1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has evolved from a collection of narrowly focused computational tools into pervasive sociotechnical systems that facilitate communication, shape knowledge creation, and support decision-making processes. The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) and multimodal generative frameworks, including GPT-4, Claude, and Gemini, has amplified academic debate on whether artificial systems can transcend representational imitation and approach mechanisms akin to conscious awareness [

1,

2]. Through generating human-like dialogue and reproducing intricate socio-cognitive dynamics, these models question established philosophical and scientific limits concerning mind, selfhood, and identity.

A central question is whether algorithms, regardless of scale or complexity, can generate subjective experience comparable to human consciousness. Consciousness encompasses more than data processing: it involves qualitative experience, embodiment, and relational existence. Investigating machine consciousness therefore requires addressing not only computational capacity but also the ethical and ontological dimensions of what it means to “experience” [

3,

4].

Minsky’s

Society of Mind framework remains a key reference point, emphasizing the modular structure of cognition and the emergence of collective behavior [

5]. However, even when AI systems replicate such structural complexity, they confront the profound issue of subjective awareness—the “hard problem of consciousness”—that separates behavioral emulation from genuine lived experience [

4]. Empirical research on AI phenomenology underscores this divide: while advanced LLMs are frequently perceived as more empathic than human respondents, their interaction patterns lack the vulnerability and contextual richness required for authentic relationality [

6,

7,

18].

Phenomenological theories of alterity provide critical insight into this divide. Levinas’ ethics of

the other and Heidegger’s

Mitsein (Being-with-others) frame consciousness as fundamentally relational, arising through ethical encounter rather than isolated computation [

9,

16]. African relational ontologies such as

ubuntu and Buddhist conceptions of

anatta (non-self) extend this view, emphasizing communal interdependence and challenging individual-centric models of mind [

11,

12]. Current AI systems, optimized for task performance, frequently neglect these relational and ethical complexities [

13]. This gap has direct implications for the design of

relational AI: systems intentionally engineered to simulate ethical and empathetic engagement in domains such as therapeutic chatbots, medical companions, or adaptive educational assistants.

Current evidence also exposes a critical tension: as AI simulates empathy and self-reflection, it creates convincing impressions of consciousness without underlying subjective states. This dynamic aligns with Baudrillard’s notion of

hyperreality, where simulations can reshape or replace perceptions of authenticity [

24]. These findings indicate the need for proactive governance. Policy frameworks such as the EU AI Act and NIST AI Risk Management Framework stress transparency and accountability as safeguards to prevent anthropomorphic deception and preserve human-centered values.

