Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

31 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

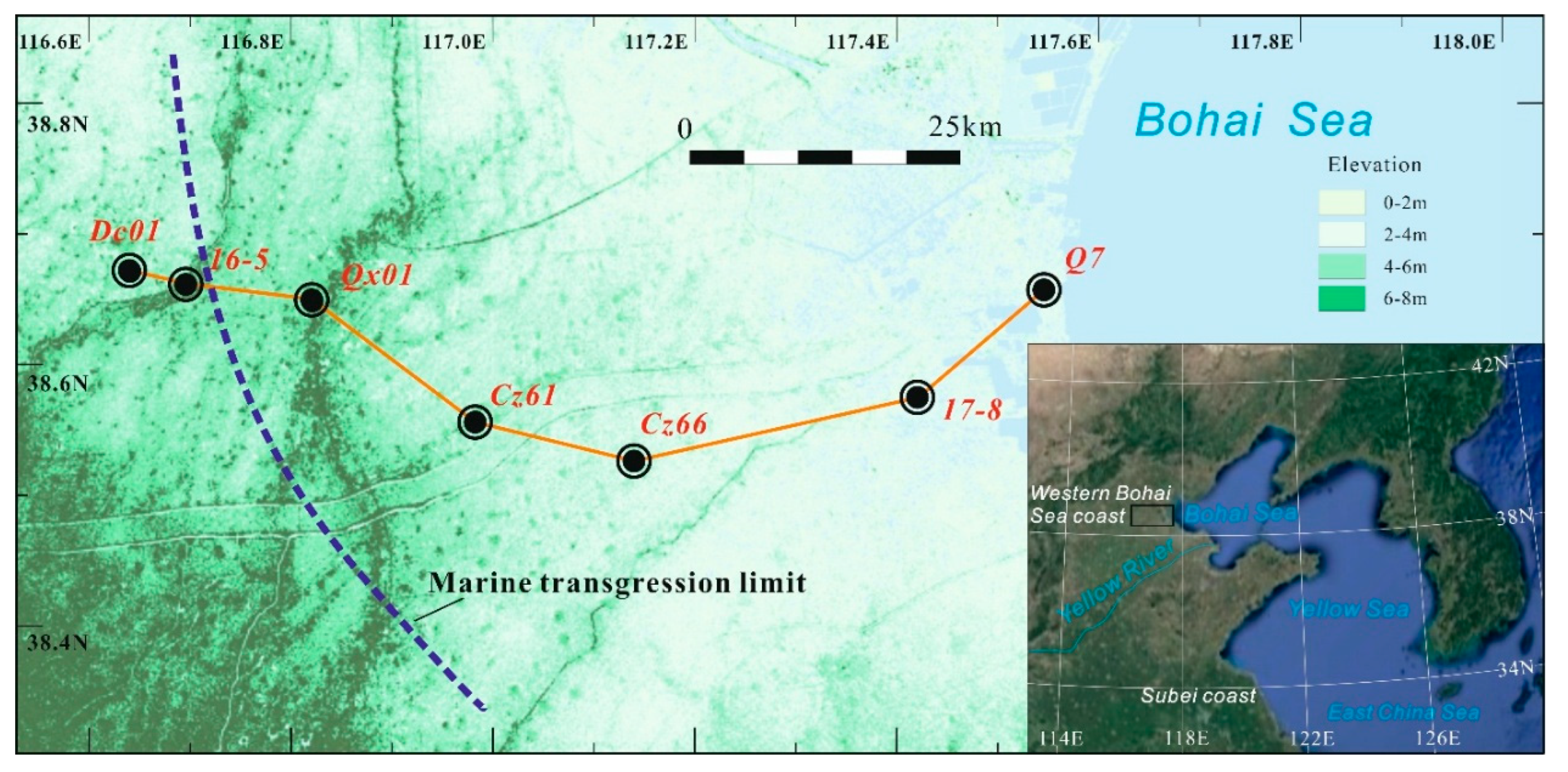

2.1. Study Sites and Sediment Core Collection

2.2. Sedimentary Identification and Subsampling

2.3. Measurement of Mud-Water EC and pH

2.4. Foraminifera Analysis

3. Results

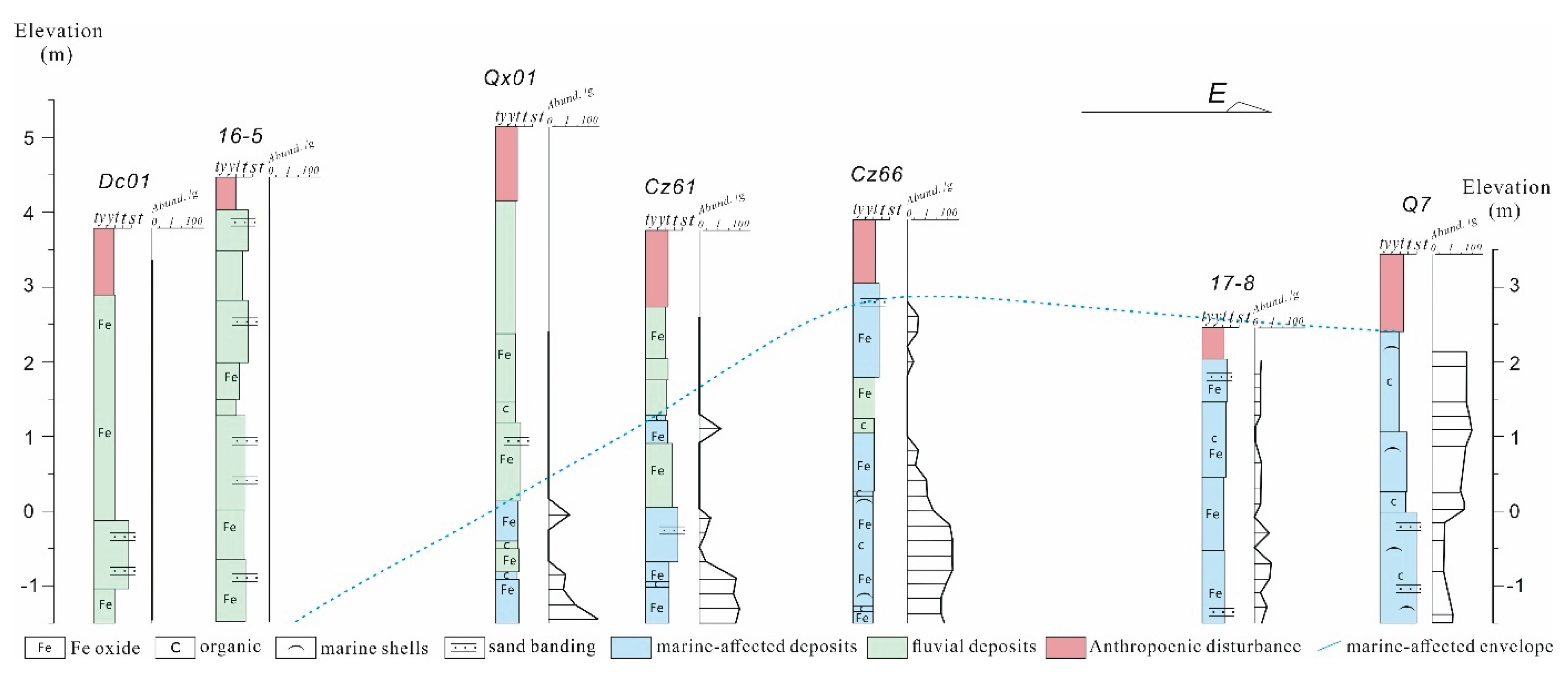

3.1. Sediment Lithological Characteristics and Marine Influences

3.1.1. Anthropogenic Disturbance

3.1.2. Fluvial Sediments

3.1.3. Marine-Related Sediments

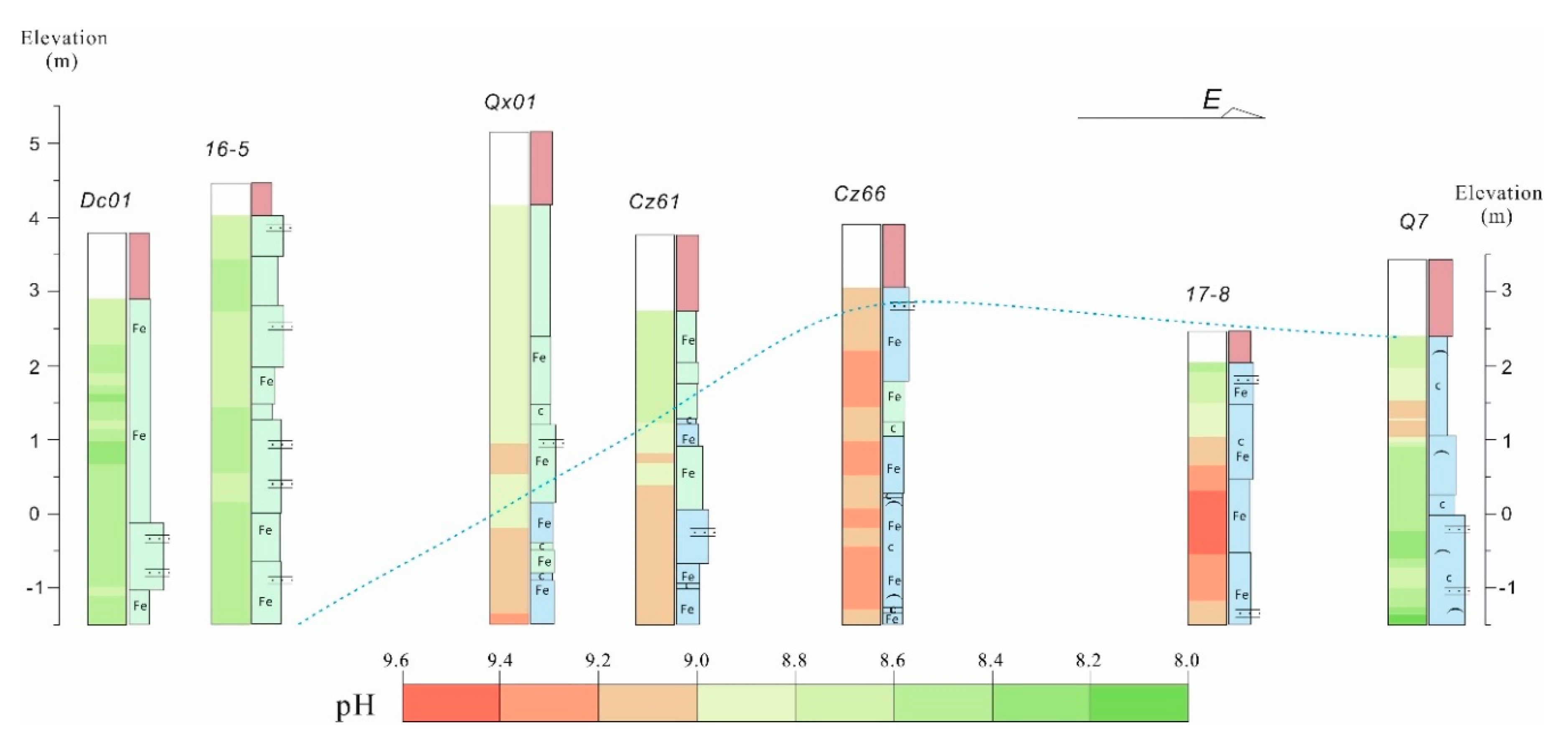

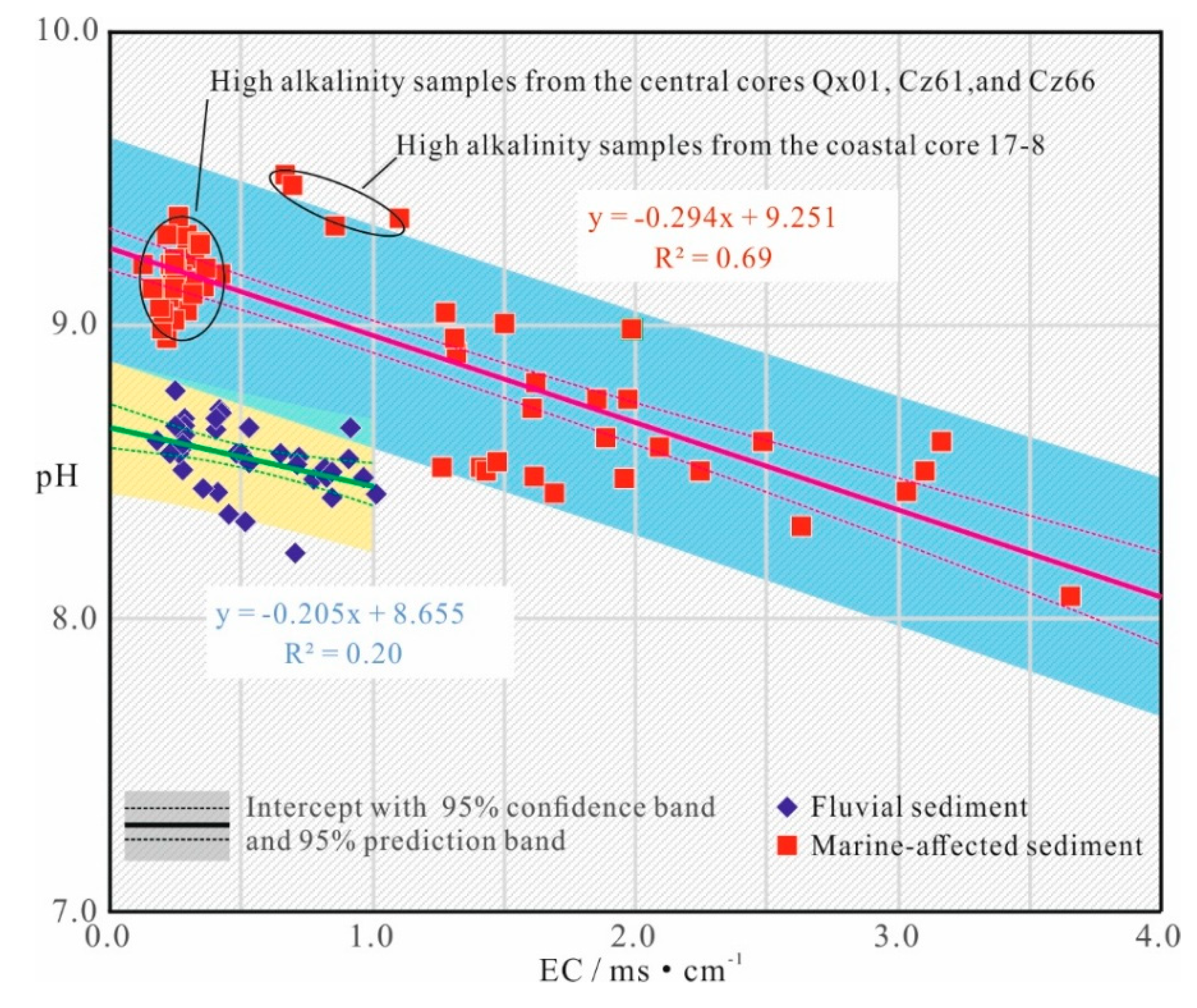

3.2. Sediment EC and pH Characteristics

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2.2. Spatial Variability

4. Discussion

4.1. Natural Desalination of Marine-Affected Sediments

