1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Research Motivation

Being the educators of the twenty-first century, we understand that learning has become a highly personalized process, driven not only by technological inventions but also by the increased demands of students that are inherent in the digital ecosystems. Modern learners no longer consume pre-determined curricula in a linear fashion: they have become fluid and non-linear in their paths through material, platforms and teachers. Given this dynamism, traditional delivery models are finding it harder and harder to keep up with, which is escalating the demand to have adaptive learner-centered approaches, particularly in higher education, where the diversity in background, time-scale, and cognitive and affective style is making homogenized delivery more and more problematic [

1].

At the same time, artificial intelligence (which used to be the topic of laboratory experiments and discussion only) has penetrated through to the mainstream education. The use of adaptive learning systems symbolizes a critical shift: the algorithms have the capability to track learning patterns, identify learning gaps, and reformulate content in real-time [

2]. However, most of the existing applications are either disparate or limited in the scope thus not having a coherent pedagogical rationale. Without such coherent framework, AI tools will be an isolated intervention instead of a transformative change.

As a result, the current paper touches upon the urgent task of theorizing the potential role of AI in scaffolding adaptive learning in higher education in a meaningful way. Instead of another tool or algorithm, it is a structured model, named AIEAM, which is based on both theoretical grounds and emerging practices. This is not meant to replace the teacher or to view learning in reductive terms, but to design a system that will be able to dynamically match the computational power of AI with the complex cognitive and emotional demands of university-level learners [

3].

1.2. Challenges in Personalized Higher Education

Though many institutions of higher learning may boast of enabling personalized learning, the truth is that its real, large-scale adaptation is yet to be achieved. The discourse is often focused on flexibility and learner-centeredness, whereas most of the institutional practices are still based on inflexible schedules, fixed content progressions, and limited feedback cycles [

4]. Even the most good-intentioned faculty who attempt to make instruction individualized on a case-by-case basis often find the scale and heterogeneity of student populations to be a frustration to such attempts, making them spotty or unsustainable. Finally, the hostility between established organizational forms and the natural variability of the learners continues a gap between a pedagogic ideal and practice.

Scalability turns out to be a key impediment. In order to design truly individualized learning pathways of hundreds of learners simultaneously, instructors have to not only disaggregate the content but also collect real-time data, analyze it, and make real-time interventions, which are beyond the cognitive and time limitations of a human instructor working independently. The complication is increased by the use of traditional learning management systems (LMSs) that are developed to store fixed course containers instead of tracking micro-behavioral patterns, integrating learning analytics, and suggesting content in a contextually rich manner [

5].

There is another level brought by equity. When there are no adaptive mechanisms, learners, who have disadvantages in entering the classroom, like poor digital literacy, non-English speaking, or uneven academic preparation, are more vulnerable to a lack of engagement. The homogenizing instructional model which prefers learners to keep with its rhythm unintentionally alienates others. Simultaneously, faculty are facing increasingly high demands to integrate emergent technologies with little preparation, institutional assistance or release time.

The lack of integrated AI-enhanced adaptive systems in higher education thus represents more than a technological gap; it sheds light on structural, pedagogical, and logistical bottlenecks. This gap requires an all-encompassing framework that will integrate educational theory, adaptive technologies, and scalable design [

6].

1.3. Research Objectives and Contributions

In current literature, we define and propose AIEAM-AI-Enhanced Adaptive Learning Framework, which is to be used to support personalized education in the higher education contexts. Our core objective is to develop and implement a theoretically grounded, functionally modular framework that integrates artificial intelligence technologies with pedagogical mandates of adaptivity, learner autonomy and equal access [

7]. Instead of publishing a disjointed technology prototype, we create an integrated system architecture where all elements are intertwined with the learner profiling, real-time feedback, adaptive content delivery, and ethical AI governance.

The framework is developed as a result of two-fold focus on theoretical rigor and practical validation. The model combines theoretical frameworks of learning, including constructivism, cognitive load theory, and self-regulated learning, and the computational affordances of modern AI systems. To make the framework more applicable, it is not introduced in an abstract way but rather is questioned with the help of two major real-life examples, Squirrel AI and Carnegie Learning (MATHia) [

8]. The given illustrative cases provide empirical basis to assess the viability, scalability and flexibility of the suggested model.

In turn, the contributions of the paper develop in three correlated directions. To begin with, we add a cohesive theoretical framework which links AI capabilities with the needs of personalized learning in higher education. Second, we describe the modular framework that could be used in the future to design adaptive learning systems. Third, we make the conceptual model grounded by aligning it with the existing successful applications, thus providing a systematic way of educators, designers, policymakers, etc., to rethink how adaptive AI may be implemented in complex educational settings [

9].

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI and Adaptive Learning in Higher Education

Artificial intelligence is becoming an important force in the wider context of educational technology, and adaptive learning qualifies as one of the most exciting forms of artificial intelligence. In higher education, it is sold as an answer to an old problem of providing instruction that takes into account individual variations in prior knowledge, rate of learning, engagement style, and cognitive ability. In contrast to the traditional instructional models, where a homogeneous learner profile is implicitly assumed, adaptive systems strive to dynamically individualise the learning experience on the basis of real-time feedback and learner inferred requirements [

10].

The core of adaptive learning is the ability to analyze patterns, that is, how a student moves through the material, how he or she reacts to the tests and how he or she responds to feedback. Machine-learning algorithms, natural-language processing, and reinforcement learning are some of the AI technologies that are becoming used to identify such patterns and adapt the learning environment to them [

11]. Practically, it can include suggestions of content with the right level of difficulty, creating individual quizzes, changing the order of instructions, or even changing the speed of the content presentation.

Adaptive systems have been introduced in higher education institutions into courses with high enrollments and low variability, such as introductory mathematics or writing, where variability among students is especially high. Intelligent systems such as ALEKS, Knewton, and MATHia provide AI-based adaptivity that aims at maximizing student performance by providing personalized learning experiences. Such systems show that personalization at scale is technically achievable, but their pedagogical consistency and transparency are under continuing examination [

12].

Still, most adaptive learning projects in universities are small-scale and departmentalized or platform-bound. They are not well integrated into more comprehensive curricular design and institutional policy. This has led to such fragmentation that requires the development of comprehensive frameworks that not only take advantage of the technical possibilities of AI but that are also consistent with the educational missions, values, and limitations of institutions that are higher-education institutions [

13].

2.2. Theoretical Foundations of Personalized Learning

Academically, individualized learning is rooted in a consistent set of educational theory that prioritises learner-specific attributes, active learning and contextual responsiveness. One especially striking instance is constructivist learning theory, according to which the knowledge is created by the learners as a result of their interaction with the environment and not as a result of a passive intake of information. These concepts are reflected in learner-based pedagogical systems where learners dictate their own course through the material in a manner that respects their cognitive preparedness, previous experience and changing intent [

14].

The second important contribution is the self-regulated learning (SRL) theory that enhances our knowledge of personalization through the specification of the central role of metacognition, motivation, and self-monitoring. Here, effective learning is not just in the content that is learned but also in the ability of the learner to plan, monitor and evaluate the learning process [

15]. To this end, features that enable systems to operationalize SRL principles such as goal-setting prompts, reflective feedback, and adaptive pacing are regularly integrated into personalized systems in order to scaffold these metacognitive operations.

Cognitive load theory (CLT) is a complement to these views and demands that instructional design take account of working memory limitations. In line with this, personalized learning environments based on CLT will work to reduce extraneous cognitive load by adjusting the complexity of tasks and the order of those tasks in accordance with the current level of proficiency in the learner. Adaptive learning systems incorporating the principles of CLT also appreciate clarity, strategic pacing, and incremental challenge in order to maintain interest without overwhelming the student [

16].

Taken together, these theoretical frameworks are more than rhetoric; they condense the principles of practical design to intelligent, responsive, and ethically sound adaptive learning systems. They further highlight the fact that personalization is an ongoing dynamic process that needs alignment of learner needs, technological capabilities and pedagogical strategies. As an example, the AIEAM architectural framework is specifically designed on these theoretical scaffolds in all elements.

2.3. Limitations of Existing Frameworks and Research Gap

Despite the significant rate of development of adaptive learning technologies, existing frameworks still fail to perform well when they are subjected to the complex structure of higher education. The majority of models descend to generic blueprints, or are specific to discrete platforms or disciplines. Their engineering is more inclined to optimize the presentation of the content with little regard to the more fundamental pedagogical issues self-regulated learning, ethical stewardship, and interaction dynamics between human users and the AI systems in general. As a result, the frameworks operate more as technical infrastructures than systems of coherent education [

17].

One of the key obstacles is the weak connection between the learning theory and AI design. The construct of constructivism, cognitive load, and other such constructs are often cited, but adaptive systems have seldom applied the constructs to systematic and modular design principles [

18]. In the absence of such translations, AI decisions are less interpretable, and pedagogical alignment is difficult to achieve, thus, it is difficult to interpret or intervene effectively as an instructor. Furthermore, the majority of frameworks do not consider feedback loops that include the motivation of learners, their confidence, and emotional involvement, which were proved to be critical to maintain meaningful learning outcomes.

The parallel issue is scalability. Most implementations today tend to be limited to controlled environments or individual courses, and have little cross-institutional or cross-disciplinary use. Such limitations inhibit the creation of frameworks that can address different institutional objectives, student characteristics, and curriculum designs. Ethical issues, including data privacy, algorithmic bias, and learner autonomy, are also dealt with in a reactive, at least negligent, rather than as inherent parts of design [

19].

