1. Introduction

Additive Manufacturing (AM) has emerged as a transformative approach in modern manufacturing due to its ability to fabricate geometrically complex components with reduced material waste and customization across industries [

1,

2]. Among the various metal AM techniques, wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) has gained significant attention for its capability to produce large-scale metallic structures using an arc-welding-based deposition mechanism with comparatively low operational cost [

3,

4]. WAAM is particularly suited for structural applications in sectors like maritime engineering, defence, and aerospace due to its high deposition rate and compatibility with widely available wire feedstock [

5,

6,

7]. However, the process involves complex thermal-fluid relations, including abrupt thermal gradients, dynamic molten pool behavior, and arc-induced disturbance, which contribute to unpredictable variations in bead geometry and microstructural inhomogeneity [

8]. These complexities require the deployment of advanced monitoring and control mechanisms to ensure geometric consistency, integrity, and overall process stability [

9]. Addressing these challenges requires sensor-driven and data-centric strategies that can interpret high-dimensional and time-dependent process signatures in real-time and across diverse operational rules.

To address the inherent complexity of WAAM, recent developments in process monitoring have increasingly favored data-driven methodologies that utilize real-time sensor streams to infer thermal, geometric, and electrical process states [

10]. These monitoring systems integrate high-frequency process signatures, producing asynchronous and high-dimensional datasets that are difficult to interpret through conventional rule-based methods [

11]. Machine learning, particularly deep architectures such as convolutional and recurrent neural networks, has demonstrated the ability to learn nonlinear correlations and to detect subtle anomalies that precede physical defects from these heterogeneous signals [

12,

13]. However, implementing these models through centralized learning paradigms dictates the pooling of raw process data from different WAAM stations, which raises critical concerns around intellectual property exposure, operational confidentiality, and compliance with industrial data governance policies [

14]. Moreover, process parameter distributions and sensor modalities differ significantly across WAAM installations, resulting in highly non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data that violates the assumptions of uniform training routines [

15]. These constraints need a distributed and privacy-preserving learning framework capable of maintaining both local customization and global generalization.

Federated Learning (FL) has emerged as a decentralized machine learning paradigm that enables multiple clients to collaboratively train a shared model without exposing their raw local datasets [

16]. In a typical FL workflow, each client performs localized training on its process data and transmits model weight updates or gradients to a central server, which then performs global aggregation while maintaining data privacy [

17]. This makes FL particularly well-suited for industrial environments, such as WAAM, where different workstations operate under distinct process dynamics but share the same underlying goal of real-time anomaly detection or quality assurance. Furthermore, FL architectures are inherently capable of addressing statistical heterogeneity across clients by supporting personalized models and employing aggregation strategies, which improve generalization across non-IID conditions [

18]. Importantly, since FL retains sensitive process information in local computational nodes, it aligns with the stringent data governance requirements of manufacturing ecosystems [

19]. Despite these benefits, the application of FL to WAAM-specific anomaly detection remains largely unaddressed, especially in contexts involving encrypted visual-signal fusion and process-aware client specialization.

While FL has gained attention in SM for applications such as predictive maintenance, fault classification, and process health monitoring in domains like laser powder bed fusion or injection molding, its potential in WAAM systems remains largely unexplored [

20,

21]. In particular, to our knowledge, no existing study has implemented a federated architecture designed explicitly for WAAM, which presents distinct challenges due to its high deposition rates and varied sensor configurations. Moreover, current FL implementations often focus on unimodal inputs and do not accommodate the secure fusion of electrical signatures, positional telemetry, and geometric features extracted from vision systems under a unified learning framework. These approaches typically assume trusted aggregators and overlook the risks posed by adversarial updates or tampered communications, limiting their applicability in sensitive industrial settings. Aforementioned critical gaps motivate the need for an FL system that is both WAAM-specific and resilient, enabling secure, multi-source anomaly detection across distributed process units.

To this extent, this study proposes an FL-based architecture for secure and distributed anomaly detection in WAAM. The architecture introduces client-specific models trained on process signals such as current, voltage, speed, position, and arc-related geometry, which are securely embedded into high dynamic range (HDR) weld images using reversible data hiding. It integrates local model customization with centralized aggregation strategies, including FedAvg, FedProx, and FedPer, to accommodate statistical heterogeneity across WAAM units. The proposed architecture is validated through a multi-client simulation framework that emulates eight distributed cells under replicated non-IID conditions. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents a review of FL in SM, AM, and secure communication;

Section 3 outlines the proposed framework with secure transmission;

Section 4 details the system-level deployment and proof of concept;

Section 5 analyzes the experimental results and compares aggregation strategies; and

Section 6 concludes the study and suggests future research directions.

2. Related Works

In this section, we detail some recent literature concerning FL, where we investigate FL based on additive manufacturing in particular and SM in general. FL is also explored for its security and data encryption, and significant research gaps are outlined.

2.1. Federated Learning in Additive Manufacturing

FL has recently been explored in the context of AM due to its ability to enable collaborative model training across multiple sites without sharing sensitive data. This decentralized approach is particularly beneficial for AM, where diverse datasets are often distributed across various organizations, each with unique process parameters and machine settings. For instance, Mehta et al. implemented an FL-based semantic segmentation approach using a U-Net architecture for defect detection in laser powder bed fusion processes. Their method demonstrates that FL achieves defect detection performance comparable to centralized learning while preserving data privacy and significantly outperforms individual learning, with improvements seen from data diversity and transfer learning for generalizability [

22].

Moreover, Shi et al. developed a knowledge distillation-based information sharing (KD-IS) framework that enhances monitoring performance for data-poor units in decentralized manufacturing by leveraging distilled knowledge from data-rich units. Their method achieved comparable accuracy and F-score to models trained with six times more data, while reducing training time by 25% and effectively preserving data privacy [

23]. On the other hand, Russell et al. detailed an approach combining Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) with Barlow Twins and FL to improve fault detection in manufacturing. Their results show that integrating FL boosts accuracy from 67.6% to 73.7% for supervised models and from 82.4% to 83.7% for SSL models, demonstrating enhanced generalization and fault discriminability in decentralized settings [

24].

The studies have applied FL to additive manufacturing processes, particularly in laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), fused deposition modeling (FDM), and extrusion-based setups. These works typically explore quality prediction, thermal monitoring, or control optimization while preserving data privacy across distributed manufacturing units. However, none of these implementations extend to WAAM, which operates under fundamentally different physical conditions involving high-temperature electric arcs, dynamic melt pool behavior, and continuously evolving deposition geometry. Moreover, the existing frameworks often rely on single-channel data inputs such as force feedback or thermal signatures, whereas WAAM requires the integration of multiple process parameters, including voltage, current, wire feed rate, arc length, speed, and bead geometry. These parameters vary in temporal resolution, demanding a more advanced learning approach. In addition, current federated models assume uniform architectures across clients and do not support local personalization, making them unsuitable for systems where each client observes different signal domains.

2.2. Federated Learning in Smart Manufacturing

FL plays a critical role in enhancing predictive maintenance, anomaly detection, and process optimization while maintaining data security. The nature of SM systems [

25], which often involve interconnected devices and sensors across multiple locations, makes FL an ideal solution for decentralized data analysis and model training.

For example, at a smart factory/enterprise level, Aggour et al. propose a federated multimodal Big Data storage and analytics platform that integrates diverse datasets from the additive manufacturing lifecycle, including material properties, design models, process parameters, sensor data, and inspection results, enabling scalable, unified access for advanced analytics and visualization to optimize manufacturing processes and accelerate technology maturation [

26]. Then again, Huong et al. proposed FedeX, an FL-based explainable anomaly detection architecture for industrial control systems, which integrates Variational Autoencoders, Support Vector Data Description, and Explainable AI. FedeX achieves exceptional performance with up to 1 Recall and 0.9857 F1-score on SWaT data, outperforms 14 existing methods, and is both fast and lightweight for real-time edge deployment [

27]. Also, Dib et al. developed an FL methodology to predict defects in sheet metal forming by training machine learning models locally on client data and aggregating model weights using federated averaging, achieving similar accuracy to centralized neural networks, demonstrating its reliability and potential for preserving data privacy while enhancing collaboration in SM environments [

28]. Chen et al. implemented a federated Markov chain Monte Carlo method with delayed rejection (FMCMC-DR) for digital twin-assisted federated analytics, achieving superior global distribution estimation with 50% and 95% contour accuracy and faster convergence compared to the Metropolis-Hastings and random walk MCMC algorithms, enhancing distributed data privacy and resource utilization in SM [

29].

Moreover, for, IIoT implementation, Kanagavelu et al. proposed a Two-Phase MPC-enabled FL framework that reduces communication costs and enhances scalability by electing a committee for privacy-preserving model aggregation, integrated into an IIoT platform for SM, demonstrating superior model accuracy and execution efficiency compared to traditional peer-to-peer frameworks [

30]. In addition, Gao et al. detailed RaFed, a resource allocation scheme for FL in IIoT systems, which uses a heuristic algorithm to reduce training latency by 29.9% compared to state-of-the-art methods, achieving a balance between interference and convergence time through optimal device and resource allocation in static wireless networks [

31].

Furthermore, applications in Industry 4.0 are demonstrated by Brik et al. developed a federated deep learning-based monitoring tool that predicts disruptions due to resource localization errors in real-time using Fog computing, achieving low latency, high prediction accuracy, and efficient task rescheduling via Tabu search, outperforming traditional methods in terms of QoS, total tardiness, and makespan [

32]. Similarly, Kusiak et al. proposed the XRule algorithm for generating user-defined explicit rules and introduced federated explainable AI (fXAI) to enhance model transparency and insight. Their approach allows for user control over rule characteristics and leverages fXAI to discover new model parameters and insights, supported by numerical examples and industrial applications [

33]. Likewise, Putra et al. detailed a FL-enabled digital twin architecture for smart additive manufacturing, particularly 3D printing, using a CNN-based model for fault detection. The model achieved an 8% increase in accuracy compared to other deep learning models while maintaining low training times, and demonstrated low latency, averaging 1026.16 ms between the physical printer and the digital twin platform [

34]. Additionally, Verma et al. detailed a FL-enabled deep intrusion detection framework for SM, utilizing a hybrid CNN+LSTM+MLP model for detecting cyber threats. The framework achieved high accuracy (up to 99.447%) and ensured data privacy using Paillier encryption for secure communication, outperforming other state-of-the-art methods while addressing FL-based attack concerns [

35].

The federated approach also included by Sun et al. implemented the Sustainable Production concerned with External Demands (SP-ED) method, integrating FL and blockchain to enhance energy production and distribution. Their approach achieves an 11.48% improvement in sustainability, 14.65% better flaw detection, and reductions in modifications and detection time, compared to DDSIM, demonstrating effective validation and optimization of energy supply-demand processes [

36]. Yang et al. developed a client selection method for FL that uses model parameter variations and graph theory to filter participants, reducing the impact of data heterogeneity. Their approach improved accuracy by 0.93% to 2.65% compared to baseline methods and mitigated the effects of heterogeneity, demonstrating enhanced training efficiency in SM scenarios [

37]. Zhang et al. developed DetectPMFL, a privacy-preserving FL approach that uses Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song homomorphic encryption to protect data and a detection method to handle unreliable agents. Evaluated on F-MNIST and CASE WESTERN datasets, DetectPMFL shows superior robustness and accuracy compared to traditional methods, with improved performance in the presence of unreliable agents [

38].

Discussion above showed, FL being applied in various SM systems to support decentralized fault detection, equipment health monitoring, and distributed control optimization. While these frameworks offer privacy-preserving analytics across factory networks, they often rely on generic architectures that do not incorporate domain-specific process behaviors. Additionally, most implementations do not analyze round-wise convergence metrics like global loss trends or client divergence, making it difficult to evaluate training stability during deployment. Aggregation strategies also remain static, ignoring variability in process conditions, signal quality, or operational complexity across clients. This limits the adaptability of the global model to high-variance systems such as WAAM.

2.3. Federated Learning in Secure Comminucation

Security is a critical concern in FL, especially when applied in industrial settings like AM and SM, where data privacy and integrity are paramount. FL’s decentralized nature introduces unique challenges and opportunities in ensuring secure model training and data protection. Such as, Ranathunga et al. developed a Blockchain-based decentralized FL framework with a hierarchical network of aggregators to handle low-quality model updates, ensuring security through additive homomorphic encryption and off-chain credibility verification using trusted execution environments, thus minimizing convergence time and latency, and maximizing accuracy and fairness across predictive maintenance and product inspection use cases [

39]. Again, Kuo et al. developed a privacy-preserving FL framework using Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) to perform computations on encrypted data, ensuring data privacy across segregated data ownership scenarios in SM. Their approach demonstrates superior performance in protecting against cyber-attacks while maintaining predictive model accuracy, as validated through real-world case studies [

40].

In addition, Li et al. detailed a privacy-preserving and Byzantine-robust FL scheme (PBFL) designed for Industry 4.0, leveraging agglomerative hierarchical clustering for robust aggregation and 2-party computation (2PC) protocols to enhance security and efficiency. Their approach achieves significant runtime reductions while maintaining accuracy, even with up to 49% malicious participants, ensuring effective protection against Byzantine attacks [

41]. Zhang et al. proposed a joint optimization framework for FL in industrial internet of things (IIoT) systems, balancing learning speed and cost by optimizing edge association, resource allocation, and transmit power. Their method, which involves decomposing the problem into three subproblems and using an alternating optimization algorithm, demonstrates improved learning performance and efficiency, effectively managing the tradeoff between speed and cost [

42].

Secure FL, as deliberated above, has been widely adopted in domains where data privacy is critical, including healthcare diagnostics, industrial IoT, and sensor-based monitoring. These systems commonly rely on encryption protocols, differential privacy, or trusted execution environments to protect information during model transmission and aggregation. However, existing methods rarely incorporate embedded security mechanisms such as reversible data hiding or image-based parameter encoding into the training pipeline itself. This limits their ability to verify integrity or support tamper-evident learning in sensitive industrial environments. Furthermore, most aggregation strategies assume idealized or balanced data distributions and are not resilient to adversarial updates that can arise under non-IID conditions typical in manufacturing. Without mechanisms like outlier suppression or similarity-based filtering, a single corrupted client can distort the global model. Additionally, current frameworks depend heavily on trusted aggregators and lack tamper-proof audit trails to verify the source and structure of incoming updates.

