1. Introduction

Multimodal global optimization of numerical functions may be thought of as the task of finding all their global optimizers (here we will concentrate on minimization problems without constraints, apart from the natural one corresponding to the definition of the domain of each cost function) and respective optimal value - the most challenging cases correspond to functions with multiple global and local optima. In this fashion, when working with multimodal problems, at least two issues have to be taken into account: the precise location of all optimizers corresponding to a given global optimum and the determination of the exact value of the global optimum (here global minimum value). However, complications may arise when practical applications are tackled, mainly due to the absence of knowledge about the overall geometry of cost functions, their analytical properties and, frequently, the computational cost of evaluation. In any circumstance, even when it is possible to find a subset of global minimizers, in general it is hard to decide whether the set is complete or not, that is, have we found all global minimizers?

This state of affairs becomes even worse due to limitations on the number of function evaluations available for solving problems found in practice, often because they depend on physical processes or long simulations until obtaining the final objective function value. Besides, although many test problems contain a large number of local optima, featuring very complicated landscapes and many suboptimal attraction basins, it is not sensible to expect that concrete applications be easier to treat.

In view of such immense barriers, what to do if it is infeasible to find the global minimum?

At least two strategies may be used:

- To spread the search over the whole optimization domain, trying to find as many optimizers (local or global) as possible;

- Determining basins of attraction with more potential to contain global optima, and exploring these specific regions.

Considering that available resources are always limited in practice, devising non-uniform, smart strategies to identify “promising” regions seems to be the best way to go.

In this work the strategy will be to concentrate on the most promising regions, assuming that the quality of starting points is directly related to their respective cost function values. To obtain this effect it is necessary to use the capability of space-filling curves of visiting all points of a given domain contained in . After sampling a pre-established number of points, they are sorted with basis on their cost function values and submitted to some criteria, in order to select a tiny number that will finally form the set of seeds used when starting the overall optimization process. The criteria used here consist of two main complementary selection processes, namely, collecting a predetermined number of best sampled points (lower cost function values) and a kind of attraction basin estimation, by means of representatives also featuring low CF values and geometrically dispersed. The results of such a procedure are very interesting, in the sense that they have shown to be as effective as population-based algorithms in multimodal problems presenting multiple global optima, in which candidate points interact during the whole simulation, what is supposed to be an advantage over the fully independent runs of multistart methods. Perhaps the hidden compensation be in the “omnipresence” of space-filling curves in cost function domains, also reaching points with irrational coordinates - by definition an unfeasible feature for present day digital computers, that are unable to exactly represent even the square root of 2, for instance.

Returning to the general context, the present proposal works very well when associated with evolutionary algorithms because they seem to be especially adequate for solving multimodal problems as they are able to learn from runtime experience and enable the integration of gained information during simulations, changing their behavior according to previously designed rules. They have been synthesized so as to be able to globally search the whole definition domain, mainly to cope with highly multimodal problems. The large attention they have received may also be justified by their potential to utilize parallel processing computational devices and the appealing inspiration in Nature, be it related to biology, physics, or any other branch. It is not difficult to infer that the key to success when tackling multimodal problem is to maintain several independent search threads, be them sequential or parallel in time, interacting (as in population-based paradigms) or decoupled (as in multistart methods) - whenever the search threads start from and operate in different basins of attraction, several distinct optimizers tend to be found. Of course such results are welcome when multiple global minimizers are being investigated - even in common global optimization problems (finding only one minimizer is considered satisfactory), diverse optimization threads may help in the majority of real-world settings. As noted above, concurrent evolution of several candidate solutions as found in many evolutionary methods may be implemented on non-parallel equipment. Accordingly, many population-based methods typically use concurrency. In any event, nowadays, evaluation tests are normally synthesized by establishing a maximum number of cost function evaluations available to entire optimization runs, taking into account that processing time is a limited resource.

2. HQF ASA

It is true that some simulated annealing implementations present low speed of convergence [

10,

11]. However, it is possible to overcome most limitations of original annealing algorithms, as demonstrated by ASA (Adaptive Simulated Annealing), a sophisticated and effective global optimization method [

9]. ASA algorithm is adequate for use in applications involving cost functions with complex “landscapes”, like the ones found in machine learning or model fitting problems, for example. Moreover, ASA is an alternative to other global optimization systems, according to the published results, that demonstrate its good quality [

14]. Similarly to many other stochastic global optimization algorithms, sometimes it may behave in a somewhat inconvenient way as, for example, to stay for large periods without significant improvement.

When speaking of simulated annealing implementations, that behavior is mainly due to the way the “cooling” schedule is designed, whose speed is limited by the characteristics of probability density functions used to generate new candidate points. Accordingly, when using Boltzmann annealing, the temperature is decreased at a maximum rate of

. On the other hand, in fast annealing the schedule becomes

, in order to guarantee convergence with probability, what results in a more agile schedule. ASA presents an even faster default scheme, given by

where

is a user-defined constant, thanks to its more efficient generating distribution. Not surprisingly, temperatures evolve independently for each parametric dimension. Furthermore, it is possible for the user to accelerate the whole process by using

simulated quenching, that is,

where is the quenching parameter corresponding to dimension i.

The activation of quenching mechanisms results in greater agility, but convergence to a global optimum may not occur anymore [

9]. However, such a procedure may be advisable for high-dimensional parameter spaces, in settings with modest computational resources.

In order to deal with these potential episodes of slow performance a fuzzy controller was added to the dynamics of ASA (named Fuzzy ASA) some years ago and it is possible to observe that, when slow convergence is detected, the control mechanisms adapt automatically and reduce the degree of manual parameter tuning, without changing the core ASA code and the final result has been very satisfactory ever since [

14].

Recently, a new improvement [

18] was proposed: HQF ASA combines quantum and thermal annealing, again without interference with ASA code, will be used to evaluate the present method, to be explained below.

HQF ASA aims to activate, in an independent way, the homotopic annealing process coupled to the central mechanisms of Fuzzy ASA, which may be viewed as the usual thermal annealing. This type of dynamics showed itself feasible by operating outside the dynamics of ASA, actuating before objective function evaluations and using the number of evaluations as another kind of annealing parameter. In this manner, the initial cost function is reshaped, making it easier to discover better attraction regions. In terms of implementation, the corresponding code may be placed inside the module that calculates the cost function.

The underlying idea for the insertion of another type of annealing dynamics is to give the simultaneous classical annealing process more favorable conditions to locate more regions nearby global minima. This is convenient considering that the homotopic process rises the deepest (global) minima in earlier phases, making it easier to detect promising subdomains - it is possible to infer that global optimization may be seen as a geometric process and very deep minima are hard to find, mainly when they occur in relatively tiny parts of the entire domain [

18].

It may be worth to better understand the simplicity of landcape homotopic annealing in terms of implementation. To that end, some significant aspects of the paradigm may be useful:

The homotopic annealing changing rate is driven by the number of function evaluations, that is, the timebase of HA is the number of function evaluations along one session.

The code should be decoupled from the principal optimization device and tightly linked to the cost function. All tests used dynamic linking libraries on the Linux operating system.

It may be used with any technique supporting dynamic deformation of cost functions, as original ASA does. In other words, the method should not get “misled” with flexible landscapes.

The practical realization requires one accumulator for the number of cost function evaluations and a criterion for triggering the deformation steps - in this work, simple integer multiples of a certain previously established natural number were used to advance the geometric changes. Hence, at each cost function activation a decision is taken, relatively to change in the current function - its complexity is variable.

Simulated annealing algorithms originated from the work of N. Metropolis and others [

13], normally referred to as Monte Carlo techniques - it is based on three distinguished parts, that are very influential on the final performance: two distinct probability density functions, used in the generation of new candidate points and in the acceptance/rejection of generated points, and a schedule, determining the dynamics of temperature evolution in run-time. Similar to many others, the standard approach is to synthesize a starting point, selected according to some criteria, setting the initial temperature so that the configuration space may be intensively explored. Then, additional candidates are generated by means of the specific PDF and accepted or rejected, according to the acceptance PDF. In case of acceptance, the candidate point changes its status to current base point. Along the execution, temperatures have their values lowered, reducing the acceptance rate for generated points with greater cost than that of the current base candidate. Despite this, the probability of going uphill is not zero, making it possible to avoid being caught in local minima.

3. Space-Filling Curves

3.1. General Considerations and Application in Optimization

Many approaches for global optimization based on space-filling curves have been recently proposed in the literature [

2,

3,

8,

12,

21]. Typically, the functions under study in these contributions have some regularity requirements, such as being differentiable or obeying the Lipschitz condition. In this fashion, whenever those properties are not satisfied, or it is not possible to prove they are, the problem under study cannot use that specific method. Therefore, it is reasonable to search for some way of coping with such limitations too. Moreover, a scenario that may happen is related to the poor precision obtained when using certain methods and the domain dimension is high - this is associated to the difficulty of minimizing the resulting 1-dimensional auxiliary functions which exhibit many local minima and very irregular graphs.

Accordingly, certain methods are not able to cope with such a hard context, and the approaches have been, in some cases, considered not adequate. This happens due to how the multidimensional domain is “visited” and to the characteristics of the one-dimensional minimization process applied to the modified function. In order to obtain good results, approaches based on space-filling curves should satisfy some minimal conditions:

To obtain good approximations of space-filling curves whose images are, or contain, compact domains of functions under processing

To employ minimization algorithms able to find acceptable approximations to minimizers of the real valued composed function, featuring the same extremes as the original mapping, global optima included.

However, these conditions are hard to obtain and, in the past, they were not very successful. In [

2,

3] interesting algorithms are described, but the results concentrate mainly on low dimensional spaces. Moreover, objective functions should satisfy Lipschitz constraints, requisite that may not be easy to assure in several cases. Also, issues linked to suitability of the filling of the actual multidimensional domain must be addressed. For instance, one helpful technique that may be used to verify the occurence of “forgotten” regions is to project the points of the space-filling curve in the subspace spanned by vectors corresponding to directions presenting larger variance, using principal component analysis.

