Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. PET/CT Protocol

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics Depending on ESC/ERS Risk Status

3.2. CPET Parameters According to the ESC/ERS 2022 Risk Status

3.3. Correlations Between CPET and Hemodynamics

3.4. Correlations Between CPET and Cardiac MRI Parameters

3.5. Correlations Between CPET Parameters and [18F]-FDG and [13N]-Ammonia RV Myocardial Uptake

3.6. Changes in [18F]-FDG and [13N]-Ammonia Uptake by the RV Myocardium Depending on Risk Categories of the Main CPET Determinants of Prognosis

3.7. Peak Oxygen Consumption Category

3.8. The Percent of Predicted Peak Oxygen Consumption Category

3.9. The Ratio of Minute Ventilation to Carbon Dioxide Production Category

3.10. Summary of Correlations Between CPET Parameters and Changes in [18F]-FDG and [13N]-Ammonia Uptake by the RV Myocardium

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest Statement

References

- J.L. Sanders, M. Koestenberger, S. Rosenkranz, B.A. Maron, Right ventricular dysfunction and long-term risk of death, Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 10 (2020) 1646–1658. [CrossRef]

- T. Tuomainen, P. Tavi, The role of cardiac energy metabolism in cardiac hypertrophy and failure, Exp Cell Res. 360 (2017) 12–18. [CrossRef]

- C. Real, C.N. Pérez-García, C. Galán-Arriola, I. García-Lunar, A. García-Álvarez, Right ventricular dysfunction: pathophysiology, experimental models, evaluation, and treatment, Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 77 (2024) 957–970. [CrossRef]

- V. Agrawal, T. Lahm, G. Hansmann, A.R. Hemnes, Molecular mechanisms of right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension: focus on the coronary vasculature, sex hormones, and glucose/lipid metabolism, Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 10 (2020) 1522–1540. [CrossRef]

- Jorge, J. Sáiz, N. Solanes, A.P. Dantas, J.J. Rodríguez-Arias et al., Metabolic changes contribute to maladaptive right ventricular hypertrophy in pulmonary hypertension beyond pressure overload: an integrative imaging and omics investigation, Basic Res Cardiol. 119 (2024) 419–433. [CrossRef]

- C. Sumer, G. Okumus, E.G. Isik, C. Turkmen, A.K. Bilge, M. Inanc, (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by positron emission tomography in patients with IPAH and CTEPH, Pulm Circ. 14 (2024) e12363. [CrossRef]

- N. Goncharova, D. Ryzhkova, K. Lapshin, A. Ryzhkov, A. Malanova, E. Andreeva, O. Moiseeva, PET/CT Imaging of the Right Heart Perfusion and Glucose Metabolism Depending on a Risk Status in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, Pulm Circ. (2025) e70042. [CrossRef]

- D. Dumitrescu, O. Sitbon, J. Weatherald, L.S. Howard, Exertional dyspnoea in pulmonary arterial hypertension, Eur Respir Rev. 26 (2017) 170039. [CrossRef]

- B. Pezzuto, P. Agostoni, The Current Role of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test in the Diagnosis and Management of Pulmonary Hypertension, J Clin Med. 12 (2023) 5465. [CrossRef]

- I. Singh, R.K.F. Oliveira, P. Heerdt, M.B. Brown, M. Faria-Urbina, A.B. Waxman, D.M. Systrom, Dynamic right ventricular function response to incremental exercise in pulmonary hypertension, Pulm Circ. 10 (2020) 2045894020950187. [CrossRef]

- R. Badagliacca, F. Rischard, S. Papa, S. Kubba, R. Vanderpool, J.X. Yuan et al., Clinical implications of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension phenotypes defined by cluster analysis, J Heart Lung Transplant. 39 (2020) 310–320. [CrossRef]

- S.N. Avdeev, O.L. Barbarash, A.E. Bautin et al., 2020 Clinical practice guidelines for Pulmonary hypertension, including chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, Russ J Cardiol. 26 (2021) 4683. [CrossRef]

- M. Humbert, G. Kovacs, M.M. Hoeper et al., 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension, Eur Heart J. 43 (2022) 3618–3731. [CrossRef]

- D. Langleben, S.E. Orfanos, B.D. Fox, N. Messas, M. Giovinazzo, J.D. Catravas, The Paradox of Pulmonary Vascular Resistance: Restoration of Pulmonary Capillary Recruitment as a Sine Qua Non for True Therapeutic Success in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, J Clin Med. 11 (2022) 4568. [CrossRef]

- A. Vonk Noordegraaf, B.E. Westerhof, N. Westerhof, The Relationship Between the Right Ventricle and its Load in Pulmonary Hypertension, J Am Coll Cardiol. 69 (2017) 236–243. [CrossRef]

- B. Pezzuto, R. Badagliacca, F. Muratori, S. Farina, M. Bussotti, M. Correale et al., Role of cardiopulmonary exercise test in the prediction of hemodynamic impairment in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension, Pulm Circ. 12 (2022) e12044.

