Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Reagents

2.2. Configuration of a Simplified Deuteration Apparatus Used for Deuteration

2.3. Procedure for Deuteration of Amino Acids

2.4. Analytical Methods Using NMR to Determine the Deuteration Level of Amino Acids

2.5. Measurement of Optical Rotation

2.6. Liquid Chromatography Setup for Enantiomeric Separation

2.7. Fluorescence Measurement Method for Evaluating UV-Induced Degradation and Acid-Induced Changes

2.8. Crystallization

3. Results and Discussion

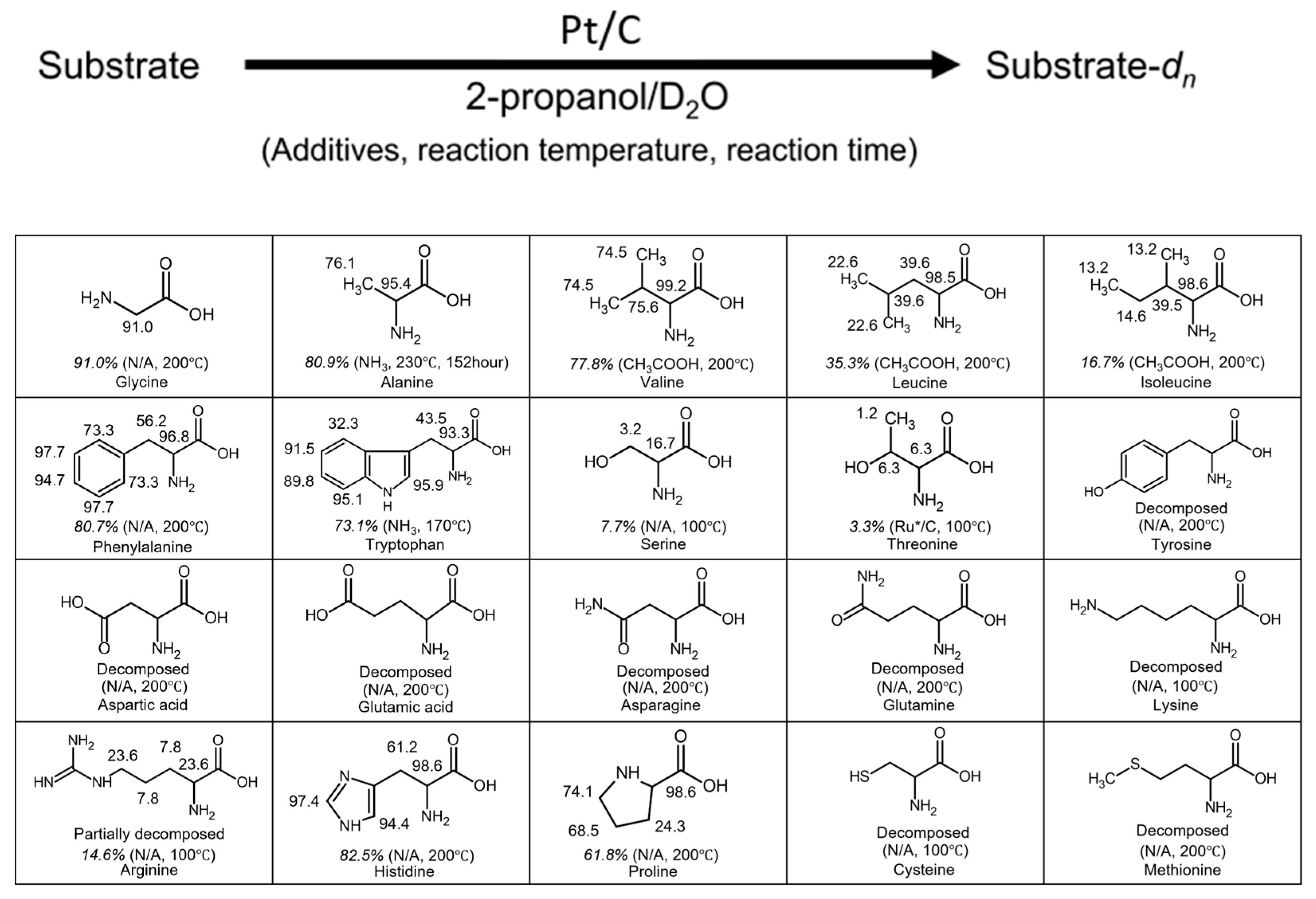

