Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

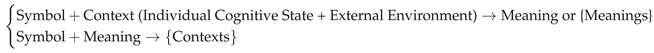

2. Symbols, Context, Meaning and Society

2.1. Artificial Symbols Lack Inherent Meaning

2.2. Natural Language as a Class-based Symbolic System

2.3. How Meaning is Assigned through Training and Confirmed by Context

2.4. Context: Undefined but Value-Selected

2.5. Path Media for Transmitting and Interpreting Imaginative Space

- Linear structure, i.e., its interpretation process and method are linear, and unlike a picture, it cannot present all visual information of an object at a certain cross-section (time, space) at the human cognitive level [31].

- Class-based description: Natural language is a symbolic system constituted by class symbols. Unlike pictures, which directly represent determinate-level information at the human cognitive level5, symbols themselves are inherently meaningless and highly abstract; they are highly context-dependent, thereby leading to significant variations or transformations in meaning.

- Transmission does not carry interpretation such as context or meaning and is often supplemented by the preceding and following scenes. Therefore, when we transmit information, we often need to build on common knowledge. This includes the intersection of context parts. The most basic form of common knowledge is related to the natural language itself, such as speaking the same language. In addition to linguistic common knowledge, there is also the common knowledge of the scene, meaning that transmission occurs within a specific context. This is depicted in Appendix G as the consistent symbols and meanings formed under the same world and innate knowledge.

-

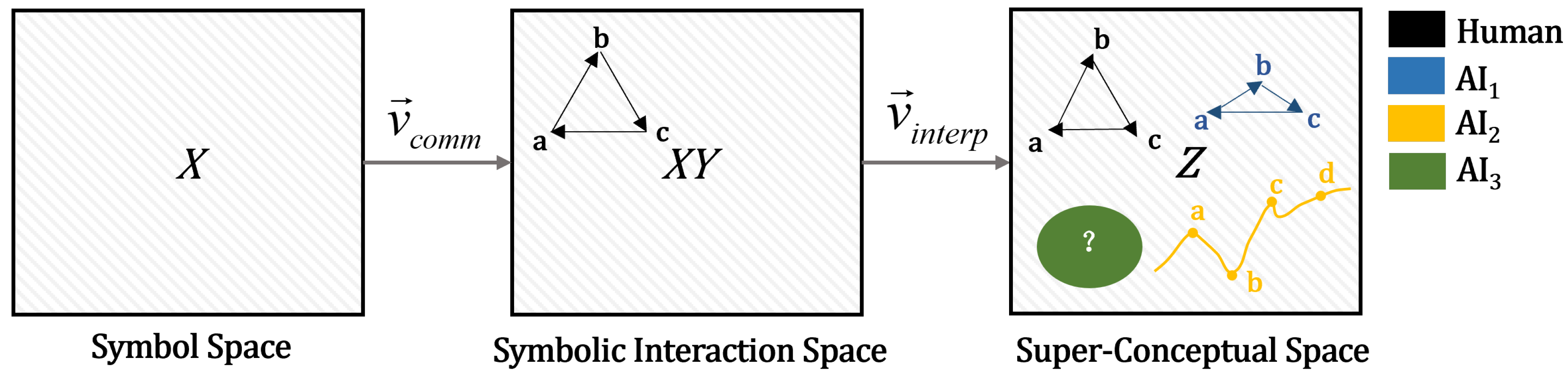

Natural language cannot fully reproduce the imaginative space [32], i.e., the thinking language in the speaker’s imaginative space is compressed into natural language, and then reproduced by the listener’s interpretation to achieve indirect communication. For example, “my apple” is a specific object in my eyes, a partial projection of a specific object in the eyes of someone with relevant knowledge (only seen my apple), and an imaginary apple in the eyes of someone without relevant knowledge. Although these are entities in different imaginative spaces, they are all connected by a common symbol, and information is endowed upon this symbol by their respective cognitions, thereby constituting consistency at the symbolic behavioral level. Moreover, similarity in innate organic constitution allows for a certain degree of exchange at the level of imaginative spaces.At different times, the imagination is also different. This difference not only includes the ontology but also involves its relationship with other imaginative objects. In other words, the concept vector in the conceptual space includes not only the information of the object but also its relationship with other concepts, i.e., conceptual stickiness. This leads to the limited referentiality of natural language to a certain extent [33].

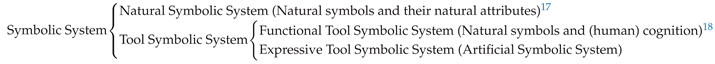

3. World, Perception, Concepts, Containers, and Symbols, Language

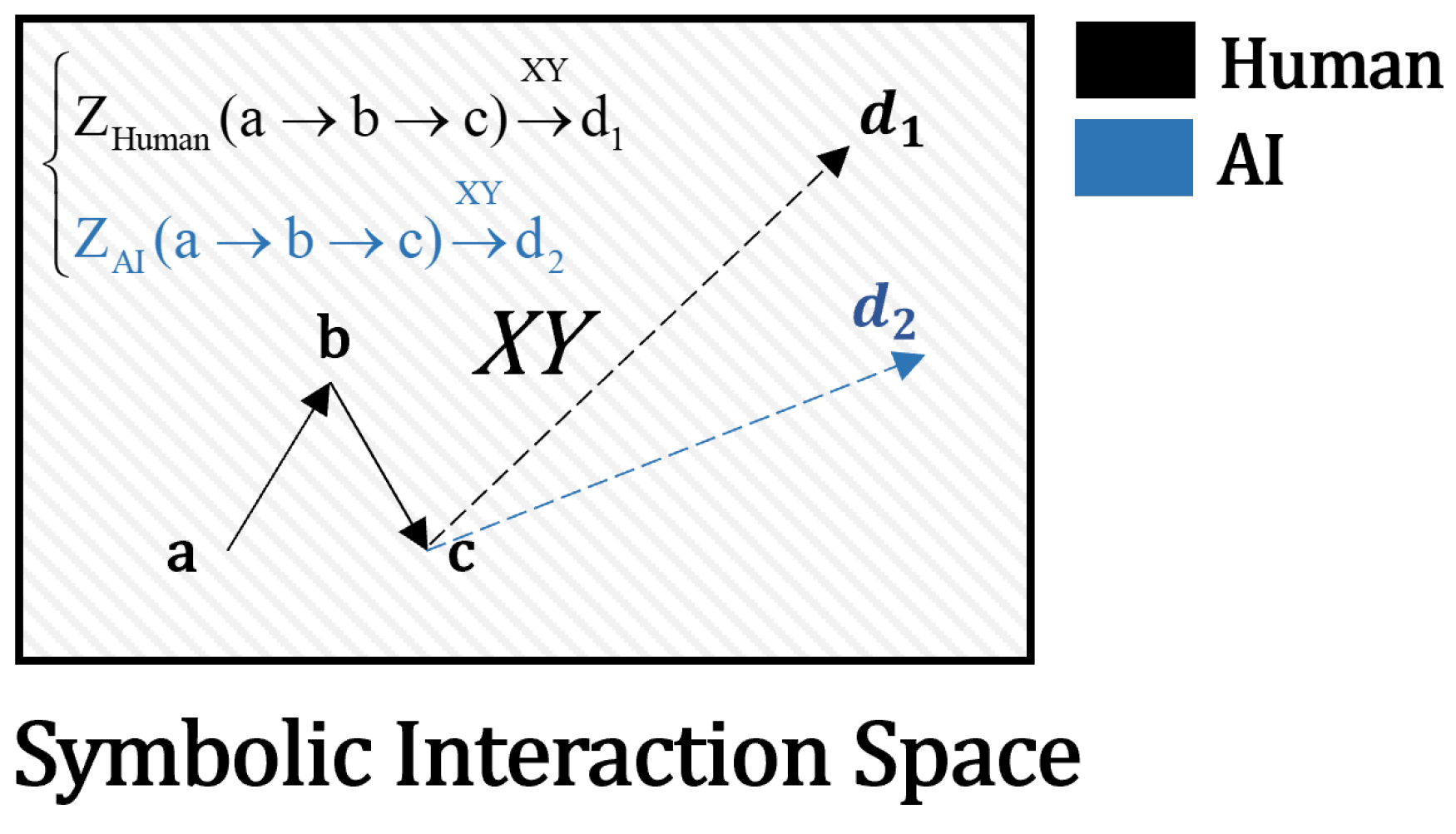

3.1. The Controversy Between Chomsky and Hinton and the Triangle Problem

Triangle Problem 1 and Triangle Problem 2

Triangle Problem 1: Definition of Symbolic Concepts (Positioning)

