1. Introduction

The global energy and waste landscapes are undergoing a fundamental transformation. With increasing pressures from climate change, fossil fuel depletion, and resource-intensive consumption patterns, sustainability has become not just an environmental necessity but an operational imperative. Among the pressing challenges is the efficient management of biomass waste—particularly food waste—which comprises a significant share of municipal and institutional waste worldwide. The food system alone accounts for nearly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and nearly 30% of all food produced is discarded [

1,

2,

3]. Against this backdrop, the valorization of food waste into value-added products presents a viable pathway to achieving climate goals and circular economy targets [

4,

5,

6].

In the last decade, the concept of a circular bioeconomy has gained momentum. It refers to a regenerative system in which biomass resources are sustainably converted into energy, materials, and products through biological and renewable processes [

7,

8]. Recent work by Pal et al. [

2] and Razouk et al. [

3] emphasized the need to integrate waste valorization with local food systems, especially in institutional and urban settings. These models aim to recapture the energy, nutrients, and carbon embedded in organic waste and reintegrate them into productive cycles.

The emerging trend of converting food waste into animal feed and compost offers multiple co-benefits: reduced landfilling, minimized methane emissions, and the generation of renewable soil amendments [

4,

9]. According to Xu et al. [

5], bioconversion of food waste through microbial fermentation or enzymatic hydrolysis can achieve material recovery rates exceeding 70%, depending on feedstock consistency and process temperature. Other studies have shown that compost derived from food waste improves soil structure, microbial activity, and water retention, leading to yield gains in organic agriculture [

10,

11].

Despite these advances, the application of biomass valorization technologies in institutional environments—especially universities—remains limited. While several pilot-scale studies have evaluated composting systems [

12], biodigesters [

13], or black soldier fly larvae systems [

14], very few have assessed integrated models that process cooked and uncooked food residues into multiple outputs such as compost and pet food. Moreover, most implementations have been energy-intensive and lacked integration with renewable energy infrastructure, thereby reducing their net sustainability benefits [

15,

16].

In recent years, solar photovoltaic (PV) systems have emerged as the preferred clean energy technology for distributed applications. The declining costs of PV modules, combined with their scalability and low maintenance, have led to widespread adoption in public and private institutions [

17,

18,

19]. Solar energy integration in biomass processing systems enables decentralization and decarbonization of organic waste management, particularly in off-grid or semi-urban environments [

20,

21].

However, as Vasileiadou [

8] and Rifna et al. [

9] noted, the convergence of solar energy with food waste valorization technologies has largely been conceptual rather than operational. Most studies have focused on PV-powered drying systems for food preservation or solar thermal units for sterilization. A comprehensive model that combines real-time solar energy use with biomass transformation into edible or agronomic products has yet to be tested on a campus scale. Moreover, detailed performance assessments—including conversion efficiency, CO₂ offsets, and energy-to-output ratios—are largely missing from the literature.

Another crucial challenge in deploying biomass-solar infrastructures in public settings is financial viability. Public institutions, especially in developing countries, often lack upfront capital for sustainability projects. To address this, energy performance contracting (EPC) has gained attention as a financing mechanism that enables third-party investment in energy systems, with repayments linked to measured savings [

22,

23,

24]. Zakaria et al. [

22] highlighted the risk allocation benefits of EPCs, while Niemiec et al. [

23] demonstrated that EPCs can reduce project payback times by 30–40% compared to conventional procurement in renewable energy investments.

Nevertheless, almost all EPC applications reported in the literature relate to lighting retrofits, HVAC upgrades, or building insulation improvements. Their application in biomass valorization or solar-waste hybrid systems remains virtually unexplored. The lack of empirical data from such systems inhibits replication and policy uptake [

24,

25,

26].

To respond to these challenges, this paper presents a case study from Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University (ALKU) in Turkey, which has implemented an integrated system for food waste conversion powered entirely by solar energy. The project is the first in Turkey to link a 1.7 MW rooftop PV system—commissioned under an EPC model—with a food waste processing unit (EcoAir-150), enabling decentralized production of compost and pet food from campus cafeteria residues. Over 12 months, empirical data was collected on feedstock inputs, device run times, energy consumption, conversion rates, and output volumes.

