Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Drought Indices and Indicators

2.1. Classical Drought Indices and Indicators

2.1.1 Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI)

2.1.2. Standardized Precipitation Indices (SPIs)

2.1.3. Thornthwaite Moisture Index (TMI)

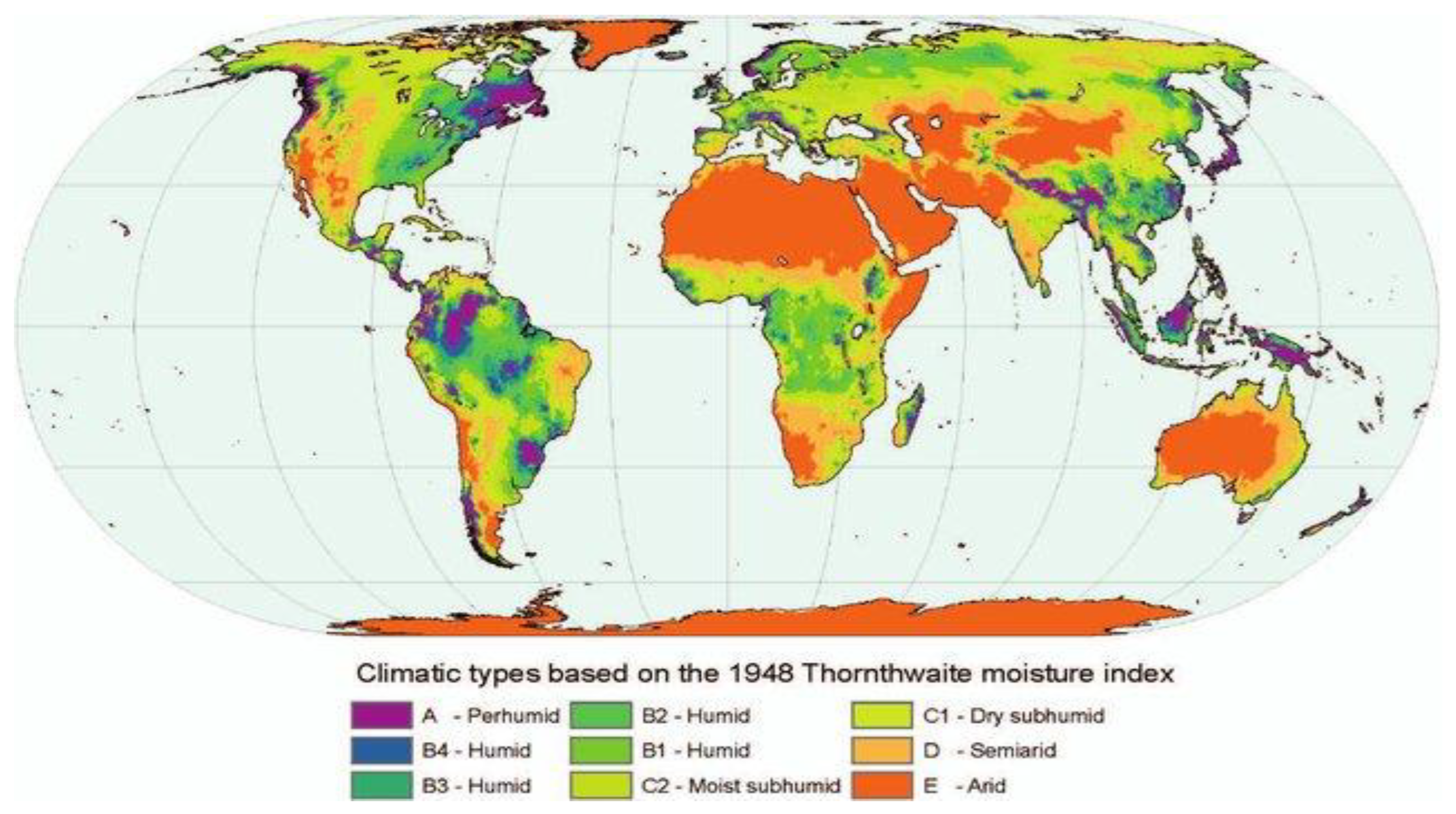

2.1.4. Aridity Index (AI)

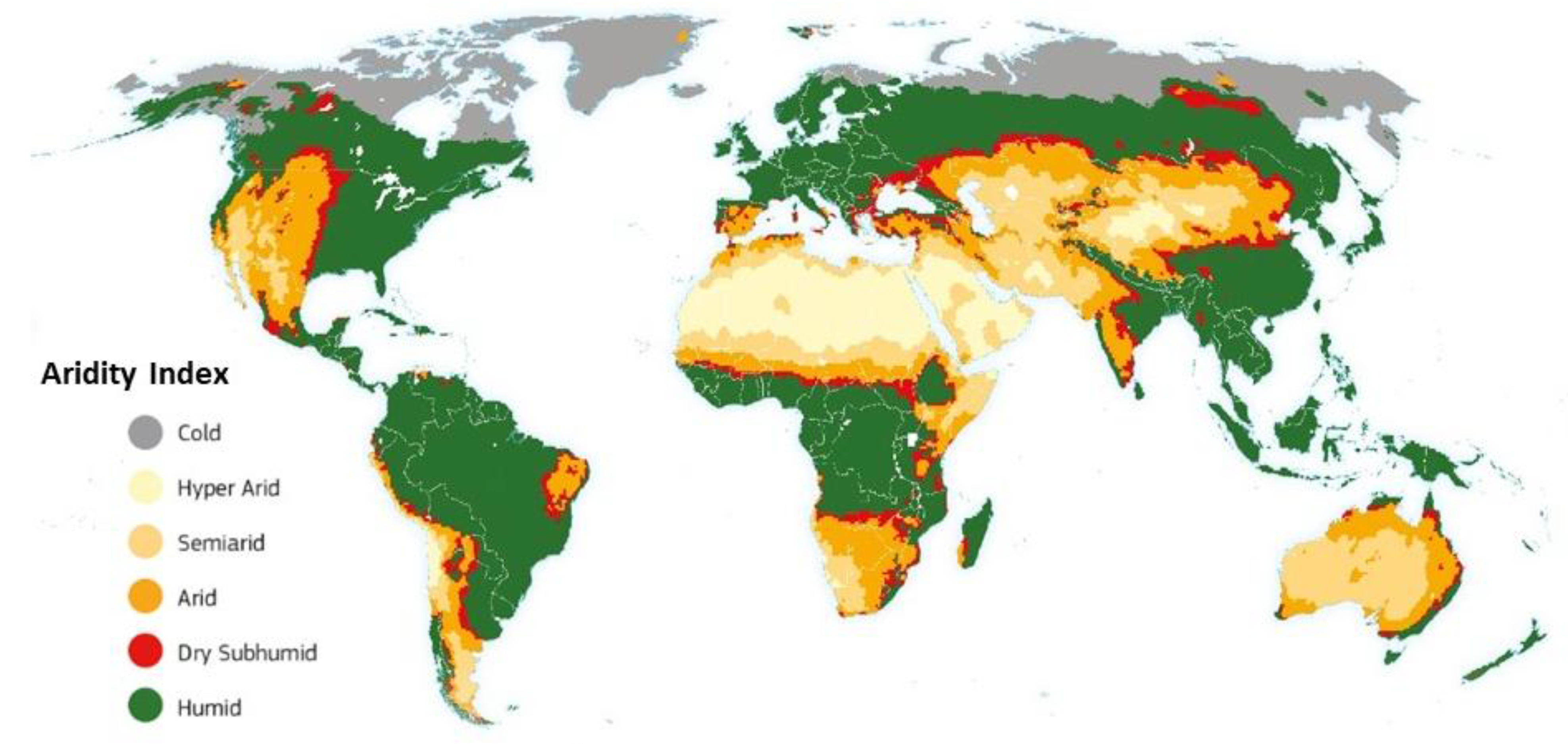

2.1.5. Rainfall Anomaly Index (RAI)

2.1.6. Crop Moisture Index (CMI)

2.2. Holistic Indices and Indicators

2.2.1. U.S. Drought Monitor (USDM)

2.2.2. Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI)

2.2.3. Agricultural Drought Risk Index (ADRI)

2.2.4. Hydrological Drought Index (HDI)

2.2.5. Socioeconomic Drought Index (SEDI)

2.2.6. Composite Drought Index (CDI)

3. Drought Indices and Indicators Comparisons

3.1. Comparison Criteria

| Index/indicator | P | T | PE | AWC | CD | SF | GW | SM | Multiple | Spatial scale | Temporal scale | Data requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | ||||||||||||

| PDSI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Global | Monthly | High | ||||||