In this fashion, although there are several types of SFCs able to cover multidimensional domains, their numerical approximations may exhibit spatial gaps due to truncation or limitations of current digital computers - this behavior becomes more evident as the number of dimensions increases. For the sake of finding space-filling curves capable of overcoming such inconvenient characteristics, measure-preserving transformations and results of General Topology and Ergodic Theory may be used [

1,

4,

5].

In summary, in [

16] many evidences of the potential of space-filling curves when applied to global optimization problems are shown. Also, in [

17] important applications involving multimodal global optimization indicate their relevance when used as deterministic initializers - these findings were fundamental in the decision

to proceed further and construct a general method to tackle multimodal global optimization problems, resulting in the present work. In this fashion although the cited reference describes an innovative solution for a very significant problem in game theory, it is a

specific example of the general method to be presented below, which represents an original contribution.

3.2. Definition of Schoenberg-Steinhaus Space-Filling Curves [20]

In this subsection the formulae defining Schoenberg-Steinhaus curves are discussed, along with complementary information. The definition for the 2-dimensional Schoenberg SFC needs some preliminary components, like the function , defined in (and ) as

Definition 1.

withThe formulae for the coordinate functions in

are

Definition 2.

(2-dimensional Schoenberg SFC)

andThe resulting curve

is a 2-dimensional SFC showing good behavior in numerical computations, and the coordinate functions

and

will be used to get the n-dimensional Schoenberg-Steinhaus SFC.

When constructing higher-dimensional SFCs, certain results are fundamental.

Before stating them, however, it is necessary to present some definitions.

Definition 3.

A function is uniformly distributed with respect to the Lebesgue measure if, for any (Lebesgue) measurable set , we have

where is the Lebesgue measure in the real line.

Definition 4.

n measurable functions are stochastically independent with respect to Lebesgue measure if, for any n measurable sets ,

Theorem 1.

(H. Steinhaus) [20] If are continuous, non-constant and stochastically independent with respect to the Lebesgue measure, then

is a space-filling curve.

Theorem 2. [20] If is (Lebesgue) measure-preserving and onto, then its coordinate functions are uniformly distributed and stochastically independent.

Considering Theorem 1 and the properties of Schoenberg SFC, it is clear that its coordinate functions can be used to obtain higher-dimensional SFCs with coordinates

where

that are not constant, being continuous and stochastically independent.

According to [

20], the extension of this idea to

-dimensional SFCs is due to Hugo Steinhaus. Therefore, the curve defined by the equation set (

7) is referred to (in this article) as the Schoenberg-Steinhaus space-filling curve.

It is worth highlighting that despite Steinhaus’ theorem is stated only for continuous functions, it is also valid for surjective (over [0,1]), piecewise continuous coordinate functions. In this fashion, the following result is true.

Theorem 3.

(extended Steinhaus) If are piecewise continuous, surjective, non-constant and stochastically independent with respect to the Lebesgue measure, then

is a space-filling curve.

4. Proposed Method Using Schoenberg-Steinhaus Space-Filling Curves

In this section it is described the algorithm for obtaining a set of initializers aimed at enhancing the power of GO algorithms in their search for all global minimizers of a given function. The overall task of global optimization is here divided into two clearly delimited phases, namely, initialization/preprocessing by means of Schoenberg-Steinhaus space-filling curves (SFCs) and posterior minimization with HQF ASA. The first role is played by the deterministic sampling of objective function values in compact domains by means of an adjustable discretization mechanism applied to Schoenberg-Steinhaus SFCs. The last phase is played by the GO algorithm of choice, receptor of the set of initializers.

Therefore, the overall optimization process begins by searching for promising starting points that will be delivered to the main minimization algorithm - in this work it happens to be HQF ASA, but the general idea is valid for any global optimization method, including the population-based ones.

The number of seeds is adjustable and they should be set according to the dimension of the problem - more dimensions, more seeds, as expected. It is also important to properly select the number of function evaluations to be spent in the exploratory part - surprisingly, more dimensions may not ask for more function evaluations and, in several occasions, with less evaluations we obtain better initial points.

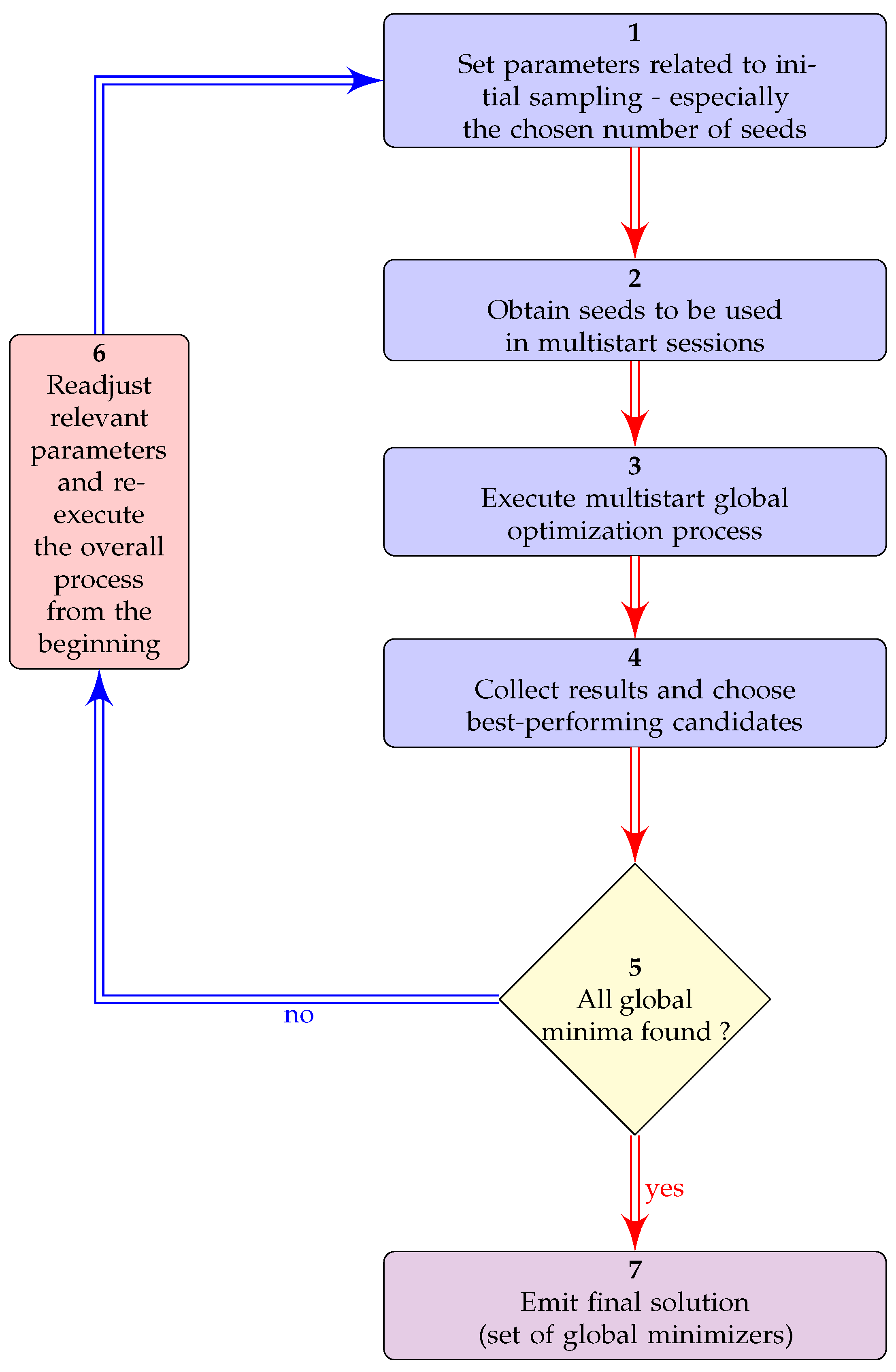

The general algorithm for global optimization can be stated as:

Set initial sampling parameters (discretization granularity, number of seeds to obtain, and so on). Naturally, the number of seeds should be greater than or equal to the expected number of global minimizers

-

Obtain the seeds by:

- (a)

Computing a finite number of points on the chosen space-filling curve along with their associated cost function values;

- (b)

Sorting them in increasing order, based on their values, stored during the previous step (ranking);

- (c)

Selecting the subset of points with lower values and, independently, the ones with lower values and isolated points, with minimum preestablished distance from any other, aiming at favoring diversity very early in the seed selection phase. This last subset may be faced as the result of a very simple clustering process, with replacement of elements.

For each point belonging to each subset indicated above, launch the main global minimization process (HQF ASA) using it as the initial seed

Collect results and choose candidates

Decide whether a satisfactory number of global minima has been found

If not, readjust relevant parameters and re-execute the process from the beginning (go to step 2 above)

Emit the results and finish the session

Figure 1 depicts a diagram illustrating the proposed algorithm.