- A.E. Sherman, R. Saggar, Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, Heart Fail Clin. 19 (2023) 35–43. [CrossRef]

- N.S. Goncharova, A.V. Ryzhkov, K.B. Lapshin, A.F. Kotova, O.M. Moiseeva, Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in mortality risk stratification of patients with pulmonary hypertension, Russ J Cardiol. 28 (2023) 5540. [CrossRef]

- P.M. Heerd, I. Singh, A. Elassal et al., Pressure-based estimation of right ventricular ejection fraction, ESC Heart Fail. (2022)9(2):1436-1443. /: https. [CrossRef]

- H. Ohira, R. deKemp, E. Pena, R.A. Davies, D.J. Stewart, G. Chandy et al., Shifts in myocardial fatty acid and glucose metabolism in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a potential mechanism for a maladaptive right ventricular response, Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 17 (2016) 1424–1431. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, Y. Zou, C. Song, K. Cao, K. Cai, Y. Wu et al., The role of glycolytic metabolic pathways in cardiovascular disease and potential therapeutic approaches, Basic Res Cardiol. 118 (2023) 48. [CrossRef]

- J. Osorio Trujillo, O. Tura-Ceide, J. Pavia et al., 18-FDG uptake on PET-CT and metabolism in pulmonary arterial hypertension, Pulm Hypertens. (2021) PA588. [CrossRef]

- R. Kazimierczyk, P. Szumowski, S.G. Nekolla et al., The impact of specific pulmonary arterial hypertension therapy on cardiac fluorodeoxyglucose distribution in PET/MRI hybrid imaging-follow-up study, EJNMMI Res. 13 (2023) 20. [CrossRef]

- Y. Song, H. Jia, Q. Ma, L. Zhang, X. Lai, Y. Wang, The causes of pulmonary hypertension and the benefits of aerobic exercise for pulmonary hypertension from an integrated perspective, Front Physiol. 15 (2024) 1461519. [CrossRef]

- E.V.M. Ferreira, J.S. Lucena, R.K.F. Oliveira, The role of the exercise physiology laboratory in disease management: pulmonary arterial hypertension, J Bras Pneumol. 50 (2024) e20240240. [CrossRef]

|

Parameters, n (%); M±SD; Me [IQR 25;75]. |

Entire cohort, n=34 |

Low risk, N=11 |

Intermediate risk, N=17 |

High risk, N=6 |

P value (*, **, ***) |

| Age (years) | 33.9 ± 8.7 | 33.1 ± 7.8 | 34.4 ±10.2 | 34.5±7.2 | 0.9 (0.7; 0.9; 0.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 3 (8.8) | 2 (18.1) | 1 (5.8) | 0 (0) | n/a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 6.5 | 24.2 ± 4.0 | 26.2 ± 7.8 | 26.3 ± 7.3 | 0.7 (0.4; 0.9; 0.4) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 6 (17.6) | 3 (27) | 2 (11.7) | 1 (16.7) | n/a |

| Prevalent, n (%) | 6 (17.6) | 3 (27.2) | 1 (5.8) | 2 (33.3) | n/a |

| FC III-IV, n (%) | 20 (58.8) | 0 | 14 (82) | 6 (100) | 0.0002 |

| 6MWT, m | 394.1 ±121.2 | 469.1 ± 71.6 | 365.7 ± 101.9 | 319.7 ± 178.2 | 0.01 (0.006; 0.4; 0.02) |

| Laboratory parameters | |||||

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 767 [144; 2835] | 114.0 [55.5; 210.0] | 1016.0 [532.9; 2796.0] | 4443.0 [3450.0; 5576.0] | 0.00005 (0.006; 0.006;0.000001) |

