Introduction

Malignant tumors have long been the focus of extensive research, and recent advances have markedly improved the cure rates of early-stage cancers. Accurate early diagnosis is essential, aided by imaging modalities such as MRI and CT, along with the development of genetic and serological markers. However, in many cases—including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC)—imaging alone does not enable reliable distinction.

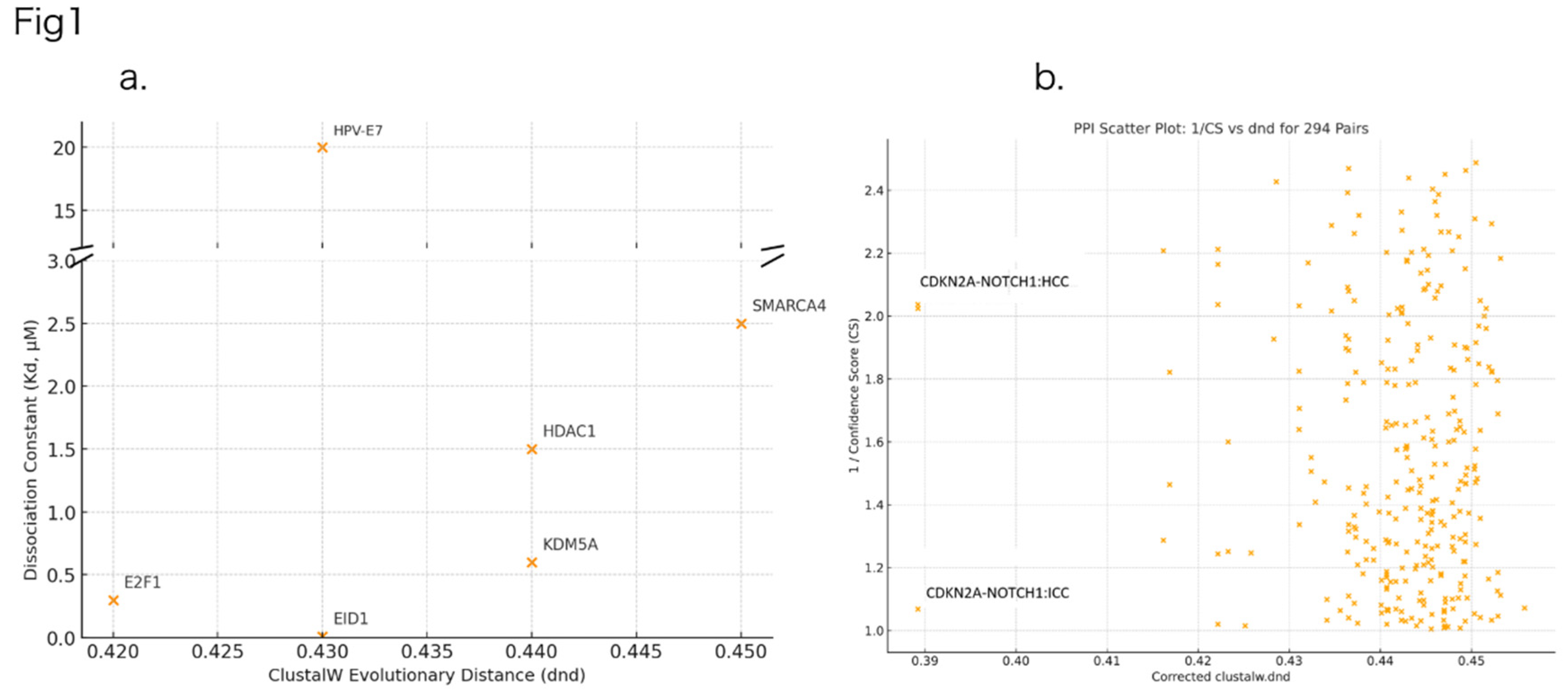

Conventional genetic profiling largely relies on whole genome or exome sequencing to identify mutations within individual genes. Yet in vivo, cellular function often depends not only on individual gene products but also on their protein–protein interactions (PPIs). Motivated by the initial hypothesis that evolutionary distance (ClustalW dnd values) may correlate with affinity (Kd), we began investigating PPI evolution. Our results showed that affinity, rather than sequence divergence, more directly influences interaction potential.