The current paper aims at filling this gap by introducing AIEAM, a framework that is aimed at combining the theoretical strength, architectural transparency and empirical flexibility. In a unique way, AIEAM is designed as a scalable, modular and pedagogically transparent system thus meeting the complex requirements of personalized learning in higher education.

3. Theoretical Analysis of Adaptive Learning Models

3.1. Key Features and Classifications of Adaptive Learning Models

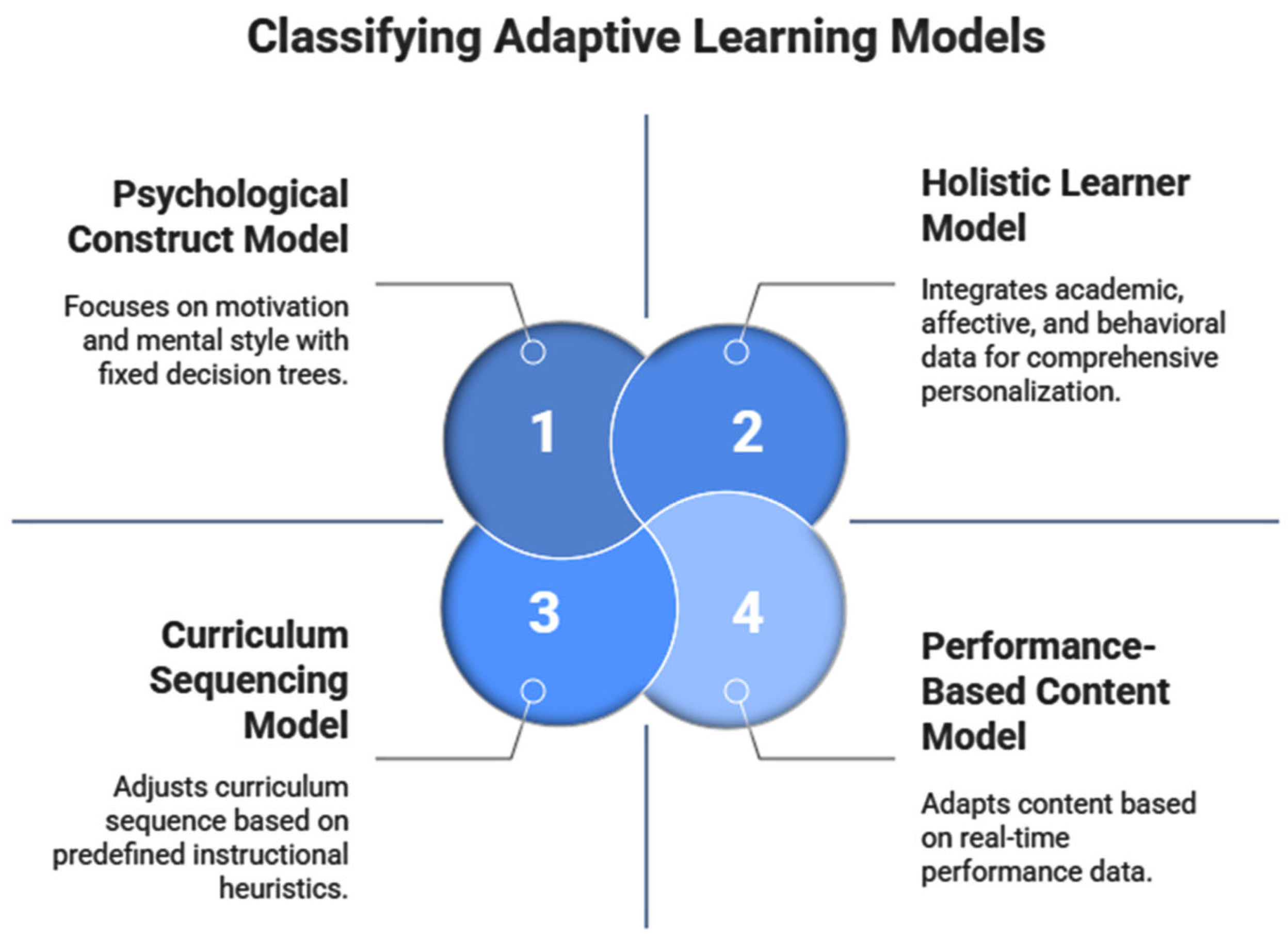

Regarding adaptive learning, it is obvious at once that there is a wide range of models embraced by practitioners, but they all have a similar purpose to adapt the content and the form of delivery to the characteristics of learners and behavioral patterns. At the core of any such models is a feedback-based loop whereby learner data, in terms of quiz scores and time allocated to various tasks, as well as patterns of engagement, are gathered and utilized in real-time to adjust the learning environment accordingly [

20]. Such recalibration may occur in various dimensions including the selection of the curriculum, sequencing, speed control and the kind and frequency of feedback.

Several typologies have been proposed in an effort to explain this terrain. A popular diagram pits rule-based with data-driven systems. Rule-based implementation relies on fixed decision trees or instructional heuristics, and offers transparency and interpretability at the expense of little plasticity and scalability. Instead, data-driven systems use machine-learning algorithms that have the ability to learn patterns and predict the needs of learners; this property enables high levels of personalization but may undermine interpretability and efficiency [

21].

The second axis of differentiation is the scope of adaptivity. There are models that concentrate solely on the content change as a reaction to performance variables; there are models that expand their scope to psychological constructs like motivation, confidence, or mental style. The most ambitious models aim at achieving multi-dimensional adaptivity, combining academic, affective, and behavioral streams of data into a holistic learner model.

When creating the new framework called AIEAM, we have aimed to use the advantages of each category and overcome its drawbacks by means of modular, transparent and pedagogically consistent architecture.

Figure 1 presents a classification of adaptive learning models, highlighting four distinct approaches—psychological, holistic, sequencing-based, and performance-based—that inform the design of personalized learning systems in higher education.

3.2. Limitations in Current AI-Enhanced Systems

In the realm of modern education, the use of AI-enhanced systems has, in fact, brought new levels of automation and personalization, but on a regular basis, they continually fall short of the key barriers to their pedagogical effectiveness and sustainability. The first of these constraints is the opaque nature of the decision-making process: numerous AI-based systems represent a black box, and there is little information about which decision paths are taken or how recommendations are justified [

22]. This kind of opacity hinders the abilities of the educators to intervene, interpret or trust the judgments of the system especially when the outcomes are not in line with the expectations.

The second issue, which is related to the first one, is the limited range of personalization. The majority of existing systems focus intensively on cognitive measures: quiz scores, time on task and do not pay much attention to non-cognitive ones like motivation, self-efficacy or emotional involvement. As a result, adaptivity becomes synonymous with performance monitoring as opposed to comprehensive assistance that is responsive to the complexity of learner differences. Such a reductionist disposition fails to consider the complications of higher education.

Scalability is also another structural challenge. Most applications of AI models are highly context specific in their content areas or institutional structures even though technically they can be applied to other contexts [

23]. They are not modular, limiting reuse, customization and integration with existing learning ecosystems. What makes this situation worse is that ethical aspects like data privacy, algorithmic bias, informed consent are hardly integrated into the systemic design, but instead, they are considered extraneous issues.

Combined, these shortcomings demonstrate the necessity of a radical shift in thinking: a new conceptual framework that incorporates transparency, pedagogical alignment, modular design, and ethical awareness into the conceptual underpinnings of adaptive learning.