| SPI/SPEI | ✓ | ✓ | Global | Daily, weekly, monthly | High | |||||||

| TMI | ✓ | Global | Monthly | Low | ||||||||

| AI | ✓ | ✓ | Global | Monthly | Low | |||||||

| RAI | ✓ | Regional | Monthly | Medium | ||||||||

| CMI | ✓ | ✓ | Regional | Weekly | Medium | |||||||

| Holistic | ||||||||||||

| USDM | ✓ | Country | Weekly | Medium | ||||||||

| DSCI | ✓ | Global | Monthly, annually | High | ||||||||

| ADRI | ✓ | Regional | Monthly, annually | High | ||||||||

| HDI | ✓ | Regional | Annually | High | ||||||||

| SEDI | ✓ | Global | Annually | High | ||||||||

| CDI | ✓ | Global | Annually | High |

3.2. Drought Event Hotspots

4. Drought Indices and Indicators Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Indices and Indicators

- Sensitivity to data inputs: The accuracy of indices is highly dependent on the quality and availability of data inputs (i.e., meteorological data, socioecological data, agricultural data, etc.). The quality and quantity of input data are important for accurate drought assessment. For example, precipitation data is used to derive the SPI-based drought index. By comparing the spatiotemporal differences and drought area capture capabilities over 23 sub-datasets spanning 30 years, the study of Liu et al. (2016) concluded that SPDI is less sensitive to data selection than sc-PDSI. Moreover, the SPDI series derived from different datasets are highly correlated and consistent in drought area characterization. SPDI is most sensitive to changes in the scale parameter, followed by location and shape parameters. It was looked into how sensitive each of the seven precipitation-based drought indices was to varying record lengths at monthly, seasonal, and annual time scales. The findings showed that better time steadiness was observed in Z-score Index (ZSI) and Effective Drought Index (EDI) compared to other indices such as the Deciles Index (DI), Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), Percent of Normal Precipitation Index (PNPI), China Z Index (CZI), and the Modified China Z Index (MCZI) (Mahmoudi et al., 2019). Due to sensitivity to a relatively wider range of factors, holistic indices/indicators have the advantage over classical indices/indicators.

- Lack of consistency: Different drought indices may yield different results for the same area or time period. There is no universal drought indicator and previous studies identified significant discrepancies between the state drought indices (Feng et al., 2017). The most exact and accurate techniques to track agricultural conditions are drought indices estimated from ground observations of soil moisture, precipitation, and temperature. The accuracy of drought indices also depends on accurate estimates of soil parameters based on in-situ measurements; calculation methods and missing data (Pan et al., 2023). Coupled climatic and socioeconomic aspects are interlinked to drought conditions in one region and distinct in another location. Many of these features are meticulously interrelated with each other and any decision-making ability regarding their inclusion has certain consequences in terms of accuracy and effective outcomes. The problem of inconsistency is prominent in the case of both holistic and classical indicators that consider multiple parameters.

- Artificial Intelligence-based drought assessment: Droughts can be modeled, observed, and predicted using high-resolution spatiotemporal resolution data. Drought-causing factors and mechanisms operate on a wide range of spatial scales, from the movement of soil water to global atmospheric circulation. There is huge lack of multiscale drought monitoring and early warning systems (Mardian, 2022). Further, the Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA) developed new high-resolution datasets providing more detailed local information that can be used to evaluate drought severity for specific periods and regions and determine global, regional, and local trends, thereby supporting the development of site-specific adaptation measures (Gebrechorkos et al., 2023). There is an emerging need to develop novel datasets that can serve fundamental data support for future studies. The integration of machine learning (ML) models – usually superior to traditional techniques – has a promising answer since they are good at addressing non-stationarities and non-linearities in drought assessment. For instance, DroughtCast ML was utilized to forecast a very extreme drought event up to 12 weeks before its onsets. It offers promising findings for decision-makers, land managers, and public institutions in preparing for and mitigating the impacts of drought.

- Complex interpretation: Some drought indices are based on complex mathematical algorithms, making them difficult for non-experts (i.e., smallholder farmers) to interpret and need more attention. This can limit their utility for decision-making. The work of reported that Fluixá-Sanmartín et al. (2018) due to the general complexity of droughts, the comparison of the index-identified events with droughts at different levels of the complete system, including soil humidity or river discharges, relies typically on model simulations of the latter, entailing potentially significant uncertainties and decidedly biased outcomes. The short-term anomalies are overlooked – regarding the interactions of soil moisture and evapotranspiration – hiding the influence of long-term anomalies of rainfall, soil moisture, and evapotranspiration that cause recurrent droughts and heatwaves (Gaona et al., 2022). To solve these challenges, there is a need for collaborative efforts (e.g., expert consultation, access documentation, multi-indices understanding, access to historical data and stakeholder engagement, etc.) and requiring interdisciplinary expertise from various fields (e.g., agriculturalists, climatologists, socio-economists, and ecologists, etc.).

- Data Infrastructure and Maintenance: Remote sensing infrastructural development and their maintenance outlays can be costly, thus hindering accessibility to accurate and precise data in developing countries.

4.2. Necessity for Multidisciplinary Indices and Indicators

4.3. Data, Methodological and Technological Challenges

5. Conclusions

- i)

- There is no single drought indicator, whether classical or holistic, for all drought types in all specific regions and climates, because all available drought indicators have their limitation during development and application. Therefore, drought indicator selection requires a thorough investigation related to the type of drought and the respective drought indicator based on the availability of data, ease of communication, result implication, strength and limitations of the indices, and the objective of the investigation. Drought indices/indicators assimilate thousands of bits of data on meteorological, agricultural, socioeconomic, and ecological data into a comprehensive big picture. Due to a lack of large-scale application, experts must make their own judgments regarding holistic indicators’ pros and cons.