AlphaFold (3) has transformed structural biology by enabling highly accurate prediction of protein structures. Its latest version, AlphaFold3 (AF3), can now model complex PPI interfaces (4). In this study, we apply AF3 to compare PPI networks in HCC and ICC, proposing a new paradigm for cancer diagnosis and classification. Although ClustalW-based evolutionary distances (dnd) are not directly used in AlphaFold’s structural predictions, we incorporated them to compare sequence-based divergence with structure-based affinity. This allowed us to identify PPIs that demonstrate structural gain or loss, independent of sequence similarity—particularly informative in distinguishing ICC from HCC-specific networks.

Materials and Methods

Tools: ClustalW for evolutionary distance (dnd), STRING database for known and predicted PPIs, and AlphaFold3 (Colab or DeepMind server) for structural prediction and affinity scoring.

Dataset: 27,000 cancer-related PPIs from the supplementary Table S2 of Computed Cancer Interactome (5), from which 294 literature-based pairs relevant to HCC and ICC were selected. Since AlphaFold-based structural confidence (CS) is highly dependent on the input amino acid sequences, we utilized canonical UniProt sequences. Database: UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot as of 2025-04-15. Variations in isoforms may affect structural interpretations.

Analyses: Evolutionary distances (ClustalW dnd), structural affinity scoring (CS), volcano plotting of differential PPI interactions, and STRING-based clustering with k-means.

Results

To evaluate the relationship between sequence divergence and structural interaction potential, we first analyzed known Kd values for RB1-binding partners in the context of their evolutionary distances (ClustalW dnd values). As shown in

Figure 1a, the distribution was non-linear, indicating that evolutionary divergence alone does not predict functional affinity. This discrepancy led us to explore whether structure-based affinity scoring might reveal more relevant biological distinctions.

We next selected 294 cancer-related PPI pairs relevant to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) from a cancer-wide interactome database. Each pair was evaluated for evolutionary distance (dnd) and structural affinity (CS). When plotted in two-dimensional space (

Figure 1b), the PPI pairs formed two broad clusters, suggesting underlying differences in the interaction architectures associated with HCC and ICC.

