1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a supraventricular tachyarrhythmia caused by uncoordinated electrical activation of the atria, resulting in ineffective atrial contraction. [1,2] The estimated prevalence of AF in the United States is 1%, and this figure increases to 6-12% in the elderly population. [3,4,5]

Acute AF is the arrhythmia most frequently requiring treatment in the emergency department (ED). [6,7] It accounts for between 3-4% of all medical consultations in Canada and the United States, with 430,000 visits to the ED every year. [7,8] Acute AF generally refers to symptomatic episodes of recent onset (detected for the first time, recurrent paroxysmal or recurrent persistent episodes) and lasting less than 48 hours, for which cardioversion is a safe treatment option. [7,9]

The two main approaches to controlling this arrhythmia in the ED are rate control and rhythm control. Negative chronotropic drugs are used for rate control and are the preferred method for controlling ventricular response in chronic AF. [7] In rhythm control, reversion to normal sinus rhythm is achieved by pharmacological cardioversion (PC) or electrical cardioversion (EC), and the patient can usually be discharged within a few hours. This is the preferred method for controlling acute AF in the ED. [7] On the other hand, younger patients tend to be more symptomatic when presenting AF, and may obtain greater benefits from a rhythm control strategy in the ED, improving the symptoms-free time without increasing adverse events. [10]

There is little evidence for many aspects of the management of acute AF in the ED. EC is the preferred option for hemodynamically unstable patients with AF. [1] However, there are no clearly defined guidelines as to whether the initial form of rhythm control in hemodynamically stable patients should be PC or EC. PC does not require sedation. However, it is associated with a lower success rate (approximately 50%) and has the side-effects of antiarrhythmic drugs. [2] EC requires anesthesia for appropriate sedation during the procedure, but it has a higher success rate, which reached 88% in a study by Fried et al. [2,11] EC can also be used after PC, significantly increasing the success rate. A recent study found no significant differences between the strategies of EC, and PC followed by EC. Both approaches were effective in restoring sinus rhythm and reducing the length of hospital stay. [7]

The main objective of the present study was to compare the efficacy in terms of the success rate of conversion to sinus rhythm in patients with uncomplicated AF of recent onset, using two strategies in the ED: attempted PC (followed by EC if necessary), and attempted EC.

2. Material and Methods

We conducted a retrospective, analytical observational study in patients with acute AF admitted to the ED of a tertiary care hospital (AF Cardiac Emergency Register in Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti, Lugo, Spain: RECUFA-HULA). The patients were recruited from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2020.

Patients who arrived in the ED with palpitations underwent examination for vital signs (heart rate and blood pressure), and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed. They were immediately treated with EC if they were diagnosed with AF and presented hemodynamic instability. The clinical approach in hemodynamically stable patients is based on the patient’s clinical features, the duration of the arrhythmia (longer or shorter than 24 hours), and whether the patient is being treated with anticoagulants.

2.1. Study Design and Setting

All patients with AF presenting in the ED during a period of four consecutive years were retrospectively evaluated for inclusion in this study. Demographic and clinical information was obtained from the center’s electronic medical records, after obtaining due patient consent. Patient destination at discharge, the start of anticoagulation treatment, and bleeding complications during follow-up were recorded.

2.2. Selection of Participants

The study included hemodynamically stable patients diagnosed with acute AF of at least 3 hours’ duration, with symptoms requiring early management, and for whom PC or EC was an appropriate clinical option. The PC or EC strategy began within 48 hours of arrival in the ED, or during the first 7 days with appropriate anticoagulation treatment for at least four weeks prior to the episode.

The exclusion criteria were: lack of informed consent, patients with hemodynamic instability requiring immediate cardioversion, AF secondary to an acute process (pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, etc.) and spontaneous reversion to sinus rhythm. Patients with previous episodes of acute AF or with heart valve disease were not excluded if they were receiving appropriate anticoagulant treatment.

2.3. Methods and Measurements

2.3.1. Data Extraction

The electronic medical records of all the patients were reviewed, and the clinical information was recorded on a form prepared specifically for the study. The clinical variables collected included: demographic data (age and sex), personal cardiovascular history (high blood pressure, dyslipidemia, heart failure, coronary artery disease, heart valve disease and peripheral vascular disease) and clinical history related to cardiovascular disease (diabetes mellitus, obesity, chronic kidney disease, smoking, oncohematological diseases), baseline antiarrhythmic, cardiac and anticoagulant treatments, thrombotic and bleeding risks (CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores), whether it was the first episode of arrhythmia and its duration, the medical procedure performed (PC and EC), whether hospital admission was required, treatment at discharge, and thromboembolic and bleeding complications.