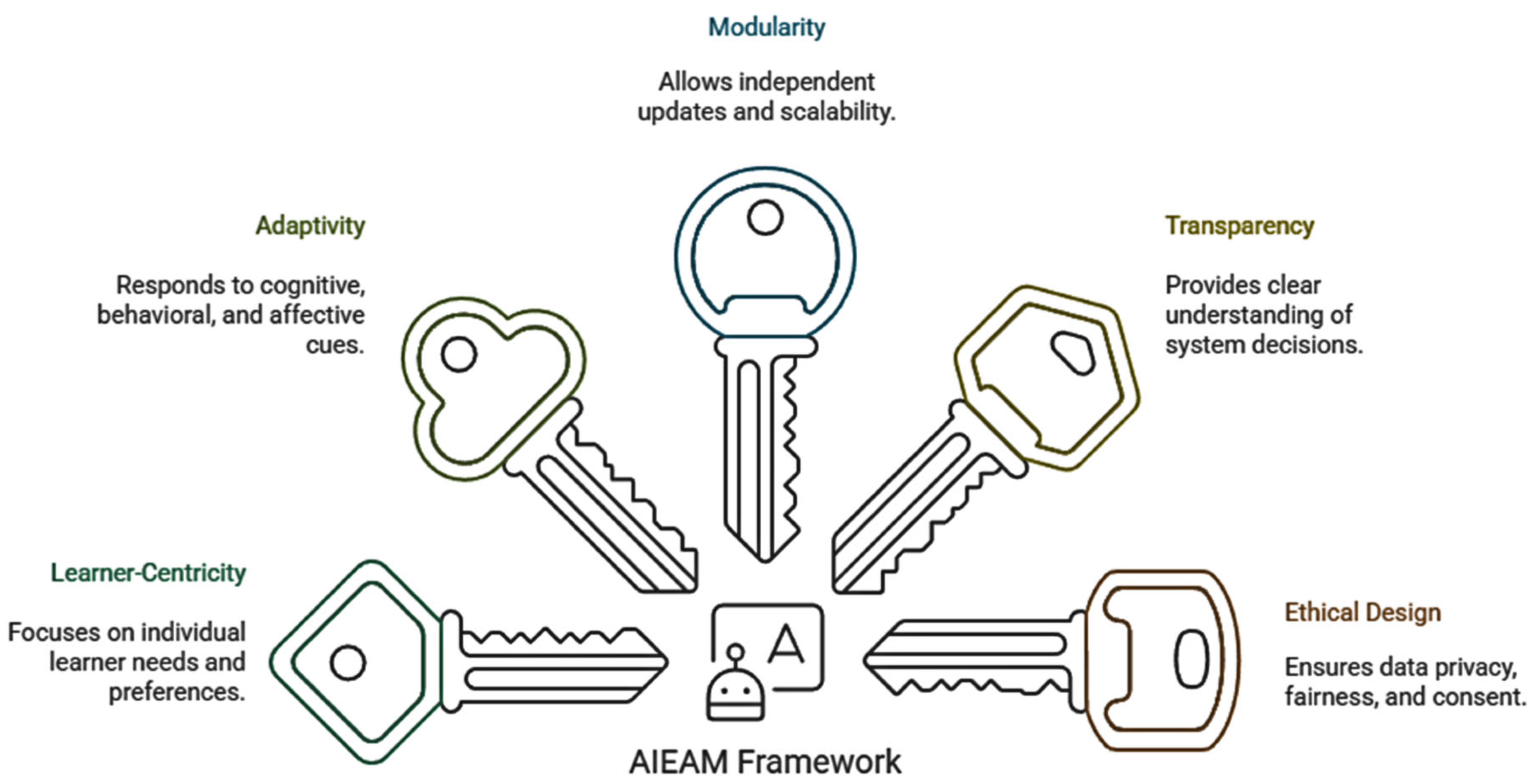

3.3. Design Requirements for an Integrated Framework

In order to overcome the fractured and obscure architectures of most current AI-enhanced instructional systems, we need to explicitly build a unified, flexible learning system whose parts interact with each other, both in terms of the technological promise of the field and in terms of the pedagogical necessity of effective teaching. The central point is that of learner-centricity: the framework should put the changing needs, preferences, and situations of individual learners at the centre of its logic, instead of optimising strictly towards efficiency or content coverage. Adaptation must be multidimensional in the sense that it must respond to both cognitive performance and behavioral cues and affective cues [

24].

Adaptivity, then, arises specifically as a result of the system being able to generate a model of a learners dynamic path in these several dimensions, and to act upon it. The framework can scale easily across disciplines, institutions and instructional models by using a modular architecture whereby learner profiling, content recommendation, feedback delivery, and progress tracking are each modules that can be updated independently. Such modularity also allows iterative refinement and future connection with emerging technologies or data sources without requiring a redesigning in their entirety [

25].

It is also important to provide systemic transparency. Both teachers and students need to have an idea of the decisions taken, the data used, and the alarms that lead to intervention. These adaptive processes are made interpretable and actionable by Explainable AI methods, thus enabling informed pedagogical control instead of operating in the dark by automation.

Ethical design cannot be considered as an add-on. The system should be designed to include mechanisms of data privacy, fairness, and learner consent in each of its components. These are some considerations that are necessary to the success of the framework: quality grounds of trustworthiness, adoption, and long-term impact [

26].

All these requirements comprise the conceptual scaffolding of the AIEAM framework, which aims to integrate adaptivity, intelligibility, scalability, and integrity into one, operational model of higher education.

Figure 2 highlights the five foundational design principles—modularity, adaptivity, learner-centricity, transparency, and ethical design—that form the conceptual scaffolding of the AIEAM framework.

4. The AIEAM Framework: An AI-Enhanced Adaptive Learning Model

4.1. Conceptual Overview and Theoretical Basis

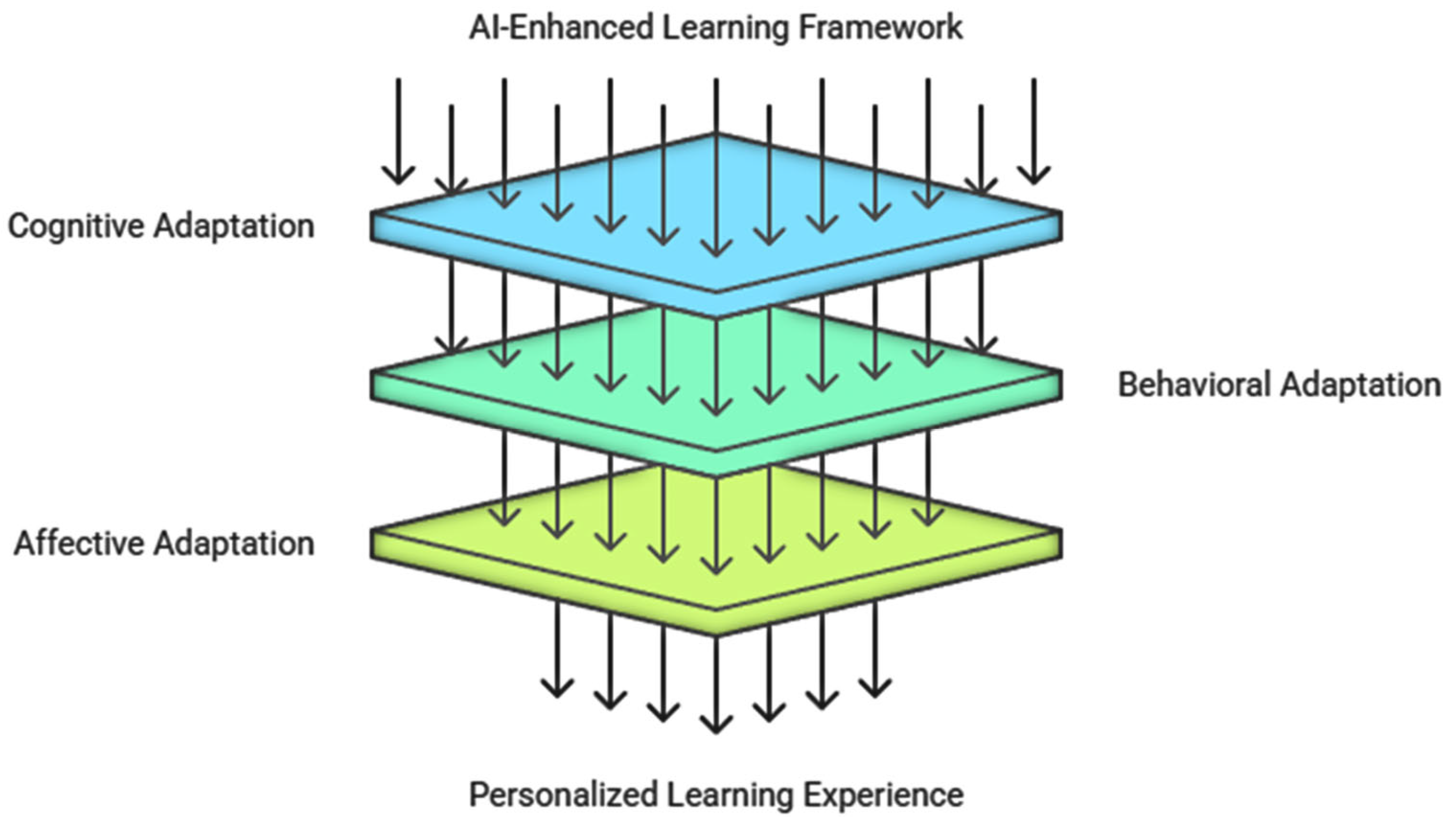

We would like to set our discussion in the context of one of the constructs we have been discussing in my research group: AIEAM, or the AI-Enhanced Adaptive Learning Model. AIEAM is to be a theoretical framework, which would combine artificial intelligence and evidence-based educational theory to promote personalized learning in higher education institutions.

Many adaptive learning platforms are limited to content-only modification, but AIEAM considers adaptivity as a multidimensional construct where cognitive, behavioral and affective aspects are addressed at the same time [

27]. In line with this, the framework instills intelligence in a layered architecture that is both flexible and pedagogically aligned.

AIEAM theoretical foundations are based on constructivist learning theory, cognitive load theory, and a self-regulated learning theory. Constructivism provides an epistemological justification of learner-centered design which states that knowledge is built during active involvement in tasks, feedback, and reflection. This principle explains why the framework focuses on learner agency, meaning that students are able to navigate, shape, and reflect their own learning trajectories [

28].

The cognitive load theory informs the order and the structure of the instructional material to ensure that learners are not overloaded with content to the point of cognitive overload. This way of thinking can be incorporated into the model to help it adjust the instructional pacing and the structure of the contents based on the personal processing capacity.

The self-regulated learning theory, in its turn, guides the feedback and metacognitive aspects of the model, prompting the learners to plan, monitor, and assess their learning behaviors.

The model does not only place computers as optimization engines but as intelligent mediators of learning experiences. As the result of this, AI applies the bidirectional adaptivity: systems adjust to students and offer guidance, which allows students to adapt their own learning approaches and, in this way, become more engaged and develop more self-awareness [

29].

Figure 3 visualizes the multidimensional adaptivity within the AIEAM framework, showing how cognitive, behavioral, and affective mechanisms jointly contribute to individualized learner trajectories.

