Submitted:

31 July 2025

Posted:

01 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

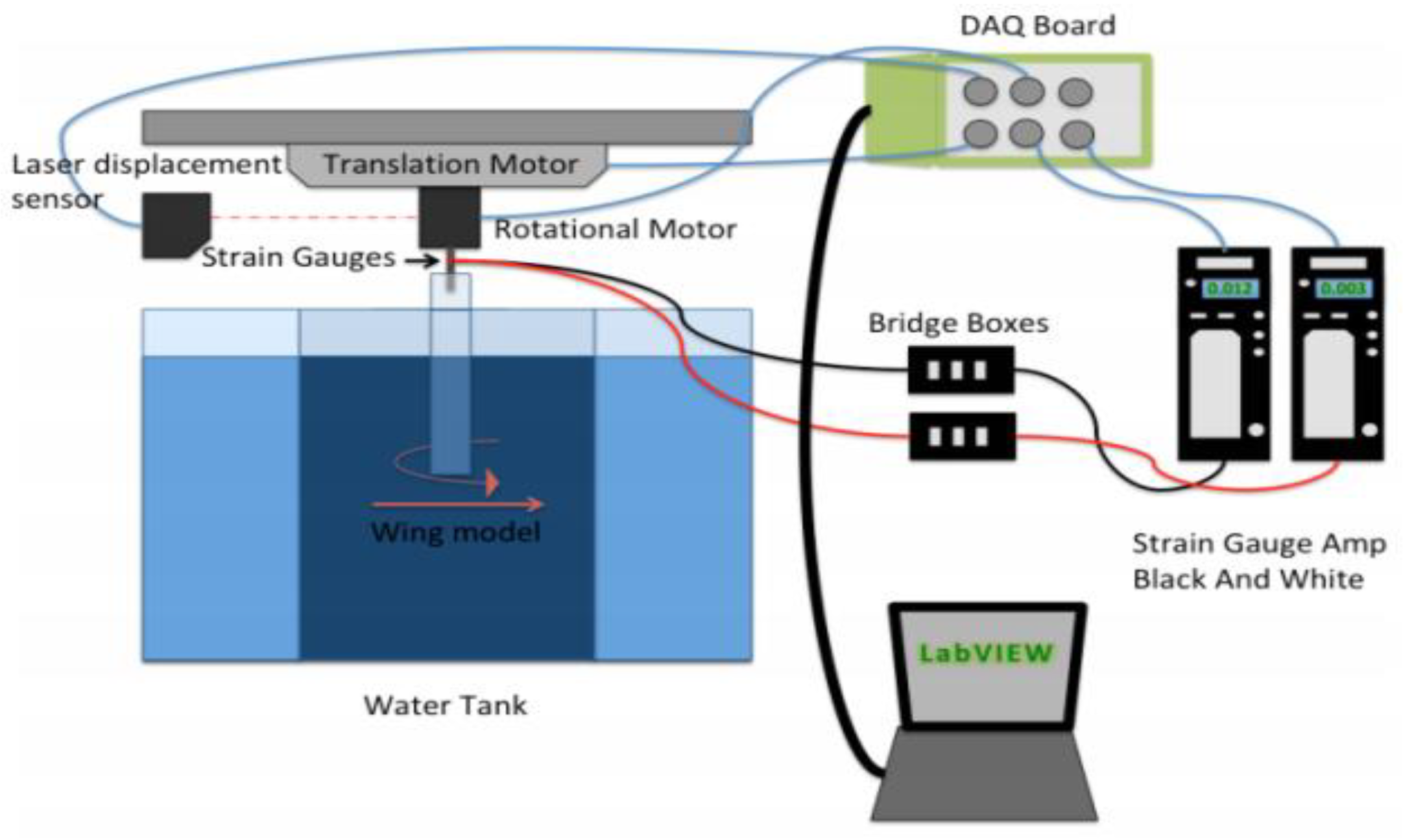

2. Experiment

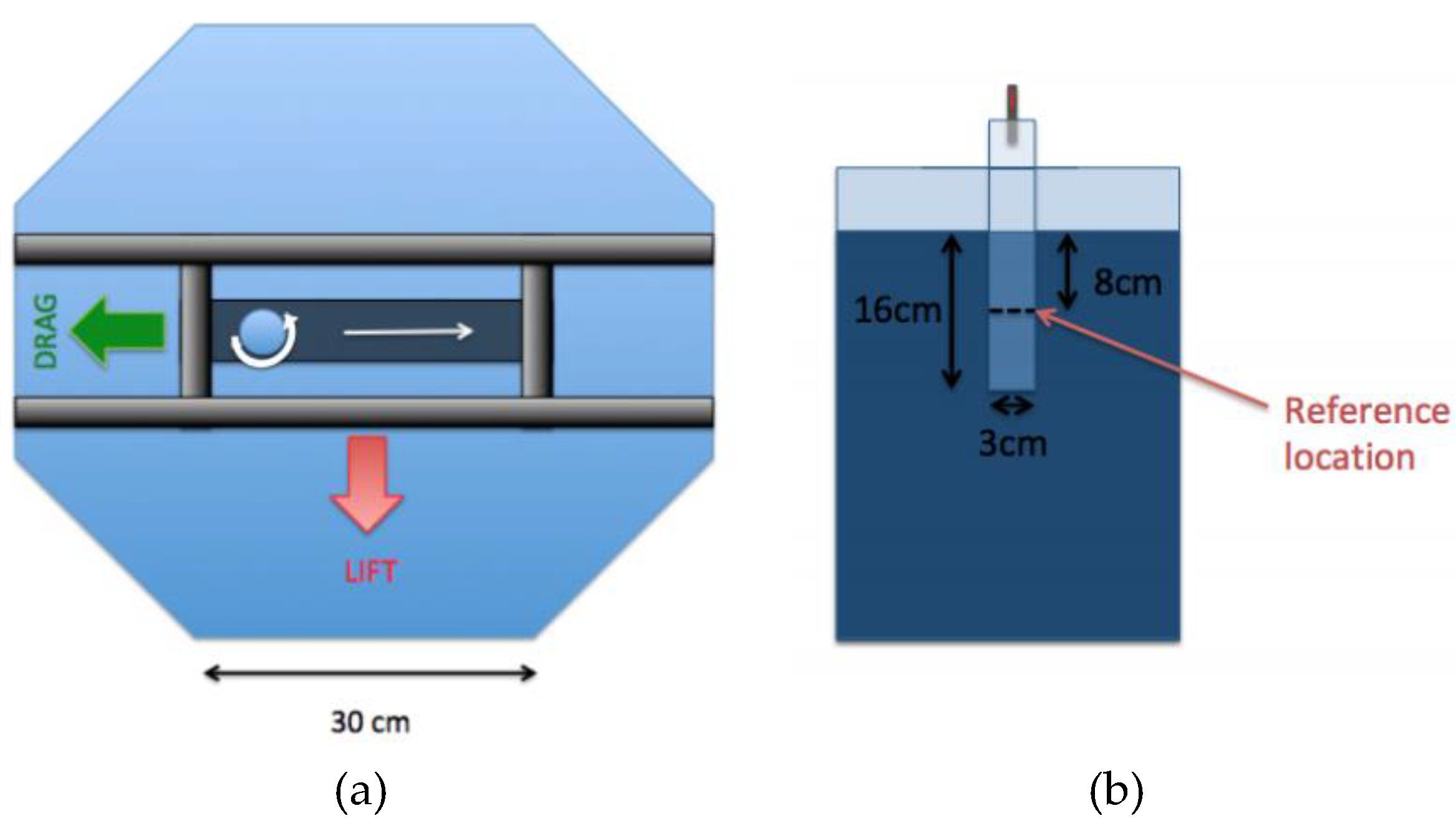

2.1. Experiment Description

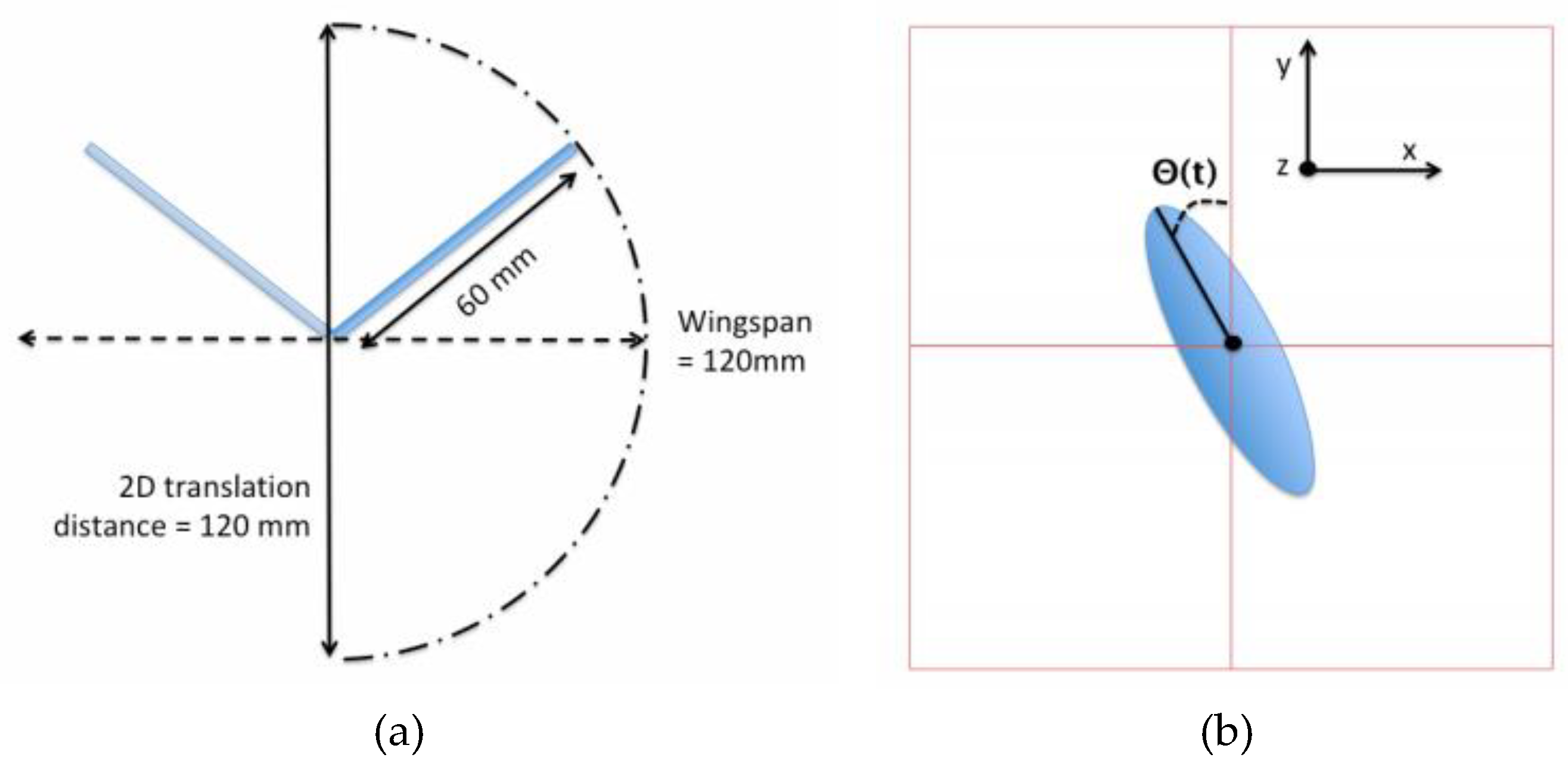

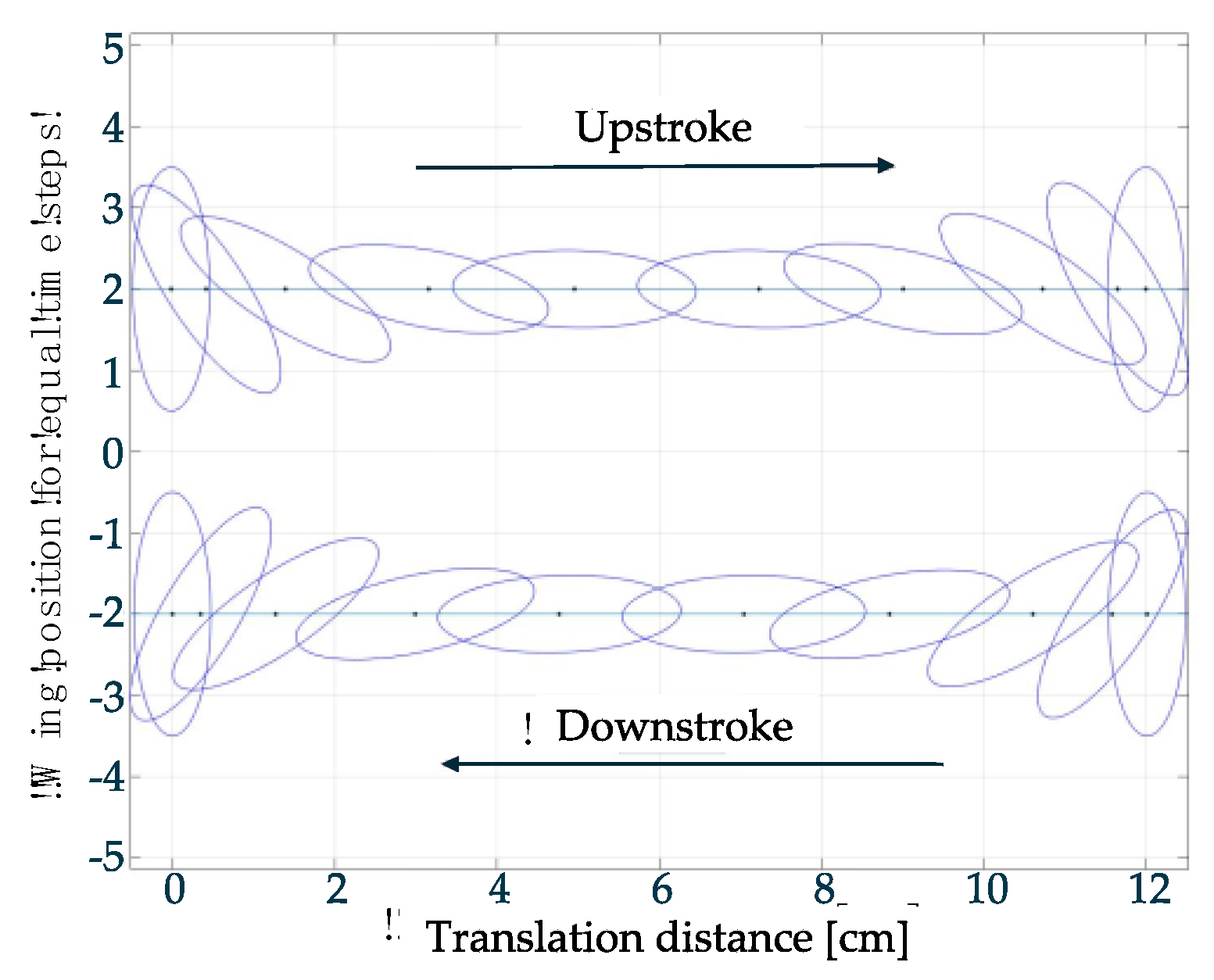

2.2. Flapping Motion

2.3. Equipment

2.3.1. Water Tank

2.3.2. Motors

2.3.3. Wings

-

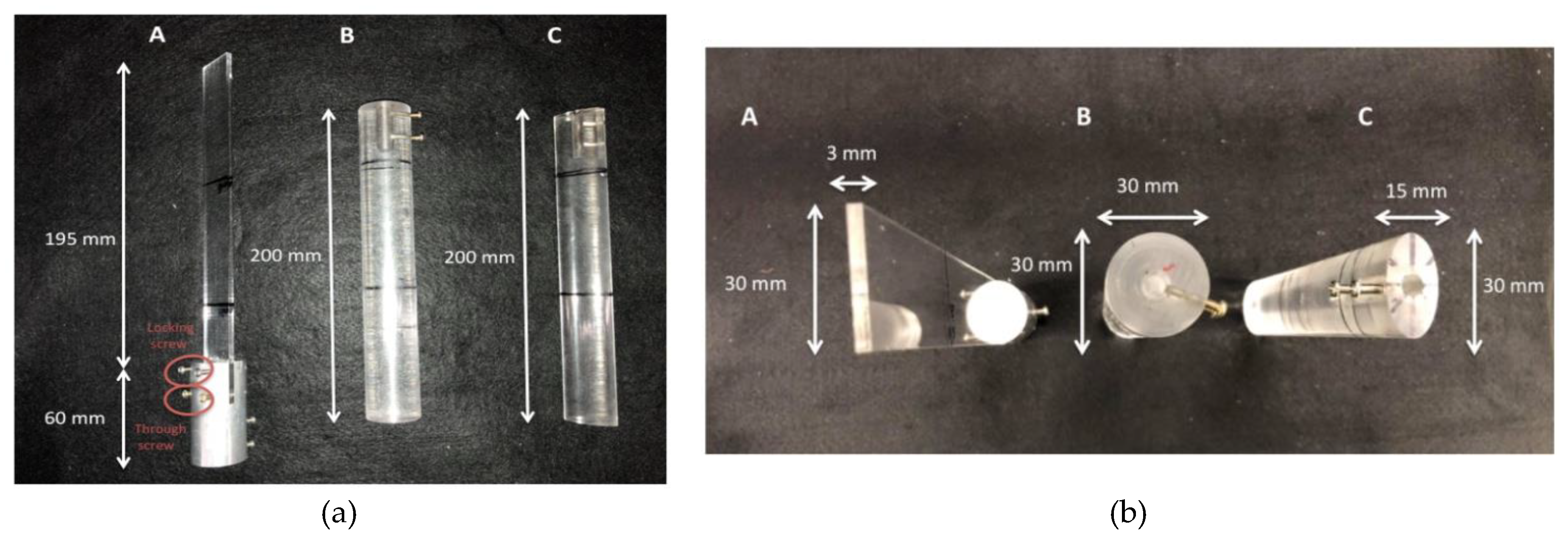

Circular cylinder model;The circular cylinder model shown on Figure 5 B serves as a reference model in this experiment, since it is assumed to have purely rotational effect avoiding the complexity of wing profile. The cylinder has a length of 200 mm, and a diameter of 30 mm. The 30 mm depth hole on the top to attach the rotational axis on which strain gauges are attached has a diameter of 6 mm. Two tapped holes on the side near the top, having 3 mm in diameter were made to finally tighten the cylinder onto the rotational axis.

-

Flat plate model;Another model is a flat plate clipped by a coupler, which fixes the model to the rotational axis shown on Figure 5 A. The plate has also a chord length of 30 mm with a total length of 220 mm where 25 mm is located between the clips in order to be well fixed. This plate model has a thickness of 3 mm in order to avoid any elastic deformation while being as thin as possible. The aluminum coupler piece has 30 mm in diameter and 80 mm in span wise length. It has two holes for through screw to hold the flat plate, and two other holes for locking screw to tighten the plate. Finally, the two screws on the left hand side are used to fix the whole plate model on the brass rotational axis. With this model, it is the most likely the Kramer effect will be observed during the supination and the pronation.

-

Elliptical cylinder model.The elliptical cylinder model shown on Figure 5 C has for main purpose to have a shape in between the flat plate model and the circular cylinder model. With a big axis of 30 mm, a small axis of 15 mm and then an eccentricity of e = √2 this model will have for purpose to be compared to the circular cylinder model and the flat plate model. The other mechanical specifications are similar to the circular cylinder model. We will try to figure out what kind of effect, and in what proportion, is responsible of the lift production, more precisely of the rotational lift production in this transition case.

