1. Introduction

Hemorrhagic shock is the most common cause of death in mass casualty incidents such as earthquakes, tsunamis, fires, traffic accidents, and wars. An analysis of 4,596 battlefield deaths by the U.S. military showed that 87.3% of deaths occurred during pre-hospital treatment, of which 24.3% were considered potentially preventable. Among these potentially preventable deaths, 90.9% of the injuries were related to shock caused by severe blood loss without timely treatment [

1]. In the 8.0-magnitude earthquake that struck Wenchuan, China, in 2008, 69,227 people were killed and 374,643 were injured. Among the injured, crush injuries accounted for 68%, with the three most common injury sites being the extremities (46.9%), head (14.7%), and chest (9.0%). Such injuries are highly likely to lead to hemorrhagic shock [

2].

In the face of the demand for emergency treatment of sudden and mass casualties in mass casualty incidents, there is often a prominent contradiction between the limitations of medical resources, detection capabilities, and data at disaster sites and the requirement for accuracy in mass triage[

3]. With the rapid advancement of robotic technology, the deployment of robots offers greater flexibility and reliability for disaster emergency response and search - rescue operations, which can effectively address the shortage of search - rescue forces at disaster sites[

4,

5].

As early as the 2005 Hurricane Katrina disaster in the United States, unmanned aerial vehicles and ground robots were deployed to search for victims in the ruins [

6]. In 2011, underwater robots, drones, and ground robots were all involved in search and rescue, exploration, and inspection tasks during the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand and the tsunami and nuclear leakage accidents caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake in the same year[

7]. In 2013, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched the Robotics Challenge worldwide, with the theme of search and rescue robots[

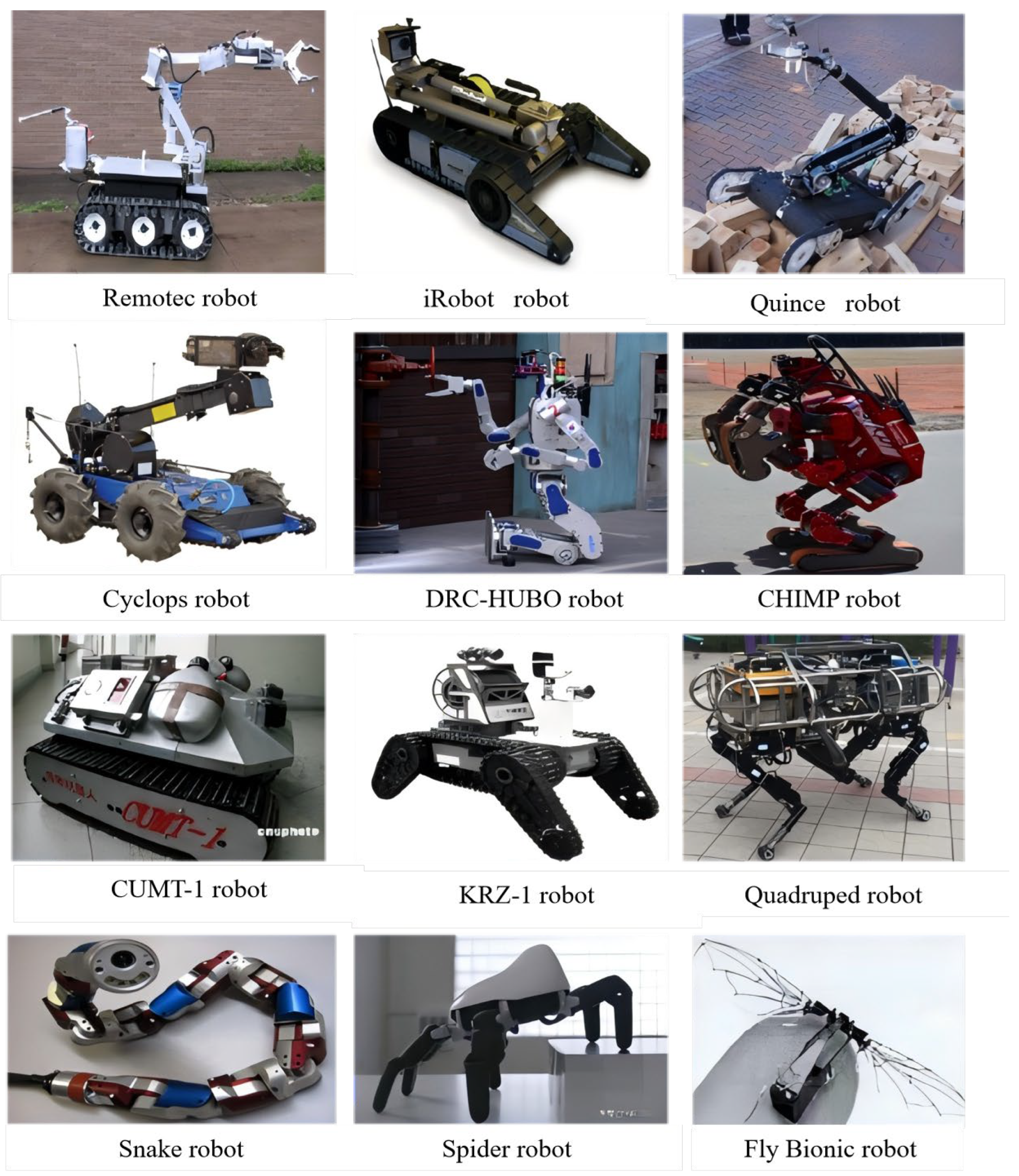

8]. In a semi-autonomous mode, robots overcome various simulated disaster scenes to carry out disaster relief, including high-difficulty tasks such as traversing complex terrain, opening and closing valves, and breaking doors to enter rooms. As shown in

Figure 1, several typical search and rescue robots were developed, which can be mainly divided into tracked [

9,

10,

11,

12], wheeled [

13,

14], legged [

15,

16,

17,

18], and bionic [

19,

20,

21] types. Tracked and wheeled robots have relatively fast movement speeds, can carry manipulators and heavy materials, and are more suitable for large-scale search and rescue in mines and intact buildings. Legged robots have excellent obstacle-surmounting capabilities and can perform search and rescue in relatively rugged environments. Bionic robots are highly flexible and have strong terrain adaptability, but they cannot carry large loads, making them more suitable for searching for people.

Snake-like robots are widely used in field operation fields due to their small size and flexible movement[

22]. Yang applied snake-like robots to the inspection of high-voltage transmission lines, improving the real-time adaptability of snake-like robots in high-altitude movement[

23]. Li proposed a compact self-assembling snake-like robot with joint drive and onboard visual perception, which enhances the perception ability, driving performance and docking capability of modular robots[

24]. To meet the inspection needs of industrial and civil infrastructure, Leggieri[

25] designed a mobile tracked snake-like robot, Canali[

26] designed a long-arm cable-driven hyper-redundant snake-like robot, and Qin[

27] completed the design method and dynamic modeling of a cable-driven snake-like manipulator maintainer. Aiming at the problem of large noise in data collection during search and rescue by snake-like robots, Bao[

28] studied the head stability control strategy of wheel-less snake-like robots based on inertial sensors, and Kim[

29] adopted adaptive robust control schemes to enhance the stability of head images of snake-like robots. Chitikena[

30] studied the ethical issues of snake-like robots in disaster search and rescue, and put forward the ethical and technical factors that must be considered in the research and development of snake-like robots.