- ii)

- Holistic indices require huge amounts of data. The lack of sufficient infrastructure for collecting and monitoring data in many regions, particularly in developing countries, produces gaps and inaccuracies in data. A regional or national drought assessment may not be able to provide the necessary detail based on data collected at the local level. There is a need for affordable geospatial infrastructures and technologies. The development of new composite methods should be used as building blocks and integrating remote sensing to support multinational and disciplinary approaches with local participation to attain sustainable drought monitoring.

- iii)

- Various indices/indicators produce contradictory findings regarding drought hotspots. For instance, the PDSI also tends to underestimate runoff conditions whereas CMI is limited to use only in the growing season; it cannot determine the long-term period of drought. The meteorological drought indices may not solely be appropriate and adequate to assess agricultural drought due to the lag between agricultural and meteorological drought. The main reason for these controversial results can be the choice of drought indices/indicators and the accuracy of satellite products used to derive drought indices/indicators. Ultimately, the evaluation criteria should align with the objectives of the drought monitoring and management efforts, and the chosen index should meet the specific needs of the stakeholders and decision-makers.

- iv)

- Future research studies should focus on novel geospatial intelligence (Geo-AI) based drought indices that could facilitate in assessing, categorizing, and disclosing deep drought conditions; utilization of earth observations that include satellite, climate, oceanic, and biophysical data for efficient drought analysis and improved seasonal prediction; combine or integrate drought indices based on improved modelling techniques; apply the data mining and GIS applications to build Drought Early Warning Systems (DEWSs); and explore the impact of drought on sustainable food systems.

Conflicts of Interest

Acknowledgments

Data availability statement

References

- Akyuz, F. Drought severity and coverage index. united states drought monitor. https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/About/AbouttheData/DSCI.aspx 2017.

- Ali, M.; Ghaith, M.; Wagdy, A.; Helmi, A.M. Development of a New Multivariate Composite Drought Index for the Blue Nile River Basin. Water 2022, 14, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alley, W.M. The Palmer Drought Severity Index: Limitations and Assumptions. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 1984, 23, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubrecht, C.; Özceylan, D.; Steinnocher, K.; Freire, S. Multi-level geospatial modeling of human exposure patterns and vulnerability indicators. Natural Hazards 2013, 68, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccari, B. A comparative analysis of disaster risk, vulnerability and resilience composite indicators. PLoS Currents 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.I.; Götte, J.; Schlemper, C.; Van Loon, A.F. Hydrological Drought Generation Processes and Severity Are Changing in the Alps. Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50, e2022GL101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammalleri, C.; Arias-Muñoz, C.; Barbosa, P.; de Jager, A.; Magni, D.; Masante, D.; Mazzeschi, M.; McCormick, N.; Naumann, G.; Spinoni, J.; et al. A revision of the Combined Drought Indicator (CDI) used in the European Drought Observatory (EDO). Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 21, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrão, H.; Naumann, G.; Barbosa, P. Mapping global patterns of drought risk: An empirical framework based on sub-national estimates of hazard, exposure and vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 2016, 39, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crausbay, S.D.; Betancourt, J.; Bradford, J.; Cartwright, J.; Dennison, W.C.; Dunham, J.; Enquist, C.A.; Frazier, A.G.; Hall, K.R.; Littell, J.S. Unfamiliar territory: Emerging themes for ecological drought research and management. One Earth 2020, 3, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crausbay, S.D.; Ramirez, A.R.; Carter, S.L.; Cross, M.S.; Hall, K.R.; Bathke, D.J.; Betancourt, J.L.; Colt, S.; Cravens, A.E.; Dalton, M.S.; et al. Defining Ecological Drought for the Twenty-First Century. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2017, 98, 2543–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, N.D. Drought resilience, adaptation and management policy (DRAMP) framework. Bonn: UNCCD 2018, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, A. Drought under global warming: a review. WIREs Climate Change 2011, 2, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nature Climate Change 2013, 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S.; Massah Bavani, A.R.; Roozbahani, A.; Gohari, A.; Berndtsson, R. Towards an integrated system modeling of water scarcity with projected changes in climate and socioeconomic conditions. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 33, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikici, M. Drought analysis with different indices for the Asi Basin (Turkey). Sci Rep 2020, 10, 20739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohue, R.J.; McVicar, T.R.; Roderick, M.L. Assessing the ability of potential evaporation formulations to capture the dynamics in evaporative demand within a changing climate. Journal of Hydrology 2010, 386, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erian, W.; Pulwarty, R.; Vogt, J.; AbuZeid, K.; Bert, F.; Bruntrup, M.; El-Askary, H.; de Estrada, M.; Gaupp, F.; Grundy, M. GAR special report on drought 2021; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR): 2021.