AIEAM is actually meant to be used as a design model of adaptive learning systems as well as a pedagogical framework to educators, specifically because it takes into consideration the complexity of an institution. The architecture is purposefully modular, scalable, and domain-independent, which makes it applicable to implementation in a wide range of disciplines, course structures, and context. All components are configurable, making them easy to integrate with existing learning platforms, assessment and analytics systems [

30].

AIEAM contributes to the vision of personalized learning not by substituting teachers or automating instruction, but by smartly supplementing these with structure, insight and flexibility.

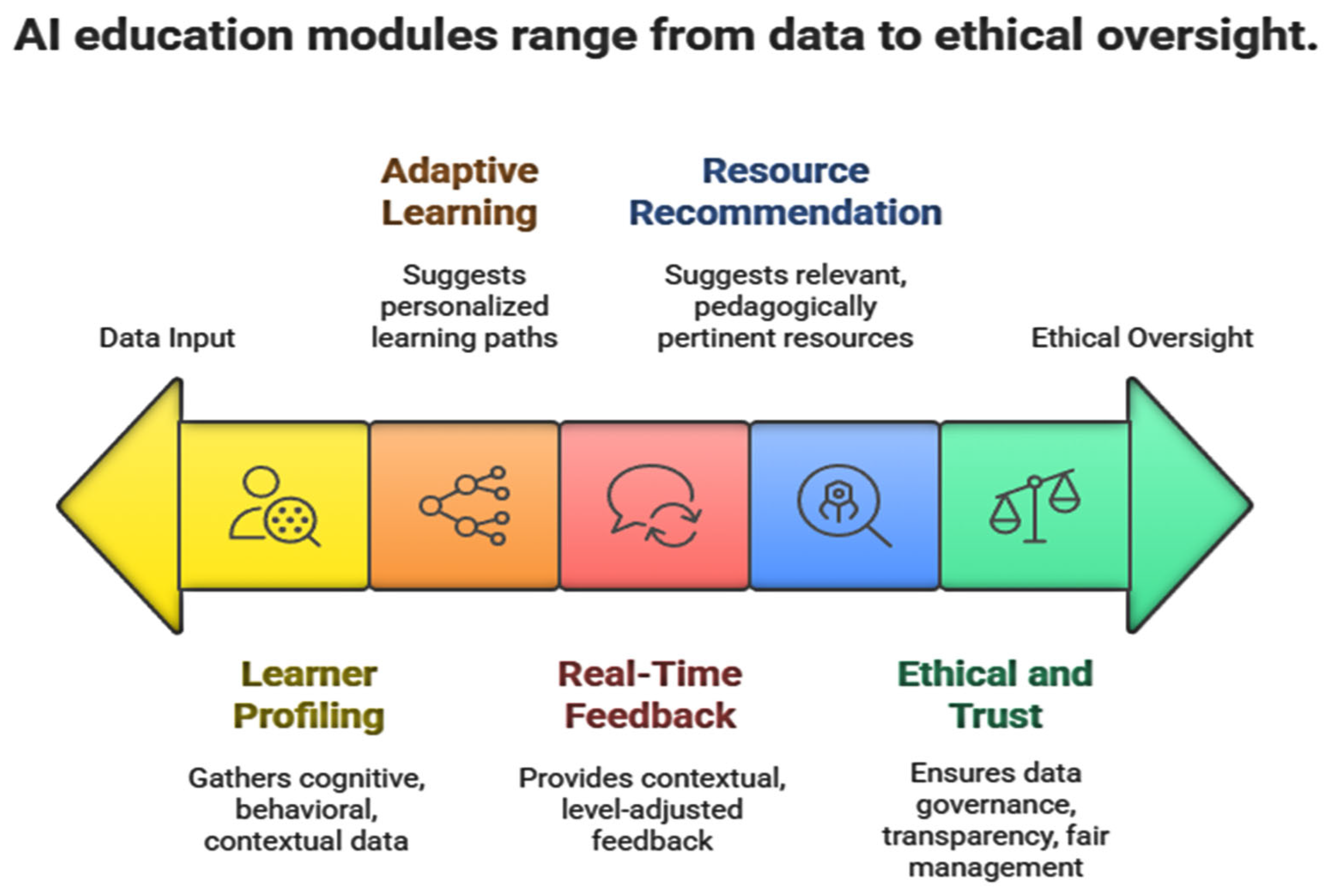

4.2. Functional Architecture and Core Modules

In the field of AI-enhanced educational architecture, a schema usually referred to as AIEAM consists of five interrelated functional modules, each addressing a separate level of pedagogical adaptivity. When used together, these modules are semi-autonomous parts in a larger system, which therefore perpetuates data flow, real-time adjustment, and strict pedagogical alignment. This kind of synchrony is the foundation of a responsive and theoretically justifiable form of personalization [

31].

The Learner Profiling Module is the basic construct of the framework. In this case, cognitive, behavioral, and contextual data, including previous academic performance and the history of interaction, learning preferences, and even affective indicators, such as engagement or frustration, are merged, which results in the multidimensional profile of each learner. More importantly, such profile is dynamic, continuously revised in successive interactions [

32]. The module ties the architecture to learner-centered design by enabling the system to discriminate between learners and to differentiate interventions accordingly instead of using generic prescriptions.

The Adaptive Learning Path Generator uses the knowledge extracted in the learner profile to suggest personalized learning paths, rates, and task typologies. This module, which uses machine-learning algorithms to interpret patterns of progress, dynamically optimizes the flow of instructions. As a result, learners will be pursuing courses that reflect their developing readiness and learning style preference, and yet will be working toward common standards. The multiple trajectories to mastery supported by the module recognizes the fact that various students tend to have varied paths to mastery [

33].

The Real-Time Feedback and Assessment Engine forms the feedback and summative-evaluation part of the architecture. In this case, quiz answers, written assignments and behavioral clues undergo ongoing, contextual interpretation and the learners get feedback that is adjusted to their current level of learning. When used together with the self-regulated learning theory, this engine does not only provide traditional correctness feedback but also scaffolding questions, confidence monitoring, and metacognitive prompts, thus, supporting reflective practice [

34].

The Resource Recommendation Subsystem suggests additional resources to the learner such as videos, readings, practice exercises, or the chance to interact with peers and is based on the current level and objectives of the learner. The learner profile and historical efficacy data serve as selection criteria, and are both relevant and pedagogically pertinent.

The foundation of the whole business is the Ethical and Trust Layer, which is responsible to take care of data governance, transparency, and fair management. This module protects responsible collection and deployment of learner data by means of consent, algorithm auditability, and bias mitigation. It is the keystone of the institutional and learner trust in AI-mediated education settings [

35].

These five modules when integrated together form a strongly integrated architecture, an architecture that can strike a balance between algorithmic automation and human-centered design and thereby allow AIEAM to learn and respond intelligently and ethically to the complicated needs of higher education.

Figure 4 illustrates the five core functional modules of the AIEAM framework—ranging from data-driven learner profiling to ethical oversight—each playing a vital role in enabling scalable, adaptive, and responsible personalized education.