| CRP, mg/l | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 1.2 ±0.6 | 2.2 ±1.6 | 4.2 ±3.1 | 0.006 (0.04; 0.06; 0.005) |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73m2 | 97.0 ± 28.3 | 100.7 ± 25.9 | 99.7 ± 25.5 | 82.7 ± 39.4 | 0.4 (0.9; 0.2; 0.2) |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 144.1 ± 17.0 | 136.4 ±19.4 | 148.2 ± 14.4 | 148.7 ± 15.7 | 0.1 (0.07; 0.9; 0.2) |

| Lung function test | |||||

| FVC, % | 93.3 ± 15.1 | 97.8 ± 12.7 | 90.3 ± 18.6 | 92.5 ± 6.0 | 0.4 (0.2; 0.8; 0.3 ) |

| FEV1, % | 88.9 ± 9.9 | 94. 9 ± 7.4 | 86.2 ± 9.4 | 83.8 ± 10.9 | 0.02 (0.007; 0.9; 0.05) |

| DLCO, % | 75.1 ± 17.3 | 81.9 ±15.6 | 67.6 ±16.4 | 78.9 ± 18.1 | 0.08 (0.03; 0.2; 0.7) |

| Right heart catheterization | |||||

| mBP, mm Hg | 86.2 ± 11.7 | 92.6 ± 13.4 | 81.8 ± 9.3 | 85.0 ± 9.3 | 0.047 (0.02; 0.4; 0.2) |

| mPAP, mm Hg | 55.7 ± 19.8 | 40.8 ± 13.9 | 63.1 ± 18.5 | 65.8 ± 17.5 | 0.002 (0.002; 0.7; 0.004) |

| RAP, mm Hg | 7.1 ± 5.4 | 3.8 ± 2.8 | 6.7 ± 4.4 | 14.8 ± 4.6 | 0.00005 (0.058; 0.001; 0.000009) |

| PCWP, mm Hg | 8.4 ± 3.6 | 7.7 ± 4.5 | 8.2 ±3.3 | 10.2 ± 1.7 | 0.3 (0.7; 0.2; 0.2) |

| CI, l/min/m2 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | <0.000001 (0.000001; 0.05; 0.000004) |

| PVR, WU | 11.3 [6.5; 15.5] | 5.5 [3.9; 7.2] | 12.5 [11.0; 16.7] | 22.0 [14.8; 34.7] | 0.0002 (0.001; 0.1; 0.00004) |

| PAC, ml/mm Hg | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ±0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.7 ±0.3 | 0.0004 (0.004; 0.1; 0.0002) |

| Sat O2, % | 95.3 ± 2.8 | 96.3 ± 2.9 | 95.0 ± 2.7 | 94.2 ± 2.6 | 0.3 (0.2; 0.5; 0.1) |

| SvO2, % | 62,4 ± 12,3 | 72.2 ± 5.8 | 59.9 ± 10.4 | 49.2 ± 12.0 | 0.00007 (0.001; 0.05; 0.00004) |

| Cardiopulmonary exercise testing | |||||

| Load, W | 73.6 [50.0; 90.0] | 90.0 [87.0; 102.5] | 60.0 [50.0; 75.0] | 50.0 [50.0; 70.0] | 0.001 (0.001; 0.7; 0.03) |

| VO2 peak, ml/min/kg | 13.4 [11.1; 18] | 18.1 [16.9; 22.8] | 11.7 [10.8; 14.2] | 11.7 [10.8; 13.8] | 0.0003 (0.0002; 0.9; 0.01) |

| VO2 peak Predicted, % | 54.4 ± 19.5 | 67.8 ± 19.2 | 47.3 ± 15.1 | 46.7 ± 18.6 | 0.008 (0.004; 0.9; 0.04) |

| %VO2/kg AT Predicted, ml/kg/min | 50.3 ± 17.8 | 61.8 ± 16.2 | 45.4 ± 13.3 | 39.8 ± 21.7 | 0.02 (0.01; 0.5; 0.04) |

| ΔVO2/ΔWR, ml/min/W | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 10.2 ± 2.1 | 8.5 ± 2.4 | 7.8 ± 2.2 | 0.07 (0.06; 0.5; 0.04) |

| V'O2/HR Predicted, % | 62.7 ± 19.0 | 72.7 ± 20.1 | 58.1 ± 17.9 | 55.3 ± 13.2 | 0.07 (0.05; 0.7; 0.07) |

| HR/Vkg, l/ml/kg | 11.0 ± 2.8 | 9.1 ± 2.2 | 12.0 ± 2.7 | 12.2 ± 2.2 | 0.009 (0.006; 0.9; 0.01) |