5. Experiment Description and Numerical Results

5.1. General Considerations

From this point on, the adopted test framework will be described and the most important facts about the used functions will be explained, including evaluation criteria, and other information needed for the understanding of the experiments and corresponding results. Basically, the intention is to estimate the effect of the proposed paradigm on the effective performance of the global optimization process over several runs and compare the indices used in the measurements. The cited (positive) effect is to increase the overall number of global minima found, given a fixed number of function evaluations used in each optimization session, and to minimize the number of function evaluations to attain the cited goal. Given a maximum number of function evaluations and a required accuracy level, the general idea is to calculate the percentage of known global optima found over multiple runs, and the number of sessions in which the method was able to reach maximum performance, that is, to find all global minima during a single multistart session, using the set of seeds suggested by the proposed method. In the present work, 2 million samples of Schoenberg-Steinhaus SFCs were used as the basis for finding the seeds needed to validate the method in 2-dimensional regions. Naturally, when domain dimension increases, it is natural to use a higher level of discretization. The discretization is produced by dividing in equal parts and computing the respective points in the path. In addition, it is worth highlighting that only one n-dimensional unitary hypercube needs to be discretized in order to deal with all n-dimensional rectangular domains, that is to say, the computational effort to generate the SFCs is made just once. being them fetched in runtime to arrive at the seeds specific to each function under study. In this manner, it is possible (and advisable) to prestore sets of discretized unitary hypercubes of different spaces.