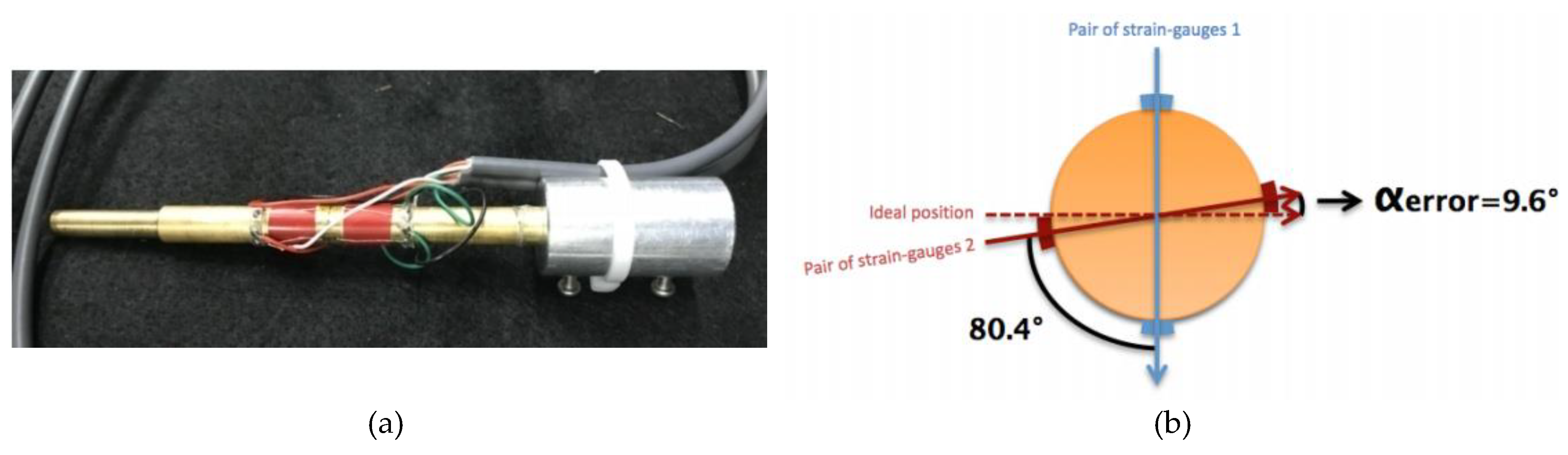

2.3.4. Strain Gauges

2.4. Direct Force Measurement

2.4.1. Lift and Drag Computation

2.4.2. Phase Averaged Lift and Section Lift Coefficient

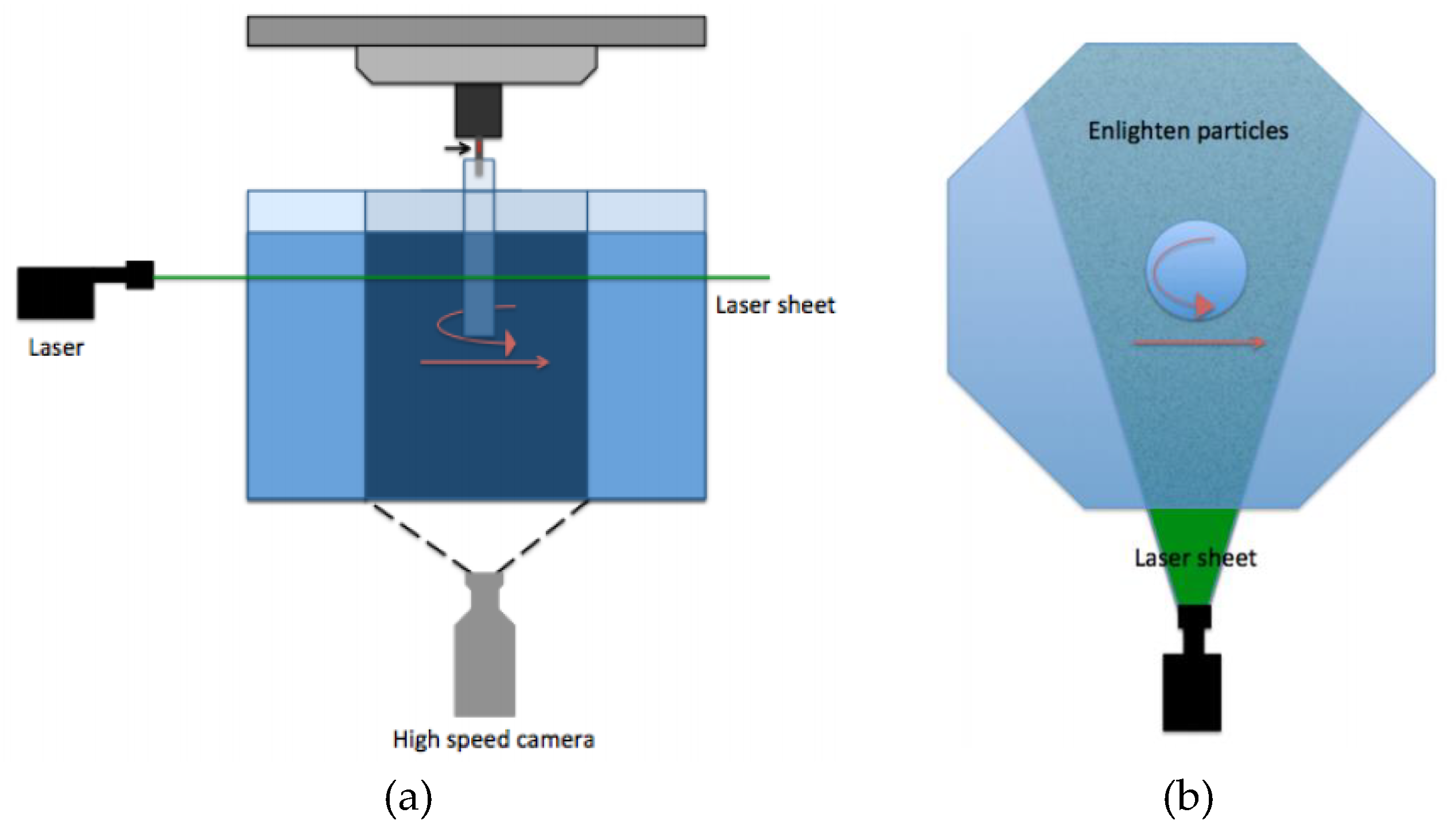

2.5. PIV Measurement and Flow Structure Analysis

2.5.1. Method Description

2.5.2. Lift Computation Using Kutta-Joukowski Theorem

3. Computation

4. Experimental and Computational Results

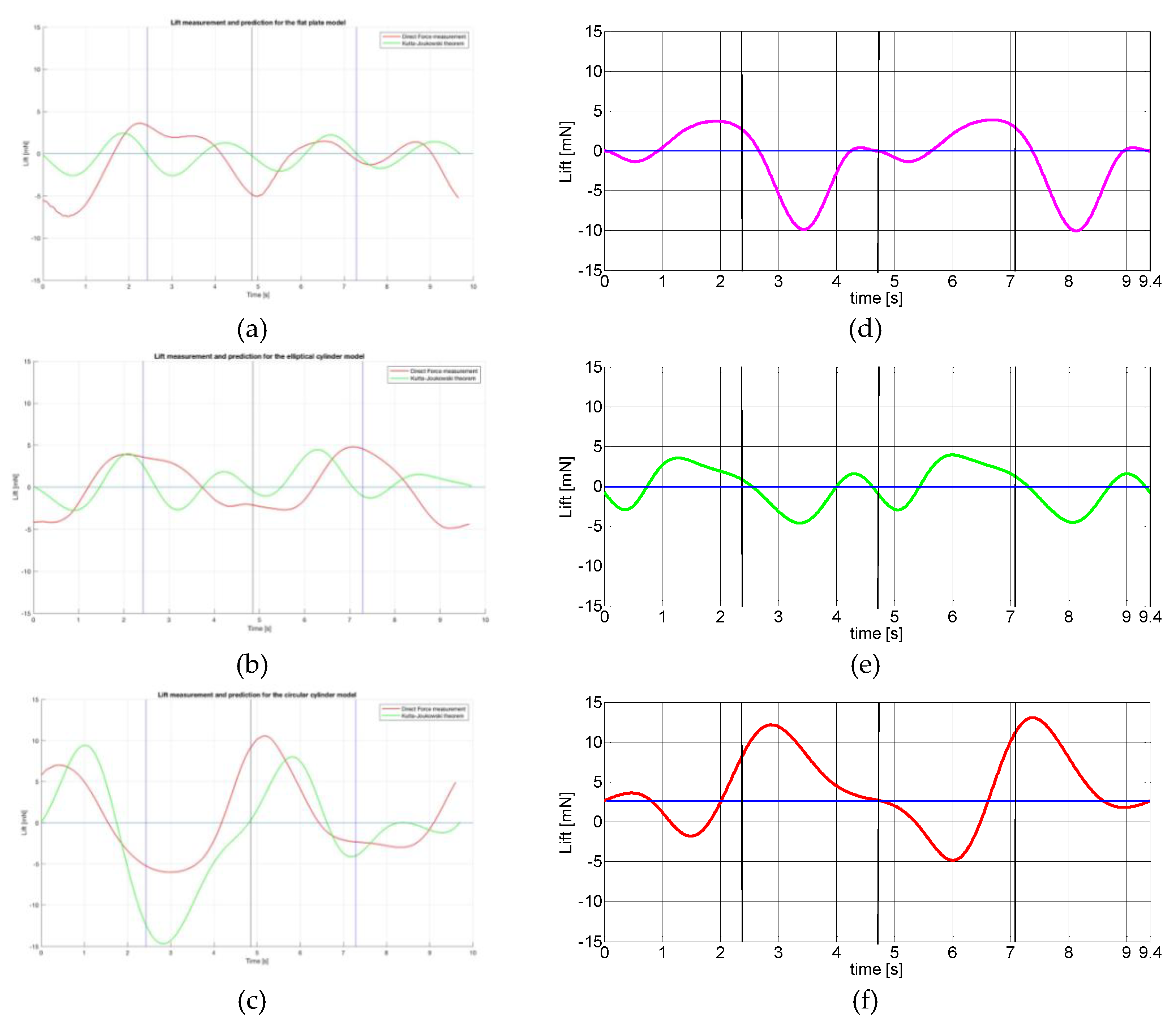

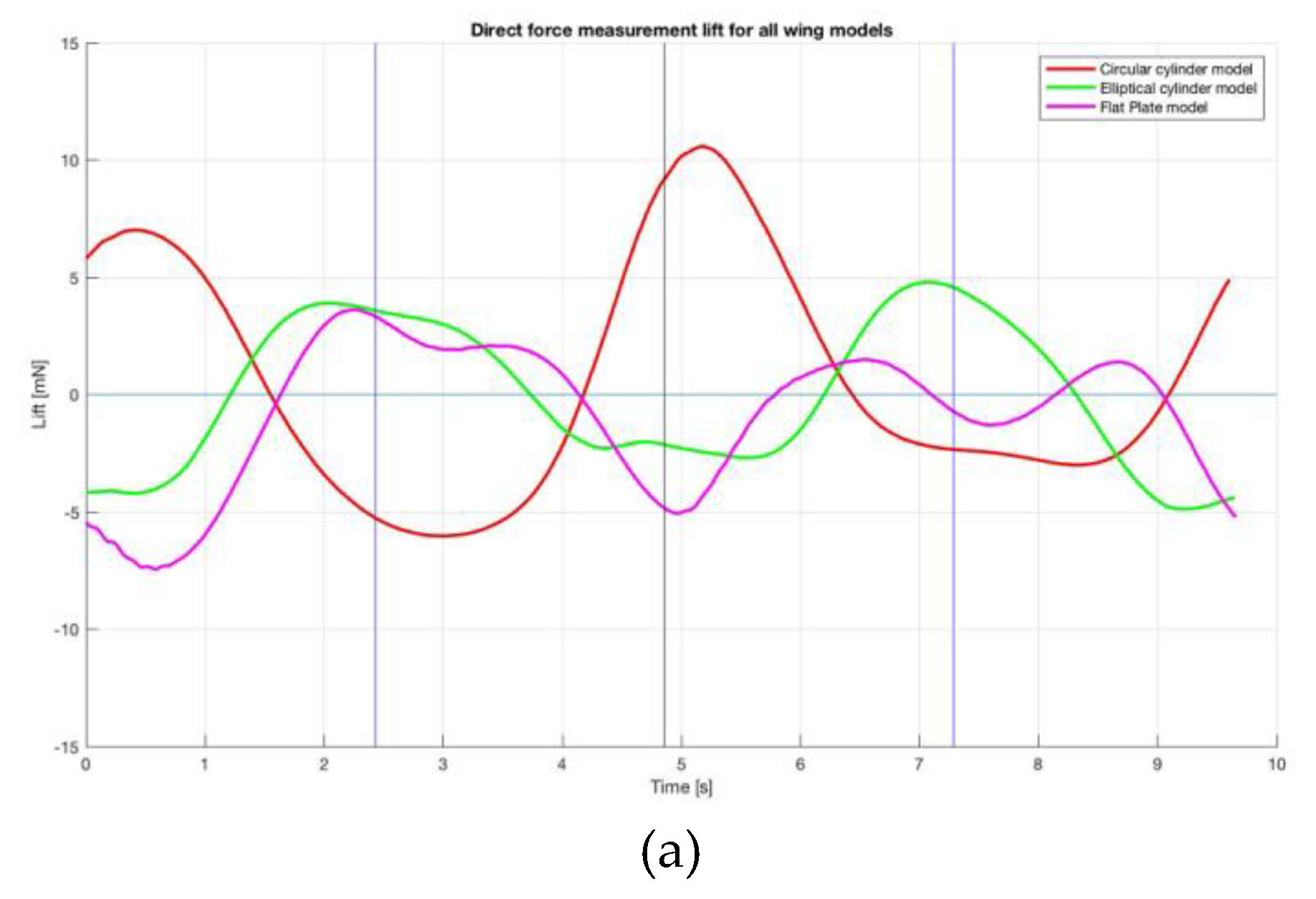

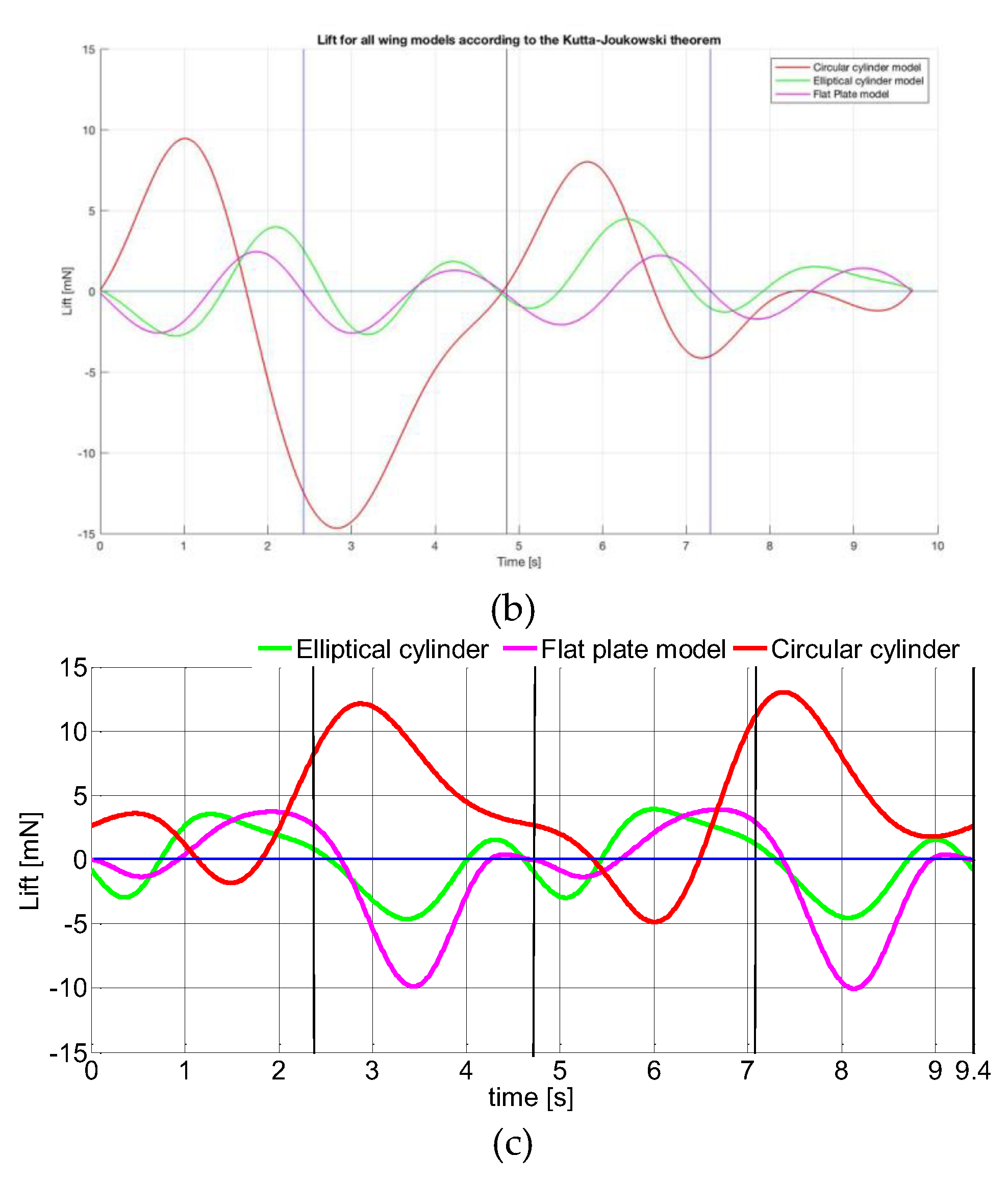

4.1. Kutta-Joukowski Theorem and Direct Force Measurement

4.2. Comparison Between Experimental and Computational Results

4.3. Lift and Flow Structures

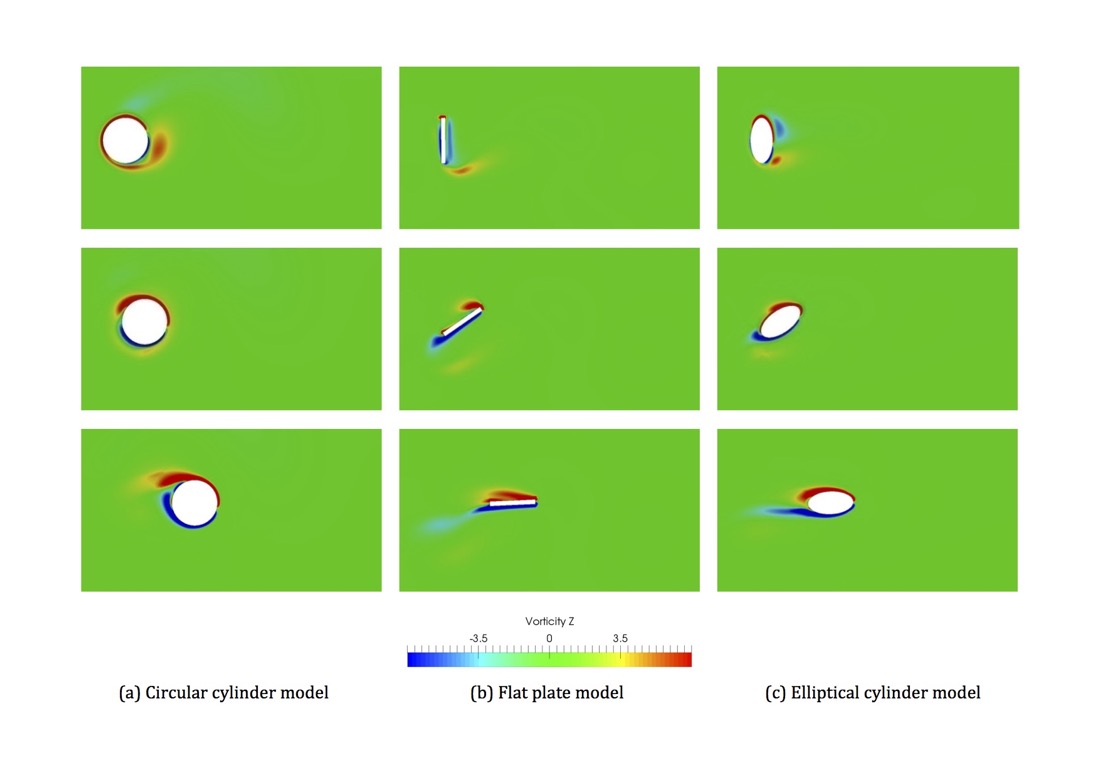

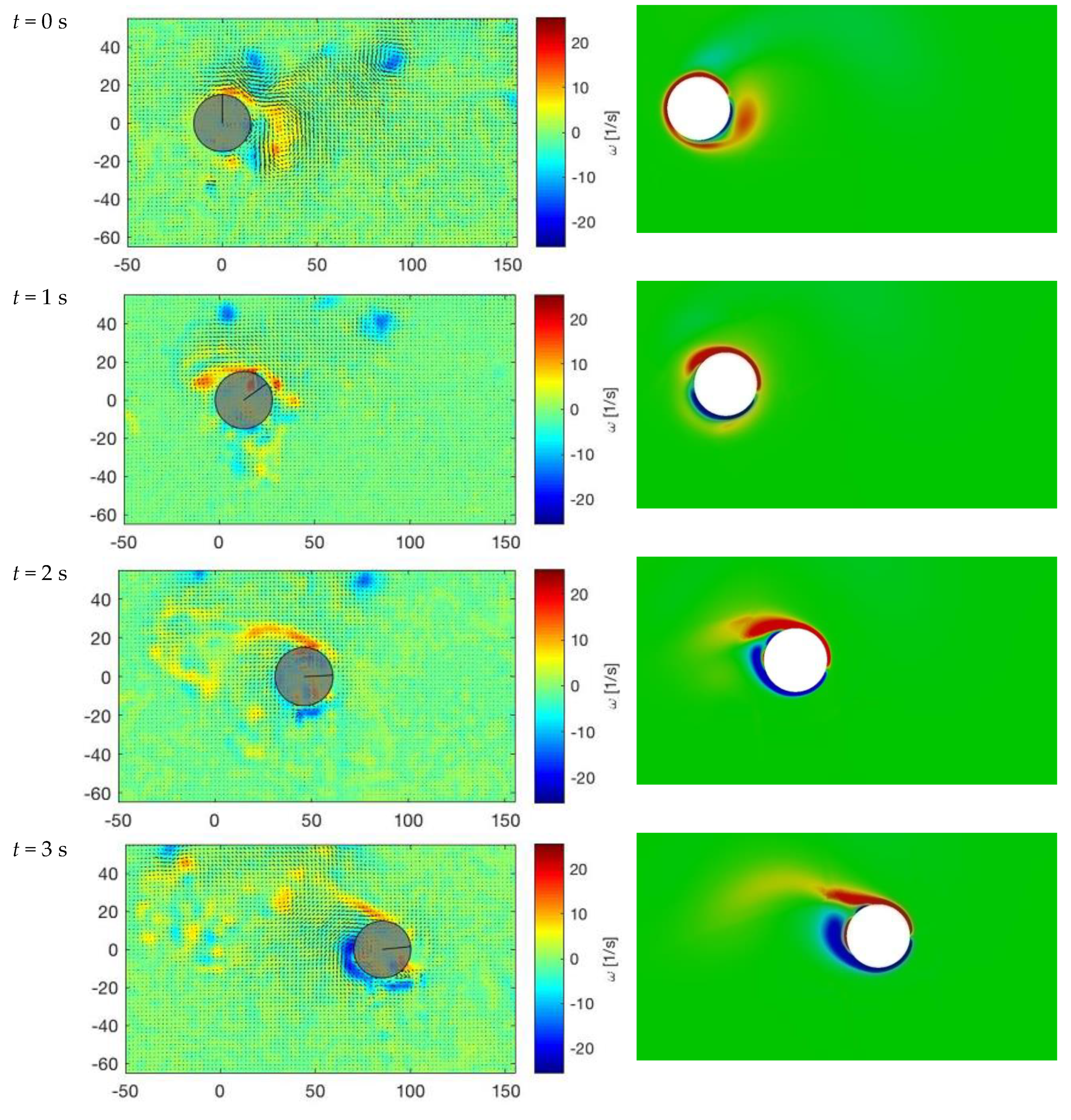

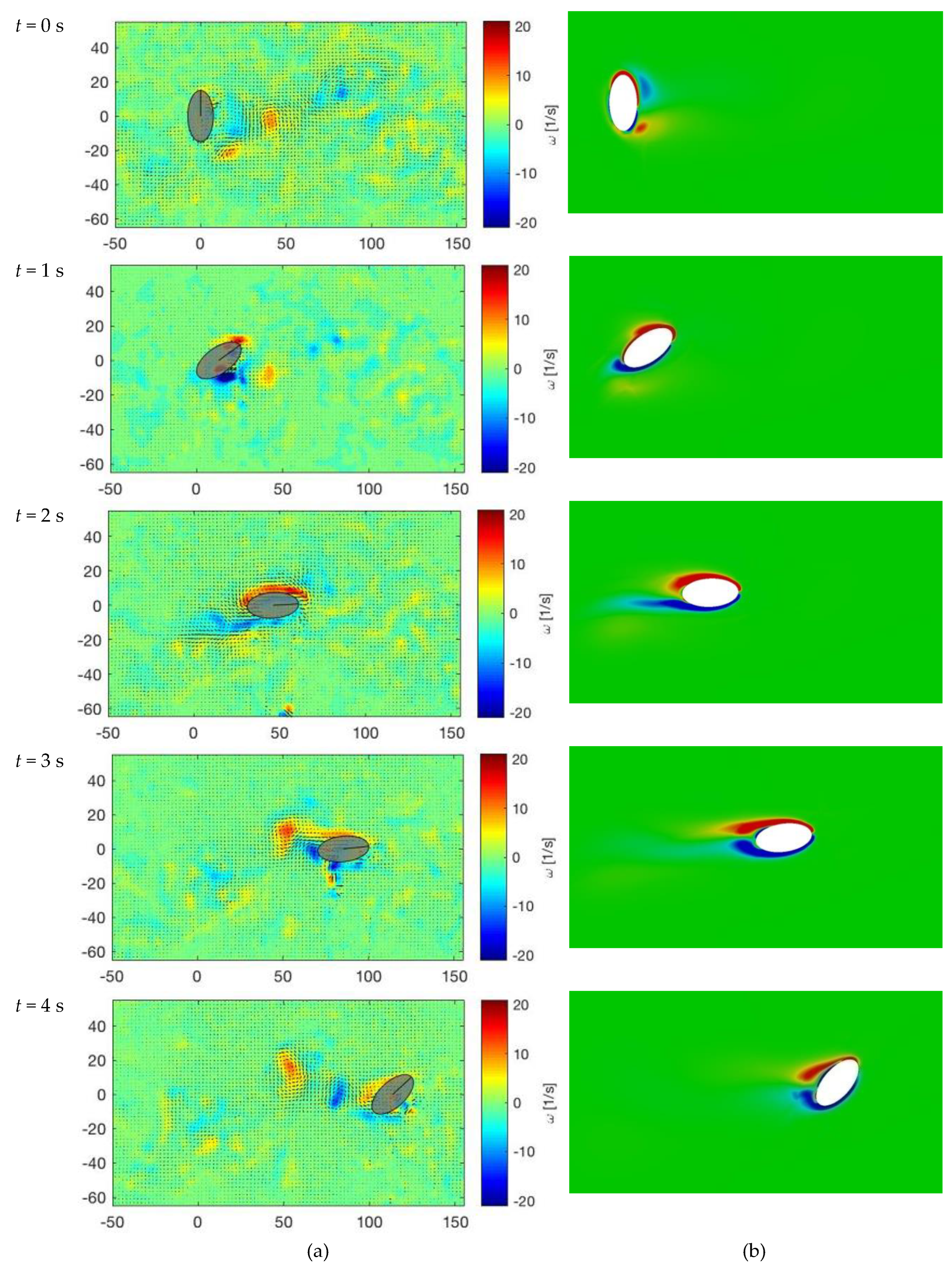

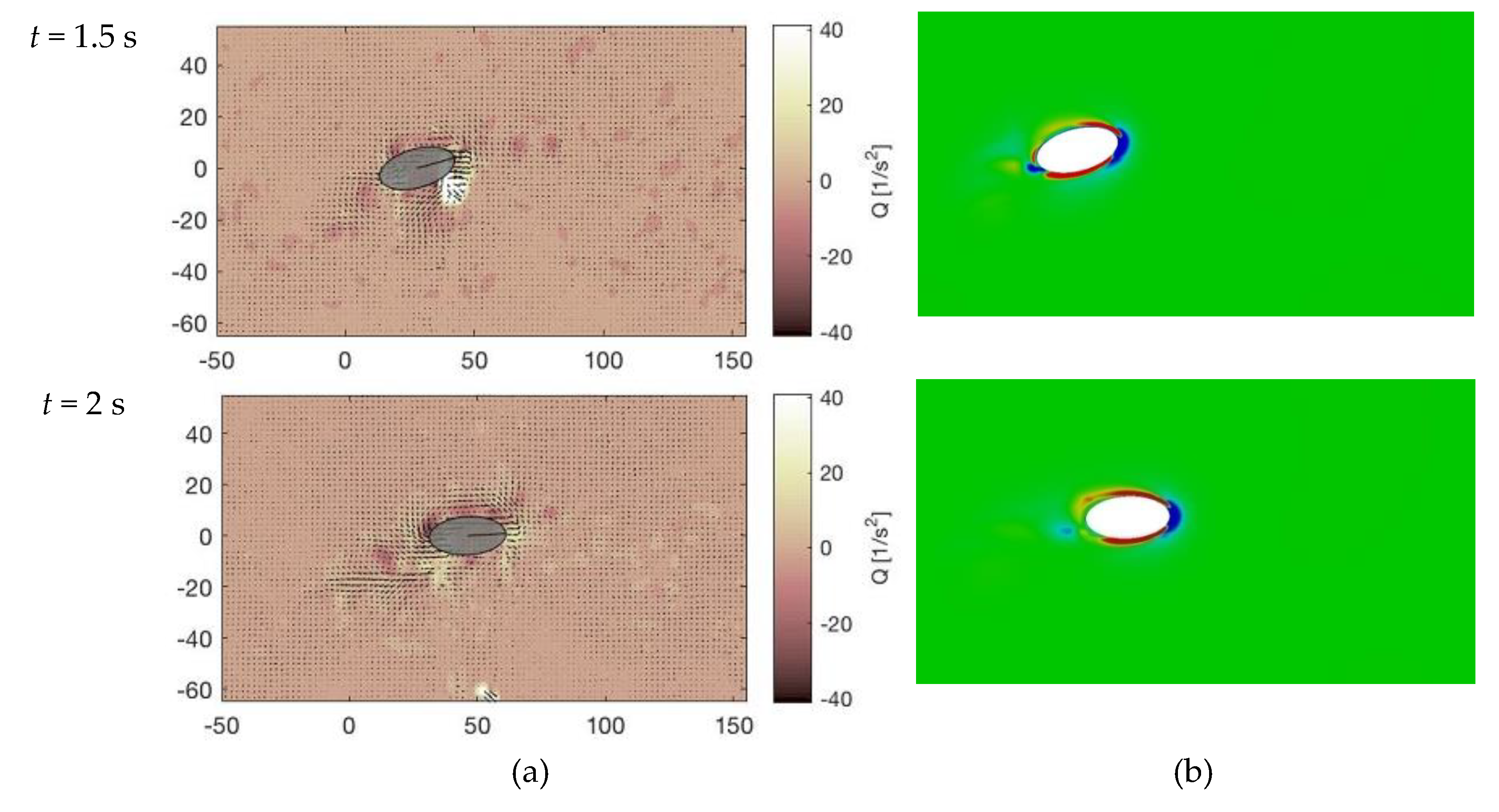

4.3.1. Circular Cylinder Model

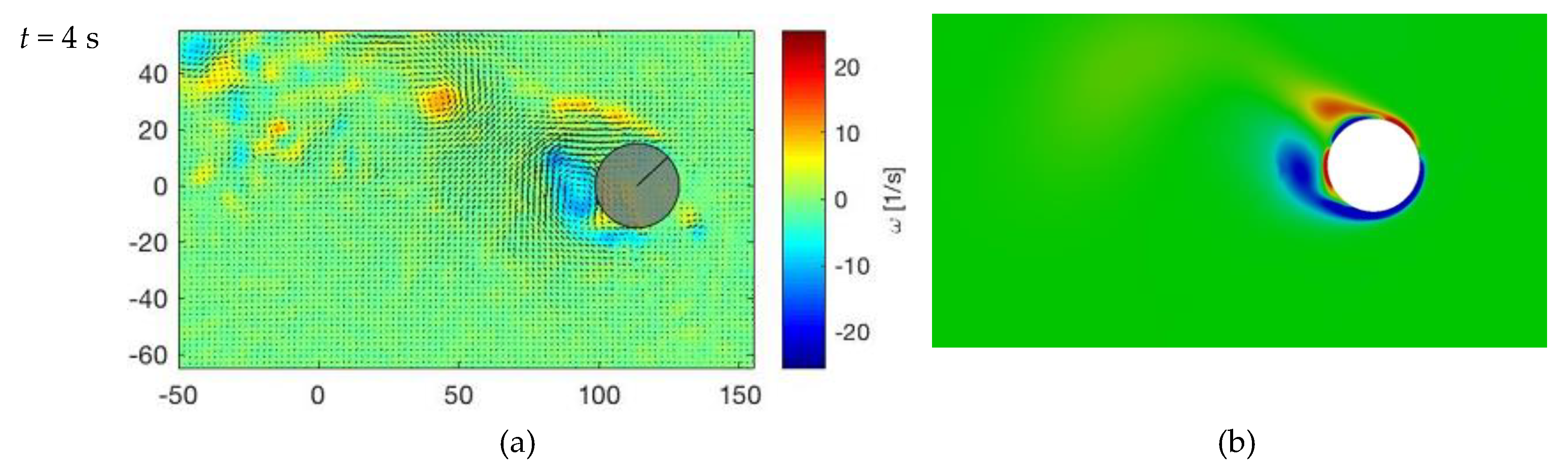

4.3.2. Flat Plate Model

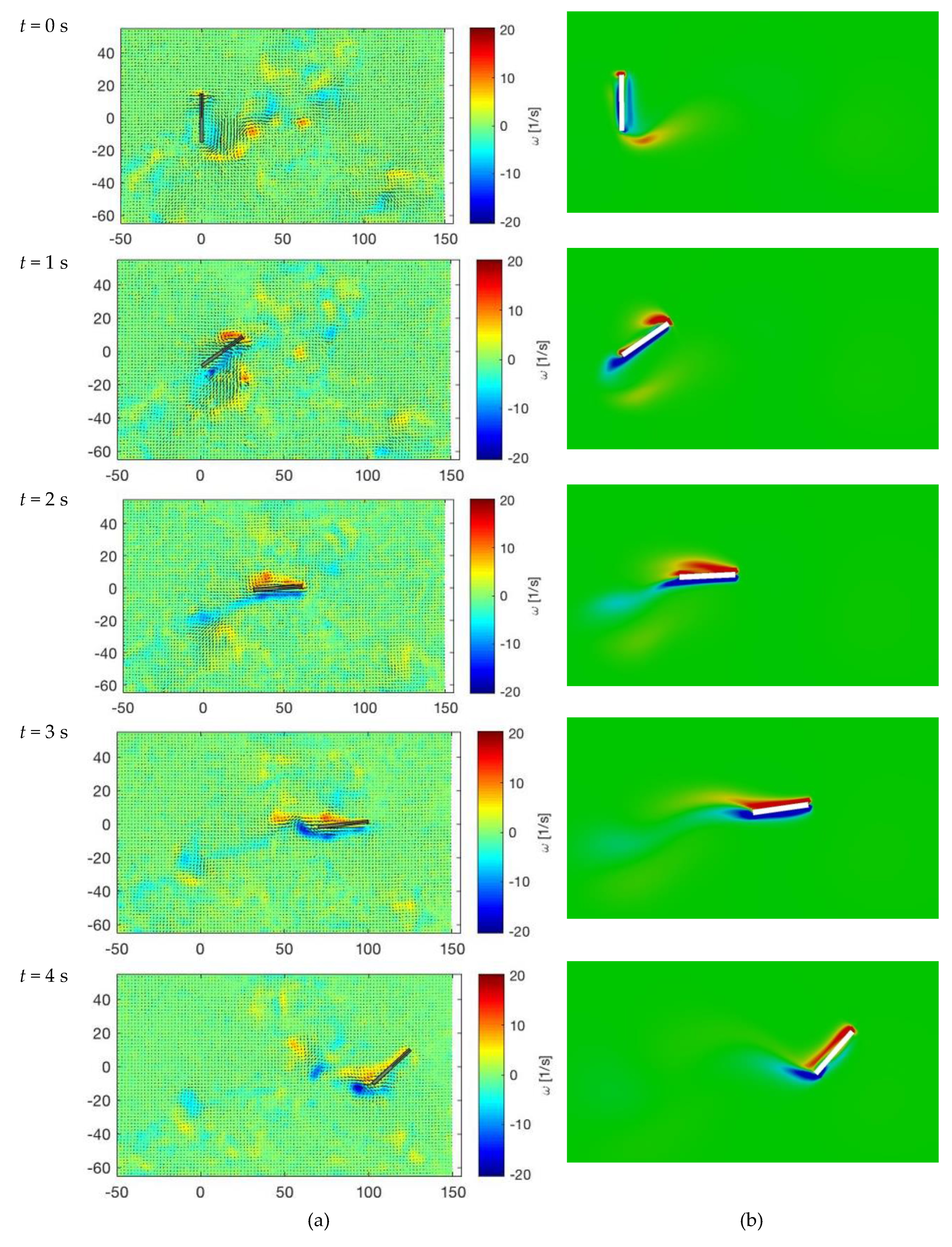

4.3.3. Elliptical Cylinder Model

5. Discussions

5.1. The Magnus Effect and the Kramer Effect

5.1.1. The Circular Cylinder Model and Magnus Effect

5.1.2. The Flat Plate Model and Kramer Effect