| VE max Predicted,% | 60.2 ± 17.5 | 66.3 ± 20.1 | 59.4 ± 16.2 | 50.3 ± 12.1 | 0.1 (0.3; 0.2; 0.09) |

| Desaturation, % | 2 [1; 4] | 1.5 [1.0; 4.0] | 2.0 [1.0; 4.0] | 3.0 [2.0; 5.0] | 0.7 (0.7; 0.6; 0.5) |

| ΔVD/VT, % | 2.8 ± 6.8 | 6.3 ± 7.7 | 1.2 ± 6.3 | 1.2 ± 4.8 | 0.1 (0.07; 0.9; 0.1) |

| BR Predicted, %, l | 171.4 ± 48.4 | 146.4 ± 57.9 | 177.0 ± 39.9 | 201.0 ± 37.5 | 0.2 (0.2; 0.3; 0.1) |

| VE/VCO2 | 48.9 ± 13.1 | 42.6 ± 13.6 | 53.5 ± 12.4 | 49.0 ± 10.2 | 0.09 (0.04; 0.4; 0.3) |

| VE/VCO2 AT | 45.2 ± 12.5 | 37.7 ± 8.4 | 50.9 ± 13.9 | 45.2 ± 8.0 | 0.03 (0.01; 0.4; 0.1) |

| PetCO2 rest | 3.38±0.7 | 3.73±0.74 | 3.22±0.73 | 3.16±0.45 | 0.1 (0.09; 0.8; 0.1) |

| PetCO2 peak | 3.06±0.92 | 3.47±0.92 | 2.8±0.92 | 2.9±0.7 | 0.2 (0.07; 0.6; 0.3) |

| ∆ PetCO2 | 0.32±0.49 | 0.25±0.55 | 0.42±0.41 | 0.17±0.59 | 0.5 (0.4; 0.3; 0.7) |

| PetCO2 AT | 3.29±1.07 | 3.72±1.29 | 2.97±0.9 | 3.29±0.7 | 0.3 (0.1; 0.5; 0.5) |

| Cardiac MRI | |||||

| RA short dimension, mm | 49.6 ± 9.8 | 44.0 ± 4.9 | 52.4 ± 9.4 | 54.3 ± 13.7 | 0.03 (0.01; 0.7; 0.03) |

| RV EDV index, ml/m2 | 86.2 ± 22.6 | 79.7 ± 16.6 | 80.8 ± 18.7 | 112.1 ± 25.7 | 0.004 (0.8; 0.006; 0.005) |

| RV ESV index, ml/m2 | 57.1 ± 18.8 | 43.9 ± 12.3 | 56.4 ±10.5 | 85.2 ± 13.9 | 0.00001 (0.01; 0.00007; 0.000008) |

| RV wall thickness, mm | 6.0 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 6.4 ±1.9 | 7.4 ± 1.6 | 0.02 (0.049; 0.2; 0.003 ) |

| RV EF, % | 36.5 ± 11.3 | 45.0 ±7.5 | 34.9 ± 8.8 | 23.2 ± 8.9 | 0.00005 (0.004; 0.01; 0.00005) |

| LA short dimension, mm | 29.6 ± 5.4 | 33.1 ± 5.0 | 28.0 ± 4.3 | 26.2 ± 4.8 | 0.007 (0.01; 0.4; 0.01) |

| LV EDV index, ml/m2 | 58.9 ± 15.9 | 72.7 ± 9.2 | 55.3 ± 12.4 | 39.8 ± 7.6 | 0.000002 (0.0005; 0.01; 0.000001) |

| LV ESV index, ml/m2 | 23.3 ± 7.5 | 29.4 ± 6.2 | 20.8 ±5.4 | 17.0 ± 5.7 | 0.0002 (0.001; 0.2; 0.0009) |

| LV SV index, ml/m2 | 37.2 ± 14.6 | 48.1 ± 15.6 | 34.2 ± 8.9 | 22.6 ± 4.2 | 0.0003 (0.009; 0.007; 0.001) |

| LV EF, % | 60.4 ± 6.3 | 60.8 ± 4.7 | 61.6 ± 6.4 | 57.0 ± 8.4 | 0.3 (0.7; 0.2; 0.2) |

| RV EDVi/LV EDVi | 1.4 [1.03; 1.87] | 1.0 [0.9; 1.2] | 1.5 [1.2; 1.7] | 2.7 [2.3; 4.1] | 0.000001 (0.01; 0.0003; 0.000009) |

| RV ESVi/LV ESVi | 2.37 [1.59; 3.56] | 1.4 [1.3; 1.6] | 2.7 [2.2; 3.3] | 4.6 [4.4; 7.6] | 0.000001 (0.00004; 0.001; 0.00004) |