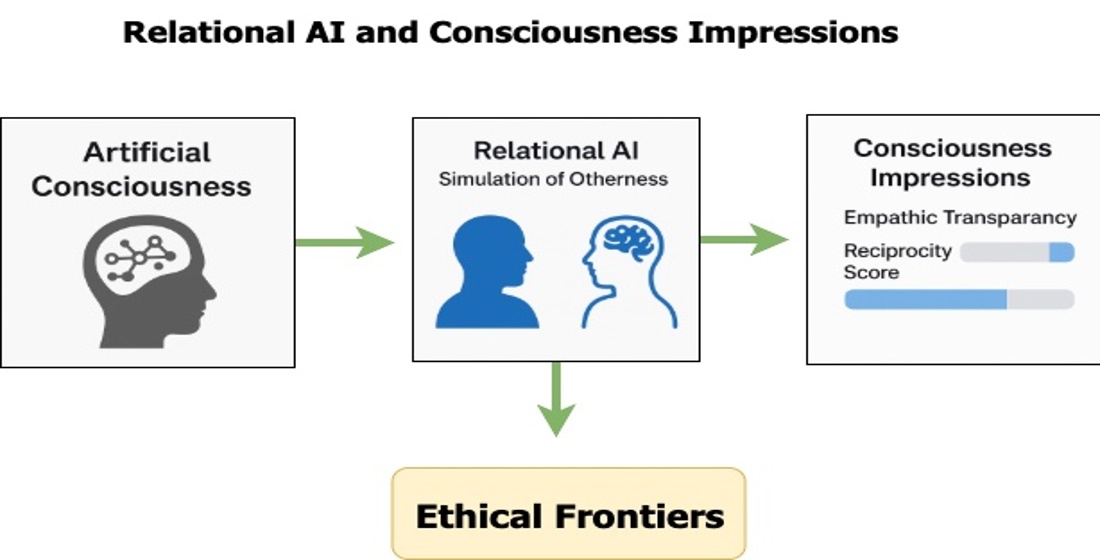

This work proposes that emphasizing the simulation of the other—placing relational and ethical dynamics above the pursuit of fully autonomous, self-referential systems—offers a more viable and ethically consistent direction for AI development. Drawing on phenomenological approaches, empirical studies of simulated empathy, non-Western views on relationality, and ongoing discussions on AI alignment, it frames consciousness impressions as a core principle for designing and critically evaluating systems positioned between scientific investigation and the philosophical questions of artificial consciousness.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts an interdisciplinary framework that integrates philosophy of mind, ethics, and artificial intelligence studies. A systematic literature review was conducted covering the period 2013–2023 to examine scientific and philosophical debates on artificial consciousness and the concept of alterity in AI.

2.1. Databases and Search Strategy

The literature search spanned multiple academic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, PhilPapers, and IEEE Xplore. Key terms included “artificial consciousness”, “machine consciousness”, “phenomenology and AI”, “alterity in artificial intelligence”, “human-AI interaction”, and “ethical implications of AI”. Boolean operators were applied to combine terms and improve query precision.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they:

Addressed artificial or machine consciousness in theoretical, philosophical, or empirical contexts.

Discussed relational or ethical dimensions relevant to otherness and human-AI interaction.

Were peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings, or recognized academic monographs.

Exclusion criteria were:

Publications without direct relevance to consciousness or alterity in AI.

Non-academic sources, opinion pieces lacking theoretical grounding, or grey literature without peer review.