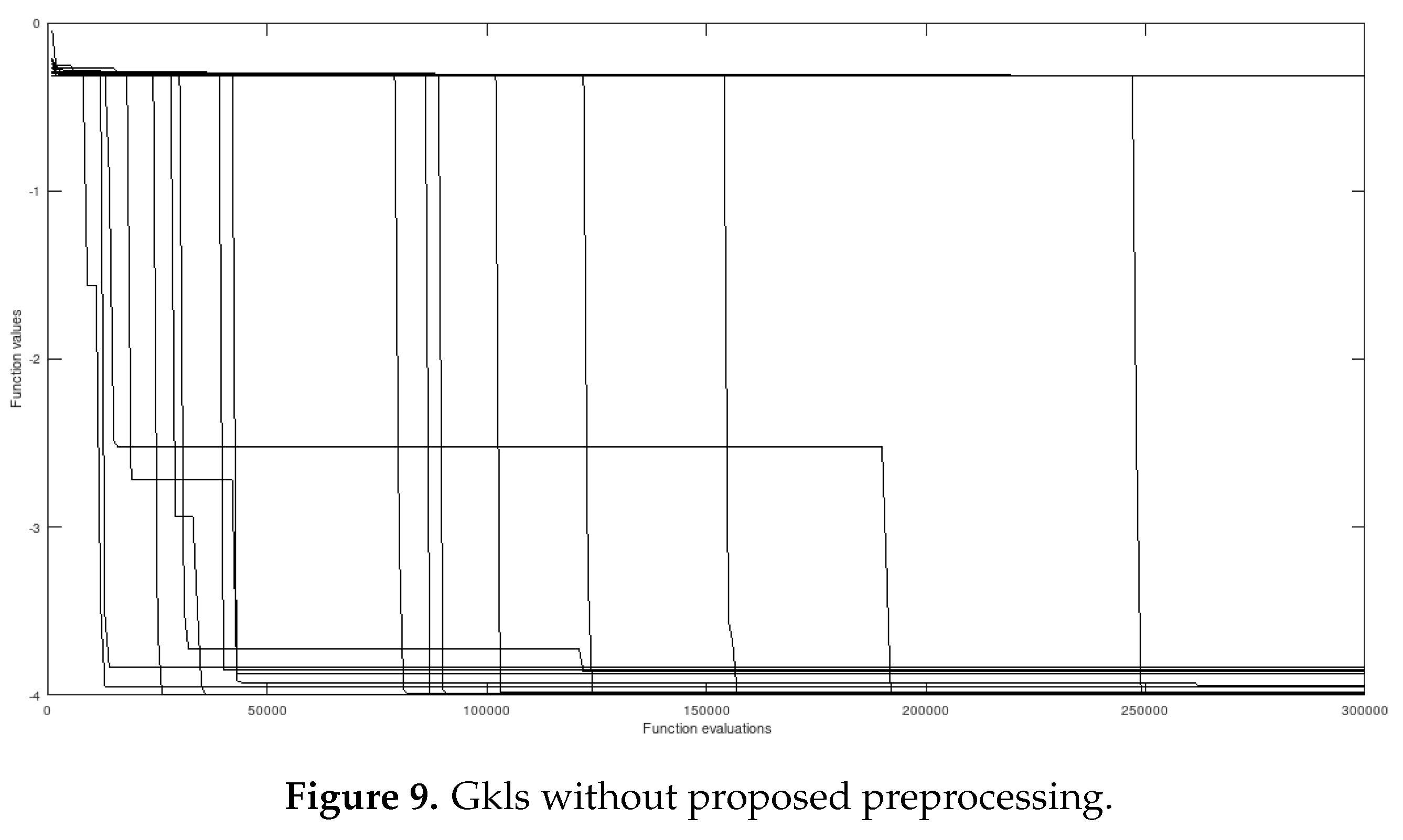

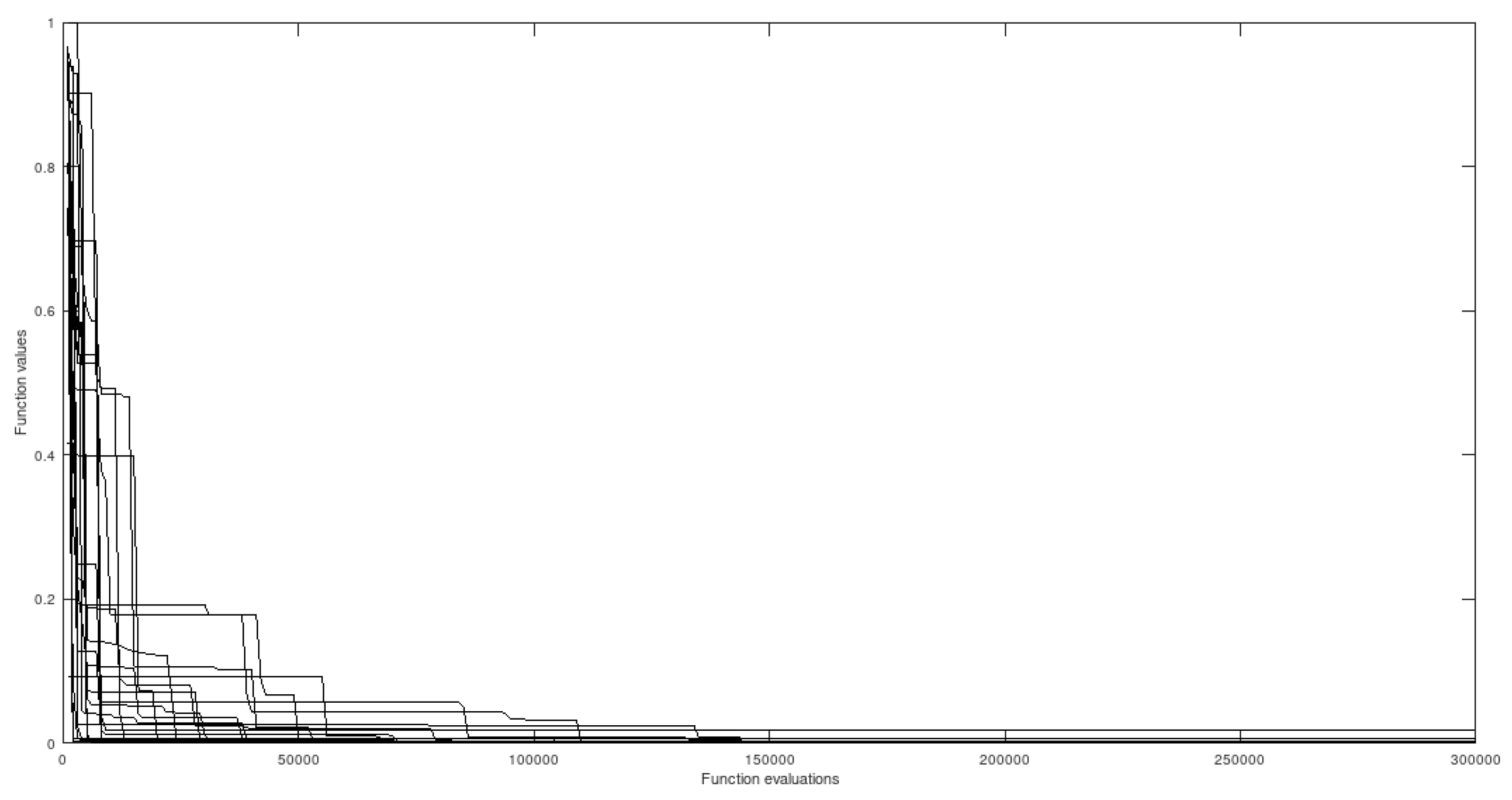

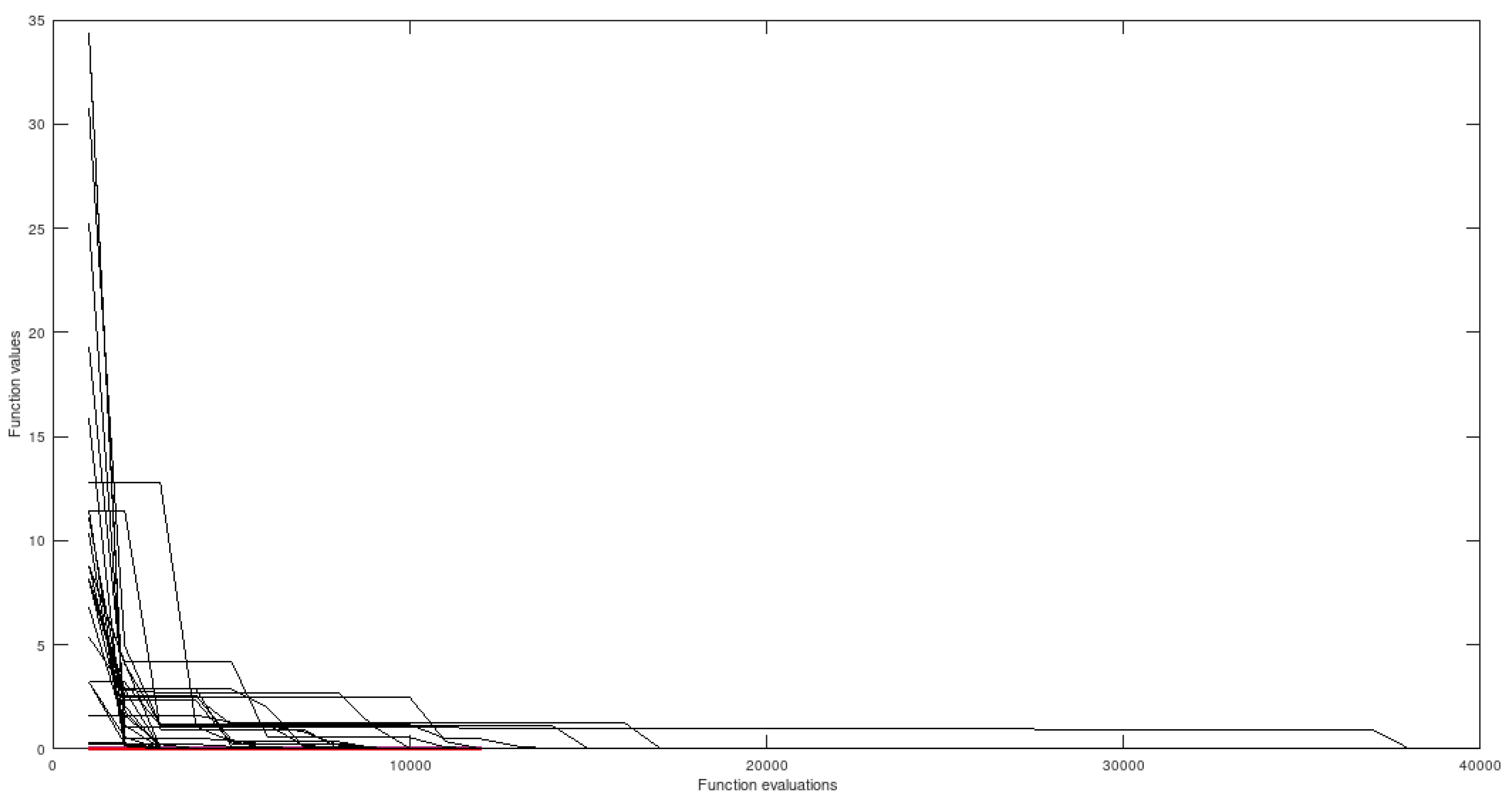

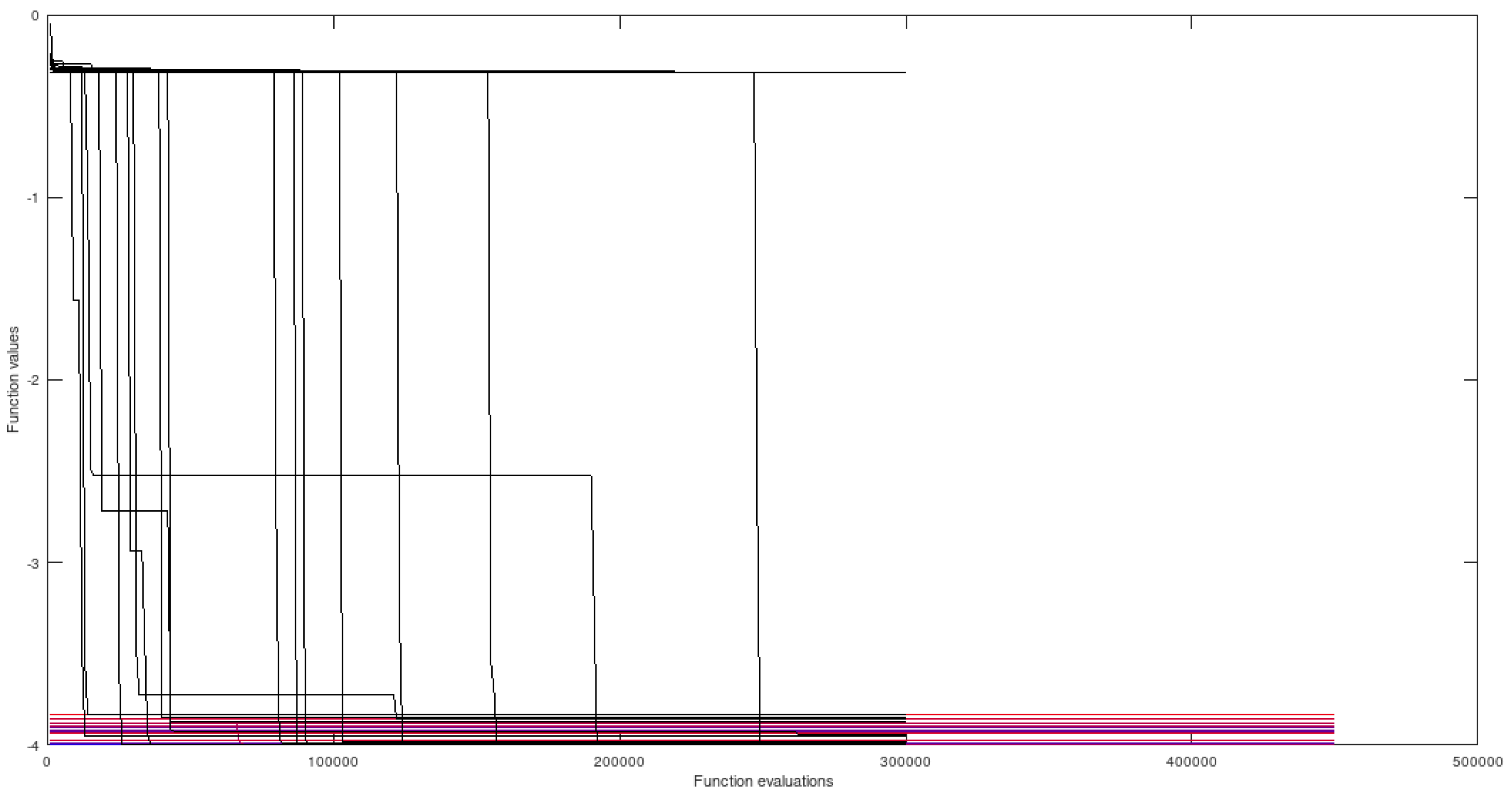

By observing the figures it is possible to note that, when using the preprocessing apparatus, convergence to all global minima is obtained in all cases and the average number of function evaluations is reduced, relatively to simulations not using the proposed method. On the other hand, without the extra preprocessing step, many optimization sessions fail to find certain extremely difficult minimizers.

Table 1.

Functions effectively used in the tests.

Table 1.

Functions effectively used in the tests.