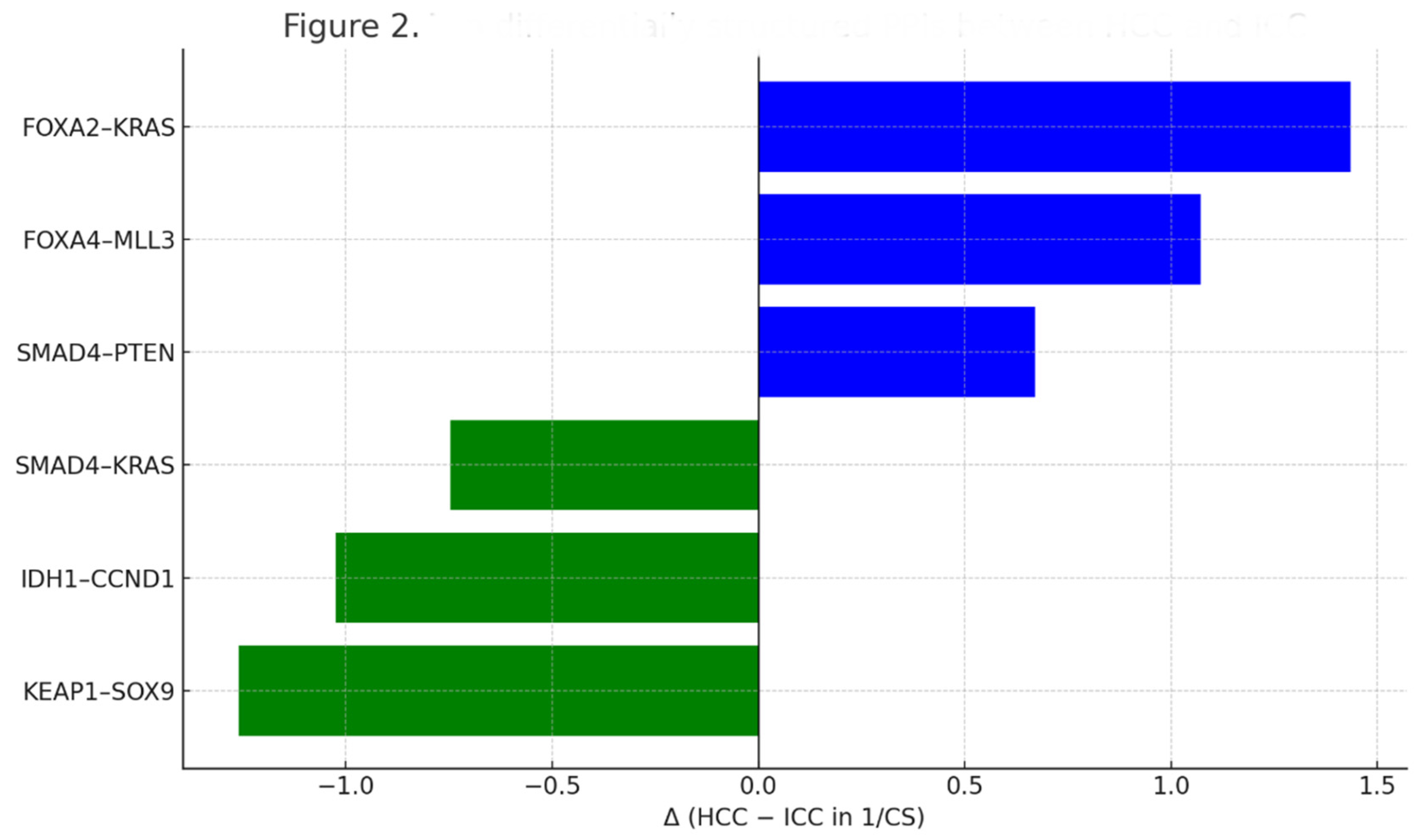

To quantify these differences, we computed the Δ(CS) values for each PPI pair between HCC and ICC and visualized them using a ranked bar plot (

Figure 2). The top structurally divergent PPIs—including RB1–NOTCH1 and SOX9–IDH1—highlighted mechanistically meaningful differences that distinguish the two tumor types.