- Faiz, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, N.; Baig, F.; Naz, F.; Niaz, Y. Drought indices: aggregation is necessary or is it only the researcher’s choice? Water Supply 2021, 21, 3987–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Aryal, S.K.; Ha, T.T.V.; Baig, F.; Naz, F. A composite drought index developed for detecting large-scale drought characteristics. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 605, 127308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddema, J.J. A Revised Thornthwaite-Type Global Climate Classification. Physical Geography 2005, 26, 442–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Trnka, M.; Hayes, M.; Zhang, Y. Why do different drought indices show distinct future drought risk outcomes in the US Great Plains? Journal of Climate 2017, 30, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluixá-Sanmartín, J.; Pan, D.; Fischer, L.; Orlowsky, B.; García-Hernández, J.; Jordan, F.; Haemmig, C.; Zhang, F.; Xu, J. Searching for the optimal drought index and timescale combination to detect drought: a case study from the lower Jinsha River basin, China. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2018, 22, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Shukla, S.; Thiaw, W.M.; Rowland, J.; Hoell, A.; McNally, A.; Husak, G.; Novella, N.; Budde, M.; Peters-Lidard, C. Recognizing the famine early warning systems network: over 30 years of drought early warning science advances and partnerships promoting global food security. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2019, 100, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaona, J.; Quintana-Seguí, P.; Escorihuela, M.J.; Boone, A.; Llasat, M.C. Interactions between precipitation, evapotranspiration and soil-moisture-based indices to characterize drought with high-resolution remote sensing and land-surface model data. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2022, 22, 3461–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Peng, J.; Dyer, E.; Miralles, D.G.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Funk, C.; Beck, H.E.; Asfaw, D.T.; Singer, M.B.; Dadson, S.J. Global High-Resolution Drought Indices for 1981-2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2023, 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, W.J.J.V.M. Rainfall deciles as drought indicators. Bureau of Meteorology 1967, 48, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, P.; Roderick, M.L.; Ukkola, A.M.; Wada, Y. The aridity Index under global warming. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundstein, A. Evaluation of climate change over the continental United States using a moisture index. Climatic Change 2009, 93, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Huang, S.; Huang, Q.; Wang, H.; Fang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Assessing socioeconomic drought based on an improved Multivariate Standardized Reliability and Resilience Index. Journal of Hydrology 2019, 568, 904–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiani, R.R.; Suharto, B.; Suharyanto, A. Hydrological Drought Index Based on Discharge. In Drought-Impacts and Management; 2022.

- Hänsel, S.; Schucknecht, A.; Matschullat, J. The Modified Rainfall Anomaly Index (mRAI)—is this an alternative to the Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI) in evaluating future extreme precipitation characteristics? Theoretical and applied climatology 2016, 123, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; AghaKouchak, A.; Nakhjiri, N.; Farahmand, A. Global integrated drought monitoring and prediction system. Scientific Data 2014, 1, 140001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami Bahman Beiglou, P.; Luo, L.; Tan, P.-N.; Pei, L. Automated Analysis of the US Drought Monitor Maps With Machine Learning and Multiple Drought Indicators. Frontiers in Big Data 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, M.J.; Alvord, C.; Lowrey, J. Drought indices. Intermountain west climate summary 2007, 3, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.J.; Svoboda, M.D.; Wiihite, D.A.; Vanyarkho, O.V. Monitoring the 1996 drought using the standardized precipitation index. Bulletin of the American meteorological society 1999, 80, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim Jr, R.R. A review of twentieth-century drought indices used in the United States. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2002, 83, 1149–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, R.R.; Brewer, M.J. The Global Drought Monitor Portal: The Foundation for a Global Drought Information System. Earth Interactions 2012, 16, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, R.R.; Guard, C.; Lander, M.A.; Bukunt, B. USAPI USDM: Operational Drought Monitoring in the U.S.-Affiliated Pacific Islands. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirwa, H.; Li, F.; Qiao, Y.; Measho, S.; Muhirwa, F.; Tian, C.; Leng, P.; Ingabire, R.; Itangishaka, C.A. Climate Change-Drylands-Food Security Nexus in Africa: From the Perspective of Technical Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, A.; Moneo, M.; Quiroga, S. Methods for evaluating social vulnerability to drought. In Coping with Drought Risk in Agriculture and Water Supply Systems: Drought Management and Policy Development in the Mediterranean; Springer: 2009; pp. 153-159.

