Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

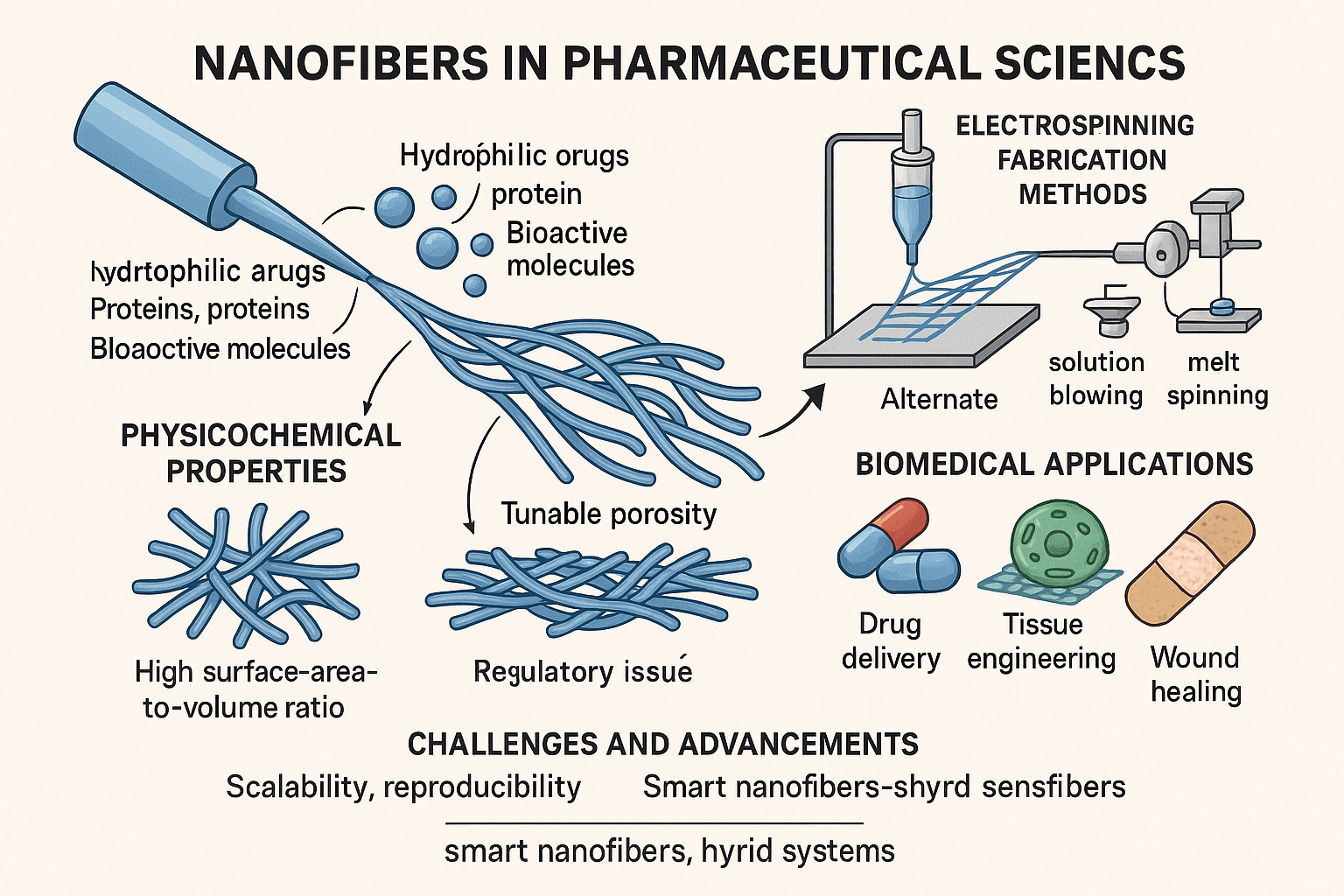

- Introduction to Nanofibers in Pharmaceutical Applications

2. Fabrication Techniques of Nanofibers