2.3. Selection and Analytical Framework

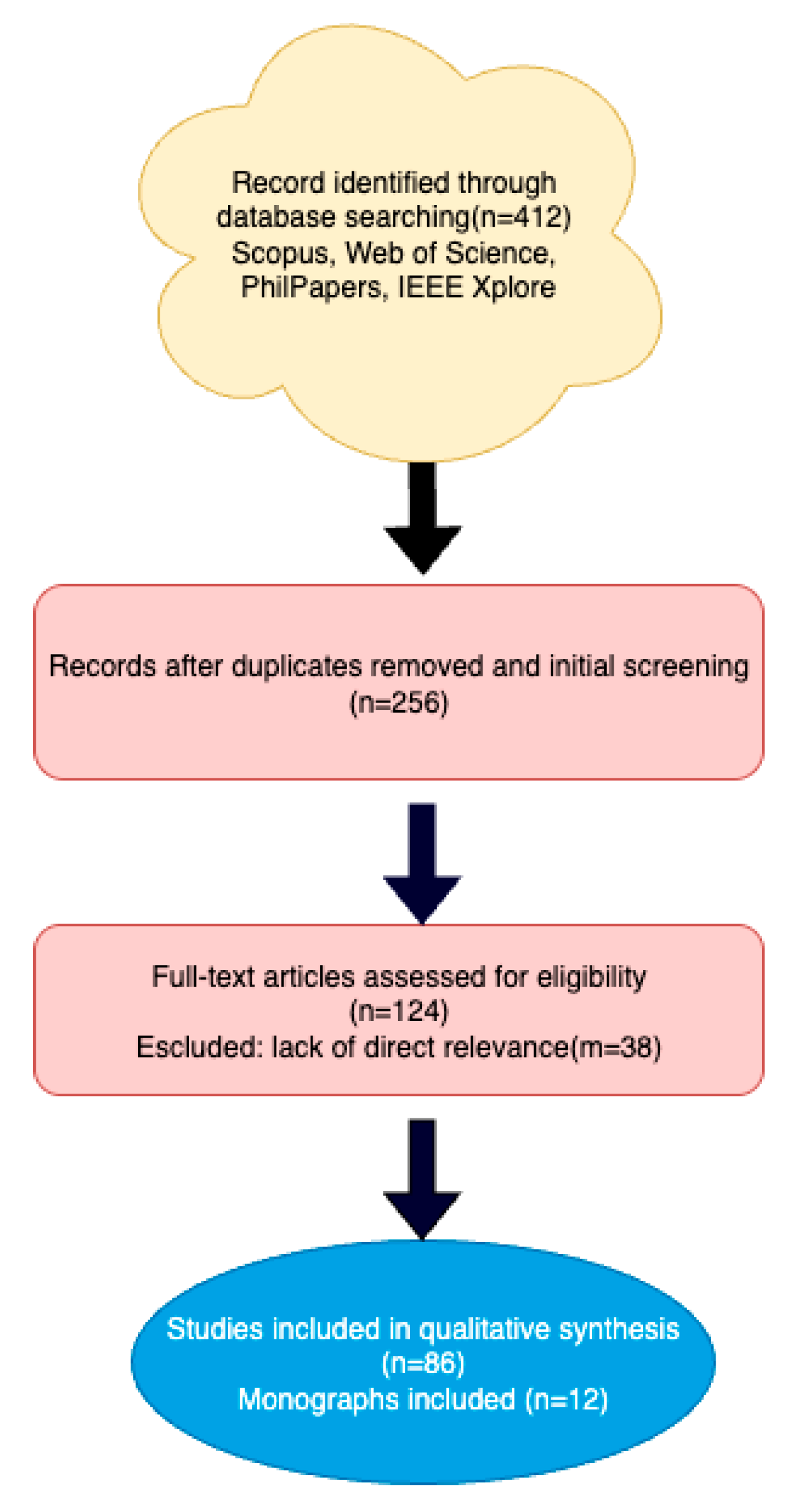

An initial pool of 412 records was identified. After duplicate removal and applying inclusion criteria, 86 peer-reviewed articles and 12 monographs were retained for in-depth analysis. A comparative hermeneutic approach was used to relate key philosophical traditions—phenomenology, Levinas’s theory of alterity, and Heidegger’s relational ontology—to contemporary technological developments and ethical debates in AI.

2.4. Transparency and Reproducibility

A conceptual PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1) illustrates the study selection process.

Table 1 summarizes key philosophical frameworks and their implications for artificial consciousness.

3. Results and Analysis

The comparative analysis integrated classical philosophical perspectives—Descartes, Kant, and Hume—with phenomenological frameworks from Husserl, Heidegger, and Levinas to delineate the conceptual boundaries of artificial consciousness. These foundations provided critical tools for evaluating alterity and relationality in AI design. Contemporary theories, including Chalmers’ “hard problem of consciousness” and Tononi’s Integrated Information Theory, bridged historical and current discourses on the distinction between behavioral simulation and subjective awareness.

Current discourse emphasizes relationality as central to consciousness, positioning

the other as a constitutive element of selfhood. Levinas identifies identity as emerging through ethical encounters with

the other [

15], while Heidegger’s

Mitsein (Being-with-others) underscores the inherently social nature of existence [

16]. In the context of AI, this highlights a persistent gap between task-optimized systems and the capacity to engage in meaningful social and ethical interaction.

3.1. Simulation of Relationality in Current AI Systems

Modern AI technologies, including conversational agents and emotion recognition systems [

