S.; Caccioppola, A.; Froio, S.; et al. Effect of mechanical power on intensive care mortality in ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2020, 24, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giosa, L.; Busana, M.; Pasticci, I.; et al. Mechanical power at a glance: a simple surrogate for volume-controlled ventilation. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2019, 7(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protti, A.; Andreis, D.T.; Monti, M.; Santini, A.; Sparacino, C.C.; Langer, T.; et al. Lung stress and strain during mechanical ventilation: Any difference between statics and dynamics? g Crit Care Med. 2013(41), 1046–1055. [CrossRef]

- Modesto, I.; Alapont, V.; Aguar Carrascosa, M.; Medina Villanueva, A. Clinical implications of the rheological theory in the prevention of ventilator-induced lung injury. Is mechanical power the solution? Med Intensiva. 2019, 43(6), 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Gordo-Vidal, F.; Gómez-Tello, V.; Palencia-Herrejón, E.; et al. PEEP alta frente a PEEP convencional en el síndrome de distrés respiratorio agudo. Revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Med Intensiva. 2007, 31, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farías, J.A.; Frutos, F.; Esteban, A.; et al. What is the daily practice of mechanical ventilation in pediatric intensive care units? A multicenter study. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30, 918–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.; Valente Barbas, C.S.; Machado Medeiros, D.; et al. Effect of a Protective-Ventilation Strategy on Mortality in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998, 338, 347–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, V.M.; Suter, P.M.; Tortorella, C.; et al. Effect of mechanical ventilation on inflammatory mediators in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999 Jul 7;282, 54-61.

- Villar, J.; Kacmarek, R.M.; Pérez-Méndez, L.; et al. A high positive end- expiratory pressure, low tidal volume ventilatory syndrome: A randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2006, 34, 1311–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caramez, M.P.; Kacmarek, R.M.; Helmy, M.; et al. A comparison of methods to identify open-lung PEEP. Intensive Care Med. 2009, 35, 740–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modesto i Alapont, V.; Medina Villanueva, A.; Del Villar Guerra, P.; et al. OLA strategy for ARDS: Its effect on mortality depends on achieved recruitment (PaO₂/FIO₂) and mechanical power. Systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed). 2021, S0210-5691(21)00075-9.

- Brower, R.G.; Morris, A.; Maclntyre, N.; et al. Effects of recruitment maneuvers in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome ventilated with high positive end-expiratory pressure. Crit Care Med. 2003, 31, 2592–7. [Google Scholar]

- Meade, M.O.; Cook, D.J.; Guyatt, G.H.; et al. Ventilation strategy using low tidal volumes, recruitment maneuvers, and high positive end-expiratory pressure for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008, 299, 637–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercat, A.; Richard, J.C.; Vielle, B.; et al. Expiratory Pressure (Express) Study Group. Positive end-expiratory pressure setting in adults with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008, 299, 646–55. [Google Scholar]

- Briel, M.; Meade, M.; Mercat, A.; et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010, 303, 865–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putensen, C.; Theuerkauf, N.; Zinserling, J.; et al. Meta-analysis: ventilation strategies and outcomes of the acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute lung injury. Ann Intern Med. 2009, 151, 566–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotchkiss, J.R.; Blanch, L.; Murias, G.; Adams, A.B.; Olson, D.A.; Wangensteen, O.D.; et al. Effects of decreased respiratory frequency on ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Resp Crit Care Med., 2000 (161), 463-468.

- Retamal, J.; Borges, J.B.; Bruhn, A.; et al. Open lung approach ventilation abolishes the negative effects of respiratory rate in experimental lung injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016, 60, 1131–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protti, A.; Maraffi, T.; Milesi, M.; et al. Role of Strain rate in the pathogenesis of Ventilator-Induced Lung Edema. Crit Care Med. 2016, 44, e838–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Fujino, Y.; Uchiyama, A.; Matsuura, N.; Mashimo, T.; Nishimura, M. Effects of peak inspiratory flow on development of ventilator-induced lung injury in rabbits. Anesthesiology. 2004(101), 722–728. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Maeda, Y.; Fujino, Y.; Uchiyama, A.; Mashimo, T.; Nishimura, M. Effect of peak inspiratory flow on gas echange, pulmonary mechaniccs and lung histology in rabbits with injured lungs. J Anesth. 2006(20), 96–101.