3. Proposed Methodology

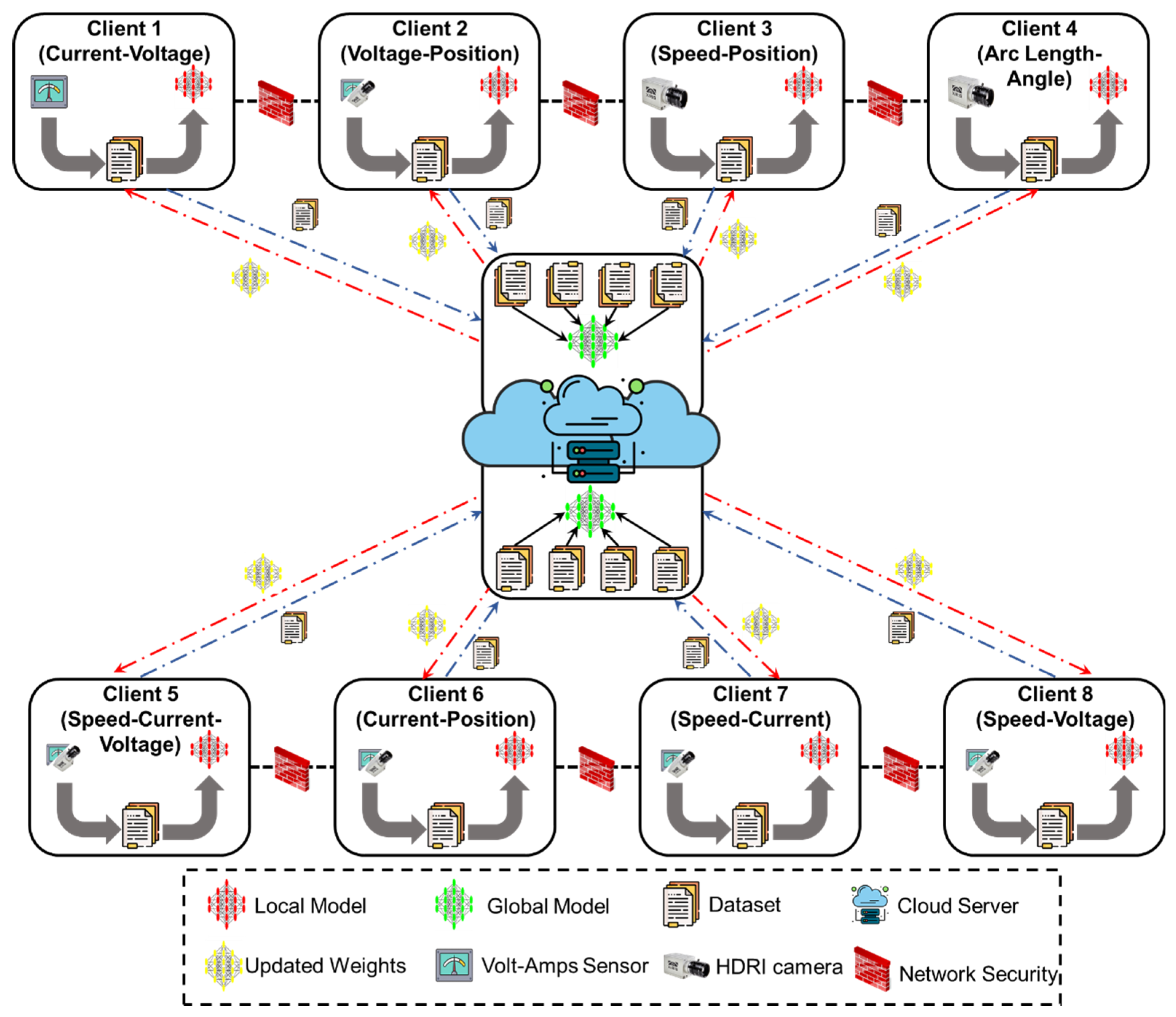

In order to address the limitation in the existing literature, the proposed methodology is designed to meet the critical need for secure learning across distributed WAAM setups, where each unit operates under unique conditions and generates heterogeneous process data. These datasets, which include time-dependent electrical signals, geometrical bead representations, and high-frame-rate visual sequences, cannot be pooled due to confidentiality and data ownership constraints. Therefore, this architecture adopts an FL framework that allows each WAAM client to independently train local models using its own process data while contributing to a shared anomaly detection model through periodic encrypted updates. The approach ensures that no raw data leaves the local boundary and that every site maintains control over its data assets. As shown in

Figure 1, the architecture initiates with individual data acquisition and training at the client nodes, followed by secure transmission of encoded model parameters, iterative model fusion under privacy-preserving protocols, and redistribution of the aggregated model for continued local refinement.

Local Data Collection and Preprocessing: Each WAAM client acquires structured and unstructured process data, which are filtered, normalized, and aligned temporally to construct feature matrices suitable for model training.

Local Model Training: Clients train sensor-specific models on preprocessed data to learn localized anomaly patterns without transmitting raw information externally.

Model Aggregation via FL: Encrypted local model parameters are securely transmitted and aggregated into a global model using privacy-preserving fusion techniques.

Global Model Update: The aggregated model updates are redistributed to clients, enabling them to enhance their local inference capabilities based on collective knowledge.

Iteration and Model Convergence: The training-aggregation-update cycle repeats multiple times until the model achieves convergence across all validation criteria.

Security and Privacy Mechanisms: A dual-layered protection scheme combining reversible encryption and differential privacy ensures confidentiality and resistance to inference attacks.

Model Deployment and Inference: Once converged, the global model is deployed locally at each client for real-time anomaly detection and process monitoring.

The architectural design starts at the client level, where each WAAM unit functions autonomously as an isolated training node equipped with domain-specific sensing equipment. Depending on the physical configuration and instrumentation, clients acquire distinct classes of data, ranging from high-frequency current-voltage signals and travel speed signals to HDR imaging for bead geometry and arc characterization. These sources present variations not only in temporal samples and statistical structure but also in signal integrity and failure patterns. To accommodate this diversity, each client implements a tailored data curation pipeline involving time-based resampling, filtering, and segmentation. For time-series data, statistical features such as root mean square, kurtosis, and spectral entropy are computed over sliding windows. At the same time, image streams undergo contrast enhancement, region-of-interest isolation, and dimensionality reduction via pretrained encoders. The resulting feature matrices are fed into neural network architectures tailored to the data type, including convolutional encoders for visual patterns, long short-term memory (LSTM) blocks, or gated recurrent unit (GRU) blocks for sequential signals. This design ensures each client captures anomalies specific to its operational domain while preserving heterogeneity within the federation.

Following local training, each client generates model parameter updates encoded in a secure format to ensure privacy during transmission. Before dispatch, the gradient tensors undergo differential excitation using calibrated Laplacian noise, hiding sensitive training signatures while retaining representational fidelity. These excited tensors are then embedded using reversible data hiding techniques, which allow precise restoration of the original model update post-decoding without information loss. Once encoded, the parameter sets are exchanged through a secure channel using integrity-preserving communication protocols. At the aggregation layer, the encrypted updates are decoded, verified for consistency, and fused into a global model through federated averaging weighted by client-specific data contributions. This aggregated model is redistributed to the clients, serving as a refined beginning for subsequent local updates. The process iterates until convergence is detected through global stability in loss metrics and local validation scores. Such iterative synchronization across non-identical clients requires a rigorous and sensor-aware data processing framework at the client level, which is presented in detail in the following.

3.1. Multi-Source Data Collection and Processing

The WAAM process generates diverse sensor data, including high-frequency current and voltage signals, slower travel speed and wire feed rate readings, and vision-based bead and arc imagery, that differ in sampling rates, resolution, and statistical properties. To harmonize this heterogeneous data for federated training, each client builds a custom preprocessing pipeline. Structured signals are filtered, normalized, and resampled onto a unified temporal grid, then segmented into overlapping windows from which descriptive features (e.g., root mean square (RMS), kurtosis, spectral entropy) are extracted. These features capture steady-state behavior and transient anomalies, ensuring that input data fed into local models is consistent, representative, and aligned in time.

For clients with visual data, image frames are processed using grayscale conversion, contrast enhancement, and region-of-interest isolation to highlight weld features, such as bead width and arc boundaries. Pretrained convolutional encoders then extract fixed-length feature vectors, which are synchronized with structured sensor data via timestamp matching. The resulting fused feature matrices are semantically rich and temporally coherent, enabling effective anomaly learning. This dual-channel preparation, combining signal-based and vision-based approaches, ensures that each client independently constructs a reliable training set tailored to its sensor configuration, laying the groundwork for stable federated learning across non-identical WAAM environments.

3.2. Federated Secure Channel

Once local training is complete, each WAAM client must transmit its model updates to the federation without exposing sensitive information. However, sharing model parameters introduces several integrity risks that can compromise the entire learning process. One major concern is model inversion, where adversaries attempt to reconstruct the client’s training data by analyzing gradients. Gradient leakage is also a threat, particularly when signals like current or voltage are sparse and contain identifiable operational patterns. Moreover, adversarial clients may inject poisoned updates that degrade the global model or distort anomaly boundaries. These vulnerabilities are exacerbated by the uneven data distributions across WAAM sites, which increase the likelihood that unique client patterns become identifiable during aggregation. Therefore, the transmission pipeline must protect against unauthorized access, preserve the fidelity of model updates, and prevent any attempt to infer client data or interfere with training. To meet these challenges, the system employs a dual-layer security framework that combines reversible encryption and privacy-preserving perturbation. This ensures that model updates remain protected during transfer and that any tampering or manipulation can be detected and corrected before aggregation. These safeguards are critical in maintaining trust and consistency throughout the FL process.

To ensure secure and reversible transmission of model updates, each client applies a two-stage encoding process that combines differential privacy and reversible data hiding. The first stage involves agitating the local model gradients or weight tensors using calibrated Laplacian noise, which masks the contribution of individual training samples. This step provides formal privacy guarantees by ensuring that even if an update is intercepted, it cannot be traced back to specific input patterns or process states. In the second stage, the noise-added tensors are embedded into image-like structures using reversible data-hiding techniques. These methods encode the encrypted tensors into the least significant bits of pixel matrices, allowing for the full restoration of the original model parameters after decoding without any loss of precision. This is especially useful for maintaining the floating-point resolution required for aggregation. Additionally, a watermarking signature is embedded within the payload as a tamper-detection mechanism, which enables clients and aggregators to verify the authenticity of received updates. The advantage of this approach is that it enables high-capacity, low-distortion embedding that is both reversible and secure. As a result, the shared updates are protected from both passive inference and active manipulation, allowing only valid and untampered updates to enter the aggregation cycle.

Beyond protecting the content of model updates, the transmission setup must also ensure that communication occurs through secure and verifiable channels. To enforce this, each client operates under a network security framework that monitors outbound and inbound parameter flows for unusual patterns. Packet inspection routines are configured to detect anomalous payload sizes, irregular transmission intervals, or unauthorized access attempts, all of which may indicate tampering or injection attacks. Each outgoing model update is tagged with a cryptographic signature and a timestamp to enable verification upon arrival. These signatures are checked before any aggregation occurs, ensuring that only authenticated updates contribute to the global model. In addition, all update histories are logged in an append-only local registry, which serves as a trail in case of disputed behavior or rollback attempts. This logging also supports traceability for update provenance and client accountability. Together, the layered protection scheme, which encompasses noise-based privacy, reversible embedding, and network validation, ensures that the federated system can operate reliably across distributed WAAM environments. With secure exchange mechanisms in place, the next challenge lies in tailoring local models that can effectively learn from the prepared data streams while remaining compatible with the global aggregation process.

3.3. Local Client Model Development

Each WAAM client deals with unique data modalities, such as high-frequency time-series signals (e.g., current, voltage, speed) or image-based features (e.g., bead geometry, arc profiles), which demand tailored neural network models. Clients with visual data use convolutional encoders to extract spatial patterns, while those processing sequential signals rely on LSTM or GRU architectures to capture temporal dependencies. For clients handling both data types, feature vectors are fused and passed through fully connected layers. To ensure stable training and prevent overfitting, standard techniques such as dropout, batch normalization, and gradient clipping are applied. Validation is monitored in real time to stop training once loss and accuracy stabilize. This design guarantees that models are lightweight, architecture-compatible with FL, and sensitive to each client’s unique operational domain.

To support secure federation, each client maps its model outputs into a shared representation space via dimensionality-matching layers. Before transmission, model parameters are perturbed with calibrated Laplacian noise to ensure privacy and embedded into image-like structures using reversible data hiding, thereby preserving both precision and security. Cryptographic signatures and local logging ensure the authenticity and traceability of each update. These encoded updates, once transmitted through secure channels, enable consistent and interpretable aggregation at the server side. This localized yet interoperable approach ensures that every client contributes meaningfully to the global model while preserving privacy, architectural flexibility, and robustness in WAAM-specific anomaly detection.

3.4. Global Server Model Aggregation

Aggregating updates from heterogeneous WAAM clients poses challenges due to varying data types, sample sizes, and model dynamics. Simple averaging can bias the global model toward clients with more data or dominant feature patterns, reducing the system’s ability to generalize. To address this, the server initiates a selective aggregation process that assesses the alignment of each client update with the federation’s latent space using similarity metrics such as gradient direction and statistical distribution. Outliers or inconsistent updates are down-weighted or excluded to enhance robustness. Updates are decoded from their reversible data-hiding format, verified for authenticity via cryptographic signatures, and then projected into a common latent space to reconcile architectural differences. The server calculates update weights based on historical reliability and consistency, aggregating the remaining updates using a strategy that emphasizes diversity and stability. To support local adaptation, client-specific personalization layers are added before redistributing the refined global model.

