1. Introduction

Due to the special shape of curvature, a helical-coiled tube (HCT) can withstand the greater thermal expansion stress as the spring, as well as have the larger heat exchange area within the given volume and the higher heat transfer capability due to the stronger secondary flow caused by the centrifugal force. Then, the HCTs have been extensively applied in the industry components, especially for the heat exchanger. In the nuclear power plants (NPPs), the HCT heat exchanger (HCTHX) is designed in the Residual Heat Removal System (RHRS) and the Steam Generator (SG) for the Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). Most of previous works for the HCT heat exchanger (HCTHX) are focused on its overall heat transfer capability and performance. However, the localized information (like hot spot or inferior heat transfer point) is needed for the operational safety of NPPs. In this work, the CFD simulations have been performed to investigate the localized heat transfer characteristics of single-phase convection in a HCT, which can be considered as an assistance tool for the nuclear safety in the operation and maintenance.

Numerical works related to the single-phase convective heat transfer for a HCTHX had been reviewed. Ferng et al. [

1] developed a 3-D single-phase CFD model to investigate effects of Dean (De) number and pitch size on the thermal-hydraulic characteristics in a HCTHX. The average Nussel (Nu) number versus the tube length had been presented and compared with the measured data and appropriate correlations. Based on their simulation results, the overall phenomena in the HCTHX had be reasonably captured, which included the flow acceleration and separation in the shell side, the secondary flow within the tube, and the developing behaviors near the entrance of coiled tube, etc. Through the single-phase numerical simulations, Lin et al. [

2] investigated the effects of different turbulence models on the flow and heat transfer characteristics in a HCTHX. Three turbulence models were considered, including the realizable k–ε turbulence model (RKE), low-Reynolds k–ε turbulence model (LKE), and Reynolds stress model (RSM). They reported that the LKE turbulence model would over-predicted the heat exchanger performance as compared with the other two models and measured data. Alimoradi and Veysi [

3] numerically and experimentally studied the heat transfer of HCTHX under various parameters, including the physical properties of fluid, operational parameters, and geometrical parameters. Their results showed that the shell side Nu number increased with the increasing pitch and decreased with the increasing height and diameter of the shell. In addition, two correlations were developed to predict Nu numbers of coil side and shell side for wide ranges of Reynolds (Re) and Prandtl (Pr) numbers. In the work of Sepehr et al. [

4], the heat transfer, pressure drop and the entropy generation in shell and helically coiled finned tube heat exchanger was numerically studied. Effects of the fins height and number were considered. Their model was validated by comparing the overall Nu of both side and average friction factor of the coil side with the appropriate empirical correlations.

Elattara et al [

5] numerically investigated the thermal and hydraulic performance of the MTTHC (Multi-Tubes in Tube Helically Coiled) for the turbulent flow. Effects of the operating and geometrical parameters of the coil on the Nu number, pumping power, and effectiveness etc., were also considered. Their results showed the largest heat transfer coefficient and effectiveness were predicted at inner tube = 3 and coil inclination angle = 0° & 90°. Mirgolbabaei [

6] performed the thermal performance assessment of vertical HCTHX at various mass flow rates, coil-to-tube diameter ratio, and coil pitch. A conjugate thermal boundary condition for the tube wall fluid-to-fluid heat transfer mechanism, was considered. Based on the simulation results, the effectiveness of heat exchanger decreased with increasing coil pitch and had not been influenced by varying the tube diameter. Using single-phase CFD approach, Tuncer et al. [

7] compared the performance of modified shell and helically coiled heat exchanger (SHCHX) with a conventional one. This modified SHCHX was designed with a hollow tube integrated into the shell side with advantage of regulating the fluid flow in the shell side and improving the heat transfer. The corresponding modified SHCHX had been experimentally tested to determine its effectiveness. They reported that average difference between predicted and measured results was 8%.

Güngor et al. [

8] attached the rings and discs to the helical-coiled tubes to modify the conventional HCTHX. According to their simulation results, average heat transfer rate for the modified the heat transfer rate increased to 7.1 % as compared to the conventional one. In addition, the modified HX was fabricated and was experimentally tested with same conditions in laboratory to verify the simulation results. The comparison results revealed that the simulation results were close to the experimental data with difference of 2.4 % in terms of average heat transfer rate. Xu et al. [

9] performed the numerical simulations to study the effects of various grooving methods and depths on the overall heat transfer characteristics of HCTHXs. Their results implied that grooving on the plain tube could enhance the comprehensive heat transfer performance and simultaneously increase the pressure drop of the fluid. They concluded that the maximum performance evaluation criterion (PEC) was occurred for the helical-coiled spiral grooved tube (HCSGT) HXs with 0.5 mm groove depth. Yuan et al. [

10] numerically and experimentally study the performance of the double shell-passes multi-layer helical-coiled tubes heat exchanger (DSMHCTHX). Both results confirmed that the heat transfer rate and thermal effectiveness of DSMHCTHX increased by 5.1 % to 12.9 %, compared with the traditional multi-layer helical tube heat exchanger. However, the shell-side pressure drop increased by 60.7 % to 83.4 %.

Duan et al. [

11] developed a tube-shell coupled model for the helical-coiled corrugated tube heat exchanger. The effects of Re number, corrugation height, and corrugation length on flow and heat transfer performance were also considered. They concluded that the Nu number for both sides, and PEC significantly increased with the increasing corrugation height and the decreasing length. However, the corrugation height would enhance the friction factor, but its length had a little impact. Cao et al. [

12] numerically studied the heat transfer and flow resistance characteristics for the internally finned helical-coiled tubes heat exchanger. The corresponding tests were also performed. The empirical correlations to calculate the Nu number and friction factor of internally finned helicall-coiled tubes were summarized and validated using the measurements and predictions. They also reported that the internally finned helical-coiled tubes heat exchangers had better performance than smooth HCTHXs. Through CFD simulations, Missaoui [

13] investigated the influence of different helical coil structure designs on its heat transfer characteristics, including constant-diameter coil, variable-diameter coil and variable-pitch coil. This CFD model had been validated with the experimental measurements. They reported that the values of Nu number for the helical coil with variable pitch were higher than those of other configurations.

As the aforementioned literature review, most of CFD works related to the HCT or HCTHXs are focused on the overall heat transfer behavior and their performance. Seldom CFD simulations are conducted to study the localized heat transfer characteristics. However, the localized information just put the challenge to the safety of NPPs. Developing the single-phase CFD model based on the Best Practice Guidelines (BPGs) [

14], the preset simulation work can capture the localized heat transfer characteristics in a HCT. This CFD methodology has been validated with the test data of the non-uniform circumferential distributions of wall temperature and heat transfer coefficient [

15]. Combined with the experimental results, the present model can assess the applicability of correlations suitable for the heat transfer in a HCT tube. In addition, the simulation results from this CFD model can help explain the measured results using the predicted thermal-hydraulic contours on the cross-section of HCT, which can also assist in analyzing the design and operation safety of HCTHXs for the NPPs.