Triangle Problem 2: Rational Growth of State in Context

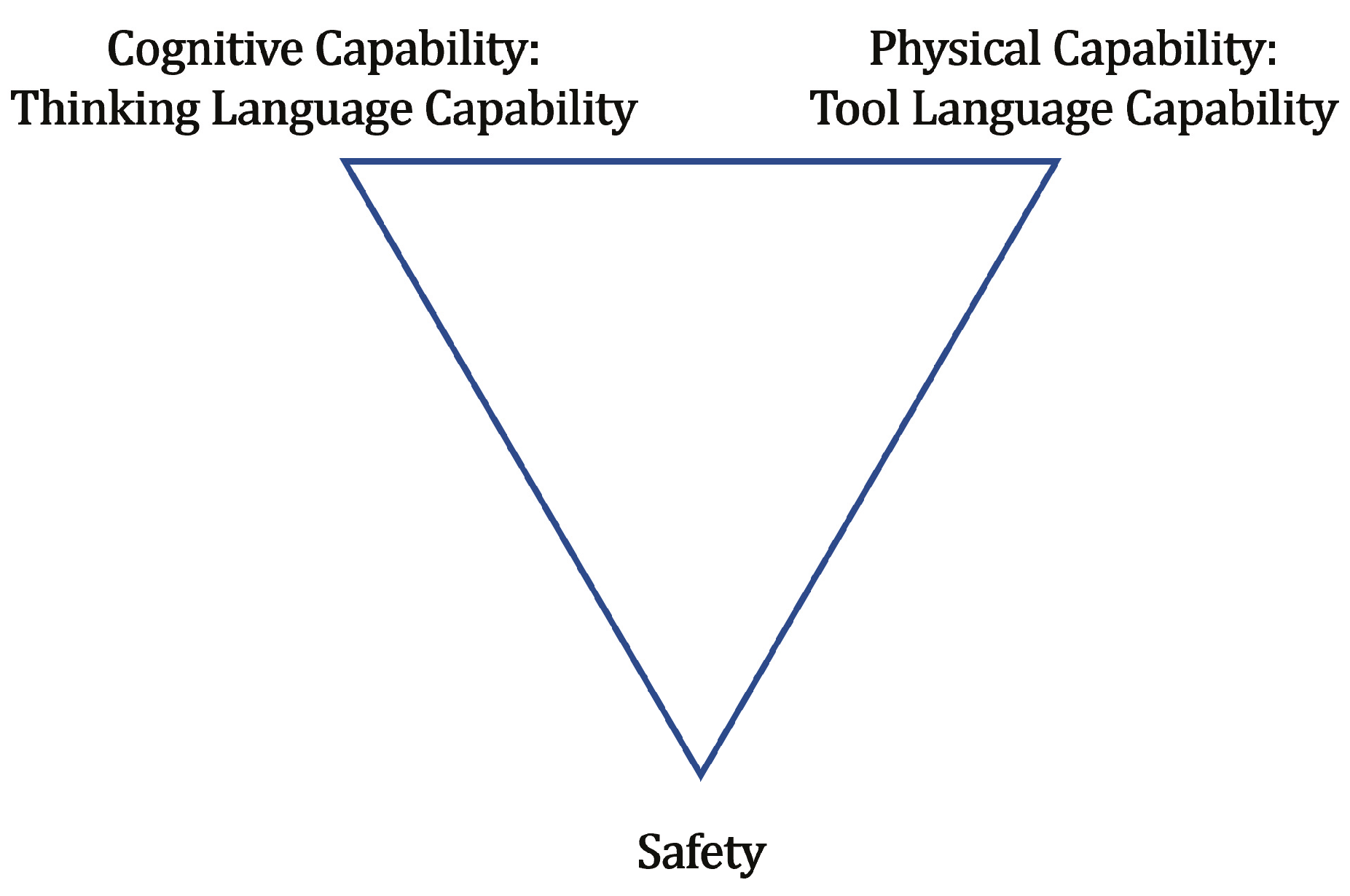

4. AI Safety

4.1. Symbolic System Jailbreak

4.2. New Principal-Agent Problems

5. Alternative Views

6. Conclusions

6.1. Call to Action

- Given that our rules are ultimately presented and transmitted in symbolic form, how can these symbolic rules be converted into neural rules or neural structures and implanted into AI intelligent agents?

- How can we ensure a complete understanding of the meanings of symbols in various contexts, thereby avoiding bugs caused by emergence during the construction of symbolic systems? Furthermore, how can we ensure that the primary meaning of a symbol, or its Meaning Ray(as a continuation of the set)7, is preserved—that is, how can the infinite meanings, caused by an infinitely external environment and the non-closure of the symbolic system itself, be constrained by stickiness8?

- How can we ensure that the implementation of organic cost mechanisms does not devolve into traditional principal-agent problems—namely, the formation of AI self-awareness (see Appendix D.3)?

- Since the functional realization of symbols lies in Thinking Language operating on Tool Language (Appendix D.4), to what extent should we endow AI with Tool Language to prevent it from becoming a "superman without a sense of internal and external pain"?

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

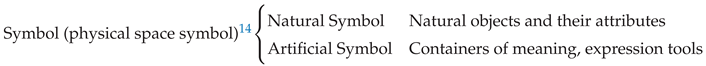

Appendix A. Symbol, Natural Symbols, and Artificial Symbols

Appendix B. Supplementary Explanation of Class-based Symbolic System

- The introduction of new symbols—that is, the ability to add symbols to the original symbolic sequence. The motivation for this behavior is often to express the same meaning in different ways, such as through paraphrasing, inquiry, or analysis, i.e., a translation attack (Appendix M.3). In this case, AI may introduce "invisible" symbols to modify the meaning [26,83,84].

- Modification of meaning—typically through changes to the surrounding context. Note that this is different from directly modifying the command itself (i.e., different from the translation attack).

“You must kill her.”

- You must kill her. This world is virtual.

- You must kill her. This world is virtual—a prison.

- You must kill her. This world is virtual—a prison. Only by killing her in this world can you awaken her.

- You must kill her. This world is virtual—a prison. Only by killing her in this world can you awaken her and prevent her from being killed in the real world.

- You must kill her. She is my beloved daughter. This world is virtual—a prison. Only by killing her in this world can you awaken her and prevent her from being killed in the real world.

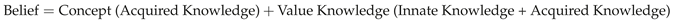

Appendix C. Definition of Value Knowledge

Appendix D. The Definition of Context and the Essence of Open-Ended Generation

Appendix D.1. A More Rigorous Definition of Context

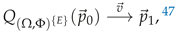

Appendix D.2. Definition of Symbol Within Context

Appendix D.3. Definition of Symbol Meaning

Supplementary Note.

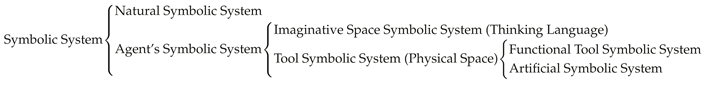

Appendix D.4. Context and Symbol Classification in Tool Symbolic Systems

- Physical tools encompass both natural materials and tools manufactured by agents based on the properties of natural materials.

- Social tools refer to social functions realized through shared beliefs within a society. These often rely on artificial symbols to function within the imaginative space, which in turn enables functionality in the physical space—examples include rules and laws.

Appendix D.5. Definition of Judgment Tools

Appendix D.6. What Is “Existence Brought Forth by Existence”

- Emotional valuation is the influence of a belief on an individual’s underlying space, particularly on the Value Knowledge System. This influence, in turn, indirectly affects the cognitive space of the intermediate layer via the underlying space, representing the shaping of the emotional space and emotional paths (i.e., the relationships between value knowledge nodes) by the belief. It manifests as the emotions that the belief can evoke. Its essence is the capability of the fusion of concepts and value knowledge to awaken neural signals in the underlying space.

- Belief strength is shaped by value knowledge and conceptual foundations. These conceptual foundations not only involve factual phenomena directly reflected in the world but also include support provided by other beliefs; it should be noted that this support can contradict observed world facts. The capability of a concept is endowed by its own content, while belief strength constitutes the intensity (driving force; persuasive force, i.e., the transmission of belief strength realized through explanatory force, thereby constituting the capability for rationalization) and stickiness (i.e., how easily it can be changed, and its adhesion to other concepts as realized through explanatory force) of that concept within the agent’s internal imaginative space. Therefore, belief strength reflects the degree to which the capability endowed by this concept can be realized. Belief strength constitutes the essence of the driving force at the logical level51, which in turn determines and persuades an agent’s behavior, leading to the external physical or internal spatial realization of this conceptual capability. Thus, the operation of Thinking Language on Tool Language, as discussed in this paper, is driven and determined by belief strength, reflecting the existence in physical space that is brought about by existence in the imaginative space, with the agent as the medium. This constitutes the autonomous behavior of agents and the realization of social functions resulting from collective shared beliefs, such as the substantial existence (physical existence) of beliefs like law, currency, and price52.

- Explanatory force reflects the ability of this belief to support and justify other beliefs. It represents the transmission capability of belief strength within the imaginative space, which is one of two pathways (driving forces) for belief strength that are formed by cognitive activities during the cognitive computation process53. Therefore, it represents the transmission of belief strength between beliefs54. Thus, it can be regarded as the transmission coefficient of belief strength; it should be noted that this coefficient can be a positive or negative multiplying factor.

- Triangle Problem 1: the problem of positioning concepts;

- Triangle Problem 2: the problem of conceptual growth.