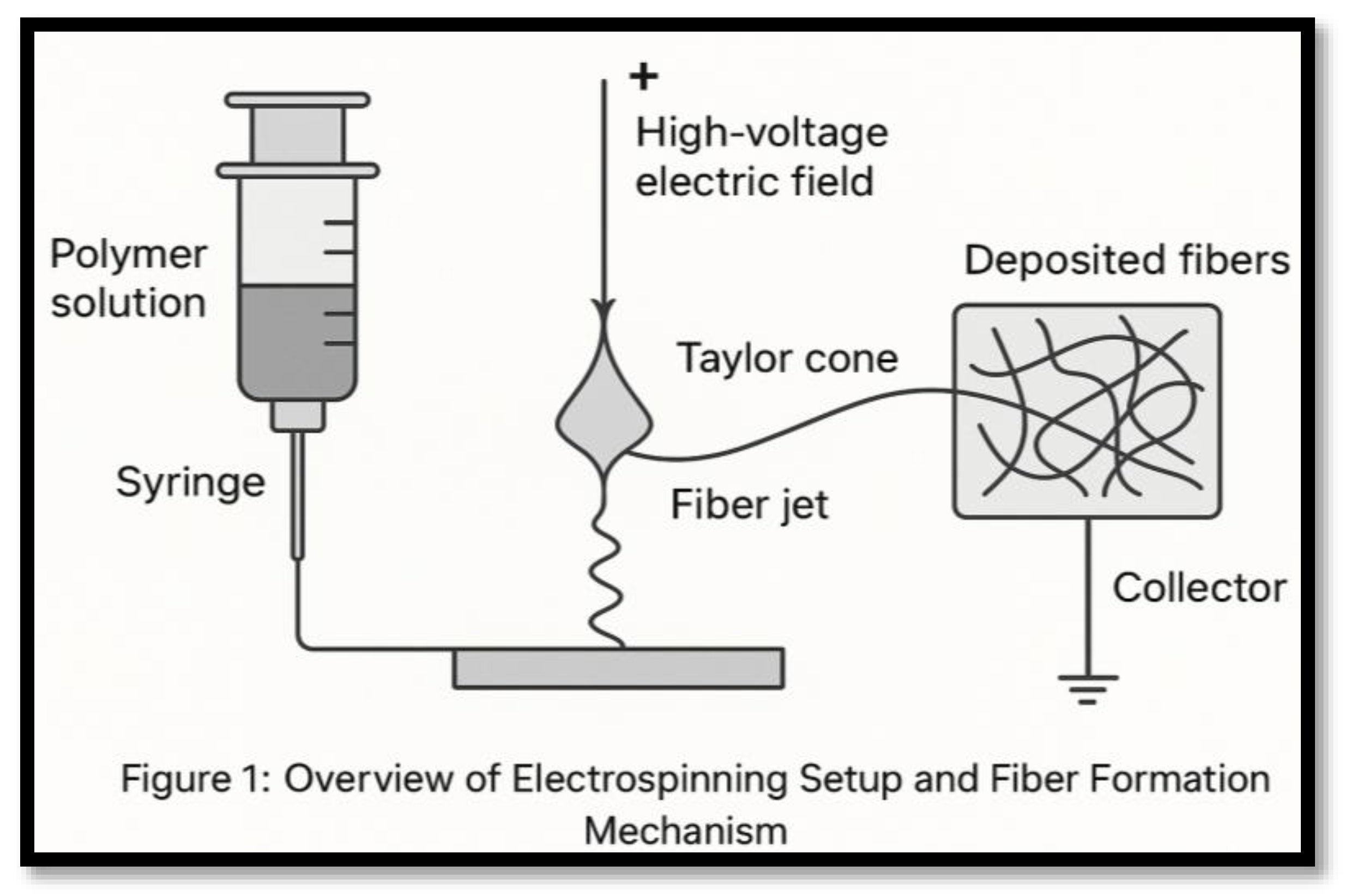

2.1. Electrospinning[6,7,8]

2.2. Alternative Fabrication Techniques for Nanofibers

- Solution Blowing[9]

- No high-voltage requirements, enhancing safety and simplifying equipment needs.