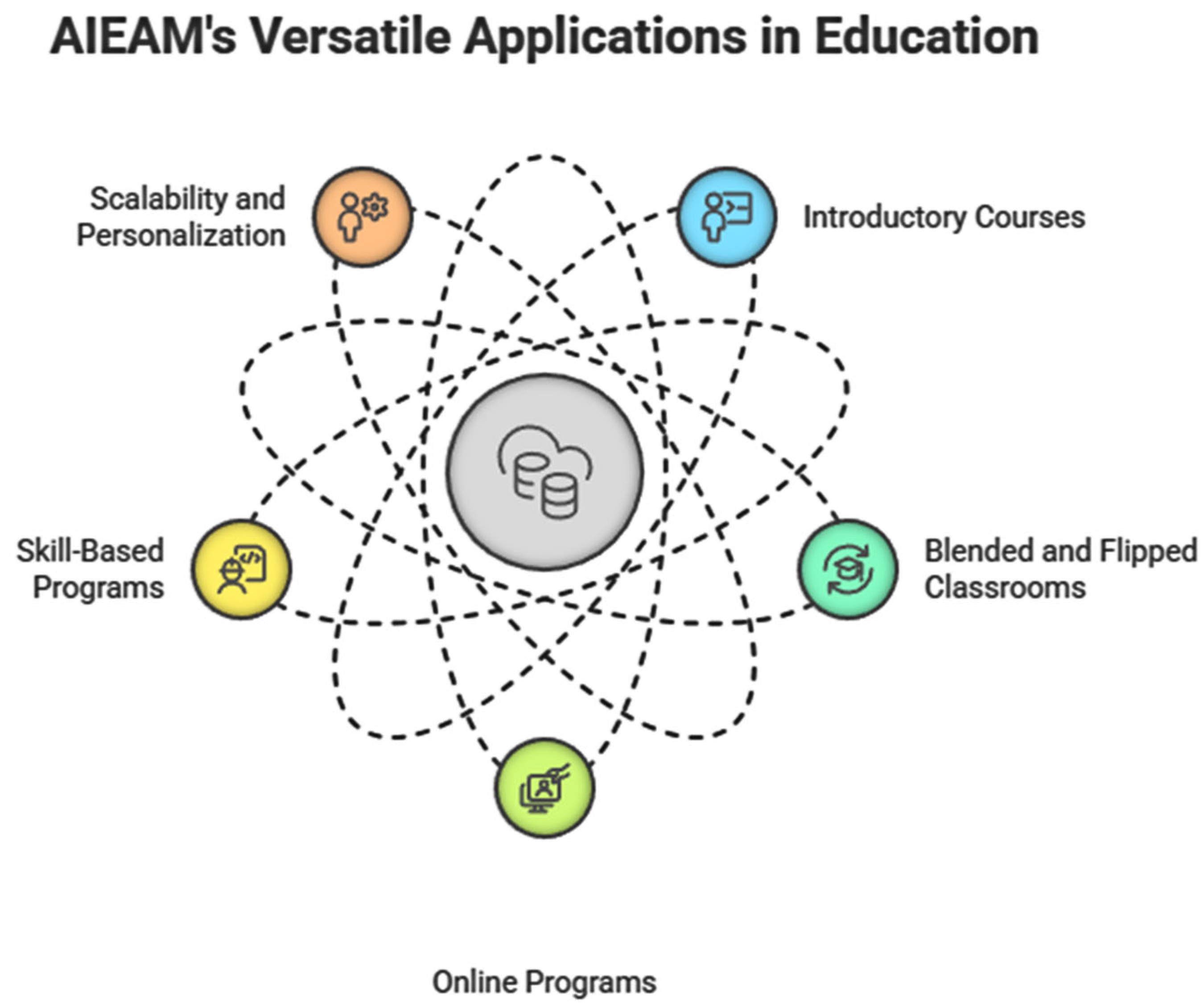

4.3. Application Scenarios in Higher Education

The flexibility and modularity of AIEAM has enabled its application in a wide range of teaching environments throughout the modern higher education matrix. Whereas other frameworks are anchored to a specific discipline or delivery model, AIEAM is specifically intended to accommodate a broad range of learning modalities, including large-format introductory courses, blended-learning and flipped classrooms, fully online degree programs, and skills-based certification programs [

36]. Critically, the framework does not require one platform to be implemented; it can be integrated into any learning ecosystem within an institution, or third-party learning management system (LMS), as long as it has enough access to learner interaction data and integration APIs.

In introductory courses like calculus, academic writing, or computer science, teachers are usually faced with the dilemma of offering individual attention to the diverse groups of students. The learner profiling and adaptive path generation modules provided by AIEAM provide a solution in that learners are dynamically grouped based on their needs and differentiated content is recommended without adversely affecting course cohesion. To give an example, students who show mastery earlier can be offered fast-tracked options, but students who struggle have more detailed scaffolding, formative tests, and low-stakes practice [

37].

AIEAM in blended and flipped classrooms can facilitate asynchronous individualization and can supplement synchronous teaching. Before the lesson, the students are exposed to materials prepared by AI, based on their learning profiles. With the knowledge of the real-time feedback engine, instructors can then use the classroom time to address common misconceptions or help students work together. Such a redistribution of teaching effort increases the efficiency of instruction without reducing student involvement.

Online programs which are usually plagued with learner isolation and dropout potential benefit greatly by the constant feedback and personalized resource suggestion that AIEAM offers. The learners are given timely cues and recommendations that foster self-control and keep them on track. Instructors, in their turn, will have access to the engagement patterns of the learners and will be able to intervene in time when the signs of disengagement occur [

38].

Remediation and progression mapping can also be done through skill-based programs, like data science bootcamps, or in language acquisition tracks, that can use AIEAM. The modularity of the framework allows the incorporation of external competency frameworks, which allows a fine grain tracking of the acquisition and mastery of skills.

AIEAM promotes a wide range of delivery methods and instructional designs, which at the same time increase personalization and scalability. Its flexibility means that schools will be able to implement the framework according to their own pedagogical beliefs, resource limitations, and technological capabilities, which makes AIEAM a flexible response to the changing needs of higher education.

Figure 5 illustrates the flexible applicability of the AIEAM framework across various educational formats, including introductory courses, blended classrooms, online programs, and skill-based tracks.

4.4. Summary of Framework Innovations

Within this context of an emerging body of adaptive learning systems, AIEAM stands out as an initiative that not only promises to have a paradigm-shifting impact but does so not only on the level of technological sophistication but, more importantly, on the level of how it integrates theoretically-derived constructs, pedagogical principles, and system architecture into a unified paradigm of operation. The main innovation lies in its multidimensional adaptivity: unlike the majority of systems, which bind their responsiveness to cognitive performance measures, AIEAM would carry such responsiveness to behavioral indicators, affective status, and a range of context variables. This broad diagnostic lens allows a more subtle understanding of learner variability and thus a more subtle model of personalization [

39].

The other, yet also significant, innovation is the frankly direct inclusion of educational theory in every system element. Both tasks engagement by the learner and the creation of individual paths are founded on constructivist principles. Cognitive Load Theory also guides the order and timing of information. The design of reflective feedback and metacognitive prompts is, in its turn, framed using self-regulated learning theory. Such theoretical lenses do not represent post-hoc rationalizations, but are part and parcel of the architecture of the system, which determines how data is interpreted, how decisions are made, and how interventions are delivered.

The modular constellation of AIEAM is another step away of the homogenous, platform-based systems that the previous adaptive systems have been. All the modules, such as learner profiling, path generation, feedback engine, resource recommendation, and ethical oversight, have the potential to work independently or to be smoothly incorporated into an elaborate system [

40]. This modularity maximizes the scalability, institutional integration, and supports a variety of technological infrastructures that allow institutions to choose to use a fully systemic solution or a component-based solution that is specific to a discrete instructional problem or technology environment.

Transparency is one more pillar of the methodological architecture of AIEAM. The fact that explainable AI mechanisms are combined with configurable dashboards allows the learners as well as educators to understand the functioning of the system logically. This kind of transparency builds trust and gives the instructor a desire to intervene and eventually promotes learner agency. The system does not replace the instructors, but rather enhances their ability to provide data-powered assistance at scale.

Moral consciousness, last but not least, is not an extrinsic addition but a logic in itself. Ethical protections run the gamut of data privacy and algorithmic fairness, informed consent and auditability, and cut across every level of the system. Such a preventive approach satisfies not only the compliance needs but also supports the validity and the sustainability of AI-augmented learning in formal education [

41].

In combination, these innovations place AIEAM as a progressive framework that balances technological potential with scholastic integrity, and thus provides a solid basis of adaptive learning in complex, diverse, and changing higher-education settings.

5. Case-Based Validation

5.1. Methodology and Case Selection

When evaluating the validity of AIEAM, we avoid such isolated measures as indicators or artificial experimental conditions. Instead, we base our investigation on systems that already exist in large scale and operate under the conditions that are similar to the ones that are common in modern universities. These systems are not being reproduced, and are not being retroactively framed as AIEAM artifacts; instead, we want to check whether the component parts and overall design logics of the framework can be made to work in actual instructional settings.

Two examples picked in this regard are Squirrel AI and Carnegie Learning (MATHia). Both can be placed in a large volume of research and practice, offering competing examples of AI-based adaptivity. The Chinese-based Squirrel AI is characterized by its granular diagnostic equipment and real-time content modification; it has been implemented on a large scale and is linked to quick remediation and extremely personalized pacing. Carnegie Learning is a US-based company with a complementary model, based on cognitive theory and intelligent-tutoring principles, having strong links with formal curricula and everyday classroom practices [

42].

Each case is analyzed using a three-level analytic sequence as follows: (1) brief description, (2) mapping of the system components against the AIEAM framework, and (3) reflections on the lessons learnt in the mapping process. The focus is not on performance measures but on structural congruence as the main theme, thus explaining whether practical instantiations resemble the theoretical structure of AIEAM, and, consequently, define the future design discussion.

5.2. Case Study 1: Squirrel AI

5.2.1. Overview of Squirrel AI

Squirrel AI is an adaptive learning architecture designed by YiXue Education in China and is of large scale. Currently, it is used in thousands of instructional centres and schools, mostly in K-12 environments, but its guiding principles also continue to apply to higher education environments. At its core is an AI-based engine that performs a fine-grained diagnosis, identifying gaps on the level of mastery of concepts. The diagnostic assessments are not fixed: they are constantly updated based on learner responses, allowing on-demand adjustments to be made to content ordering and challenge [

43].

One of the peculiarities of Squirrel AI is granular knowledge map, which breaks down subject areas into micro-concepts. The students will not be promoted based on the completion of the unit but based on proficiency of each concept. The system incorporates real-time feedback, confidence monitoring as well as temporal-efficiency measures to enhance learning trajectories even further. Teachers can look at analytical dashboards to check the progress and help in areas where it is needed, but the system is designed in such a way that it will be highly independent.

Various scholarly analyses have been conducted to check the ability of Squirrel AI to provide individualised teaching on a large scale. Its hybrid structure, which is a combination of machine learning algorithms and decision trees, offers a dynamic system, which is, to some extent, explainable. These aspects make it a smart choice to be compared to the AIEAM framework.

5.2.2. Alignment with AIEAM Components

In the modern context of adaptive instructional systems, Squirrel AI stands out as an impressive example, directly referring to some of the fundamental principles that are outlined in the AIEAM framework. The most important of these include (a) the learner profiling module, (b) the adaptive learning path generator, and (c) the real-time feedback and assessment engine.

As far as the learner profiling is concerned, Squirrel AI gathers information about concept mastery, response accuracy, temporal variables, as well as the confidence of the learner, which makes it develop dynamic profiles that can be real-time recalibrated. This type of real-time updating and multidimensional modeling is very similar to the focus on constant improvement of the AIEAM Learner Profiling Module [

44].

