1. Introduction

Let

m be a positive integer and denote by

the set of all probability measures on the measurable space

, with

being the Borel

-algebra on

. Given a Borel measurable function

, consider the functional

which quantifies the variation of the expectation of the measurable function

h due to changing the probability measure from

to

. These variations are often referred to as

probability distribution drifts, in some application areas, see for instance [

1,

2] and [

3]. The functional

is defined when both integrals exist and are finite.

In order to define the expectation of when x is obtained by sampling a probability measure in , the structure formalized below is required.

Definition 1.

A family of elements of indexed by is said to be a conditional probability measure if, for all sets , the map

is Borel measurable. The set of all such conditional probability measures is denoted by .

In this setting, consider the functional

This quantity can be interpreted as the variation of the integral (expectation) of the function

h when the probability measure changes from the joint probability measure

to another joint probability measure

, both in

. This follows from (

2) by observing that

Special attention is given to the quantity

, for some

, with

being the marginal of the joint probability measure

. That is, for all sets

,

Its relevance stems from the fact that it captures the variation of the expectation of the function

h when the probability measure changes from the joint probability measure

to the product of its marginals

. That is,

1.1. Novelty and Contributions

This work makes two key contributions: First, it provides a closed-form expression for the variation

in (

1) for a fixed

and two arbitrary probability measures

and

, formulated explicitly in terms of relative entropies. Second, it derives a closed-form expression for the expected variation

in (

2), again in terms of information measures, for arbitrary conditional probability measures

,

, and an arbitrary probability measure

.

A further contribution of this work is the derivation of specific closed-form expressions for

in (

6), which reveal deep connections with both mutual information [

4,

5] and lautum information [

6]. Notably, when

is a Gibbs conditional probability measure, this variation simplifies (up to a constant factor) to the sum of the mutual and lautum information induced by the joint distribution

.

Although these results were originally discovered in the analysis of generalization error of machine learning algorithms, see for instance [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], where the function

h in (

1) was assumed to represent an empirical risk, this paper presents such results in a comprehensive and general setting that is no longer tied to such assumptions. Also, strong connections with

information projections and Pythagorean identities [

12,

13] are discussed. This new general presentation not only unifies previously scattered insights but also makes the results applicable across a broad range of domains in which changes in the expectation due to variations of the underlying probability measures are relevant.

1.2. Applications

The study of the variation of the integral (expectation) of

h (for some fixed

) due to a measure change from

to

, i.e., the value

in (

1), plays a central role in the definition of

integral probability metrics (IPMs)[

14,

15]. Using the notation in (

1), an IPM results from the optimization problem

for some fixed

and a particular class of functions

. Note for instance that the maximum mean discrepancy is an IPM [

16], as well as the Wasserstein distance of order one [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Other areas of mathematics in which the variation

in (

1) plays a key role is distributionally robust optimization (DRO) [

21,

22] and optimization with relative entropy regularization [

8,

9]. In these areas, the variation

is a central tool. See for instance, [

7,

23]. Variations of the form

in (

1) have also been studied in [

10] and [

11] in the particular case of statistical machine learning for the analysis of generalization error. The central observation is that the generalization error of machine learning algorithms can be written in the form

in (

6). This observation is the main building block of the

method of gaps introduced in [

11], which leads to a number of closed-form expressions for the generalization error involving mutual information, lautum information, among other information measures.

2. Preliminaries

The main results presented in this work involve Gibbs conditional probability measures. Such measures are parametrized by a Borel measurable function

; a

-finite measure

Q on

; and a vector

. Note that the variable

x will remain inactive until

Section 4. Although it is introduced now for consistency, it could be removed altogether from all results presented in this section and

Section 3.

Consider the following function:

Under the assumption that

Q is a probability measure, the function

in (

8) is the cumulant generating function of the random variable

, for some fixed

and

. Using this notation, the definition of the Gibbs conditional probability measure is presented hereunder.

Definition 2 (Gibbs Conditional Probability Measure).