A clinical evaluation, including a transthoracic echocardiogram, was performed during patient follow-up.

Cardioversion Treatments

The treatment strategies included PC or EC during patient stay in the ED, or delayed programmed EC for rate control. PC or EC was considered successful when reversion to sinus rhythm was achieved, as demonstrated in a post-procedure ECG.

In the eligible patients, the treating physician in the ED was responsible for the approach and treatment in each case, according to the established clinical protocol for the management of AF in the ED, and agreed upon by the cardiology and emergency departments. The clinical decision was based on the patients’ clinical stability, the duration of the AF and adequate anticoagulation. The treatment was personalized in each case, including: selection of the antiarrhythmic drugs and doses used, the energy setting in EC and the number of attempts, and the sedation and analgesia used.

All the participants gave written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the local research ethics committee.

The outcome variable was the success rate of conversion to sinus rhythm in both the PC and EC groups. The need for additional procedures (consecutive EC) for rhythm control was also analyzed. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compiled in each group and compared in search of differences preventing analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Qualitative variables were reported as numbers (%). Inter-group differences were calculated with the chi-squared test. Continuous variables were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and inter-group differences were analyzed with the Student-t test.

Statistical significance was considered for p<0.05. The analyses were performed using the SPSS version 21.0 statistical package.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics

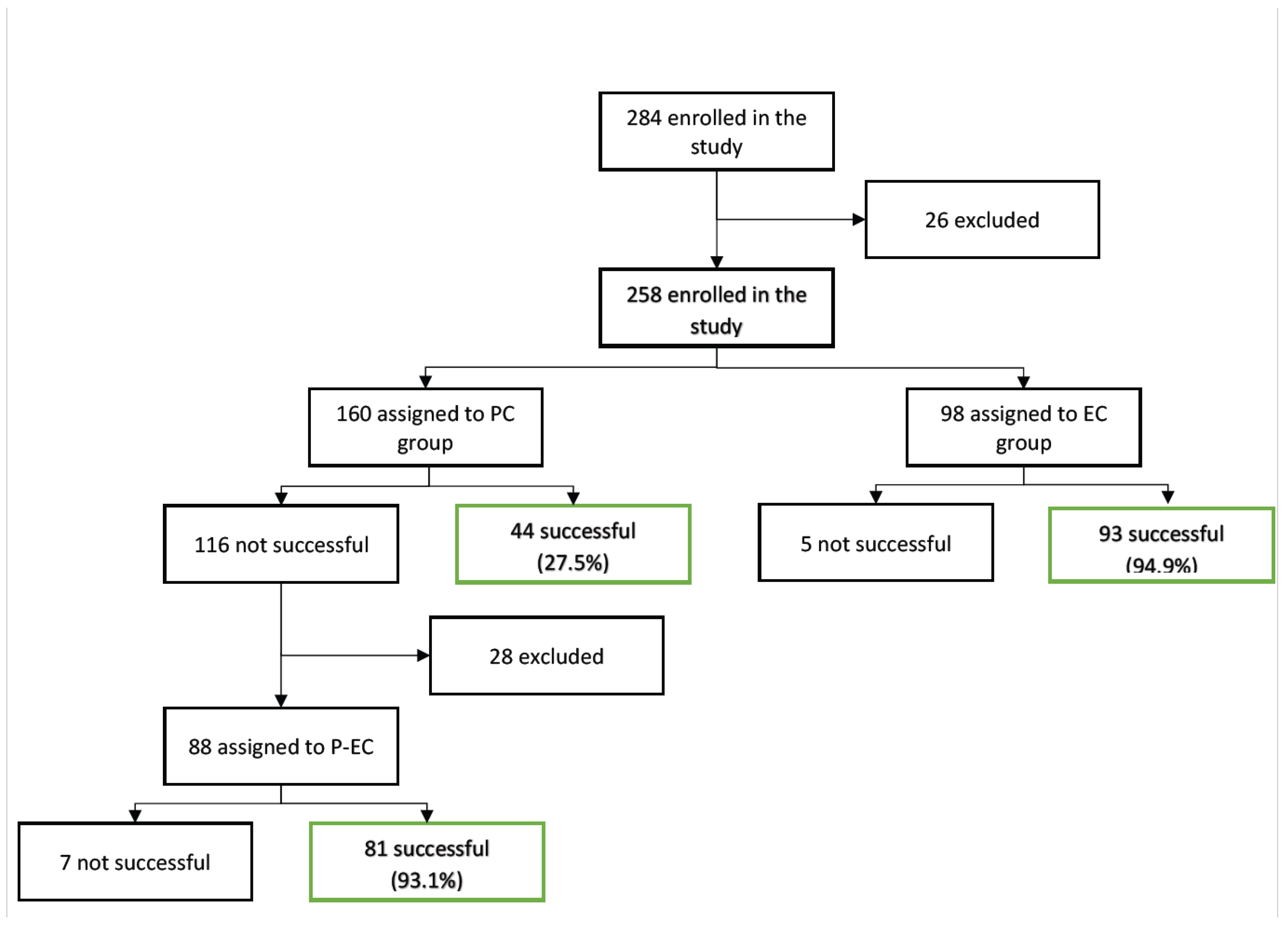

The study included 401 cardioversion procedures in a total of 284 patients (

Figure 1). The subjects were classified into three groups, based on the initial rhythm control strategy: pharmacological cardioversion (PC) in the emergency department (n=160); electrical cardioversion (EC) in the emergency department (n=98); and delayed programmed electrical cardioversion (EC) (n=26). In our study, the analysis focused on the patients with cardioversion procedures performed during their first visit to the ED (n=258) and excluded patients with delayed EC and losses during follow-up.

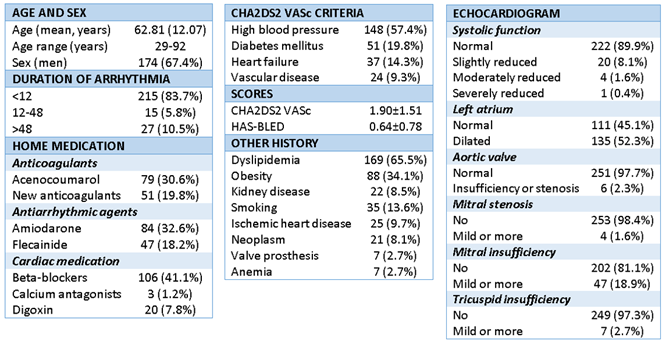

The mean patient age was 62.81±12.07 years (range 29-92), and 174 were male (67.4%) (

Table 1). AF was de novo in 38 subjects (14.7%), and 218 (84.5%) had episodes of paroxysmal AF. The mean duration of symptoms onset was less than 12 hours in 215 patients (83.3%). The mean CHA

2DS

2-VASc score was 1.90 ± 1.51, and the mean HAS-BLED score was 0.64 ± 0.78.

PC: pharmacological cardioversion in the emergency department; EC: electrical cardioversion in the emergency department; P-EC: electrical cardioversion after pharmacological cardioversion in the emergency department.

Most patients had comorbidities (

Table 1). The most common: dyslipidemia (DLP) (65.5%), Hypertension (HT) (57.4%), obesity (34.1%), diabetes mellitus (DM) (19.8%), heart failure (14.3%), smoking (13.6%), coronary artery disease (9.7%), peripheral vascular disease (9.3%), chronic kidney disease (8.5%) and heart valve disease (8.1%). 8.1% had oncological issues, and 2.7% had anemia.

As regards home medication (

Table 1), 130 patients (50.4%) were receiving prior anticoagulant treatment, mainly with vitamin K antagonists (30.6%) versus direct-acting anticoagulants (19.8%). A total of 131 patients were being treated with antiarrhythmic drugs, mainly amiodarone (32.6%) and flecainide (18.2%). In turn, 129 patients were being treated with negative chronotropic drugs: A total of 106 (41.1%) were being treated with beta-blockers, 3 (1.2%) with calcium antagonists, and 20 (7.8%) with digoxin.