In the event of mass casualty incidents, it is difficult for large-scale medical equipment and medical personnel to enter within a short period of time. Especially for injuries with high fatality rates such as hemorrhagic shock, a large number of medical staff are needed in a short time to conduct rapid triage of the injured, so as to rationally allocate medical resources[

31]. By means of bionic robots carrying various portable sensors to perform rapid data collection on the injured, and with the help of artificial intelligence and medical big data technology to complete rapid triage of injuries, it has important practical significance for improving the survival rate of patients in casualty incidents.

This paper designs a snake-like robot for the rapid triage of casualties with hemorrhagic shock. The robot body features a structure combining active wheels and orthogonal joints, which enables it to integrate the advantages of the high movement speed of wheeled robots and the high flexibility of jointed robots, so as to adapt to the complex terrain environment of the application scenarios. Meanwhile, the end of the robot is equipped with a visible light camera, an infrared camera, and a voice interaction system. It realizes the rapid triage of casualties with hemorrhagic shock by collecting the images, body temperature, and voice dialogue data of the injured.

2. Design of Snake-like Robot System

2.1. Structural Design of Snake-like Robot

At disaster search and rescue sites, it is necessary to design the robot's body structure to enable it to have excellent spacial obstacle-surmounting capabilities and the ability to pass through narrow spaces. A snake-like robot is a multi-degree-of-freedom chain-type robot, composed of multiple similar joint modules connected in sequence. The orthogonal joint connection mode allows the adjacent joints of the snake-like robot to be connected by a revolute pair, and the axes of two adjacent revolute pairs are in an orthogonal relationship and perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the snake's body, endowing the snake-like robot with excellent 3D movement capabilities. In addition, by flexibly increasing or decreasing the number of orthogonal joints, the length and turning radius of the snake-like robot's body can be adjusted, thereby balancing the robot's spacial obstacle-surmounting capabilities and the ability to pass through narrow spaces.

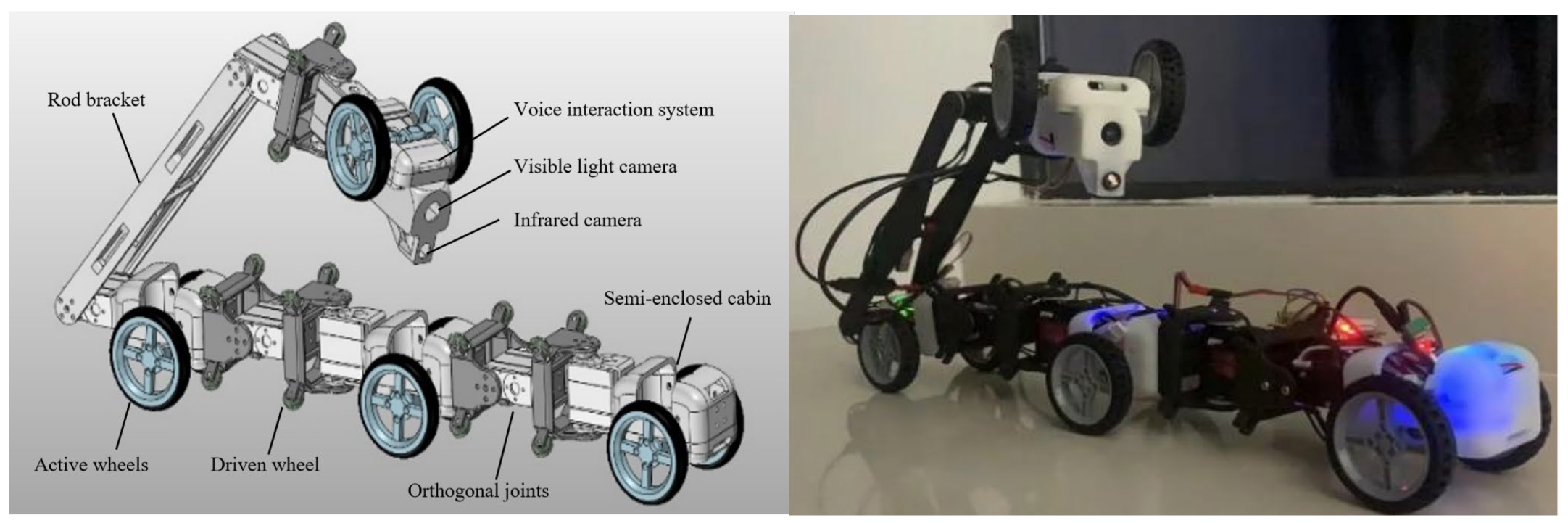

As shown in

Figure 2, this paper designs a snake-like robot. The robot body consists of 6 orthogonal axis joints connected in series and 4 sets of active wheels. The skeleton components are arranged in orthogonal connection, with driven wheels mounted on them. Each section of the orthogonal component is connected with a semi-enclosed cabin, which is used to place components such as batteries and steering gear drivers, and the active wheel structure is arranged on the side of the cabin.

The spacial obstacle-surmounting capability and the ability to pass through narrow spaces of the robot can be flexibly adjusted by increasing or decreasing the number of orthogonal joints and active wheels. Increasing the number of robot modules can extend the length of the robot body, thereby enhancing its spacial obstacle-surmounting capability. Reducing the number of robot modules can decrease the turning radius of the robot, thus improving its flexibility in narrow spaces.

To collect information of casualties with hemorrhagic shock, an information acquisition device consisting of a visible light camera, an infrared camera, and a voice interaction system is installed at the end of the snake-like robot. The information acquisition device is connected to the snake's body via a connecting rod bracket. Through the control of the steering gear at the end of the bracket, the pitch and yaw angles of the cameras can be adjusted, thereby expanding the field of view for information collection.

The workspace of this snake-like robot breaks through the limitations of the 2D plane, expanding the robot's activity range and operational flexibility. Meanwhile, combined with the complex terrain environment of practical application scenarios, based on the modular design integrating orthogonal joint connections and active wheels, it achieves 3D movement in the workspace, high-speed movement on flat terrain, planar steering and detouring, as well as the ability to cross complex terrains such as obstacles and gaps. The components of the snake-like robot are mainly made of resin materials through 3D printing, which have low shrinkage and excellent yellowing resistance. The performance parameters of the resin material are shown in

Table 1 below.

2.2. Analysis of Motion Control of Snake-like Robot

The proposed body structure, which integrates active wheels with orthogonal joints, enables the snake-like robot to combine the advantages of both wheeled robots and multi-jointed robots. On flat terrain, the active wheels provide high-speed mobility, while on rugged surfaces, the robot enhances its three-dimensional obstacle-crossing capability through adaptive undulatory movements facilitated by the orthogonal joints. The mathematical model governing the serpentine motion of the robot is expressed in Equation (1).

In formula (1), is the angle of the i-th yaw joint of the robot at time t; is the angle of i-th pitch joint of the robot at time t; are parameters of the wavy motion trajectory; is the optimize parameter for robot motion.

The turning motion control function of the snake-like robot is shown in Equation (1),

In formula (2), is the angle of the i-th yaw joint of the robot at time t; is the angle of i-th pitch joint of the robot at time t; are turning motionparameters; is the optimize parameter for robot motion.

The control method for the lifting motion of the snake-like robot is to directly lift n of its joints. Enabling the lifting of the head joints of the snake-like robot can greatly expand the field of view and improve the practical performance of the robot. The lifting motion of the front joints has practical research significance for the snake-like robot to enter the photographing working mode. The rotation curve planning of each pitching joint during the lifting motion is shown in Equation (3).

In formula (3), is the rotation value of the first pitch joint; is the rotation value of the first pitch joint; is the waving motion amplitude parameter, is the adjust parameters around the rotation center.