3.1. Deuteration of 20 Proteinogenic Amino Acids

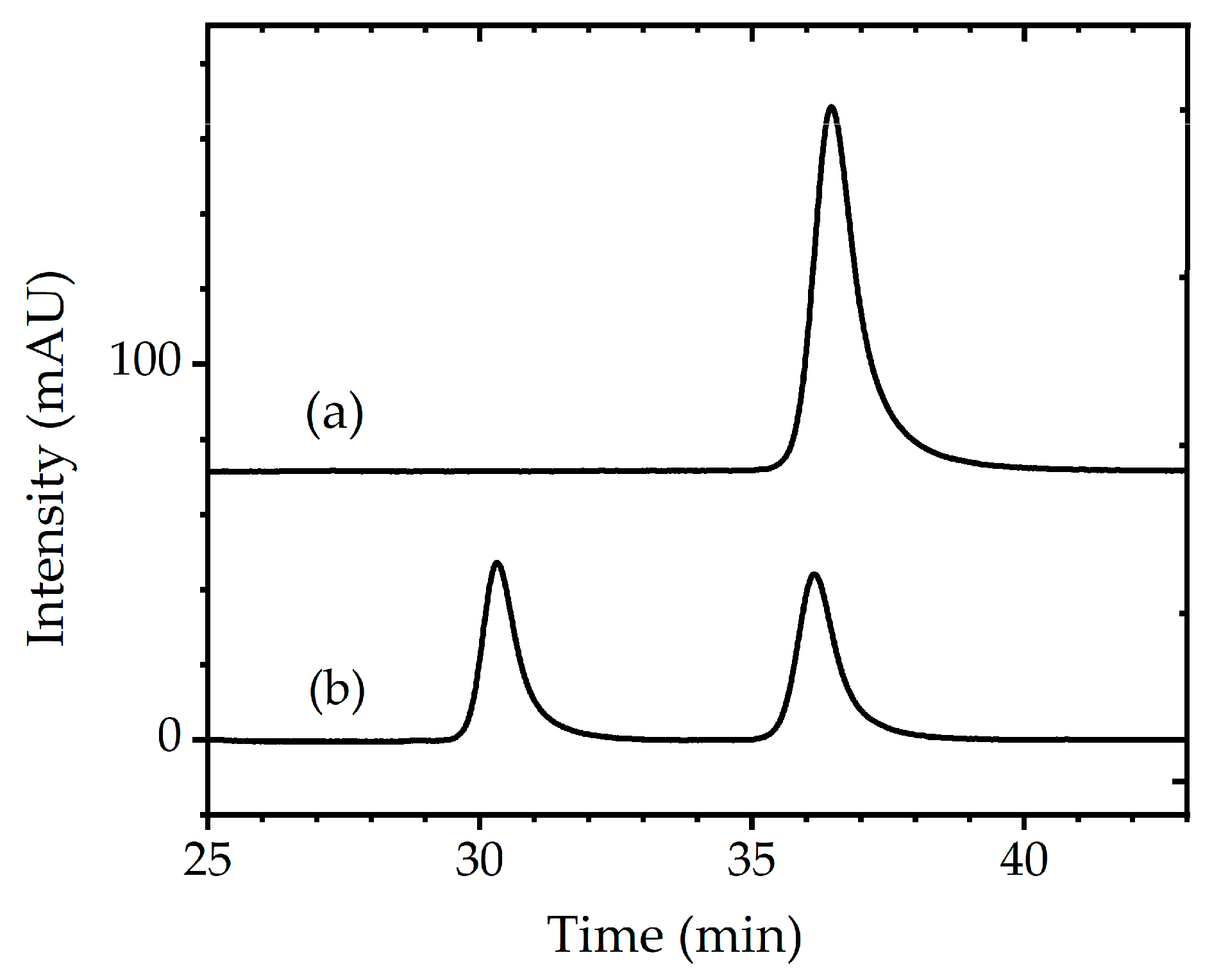

3.2. Chiral Separation of Deuterated Tryptophan

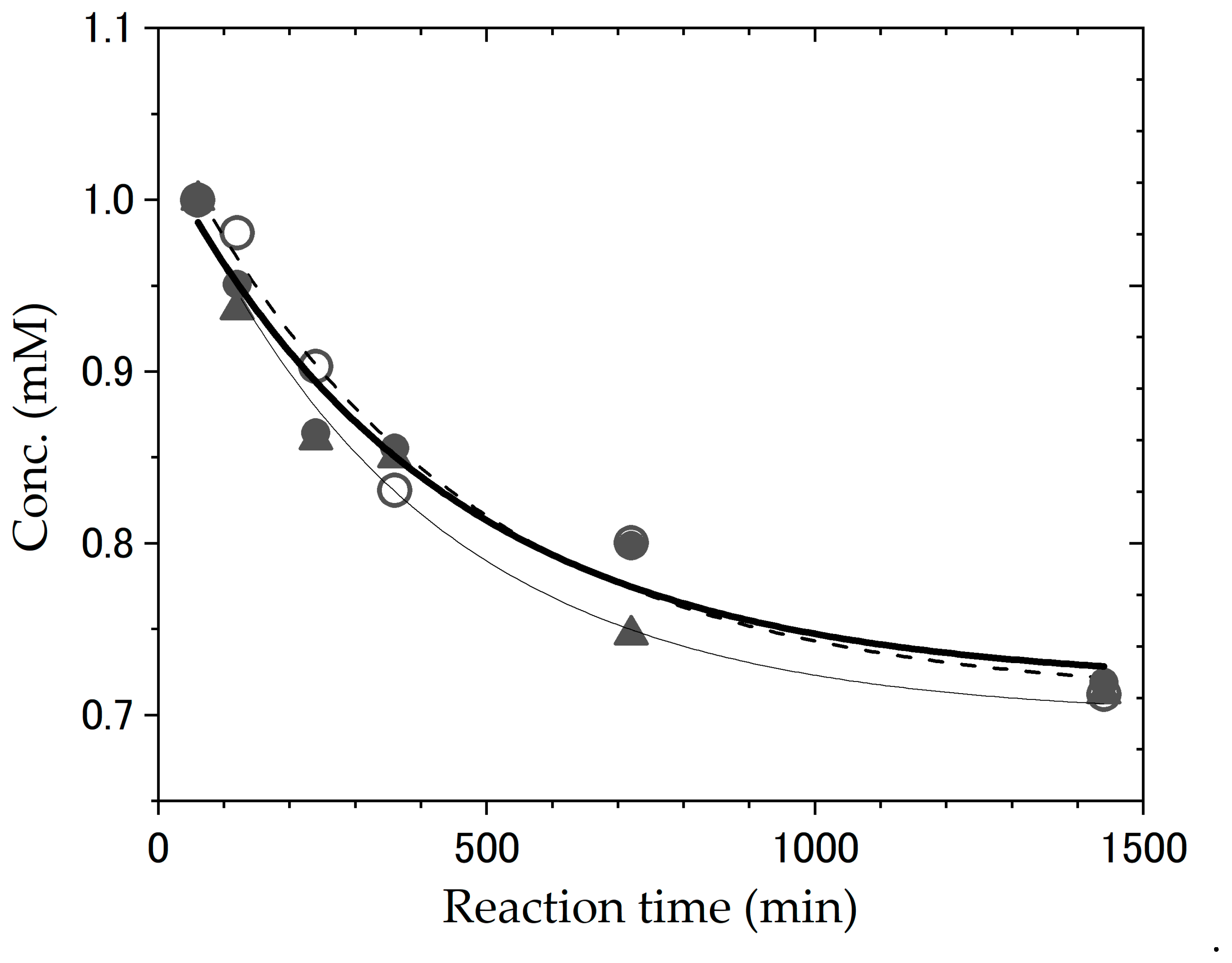