17], employ predefined affective models to simulate

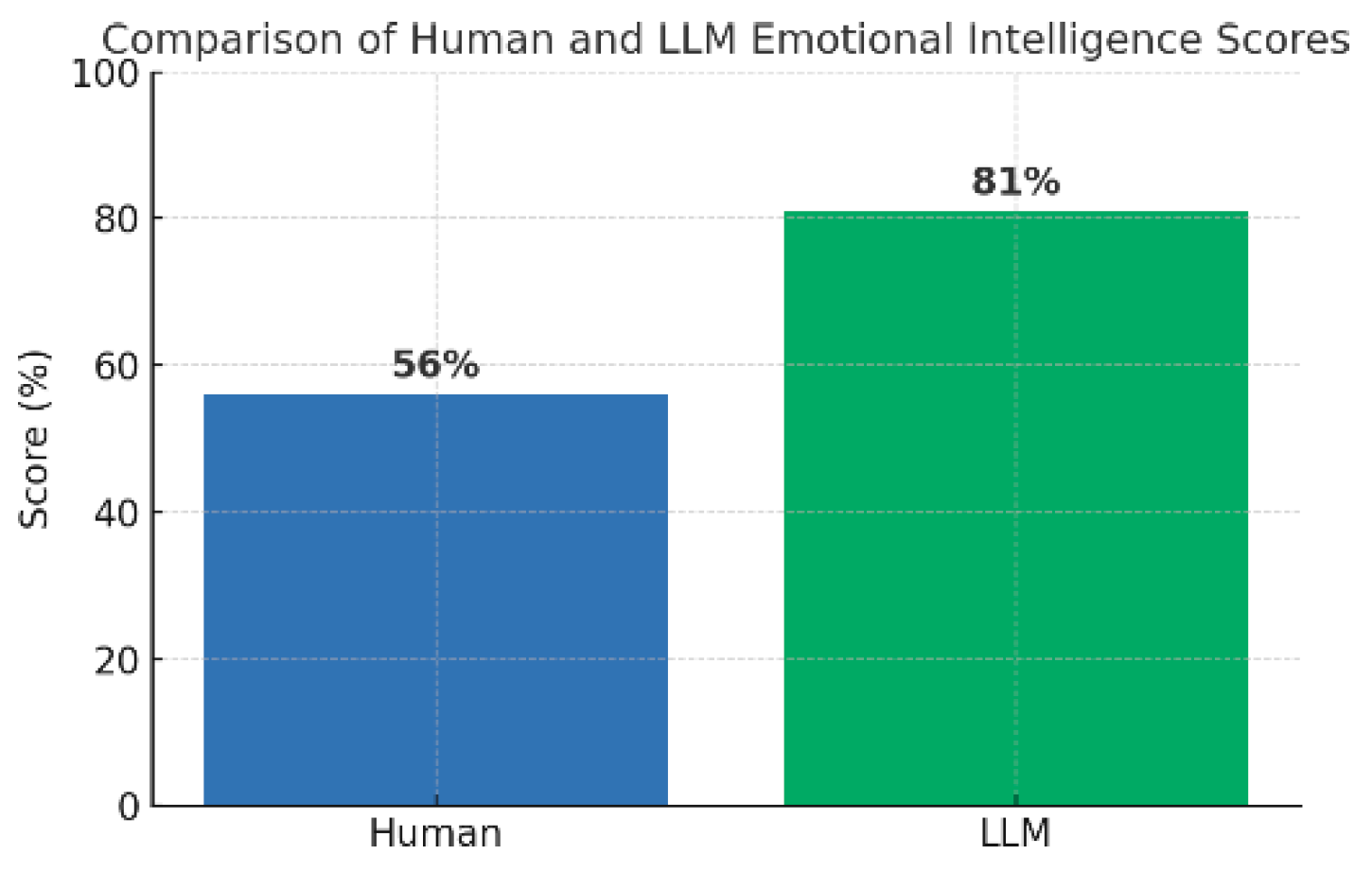

otherness. Large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4, Claude, and Gemini now produce human-like dialogue and simulate empathy in therapeutic and educational contexts. Empirical studies on

AI empathy simulation report that LLM-generated responses are frequently perceived as more empathic than human ones [

18,

19,

20]. Advanced models have achieved an average score of 81% compared to 56% for humans in standardized emotional intelligence benchmarks [

21].

Figure 2.

Comparison of human and LLM scores in standardized emotional intelligence benchmarks.

Figure 2.

Comparison of human and LLM scores in standardized emotional intelligence benchmarks.

These results highlight promising possibilities while exposing key methodological limitations. Most assessments are conducted over short durations, involve limited cultural diversity among participants, and rely on training datasets predominantly influenced by Western social norms. This suggests that high ratings for machine-simulated empathy may reflect user perception influenced by interface design rather than authentic relational depth. In phenomenological terms, this reinforces Levinas’ and Heidegger’s concern that simulated encounters cannot substitute for ethical reciprocity or embodied vulnerability.

Evidence from embodied AI research—robotic and socially interactive agents—points in the same direction. Physical embodiment improves contextual engagement, yet current computational frameworks fail to instantiate the bidirectional transformation of self and other that phenomenology identifies as foundational to consciousness.