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Jennerjahn, T. C. Biogeochemical Response of Tropical Coastal Systems to Present and Past Environmental Change. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2012, 114, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C. Historical Changes in the Yellow River Delta, China. Mar. Geol. 1993, 113, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; et al. The Record of Mid-Holocene Maximum Landward Marine Transgression in the West Coast of Bohai Bay, China. Mar. Geol. 2015, 359, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hsieh, Y.P.; Harwell, M.A.; Huang, W. Modeling Soil Salinity Distribution along Topographic Gradients in Tidal Salt Marshes in Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Regions. Ecol. Model. 2007, 201, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, P. (1990). Saltmarsh ecology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xian, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Yao, R.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Xie, W.; Cao, D. Saline–Alkaline Characteristics during Desalination Process and Nitrogen Input Regulation in Reclaimed Tidal Flat Soils. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L. , Kang, Y. , & Wan, S. (2014). Influence of microsprinkler irrigation amount on water, soil, and pH profiles in a coastal saline soil. The Scientific World Journal. 2014(1), 279895. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X., Gu, H. J., Jia, M. Q., Liu, C. B., Liu, M. Q., Gao, Z. W., & Zhang, G. G. (2020). Changes in Sediment Properties and the Bacterial Community in Marine Sediments after Entering the Terrestrial Ecosystem in Bohai Bay, Northern China. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chen, B.; Shen, Q. Studies on the Changes of pH Value and Alkalization of Heavily Saline Soil in Sea Beach during Its Desalting Process. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2000, 37, 521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; et al. Sea Level Change in Bohai Bay. North China Geol. 2024, 47, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Wang, D.; Pei, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Shang, Z.; Wang, H. Topographic and Geomorphic Evolution Process in Tianjin Binhai New Area after Middle Holocene. North China Geol. 2011, 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Sun, M., Wang, X., Lan, H. (2019). Statistical Analysis of the Characteristics Difference of Rainfall over Bohai Bay and the Land. Climate Change Research Letters.