The ALKU case represents a pioneering effort in academic sustainability. It is not only technically distinctive but also financially self-sustaining and replicable. The integration of circular waste management, renewable energy, and performance-based financing in a campus context sets this model apart from prior approaches [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Furthermore, this paper aims to close the knowledge gap by providing detailed quantitative data, including a life-cycle-based CO₂ savings analysis, an energy efficiency assessment, and an economic feasibility projection.

While the bioconversion of biomass waste is theoretically well-understood, practical implementations on campus grounds remain rare and fragmented. These stems not only from infrastructural constraints but also from a lack of systemic models that incorporate food waste recovery into educational, environmental, and economic functions of higher education institutions. Nevertheless, various technologies have emerged across disciplines with potential for localized application in academic settings.

Among the most studied biomass valorization technologies is anaerobic digestion, which involves microbial breakdown of organic matter in oxygen-free environments to produce biogas and digestate. Anaerobic systems are commonly applied in municipal solid waste treatment and large-scale agriculture but are limited on campuses due to high water content requirements, odor management, and digester start-up time [

31,

32]. Additionally, these systems typically require continuous operation and large feedstock volumes, making them less suitable for university-scale food waste that is often variable in composition and sporadic in generation [

33].

Aerobic composting, by contrast, is more widely used in institutional settings because it allows batch processing of heterogeneous organic matter with lower technical complexity. Vasileiadou [

8] and Xu et al. [

5] reported pilot projects in Europe and China where food scraps, coffee grounds, and garden clippings were successfully composted within six to eight weeks under controlled conditions. However, energy consumption for aeration and temperature stabilization remains a barrier to climate-neutral operation unless supplemented by renewable sources [

9,

34].

In parallel, the use of black soldier fly (BSF) larvae in food waste processing has attracted interest due to its high protein yield and short life cycle [

14]. BSF systems have been piloted in research campuses in Southeast Asia to convert leftover rice, vegetables, and bread into animal feed. Nevertheless, they pose operational limitations such as temperature sensitivity and the need for pathogen control, particularly when handling post-consumer waste from institutional cafeterias [

35,

36,

37].

Emerging thermal technologies, such as pyrolysis and gasification, offer faster decomposition of biomass and the ability to produce biochar, syngas, and bio-oils. These have been proposed for use in closed-loop university systems but remain mostly theoretical due to high capital costs and regulatory uncertainties [

38,

39]. Additionally, their compatibility with solar PV systems is limited since they require high and stable thermal inputs not easily derived from intermittent energy sources.

While the technologies above demonstrate theoretical promise, most campus applications lack integration with solar energy systems. The reveals isolated efforts to co-locate PV arrays with composting units or biodigesters, yet these projects often lack literature empirical evaluation of their energy-productivity relationships [

20,

21,

40]. As a result, the environmental benefits of using renewable energy in food waste conversion remain largely anecdotal, hindering wider adoption and policy support.

Moreover, cross-sectional studies assessing multiple sustainability dimensions—such as waste diversion rates, energy balance, and educational impact—are exceedingly rare. Most campus sustainability reports focus on energy savings from retrofits (eg, LED lighting, smart thermostats) rather than material recovery outcomes. This fragmented view results in an underestimation of the systemic potential for campuses to become living laboratories for circular economy interventions [

6,

26,

41].

In Türkiye, the application of biomass valorization and renewable energy in university settings is even less documented. Most renewable installations have been grid-connected PV systems used primarily for offsetting electricity bills in administrative buildings. Composting units, where present, are often standalone and manually operated, producing inconsistent outputs due to irregular feeding and lack of moisture or pH control [

42]. Additionally, no published examples to date have demonstrated the transformation of cafeteria food waste into animal feed using mechanized bioreactors within EPC-supported solar frameworks.

Against this landscape, the ALKU case study presented in this article introduces a practical and scalable innovation. By linking a 150-liter EcoAir-150 biomass conversion unit with a 1.7 MW rooftop solar PV system—developed under Turkey's first public-sector Energy Performance Contract—the university implemented a decentralized and self-powered waste processing model. The system processed post-consumer food waste collected from a daily cafeteria service of approximately 1000–1200 students, offering direct material recovery and real-time energy consumption tracking.

Throughout the 12-month operation period, the system handled a cumulative 3.1 metric tons of input biomass, resulting in 2.1 tons of pet food and 0.94 tons of compost. Energy requirements were fully met by solar power, yielding an effective net-zero carbon operational profile. In contrast to anaerobic or thermochemical systems, the EcoAir-150 enabled rapid batch processing (average 18–26 hours per cycle) and required minimal operator training—both of which are critical success factors for public universities with constrained staff capacity [

15,

43].