Throughout training, the server monitors convergence by tracking validation metrics and loss stabilization across rounds. If progress plateaus, aggregation is halted to conserve resources and prevent overfitting. The system dynamically adjusts communication schedules based on client availability and data shifts, incorporating explainability tools such as feature attribution to enhance transparency and operator trust. Final global models are securely redistributed with privacy-preserving guarantees intact. Overall, this aggregation strategy ensures a secure, adaptive, and generalizable federated learning cycle, enabling effective anomaly detection in distributed WAAM systems under non-IID conditions.

4. System Development Architecture

To validate the proposed FL framework outlined in

Section 3, a scaled implementation was developed to serve as a system-level proof of concept. This implementation demonstrates the end-to-end realization of a secure, distributed anomaly detection pipeline tailored for WAAM environments. Each component of the architecture, from sensor-based data acquisition and preprocessing to reversible data embedding, client-specific model training, and federated coordination, was constructed and tested using real process data captured under controlled deposition scenarios. The setup simulates an eight-client federated ecosystem, where each client represents a distinct subset of process signatures and sensor capabilities, reflecting the variations encountered in practical WAAM systems. By recreating the logical sequence of the methodology in an experimental setting, this section validates the functional interoperability of each module. The following will describe the development pipeline in chronological order, beginning with synchronized data collection and temporal alignment, followed by the implementation of reversible data hiding, local model configuration and training per client, and concluding with the design and operation of the FL framework.

4.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

To train federated client models effectively, a well-structured and synchronized dataset is critical for achieving meaningful convergence across distributed nodes. In this study, a GTAW-based WAAM system was used to collect electrical signals and HDR video of the deposition process. Using computer vision techniques, additional process features, such as torch speed, feed angle, and arc length, were extracted from the video. All data were timestamped and temporally aligned to support LSTM-based time-dependent modeling. The experimental setup consisted of a six-axis Fanuc ArcMate 120iC robot with an R-30iA controller and a Miller Dynasty 400 GTAW power source, allowing for precise control of deposition parameters [

43]. A Weldvis HDR camera captured the weld pool and feed wire under varying lighting conditions. Low-carbon steel was used as the feedstock, and consistent wire feeding was maintained across trials. Two controlled experiments simulated normal and abnormal conditions: one with stable parameters (160 A, 20 cm/min travel speed, 160 cm/min feed rate), and another with altered settings (140 A, 40 cm/min, 180 cm/min) to induce defects. These trials provided the basis for binary labeling of the dataset. All sensor data were continuously and synchronously recorded, providing temporally and spatially rich inputs for federated LSTM-based anomaly detection.

First, the electrical data comprising current and voltage signals was collected using a Miller Insight ArcAgent Auto sensor, which samples at a temporal resolution of 0.10 seconds, ensuring sufficient granularity for capturing dynamic fluctuations during deposition. Raw signal traces often contain inconsistent entries due to arc instability at ignition and extinction; therefore, the initial and terminal segments of the sequence were cleaned by removing frames with near-zero values using a binary thresholding scheme. Furthermore, the recorded timestamps from the current-voltage sensor were used as reference markers for synchronizing all other sensor data, including video-based speed and geometric parameters. A significant preprocessing step involved detecting and eliminating anomalous data points introduced by sensor latency and transient disruptions, such as those occurring during rapid parameter transitions or signal dropout. Outliers were identified using statistical filters and replaced via interpolation to preserve temporal continuity. These cleaning procedures were essential to mitigate noise-induced irregularities that could degrade model generalization. The resulting voltage and current time-series data, free of noise and aligned with video-derived timestamps, form a reliable and temporally coherent input to the LSTM classifier for each respective client model.

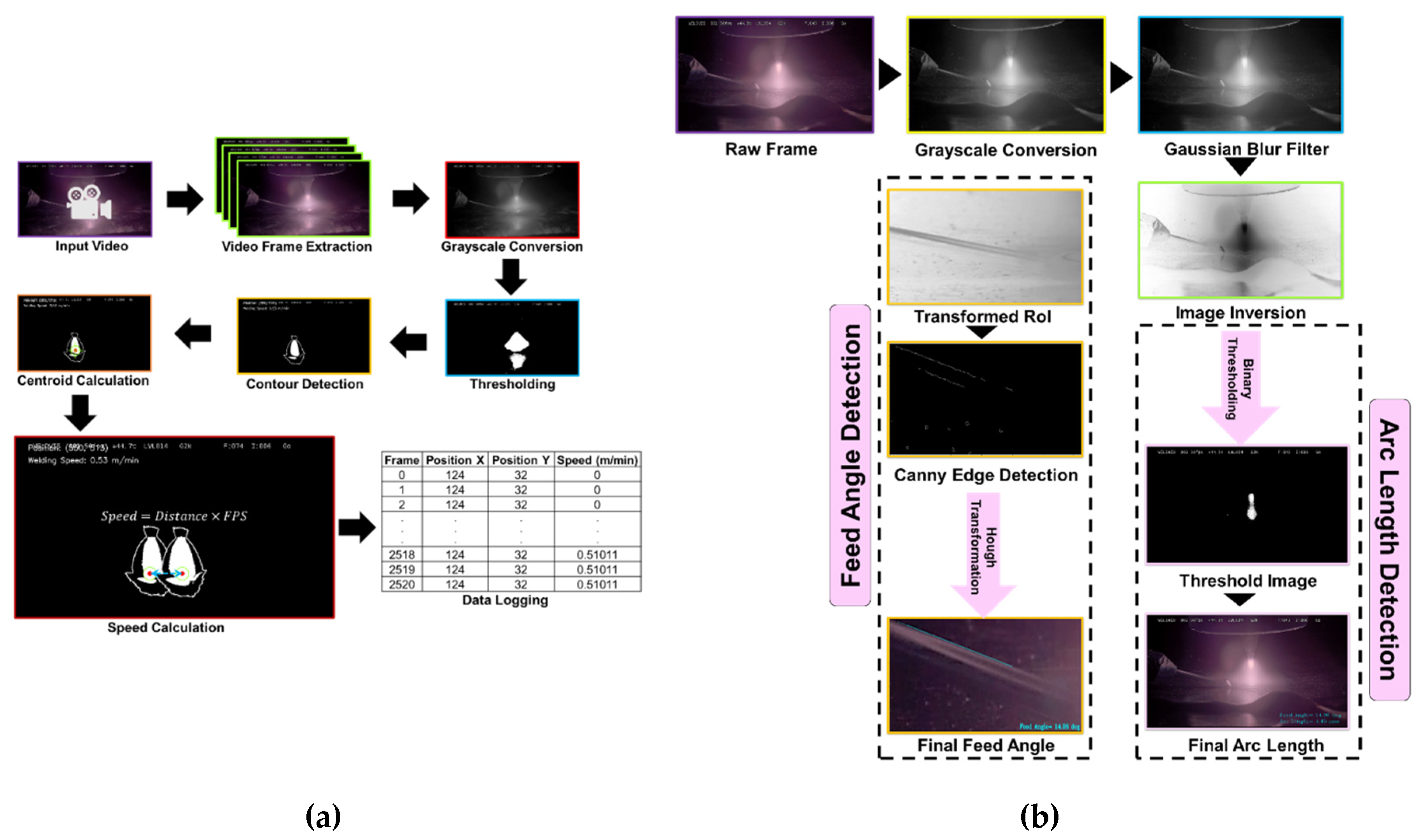

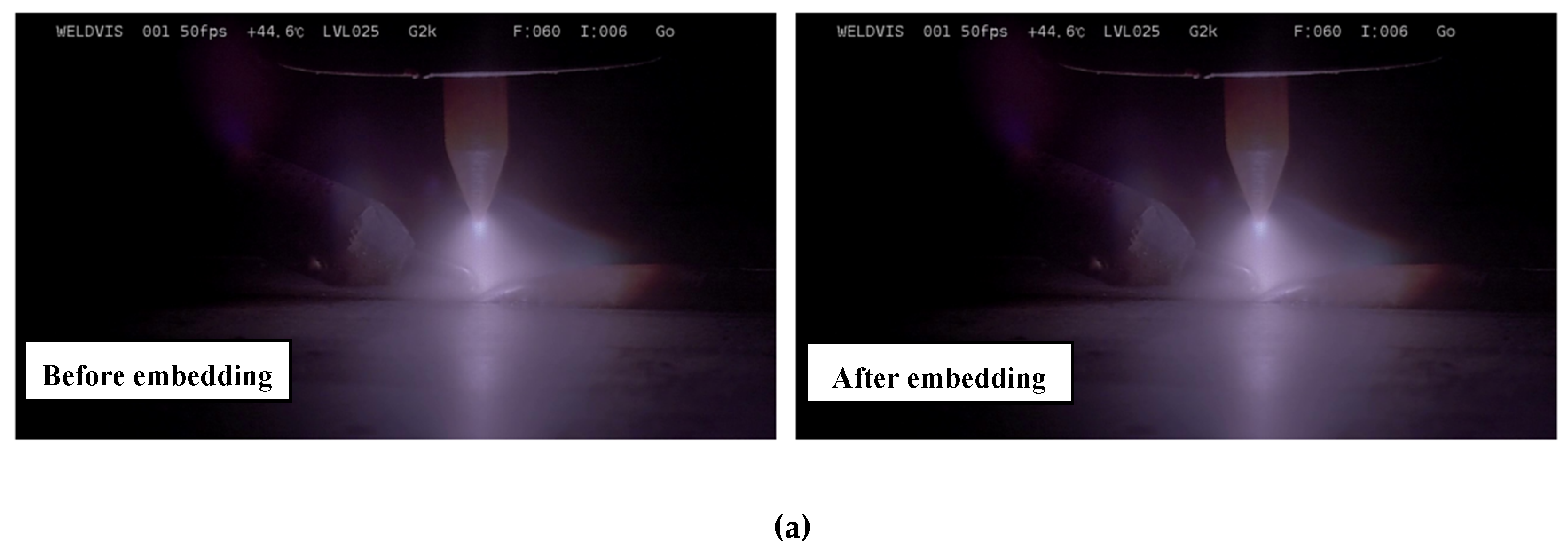

Second, both normal and abnormal deposition sequences under controlled conditions, as are depicted in

Figure 2(a). Each video stream was decomposed into individual frames, with the frame per second (FPS) extracted to enable time dependency. Following frame extraction, grayscale conversion was applied to reduce computational overhead, and binary thresholding was used to isolate high-intensity regions corresponding to the welding arc. Contour detection was performed on each thresholded frame, and the largest contour, typically representing the arc plasma, was selected for centroid computation. Spatial moments of the contour were used to determine the centroid position

per frame, which represents the torch’s instantaneous spatial location. The welding speed

was then estimated by computing the Euclidean displacement of the centroid between consecutive frames and scaling it to physical units using the FPS and a spatial calibration factor

mm/pixel, as in Eq. 1.

where

and

are the centroid positions at consecutive time steps. The entire process of which has been shown in

Algorithm 1. These speed values were paired with the corresponding centroid coordinates and timestamped at 0.10-second intervals to align with the current-voltage measurements. Given that real-world sensor fusion requires time synchronization, the centroidal position and derived speed were matched and mapped onto the current-voltage timestamp axis to ensure time-based coherence across data types.

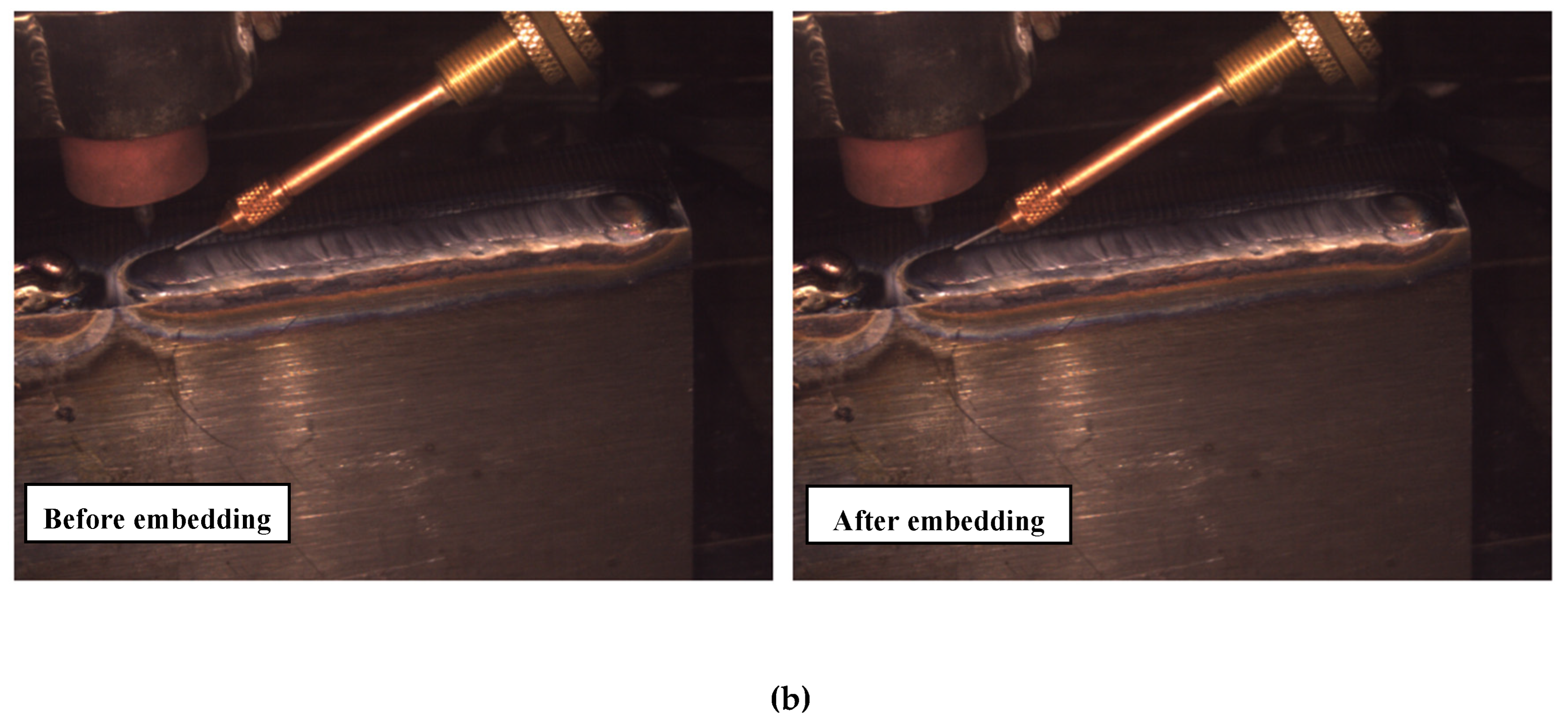

Finally, the detection of part parameters; specifically arc length and feed angle; was conducted using computer vision techniques applied to HDR video frames, allowing precise geometric characterization of the welding process, as depicted in

Figure 2(b). Arc length, denoted as

, was estimated by measuring the vertical spread of the arc plasma region in the image. First, each frame was converted to grayscale, and a fixed binary threshold of intensity 190 was applied to isolate the arc region. The vertical extent of the arc was computed by identifying the first and last rows containing non-zero pixels in the binary image, and the difference between these rows provided the arc height in pixels. Assuming a vertical spatial resolution of 100 pixels per millimeter, the arc length was computed as Eq. 2.

where

and

represent the bottommost and topmost positions of the arc segment, respectively. For feed angle estimation, a region of interest (ROI) was cropped around the feed wire to isolate the visible wire path. The cropped segment was preprocessed with grayscale inversion, contrast normalization, and multi-stage Gaussian blurring to enhance edge features while suppressing noise. Canny edge detection was applied to extract the wire boundaries, followed by a probabilistic Hough Line Transform to detect straight line segments representing the wire orientation. The angle of each line was computed using its slope and averaged over all detected lines to yield the feed angle

by Eq. 3.

