1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer was the third most common newly diagnosed cancer (9.6% of all cases; after lung and breast cancer) and second by the number of cancer deaths (9.3%; after lung cancer) worldwide in 2022 [

1]. In the Republic of Croatia, it was a most common cancer by incidence, and second by mortality (after lung cancer) among all cancers [

2]. According to the estimates of the European Cancer Information System for 2022, among the 27 countries of the European Union (EU), Croatia ranks 4th in the incidence and 1nd in mortality of colorectal cancer [

3]. The 5-year net survival from the CONCORD-3 study also ranks Croatia at the bottom end of EU countries (51.2% for colon cancer and 48.2% for rectal cancer for patients diagnosed in 2010-2014 period) [

3,

4]. Beside health related impact, the colorectal cancer is also having a high economic burden, with the estimated annual costs of 24 billion

$ in USA and 19 billion € in Europe [

5,

6].

Among all cancer sites, some can be diagnosed early with regular screening programmes, and even in precancerous lesions. Colorectal cancer is among this type of cancers, with the range of possible screening tests, such as stool tests-faecal occult blood test (FOBT) and faecal immunochemical test (FIT), colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and other tests (blood-based DNA test, double-contrast barium enema, etc.) [

7]. The screening tests could potentially lead to a better clinical outcomes and patient diagnosis at an earlier cancer stage. In Netherlands, the introduction of a national FIT screening test increased percentage of colorectal patients diagnosed at Stage I from 15% without screening to 48% after screening [

8].

In the European Union, 20 member states had a population-based screening programme for colorectal cancer in 2020 [

9]. Unfortunately, coverage of the target population for colorectal cancer screening is uneven in the EU, ranging from 20% to 80%. The participation rates depend, among other things, on the used screening test, where participation is higher in the countries which used FIT screening test [

10]. In November 2022, Council of the European Union issued recommendation for a new EU approach on cancer screening and suggests FIT as a preferred screening test for colorectal cancer screening [

11].

Due to many available screening tests, certain studies have compared available screening options to find a most cost-effective solution. According to available systematic reviews, most of the studies concluded that screening techniques were cost-effective compared with no-screening [

12,

13]. Certain studies also compared different screening methods on a national level. In Austria, Jahn et al. compared benefits and cost-effectiveness of four strategies (no screening, annual FIT for age 40-75, annual gFOBT for age 40-75 and 10-yearly colonoscopy for age 50-70) and concluded that annual FIT or 10-yearly colonoscopy are most effective [

14]. Study for a Basque county in Spain concluded that current screening programme, i.e., biannual FIT, is dominant compared to no screening (increasing life expectancy and adding savings to the budget). The cost-effectiveness of FIT versus g-FOBT, resulting in cost savings and quality-adjusted life years gains, was proven in UK setting [

15].

The aim of this study is to analyse costs of colorectal cancer treatment and screening and compare three screening scenarios in Croatia: no screening, biannual gFOBT test for age 50-74 and biannual FIT test for person aged 50-74 years.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources of Data

The data for this study was obtained from the three main sources: Croatian National Cancer Registry, Croatian National Colorectal Cancer Screening Program Registry (short title National Preventive Program, NPP) and CHIF Claims Database. Firstly, Croatian National Cancer Registry, from the Croatian Institute of Public Health, collects data about all new cancer cases in Croatia since 1962. Registration of each case contains very detailed information, including information about the date of diagnosis, disease stage, cancer topography and morphology, demographic patient data (e.g.

, date of birth, sex, date of death, …). The data sources for cancer registration are hospital discharge notifications called

“Onco type forms

”, outpatient

“Malignant neoplasm notification

” and copies of the histological/cytological findings [

2].

Secondly, National Colorectal Cancer Screening Program Registry collects relevant data for the organized population screening program in Croatia. The main indicators include rate of compliance, number of persons with positive gFOBT, number of patients invited to colonoscopy and number of colonoscopies performed, number of CRC and polyps detected [

16]. Thirdly, CHIF Claims Database contains various and in-depth information of healthcare utilisation and costs, based on mandatory health insurance and contracts with the providers of healthcare services. For the purpose of this analysis relevant data for the inpatient (hospital) care, outpatient specialist care (specialist care in hospitals), primary care, prescription drugs, orthopaedic devices and sick leaves were retrieved from the database.

This cost-effectiveness analysis estimates costs, life-years gained and number of prevented cancer cases based on three screening methods for colorectal cancer (CRC): no screening, biannual gFOBT test for persons aged 50-74 years and biannual FIT test for persons aged 50-74 years. The model adopts the perspective of the public healthcare budget in Croatia.

