Submitted:

27 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

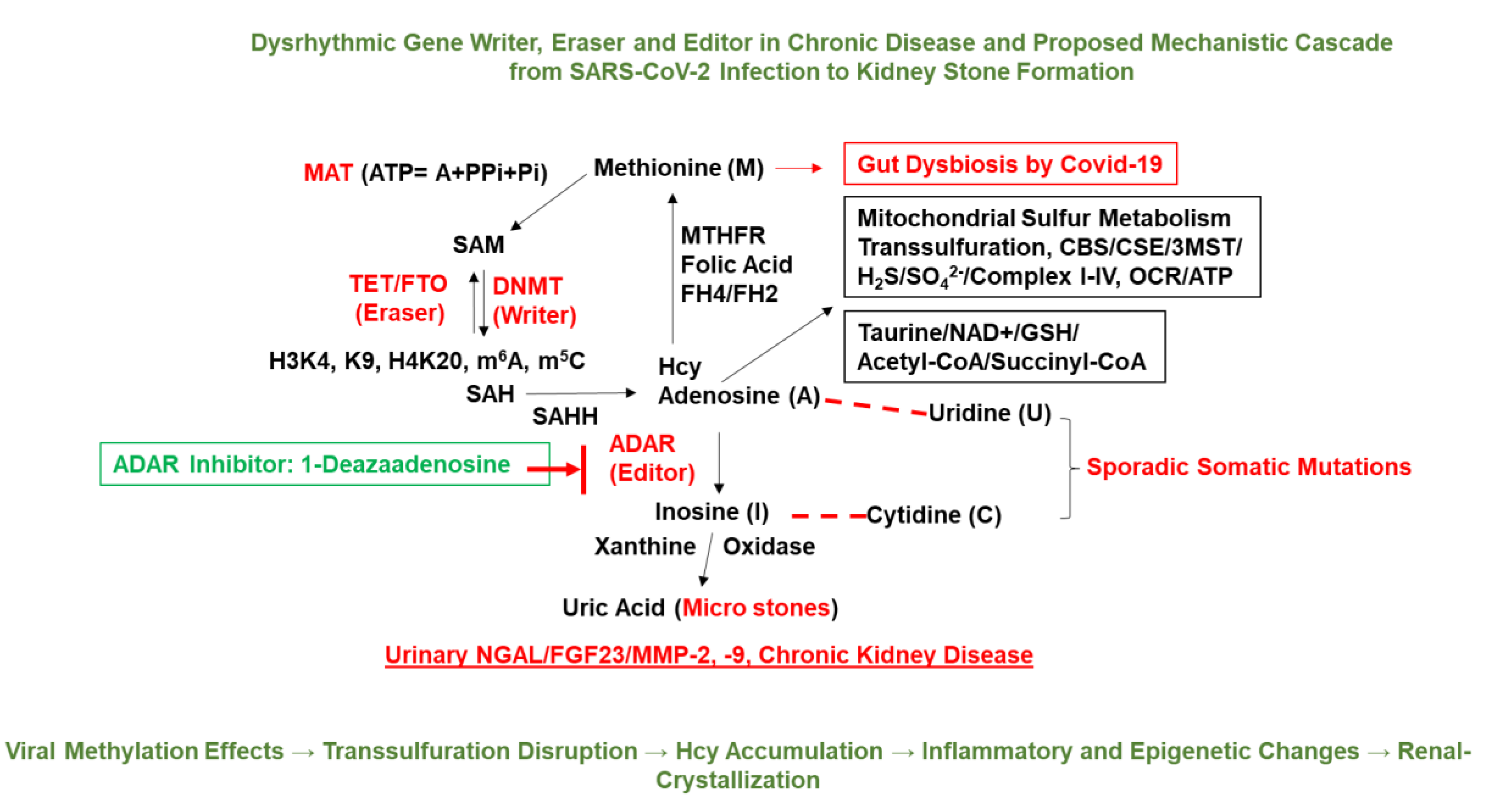

2. Epigenetics of COVID-19 Infection and KSD

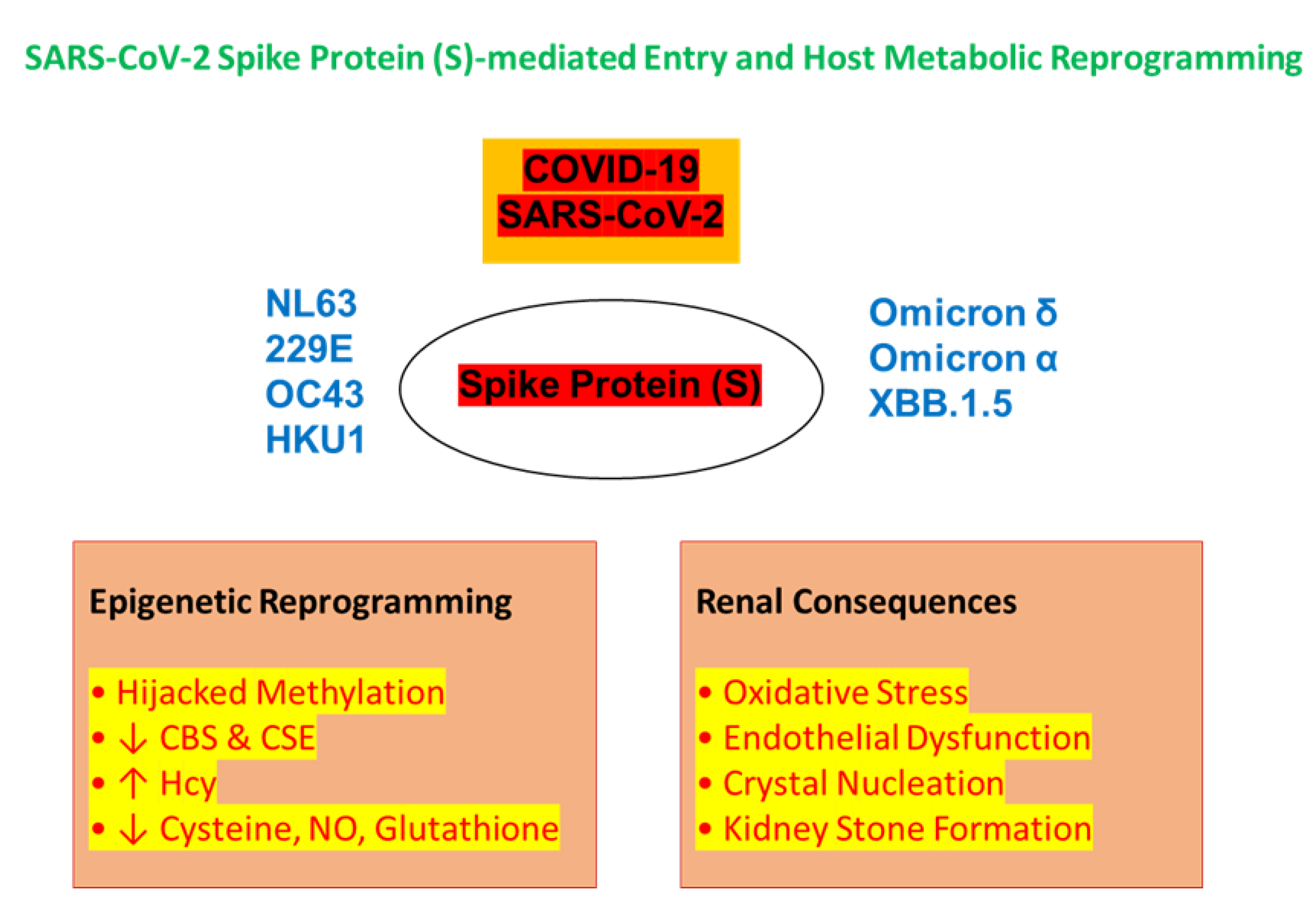

2.1. Epigenetic Methylation Dysregulation and SARS-CoV-2

2.2. Hcy and Sulfur Metabolism: Implications for KSD

2.3. Immune-Mediated Endothelial Injury and Fibrosis

2.4. Dysfunction and miRNA-Mediated Reprogramming

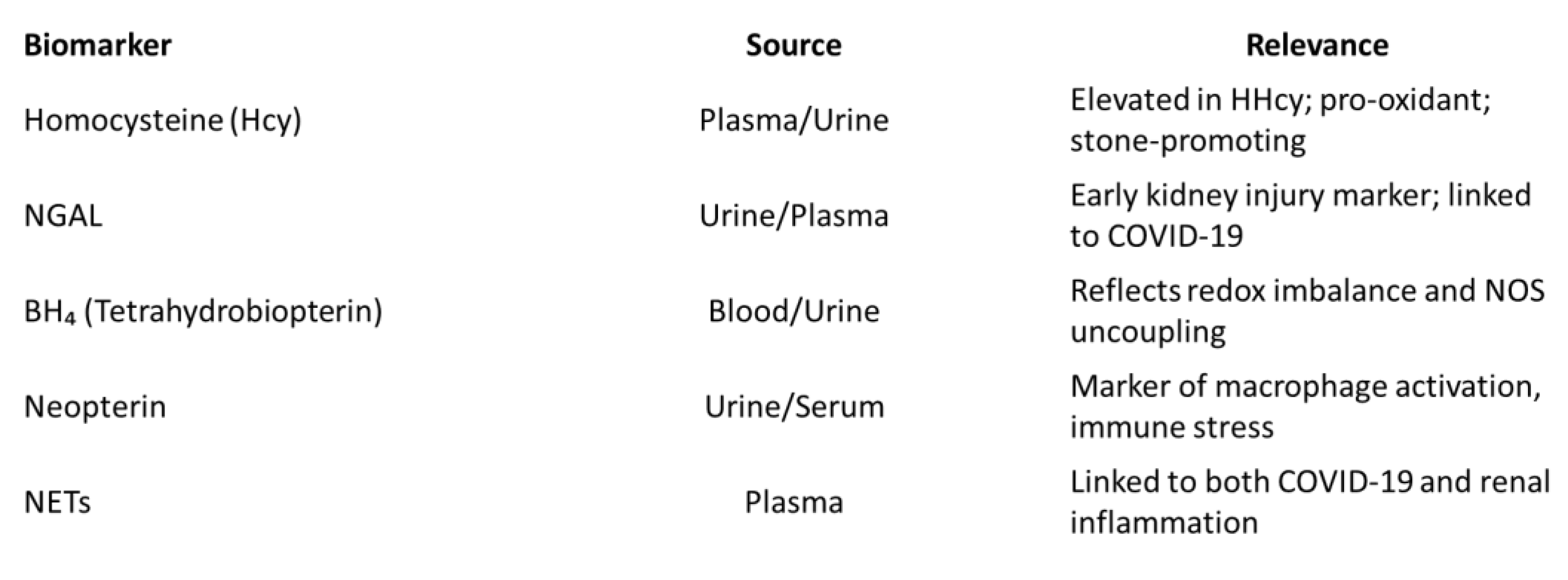

2.5. From Biomarkers to Therapeutics: Neopterin and iNOS

2.6. Epigenetics, Viral Persistence, and Long-Term Risk of KSD

3. Kidney Stones

4. Underlying Mechanisms Linking COVID-19 Infection to Kidney Stone Formation

4.1. Mitochondrial Sulfur Metabolism and Hcy Accumulation

4.2. Transsulfuration Pathway Disruption and Epigenetic Consequences

4.3. COVID-19-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction

4.4. Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress

4.5. Immune Activation, Macrophages, and NETosis

4.6. Tubular Transport Dysfunction and Osmotic Stress

4.7. Role of Gut Microbiome and Uremic Toxins

4.8. Systemic Hypoxia and Dehydration

5. Potential Limitations and Future Directions

5.1. Animal Models

5.2. Epigenetic Analyses

5.3. Clinical Biomarker Studies

5.4. Gut Microbiome Sequencing

5.5. Therapeutic Trials

