Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

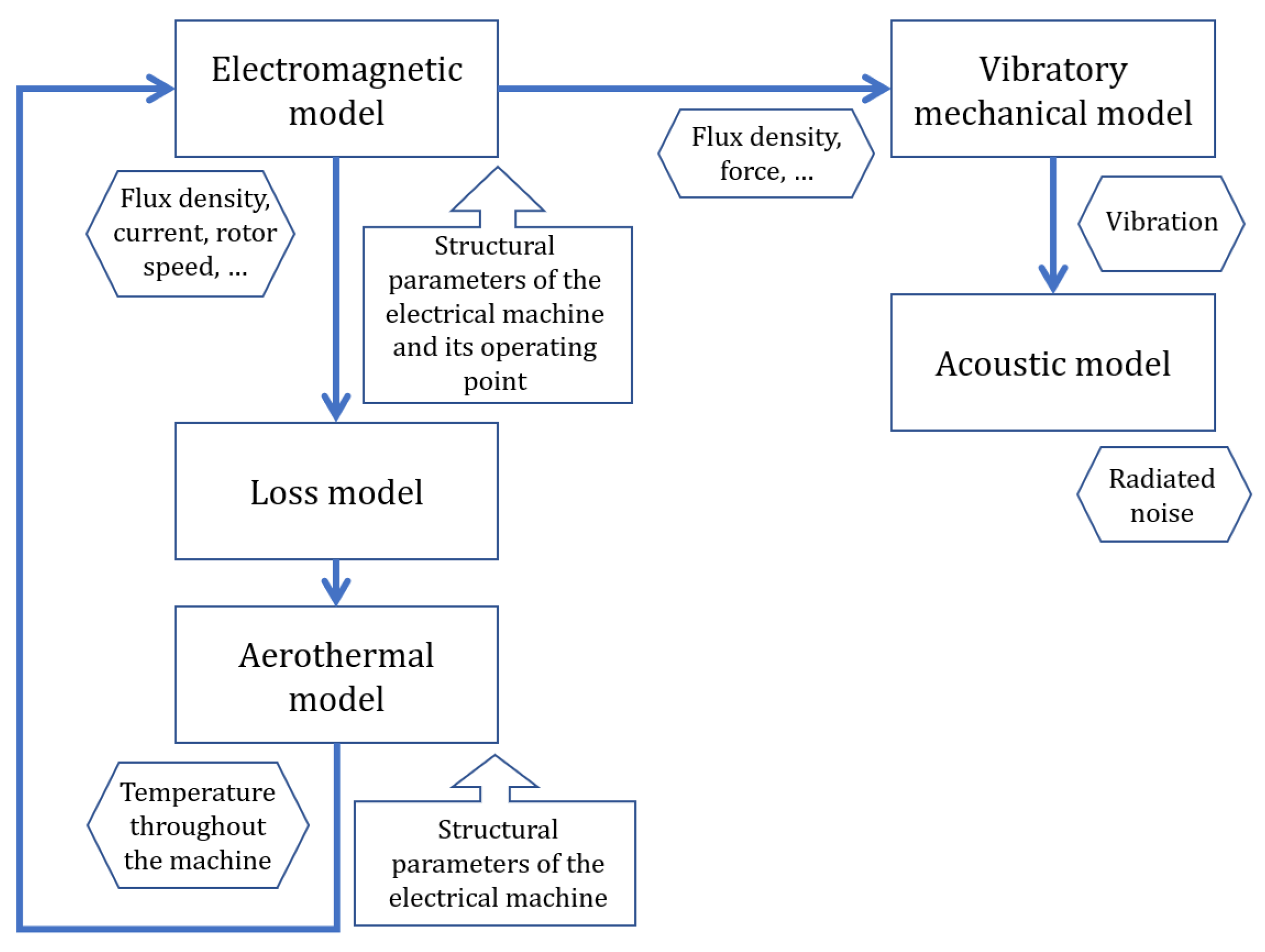

2. Electrical Machine Digital Twin

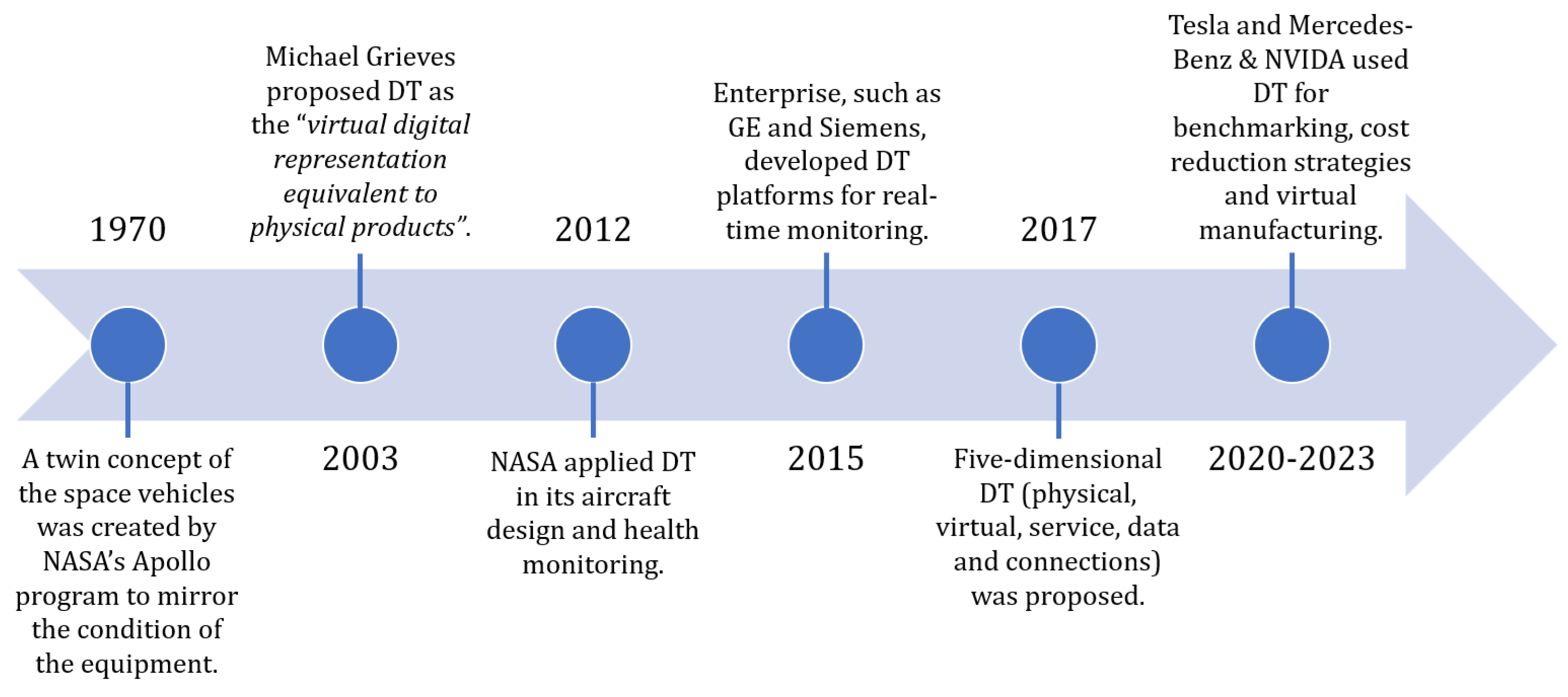

2.1. Digital Twin Definition

2.2. Electrical Machine DT Realization

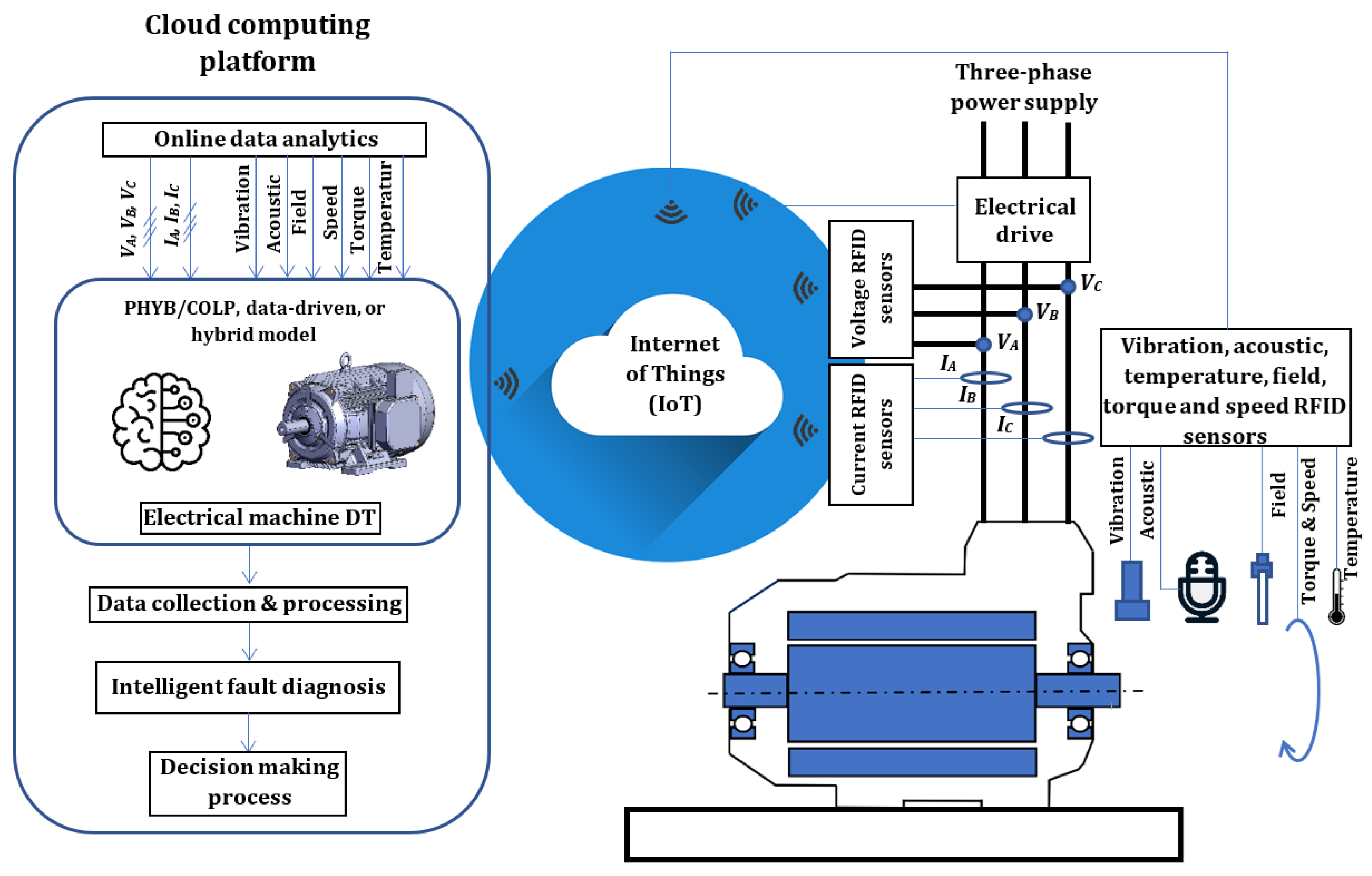

- The DT of an electrical machine is a synchronized, ultra-fidelity replica of it, incorporating multiphysics, multiscale, and probabilistic modeling.

- An automated, bidirectional, real-time flow of data occurs between the DT and the electrical machine through appropriate instrumentation and the IoT platform.

- The twin encompasses data from the service stage of the electrical machine’s lifecycle and remains connected to this phase through to the retirement stage.

