Submitted:

25 July 2025

Posted:

28 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Morphofunction Aspects of Microglia

1.2. Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroinflammation in MDD

1.3. Conventional Therapeutic Approaches and Their Limitations

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Brain-Targeted Drug Delivery Systems

3.2. Controlled Release Systems

3.3. Drug Delivery Strategies for Microglial Modulation

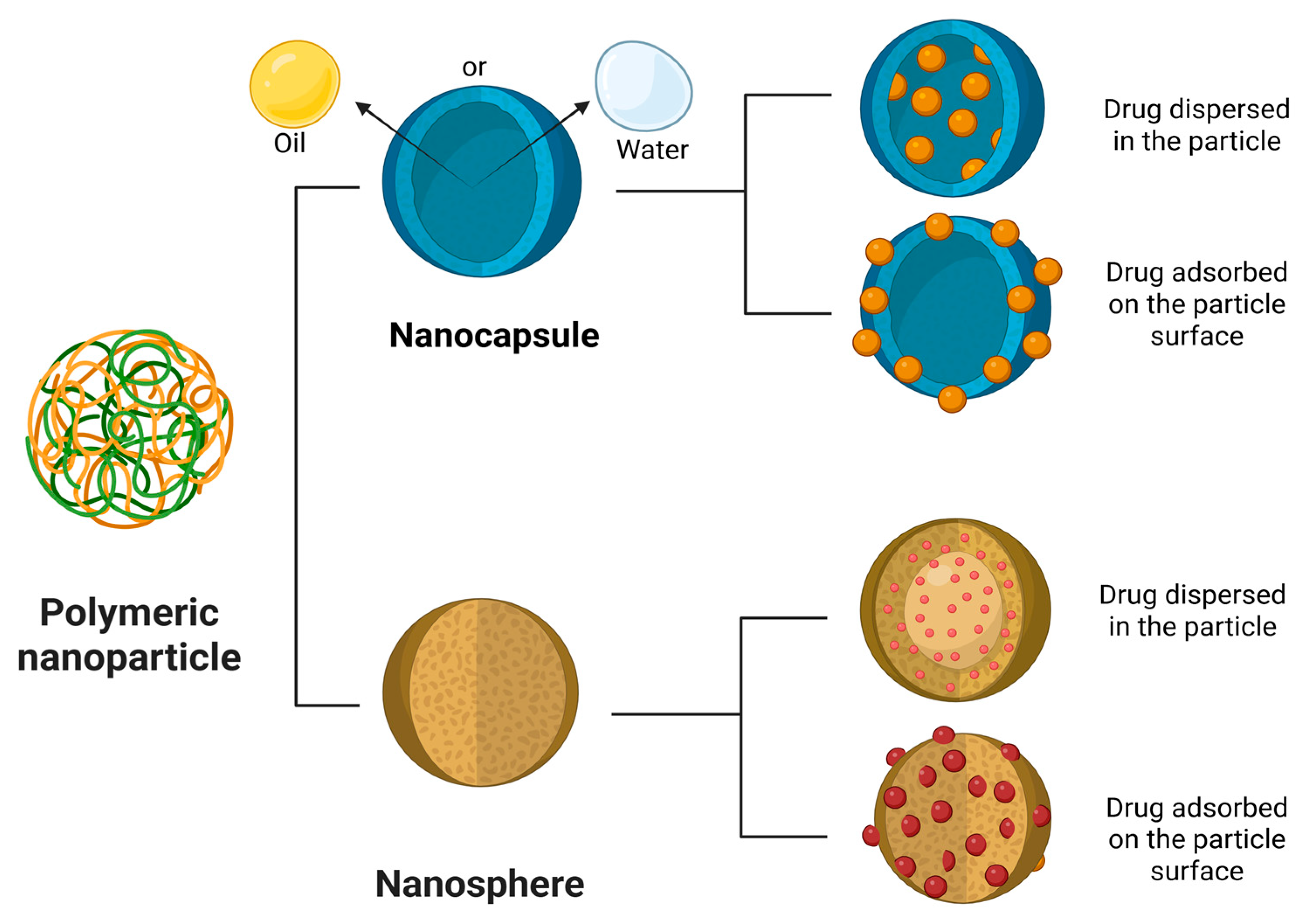

3.4. Polymeric Nanoparticles

3.5. Solid Lipid Nanoparticle

3.6. Magnetic Nanoparticle

3.7. Dendrimers

3.8. Liposome

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maes, M.; Galecki, P.; Chang, Y.S.; Berk, M. A Review on the Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress (O&NS) Pathways in Major Depression and Their Possible Contribution to the (Neuro)Degenerative Processes in That Illness. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2011, 35, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.N.; Bot, M.; Scheffer, P.G.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W.J.H. Is Depression Associated with Increased Oxidative Stress? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 51, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, A.K.; Maltese, P.E.; Dautaj, A.; Paolacci, S.; Kurti, D.; Picotti, P.M.; Bertelli, M. Neurobiological Basis of Chiropractic Manipulative Treatment of the Spine in the Care of Major Depression. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91, e2020006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E.; Toups, M.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Bidirectional Relationship of Depression and Inflammation: Double Trouble. Neuron 2020, 107, 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthen, R.J.; Beurel, E. Inflammatory and Neurodegenerative Pathophysiology Implicated in Postpartum Depression. Neurobiology of Disease 2022, 165, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, R.; Rimmerman, N.; Reshef, R. Depression as a Microglial Disease. Trends in Neurosciences 2015, 38, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troubat, R.; Barone, P.; Leman, S.; Desmidt, T.; Cressant, A.; Atanasova, B.; Brizard, B.; El Hage, W.; Surget, A.; Belzung, C.; et al. Neuroinflammation and Depression: A Review. Eur J of Neuroscience 2021, 53, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The Role of Inflammation in Depression: From Evolutionary Imperative to Modern Treatment Target. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Haroon, E.; Felger, J.C. Therapeutic Implications of Brain–Immune Interactions: Treatment in Translation. Neuropsychopharmacol 2017, 42, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Jones, G.T.; Hughes, D.M.; Moots, R.J.; Goodson, N.J. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms at TNF Inhibitor Initiation Are Associated with Impaired Treatment Response in Axial Spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 5734–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodburn, S.C.; Bollinger, J.L.; Wohleb, E.S. The Semantics of Microglia Activation: Neuroinflammation, Homeostasis, and Stress. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorkina, Y.; Abramova, O.; Ushakova, V.; Morozova, A.; Zubkov, E.; Valikhov, M.; Melnikov, P.; Majouga, A.; Chekhonin, V. Nano Carrier Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Advantages and Limitations. Molecules 2020, 25, 5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J.; Maincent, P.; Xia, X.; Wu, W. Updated Progress of Nanocarrier-Based Intranasal Drug Delivery Systems for Treatment of Brain Diseases. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst 2018, 35, 433–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitorino, C.; Silva, S.; Bicker, J.; Falcão, A.; Fortuna, A. Antidepressants and Nose-to-Brain Delivery: Drivers, Restraints, Opportunities and Challenges. Drug Discovery Today 2019, 24, 1911–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Dong, J.; Lu, Y. The Blood–Brain Barriers: Novel Nanocarriers for Central Nervous System Diseases. J Nanobiotechnol 2025, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guan, M.; Zhang, N.-N.; Wang, Y.; Liang, T.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Sun, T.; Liu, S. Harnessing Nanomedicine for Modulating Microglial States in the Central Nervous System Disorders: Challenges and Opportunities. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 177, 117011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, S.E.; Kingery, N.D.; Ohsumi, T.K.; Borowsky, M.L.; Wang, L.; Means, T.K.; El Khoury, J. The Microglial Sensome Revealed by Direct RNA Sequencing. Nat Neurosci 2013, 16, 1896–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, M.L.; McAllister, A.K. Alterations in Immune Cells and Mediators in the Brain: It’s Not Always Neuroinflammation! Brain Pathology 2014, 24, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoubas, C.C.; Molofsky, A.V. Microglia as Integrators of Brain-Associated Molecular Patterns. Trends in Immunology 2024, 45, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ren, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, G.; Yang, J. Microglia in Depression: An Overview of Microglia in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Depression. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.-Q.; Ma, X.-T.; Hu, Z.-W.; Yang, S.; Chen, M.; Bosco, D.B.; Wu, L.-J.; Tian, D.-S. Dual Functions of Microglia in Ischemic Stroke. Neurosci. Bull. 2019, 35, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodburn, S.C.; Bollinger, J.L.; Wohleb, E.S. The Semantics of Microglia Activation: Neuroinflammation, Homeostasis, and Stress. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlati, Y.; Herrmann, N.; Swardfager, W.; Liu, H.; Sham, L.; Reim, E.K.; Lanctôt, K.L. A Meta-Analysis of Cytokines in Major Depression. Biological Psychiatry 2010, 67, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major Depressive Disorder: Hypothesis, Mechanism, Prevention and Treatment. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélanger, M.; Magistretti, P.J. The Role of Astroglia in Neuroprotection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2009, 11, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélanger, M.; Magistretti, P.J. The Role of Astroglia in Neuroprotection. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2009, 11, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early, J.O.; Menon, D.; Wyse, C.A.; Cervantes-Silva, M.P.; Zaslona, Z.; Carroll, R.G.; Palsson-McDermott, E.M.; Angiari, S.; Ryan, D.G.; Corcoran, S.E.; et al. Circadian Clock Protein BMAL1 Regulates IL-1β in Macrophages via NRF2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2018, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.J.; Huang, X.-F.; Newell, K.A. The Kynurenine Pathway in Major Depression: What We Know and Where to Next. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2021, 127, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Landucci Bonifacio, K.; Morelli, N.R.; Vargas, H.O.; Barbosa, D.S.; Carvalho, A.F.; Nunes, S.O.V. Major Differences in Neurooxidative and Neuronitrosative Stress Pathways Between Major Depressive Disorder and Types I and II Bipolar Disorder. Mol Neurobiol 2019, 56, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, J.L.; Surachman, A.; Saunders, E.F.H.; Alexander, L.M.; Almeida, D.M. Greater Daily Psychosocial Stress Exposure Is Associated With Increased Norepinephrine-Induced Vasoconstriction in Young Adults. JAHA 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ni, J.; Zhai, L.; Gao, C.; Xie, L.; Zhao, L.; Yin, X. Inhibition of Activated Astrocyte Ameliorates Lipopolysaccharide- Induced Depressive-like Behaviors. Journal of Affective Disorders 2019, 242, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennis, M.; Gerritsen, L.; Van Dalen, M.; Williams, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Bockting, C. Prospective Biomarkers of Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, Y.; Niu, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Meng, W. BDNF Enhances Electrophysiological Activity and Excitatory Synaptic Transmission of RA Projection Neurons in Adult Male Zebra Finches. Brain Research 2023, 1801, 148208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major Depressive Disorder: Hypothesis, Mechanism, Prevention and Treatment. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcocer-Gómez, E.; Cordero, M.D. NLRP3 Inflammasome: A New Target in Major Depressive Disorder. CNS Neurosci Ther 2014, 20, 294–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. The Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-W.; Suzuki, K.; Kavalali, E.T.; Monteggia, L.M. Ketamine: Mechanisms and Relevance to Treatment of Depression. Annu. Rev. Med. 2024, 75, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A.; Salanti, G.; Chaimani, A.; Atkinson, L.Z.; Ogawa, Y.; Leucht, S.; Ruhe, H.G.; Turner, E.H.; Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. Comparative Efficacy and Acceptability of 21 Antidepressant Drugs for the Acute Treatment of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemke, C.; Bergemann, N.; Clement, H.; Conca, A.; Deckert, J.; Domschke, K.; Eckermann, G.; Egberts, K.; Gerlach, M.; Greiner, C.; et al. Consensus Guidelines for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Neuropsychopharmacology: Update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry 2018, 51, 9–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.D.D.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Gregório, M.J.; Branco, J.D.C.; Gouveia, M.J.; Canhão, H.; Dias, S.S. Anxiety and Depression in the Portuguese Older Adults: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Front. Med. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, F.H.; Samhani, I.; Mustafa, M.Z.; Shafin, N. Pathophysiology of Depression: Stingless Bee Honey Promising as an Antidepressant. Molecules 2022, 27, 5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, T.; Guski, L.S.; Freund, N.; Gøtzsche, P.C. Suicidality and Aggression during Antidepressant Treatment: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses Based on Clinical Study Reports. BMJ 2016, i65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, S.; Parr, B.-A.; Hussey, S.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S.; Arora, D.; Grant, G.D. The Neurodegenerative Hypothesis of Depression and the Influence of Antidepressant Medications. European Journal of Pharmacology 2024, 983, 176967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richelson, E. Multi-Modality: A New Approach for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 16, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severe, J.; Greden, J.F.; Reddy, P. Consequences of Recurrence of Major Depressive Disorder: Is Stopping Effective Antidepressant Medications Ever Safe? FOC 2020, 18, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Miguel, C.; Ciharova, M.; Ebert, D.; Harrer, M.; Karyotaki, E. Transdiagnostic Treatment of Depression and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 6535–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, V.L.; Cleare, A.J.; Young, A.H.; Stone, J.M. Acceptability, Tolerability, and Estimates of Putative Treatment Effects of Probiotics as Adjunctive Treatment in Patients With Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Liang, H.; Ding, L.; Xia, X.; Xiong, L.; Qi, X.