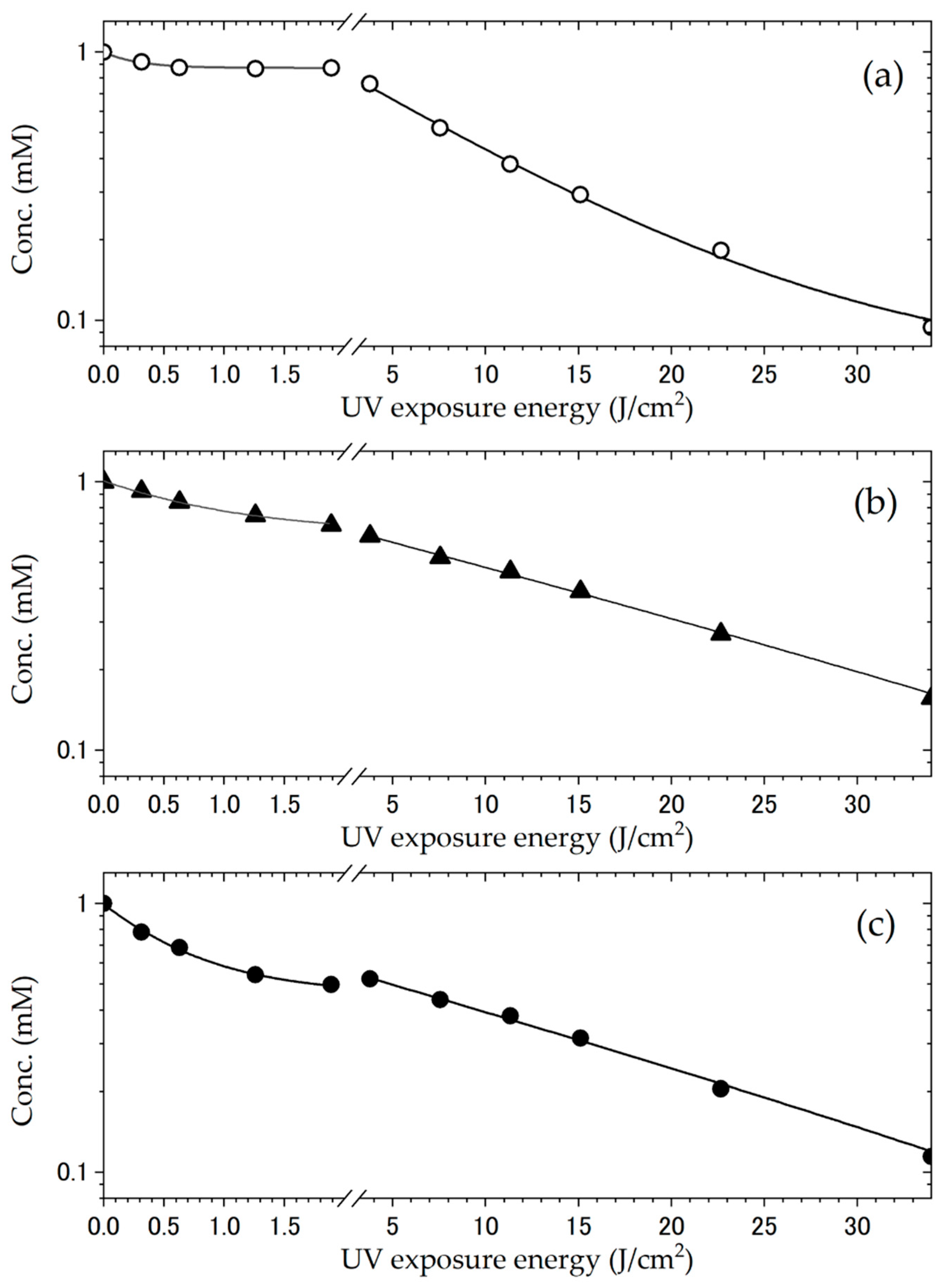

3.3. Physicochemical Characterization of Deuterated Tryptophan

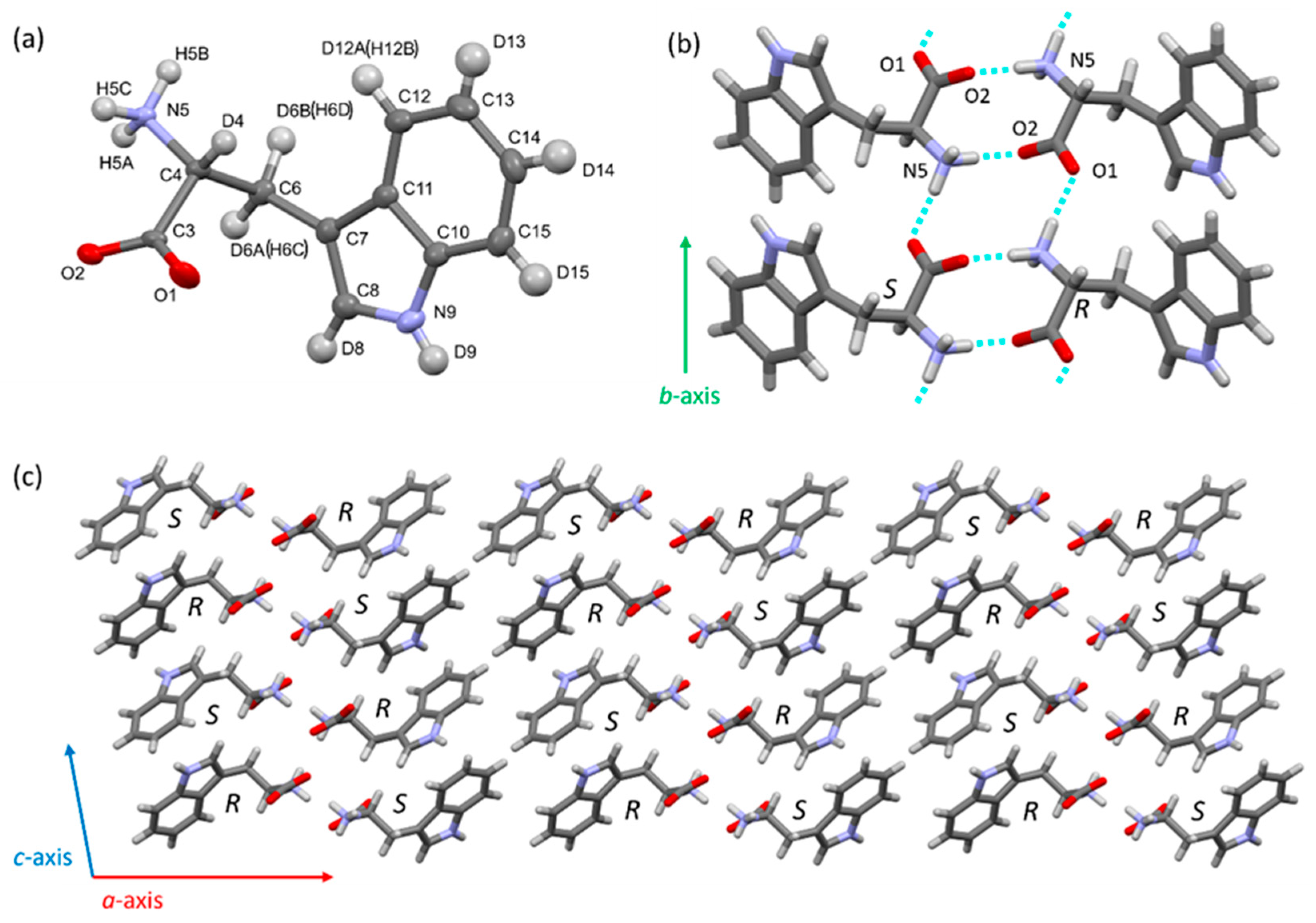

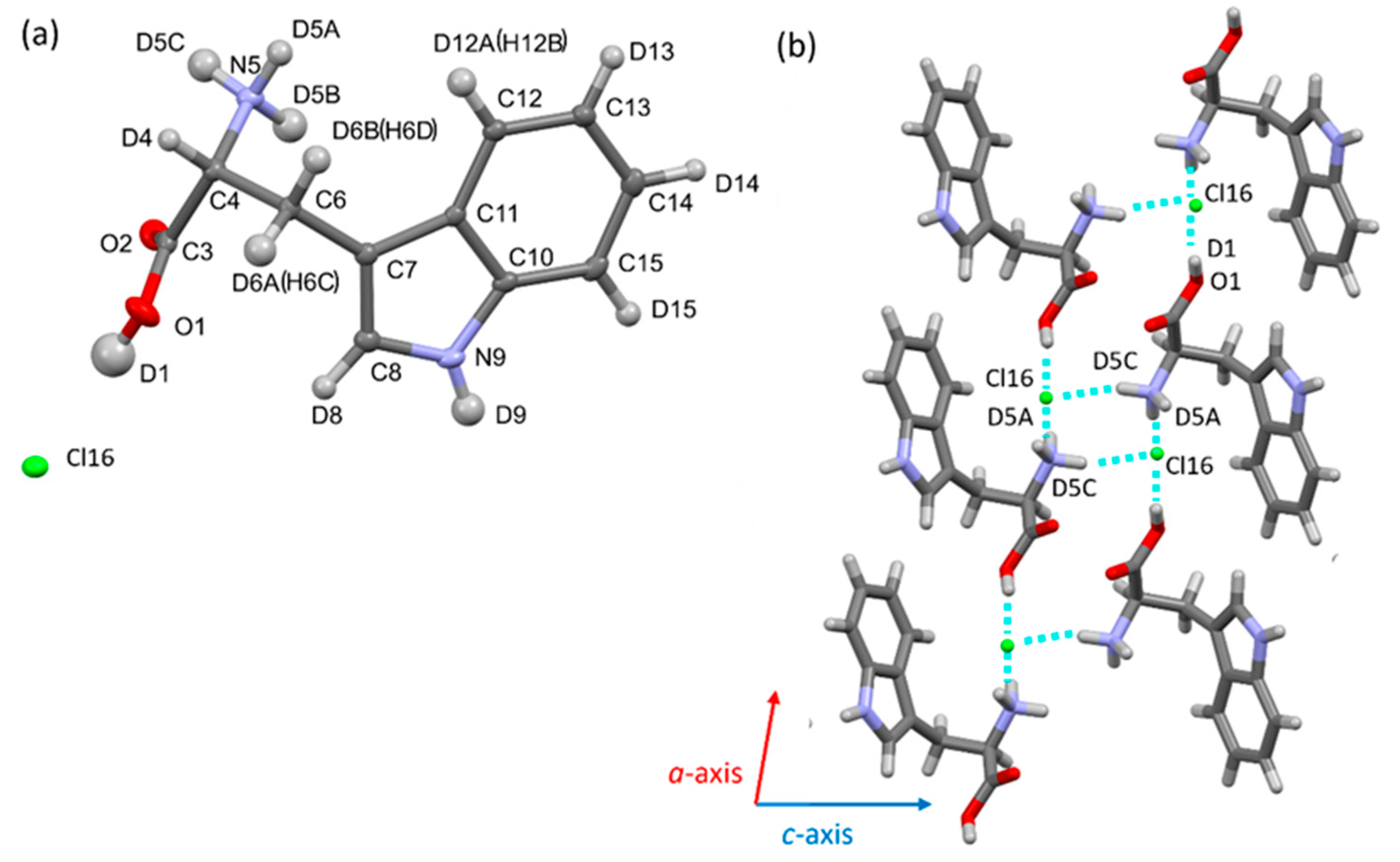

3.4. Structural Comparison Between Protonated and Deuterated Tryptophan Crystals

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| L-Trp | The optically active L-form of tryptophan |