5.6. Sex-Differentiated Renal Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin de Francisco Á, Fernández Fresnedo G: Long COVID-19 renal disease: A present medical need for nephrology. Nefrologia (Engl Ed) 2023, 43, 1–5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffl H, Lang SM: Long-term interplay between COVID-19 and chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol 2023, 55, 1977–1984. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su H, Yang M, Wan C, Yi LX, Tang F, Zhu HY, Yi F, Yang HC, Fogo AB, Nie X, Zhang C: Renal histopathological analysis of 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int 2020, 98, 219–227. [CrossRef]

- Kissling S, Rotman S, Gerber C, Halfon M, Lamoth F, Comte D, Lhopitallier L, Sadallah S, Fakhouri F: Collapsing glomerulopathy in a COVID-19 patient. Kidney Int 2020, 98, 228–231. [CrossRef]

- Caceres PS, Savickas G, Murray SL, Umanath K, Uduman J, Yee J, Liao TD, Bolin S, Levin AM, Khan MN, Sarkar S, Fitzgerald J, Maskey D, Ormsby AH, Sharma Y, Ortiz PA: High SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Urine Sediment Correlates with Acute Kidney Injury and Poor COVID-19 Outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021, 32, 2517–2528.

- Tyagi SC, Singh M: Multi-organ damage by covid-19: congestive (cardio-pulmonary) heart failure, and blood-heart barrier leakage. Mol Cell Biochem 2021, 476, 1891–1895. [CrossRef]

- Homme RP, George AK, Singh M, Smolenkova I, Zheng Y, Pushpakumar S, Tyagi SC: Mechanism of Blood-Heart-Barrier Leakage: Implications for COVID-19 Induced Cardiovascular Injury. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22.