-R.; Zheng, J.C. Microglial Glutaminase 1 Deficiency Mitigates Neuroinflammation Associated Depression. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2022, 99, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Liu, L.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMP-Sensing Receptors in Sterile Inflammation and Inflammatory Diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suneson, K.; Lindahl, J.; Chamli Hårsmar, S.; Söderberg, G.; Lindqvist, D. Inflammatory Depression—Mechanisms and Non-Pharmacological Interventions. IJMS 2021, 22, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, A.H.; Barres, B.A.; Stevens, B. The Complement System: An Unexpected Role in Synaptic Pruning During Development and Disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiraly, D.D.; Horn, S.R.; Van Dam, N.T.; Costi, S.; Schwartz, J.; Kim-Schulze, S.; Patel, M.; Hodes, G.E.; Russo, S.J.; Merad, M.; et al. Altered Peripheral Immune Profiles in Treatment-Resistant Depression: Response to Ketamine and Prediction of Treatment Outcome. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1065–e1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, S.A.; Beurel, E.; Loewenstein, D.A.; Lowell, J.A.; Craighead, W.E.; Dunlop, B.W.; Mayberg, H.S.; Dhabhar, F.; Dietrich, W.D.; Keane, R.W.; et al. Defective Inflammatory Pathways in Never-Treated Depressed Patients Are Associated with Poor Treatment Response. Neuron 2018, 99, 914–924.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Wan, X.; Zhuang, P.; Jia, W.; Ao, Y.; Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, L.; Huang, Y.; Yao, J.; et al. High Fried Food Consumption Impacts Anxiety and Depression Due to Lipid Metabolism Disturbance and Neuroinflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westfall, S.; Caracci, F.; Estill, M.; Frolinger, T.; Shen, L.; Pasinetti, G.M. Chronic Stress-Induced Depression and Anxiety Priming Modulated by Gut-Brain-Axis Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannestad, J.; DellaGioia, N.; Bloch, M. The Effect of Antidepressant Medication Treatment on Serum Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines: A Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychopharmacol 2011, 36, 2452–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner-Schmidt, J.L.; Vanover, K.E.; Chen, E.Y.; Marshall, J.J.; Greengard, P. Antidepressant Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Are Attenuated by Antiinflammatory Drugs in Mice and Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 9262–9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piletz, J.E.; Halaris, A.; Iqbal, O.; Hoppensteadt, D.; Fareed, J.; Zhu, H.; Sinacore, J.; DeVane, C.L. Pro-Inflammatory Biomakers in Depression: Treatment with Venlafaxine. The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2009, 10, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, M.; Hao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, C. Neuroinflammation Mechanisms of Neuromodulation Therapies for Anxiety and Depression. Transl Psychiatry 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazula, R.; Husain, M.I.; Mohebbi, M.; Walker, A.J.; Chaudhry, I.B.; Khoso, A.B.; Ashton, M.M.; Agustini, B.; Husain, N.; Deakin, J.; et al. Minocycline as Adjunctive Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder: Pooled Data from Two Randomized Controlled Trials. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2021, 55, 784–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tan, C.; Ge, X.; Qin, Z.; Xiong, H. Recent Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Controlled Release Systems for Neuromodulation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 5769–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadry, H.; Noorani, B.; Cucullo, L. A Blood–Brain Barrier Overview on Structure, Function, Impairment, and Biomarkers of Integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lochhead, J.J.; Yang, J.; Ronaldson, P.T.; Davis, T.P. Structure, Function, and Regulation of the Blood-Brain Barrier Tight Junction in Central Nervous System Disorders. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebner, S.; Czupalla, C.J.; Wolburg, H. Current Concepts of Blood-Brain Barrier Development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2011, 55, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Fan, X. Microvascular Pericytes in Brain-Associated Vascular Disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 121, 109633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Ayyadurai, S.; Zlokovic, B.V. Pericytes of the Neurovascular Unit: Key Functions and Signaling Pathways. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsbrook, D.L.; Di Napoli, M.; Bhatia, K.; Biller, J.; Andalib, S.; Hinduja, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Rodriguez, M.; Sabbagh, S.Y.; Selim, M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Acute Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2023, 23, 407–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varatharaj, A.; Galea, I. The Blood-Brain Barrier in Systemic Inflammation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2017, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, P.; Bloise, E.; Imperio, G.E.; Chitayat, D.; Matthews, S.G. Functional Expression of Multidrug-Resistance (MDR) Transporters in Developing Human Fetal Brain Endothelial Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscher, W.; Potschka, H. Blood-Brain Barrier Active Efflux Transporters: ATP-Binding Cassette Gene Family. 2005, 2.