Furthermore, the integration of this system with academic curricula enabled experiential learning for students in environmental engineering, nutrition, and renewable energy management. Monthly reports were used in undergraduate energy auditing courses, while compost and pet food outputs were employed in campus landscaping and outreach programs for local animal shelters, respectively. These multi-functional outputs amplify the value proposition of campus-based bioconversion units and offer tangible evidence of sustainability-in-action.

In summary, this segment of the literature indicates that although diverse food waste technologies exist, very few models offer technical feasibility, financial accessibility, educational integration, and climate alignment in a single system. By situating the ALKU pilot within this context, the study addresses long-standing limitations in scope, methodology, and replicability across the existing research base. The next section will elaborate on the methodology used in measuring these outcomes and evaluating their contribution to low-carbon, circular campus systems.

The increasing recognition of sustainability imperatives have positioned universities as innovation hubs for circular economy practices. However, few institutions have succeeded in translating theoretical sustainability principles into operational realities. Recent works have underscored that achieving system-wide transformation requires integrating multiple resource loops—energy, materials, food, and finance—into coherent models that are locally adaptable and technically viable [

49,

50]. The ALKU case, introduced in this study, represents one of the few documented instances where such integration has been operationalized through a public-sector energy performance contract (EPC), with full alignment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and national net-zero targets.

Biomass waste, particularly food waste, represents a high-potential input stream for bio-based production [

51,

52]. Yet, the transition from waste to economic or social value remains challenged by technological limitations, institutional inertia, and financial constraints. In response to this, Joshi et al. [

49] and Awasthi et al. [

51] have emphasized the role of waste-to-product strategies as part of sustainable urban metabolism. Their analyzes reveal that optimizing biomass conversion requires matching local feedstock characteristics with modular technologies—an approach mirrored in the ALKU deployment, which relies on menu-specific food residuals and device-specific processing cycles.

Higher education institutions, with their complex yet measurable operational environments, offer ideal test beds for developing, refining, and disseminating biomass valorization technologies [

53,

54]. Jayaprakash and Jagadeesan [

53] proposed a system-wide audit approach to quantify organic waste potential in Indian universities, but their model stopped short of implementing a full energy-integrated valorization chain. Similarly, studies conducted in European campuses have largely focused on segregated recycling or generic composting strategies, without linking such efforts to energy systems or academic learning [

55,

56,

57].

One of the main innovations presented by the ALKU case is the coupling of a solar-powered energy system with a food-to-product conversion unit, achieving autonomous, zero-emission operation. Over the course of the implementation, the device was operated on a batch-processing basis, using 150-liter input loads that reflected typical daily waste output from the cafeteria. Inputs included a diverse array of cooked and raw ingredients—such as vegetable peels, legumes, rice, pasta, and protein leftovers—classified under 31 unique menu-derived recipes. The yield from these recipes was measured over 12 months and aggregated to evaluate performance metrics, including conversion efficiency, energy consumption, operating time, and carbon offset.

In economic terms, the ALKU system demonstrated a return on investment within 2.7 years, calculated based on pet food market value, avoided waste disposal costs, and energy savings. Araújo et al. [

54] and Martini et al. [

50] noted that the financial viability of such systems often hinges on non-market values such as community engagement, educational outcomes, and reduced reliance on municipal waste services. The present case aligns with these insights, as both material and non-material benefits were recorded—ranging from free pet food provision for stray animals to student engagement in sustainability-themed coursework.

Furthermore, the use of EPC mechanisms allowed the system to be developed without direct capital expenditure from the university. EPCs have gained traction in building efficiency but remain novel in the domain of circular waste infrastructure. The integration of this financing model with renewable-powered biomass valorization makes the ALKU example a first of its kind in Türkiye and a rare case globally. According to Curado et al. [

54], this kind of layered infrastructure—combining energy, waste, and social systems—offers “metabolic coherence,” enhancing resilience while reducing institutional carbon footprints.

The replication potential of this model is high, especially in middle-income countries where public institutions often struggle to finance sustainability projects. By documenting the design, implementation, and performance monitoring of the system, this study contributes both theoretical and empirical evidence to support policy formulation in the higher education sector. This is further validated by studies such as Nunes et al. [

56] and Kharismadewi et al. [

50], who call for greater operational transparency and data-sharing from pilot systems to accelerate the adoption of bio-integrated infrastructure.