Each value of

and

was timestamped and interpolated to match the current-voltage time in

Section 4.2, ensuring multi-data temporal alignment. Heuristics of determining

and

was shown in

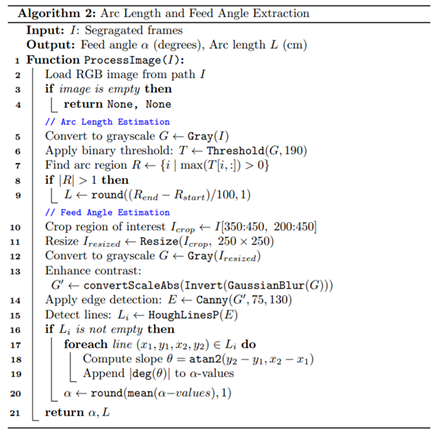

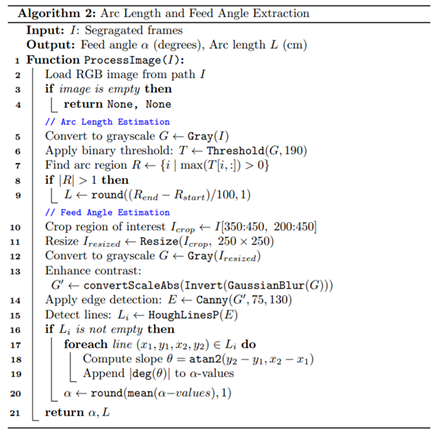

Algorithm 2.

Following the synchronization and preprocessing of sensor-derived and vision-based process features, the next step involved constructing labeled datasets to enable supervised training across federated clients. Each deposition video was independently reviewed by two WAAM domain experts, who visually identified normal and abnormal deposition sequences based solely on unbiased observation of the bead morphology. These annotations were mapped to exact frame timestamps and aligned with corresponding multimodal feature sets. The labeled data included temporally synchronized current and voltage signals obtained directly from sensors, as well as centroid position and welding speed, which; although part of the same labeled dataset; were extracted using a frame-wise computer vision pipeline. Each instance was assigned a binary class label, with ‘0’ denoting normal and ‘1’ representing abnormal deposition. Separately, geometric parameters such as arc length and feed angle matched to their respective timestamps and labeled in the same manner. These two labeled sources were distributed across eight client models with distinct input combinations, as described in

Section 4.3. To match non-uniform industrial data availability, clients received varying numbers of samples, ranging from 216 in Client 1 to 1692 in Client 3 shown in

Table 1, while a consistent 75:25 train-test partitioning was applied across all clients.

4.2. Reversible Data Hiding

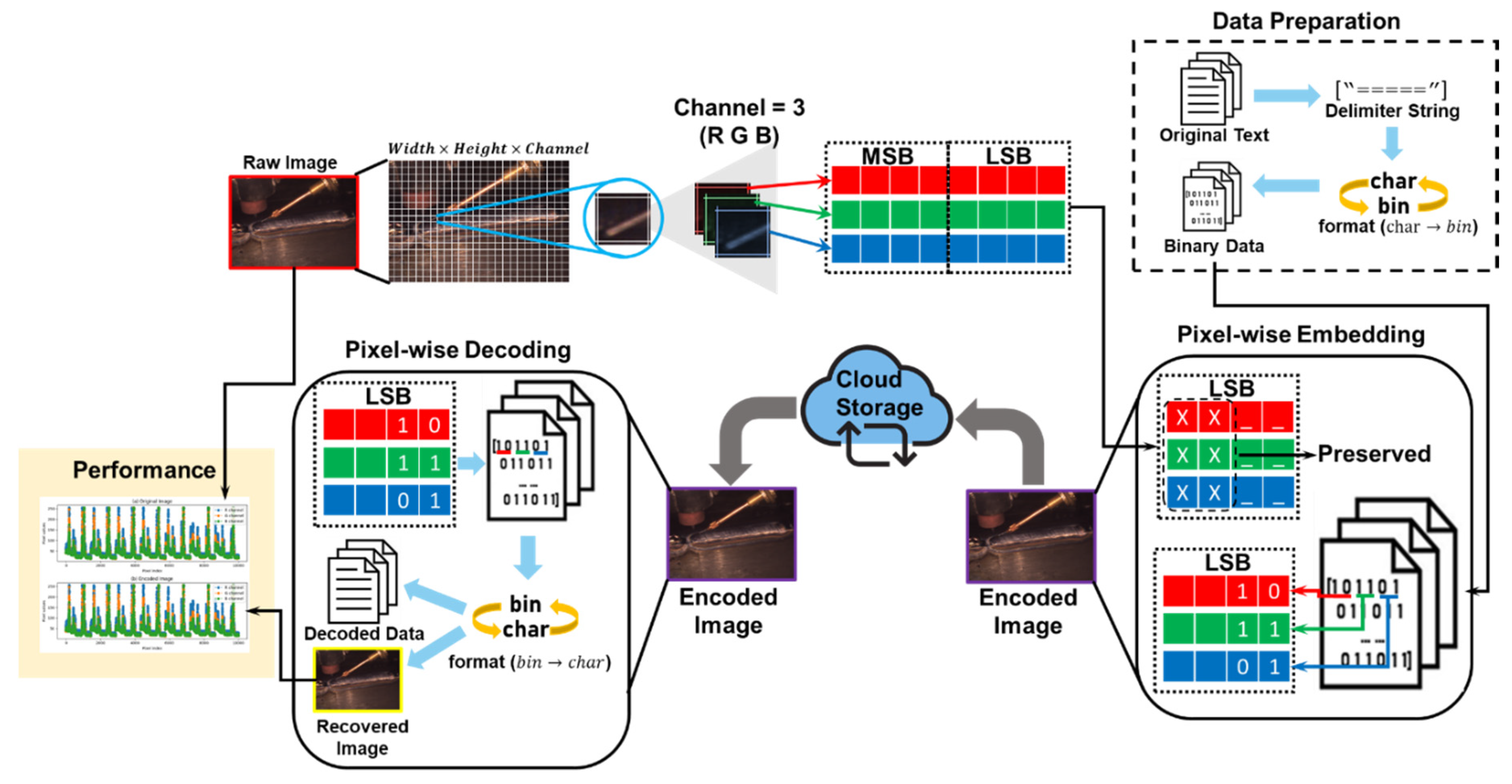

The reversible data hiding in the encrypted domain (RDHE) module, illustrated in

Figure 3, is designed to embed high-resolution, WAAM process parameters (current, voltage, travel speed, arc length, and feed angle) into visual process images without introducing irreversible distortion similar to [

44]. The process begins with the acquisition of a weld image during the deposition cycle, which is spatially divided into

Each sub-block is decomposed into its RGB planes, denoted as

serving as the embedding substrates. These channels are scanned in a pixel-wise raster order, and low-gradient regions, determined via a Sobel and Laplacian filter threshold, are identified as candidate embedding zones to avoid perceptual degradation at high-intensity edges near the weld pool. The payload

, which encapsulates the serialized process parameters in 8-bit ASCII format, is then converted into a binary stream

, appended with a fixed delimiter pattern “=====“ for stream termination. The embedding operation modifies the two least significant bits of selected pixel values

usin Eq. 4.

where,

and

denotes the inverse binary-to-decimal mapping. This substitution yields the encoded image

, which visually preserves the structural texture and colorimetry of the original image

, while encapsulating process intelligence at a pixel level.

Before transmission, a distortion verification stage evaluates the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and mean squared error (MSE) between and to ensure that the embedding-induced perturbation remains below a perceptual threshold. In parallel, a digest of the unmodified image is embedded within , enabling post-hoc verification of image integrity upon decoding. This interfaced mechanism supports both synchronous and asynchronous client-server data retrieval and can be used for flexible integration into edge-deployed WAAM control systems and cloud-aggregated analytics pipelines.

Decoding is initiated by retrieving the stored image and its associated metadata. The system re-scans the image in accordance with the spatial and channel-wise offset map, extracting the embedded two-bit sequences from

using Eq. 5.

The aggregated binary stream is parsed until the terminator sequence is identified, at which point it is deserialized to recover the original textual parameter payload. Simultaneously, the image is restored to its original form by reconstructing the higher-order bits and reinserting preserved LSBs from the reversible buffer using Eq. 6.

where

, denotes the retained LSB snapshot prior to embedding. This guarantees exact recovery of

I, and ensures that all embedded WAAM parameters are faithfully restored.

The RDHE pipeline can support modular deployment and real-time streaming, enabling continuous, in-situ encoding of high-speed weld monitoring feeds in edge-mounted WAAM systems. As shown in

Figure 3, it decouples the encoding and decoding layers, facilitating scalable client-server interaction across a federated network of WAAM nodes. The encoded image functions dually as a visual object and a secure telemetry carrier, allowing seamless integration with FL workflows. This process ensures that WAAM-specific process data are embedded, transported, and recovered without compromising confidentiality or signal integrity.

4.3. Client Models Development

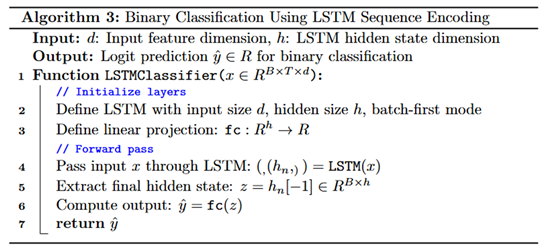

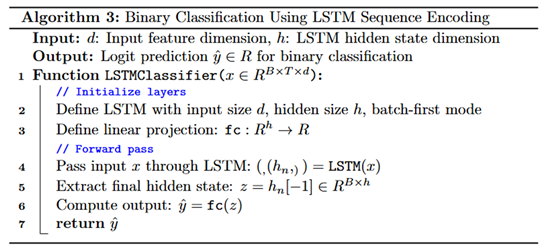

Each federated client in the WAAM system is configured to train a local sequence-based classifier using a shared architectural backbone composed of an LSTM encoder followed by a linear classification head. The adopted model, referred to as LSTMClassifier, is designed to process fixed-length temporal sequences and is parameterized by an input feature dimension of three and a hidden state size of 256 as described by Algorithm 3. The recurrent layer is implemented to, capture dynamic time dependencies across successive observations within each client’s local sensor stream. The hidden layers extracted at the final time step are passed through a fully connected layer with a single output neuron, representing the logit for binary classification between normal and abnormal deposition states. The input to each model is a tensor of shape , where is the number of sequences, 5 is the sequence length, and 3 is the dimensionality of the client-specific feature set. To preserve the chronological structure of the input signals, overlapping temporal windows are constructed using a sliding frame technique, enabling the model to learn short-term temporal variations crucial for identifying anomalous transitions in WAAM. Although the core model structure remains identical across all clients, the feature spaces differ, reflecting the heterogeneous nature of data distributed across the sensor network. During the federated training phase, only the parameters of the shared LSTM layer are uploaded to the federated server, while the final fully connected layer is retained locally when using personalization strategies such as FedPer. This ensures that each client maintains its specialized decision boundary tuned to its own feature distribution while contributing to the globally shared temporal encoder.

The eight clients participating in the FL system are differentiated based on the data types of their input features, each reflecting a unique sensor perspective on the WAAM process, to replicate real-world muti-enterprise WAAM process. Clients 01 to 04 form the first cluster of diversity, each focusing on a distinct aspect of process monitoring. Client 01 utilizes average voltage, average current, and normalized timestamp as its input features, emphasizing electrical signal dynamics and temporal progression during deposition. The timestamp is normalized to [0,1] to maintain scale consistency and prevent temporal magnitude from dominating the input. Client 02 incorporates spatial centroids of the arc region, and coordinates, together with arc voltage, linking arc geometry with instantaneous electrical behavior. This fusion allows the model to learn spatiotemporal correlations between arc spread and voltage fluctuations. Client 03 extends spatial tracking by combining welding speed with centroid coordinates, thereby encoding motion-induced variations and spatial drift, which are indicative of instability in torch trajectory. In contrast, Client 04 is entirely geometric and focuses on arc length, feed angle, and timestamp. These features are extracted using vision-based analysis of HDR frames and represent structural characteristics of the weld bead and wire orientation. Prior to training, Client 04 applies standard scaling normalization to arc length and feed angle due to their varying physical scales and to ensure that both features contribute equally during gradient updates. For all clients, data is converted into five-step overlapping sequences using sliding windows, such that the sequence includes time steps with the label taken from the final frame. This setup enables the model to learn not only the temporal evolution of the signal but also localized transitions that may signify emerging defects.