3. Results and Discussion

The experimental work [

15] for measuring the non-uniform circumferential distributions of wall temperature and heat transfer coefficient for a HCT is adopted to assess the present CFD methodology.

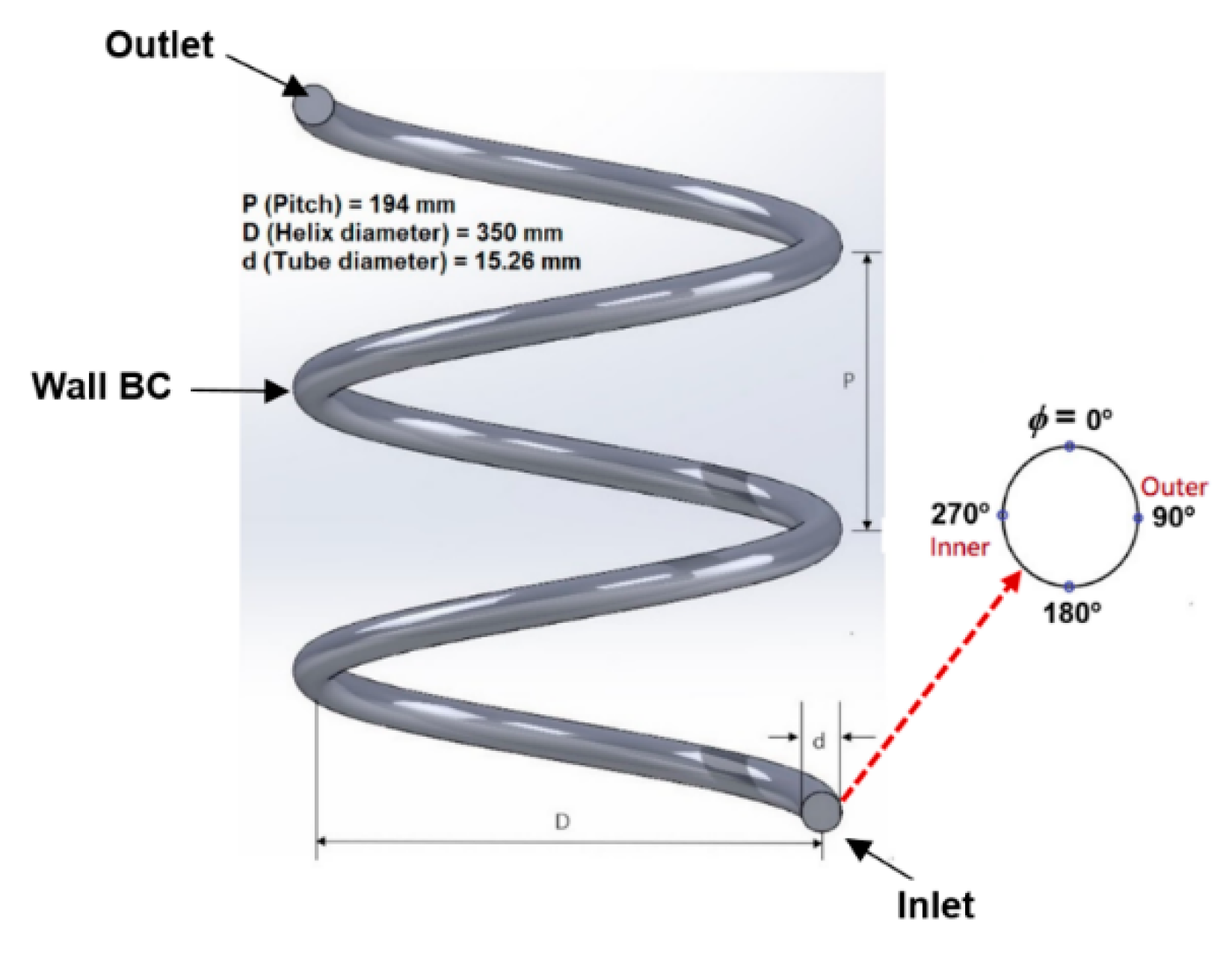

Figure 1 shows the schematics of HCT for the present simulations. The right portion of this figure represents the circumferential angle (

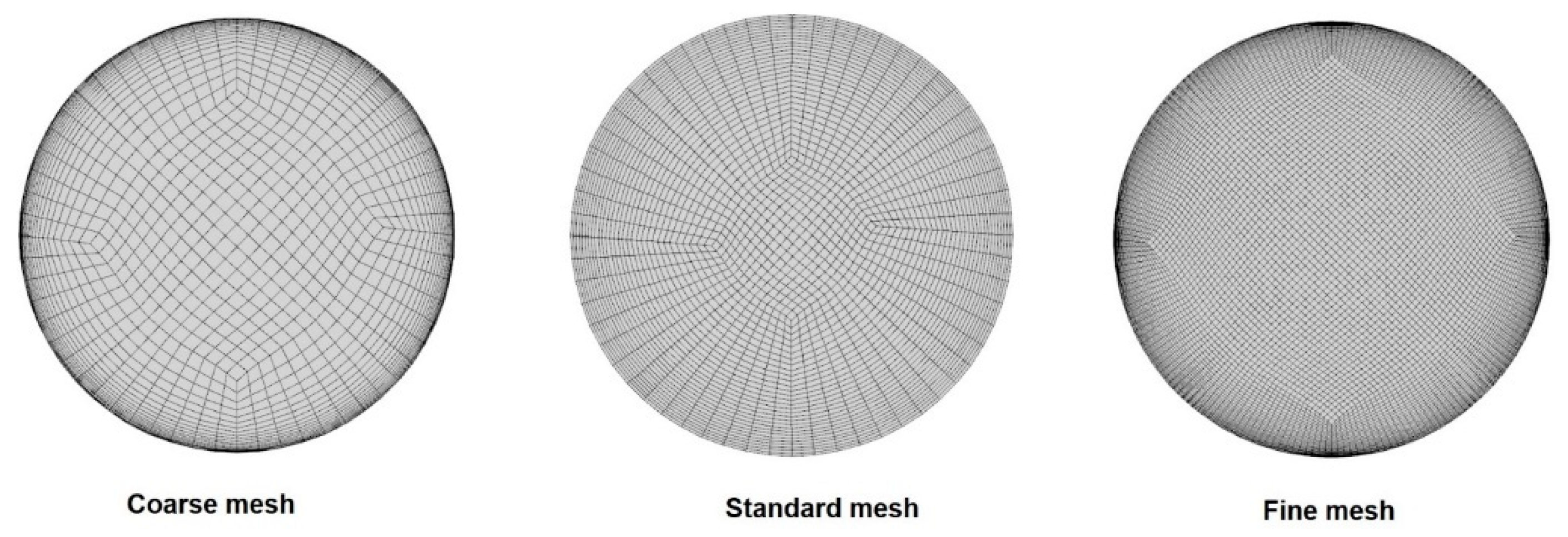

φ) on the HCT wall. The corresponding mesh distributions on the cross-section of HCT are indicated in

Figure 2. Based on the requirements of the CFD Best Practice Guidelines [

14], the structured grids should be adopted near the wall and mesh independent calculations should be performed. The sensitivity simulations for the various mesh are applied on the cross-section of HCT, including 860 (Coarse), 1,425 (Standard), and 3525 (Fine) cells, respectively. The corresponding values of y+ for these three mesh models are 28.9~36.2 (Coarse), 0.8~1.2 (Standard), and 0.6~1.1 (Fine). Uniform girds are adopted along the HCT with the interval of 10

o helical coil. The constant heat flux is set at the tube wall; the inlet mass flux and temperature are set at the tube inlet; the pressure is set at the tube outlet. The simulation conditions for all the case are listed in

Table 2.