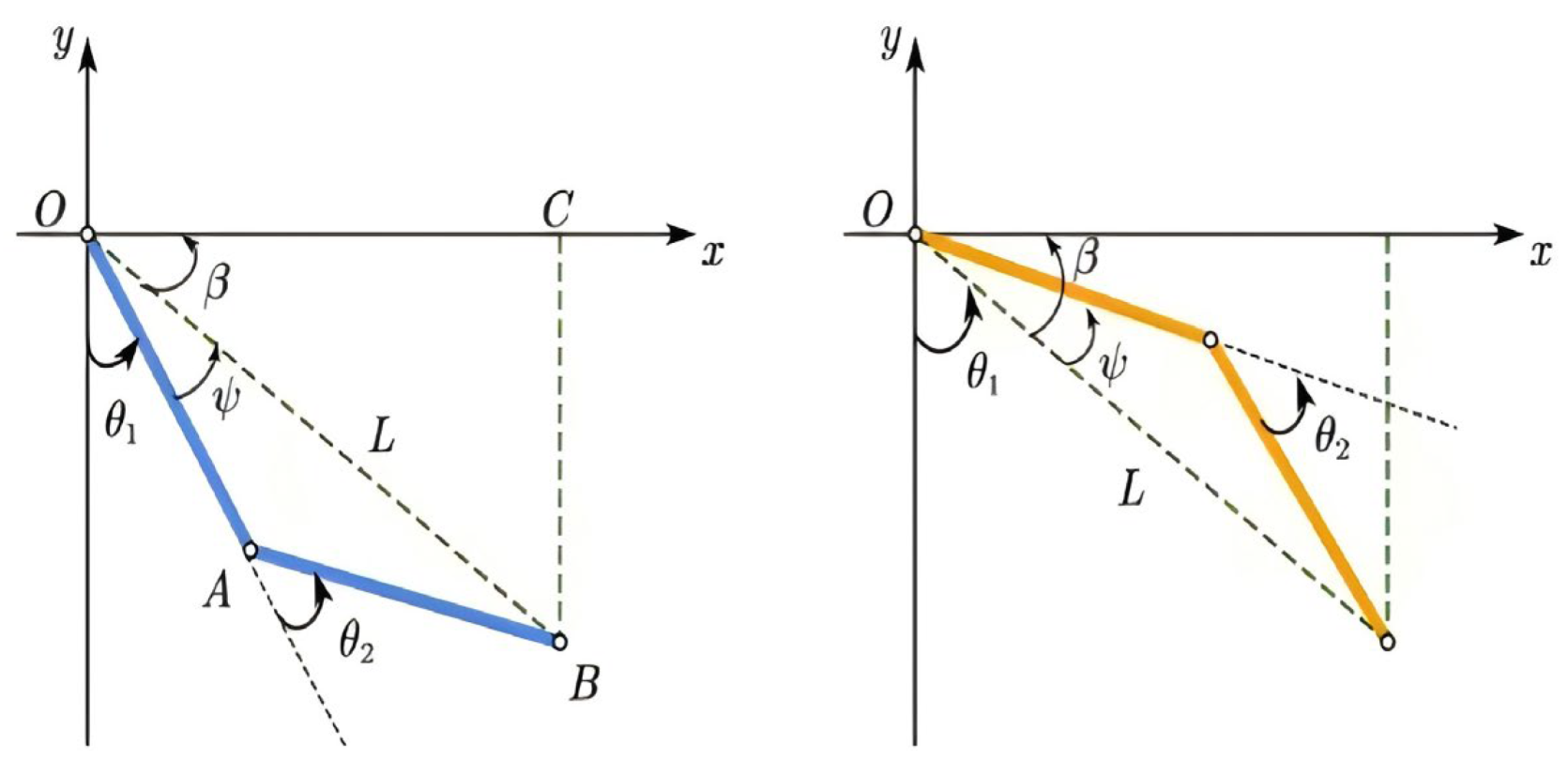

The inverse kinematics of the snake-like robot can be solved by the geometric method. According to the analysis of head motion control, the head pitching motion of the snake-like robot can be regarded as a two-link mechanism, taking the right pose in

Figure 3 as an example.

Since the actual lengths of the link mechanisms in the snake's head are almost equal, they are assumed to be an isosceles two-link mechanism for the convenience of calculation. In triangle OAB, according to the cosine theorem, it can be obtained that

According to the Pythagorean theorem, it can be derived that

Since the actual rotation angle of the first axis of the two-link mechanism is

, the formula for the rotation angle of axis 1 is as follows:

Since this mechanism is an isosceles two-link mechanism, the angle of

can be regarded as

. Therefore, the formula for the rotation angle of axis 2 is as follows:

Compared with the DH method, the calculation of the robot's inverse solution using the geometric method is simpler and more intuitive. By adjusting the angles of the two links, the information acquisition module can be adjusted at different angles.