Clients 05 through 08 extend the representational diversity of the federated setup by combining hybrid features from both electrical and kinematic modalities, offering complementary perspectives for anomaly detection, from diverse enterprises. Client 05 utilizes speed, current, and voltage as its feature set, capturing the joint dynamics of mechanical motion and electrical load fluctuations, which are especially useful for detecting disruptions caused by arc instability or inconsistent travel. Client 06 incorporates timestamp, speed, and current, embedding explicit temporal progression into the sequence alongside instantaneous physical measurements; this configuration is particularly useful for modeling time drift and time-aligned degradation. Client 07 is structurally similar, replacing current with voltage, allowing the model to capture high-frequency variations in power delivery relative to travel speed and timestamp. In contrast, Client 08 combines current with spatial position (centroid_x and centroid_y), enabling a unique fusion of electrical energy and localized arc trajectory. For all clients, the extracted feature sequences are sampled at 0.10-second intervals and interpolated when necessary to match the reference timestamps derived from the current-voltage signal, ensuring multimodal synchronization. The resulting sequence tensor, uniformly shaped as preserves the order and spacing necessary for LSTM-based temporal learning. Training data is fed into Data Loader objects with a fixed batch size of 32, preserving mini-batch stochasticity while ensuring consistent time structure within each sequence. The use of timestamp alignment across all clients ensures that each local model operates within a temporally harmonized view of the process, even though the input features vary. This deliberate heterogeneity across Clients 05 to 08 introduces robustness into the global model by allowing it to encode diverse forms of anomaly indicators, ranging from spatial distortion to electrical jitter, thereby strengthening the generalization capability of the federated LSTM encoder.

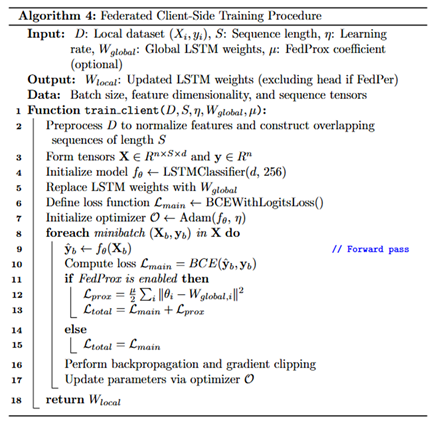

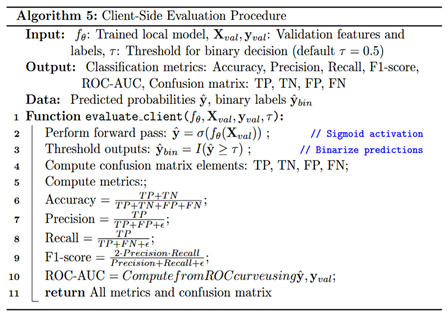

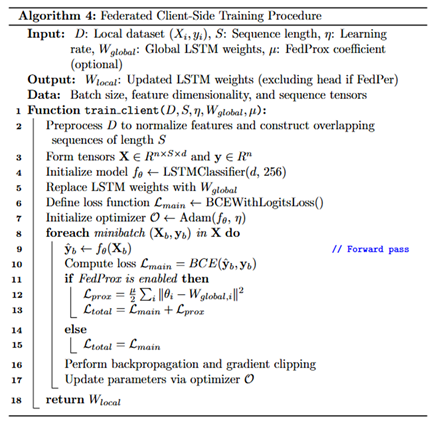

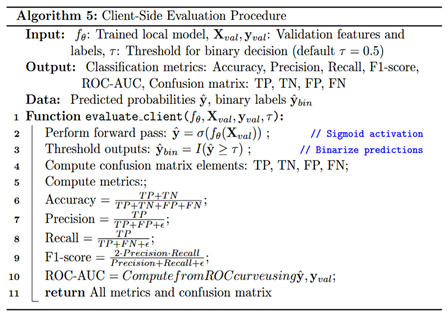

During local training, each client executes a full optimization cycle using its data-specific sequences, leveraging a recurrent learning architecture tuned for temporal classification, described by Algorithm 4. The forward pass involves processing each input sequence through the LSTM layer to extract temporal features, followed by a projection through the fully connected classification head, which produces a scalar logit for binary classification. The loss is computed using the Binary cross-entropy loss function, which integrates sigmoid activation and cross-entropy into a numerically stable formulation suitable for binary output. For optimization, all clients adopt the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, and gradient norms are clipped to a maximum of 1.0 to prevent instability from exploding gradients. When the FedProx strategy is activated, a proximal regularization term is added to the loss function to penalize deviation from the received global weights, defined as , where acts as the regularization coefficient. This term encourages each client’s update to stay within a bounded neighborhood of the global model, thus mitigating divergence due to non-IID data. After training, only the LSTM encoder weights are shared with the server, while the classifier head remains local when FedPer is used, thereby enabling client-specific decision boundaries. Evaluation is performed by thresholding the sigmoid-activated outputs at 0.5 and computing performance metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, as described by Algorithm 5. Each client logs its evaluation metrics and confusion matrix for each round, enabling fine-grained analysis of local generalization. These logs also contribute to the aggregated global metrics stored on the server. Collectively, this federated training and evaluation pipeline ensures that each client contributes to a robust global temporal encoder while maintaining architectural consistency and data privacy, which are critical for secure, distributed WAAM anomaly detection.

4.4. Federated Learning Approach

In the FL approach, each WAAM client performs local training on its own time-series process data, which includes sensor-specific modalities. Rather than sharing raw data, each client sends the updated weights of its local LSTM model to a central server, which collects these weights, computes an aggregated global model, and sends the updated model back to all clients for the next training round.

Each of the eight WAAM clients is designed to handle a unique combination of process parameters, reflecting the multi-modal nature of the system. These data include timestamped measurements of current, voltage, centroidal position, linear travel speed, feed angle, and arc length; each of which carries distinct temporal dynamics relevant to the WAAM deposition process. Prior to model training, the raw sensor signals are segmented into overlapping fixed-length sequences of five-time steps, which serve as inputs to a client-specific LSTMClassifier. The LSTM model, comprising a recurrent layer and a fully connected output layer, learns to map temporal input features to binary labels representing normal and anomalous deposition. The model training is performed using a binary cross-entropy loss function with logits and optimized using the Adam optimizer with gradient clipping to stabilize training. The temporal correlations captured in the hidden states of the LSTM are crucial for identifying deviations in process behavior that unfold across consecutive time steps.

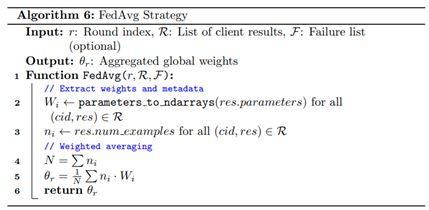

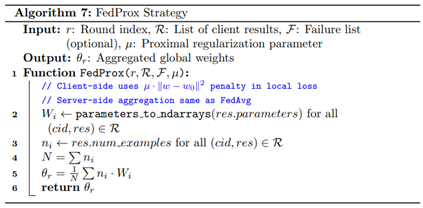

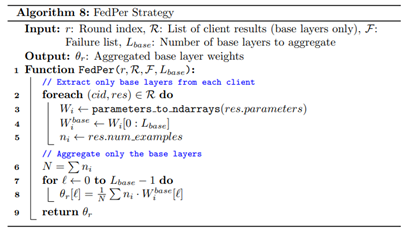

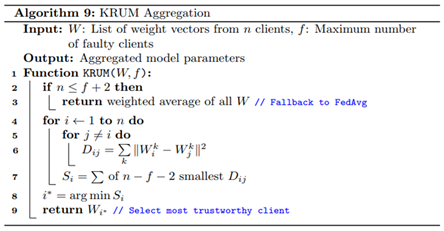

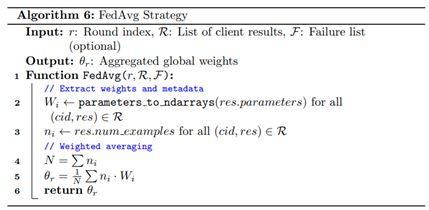

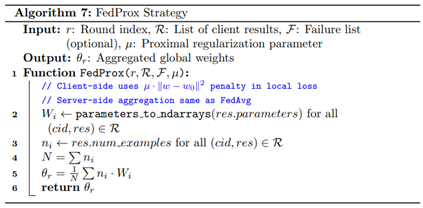

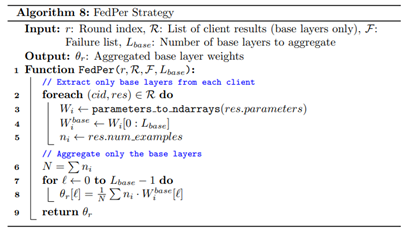

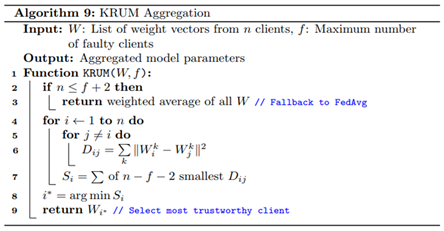

First, after local training, the client prepares its model for participation in the federated round by selecting only the base LSTM layer weights for upload. The fully connected classification layer remains local, particularly in the case of personalization strategies such as Federated Personalization FedPer, which aims to adapt decision boundaries to local data heterogeneity by excluding the final layer from global, given by Algorithm 8. The server collects these LSTM weights from all clients and constructs a global model by applying one of the defined federated optimization strategies. In this study, we employed three distinct strategies to evaluate the effects of optimization under varying conditions. Federated Averaging (FedAvg), implemented as Algorithm 6, the baseline, performs a weighted average of client models using the number of local data samples as the weight factor. This method assumes IID distributions and thus serves as a performance benchmark under relatively homogeneous scenarios. Federated Proximal (FedProx), developed as Algorithm 7, introduces an additional regularization term to the local objective function, penalizing divergence from the global model by imposing a proximal constraint. This improves stability when client data are non-identically distributed by discouraging large local deviations. Federated Personalization (FedPer) is particularly suited for environments where clients have fundamentally distinct data distributions, as it maintains shared representations in the encoder while enabling local adaptation through private classification layers.

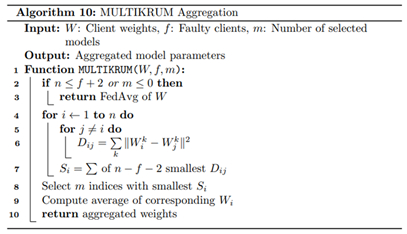

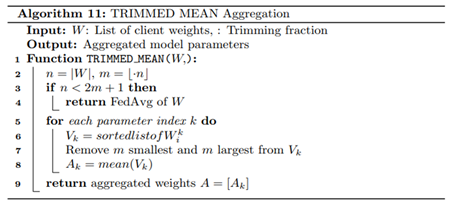

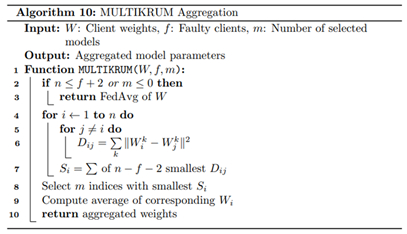

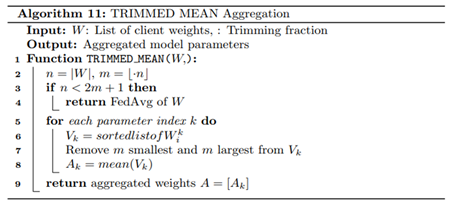

Second, to ensure robustness against untrustworthy or faulty clients, we employed resilient aggregation mechanisms that are selectively triggered after a fixed number of training rounds. Specifically, we implemented three robust aggregation strategies, Krum, Multi-Krum, and Trimmed Mean, that each mitigates the influence of outliers or poisoned updates. Krum aggregation, shown in Algorithm. 9, computes pairwise Euclidean distances between client models and selects the update most similar to its nearest neighbors, effectively eliminating aberrant updates that deviate significantly from the majority. Multi-Krum generalizes this by selecting multiple such close-to-majority models and averaging them as given by Algorithm 10, thereby improving resilience while allowing greater representation. Trimmed Mean takes a statistical approach as in Algorithm 11 by sorting each weight element and removing extreme values before averaging, thus minimizing the effect of adversarial noise or anomalous gradients. These mechanisms are activated after a predefined threshold round to allow the initial rounds to benefit from unconstrained learning diversity before enforcing robustness and are used in combination with each federated optimization strategy to evaluate a total of twelve configurations. This exhaustive permutation; comprising FedAvg, FedProx, and FedPer, each paired with Vanilla, Krum, Multi-Krum, and Trimmed Mean; allows systematic assessment of convergence stability and resilience under varying assumptions of data distribution and client reliability.