| D-Trp | The optically active D-form of tryptophan |

| h-Trp | Protiated tryptophan |

| d-Trp | Deuterated tryptophan |

| d-L-Trp | Deuterated L-form of tryptophan |

| d-D-Trp | Deuterated D-form of tryptophan |

References

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Mine, A.; Shikida, N.; Takahashi, K.; Miyairi, K.; Shimbo, K.; Kikuchi, Y.; Konishi, A. Single-chain tandem macrocyclic peptides as a scaffold for growth factor and cytokine mimetics. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Groom, C.R. The druggable genome. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002, 1, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schousboe, A.; Bak, L.K.; Waagepetersen, H.S. Astrocytic control of biosynthesis and turnover of the neurotransmitters glutamate and GABA. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höglund, E.; Øverli, Ø.; Winberg, S. Tryptophan metabolic pathways and brain serotonergic activity: A comparative review. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, D.M.; Dawes, M.A.; Wurtman, C.; et al. L-tryptophan: Basic metabolic functions, behavioral research and therapeutic indications. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2009, 2, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Wang, D.; Kim, A.K.; Lau, E.; Lin, A.J.; Liem, D.A.; Zhang, J.; Zong, N.C.; Lam, M.P.Y.; Ping, P. Metabolic labeling reveals proteome dynamics of mouse mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2012, 11, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbeson, S.L.; Tung, R.D. Deuterium medicinal chemistry: A new approach to drug discovery and development. MedChem News 2014, 24, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russak, E.M.; Bednarczyk, E.M. Impact of deuterium substitution on the pharmacokinetics of pharmaceuticals. Ann. Pharmacother. 2019, 53, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, E.; Chen, J.C.-H.; Fisher, S.Z. Neutron crystallography for the study of hydrogen bonds in macromolecules. Molecules 2017, 22, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibazaki, C.; Shimizu, R.; Kagotani, Y.; Ostermann, A.; Schrader, T.E.; Adachi, M. Direct observation of the protonation states in the mutant green fluorescent protein. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, S. Small-angle neutron scattering contrast variation studies of biological complexes: Challenges and triumphs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2022, 74, 102375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.P. Orientation of the headgroup of phosphatidylinositol in a model biomembrane as determined by neutron diffraction. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 8393–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, B.; Krishnakumar, V.; Gunanathan, C. Selective α-Deuteration of Amines and Amino Acids Using D2O. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5892–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- [15_ CST24Mencia] Mencia, G.; Rouan, P.; Fazzini, P.F.; Kulyk, H. Catalytic enantiospecific deuteration of complex amino acid mixtures with ruthenium nanoparticles. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 4904–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawama, Y.; Matsuda, T.; Moriyama, S.; Ban, K.; Fujioka, H.; Kamiya, M.; Shou, J.; Ozeki, Y.; Akai, S.; Sajiki, H. Unprecedented regioselective deuterium-incorporation of alkyltrimethylammonium chlorides and Raman analysis. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2023, e202200710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawama, Y.; Park, K.; Yamada, T.; Sajiki, H. New gateways to the platinum group metal-catalyzed direct deuterium-labeling method utilizing hydrogen as a catalyst activator. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 66, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaki, H.; Ohtaki, R.; Maegawa, T.; Monguchi, Y.; Sajiki, H. Novel Pd/C-catalyzed redox reactions between aliphatic secondary alcohols and ketones under hydrogenation conditions: Application to H–D exchange reaction and the mechanistic study. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawama, Y.; Park, K.; Yamada, T.; Sajiki, H. New gateways to the platinum group metal-catalyzed direct deuterium-labeling method utilizing hydrogen as a catalyst activator. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 66, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutsu-Suyama, K.; Ueda, M.; Shibazaki, C.; Fisher, Z. Development of a Simple and Easy Chemical Deuteration System. CROSS Rep. 2024, 2024, 001. [Google Scholar]

- Shibazaki, C.; Suzuki, H.; Ikegami, T.; Yoshida, K.; Oku, T.; Adachi, M.; Akutsu-Suyama, K. Recycling of Used Heavy Water and Its Application to Amino Acid Deuteration. JSP Conf. Proc. 2024, submitting. [Google Scholar]