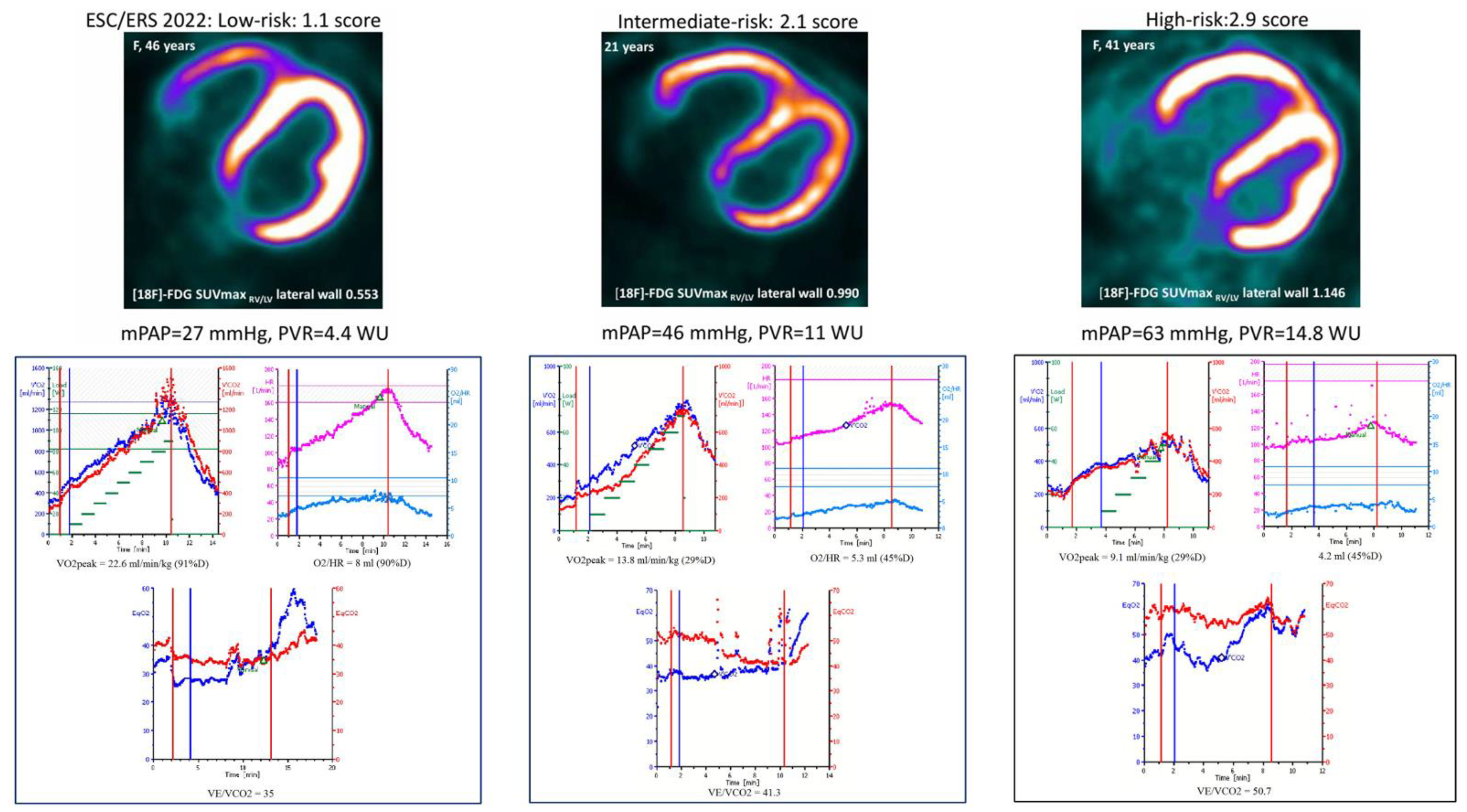

| PET-CT metabolism of the RV/LV | |||||

| [18F]-FDG SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.866±0.365 | 0.581±0.393 | 0.941±0.247 | 1.186±0.293 | 0.002 (0.007; 0.07; 0.01) |