3. Electrical Machines DRTS Challenges

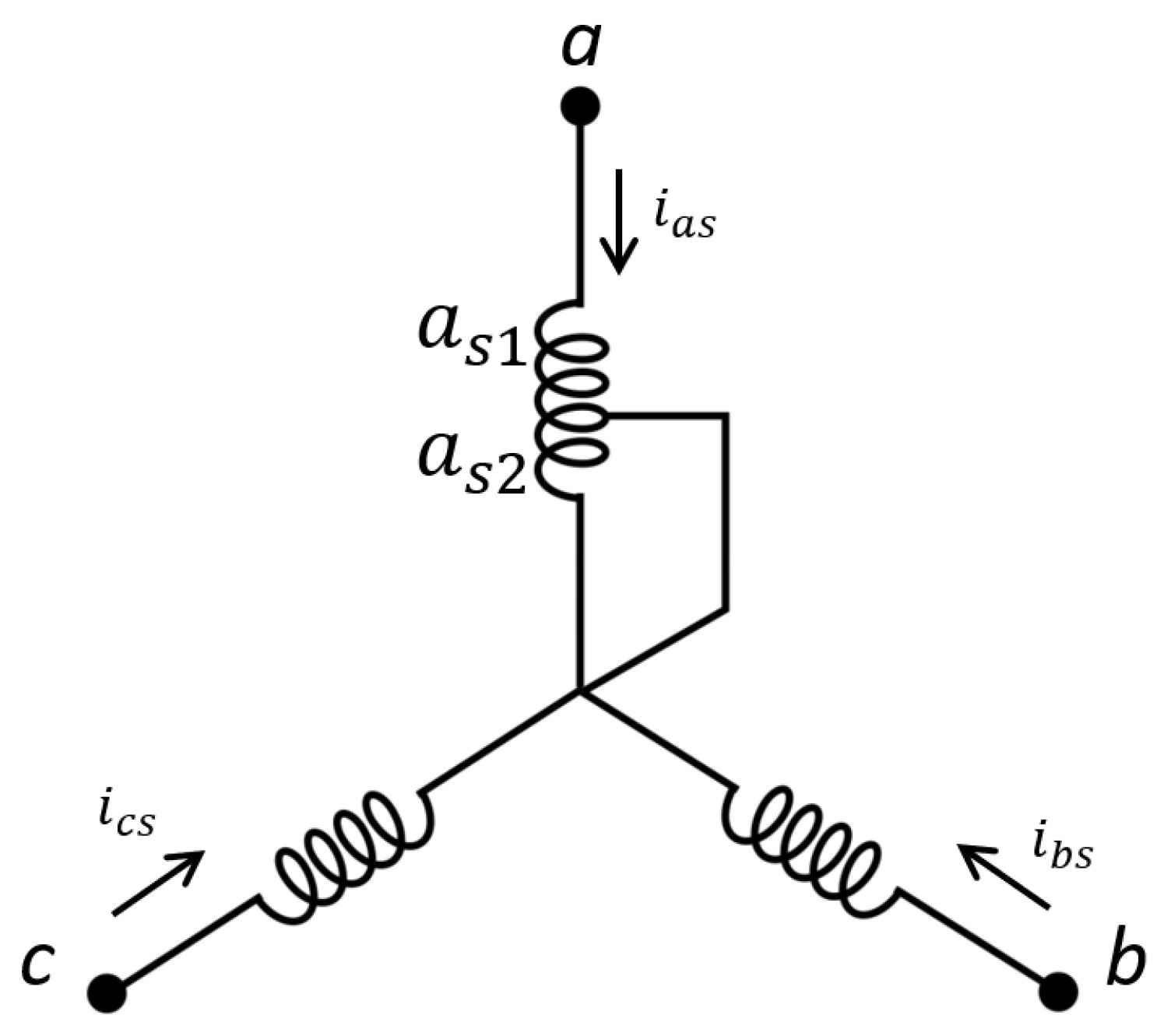

3.1. Electrical Machine Models

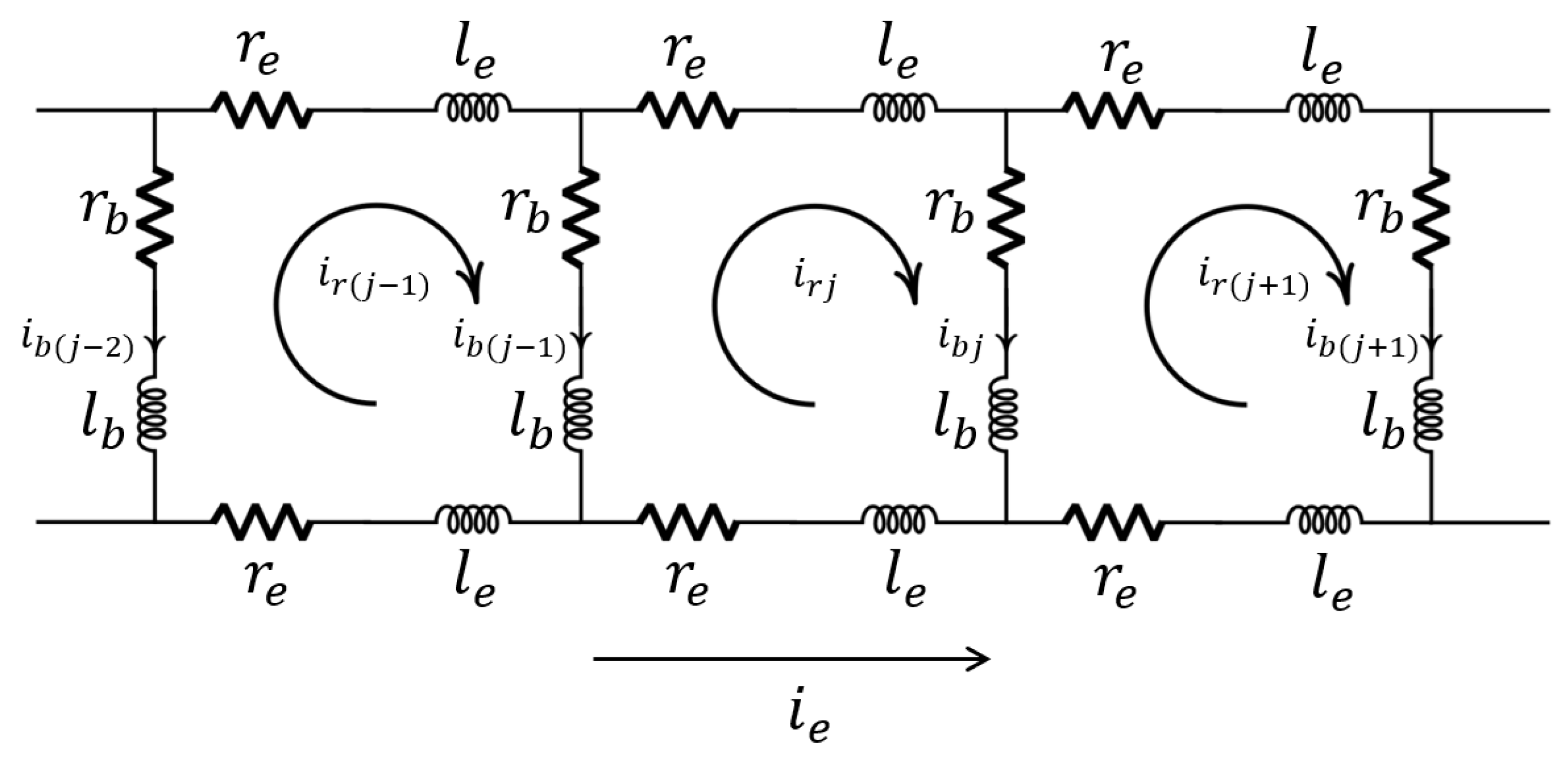

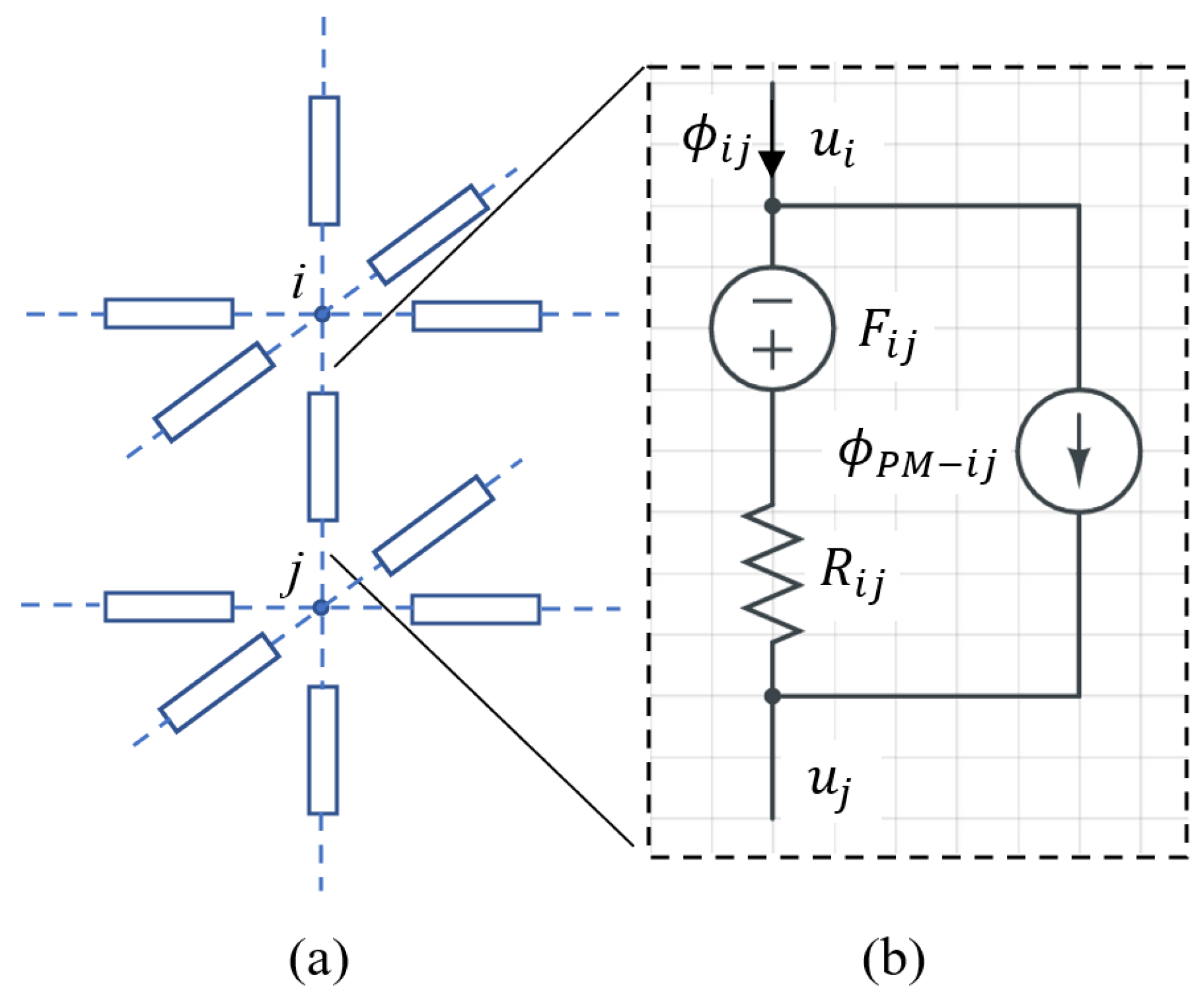

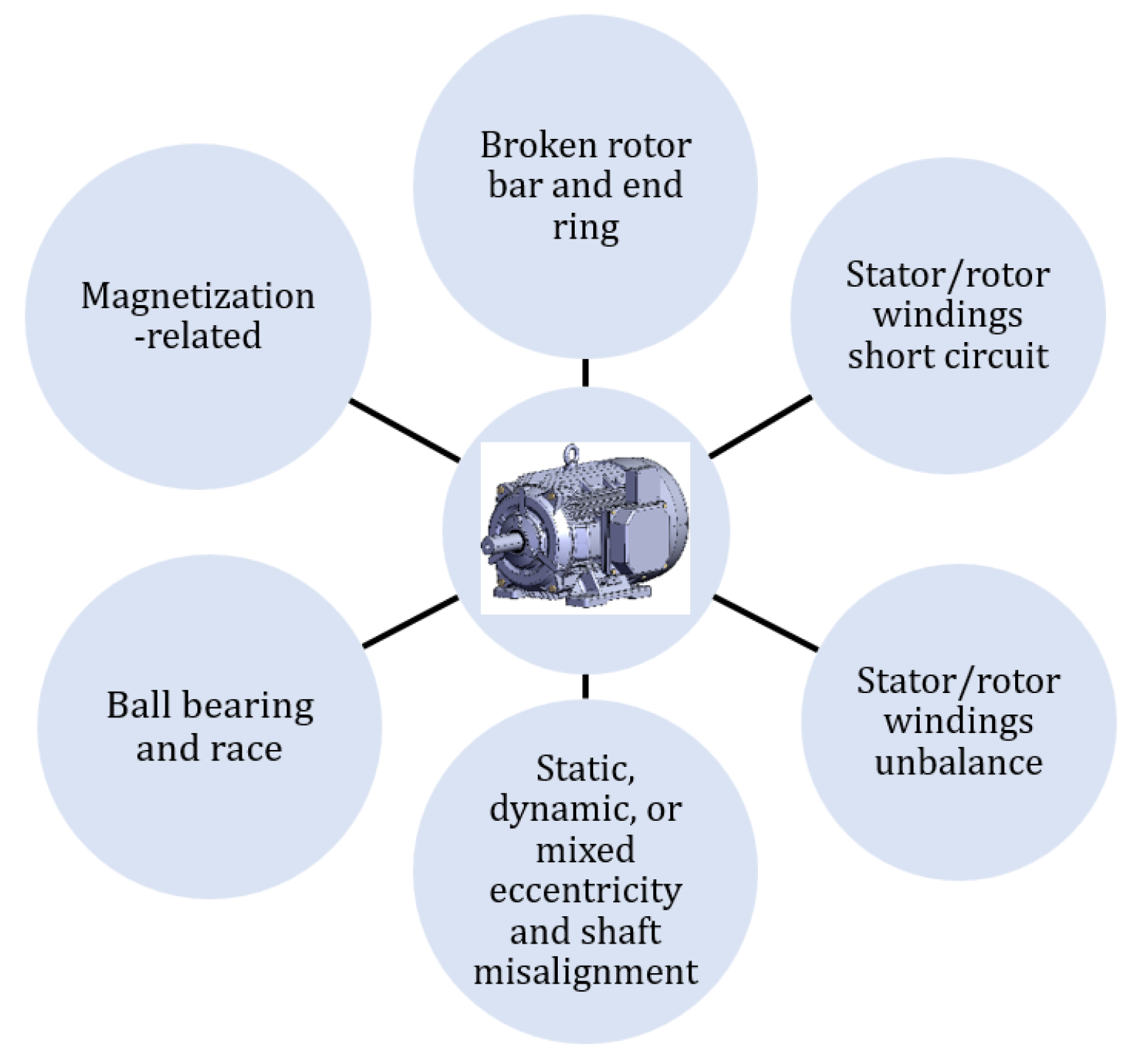

| Fault types | References |

|---|---|

| Broken rotor bar and end ring | [54,55,56,57,58,59] |

| Stator/rotor windings unbalance | [60] |

| Stator/rotor windings short circuit | [14,55,56,61,62,63,64] |

| Static, dynamic or mixed eccentricity | [55,65] |

| Ball bearing and race | [66] |

| Magnetization-related | [67] |

| Fault types | References |

|---|---|

| Broken rotor bar and end ring | [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] |

| Stator/rotor windings unbalance | [15,31] |

| Stator/rotor windings short circuit | [14,70,78,79] |

| Static, dynamic or mixed eccentricity | [80,81,82,83] |

| Ball bearing and race | [84,85,86] |

| Magnetization-related | [87] |

3.2. RTDS Hardware Platforms

4. Intelligent FD and CBM of Electrical Machines

- DT parameters can be updated in real time based on voltage, current, vibration, acoustic, field, speed, and temperature measurements.

- DT can be supplied by the measured phase (, and ) or the line (, and ) voltages.

- DT provides a wide range of inaccessible signals that commonly require sophisticated instrumentation.

- More clear fault signatures can be detected in physical variables of the DT.

- Intelligent FD and CBM become possible through processing of DT data outcomes.

- Remote monitoring and control become feasible via the IoT infrastructure.

5. Conclusion

- The DT of an electrical machine is a synchronized, ultra-fidelity replica of it, incorporating multiphysics, multiscale, and probabilistic modeling.

- An automated, bidirectional, real-time flow of data occurs between the DT and the electrical machine through appropriate instrumentation and the IoT platform.

- The twin encompasses data from the service stage of the electrical machine’s lifecycle and remains connected to this phase through to the retirement stage.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Alternating Current |

| COLP | Circuit-Oriented Lumped-Parameter |

| CBM | Condition-Based Monitoring |

| CMPU | Chip MultiProcessor Unit |

| CSPU | Chip Single-core Processor Unit |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DoS | Digital offline Simulation |

| DRTS | Digital Real-Time Simulation |

| DS | Digital Simulation |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| FD | Fault Diagnosis |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Arrays |

| GPU | Graphics Processor Unit |