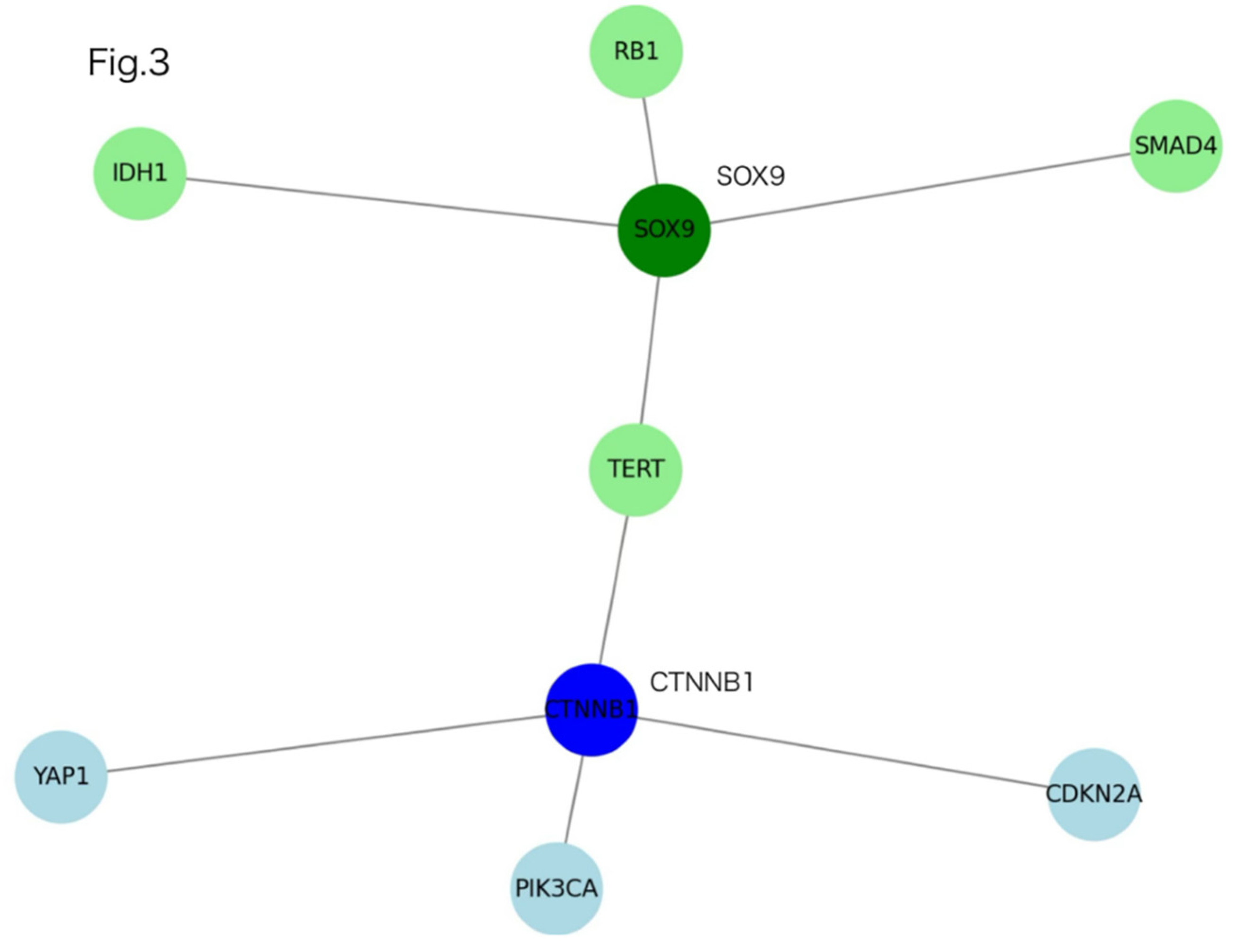

To explore the biological context of these structurally divergent PPIs, we constructed interaction subnetworks centered on key oncogenic drivers identified in the previous step.

Figure 3 illustrates two distinct AlphaFold3-predicted networks, with CTNNB1 serving as the structural hub in HCC and SOX9 in ICC.

Each network revealed a unique set of partner proteins and interaction affinities, reflecting cancer-type-specific structural signaling patterns