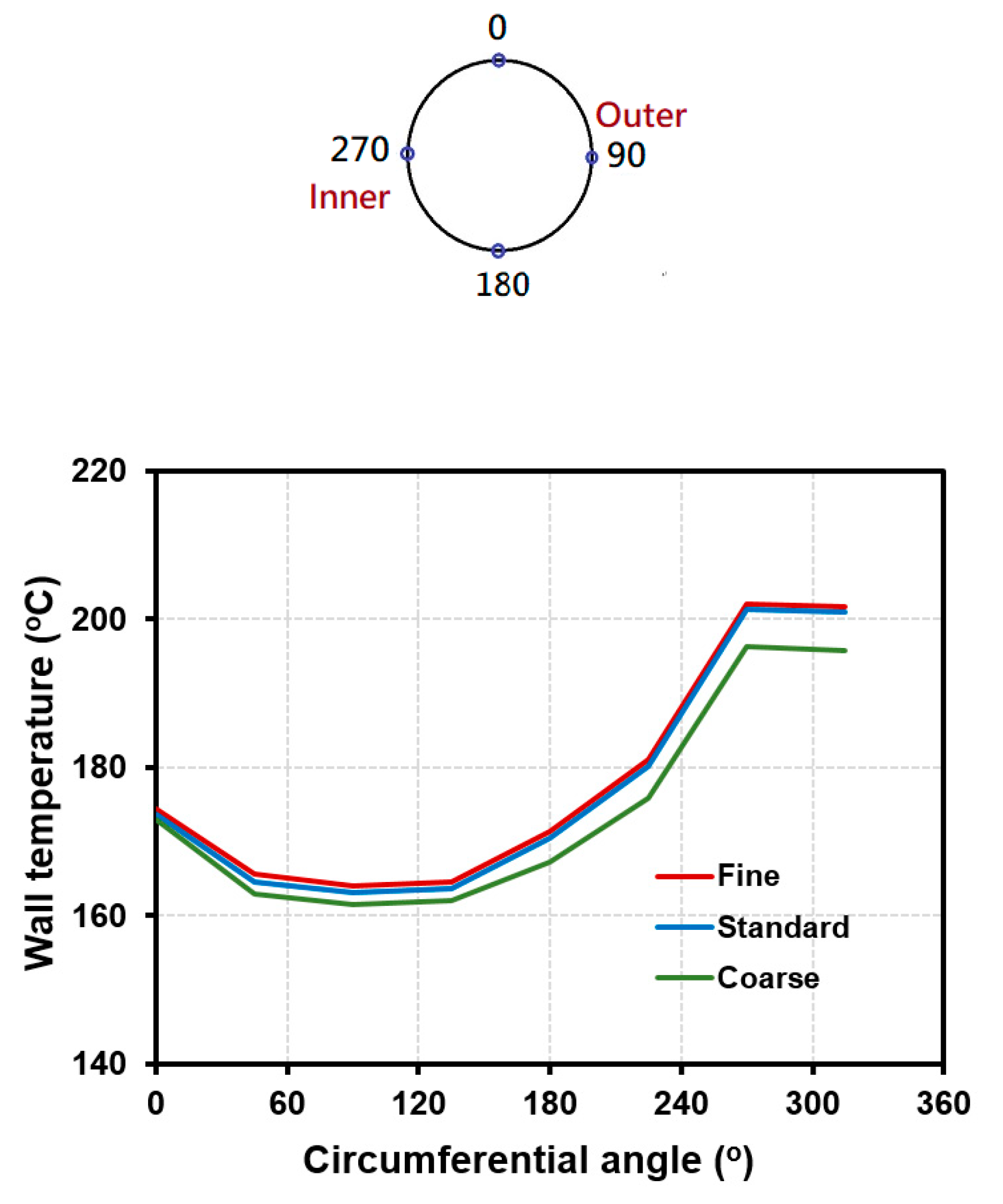

Figure 3 compares the predicted results for the circumferential distributions of wall temperature at x = -0.147 under the coarse, standard, and fine mesh. The conditions of Case 1 in

Table 2 and the SSTKW turbulence model are adopted. In this figure, the abscissa represents the circumferential angle (

φ) of HCT. Similar to the location index using the quality (x) in the measured data presentation of Wang et al., [

15], x is also adopted as the location index of HCT. As illustrated in the upper portion of

Figure 3,

φ = 90

o and 270

o are the tube wall on the outer and inner sides, respectively, of HCT. This figure implies that the predicted result of circumferential temperature distribution using the standard mesh is close to that from the fine mesh.