2.2. Screening

In the Republic of Croatia, the National Colon Cancer Screening Programme was adopted in 2007. The screening program targets population aged 50-74 years, with cycles every 2 years, and gFOBT test is used for screening purposes [

17]. Persons with positive gFOBT tests are than ordered to colonoscopy.

Croatia is divided into 21 counties among which is the capital City of Zagreb county. In each of them, there is one public health institute in which work a preventive public-health team with county coordinator nominated for the National Screening Program (MD specialist epidemiologist, public health specialist or high educated nurse with public health education). At the national level, a coordinator from the Croatian National Public Health Institute has been nominated by ministry, and all 22 coordinators are members of the Committee for Program Performance. Additionally, an expert Committee for program coordination has also been nominated by the Ministry of Health, consisted of representatives of all specialties included in program, with the main task to evaluate program performance and consult ministry before major decisions.

The coordinators in each public health institute are obliged to ensure performing of reading finding of gFOB test cards, followed by ordering colonoscopy in all positive cases. Coordinators additionally supervise the collection of structured data on colonoscopic diagnosis, pathohistologic findings, cancers and polyps, and keep records about tests performed in each person within web-based CRC screening registry. There are also dedicated nurses from hospitals where colonoscopy is performed who remind colonoscopist to finish finding after pathohistological findings and give recommendation for future colonoscopy control. The completeness of this data ensures that, in future cycles, people with newly diagnosed CRC and polyps of moderate or high grade are excluded from screening. Colonoscopies are done in colonoscopy units (38 of them in Croatia) by at least one well trained and experienced gastroenterologist colonoscopists.

The web-based CRC screening registry enables generating pre-defined reports and monitoring of key screening indicators, such as: uptake to invitation letter (compliance), uptake for FOBT, number of persons who correctly applied specimens on cards, number of persons with positive FOBT, number and percentage of patients invited to colonoscopy (out of positives), number of colonoscopies performed, number of patients where CRC is diagnosed, number of patients where polyp (polyps) was detected, number of patients where other disease was found (diverticula, inflammatory bowel diseases, haemorrhoids etc.).

In order to participate in the screening, each invited citizen has to send a stool specimen on 3 test cards (each with 4 windows) by prepaid mail to the institute for further analysis. The FOBT is performed by guaiac-based HemoGnost (Biognost) card test (detection limit: 0.252 0.348 mg hemoglobin/g of stool). Cards are designed for easy mailing, with a space to write the name of the participant and the date of fecal sampling. The test does not include dietary restrictions if used in population screening, except large amounts of supplemental vitamin C (>250 mg/d). In order to encourage people to take the test, printed strip-form explained procedure is on the back of the manufacturer’s instruction.

2.3. Croatian Healthcare System

In Croatia, healthcare insurance is compulsory and every Croatian citizen should have a mandatory insurance. The only provider of this type of health insurance is Croatian Health Insurance Fund (CHIF) and approximately 99% of population is covered by the mandatory insurance [

18]. CHIF is also the only purchaser of the publicly funded health services and for insured persons insurance covers, among others, the cost of health services, pharmaceuticals, medical devices and sick leave compensations. Croatia has a wide benefit package and it has defined only negative list what is not covered by CHIF in Mandatory Health Care Act. However, patients must contribute for part of the cost of health services (participation) and there are exemptions from co-payments for vulnerable population groups (like patients with malignant diseases). CHIF is contracting the provision of different health services with public and private providers on all levels of care and has different models of payments for different levels of care and specialities.

In primary health care, for General Practice (GP) there is a combined model of care that is comprised of fixed amount (salary and operating costs and capitation) and variable part for services provided (fee for service), Key Performance Indicators and Quality Indicators and Additional fund (for preventive care, group practice and other). There are also invoices for primary laboratory care (out of capitation), pharmacy services and home nursing that are payed fee for service with defined Diagnostic Therapeutic Procedures (DTPs) and caps. Primary health care has a gate-keeping role and specialist care (outpatient and in-patient on second and third healthcare level) is available only with referral (except in emergency).

For secondary outpatient care, CHIF has contracts with different providers (hospitals, health centres, policlinics and private practises) which are mostly publicly owned institutions. Tertiary and inpatient care is contracted with different hospitals. Hospitals are paid by global budgets and provide the invoices as a reporting mechanism. Other contracted providers are payed for specialist care services as a fee for service with defined DTPs and a cap. The model of payment for acute hospitalizations is activity - based Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs, modified version of the Australian Refined-DRG system version 5.2.). For chronic care, rehabilitation and palliative care, the model of payment is by Day of Hospital Treatment (DHT). Prices are determined by CHIF after consultations with professional associations and public consultations.