2.3. Design of the Control System for Snake-like Robot

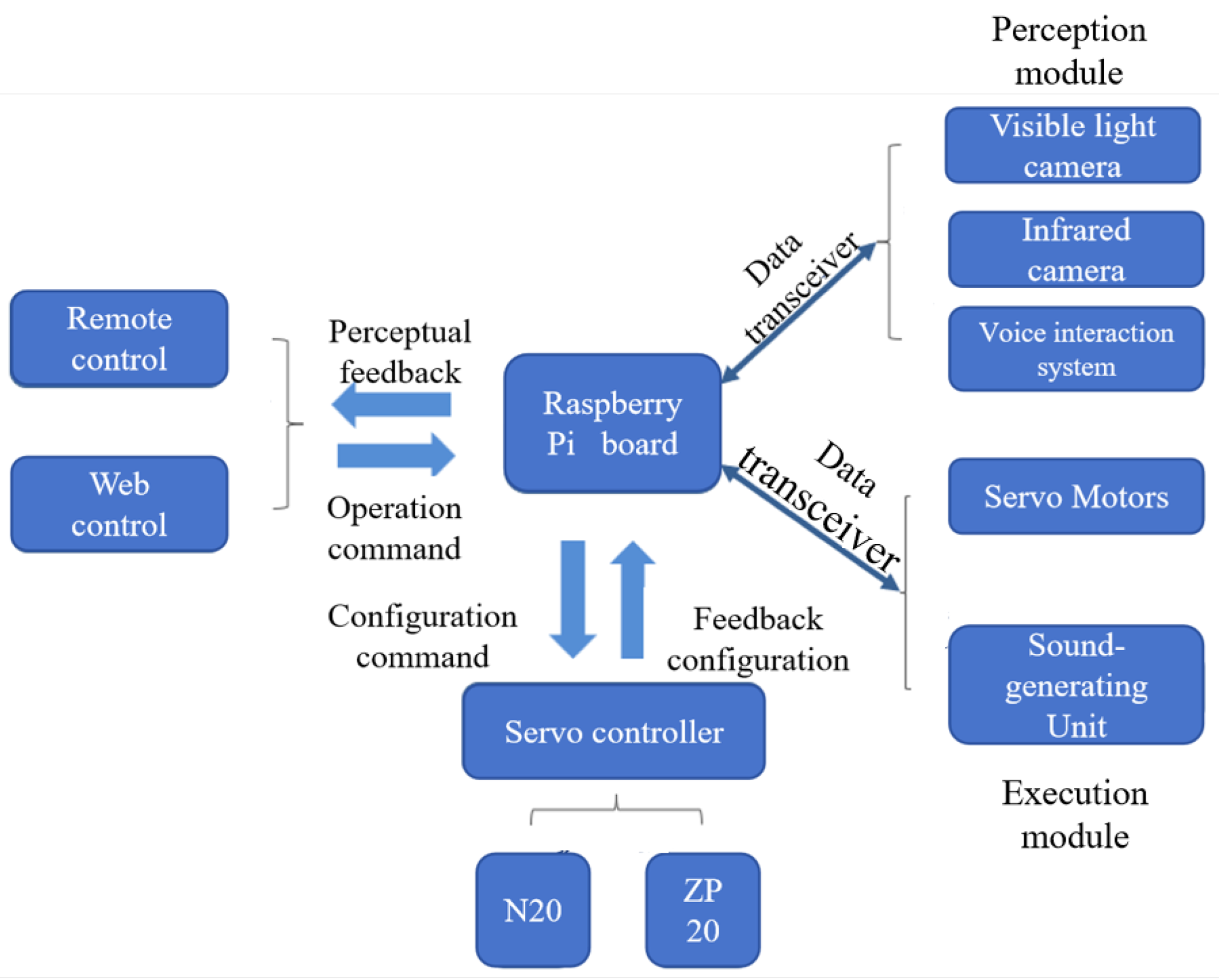

The control system of the snake-like robot is shown in

Figure 4, which mainly consists of three parts: a human-computer interaction module, a perception module, and motion control module. Each module is connected to the Raspberry Pi 4B control board. The human-computer interaction module has two working modes. One is using a remote control handle based on 2.4G wireless technology as the remote controller of the snake-like robot, with a stable remote control distance of about 25 meters. The imaging information from the visible light camera is obtained through the Raspberry Pi remote desktop, allowing the operator to perform operations such as moving forward, backward, turning left, turning right, and surmounting obstacles using the handle. The other mode is human-computer interaction through information transmission via WIFI, using a web service deployed in the Raspberry Pi. The remote control handle can be used for controlling the snake-like robot at close range; when the snake-like robot works at a long distance or outside the line of sight, remote control can be performed through the web interface.

The perception module is installed at the tail of the snake-like robot and mainly consists of a visible light camera, a thermal imaging camera, and a voice interaction system. The visible light camera is mainly used for visual feedback to the remote operator and capturing the physical condition of casualties with hemorrhagic shock, connected via a USB interface. The infrared camera is mainly used to assist in searching for casualties with hemorrhagic shock and obtaining their body temperature, connected to the Raspberry Pi through a USB-to-serial port. The voice interaction system is mainly used for real-time voice communication between the operator and the casualties. The snake-like robot is equipped with a speaker module and a sound-receiving module, connected via a USB interface. The remote operator can communicate with the casualties through a paired Bluetooth headset, and the voice responses of the casualties can be saved for analyzing their injury conditions.

The steering gear drive and control module is mainly used to control the active wheel steering gears and orthogonal joint steering gears of the snake-like robot. To reduce the number of cables in the robot, all steering gears adopt bus steering gears, which are connected to the Raspberry Pi through a USB-to-serial port. A total of 14 steering gears are used for the active wheels and orthogonal joints, which can be connected in series with only one serial cable. Compared with traditional PWM steering gears, this saves the internal wiring space of the robot, improves the stability of steering gear connections, and enables feedback and protection control of the steering gear's current, position, and speed. The active wheel bus steering gears use TBS-K20 metal digital steering gears, which work in speed motion mode and can rotate infinitely. The orthogonal joints of the snake-like robot use ZP30D serial bus steering gears as drivers, working in position control mode to adjust the 3D posture of the robot.