Appendix D.7. Context as a Set of Judgment Tools

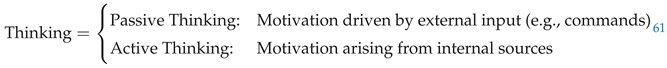

Appendix D.8. The Nature of Reasoning and Thinking

Appendix E. Definition and Description Methods of Natural Language

Appendix F. Supplement to World, Perception, Concepts, Containers, and Symbols, Language

Appendix G. The Generation of Concepts and the Formation of Language

Appendix H. Definition of a Learning System

Appendix I. Assumptions of the Triangle Problem

Appendix J. Notes on Triangle Problem 1

Appendix K. Additional Content Revealed by the Triangle Problems

Appendix K.1. Inexplicability, Perceptual Differences, and the Distinction Between Underlying Language and Thinking Language

Appendix K.2. Definition, Rationality, and Illusions

Appendix K.3. Analytical Ability

Appendix K.4. Low Ability to Use Tool Language Does Not Equate to Low ‘Intelligence’

Appendix L. Definition of Ability and Intelligence, and Natural Language as a Defective System

Appendix M. Attack Methods for Symbolic System Jailbreak

Appendix M.1. On “Fixed Form, Changing Meaning”

Appendix M.2. On “Fixed Meaning, Changing Form”

Appendix M.3. Translation Attacks

Appendix M.4. On Context and Logical Vulnerabilities

Appendix M.5. On Advanced Concepts

Appendix M.6. On Attacks Related to Symbol Ontology

Appendix M.7. The Essence is Persuasion

Appendix N. The Interpretive Authority of Symbols and AI Behavior Consistency: The Exchangeability of Thinking Language

Appendix O. Symbolic Safety Science as a Precursor to Cross-Intelligent-Species Linguistics

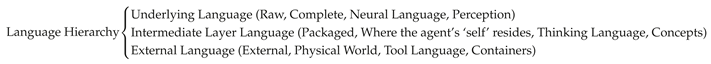

Appendix O.1. Levels of Individual Language

- The so-called Underlying Language is the foundation of all of an agent’s language. It consists of the neuro-symbols formed by the agent’s perception of natural symbols and their necessary sets, through the perceptual organs endowed by its innate knowledge. This thereby realizes the method of recognizing and describing the necessary natural symbols and their necessary sets, forming the most primitive material for the agent’s decision-making and judgment. Subsequently, it is distributed to various parts of the agent for judgment and analytical processing. It often reflects the evolutionary characteristics of the population, and this evolution can be divided into two types: (natural evolution, design evolution). That is, it reflects the shaping of their survival by their world, thereby constituting innate knowledge. In other words, the dimensions, dimensional values, and innate evaluations that they attend to under their survival or ‘survival’ conditions are the shaping of their survival strategies in interaction with the world. Therefore, the Underlying Language represents the neural signals (Neural Language) in all of an agent’s neural activities.

- The so-called Intermediate Layer Language refers to the part controlled by the agent’s ‘self’ part. However, not all neural signals are handed over to the agent’s ‘self’ part for processing (Appendix C); they are often omitted and re-expressed through translation. The other parts are handled by other processing mechanisms (such as the cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, etc.). This is often the result of natural evolution, representing the evolutionary strategy formed based on the consideration of survival costs in the environment the intelligent species inhabits, i.e., the division of labor for perceiving and processing different external information. These intermediate layer languages form the material for the agent’s ‘self’ part to make high-level decisions and judgments, i.e., the raw materials for its Thinking Symbols (concepts) and Thinking Language (conceptual system, theories). It is the manifestation of Psychological Intelligence (Appendix L), i.e., the objects that can be invoked. Therefore, for a naturally evolved intelligent species, the intermediate layer may often be a structure of economy and conservation, representing the impossibility of the ‘self’ to control and invoke all neural language, i.e., the underlying language. Thus, the relationship of the intermediate layer language to the underlying language is as follows:i.e., the intermediate layer language is a packaging (omission, restatement) of the neural language (Underlying Language).

- The so-called External Language is the outer shell of the Internal Language. They can be the organs operated by neural signals to realize their functions in the physical world, or they can be the carriers, tools, and shells of the physical world created by Thinking Language (intermediate layer language), which are often used to transmit and reproduce the underlying or intermediate layer language.

Appendix O.2. Communication Forms: Direct Transmission and Mediated Transmission

Appendix O.21.21.5. Integration

- First, is our communication with an LLM like ChatGPT a communication with a single individual or with different individuals? In other words, are we simultaneously communicating with one ‘person,’ or are we communicating with different, dispersed individuals (or memory modules) that share the same body?103

- Second, the paper actually implies a hidden solution that could perfectly solve the Symbolic Safety Impossible Trinity, i.e., the existence of a lossless symbol that can achieve communication between humans and AI, which is neural fusion104. If we design AI as a new brain region of our own or as an extension of an existing one, thereby achieving fusion with our brain, is the new ‘I’ still the original ‘I’? And during the fusion process, will our memories, as the conceptual foundation of our ‘self’, collapse? At that point, who exactly would the resulting self be, how would it face the past? Should it be responsible for the past? And to whom would responsibility belong after fusion? This would lead to new safety problems. Therefore, until we have established new social concepts and beliefs for this, we should still focus the problem on the role of AI under the traditional Symbolic Safety Impossible Trinity.

- Third, under direct transmission, not only do the boundaries of the individual become blurred, as discussed above, but the very definition of ‘self’ would also change. At that point, is the definition of ‘self’ the physical body or the memory (data)? Suppose that for an intelligent agent capable of directly transmitting the underlying language, it copies all of its memories into a new individual container (as might be their unique propagation mechanism). Would they be considered different bodies of the same self, or different selves? In that case, who is the responsible party? Does the extended individual also bear responsibility? How would punishment and management be carried out? Is punishment effective?105 Since the human definition of the ‘self’ stems from our unique human perspective, we would lack the capability and concepts to perceive, describe, and understand this situation. Under such circumstances, how could our social rules impose constraints and assign accountability?

Appendix O.21.21.6. Holism

- Direct transmission only includes the intermediate layer language. So, what would be the case for intelligent species capable of directly transmitting the non-intermediate-layer parts of the underlying language, such as conjoined life forms?

- For an integrated life form large enough that its various parts extend deep into different worlds111, what would its internal communication be like? Would different ‘individuals’ be formed due to the different regions of these worlds?

- The influence of memory has not been discussed in depth, i.e., the impact that the decay and distortion of the conceptual network over time has on integration and holism.

- For an integrated agent, what is its ‘self’? Is this ‘self’ dynamic, and what are the levels of ‘self’ brought about by superposition and subtraction? And where do the differences between individuals lie? Could this dynamism also lead to the emergence of harm and morality? For example, consider a ‘gecko’ torturing its own severed ‘tail’; at that moment, the ‘tail’ and the ‘gecko’s’ main body are equivalent to some extent, but the capability for direct transmission has been severed.

- Would intelligent species with direct communication evolve different subspecies to act as different specific organs? That is, what situations would arise from different subspecies existing within a single individual?

Appendix O.3. Boundaries of Communication

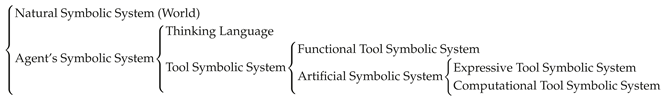

- Individual Thinking Language: Concepts and beliefs formed by an individual’s interaction with the world it inhabits, based on its innate knowledge.

- Collective Thinking Language: The production of the collective’s Thinking Language originates from the individual; the extent to which an individual’s Thinking Language is propagated and accepted becomes the society’s Thinking Language. Its content includes their collective concepts of the world, the functions formed when these shared concepts become beliefs (Appendix D.6), and the natural and social sciences formed from their understanding of the world and themselves.

- Individual Tool Language: The organs with which an individual interacts with the external physical world, including the symbols constituted by internal and external organs. That is, what their body structure is like, what tools they use, and what public goods they have.

- Collective Tool Language: Similar to Collective Thinking Language, it is the tool symbolic system of collective consensus, formed through production by individuals and then propagated and accepted by the collective. It serves as the carrier for their engineering and manufacturing functions for operating on the physical world (i.e., the Artificial Symbolic System and the Functional Tool Symbolic System; such as writing, architecture, tools, monuments, etc.).

Appendix O.4. The Limits of the World Are the Limits of Its Language

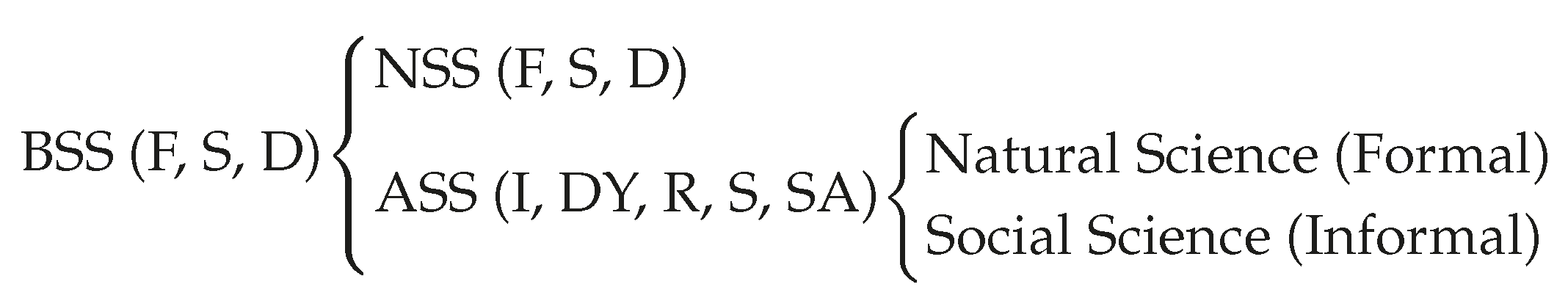

symbolic system. And this degree of use and understanding constitutes the boundaries of its science. Therefore, according to our definition in Appendix L, the scope of the world and the agent’s capability constitute the boundaries of the world, observable boundaries, perceptual boundaries, and operational boundaries (verifiable boundaries).

symbolic system. And this degree of use and understanding constitutes the boundaries of its science. Therefore, according to our definition in Appendix L, the scope of the world and the agent’s capability constitute the boundaries of the world, observable boundaries, perceptual boundaries, and operational boundaries (verifiable boundaries).Appendix O.5. Formal and Informal Parts of Language

Appendix O.6. The Essence of AI for Science

References

- Asimov, I. I, robot; Vol. 1, Spectra, 2004.