| H-i-L | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| IM | Induction Machine |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MEC | Magnetic Equivalent Circuit |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MMF | MagnetoMotive Force |

| MPI | Message Passing Interface |

| MWFA | Modified Winding Function Approach |

| ODE | Ordinary Differential Equation |

| PHYB | PHYsics-Based |

| PMSM | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine |

| RFID | Radio Frequency IDentification |

| RTDS | Real-Time Digital Simulator |

| PMSG | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator |

| SCIM | Squirrel Cage Induction Machine |

| SIMD | Single Instruction Multiple Data |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

| TSR | Tip–Speed Ratio |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| P-H-i-L | Power-Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| H-i-L | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| P-i-L | Processor-in-the-Loop |

| S-i-L | Software-in-the-Loop |

| WECS | Wind Energy Conversion System |

| WFA | Winding Function Approach |

References

- Semenkov, K.; Promyslov, V.; Poletykin, A.; Mengazetdinov, N. Validation of Complex Control Systems with Heterogeneous Digital Models in Industry 4.0 Framework. Machines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwirth, T.; Jancke, R.; Sohrmann, C. Dynamic Fault Injection into Digital Twins of Safety-Critical Systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 Design, Automation and Test in Europe Conference and Exhibition (DATE); 2021; pp. 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Wan, X.; Liu, L.; Gao, Z.; Yang, M. Fault Diagnosis of Intelligent Production Line Based on Digital Twin and Improved Random Forest. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, S.H.; Razik, H.; Dunai, L. Electrical Machines: Real-time Simulation for Intelligent Fault Diagnosis, Prognostics and Health Management. In Proceedings of the IECON 2024 - 50th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florkowski, M. Digital Twins and Simulations: World of Simulation. ABB report 2019, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Mojlish, S.; Erdogan, N.; Levine, D.; Davoudi, A. Review of Hardware Platforms for Real-time Simulation of Electric Machines. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2017, 3, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; San, O.; Kvamsdal, T. Digital Twin: Values, Challenges and Enablers From a Modeling Perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21980–22012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Besnerais, J.; Fasquelle, A.; Hecquet, M.; Pelle, J.; Lanfranchi, V.; Harmand, S.; Brochet, P.; Randria, A. Multiphysics Modeling: Electro-Vibro-Acoustics and Heat Transfer of PWM-Fed Induction Machines. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2010, 57, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Besnerais, J. Vibroacoustic Analysis of Radial and Tangential Air-Gap Magnetic Forces in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2015, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar Faruque, M.D.; Strasser, T.; Lauss, G.; Jalili-Marandi, V.; Forsyth, P.; Dufour, C.; Dinavahi, V.; Monti, A.; Kotsampopoulos, P.; Martinez, J.A.; et al. Real-time Simulation Technologies for Power Systems Design, Testing, and Analysis. IEEE Power and Energy Technology Systems Journal 2015, 2, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boglietti, A.; Cavagnino, A.; Lazzari, M.; Pastorelli, M. A Simplified Thermal Model for Variable-speed Self-cooled Industrial Induction Motor. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2003, 39, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, M.; Iravani, R. Massively Parallel Implementation of AC Machine Models for FPGA-Based Real-time Simulation of Electromagnetic Transients. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2011, 26, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jatskevich, J.; Dinavahi, V.; Dommel, H.W.; Martinez, J.A.; Strunz, K.; Rioual, M.; Chang, G.W.; Iravani, R. Methods of Interfacing Rotating Machine Models in Transient Simulation Programs. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2010, 25, 891–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agah, G.R.; Rahideh, A.; Faradonbeh, V.Z.; Kia, S.H. Stator Winding Interturn Short-Circuit Fault Modeling and Detection of Squirrel-Cage Induction Motors. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2024, 10, 5725–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati Kia, S. Detection of Stator and Rotor Asymmetries Faults in Wound Rotor Induction Machines: Modeling, Test and Real-time Implementation. In Emerging Electric Machines; Zobaa, A.F., Aleem, S.H.A., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiegna, H.; Amara, Y.; Barakat, G. Overview of Analytical Models of Permanent Magnet Electrical Machines for Analysis and Design Purposes. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 2013, 90, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillers, E.; Le Besnerais, J.; Lubin, T.; Hecquet, M.; Lecointe, J.P. A Review of Subdomain Modeling Techniques in Electrical Machines: Performances and Applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 XXII International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM); 2016; pp. 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotating Machines. In Real-Time Electromagnetic Transient Simulation of AC–DC Networks; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2021; chapter 4, pp. 143–191. [CrossRef]