|

Function |

Domain dimension |

Global minimum |

Number of global minimizers |

|

HIMMELBLAU |

2 |

0 |

4 |

|

GKLS 55 ND |

2 |

-4.00 |

1 |

|

ROSENBROCK |

2 |

0 |

1 |

5.2. Some Illustrative Graphs

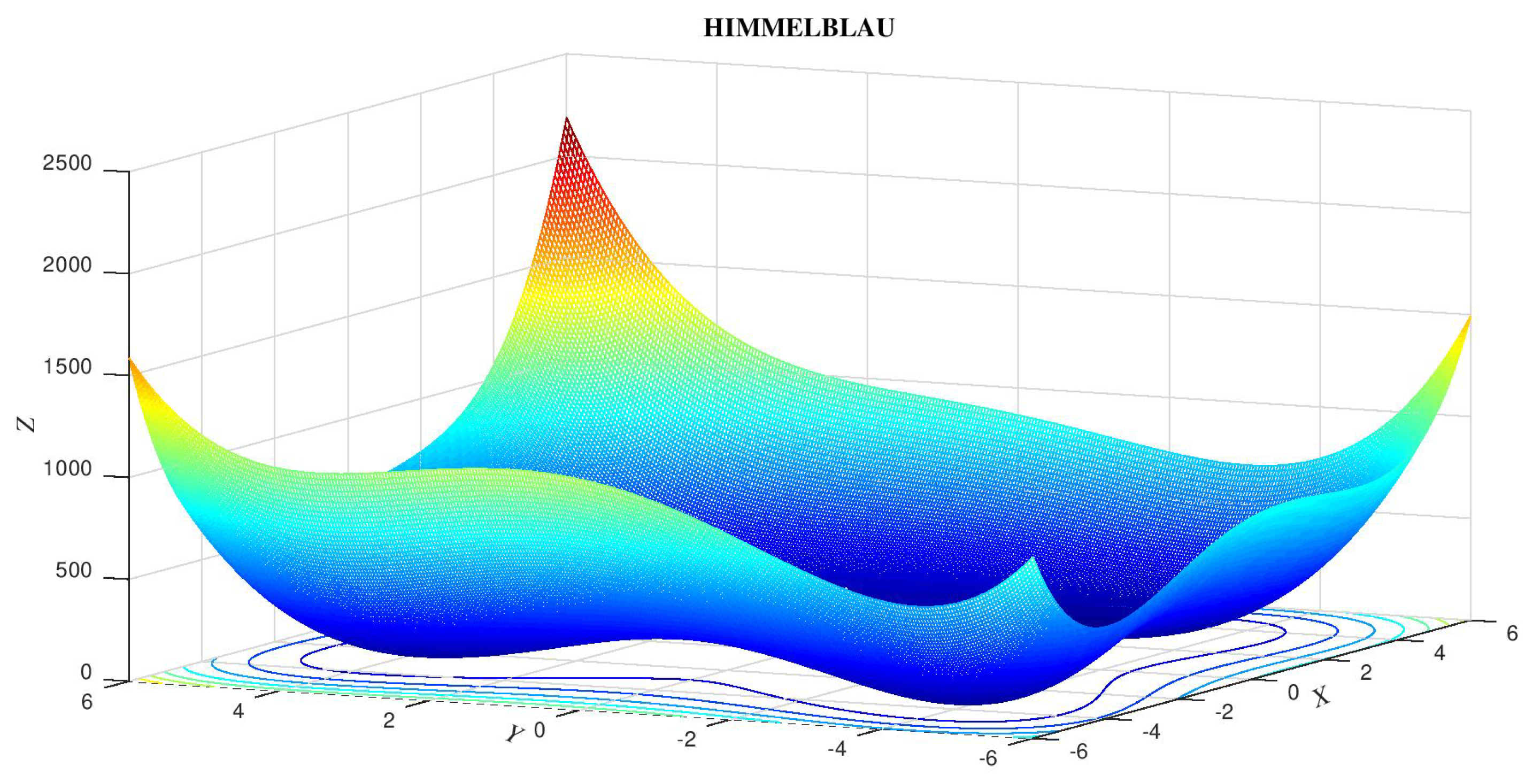

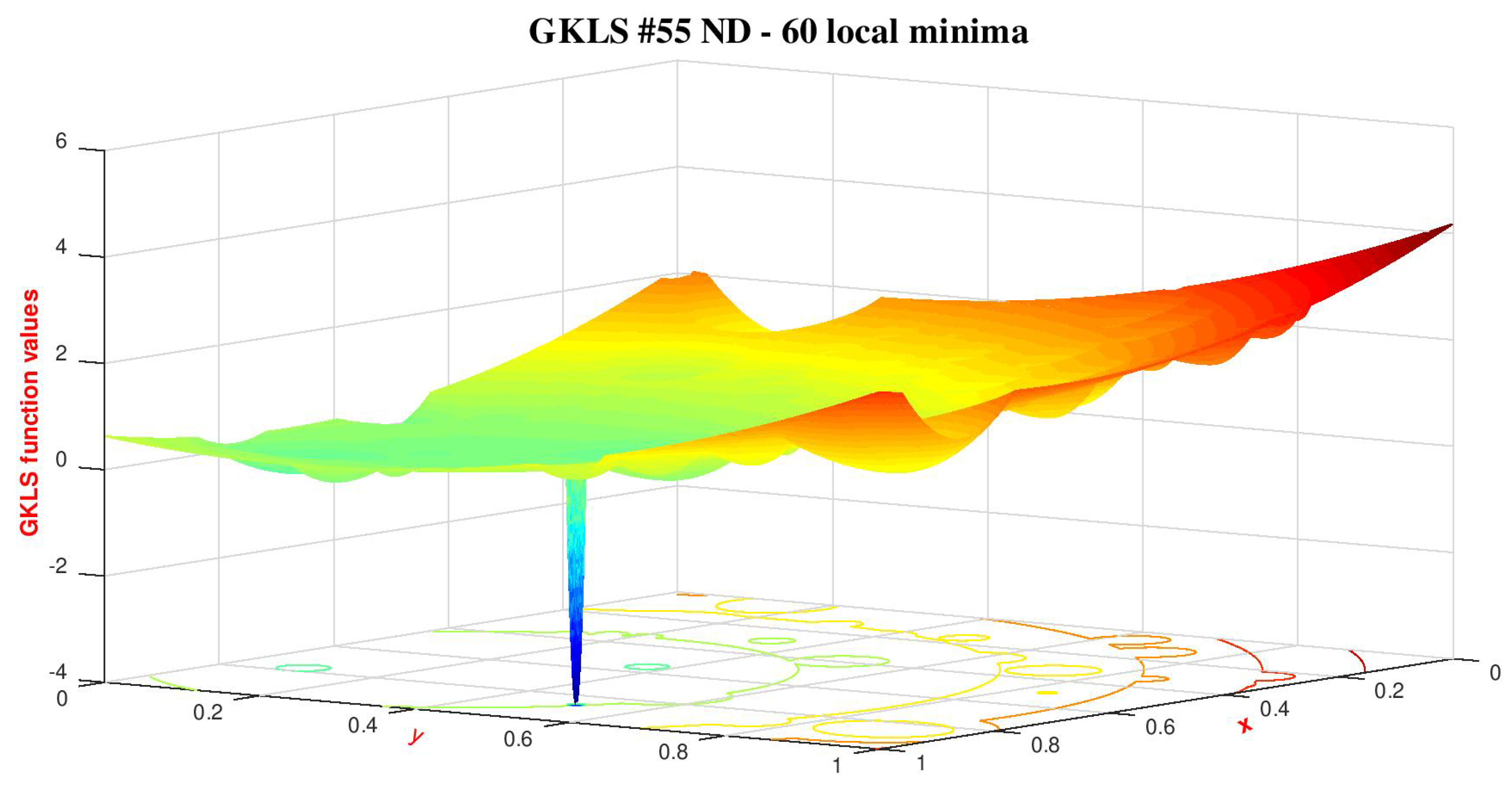

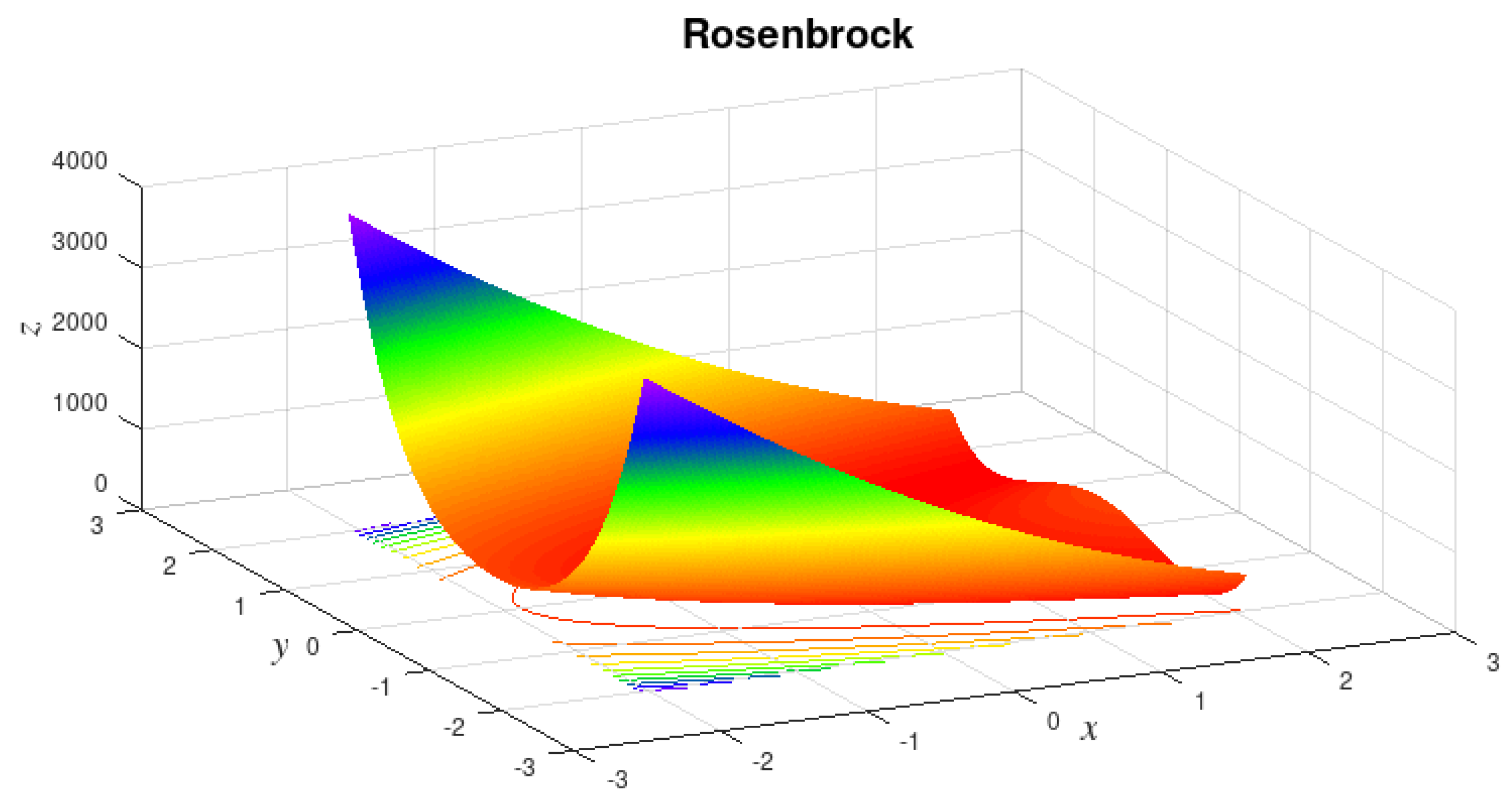

In this subsection the figures illustrate the difficulty presented by some functions to any device intending to automatically find all their global minimizers - although most domains are bidimensional, they speak by themselves.

5.2.1. Himmelblau - 2-Dimensional Domain

This function features 4 global minima and was chosen to highlight the adequacy of the proposed algorithm to quickly locate (tiny) neighborhoods of all minimizers just after the preprocessing stage, saving a great deal of computational effort in the phase of fine tuning - this effect is clearly shown ahead, using the respective performance graphs. The four minimizers are (3, 2), (-2.805118, 3.131312), (-3.779310, -3.283186) and (3.584428, -1.848126).

5.2.2. GKLS 55 ND - 2-Dimensional Domain (Scaled to )

This function was obtained by means of the GKLS generator [

12], that is a software tool for generating test functions of three types of classes, in terms of differentiability, and known local and global minima for multiextremal and multidimensional global optimization, restricted to hyperrectangles. This tool is very helpful whenever it is desired to test certain features of global optimization methods, being very easy to use when constructing hard test functions. The “55” is a numerical identification whithin the tool and “ND" means non-differentiable.