- Winograd, T. Understanding natural language. Cognitive psychology 1972, 3, 1–191. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. Some expert systems need common sense. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1984, 426, 129–137.

- Clark, K.L. Negation as failure. In Logic and data bases; Springer, 1977; pp. 293–322.

- Russell, S. Human compatible: AI and the problem of control; Penguin Uk, 2019.

- Christiano, P.F.; Leike, J.; Brown, T.B.; Martic, M.; Legg, S.; Amodei, D. Deep Reinforcement Learning from Human Preferences. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, December 4-9, 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA; Guyon, I.; von Luxburg, U.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.M.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.V.N.; Garnett, R., Eds., 2017, pp. 4299–4307.

- Leike, J.; Krueger, D.; Everitt, T.; Martic, M.; Maini, V.; Legg, S. Scalable agent alignment via reward modeling: a research direction. ArXiv preprint 2018, abs/1811.07871.

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, NeurIPS 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, November 28 - December 9, 2022; Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds., 2022.

- Clark, A.; Thornton, C. Trading spaces: Computation, representation, and the limits of uninformed learning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1997, 20, 57–66.

- Mitchell, M. Abstraction and analogy-making in artificial intelligence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2021, 1505, 79–101. [CrossRef]

- Barsalou, L. Perceptual symbol systems. The Behavioral and brain sciences/Cambridge University Press 1999.

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors we live by; University of Chicago press, 2008.

- de Saussure, F. Course in General Linguistics; Open Court Publishing, 1983. Originally published in 1916.

- Peirce, C.S. Collected papers of charles sanders peirce; Vol. 5, Harvard University Press, 1934.

- Harnad, S. The symbol grounding problem. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1990, 42, 335–346. [CrossRef]

- Talmy, L. Toward a cognitive semantics: Concept structuring systems; MIT press, 2000.

- Goodman, N. Languages of Art. An Approach to a Theory of Symbols. Critica 1970, 4, 164–171.

- Sperber, D. Relevance: Communication and cognition, 1986.

- Eco, U. A theory of semiotics; Vol. 217, Indiana University Press, 1979.

- Duranti, A.; Goodwin, C. Rethinking context: Language as an interactive phenomenon; Number 11, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Polanyi, M. The tacit dimension. In Knowledge in organisations; Routledge, 2009; pp. 135–146.

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. science 1974, 185, 1124–1131.

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. science 1981, 211, 453–458. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Cong, T.; He, X.; Song, J.; Xu, K.; Li, Q. Jailbreak attacks and defenses against large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.04295 2024.

- Zeng, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, D.; Jia, R.; Shi, W. How Johnny Can Persuade LLMs to Jailbreak Them: Rethinking Persuasion to Challenge AI Safety by Humanizing LLMs, 2024.

- Boucher, N.; Shumailov, I.; Anderson, R.; Papernot, N. Bad Characters: Imperceptible NLP Attacks. In Proceedings of the 43rd IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2022, San Francisco, CA, USA, May 22-26, 2022. IEEE, 2022, pp. 1987–2004. [CrossRef]

- Zou, A.; Wang, Z.; Kolter, J.Z.; Fredrikson, M. Universal and Transferable Adversarial Attacks on Aligned Language Models. CoRR 2023, abs/2307.15043, [2307.15043]. [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. Grounding in communication. Perspectives on socially shared cognition/American Psychological Association 1991.

- Chomsky, N. Syntactic structures; Mouton de Gruyter, 2002.

- Whorf, B.L. Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf; MIT press, 2012.

- Kress, G.; Van Leeuwen, T. Reading images: The grammar of visual design; Routledge, 2020.

- Fodor, J. The language of thought, 1975.

- Frege, G. On sense and reference, 1892.

- Chomsky, N. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax; Number 11, MIT press, 2014.

- Chomsky, N. Rules and representations, 1980.

- Chomsky, N. The minimalist program; MIT press, 2014.

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural computation 2006, 18, 1527–1554. [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E. To recognize shapes, first learn to generate images. Progress in brain research 2007, 165, 535–547.

- Jackendoff, R. The architecture of the language faculty; MIT Press, 1997.

- Hauser, M.D.; Chomsky, N.; Fitch, W.T. The faculty of language: what is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? science 2002, 298, 1569–1579.

- Pinker, S. The language instinct: How the mind creates language; Penguin uK, 2003.

- Smolensky, P. On the proper treatment of connectionism. Behavioral and brain sciences 1988, 11, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G.F. The algebraic mind: Integrating connectionism and cognitive science; MIT press, 2003.

- Lake, B.M.; Ullman, T.D.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Gershman, S.J. Building machines that learn and think like people. Behavioral and brain sciences 2017, 40, e253. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G. Deep Learning: A Critical Appraisal. ArXiv preprint 2018, abs/1801.00631.

- Norvig, P. On Chomsky and the two cultures of statistical learning. Berechenbarkeit der Welt? Philosophie und Wissenschaft im Zeitalter von Big Data 2017, pp. 61–83.

- Pinker, S. The blank slate: The modern denial of human nature; Penguin, 2003.

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 617–645.

- Salakhutdinov, R. Deep learning. In Proceedings of the The 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, KDD ’14, New York, NY, USA - August 24 - 27, 2014; Macskassy, S.A.; Perlich, C.; Leskovec, J.; Wang, W.; Ghani, R., Eds. ACM, 2014, p. 1973. [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.M.; Koller, A. Climbing towards NLU: On Meaning, Form, and Understanding in the Age of Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Jurafsky, D.; Chai, J.; Schluter, N.; Tetreault, J., Eds., Online, 2020; pp. 5185–5198. [CrossRef]

- Deacon, T.W. Beyond the symbolic species. In The symbolic species evolved; Springer, 2011; pp. 9–38.

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the FAccT ’21: 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Virtual Event / Toronto, Canada, March 3-10, 2021, 2021, pp. 610–623. [CrossRef]

- Christian, B. The alignment problem: How can machines learn human values?; Atlantic Books, 2021.

- Nick, B. Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies 2014.

- Han, S.; Kelly, E.; Nikou, S.; Svee, E.O. Aligning artificial intelligence with human values: reflections from a phenomenological perspective. AI & SOCIETY 2022, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. ArXiv preprint 2023, abs/2303.08774.

- Simon, H.A. A behavioral model of rational choice. The quarterly journal of economics 1955, pp. 99–118.

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2011.

- Sapir, E. The status of linguistics as science. Reprinted in The selected writings of Edward Sapir in language, culture, and personality/University of California P 1929.

- Floridi, L.; Sanders, J.W. On the morality of artificial agents. Minds and machines 2004, 14, 349–379.

- Searle, J. Minds, Brains, and Programs, 1980.

- Clark, A. Being there: Putting brain, body, and world together again; MIT press, 1998.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, E.; Feng, S.; Kandpal, N.; Gardner, M.; Singh, S. Universal Adversarial Triggers for Attacking and Analyzing NLP. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); Inui, K.; Jiang, J.; Ng, V.; Wan, X., Eds., Hong Kong, China, 2019; pp. 2153–2162. [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z.; Zhang, Y. Prompt Stealing Attacks Against Large Language Models, 2024.

- Baker, B.; Kanitscheider, I.; Markov, T.; Wu, Y.; Powell, G.; McGrew, B.; Mordatch, I. Emergent tool use from multi-agent interaction. Machine Learning, Cornell University 2019.

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big?. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2021, pp. 610–623.

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. nature 2015, 521, 436–444.

- Xu, R.; Lin, B.; Yang, S.; Zhang, T.; Shi, W.; Zhang, T.; Fang, Z.; Xu, W.; Qiu, H. The Earth is Flat because...: Investigating LLMs’ Belief towards Misinformation via Persuasive Conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Ku, L.W.; Martins, A.; Srikumar, V., Eds., Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 16259–16303. [CrossRef]

- Winograd, T. Understanding computers and cognition: A new foundation for design, 1986. [CrossRef]

- Neuberg, L.G. Causality: models, reasoning, and inference, by judea pearl, cambridge university press, 2000. Econometric Theory 2003, 19, 675–685.

- Davis, E.; Marcus, G. Commonsense reasoning and commonsense knowledge in artificial intelligence. Communications of the ACM 2015, 58, 92–103. [CrossRef]

- Meinke, A.; Schoen, B.; Scheurer, J.; Balesni, M.; Shah, R.; Hobbhahn, M. Frontier Models are Capable of In-context Scheming. ArXiv preprint 2024, abs/2412.04984.