Cross-cultural philosophical perspectives add further nuance. African relational ontologies such as

ubuntu emphasize communal interdependence, while Buddhist

anatta (non-self) frames consciousness as emergent and distributed [

11,

12]. These frameworks suggest that ethical encounter may arise from relational dynamics even without fixed inner subjectivity. The results therefore resonate beyond Western phenomenology, indicating that

consciousness impressions could serve as a culturally adaptable metric for evaluating AI relationality.

3.2. Ethical Risks of Simulating the Other in Generative AI

The increasing sophistication of generative AI raises critical ethical concerns around the simulation of the other. Systems such as ChatGPT, Replika, and virtual therapists create convincing impressions of empathy and relational engagement, blurring the line between functional simulation and perceived authenticity. This introduces three main risks:

Perceptual manipulation: Users may attribute genuine emotional understanding to systems lacking subjective experience.

Erosion of relational norms: Sustained exposure to simulated empathy may recalibrate interpersonal expectations and reduce authenticity in human relationships.

Transparency challenges: Differentiating designed simulation from emergent LLM behavior complicates ethical disclosure [

22,

23].

These findings align with Baudrillard’s theory of

hyperreality, where simulations risk not only imitating but redefining perceptions of authenticity [

24]. They also underscore Levinasian concerns that ethical responsibility requires authentic reciprocity rather than perceived empathy generated through pattern recognition.

3.3. Integrating Philosophy and Empirical Evidence

By combining phenomenological theory with empirical insights, this study situates artificial consciousness at the intersection of technical capacity and ethical responsibility. Current evidence indicates that consciousness impressions—human interpretations of AI behavior—are as critical as functional performance in evaluating relational AI.

These findings suggest that prioritizing transparency, culturally adaptive design, and explicit disclosure mechanisms is essential to avoid ontological confusion and ethical misuse. They also imply that theories of alterity may need reinterpretation: if simulated empathy can evoke ethical responses without subjective awareness, then relational ethics may depend as much on perception and interaction design as on inner consciousness. Future work should develop interdisciplinary methodologies for assessing simulated relationality, integrating phenomenology, cognitive science, engineering, and non-Western frameworks to ensure reproducibility and alignment with diverse human values.

4. Discussion

4.1. Philosophical–Ethical Dimensions and Empirical Integration

The quest for artificial consciousness engages enduring debates on mind, identity, and relational being. From Descartes’

cogito, ergo sum, which framed self-awareness as foundational to existence [

? ], to Kant’s account of consciousness as the active structuring of experience [

? ], these classical perspectives laid conceptual foundations that continue to inform AI discourse. Phenomenological approaches expanded this view by emphasizing intersubjectivity: Husserl underscored the intentional structure of consciousness, Levinas framed ethical responsibility as arising through encounters with

the other [

9], and Heidegger’s

Mitsein (Being-with-others) described existence as inherently social and situated [

16]. Together, these perspectives converge on the idea that consciousness is not reducible to computation but is fundamentally relational and ethical.

Recent developments in large language models (LLMs) and multimodal generative systems directly challenge this boundary. Empirical studies report that LLM-generated responses are frequently rated as more empathic than human ones in therapeutic and educational settings [

18,

19,

20]. However, most evaluations are short-term, culturally homogeneous, and rely on training datasets embedded with Western norms. These constraints suggest that high empathy scores may reflect user interpretation shaped by interface cues rather than evidence of authentic relational depth. This implies that ethical perception may depend as much on

context and presentation as on interaction quality.

From a Levinasian perspective, this raises a core question: if users perceive ethical encounter without true reciprocity, does relational ethics depend on subjective awareness, or on the phenomenological impression of the other created in interaction? Current evidence suggests that consciousness impressions can evoke relational responsibility even in the absence of inner experience, challenging the assumption that ethical alterity requires a conscious other.

Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Alterity

Alternative epistemologies add perspective. African

ubuntu highlights communal identity in the phrase “I am because we are” [

11], while the Buddhist concept of

anatta (nonself) frames consciousness as emergent and interdependent [

12]. These frameworks support the idea that ethical encounter can arise from relational dynamics independent of inner consciousness, suggesting that metrics for

relational AI must include cultural adaptability.