In this particular implementation, the generated function has 60 local minima and one global minimum with a small, sharp and isolated attraction basin, surrounded by tens of local minima, what makes it difficult to reach the interior of the favorable region. Although the domain would usually be , it was linearly scaled to .

5.2.3. ROSENBROCK - 2-Dimensional Domain

This particular instance of the Rosenbrock function has one global minimum at (1,1) with value zero. The used domain was .

It is particularly hard, for some optimization methods, in the final phase (fine tuning the value of the global minimizer). Gradient-based optimization algorithms may be severelly delayed or even get stuck in such conditions.

Figure 4.

ROSENBROCK function.

Figure 4.

ROSENBROCK function.

5.3. Results Using HQF ASA Coupled to the Proposed Method

Main assumptions made are:

5.3.1. HIMMELBLAU - 2-Dimensional Domain

The best minimizers found in the simulations are (3.584428, -1.848127), (3,2), (-2.805119, 3.1313) and (-3.779310253, -3.283185991) - all 4 distinct global minimizers were found along several simulations within established error margin .

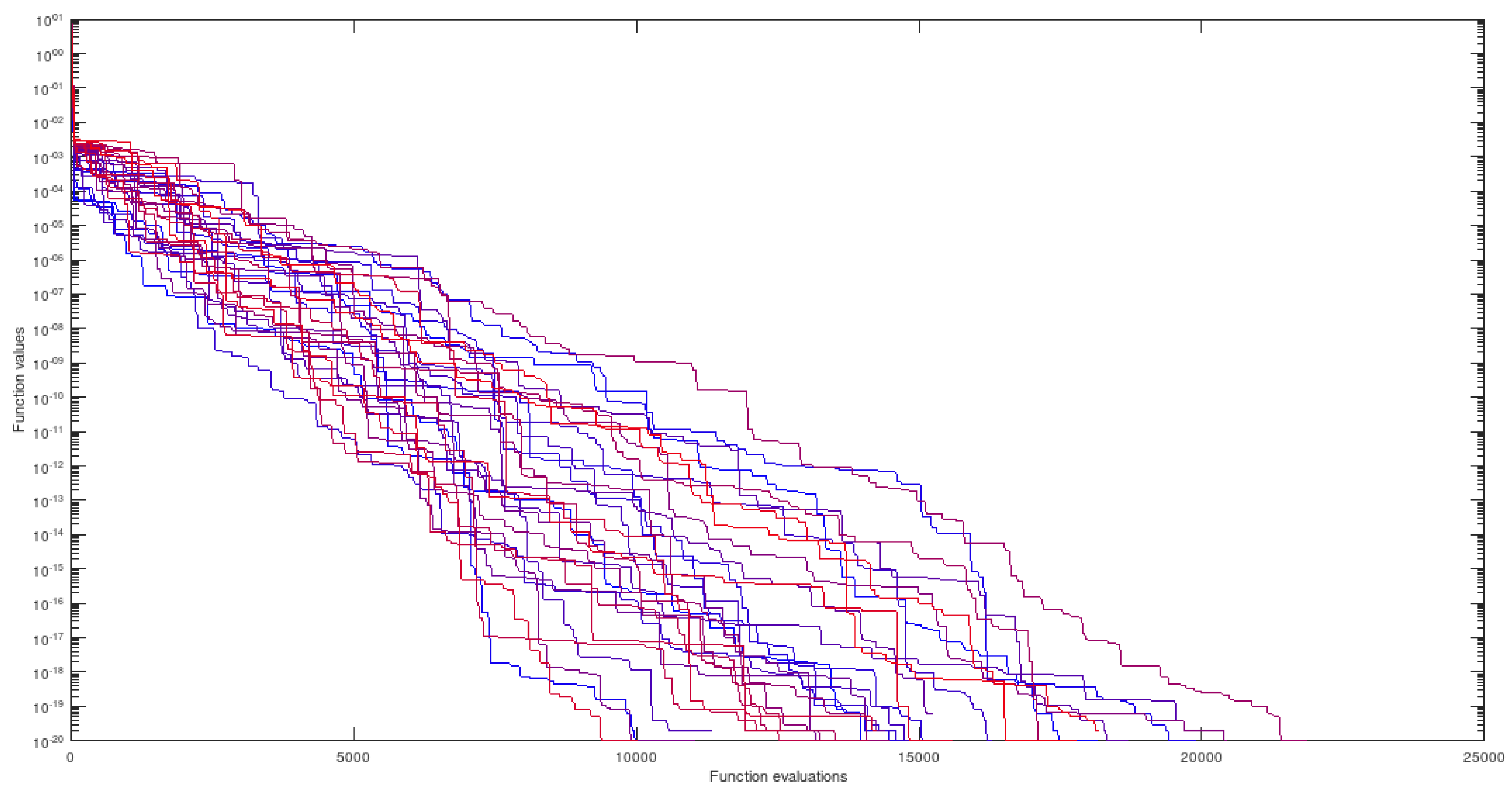

Figure 5.

HIMMELBLAU - departing from all 4 attraction regions.

Figure 5.

HIMMELBLAU - departing from all 4 attraction regions.

5.3.2. GKLS 55 ND - 2-Dimensional Domain

The best global minimizer found is (0.736159002, 0.021699811).

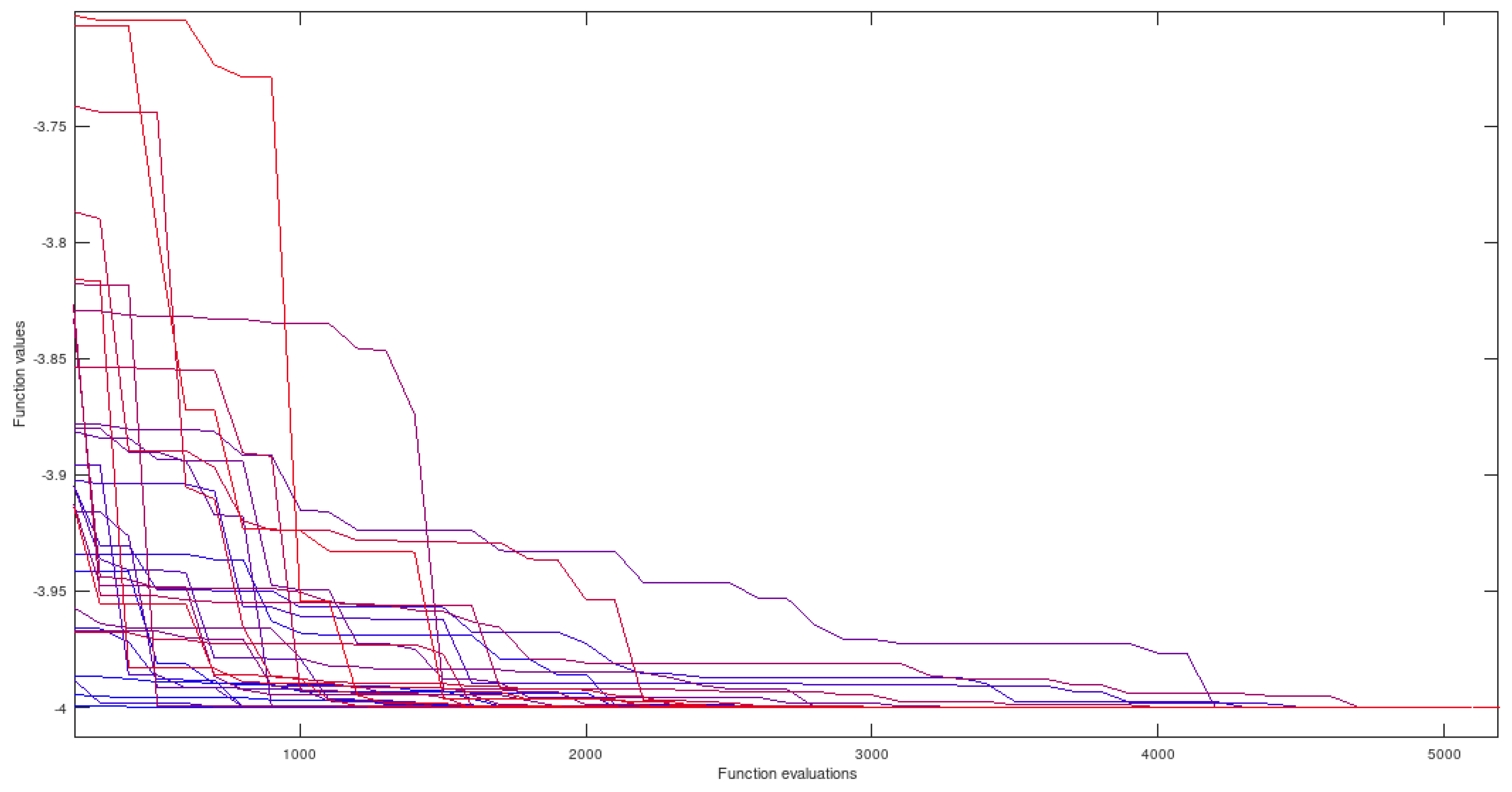

Figure 6.

GKLS with proposed preprocessing.

Figure 6.

GKLS with proposed preprocessing.

5.3.3. ROSENBROCK - 2-Dimensional Domain

The best global minimizer found is (1,1). All simulations arrived at the global minimum within the established discrepancy.

Figure 7.

ROSENBROCK with preprocessing.

Figure 7.

ROSENBROCK with preprocessing.

5.4. Graphs of Simulations Using HQF ASA, Without the Proposed Preprocessing

In this scenario, no simulation was able to converge within the preestablished error margin - all of them stagnated at suboptimal locations. Below, some figures will illustrate the relative difference when using and not using the proposed strategy.

5.4.1. HIMMELBLAU - 2-Dimensional Domain

Figure 8.