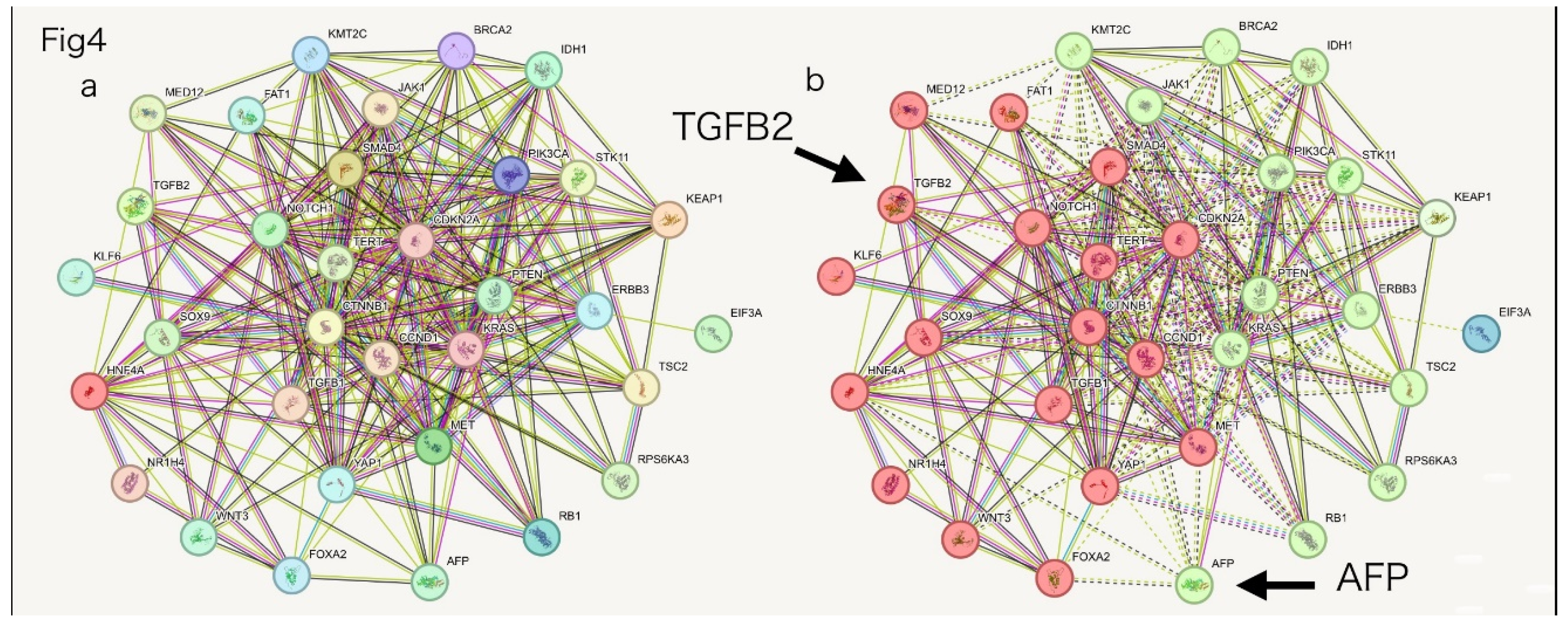

We applied k-means clustering using the STRING platform to the entire 294-PPI dataset, including the clinically established biomarkers AFP (HCC-specific) and TGFB2 (ICC-specific). The resulting network layout (

Figure 4) clearly separated HCC and ICC interactions into distinct functional clusters, with AFP and TGFB2 correctly localized to their respective cancer-specific neighborhoods. This outcome not only validated our structural profiling approach but also highlighted the diagnostic potential of such stratified PPI network analysis.

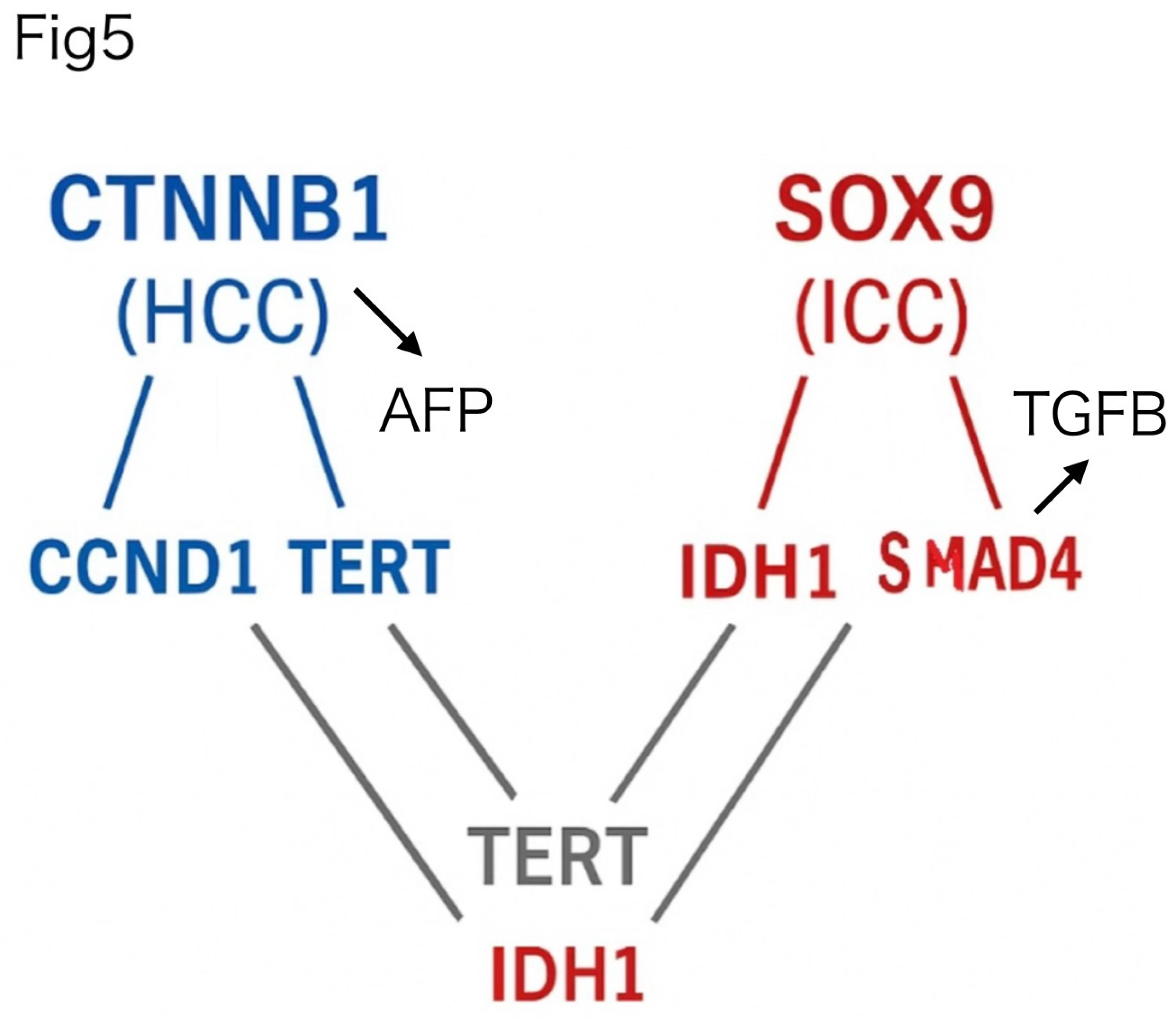

Finally, to evaluate the clinical translatability of these findings, we next focused on a subset of experimentally measurable PPI pairs (