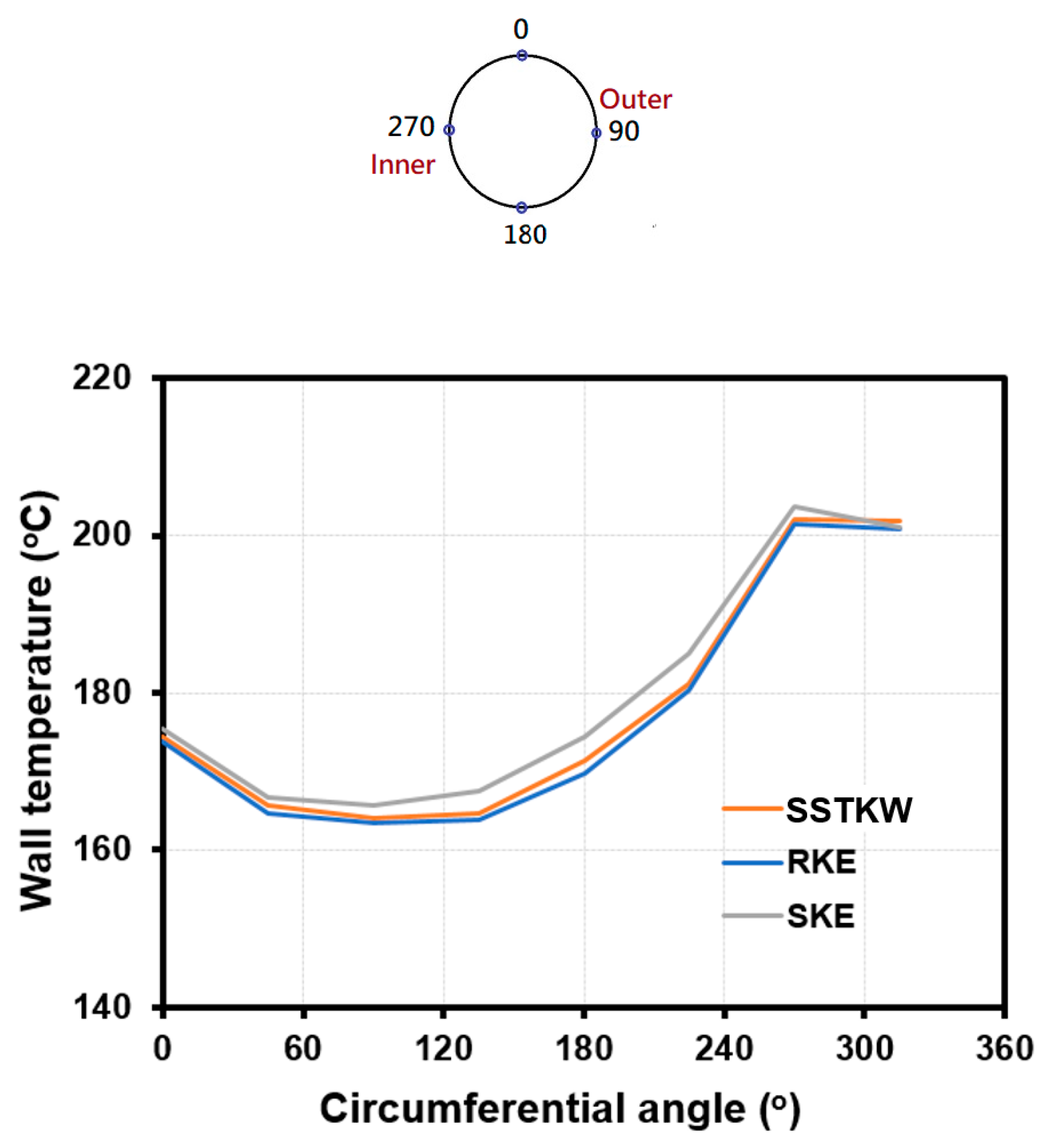

Since the BPGs provides useful guidelines for the single-phase applications of CFD to nuclear reactor safety (NRS) problems [

14], these guidelines should be followed to ensure accuracy and credibility of CFD predictions. The essential requirements for the BPGs are applied in the mesh model, the physical models, especially the turbulence model, and the model validation. Therefore, in addition to the mesh model, the sensitivity calculations of turbulence models are also conducted, including the SKE, RKE, and SSTKW. The blind calculations using different turbulence models are clearly revealed in

Figure 4 and the simulation conditions are the same as those in

Figure 3. As shown in this figure, the predicted results of circumferential wall-temperature distribution at x = -0.147 using both the SSTKW and the RKE are similar. Both the SSTKW and RKE turbulence models provide superior performance for flow characteristics with adverse pressure gradient, recirculation, and separation, which are similar to the flow characteristics in a HCT. The SSTKW is less sensitive to the inlet turbulence properties and less restriction for the near-wall mesh model. Therefore, the SSTKW turbulence model and the standard mesh are adopted to be assessed in the followings (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) with the experimental data and then applied in the extended discussion in the thermal-hydraulic characteristics in a HCT with confidence.