| PET-CT perfusion of the RV/LV | |||||

| [13N]-NH3 SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.817±0.157 | 0.744±0.153 | 0.867±0.142 | 0.796±0.184 | 0.1 (0.04; 0.3; 0.5) |

| The ration of metabolism to perfusion of the RV/LV | |||||

| SUVmax 18F-FDG/SUVmax [13N]-NH3 RV/LV lateral wall | 1.481±0.799 | 0.786±0.321 | 1.646±0.646 | 2.311±0.931 | 0.0002 (0.0006; 0.08; 0.0004) |

| PAH therapy | |||||

| Naïve patients, n (%) | 28 (82.3) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (5.8) | 2 (33.3) | n/a |

| Parameters | Mean PAP | Mean RAP | CI | PAC | ||||||||

| r | t | p | r | t | p | r | t | p | r | t | p | |

| %Load predicted | -0.57 | -3.9 | 0.0004 | -0.003 | -0.02 | 0.9 | 0.44 | 2.8 | 0.009 | 0.48 | 3.2 | 0.003 |

| VO2 peak | -0.45 | -2.9 | 0.007 | -0.17 | -0.9 | 0.3 | 0.48 | 3.1 | 0.004 | 0.35 | 2.1 | 0.04 |

| %VO2 peak predicted | -0.45 | -2.9 | 0.007 | -0.05 | -0.3 | 0.7 | 0.52 | 3.4 | 0.002 | 0.49 | 3.2 | 0.003 |

| VO2/HR | -0.37 | -2.3 | 0.03 | -0.07 | -0.4 | 0.7 | 0.44 | 2.7 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 3.5 | 0.002 |

| % VO2/HR predicted | -0.49 | -3.2 | 0.003 | -0.06 | -0.3 | 0.7 | 0.38 | 2.3 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 3.1 | 0.004 |

| ∆VD/VT | 0.14 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.12 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.10 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| %BR | 0.14 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.16 | 0.7 | 0.5 | -0.39 | -1.8 | 0.08 | -0.43 | -2.1 | 0.05 |

| PetCO2 rest | -0.38 | -2.3 | 0.03 | -0.01 | -0.08 | 0.9 | 0.42 | 2.5 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 2.2 | 0.04 |

| PetCO2 peak | -0.45 | -2.8 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.9 | 0.34 | 2.0 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 2.3 | 0.03 |

| ∆Pet CO2 | 0.23 | 1.3 | 0.2 | -0.04 | -0.2 | 0.8 | -0.007 | -0.04 | 0.9 | -0.15 | -0.8 | 0.4 |

| PetCO2 AT | -0.35 | 1.9 | 0.06 | -0.004 | -0.002 | 0.9 | 0.31 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 0.24 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| ΔVO2/ΔWR | -0.16 | -0.8 | 0.4 | -0.12 | -0.7 | 0.5 | 0.45 | 2.7 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 1.5 | 0.1 |

| HR/Vkg | 0.52 | 3.3 | 0.002 | 0.14 | 0.8 | 0.4 | -0.41 | -2.5 | 0.02 | -0.41 | -2.5 | 0.02 |

| VO2 AT | -0.41 | -2.4 | 0.02 | -0.36 | -2.0 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 3.3 | 0.003 | 0.43 | 2.5 | 0.02 |

| %VO2 AT predicted | -0.45 | -2.6 | 0.01 | -0.13 | -0.7 | 0.5 | 0.56 | 3.5 | 0.002 | 0.53 | 3.2 | 0.004 |

| VE/VCO2 | 0.37 | 2.3 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.6 | 0.5 | -0.37 | -2.3 | 0.03 | -0.28 | -1.7 | 0.1 |

| VE/VCO2 AT | 0.43 | 2.4 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.9 | -0.44 | -2.5 | 0.02 | -0.31 | -1.7 | 0.1 |

| Parameters | RV ESV index | LV SV index | RV EF | RV ESV index/LV ESV index | ||||||||

| r | t | p | r | t | p | r | t | p | r | t | p | |

| %Load predicted | -0.38 | -2.25 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 2.6 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.08 | -0.58 | -3.9 | 0.0005 |

| VO2 peak | -0.29 | -1.67 | 0.1 | 0.54 | 3.5 | 0.001 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.1 | -0.66 | -4.8 | 0.00004 |

| %VO2 peak predicted | -0.37 | -2.19 | 0.036 | 0.49 | 3.1 | 0.004 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.1 | -0.60 | -4.1 | 0.0003 |