- Taskar, K.S.; Yang, X.; Neuhoff, S.; Patel, M.; Yoshida, K.; Paine, M.F.; Brouwer, K.L.R.; Chu, X.; Sugiyama, Y.; Cook, J.; et al. Clinical Relevance of Hepatic and Renal P-gp/BCRP Inhibition of Drugs: An International Transporter Consortium Perspective. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 2022, 112, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosavljevic, M.; Svob Strac, D.; Jancic, J.; Samardzic, J. The Role of Pharmacogenetics in Personalizing the Antidepressant and Anxiolytic Therapy. Genes 2023, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, F.E.; Dinan, T.G.; Griffin, B.T.; Cryan, J.F. Interactions between Antidepressants and P-glycoprotein at the Blood–Brain Barrier: Clinical Significance of in Vitro and in Vivo Findings. British J Pharmacology 2012, 165, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuban, W.; Daniel, W.A. Cytochrome P450 Expression and Regulation in the Brain. Drug Metabolism Reviews 2021, 53, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.; Hoda, N. A Comprehensive Review of Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors as Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agents: A Review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 206, 112787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, R.J.; Tsukamoto, H.; Pardridge, W.M. Drug Delivery of Antisense Molecules to the Brain for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease and Cerebral AIDS. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 1998, 87, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, W.A.; Rhea, E.M.; Reed, M.J.; Erickson, M.A. The Penetration of Therapeutics across the Blood-Brain Barrier: Classic Case Studies and Clinical Implications. Cell Reports Medicine 2024, 5, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dichiara, M.; Amata, B.; Turnaturi, R.; Marrazzo, A.; Amata, E. Tuning Properties for Blood–Brain Barrier Permeation: A Statistics-Based Analysis. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddart, R.; Hicks, J.K.; Ramsey, L.B.; Strawn, J.R.; Smith, D.M.; Bobonis Babilonia, M.; Altman, R.B.; Klein, T.E. PharmGKB Summary: Sertraline Pathway, Pharmacokinetics. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 2020, 30, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koepsell, H. Glucose Transporters in Brain in Health and Disease. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol 2020, 472, 1299–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Z.-X.; Wu, Y.-H.; Hu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.-D.; Li, F.; Wei, A.-J.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Mediated by the EZH2-Claudin-5 Axis Drives Stress-Induced TNF-α Infiltration and Depression-like Behaviors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2024, 115, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixensberger, S.; Kuzior, H.; Fiebich, B.L.; Süß, P.; Runge, K.; Berger, B.; Nickel, K.; Denzel, D.; Schiele, M.A.; Michel, M.; et al. Upregulation of sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 Levels in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haqqani, A.S.; Bélanger, K.; Stanimirovic, D.B. Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis for Brain Delivery of Therapeutics: Receptor Classes and Criteria. Front. Drug Deliv. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Khan, A.I.; Cai, X.; Song, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Du, D.; Dutta, P.; Lin, Y. Overcoming Blood–Brain Barrier Transport: Advances in Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Strategies. Materials Today 2020, 37, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, N.; Waqar, M.A.; Khan, A.M.; Asif, Z.; Alvi, A.S.; Virk, A.A.; Amir, S. A Comprehensive Insight of Innovations and Recent Advancements in Nanocarriers for Nose-to-Brain Drug Targeting. Designed Monomers and Polymers 2025, 28, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, R.; Song, G.; Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Gao, N.; Wang, H. Drug Delivery Across the Blood–Brain Barrier: A New Strategy for the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepu, S.; Ramakrishna, S. Controlled Drug Delivery Systems: Current Status and Future Directions. Molecules 2021, 26, 5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Morales, C.; Caspani, S.; Desco, M.; Tavares De Sousa, C.; Gómez-Gaviro, M.V. Controlled Drug Release Systems for Cerebrovascular Diseases. Advanced Therapeutics 2025, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; De, R.; Lee, K.T. Emerging Strategies to Fabricate Polymeric Nanocarriers for Enhanced Drug Delivery across Blood-Brain Barrier: An Overview. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 320, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Tang, Z.; Niu, M.; Kuang, Z.; Xue, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Jeong, S.; Ma, Y.; et al. Allosteric Targeted Drug Delivery for Enhanced Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration via Mimicking Transmembrane Domain Interactions. Nat Commun 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xu, J.; Yao, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhan, C. Peptide-Decorated Nanocarriers Penetrating the Blood-Brain Barrier for Imaging and Therapy of Brain Diseases. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2022, 187, 114362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.I.; Lopes, C.M.; Amaral, M.H.; Costa, P.C. Surface-Modified Lipid Nanocarriers for Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB): A Current Overview of Active Targeting in Brain Diseases. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2023, 221, 112999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafati, N.; Zarepour, A.; Bigham, A.; Khosravi, A.; Naderi-Manesh, H.; Iravani, S.; Zarrabi, A. Nanosystems for Targeted Drug Delivery: Innovations and Challenges in Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier for Neurodegenerative Disease and Cancer Therapy. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 666, 124800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Dumitru, A.V.; Eva, L.