- Isard, S.A.; Welford, M.R.; Hollinger, S.E. A SIMPLE SOIL MOISTURE INDEX TO FORECAST CROP YIELDS. Physical Geography 1995, 16, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, T. Agricultural drought over water-scarce Central Asia aggravated by internal climate variability. Nature Geoscience 2023, 16, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.E.; Geli, H.M.E.; Hayes, M.J.; Smith, K.H. Building an Improved Drought Climatology Using Updated Drought Tools: A New Mexico Food-Energy-Water (FEW) Systems Focus. Frontiers in Climate 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhasz, T.; Kornfield, J. The Crop Moisture Index: Unnatural Response to Changes in Temperature. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 1978, 17, 1864–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathne, A.; Gad, E.; Disfani, M.; Sivanerupan, S.; Wilson, J. Review of calculation procedures of Thornthwaite Moisture Index and its impact on footing design. Aust. Geomech. J 2016, 51, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Keetch, J.J.; Byram, G.M. A drought index for forest fire control; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment …: 1968; Volume 38.

- Keyantash, J.; Dracup, J.A. The quantification of drought: an evaluation of drought indices. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2002, 83, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khansalari, S.; Raziei, T.; Mohebalhojeh, A.R.; Ahmadi-Givi, F. Moderate to heavy cold-weather precipitation occurrences in Tehran and the associated circulation types. Theoretical and applied climatology 2018, 131, 985–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, S.; Lee, S.J.; Shaimerdenova, A.; Kim, J.; Park, E.; Lee, W.; Kim, G.S.; Kim, N.; Kim, T.H.; et al. Developing spatial agricultural drought risk index with controllable geo-spatial indicators: A case study for South Korea and Kazakhstan. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2021, 54, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Okumu, C.; Tsegai, D.; Pandey, R.P.; Rees, G. Less to lose? Drought impact and vulnerability assessment in disadvantaged regions. Water 2020, 12, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundel, D.; Bodenhausen, N.; Jørgensen, H.B.; Truu, J.; Birkhofer, K.; Hedlund, K.; Mäder, P.; Fliessbach, A. Effects of simulated drought on biological soil quality, microbial diversity and yields under long-term conventional and organic agriculture. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2020, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laimighofer, J.; Laaha, G. How standard are standardized drought indices? Uncertainty components for the SPI & SPEI case. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 613, 128385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Hong, E.-M.; Jang, W.-J.; Kim, S.-J. Assessment of socio-economic drought information using drought-related Internet news data (Part A: Socio-economic drought data construct and evaluation socio-economic drought information). International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 75, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeper, R.D.; Bilotta, R.; Petersen, B.; Stiles, C.J.; Heim, R.; Fuchs, B.; Prat, O.P.; Palecki, M.; Ansari, S. Characterizing U.S. drought over the past 20 years using the U.S. drought monitor. International Journal of Climatology 2022, 42, 6616–6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, F.; Coats, S.; Stocker, T.F.; Pendergrass, A.G.; Sanderson, B.M.; Raible, C.C.; Smerdon, J.E. Projected drought risk in 1.5°C and 2°C warmer climates. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44, 7419–7428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, X. Evaluation of changes of the Thornthwaite moisture index in Victoria. Australian Geomechanics Journal 2015, 50, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Feng, A.; Liu, W.; Ma, X.; Dong, G. Variation of aridity index and the role of climate variables in the Southwest China. Water 2017, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindoso, D.P.; Eiró, F.; Bursztyn, M.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Nasuti, S. Harvesting Water for Living with Drought: Insights from the Brazilian Human Coexistence with Semi-Aridity Approach towards Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shi, H.; Sivakumar, B. Socioeconomic Drought Under Growing Population and Changing Climate: A New Index Considering the Resilience of a Regional Water Resources System. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2020, 125, e2020JD033005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, L.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, X.; Yuan, F.; Jiang, S. Sensitivity analysis of standardization procedures in drought indices to varied input data selections. Journal of Hydrology 2016, 538, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukas, A.; Vasiliades, L.; Dalezios, N. Intercomparison of meteorological drought indices for drought assessment and monitoring in Greece. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, 2003.

- Ma, M.; Ren, L.; Yuan, F.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Kong, H.; Gong, L. A new standardized Palmer drought index for hydro-meteorological use. Hydrological Processes 2014, 28, 5645–5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, P.; Rigi, A.; Miri Kamak, M. Evaluating the sensitivity of precipitation-based drought indices to different lengths of record. Journal of Hydrology 2019, 579, 124181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardian, J. The role of spatial scale in drought monitoring and early warning systems: a review. Environmental Reviews 2022, 30, 438–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, J.; Bathke, D.J.; Burkardt, N.; Cravens, A.E.; Haigh, T.; Hall, K.R.; Hayes, M.J.; Jedd, T.; Poděbradská, M.; Wickham, E. Ecological Drought: Accounting for the Non-Human Impacts of Water Shortage in the Upper Missouri Headwaters Basin, Montana, USA. Resources 2018, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, T.B.; Doesken, N.J.; Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, 1993.

