Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Prevention of POAF

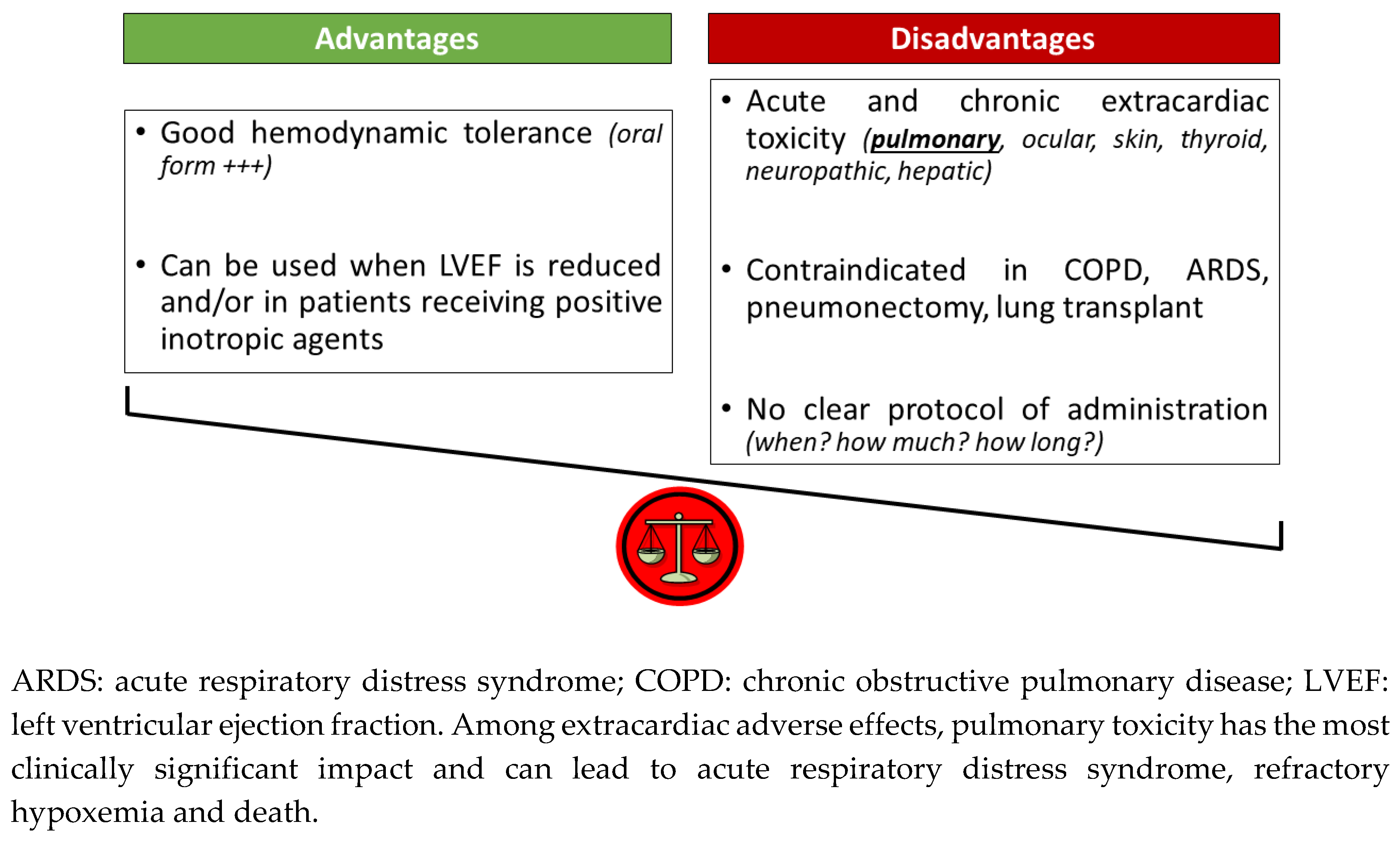

Amiodarone: A Dead Man Walking [22]