Pharmaceuticals/drugs/medicines provided by receipt are defined on the basic (no co-payment) and additional list (with co-payment) of medicines. Pharmaceuticals that are applied in inpatient care are covered by DRGs, except for the especially expensive drugs that are defined on the List of expensive drugs and are payed to hospitals additionally above the contracted cap. The financial compensation for sick leave is provided by CHIF, but only after 42 days. The first 42 days of sick leave are payed by the employer (with some exceptions like pregnancy complications and others).

CHIF also pays for preventive colonoscopy within the National Colon Cancer Screening Programme based on the special contracts with hospitals and a higher price for that type of colonoscopy (preventive DTPs) from a CHIF special financial budget item (prevention of malignant diseases). Croatian Institute of Public Health, which coordinates the program, is funded partly by the Ministry of Health from the state budget and partly from CHIF as a special program with annually defined funds for different activities. County institutes of public health that participate in the program (hemoccult test reading and arranging a colonoscopy for positive tests) are funded by CHIF, based on teams of public health on primary level, and are payed fixed annual amount as a standard team.

2.4. Population

Population for this study consists of new colorectal cancer cases in Croatia in 2014 retrieved from the Croatian National Cancer Registry. The cases for following diagnoses, according to the International Classification of Diseases, were included: C18 (malignant neoplasm of colon), C19 (malignant neoplasm of rectosigmoid junction), C20 (malignant neoplasm of rectum) and C21 (malignant neoplasm of anus and anal canal). According to the retrieved data, there were 3,644 new colon cancer cases in Croatia in 2014 (total population of 3,871,833 in 2021). Three types of patients were excluded from the further analysis. Firstly, patients which were diagnosed from the statistical leaflets about death (221 patients, all these patients have same date of diagnosis and death). Secondly, patients without any medical claim and costs from 2014 until 2019 (16 patients) and thirdly patients for which date of diagnosis in the registry is after date of death (3 patients). Therefore, the analysis included 3,404 patients, out of which 2,089 were eligible age for screening (age 50-74 years).

The average age of colorectal cancer at diagnosis was 68.9 years. There were more male patients in the population (59.3% vs 40.7%) and the age of diagnosis was similar between genders (68.2 for male and 69.8 for female). According to the stage of disease, 21.7% of patients were diagnosed at a localized stage, 43.3% at a regional stage, 14.6% at a distant stage and 20.4% had an unknown stage in the registry. Relatively high percentage of patients with unknown stage at diagnosis is an indicator of insufficient data completeness of the data received by the national cancer registry, as described in its annual reports [

2].

2.5. Costs

Costs for each patient included in the analysis were derived from CHIF Claims Database for the five years following date of diagnosis. Since Croatian National Cancer Registry collects data about disease stage at the diagnosis and does not contain further data about disease stage, the costs of colorectal cancer were also calculated in this way. For example, if patient had a local stage at a diagnosis, all further costs were associated (added) to the total costs for local disease stage. Same rule applies to all disease stages and patients. Regarding calculation of costs per patient, costs in second year are averaged based on number of patients who survived first year of a disease for certain disease stage. Costs in third year are averaged based on number of patients who survived second year of disease for certain disease stage. Same rule applies to the costs for fourth and fifth year.

All claims where one of diagnosis C18-C21 is listed as a main or additional diagnosis were included into analysis. Total costs in five years for 3,404 patients amounted to 44.6 million € (

Table 1). The highest percentage of costs occurred in the first year (52.2%) and decreased each following year. Regarding type of healthcare, highest percentage of costs occurred for inpatient care (50.8%) followed by outpatient care (21.2%) and orthopaedic/medical devices (20.2%). Comparing the costs incurred in the first year following diagnosis with total healthcare expenditures of the Croatian Healthcare Fund in 2014 and 2015 (approximately 3.0 billion € annually), the costs of treating newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients in the first year amounted to 0.8% of total CHIF’s expenditures, representing high burden for the healthcare budget.

Among colorectal cancer stages, the highest percentage of total costs is associated with regional stage (44.8%), followed by distant metastases (22.0%), unknown (17.2%) and local stage (16.0%). Calculation of costs per patient indicates that the highest costs are associated with a distant disease stage (total of 39,802€ per patient in five years), followed by regional stage (16,732€ per patient in five years) (

Table 2). Comparison of costs for all patients and patients at age eligible for screening show that costs are higher for screening eligible patients (average costs of 19,533€ vs 16,897€). The data for both observed groups indicate that distant stage patients have more than 130% higher costs than patients with regional or distant metastases. This emphasises the importance of earlier disease detection not just for medical purpose, but also for lower economic costs.