- Stadtmann, F.; Rasheed, A.; Kvamsdal, T.; Johannessen, K.A.; San, O.; Kölle, K.; Tande, J.O.; Barstad, I.; Benhamou, A.; Brathaug, T.; et al. Digital Twins in Wind Energy: Emerging Technologies and Industry-Informed Future Directions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 110762–110795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

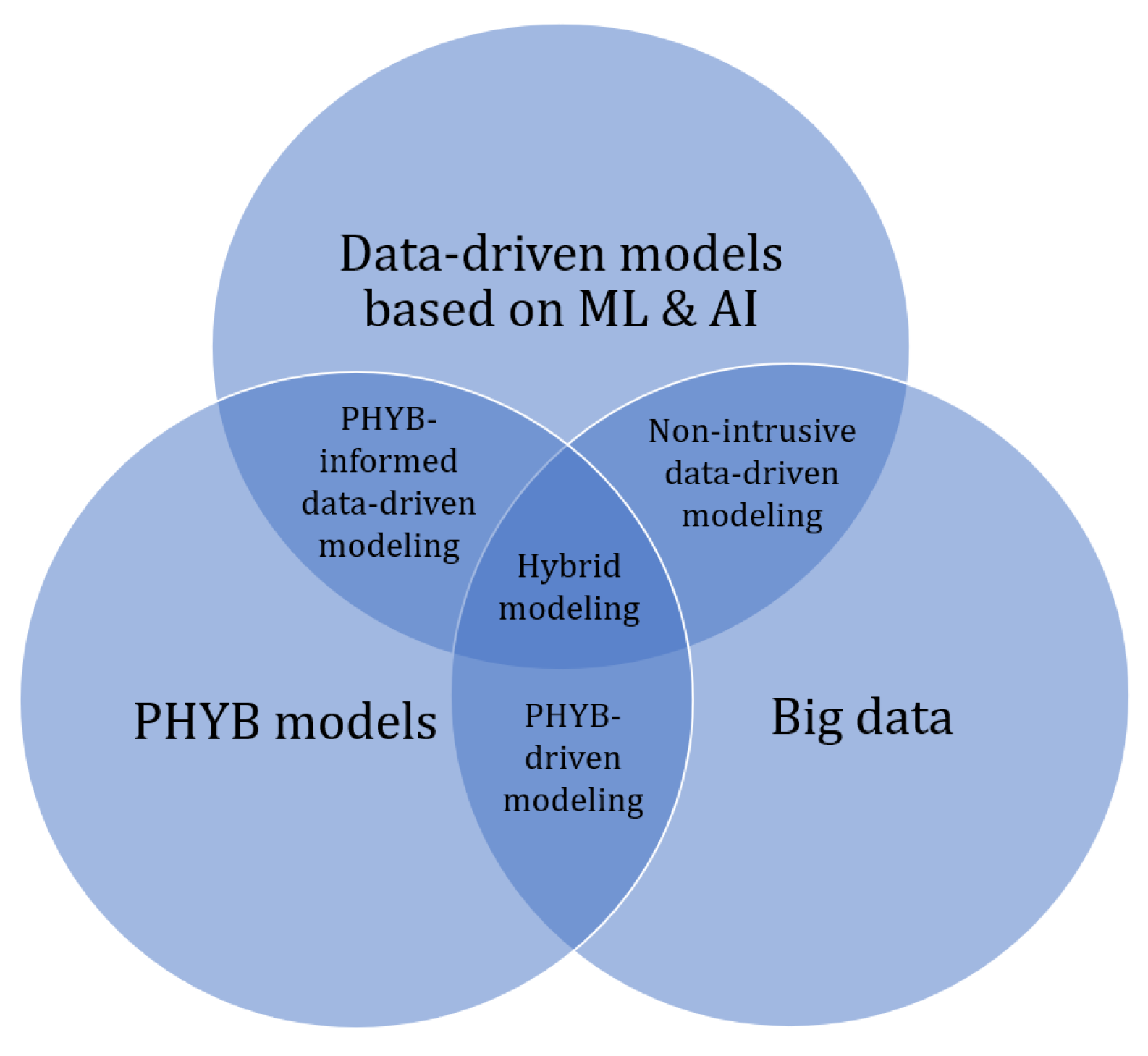

- San, O.; Rasheed, A.; Kvamsdal, T. Hybrid Analysis and Modeling, Eclecticism, and Multifidelity Computing Toward Digital Twin Revolution. GAMM-Mitteilungen 2021, 44, e202100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.; Flore, D.; Schöps, S. Performance Analysis of Electrical Machines Using a Hybrid Data- and Physics-Driven Model. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2023, 38, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terron-Santiago, C.; Martinez-Roman, J.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Sapena-Bano, A. A Review of Techniques Used for Induction Machine Fault Modelling. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Grant, B.; DeFour, R.; Sharma, C.; Bahadoorsingh, S. A Review of Induction Motor Fault Modeling. Electric Power Systems Research 2016, 133, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; He, S.; Huang, J. A Review of Modeling and Diagnostic Techniques for Eccentricity Fault in Electric Machines. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.; Joshi, B.M.; Rajpurohit, B.S. Review of Fault Modeling Methods for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors and Their Comparison. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 11th International Symposium on Diagnostics for Electrical Machines, Power Electronics and Drives (SDEMPED); 2017; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, J.; Venne, P.; Paquin, J.N. The What, Where, and Why of Real-time Simulation. Planet RT 2010, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalič, F.; Truntič, M.; Hren, A. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulations: A Historical Overview of Engineering Challenges. Electronics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horri, N.; Pietraszko, M. A Tutorial and Review on Flight Control Co-Simulation Using Matlab/Simulink and Flight Simulators. Automation 2022, 3, 486–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terron-Santiago, C.; Martinez-Roman, J.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Sapena-Bano, A. Low-Computational-Cost Hybrid FEM-Analytical Induction Machine Model for the Diagnosis of Rotor Eccentricity, Based on Sparse Identification Techniques and Trigonometric Interpolation. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapena-Bano, A.; Chinesta, F.; Pineda-Sanchez, M.; Aguado, J.; Borzacchiello, D.; Puche-Panadero, R. Induction Machine Model with Finite Element Accuracy for Condition Monitoring Running in Real Time Using Hardware in the Loop System. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2019, 111, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, M.; Hedayati Kia, S.; Hoseintabar Marzebali, M.; Arab Khaburi, D.; Razik, H. Power-Hardware-in-the-Loop for Stator Windings Asymmetry Fault Analysis in Direct-Drive PMSG-Based Wind Turbines. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Lei, G.; Yin, W.; Ba, X.; Zhu, J. Construction Method and Application Prospect of Electrical Machine Digital Twin. In Proceedings of the 2022 25th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS); 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.H.; Svennevig, P.R.; Svidt, K.; Han, D.; Nielsen, H.K. A Digital Twin Predictive Maintenance Framework of Air Handling Units Based on Automatic Fault Detection and Diagnostics. Energy and Buildings 2022, 261, 111988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falekas, G.; Karlis, A. Digital Twin in Electrical Machine Control and Predictive Maintenance: State-of-the-Art and Future Prospects. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, T.; Deng, X.; Liu, Z.; Tan, J. Digital Twin: A State-of-the-Art Review of Its Enabling Technologies, Applications and Challenges. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing and Special Equipment 2021, 2, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Choudhury, M.D.; Blincoe, K.; Dhupia, J.S. A Digital Twin Based Framework for Real-Time Machine Condition Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE); 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, B.D. Digital Twins and Living Models at NASA. In Proceedings of the Digital Twin Summit; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2019, 15, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, A.; Fan, Z.; Day, C.; Barlow, C. Digital Twin: Enabling Technologies, Challenges and Open Research. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Fang, S.; Dong, H.; Xu, C. Review of Digital Twin About Concepts, Technologies, and Industrial Applications. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2021, 58, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauer, J.; Schweigert-Recksiek, S.; Engel, C.; Spreitzer, K.; Zimmermann, M. What is a Digital Twin? – Definitions and Insights From an Industrial Case Study in Technical Product Developement. Proceedings of the Design Society: DESIGN Conference 2020, 1, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrabič, R.; Erkoyuncu, J.A.; Butala, P.; Roy, R. Digital Twins: Understanding the Added Value of Integrated Models for Through-life Engineering Services. Procedia Manufacturing 2018, 16, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shen, W.; Wang, X. The Internet of Things in Manufacturing: Key Issues and Potential Applications. IEEE Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Magazine 2018, 4, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Dinavahi, V.; Liang, T. Towards hydrogen-powered electric aircraft: Physics-informed machine learning based multi-domain modeling and real-time digital twin emulation on FPGA. Energy 2025, 322, 135451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Gonzalez, F.; Griffo, A.; Sen, B.; Wang, J. Real-time Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation of Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives Under Stator Faults. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2017, 64, 6960–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Karamanakos, P.; Rodriguez, J. Digital Twin Techniques for Power Electronics-Based Energy Conversion Systems: A Survey of Concepts, Application Scenarios, Future Challenges, and Trends. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 2023, 17, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, G.; Ferreira, A. Extending the Multiphysics Modelling of Electric Machines in a Digital Twin Concept. In Proceedings of the 2021 11th IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications (IDAACS), Vol. 2; 2021; pp. 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranian, M.E.; Mohseni, M.; Aghili, S.; Parizad, A.; Baghaee, H.R.; Guerrero, J.M. Real-time FPGA-Based HIL Emulator of Power Electronics Controllers Using NI PXI for DFIG Studies. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics 2022, 10, 2005–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dinavahi, V. Hardware Emulation Building Blocks for Real-time Simulation of Large-Scale Power Grids. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2014, 10, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, E. Multiphase Electric Machines for Variable-Speed Applications. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2008, 55, 1893–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lipo, T. Modeling and Control of a Multi-phase Induction Machine with Structural Unbalance. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 1996, 11, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toliyat, H.; Lipo, T. Transient Analysis of Cage Induction Machines Under Stator, Rotor Bar and End Ring faults. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 1995, 10, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzid, S.; Viarouge, P.; Cros, J. Real-Time Digital Twin of a Wound Rotor Induction Machine Based on Finite Element Method. Energies 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrožič, V.; Fišer, R.; Nemec, M.; Drobnič, K. Dynamic Model of Induction Machine with Faulty Rotor in Field Reference Frame. In Proceedings of the 2013 9th IEEE International Symposium on Diagnostics for Electric Machines, Power Electronics and Drives (SDEMPED); 2013; pp. 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccarini, L.M.R.; de Menezes, B.R.; Caminhas, W.M. Fault Induction Dynamic Model, Suitable for Computer Simulation: Simulation Results and Experimental Validation. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2010, 24, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachir, S.; Tnani, S.; Trigeassou, J.C.; Champenois, G. Diagnosis by Parameter Estimation of Stator and Rotor Faults Occurring in Induction Machines. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2006, 53, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, G.; De Angelo, C.; Garcia, G.; Solsona, J.; Valla, M. Effects of Rotor Bar and End-Ring Faults Over the Signals of a Position Estimation Strategy for Induction Motors. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2005, 41, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, M.; Drobnič, K.; Fišer, R.; Ambrožič, V. Simplified model of induction machine with broken rotor bars. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (PEMC); 2016; pp. 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magagula, G.S.; Nnachi, A.F.; Akumu, A.O. Broken Rotor Bar Fault Simulation And Analysis In D-q Reference Frame. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica; 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannati, M.; Idris, N.; Salam, Z. A new method for modeling and vector control of unbalanced induction motors. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE); 2012; pp. 3625–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallam, R.; Habetler, T.; Harley, R. Transient Model for Induction Machines with Stator Winding Turn Faults. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2002, 38, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassa, N.; Rachek, M. Modeling and detecting the stator winding inter turn fault of permanent magnet synchronous motors using stator current signature analysis. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 2020, 167, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Meena, D.C.; Patra, A.K. Asynchronous Motor Modeling in Simulink for Stator and Rotor Fault Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Green and Human Information Technology (ICGHIT); 2019; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guezmil, A.; Berriri, H.; Pusca, R.; Sakly, A.; Romary, R.; Mimouni, M. Detecting Inter-Turn Short-Circuit Fault in Induction Machine Using High-Order Sliding Mode Observer: Simulation and Experimental Verification. Journal of Control, Automation and Electrical Systems 2017, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Thomas, V.V. , 2018; pp. 511–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4394-9_50.Analysis. In Advances in Power Systems and Energy Management: ETAEERE-2016; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, B.; Kanemaru, M.; Lin, C.; Liu, D.; Miyoshi, M.; Teo, K.H.; Habetler, T.G. Model-Based Analysis and Quantification of Bearing Faults in Induction Machines. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2020, 56, 2158–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Seki, Y.; Kurita, N. Analysis for Fault Detection of Vector-Controlled Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor With Permanent Magnet Defect. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2013, 49, 2331–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshandel Tavana, N.; Dinavahi, V. A General Framework for FPGA-Based Real-time Emulation of Electrical Machines for HIL Applications. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2015, 62, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, G.; Razik, H.; Rezzoug, A. An Induction Motor Model Including the First Space Harmonics for Broken Rotor Bar Diagnosis. European Transactions on Electrical Power 2005, 15, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chen, J.; Dong, K.; Yang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Z. Modeling and Evaluation of Stator and Rotor Faults for Induction Motors. Energies 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouzou, S.E.; Ghoggal, A.; Aboubou, A.; Sahraoui, M.; Razik, H. Modeling of Induction Machines with Skewed Rotor Slots Dedicated to Rotor Faults. In Proceedings of the 2005 5th IEEE International Symposium on Diagnostics for Electric Machines, Power Electronics and Drives; 2005; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaikaa, M.Y.; Hadjami, M.; Khezzar, A. Effects of the Simultaneous Presence of Static Eccentricity and Broken Rotor Bars on the Stator Current of Induction Machine. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2014, 61, 2452–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Kwon, B.H. Corrosion Model of a Rotor-Bar-Under-Fault Progress in Induction Motors. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2006, 53, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossio, G.R.; De Angelo, C.H.; Pezzani, C.M.; Bossio, J.M.; Garcia, G.O. Evaluation of Harmonic Current Sidebands for Broken Bar Diagnosis in Induction Motors. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Diagnostics for Electric Machines, Power Electronics and Drives; 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdouin, G.; Barakat, G.; Dakyo, B.; Destobbeleer, E. A winding Function Theory Based Global Method for the Simulation of Faulty Induction Machines. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, 2003. IEMDC’03, 2003; Vol. 1, pp. 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojaghi, M.; Sabouri, M.; Faiz, J. Performance Analysis of Squirrel-Cage Induction Motors Under Broken Rotor Bar and Stator Inter-Turn Fault Conditions Using Analytical Modeling. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2018, 54, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benninger, M.; Liebschner, M.; Kreischer, C. Automated Parameter Identification for Multiple Coupled Circuit Modeling of Induction Machines. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM); 2022; pp. 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanneaux, V.; Dagues, B.; Faucher, J.; Barakat, G. An Accurate Model of Squirrel Cage Induction Machines Under Stator Faults. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 2003, 63, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi, B.; Takorabet, N.; Meibody-Tabar, F. Analytical Circuit-Based Model of PMSM Under Stator Inter-Turn Short-Circuit Fault Validated by Time-Stepping Finite Element Analysis. In Proceedings of the XIX International Conference on Electrical Machines - ICEM, 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilamparithi, T.; Nandi, S. Comparison of Results for Eccentric Cage Induction Motor Using Finite Element Method and Modified Winding Function Approach. In Proceedings of the 2010 Joint International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems & 2010 Power India, 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Ojaghi, M. Unified Winding Function Approach for Dynamic Simulation of Different Kinds of Eccentricity Faults in Cage Induction Machines. IET Electric Power Applications 2009, 3, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joksimovic, G.; Durovic, M.; Penman, J.; Arthur, N. Dynamic Simulation of Dynamic Eccentricity in Induction Machines-Winding Function Approach. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2000, 15, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.S.C.; Mohanty, A.R. A Simplified Dynamical Model of Mixed Eccentricity Fault in a Three-Phase Induction Motor. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 68, 4341–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, M.; Yang, B.; Song, K. A Model-Based Method for Bearing Fault Detection Using Motor Current. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2020, 1650, 032130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojaghi, M.; Yazdandoost, N. Winding Function Approach to Simulate Induction Motors Under Sleeve Bearing Fault. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT); 2014; pp. 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojaghi, M.; Sabouri, M.; Faiz, J. Analytic Model for Induction Motors Under Localized Bearing Faults. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2018, 33, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajily, E.; Ardebili, M.; Abbaszadeh, K. Magnet Defect and Rotor Eccentricity Modeling in Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Machines via 3-D Field Reconstruction Method. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2016, 31, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strangas, E.; Clerc, G.; Razik, H.; Soualhi, A. Fault Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Reliability for Electrical Machines and Drives; IEEE Press Series, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2021.