Perioperative Optimization of Beta Blockers

Other Interventions

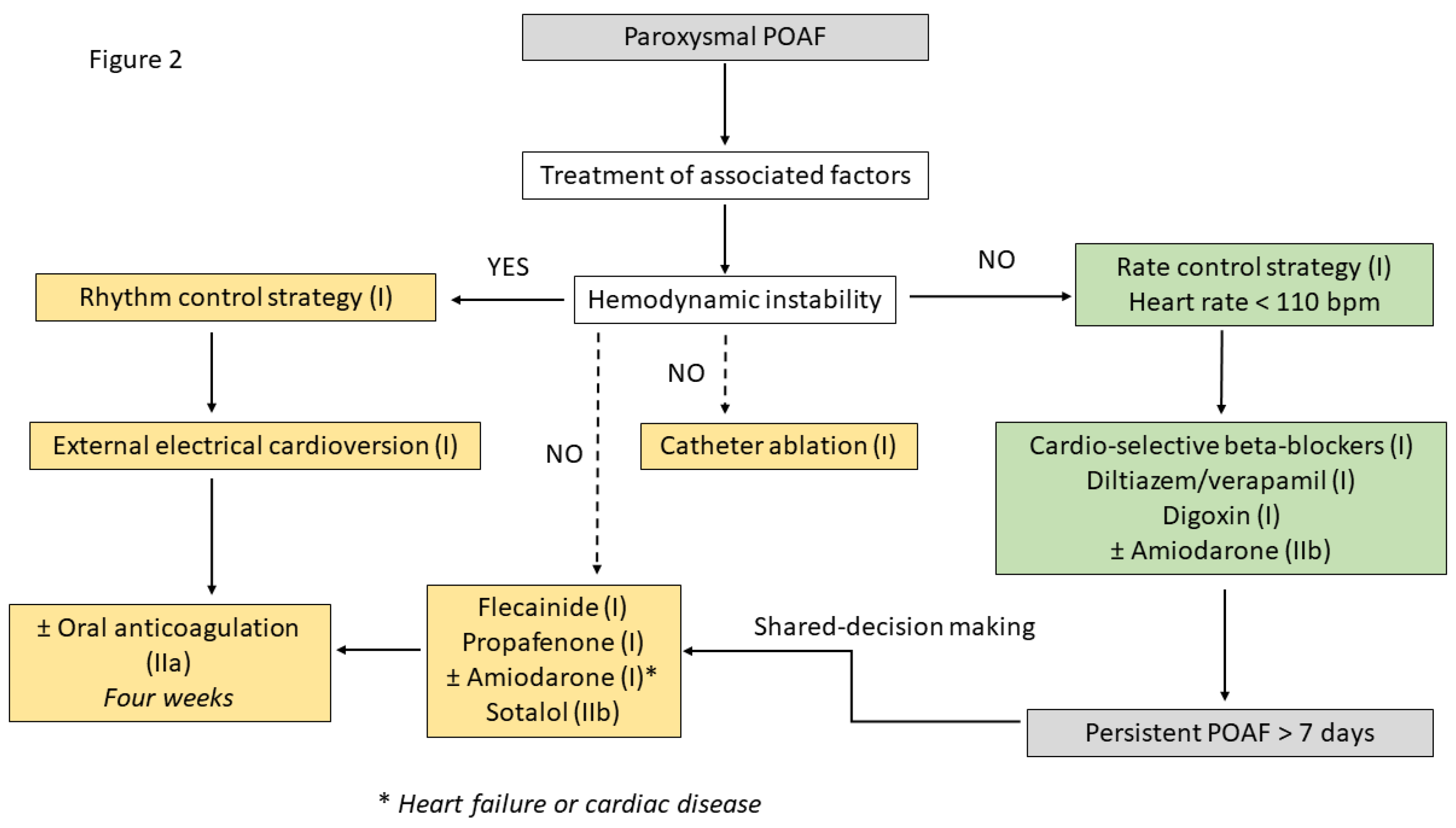

Treatment of POAF

Treatment of Associated Factors

