Submitted:

01 August 2025

Posted:

04 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

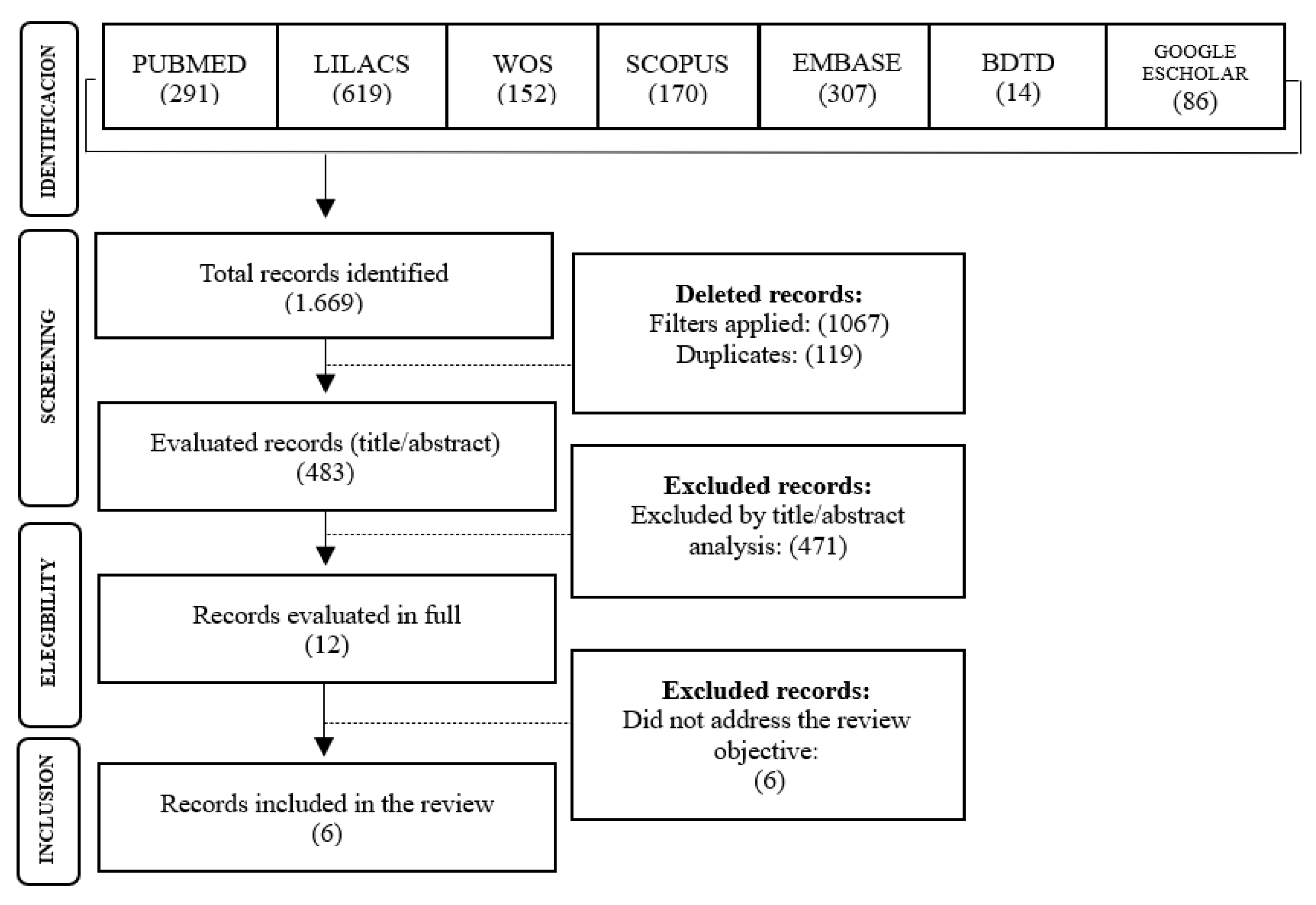

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| PTB | Pulmonary Tuberculosis |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global tuberculosis report 2024: TB disease burden – 1.1 TB incidence [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024/tb-disease-burden/1-1-tb-incidence (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Tuberculose. Portal da Saúde, 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/t/tuberculose (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Hussein MT, Youssef LM, Abusedera MA. Pattern of pulmonar tuberculosis in elderly patients in Sohag Governorate: hospital based study. Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis, Cairo 2013, 62, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Situação epidemiológica da tuberculose. Power BI, 2024. Available online: https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMGI0YTk1MTMtNWM5ZS00MGI0LWI2NjgtZGI3OWMxNmVlOTgxIiwidCI6IjlhNTU0YWQzLWI1MmItNDg2Mi1hMzZmLTg0ZDg5MWU1YzcwNSJ9 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Andrade SLE, Rodrigues DCS, Barreto AJR, et al. Tuberculose em pessoas idosas: porta de entrada do sistema de saúde e o diagnóstico tardio. Rev enferm UER 2016, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. j. soc. res. methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968, 70, 213–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