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Ciurea, A.V. Nanoparticle Strategies for Treating CNS Disorders: A Comprehensive Review of Drug Delivery and Theranostic Applications. IJMS 2024, 25, 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zeng, H.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, C.; Hu, P. Recent Applications of PLGA in Drug Delivery Systems. Polymers 2024, 16, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabold, B.; Adams, F.; Brameyer, S.; Jung, K.; Ried, C.L.; Merdan, T.; Merkel, O.M. Transferrin-Modified Chitosan Nanoparticles for Targeted Nose-to-Brain Delivery of Proteins. Drug Deliv. and Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 822–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, M.; Tomaro-Duchesneau, C.; Saha, S.; Prakash, S. Intranasal, siRNA Delivery to the Brain by TAT/MGF Tagged PEGylated Chitosan Nanoparticles. Journal of Pharmaceutics 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graván, P.; Aguilera-Garrido, A.; Marchal, J.A.; Navarro-Marchal, S.A.; Galisteo-González, F. Lipid-Core Nanoparticles: Classification, Preparation Methods, Routes of Administration and Recent Advances in Cancer Treatment. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 2023, 314, 102871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleraky, N.; M. Omar, M.; A. Mahmoud, H.; A. Abou-Taleb, H. Nanostructured Lipid Carriers to Mediate Brain Delivery of Temazepam: Design and In Vivo Study. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Sun, Z.; Ren, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, G.; Yang, J. Microglia in Depression: An Overview of Microglia in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Depression. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florendo, M.; Figacz, A.; Srinageshwar, B.; Sharma, A.; Swanson, D.; Dunbar, G.L.; Rossignol, J. Use of Polyamidoamine Dendrimers in Brain Diseases. Molecules 2018, 23, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitsch, H.; Hersh, A.M.; Alomari, S.; Tyler, B.M. Dendrimer Technology in Glioma: Functional Design and Potential Applications. Cancers 2023, 15, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, M.; Afshari, S.; Samizadegan, T.; Shirmard, L.R.; Barin, S. Pegylated Chitosan Nanoparticles of Fluoxetine Enhance Cognitive Performance and Hippocampal Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels in a Rat Model of Local Demyelination. Experimental Gerontology 2024, 195, 112533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, A.R.; Van Der Putten, L.; Queiroz, J.F.; Pinheiro, M.; Reis, S. Transferrin-Functionalized Lipid Nanoparticles for Curcumin Brain Delivery. Journal of Biotechnology 2021, 331, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldeeb, G.M.; Yousef, M.I.; Helmy, Y.M.; Aboudeya, H.M.; Mahmoud, S.A.; Kamel, M.A. The Protective Effects of Chitosan and Curcumin Nanoparticles against the Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles-Induced Neurotoxicity in Rats. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, H.; Xie, G.; et al. Facile Engineered Macrophages-Derived Exosomes-Functionalized PLGA Nanocarrier for Targeted Delivery of Dual Drug Formulation against Neuroinflammation by Modulation of Microglial Polarization in a Post-Stroke Depression Rat Model. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 179, 117263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, M.; Khan, M.; Khan, R.A.; Maghrabi, I.A.; Ahmed, B. Polysorbate-80-Coated, Polymeric Curcumin Nanoparticles for in Vivo Anti-Depressant Activity across BBB and Envisaged Biomolecular Mechanism of Action through a Proposed Pharmacophore Model. Journal of Microencapsulation 2016, 33, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Z.; He, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Chen, X.; Deng, Z.; et al. Bioinspired Polydopamine Nanoparticles as Efficient Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Enhancers against UV-Induced Skin Damage. J Nanobiotechnol 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Yang, X.; Huang, Q.; Lei, T.; Luo, H.; Wu, D.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Dou, Y.; Ma, X.; et al. Microglial-Biomimetic Memantine-Loaded Polydopamine Nanomedicines for Alleviating Depression. Advanced Materials 2025, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, E.M.; Savall, A.S.P.; Da Luz Abreu, E.; Carvalho, F.; Teixeira, F.E.G.; Haas, S.E.; Bazanella Sampaio, T.; Pinton, S. Curcumin-Loaded Nanocapsules Reverses the Depressant-Like Behavior and Oxidative Stress Induced by β-Amyloid in Mice. Neuroscience 2019, 423, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhuang, X.; Huang, R.; Zhu, R.; Wang, S. Targeting the Endocannabinoid/CB1 Receptor System For Treating Major Depression Through Antidepressant Activities of Curcumin and Dexanabinol-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 42, 2281–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Jing, G.; Zhu, R.; Wang, S. Antidepressant Effects of Curcumin and HU-211 Coencapsulated Solid Lipid Nanoparticles against Corticosterone-Induced Cellular and Animal Models of Major Depression. IJN 2016, Volume 11, 4975–4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadrawy, Y.A.; Hosny, E.N.; Magdy, M.; Mohammed, H.S. Antidepressant Effects of Curcumin-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles in a Rat Model of Depression. European Journal of Pharmacology 2021, 908, 174384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.M.; Aboalasaad, F.A.; Mohamed, A.S.; Elhusseiny, F.A.; Khadrawy, Y.A.; Elmekawy, A. Evaluation of the Therapeutic Effect of Curcumin-Conjugated Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Reserpine-Induced Depression in Wistar Rats. Biol Trace Elem Res 2024, 202, 2630–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubab, S.; Naeem, K.; Rana, I.; Khan, N.; Afridi, M.; Ullah, I.; Shah, F.A.; Sarwar, S.; Din, F.U.; Choi, H.-I.; et al. Enhanced Neuroprotective and Antidepressant Activity of Curcumin-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Depression and Anxiety Rat Model. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2021, 603, 120670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeb, A.; Rana, I.; Choi, H.-I.; Lee, C.-H.; Baek, S.-W.; Lim, C.-W.; Khan, N.; Arif, S.T.; Sahar, N.U.; Alvi, A.M.; et al. Potential and Applications of Nanocarriers for Efficient Delivery of Biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, M.; Shah, F.A.; Sahar, N.; Malik, I.; Din, F.U.; Khan, S.A.; Aman, W.; Choi, H.-I.; Lim, C.-W.; Noh, H.-Y.; et al. Formulation Optimization, in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of Agomelatine-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Augmented Antidepressant Effects. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2022, 216, 112537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-F.; Duan, L.; Wang, Y.-X.; Wang, C.-L.; Tian, M.-L.; Qi, X.-J.; Qiu, F. Design, Characterization of Resveratrol-Thermosensitive Hydrogel System (Res-THS) and Evaluation of Its Anti-Depressant Effect via Intranasal Administration. Materials & Design 2022, 216, 110597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.-J.; Liu, X.-Y.; Tang, L.-M.-Y.; Li, P.-F.; Qiu, F.; Yang, A.-H. Anti-Depressant Effect of Curcumin-Loaded Guanidine-Chitosan Thermo-Sensitive Hydrogel by Nasal Delivery. Pharmaceutical Development and Technology 2020, 25, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Hu, P.; Cai, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Hu, W.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Chen, D.; et al. Identification of a Microglial Activation-Dependent Antidepressant Effect of Amphotericin B Liposome. Neuropharmacology 2019, 151, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Wei, Y.; Pi, C.; Cheng, J.; Su, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wen, J.; Wei, Y.; Ma, J.; et al. Preparation and Evaluation of Curcumin Derivatives Nanoemulsion Based on Turmeric Extract and Its Antidepressant Effect. IJN 2023, Volume 18, 7965–7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchiwa, P.-O.; Nudmamud-Thanoi, S.; Phoungpetchara, I.; Tiyaboonchai, W. Comparison of Curcumin-Based Nano-Formulations for Antidepressant Effects in an Animal Model. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 88, 104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Nance, E.; Alnasser, Y.; Kannan, R.; Kannan, S. Microglial Migration and Interactions with Dendrimer Nanoparticles Are Altered in the Presence of Neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, S.; Ali, S.; Esa, M.; Khan, A.; Yan, H. Recent Advancements and Unexplored Biomedical Applications of Green Synthesized Ag and Au Nanoparticles: A Review. IJN 2024, Volume 19, 3187–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.M.D.S.; Santana, L.M.D.; Nadvorny, D.; Abreu, B.O.D.; Rebouças, J.D.S.; Formiga, F.R.; Soares, M.F.D.L.R.; Soares-Sobrinho, J.L. Nanoparticle Design for Hydrophilic Drugs: Isoniazid Biopolymeric Nanostructure. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 87, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.M.D.S.; Oliveira, A.C.D.J.; Dourado, D.; Santana, L.M.D.; Medeiros, T.S.; Nadvorny, D.; Silva, M.L.R.; Rolim-Neto, P.J.; Moreira, D.R.M.; Formiga, F.R.; et al. Rifampicin-Loaded Phthalated Cashew Gum Nano-Embedded Microparticles Intended for Pulmonary Administration. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 303, 140693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Leite, J.M.; Patriota, Y.B.G.; De La Roca, M.F.; Soares-Sobrinho, J.L. New Perspectives in Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment ofTuberculosis. CMC 2022, 29, 1936–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnamte, M.; Pulikkal, A.K. Biocompatible Polymeric Nanoparticles as Carriers for Anticancer Phytochemicals. European Polymer Journal 2024, 202, 112637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; He, R.; Wang, P.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liang, J. Exosomes from LPS-Stimulated Macrophages Induce Neuroprotection and Functional Improvement after Ischemic Stroke by Modulating Microglial Polarization. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagpal, K.; Singh, S.K.; Mishra, D. Evaluation of Safety and Efficacy of Brain Targeted Chitosan Nanoparticles of Minocycline. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2013, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.-R.; Cheng, L.-M.; He, X.-L.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z.-J.; Huang, R.-Q. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Loading with Curcumin and Dexanabinol to Treat Major Depressive Disorder. Neural Regen Res 2021, 16, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.J.; Mahajan, S.S.; Majumdar, A.S. Nose to Brain Delivery of Flurbiprofen from a Solid Lipid Nanoparticles-Based Thermosensitive in-Situ Gel. Neuroscience Applied 2024, 3, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarezadeh, A.; Alizadeh, P.; Yourdkhani, A.; Motesadi Zarandi, F. Synthesis of Copper Ferrite-Decorated Bioglass Nanoparticles: Investigation of Magnetic Properties, Biocompatibility, and Drug Release Behaviour. Applied Surface Science 2025, 708, 163713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolo, C.A.; Ismail, E.A.; Amuhaya, E.K.; Fasiku, V.; Nwabuife, J.C.; Mohamed, M.; Gafar, M.A.; Kalhapure, R.; Govender, T. Revolutionizing Drug Delivery: The Promise of Surface Functionalized Dendrimers in Overcoming Conventional Limitations. European Polymer Journal 2025, 235, 114079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yuan, M.; Qin, W.; Bai, H.; Liu, H.; Che, J. A Novel Strategy for Liposomal Drug Separation in Plasma by TiO2 Microspheres and Application in Pharmacokinetics. IJN 2023, Volume 18, 1321–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drug delivery systems | Compound used | Physico-chemical properties | In vitro release | In vitro activity | In vivo activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric nanoparticle | Celastrol and minocycline | Size: 132 nm PZ: 35,5 mV |