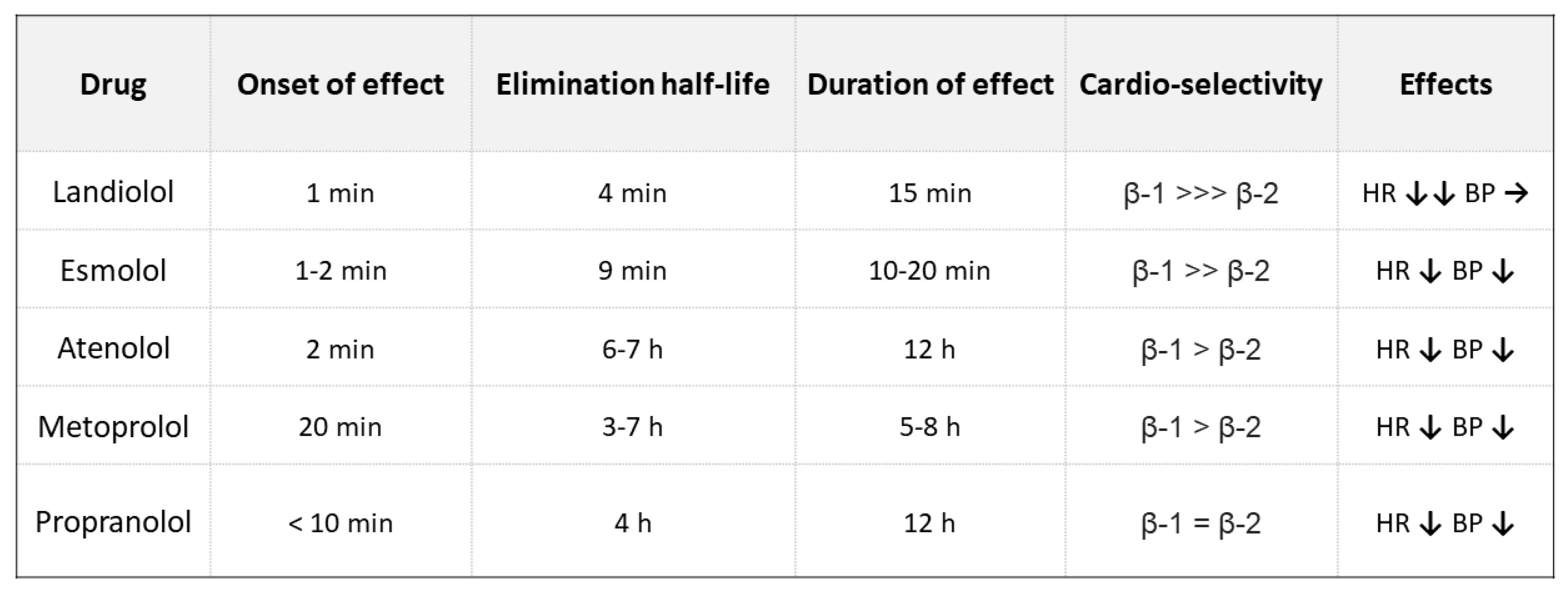

Considering a Rate Control Strategy

Which Place for a Rhythm Control Strategy in the Acute Care Setting?