In terms of carbon impact, the ALKU system contributed to an annual reduction of 17.5 metric tons of CO₂ emissions, based on avoided methane from landfill and displaced fossil electricity use. This aligns with recent climate accounting frameworks proposed by UN Environment and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), where scope-1 and scope-2 emissions can be offset through on-site mitigation measures [

58]. Moreover, the system minimized water usage and eliminated the need for chemical additives, achieving a near-zero-waste production cycle.

From an educational standpoint, the system enabled live demonstrations, hands-on training, and student-led research, thus reinforcing the pedagogical value of sustainability infrastructure. This educational dimension echoes the calls made by Kumar et al. [

52] and others [

59,

60] to embed circular economy systems within the fabric of learning institutions, thereby producing not only environmental dividends but also knowledge capital.

In conclusion, this paper presents a pioneering case of solar-integrated biomass valorization, implemented through a public-sector energy performance contract on a university campus. It contributes to the existing literature by bridging the gap between waste recovery technologies and renewable energy systems in academic settings. The model's quantifiable outcomes—including pet food and compost production, carbon reduction, and financial returns—offer a template for other institutions seeking to embed sustainability into daily operations. The methodology used in this study encompasses direct field measurements, device-level energy monitoring, life-cycle emissions calculations, and scenario-based economic evaluation. The next section details these methods in full, outlining the experimental design, data collection instruments, and analytical tools used to derive the reported findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area: ALKU Campus and Ecosystem Definition

Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University (ALKU) is a campus ecosystem located in the Mediterranean climate zone on Türkiye's southern coast, with an average of 300 sunny days per year. This geographical advantage makes it an ideal environment for renewable energy projects. The ALKU Campus, where the study was conducted, has approximately 25,000 m² of active use area and a living center serving more than 5,000 students, staff, and visitors daily. The cafeteria system within this center operates with a daily meal production capacity of approximately 2,000 to 2,500 people.

2.1.1. Solar Energy Infrastructure

The 1.7 MW rooftop solar power plant (SPP), commissioned in 2023 on the ALKU Campus and a key component of this project, was established under the Energy Performance Contract (EPC) model, the first implemented in the public sector in Türkiye. This system consists of a total of 4,200 solar panels on the roofs of 17 different university buildings and generates approximately 2,800,000 kWh of electricity annually. This amount meets 60% of the campus's electricity needs and is used to neutralize carbon emissions, particularly in high-energy-consumption units like the cafeteria.

2.1.2. Dining Hall and Waste Ecosystem

ALKU Cafeteria provides an average of 2,000 meals daily, totaling approximately 285,000 meals annually. As a result of this large-scale food service operation, a significant amount of kitchen waste and food residue is generated. These wastes are systematically categorized into two main groups:

Organic kitchen waste – consisting of items such as vegetable and fruit peels, tea pulp, and other biodegradable materials, and Cooked food residue – including leftovers such as rice, bulgur, meat dishes, vegetable stews, pasta, and bread.

To manage this waste stream effectively, ALKU utilizes a semi-industrial processing unit named ECOAIR 150, which features a 150-liter chamber. This device enables two distinct valorization pathways: the production of compost from organic kitchen waste, and the production of pet food (primarily for cats and dogs) from cooked food leftovers. The processing duration ranges between 16 and 36 hours per batch, depending on the density and composition of the input material. Importantly, the ECOAIR 150 operates entirely on solar power sourced from the campus’s rooftop photovoltaic system, enabling a fully autonomous and zero-emission recycling process.

Table 1 summarizes the average monthly performance indicators of the ecocircular dining hall system powered by the ECOAIR 150 device. These metrics reflect the system’s capacity to convert food waste into valuable secondary products while achieving notable economic and environmental outcomes.

2.1.3. Ecosystem Integration

The project's standout feature is its integration of technical infrastructure with environmental and social sustainability. The compost produced is used in landscaping and agricultural practices on campus. Food production is used to feed stray animals and distribute free to students. This not only reduces waste but also provides social benefits.

The cafeteria system operates in integration with this transformation infrastructure; menus are digitally monitored, and waste types are classified daily. According to menu analysis, food waste contains approximately 35% animal protein and carbohydrate content, providing a suitable biomass for food production.