3. Experiments and Analysis

3.1. Experiment on Motion Performance of Snake-like Robot

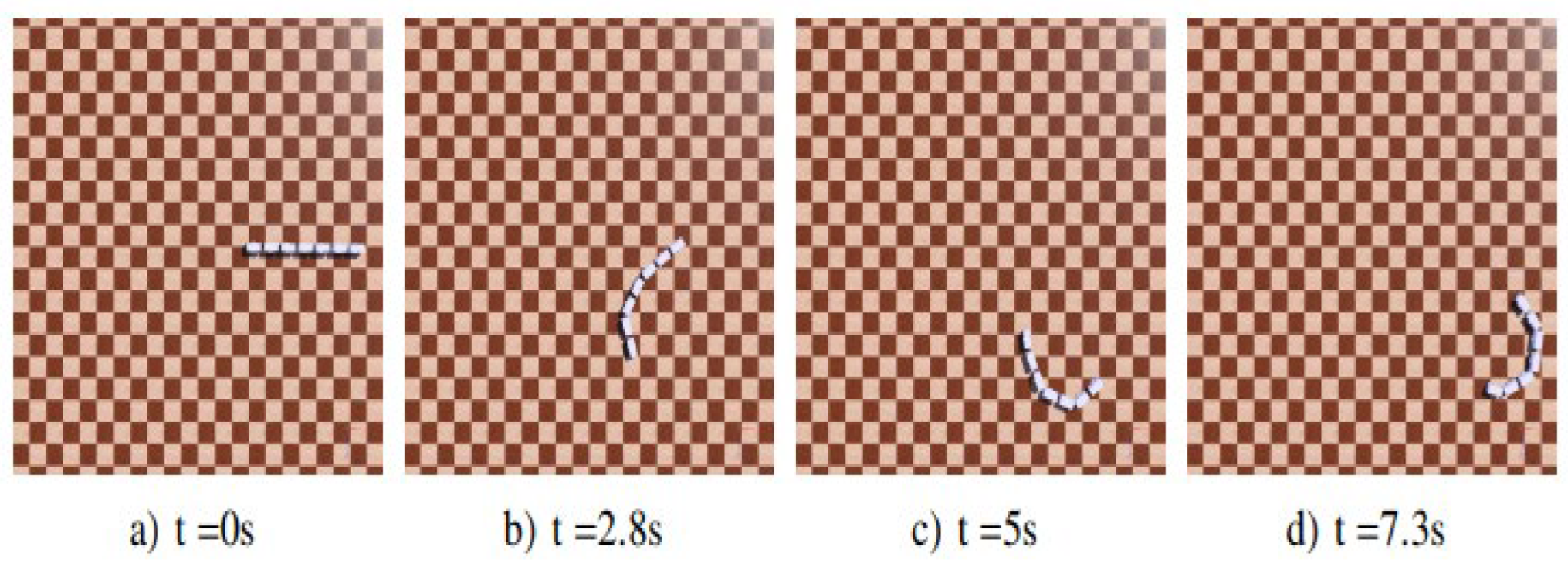

3.1.1. Simulation and Analysis of the Snake-like Robot

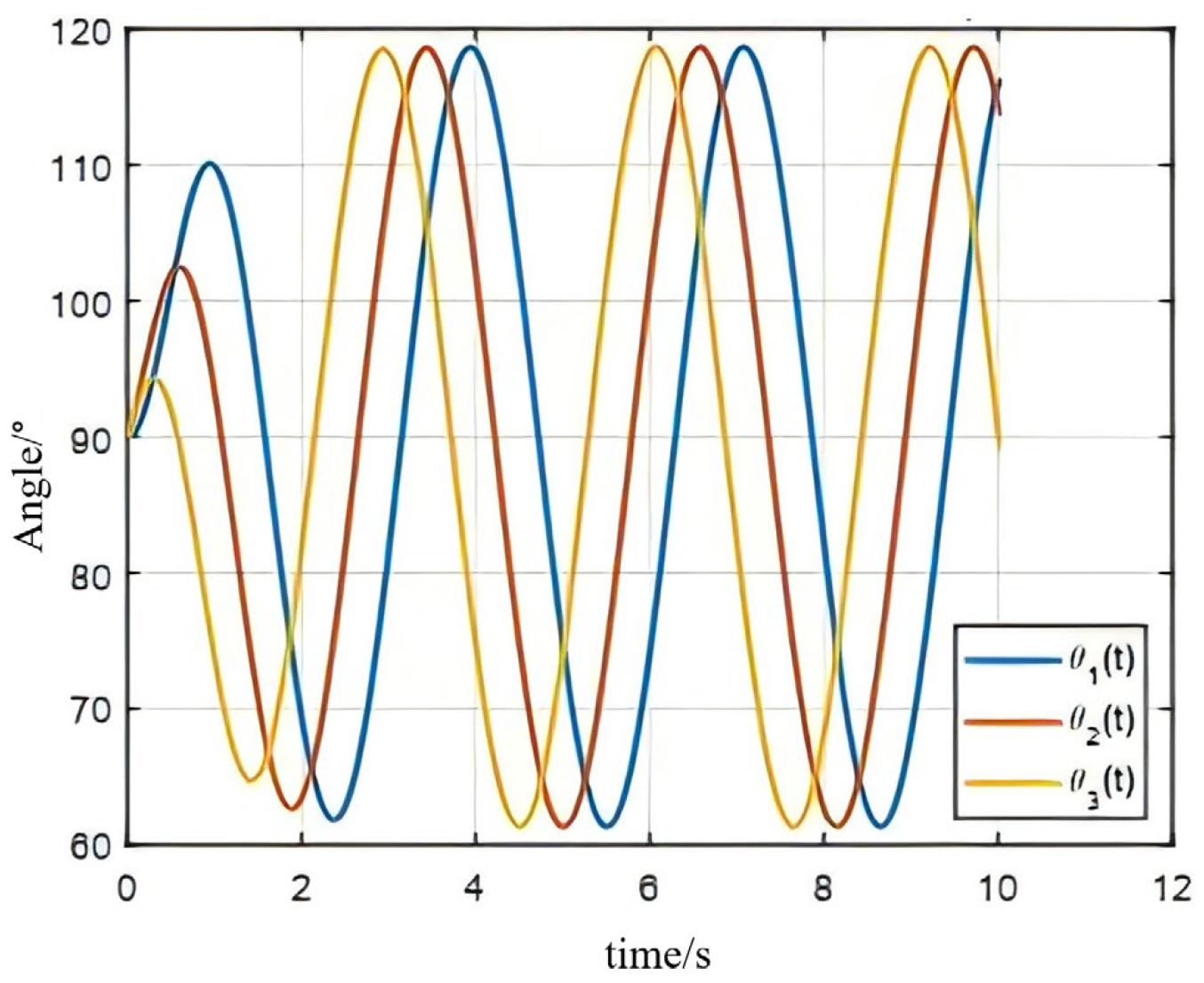

According to Equation (1),

α=0.5rad、

ω=2rad/s、

β=1rad, and the optimized parameter

η=2 are taken. The changes of each joint Angle are shown in

Figure 5, and the simulation results in Webots software are shown in

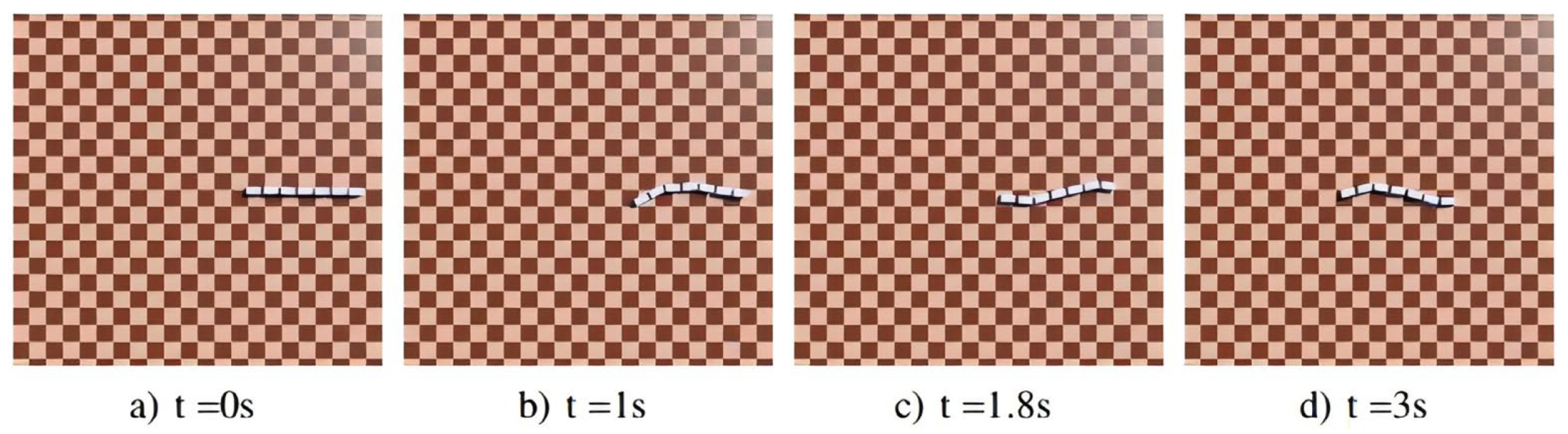

Figure 6.