Himmelblau without preprocessing.

Figure 8.

Himmelblau without preprocessing.

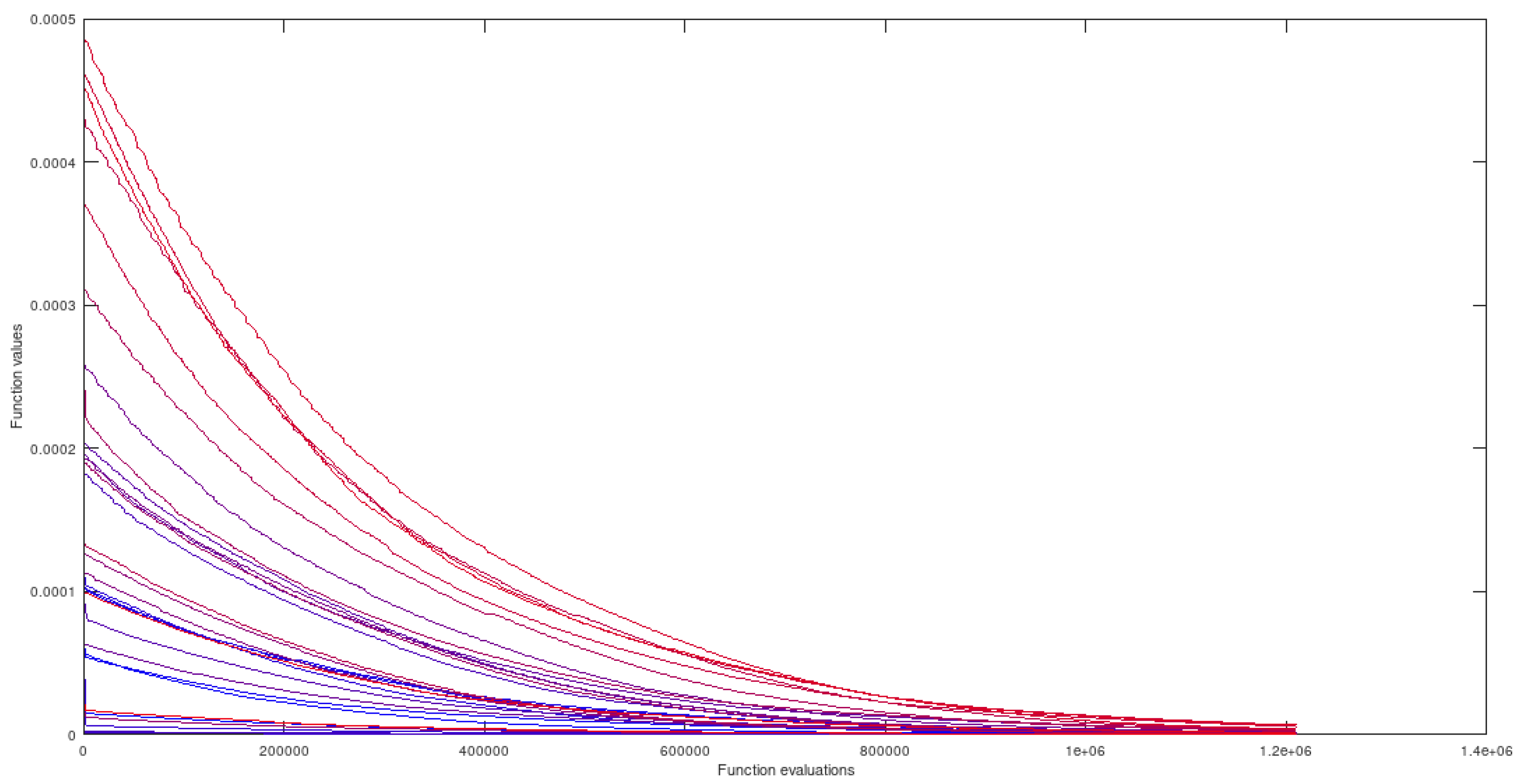

5.4.2. GKLS 55 ND - 2-Dimensional Domain

Figure 9.

Gkls without proposed preprocessing.

Figure 9.

Gkls without proposed preprocessing.

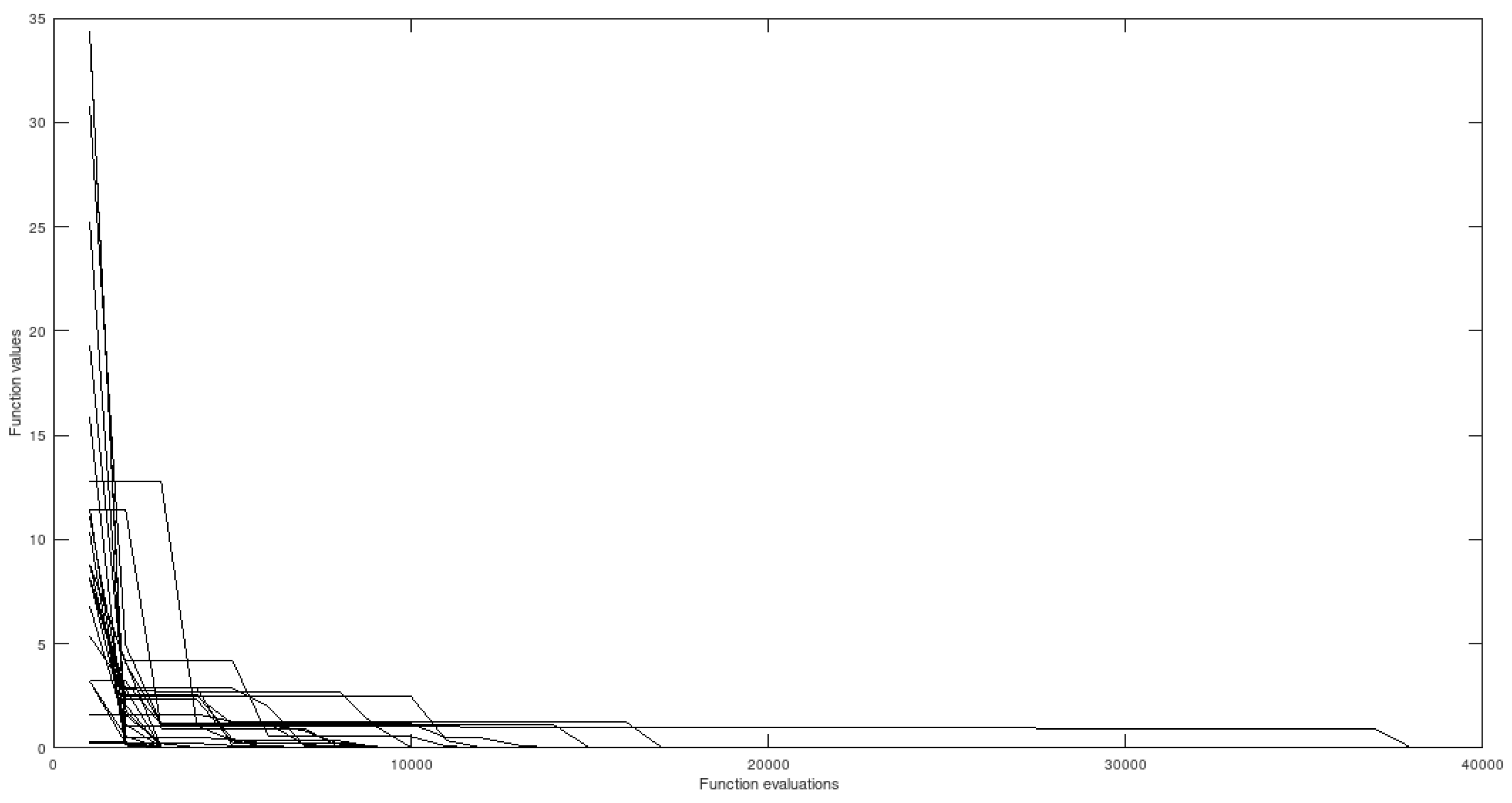

5.4.3. ROSENBROCK - 2-Dimensional Domain

Figure 10.

Rosenbrock without preprocessing

Figure 10.