Given a Borel measurable function ; a σ-finite measure Q on ; and a , the probability measure is said to be an -Gibbs conditional probability measure if

for some set ; and for all ,

where the function is defined in (8); stands for the support of the σ-finite measure Q; and the function is the Radon-Nikodym derivative [24,25] of the probability measure with respect to Q.

Note that, while is an -Gibbs conditional probability measure, the measure , obtained by conditioning it upon a given vector , is referred to as an -Gibbs probability measure.

The condition in (

9) is easily met under certain assumptions. For instance, if

h is a nonnegative function and

Q is a finite measure, then it holds for all

. Let

, with

standing for “

P absolutely continuous with respect to

Q”. The relevance of

-Gibbs probability measures relies on the fact that under some conditions, they are the unique solutions to problems of the form,

where

,

, and

denotes the relative entropy (or KL divergence) of

P with respect to

Q.

Definition 3 (Relative Entropy).

Given two σ-finite measures P and Q on the same measurable space, such that P is absolutely continuous with respect to Q, the relative entropy of P with respect to Q is

where the function is the Radon-Nikodym derivative of P with respect to Q.

The connection between the optimization problems (

11) and (

12) and the Gibbs probability measure

in (

10) has been pointed out by several authors. See for instance, [

8] and [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35] for the former; and [

10] together with [

36,

37,

38] for the latter. In these references a variety of assumptions and proof techniques have been used to prove such connections. A general and unified statement of these observations is presented hereunder.

Lemma 1. Assume that the optimization problem in (11) (respectively, in (12)) admits a solution. Then, if (respectively, if ), the probability measure in (10) is the unique solution.

Proof:

For the case in which

, the proof follows the same approach as the proof of [

8]. Alternatively, for the case in which

, the proof follows along the lines of the proof of [

10]. □

The following lemma highlights a key property of -Gibbs probability measures.

Lemma 2.

Given an -Gibbs probability measure, denoted by , with ,

alternatively, if ,

where the function is defined in (8).

Proof:

The proof of (

15) follows from taking the logarithm of both sides of (

10) and integrating with respect to

. As for the proof of (

14), it follows by noticing that for all

, the Radon-Nikodym derivative

in (

10) is strictly positive. Thus, from [

39], it holds that

. Hence, taking the negative logarithm of both sides of (

10) and integrating with respect to

Q leads to (

14). Finally, the equalities in (

16) and (

17) follow from Lemma 1 and (

15). □

Lemma 2, at least equalities (

15), (

16), and (

17), can be seen as an immediate restatement of Donsker-Varadhan variational representation of the relative entropy [

40]. Alternative interesting proofs for (

14) have been presented by several authors including [

10] and [

35]. A proof for (

15) appears in [

29] in the specific case of

.

The following lemma introduces the main building block of this work, which is a characterization of the variation from the probability measure

in (

10) to an arbitrary measure

, i.e.,

. Such a result appeared for the first time in [

7] for the case in which

; and in [

10] for the case in which

, in different contexts of statistical machine learning. A general and unified statement of such results is presented hereunder.

Lemma 3.

Consider an -Gibbs probability measure, denoted by , with and . For all ,

Proof:

The proof follows along the lines of the proofs of [

7] for the case in which

; and in [

10] for the case in which

. A unified proof is presented hereunder by noticing that for all

,

where (

20) follows from [

39]; (

22) follows from [

39] and (

10); and (

23) follows from (

15). □

It is interesting to highlight that

in (

18) characterizes the variation of the expectation of the function

, when

(resp.

) and the probability measure changes from the solution to the optimization problem (

11) (resp. (

12)) to an alternative measure

P. This result takes another perspective if it is seen in the context of information projections [

13]. Let

Q be a probability measure and

be a convex set. From [

13], it holds that for all measures

,

where,

satifies

In the particular case in which the set

in (

24) satisfies

for some real

c, with the vector

x and the function

h defined in Lemma 3, the optimal measure

in (

25) is the Gibbs probability measure

in (

10), with

chosen to satisfy

The case in which the measure

Q in (

25) is a

-finite measure, for instance, either the Lebesgue measure or the counting measure, respectively leads to the classical framework of differential entropy maximization or discrete entropy maximization, which have been studied under particular assumptions on the set

in [

36,

37] and [

38].