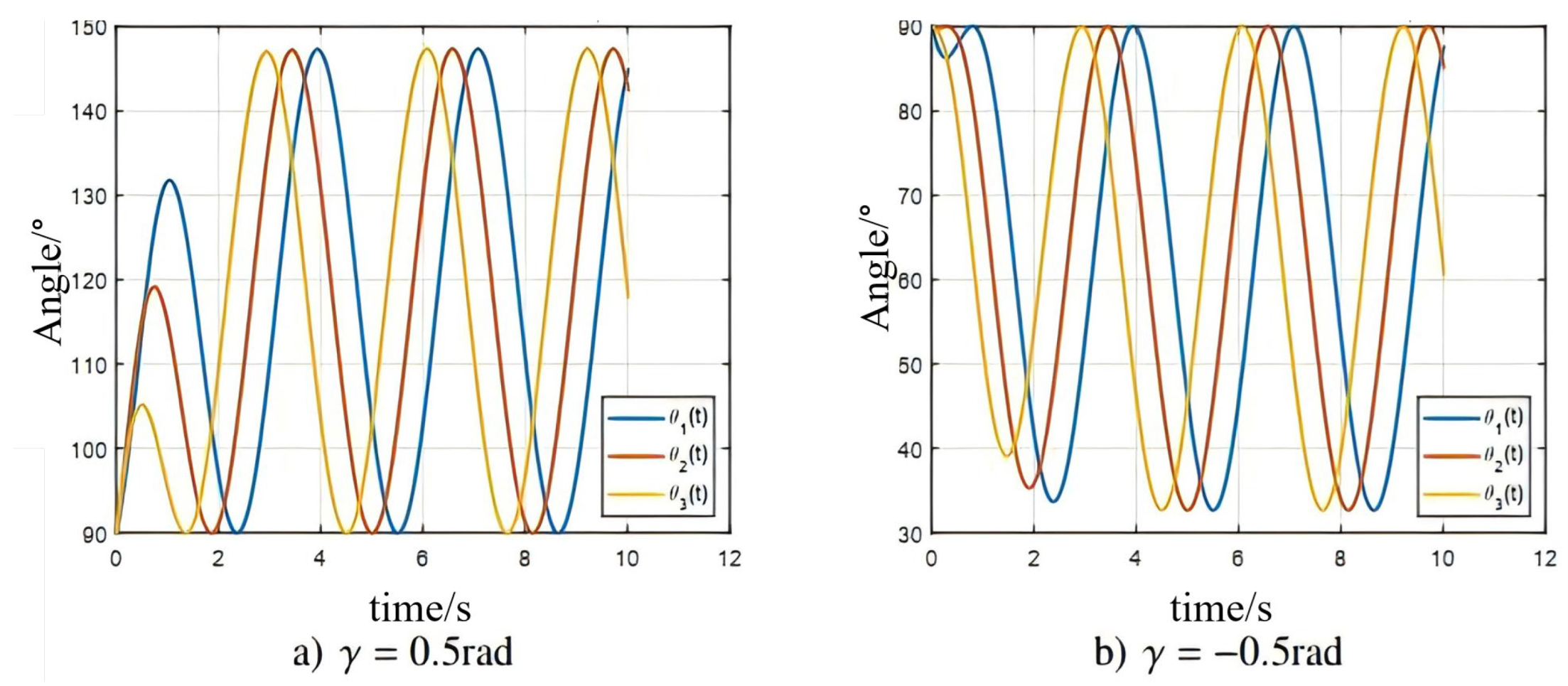

According to Equation (2), the control parameters are

α=0.5rad、

ω=2rad/s、

β=1rad、

η=2, set

γ=0.5 rad and

γ=-0.5 rad, the angular changes of each yaw joint are shown in

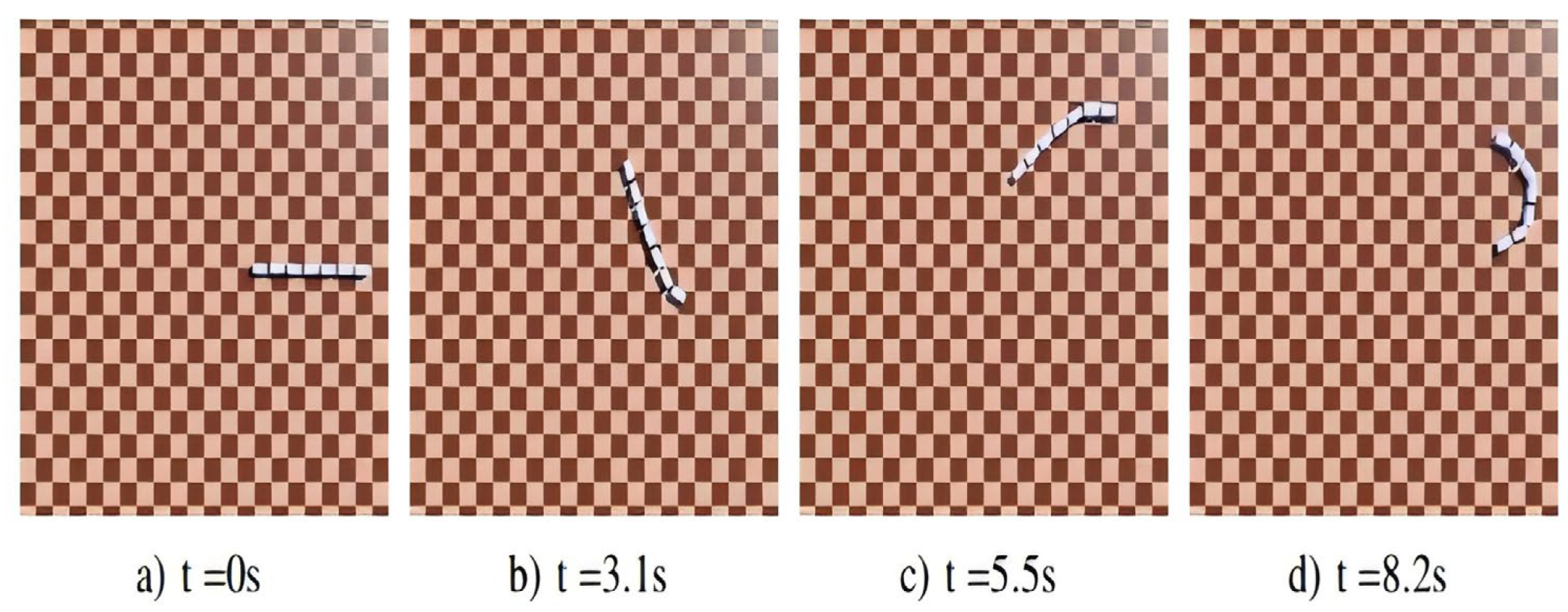

Figure 7. The simulation results in Webots software are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

The simulation results demonstrate that by adjusting the undulatory and turning motion parameters of the robot, we can effectively modulate three key characteristics of the snake-like robot's locomotion: the lateral oscillation amplitude, forward velocity, and turning radius. Furthermore, when combined with coordinated control of the active wheels, this approach significantly enhances the robot's mobility on rugged terrain, achieving both higher movement speeds and reduced turning radii.

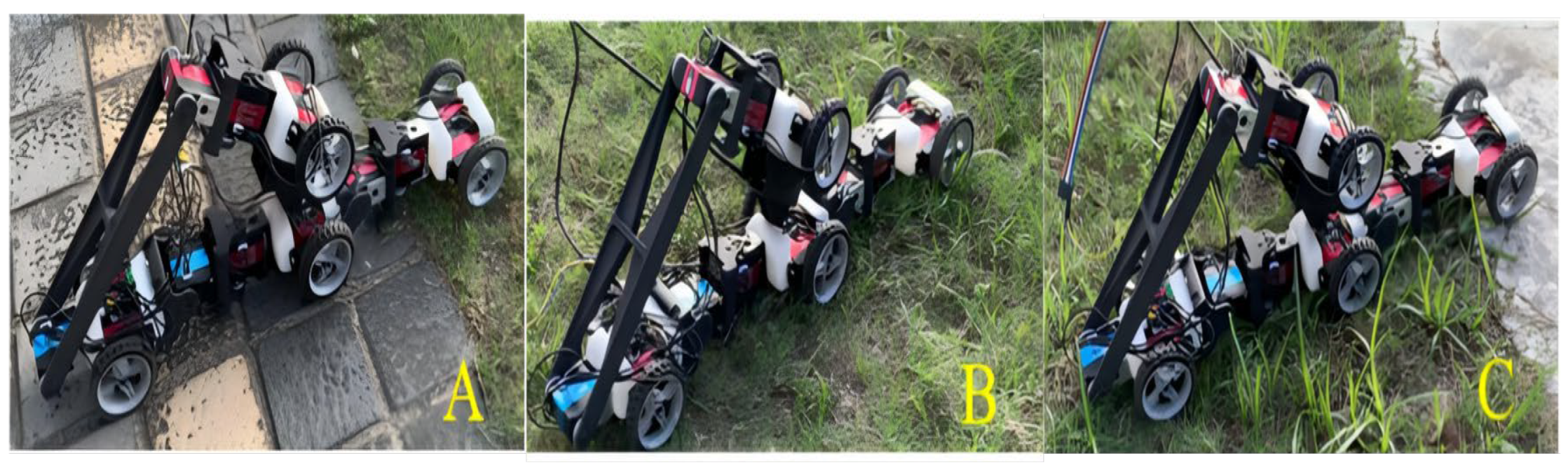

3.1.2. Outdoor Grassfield Experiments and Analysis

Outdoor grassfield experiments are shown in

Figure 10. Most of the plants in the grassland are gramineous herbs. The grass leaves take root in the soil, making the contact surface relatively soft, which requires the active wheels of the snake-like robot to have good grip. The experimental results show that the soft ground provides a certain resistance to the robot's active wheels, requiring additional power and effort to overcome. In addition, plants in the grassland may also get entangled in the robot's components, increasing the maintenance and cleaning work of the robot.