- | - | Decrease in iNOS and CD86; increase in Arg-1 and CD206. Enhanced antidepressant activities and functional capacity. Alleviated brain inflammation in rats. | Lv et al (2024) [106] |

| Polymeric nanoparticle | Curcumin | Size: 194,3±14,8 nm PZ: 19,5±2,6 mV PDI: 0,359±0,014 EE: 63,9±7,2% |

83,78 ± 7,43 a 95,56 ± 4,67% em 144h | - | CUR-NP: decreased immobility (FST/TST), effective at 5 mg/kg, increased bioavailability (1.6x), increased SOD/catalase activity | Yusuf (2016) [107] |

| Polymeric nanoparticle | Dopamine hydrochloride | Size: 244 nm PDI: 0,119 PZ:-48 mV |

- | Polydopamine nanoparticles (NPs) eliminated >90% of DPPH radicals at 20 μg/mL (no significant difference compared to ascorbic acid) and significantly reduced intracellular ROS levels in LPS-treated PC12 cells | - | Zhang (2023) [108] |

| Polymeric nanoparticle | Memantine | Size: 163.5 ± 1.5 nm; PZ: -54.3 ± 2.2 mV |

Safety: No significant cytotoxicity (over 80% viability) in human neuroblastoma and mouse brain cells at high concentrations. Anti-inflammatory Action: Significantly reduced intracellular ROS and polarized microglia from M1 (pro-inflammatory) to M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotype, decreasing CD86, TNF-α, IL-2, and increasing CD206, TGF-β, IL-10. |

Biodistribution and Efficacy: Showed higher accumulation in the brain and hippocampus (1.3x > PDA), confirming improved targeting. Outperformed Memantine monotherapy with lower, less frequent doses and greater efficacy. Safety: Demonstrated minimal observed toxicity. Inflammatory Modulation: Reduced hippocampal ROS and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2); increased anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10). Neuroplasticity and Neuroprotection: Stimulated neurogenesis, exhibited neuroprotective effects, and restored synaptic plasticity (leading to decreased neuroinflammation and improved neuronal function). |

Jiang et al., 2025 [109] | |

| Polymeric nanoparticle | Celastrol and minocycline | 132 nm; PZ: -35.5 mV |

- | Microglial Modulation: CMC-EXPL significantly suppressed M1 (pro-inflammatory) microglial polarization (reducing CD80 and iNOS) and promoted M2 (anti-inflammatory) polarization (increasing CD206 and Arg1) in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells. Therapeutic Potential: Showed superior anti-inflammatory therapeutic potential compared to other nanoformulations tested. |

Antidepressant Behavior: The nanoformulation controlled weight loss and reversed induced depressive behaviors in POSD rats. Microglial Modulation: Significantly reduced M1 markers (iNOS and CD86) and increased M2 markers (Arg-1 and CD206), confirming the M1 to M2 microglial polarization in the brains of POSD rats, contributing to its antidepressant efficacy. |

Lv et al., 2024 [106] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticle | Curcumin | 291 a 312 nm PZ: 22-36 mV |

- | - | NLC C reversed the effects of Aβ₂₅₋₃₅ (↑663.3% immobility in TST/FST), normalized SOD/CAT levels, and did not alter OFT performance | Fidelis et al., (2019) [110] |

| Solid lipid nanoparticle | Curcumin and dexanabinol | PZ: -22,6 ± 0,9 mV; EE: 19,12% ± 1,43% e 0,81% ± 0,04% |