Figure 5), selected based on structural confidence and the availability of commercial ELISA antibodies. In

Figure 5, TERT is displayed in two locations for visual clarity, emphasizing its role as a shared hub connecting both HCC- and ICC-specific subnetworks. This filtered network highlights diagnostically promising interactions that are structurally supported and potentially detectable in blood samples.

Discussion

Perhaps the most striking and unexpected result emerged from the k-means clustering of the full 294-PPI network (

Figure 4b). To our astonishment, the unsupervised clustering algorithm cleanly separated the entire interactome into two distinct modules, aligning precisely with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) profiles. This clear binary division was not an anticipated outcome and underscores the profound structural and functional divergence between the two tumor types. The spontaneous emergence of such classification, without manual supervision, highlights the robustness and biological relevance of our AlphaFold-guided PPI framework. This clustering outcome constitutes one of the most compelling pieces of evidence supporting the diagnostic potential of structure-based interactome stratification.

Importantly, our observation that sequence-based evolutionary distance (dnd) does not reliably predict PPI affinity (Kd) underscores a critical limitation in conventional bioinformatics approaches. While traditionally considered a proxy for functional similarity, evolutionary proximity may mask substantial structural divergence, particularly in cancer-associated PPIs. This result motivated our structure-centric approach using AlphaFold3, which ultimately provided far greater resolution and diagnostic power.

In this study, we demonstrated that AlphaFold3 can accurately predict the structural divergence of protein–protein interactions (PPIs) between hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). Through this, we found that even subtle differences in amino acid sequences—reflected in minimal evolutionary distances (dnd)—can lead to significant differences in complex affinity (CS). This uncoupling suggests that structural alterations not visible in sequence alignments alone may result in altered PPI affinity and potentially oncogenic behavior.

The presence of AFP (HCC-specific) and TGFB2 (ICC-specific) in

Figure 4 reinforces the clinical and functional divergence between the two cancer types. AFP, a well-established marker of hepatocytic origin, and TGFB2, associated with cholangiocytic regeneration and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), occupy distinct molecular neighborhoods in the STRING-derived clustering, supporting the notion that HCC and ICC arise from fundamentally different lineage and differentiation contexts.

Furthermore, AlphaFold3 enabled us to evaluate these divergences at a structural level, beyond sequence-based metrics. Traditional full-length mRNA sequencing and mutational profiling cannot predict the functional impact of “passenger” mutations—mutations traditionally considered neutral (2) due to their lack of protein-coding disruption. Our findings suggest that these mutations may still induce structural shifts in PPI interfaces, altering binding affinity. This opens new avenues for identifying pathogenic drivers in tumors where classical oncogenic mutations are absent.

Moreover, this structure-based approach holds potential diagnostic relevance for cancers of unknown primary (CUP), a group of metastatic cancers where the tissue of origin remains elusive. By comparing patient-derived mutational profiles against cancer-specific PPI structural signatures, our method could aid in CUP classification and guide therapeutic selection.

Although our method is currently limited to in silico predictions based on protein structure and evolutionary distance, future integration of non-coding small RNAs (NCSRs), post-translational modifications, and tumor microenvironmental factors may further refine the prediction of functional PPI affinity. Indeed, we are currently investigating the influence of NCSR binding on PPI modulation using catRAPID-derived RNA-binding propensity (under submission).

This study illustrates a shift in cancer diagnostics—from gene-level alterations to interaction-level structural consequences—and presents a novel diagnostic axis that bridges genetics, protein structure, and systems biology.

Conclusion and Outlook

This study proposes a structure-guided, AlphaFold3-based framework for distinguishing molecular phenotypes of liver cancer subtypes. Such an approach holds promise for broader applications, including cancer of unknown primary (CUP), where structural interactome prediction may enable retrospective origin inference.