After cardioversion in the emergency department, 168 patients (65.1%) were referred to cardiology, and only 7 (2.7%) required hospital admission. At discharge, 178 subjects received anticoagulation treatment (69.0%), with vitamin K antagonists being the most commonly used drugs(40.7%). During the 3-month follow-up, there were 5 cases of bleeding (1.9%), which was light bleeding in all cases, in the form of: epistaxis (1), hematuria (3 cases) and hemoptysis (1 case). No thromboembolic events were recorded.

All patients underwent a transthoracic echocardiogram during follow-up (

Table 1). Left ventricular systolic function was preserved in 222 patients (86%), 135 (52.3%) had a dilated left atrium (mild in 51.2%), and mitral insufficiency was the most prevalent valve disorder, present in 56 cases (18.9%), which were mostly mild (14.1%).

3.2. Cardioversion Strategy and Clinical Characteristics

PC was the initial strategy in 160 patients. The success rate was 27.5% (44 patients), with reversion to sinus rhythm up to discharge from the ED. In the 116 cases (72.5%) in which PC was not effective, sequential EC was performed in 88 patients and proved effective in 81 cases (success rate 93.1%). EC as an initial strategy was performed in 98 subjects and was effective in 93 cases (success rate 94.9%).

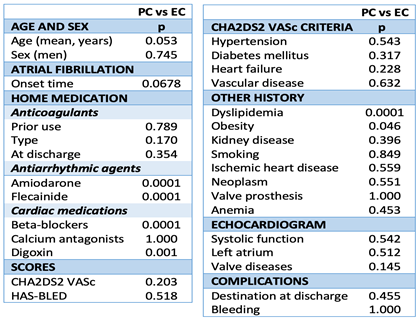

Statistically significant differences for the primary objective (cardioversion to sinus rhythm) were observed between the two strategies, with better results in the EC group (95.3% vs. 76.8%; p=0.0001).

As regards the clinical features, significant differences were only observed for the presence of dyslipidemia, obesity, anti-arrhythmia treatment and prior negative chronotropic treatment, which were greater in the PC group compared to the EC group (p=0.0001, p=0.046 and p=0.0001, respectively) (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Atrial fibrillation is the arrhythmia that most frequently requires treatment in the ED. [1,7] In particular, acute AF is a condition in which the rhythm control strategy using CP or EC is a safe option. [9] There is consensus among scientific societies that EC is the method of choice in cases of AF with hemodynamic instability. [1] This is not the case in patients who are hemodynamically stable, where both strategies can be used interchangeably, depending on the clinical characteristics involved.

In the present study we evaluated the differences in efficacy between two cardioversion strategies: pharmacological (with or without sequential EC) and electrical, in hemodynamically stable patients with acute AF admitted to the ED.

Age is the most important risk factor in the development of AF. [15] The mean age in our study was 62.81 years, there were few young people, and there was a strong tendency towards advanced ages (range 29-92 years). These data are similar to those published by Stiell et al. and Scheuermeyer et al., with mean ages of around 60 years in both groups. [7,14] More than half of the subjects of the study were men (67.4%), which is consistent with the lower incidence of AF in women, although this relationship tends to invert with advancing age. [16] A total of 84.5% of the subjects had experienced a previous episode of paroxysmal AF, and in 83.3% of the cases the duration of symptoms was less than 12 hours until contact with the ED.

Most of the patients in the study presented comorbidities. AF is a multisystemic disorder with multiple direct causal interactions with comorbidities. [15] Huxley et al. considered that more than half of the AF burden is potentially avoidable through the optimization of cardiovascular risk factors. [17] In our study, 57.4% of the patients had a history of arterial hypertension. Chronic arterial hypertension leads to remodeling and profibrotic changes in the left atrium and ventricle. [18] In a recent study, arterial hypertension was the most important risk factor for the development of AF, accounting for almost 25% of the cases. [17] Furthermore, 34.1% of the patients had a body mass index of over 30 kg/m2. Sustained obesity is associated with multiple cardiovascular risk factors, including arterial hypertension and DM, which represent an important substrate for atrial remodeling, and contribute to the onset and persistence of AF. [19] There are also strong links between weight gain and electroanatomical remodeling of the atria. [20] The prevalence of obesity has increased significantly in recent decades, and it now accounts for 17.9% of all AF cases. [17,21] A total of 19.8% of our patients had DM. Patients with type 2 DM have a 40% greater risk of developing AF than non-diabetic subjects. [22,23] A total of 13.6% of the patients in the study were smokers, and an increased risk of AF has been reported in smokers versus non-smokers. [24]