- Higher production rates compared to electrospinning, making it more suitable for industrial scaling.

- The ability to use a wide range of biocompatible polymers and drug-loaded solutions.

- The technique is particularly effective for generating fibers with diameters in the micro- to nanoscale range, although achieving consistent nanometer-level diameters may require optimization.

- 2.

-

Advantages of melt spinning:

- Environmentally friendly and solvent-free, avoiding toxicity concerns and the need for post-processing to remove residual solvents.

- Well-established in manufacturing with high-throughput capability, making it ideal for industrial-scale production.

- Suitable for thermoplastic polymers such as polycaprolactone (PCL), polylactic acid (PLA), and polyethylene glycol (PEG).

-

Challenges:

- Limited to polymers with a defined melting point or thermal processability.

- High processing temperatures may restrict the inclusion of heat-sensitive drugs or biomolecules.

- Control over fiber diameter is less precise compared to electrospinning.

- 3.

- Phase Separation typically involves dissolving a polymer in a solvent, followed by temperature-induced phase demixing (usually by lowering the temperature). The solvent is then removed by freeze-drying, leaving behind a porous nanofibrous matrix.

- Self-Assembly refers to the process by which molecules (e.g., peptides, amphiphilic polymers) spontaneously organize into ordered nanostructures due to non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and ionic interactions.

-

Benefits[18]:

- Exceptional control over fiber architecture and morphology, enabling the design of fibers with bio-mimetic structures.

- Suitable for delicate biopolymers like collagen, chitosan, and self-assembling peptides.

- Allows the integration of bioactive cues, such as cell-adhesion peptides or growth factors, within the nanofiber matrix.

-

Limitations:

- Low scalability and long processing times, which hinder mass production.

- Often requires complex processing conditions and highly pure reagents.

- Applications:

3. Physicochemical Properties of Nanofibers [19,20]

4. Pharmaceutical Applications [21,22,23]

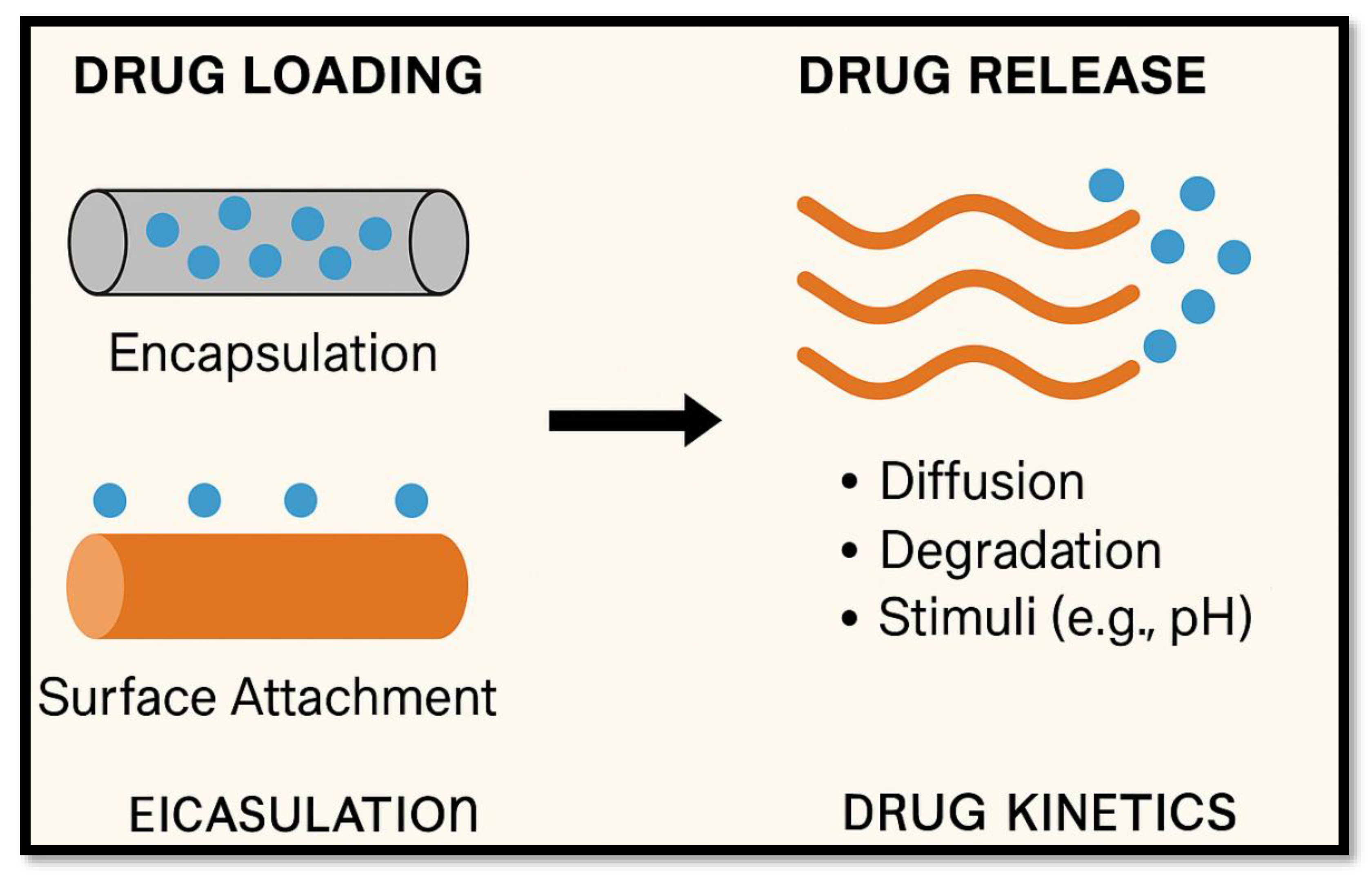

4.1. Drug Delivery Systems

4.2. Wound Healing

- Maintaining moisture balance, facilitating autolytic debridement and reducing scarring.

- Blocking bacterial infiltration due to ultrafine fiber structure and high porosity

- Delivering embedded therapeutics—such as antibiotics, silver nanoparticles, or growth factors—directly into the wound bed, enhancing local efficacy while minimizing systemic exposure.

4.3. Tissue Engineering [24]

- Cell adhesion, due to nanoscale fibrous topology and biochemical cues.

- Cellular proliferation and differentiation are aided by biochemical environment and mechanical support. These scaffolds have enabled regeneration across multiple tissues: skin, cartilage, bone, and neural pathways. Notably, aligned nanofibers foster axonal guidance in nerve repair and improve skeletal tissue regeneration

4.4. Biosensing and Diagnostics [25,26]

- High surface area, enabling dense probe immobilization.

- Rapid analyte diffusion, yielding fast and sensitive signal output, for applications like glucose monitoring or pathogen detection. For instance, nanodiamond–silk fibroin electro spun membranes act as both wound dressings and integrated biosensors for temperature and bacterial activity