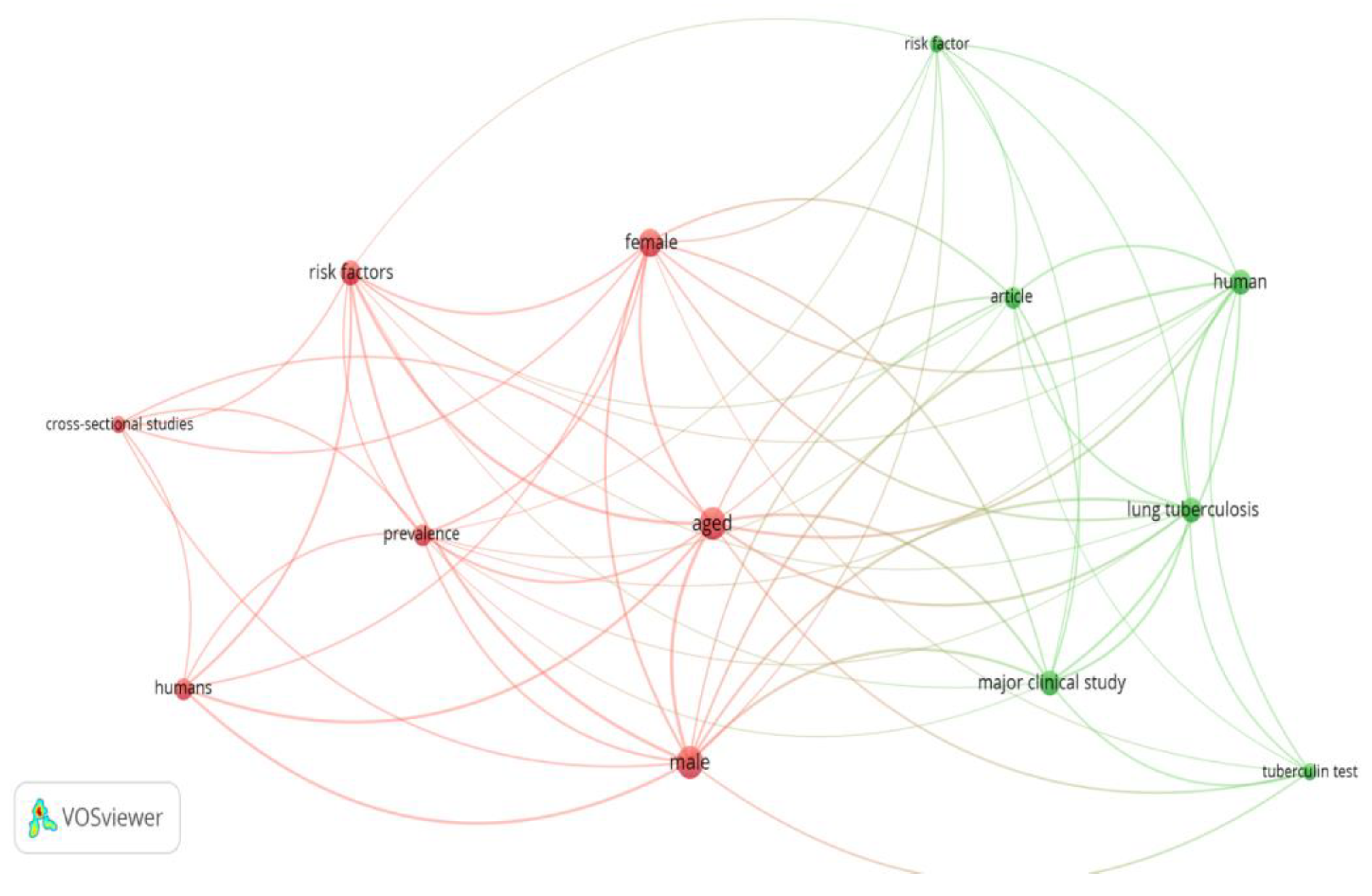

- Radtke Caneppele N, Belintani Shigaki H, Ramos HR, Ribeiro I. The use of VOSviewer software in Scientific Research. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estratégia 22, e24970.