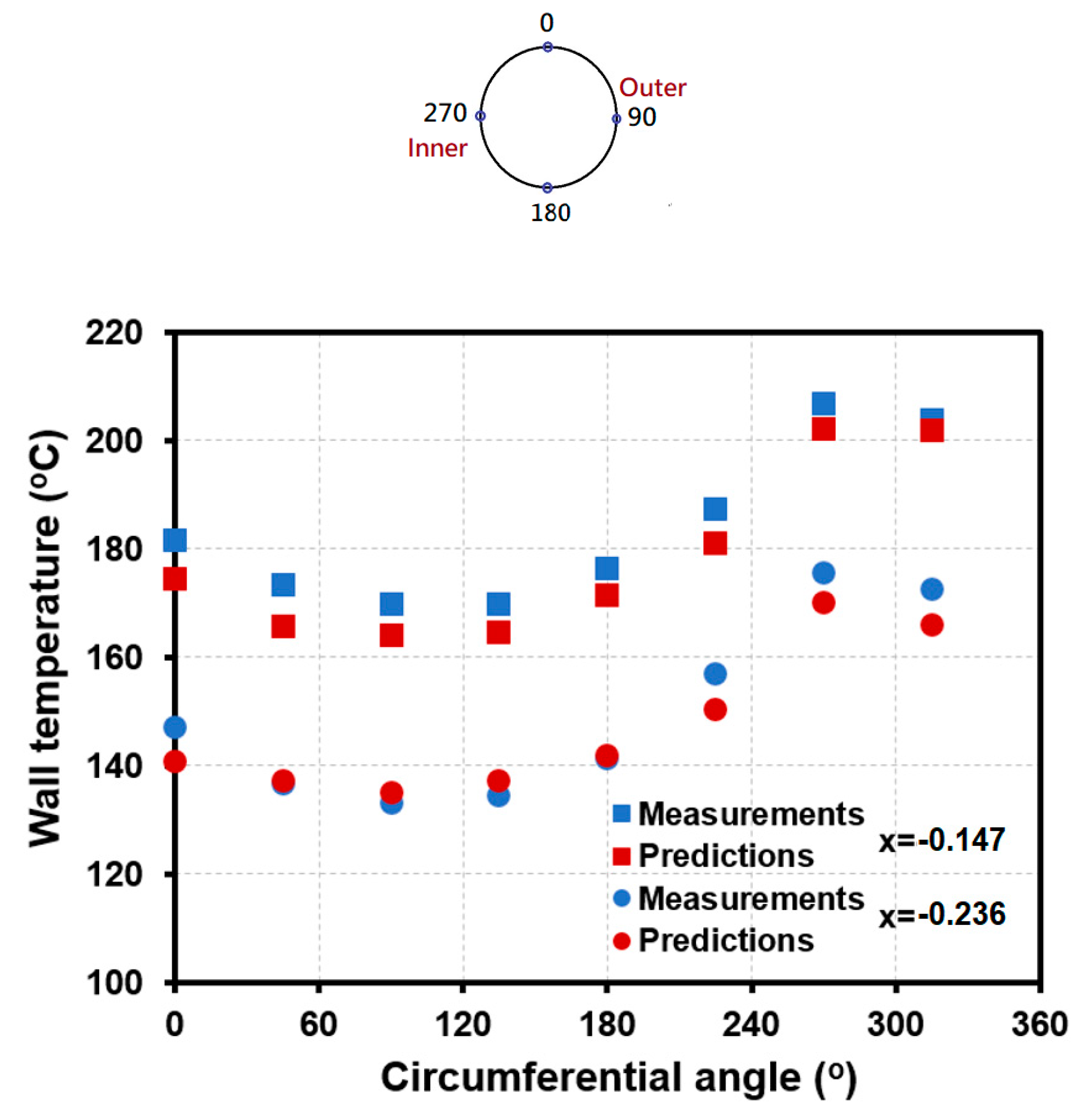

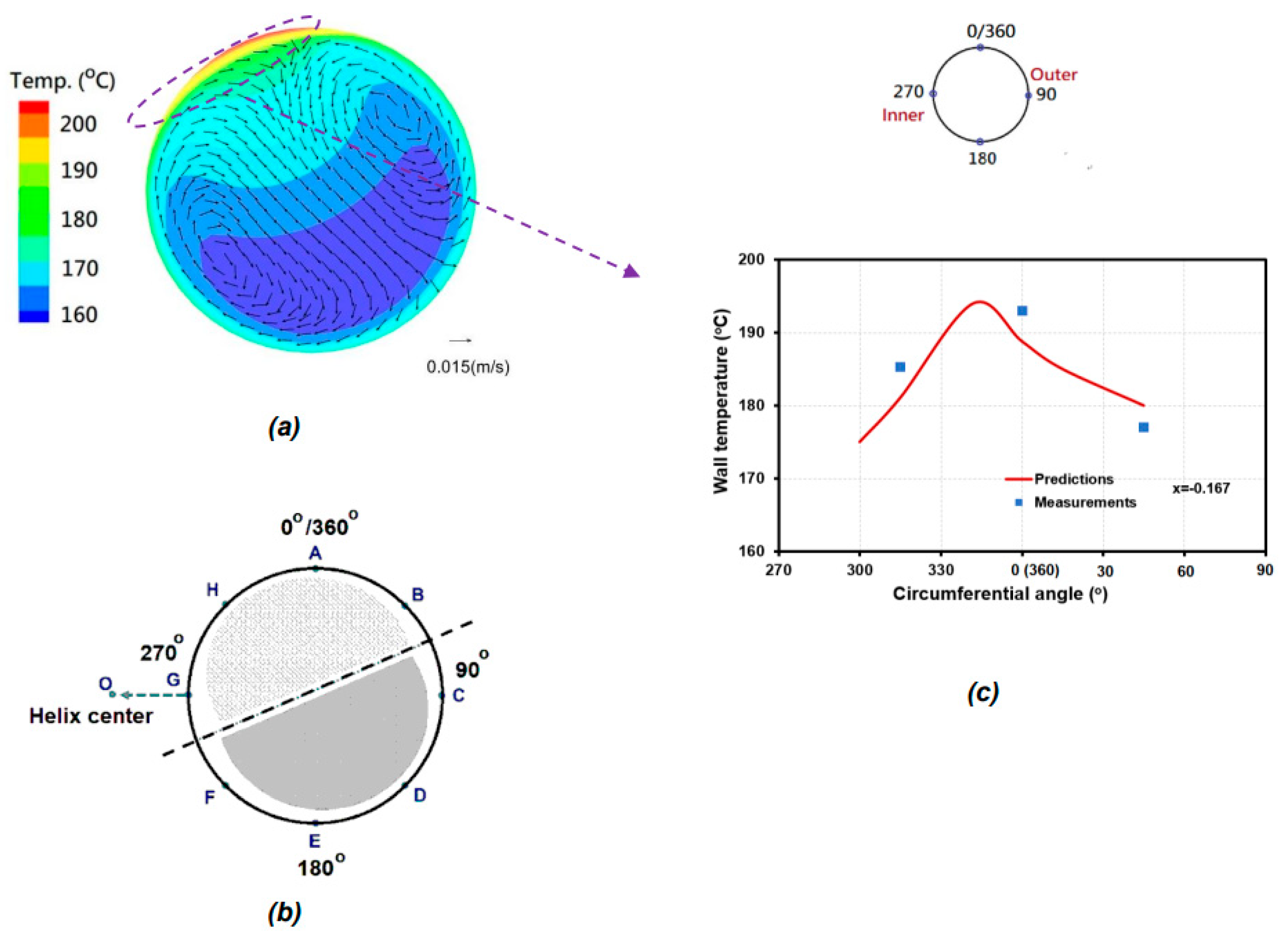

Figure 5 compares the circumferential distributions of wall temperature at x = -0.147 (