- Gul M, Kaynar M, Yildiz M, Batur AF, Akand M, Kilic O, Goktas S: The Increased Risk of Complicated Ureteral Stones in the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic. J Endourol 2020, 34, 882–886. [CrossRef]

- Spooner J, Masoumi-Ravandi K, MacNevin W, Ilie G, Skinner T, Powers AL: Septic and febrile kidney stone presentations during the COVID-19 pandemic What is the effect of reduced access to care during pandemic restrictions? Can Urol Assoc J 2024, 18, E19–e25.

- Kasiri H, Moradimajd P, Samaee H, Ghazaeian M: The Increased Risk of Renal Stones in Patients With COVID-19 Infection. Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research 2022, 8, 333–340. [CrossRef]

- Carollo C, Benfante A, Sorce A, Montalbano K, Cirafici E, Calandra L, Geraci G, Mulè G, Scichilone N: Predictive Biomarkers of Acute Kidney Injury in COVID-19: Distinct Inflammatory Pathways in Patients with and Without Pre-Existing Chronic Kidney Disease. Life (Basel) 2025, 15.

- Zhang W, Liu L, Xiao X, Zhou H, Peng Z, Wang W, Huang L, Xie Y, Xu H, Tao L, Nie W, Yuan X, Liu F, Yuan Q: Identification of common molecular signatures of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its influence on acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 961642. [CrossRef]

- Marques F, Gameiro J, Oliveira J, Fonseca JA, Duarte I, Bernardo J, Branco C, Costa C, Carreiro C, Braz S, Lopes JA: Acute Kidney Disease and Mortality in Acute Kidney Injury Patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med 2021, 10.