- Lin YH, Chen CP, Chen PY, et al. Screening for pulmonary tuberculosis in type 2 diabetes elderly: a cross-sectional study in a community hospital. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang CY, Zhao F, Xia YY, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of active pulmonary tuberculosis among elderly people in China: a population based cross-sectional study. Infect Dis Poverty 2019, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves EC, Carneiro ICRS, Santos MIPO, et al. Aspectos epidemiológicos, clínicos e evolutivos da tuberculose em idosos de um hospital universitário em Belém, Pará. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. Rio de Janeiro 2017, 20, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Freire ILS, Santos FR, Menezes LCC, et al. Aspectos da tuberculose em idosos. Acta Scientiarum. Ciências da Saúde 2018, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, JC. História clínica e epidemiológica de pacientes idosos diagnosticados com tuberculose. [dissertação] UNIFOR, 2017. Available online: https://biblioteca.sophia.com.br/terminalri/9575/acervo/detalhe/113685 (accessed on 1 abr. 2025).

- Feng Y, Guo J, Luo S, Zhang Z, Liu Z. A Study on Risk Factors for Readmission of Elderly Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis Within One Month Using Propensity Score Matching Method. Infect Drug Resist 2024, 17, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama K, Chiang CY, Enarson DA, et al. Tobacco and tuberculosis: a qualitative systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2007, 11, 1049–61. [Google Scholar]

- Lin HH, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution, and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2007, 4, e20. [Google Scholar]

- van Zyl Smit RN, Pai M, Yew WW, et al. Global lung health: the colliding epidemics of tuberculosis, tobacco smoking, HIV and COPD. Eur Respir J 2010, 35, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang H, Chen X, Lv J, et al. Prospective cohort study on tuberculosis incidence and risk factors in the elderly population of eastern China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton KC, MacPherson P, Houben RMGJ, et al. Sex differences in tuberculosis burden and notifications in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2016, 13, e1002119. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas e Estratégicas. Política Nacional de Atenção Integral à Saúde do Homem. Brasília, 2008. Available online: http://www.unfpa.org.br/Arquivos/saude_do_homem.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Figueiredo, W. Assistência à saúde dos homens: um desafio para os serviços de atenção primária. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2005, 10, 105–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro RS, Viacava F, Travassos C, Brito AS. Gênero, morbidade, acesso e utilização de serviços de saúde no Brasil. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2002, 7, 687–7070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis and diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Adobe Acrobat document, 2p.]. Available online: http:// www.who.int/tb/publications/diabetes_tb.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Bodke H, Wagh V, Kakar G. Diabetes Mellitus and Prevalence of Other Comorbid Conditions: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e49374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workneh MH, Bjune GA, Yimer SA. Prevalence and associated factors of tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus comorbidity: A systematic review. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0175925. [Google Scholar]

- Meng-Shiuan H, Tzu-Chien C, Ping-Huai W, et al. Revisiting the association between vitamin D deficiency and active tuberculosis: A prospective case-control study in Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2024, 57, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra MC, Appleton SC, Franke MF, et al. Tuberculosis burden in households of patients with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011, 377, 147–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpatla S, Sekar A, Achanta S, et al. Características de pacientes com diabetes rastreados para tuberculose em um hospital de cuidados terciários no sul da Índia. Public Health Action 2013, 3, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Santos MAPS, Albuquerque MFPM, Ximenes RAA, et al. Risk factors for treatment delay in pulmonary tuberculosis in Recife, Brazil. BMC Public Health 2005, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla S, You P, Aifah A, et al. Identifying risk factors associated with smear positivity of pulmonary tuberculosis in Kazakhstan. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0172942. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske CT, Hamilton CD, Stout JE. Alcohol use and clinical manifestations of tuberculosis. J Infect 2009, 58, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye X, Su X, Shi J, et al. Incidence, causes, and risk factors for unplanned readmission in patients admitted with pulmonary tuberculosis in China. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2023, 17, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search key/Search string |