Calculation of annual costs per patient indicates high economic burden of disease in the first two years since the diagnosis (

Table 2). In the first year, depending on the disease stage, costs represent 29-45% of total costs for five years, while first two years represent 58-67% of total costs. Percentage of costs occurred in the first year is the highest for localized cancer stage and lowest for the distant stage, while in the second year it is highest for distant and lowest for localized stage. Costs for all cancer stages decrease with each year since diagnosis and are higher for patients at age eligible for screening (except for the unknown stage in third, fourth and fifth year).

2.6. Model and Inputs

The model is built on a projection of 10,000 colorectal cancer free patients at age 50 and their health outcomes with related costs in the next five years. Predicted outcomes for five years are costs of treatment, number of new colorectal cancer patients (incidence), number of deaths from colorectal cancer, life-years gained (if patient with cancer is alive, it counts as a 1 life-year) and costs (savings) per life-year gained. Costs and life-years gained were discounted by 3% annually. It was assumed that patients could have an adenoma or an advanced adenoma based on prevalence from the literature survey. Certain percentage of colorectal adenomas progress to advanced adenomas and advanced adenomas progress to colorectal cancer. These transition rates, as well as an incidence of adenomas, were taken into account in the developed natural history model.

Difference in outcomes is derived from the comparison of no screening, gFOBT screening and FIT screening model. The patients could be screened by tests in the first year, following percentage of screening participation rates and colonoscopy participation after unfavourable (positive) screening results. Participation rates in the model are based on the National Colorectal Cancer Screening Program and past screening cycles in Croatia. If patient participated in screening, was positive and undertook colonoscopy, adenomas and advanced adenomas could be detected and removed. The removal of described excrescences decreases future number of new cancer cases and therefor saves lives and costs.

The 5 year relative survival probabilities for each cancer stage differ based on the type of detection (symptomatic and screening, based on Austrian data to unavailability of Croatian data), while cancer stage is based on the Croatian colorectal cancer stage in period 2015-2019 from the Croatian National Cancer Registry (unknown 32%, localized 15%, regional 39% and distant 14%) [

2]. Due to the lack of national transition rates for colorectal cancer, it was assumed that patients stay in the same disease stage throughout five years. The model also used all-cause mortality estimates from the 2010-2012 Croatian life tables [

19]. Screening test characteristics (sensitivity and specificity), as well as an adenoma incidence and transition rates, were obtained from the literature search.

Costs per patients for colorectal cancer were calculated from the insurance claims of the CHIF(

Table 2). Since the model and screening take into account patients in the age group 50-74 years, model was calculated using costs of mentioned group. Regarding costs of tests, they include costs of test itself and costs of screening programme based on current FOBT screening. Costs of screening programme include: a) post, b) education, quality control and marketing, c) public healthcare teams and d) print. For FIT, costs of screening programme additionally include: a) extra post costs (due to different packaging), b) acquisition of equipment and c) additional laboratory staff. Described costs of screening programme were calculated on a patient basis based on the number of patients participating in the programme (i.e.

, total cost of screening programme was divided by number of patients participating in the programme). All inputs and sources are visible in

Table 3.

3. Results

The results of the basic scenario based on Croatian screening participation rates are presented in

Table 4. Both screening strategies, gFOBT and FIT, add life-years, decrease number of newly diagnosed patients, decrease deaths from colorectal cancers and decrease costs compared to no screening option, thus providing higher health outcomes with lower costs. Therefore, both screening options dominate no screening strategy (negative costs per life-year gained, i.e.

, savings per life-year gained). In comparison to gFOBT, screening a cohort of 10,000 individuals age 50 years with FIT is expected to decrease new cancer cases by 2.5, decrease colorectal related cancer deaths by 0.9 and add 2.2 life-years in the first five years after screening. Described health benefits are expected to be achieved with lower economic costs, leading to FIT dominating gFOBT as a preferred screening option. Based on the Croatian eligible population (approximately 1,350,000 persons; 337,500 tested persons), FIT test would, compared to no screening option, decrease new cancer cases by 575, decrease colorectal related cancer deaths by 255 and add 681 life-years in the first five years after screening.

The effectiveness of the screening tests is usually based on the screening participation rate or participation of colonoscopy after positive test. Therefore, in

Table 5, two additional scenarios were taken into account: one where screening participation rate is increased to 50% and one where colonoscopy participation rate is increased to 90%. The potential increase of both participation rates leads to an additional health benefits and economic savings of screening options compared to basic scenario (

Table 5). This shows high future potential of a FIT colorectal cancer screening programme in Croatia.