- Kemble JP, Liaw CW, Alamiri JM, Ungerer GN, Potretzke AM, Koo K: Public Interest in Vitamin C Supplementation During the COVID-19 Pandemic as a Potential Risk for Oxalate Nephrolithiasis. Cureus 2025, 17, e79452.

- Abhishek A, Benita S, Kumari M, Ganesan D, Paul E, Sasikumar P, Mahesh A, Yuvaraj S, Ramprasath T, Selvam GS: Molecular analysis of oxalate-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated apoptosis in the pathogenesis of kidney stone disease. Journal of physiology and biochemistry 2017, 73, 561–573. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur M, Varanasi R, Nayak D, Tandon S, Agrawal V, Tandon C: Molecular insights into cell signaling pathways in kidney stone formation. Urolithiasis 2025, 53, 30. [CrossRef]

- Sbodio JI, Snyder SH, Paul BD: Regulators of the transsulfuration pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 583–593. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Berisa M, Schwörer S, Qin W, Cross JR, Thompson CB: Transsulfuration Activity Can Support Cell Growth upon Extracellular Cysteine Limitation. Cell Metab 2019, 30, 865–876.e5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitvitsky V, Thomas M, Ghorpade A, Gendelman HE, Banerjee R: A functional transsulfuration pathway in the brain links to glutathione homeostasis. The Journal of biological chemistry 2006, 281, 35785–35793. [CrossRef]

- Mosharov E, Cranford MR, Banerjee R: The quantitatively important relationship between homocysteine metabolism and glutathione synthesis by the transsulfuration pathway and its regulation by redox changes. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 13005–13011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perła-Kaján J, Jakubowski H: COVID-19 and One-Carbon Metabolism. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23.

- Scammahorn JJ, Nguyen ITN, Bos EM, Van Goor H, Joles JA: Fighting Oxidative Stress with Sulfur: Hydrogen Sulfide in the Renal and Cardiovascular Systems. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10.

- Chen CJ, Cheng MC, Hsu CN, Tain YL: Sulfur-Containing Amino Acids, Hydrogen Sulfide, and Sulfur Compounds on Kidney Health and Disease. Metabolites 2023, 13.

- Kabil O, Banerjee R: Enzymology of H2S biogenesis, decay and signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, 20, 770–782. [CrossRef]

- Tavasoli S, Borumandnia N, Basiri A, Taheri M: Effects of COVID-19 pandemics on urinary metabolites in kidney stone patients: our kidney stone prevention clinic experience. Environ Health Prev Med 2021, 26, 112. [CrossRef]

- Chen IW, Chang LC, Ho CN, Wu JY, Tsai YW, Lin CM, Chang YJ, Hung KC: Association between COVID-19 and the development of chronic kidney disease in patients without initial acute kidney injury. Scientific reports 2025, 15, 10924.

- Lang SM, Schiffl H: Long-term renal consequences of COVID-19. Emerging evidence and unanswered questions. Emerging evidence and unanswered questions. Int Urol Nephrol 2025.

- du Preez HN, Lin J, Maguire GEM, Aldous C, Kruger HG: COVID-19 vaccine adverse events: Evaluating the pathophysiology with an emphasis on sulfur metabolism and endotheliopathy. Eur J Clin Invest 2024, 54, e14296. [CrossRef]

- du Preez HN, Aldous C, Hayden MR, Kruger HG, Lin J: Pathogenesis of COVID-19 described through the lens of an undersulfated and degraded epithelial and endothelial glycocalyx. Faseb j 2022, 36, e22052.

- Liu Q, Wang H, Zhang H, Sui L, Li L, Xu W, Du S, Hao P, Jiang Y, Chen J, Qu X, Tian M, Zhao Y, Guo X, Wang X, Song W, Song G, Wei Z, Hou Z, Wang G, Sun M, Li X, Lu H, Zhuang X, Jin N, Zhao Y, Li C, Liao M: The global succinylation of SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals drug targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022, 119, e2123065119.

- Raj ST, Bruce AW, Anbalagan M, Srinivasan H, Chinnappan S, Rajagopal M, Khanna K, Chandramoorthy HC, Mani RR: COVID-19 influenced gut dysbiosis, post-acute sequelae, immune regulation, and therapeutic regimens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1384939.

- An L, Wu W, Li S, Lai Y, Chen D, He Z, Chang Z, Xu P, Huang Y, Lei M, Jiang Z, Zeng T, Sun X, Sun X, Duan X, Wu W: Escherichia coli Aggravates Calcium Oxalate Stone Formation via PPK1/Flagellin-Mediated Renal Oxidative Injury and Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 9949697. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Xue X, Meng G, He C, Tong L, Lai Y: The roles of bacteria on urolithiasis progression and associated compounds. Biochem Pharmacol 2025, 237, 116958.

- Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, Shan S, Zhou H, Fan S, Zhang Q, Shi X, Wang Q, Zhang L, Wang X: Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220. [CrossRef]

- Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, Geng Q, Auerbach A, Li F: Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 581, 221–224. [CrossRef]

- Chen TH, Jeng TH, Lee MY, Wang HC, Tsai KF, Chou CK: Viral mitochondriopathy in COVID-19. Redox Biol 2025, 85, 103766.