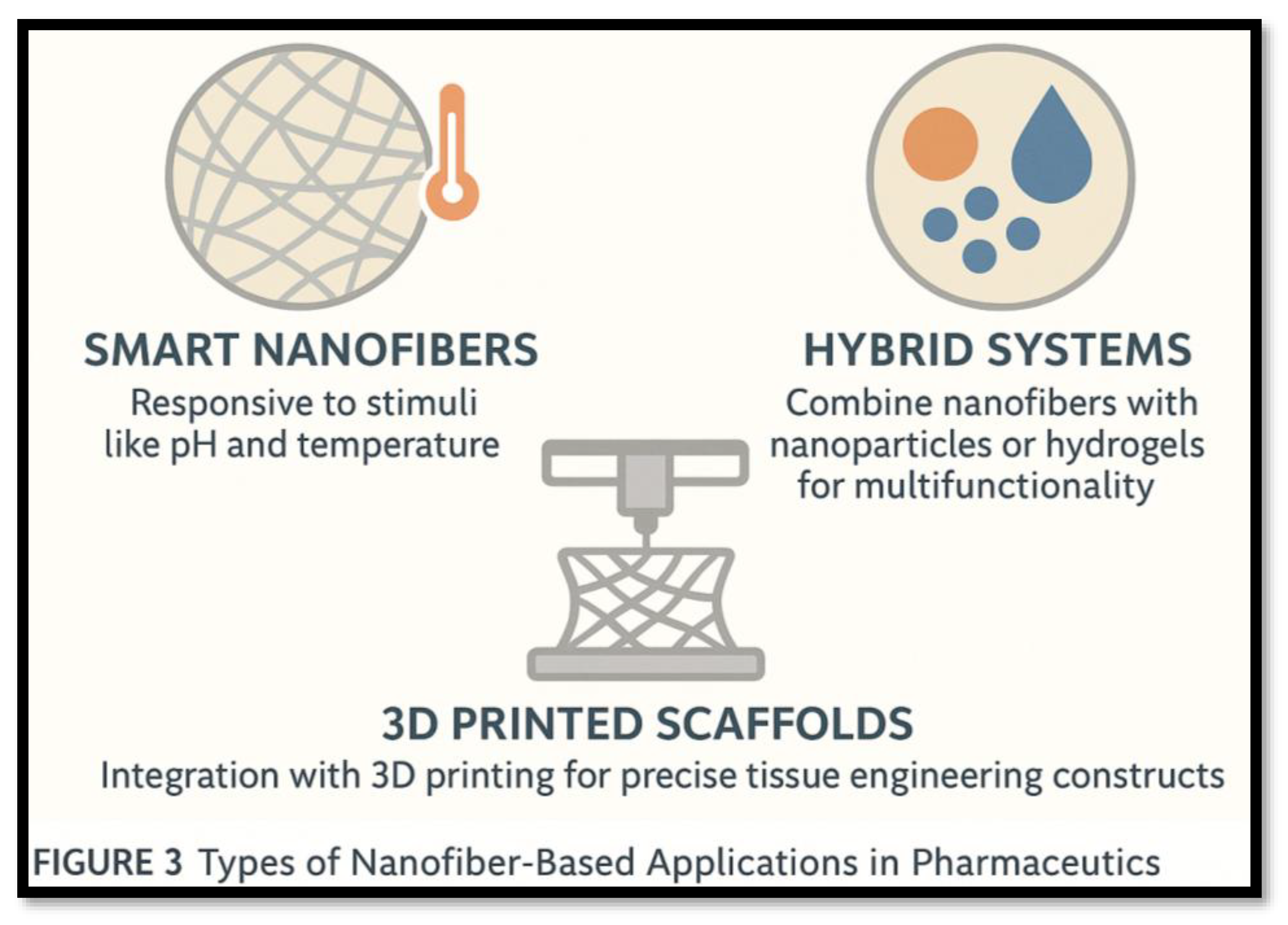

5. Recent Advancements [27]

- Smart Nanofibers: Incorporate stimuli-responsive components (e.g., PCL/PNIPAAm composites) to regulate hydrophilicity or drug release based on temperature or pH

- Hybrid Systems: Meld fibers with nanoparticles or hydrogels to enable multifunctionality—drug delivery plus sensing, imaging, or mechanical reinforcement

- 3D-Printed Scaffolds: Combine electrospun nanofibers with 3D printing to build architecturally precise constructs, ideal for patient-specific tissue implants the types of Nanofiber-Based Applications in Pharmaceutics were shown in the Figure 3.