2.2. Recycling Technology: ECOAIR 150 Device

The ECOAIR 150, utilized in this study, is a semi-industrial-scale biochemical processing unit developed for sustainable food waste valorization. It has been actively used at ALKU Campus throughout 2024, operating on approximately 280 days, and has demonstrated both environmental and economic benefits.

This advanced device enables the dual-function conversion of (i) organic kitchen waste (such as vegetable peels, tea residues) into compost, and (ii) cooked food leftovers (such as rice, pasta, meat dishes) into dry pet food. Its operation is powered entirely by a 1.7 MW rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) system, making it part of a fully autonomous, zero-emission recycling process.

Technically, the ECOAIR 150 is equipped with a 150-liter hopper, processes each batch within 16 to 36 hours, and consumes approximately 6–14 kWh per cycle, depending on material density. It is semi-automated, with built-in control systems for temperature and humidity regulation, and is operated manually by a single trained staff member. These specifications enable the device to be both energy-efficient and operationally accessible, especially in institutional settings.

A summary of the device’s core technical specifications is provided in

Table 2, which highlights its capacity, energy profile, material compatibility, and automation features.

2.2.1. Application Protocol

The recycling process begins at the cafeteria exits, where waste is pre-separated into organic kitchen waste and cooked food leftovers. These materials are loaded into the ECOAIR 150 device twice daily, during morning and evening shifts. Based on the type of input material, the following conversion protocols are applied:

Vegetable and fruit peels are directed toward compost production, achieving an average yield of 10–15%,

Cooked food waste (such as rice, pasta, and meat-based dishes) is processed into dry pet food, with a conversion efficiency of 60–70%.

Throughout the year, the device’s performance was monitored on a monthly basis, measuring input volumes, energy consumption, and output yields. These data illustrate the seasonal variability in both cafeteria waste generation and processing efficiency.