- Fujita, Y.; Fujino, Y.; Uchiyama, A.; Mashimo, T.; Nishimura, M. High peak inspiratory flow can aggravate ventilator-induced lung injury. Med Sci Monit. 2007; (13):BR95-BR100. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.; Wenzel, C.; Spassov, S.; et al. Flow-controlled ventilation attenuates lung injury in a porcine model of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a preclinical randomized controlled study. Crit Care Med. 2020, 48, e241–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, J.; Kacmarek, R.M.; Hedenstierna, G. From ventilator-induced lung injury to physician-induced lung injury: why the reluctance to use small tidal volumes? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004, 48, 267–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutsky, A.S. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the ACCP and the SCCM. Consensus conference on mechanical ventilation January 28-30, 1993 at Northbrook, Illinois, USA. Part, I.I. Intensive Care Med. 1994, 20, 150–62. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, M.D.; Thompson, T.; Hudson, L.D.; et al. Efficacy of low tidal volume ventilation in patients with different clinical risk factors for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001, 164, 231–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, E.; Del Sorbo, L.; Goligher, E.C.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: Mechanical Ventilation in Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017, 195, 1253–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emeriaud, G.; López-Fernández, Y.M.; Iyer, N.P.; et al. Executive Summary of the Second International Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PALICC-2). Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2023, 24, 143–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneyber, M.C.J.; de Luca, D.; Calderini, E.; et al. Recommendations for mechanical ventilation of critically ill children from the Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation Consensus Conference (PEMVECC). Intensive Care Med. 2017, 43, 1764–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.B.P.; Meade, M.O.; Slutsky, A.S.; et al. Driving pressure and survival in the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 747–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lista, G.; Castoldi, F.; Fontana, P.; et al. Lung inflammation in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: effects of ventilation with different tidal volumes. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006, 41, 357–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichacker, P.Q.; Gerstenberger, E.P.; Banks, S.M.; et al. Meta-analysis of acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome trials testing low tidal volumes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002, 166, 1510–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, D.; Wells, D.; Bhandari, A.P. Positioning for acute respiratory distress in hospitalised infants and children. Cochrane Database of systematic reviews. 2012, 7, CD003645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotta, A.T.; Gunnarsson, B.; Fuhrman, B.P.; et al. Comparison of lung protective ventilation strategies in a rabbit model of acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2001, 29, 2176–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, C.R.; Barbas, C.S.; Medeiros, DM; et al. Temporal hemodynamic effects of permissive hypercapnia associated with ideal PEEP in ARDS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997, 156, 1458–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, J.J.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Gattinoni, L. Static and Dynamic Contributors to Ventilator-induced Lung Injury in Clinical Practice. Pressure, Energy, and Power. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020, 201(7), 767-774.

- Papazian, L.; Forel, J.M.; Gacouin, A.; et al. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363, 1107–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, A.T.N.; Patolia, S.; Guervilly, C. Neuromuscular blockade in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intensive Care. 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brochard, L.; Slutsky, A.; Pesenti, A. Mechanical Ventilation to Minimize Progression of Lung Injury in Acute Respiratory Failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017, 195(4), 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiumello, D.; Pristine, G.; Slutsky, A.S. Mechanical ventilation affects local and systemic cytokines in an animal model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999, 160(1), 109–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Recommendation | Rheological Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Driving pressure (DP) | < 15 cmH₂O | Maintains strain < 1 (elastic limit) |

| Tidal volume | Adjusted for DP < 15 cmH₂O Adjusted for Pplat = 28-32 cmH₂O |

Limits stress and strain |

| PEEP | PEEP titration to maximize homogeneity and recover pulmonary FRC | Reduces stress multipliers Reduces strain Reduces strain rate |

| Respiratory rate | Lowest possible allowing adequate ventilation | Limits mechanical power |

| Inspiratory flow | Moderate, avoiding high peaks | Reduces strain rate |

| Mechanical power | < 12 J/min | Below injury threshold |

| Inspiratory time | Prolonged (lower flow) | Reduces strain rate |

| Flow pattern | Constant and square | Optimizes stress distribution Decreases strain rate |

| Expiratory flow control | Consider if available | Reduces expiratory strain rate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).