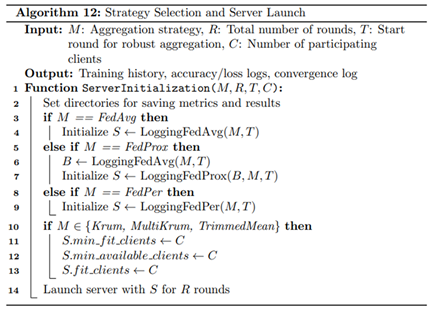

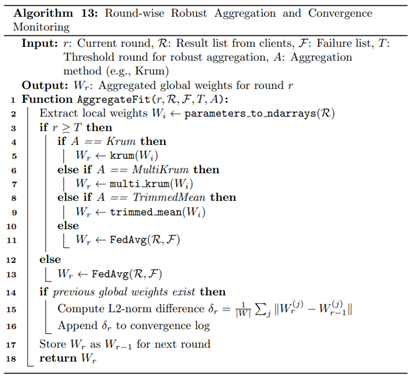

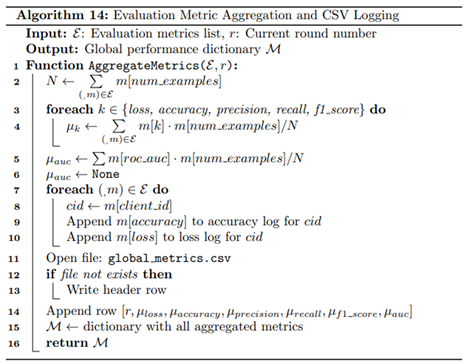

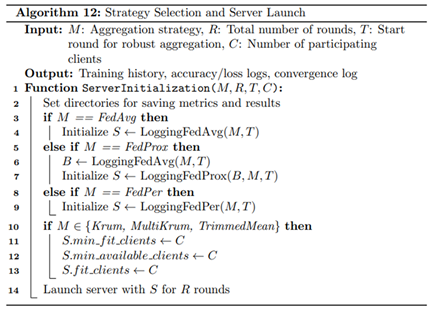

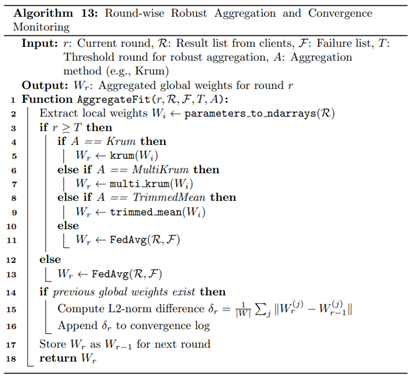

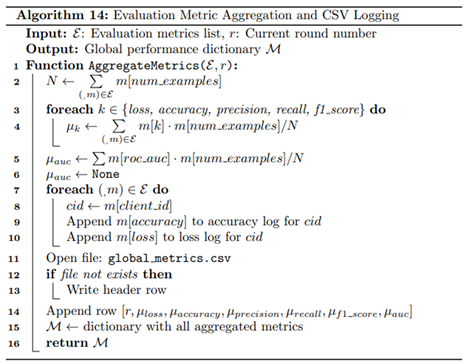

Finally, the central server is responsible for coordinating each training round, managing model updates, and evaluating convergence through empirical tracking implemented using Algorithms 12-14. At each round, the server initializes or updates the global model and distributes its parameters to the selected clients. Once the updated models are returned, it computes the L2 norm difference between successive global model parameters to quantify the progression of convergence, a metric that reflects model stability and learning dynamics over time. The server then aggregates client-reported evaluation metrics, including loss, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, using weighted averages based on local validation sample sizes. These global metrics are saved systematically for reproducibility and downstream analysis. Additionally, the server stores client-specific metrics and confusion matrices to support diagnostic performance evaluations. This logging infrastructure enables the generation of detailed visualizations, such as round-wise accuracy trends, loss curves, and convergence trajectories, offering a transparent understanding of model behavior across strategies and clients. Through this structured and modular FL framework, the system is capable of addressing data privacy, heterogeneity, and adversarial risk in distributed WAAM environments, while enabling comparative benchmarking across multiple learning configurations.

5. Results and Discussion

The evaluation of the FL framework designed for anomaly detection in WAAM is carried out through a series of controlled experiments. The focus of the evaluation is to assess how well different federated strategies perform under varying levels of model personalization and aggregation robustness. Specifically, the study compares three federated strategies, FedAvg, FedPer, and FedProx, each deployed over 100 communication rounds. For every strategy, four aggregation techniques are tested: standard federated averaging (Vanilla), KRUM, Multi-KRUM, and Trimmed Mean. This combination yields twelve distinct configurations that are evaluated using both global metrics and client-specific metrics. The aim is to capture the model behavior not only in terms of overall convergence and stability but also in terms of fairness and consistency across data sources. These configurations are tested on client-specific datasets extracted from diverse sensor streams.

For every combination of strategy and aggregator, both global and local classification performance is measured using five standard evaluation metrics: Accuracy, F1-score, Precision, Recall, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC). Additionally, the optimization behavior of the global model is captured through the L2-norm of the weight difference between consecutive communication rounds, which serves as an indicator of convergence stability. Moreover, to ensure secure and verifiable data transmission, the reversible data hiding in encrypted domain (RDHE) mechanism is separately evaluated based on Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and embedding rate. The local client models across all sites are implemented using LSTM networks trained on time-aligned, process-specific data matrices. The evaluation results presented in the following aim to uncover the performance boundaries and deployment feasibility of FL models in decentralized WAAM environments.

5.1. Global Performance Across Strategies and Aggregators

The choice of aggregation strategy significantly influenced global performance across all federated configurations, as seen from the final-round metrics and their trajectory in

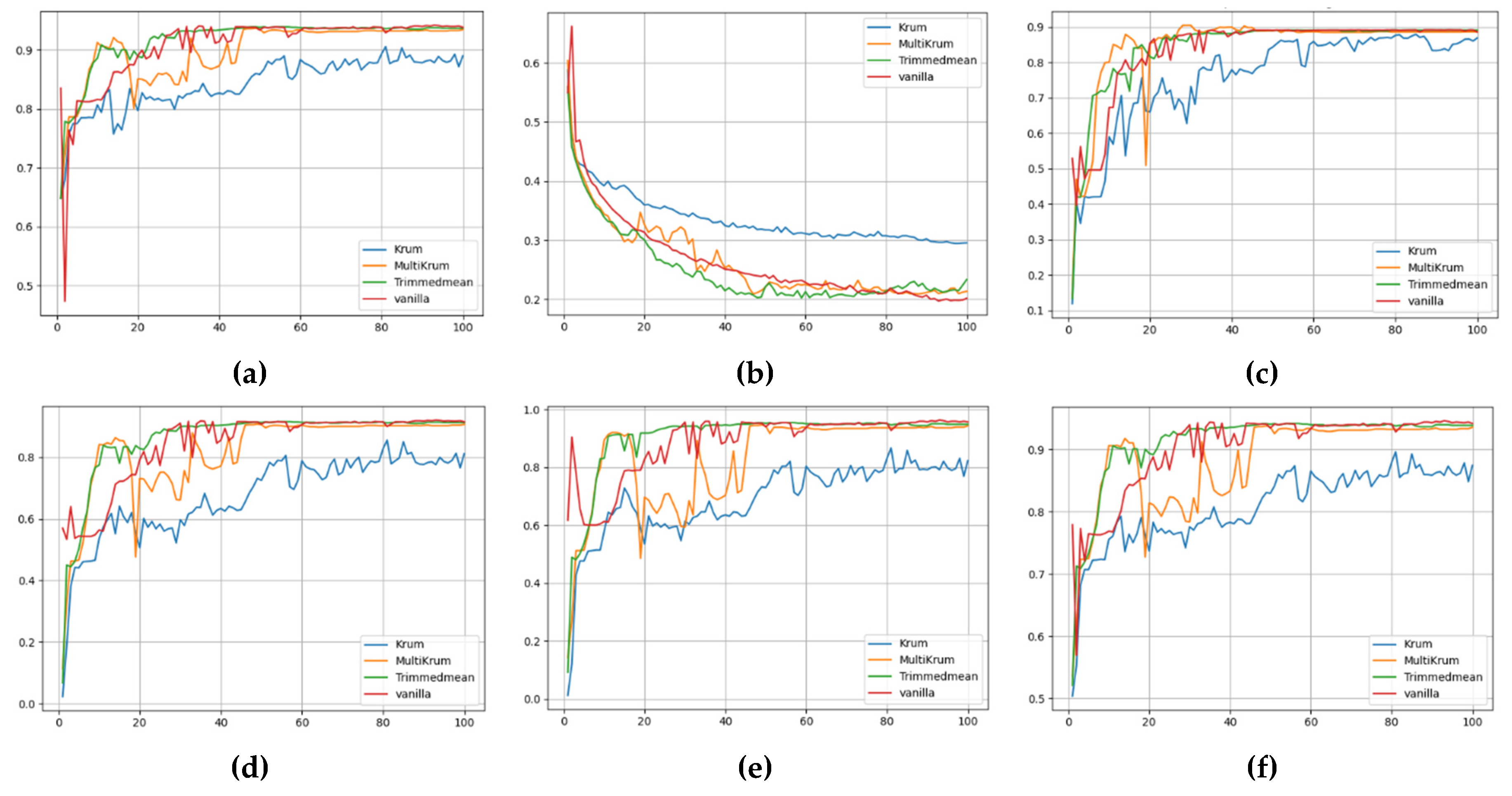

Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 4 provides a comprehensive view of the global performance metrics for the FedAvg strategy across different aggregation methods. The accuracy trend in

Figure 4(a) shows that Trimmed Mean and Multi-KRUM achieve higher and more stable accuracy than KRUM, which lags behind consistently. In

Figure 4(b), the loss curve for KRUM fluctuates heavily, indicating unstable convergence, while Trimmed Mean ensures smoother and faster loss reduction. Precision, illustrated in

Figure 4(c), peaks under Trimmed Mean and Multi-KRUM, whereas KRUM exhibits suppressed values. The F1-score plot in

Figure 4(d) mirrors these results, with Trimmed Mean achieving over 0.91 by round 100. Recall, seen in

Figure 4(e), follows a similar trend, with KRUM failing to exceed 0.88, while other methods stabilize beyond 0.93. Lastly, the ROC AUC in

Figure 4(f) highlights the early underperformance of KRUM and the consistent superiority of Multi-KRUM and Trimmed Mean throughout the communication rounds.

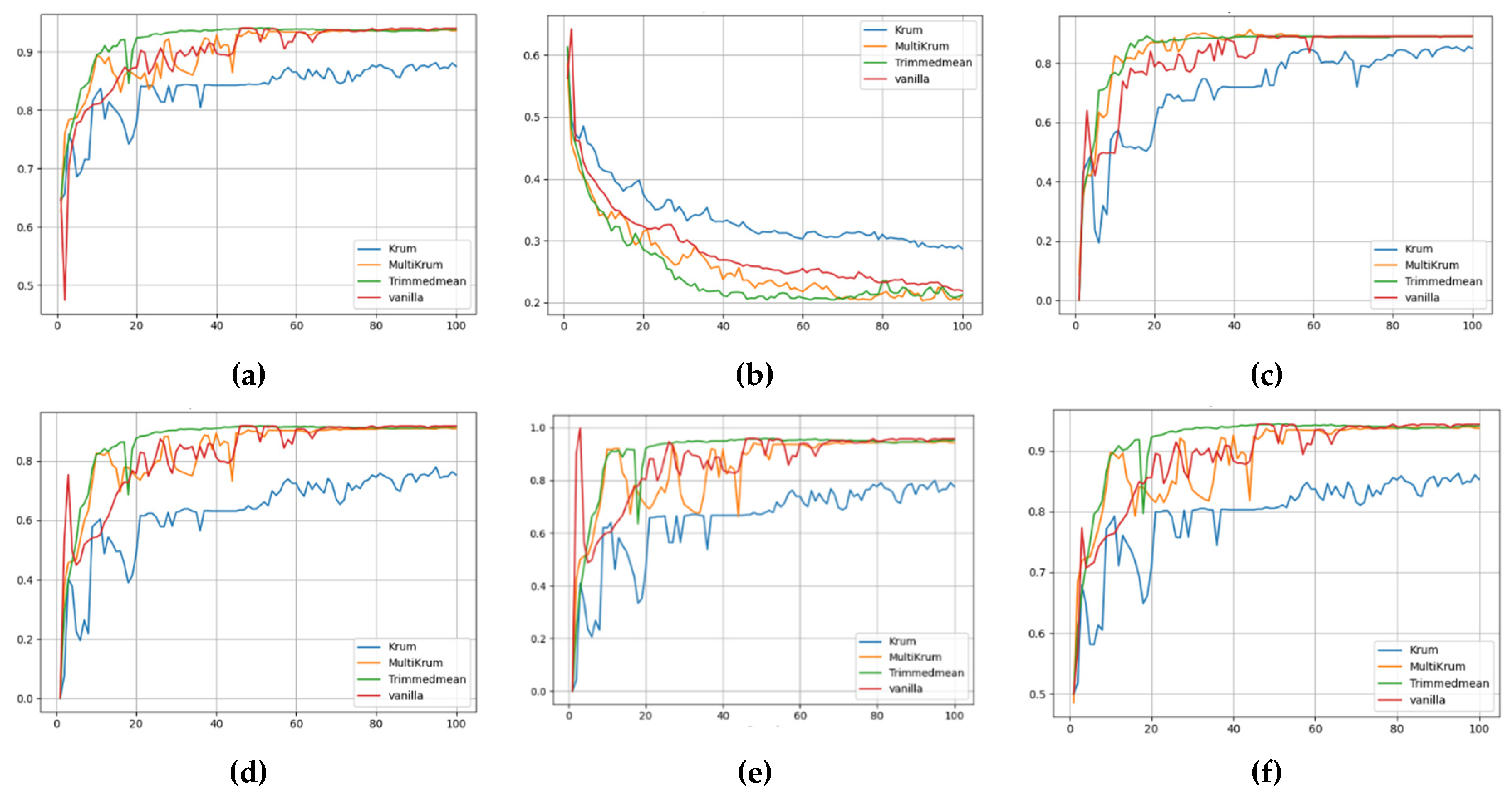

Figure 5 illustrates the performance of the FedPer strategy, which demonstrates the most rapid and robust learning across all metrics. Accuracy, in

Figure 5(a), rises quickly and converges above 0.95 for all aggregation methods except KRUM, which trails behind. In

Figure 5(b), the loss under Trimmed Mean and Multi-KRUM reduces sharply and remains below 0.2, while KRUM’s loss remains elevated. Precision values in

Figure 5(c) show that Vanilla, Multi-KRUM, and Trimmed Mean offer closely matched performance, with KRUM again being the weakest.