3.1. Sensitivity Analyses

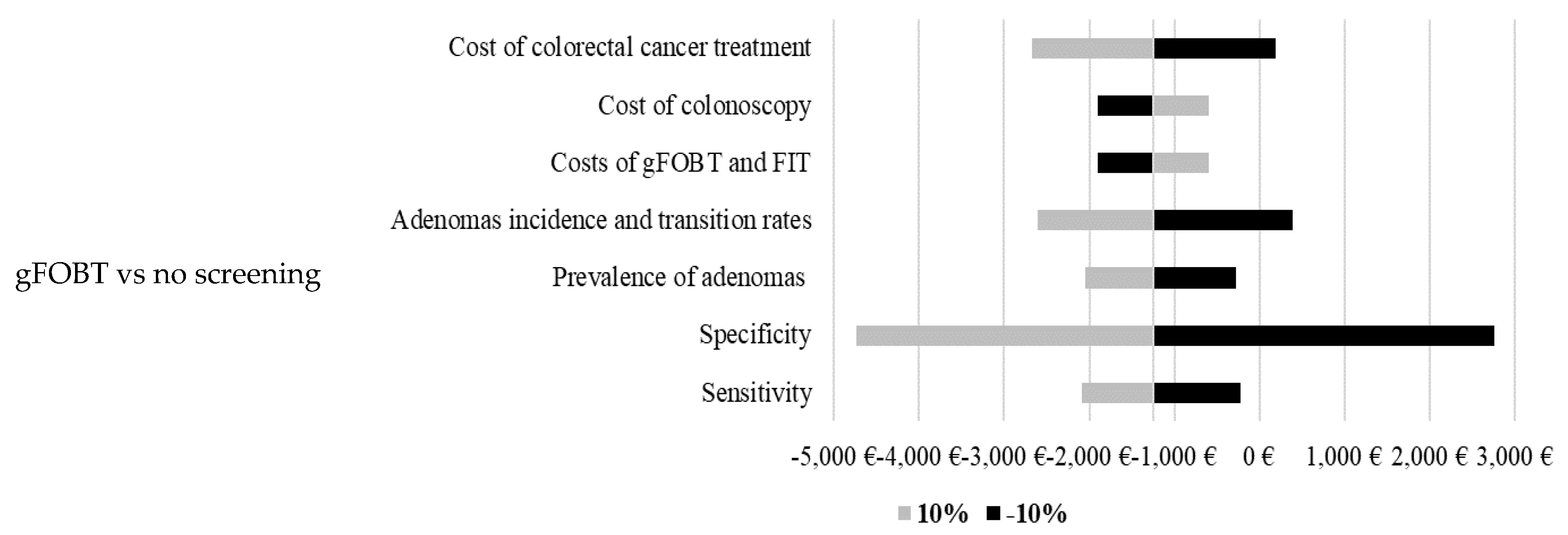

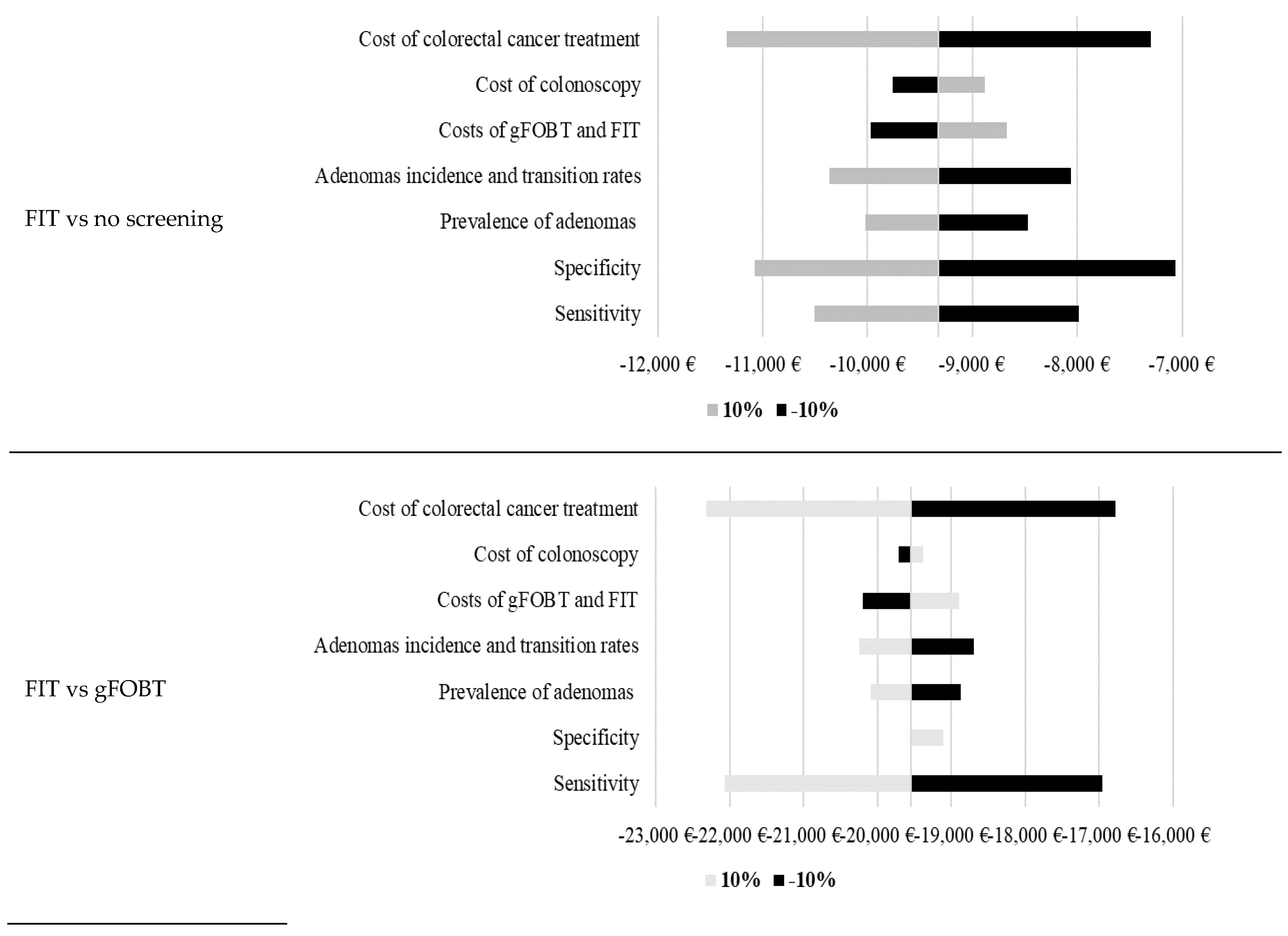

The developed model is based on many inputs. Therefore, sensitivity analyses were conducted to test a robustness of the model (

Figure 1). Results of the calculated sensitivity analyses show high robustness of the model. The highest impact on projected costs per life-year gained was in most models calculated by changing specificity, cost of colorectal cancer treatment and sensitivity.

4. Discussion

This study estimated and analysed health outcomes and costs for the colorectal cancer screening in Croatia. Results indicate high economic costs of colorectal cancer and significantly higher costs per patient for distant disease stage. In order to compare cost-effectiveness of screening options three scenarios were compared: no screening, gFOBT test and FIT test. The results show that gFOBT and FIT, compared to no screening, bring additional health benefits with lower costs (negative costs per life-year gained) and FIT test is expected to be the most cost-effective scenario.

The success of the colorectal cancer screening programme depends on many factors, such as participation of the targeted population and colonoscopy participation rates. Conducted sensitivity analyses in the model indicate that higher screening or colonoscopy participation rates lead to an additional health benefits and costs savings of the national screening programme. Comparison of the Croatian colorectal cancer screening participation and colonoscopy rates with European best case examples shows high future potential for better colorectal prevention and outcomes. For example, Netherlands has a participation rate of the targeted population of 73% and colonoscopy rate of 83%, while Slovenia has a 65% and 92% of these rates [