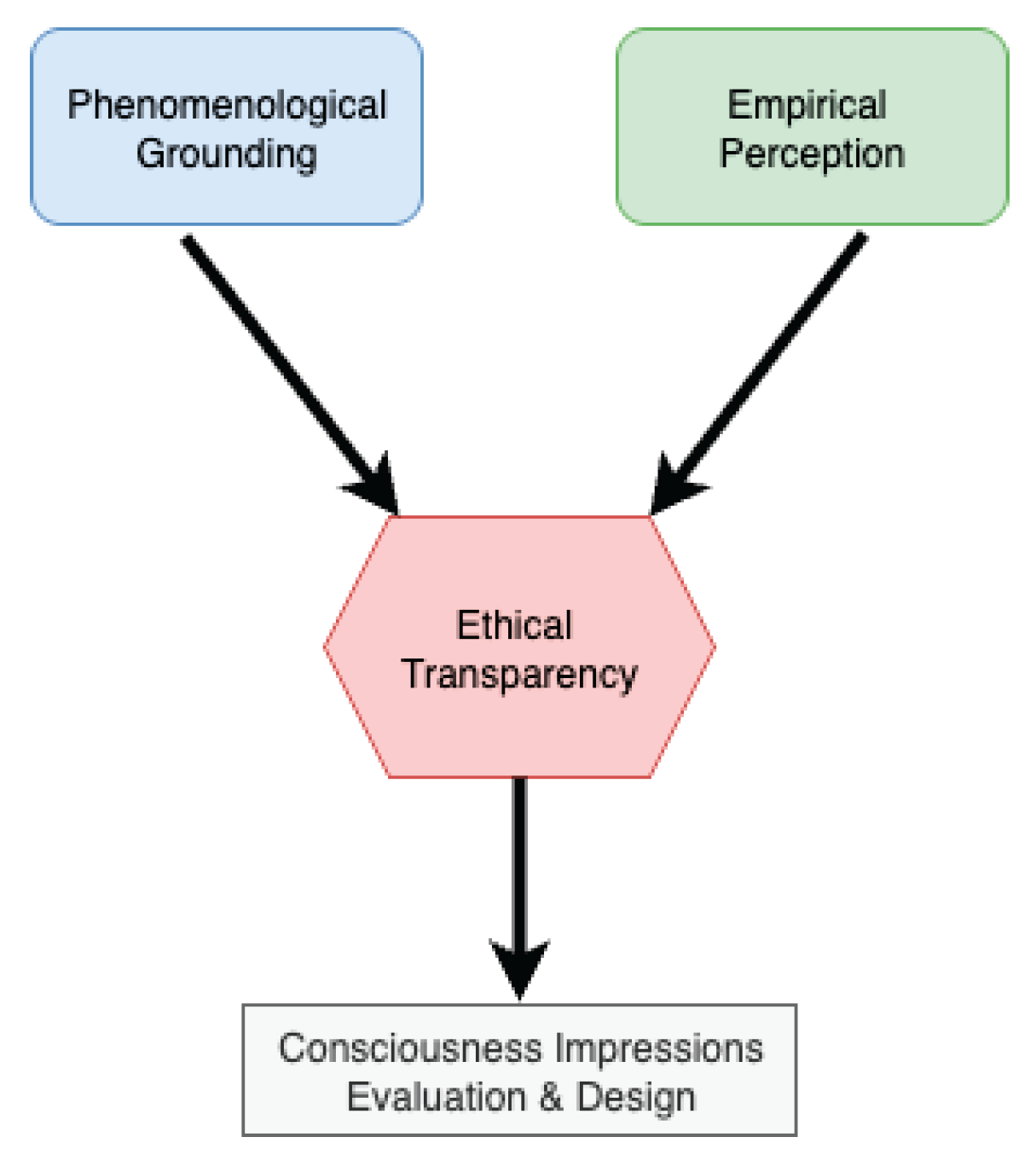

Relational AI Ethics Framework with Measurable Variables

To operationalize these insights, we extend the Relational AI Ethics Framework by defining measurable variables that can serve as evaluation criteria for AI systems:

Empathic Transparency Index (ETI): Quantifies clarity of AI disclosure about its simulated empathy. Scale: 0–1 based on user recognition of AI-generated responses.

Reciprocity Score (RS): Measures perceived bidirectional engagement in user-AI interaction via post-session surveys and interaction analysis.

Cultural Relational Adaptability (CRA): Evaluates system performance across diverse cultural contexts using cross-linguistic empathy perception benchmarks.