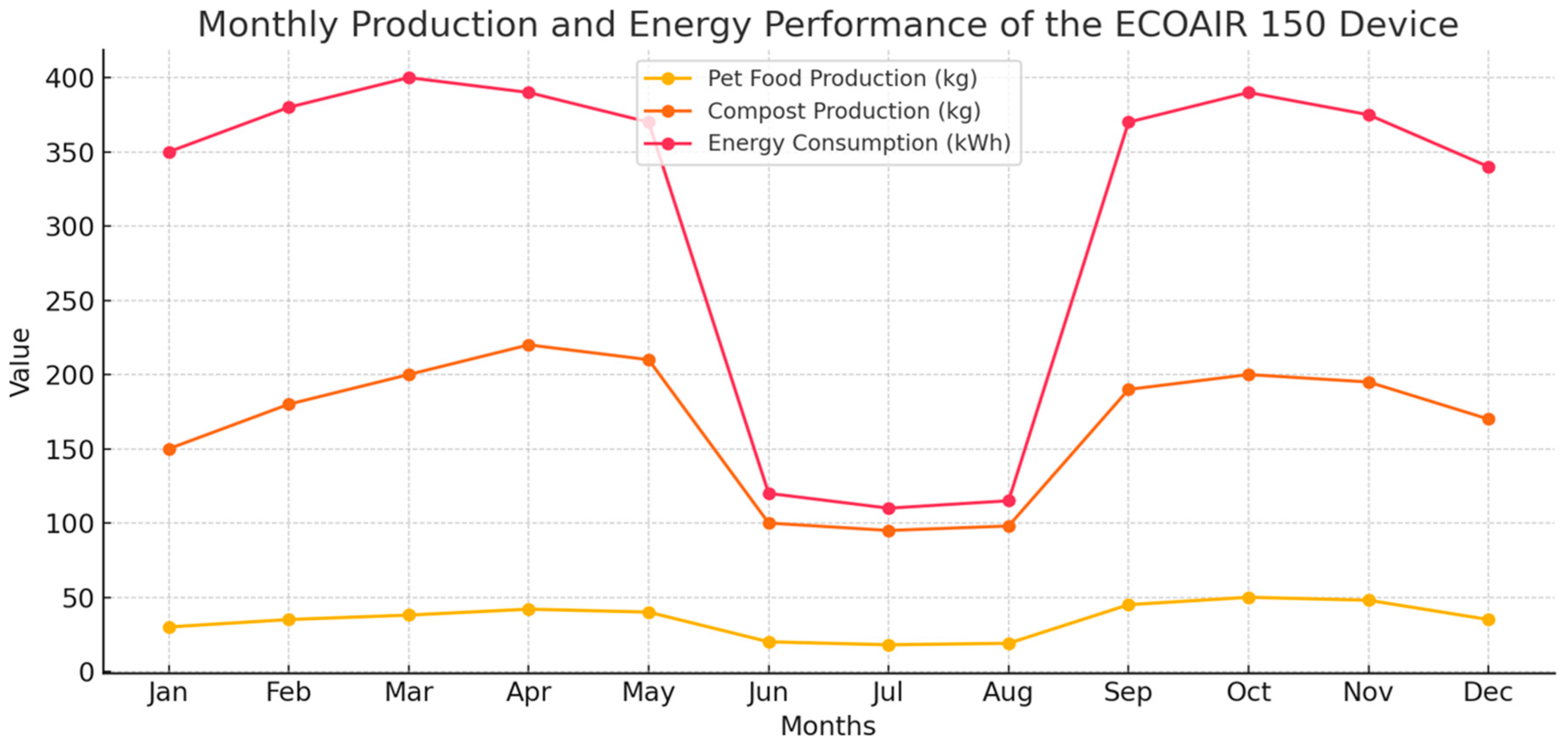

The graph below demonstrates the monthly production quantities of pet food and compost, as well as the energy consumption of the ECOAIR 150 unit over a 12-month period (

Figure 1). The values clearly reflect seasonal fluctuations influenced by academic calendar cycles. Notably, peak waste processing occurred between February and May, corresponding to the active academic term. In contrast, a sharp decline is observed during the summer months (June–August), when cafeteria operations are significantly reduced due to semester breaks. This variation highlights the dependency of circular processing efficiency on institutional activity levels and reinforces the need for adaptive operational scheduling in similar university-based systems.

2.2.2. Energy Consumption and Solar Power Plant Integration

The total annual energy consumption of the ECOAIR 150 device was recorded at approximately 3,800 kWh. This entire energy demand is met through the ALKU Campus rooftop solar power plant, ensuring zero external electricity usage and enabling a carbon-neutral operation. The full reliance on renewable energy makes the waste processing system both environmentally and economically sustainable.

On average, the system produces approximately 0.56 kilograms of pet food per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of energy consumed, indicating a strong energy-to-product efficiency for a semi-automated process. Monthly operational data reveals that this performance varies in line with campus activity patterns.

As shown in

Table 3, the monthly values for feedstock input, compost output, energy usage, and productivity rate clearly demonstrate seasonal shifts in cafeteria waste generation and the corresponding system performance. For instance, between February and May, all performance indicators peak due to increased student presence and cafeteria activity. Conversely, energy usage and production volumes drop sharply during the summer months (June to August), when campus operations slow down.

2.3. Menu-Based Waste Sources and Input Analysis

In the ecocircular cafeteria model implemented at ALKU, waste separation is conducted not only quantitatively but also based on the qualitative content of food waste. This dual-layered approach allows each type of waste to be directed toward the most appropriate valorization method—either composting or pet food production—thereby increasing the overall efficiency and environmental performance of the system.

To develop this waste management model, one full academic year’s worth of cafeteria menus was analyzed. As a result, 30 recurring menu combinations were identified, each with distinct waste generation characteristics. These menus were categorized into two main groups depending on the type and recyclability of the waste they produced.

The first group includes menus suitable for composting, which primarily consist of unprocessed organic waste such as vegetable peels, fruit pulp, tea residues, cabbage leaves, and similar materials. These wastes are low in protein but rich in fibrous organic content, making them ideal for biological decomposition and nutrient cycling in compost production.

The second group encompasses menus suitable for pet food production, which contain cooked food leftovers that are high in carbohydrates and proteins. Examples include rice, legumes, pasta, meat-based dishes, and fried foods. These waste types are readily degradable and yield significantly higher dry mass when processed into pet food.

By classifying menus in this manner, the university was able to strategically optimize the operation of the ECOAIR 150 processing unit. Input streams were matched to the device’s technical capabilities, ensuring higher conversion efficiency, shorter processing durations, and more stable energy consumption profiles.

This classification is illustrated through a representative selection of 10 menu samples, presented in

Table 4. The table outlines the content summary of each menu, the identified waste type, the end product (compost or pet food), the quantity of raw waste, the resulting product amount, and the conversion yield. As seen in the data, menus rich in starches and proteins—such as ravioli, chickpeas with meat, or meatballs—produced pet food at high yields (typically above 70%). In contrast, menus containing raw vegetable scraps yielded compost at lower but consistent conversion rates, generally ranging between 7% and 12%.