L = 2.07 m) and -0.236 (

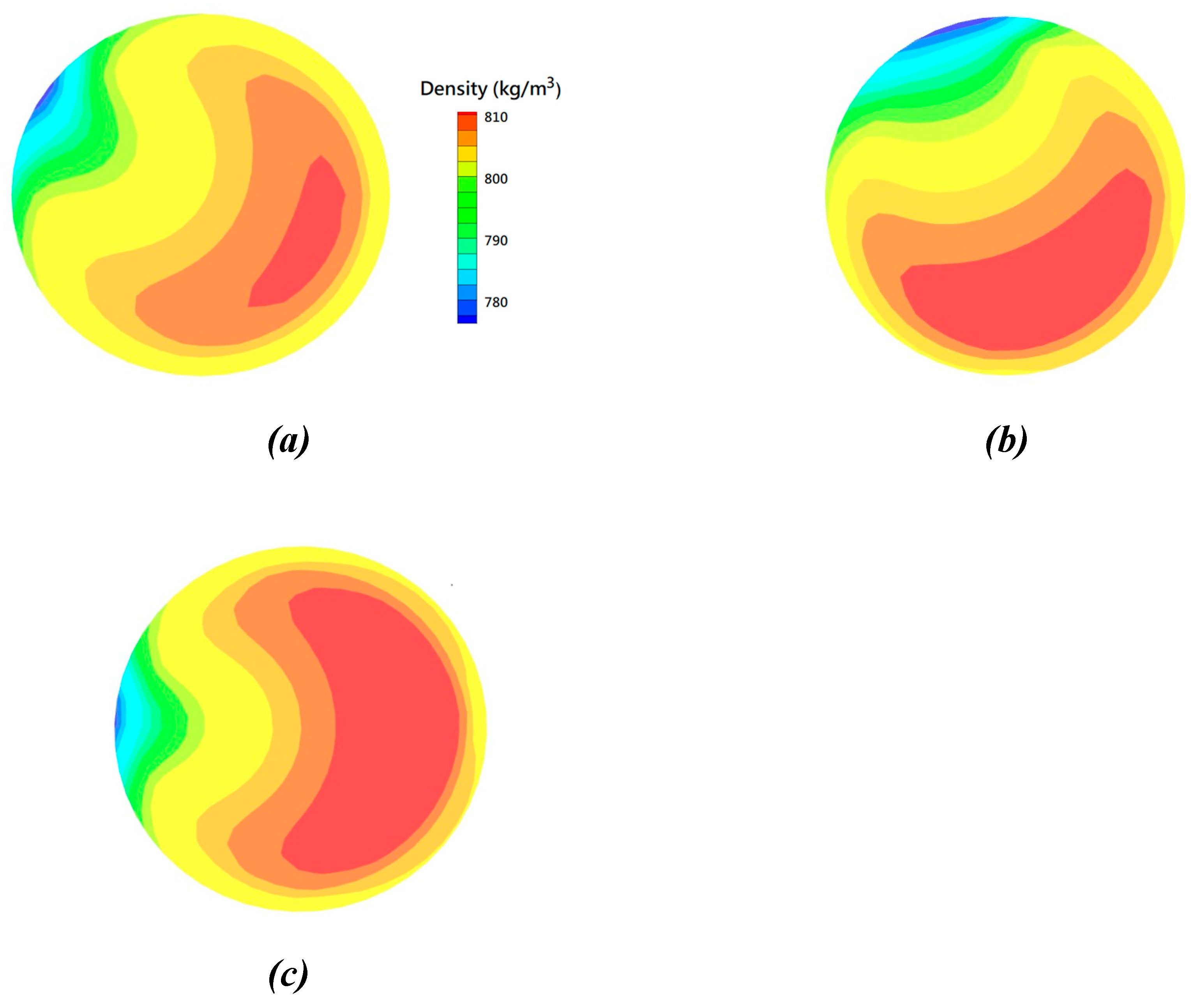

L = 0.57 m), respectively, predicted by the present CFD model (red dots) with those from the measurements (blue dots) for Case 1. It can be clearly seen in this figure that the predicted distributions agree well with the measured ones at these two locations. Both the measured and predicted results also show the strong non-uniform circumferential distribution of wall temperature for the HCT. As the aforementioned descriptions, the thermal-hydraulic characteristics in a HCT are governed by the centrifugal force and the gravitational force. The lower-temperature water with the higher density would be push to the outer portion of HCT due to the centrifugal force and tends to accumulate on the lower portion of tube due to the gravitational force. As shown in

Figure 6 (a), the higher-density water is located near the outer and right-bottom portion of HCT (

φ ~ 135

o). In addition, the lower density water with the higher-temperature water can be found near

φ = 315

o. These predicted density distributions can provide the obvious images to explain the inhomogeneity distribution of circumferential wall temperature, which cannot be revealed in the measured results.

As the mass flux in the HCT decreases (i.e. Case 2), the thermal-hydraulic characteristics are governed by the gravitational force more than the centrifugal force. The lower-temperature water with the higher density is accumulated in the lower portion of HCT than that for the Case 1. This difference can be found in the density contours for both cases, as clearly revealed in the comparison of Figures 6 (a) and (b).

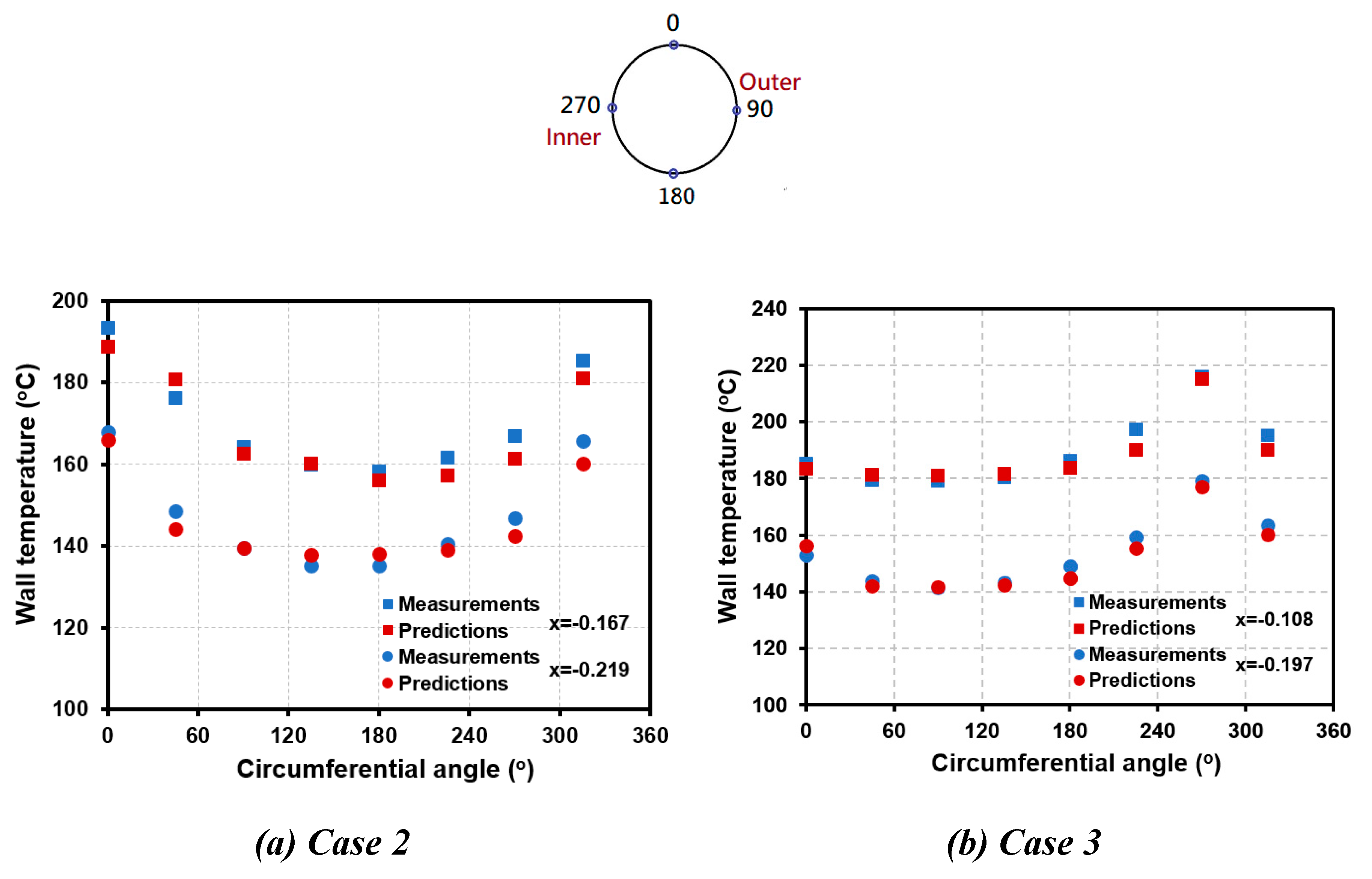

Figure 7 (a) shows the circumferential distributions of wall temperature at x = -0.167 (

L = 1.49 m) and -0.219 (

L = 0.74 m), respectively, obtained from the CFD simulations (red dots) and the test data (blue dots) for Case 2. As revealed in this figure, the lower wall temperature is located near

φ = 180

o and the higher wall temperature appears near

φ = 360

o. Both the measured and predicted results show this trend. In contrast to the Case 2 with the lower mass flux, the inlet mass flux increases enough (i.e. Case 3) so that the gravitational effect can be neglected as shown in

Figure 7 (b) that is the circumferential distributions of wall temperature at x = -0.108 (

L = 4.76 m) and -0.197 (

L=2.15 m), respectively, for Case 3. Therefore, The peak wall temperature then is predicted to occur at

φ = 270

o. The thermal-hydraulic characteristics for Case 3 are symmetric along the horizontal line on the cross-section for a vertical HCT, as clearly shown in the density contour of

Figure 6 (c). In addition, the predicted values for the circumferential distributions of wall temperature also correspond well with the measured ones, as clearly seen in both plots of

Figure 7.