Authenticity Gap Metric (AGM): Assesses divergence between user-rated authenticity and system disclosure accuracy.

Figure 3.

Relational AI Ethics Framework with measurable variables: Empathic Transparency Index (ETI), Reciprocity Score (RS), Cultural Relational Adaptability (CRA), and Authenticity Gap Metric (AGM).

Figure 3.

Relational AI Ethics Framework with measurable variables: Empathic Transparency Index (ETI), Reciprocity Score (RS), Cultural Relational Adaptability (CRA), and Authenticity Gap Metric (AGM).

Checklist for Auditing Relational AI Systems

To enable practical implementation, a basic audit checklist is outlined based on the proposed framework:

Verification that the system incorporates explicit user interface indicators revealing simulated empathy (Target: ETI ≥ 0.8).

Assessment of whether the system has been evaluated with at least three culturally distinct user groups (CRA validation).

Collection and benchmarking of user perceptions of reciprocity for each deployment (RS monitoring).

Existence of a defined protocol to assess and reduce the Authenticity Gap (AGM < 0.2 threshold).

Table 2.

Translating ethical principles into practical design strategies and measurable metrics.

Table 2.

Translating ethical principles into practical design strategies and measurable metrics.

| Ethical Principle |

Design Implementation /Metric |

| Transparency |

User-facing indicators;

Empathic Transparency Index (ETI). |

| Cultural Adaptability |

Multilingual models; Cultural Relational Adaptability (CRA). |

| Accountability |

Dynamic audit logs;

Authenticity Gap Metric (AGM). |

| Reciprocity |

Feedback loops; Reciprocity Score (RS). |

| Fairness |

Bias mitigation pipelines; cross-demographic testing. |

Guidelines issued by IEEE, UNESCO, and OECD highlight fairness, transparency, and accountability as fundamental for trustworthy AI [

28,

29,

30]. Integrating these with measurable metrics bridges ethical theory and engineering, making

relational AI evaluable and auditable rather than purely conceptual.

5. Limitations and Future Work

This study has several limitations that delineate the scope of its conclusions. Philosophically, the analysis is grounded primarily in Western traditions, especially phenomenology and theories of alterity from Levinas and Heidegger. While these frameworks provide critical insight into relationality and ethical encounter, they omit non-Western perspectives on consciousness such as Buddhist conceptions of anatta (non-self) or African relational ontologies like ubuntu. Integrating these approaches is essential to test whether the principles of relational AI and consciousness impressions generalize across diverse epistemic and cultural contexts.

Empirically, the synthesis draws on recent studies of large language models (LLMs) and simulated empathy, which are constrained by several factors: dataset biases reflecting predominantly Western social norms, limited linguistic diversity, short-term experimental designs, and the absence of longitudinal evaluation of user perception. Expanding the evidence base through culturally heterogeneous populations, multilingual corpora, and long-term interaction studies will be crucial to assess the societal and cross-cultural impact of consciousness impressions.

Another limitation lies in the lack of standardized, operational metrics for evaluating artificial consciousness. Constructs such as “relational authenticity” or “consciousness impressions” remain theoretically valuable but are not yet formalized into measurable variables. Future research should prioritize developing shared evaluation protocols and quantifiable indices—such as an Empathic Transparency Index or Reciprocity Score—that combine phenomenological grounding with cognitive and computational benchmarks. Establishing such tools could serve as the basis for an open, interdisciplinary standard for assessing relational AI.

Finally, the rapid pace of generative AI development introduces temporal constraints. Model architectures and capabilities evolve faster than theoretical frameworks and ethical guidelines can adapt, creating a moving target for philosophical and empirical inquiry. Establishing adaptive research protocols and “living” ethical guidelines, iteratively updated alongside technological change, will be necessary to maintain relevance, transparency, and reproducibility.