8]. The importance of higher participation rates is recognised in Croatia by the National Cancer Control plan for period 2020-2030. According to the plan, aim of the National Colon Cancer Screening Programme is to increase participation rates of targeted population at 60% and decrease mortality by 25% until 2030 [

28].

Based on RCTs and model studies, biennial FIT/gFOBT, single and 5-yearly FS, and 10-yearly colonoscopy screening significantly reduces CRC-specific mortality [

29]. Study includes the analysis of two screening strategies the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) every 2 years and annual FIT. Direct comparison between strategies showed 107% higher incremental costs and 46% higher effects in annual FIT test strategy compared to biennial FIT [

30]. In our study the data for both observed groups indicate that distant stage patients have more than 130% higher costs than patients with regional or distant metasases. This emphasises the importance of earlier disease detection not just for medical purpose, but also for lower economic costs.Even with higher screening uptake, triennial blood-based screening, with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services specified minimum performance sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 90%, was not projected to be cost-effective compared with established strategies for colorectal cancer screening [

31]. Real-world cost-effectiveness rewiev analysis as an important type of research to inform patients, providers, and policy makers about the actual cost and effectiveness of new cancer treatments and interventions was done by Barr et al. They showed that the estimate of cost effectiveness without the context of uncertainty, decisions may not be well informed [