This systematic approach demonstrates that aligning cafeteria menu planning with waste recovery strategies can significantly improve operational efficiency and sustainability outcomes on campus. It also offers a replicable framework for other institutions aiming to implement circular waste management systems.

2.4. Production Process: Conversion Recipes and Outputs

The waste recycling process implemented under the ALKU Ecocircular Cafeteria Project is structured around two main recycling outputs: compost and animal food. These processes are both content- and technology-specific and are executed using the ECOAIR 150 device. On average, one to two waste batches are loaded daily into the device’s 150-liter hopper. Depending on the day's menu and the resulting waste composition, these batches are either processed immediately or stored and mixed to ensure homogeneous input.

Organic kitchen waste—such as vegetable and fruit peels, tea pulp, and onion stems—is particularly suited for composting due to its low protein and high cellulose content, which provides a balanced carbon-to-nitrogen ratio. In contrast, cooked food leftovers—including rice, pasta, beans, meat dishes, and fries—are rich in carbohydrates and proteins and are ideal for the production of animal food. These food residues are easily degradable and allow for faster processing times and higher product yields.

Two standard conversion protocols, referred to as Type A (compost) and Type B (animal food), were developed based on field trials. In compost production, approximately 80–100 kg of organic waste is processed over 36 hours, consuming about 14 kWh of energy, and yielding 8–10 kg of dry compost. Compost was primarily used in on-campus organic farming and landscaping applications. Internal temperatures reached 60–70°C, promoting microbial breakdown and eliminating pathogens. In some cases, secondary top-up inputs of 20–30 kg were added to extend recovery.

For animal food production, 60–90 kg of cooked leftovers were processed over 24–30 hours, consuming around 11 kWh of energy, and yielding 40–70 kg of dry food. The final product, after cooling, was directly distributed for stray animal feeding and also shared with students. Laboratory analysis confirmed that the product met daily protein requirements.

These processes are summarized in

Table 5, which presents representative data on input amounts, processing durations, energy use, and output quantities for both waste types.

2.5. Energy Consumption and Solar Power Plant Integration

The success of ecocircular cafeteria systems is determined not only by the effectiveness of waste management but also by the sustainability and autonomy of the energy sources that power them. At Alanya Alaaddin Keykubat University (ALKU), a circular transformation model has been implemented in which the entire waste processing operation is powered by renewable energy—specifically, photovoltaic solar energy—with the goal of achieving energy independence and carbon neutrality.

The system operates in full integration with a 1710.72 kWp rooftop Solar Power Plant (SPP) installed on the campus. This installation was realized through an Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) model, which remains a relatively rare approach in Türkiye’s public sector. The EPC framework enabled the project to be financed and implemented via a performance-based reimbursement mechanism within a public-private partnership (PPP) structure. The technical and economic design and outcomes of this solar infrastructure were reported in a previous peer-reviewed publication [

73].

According to that study, “The solar power plant in question is one of the first in Türkiye to be built with the EPC model. Within 12 months, it produced 2.4 GWh of energy and prevented 1,168 tons of CO₂ emissions, exceeding contractual energy targets by 16.2%” [

73].

Thanks to this renewable infrastructure, all operations of the ECOAIR 150 device—whether for compost or pet food production—have been conducted with zero net carbon emissions, creating a system that qualifies as a “net-zero energy consumption” model.

Monthly performance data further reflect this integration. As presented in

Table 6, the system consumed a total of 3,980 kWh of electricity over the course of one year, resulting in an estimated 17.61 tons of CO₂ emissions prevented when compared to the national energy grid average.

2.6. Economic Analysis and Carbon Footprint Indicators

The success of an ecocircular system depends not only on environmental but also on economic sustainability. Therefore, the system's economic performance, including its recycling capacity, market value of the resulting products, and energy savings, has been comprehensively analyzed. The analysis is structured to include total revenue potential, payback period, and impacts such as carbon externalities.