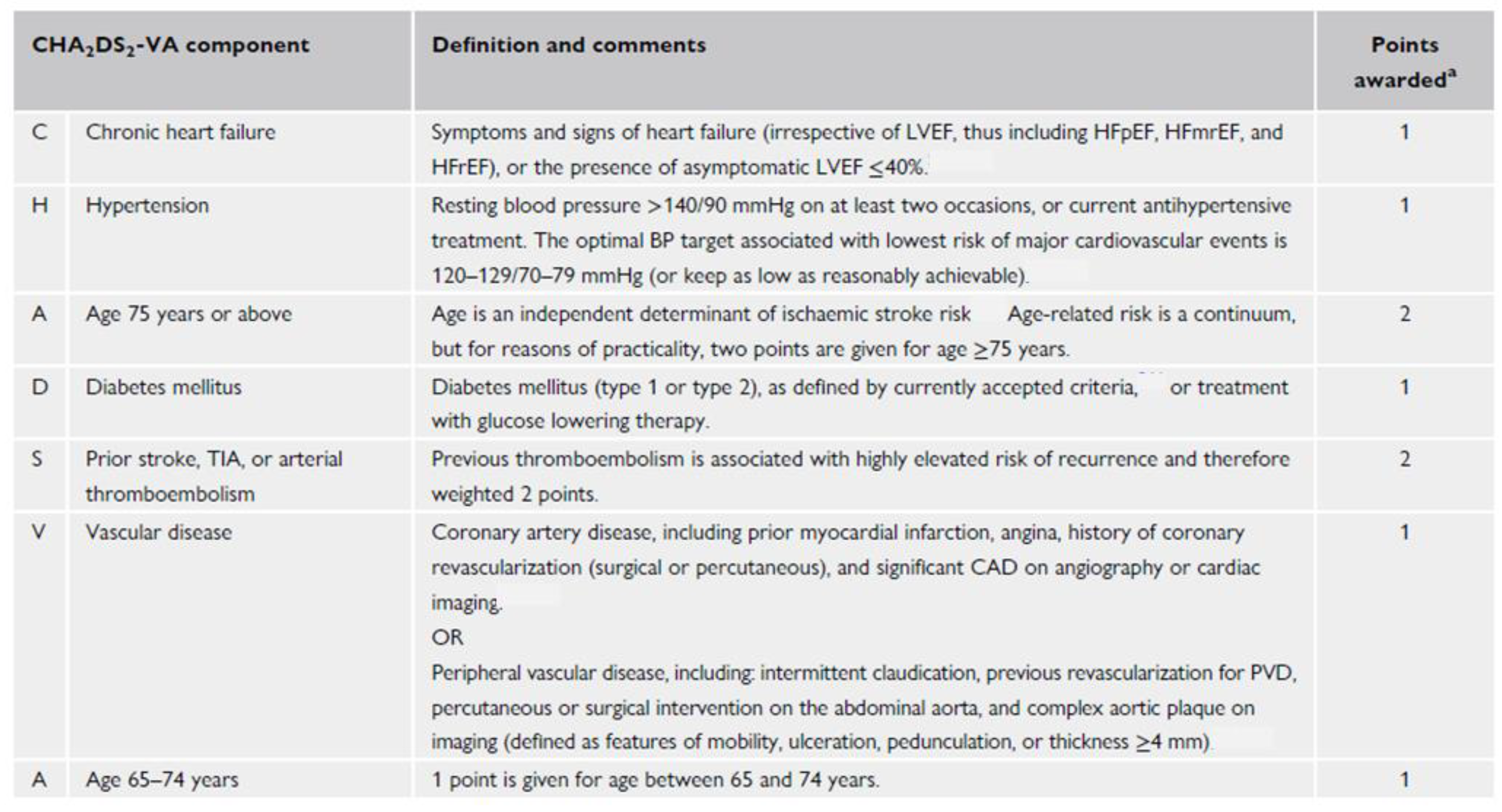

Prevention of Thromboembolic Events

Future Directions

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Echahidi, N.; Pibarot, P.; O’Hara, G.; Mathieu, P. Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008, 51, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillinov, A.M.; Bagiella, E.; Moskowitz, A.J.; et al. Rate control versus rhythm control for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2016, 374, 1911–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudino, M.; Di Franco, A.; Rong, L.Q.; Piccini, J.; Mack, M. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: from mechanisms to treatment. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 1020–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.; Slama, M.; Lakbar, I.; et al. Landiolol for treatment of new-onset atrial fibrillation in critical care: A systematic review. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, J.P.; Fontes, M.L.; Tudor, IC; et al. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA 2004, 291, 1720–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villareal, R.P.; Hariharan, R.; Liu, B.C.; et al. Postoperative atrial fibrillation and mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004, 43, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrev, D.; Aguilar, M.; Heijman, J.; Guichard, J.B.; Nattel, S. Postoperative atrial fibrillation: mechanisms, manifestations and management. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conen, D.; Wang, M.K.; Devereaux, PJ; et al. New-onset perioperative atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting and long-term risk of adverse events: an analysis from the coronary trial. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e020426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.K.; Meyre, P.B.; Heo, R.; et al. Short-term and long-term risk of stroke in patients with perioperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. CJC Open 2021, 4, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staerk, L.; Sherer, J.A.; Ko, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Helm, R.H. Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes. Circ Res 2017, 120, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, R.; Caputo, M.; Calori, G.; Lloyd, C.T.; Underwood, M.J.; Angelini, G.D. Predictors of atrial fibrillation after conventional and beating heart coronary surgery: A prospective, randomized study. Circulation 2000, 102, 1530–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, K.; Kimura, F.; Imamaki, M.; et al. Relation of inflammatory cytokines to atrial fibrillation after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006, 29, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.K.; Laurikka, J.; Vikman, S.; Nieminen, R.; Moilanen, E.; Tarkka, M.R. Postoperative interleukin-8 levels related to atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. World J Surg 2008, 32, 2643–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccini, J.P.; Zhao, Y.; Steinberg, B.A.; et al. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for prevention of atrial fibrillation following coronary artery bypass surgery. Am J Cardiol 2013, 112, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesen, B.; Nijs, J.; Maessen, J.; Allessie, M.; Schotten, U. Post-operative atrial fibrillation: a maze of mechanisms. Europace 2012, 14, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kang, D.R.; Uhm, J.S.; Shim, J.; et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation predicts long-term newly developed atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft. Am Heart J 2014, 167, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantino, Y.; Zelnik Yovel, D.; Friger, M.D.; Sahar, G.; Knyazer, B.; Amit, G. Postoperative atrial fibrillation following artery bypass graft surgery predicts long-term atrial fibrillation and stroke. Isr Med Assoc J 2016, 18, 744–748. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, L.B.; Crystal, E.; Heilbron, B.; Page, P. Atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol 2005, 21 Suppl. B, 45B–50B. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuster, V.; Ryden, L.E.; Cannom, D.S.; et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for practice guidelines. Circulation 2006, 114, e257–e354. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, S.G. Atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. Ann Card Anesth 2010, 13, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, V.; Ryden, L.E.; Cannom, D.S.; et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2011, 123, e269–e367. [Google Scholar]