|---|---|

| PUBMED | ("Tuberculosis, Pulmonary"[mh] OR "Tuberculosis, Pulmonary"[tiab] OR "Consumption*, Pulmonary"[tiab] OR "Pulmonary Consumption*"[tiab] OR "Pulmonary Phthisis"[tiab] OR "Phthises, Pulmonary"[tiab] OR "Phthisis, Pulmonary"[tiab] OR "lung tuberculosis"[tiab] OR "chronic pulmonary tuberculosis"[tiab] OR "chronic tuberculosis, lung"[tiab] OR "lung TB"[tiab] OR "pulmonary TB"[tiab] OR "tuberculous bronchitis"[tiab] OR "lung tuberculosis"[tiab]) AND ("elderly person"[tiab] OR Elder*[tiab] OR "old age"[tiab] OR "older people"[tiab] OR "aged people"[tiab] OR "oldest people"[ tiab] OR "older adult*"[tiab] OR senium[tiab] OR "aged people"[tiab] OR "old adult*"[tiab] OR "oldest adult*"[tiab] OR "older person*"[tiab] OR "old person*"[tiab] OR "older patient*"[tiab] OR "oldest patient*"[tiab] OR "geriatric patient"[tiab]) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY=("Tuberculosis, Pulmonary" OR "Tuberculosis, Pulmonary" OR "Consumption*, Pulmonary" OR "Pulmonary Consumption*" OR "Pulmonary Phthisis" OR "Phthises, Pulmonary" OR "Phthisis, Pulmonary" OR "lung tuberculosis" OR "chronic pulmonary tuberculosis" OR "chronic tuberculosis, lung" OR "lung TB" OR "pulmonary TB" OR "tuberculous bronchitis" OR "lung tuberculosis") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY= ("elderly person" OR Elder* OR "old age" OR "older people" OR "aged people" OR "oldest people" OR "older adult*" OR senium OR "aged people" OR "old adult*" OR "oldest adult*" OR "older person*" OR "old person*" OR "older patient*" OR "oldest patient*" OR "geriatric patient") AND TITLE= ("Risk Factor*" OR "Population at Risk" OR "Risk Score*" OR "Risk Factor Score*" OR "Health Correlates" OR "Social Risk Factor*" OR "Factor, Social Risk" OR "Population at Risk" OR risk OR "relative risk" OR "risk hypothesis" OR "Risk Assessment" OR "risk analysis" OR "Analysis, Risk" OR "Assessment, Benefit-Risk" OR "Assessment, Health Risk" OR "Assessment, Risk" OR "Assessment, Risk-Benefit" OR "Assessments, Risk-Benefit" OR "Benefit Risk Assessment") |

| Embase | ('lung tuberculosis'/exp OR 'tuberculosis, pulmonary':ti,ab,kw OR 'consumption*, pulmonary':ti,ab,kw OR 'pulmonary consumption*':ti,ab,kw OR 'pulmonary phthisis':ti,ab,kw OR 'phthises, pulmonary':ti,ab,kw OR 'phthisis, pulmonary':ti,ab,kw OR 'lung tuberculosis':ti,ab,kw OR 'chronic pulmonary tuberculosis':ti,ab,kw OR 'chronic tuberculosis, lung':ti,ab,kw OR 'lung tb':ti,ab,kw OR 'pulmonary tb':ti,ab,kw OR 'tuberculous bronchitis':ti,ab,kw OR 'lung tuberculosis':ti,ab,kw) AND ('elderly person':ti,ab,kw OR 'elder*':ti,ab,kw OR 'old age':ti,ab,kw OR 'older people':ti,ab,kw OR 'aged people':ti,ab,kw OR 'oldest people':ti,ab,kw OR 'older adult*':ti,ab,kw OR 'senium':ti,ab,kw OR 'aged people':ti,ab,kw OR 'old adult*':ti,ab,kw OR 'oldest adult*':ti,ab,kw OR 'older person*':ti,ab,kw OR 'old person*':ti,ab,kw OR 'older patient*':ti,ab,kw OR 'oldest patient*':ti,ab,kw OR 'geriatric patient':ti,ab,kw) AND ('risk factor'/exp OR 'risk factor*':ti,ab,kw OR 'population at risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'risk score*':ti,ab,kw OR 'risk factor score*':ti,ab,kw OR 'health correlates':ti,ab,kw OR 'social risk factor*':ti,ab,kw OR 'factor, social risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'population at risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'risk'/exp OR 'risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'relative risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'risk hypothesis':ti,ab,kw OR 'risk assessment'/exp OR 'risk analysis':ti,ab,kw OR 'risk assessment':ti,ab,kw OR 'analysis, risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'assessment, benefit-risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'assessment, health risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'assessment, risk':ti,ab,kw OR 'assessment, risk-benefit':ti,ab,kw OR 'assessments, risk-benefit':ti,ab,kw OR 'benefit risk assessment':ti,ab,kw) |