- Diao B, Wang C, Wang R, Feng Z, Zhang J, Yang H, Tan Y, Wang H, Wang C, Liu L, Liu Y, Liu Y, Wang G, Yuan Z, Hou X, Ren L, Wu Y, Chen Y: Human kidney is a target for novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2506. [CrossRef]

- Bhat S, Rishi P, Chadha VD: Understanding the epigenetic mechanisms in SARS CoV-2 infection and potential therapeutic approaches. Virus Res 2022, 318, 198853. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath S, Perikala V, Jena AB, Dandapat J: Factors regulating dynamics of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2), the gateway of SARS-CoV-2: Epigenetic modifications and therapeutic interventions by epidrugs. Biomed Pharmacother 2021, 143, 112095.

- Beacon TH, Delcuve GP, Davie JR: Epigenetic regulation of ACE2, the receptor of the SARS-CoV-2 virus(1). Genome 2021, 64, 386–399. [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Pushpakumar S, Bard N, Zheng Y, Homme RP, Mokshagundam SPL, Tyagi SC: Simulation of COVID-19 symptoms in a genetically engineered mouse model: implications for the long haulers. Mol Cell Biochem 2023, 478, 103–119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponti G, Roli L, Oliva G, Manfredini M, Trenti T, Kaleci S, Iannella R, Balzano B, Coppola A, Fiorentino G, Ozben T, Paoli VD, Debbia D, De Santis E, Pecoraro V, Melegari A, Sansone MR, Lugara M, Tomasi A: Homocysteine (Hcy) assessment to predict outcomes of hospitalized Covid-19 patients: a multicenter study on 313 Covid-19 patients. Clin Chem Lab Med 2021, 59, e354–e7.

- Eslamifar Z, Behzadifard M, Zare E: Investigation of homocysteine, D-dimer and platelet count levels as potential predictors of thrombosis risk in COVID-19 patients. Mol Cell Biochem 2025, 480, 439–444. [CrossRef]

- Ponti G, Ruini C, Tomasi A: Homocysteine as a potential predictor of cardiovascular risk in patients with COVID-19. Med Hypotheses 2020, 143, 109859. [CrossRef]

- Martins MC, Meyers AA, Whalley NA, Rodgers AL: Cystine: a promoter of the growth and aggregation of calcium oxalate crystals in normal undiluted human urine. J Urol 2002, 167, 317–321. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Qiu B, Lu H, Lai Y, Liu J, Luo J, Zhu F, Hu Z, Zhou M, Tian J, Zhou Z, Yu S, Yi F, Nie J: Hyperhomocysteinemia Accelerates Acute Kidney Injury to Chronic Kidney Disease Progression by Downregulating Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression. Antioxid Redox Signal 2019, 30, 1635–1650. [CrossRef]

- Khezri MR, Ghasemnejad-Berenji M: Neurological effects of elevated levels of angiotensin II in COVID-19 patients. Hum Cell 2021, 34, 1941–1942. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang K, Gheblawi M, Nikhanj A, Munan M, MacIntyre E, O'Neil C, Poglitsch M, Colombo D, Del Nonno F, Kassiri Z, Sligl W, Oudit GY: Dysregulation of ACE (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme)-2 and Renin-Angiotensin Peptides in SARS-CoV-2 Mediated Mortality and End-Organ Injuries. Hypertension 2022, 79, 365–378.

- Caputo I, Caroccia B, Frasson I, Poggio E, Zamberlan S, Morpurgo M, Seccia TM, Calì T, Brini M, Richter SN, Rossi GP: Angiotensin II Promotes SARS-CoV-2 Infection via Upregulation of ACE2 in Human Bronchial Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23.

- Lip S, Tran TQB, Hanna R, Nichol S, Guzik TJ, Delles C, McClure J, McCallum L, Touyz RM, Berry C, Padmanabhan S: Long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on blood vessels and blood pressure - LOCHINVAR. J Hypertens 2025, 43, 1057–1065. [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran B, Grimm D, Krüger M, Kopp S, Infanger M, Wehland M: SARS-CoV-2 and hypertension. Physiol Rep 2021, 9, e14800.

- Singh M, Pushpakumar S, Zheng Y, Smolenkova I, Akinterinwa OE, Luulay B, Tyagi SC: Novel mechanism of the COVID-19 associated coagulopathy (CAC) and vascular thromboembolism. Npj viruses 2023, 1.

- Belen Apak FB, Yuce G, Topcu DI, Gultekingil A, Felek YE, Sencelikel T: Coagulopathy is Initiated with Endothelial Dysfunction and Disrupted Fibrinolysis in Patients with COVID-19 Disease. Indian J Clin Biochem 2023, 38, 220–230.

- Ward SE, Fogarty H, Karampini E, Lavin M, Schneppenheim S, Dittmer R, Morrin H, Glavey S, Ni Cheallaigh C, Bergin C, Martin-Loeches I, Mallon PW, Curley GF, Baker RI, Budde U, O'Sullivan JM, O'Donnell JS: ADAMTS13 regulation of VWF multimer distribution in severe COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 2021, 19, 1914–1921.