The Lu number represents the ratio of centrifugal force and buoyancy and can be written as

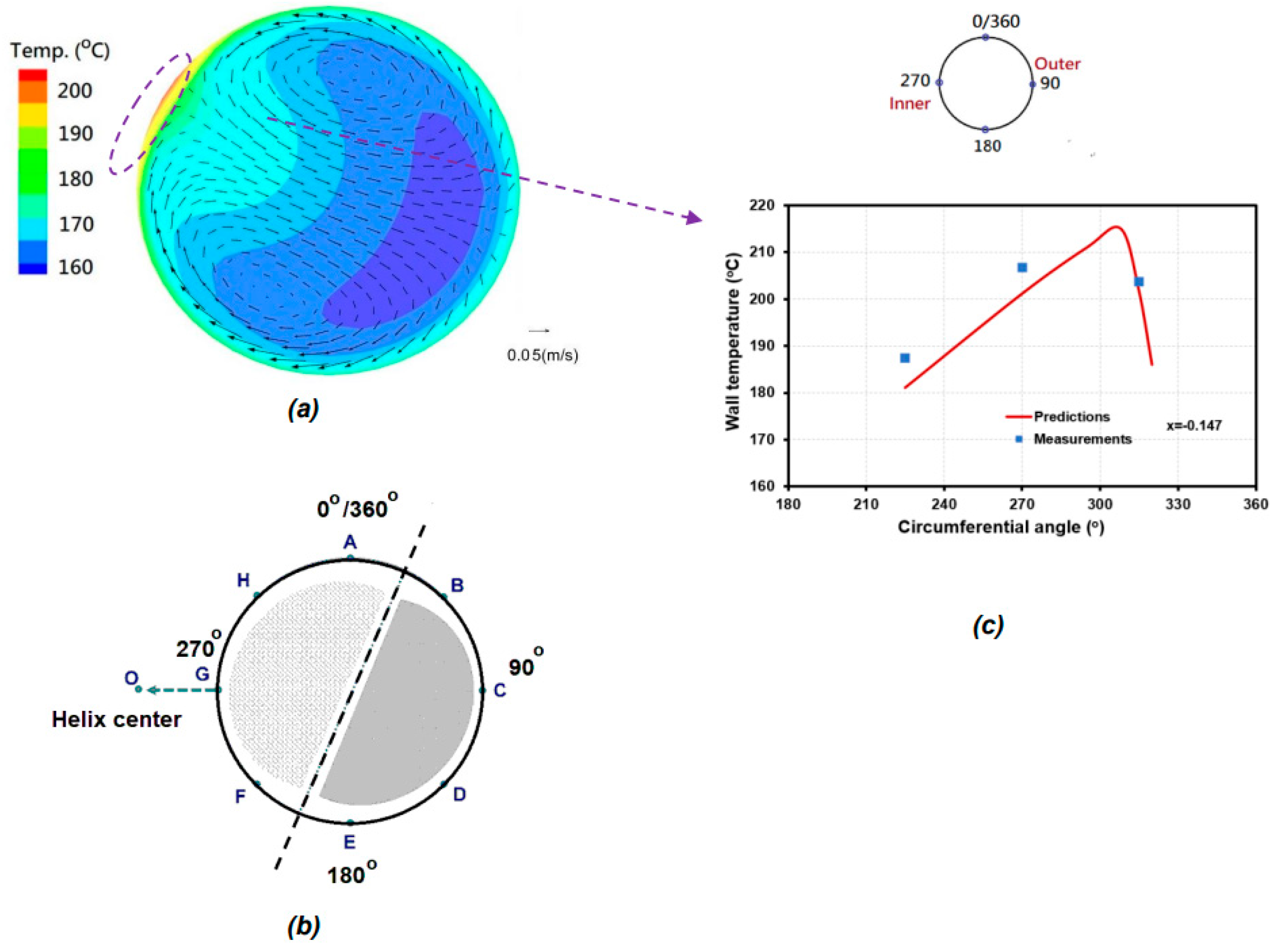

This non-dimensional number can characterize the flow and heat transfer patterns for the HCT. The Lu number increases with the increasing mass flux in a HCT, which also enhances the influence of centrifugal force, and vice versa. Therefore, three simulation cases with the Lu number of 1.226, 0.12, and 13.7 are selected in the present work, which characterizes the middle (centrifugal force balanced by buoyancy force), low (buoyancy force dominated), and high (centrifugal force dominated) Lu number, respectively. Figures 8 (a) and 9 (a) show the distribution patterns of temperature on the cross-section of HCT for Case 1 and Case 2. Combined observation of density and temperature contours in

Figure 6 (a) and

Figure 8 (a) reveals that the higher heat transfer region with the lower-density and higher-temperature water is located near the upper left corner and the lower heat transfer one with the higher-density and lower-temperature water is near the lower-right corner. These predicted results can provided the clear images of two-region flow and heat transfer characteristics. This two-region heat transfer pattern is also confirmed in the experimental work of Wang et al. [

15]. They suggested the schematic of two-region heat transfer patterns with the higher heat transfer region in the upper-left corner and the lower heat transfer one in the lower-right corner, as indicated in

Figure 8 (b). The predicted heat transfer flow pattern from the present CFD results and the schematic one from the work [

15] for Case 2 are also revealed in Figures 9 (a) and (b) , respectively.

The vector distributions of secondary flow on the cross-section of HCT are also plotted on Figures 8 (a) and 9 (a). As clearly shown in these plots, a vortex-pair of secondary flow is shown on these cross-sections of HCT and the higher wall temperature occurs where the secondary flow leaves away. In addition,

Figure 8 (a) indicates that the higher wall temperature may appear between

φ =270

o and 315

o. However, the circumferential distribution of measured temperatures is presented in the discrete pattern on the selected locations only. Based on the measured data of Case 1, the peak wall temperature at x = -0.147 occurs at

φ = 270

o. However, as shown in

Figure 8 (c), the peak wall temperature is located at

φ ~ 308

o. The exact location of peak wall temperature can be captured only in the CFD results and cannot be revealed in the experimental data, which is one of the main contributions for the CFD simulations. Similar result for Case 2 is also shown in

Figure 9 (c). The peak wall temperature at x = -0.167 is measured at

φ = 0

o (i.e. 360

o), while the peak wall temperature may be actually at

φ ~ 342

o, based on the predicted result. Therefore, in addition to matching the measured data, the calculated results from the present CFD model then can help interpret the test results and expand their application.