Our study included 401 cardioversion procedures in a total of 284 patients, with the primary endpoint being the success rate of conversion to sinus rhythm in both the PC and the EC groups. PC was the initial strategy in 160 subjects (56.3%), with low levels of effectiveness (27.5%). In patients in which PC proved ineffective and who underwent sequential EC, the latter was found to be effective in 93.1% of the cases; the overall effectiveness thus increased considerably (75.9%) with the combined strategy (pharmacological and electrical cardioversion). Stiell et al. suggested higher levels of efficacy, reaching 96%. [7] However, unlike this study, a single antiarrhythmic drug was not used in the PC arm, and this may be associated with different success rates depending on the drug used. The ESC guidelines on AF recommend flecainide or propafenone (except in patients with severe structural heart disease) and vernakalant (except in patients with recent acute coronary syndrome or severe heart failure) as antiarrhythmic drugs with class I indication for rhythm control in PC for acute AF. [1] A recent meta-analysis has reported an overall efficacy of 85.25% with this strategy. [2]

EC was the initial strategy in 98 subjects (34.5%), with high success rates (94.8%). These data are consistent with the studies by Stiell et al. in which the EC arm showed a success rate of 92%, and Fried et al., in which the success rate reached 88%. [7,11] The percentage of patients in this strategy was lower, despite its extremely high success rate. This lower level of use may be related to the fact that it is considered to be a more aggressive therapy, and to more limited physician experience in its implementation.

Our study showed significant differences between the two strategies in terms of achieving the objective, with the EC group obtaining better results than the PC group (95.3% vs. 76.8%; p= 0.0001). This is consistent with previous observations by Bellone et al., Danker et al. and Scheuermeyer et al., who reported higher success rates in the group subjected to EC. [12,13,14] Both types of cardioversion proved to be safe procedures, with low complication rates, and only 7 patients (2.7%) required admission to hospital. There were only 5 cases of mild bleeding (1.9%) at three months of follow-up, and no thromboembolic events were recorded. Cardioversion for AF in the emergency department is a safe option, with low complication rates and no differences with respect to programmed cardioversion. [8] The safety profiles of the two cardioversion strategies (EC and PC) are comparable, except for arterial hypotension (which is higher in the PC group), with no significant clinical consequences. [2,7]

The patients were evaluated again over follow-up, and a transthoracic echocardiogram was performed in all cases. A low presence of structural heart disease was observed in both groups: 52.3% had left atrial dilatation (which was mild in 51.2% of the cases).

The decision regarding anticoagulation was made based on the CHA2D2-VASC score, with most of the patients being low risk individuals. A total of 178 patients (69%) received anticoagulant therapy, predominantly in the form of vitamin K antagonists (59%), which is probably related to the fact that there is no funding to cover direct-acting oral anticoagulants for new patients in the Spanish public healthcare system.

5. Conclusions

In hemodynamically stable patients with acute AF treated in the ED, electrical cardioversion is safe and comparatively more effective as a sinus rhythm cardioversion strategy. The efficacy of PC used alone is limited, and additional procedures for rhythm control are therefore often needed.

5.1. Study Limitations

Although this is a single-center, retrospective, non-randomized study, it focuses on the real-life management of patients with acute AF undergoing cardioversion in the ED of a large-volume university hospital. Furthermore, the clinical characteristics of the two groups were balanced and similar to those found in other previously published studies.

Various antiarrhythmic drugs were used in the PC arm, which may be associated with potentially different success rates and adverse effects for each drug. However, the clinical practice guidelines recommend no single concrete drug. The decision therefore corresponds to the supervising physician and is more consistent with daily clinical practice.

The times from AF to cardioversion were recorded from interviews with the patients, and as such the times reported may sometimes be inaccurate. However, they accurately represent the situation found in routine clinical practice.

References

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Hear. J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasai, P.; Shrestha, D.B.; Saad, E.; Trongtorsak, A.; Adhikari, A.; Gaire, S.; Oli, P.R.; Shtembari, J.; Adhikari, P.; Sedhai, Y.R.; et al. Electric Cardioversion vs. Pharmacological with or without Electric Cardioversion for Stable New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370-5.