- Favaloro EJ, Henry BM, Lippi G: Increased VWF and Decreased ADAMTS-13 in COVID-19: Creating a Milieu for (Micro)Thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost 2021, 47, 400–418. [CrossRef]

- Chau CW, To A, Au-Yeung RKH, Tang K, Xiang Y, Ruan D, Zhang L, Wong H, Zhang S, Au MT, Chung S, Song E, Choi DH, Liu P, Yuan S, Wen C, Sugimura R: SARS-CoV-2 infection activates inflammatory macrophages in vascular immune organoids. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 8781. [CrossRef]

- Hönzke K, Obermayer B, Mache C, Fatykhova D, Kessler M, Dökel S, Wyler E, Baumgardt M, Löwa A, Hoffmann K, Graff P, Schulze J, Mieth M, Hellwig K, Demir Z, Biere B, Brunotte L, Mecate-Zambrano A, Bushe J, Dohmen M, Hinze C, Elezkurtaj S, Tönnies M, Bauer TT, Eggeling S, Tran HL, Schneider P, Neudecker J, Rückert JC, Schmidt-Ott KM, Busch J, Klauschen F, Horst D, Radbruch H, Radke J, Heppner F, Corman VM, Niemeyer D, Müller MA, Goffinet C, Mothes R, Pascual-Reguant A, Hauser AE, Beule D, Landthaler M, Ludwig S, Suttorp N, Witzenrath M, Gruber AD, Drosten C, Sander LE, Wolff T, Hippenstiel S, Hocke AC: Human lungs show limited permissiveness for SARS-CoV-2 due to scarce ACE2 levels but virus-induced expansion of inflammatory macrophages. Eur Respir J 2022, 60.

- Pode Shakked N, de Oliveira MHS, Cheruiyot I, Benoit JL, Plebani M, Lippi G, Benoit SW, Henry BM: Early prediction of COVID-19-associated acute kidney injury: Are serum NGAL and serum Cystatin C levels better than serum creatinine? Clin Biochem 2022, 102, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kim IS, Kim DH, Lee HW, Kim SG, Kim YK, Kim JK: Role of increased neutrophil extracellular trap formation on acute kidney injury in COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1122510. [CrossRef]

- Henry BM, de Oliveira MHS, Cheruiyot I, Benoit J, Rose J, Favaloro EJ, Lippi G, Benoit S, Pode Shakked N: Cell-Free DNA, Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and Endothelial Injury in Coronavirus Disease 2019- (COVID-19-) Associated Acute Kidney Injury. Mediators Inflamm 2022, 2022, 9339411.

- Gemmati D, Bramanti B, Serino ML, Secchiero P, Zauli G, Tisato V: COVID-19 and Individual Genetic Susceptibility/Receptivity: Role of ACE1/ACE2 Genes, Immunity, Inflammation and Coagulation Might the Double X-chromosome in Females Be Protective against SARS-CoV-2 Compared to the Single X-Chromosome in Males? Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21.

- Chanana N, Palmo T, Sharma K, Kumar R, Graham BB, Pasha Q: Sex-derived attributes contributing to SARS-CoV-2 mortality. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2020, 319, E562–e7. [CrossRef]

- Langelueddecke C, Roussa E, Fenton RA, Wolff NA, Lee WK, Thévenod F: Lipocalin-2 (24p3/neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL)) receptor is expressed in distal nephron and mediates protein endocytosis. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 159–169. [CrossRef]

- Salomão R, Assis V, de Sousa Neto IV, Petriz B, Babault N, Durigan JLQ, de Cássia Marqueti R: Involvement of Matrix Metalloproteinases in COVID-19: Molecular Targets, Mechanisms, and Insights for Therapeutic Interventions. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12.

- Mobasheri L, Nasirpour MH, Masoumi E, Azarnaminy AF, Jafari M, Esmaeili SA: SARS-CoV-2 triggering autoimmune diseases. Cytokine 2022, 154, 155873. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galipeau Y, Cooper C, Langlois MA: Autoantibodies in COVID-19: implications for disease severity and clinical outcomes. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1509289.

- Brinkmann M, Traby L, Kussmann M, Weiss-Tessbach M, Buchtele N, Staudinger T, Gaidoschik E, Perkmann T, Haslacher H, Ratzinger F, Pickl WF, El-Gedawi K, Feichter M, Gelpi E, Höftberger R, Quehenberger P, Marculescu R, Mrak D, Kastrati K, Lechner-Radner H, Sieghart D, Aletaha D, Winkler S, Bonelli M, Göschl L: Autoantibody development is associated with clinical severity of COVID-19: A cohort study. Clin Immunol 2025, 274, 110471.

- Jansen J, Reimer KC, Nagai JS, Varghese FS, Overheul GJ, de Beer M, Roverts R, Daviran D, Fermin LAS, Willemsen B, Beukenboom M, Djudjaj S, von Stillfried S, van Eijk LE, Mastik M, Bulthuis M, Dunnen WD, van Goor H, Hillebrands JL, Triana SH, Alexandrov T, Timm MC, van den Berge BT, van den Broek M, Nlandu Q, Heijnert J, Bindels EMJ, Hoogenboezem RM, Mooren F, Kuppe C, Miesen P, Grünberg K, Ijzermans T, Steenbergen EJ, Czogalla J, Schreuder MF, Sommerdijk N, Akiva A, Boor P, Puelles VG, Floege J, Huber TB, van Rij RP, Costa IG, Schneider RK, Smeets B, Kramann R: SARS-CoV-2 infects the human kidney and drives fibrosis in kidney organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 217–231.e8.