- Munz, D.; Webster-Gardiner, M.; Fu, R.; Strassner, T.; Goddard, W.A., III.; Gunnoe, T.B. Proton or metal? The H/D exchange of arenes in acidic solvents. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Saunthwal, R.K.; Verma, A.K. Base-mediated deuteration of organic molecules: A mechanistic insight. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 10612–10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, T.; Aoki, F.; Mizumoto, T.; Maejima, T.; Esaki, H.; Maegawa, T.; Monguchi, Y.; Sajiki, H. Facile and convenient method of deuterium gas generation using a Pd/C-catalyzed H2-D2 exchange reaction and its application to synthesis of deuterium-labeled compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3371–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovinger, G.J.; Sak, M.H.; Jacobsen, E.N. Catalysis of an SN2 pathway by geometric preorganization. Nature 2024, 632, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E. Effects of L-tryptophan on sleepiness and on sleep. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1982, 17, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.N. How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs. J. Psychiatr. Neurosci. 2007, 32, 394–399. [Google Scholar]

- Bellmaine, S.; Schnellbaecher, A.; Zimmer, A. Reactivity and degradation products of tryptophan in solution and proteins. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 696–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, N.; Onoue, S.; Tsuda, Y. Photoreactivity of Amino Acids: Tryptophan-Induced Photochemical Events via Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Anal. Sci. 2007, 23, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Finley, J.W. Methods of tryptophan analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1971, 19, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Cuq, J.-L. Chemistry, analysis, nutritional value, and toxicology of tryptophan in food. A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1988, 36, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T. The Decomposition of Tryptophan in Acid Solutions: Specific Effect of Hydrochloric Acid. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1981, 29, 1767–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, Y.; Shibata, T. Heat Decomposition of Amino Acids with Autoclave (Part 1). Jpn. J. Home Econ. 1970, 21, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöneich, C. Novel Chemical Degradation Pathways of Proteins Mediated by Tryptophan Oxidation: Tryptophan Side Chain Fragmentation. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 70, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Fei, W.; Ji, J.; Yang, Y. Degradation of Tryptophan by UV Irradiation: Influencing Parameters and Mechanisms. Water 2021, 13, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, N.; Uchida, H.; Saito, T. The Damaging Effect of UV-C Irradiation on Lens α-Crystallin. Mol. Vis. 2004, 10, 814–820. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Y.; Kanematsu, Y.; Sakagami, H.; Rivera Rocabado, D.S.; Shimazaki, T.; Tachikawa, M.; Ishimoto, T. Hydrogen/Deuterium Transfer from Anisole to Methoxy Radicals: A Theoretical Study of a Deuterium-Labeled Drug Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Xue, B.; Rehak, P.; Jacoby, G.; Ji, W.; Shimon, L.J.W.; Beck, R.; Král, P.; Cao, Y.; Gazit, E. Self-Assembly of Aromatic Amino Acid Enantiomers into Supramolecular Materials of High Rigidity. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1694–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübschle, C.B.; Messerschmidt, M.; Luger, P. Crystal Structure of DL-Tryptophan at 173 K. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2004, 39, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Solid Tryptophan as a Pseudoracemate: Physicochemical and Crystallographic Characterization. Chirality 2015, 27, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takigawa, T.; Ashida, T.; Sasada, Y.; Kakudo, M. The Crystal Structures of L-Tryptophan Hydrochloride and Hydrobromide. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1966, 39, 2369–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| [α]D20 (deg·mL·g−1·dm-1) ±SD (20℃、598nm) | Sample |

| -32.5925 ± 0.0199 | L-Tryptophan (h-L-Trp) |

| -1.6525 ± 0.2656 | Deuterated tryptophan (d-Trp) |

| kobs(second reaction) and ΔEa | kobs(first reaction) and ΔEa | Sample |

| 0.0061 min-1 | 0.230 min-1 | h-L-Trp |

| 0.0024 min-1, 0.61 kcal/mol | 0.065 min-1, 0.74 kcal/mol | d40-Trp (40% deuterated) |

| 0.0027 min-1, 0.48 kcal/mol | 0.080 min-1, 0.55 kcal/mol | d70-Trp (70% deuterated) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).