- Svennberg E, Engdahl J, Al-Khalili F, Friberg L, Frykman V, Rosenqvist M. Mass Screening for Untreated Atrial Fibrillation: The STROKESTOP Study. Circulation. 2015;131:2176-84.

- Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:469-73.

- Michael, J.; Stiell, I.G.; Agarwal, S.; Mandavia, D.P.; A Michael, J. Cardioversion of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation in the Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1999, 33, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiell, I.G.; A Sivilotti, M.L.; Taljaard, M.; Birnie, D.; Vadeboncoeur, A.; Hohl, C.M.; McRae, A.D.; Rowe, B.H.; Brison, R.J.; Thiruganasambandamoorthy, V.; et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomised trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbajosa-Dalmau, J.; Martin, A.; Paredes-Arquiola, L.; Jacob, J.; Coll-Vinent, B.; Llorens, P. Safety of emergency-department electric cardioversion for recent-onset atrial fibrillation. 2019, 31, 335–340.

- Stiell, I.G.; Macle, L. Canadian Cardiovascular Society Atrial Fibrillation Guidelines 2010: Management of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter in the Emergency Department. Can. J. Cardiol. 2011, 27, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Kirkwood, G.; Dibb, K.; Garratt, C.J. Comparison of Atrial Fibrillation in the Young versus That in the Elderly: A Review. Cardiol. Res. Pr. 2013, 2013, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, A.M.; Strout, T.D.; Perron, A.D. Electrical cardioversion for atrial fibrillation in the emergency department: A large single-center experience. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 42, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellone, A.; Etteri, M.; Vettorello, M.; Bonetti, C.; Clerici, D.; Gini, G.; Maino, C.; Mariani, M.; Natalizi, A.; Nessi, I.; et al. Cardioversion of acute atrial fibrillation in the emergency department: a prospective randomised trial. Emerg. Med. J. 2011, 29, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankner, R.; Shahar, A.; Novikov, I.; Agmon, U.; Ziv, A.; Hod, H. Treatment of Stable Atrial Fibrillation in the Emergency Department: A Population-Based Comparison of Electrical Direct-Current versus Pharmacological Cardioversion or Conservative Management. Cardiology 2008, 112, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheuermeyer, F.X.; Andolfatto, G.; Christenson, J.; Villa-Roel, C.; Rowe, B.; Chang, A.M. A Multicenter Randomized Trial to Evaluate a Chemical-first or Electrical-first Cardioversion Strategy for Patients With Uncomplicated Acute Atrial Fibrillation. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2019, 26, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornej J, Börschel CS, Benjamin EJ, Schnabel RB. Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation in the 21st Century: Novel Methods and New Insights. Circ Res. 2020;127:4-20.

- Westerman, S.; Wenger, N. Gender Differences in Atrial Fibrillation: A Review of Epidemiology, Management, and Outcomes. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2019, 15, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huxley RR, Lopez FL, Folsom AR, Agarwal SK, Loehr LR, Soliman EZ et al. Absolute and attributable risks of atrial fibrillation in relation to optimal and borderline risk factors: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2011;123:1501-8.

- Dzeshka MS, Lip GY, Snezhitskiy V, Shantsila E. Cardiac Fibrosis in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:943-59.

- Chatterjee NA, Giulianini F, Geelhoed B, Lunetta KL, Misialek JR, Niemeijer MN et al. Genetic Obesity and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: Causal Estimates from Mendelian Randomization. Circulation. 2017;135:741-754.

- Hruby, A.; Hu, F.B. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. PharmacoEconomics 2014, 33, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, M.M.; Stevens, G.A.; Cowan, M.J.; Danaei, G.; Lin, J.K.; Paciorek, C.J.; Singh, G.M.; Gutierrez, H.R.; Lu, Y.; Bahalim, A.N.; et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 2011, 377, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP et al. American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139-e596.

- Huxley, R.R.; Filion, K.B.; Konety, S.; Alonso, A. Meta-Analysis of Cohort and Case–Control Studies of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, A.; Krijthe, B.P.; Aspelund, T.; Stepas, K.A.; Pencina, M.J.; Moser, C.B.; Sinner, M.F.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Fontes, J.D.; Janssens, A.C.J.W.; et al. Simple Risk Model Predicts Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation in a Racially and Geographically Diverse Population: the CHARGE-AF Consortium. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2013, 2, e000102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).