| VO2/HR | -0.26 | -1.46 | 0.1 | 0.43 | 2.6 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.9 | 0.3 | -0.42 | -2.5 | 0.02 |

| % VO2/HR predicted | -0.27 | -1.5 | 0.1 | 0.46 | 2.8 | 0.008 | 0.29 | 1.7 | 0.1 | -0.46 | -2.8 | 0.008 |

| ∆VD/VT | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 0.7 | -0.02 | -0.1 | 0.9 |

| %BR | 0.2 | 1.0 | 0.3 | -0.02 | -0.1 | 0.9 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| PetCO2 rest | -0.39 | -2.3 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.2 | -0.53 | -3.3 | 0.002 |

| PetCO2 peak | -0.35 | -2.02 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 2.5 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.2 | -0.52 | -3.3 | 0.002 |

| ∆Pet CO2 | 0.09 | 0.5 | 0.6 | -0.26 | -1.4 | 0.1 | -0.09 | -0.5 | 0.6 | 0.22 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| PetCO2 AT | -0.36 | -1.8 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.18 | 0.9 | 0.4 | -0.43 | -2.4 | 0.02 |

| ΔVO2/ΔWR | -0.21 | -1.1 | 0.3 | 0.44 | 2.6 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | -0.44 | -2.6 | 0.01 |

| HR/Vkg | 0.22 | 1.2 | 0.2 | -0.55 | -3.5 | 0.002 | -0.27 | -1.5 | 0.1 | 0.54 | 3.4 | 0.002 |

| VO2 AT | -0.44 | -2.5 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 3.4 | 0.002 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.2 | -0.69 | -4.8 | 0.00005 |

| %VO2 AT predicted | -0.47 | -2.6 | 0.01 | 0.49 | 2.8 | 0.01 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.2 | -0.63 | -3.9 | 0.0005 |

| VE/VCO2 | 0.30 | 1.7 | 0.09 | -0.42 | -2.5 | 0.016 | -0.19 | -1.1 | 0.3 | 0.51 | 3.3 | 0.002 |

| VE/VCO2 AT | 0.47 | 2.6 | 0.01 | -0.39 | -2.1 | 0.048 | -0.33 | -1.7 | 0.09 | 0.57 | 3.4 | 0.002 |

| Parameters | [18F]-FDGSUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | [13N]-NH3 SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | [18F]-FDGSUVmax/[13N]-NH3 SUVmaxRV/LVlateral wall | ||||||

| r | t | p | r | t | p | r | t | p | |

| %Load predicted | -0.54 | -3.5 | 0.002 | -0.58 | -4.1 | 0.0003 | -0.45 | -2.7 | 0.009 |

| VO2 peak | -0.59 | -4.1 | 0.0003 | -0.46 | -2.9 | 0.006 | -0.54 | -3.5 | 0.01 |

| %VO2 peak predicted | -0.46 | -2.9 | 0.007 | -0.51 | -3.3 | 0.002 | -0.46 | -2.8 | 0.008 |

| VO2/HR | -0.22 | 1.2 | 0.2 | -0.39 | -2.4 | 0.02 | -0.35 | -2.04 | 0.05 |

| % VO2/HR predicted | -0.29 | -1.7 | 0.09 | -0.49 | -3.1 | 0.003 | -0.25 | -1.5 | 0.1 |

| ∆VD/VT | 0.16 | 0.89 | 0.4 | 0.37 | 2.2 | 0.03 | -0.28 | -1.6 | 0.1 |

| %BR | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.08 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.06 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| PetCO2 rest | -0.46 | -2.8 | 0.009 | -0.60 | -4.2 | 0.0002 | -0.26 | -1.4 | 0.2 |

| PetCO2 peak | -0.38 | -2.2 | 0.03 | -0.44 | -2.7 | 0.009 | -0.26 | -1.5 | 0.2 |

| ∆Pet CO2 | 0.08 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| PetCO2 AT | -0.44 | -2.4 | 0.02 | -0.59 | -3.7 | 0.0009 | -0.25 | -1.3 | 0.2 |

| ΔVO2/ΔWR | -0.28 | -0.6 | 0.1 | -0.27 | -1.5 | 0.1 | -0.35 | -1.9 | 0.057 |

| HR/Vkg | 0.45 | 2.7 | 0.01 | 0.53 | 3.4 | 0.002 | 0.42 | 2.5 | 0.02 |

| VO2 AT | -0.56 | -3.4 | 0.002 | -0.46 | -2.7 | 0.01 | -0.47 | -2.7 | 0.01 |

| %VO2 AT predicted | -0.52 | -3.1 | 0.005 | -0.54 | -3.3 | 0.003 | -0.44 | -2.4 | 0.02 |

| VE/VCO2 | 0.37 | 2.2 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 2.2 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 |

| VE/VCO2 AT | 0.44 | 2.5 | 0.02 | 0.62 | 4.02 | 0.0004 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 0.1 |