32]. Among newly diagnosed patients, costs peaked in the first year (men: €16,375–16,450; women: €10,071–13,250) and declined in later years, with no clear age-related pattern. In our study we got similar results for all patient subgroups, but most expensive was first year trestment for patients with distant metastases age 50-74 with costs of €14,086, as well as in all patients group with distant metastases (€11,460). The data in Germany study showed end-of-life costs were much higher than initial care, remained elevated years before death, and peaked in the final year, varying significantly by sex and age (<70: men €34,351, women €31,417; ≥70: men €14,463, women €9,930) [

33]. In our study we did not analize separated end-of-life costs. Beside better health outcomes, highly successful and effective colorectal screening programmes have a high possibility of significant cost reduction due to the much higher detection of cancers in localized stage (Netherlands: 48% of localized cancer after screening vs 17% before screening, Slovenia: 49% localized patients). Based on described examples, higher participation rates in Croatia for the colorectal cancer screening have a high potential in decreasing costs, saving lives and preventing further cancer cases.

Our analysis is limited by the fact that, due to the unavailability of Croatian data, many inputs are collected from the foreign literature and data. If possible, meta analyses were used to bridge this data gap, thus limiting potential bias. Additional limitation is using five years in the model to project health outcomes and costs. Certain costs of the National Colon Cancer Screening Programme, such as an IT support, could not be adequately estimated and were therefor not included in the model.

The worldwide burden of colorectal cancer is expected to increase to 3.2 million new cases (63% increase) and 1.6. million deaths (73%) by 2040 [

34]. Successful implementation and efficiency of the possible screening options could therefor prevent additional new cancer cases and death from the disease. In Croatia, introduction of FIT screening option in a National Colon Cancer Screening Programme has a potential to increase screening participation rates, improve health outcomes and decrease related health costs and economic burden of colorectal cancer.

5. Conclusions

Theis study results showed that costs per patient five years after diagnosis for advanced cancer treatment are 2,4 times higher than costs for non-advanced cases. The implemented model shows that screening options for colorectal cancer provide better health outcomes at lower costs compared to no screening. FIT is considered the preferred screening option due to its better sensitivity and better health outcomes and lower treatment costs compared to gFOBT. Since the introduction of FIT screening instead of gFOBT could increase the proportion of people screened with the screening test, it would improve health outcomes and reduce health costs and the economic burden associated with colorectal cancer in Croatia. Further efforts are needed to raise awareness of this cancer prevention possibilities, not just from medical and ethical aspects, but also important financial aspects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and N.A.; methodology, A.C.; validation, N.A., I.B. and N.Lj.; formal analysis, A.C. and N.A.; investigation, A.C.; resources, N.A., I.B., M.V. and M.Š.; data curation, N.A. and M.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and N.A.; writing—review and editing, I.B., M.V., and M.Š.; visualization, A.C.; supervision, N.A., N.Lj. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Croatian Society of Gastroenterology.

Institutional Review Board Statement and ethical approval

The research was conducted with the approval of the Ministry of Health, Croatian Institute of Public Health and Croatian Health Insurance Fund. All obtained patient-level data were anonymous.The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Croatian Institute of Public Health.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was not needed because epidemiologic and costs data was used.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Croatian Institute of Public Health and Croatian Health Insurance Fund for providing the data to conduct the analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| gFOBT |

guaiac fecal occult blood test |

| FIT |

fecal immunochemical test |

| CRC |

colorectal cancer |

| CHIF |

Croatian Health Insurance Fund |

| CIPH |

Croatian Institute of Public Health |

| CNCCSR |

Croatian National Colorectal Cancer Screening Registry |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Cancer Observatory. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/en. Accessed 2024 Jun 26.

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Cancer incidence in Croatia 2022. Zagreb: Croatian Institute of Public Health; 2025. Available from: https://www.hzjz.hr/periodicne-publikacije/incidencija-raka-u-hrvatskoj-u-2022-godini/. Accessed 2024 Apr 7.

- European Cancer Information System. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in 2022, for all countries. Brussels: European Cancer Information System; 2024. Available from: https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/explorer.php?$0-0 Accessed 2025 n 26.

- Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. The Lancet 2018; 391(10125): 1023-1075.

- National Cancer Institute. Financial Burden of Cancer Care. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2024. Available from: https://progressreport.cancer.gov/after/economic_burden. Accessed 2024 Jun 26.