- Providencia, R.; Kukendra-Rajah, K.; Barra, S. Amiodarone for atrial fibrillation: a dead man walking? Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, E.G.; Strickberger, S.A.; Man, K.C.; et al. Preoperative amiodarone as prophylaxis against atrial fibrillation after heart surgery. N Engl J Med 1997, 337, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagdi, T.; Nalbantgil, S.; Ayik, F.; et al. Amiodarone reduces the incidence of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003, 125, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, J.; Weber, T.; Berent, R.; et al. A comparison between oral antiarrhythmic drugs in the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: the pilot study of prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation (SPPAF), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am Heart J 2004, 147, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, M.S.; Nolan, P.E.; Slack, M.K.; Tisdale, J.E.; Hilleman, D.E.; Copeland, J.G. Amiodarone prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: meta-analysis of dose response and timing of initiation. Pharmacotherapy 2007, 27, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiadinso, I.; Meshkov, A.B.; Gaughan, J.; et al. Atrial arrhythmias after lung and heart-lung transplant: Effects on short-term mortality and the influence of amiodarone. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011, 30, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vanErven, L.; Schalij, M.J. Amiodarone: an effective antiarrhythmic drug with unusual side effects. Heart 2010, 96, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlschlegel, J.D.; Burrage, P.S.; Ngai, J.Y.; et al. Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists/European Association of Cardiothoracic Anaesthetists practice advisory for the management of perioperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2019, 128, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couffignal, C.; Amour, J.; Ait-Hamou, N.; et al. Timing of beta-blocker reintroduction and the occurrence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a prospective cohort study. Anesthesiology 2020, 132, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blessberger, H.; Lewis, S.R.; Pritchard, M.W.; et al. Perioperative beta-blockers for preventing surgery-related mortality and morbidity in adults undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 9, CD-13438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellahi, J.L.; Heringlake, M.; Knotzer, J.; Fornier, W.; Cazenave, L.; Guarracino, F. Landiolol for managing atrial fibrillation in post-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J Suppl 2018, 20, A4–A9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafaro, T.; Allwood, M.; McIntyre, W.F.; et al. Landiolol for the prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anesth 2023, 70, 1828–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminohara, J.; Hara, M.; Uehara, K.; Suruga, M.; Yunoki, K.; Takatori, M. Intravenous landiolol for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after aortic root, ascending aorta, and aortic arch surgery: A propensity score-matched analysis. JTCVS Open 2022, 11, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Sanna, T.; Ballman, K.V.; et al. Posterior left pericardiotomy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: an adaptive, single-centre, single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 2075–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, A.; Hafez, A.H.; Elaraby, A.; et al. Posterior pericardiotomy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EuroIntervention 2023, 19, e305–e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.; Burrage, P.S.; Ngai, J.Y.; et al. Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists/European Association of Cardiothoracic Anaesthetists practice advisory for the management of perioperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2019, 33, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccini, J.P.; Ahlsson, A.; Dorian, P.; et al. Design and rationale of a phase 2 study of NeurOtoxin (Botulinum toxin type A) for the prevention of postoperative atrial fibrillation – the NOVA study. Am Heart J 2022, 245, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J.; Ross-White, A.; Sibley, S. Magnesium prophylaxis of new-onset atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos One 2023, 18, e029274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.; Campbell, N.G.; Allen, E.; et al. Potassium supplementation and prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA 2024, 332, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conen, D.; Wang, M.; Popova, E.; et al. Effect of colchicine on perioperative atrial fibrillation and myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery in patients undergoing major thoracic surgery (COP-AF): an international randomized trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.; Fleischmann, K.E.; Smilowitz, N.R.; et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/ACS/ASNC/HRS/SCA/SCCT/SCMR/SVM Guideline for perioperative cardiovascular management for noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 84, 1869–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisdale, J.E.; Padhi, I.D.; Goldberg, A.D.; et al. A randomized, double-blind comparison of intravenous diltiazem and digoxin for atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery. Am Heart J 1998, 135, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siu, C.W.; Lau, C.P.; Lee, W.L.; Lam, K.F.; Tse, H.F. Intravenous diltiazem is superior to intravenous amiodarone or digoxin for achieving ventricular rate control in patients with acute uncomplicated atrial fibrillation. Crit Care Med 2009, 37, 2174–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermeyer, F.X.; Grafstein, E.; Stenstrom, R.; et al. Safety and efficiency of calcium channel blockers versus beta-blockers for rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation and no acute underlying medical illness. Acad Emerg Med 2013, 20, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrett, M.; Gohil, N.; Tica, O.; Bunting, K.V.; Kotecha, D. Efficacy and safety of intravenous beta-blockers in acute atrial fibrillation and flutter is dependent on beta-1 selectivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin Res Cardiol 2023, 113, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, A.E.; Dimarco, J.P. Management of atrial fibrillation in patients with structural heart disease. Circulation 2012, 125, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Kamel, H.; Singer, D.E.; Wu, Y.L.; Lee, M. Perioperative/postoperative atrial fibrillation and risk of subsequent strokeand/or mortality. Stroke 2019, 50, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.; Nielsen, S.J.; Bergfeldt, L.; et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass grafting and long-term outcome: a population-based nationwide from the SWEDEHEART registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2021, 10, e017966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, I.A.; Magalhaes, A.; Lima da Silva, G.; et al. Anticoagulation therapy in patients with post-operative atrial fibrillation: systematic review with meta-analysis. Vascul Pharmacol 2022, 142, 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, E.; Guinot, P.G.; Rozec, B.; et al. Comparison of landiolol and amiodarone for the treatment of new-onset atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery (FAAC) trial: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2023, 24, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornier, W.; Jacquet-Lagreze, M.; Coolenot, T.; et al. Microvascular effects of intravenous esmolol in patients with normal cardiac function undergoing postoperative atrial fibrillation: a prospective pilot study in cardiothoracic surgery. Crit Care 2017, 21, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacheron, C.H.; Allaouchiche, B. Illustration of the loss of haemodynamic coherence during atrial fibrillation using urethral photoplethysmography. BMJ Case Rep 2019, 12, e230757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, M.C.; Degiovanni, A.; Grisafi, L.; et al. Left atrial strain to predict postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging 2024, 17, e015969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, M.; Contreras, N.; Ramakrishna, S.; Zimmerman, J.M.; Varghese Jr, T.K.; Mitzman, B. Preoperative atrial deformation indices predict postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing lung resection surgery. Echocardiography 2025, 42, e70105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).