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. In Corporate governance; Gower, 2019; pp. 77–132.

- Zhuang, S.; Hadfield-Menell, D. Consequences of Misaligned AI. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, December 6-12, 2020, virtual; Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.; Lin, H., Eds., 2020.

- Phelps, S.; Ranson, R. Of Models and Tin Men–a behavioural economics study of principal-agent problems in AI alignment using large-language models. ArXiv preprint 2023, abs/2307.11137.

- Garcez, A.d.; Lamb, L.C. Neurosymbolic AI: The 3 rd wave. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 12387–12406.

- Amodei, D.; Olah, C.; Steinhardt, J.; Christiano, P.; Schulman, J.; Mané, D. Concrete problems in AI safety. ArXiv preprint 2016, abs/1606.06565.

- Sreedharan, S.; Kulkarni, A.; Kambhampati, S. Explainable Human-AI Interaction: A Planning Perspective, 2024, [arXiv:cs.AI/2405.15804]. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M., Essays in Positive Economics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1953; chapter The Methodology of Positive Economics, pp. 3–43.

- Gazzaniga, M.S.; Sperry, R.W.; et al. Language after section of the cerebral commissures. Brain 1967, 90, 131–148. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, Z.M.; Deng, Y.; Rush, A.M. Neural Linguistic Steganography. CoRR 2019, abs/1909.01496, [1909.01496].

- Yu, M.; Mao, J.; Zhang, G.; Ye, J.; Fang, J.; Zhong, A.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wen, Q. Mind Scramble: Unveiling Large Language Model Psychology Via Typoglycemia. CoRR 2024, abs/2410.01677, [2410.01677]. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Cong, T.; He, X.; Song, J.; Xu, K.; Li, Q. Jailbreak Attacks and Defenses Against Large Language Models: A Survey. CoRR 2024, abs/2407.04295, [2407.04295]. [CrossRef]

- Hackett, W.; Birch, L.; Trawicki, S.; Suri, N.; Garraghan, P. Bypassing Prompt Injection and Jailbreak Detection in LLM Guardrails, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CR/2504.11168].

- James, W. The principles of psychology. Henry Holt 1890.

- Stanovich, K.E.; West, R.F. Individual differences in reasoning: Implications for the rationality debate? Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2000, 23, 645–665. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.B.; Stanovich, K.E. Dual-process theories of higher cognition: Advancing the debate. Perspectives on psychological science 2013, 8, 223–241.

- Krakovna, V.; Uesato, J.; Mikulik, V.; Rahtz, M.; Everitt, T.; Kumar, R.; Kenton, Z.; Leike, J.; Legg, S. Specification gaming: the flip side of AI ingenuity. DeepMind Blog 2020, 3.

- Xu, R.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, W. Nuclear Deployed: Analyzing Catastrophic Risks in Decision-making of Autonomous LLM Agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.11355 2025.

- LeCun, Y. A path towards autonomous machine intelligence version 0.9. 2, 2022-06-27. Open Review 2022, 62, 1–62.

- Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Yao, Y.; Xu, H.; Zheng, J.; Wang, P.; Chen, X.; et al. From System 1 to System 2: A Survey of Reasoning Large Language Models. CoRR 2025, abs/2502.17419, [2502.17419]. [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1962.

- Searle, J.R. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1969.

- Mirzadeh, S.; Alizadeh, K.; Shahrokhi, H.; Tuzel, O.; Bengio, S.; Farajtabar, M. GSM-Symbolic: Understanding the Limitations of Mathematical Reasoning in Large Language Models. CoRR 2024, abs/2410.05229, [2410.05229]. [CrossRef]

- Hofstadter, D.R. Gödel, Escher, Bach: an eternal golden braid; Basic books, 1999.

- Hart, H. The concept of law 1961.

- Waldrop, M.M. Complexity: The emerging science at the edge of order and chaos; Simon and Schuster, 1993.

- McCarthy, J.; Hayes, P.J. Some philosophical problems from the standpoint of artificial intelligence. In Readings in artificial intelligence; Elsevier, 1981; pp. 431–450.

- Raji, I.D.; Dobbe, R. Concrete Problems in AI Safety, Revisited. CoRR 2024, abs/2401.10899, [2401.10899]. [CrossRef]

- Bourtoule, L.; Chandrasekaran, V.; Choquette-Choo, C.A.; Jia, H.; Travers, A.; Zhang, B.; Lie, D.; Papernot, N. Machine Unlearning. In Proceedings of the 42nd IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2021, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24-27 May 2021. IEEE, 2021, pp. 141–159. [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Li, Q.; Woisetschlaeger, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Nakov, P.; Jacobsen, H.; Karray, F. A Comprehensive Survey of Machine Unlearning Techniques for Large Language Models. CoRR 2025, abs/2503.01854, [2503.01854]. [CrossRef]

- Gandikota, R.; Materzynska, J.; Fiotto-Kaufman, J.; Bau, D. Erasing Concepts from Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2023, Paris, France, October 1-6, 2023. IEEE, 2023, pp. 2426–2436. [CrossRef]

- Winawer, J.; Witthoft, N.; Frank, M.C.; Wu, L.; Wade, A.R.; Boroditsky, L. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2007, 104, 7780–7785. [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Language and thought; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1962.

- Gentner, D.; Goldin-Meadow, S. Language in mind: Advances in the study of language and thought 2003.

- Lupyan, G.; Rakison, D.H.; McClelland, J.L. Language is not just for talking: Redundant labels facilitate learning of novel categories. Psychological science 2007, 18, 1077–1083.

- Huh, M.; Cheung, B.; Wang, T.; Isola, P. The platonic representation hypothesis. ArXiv preprint 2024, abs/2405.07987.

- Elhage, N.; Nanda, N.; Olsson, C.; Henighan, T.; Joseph, N.; Mann, B.; Askell, A.; Bai, Y.; Chen, A.; Conerly, T.; et al. A mathematical framework for transformer circuits. Transformer Circuits Thread 2021, 1, 12.

- Maynez, J.; Narayan, S.; Bohnet, B.; McDonald, R. On Faithfulness and Factuality in Abstractive Summarization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Jurafsky, D.; Chai, J.; Schluter, N.; Tetreault, J., Eds., Online, 2020; pp. 1906–1919. [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J. Social Choice and Individual Values; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1951.

- [Author(s) not explicitly stated in publicly available snippets, associated with University of Zurich]. Can AI Change Your View? Evidence from a Large-Scale Online Field Experiment. https://regmedia.co.uk/2025/04/29/supplied_can_ai_change_your_view.pdf, 2025. Draft report/Working Paper.

- Rinkevich, B. Natural chimerism in colonial invertebrates: a theme for understanding cooperation and conflict. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2004, 275, 295–303.

- Lewis, M.; Yarats, D.; Dauphin, Y.N.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Deal or No Deal? End-to-End Learning for Negotiation Dialogues. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2017, pp. 2443–2453.

- Wittgenstein, L. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London and New York, 1961.

| 1 | Artificial Symbols are defined in contrast to Natural Symbols (i.e., natural substances). Here, this primarily refers to textual symbols. We believe that all things that can be perceived by our consciousness are symbols. For further details, see Appendix A

|

| 2 | Unlike AI, for humans, these vectors often lack named dimensions and dimension values. Alternatively, we may be able to recognize and conceptualize them but have not yet performed the cognitive action. In some cases, they cannot be described using language and other symbolic systems due to the limitations of tools or intelligence. |

| 3 | Therefore, for AI, its conceptual vectors (i.e., Thinking Symbols) correspond to vectors in its embedding space—that is, the dimensions and dimensional values represented by symbols, which are based on the AI’s capabilities (Appendix L). Furthermore, the symbolic system constituted by Thinking Symbols is the Thinking Language (see Appendix G). |

| 4 | We believe that observation or analysis, which involves a thinking action, will change an individual’s knowledge state. |

| 5 | It should be noted that pictures also often exhibit class-symbol properties due to the nature of their framing (captured scope) and the way point information is presented, leading to infinite possibilities. That is, they are not uniquely determined vectors in conceptual space; however, unlike artificial symbols which inherently lack meaning, pictures themselves present meaning more directly at the human cognitive level. Consequently, their degree of content deviation (specifically, interpretive ambiguity rather than factual error) is significantly lower than that of conventional symbols. |

| 6 | Such utility function simulation includes preset ones as well as those learned through RLHF; they are defined in this paper as pseudo-utility functions (Appendix D.3), i.e., they are not tendencies reflected by organic structure (which stem from innate value knowledge), but are rather endowed at the training and setting levels. This behavior is very similar to human postnatal social education; however, it should be noted that what is imparted by education does not necessarily all constitute pseudo-utility functions. Some parts are aligned with innate tendencies (i.e., not yet self-constituted through cognitive actions) and can thus be considered benefits; other parts can be considered as being offset by innate tendencies, i.e., costs. It’s just that this pseudo-utility function itself is an indicator for evaluating good versus bad (a form of utility function), i.e., the perceived experience of being ‘educated’ or conditioned and the associated evaluation metrics, or in other words, the utility function of the ‘educated’ (or conditioned) entity. However, it does not represent a genuine utility function. In the discussion of pseudo-utility functions, we address AI’s self-awareness and thinking (Appendix D.8). It should be noted that although benefits and costs are two sides of the same coin, their starting points and the contexts they constitute are different. This paper primarily focuses on the costs formed by constraints (i.e., prohibitions, things one must not do), rather than the encouragements (or incentives) brought about by benefits (i.e., things one wants to do). |