| LILACS | (mj:"Tuberculose Pulmonar" OR ti:"Consumpção Pulmonar" OR ti:"Tuberculose do Pulmão" OR tw:"Tísica" OR tw:"Tísica Pulmona" OR tw:"Tuberculosis, Pulmonary" OR tw:"Tuberculosis Pulmonar" tw:"Tuberculosis, Pulmonary" OR tw:"Consumption*, Pulmonary" OR tw:"Pulmonary Consumption*" OR tw:"Pulmonary Phthisis" OR tw:"Phthises, Pulmonary" OR tw:"Phthisis, Pulmonary" OR ti:"lung tuberculosis" OR tw:"chronic pulmonary tuberculosis" OR tw:"chronic tuberculosis, lung" OR tw:"lung TB" OR tw:"pulmonary TB" OR tw:"tuberculous bronchitis" OR tw:"lung tuberculosis") AND (mj:idoso OR ti:idoso* OR ti:anciano OR ti:"pessoa idosa" OR tw:"Pessoas de Idade" OR tw:"elderly person" OR ti:Elder* OR tw:"old age" OR tw:"older people" OR tw:"aged people" OR tw:"oldest people" OR tw:"older adult*" OR tw:senium OR tw:"aged people" OR tw:"old adult*" OR tw:"oldest adult*" OR tw:"older person*" OR ti:"old person*" OR tw:"older patient*" OR tw:"oldest patient*" OR ti:"geriatric patient") |

| Web Of Sciene | ("Tuberculosis, Pulmonary" OR "Tuberculosis, Pulmonary" OR "Consumption*, Pulmonary" OR "Pulmonary Consumption*" OR "Pulmonary Phthisis" OR "Phthises, Pulmonary" OR "Phthisis, Pulmonary" OR "lung tuberculosis" OR "chronic pulmonary tuberculosis" OR "chronic tuberculosis, lung" OR "lung TB" OR "pulmonary TB" OR "tuberculous bronchitis" OR "lung tuberculosis") AND ("elderly person" OR Elder* OR "old age" OR "older people" OR "aged people" OR "oldest people" OR "older adult*" OR senium OR "aged people" OR "old adult*" OR "oldest adult*" OR "older person*" OR "old person*" OR "older patient*" OR "oldest patient*" OR "geriatric patient") (Topic) |

| Google Scholar | ("Tuberculosis, Pulmonary" OR "lung tuberculosis" OR "chronic pulmonary tuberculosis") AND (elderly OR aged OR "old age" OR "aged people" OR "older patient*" OR "old adult") |

| BDTD CAPES | Idoso AND tuberculose pulmonar |

| Study | Article title | Reference | Place/year | Periodical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Screening for pulmonary tuberculosis in type 2 diabetes elderly: a cross-sectional study in a community hospital. | Lin YH, Chen CP, Chen PY, et al. [9] | China, 2015 | BMC public health |

| S2 | Prevalence and risk factors of active pulmonary tuberculosis among elderly people in China: a population based cross-sectional study. | Zhang CY, Zhao F, Xia YY, et al. [10] | China, 2017 | Infectious diseases of poverty (BMC) |

| S3 | Aspectos epidemiológicos, clínicos e evolutivos da tuberculose em idosos de um hospital universitário de belém, Pará | Chaves EC, et al. [11] | Brazil, 2017 | Rev. Brasileira de Gerontologia |

| S4 | Aspects of tuberculosis in the elderly | Freire ILS, et al. [12] | Brazil, 2018 | Acta Scientiarum. Health Sciences |

| S5 | História clínica e epidemiológica de pacientes idosos diagnosticados com tuberculose | Vasconcelos JC. [13] | Brazil, 2017 | BDTB |

| S6 | A Study on Risk Factors for Readmission of Elderly Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis Within One Month Using Propensity Score Matching Method | Feng Y, Guo J, Luo S, Zhang Z, Liu Z. [14] | China, 2024 | Infection and Drug Resistance |