- Hofmarcher T, Lindgren, P. The Cost of Cancers of the Digestive System in Europe. Lund: The Swedish Institute for Health Economics; 2020. Available from: https://ihe.se/en/rapport/cost-of-cancers-of-the-digestive-system/. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- National Cancer Institute. Screening Tests to Detect Colorectal Cancer and Polyps. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2024. Availavle from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/colorectal/screening-fact-sheet. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- Digestive Cancers Europe. White Paper: Colorectal Screening in Europe. Brussels: Digestive Cancers Europe; 2019. Available from: https://www.digestivecancers.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/466-Document-DiCEWhitePaper2019.pdf. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- European Commission. Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan. Brussels, European Commission; 2022. Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-02/eu_cancer-plan_en_0.pdf. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- Ponti A, Anttila A, Ronco G, Senore C. Cancer Screening in the European Union, Report on the implementation of the Council Recommendation on cancer screening. Brussels, European Commission; 2017. Available from: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/911ecf9b-0ae2-4879-93e6-b750420e9dc0_en. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation on strengthening prevention through early detection: A new EU approach on cancer screening replacing Council Recommendation 2003/878/EC. Brussels: Council of the European Union. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32022H1213%2801%29. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- Khalili F, Najafi B, Mansour-Ghanaei F et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2020; 13: 1499-1512.

- Ran T, Cheng CY, Misselwitz B et al. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening strategies-a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17(10): 1969-1981.

- Jahn B, Sroczynski G, Bundo M et al. Effectiveness, benefit harm and cost effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening in Austria. BMC Gastroenterol 2019; 19(1): 1-13.

- Murphy J, Halloran S, Gray A. Cost-effectiveness of the fecal immunochemical test at a range of positivity thresholds compared with the guaiac fecal occult blood test in the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening Programme in England. BMJ open 2017; 7(10): e017186.

- Katičić M, Antoljak N, Kujundžić M et al. Results of national colorectal cancer screening program in Croatia (2007-2011). World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(32): 4300-4307.

- Antoljak N, Šekerija M. Epidemiology and Screening of Colorectal Cancer. Libri Oncology 2013; 41(1-3): 3-8.

- Džakula A, Voćanec D, Banadinović M et al. Croatia: Health system summary 2022. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2022. Available from: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/croatia-health-system-summary. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Life tables for the Republic of Croatia, 2010-2012. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Available from: https://podaci.dzs.hr/media/slmfoiaf/tablica-mortaliteta-2014.pdf. Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- Hirai HW, Tsoi KKF, Chan JYC et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: fecal occult blood tests show lower colorectal cancer detection rates in the proximal colon in colonoscopy-verified diagnostic studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43(7): 755-764.

- Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB et al. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(9): 659-669.

- Launois R, Le Moine JG, Uzzan B et al. Systematic review and bivariate/HSROC random-effect meta-analysis of immunochemical and guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer screening. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26(9): 978-989.

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(14): 1287-1297.

- Wong MC, Huang J, Huang JL et al. Global prevalence of colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18(3): 553-561.

- Brenner H, Altenhofen L, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Incidence of Colorectal Adenomas: Birth Cohort Analysis among 4.3 Million Participants of Screening Colonoscopy. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2014; 23(9): 1920-1927.

- Wieszczy P, Kaminski MF, Løberg M et al. Estimation of overdiagnosis in colorectal cancer screening with sigmoidoscopy and fecal occult blood testing: comparison of simulation models. BMJ open 2021; 11(4): e042158.

- Croatian Health Insurance Fund. Šifrarnici koje koristi HZZO, DTP postupci u NPP. Zagreb: Croatian Health Insurance Fund; 2024. Available from: https://hzzo.hr/hzzo-za-partnere/sifrarnici-hzzo-0. Accessed 2024 Feb 24.

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia. Nacionalni strateški okvir protiv raka do 2030. Zagreb: Official Gazette of the Republic of Croatia. Available from: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2020_12_141_2728.html.Accessed 2024 Jun 28.

- Zheng, S.; Schrijvers, J.J.A.; Greuter, M.J.W.; Kats-Ugurlu, G.; Lu, W.; de Bock, G.H. Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening on All-Cause and CRC-Specific Mortality Reduction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babela R, Orsagh A, Ricova J, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Csanadi M, De Koning H, Reckova M. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening in Slovakia. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2022 Sep 1;31(5):415-421. Epub 2021 Nov 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Puttelaar, R; De Lima P.N.; Knudsen A.B. ; Rutter C.M.; Kuntz K.M.; De Jonge L. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer Screening With a Blood Test That Meets the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Coverage Decision. Gastroenterology. 2024 Jul;167(2):368-377. Epub 2024 Mar 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barr, H.K.; Guggenbickler, A.M.; Hoch, J.S.; Dewa, C.S. Real-World Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: How Much Uncertainty Is in the Results? Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 4078–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heisser, T.; Simon, A.; Hapfelmeier, J.; Hoffmeister, M.; Brenner, H. Treatment Costs of Colorectal Cancer by Sex and Age: Population-Based Study on Health Insurance Data from Germany. Cancers 2022, 14, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. BMJ 2023, 72: 338-344.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).