Moving to the issue of adaptive content sequencing, the sequencing engine that Squirrel AI uses works by using diagnostic assessments and current performance to identify the next concept or task, methods that are similar to the Adaptive Learning Path Generator in AIEAM, which similarly does not rely on linear content flows but rather adapts instructional paths to the changing needs of an individual learner. In such a way, the system demonstrates AIEAM non-static instructional design.

Squirrel AI does not give as much emphasis on real-time feedback as it would on correctness and pacing efficiency, not metacognitive or affective planes. It therefore has less or no alignment to the Real-Time Feedback and Assessment Engine in AIEAM which extends feedback to the reflective and regulatory planes.

A second area of divergence is ethical and trust-related aspects. Despite the strong functional similarity between Squirrel AI modular architecture and adaptive capabilities and AIEAM, it does not include an explicit ethical or trust layer, making data governance unconfigurable and opaque.

In a nutshell, Squirrel AI presents a strong combination of AIEAM principles of learner profiling, adaptive sequencing, and real-time feedback, and its shortcomings in the ethical and affective feedback aspects are to be focused on.

Figure 6 illustrates how the core components of Squirrel AI align with the AIEAM framework, revealing both areas of strong correspondence (e.g., learner profiling and path generation) and notable gaps (e.g., ethical governance and metacognitive feedback).

5.2.3. Key Insights and Observations

A methodical study of Squirrel AI using the theoretical lens of the Adaptive Instructional Event Modeling (AIEAM) reveals both similarity and difference. The scalability of the platform demonstrates that fine-grained modeling of the learner and dynamically reconfigurable pathways are capable of functioning effectively, even in classes with a significant enrollment. Its ability to identify granular micro-concepts and to personalize instructional material in real time proves AIEAM right in its insistence on modular responsive architecture and shows that adaptive strategies can be based not on generalizations about large groups of learners but can be effective at the level of individual knowledge states [

45].

One of the most outstanding results is the sufficiency but biasedness of the feedback design of Squirrel AI. The system enables effective correction of performance in good time, but it lacks metacognitive hints and does not encourage reflection on the part of the learner, which is the core of the powerful feedback engine in AIEAM. This shortcoming highlights the need to go beyond the performance realm of adaptive systems to promote self-regulative approach and agency of learners.

Another teaching aspect is transparency. Despite the fact that some decisions made by Squirrel AI can be explained with the help of necessary analytics dashboards, the internal logic of the AI is rather unavailable to learners. This fact makes the need to have explainable AI in adaptive learning critical especially in higher education where learner trust and instructor control becomes extremely vital.

Squirrel AI confirms numerous practical assumptions of the AIEAM framework and at the same time demonstrates the spheres where theoretical constructs are under-realized in practice.

5.3. Case Study 2: Carnegie Learning (MATHia)

5.3.1. Overview of Carnegie Learning

The MATHia by Carnegie Learning is an advanced, AI-based tutoring platform carefully designed in the United States to teach secondary and postsecondary mathematics. Based on decades of cognitive-science research and guided by the ACT-R theoretical model, MATHia goes beyond the traditional purpose of a content-delivery system: it acts as a cognitive tutor, with the ability to simulate the dynamics of individualized, one-on-one human teaching and to dynamically adapt its difficulty, task sequence, and instructional focus to the changing needs of each learner in terms of performance and strategy [

46].

At the heart of this responsiveness is a knowledge-tracing algorithm that constantly tracks a student in terms of his/her mastery of particular mathematical skills and concepts, thus enabling real-time adaptive sequencing. Feedback is timely, multidimensional, and situationally appropriate and this includes hints, error-relevant information, and problem decomposition strategically partitioned. Designed in an integrative fashion, MATHia does not incorporate the binary classification that usually characterizes computer-based assessment: it uses the multi-step modeling to assess how a learner approaches a problem but not whether their answer is correct or incorrect.

To supplement this user-centered design, it offers a full suite of analytics that provides instructors with data-rich information about the trajectories of students. Predictive models estimate what is likely to happen, and longitudinal data allows intervention at the right time and planning of instruction. Even though the platform is domain-specific, the fact that it involves the cognitive theory, adaptive sequencing and strong feedback mechanisms make it a useful point of comparison when it comes to the assessment of the AIEAM framework in a formally theorized, formalized instructional setting [

47].

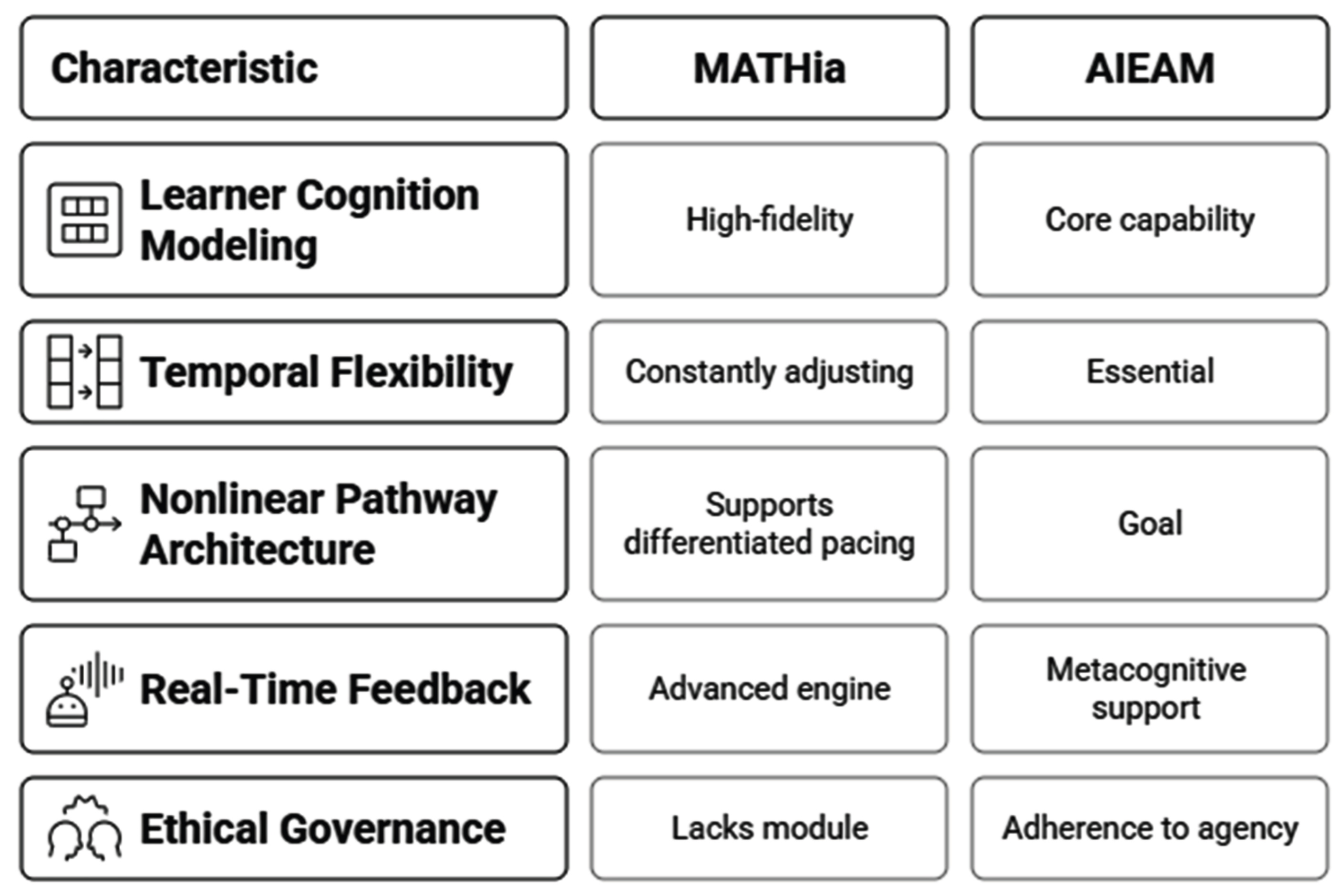

5.3.2. Alignment with AIEAM Components

In the new domain of adaptive instructional engineering, MATHia provides a good example of how an educational system can help to implement the Application of Intelligent Educational Agent Methods (AIEAM). In particular, the system has high-fidelity learner cognition modeling and updates its representation of an individual skill set in real time core capabilities that are the articulation of both the Learner Profiling Module and the Knowledge Tracing algorithm in AIEAM. These profiles inform decision-making processes of the system and, therefore, mediate adaptive task sequencing of the system.

AIEAM notes that temporal flexibility is essential in a learning sequence; MATHia reflects this notion by constantly adjusting the flow of instructions so that every learner can be presented with tasks at the right cognitive level. The platform provides a means of nonlinear pathway architecture by supporting differentiated pacing and multiple route-to-mastery trajectories, which are the goals of AIEAM.

The advanced Real-Time Feedback and Assessment Engine of the system is also quite impressive. Remediation strategies and instructional interventions are provided at several levels of conceptualization, which allows learners to keep track and control their learning, which is also in line with the framework, which focuses on metacognitive support and self-regulated learning.

Even though MATHia lacks a dedicated ethical governance module, its openness in terms of providing feedback and visualizing data confirms its adherence to learner agency. The instructors can view detailed diagnostic reporting, and the learners can have continual progress indicators. All these characteristics make the MATHia an interesting benchmark on the way to the AIEAM implementation of the pedagogical perspective.