When the reference measure

Q is a probability measure, under the assumption that (

27) holds, it follows from [

13] that for all

, with

in (

26),

which is known as the

Pythagorean theorem for relative entropy. Such a geometric interpretation follows from admitting relative entropy as an analog of squared Euclidean distance. The first appearance of such a “Pythagorean theorem” was in [

12] and was later revisited in [

13]. Interestingly, the same result can be obtained from Lemma 3 by noticing that for all

, with

in (

26),

The converse of the Pythagorean theorem [

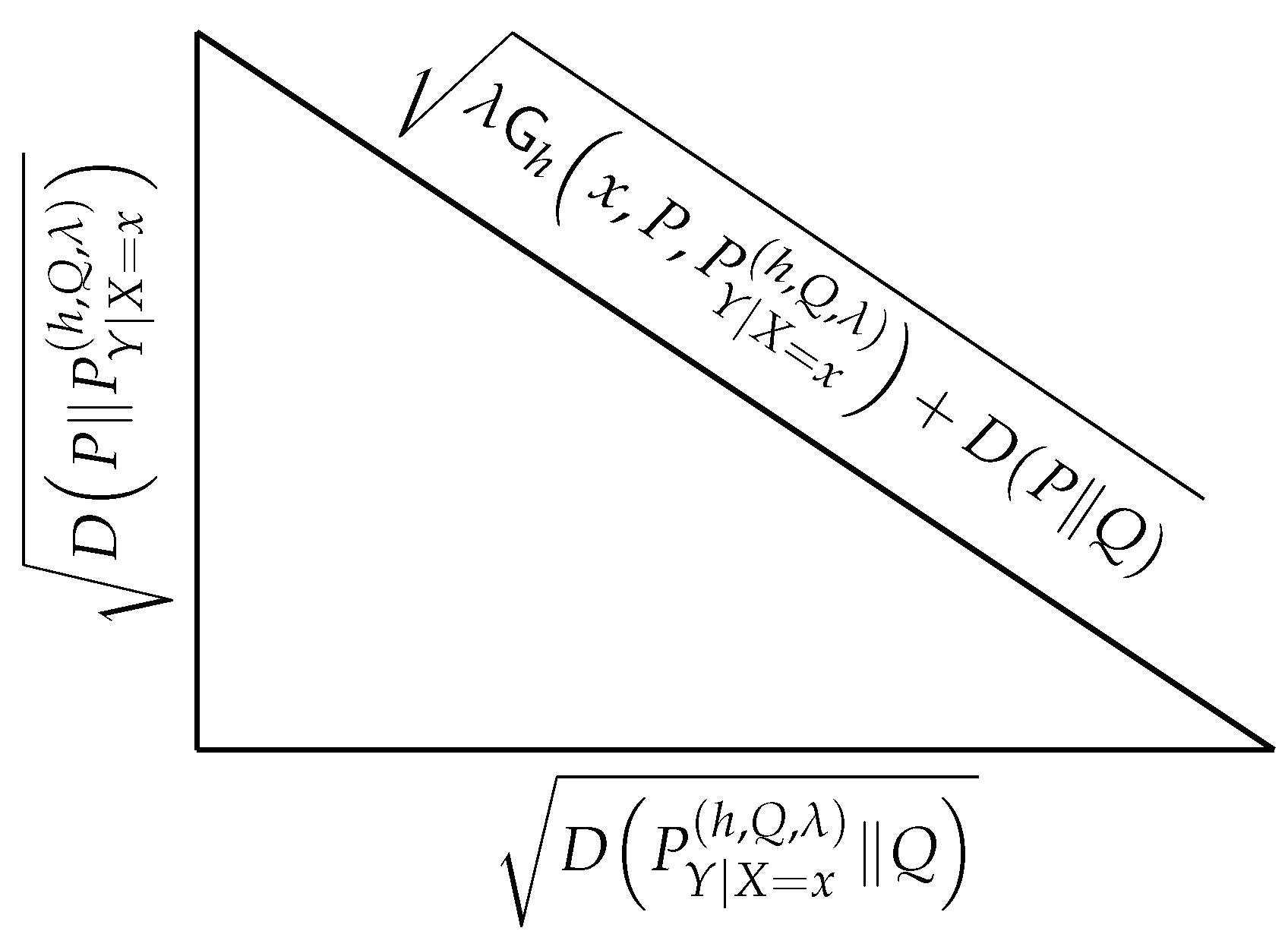

41] together with Lemma 3, lead to the geometric construction shown in

Figure 1. A similar interpretation was also presented in [

11] and [

11] in the context of the generalization error of machine learning algorithms. The former considers