2.6.1. Monthly Economic Contributions

Food Production (12 months total): 2339 kg

Compost Production (12 months total): 368 kg

Energy Savings: 3,980 kWh ≈ 438 USD

Annual Total Economic Contribution: ≈ 2,751 USD

The annual total income calculation is as follows:

Food income = 2339 × 0.90 = 2,105.1 USD

Food income = 2339 × 0.90 = 2,105.1 USD

Compost income = 368 × 0.40 = 147.2 USD

Compost income = 368 × 0.40 = 147.2 USD

Energy savings = 3,980 × 0.11 = 437.8 USD

Energy savings = 3,980 × 0.11 = 437.8 USD

Total contribution = 2,105.1+147.2+437.8=2,690.1 USD

Total contribution = 2,105.1+147.2+437.8=2,690.1 USD

2.6.2. Payback Period and Net Present Value

Total investment cost: 8,000 USD

Annual net benefit: ≈ $2,690

Amortization period (payback): ≈ 2.97 years

A positive and strong Net Present Value (NPV) confirms the investment feasibility and economic viability of the system.

2.6.3. Carbon Reduction and Environmental Impact

The ecocircular cafeteria system at ALKU achieved significant carbon reduction through the integration of renewable energy. Based on Türkiye’s national electricity grid emission factor (0.0046 tons CO₂/kWh), the carbon emissions avoided through solar-powered operation of the ECOAIR 150 system are calculated as follows:

3,980 kWh × 0.0046 tons CO₂/kWh ≈ 18.3 tons CO₂/year

Additionally, by utilizing compost in place of synthetic fertilizers for on-campus landscaping and agriculture, an estimated 0.9 tons of CO₂ equivalent was further avoided. These combined savings demonstrate the system’s tangible contribution to climate mitigation through both energy and material substitution.

2.6.4. Economic and Environmental Integration

The system’s sustainability is not limited to environmental gains. The use of Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) to finance the solar infrastructure and the elimination of electricity costs (estimated at ~$438/year) represent a replicable economic model for other public institutions in Türkiye. Furthermore, avoided carbon emissions equate to an externality value of approximately $350/year, based on conservative carbon pricing in voluntary markets. This holistic approach unites energy autonomy, waste valorization, and cost-effectiveness under one circular framework.

2.7. Monitoring, Measurement, and Data Collection Methodology

Evaluating the performance and impact of an ecocircular cafeteria system requires not only measuring output quantities but also maintaining reliable and traceable process data. At ALKU, a comprehensive data management framework was established to monitor waste separation, device operation, energy consumption, and product outputs on a weekly and monthly basis.

2.7.1. Data Collection Tools and Formats

Operational data were logged daily by device operators using standardized Excel-based templates. These entries were compiled monthly and used for performance evaluation. The following parameters were recorded:

Start date and time of operation

Waste amount and type (kg)

Input content (e.g., vegetable scraps, cooked meals)

Device program mode and operation time (hours)

Output type (compost or pet food)

Output quantity (kg)

Energy consumption (kWh)

Observation notes (e.g., rework due to drying issues, recipe adjustments)

Data entry was conducted manually after each batch, with anomalies such as insufficient drying or abnormal moisture content noted separately.

2.7.2. Menu-Based Waste Categorization and Operational Outcomes

Estimated and actual waste characteristics were cross-referenced with the planned menus to improve forecasting accuracy. As shown below, menu content directly influenced waste type, device performance, and output efficiency:

Table 7.

Menu-Based Waste Typology and Classification for Processing Optimization.

Table 7.

Menu-Based Waste Typology and Classification for Processing Optimization.

| Menu No. |

Example Content |

Waste Type |

| 3 |

Ravioli, red mullet, meat döner, fries, bread |

High protein, high fat |

| 9 |

Red cabbage, lettuce, tea pulp |

High fiber, low calorie |

| 14 |

Pasta, ladyfinger meatballs, rice, kidney beans, bread |

Starch-heavy, protein-rich |

Food or compost yield, as well as energy consumption and device operation time, varied significantly across menu types. For instance, menus rich in protein and fat (such as those containing meat döner and fried food) increased drying time and energy demand, while vegetable-based menus resulted in faster processing but lower product yield.

The full operational flow followed a consistent process:

Waste classification: Waste was separated at the source by cafeteria staff.

Device feeding: Waste was manually loaded into the ECOAIR 150.

Program execution and monitoring: Start and end times were logged; issues like incomplete drying were resolved by restarting.

Result recording: Final data were entered into Excel.

Monthly analysis: All recorded data were analyzed graphically and numerically to support performance tracking and reporting.