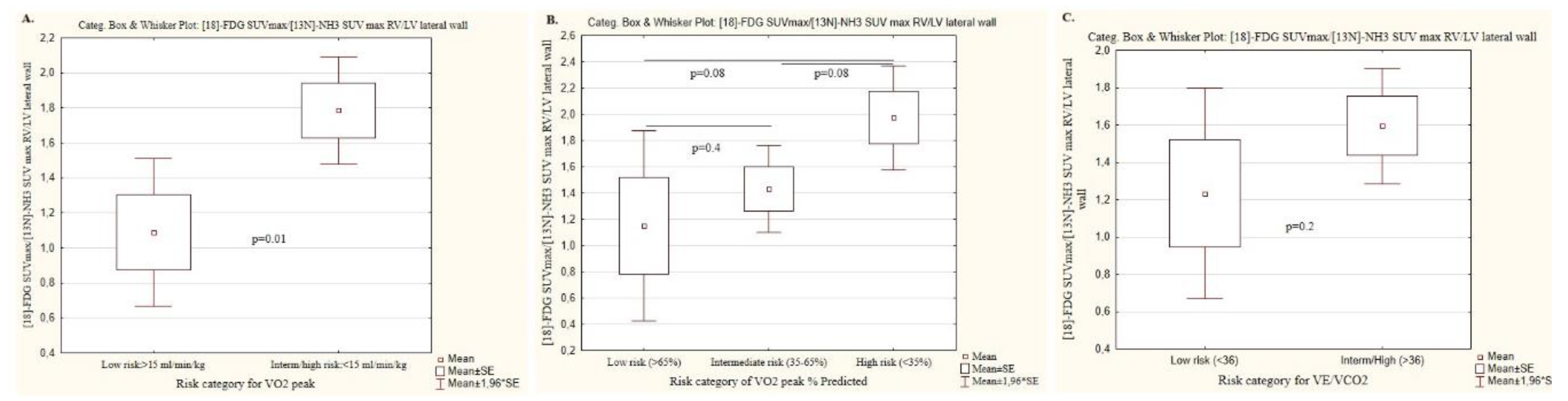

| Peak oxygen consumption, ml/min/kg | ||||

| Parameters, n (%); m±SD | Low risk (n=14) | Intermediate/high risk (n=20) | P value | |

| Risk category | >15 | <15 | ||

| [18F]-FDG SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.59 ±0.28 | 1.08 ±0.26 | 0.00002 | |

| [13N]-NH3 SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.72 ± 0.10 | 0.89 ± 0.15 | 0.0005 | |

| SUVmax 18F-FDG/SUVmax [13N]-NH3 RV/LV lateral wall | 1.08 ±0.8 | 1.78±0.6 | 0.01 | |

| Peak oxygen consumption, %, Predicted | ||||

| Risk category | Low risk (n=8) | Intermediate (n=17) | High risk (n=9) |

P value, all groups (*;**;***) |

| >65 | 35-65 | <35 | ||

| [18F]-FDG SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.6 ±0.3 | 0.9 ±0.3 | 1.2 ±0.3 | 0.01 (0.1; 0.04; 0.005) |

| [13N]-NH3 SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.7 ± 0.07 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ±0.2 | 0.003 (0.04; 0.04; 0.001) |

| SUVmax 18F-FDG/SUVmax [13N]-NH3 RV/LV lateral wall | 1.2 ±1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 0.1 (0.4; 0.08; 0.08) |

| VE/VCO2, the ratio of minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production | ||||

| Risk category | Low risk (n=10) | Intermediate/high risk (n=24) | P value | |

| <36 | >36 | |||

| [18F]-FDG SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.007 | |

| [13N]-NH3 SUVmax RV/LV lateral wall | 0.7 ± 0.09 | 0.8 ± 0.16 | 0.03 | |

| SUVmax 18F-FDG/SUVmax [13N]-NH3 RV/LV lateral wall | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 0.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).