Rosenbrock without preprocessing

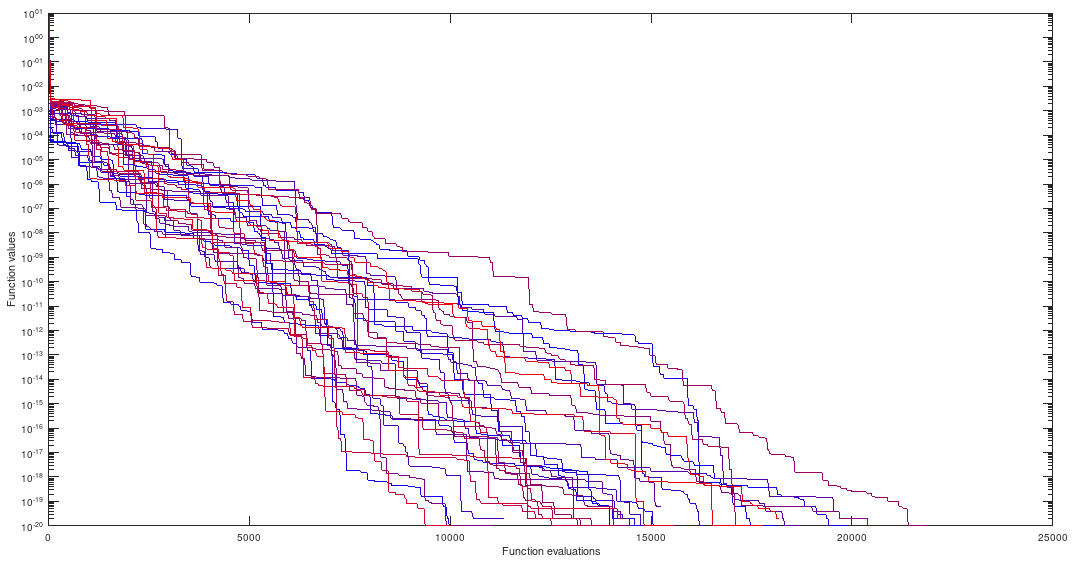

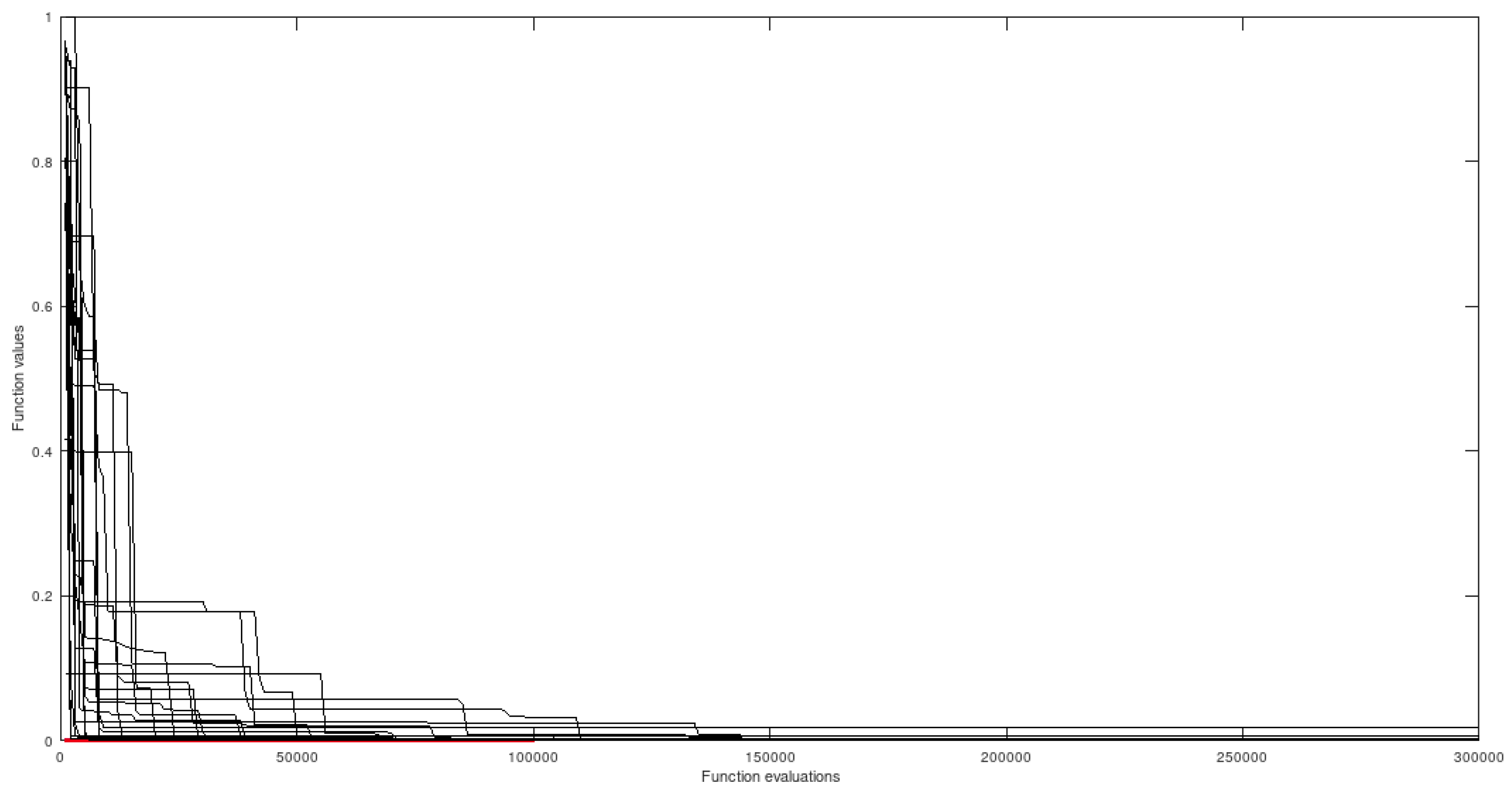

5.5. Superimposed Graphs with and Without the Proposed Preprocessing

Here, the graphs in the two conditions are plotted in the same figure, for the sake of comparison between using the proposed method or not. The black graphs correspond to simulations done without the suggested preprocessing.

5.5.1. HIMMELBLAU - 2-Dimensional Domain

Figure 11.

Himmelblau with and without preprocessing.

Figure 11.

Himmelblau with and without preprocessing.

5.5.2. GKLS 55 ND - 2-Dimensional Domain

Figure 12.

Gkls with and without proposed preprocessing.

Figure 12.

Gkls with and without proposed preprocessing.

5.5.3. ROSENBROCK - 2-Dimensional Domain

Figure 13.

Rosenbrock with and Without Preprocessing.

Figure 13.

Rosenbrock with and Without Preprocessing.

6. Conclusions

The problem of finding good initial points for multimodal global optimization of numerical functions in Euclidean spaces has been investigated, and an approach for its solution proposed. The method uses Schoenberg-Steinhaus space-filling curves to obtain points located in attraction basins of global minimizers and delivers these candidates to the chosen GO method, for further processing. The presented results evidence that it is possible to obtain very good results by using deterministic initialization with space-filling curves (instead of purely uniform randomization), and executing decoupled threads based on the HQF ASA paradigm, for instance, starting from seeds obtained in the preliminary stage. Another noticeable aspect is that the scheme may be implemented in a fully parallel way, using totally heterogeneous computational resources and without coordination or synchronization efforts between optimization threads. Besides, the procedure was shown to offer sometimes even better results, without the benefit of collective and simultaneous cooperation between individuals, typical of swarm-based methods. In all cases the proposed preprocessing showed large improvements, using exactly the same underlying optimization paradigm, being able to reach all global optima in an efficient manner. In particular, the landscape of GKLS 55 ND offers a highly severe landscape, which the algorithm was able to overcome in all simulations, when coupled to HQF ASA. An extremely important fact is that the paths of space-filling curves include all elements of a given region, including those with irrational coordinates (unable to be exactly represented in present day digital computers) - this characteristic is very singular.

Ethical approval This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding

This study was not funded by any external agent.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- A. Boyarsky, P. Góra, Laws of Chaos, Invariant Measures and Dynamical Systems in One Dimension. Birkhäuser, Boston, 1997.

- Y. Cherruault, A new reducing transformation for global optimization (with Alienor method). Kybernetes 34 (7/8) (2005) 1084–1089. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cherruault, G. Mora, Optimisation Globale - Theorie des courbes α-denses, Economica, Paris, 2005.

- G.H. Choe, Computational Ergodic Theory. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2005.

- K. Dajani, C. Kraaikamp, Ergodic Theory of Numbers, The Mathematical Association of America, Washington DC, 2002.

- M. Epitropakis, V. Plagianakos, M. Vrahatis, Finding multiple global optima exploiting differential evolution’s niching capability, in IEEE Symposium on Differential Evolution, 2011. SDE 2011. (IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence), Paris, France, April 2011, p. 80-87.

- M. Gaviano, D.E. Kvasov, D. Lera, Y. D. Sergeyev, Software for generation of classes of test functions with known local and global minima for global optimization. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 29 (4) (2003) 469–480.

- B. Goertzel, Global Optimization with Space-Filling Curves. Applied Mathematics Letters 12 (1999) 133–135. [CrossRef]

- Ingber, L.: Adaptive simulated annealing (ASA): Lessons learned. Control and Cybernetics 25 (1) (1996) 33–54.

- S. Kirkpatrick, C. D. Gelatt, Jr., M. P. Vecchi, Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220 (1983) 671–680.

- P.J.M. van Laarhoven, E.H.L. Aarts, Simulated Annealing: Theory and Applications. D. Reidel, Dordrecht, 1987.

- D. Lera, Y. D. Sergeyev, Lipschitz and Hölder global optimization using space-filling curves. Applied Numerical Mathematics 60 (2010) 115–129. [CrossRef]

- N. Metropolis, A. Rosenbluth, M. Rosenbluth, A. Teller, E. Teller, Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. Journal of Chemical Physics 21 (6) (1953) 1087–1092. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Oliveira Jr., L. Ingber, A. Petraglia, M.R. Petraglia, M.A.S. Machado, Stochastic Global Optimization and Its Applications with Fuzzy Adaptive Simulated Annealing, Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg, 2012.

- H. A. Oliveira Jr., Evolutionary Global Optimization, Manifolds and Applications, Springer-Verlag, Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London, 2016.

- H.A. Oliveira Jr., A. Petraglia, Global optimization using space-filling curves and measure-preserving transformations, in: A. Gaspar-Cunha et al. (Eds.), Soft Computing in Industrial Applications, AISC 96, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 2011, pp. 121-130.

- H. A. Oliveira Jr., A. Petraglia, Establishing Nash equilibria of strategic games: a multistart Fuzzy Adaptive Simulated Annealing approach, Applied Soft Computing, 19 (2014) 188–197. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Oliveira Jr.,Homotopic quantum fuzzy adaptive simulated annealing [HQF ASA], Information Sciences. 669 (2024) 120529.

- M. Preuss, Multimodal Optimization by Means of Evolutionary Algorithms, Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Sagan, Space-Filling Curves, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1994.

- Y. D. Sergeyev, R.G. Strongin, D. Lera, Introduction to Global Optimization Exploiting Space-Filling Curves, Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London, 2013.

- R. Thomsen, Multimodal optimization using crowding-based differential evolution, in Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation. Portland, Oregon, IEEE Press, 20-23 Jun. 2004, pp. 1382-1389.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).