- Mehran, A.; Mazdiyasni, O.; AghaKouchak, A. A hybrid framework for assessing socioeconomic drought: Linking climate variability, local resilience, and demand. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2015, 120, 7520–7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, I.; Siebert, S.; Döll, P.; Kusche, J.; Herbert, C.; Eyshi Rezaei, E.; Nouri, H.; Gerdener, H.; Popat, E.; Frischen, J.; et al. Global-scale drought risk assessment for agricultural systems. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 20, 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, J.; Horváth, S.; Makra, L.; Dunkel, Z. The Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) as an indicator of soil moisture. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 2005, 30, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjo, R.; Royé, D.; Martin-Vide, J. Meteorological drought lacunarity around the world and its classification. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, R.; Brenkert, A.; Malone, E.L. Measuring vulnerability: a trial indicator set. Pacific Northwest Laboratories 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, R. Drought Indices. In Drought Assessment; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2010; pp. 160–204. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA/NCEI. U.S. Drought Monitor. 2023.

- Olukayode Oladipo, E., 1985. A comparative performance analysis of three meteorological drought indices. Journal of Climatology 5(6), 655-664.

- Orimoloye, I.R. Agricultural Drought and Its Potential Impacts: Enabling Decision-Support for Food Security in Vulnerable Regions. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Zaitchik, B.F.; Badr, H.S.; Christian, J.I.; Tadesse, T.; Otkin, J.A.; Anderson, M.C. Flash drought onset over the contiguous United States: sensitivity of inventories and trends to quantitative definitions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozceylan, D.; Coskun, E. The relationship between Turkey’s Provinces’ development levels and social and economic vulnerability to disasters. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, W.C. Meteorological drought; US Department of Commerce, Weather Bureau: 1965; Volume 30.

- Pan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lü, H.; Yagci, A.L.; Fu, X.; Liu, E.; Xu, H.; Ding, Z.; Liu, R. Accuracy of agricultural drought indices and analysis of agricultural drought characteristics in China between 2000 and 2019. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 283, 108305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Sur, C.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, J.-S. Ecological drought monitoring through fish habitat-based flow assessment in the Gam river basin of Korea. Ecological Indicators 2020, 109, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergrass, A.G.; Meehl, G.A.; Pulwarty, R.; Hobbins, M.; Hoell, A.; AghaKouchak, A.; Bonfils, C.J.; Gallant, A.J.; Hoerling, M.; Hoffmann, D. Flash droughts present a new challenge for subseasonal-to-seasonal prediction. Nature Climate Change 2020, 10, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perianes-Rodriguez, A.; Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J. Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. Journal of Informetrics 2016, 10, 1178–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prăvălie, R.; Bandoc, G. Aridity variability in the last five decades in the Dobrogea region, Romania. Arid Land Research and Management 2015, 29, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Hao, X.; Qu, J.J. Monitoring Extreme Agricultural Drought over the Horn of Africa (HOA) Using Remote Sensing Measurements. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziei, T. Revisiting the Rainfall Anomaly Index to serve as a Simplified Standardized Precipitation Index. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 602, 126761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehnia, N.; Alizadeh, A.; Sanaeinejad, H.; Bannayan, M.; Zarrin, A.; Hoogenboom, G. Estimation of meteorological drought indices based on AgMERRA precipitation data and station-observed precipitation data. Journal of Arid Land 2017, 9, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, Y.; Yoshimura, K.; Pokhrel, Y.; Kim, H.; Shiogama, H.; Yokohata, T.; Hanasaki, N.; Wada, Y.; Burek, P.; Byers, E.; et al. The timing of unprecedented hydrological drought under climate change. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savenije, H.H.G. Water scarcity indicators; the deception of the numbers. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Part B: Hydrology, Oceans and Atmosphere 2000, 25, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulcre-Canto, G.; Horion, S.; Singleton, A.; Carrao, H.; Vogt, J. Development of a Combined Drought Indicator to detect agricultural drought in Europe. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 3519–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.H.; Tyre, A.J.; Tang, Z.; Hayes, M.J.; Akyuz, F.A. Calibrating human attention as indicator monitoring# drought in the Twittersphere. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2020, 101, E1801–E1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Plattner, G.-K.; Knutti, R.; Friedlingstein, P. Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standler., J., Stephen.,. Aridity Indexes. In Encyclopedia of World Climatology, Oliver, J.E., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2005; pp. 89-94.

- Svoboda, M.; Fuchs, B. Handbook of drought indicators and indices. Drought and water crises: Integrating science, management, and policy 2016, 155-208.