5.1.3. The Elliptical Cylinder Model

5.2. Comparison of the Three Wing Models

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PIV | Particle image velocimetry |

| UAV’s | Unmanned air vehicles |

| BAV’s | Bio-mimetic air vehicles |

| LEV | Leading edge vortex |

| AoA | Angle of attack |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamic |

| PISO | Pressure Implicit with Splitting of Operator |

References

- Ellington, CP. The novel aerodynamics of insect flight: applications to micro-air vehicles. Journal of Experimental Biology 1999, 202, 3439–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope DK, DeLuca AM, O’Hara RP. Investigation into Reynolds number effects on a biomimetic flapping wing. International Journal of Micro Air Vehicles 2018, 10, 106–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyy W, Aono H, Kang CK, Liu H. An introduction to flapping wing aerodynamics. Cambridge University Press; 2013 Aug 19.

- Dickinson MH, Götz KG. Unsteady aerodynamic performance of model wings at low Reynolds numbers. Journal of Experimental Biology 1993, 174, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleaver D, Wang Z, Gursul I. Delay of stall by small amplitude airfoil oscillations at low Reynolds numbers. In 47th AIAA aerospace sciences meeting including the new horizons forum and aerospace exposition 2009 Jan (p. 392).

- Birch JM, Dickinson MH. The influence of wing–wake interactions on the production of aerodynamic forces in flapping flight. Journal of Experimental Biology 2003, 206, 2257–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan X, Zhu S, Su Z, Zhang H. Added mass effect and an extended unsteady blade element model of insect hovering. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2011, 8, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sane SP, Dickinson MH. The aerodynamic effects of wing rotation and a revised quasi-steady model of flapping flight. Journal of Experimental Biology 2002, 205, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson MH, Lehmann FO, Sane SP. Wing rotation and the aerodynamic basis of insect flight. Science 1999, 284, 1954–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun M, Tang J. Unsteady aerodynamic force generation by a model fruit fly wing in flapping motion. Journal of Experimental Biology 2002, 205, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun M, Tang