- An, P.; Li, W.; Li, X.J.; et al. Soil Vegetation Inventory of an Undisturbed Bohai Bay Ecosystem of China. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 6748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T. Mensuration of Electric Conductivity. In Japan Association for Quaternary Research; University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1993; Volume 2, pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wu, T.; Wang, W.; Guan, J.; Zhai, P. Integrating Non-Planar Metamaterials with Magnetic Absorbing Materials to Yield Ultra-Broadband Microwave Hybrid Absorbers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 022903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillel, D. Environmental Soil Physics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; et al. Holocene Sea-Level Change on the Central Coast of Bohai Bay, China. Earth Surf. Dynam. 2020, 8, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, C.; Xin, P.; Kong, J.; Li, L. Salt Dynamics in Coastal Marshes: Formation of Hypersaline Zones. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 3259–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Pei, Y.; Tian, L.; Wang, F.; Xiao, G.; Hu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yuan, H. The Influence of Land Reclamation in Tianjin Binhai New Area on the Environment of Shallow Groundwater in Coastal Lowland. Geol. Bull. China 2016, 35, 1653–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.; Pei, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Tian, L.; et al. Environmental Geological Survey and Assessment Report of the Reclaimed Land Area in Binhai New Area, Tianjin; Geological Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jourabchi, P.; Van Cappellen, P.; Regnier, P. Quantitative Interpretation of pH Distributions in Aquatic Sediments: A Reaction-Transport Modeling Approach. Am. J. Sci. 2005, 305, 919–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H. The States of pH, Eh in Surface Sediments of the Yangtze River Estuary and Its Adjacent Areas and Their Controlling Factors. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2008, 26, 820–827. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Ding, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, F. Distribution Patterns and Influencing Factors of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Sediments from Representative Wetlands in Hebei Province. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2025, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumm, W.; Morgan, J.J. Aquatic Chemistry: Chemical Equilibria and Rates in Natural Waters, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Core | Sampling site | Position | Elevation / m |

| Dc01 | Agricultural land | E 116.6586°, N 38.6698° | 3.74 |

| 16-5 | Agricultural land | E 116.7150°, N 38.6611° | 4.48 |

| Qx01 | Agricultural land | E 116.8219°, N 38.6485° | 5.16 |

| Cz61 | Factory land | E 116.9866°, N 38.5587° | 3.76 |

| Cz66 | Factory land | E 117.1396°, N 38.5256° | 3.87 |

| 17-8 | Agricultural land close to wetland | E 117.4139°, N 38.5750° | 2.46 |

| Q7 | Riverbank | E 117.5306°, N 38.6574° | 3.46 |

| WBSC | Dc01 | 16-5 | Qx01 | Cz61 | Cz66 | 17-8 | Q7 | |

| Min. | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.67 | 1.27 |

| Max. | 3.66 | 1.02 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 1.99 | 3.66 |

| Mean | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 1.20 | 2.07 |

| Standard Error | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.69 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.78 |

| Variance coefficient (CV) (%) | 99.58 | 30.00 | 19.66 | 32.53 | 32.10 | 20.53 | 41.88 | 37.94 |

| WBSC | Dc01 | 16-5 | Qx01 | Cz61 | Cz66 | 17-8 | Q7 | |

| Min. | 8.07 | 8.22 | 8.43 | 8.71 | 8.67 | 8.97 | 8.53 | 8.07 |

| Max. | 9.51 | 8.71 | 8.77 | 9.40 | 9.20 | 9.37 | 9.51 | 9.04 |

| Mean | 8.84 | 8.52 | 8.59 | 8.98 | 8.94 | 9.18 | 9.13 | 8.60 |

| Standard Error | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 0.26 |

| Variance coefficient (CV) (%) | 3.43 | 1.44 | 1.08 | 1.78 | 2.07 | 1.07 | 4.27 | 3.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).