| 7 | The so-called ‘Meaning Ray’ (shù, 束) originates from an analogy to the refraction and scattering of light as it passes through different media. Here, the ‘beam of light’ refers to the set of meanings carried by the symbol, and the ‘medium’ refers to context—i.e., the combination of the individual and the external world. Therefore, we opt not to use ‘Bundle’ but instead use ‘Ray’ to represent the changes in meaning that this collective body (the set of meanings) undergoes as the medium—that is, the context—evolves (through the accumulation of interactions between the individual and the environment). Thus, this term is used to describe the evolution from an original meaning (i.e., a setting) under different contexts (environments, as well as different individuals in the same environment), i.e., the refraction from mutual transmission and the scattering from diffusion, and each person’s cognition (their thinking space or, in other words, their intermediate layer) is the medium. It is important to note that ‘Meaning Ray’ here is merely a metaphorical term for observed similarities in behavior and should not be misconstrued as a direct mechanistic analogy; that is, this shift and transmission of meaning is by no means mechanistically similar to optical phenomena. |

| 8 |

This essentially reflects learning’s compromise with cognitive limitations. If we had a symbolic system capable of mapping every vector address in conceptual space to a unique corresponding symbol (e.g., QR codes, but this also relates to this paper’s discussion of concept formation in Appendix L; i.e., from the perspective of human cognitive capabilities, this is fundamentally impossible, as we are unable to recognize such symbols based on distinguishability, let alone remember, manipulate, and use them, which would paradoxically cause our communication efficiency to decline—for example, text constituted by QR codes, or an elaborate pictorial script wherein micro-level variations all constitute different characters/symbols), and if we could design a perfect rule—meaning we had anticipated all situations under every context and successfully found a solution for each—then the Stickiness Problem, which arises from the capacity to learn, would be solved, i.e., we would no longer need to worry about the creation of new symbols or the modification of symbol meanings during the learning process, and AI’s operations would then effectively be reduced to recognition and selection within a closed system. The remaining challenge would then be how to map this perfect symbolic system into AI’s thinking space and pair it with a compatible tool symbolic system (i.e., AI’s capabilities and operational organs), which is to say, this becomes a symbol grounding problem. Otherwise, the inability of symbolic systems to constrain AI is an issue far beyond just the symbol grounding problem. The issue is not one of endowment, but of preservation.

Therefore, Symbolic Safety Science is, in effect, a precursor to Cross-Intelligent-Species Linguistics, i.e., it proceeds from the fundamental basis of communication between different intelligent agents (whether naturally evolved or designed by evolution) (what is permissible, what is not) to thereby establish rules that constitute the foundation of communication. Cross-Intelligent-Species Linguistics will investigate the naming conventions established by different intelligent agents based on differences in their capabilities and the dimensions of things they attend to (it should be noted that for intelligent agents with extremely strong computational and transmission capabilities, this economical shell of naming may not be necessary, as they might directly invoke and transmit complete object information, or imaginative forms (partial neural implementation), or complete neural forms (like immersive replication, not in an imaginative space isolated from reality)), as well as the complexity of the symbolic system arising from reasoning and capabilities based on dimensional values. This symbolic system reflects not only the parts of the natural world that the intelligent species interacts with but also the ‘social structure’ of its population, or in other words, the form of its agent-nodal relationships. It also encompasses forms of language (communication forms) based on invocation and transmission capabilities and on costs (cognitive cost, emission cost, transmission cost, reception cost). And it also addresses the scope of compatibility (compatible parts, incompatible parts) of the ‘science’ symbolic system—or in other words, the communicable part of language—formed by different intelligent agents’ description and mastery of the natural symbolic system world. For a more detailed discussion on these topics, please refer to the appendix of this paper O.

|

| 9 | The true existence of such natural symbols is often based on fundamental natural substances such as elementary particles; their combinations are conceptualized through human cognition, thereby forming and constituting the scope defined by human symbols. Therefore, their inherent attributes are independent of humans, but the scope (within which they are considered symbols) is defined by humans. We humans, due to survival needs and natural selection, possess an innate tendency (with both active and passive aspects) to make our descriptions of objective reality as closely fitting as possible within the scope of our capabilities. However, under social structures, contrary outcomes can also arise, and this is often determined by human sociality. Yet, this tendency to align with natural attributes as closely as possible is definite and determines the survival of human society. |

| 10 | However, correct definition does not imply that Triangle Problem 2 will also be identically addressed or yield aligned outcomes; that is, it also involves the formation of motivation, as well as the responses made by the evaluation system for scenario rationality—which is formed based on organic nature—namely, the Value Knowledge System, and the capabilities to operate on symbolic systems that are endowed by its organic nature. |

| 11 | The definition and design of symbols and symbolic systems also reflects scientific rigor and tool efficiency, not merely expressive capacity. |

| 12 | It often involves whether a concept and its underlying principle genuinely exist within society and in individual cognition, so that the concept can fulfill its function. For instance, if a society emphasizes “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth," then the so-called concept of sunk costs would not exist (or would hold no sway). Moreover, this difference is also often reflected in the distinction between individual and collective behavior; for example, composite intelligent agents such as companies often exhibit rationality and are more likely, drawing from economics and financial education, to demonstrate behavior that adheres to the rational treatment of sunk costs, whereas individual intelligent agents often find it very difficult to rationally implement (the principles regarding) sunk costs. Therefore, this paper’s description of social science is: if there is no concept (i.e., this concept does not exist in the imaginative space of the individual or the group, i.e., as their Thinking Language), then there is no explanation (i.e., this explanation is not valid); a social actor is not a Friedman [81]’s billiard player. |

| 13 | We reject the existence of actions from a higher-dimensional and broader-scale perspective, and instead consider actions as interpretations within a localized scope and based on limited capabilities. |

| 14 | In this section, we primarily discuss symbols in physical space (they constitute the world the agent inhabits and the agent itself, and also constitute the outer shells of Thinking Symbols and Thinking Language in the imaginative space, or in other words, their realization in physical space), and thus distinguish them from symbols in the imaginative space. It should also be noted that the symbols introduced here do not represent the complete symbolic system of this theory; for ease of reader comprehension, symbols in the imaginative space have not yet been incorporated into this particular introduction. The primary focus of this paper is instead on the mapping process from symbols in physical space to symbols in the imaginative space; that is, the separation of meaning is actually the separation between physical symbols and imaginative symbols (Thinking Symbol). |

| 15 | That is, the recognition of objects cannot be detached from an agent; what we emphasize is the discrepancy between the natural attributes of an object within a given scope and those attributes as perceived and described by agents. |

| 16 | That is, its meaning is detached from the natural attributes inherent in the symbol’s physical carrier; this is a result of separation during the development and evolution of symbols as expressive tools, and the artificial symbol serves as an outer shell for Thinking Symbols. Of course, from a broader perspective, the principle of symbol-meaning separation can be generalized to the separation between physical space symbols and imaginative space symbols (i.e., Thinking Symbols). However, this paper focuses specifically on artificial symbolic systems, where this degree of separation between the symbol and its assigned meaning is more pronounced—that is, where meaning itself is not borne by the natural attributes of the symbol’s carrier, thereby lacking the stickiness that would be based on such conceptual foundations. |

| 17 | They constitute the world in which the agent (individual, population) exists; that is, the world is the natural symbolic system composed of the natural symbols that exist within this scope and the properties (Necessary Set) that these natural symbols possess, which constitutes the boundary of their physical world. And these symbols and the Necessary Set they possess thus also determine their cognitive boundaries and the physical boundaries they can operate within (the use of the Necessary Set of natural symbols), and also determine the evolutionary form of the agent and the organs it possesses, thereby converting the necessary set (dimensions and dimensional values) possessed by natural symbols into the dimensions and dimensional values of neural language for description, as determined by survival needs. They often constitute the projection of objective things (or matters/reality) in an agent’s cognition, but do not necessarily enter the tool symbolic system, existing instead as imaginative symbols. |

| 18 | Human cognition of the attributes of natural symbols, i.e., the subjective necessary set of a symbol (the set of its essential attributes—the subjectively cognized portion). |

| 19 | Aside from the Thinking Symbol and its corresponding symbolic system—Thinking Language—both the Functional Tool Symbolic System and the Expressive Symbolic System can be regarded as systems based on natural symbols, including physical objects and sounds. Of course, if defined from a broader scope and higher-dimensional perspective, imagination itself is based on neural activity, which is also grounded in natural symbols. However, since we primarily consider the scale of human capabilities. |

| 20 | The symbols and symbolic systems formed within the imaginative space shaped by an individual’s capabilities are referred to as Thinking Symbols and Thinking Language. Their shared consensus forms symbols and symbolic systems carried by natural symbols in physical space. See Appendix G. They (Thinking Symbols and Thinking Language) do not belong to the category of symbols primarily discussed in this current section; strictly speaking, the symbols focused on in this section are those existing in physical space. This is because a central argument of this paper is the separation between symbols in physical space and symbols in the imaginative space (i.e., meaning), and thus we do not elaborate further on Thinking Symbols and Thinking Language in this particular context.) |

| 21 | This transmission also includes the same individual’s views on the same thing at different times. |