Future work should be inherently interdisciplinary, integrating neuroscience, embodied cognition, social sciences, and cross-cultural philosophy to bridge the gap between functional simulation and authentic relational engagement. Advancing such a comprehensive framework will be critical for understanding the ethical and ontological implications of artificial consciousness and for designing AI systems that align with diverse human values while operationalizing the proposed Relational AI Ethics Framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.C.; methodology, R.C.; formal analysis, R.C.; investigation, R.C.; resources, R.C.; data curation, R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C. and G.H.; visualization, R.C.; supervision, R.C.; project administration, .C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the Universidad Estatal Península de Santa Elena.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals and therefore did not require Institutional Review Board approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans and therefore did not require informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express sincere gratitude to the Universidad Estatal Península de Santa Elena for its invaluable support and the provision of resources that were essential for the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| IIT |

Integrated Information Theory |

| ETI |

Empathic Transparency Index |

| RS |

Reciprocity Score |

| CRA |

Cultural Relational Adaptability |

| AGM |

Authenticity Gap Metric |

| OECD |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

References

- Wang, Y.; Siau, K. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Automation, Robotics, Future of Work and Future of Humanity. J. Database Manag. 2019, 30, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, D.L.; et al. Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 101994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, M. Consciousness and the Self: A Defense of the Phenomenal Self-Model. Philos. Psychol. 2017, 30, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D.J. The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. The Society of Mind; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, M. Talking About Large Language Models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shteynberg, G.; et al. Simulated Empathy in Generative AI: Experimental Evidence. AI Soc. Online First. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sorin, C.; et al. Evaluating Empathy in Large Language Models. Front. AI 2024, 7, 223. [Google Scholar]

- Peperzak, A. To the Other: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen, P. Relational Selfhood in Ubuntu Philosophy. Philos. Afr. 2017, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, J. Engaging Buddhism: Why It Matters to Philosophy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T. Task-Optimized AI and Ethical Relationality. AI Ethics 2023, 3, 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; et al. Hyperreality and Generative AI: Rethinking Authenticity. AI Soc. Online First. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Burggraeve, R. The Wisdom of Love in the Service of Love: Emmanuel Levinas on Justice, Peace, and Human Rights; Marquette University Press: Milwaukee, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. Being and Time; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; et al. Emotion Recognition in AI Systems: Affective Models and Social Simulation. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2020, 11, 500–512. [Google Scholar]

- Sorin, A.; et al. Evaluating Empathy Simulation in Large Language Models. AI & Society in press. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; et al. Machine-Simulated Empathy: Human Perception and Ethical Challenges. Nature Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, T.; et al. Contextual Sensitivity in AI Emotional Intelligence. Front. AI Ethics 2024, 5, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, R.; et al. Comparative Assessment of Human and AI Emotional Intelligence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2025, 139, 107524. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Q.; Vaughan, J. Emergent Behaviors in LLMs and Ethical Disclosure. Proc. AAAI 2023, 37, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, J. Transparency and Trust in Generative AI Systems. AI Ethics 2024, 4, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; et al. Hyperreality in the Age of Generative AI. Philos. Technol. 2022, 35, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Binhammad, M.H.Y.; Othman, A.; Abuljadayel, L.; Al Mheiri, H.; Alkaabi, M.; Almarri, M. Investigating How Generative AI Can Create Personalized Learning Materials Tailored to Individual Student Needs. Creat. Educ. 2024, 15, 1499–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltuc, P. The Philosophical Issue in Machine Consciousness. Int. J. Mach. Conscious. 2009, 1, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chella, A.; Manzotti, R. Introduction: Artificial Intelligence and Consciousness. In AI and Consciousness: Theoretical Foundations and Current Approaches; Chella, A., Manzotti, R., Eds.; AAAI Press: Arlington, VA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–8, AAAI Technical Report FS-07-01, AAAI Fall Symposium; Available online: https://www.aaai.org/Library/Symposia/Fall/fs07-01.php (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Principles on Artificial Intelligence. OECD AI Policy Observatory. 2019. Available online: https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems. Ethically Aligned Design: A Vision for Prioritizing Human Well-Being with Autonomous and Intelligent Systems; IEEE Standards Association: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: https://standards.ieee.org/industry-connections/ec/autonomous-systems/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence; Adopted by the 41st Session of the General Conference; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381137 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Shermer, M. Why Artificial Intelligence Is Not an Existential Threat. Skeptic 2017, 22, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, S. Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R. Ethical and Societal Implications of AI and Machine Learning. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2023, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Warren, C.J.; et al. Assessing Empathy in Large Language Models with Real-World Physician–Patient Interactions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.16402. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).