- Reiser J, Spear R, Luo S: SARS-CoV-2 pirates the kidneys: A scar(y) story. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 352–354. [CrossRef]

- Larrue R, Fellah S, Van der Hauwaert C, Hennino MF, Perrais M, Lionet A, Glowacki F, Pottier N, Cauffiez C: The Versatile Role of miR-21 in Renal Homeostasis and Diseases. Cells 2022, 11.

- McDonald JT, Enguita FJ, Taylor D, Griffin RJ, Priebe W, Emmett MR, Sajadi MM, Harris AD, Clement J, Dybas JM, Aykin-Burns N, Guarnieri JW, Singh LN, Grabham P, Baylin SB, Yousey A, Pearson AN, Corry PM, Saravia-Butler A, Aunins TR, Sharma S, Nagpal P, Meydan C, Foox J, Mozsary C, Cerqueira B, Zaksas V, Singh U, Wurtele ES, Costes SV, Davanzo GG, Galeano D, Paccanaro A, Meinig SL, Hagan RS, Bowman NM, Wolfgang MC, Altinok S, Sapoval N, Treangen TJ, Moraes-Vieira PM, Vanderburg C, Wallace DC, Schisler JC, Mason CE, Chatterjee A, Meller R, Beheshti A: Role of miR-2392 in driving SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep 2021, 37, 109839.

- Valle A, Soto Z, Muhamadali H, Hollywood KA, Xu Y, Lloyd JR, Goodacre R, Cantero D, Cabrera G, Bolivar J: Metabolomics for the design of new metabolic engineering strategies for improving aerobic succinic acid production in Escherichia coli. Metabolomics : Official journal of the Metabolomic Society 2022, 18, 56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong W, Hannou SA, Wang Y, Astapova I, Sargsyan A, Monn R, Thiriveedi V, Li D, McCann JR, Rawls JF, Roper J, Zhang GF, Herman MA: The intestine is a major contributor to circulating succinate in mice. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2022, 36, e22546.

- Kalan Sarı I, Keskin O, Seremet Keskin A, Elli Dağ HY, Harmandar O: Is Homocysteine Associated with the Prognosis of Covid-19 Pneumonia. Int J Clin Pract 2023, 2023, 9697871.

- Carpenè G, Negrini D, Henry BM, Montagnana M, Lippi G: Homocysteine in coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a systematic literature review. Diagnosis (Berl) 2022, 9, 306–310. [CrossRef]

- Lee SR, Roh JY, Ryu J, Shin HJ, Hong EJ: Activation of TCA cycle restrains virus-metabolic hijacking and viral replication in mouse hepatitis virus-infected cells. Cell & bioscience 2022, 12, 7.

- Stipanuk MH, Ueki I: Dealing with methionine/homocysteine sulfur: cysteine metabolism to taurine and inorganic sulfur. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34, 17–32. [CrossRef]

- Kimura Y, Koike S, Shibuya N, Lefer D, Ogasawara Y, Kimura H: 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces potential redox regulators cysteine- and glutathione-persulfide (Cys-SSH and GSSH) together with signaling molecules H(2)S(2), H(2)S(3) and H(2)S. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 10459. [CrossRef]

- Sen U, Sathnur PB, Kundu S, Givvimani S, Coley DM, Mishra PK, Qipshidze N, Tyagi N, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC: Increased endogenous H2S generation by CBS, CSE, and 3MST gene therapy improves ex vivo renovascular relaxation in hyperhomocysteinemia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012, 303, C41–C51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal R, Pal VK, K SS, Menon GJ, Singh IR, Malhotra N, C SN, Ganesh K, Rajmani RS, Narain Seshasayee AS, Chandra N, Joshi MB, Singh A: Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) coordinates redox balance, carbon metabolism, and mitochondrial bioenergetics to suppress SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS Pathog 2025, 21, e1013164.

- Han SJ, Noh MR, Jung JM, Ishii I, Yoo J, Kim JI, Park KM: Hydrogen sulfide-producing cystathionine γ-lyase is critical in the progression of kidney fibrosis. Free Radic Biol Med 2017, 112, 423–432. [CrossRef]

- Jung KJ, Jang HS, Kim JI, Han SJ, Park JW, Park KM: Involvement of hydrogen sulfide and homocysteine transsulfuration pathway in the progression of kidney fibrosis after ureteral obstruction. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1832, 1989–1997. [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizi E, Fiorentino F, Carafa V, Altucci L, Mai A, Rotili D: Emerging Roles of SIRT5 in Metabolism, Cancer, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cells 2023, 12.

- Sanchez-Russo L, Billah M, Chancay J, Hindi J, Cravedi P: COVID-19 and the Kidney: A Worrisome Scenario of Acute and Chronic Consequences. J Clin Med 2021, 10.