6. Challenges and Limitations [28]

- Reproducibility: Electrospinning is sensitive to small menu shifts—solution properties, voltage, ambient conditions—which can alter fiber quality

- Scalability: Standard setups are low-throughput; industrial scalability via multi-jet systems faces operational variability and fiber uniformity issues.

- Sterilization: Techniques like gamma irradiation or ethylene oxide may degrade fiber structure or drug components.

- Regulatory Hurdles: Clinical adoption is limited; only topical nanofiber dressings have reached the market, while injectable and systemic systems require extensive safety and efficacy data.

7. Regulatory and Commercial Considerations [29]

- Comprehensive preclinical data on pharmacokinetics and toxicity.

- Controlled manufacturing processes under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP).

- Clear regulatory pathways, addressing nanomedicine-specific concerns regarding biodegradation, metabolism, and long-term safety.

8. Future Perspectives [30]

- Scalable Manufacturing: Development of high-throughput, continuous processes (e.g., multi-nozzle or melt/electro-blowing hybrids).

- Multifunctional/Personalized Systems: Combining imaging agents, sensors, and targeted drug delivery in a single nanofiber platform.

- In Vivo Validation: Conducting large animal and phase-I/II clinical trials to move from prototypes to approved medical products.

- Regulatory Pathways: Establishing standardized characterization, performance criteria, and regulatory guidelines tailored to nanofiber-based systems.

Conclusion:

References

- Bhardwaj N, Kundu SC. Electrospinning: a fascinating fiber fabrication technique. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28(3):325–47. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna S, Fujihara K, Teo WE, Yong T, Ma Z, Ramaseshan R. Electrospun nanofibers: solving global issues. Mater Today. 2006;9(3):40–50. [CrossRef]

- Huang ZM, Zhang YZ, Kotaki M, Ramakrishna S. A review on polymer nanofibers by electrospinning and their applications in nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol. 2003;63(15):2223–53. [CrossRef]

- Greiner A, Wendorff JH. Electrospinning: a fascinating method for the preparation of ultrathin fibers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(30):5670–703.

- Xue J, Wu T, Dai Y, Xia Y. Electrospinning and electrospun nanofibers: methods, materials, and applications. Chem Rev. 2019;119(8):5298–415. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal S, Wendorff JH, Greiner A. Use of electrospinning technique for biomedical applications. Polymer. 2008;49(26):5603–21. [CrossRef]

- Kenry, Lim CT. Nanofiber technology: current status and emerging developments. Prog Polym Sci. 2017;70:1–17. [CrossRef]

- Homayoni H, Ravandi SAH, Valizadeh M. Electrospinning of chitosan nanofibers: processing optimization. Carbohydr Polym. 2009;77(3):656–61. [CrossRef]

- Dash TK, Konkimalla VB. Poly-ε-caprolactone-based formulations for drug delivery and tissue engineering: a review. J Control Release. 2012;158(1):15–33. [CrossRef]

- Gopaiah KV, Krishna KS, Vani P, Sireesha S, Kumar V. Nanoparticle-based delivery system for sustained release of antihypertensive drugs. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2022;15(9):150–155.

- Kaur IP, Kanwar M. Ocular preparations: the formulation approach. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2002;28(5):473–93. [CrossRef]

- Yang X, Shah JD, Wang H. Nanofiber enabled layer-by-layer approaches for drug delivery. J Control Release. 2019;307:196–205.

- Li D, Xia Y. Electrospinning of nanofibers: reinventing the wheel? Adv Mater. 2004;16(14):1151–70.