3.1.3. Outdoor Experiment and Analysis on Gravel Ground

In disaster sites, there are many complex environments with sandy and gravel terrain. An irregular cobblestone river course was selected as the experimental site, as shown in

Figure 11. Thanks to the combined movement of the active wheels and orthogonal joints, the snake-like robot is provided with strong power. Moreover, the deformation of the orthogonal joints enables the snake-like robot to well conform to the contour changes of the sandy and gravel river course, allowing it to move relatively smoothly in such an environment. Its flexibility and adaptability enable the snake-like robot to find a suitable body posture in sandy and gravel terrain, so as to pass through narrow passages, climb inclined surfaces and cross irregular obstacles.

3.1.4. Experiment and Analysis on Step Obstacle Surmounting

In disasters, people are easily trapped in buildings, where there are often obstacles of varying heights such as steps. In this experiment, a step with a height of 30cm was selected, as shown in

Figure 12. The snake-like robot can successfully surmount the step of this height through posture adjustment. The snake-like robot flexibly adjusts its body posture, lifting and twisting its body to adapt to the height and shape of the step. Through such posture adjustment, the robot can overcome the height difference of the step and smoothly cross the obstacle.

3.1.5. Experiment and Analysis on Gap Crossing

In disasters such as earthquakes and explosions, there are often terrains with relatively wide gaps. The ability to cross gaps independently without external assistance is a test for the snake-like robot designed in this paper. In the gap-crossing test, a 35cm-wide gap was set up, as shown in

Figure 13. By adjusting its body posture and movement mode to adapt to the width and shape of the gap, the snake-like robot flexibly stretched and contracted its body, successfully crossing the gap.

Seven indicators were set in the snake-like robot test, namely walking speed, minimum passable hole size, climbing angle, obstacle-surmounting height, passable step size, ditch-crossing width, and turning radius. The results of the motion experiment data are shown in

Table 2. It can be seen from the data in

Table 2 that the maximum linear movement speed of the snake-like robot is 0.28 m/s, it can pass through a minimum hole of 0.15 m × 0.15 m, climb a slope of 40 degrees, surmount obstacles with a vertical height of 0.35 m, and climb steps with a height of 0.3 m and a width of 0.26 m. In terms of ditch-crossing width, the robot can cross ditches with a maximum width of 0.5 m. Regarding the turning radius, the robot's turning radius is 0.25 m, all of which meet the design indicators.

3.2. Non-Contact Sensing Information Acquisition Experiment

3.2.1. Voice Information Acquisition and Analysis

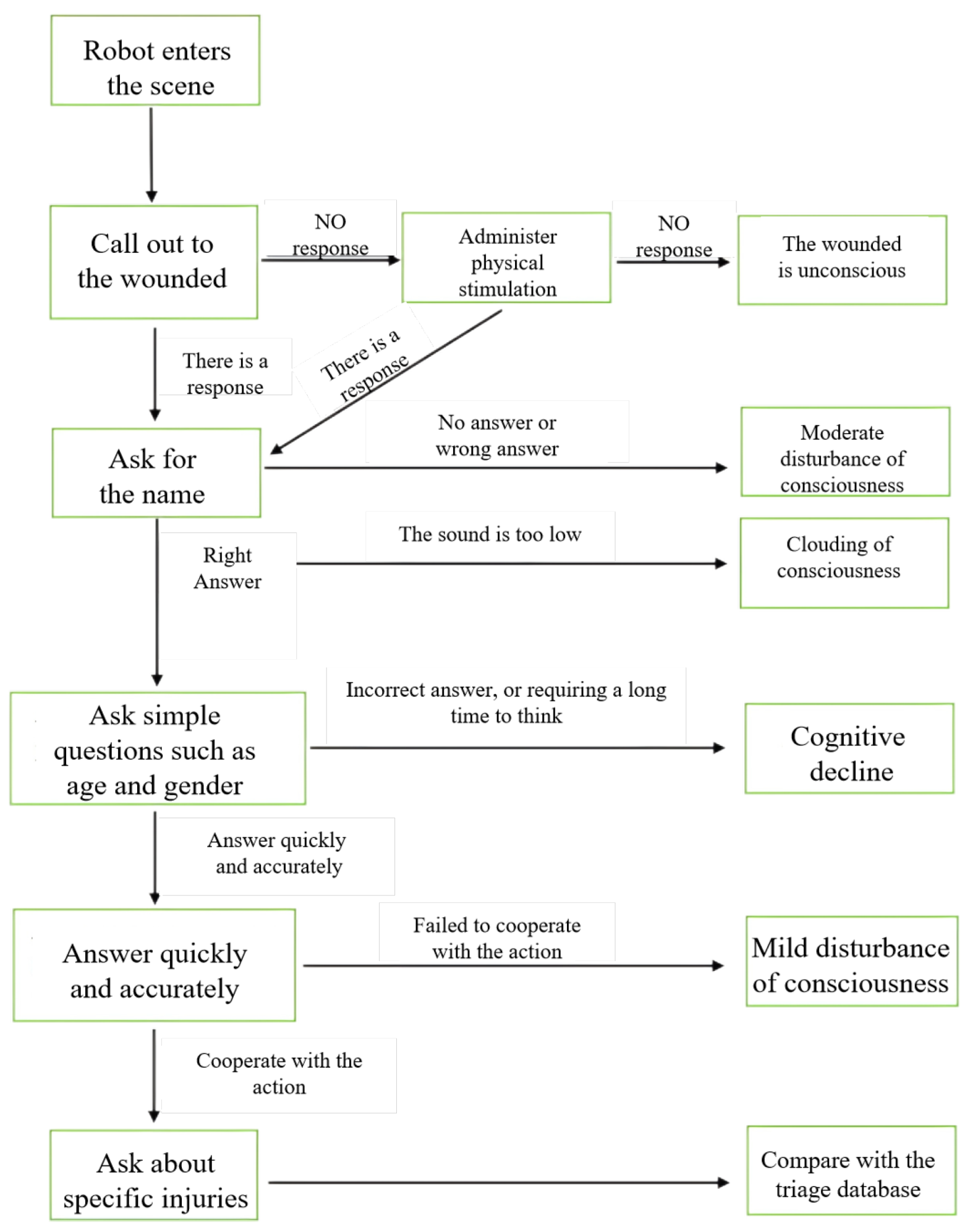

The head of the snake-like robot is equipped with a microphone and a loudspeaker, allowing the operator to communicate remotely with the wounded via a head-mounted headset. After locating the wounded, to meet the needs of triaging hemorrhagic shock casualties, a standard voice question-and-answer process was designed as shown in

Figure 14. This process sequentially involves inquiring about information such as whether the wounded can respond vocally, whether they can state their name, whether they can answer simple mathematical operation questions, and the volume of their responses. The entire dialogue process is recorded and saved.

3.2.1 Camera and Infrared Vision Acquisition and Analysis

The head of the snake-like robot is equipped with a visible light camera and an infrared camera. Operators can view the collected images on a portable display within a certain distance to obtain information about the surrounding environment of the snake-like robot. It is the visible light and infrared vision image acquisition along with the WEB-based remote control interface. Operators can remotely control the snake-like robot through the WEB interface, and at the same time, save the image information of the wounded for the rapid screening of injuries by the triage terminal software.