| Study | Objective | Study Design | Research Question | Population (Sample Size) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | To actively screen high-risk elderly diabetic patients and identify TB prevalence and its determinants. | Single-center cross-sectional study | Not specified | A total of 3,087 patients with type 2 diabetes aged >65 years (2,141 hospital-based and 946 community-based) participated in the screening program. | Male sex, smoking, liver cirrhosis, and self-reported weight loss were significantly associated with increased TB risk. Independent risk factors included weight loss, cirrhosis, and smoking history. Among the 73 patients with active TB or TB history, they were more likely to be male, have lower BMI, greater alcohol consumption, a family history of TB, higher LDL levels, and less hypertension. No significant difference was found in HbA1c levels between groups. |

| S2 | To determine the prevalence and identify TB risk factors among older adults in order to develop a screening algorithm for this high-risk population in China. | Cross-sectional cluster sampling study | Not specified | Sample size was estimated using a formula for population proportion (p = 369/100,000, CI = 95%, error = 0.2), resulting in a required sample of 33,192 (allowing 10% non-response). | Of 38,888 eligible individuals from 27 clusters, 34,269 completed the questionnaire and physical exam. There were 193 active PTB cases, 62 bacteriologically confirmed. Estimated prevalence of active and confirmed PTB in those aged ≥65 was 563.19 per 100,000. Risk factors: male sex, older age, rural residence, low weight, diabetes, close contact with TB cases, and prior TB history. TB risk increased with age and decreased BMI in a dose-response pattern. |

| S3 | To evaluate the epidemiological, clinical, and outcome aspects of TB in older adults at a university hospital in Belém, Pará. | Cross-sectional study | Not specified | 82 medical records reviewed. | Most patients were male (64.6%), aged 60–69 years, with new TB cases (95.1%), primarily pulmonary form (75.6%), and comorbidities (69.5%). Hospital stays exceeded 21 days. Common symptoms: fever (67.1%), dyspnea (64.6%), weight loss (61.0%), productive cough (59.8%), chest pain (51.2%). Adverse effects occurred in 50% of patients, mostly gastrointestinal (70.7%). Cure rate: 59.8%; TB-related mortality was high (15.9%). Significant associations: age group (p = 0.017), hospitalization time (p = 0.000), and adverse reaction (p = 0.018). |

| S4 | To describe the clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects of TB in older adults. | Exploratory descriptive cross-sectional study with a quantitative approach | What are the clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects of TB in older adults treated in a health district in Natal/RN? | 94 participants aged 60–69 years. | Most participants were male (51.1%), aged 60–69. Pulmonary TB was predominant (86.2%), and most were new cases (59.6%). Treatment was self-administered (52.1%) and completed on time (57.4%). Tuberculin skin test was not performed in 76.6%, nor histopathology in 86.2%; however, chest radiography suggested TB in 72.3%. First sputum smear was not performed in 59.5%; of those tested with a second smear, 54.2% were positive. HIV testing was not performed in 54.2% of patients. |

| S5 | To study the clinical and epidemiological history of elderly TB patients in the state of Ceará. | Retrospective, documentary, quantitative, and analytical study | Not specified | 128 medical records reviewed. Patient ages ranged from 60 to 93 (mean = 68.84; variance = 52.21; SD = 7.22). | Pulmonary TB was the most common form (102; 79.69%). Smoking was the most prevalent risk factor (63; 49.22%), followed by alcohol use, HIV/AIDS, malnutrition, diabetes, and COPD. Causal links were established between these factors and mortality. Of the patients, 62 (48.44%) were discharged improved, 9 (7.03%) were transferred, and 57 (44.53%) died. Among deaths, 43 (47.78%) were male. Key symptoms: fever, dyspnea, productive cough, and weight loss. Most patients were male (70.31%), aged 60–69 (62.5%), and 46.09% had income above one minimum wage. Those with no education or incomplete elementary education were most affected. |

| S6 | To explore risk factors for readmission of elderly PTB patients within one month using propensity score matching (PSM). | Clinical study | What are the risk factors for readmission of elderly PTB patients one month after discharge? | Of 1,360 hospitalized elderly PTB patients, 36 had incomplete data, 40 were readmitted for unrelated reasons, and 16 died, leaving 1,268 for analysis. | After matching, no significant differences were found between groups in sex, age, occupation, BMI, or medical history (all p > 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression identified infection, drug-induced liver injury (DILI), acute heart failure (AHF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) as significant risk factors for readmission. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).