Figure 7 illustrates how MATHia’s core components align with the AIEAM framework, demonstrating strong consistency in learner profiling, adaptive sequencing, and metacognitive feedback, while lacking a formalized ethical governance module.

5.3.3. Key Insights and Observations

MATHia is a perfect example of how a theory-based adaptive system, based upon the learner-profile framework of AIEAM, can not only be resilient, but also sensitive to the contextual variables. The fact that it includes cognitive modeling offers strong support to the notion that AIEAM profiling is not at all about surface-level performance indicators. Since MATHia is able to trace sequences of moves in complex, multistep problem-solving tasks and adjust instruction accordingly, it illustrates pedagogical benefit of the finely grained adaptivity in the process of developing deeper learning outcomes.

One of the most important insights can be achieved through the analysis of the instructional logic of the system. MATHia does not merely recommend content, but aligns instructional choice with a specific model of skill building. This orientation highlights the main idea of AIEAM: flexibility and pedagogical integrity can go together. Besides, feedback architecture of the system allows not only to stop the task but also to keep on thinking, which helps to see that adaptive design can be used to develop metacognition rather than to develop rote automation.

But the success of the system is however limited by its domain specificity. MATHia is an excellent example of an adaptive system architecture in mathematics, but it can hardly be translated to other fields. It is this constraint that reminds us that frameworks like AIEAM have to strike a balance between generalizability and intellectual depth.

Overall, MATHia provides unequivocal support that, when theory and system design are carefully intertwined, modular, cognitively-based, and feedback-rich structures can actually reflect the main principles of AIEAM: modularity, cognitive modeling, and learner-centric feedback.

5.4. Cross-Case Analysis and Synthesis

A critical review of Squirrel AI and MATHia will both expose the points of overlap as well as the points of departure in relation to the AIEAM framework. The two platforms share some essential features, namely, learner profiling and adaptive path generation, that signify the feasibility of carrying out real-time, data-driven differentiation in terms of implementation in a variety of educational and cultural contexts. Both systems have an adaptive learner model, algorithmic decision-making to individualize instructional material, and provide instant feedback. Such similarities confirm the architecture of AIEAM.

The differences arise in focus and approaches to methodology. Squirrel AI has a high focus on scalability and diagnostic precision and is efficient when used in large-enrollment settings with minimal instructor interaction. MATHia, in its turn, is more consistent with cognitive theory and provides more elaborate feedback mechanisms that can encourage reflection and self-regulation among learners. Such differences make clear the modular nature of AIEAM: it is elastic enough to support different design philosophies [

48].

The two systems, however, are deficient in the ethical layer of governance as projected by AIEAM, which remains a gap in adaptive learning environments. Transparency, user control and fairness are not core elements. This inadequacy is a reason why a principled, structurally embedded approach to ethics is required.

The two case studies together offer an empirical support to AIEAM and prove its applicability to diverse implementations, which is an indication of conceptual strength as well as practical flexibility.

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Fellow professionals, we would like to address the AIEAM framework, pronounced as eye-jem, as a methodical way of integrating artificial intelligence into personalized learning without compromising on the well-known educational theory. In essence, AIEAM unifies constructivism, cognitive load theory and self-regulated learning on a single, modular, AI-compatible framework. Such tripartite synthesis provides a forecasting roadmap of designing systems that go beyond personalization and reactive adaptivity to a more profound, theory-based adaptivity.

Practically, AIEAM provides instructional designers and system developers with practical advice on how to scale the implementation of adaptive technologies. Its modular design allows it to be implemented in components, allowing institutions to integrate discrete functionality, without requiring large-scale system redesigns, e.g. real-time feedback, learner profiling, etc. Teachers, on their part, can go on making sound pedagogical decisions with the help of AI and not be replaced or sidelined by automation [

49].

Two case analysis examples show how the framework is viable in practice and at the same time highlight the weaknesses of existing applications. The lack of open and ethical design practices even in the more complex systems, suggests that future versions of adaptive learning will need to be rooted in the frameworks like AIEAM. As the use of adaptive technologies gradually increases, the framework is offering a neutral path, the path that will bring balance between scale and interpretability, automation and pedagogical intent.

6.2. Strengths and Limitations of AIEAM

Within the galaxy of the modern higher-education systems, AIEAM has developed a model that is both organized and flexible, which is quite appropriate to the complexities of the modern learning environment. The main operational characteristic is the modular design that allows the partial implementation of individual modules in the heterogeneous institutional environment and maintain the coherence of the entire framework. Since the architecture does not imply any homogeneity in content, learner behavior, or instructional goals, it can easily be adopted to many disciplines, pedagogical models, and technological infrastructures.

Another difference of AIEAM is its intentional adherence to the existing learning theories; the adaptivity is thus guaranteed not as a convenient adaptation to the current situational needs but as a pedagogically profound process. The framework combines AI-intensive procedures with cognitive, metacognitive, and behavioral constructs, which further promote personalization, which is not confined to superficial measures. Of equal importance is its overt ethical and trust layer: data privacy, algorithmic transparency and learner autonomy are explicitly stated as core system considerations, and not as secondary add-ons [

50].

Despite these developments, AIEAM is a theoretical framework that has not been implemented on a large-scale operational level. Its usefulness in non-STEM areas does not eliminate the necessity of empirical verification. Moreover, real-time synergistic operation between each module is practically problematic, especially in cases where legacy LMS infrastructures are used. These constraints indicate areas that can be improved and confirmed by situated implementation.

6.3. Comparison with Existing Models

In the context of adaptive learning, existing models have generally been restricted to a single level of personalization, usually restricted to content sequencing or performance-based branching. These systems are usually proprietary systems, prioritizing algorithmic optimality and are broadly loosely coupled with pedagogical theory. By contrast, the Adaptive Instructional Ecosystem for Active Reflection (AIEAM) proposes a multi-layered theoretically consistent architecture that integrates an AI-based adaptivity with cognitive, behavioral and ethical aspects of learning.

As an example, mastery-learning models and Bayesian-knowledge-tracing frameworks provide convenient personalization mechanisms, but their main requirements, namely, accuracy and forward progress, tend to overshadow the chances of reflection and self-regulation. These systems are often opaque and have low learner agency though they are effective in controlled teaching contexts. AIEAM fills these gaps through the inclusion of explainable adaptation, dynamic learner profiling, and feedback loops that are aimed at fostering metacognitive maturation.

Compared to proprietary systems like Knewton and ALEKS, which personalization is integrated into closed and proprietary architectures, AIEAM represents a modular, open-source structure that fosters interoperability with existing instructional systems and aligns with institutional pedagogical goals. The existence of the explicit ethical layer makes the framework stand out even more, making it not only focused on the efficiency of the instructions but also on justice, confidence, and enabling the user. Such an enlarged ethical space is an indication of a paradigm shift toward more responsible and educationally based adaptive learning models.

6.4. Recommendations for Implementation

The introduction of AIEAM in modern higher-education environments requires a gradual, step-by-step approach, which is based on the institutional capacity, technological infrastructure, and existing culture of instruction. The first step that universities should take is to identify particular instructional problems (high dropout rates in introductory courses, low online module participation rates, etc.) and align them with the relevant elements of AIEAM. Such a targeted solution allows adoption to be done gradually without straining current systems.

Technically, interoperability should be given precedence in implementation. Instead of requiring new platforms, AIEAM modules can be overlaid on existing learning management systems with APIs and learning analytics dashboards. Clear information flow and user-controllable options are supposed to be highlighted, so that instructors and learners maintain control and have an understanding of the adaptive processes that are taking place.

Faculty development is also essential. More than access to adaptive tools, instructors should have a systematic training that includes interpreting learner profiles, adjusting pedagogy, and incorporating AI-generated feedback into the classroom. Without this support the pedagogical potential of AIEAM risks going unexploited.

Institutional policies should be formulated to explain the ethical priorities of AIEAM. Prior to any large-scale deployment, clear principles regarding the use of data, accountability of algorithms, and learner consent must be spelled out. It cannot be technological preparedness only, the success will be determined by the institutional cultural alignment with the philosophy of adaptive, learner-centered education.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Summary of Findings

The current study proposes AIEAM, a conceptually based and modular framework developed to guide the development and implementation of AI-augmented adaptive learning environments in higher education. Unlike most of the existing models that focus only on personalization of content or algorithmic effectiveness, AIEAM incorporates cognitive, metacognitive, behavioral, and ethical threads into a single design. The scheme, by combining the established educational theory with the potential of modern AI, provides a consistent framework of meaningful personalization, learner-centered, at scale.

The framework is comprised of five interlocking modules: the learner profiling, adaptive path generation, real-time feedback and assessment, resource recommendation, and ethical and trust layer. The modules can be used independently or in combination with each other, and therefore allow a flexible deployment in diverse education settings, as well as technology stacks. The clear inclusion of ethical aspects as a central modular unit is a radical shift in terms of traditional designs, which highlights the necessity of developing trust, transparency, and learner autonomy.

The validation of cases was done by examining Squirrel AI and Carnegie Learning (MATHia) to demonstrate how existing adaptive systems represent the main design principles of AIEAM, even though they were developed independently of each other. The analyses pointed out the plausibility of the framework parts, as well as the gaps that are still present, especially in the areas of transparency and ethical embedding.