4. Conclusions

This paper designs a snake-like robot for the rapid triage of casualties with hemorrhagic shock. Through the structural design combining active wheels and orthogonal joints, it can take into account the advantages of high movement speed of wheeled robots and high flexibility of joint robots, so as to adapt to the complex terrain environment of application scenarios. Experiments on grassland, gravel ground, and step obstacle surmounting were conducted to verify seven indicators of the snake-like robot, including walking speed, minimum passable hole size, climbing angle, obstacle-surmounting height, passable step size, ditch-crossing width, and turning radius. Meanwhile, the end of the robot is equipped with a visible light camera, an infrared camera, and a voice interaction system, which realizes the rapid triage of casualties with hemorrhagic shock by collecting the visible light, infrared, and voice dialogue data of the casualties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and Y.L.; methodology, Z.L.; software, R.S.; validation, R.S..; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, R.S.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, Z.L..; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, Z.L.; visualization, Z.L.; supervision, Y.L.; project administration, Y.L.; funding acquisition, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by (1)National Key R&D Program of China, Intelligent Robot Special Project "Principles and Technologies for Online Triage of Autonomous Search and Rescue Robots" (SQ2020YFB130197);(2)University-level Project of Shenzhen Polytechnic University, "Research on Key Technologies of Motion Control for Dual-arm Assembly Robots with Flexible Components in 3C Industry" (6022312001K);(3)University-level Project of Shenzhen Polytechnic University, "Study on Coupling Characteristics and Decoupling Control Mechanism of Pose Contour Error in Multi-axis Servo Systems" (6022310021K).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available as the study will continue on this basis.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Hailong Zhang, Kaiwen Cheng, Jiarui Li and Jiabao Liu from Shenzhen Polytechnic University for their contributions to the development of the prototype.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bhange A D, Badhiye S S, Kamble R A, et al. Enhancing military training through augmented and virtual reality systems[C]//2024 4th international conference on technological advancements in computational sciences (ICTACS). IEEE, 2024: 948-953.

- Kabilijiang W, Changjiu W, Kato T, et al. Research on Postearthquake Rural Housing Reconstruction and Subsequent Evaluation in Dujiangyan on the 15th Anniversary of the Wenchuan Earthquake[J]. Natural Hazards Review, 2025, 26(3): 05025004. [CrossRef]

- Bazyar J, Farrokhi M, Salari A, et al. Accuracy of triage systems in disasters and mass casualty incidents; a systematic review[J]. Archives of academic emergency medicine, 2022, 10(1):e32.

- Yang X, Zheng L, Lü D, et al. The snake-inspired robots: a review[J]. Assembly Automation, 2022, 42(4): 567-583.

- Hirose, S.; Yamada, H. Snake-like robots [Tutorial]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2009, 16, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Mehta R K, Yadav A, Murphy R R, et al. Human-Robot Team Vulnerabilities under Fatigue during sUAS Disaster Response Simulations[C]//2024 IEEE International Symposium on Safety Security Rescue Robotics (SSRR). IEEE, 2024: 98-103.

- Lin T H, Huang J T, Putranto A. Integrated smart robot with earthquake early warning system for automated inspection and emergency response[J]. Natural hazards, 2022, 110(1): 765-786.

- Chung T H, Orekhov V, Maio A. Into the robotic depths: Analysis and insights from the darpa subterranean challenge[J]. Annual Review of Control, Robotics, and Autonomous Systems, 2023, 6(1): 477-502.

- Shang L, Wang H, Si H, et al. Investigating the obstacle climbing ability of a coal mine search-and-rescue robot with a hydraulic mechanism[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(20): 10485.

- Orita Y, Takaba K, Fukao T. Human tracking of a crawler robot in climbing stairs[J]. Journal of Robotics and Mechatronics, 2021, 33(6): 1338-1348. [CrossRef]

- Kono H, Isayama S, Koshiji F, et al. Automatic Flipper Control for Crawler Type Rescue Robot using Reinforcement Learning[J]. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications, 2024, 15(6). [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Cheng J, Wang C, et al. Research on Temporary Support Robot for the Integrated Excavation and Mining System of Section Coal Pillar[J]. Applied Sciences, 2025, 15(9): 4896.

- An G, Kang J. Novel design of GFRP beam spring rocker-arm suspension for 6-wheeled mobile robots[J]. Mechatronics, 2025, 110: 103388. [CrossRef]

- WANG H, LI C, LIANG W, et al. Path planning of wheeled coal mine rescue robot based on improved A* and potential field algorithm[J]. Coal Science and Technology, 2024, 52(8): 159-170.

- Li Q, Cicirelli F, Vinci A, et al. Quadruped Robots: Bridging Mechanical Design, Control, and Applications[J]. Robotics, 2025, 14(5): 57.

- Cruz Ulloa C, del Cerro J, Barrientos A. Mixed-reality for quadruped-robotic guidance in SAR tasks[J]. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, 2023, 10(4): 1479-1489.

- Arunkumar V, Rajasekar D, Aishwarya N. A review paper on mobile robots applications in search and rescue operations[J]. Advances in Science and Technology, 2023, 130: 65-74.

- Cruz Ulloa C, Prieto Sánchez G, Barrientos A, et al. Autonomous thermal vision robotic system for victims recognition in search and rescue missions[J]. Sensors, 2021, 21(21): 7346.

- Berdibayeva G, Bodin O, Ozhikenov K, et al. Bionic Method for Controlling Robotic Mechanisms during Search and Rescue Operations[J]. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Robotics Research, 2021, 10(3): 128-136. [CrossRef]

- Wang R, Wang M, Zuo L, et al. The Collaborative Multi-target Search of Multiple Bionic Robotic Fish Based on Distributed Model Predictive Control[J]. Journal of Bionic Engineering, 2025, 22(3): 1194-1210. [CrossRef]

- Shang L, Wang H, Si H, et al. Investigating the obstacle climbing ability of a coal mine search-and-rescue robot with a hydraulic mechanism[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(20): 10485.

- Seeja G, Doss A S A, Hency V B. A survey on snake-like robot locomotion[J]. IEEE Access, 2022, 10: 112100-112116.

- Yang Z, Fang Z, Yang S, et al. Research on the Spiral Rolling Gait of High-Voltage Power Line Serpentine Robots Based on Improved Hopf-CPGs Model[J]. Applied Sciences (2076-3417), 2025, 15(3).

- Li H, Wang H, Cui L, et al. Design and experiments of a compact self-assembling mobile modular robot with joint actuation and onboard visual-based perception[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(6): 3050.

- Leggieri S, Canali C, Caldwell D G. Design of the crawler units: toward the development of a novel hybrid platform for infrastructure inspection[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(11): 5579.

- Canali C, Pistone A, Ludovico D, et al. Design of a novel long-reach cable-driven hyper-redundant snake-like manipulator for inspection and maintenance[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(7): 3348. [CrossRef]

- Qin G, Wu H, Ji A. Equivalent Dynamic Analysis of a Cable-Driven Snake Arm Maintainer[J]. Applied Sciences, 2022, 12(15): 7494. [CrossRef]

- Bao L, Sun Y, Wang Q, et al. Study on head stabilization control strategy of non-wheeled snake-like robot based on inertial sensor[J]. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(7): 4477. [CrossRef]

- Kim S J, Suh J H. Adaptive robust RBF-NN nonsingular terminal sliding mode control scheme for application to snake-like robot’s head for image stabilization[J]. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(8): 4899.

- Chitikena H, Sanfilippo F, Ma S. Robotics in search and rescue (sar) operations: An ethical and design perspective framework for response phase[J]. Applied Sciences, 2023, 13(3): 1800. [CrossRef]

- Pantalone D, Chiara O, Henry S, et al. Facing trauma and surgical emergency in space: hemorrhagic shock[J]. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2022, 10: 780553. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).