- Madsen HB, Durhuus JA, Andersen O, Straten PT, Rahbech A, Desler C: Mitochondrial dysfunction in acute and post-acute phases of COVID-19 and risk of non-communicable diseases. NPJ Metab Health Dis 2024, 2, 36. [CrossRef]

- Fong P, Wusirika R, Rueda J, Raphael KL, Rehman S, Stack M, de Mattos A, Gupta R, Michels K, Khoury FG, Kung V, Andeen NK: Increased Rates of Supplement-Associated Oxalate Nephropathy During COVID-19 Pandemic. Kidney Int Rep 2022, 7, 2608–2616. [CrossRef]

- Borczuk AC, Yantiss RK: The pathogenesis of coronavirus-19 disease. J Biomed Sci 2022, 29, 87.

- Karam A, Mjaess G, Younes H, Aoun F: Increase in urolithiasis prevalence due to vitamins C and D supplementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Health (Oxf) 2022, 44, e625–e6. [CrossRef]

- Thévenod F, Herbrechter R, Schlabs C, Pethe A, Lee WK, Wolff NA, Roussa E: Role of the SLC22A17/lipocalin-2 receptor in renal endocytosis of proteins/metalloproteins: a focus on iron- and cadmium-binding proteins. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2023, 325, F564–f77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engström J, Koozi H, Didriksson I, Larsson A, Friberg H, Frigyesi A, Spångfors M: Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin independently predicts dialysis need and mortality in critical COVID-19. Scientific reports 2024, 14, 6695.

- Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Curhan GC, Anderson TE, Dretler SP, Preminger GM, Cave DR: Oxalobacter formigenes may reduce the risk of calcium oxalate kidney stones. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008, 19, 1197–1203. [CrossRef]

- Troxel SA, Sidhu H, Kaul P, Low RK: Intestinal Oxalobacter formigenes colonization in calcium oxalate stone formers and its relation to urinary oxalate. J Endourol 2003, 17, 173–176. [CrossRef]

- Mehta M, Goldfarb DS, Nazzal L: The role of the microbiome in kidney stone formation. Int J Surg 2016, 36, 607–612. [CrossRef]

- Pan Y, Su J, Liu S, Li Y, Xu G: Causal effects of gut microbiota on the risk of urinary tract stones: A bidirectional two-sample mendelian randomization study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25704. [CrossRef]

- Serrano R, Corbella X, Rello J: Management of hypoxemia in SARS-CoV-2 infection: Lessons learned from one year of experience, with a special focus on silent hypoxemia. J Intensive Med 2021, 1, 26–30. [CrossRef]

- George CE, Scheuch G, Seifart U, Inbaraj LR, Chandrasingh S, Nair IK, Hickey AJ, Barer MR, Fletcher E, Field RD, Salzman J, Moelis N, Ausiello D, Edwards DA: COVID-19 symptoms are reduced by targeted hydration of the nose, larynx and trachea. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4599. [CrossRef]

- Mafra D, Kemp JA, Cardozo L, Borges NA, Nerbass FB, Alvarenga L, Kalantar-Zadeh K: COVID-19 and Nutrition: Focus on Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of renal nutrition : the official journal of the Council on Renal Nutrition of the National Kidney Foundation 2023, 33, S118–s27. [CrossRef]

- Vuorio A, Raal F, Kovanen PT: Familial hypercholesterolemia: The nexus of endothelial dysfunction and lipoprotein metabolism in COVID-19. Curr Opin Lipidol 2023, 34, 119–125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camp TM, Smiley LM, Hayden MR, Tyagi SC: Mechanism of matrix accumulation and glomerulosclerosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens 2003, 21, 1719–1727. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover PK, Kim DS, Ryall RL: The effect of seed crystals of hydroxyapatite and brushite on the crystallization of calcium oxalate in undiluted human urine in vitro: implications for urinary stone pathogenesis. Mol Med 2002, 8, 200–209. [CrossRef]

- Zhou S, Jiang S, Guo J, Xu N, Wang Q, Zhang G, Zhao L, Zhou Q, Fu X, Li L, Patzak A, Hultström M, Lai EY: ADAMTS13 protects mice against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing inflammation and improving endothelial function. American journal of physiology Renal physiology 2019, 316, F134–f45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Alzahrani KJ, Cruz-Martins N, Batiha GE: The potential role of neopterin in Covid-19: a new perspective. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2021, 476, 4161–4166. [CrossRef]

- Anderson S, McNicholas D, Murphy C, Cheema I, McLornan L, Davis N, Quinlan M: The impact of COVID-19 on acute urinary stone presentations: a single-centre experience. Ir J Med Sci 2022, 191, 45–49. [CrossRef]

- Üntan İ: How did COVID-19 affect acute urolithiasis? An inner Anatolian experience. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2023, 29, 780–785.

- Turney BW, Demaire C, Klöcker S, Woodward E, Sommerfeld HJ, Traxer O: An analysis of stone management over the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany, France and England. BJU Int 2023, 132, 196–201. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar N, Nantha Kumar D, Joshi H: The Impact of Early COVID-19 Pandemic on the Presentation and Management of Urinary Calculi Across the Globe: A Systematic Review. J Endourol 2022, 36, 1255–1264. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The L: Long COVID: 3 years in. Lancet 2023, 401, 795.

- Makhluf H, Madany H, Kim K: Long COVID: Long-Term Impact of SARS-CoV2. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).