- Svoboda, M.; LeComte, D.; Hayes, M.; Heim, R.; Gleason, K.; Angel, J.; Rippey, B.; Tinker, R.; Palecki, M.; Stooksbury, D. The drought monitor. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2002, 83, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabari, H.; Willems, P. Sustainable development substantially reduces the risk of future drought impacts. Communications Earth & Environment 2023, 4, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wu, X.; Huang, Z.; Fu, J.; Tan, X.; Deng, S.; Liu, Y.; Gan, T.Y.; Liu, B. Increasing global precipitation whiplash due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tareke, K.A.; Awoke, A.G. Hydrological Drought Analysis using Streamflow Drought Index (SDI) in Ethiopia. Advances in Meteorology 2022, 2022, 7067951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An approach toward a rational classification of climate. Geographical review 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarczyk, T. Classification of low flow and hydrological drought for a river basin. Acta Geophysica 2013, 61, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelló-Sentelles, H.; Franzke, C.L.E. Drought impact links to meteorological drought indicators and predictability in Spain. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 1821–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucco, A.; Zomer, R.J. Global aridity index and potential evapotranspiration (ET0) climate database v2. CGIAR Consort Spat Inf 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, K.P.; Mishra, A.K. How Unusual Is the 2022 European Compound Drought and Heatwave Event? Geophysical Research Letters 2023, 50, e2023GL105453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. World atlas of desertification. Edward Arnold, London 1992, 15-45. [CrossRef]

- Van Loon, A.F. Hydrological drought explained. WIREs Water 2015, 2, 359–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooy, M. A rainfall anomally index independent of time and space, notos. 1965.

- Vanderbilt, K.; Gaiser, E. The international long term ecological research network: a platform for collaboration. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Sanchez-Lorenzo, A.; Revuelto, J.; López-Moreno, J.I.; González-Hidalgo, J.C.; Moran-Tejeda, E.; Espejo, F. Reference evapotranspiration variability and trends in Spain, 1961–2011. Global and Planetary Change 2014, 121, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. Journal of climate 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Peña-Angulo, D.; Beguería, S.; Domínguez-Castro, F.; Tomás-Burguera, M.; Noguera, I.; Gimeno-Sotelo, L.; El Kenawy, A. Global drought trends and future projections. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2022, 380, 20210285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Quiring, S.M.; Peña-Gallardo, M.; Yuan, S.; Domínguez-Castro, F. A review of environmental droughts: Increased risk under global warming? Earth-Science Reviews 2020, 201, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Van der Schrier, G.; Beguería, S.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Lopez-Moreno, J.-I. Contribution of precipitation and reference evapotranspiration to drought indices under different climates. Journal of Hydrology 2015, 526, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.V.; Naumann, G.; Masante, D.; Spinoni, J.; Cammalleri, C.; Erian, W.; Pischke, F.; Pulwarty, R.; Barbosa, P. (Publication Office of the European Union). Drought risk assessment and management: A conceptual framework; 1831-9424; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018 2018; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- WEF. More than 75% of the world could face drought by 2050, UN report warns. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/05/drought-2050-un-report-climate-change/#:~:text=The%20report%20found%20that%20drought,the%20top%20of%20the%20list. (accessed on 07/23 2025).

- Wilhite, D.A. Managing drought risk in a changing climate. Climate Research 2016, 70, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhite, D.A.; Glantz, M.H. Understanding: the drought phenomenon: the role of definitions. Water international 1985, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhou, X.; Yu, Z.; Krysanova, V.; Wang, B. Drought projection based on a hybrid drought index using Artificial Neural Networks. Hydrological Processes 2015, 29, 2635–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarafshani, K.; Sharafi, L.; Azadi, H.; Van Passel, S. Vulnerability assessment models to drought: toward a conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, A.; Sadiq, R.; Naser, B.; Khan, F.I. A review of drought indices. Environmental Reviews 2011, 19, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, N.; Sheng, H.; Ip, C.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Sang, Z.; Tadesse, T.; Lim, T.P.Y.; Rajabifard, A.; et al. Urban drought challenge to 2030 sustainable development goals. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 693, 133536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y. Trends in pan evaporation and reference and actual evapotranspiration across the Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2007, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Singh, V.P.; Lin, Q.; Ning, S.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhou, R.; Ma, Q. Agricultural drought characteristics in a typical plain region considering irrigation, crop growth, and water demand impacts. Agricultural Water Management 2023, 282, 108266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Ma, X.; Yao, W.; Liu, Y.; Du, Z.; Yang, P.; Yao, Y. Improved Drought Monitoring Index Using GNSS-Derived Precipitable Water Vapor over the Loess Plateau Area. Sensors 2019, 19, 5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).