Figure 5(d) highlights FedPer’s F1-score dominance, Trimmed Mean surpasses 0.91 early and maintains it, outperforming other aggregators. Recall scores in

Figure 5(e) show that all aggregators perform well initially, but KRUM degrades over time. In

Figure 5(f), the ROC AUC curve reaches 0.94 by round 30 under Trimmed Mean, reflecting strong early-stage generalization and robustness in FedPer.

Figure 6 focuses on the FedProx strategy, which achieves stable but slower improvements across all metrics compared to FedAvg and FedPer.

Figure 6(a) shows moderate accuracy growth with Trimmed Mean and Multi-KRUM outperforming KRUM, although the convergence is slower than FedPer. In

Figure 6(b), the global loss steadily declines under all methods, but remains above 0.25 for KRUM, indicating ineffective learning. Precision (

Figure 6(c)) remains balanced and less volatile under Trimmed Mean and Vanilla, while KRUM again underperforms. The F1-score in

Figure 6(d) demonstrates smoother progression, particularly for Trimmed Mean, reaching nearly 0.91 by round 100. Recall (

Figure 6(e)) improves gradually across configurations, but the KRUM curve stagnates around 0.86. In

Figure 6(f), the ROC AUC values confirm that Trimmed Mean ensures robust and steady growth, while KRUM fails to generalize effectively.

Among the three strategies, FedPer consistently outperforms both FedAvg and FedProx across all global metrics, especially when paired with Trimmed Mean or Multi-KRUM. Its partial personalization allows for better adaptation to local data heterogeneity, enabling rapid convergence and higher classification accuracy. FedAvg performs reasonably well under robust aggregators but is more sensitive to noise and client imbalance, particularly when using KRUM, which often undercuts performance. FedProx, while not the fastest learner, shows stable convergence and better resistance to client drift, making it suitable for scenarios where training consistency is prioritized over rapid convergence. Overall, FedPer with Trimmed Mean emerges as the most effective and balanced combination for secure and generalizable anomaly detection in decentralized WAAM environments.

5.2. Client-Level Performance Disaggregation

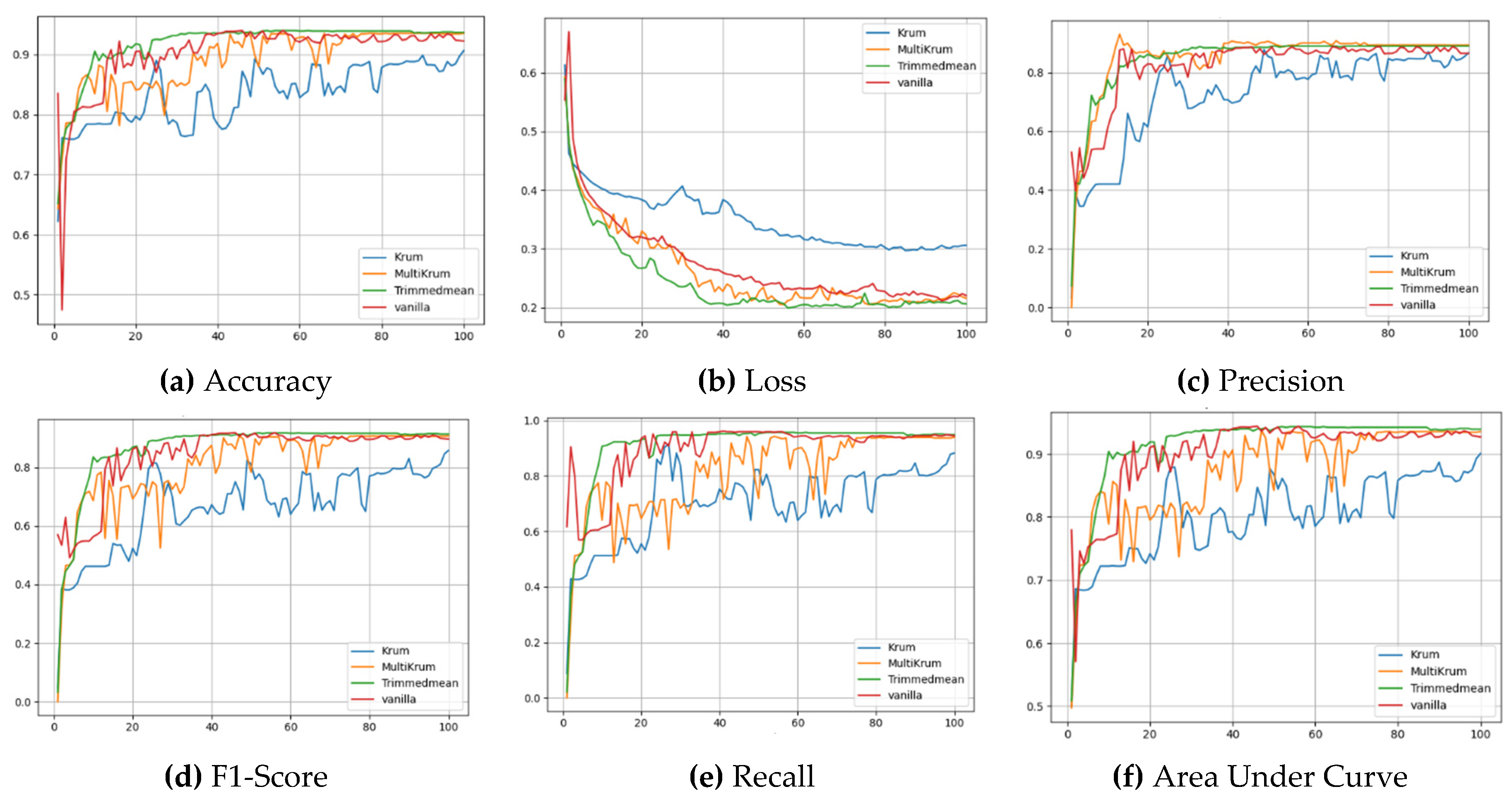

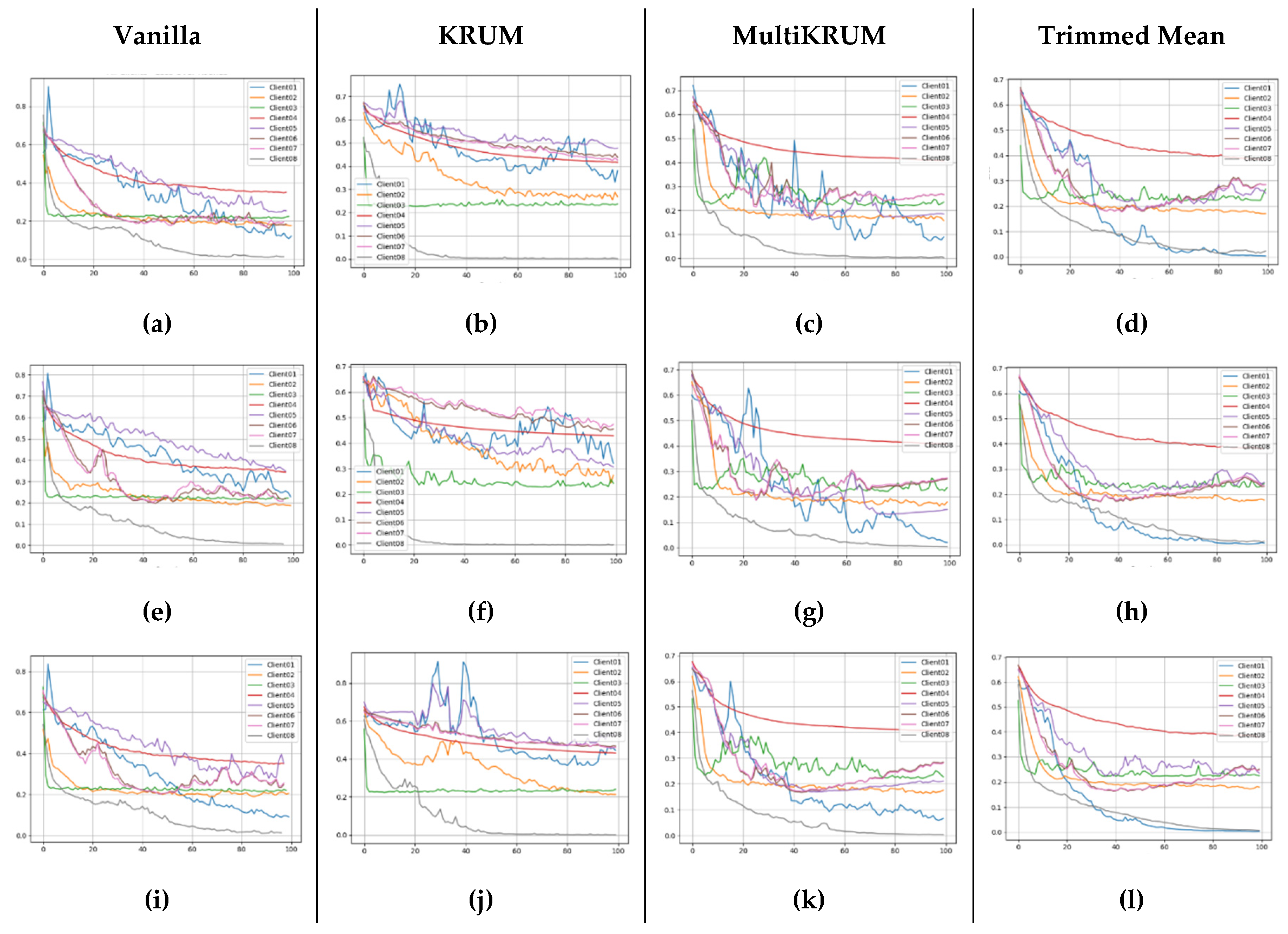

The client-level performance, visualized in

Figure 7, reveals substantial differences in how each federated strategy and aggregation method impacts individual WAAM clients under non-identical data distributions. The variations across client architectures, input modalities, and process complexity result in distinct convergence behaviors, especially when the federated configurations interact with heterogeneous data. Under the FedAvg strategy, as shown in

Figure 7(a–d), we observe sharp inter-client disparities. Clients such as Client 3 (Speed + PosX + PosY) and Client 8 (Current + PosX + PosY) maintain accuracy above 90%, whereas Client 4 (Time + Arc Length + Feed Angle) stagnates around 80% accuracy with elevated loss. The use of KRUM exacerbates these differences, leading to erratic performance in Clients 1 and 5 and delayed improvement for Client 2. In contrast, Multi-KRUM and Trimmed Mean yield greater consistency and better accuracy across clients. When FedPer is employed, as depicted in

Figure 7(e–h), inter-client accuracy trajectories stabilize significantly. Most clients converge to over 90% accuracy, particularly under Trimmed Mean and Vanilla aggregators. Clients such as Client 2 (Voltage + PosX + PosY) and Client 6 (Time + Speed + Current) show strong early acceleration and maintain robust convergence. FedPer’s model personalization clearly supports diverse input distributions and mitigates the negative impact of outlier data. The FedProx strategy, illustrated in

Figure 7(i–l), provides an intermediate level of performance. While its convergence is slower than FedPer, it helps clients like Client 5 recover from early instability. However, KRUM again introduces oscillatory behavior and suppresses learning for several clients. Trimmed Mean remains the most balanced, showing smooth and equitable accuracy gains for most clients, indicating its ability to retain representational diversity without sacrificing stability.

Complementing these accuracy results,

Figure 8 presents the corresponding client-wise loss trajectories, further exposing how aggregation strategies influence learning stability under each federated scheme. In

Figure 8(a–d), loss trends mirror accuracy patterns. KRUM leads to volatility and plateauing, especially for Clients 1 and 5. Multi-KRUM and Trimmed Mean again demonstrate superior performance, reducing client loss more steadily, though early-stage variability remains a concern under Vanilla. Under FedPer, shown in

Figure 9(e–h), clients generally achieve lower final loss values, with Trimmed Mean resulting in the smoothest and most consistent convergence. Client 4 and Client 7, which rely on geometric or time-sensitive inputs, still present minor instability, but overall loss values remain bounded below 0.25, which is an indicator of strong model generalization across the federation. Finally,

Figure 8(i–l) show moderate loss decay across clients. While Trimmed Mean delivers the most consistent performance, KRUM’s restrictive aggregation again hinders certain clients like Client 6 and Client 3. Vanilla performs well for stable clients (e.g., Client 3 and 8) but introduces convergence spikes, reinforcing that careful aggregator selection is critical under FedProx.

Overall, the comparison reveals that FedPer with Trimmed Mean offers the best combination for equitable performance across clients, enabling rapid and stable learning even for those handling noisy, weakly correlated, or visually-derived input features. FedAvg, while occasionally peaking in accuracy for well-behaved clients, fails to support convergence robustness in geometrically complex domains. FedProx, although slower, provides reliable performance improvements in later rounds, especially under robust aggregation schemes. These trends highlight the importance of aligning federated strategy with aggregator design when handling non-IID, multimodal data in distributed WAAM environments.