, while the latter considers

. Nonetheless, the interpretation in

Figure 1 is general and independent of such an application.

The relevance of Lemma 3, with respect to this body of literature on information projections, follows from the fact that

Q might be a

-finite measure, which is a class of measures that includes the class of probability measures, and thus, unifies the results separately obtained in the realm of maximum entropy methods and information-projection methods. More importantly, when

, with

in (

26), it might hold that

or

, with

in (

18), which resonates with the fact that

-Gibbs conditional probability measures are also related to another class of optimization problems, as shown by the following lemma.

Lemma 4.

Assume that the following optimization problems possess at least one solution for some ,

Consider the -Gibbs probability measure in (10), with such that . Then, the -Gibbs probability measure is a solution to (4) if ; or to (4) if .

Proof:

Note that if

, then,

. Hence, from Lemma 3, it holds that for all probability mesures

P such that

,

with equality if

. This implies that

is a solution to (4). Note also that if

, from Lemma 3, it holds that for all probability mesures

P such that

,

with equality if

. This implies that

is a solution to (4). □

3. Characterization of in (1)

The main result of this section is the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

For all probability measures and , both absolutely continuous with respect to a given σ-finite measure Q on , the variation in (1) satisfies,

where the probability measure , with , is an -Gibbs probability measure.

Proof:

The proof follows from Lemma 3 and by observing that

□

Theorem 1 might be particularly simplified in the case in which the reference measure Q is a probability measure. Consider for instance the case in which (or ). In such a case, the reference measure might be chosen as (or ), as shown hereunder.

Corollary 1.

Consider the variation in (1). If the probability measure is absolutely continuous with respect to , then,

Alternatively, if the probability measure is absolutely continuous with respect to , then,

where the probability measures and are respectively - and -Gibbs probability measures, with .

In the case in which neither is absolutely continuous with respect to ; nor is absolutely continuous with respect to , the reference measure Q in Theorem 1 can always be chosen as a convex combination of and . That is, for all Borel sets , , with .

Theorem 1 can be specialized to the specific cases in which Q is the Lebesgue or the counting measure.

If Q is the Lebesgue measure the probability measures

and

in (

38) admit probability density functions

and

, respectively. Moreover, the terms

and

are Shannon’s differential entropies [

4] induced by

and

, denoted by

and

, respectively. That is, for all

,

The probability measure

, with

,

, and

Q the Lebesgue measure, possesses a probability density function, denoted by

, which satisfies

If Q is the counting measure the probability measures

and

in (

38) admit probability mass functions

and

, with

a countable subset of

. Moreover,

and

are respectively Shannon’s discrete entropies [

4] induced by

and

, denoted by

and

, respectively. That is, for all

,

The probability measure

, with

and

Q the counting measure, possesses a conditional probability mass function, denoted by

, which satisfies

These observations lead to the following corollary of Theorem 1.

Corollary 2.

Given two probability measures and , with probability density functions and respectively, the variation in (1) satisfies,

where the probability density function of the measure , with and Q the Lebesgue measure, is defined in (42); and the entropy functional is defined in (41). Alternatively, given two probability measures and , with probability mass functions and respectively, the variation in (1) satisfies,

where the probability mass function of the measure , with and Q the counting measure, is defined in (44); and the entropy functional is defined in (43).