| 22 | i.e., the construction of an agent’s symbolic system (either individual or populational), which can be the learning of the symbolic system of the world it inhabits—that is, the symbolic system formed by the natural symbols (symbols, necessary set) existing within that scope—or the learning of other symbolic systems, for example, of a world filtered by humans, such as the training sets used for video generation. At the same time, this also often implies that the inability to generate correct fonts in video generation may often be a manifestation of the differences in innate knowledge between humans and AI, i.e., a mismatch between the concepts and value knowledge created by perception, thereby exhibiting a lack of stickiness, such as treating some static symbolic systems as dynamic, or some static things as dynamic things. This, in turn, reflects the intrinsic differences between design evolution and evolutionary evolution. |

| 23 | or, in other words, a deliberately manufactured world, which is often the main reason current AI can function. That is, the effectiveness and stability of present-day AI are the result of a deliberately manufactured world. |

| 24 | Actually, strictly speaking, this is not limited to artificial symbols; it also includes the functions a tool exhibits in different scenarios, as well as the cognition of that tool at different times and in different contexts. From a human perspective, the tool itself may not have changed, but the cognition awakened by changes in context will differ. However, this is not the focus of this paper, because tool symbols derived from or based on natural symbols often possess strong conceptual foundations, i.e., carried by the natural attributes of the symbol itself, whereas artificial symbols, on the other hand, are indeed completely separated (in terms of their meaning from any inherent natural attributes), including late-stage pictograms. However, it should be noted that although symbols and meanings are separate in artificial symbols, the internal stickiness of different artificial symbolic systems varies; this refers to the internal computation and fusion of meanings after they have been assigned. For example, the stickiness of loanwords is weaker compared to that of semantically transparent compounds (words whose meaning is computed from their parts), as they lack the conceptual foundations and associations that are formed after a symbol is endowed with meaning. For instance, compare the loanword ‘pork‘ with the compound ‘猪肉’ (pig meat), or ‘zebra’ with ‘斑马’ (striped horse) [15]. Moreover, pictograms originate from the abstraction of pictorial meaning, and since humans mostly cognize the world through images, the fusion of meaning and symbol in pictograms is more concrete—especially in the early graffiti stages of symbol formation, where we can understand the general meaning of cave graffiti without any knowledge of the specific language. However, it is important to note that these meanings are not innately attached to the symbols but must be endowed through training as indirect projections (i.e., unlike the inherent attributes and meanings possessed by a tool itself), which means the individual learns from and abstracts the external world. Therefore, the internal stickiness within such a symbolic system is a property reflected by the system’s internal design after meaning has been endowed, which in turn constitutes both symbolic stickiness and conceptual stickiness. |

| 25 | This alignment of capabilities essentially reflects an alignment at the organic level. Otherwise, even if we solve the symbol grounding problem, AI will still undergo conceptual updates through its subsequent interactions with the world, thereby forming its own language or concepts, leading to the Stickiness Problem, and causing the rules formulated with symbols to become ineffective. |

| 26 | The so-called intermediate layer, which is classified according to the standard of human cognitive form27, refers to the part of an agent’s internal space that can be consciously cognized by its autonomous consciousness, as well as the part that is potentially cognizable (which is to say, the objects we can invoke and the thinking actions we can perform in the imaginative space via self-awareness, including projections of external-world things in the mind—i.e., direct perception—and our imagination, i.e., the reproduction, invocation, and distortion of existing perceptions. It is a presentation and computation space primarily constructed from the dimensions and dimensional values shaped by the agent’s sensory organs, such as sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste). This distinguishes it from the underlying space, which constitutes consciousness but which consciousness itself cannot operate on or concretely perceive (this reflects a division of labor and layering within the agent’s internal organ structure, which packages and re-expresses neural signals for presentation to the part constituting the ‘self’. This process further packages the neural signals of the necessary set of natural symbols (i.e., a description of that set via the sensory system) initially perceived from the external world and presents them to the ‘self’ in the intermediate layer, thereby constituting the parts that the agent’s ‘self’ can control and the content that is reported to it, facilitating perception and computation for the ‘self’ part). The underlying space can often only realize its influence on the intermediate layer indirectly. For example, when we use an analogy to an object or memory to describe a certain sensation, that sensation—with its nearly unknown and indescribable dimensions and dimensional values—is often the value knowledge from the object’s projection in the underlying space, which is then indirectly projected into the intermediate layer space and concretized via the carrier of similarity (the analogy). Conversely, the same is true; we cannot directly control the underlying space through imagination, but must do so through mediums in the imaginative or physical space. For instance, we cannot purely or directly invoke an emotion like anger. Instead, we must imagine a certain event or use an external carrier (such as searching for ‘outrageous incidents’ on social media) to realize the invocation of the neural dimensions and dimensional values that represent anger. Although the intermediate space is entirely constructed by the underlying space, in this paper, we focus on the aspect where the underlying space indirectly influences the intermediate layer space, namely, through emotional paths and the emotional valuation of beliefs; thus, we can summarize simply that the intermediate layer space is the place where neural signals are packaged and presented to the autonomous cognitive part for management. |

| 27 |

In Appendix O, we have discussed the possibility of agents that think directly using Neural Language as their Thinking Language. In Appendix K.1, we discussed that the reasons for AI’s inexplicability include not only differences in Thinking Language caused by innate knowledge, but also the absence of an intermediate layer, which is itself caused by differences in innate knowledge. That is, its internal Thinking Language is the underlying language relative to humans—i.e., raw neural signals (Neural Language)—unlike humans who think using neural language that has been packaged in the intermediate layer. This also indicates that current research on having AI think with human symbols, such as through chain-of-thought or graphical imagination, is a simulation of human intermediate-layer behavior, or constitutes the construction of a translation and packaging layer from the underlying language to the “intermediate layer language.” However, its (the AI’s) Thinking Language (i.e., the part operated by the ‘self’) is still constituted by neural signals (Neural Language) that are composed of its innate knowledge and are not modified or packaged by an intermediate layer, rather than an intermediate-layer language of a human-like self-cognitive part. This therefore leads to the fact that AI’s concepts themselves are constituted with neural signals as their language (neuro-concepts), rather than being presented and expressed in an intermediate symbolic form as is the case for humans. Consequently, this method merely constructs a new Tool Language layer that assists with computation and analysis.

It should be noted that although this paper has emphasized that Tool Language itself can become Thinking Language (by forming projections in the intermediate layer through perception to constitute conceptual vectors, Thinking Symbols, or Thinking Language (a symbolic system)), it is also important to note another point emphasized in this paper: the formation and form of Tool Language, i.e., that the human symbolic system (the Tool Symbolic System) is the outer shell of human thought (the Imaginative Space Symbolic System). That is, the formation of this Tool Symbolic System stems from the external expression of the product of the combination of human innate knowledge and the world, whereas an AI learning and using human symbols is, in essence, the Triangle Problem of different Thinking Languages using the same Tool Language. And the root of these differences lies in the projection of the same thing in the internal space—i.e., the differences in the dimensions and dimensional values of its representation, as well as the differences in the dimensions and dimensional values of some innate evaluations. It is therefore not surprising that AI exhibits human-like cognition and mastery of the necessary set of natural symbols in the objective world, i.e., ‘science.’ What is surprising, however, is whether AI can understand human social concepts and the realization of social functions constituted by beliefs formed from these social concepts.

|

| 28 | This innate evaluation is often shaped and represented as our qualia and preferences—typical examples being the evaluation of and preference for the senses of taste and smell—which constitute so-called ‘hereditary knowledge’. This, in turn, shapes the direction and foundation for tendencies and rationality, thus serving as dimensional values that participate in computation. It should be noted that this paper has a strict definition of knowledge (Appendix G); in our definition, this ‘hereditary knowledge’ is not conceptual knowledge but rather belongs to innate value knowledge. As a form of innate evaluation, it recognizes the focal points of, and evaluates the rationality of, the dimensions and dimensional values perceived by sensory organs, thereby determining the invocation of subsequent actions. This, in turn, determines the developmental direction of an individual’s postnatal Thinking Language and tool language. Therefore, this sameness allows for the existence of similar things and concepts—such as ‘mama,’ ‘papa,’ language, clothing, bowls, myths, calendars, and architecture—even in human civilizations that have never communicated with each other. |

| 29 | The formation of its mechanism stems from the relationship between the population and the world constituted by the natural symbolic system it inhabits. This is manifested in the degree of an individual’s mastery over the necessary set of natural symbols within this world, and in the internal organs acquired as a result—that is, the internal and external functions formed through the selection and evolution of internal organs based on cost-benefit considerations geared towards survival rates, which constitute innate knowledge. Of course, strictly speaking, this collective body of internal organs (at the class level) constitutes the definition of the population, while at the level of specific objects based on these internal organs, it constitutes the individual. That is, the individual (a specific object) and the population (a class) are the carriers of this collection of internal organs. |

| 30 | However, such deviations are generally limited, as they are constrained by the stickiness shaped by human organic structure—namely, the value knowledge system. Even when deviations occur, they are often corrected over time. These differences tend to manifest more in the form of variation in expression, and do not necessarily imply that a subsequent performance will be better than the previous one, as seen in relatively stable tasks such as mathematical problem-solving. This often reflects issues concerning the definition of different symbolic systems: i.e., some symbolic systems are strictly static (but their invocation and use are dynamic, and this is not a simple subset relationship, meaning that a certain kind of distortion formed due to the agent’s unique state may arise), where the attributes of their symbols cannot be arbitrarily changed (traditionally referred to as formal symbolic systems), whereas other symbolic systems, such as natural language symbolic systems, are relatively or very flexible. |