Future work will incorporate non-coding RNA and post-translational modification data to further contextualize PPI affinity shifts. This structural interactomics pipeline opens a new dimension of functional diagnosis, potentially transforming cancer precision medicine.

In addition to these structural and evolutionary insights, recent findings from our parallel analysis (Chinami et al., NCSR, 2025, in submission) suggest that non-coding small RNAs (NCSRs) may act as molecular dampers that buffer physiological PPIs. CatRAPID-predicted high NCSR commonality between evolutionarily close partners (e.g., Rb1–E2F1) may facilitate transient, reversible interactions. In contrast, the lack of such RNA interference for divergent oncoproteins like HPV16-E7 allows for unbuffered persistent binding despite high Kd values in vitro. This RNA-mediated regulatory axis may reconcile the apparent paradox between structure-based affinity scores and actual in vivo binding strength, providing a mechanistic framework for oncogenic transformation driven by aberrant PPIs.

While all PPIs illustrated in this study represent structurally stable and high-affinity interactions as predicted by AlphaFold3, these interactions are not necessarily the initial drivers of tumorigenesis. Rather, we propose that the origin of malignancy may occur upstream or in parallel pathways, and the structurally stable PPIs identified here may function as regulatory gateways that determine the phenotypic direction of cancer development. In this view, the PPI networks shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 represent physiological signaling routes, which are secondarily activated or co-opted depending on the initial oncogenic stimuli. Thus, it is not the affinity itself that causes cancer, but the utilization of high-affinity PPIs as directional conduits that shape the phenotypic divergence into HCC or ICC.

References

- Ma L, Wang L, Khatib SA, et al. Single-cell atlas of tumor cell evolution in response to therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;75(6):1397–1408. [CrossRef]

- Wodarz D, Newell AC, Komarova NL. Passenger mutations can accelerate tumour suppressor gene inactivation in cancer evolution. J R Soc Interface. 2018;15(143):20170967. [CrossRef]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596(7873):583–589. [CrossRef]

- Varadi M, Anyango S, Deshpande M, et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D439–D444. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, et al. Computed cancer interactome explains the effects of somatic mutations in cancers. Protein Sci. 2022;31(12):e4479. [CrossRef]

- Dick FA et al. Structural basis for tunable affinity and specificity of LxCxE-dependent protein interactions with the retinoblastoma protein family. Cell Rep. 2018.

Figure 1.

Evolutionary distance versus AlphaFold-based affinity in known and cancer-associated PPIs. a. Structural and biochemical validation of PPI affinity derived from the literature. Protein–protein interactions with the retinoblastoma (Rb) pocket are plotted using ClustalW-based evolutionary distance (dnd, x-axis) and known dissociation constants (Kd, μM, y-axis). While HPV-E7 and EID1 both exhibit close evolutionary similarity to RB1, their binding affinities differ dramatically, emphasizing the decoupling between sequence conservation and functional interaction. Adapted from Dick FA et al., Cell Reports (6). b. Two-dimensional mapping of 294 cancer-related PPI pairs relevant to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). The x-axis represents ClustalW-derived evolutionary distance (dnd) and the y-axis shows the inverse of AlphaFold3-derived confidence scores (CS).

Figure 1.

Evolutionary distance versus AlphaFold-based affinity in known and cancer-associated PPIs. a. Structural and biochemical validation of PPI affinity derived from the literature. Protein–protein interactions with the retinoblastoma (Rb) pocket are plotted using ClustalW-based evolutionary distance (dnd, x-axis) and known dissociation constants (Kd, μM, y-axis). While HPV-E7 and EID1 both exhibit close evolutionary similarity to RB1, their binding affinities differ dramatically, emphasizing the decoupling between sequence conservation and functional interaction. Adapted from Dick FA et al., Cell Reports (6). b. Two-dimensional mapping of 294 cancer-related PPI pairs relevant to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC). The x-axis represents ClustalW-derived evolutionary distance (dnd) and the y-axis shows the inverse of AlphaFold3-derived confidence scores (CS).

Figure 2.

Ranked bar plot of Δ(CS) values between HCC and ICC. This bar graph highlights the top 10 protein–protein interaction pairs showing the largest structural divergence based on AlphaFold3-derived inverse confidence scores (CS). Blue bars indicate interactions enriched in HCC; green bars, in ICC. This ranking provides a clear visualization of the most diagnostically relevant PPIs distinguishing the two cancer types.