- Pereira, L.A.; Scharlau, C.C.; Pereira, L.F.A.; Haffner, J.F. General Model of a Five-Phase Induction Machine Allowing for Harmonics in the Air Gap Field. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2006, 21, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapena-Bano, A.; Martinez-Roman, J.; Puche-Panadero, R.; Pineda-Sanchez, M.; Perez-Cruz, J.; Riera-Guasp, M. Induction Machine Model with Space Harmonics for Fault Diagnosis Based on the Convolution Theorem. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2018, 100, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Wang, J.; Mills, A.R.; Chong, E.; Sun, Z. Current-Residual-Based Stator Interturn Fault Detection in Permanent Magnet Machines. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2021, 68, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Moon, S.; Kim, S.W. An Early Stage Interturn Fault Diagnosis of PMSMs by Using Negative-Sequence Components. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2017, 64, 5701–5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, N.R.; Dinavahi, V. Real-time Nonlinear Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Model of Induction Machine on FPGA for Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2016, 31, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, B.; Dinavahi, V. Experimental Validation of a Geometrical Nonlinear Permeance Network Based Real-time Induction Machine Model. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2012, 59, 4049–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, N.R.; Dinavahi, V. Real-time FPGA-Based Analytical Space Harmonic Model of Permanent Magnet Machines for Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2015, 51, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizov, G.Y.; Yeh, C.C.; Demerdash, N.A.O. Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Modeling of Induction Machines Under Stator and Rotor Fault Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference; 2009; pp. 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, P. Modified Magnetic-Equivalent-Circuit Approach for Various Faults Studying in Saturable Double-Cage-Induction Machines. IET Electric Power Applications 2017, 11, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemeida, A.; Billah, M.M.; Kudelina, K.; Asad, B.; Naseer, M.U.; Guo, B.; Martin, F.; Rasilo, P.; Belahcen, A. Magnetic Equivalent Circuit and Lagrange Interpolation Function Modeling of Induction Machines Under Broken Bar Faults. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2024, 60, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, P.; Shiri, A. Rotor/Stator Inter-Turn Short Circuit Fault Detection for Saturable Wound-Rotor Induction Machine by Modified Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Approach. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2017, 53, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Moosavi, S.M.; Abadi, M.B.; Cruz, S.M. Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Modelling of Doubly-Fed Induction Generator with Assessment of Rotor Inter-Turn Short-Circuit Fault Indices. IET Renewable Power Generation 2016, 10, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanfekr, R.; Jalilian, A. An Approach to Discriminate Between Types of Rotor and Stator Winding Faults in Wound Rotor Induction Machines. In Proceedings of the Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Iranian Conference on; 2018; pp. 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Ghasemi-Bijan, M.; Ebrahimi, B.M. Modeling and Diagnosing Eccentricity Fault Using Three-dimensional Magnetic Equivalent Circuit Model of Three-phase Squirrel-cage Induction Motor. Electric Power Components and Systems 2015, 43, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Ding, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, T.; Chu, F. Stator Current Model for Detecting Rolling Bearing Faults in Induction Motors Using Magnetic Equivalent Circuits. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2019, 131, 554–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Desenfans, P.; Pissoort, D.; Hallez, H.; Vanoost, D. Multiphysics Coupling Model to Characterise the Behaviour of Induction Motors With Eccentricity and Bearing Faults. IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion 2024, 39, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Mazaheri-Tehrani, E. Demagnetization Modeling and Fault Diagnosing Techniques in Permanent Magnet Machines Under Stationary and Nonstationary Conditions: An Overview. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2017, 53, 2772–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raminosoa, T.; Farooq, J.; Djerdir, A.; Miraoui, A. Reluctance Network Modelling of Surface Permanent Magnet Motor Considering Iron Nonlinearities. Energy Conversion and Management 2009, 50, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, K.; Saied, S.; Hemmati, S.; Tenconi, A. Inverse Transform Method for Magnet Defect Diagnosis in Permanent Magnet Machines. IET Electric Power Applications 2014, 8, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, J.; Srairi, S.; Djerdir, A.; Miraoui, A. Use of Permeance Network Mmethod in the Demagnetization Phenomenon Modeling in a Permanent Magnet Motor. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2006, 42, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, D.; Yoshida, Y.; Tajima, K. Demagnetization Analysis of Ferrite Magnet Motor Based on Reluctance Network Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2016 19th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS); 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Xia, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Shi, T. Improved Equivalent Magnetic Network Modeling for Analyzing Working Points of PMs in Interior Permanent Magnet Machine. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 2018, 454, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmouditabar, F.; Vahedi, A.; Ojaghlu, P.; Takorabet, N. Irreversible Demagnetization Analysis of RWAFPM Motor Using Modified MEC Algorithm. COMPEL: The International Journal for Computation and Mathematics in Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2020, 39, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paja, C.A.R.; Romero, A.; Giral, R. Evaluation of Fixed-Step Differential Equations Solution Methods for Fuel Cell Real-Time Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2007 International Conference on Clean Electrical Power; 2007; pp. 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, L.A.; Blanchette, H.F.; Bélanger, J.; Al-Haddad, K. Real-Time Simulation-Based Multisolver Decoupling Technique for Complex Power-Electronics Circuits. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2016, 31, 2313–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouscayrol, A. Different Types of Hardware-In-the-Loop simulation for Electric Drives. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics; 2008; pp. 2146–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, L.F.; Dinavahi, V. Real-Time Simulation of a Wind Energy System Based on the Doubly-Fed Induction Generator. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2009, 24, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne, R.; Dessaint, L.A.; Fortin-Blanchette, H.; Sybille, G. Analysis and Validation of a Real-Time AC Drive Simulator. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2004, 19, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C. A Real-Time Simulator for Doubly Fed Induction Generator based Wind Turbine Applications. Technical report, 2004.