- Liao I-C, Chew SY, Leong KW. Aligned core–shell nanofibers delivering bioactive proteins. Nanomedicine. 2006;1(4):465–71. [CrossRef]

- Sill TJ, von Recum HA. Electrospinning: applications in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29(13):1989–2006.

- Gopaiah KV, Teja RM, Kumar YS, Prasad PVS, Kumar Y. Formulation and Evaluation of Enzalutamide Cyclodextrin Nanosponges Tablets: In vitro Dissolution Study and In vivo Pharmacokinetics. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2025;15(5): xx–xx. [In Press].

- Zhang Y, Lim CT, Ramakrishna S, Huang ZM. Recent development of polymer nanofibers for biomedical and biotechnological applications. J Mater Sci. 2005;16(10):933–46. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Gao C, Liu X, Shen J. Surface modification of polycaprolactone membrane via entrapment of chitosan-based multilayer for promoting cytocompatibility of human fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 2002;23(24):4889–95.

- Ma Z, Kotaki M, Yong T, He W, Ramakrishna S. Surface engineering of electrospun polyethylene oxide nanofibers for biological application. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2005;26(5):321–6.

- Bhardwaj N, Chouhan D, Mandal BB. Tissue engineered skin and wound healing: current strategies and future directions. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23(24):3455–70. [CrossRef]

- Venugopal J, Low S, Choon AT, Ramakrishna S. Interaction of cells and nanofiber scaffolds in tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;84B(1):34–48. [CrossRef]

- Katti DS, Robinson KW, Ko FK, Laurencin CT. Bioresorbable nanofiber-based systems for wound healing and drug delivery: optimization of fabrication parameters. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;70(2):286–96. [CrossRef]

- Kim K, Luu YK, Chang C, Fang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B, Hadjiargyrou M. Incorporation and controlled release of a hydrophilic antibiotic using poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-based electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds. J Control Release. 2004;98(1):47–56. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Yuan X, Wu L, Han Y, Sheng J. Study on morphology of electrospun poly(vinyl alcohol) mats. Eur Polym J. 2005;41(3):423–32. [CrossRef]

- Emamjomeh SM, Amani A. Biosensors using electrospun nanofibers: recent advances and future directions. Biosens Bioelectron. 2021;171:112722.

- Ghaffari M, Irani M, Atai M, Fekrazad R. Controlled release of metronidazole from polycaprolactone nanofibers for oral wound dressing. Dent Res J. 2016;13(6):504–10.

- Gholipourmalekabadi M, Mozafari M, Ranjbar-Mohammadi M, et al. Electrospun silk fibroin/gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds: from material characterization to in vivo biocompatibility. Nanomedicine. 2018;13(18):2341–55.

- Gopaiah KV, Teja RM, Goud NR, Reddy YP, Reddy BS. Nanostructured Emulsomes for the Enhanced Delivery of Cabazitaxel: A Novel Approach to Cancer Treatment and Drug Release Profiling. Preprints. 2025;2025:161188.

- Chew SY, Wen Y, Dzenis Y, Leong KW. The role of electrospun nanofibers in stem cell biology. Biomaterials. 2006;27(36):5731–42.

- Sundarrajan S, Tan KL, Lim SH, Ramakrishna S. Electrospun nanofibers for air filtration applications. Procedia Eng. 2014;75:159–63. [CrossRef]

| S. NO | Parameter | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Voltage | Affects fiber diameter and uniformity. |

| 2 | Polymer concentration | Controls solution viscosity and spinnability, impacting fiber formation. |

| 3 | Flow rate | Influences fiber morphology and diameter consistency. |

| 4 | The distance between the needle and the collector | Impacts the solvent evaporation rate and fiber formation. |

| S. NO | Polymer | Type | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Biodegradable | Sustained drug delivery |

| 2 | Polylactic acid (PLA) | Biodegradable | Tissue engineering |

| 3 | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) | Water-soluble | Wound healing |

| 4 | Chitosan | Natural | Antibacterial dressing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).