All the results, together, provide evidence of the relevance and usefulness of AIEAM as an adaptive learning system guideline in the future that is at once scalable and pedagogically valid.

7.2. Implications for Future Research and Practice

We would like to suggest to colleagues that AIEAM, the Adaptive Instructional and Educational Analytics Model, may be taken as a scaffold to reframe and re-imagine the way we conceptualize, develop, and implement adaptive learning systems in post-secondary education. Its conscious emphasis on modularity, theoretical coherence and ethical supervision provides the research agenda with an entry point beyond the search of isolated algorithmic tweaks. Empirical questions may start with questions about separate elements, asking about the interaction between them, and tracing the ways in which variables like discipline, student demographics and institutional objectives mediate their effectiveness.

Longitudinal studies, especially mixed ones, can provide more insight into more common use. The ability to track adoption in heterogeneous contexts would allow the researchers to track dashboard metrics, as well as qualitative data on learner retention, engagement, and cognitive development, thus revealing usability gaps and providing input to iterative design.

AIEAM has forced instructional designers and educational technologists to shift away tool-oriented implementation to framework-based integration. The model provides institutions with a guide on how to scale adaptive learning initiatives without losing the main focus of pedagogical intent and the ethical considerations.

The model welcomes interdisciplinarity. Full realization of AIEAM will involve the cooperation of computer scientists, educators, learning theorists and data ethicists. This convergence is bound to produce more advanced, equalized, and pedagogically-sensitive adaptive learning systems, which can satisfy the changing needs of the higher education environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-A.L. and S.-Y.S.; methodology, H.-A.L., S.-Y.S., and Y.X.; writing original draft preparation H.-A.L., S.-Y.S., and Y.X.; supervision, S.-Y.S. and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thakkar, D. Reimagining curriculum delivery for personalized learning experiences. Int. J. Educ. (IJE) 2020, 2, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Sánchez, A.; Lorenzo-Castiñeiras, J. J.; Sánchez-Bello, A. Navigating the future of pedagogy: The integration of AI tools in developing educational assessment rubrics. Eur. J. Educ. 2025, 60, e12826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, P. D.; Ghosh, N.; Chen, Y. Faculty burnout in higher education: Effects on student engagement, learning outcomes, and artificial intelligence-driven institutional responses. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland-Innes, M.; Emes, C. Principles of learner-centered curriculum: Responding to the call for change in higher education. Can. J. High. Educ. 2005, 35, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Ayres, I.; Fisteus, J. A.; Delgado-Kloos, C. Lostrego: A distributed stream-based infrastructure for the real-time gathering and analysis of heterogeneous educational data. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 100, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, B. Inequality and access to education: Bridging the gap in the 21st century. Rev. J. Soc. Psychol. Soc. Work. 2024, 1, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, M. M. Rapid response to a tree seed conservation challenge in Hawai‘i through crowdsourcing, citizen science, and community engagement. J. Sustain. For. 2022, 41, 605–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel-Walcutt, J. J.; Gebrim, J. B.; Bowers, C.; Carper, T. M.; Nicholson, D. Cognitive load theory vs. constructivist approaches: Which best leads to efficient, deep learning? J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2011, 27, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmock, C.; Tan, C. Y.; Nguyen, D.; Tran, T. A.; Dinh, T. T. Implementing education system reform: Local adaptation in school reform of teaching and learning. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 80, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, W. Personalized college English learning based on artificial intelligence: Algorithm-driven adaptive learning method. Int. J. High Speed Electron. Syst. 2024, 2540102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Niu, J.; Zhong, L. Effects of a learning analytics-based real-time feedback approach on knowledge elaboration, knowledge convergence, interactive relationships and group performance in CSCL. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 53, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M. Language teachers’ assessment literacy in AI-aided adaptive learning environments. J. Res. Appl. Linguist. 2024, 15, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fusarelli, L. D. Tightly coupled policy in loosely coupled systems: Institutional capacity and organizational change. J. Educ. Admin. 2002, 40, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. M. Constructivism: Paradigm shift from teacher centered to student centered approach. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2016, 4(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrieling, E.; Bastiaens, T.; Stijnen, S. Effects of increased self-regulated learning opportunities on student teachers' motivation and use of metacognitive skills. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 37, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, B. S.; Kersten, B.; Sweller, J. Learner control, cognitive load and instructional animation. Appl. Cognit. Psychol. 2007, 21, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenubi, O. A.; Samuel, N.; Oyenuga, A. O. A framework for education technology integration in Nigerian basic school system: Digital framework for technology integration in education (diftie) for basic school system. Univ. Ibadan J. Sci. Log. ICT Res. 2025, 13, 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, D.; Kovanovic, V.; Ifenthaler, D.; Dexter, S.; Feng, S. Learning theories for artificial intelligence promoting learning processes. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 1125–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muvva, S. Ethical AI and responsible data engineering: A framework for bias mitigation and privacy preservation in large-scale data pipelines. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, W. S.; Webb, M.; Goldhorn, J.; Peters, M. L. Examining the impact of critical feedback on learner engagement in secondary mathematics classrooms: A multi-level analysis. AASA J. Scholarsh. Pract. 2013, 10, 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zohuri, B. Artificial intelligence and machine learning driven adaptive control applications. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, G. Unveiling the black box: Bringing algorithmic transparency to AI. Masaryk Univ. J. Law Technol. 2024, 18, 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaumer, A.; Pope, A.; Neville, K. A framework for applying ethics-by-design to decision support systems for emergency management. Inf. Syst. J. 2023, 33, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart-McKoy, M. A. "Digitize Me": Generating E-Learning Profiles for Media and Communication Students in a Jamaican Tertiary-Level Institution. J. Educ. Online 2014, 11, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Almgren, A.; Bell, J.; Berzins, M.; Brandt, S.; Bryan, G. ;... Weide, K. A survey of high level frameworks in block-structured adaptive mesh refinement packages. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. User perceptions of algorithmic decisions in the personalized AI system: Perceptual evaluation of fairness, accountability, transparency, and explainability. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2020, 64, 541–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. M. C.; Wang, P. Y.; Lin, I. C. Pedagogy*technology: A two-dimensional model for teachers' ICT integration. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Lundberg, A.; Ayari, M. A.; Naji, K. K.; Hawari, A. Examining engineering students' perceptions of learner agency enactment in problem- and project-based learning using Q methodology. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 111, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrar-ul-Haq, M.; Anwar, S.; Hassan, M. Impact of emotional intelligence on teacher's performance in higher education institutions of Pakistan. Fut. Bus. J. 2017, 3, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, J.; Pierce, J.; Zuñiga, J.; Esparragoza, I.; Maury, H. Sustainable manufacture of scalable product families based on modularity. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthimunye, K. D. T.; Daniels, F. M. Nurse educators’ challenges and corresponding measures to improve the academic performance, success and retention of undergraduate nursing students at a university in the Western Cape, South Africa. Indep. J. Teach. Learn. 2019, 14, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.; Bernacki, M. L.; Perera, H. N. A latent profile analysis of undergraduates’ achievement motivations and metacognitive behaviors, and their relations to achievement in science. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Y. Innovation in ideological and political education and personalized learning paths in the era of artificial intelligence. Int. J. New Dev. Educ. 2024, 6, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Wong, J.; Wasson, B.; Paas, F. Adaptive support for self-regulated learning in digital learning environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boppiniti, S. T. Data ethics in AI: Addressing challenges in machine learning and data governance for responsible data science. Int. Sci. J. Res. 2023, 5, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E. Moving from theory to practice in the design of web-based learning using a learning object approach. e-J. Instr. Sci. Technol.

- Chen, C. H. An adaptive scaffolding e-learning system for middle school students’ physics learning. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2014, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnawati, R. A. Effectiveness of blended learning with the flipped classroom model on Shochuukyuu Bunpou in 21th-century dynamics skill towards Japanese language education study program Muhammadiyah University Prof. Dr. Hamka. Int. J. Lang. Educ. Cult. Rev. 2020, 6, 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- Adewale, O. S.; Nıgerıa, A.; Ibam, E. O.; Alese, B. K. A web-based virtual classroom system model. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2012, 13, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Zein, A. Implementation of service oriented architecture in mobile applications to improve system flexibility, interoperability, and scalability. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. Eng. 2024, 2, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, V.; Mulholland, P.; Hlosta, M.; Farrell, T.; Herodotou, C.; Fernandez, M. Co-creating an equality diversity and inclusion learning analytics dashboard for addressing awarding gaps in higher education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55, 2058–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emborg, M. E. Nonhuman primate models of Parkinson's disease. ILAR J. 2007, 48, 339–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloria, A. M.; Uttal, L. Conceptual considerations in moving from face-to-face to online teaching. Int. J. E-Learn.

- Dominey, P.; Arbib, M.; Joseph, J. P. A model of corticostriatal plasticity for learning oculomotor associations and sequences. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1995, 7, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dopfer, K.; Foster, J.; Potts, J. Micro-meso-macro. J. Evol. Econ. 2004, 14, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. Teaching mathematics integrating intelligent tutoring systems: Investigating prospective teachers’ concerns and TPACK. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2022, 20, 1659–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A. R.; Freeman, S. A.; Grinstein, S.; Jaqaman, K. Multistep track segmentation and motion classification for transient mobility analysis. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahal, R. K. Management accounting and control system. NCC J. 2018, 3, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. A data driven educational decision support system. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2018, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitto, K.; Knight, S. Practical ethics for building learning analytics. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 50, 2855–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).