J. Lift and power requirements of hovering flight in Drosophila virilis. Journal of Experimental Biology 2002, 205, 2413–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyy W, Aono H, Chimakurthi SK, Trizila P, Kang CK, Cesnik CE, Liu H. Recent progress in flapping wing aerodynamics and aeroelasticity. Progress in Aerospace Sciences 2010, 46, 284–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sane, SP. The aerodynamics of insect flight. Journal of Experimental Biology 2003, 206, 4191–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson MH, Götz KG. The wake dynamics and flight forces of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Experimental Biology 1996, 199, 2085–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson MH, Lehmann FO, Götz KG. The active control of wing rotation by Drosophila. Journal of Experimental Biology 1993, 182, 173–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seifert, J. A review of the Magnus effect in aeronautics. Progress in Aerospace Sciences. 2012, 55, 17–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crall JD, Ravi S, Mountcastle AM, Combes SA. Bumblebee flight performance in cluttered environments: effects of obstacle orientation, body size and acceleration. The Journal of Experimental Biology 2015, 218, 2728–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willmott AP, Ellington CP. The mechanics of flight in the hawkmoth Manducasexta I. Kinematics of hovering and forward flight. Journal of Experimental Biology 1997, 200, 2705–22. [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi, L. Lift and drag evaluation in translating and rotating non-inertial systems. Journal of Fluids and Structures 2005, 20, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumaru PT, Dimotakis PE. The lift of a cylinder executing rotary motions in a uniform flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 1993, 255, 1–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboomen, S. Experimental study of rotational lift production under insect flapping wing conditions for different wing section profiles. Master Thesis, Graduate School of Science and Technology, Keio University, Japan, September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson T, Isaac K. Aerodynamics of Flapping and Plunging Wings using Particle Image Velocimetry Measurements. In 47th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting including The New Horizons Forum and Aerospace Exposition 2009 (p. 1271.

- Stalnov O, Ben-Gida H, Kirchhefer AJ, Guglielmo CG, Kopp GA, Liberzon A, Gurka R. On the estimation of time dependent lift of a European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) during flapping flight. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0134582. [Google Scholar]

- Noca, F. On the evaluation of time-dependent fluid-dynamic forces on bluff bodies. California Institute of Technology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Krish P Thiagarajan and Armin W Troesch. On the use of various contour shapes for evaluating circulation from PIV data, 13th Australasian Fluid Mechanics Conference, Monash University, 1998.

| Laser | Tracer particles | High speed camera | Lens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nd : YAG Laser | Nylon 12 (5g) | Photoron Fastcam SA3 (60 frames per second) | Micro-Nikkor 55 mm f / 2.8 |

| Numerical schemes | Used option |

|---|---|

| ddtSchemes | Euler |

| gradSchemes | Gauss linear |

| divSchemes | Gauss upwind |

| interpolationSchemes | Linear |

| snGradSchemes | Limited 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).