5.3. Client-Wise Confusion Matrices Analysis

While the global metrics offered valuable insights into convergence behavior and overall classification robustness, a detailed examination of the client-wise confusion matrices, as shown in

Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, reveals the critical role of client-specific data heterogeneity in shaping the final predictive outcomes. Clients were configured to capture distinct process signals, including current-voltage profiles, bead geometry, travel speed, and part parameters, which resulted in non-uniform data distributions and increased task complexity. Under the FedAvg strategy, the Multi-KRUM and Trimmed Mean aggregators yielded strong performance consistency across all clients, with accuracy exceeding 0.90 for all but Client 5, which still improved significantly from 0.69 under KRUM to 0.98 under robust aggregation. Notably, Client 4, which encapsulated arc length and feed angle, exhibited substantial false positive rates under KRUM (FP = 17, Accuracy = 0.80), indicating its sensitivity to process parameter variability and confirming that conservative aggregators suppress local discriminability in such cases. FedPer demonstrated even greater robustness for Clients 5 through 7, where both Trimmed Mean and Multi-KRUM pushed accuracy above 0.96 and minimized false negatives. Notably, the improvement for Client 6, from 0.66 in KRUM to 0.97 in robust aggregators, corresponds to reduced misclassification of current-voltage fluctuations, implying that personalization enables better local calibration against stochastic electrical noise. FedProx exhibited a stabilizing effect, especially for Client 4 and Client 5, where KRUM’s underperformance (Client 5 Accuracy = 0.93) was notably compensated by Trimmed Mean, which elevated all clients beyond 0.94. This behavior is further supported by the consistently low false positives and false negatives observed in Clients 1 and 8 across all configurations, indicating that these clients capture linearly separable features such as centroid shifts and deposition symmetry.

A finer inspection of per-client trade-offs reveals that the impact of federated strategies and aggregation robustness varies significantly across clients due to the nature and entropy of the captured process signals. Client 1, which models current-voltage-time data, consistently achieved perfect classification (Accuracy = 1.00) under all strategies and aggregators, indicating a highly separable anomaly distribution and minimal signal ambiguity. In contrast, Client 2, associated with bead geometry detection through high-dynamic-range imaging, showed pronounced sensitivity to aggregation noise. Under FedPer-KRUM, Client 2’s accuracy dropped to 0.89 with a corresponding false positive rate of 6, whereas both FedAvg and FedProx preserved their performance near 0.94 under Trimmed Mean and Multi-KRUM. This emphasizes the need for robust averaging in vision-based feature representations where illumination artefacts and geometric distortions may mimic anomalous behavior. For Client 3, which handles speed and position data, the classification behavior remained invariant across all strategies, stabilizing around 0.91. This invariance suggests that travel speed anomalies are sufficiently encoded in the temporal patterns captured by the LSTM classifier, and the aggregation strategy plays a minimal role when the feature evolution is strongly time-dependent.

Client 4, responsible for arc length and feed angle estimation, remained the most difficult to stabilize. The misclassifications, reflected in higher false positive rates under KRUM (FP = 17–19) across all strategies, can be attributed to the irregular arc morphology and its erratic gradient behavior, which weak aggregators fail to model effectively. Personalization under FedPer and regularization under FedProx marginally improved accuracy to 0.87, yet Multi-KRUM remained more stable than Vanilla, emphasizing its resilience against local misalignment. Client 5, with aggregated parameters from current, speed, and voltage, displayed large accuracy gaps, 0.69 in FedAvg-KRUM to 0.98 in FedPer-Trimmed Mean, demonstrating how complex feature couplings benefit from both personalization and robust suppression of gradient outliers. Clients 6 and 7, dealing with overlapping signal domains, such as voltage-speed and voltage-time, also showed strong sensitivity to aggregation. They only approached ideal performance (Accuracy > 0.96) under Multi-KRUM and Trimmed Mean, further underscoring the requirement for variance-aware aggregation in non-IID edge environments. Finally, Client 8, designed to capture centroidal shifts through positional tracking, maintained 100% accuracy across all configurations, validating its role as a baseline indicator for network stability and robustness in federated deployment. These individual behaviors establish the foundation for strategy-adaptive model allocation in WAAM deployments, where assigning specific aggregation mechanisms to clients based on sensing modality may enhance overall system resilience and fault localization precision.

5.4. Comparative Convergence Trends

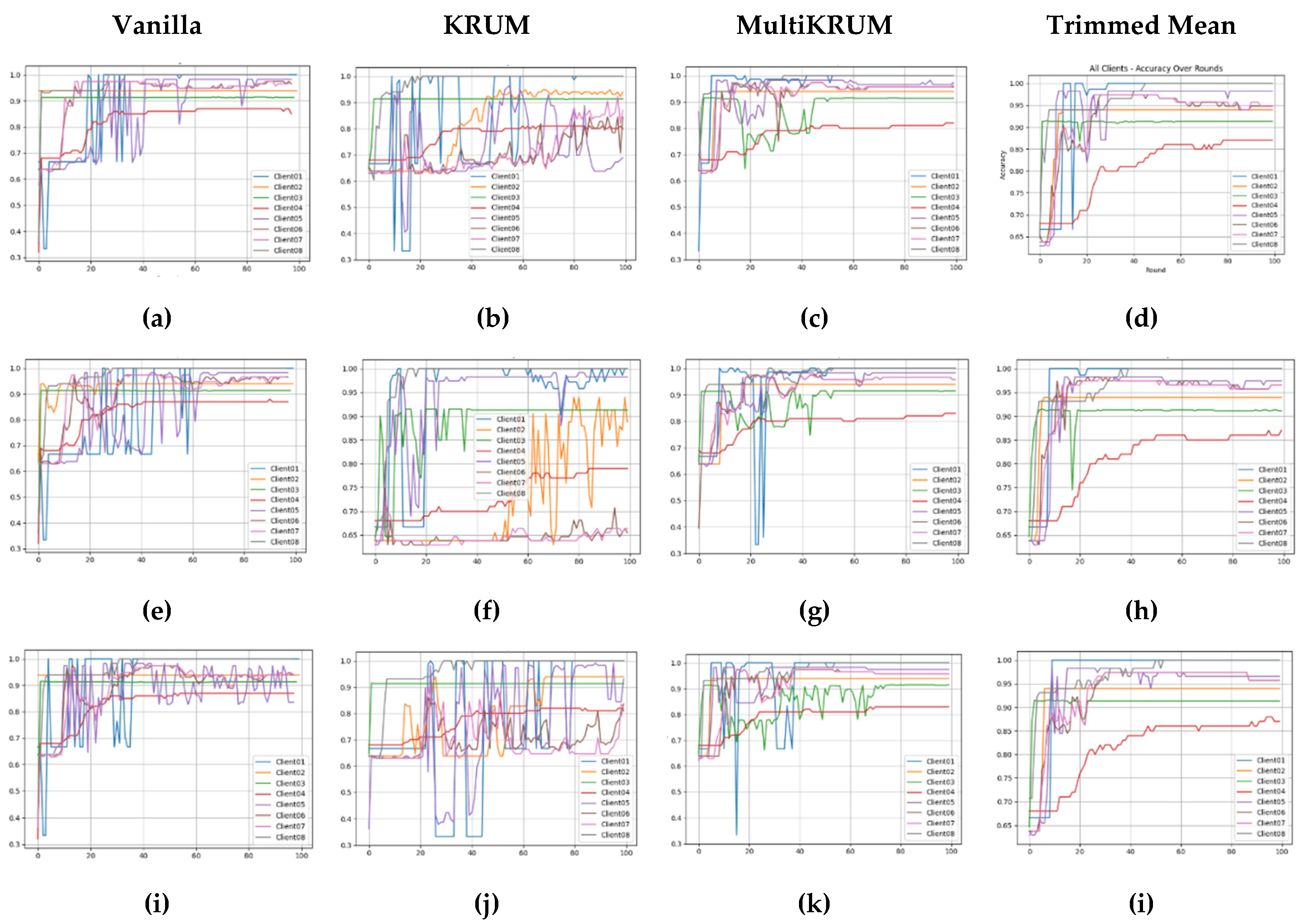

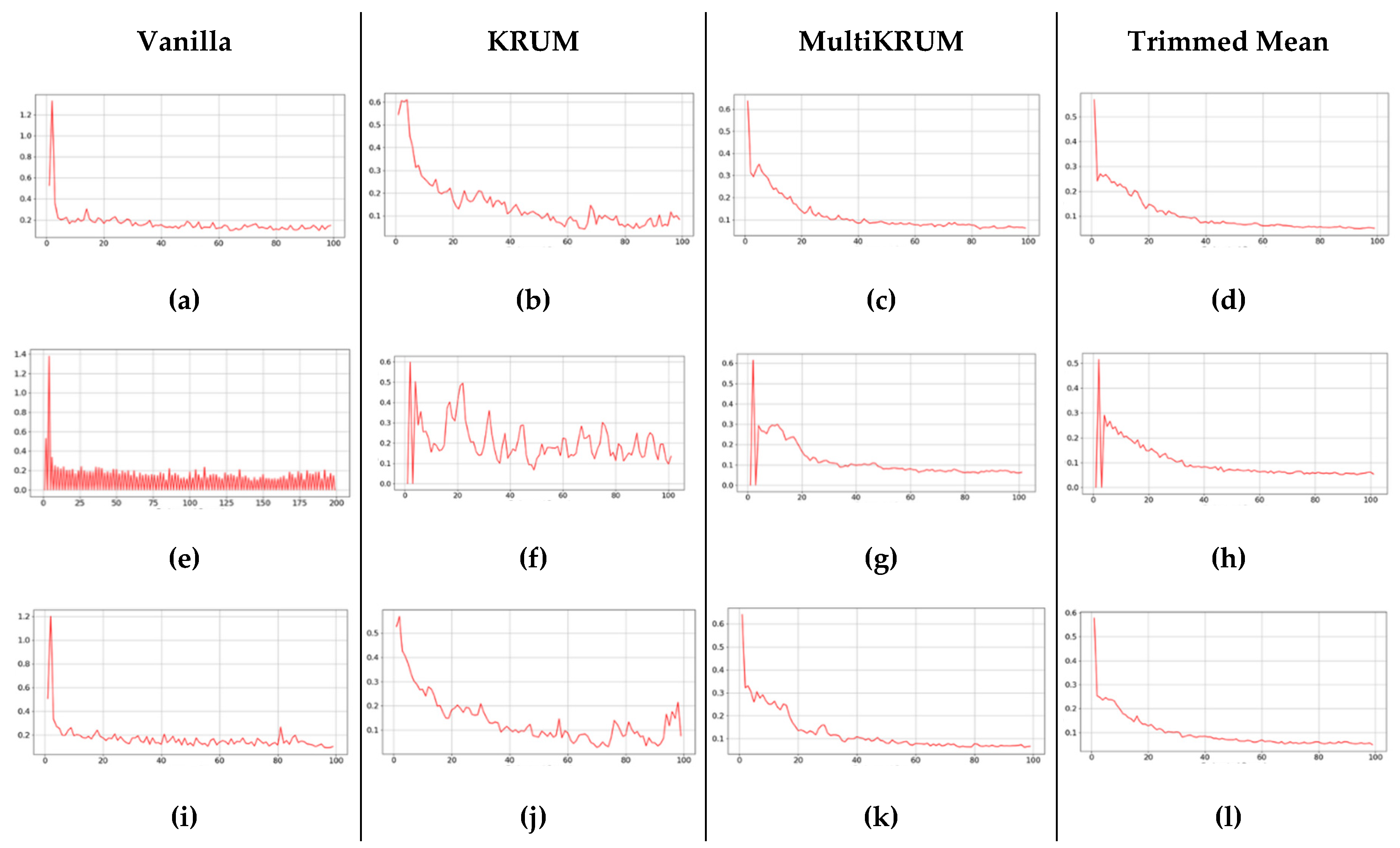

The convergence behavior of FedAvg across different aggregation rules, as shown in

Figure 9, reveals clear distinctions in model stability and responsiveness over federated rounds, as evident in the plotted L2-norm trends of global model updates. Under the FedAvg-Vanilla configuration, the convergence curve exhibits a steep descent in the initial rounds, followed by pronounced oscillations before stabilizing near round 60 (

Figure 9(a)). This instability in the early rounds can be attributed to the aggressive averaging of heterogeneous client updates, which occurs without any gradient correction or outlier rejection, leading to overfitting or oscillatory convergence. In contrast, FedAvg-KRUM (

Figure 9(b)) and FedAvg-Multi-KRUM (

Figure 9(c)) demonstrate more stable convergence trajectories. Specifically, the Multi-KRUM plot maintains a gradual and smooth decline in the L2-norm, reflecting its robustness to Byzantine gradients and stochastic noise by excluding extreme update vectors. The KRUM variant, although initially fluctuating, shows dampened volatility after round 30, indicating resilience against malicious or anomalous client updates. The FedAvg-Trimmed Mean configuration (

Figure 9(d)), however, shows the slowest convergence, with the norm values plateauing prematurely around round 50. This underfitting behavior is likely due to extreme elimination of potentially useful updates when client data distributions are non-IID, resulting in a loss of learning signal. These observations suggest that while FedAvg achieves fast initial convergence, its generalization ability and convergence consistency are strongly influenced by the choice of aggregation rule, particularly under client heterogeneity.

The convergence behavior under the FedPer strategy presents a fundamentally different dynamic compared to FedAvg, primarily due to its personalization mechanism which decouples local and global representations. In the FedPer-Vanilla configuration, the convergence curve exhibits a relatively smooth decline in L2-norm with minor oscillations, as shown in

Figure 9(e). This is indicative of steady synchronization of shared layers while allowing local heads to diverge, thereby reducing the impact of client heterogeneity on global updates. In contrast, FedPer with KRUM aggregation, shown in

Figure 9(f), introduces more pronounced volatility in the initial rounds, with the L2-norm fluctuating sharply up to round 30 before gradually stabilizing. This can be attributed to KRUM’s selective filtering of updates, which becomes less effective when most client updates are already partially personalized, resulting in a conflict between local retention and global alignment. FedPer with Multi-KRUM, depicted in

Figure 9(g), offers improved noise suppression, exhibiting a monotonic decrease with infrequent spikes, which demonstrates enhanced robustness against erratic local gradients. However, in the case of FedPer-Trimmed Mean,

Figure 9(h), the convergence decelerates significantly after round 40, indicating underfitting due to the aggressive exclusion of boundary updates in the presence of already reduced shared model capacity. Overall, FedPer’s convergence trends suggest that while personalization facilitates stable updates in heterogeneous environments, the choice of aggregator modulates the balance between adaptability and synchronization of shared weights.

When examining the convergence behavior of FedProx, a more nuanced stabilization dynamic becomes apparent, particularly in how it manages gradient drift through proximal regularization. As observed in