Figure 2.

Ranked bar plot of Δ(CS) values between HCC and ICC. This bar graph highlights the top 10 protein–protein interaction pairs showing the largest structural divergence based on AlphaFold3-derived inverse confidence scores (CS). Blue bars indicate interactions enriched in HCC; green bars, in ICC. This ranking provides a clear visualization of the most diagnostically relevant PPIs distinguishing the two cancer types.

Figure 3.

ICC-specific and HCC-specific PPI subnetworks centered on SOX9 and CTNNB1. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks derived from AlphaFold3 structural predictions reveal distinct hubs in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Top cluster (green): SOX9 interacts with ICC-associated partners (IDH1, RB1, SMAD4, and TERT). Bottom cluster (blue): CTNNB1 connects to HCC-associated partners (PIK3CA, CDKN2A, YAP1, and TERT). These two subnetworks illustrate the divergent structural signaling axes characteristic of ICC and HCC.

Figure 3.

ICC-specific and HCC-specific PPI subnetworks centered on SOX9 and CTNNB1. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks derived from AlphaFold3 structural predictions reveal distinct hubs in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Top cluster (green): SOX9 interacts with ICC-associated partners (IDH1, RB1, SMAD4, and TERT). Bottom cluster (blue): CTNNB1 connects to HCC-associated partners (PIK3CA, CDKN2A, YAP1, and TERT). These two subnetworks illustrate the divergent structural signaling axes characteristic of ICC and HCC.

Figure 4.

Global clustering of HCC- and ICC-associated PPI networks. a. A STRING-based PPI network of 294 cancer-associated proteins, integrated with two key biomarkers, AFP and TGFB2. Central hubs such as CTNNB1, SOX9, CDKN2A, TERT, and KRAS are evident within the interconnected core. b. K-means clustering of the same network reveals partitioning into HCC-enriched (green) and ICC-enriched (red) modules. Notably, AFP—a hallmark serum marker for HCC—clusters within the green module, while TGFB2—an EMT-related factor associated with ICC—is embedded in the red module. These spatial patterns reinforce the structural divergence between HCC and ICC and validate the proposed classification model based on interaction affinity and network topology.

Figure 4.

Global clustering of HCC- and ICC-associated PPI networks. a. A STRING-based PPI network of 294 cancer-associated proteins, integrated with two key biomarkers, AFP and TGFB2. Central hubs such as CTNNB1, SOX9, CDKN2A, TERT, and KRAS are evident within the interconnected core. b. K-means clustering of the same network reveals partitioning into HCC-enriched (green) and ICC-enriched (red) modules. Notably, AFP—a hallmark serum marker for HCC—clusters within the green module, while TGFB2—an EMT-related factor associated with ICC—is embedded in the red module. These spatial patterns reinforce the structural divergence between HCC and ICC and validate the proposed classification model based on interaction affinity and network topology.

Figure 5.

Structural PPI clustering distinguishes HCC and ICC subtype networks. The left panel shows the HCC-dominant network centered on CTNNB1, highlighting interactions with CCND1, TERT, and CDKN2A, each exhibiting strong AlphaFold-predicted binding affinities. In contrast, the right panel displays the ICC-dominant network centered on SOX9, showing key interactions with IDH1, RB1, SMAD4, and TERT. Network topology and structural scores (CS) reflect tumor-specific interaction clustering, revealing compact architecture in HCC and more distributed interactions in ICC. TERT appears twice in the diagram for clarity—once as a shared central node and again in the lower portion to illustrate direct connections with both HCC- and ICC-associated partners. All instances represent the same gene product.

Figure 5.

Structural PPI clustering distinguishes HCC and ICC subtype networks. The left panel shows the HCC-dominant network centered on CTNNB1, highlighting interactions with CCND1, TERT, and CDKN2A, each exhibiting strong AlphaFold-predicted binding affinities. In contrast, the right panel displays the ICC-dominant network centered on SOX9, showing key interactions with IDH1, RB1, SMAD4, and TERT. Network topology and structural scores (CS) reflect tumor-specific interaction clustering, revealing compact architecture in HCC and more distributed interactions in ICC. TERT appears twice in the diagram for clarity—once as a shared central node and again in the lower portion to illustrate direct connections with both HCC- and ICC-associated partners. All instances represent the same gene product.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).