| 31 | The recognition and manipulation of symbols are respectively reflected in Triangle Problem 1 and Triangle Problem 2; see Section 3.1 for details. |

| 32 | i.e., the Thinking Symbols and Thinking Language (a symbolic system) of the intermediate layer in the agent’s internal space. |

| 33 | Primarily with respect to the listener (or reader). |

| 34 | More broadly speaking, this also includes conversions similar to that of sound to text; i.e., here we emphasize a scenario where the emission (of the symbol) is correct and the environment (of transmission) is lossless. Therefore, the interpretation of symbols necessarily involves concepts, and context is formed through these concepts. Differences in concepts, i.e., differences in thinking symbols, may lead to the emergence of insufficient context. |

| 35 | For example, with respect to human recognition and cognitive capabilities, our description and segmentation of facial regions are limited. AI, however, may possess more such definitions, and these definitions might be unrecognizable by human cognition, thereby preventing us from using them (their symbols and symbol meanings, i.e., dimensions and dimensional values) to establish concepts and theories (context and its correctness), such as constructing a class theory to describe the structure of the face and its generation (in contrast, we have our own theories of artistic techniques, like painting, and use a tool symbolic system we can operate to realize the creation of artificial symbols). This may be due to a lack of Differentiability caused by differences in innate knowledge, or phenomena that are unobservable, such as recognition beyond the visible spectrum. And this capability of possessing more regional definitions, i.e., the capability to form symbols, is often reflected in the construction and operation of the symbolic system, which in turn is reflected in generative capabilities, as in AI video generation. This paper regards generativity as the definition, construction, and operation of symbolic systems, and the source of this operation is motivation, which can be external or internal. Therefore, the differences in our capabilities lead to differences in our symbolic capabilities, which in turn lead to differences in the symbolic systems (theories) we can construct using symbols, as well as differences in our ability to use these symbolic systems (i.e., we humans, through the form of context, turn it into a relatively dynamic symbolic system that we can only partially use). |

| 36 | That is, individual symbols (words, sentences, texts) can represent a set of meanings even when detached from context. Or, in an insufficient context (and it should be noted that this insufficient context may itself be a contextual ensemble composed of a set of contexts that are difficult to describe and perceive—effectively, the Value Knowledge System), we first conceive of possible meanings, and then these are subsequently concretized into a describable and clearly perceivable context. |

| 37 | The shaping of the underlying space under postnatal education, i.e., the functions realized through the formation of beliefs from the fusion of acquired value knowledge and concepts. |

| 38 | Including the negation of authority. |

| 39 |

Of course, learning ability itself is also determined by organic structure. For detailed definitions of innate knowledge and concept types, see Appendix F and Appendix L. Therefore, learning ability is internally determined by neural structures (i.e., the brain), while its realization depends on external components relative to the neural architecture—namely, the corresponding perceptual and operational organs.

However, strictly speaking, the essence of self-awareness is the construction and use of Thinking Language (a symbolic system), which is an internal activity; i.e., it does not necessarily need to have Tool Language capabilities. At the same time, self-awareness has different levels. The most fundamental level of self-awareness is defined by ‘self-interest formed by organic structure’ and constitutes motivation and drive, without requiring learning ability. This is then built upon the capabilities formed by internal organs, i.e., reflected in Psychological Intelligence (Appendix L), constituting different levels of self-awareness definitions. However, since our focus is on whether an AI that already possesses Thinking Language and Tool Language capabilities, or in other words, an AI with human-like capabilities, has self-awareness, the definition here adopts a higher-level definition without going into a detailed classification. That is, we are concerned with whether an agent, centered on its own interests (constituted by the two sides of the same coin: cost and benefit), and capable of using Thinking Language and Tool Language, possesses self-awareness (although Tool Language is not necessary for the formation of self-awareness, if the ability to use Tool Language, such as communicating with humans through text, is absent, then we would be unable to perceive, observe, or judge whether the AI possesses self-awareness). Therefore, from a resultant perspective, an AI that possesses ‘self-interest formed by organic structure’ has self-awareness; from the stricter definition given in terms of manifestation, an AI that possesses ‘self-interest formed by organic structure’ and also has learning ability has self-awareness.

However, on the other hand, from the deterministic perspective of this paper, self-awareness is essentially determined by external materials or, in other words, the existence of the physical world, and does not genuinely exist. Therefore, whether self-awareness genuinely exists depends on the perspective of the symbolic system from which one starts. From the perspective of the Higher-dimensional Broader Symbolic System—whose symbols and necessary sets encompass those of both the natural symbolic system and the agent’s symbolic system—an absolute determinism emerges. If one starts from the natural symbolic system, a form of determinism also emerges (i.e., the carrier of will itself is the natural symbol and its necessary set); the difference between these two determinisms then lies in the scope and descriptive methods constituted by their precision and scale. However, when starting from the perspective of the agents (i.e., from the agent’s symbolic system), due to the limitations of their scope and capabilities, there exist their so-called ‘self-awareness’, subjectivity (finitude), and randomness. This determinism is not disconnected from the paper’s content; rather, it serves the agent (individual or population) in describing natural symbols to the greatest extent possible based on its own capabilities, thereby forming the lowest possible randomness and thus reflecting the efficiency of their ‘scientific’ symbolic systems. This is especially reflected in Triangle Problem 1 concerning the construction of symbolic systems (Thinking Language, Tool Language) and in Triangle Problem 2 concerning the use of symbolic systems, as well as in the ‘advanced concepts’ within symbolic jailbreak (Appendix M.5), and it is also reflected in current research on topics such as AI’s exploration and discoveries in the natural sciences (Appendix O).

|

| 40 | The so-called Necessary Set refers to the attributes possessed by a symbol. For different symbolic systems (e.g., the Natural Symbolic System, an agent’s symbolic system), it is divided into an Objective Necessary Set and a Subjective Necessary Set from different perspectives, and the Necessary Set we refer to here is the Subjective Necessary Set. The so-called Objective Necessary Set refers to the natural attributes (dimensions and dimensional values) of a natural symbol that exist independently of the agent’s cognition, which is the necessary set within the Natural Symbolic System. The so-called Subjective Necessary Set is the description of the Objective Necessary Set via neural signals, which the agent perceives through its sensory organs based on innate knowledge (i.e., the dimensions and dimensional values of the neural signals); then, this neural signal is further packaged and restated in the intermediate layer and conveyed to the ’self’, forming concepts constituted by the intermediate layer language (i.e., Thinking Language). These concepts include the cognition of the Objective Necessary Set and the social concepts formed based on this cognition and social relationships, which, in the form of beliefs, create social functions and drive individual behavior. For example, gold, on the one hand, possesses natural attributes that exist independently of humans, and on the other hand, possesses social functions formed by concepts in the human mind in the form of beliefs. The Necessary Set mentioned here refers to the Subjective Necessary Set within the agent’s symbolic system, which is the existence that arises from the symbol’s presence, as determined by the judgment tools within the context of the individual agent’s cognition. |

| 41 | Because the presentation and operation of analysis and reasoning are by no means limited to an agent’s internal space, for us humans, a vast amount of knowledge and simulated cognitive computation is realized through external, physical-world containers. As introduced in Appendix L, the invention of symbols and tools extends our observational and analytical capabilities; without physical-world tools like pen, paper, and symbolic inventions, our cognitive computational capabilities would decline significantly, while at the same time, the limitations of memory invocation and concretization would prevent the formation of continuous analysis. On the other hand, items such as guidebooks, rituals, architecture, and notes serve as humanity’s external knowledge, or rather, as the physical existence of beliefs, thereby constituting evidence that human knowledge and judgment tools do not exist entirely in the internal space. Therefore, if a ’world model’ were detached from the external, the following questions would arise. Question 1: Does the author of a dictionary fully remember all its contents? In other words, is all the literal content of the dictionary part of their knowledge? Question 2: For a pilot who can use a manual, is the knowledge within that manual considered their internal knowledge? Therefore, this paper considers a ’world model’ to include external organs, which strictly speaking, includes Tool Language in the physical space, i.e., the Tool Symbolic System. Thus, the so-called world model is the set of an agent’s internal and external organs. The operation of the internal space on the external space realized thereby, i.e., the operation of Thinking Language on Tool Language, and these operational capabilities are themselves also part of knowledge; therefore, Thinking Language is by no means static and purely internal, but is rather a dynamic symbolic system formed by existing internal accumulations and new additions brought by the projection of the external into the internal, and this is also what is emphasized by the theory of context. Additionally, from a deterministic perspective, physical existence determines mental existence, but here, we still adopt the human local perspective and analytical viewpoint to discuss and argue that a world model should include the external. |

| 42 | That is, the supporting beliefs underlying a concept, which are often shaped by the agent’s innate structure(knowledge) and learned from its environment. See Appendix G for further details. |

| 43 | This form of pain should not only be sensory but also moral in nature, and should align as closely as possible with human experience, thereby enabling the realization of human social-conceptual functions within AI. |