Increase in DA/5-HT; reduction in cellular apoptosis | Increase in DA/5-HT levels and mRNA expression of CB1, p-MEK1, and p-ERK1/2 in the hippocampus and striatum | He et al 2017 [111] | |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles | HU-211 and curcumin | PZ: -21,7 ± 0,4 mV | 77% in 7 days | Increased expression of CB1, p-MEK1, and p-ERK1/2; cellular uptake: 99% | Increased dopamine levels | He et al 2016 [112] |

| Magnetic nanoparticles | Curcumin | 15 ± 3 nm PZ: -25 mV |

- | - | Increase in Na⁺, K⁺-ATPase activity and elevated levels of monoamine neurotransmitters. Prevention of excitotoxicity mediated by NMDA receptor overactivation. | Khadrawy et al., 2021 [113] |

| Magnetic nanoparticles | Curcumin | 342 ± 22,3 PDI: 1 PZ: − 25,6 ± 4,61 mV |

- | - | Decrease in malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, increase in reduced glutathione (GSH) and catalase (CAT) levels, and elevated concentrations of serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) | Fahmy et al. (2023) [114] |

| Nanostructured lipid carriers | Curcumin | 147,8 ± 10,4 nm; PDI: 0,27 ± 0,02; PZ: − 32,8 ± 1,4 mV; EE: 91,0 ± 4,6% | ~54% and ~73% at 12 h and 24 h, respectively | - | Suppression of p-NF-κB, TNF-α, and COX-2 expression | Rubab et al. (2021) [115] |

| Nanostructured lipid carriers | Curcumin | 147.8 ± 10.4 nm; PZ: -32.8 ± 1.4 mV |

- | - | Indirect Microglial Neuroprotection: CUR-NLCs markedly attenuated LPS-induced neurodegenerative damage and restored tissue architecture and cellular integrity. Anti-inflammatory Action: The nanoparticles suppressed the expression of pro-inflammatory markers (p-NF-κB, TNF-α, and COX-2) induced by LPS in the brain, reducing neuroinflammation. |

Zeb et al., 2020 [116] |

| Nanostructured lipid carriers | Agomelatine | 99.8 ± 2.6 nm; PZ: 23.2 ± 1.2 mV |

- | - | Enhanced Anti-inflammatory Effect: AGM-NLCs effectively suppressed LPS-induced neuroinflammation, reducing both the expression and concentrations of TNF-α and COX-2 in the brain. Indirect Microglial Action: Encapsulated agomelatine exerts an indirect effect on microglia by reducing inflammation, contributing to neuronal defense and integrity maintenance. |

Gul et al., 2022 [117] |

| Hydrogel | Resveratrol |

Porous structure characterized by dense and irregularly sized voids |

Res ~35% and Res-THS ~59% in 10 hours | - | Immobility time in the FST (~180 s → ~95 s); Corticosterone (CORT) levels (~160 → ~100 ng/mL); 5-HT, DA, and NA levels in the brain. |

Zhou et al. (2022) [118] |

| Hydrogel | Curcumin | Viscosity at 15–25 °C. | Thermosensitive GCS hydrogel containing 12.75% curcumin and curcumin/HP-β-CD complex achieved 55.54% release in 10 hours. | - | Significant reduction in immobility time in the forced swim test (FST) and tail suspension test (TST); reversal of ptosis and hypothermia (except for hydrogel at 58.4 μg/kg); increased levels of 5-HT, NE, and DA in the brain; effect comparable to fluoxetine | Qi et al., 2020 [119] |

| Liposome | Amphotericin B | - | - | - | Antidepressant Efficacy: In mice with Chronic Unpredictable Stress (CUS)-induced depression, AmB liposomal (at 1 and 3 mg/kg doses) markedly reversed depressive behaviors in a dose-dependent manner. This effect was not observed with isolated Amphotericin B. Microglial Mechanism of Action: Microglial activation is essential for the antidepressant effect of AmB liposomal. Pre-treatment with minocycline (a microglial inhibitor) inhibited the antidepressant effect and reduced IL-1β and IL-6. PLX3397 (a microglial depletor) abolished both the antidepressant effect and the pro-inflammatory and depressive effects. |

Gao et al., 2019 [120] |

| Nanoemulsion | Curcumin | 116,0 ± 0,305 nm PDI: 0,121 ± 0,007 PZ: −11,6 ± 1,23 mV EE: 98,45 ± 0,31% |

TUR-NE showed 36.51 ± 3.24% release in HCl and 44.90 ± 2.47% release in PBS over 48 hours | TUR exhibited the highest antioxidant activity (ABTS•⁺), followed by CU and Vitamin C, with IC₅₀ values of 17.9, 29.1, and 57 µg/mL, respectively | TUR-NE increased sucrose preference (77.5% vs. 54.0% in CUMS), decreased immobility time in the forced swim test (FST) (P < 0.01), reduced latency to feed in the novelty-suppressed feeding test (NSFT), and elevated plasma serotonin levels (21.7 vs. 16.3 ng/mL) as well as brain serotonin levels (46.9 vs. 44.0 ng/mL); MAO activity showed no significant changes. | Sheng et al. (2023) [121] |

| Self-emulsifying system | Curcumin | 150 nm | 100% release within 5 minutes | 7.4 ± 0.2 mL (sucrose) | 103.4 ± 5.8 s (FST) | 247 ± 3.1 g (weight) | Partial neuroprotective and hepatoprotective effects | Suchiwa Pan et al. (2023) [122] | |

| Dendrimers | Polyamidoamine | 4 nm | - | Increased Microglial Uptake: Uptake of PAMAM dendrimers by microglial cells was faster and more extensive in cerebral slices from rabbits with Cerebral Palsy (CP) compared to healthy controls. It was 1.6 times higher after 4 hours of treatment, with 80% of cells containing dendrimers in CP slices. | Selective Accumulation: PAMAM dendrimers selectively accumulated in activated microglia within the brains of newborn rabbits. Therapeutic Outcome: When conjugated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), this accumulation led to a dramatic improvement in motor function and attenuated neuroinflammation. |

Zhang et al., 2016 [123] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).