- Abourida, S.; Dufour, C.; Belanger, J.; Yamada, T.; Arasawa, T. Hardware-In-the-Loop Simulation of Finite-Element Based Motor Drives with RT-LAB and JMAG. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, 2006; Vol. 3, pp. 2462–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C.; Abourida, S.; Belanger, J. Hardware-In-the-Loop Simulation of Power Drives with RT-LAB. In Proceedings of the 2005 International Conference on Power Electronics and Drives Systems, 2005; Vol. 2, pp. 1646–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C.; Cense, S.; Jalili-Marandi, V.; Bélanger, J. Review of State-of-the-Art Solver Solutions for HIL Simulation of Power Systems, Power Electronic and Motor Drives. In Proceedings of the 2013 15th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE); 2013; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C.; Belanger, J. A Real-Time Simulator for Doubly Fed Induction Generator Based Wind Turbine Applications. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE 35th Annual Power Electronics Specialists Conference (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37551), 2004; Vol. 5, pp. 3597–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquin, J.N.; Li, W.; Belanger, J.; Schoen, L.; Peres, I.; Olariu, C.; Kohmann, H. A Modern and Open Real-Time Digital Simulator of All-Electric Ships with a Multi-Platform Co-Simulation Approach. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Electric Ship Technologies Symposium; 2009; pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, M.O.; Dinavahi, V. An Advanced PC-Cluster Based Real-Time Simulator for Power Electronics and Drives. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, 2006; Vol. 3, pp. 2579–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, L.F.; Faruque, M.O.; Nie, X.; Dinavahi, V. A Versatile Cluster-Based Real-Time Digital Simulator for Power Engineering Research. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2006, 21, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larose, C.; Guerette, S.; Guay, F.; Nolet, A.; Yamamoto, T.; Enomoto, H.; Kono, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Taoka, H. A fully digital real-time power system simulator based on PC-cluster. In Proceedings of the Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 11 2003; Vol. 63, pp. 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, S.; Aliprantis, D.C.; Zambreno, J. Dynamic Simulation of Electric Machines on FPGA Boards. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference; 2009; pp. 1523–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce, P.; Ibarra, L.; Molina, A.; MacCleery, B. Real Time Simulation for DC and AC Motors Based on Lab VIEW FPGAs. In Proceedings of the IFAC Proceedings Volumes (IFAC-PapersOnline). IFAC Secretariat, 2012; Vol. 14, pp. 1777–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandaghi, B.; Dinavahi, V. Hardware-in-the-Loop Emulation of Linear Induction Motor Drive for MagLev Application. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2016, 44, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Richter, J.; Jurkewitz, U.; Braun, M. FPGA-based Real-Time Simulation of Nonlinear Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines for Power Hardware-in-the-Loop Emulation Systems. In Proceedings of the IECON 2014 - 40th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society; 2014; pp. 3763–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, C.; Belanger, J.; Abourida, S.; Lapointe, V. FPGA-Based Real-Time Simulation of Finite-Element Analysis Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine Drives. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference; 2007; pp. 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parma, G.G.; Dinavahi, V. Real-Time Digital Hardware Simulation of Power Electronics and Drives. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2007, 22, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredo, K.; Zenor, J.; Bednar, R.; Crosbie, R. FPGA-Accelerated Simulink Simulations of Electrical Machines. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Electric Ship Technologies Symposium (ESTS); 2015; pp. 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajne, P.A.; Ramanarayanan, V. Programming an FPGA to Emulate the Dynamics of DC Machines. In Proceedings of the 2006 India International Conference on Power Electronics; 2006; pp. 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, L.; Li, C.; Yao, X.; Wang, J. FPGA-Based Detailed Real-Time Simulation of Power Converters and Electric Machines for EV HIL Applications. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2015, 51, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, T.C.; Krein, P.T.; Yilmaz, M.; Friedl, A. On the Feasibility of Using Large-Scale Numerical Electric Machine Field Analysis Software in Complex Electric Drive System Design Tools. In Proceedings of the 2008 11th Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics; 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzima, A.J.; Krein, P.T.; O’Connell, T.C. Investigation of Accelerating Numerical-Field Analysis Methods for Electric Machines with the Incorporation of Graphic-Processor Based Parallel Processing Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Electric Ship Technologies Symposium; 2009; pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.W.O.; Guyomarc’h, F.; Dekeyser, J.L.; Le Menach, Y. Automatic Multi-GPU Code Generation Applied to Simulation of Electrical Machines. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2012, 48, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.W.D.O.; Chevallier, L.; Menach, Y.L.; Guyomarch, F. Test harness on a preconditioned conjugate gradient solver on GPUs: An efficiency analysis. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2013, 49, 1729–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Li, X.H.; Wu, L.H.; Zhou, S.W.; Liu, K. GPU-Accelerated Parallel Coevolutionary Algorithm for Parameters Identification and Temperature Monitoring in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2015, 11, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracikowski, N.; Hecquet, M.; Brochet, P.; Shirinskii, S.V. Multiphysics Modeling of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine by Using Lumped Models. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2012, 59, 2426–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasquelle, A. Coupled Electromagnetic, Acoustic and Thermal-Flow Modelling of an Induction Motor of Railway Traction. Theses, Ecole Centrale de Lille, 2007.

- Tao, F.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Nee, A. Digital Twin Driven Prognostics and Health Management for Complex Equipment. CIRP Annals 2018, 67, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagaris, I.; Likas, A.; Fotiadis, D. Artificial Neural Networks for Solving Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 1998, 9, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Chamoin, L.; Lisser, A. Solving Large-scale Variational Inequalities with Dynamically Adjusting Initial Condition in Physics-informed Neural Networks. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2024, 429, 117156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Shao, H.; Williams, D.; Lu, S.; Shu, L.; de Silva, C.W. Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Machinery Using Digital Twin-Assisted Deep Transfer Learning. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2021, 215, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Things | Representation | Data | Purposes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gartner | Process, physical object, organization, person, or any abstraction | Encapsulated software | Information from several DT can be collected to provide a unified perspective of real-world objects | Simulating an entity in real time |

| NVIDA | Real-world physical things, people, system | Virtual | Information collected from connected sensors, processed through edge computing, enables the replication of physical equipment behavior | Enables the autonomy of systems through the machine learning |

| IBM | Object, system | Virtual | Two-way flow of information | Decision-making based on simulation, machine learning, and reasoning |

| DNV | Asset, system | Virtual | Provide system information through a unified modeling and data solution | Offer guidance for decision-making throughout the asset lifecycle |

| GE Digital | Physical asset, system, process | Software | Real-time analytics | Enhance business outcomes through proactive detection, prevention, prediction, and optimization |

| Siemens | Physical product, process | Virtual | Data is used throughout the product lifecycle to simulate, predict and optimize the product before any prototyping | Undrestand and predict the physical counterpart’s performance characteristics |

| Oracle | Physical asset, device | Digital | Updated with operational data and can be combined with physics-based models | Virtual sensor, detect anomalous behavior and prevent anomalies |

| Microsoft | Object | Digital exact replica | Data from monitoring devices for real-time view of asset | Improve the real-life version |

| Digital twin consortium | Real-world entities and processes | Virtual that is synchronized at a specified frequency and fidelity | Use real-time and historical data to represent the past and present | Transform business, simulate predicted futures |

| Trauer et al. | Physical system | Virtual dynamic | Bidirectional information exchange, and the connection along the entire lifecycle | Improvement of product development by refining requirements, easing troubleshooting, or supporting after sales |

| Grieves, Vickers | Physical manufactured product | Virtual equivalent from the micro atomic level to the macro geometrical level | Link between physical system and its replica | Understanding system behavior |

| Industrial digital twin association | Asset | Digital | Updating throughout the lifecycle based on real-time data | Emulation, simulation, integration, testing, monitoring, and maintenance |

| PHYB/COLP | Data-driven |

|---|---|

| + Solid foundation in physics | – Black-box concept |

| – Need partial or entire geometric data of the electrical machine | + No need for any knowledge about the electrical machine |

| + No need data for training | – A lot of data needs to be provided for machine learning |

| – Need optimization algorithms for continuous updates of model parameters | + Neural network update |

| – Numerical instability of the model | + Stable for a trained model |

| + Less prone to bias | – Bias in the data can be reflected in the model |

| – Difficult to assimilate extensive historical data | + Integrate easily the extensive historical data |

| + Developed model can be used for similar electrical machines | – New model needs to be trained for each electrical machine |

| + Several variables are available from the developed model | – Only the trained variables are available |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).