5. Characterizations of in (6)

The main result of this section is a characterization of

in (

6), which describes the variation of the expectation of the function

h when the probability measure changes from the joint probability measure

to the product of its marginals

. This result is presented hereunder and involves the mutual information

and lautum information

, defined as follows:

Theorem 3. Consider the expected variation in (6) and assume that, for all :

The probability measures and are both absolutely continuous with respect to a given σ-finite measure Q; and

The probability measures and are mutually absolutely continuous.

where the probability measure , with , is an -Gibbs conditional probability measure.

An alternative expression for

in (

6) involving only relative entropies is presented by the following theorem.

Theorem 4.

Consider the expected variation in (6) and assume that, for all , the probability measure is absolutely continuous with respect to a given σ-finite measure Q. Then, it follows that

where , with , is an -Gibbs conditional probability measure.

Theorem 4 expresses the variation

in (

6) as the expectation (w.r.t.

) of a comparison of the conditional probability measure

with a Gibbs conditional probability measure

via relative entropy. More specifically, the expression consists in the expectation of the difference of two relative entropies. The former compares

with

, where

are independently sampled from the same probability measure

. The latter compares these two conditional measures conditioning on the same element of

. That is, it compares

with

.

An interesting observation from Theorem 3 and Theorem 4 is that the last two terms in the right-hand side of (

56) are both zero in the case in which

is an

-Gibbs conditional probability measure. Similarly, in such a case, the second term in the right-hand side of (

57) is also zero. This observation is highlighted by the following corollary.

Corollary 5.

Consider an -Gibbs conditional probability measure, denoted by , with ; and a probability measure . Let the measure be such that for all sets ,

Note that mutual information and lautum information are both nonnegative information measures, which from Corollary 5, implies that

in (

59) might be either positive or negative depending exclusively on the sign of the regularization factor

. The following corollary exploits such an observation to present a property of Gibbs conditional probability measures and their corresponding marginal probability measures.

Corollary 6.

Given a probability measure , the -Gibbs conditional probability measure in (10) and the probability measure in (58) satisfy

Corollary 6 highlights the fact that a deviation from the joint probability measure to the product of its marignals might increase or decrease the expectation of the function h depending on the sign of .

6. Final Remarks

A simple re-formulation of Varandan’s variational representation of relative entropy (Lemma 2) has been harnessed to provide an explicit expression of the variation of the expectation of a multi-dimensional real function when the probability measure changes from a Gibbs probability measure to an arbitrary measure (Lemma 3). This result reveals strong connections with information projection methods, Pythagorean identities involving relative entropy, and mean optimization problems constrained to a neighborhood around a reference measure, where the neighborhood is defined via an upper bound on relative entropy with respect to the reference measure (Lemma 4). An algebraic manipulation on Lemma 3 leads to an explicit expression for the variation of the expectation under study when the probability measure changes from an arbitrary measure to another arbitrary measure (Theorem 1). The astonishing simplicity in the proof, which is straight forward from Lemma 3, contrasts with the generality of the result. In particular, the only assumption is that both measures, before and after the variation, are absolutely continuous with a reference measure. The underlying observation is the central role played by Gibbs probability distributions in this analysis. In particular, such a variation is expressed in terms of comparisons, via relative entropy, of the initial and final probability measures with respect to the Gibbs probability measure specifically built for the function under study. Interestingly, the reference measure of such Gibbs probability measures can be freely chosen beyond probability measures. When such a reference is a -finite measure, e.g., Lebesgue measure or a counting measure, the expressions mentioned above include Shannon’s fundamental information measures, e.g., entropy and conditional entropy (Corollary 2).

Using these initial results, the variations of expectations of multi-dimensional functions due to variations of joint probability measures has been studied. In this case, the focus has been on two particular measure changes, which unveil connections with both mutual and lautum information. First, one of the marginal probability measures remains the same after the change (Theorem 2); and second, the joint probability measure changes to the product of its marginals (Theorem 3 and Theorem 4). In the case of Gibbs joint probability measures, these expressions involve exclusively well known information measures: mutual information; lautum information; and relative entropy. These expressions reveal general connections between the variation in the expectation of arbitrary functions, induced by changes in the underlying probability measure, and both mutual and lautum information. These connections extend beyond those previously established in the analysis of generalization error in machine learning algorithms; see, for instance, [

26] and [

8].