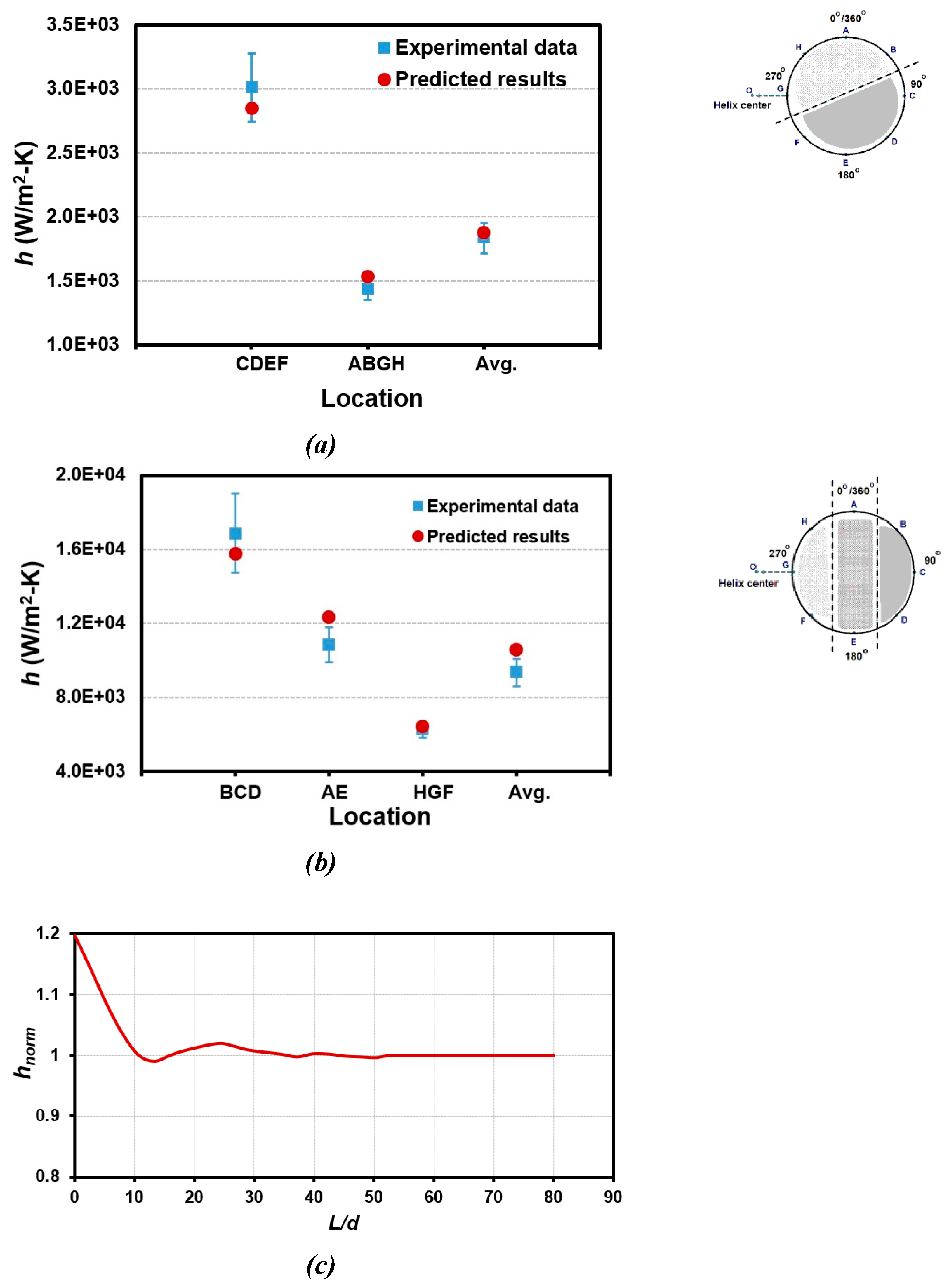

Figure 10 compares the circumferentially averaged heat transfer coefficients in different regions, which are obtained from the measurements and the predictions for Case 2 and Case 3, respectively. As shown in

Figure 10 (a) of Case 2 with Lu < 0.25, two regions with the different averaged heat transfer along the HCT circumferential wall is suggested from the work [

15], including

φ = 270

o - 45

o (i.e regions A, B, G, H) and 90

o -225

o (i.e. regions C, D, E, F). The definition of A-H regions is illustrated in the right portion of this plot. The former region (i.e regions A, B, G, H) is the lower heat transfer region where the higher temperature water with the lower density occurs and the latter region is the higher heat transfer one. It can be clearly revealed in

Figure 10 (a) that the circumferentially averaged heat transfer coefficients over the regions A, B, G, H, the regions C, D, E, F, and the overall circumferential wall (i.e. defined Avg. in the

Figure 10 (a)) predicted by the present CFD model correspond well with those from the experiment. The non-uniform distribution for the wall heat transfer coefficients can be also shown in both the measurements and predictions.

The quantity correspondence between the measured and predicted heat transfer coefficient at the different regions as well as its average value is also shown in

Figure 10 (b) for Case 3. Three regions with different heat transfer characteristics are only suggested based on the measured data, but these characteristics have been clearly seen in the present predicted results in the density contour of

Figure 6 (c). In addition, the predicted heat transfer coefficients shown in plots (a) and (b) of

Figure 10 are the fully-developed one. The heat transfer coefficient would decrease from the inlet of HCT and approaches to the fully-developed value, as clearly revealed in

Figure 10 (c) for Case 3. In this plot, the longitudinal axis is the normalized heat transfer coefficient (

hnorm) that is the local

h divided by the fully-developed one. The abscissa axis is the distance from the inlet of HCT. Detailed observation of this plot implies that the entrance length (developing length) is about 42 ~ 50 pipe diameter (

d). The correlation for the entrance length for a HCT has been proposed by Saffari et al. [

19]) and is expressed as the function of Reynolds number (Re), Dean number (

De), and curvature ration (

δ).

Using the conditions of Case 3, the entrance length calculated using this correlation is 51.24 that is close to the present predicted range.

In addition, the thermal-hydraulic characteristic would reach the fully-developed condition as the flow passes over the coil angle (

ψ) of 210

o ~ 275

o based on the coil/tube diameter values, implying that the entrance effect may be neglected for evaluating the overall heat transfer characteristics for a whole HCT or HCTHX. Then, the fully-developed correlations of heat transfer coefficient can be applied to estimate the heat transfer capability for a HCT or HCTHX.

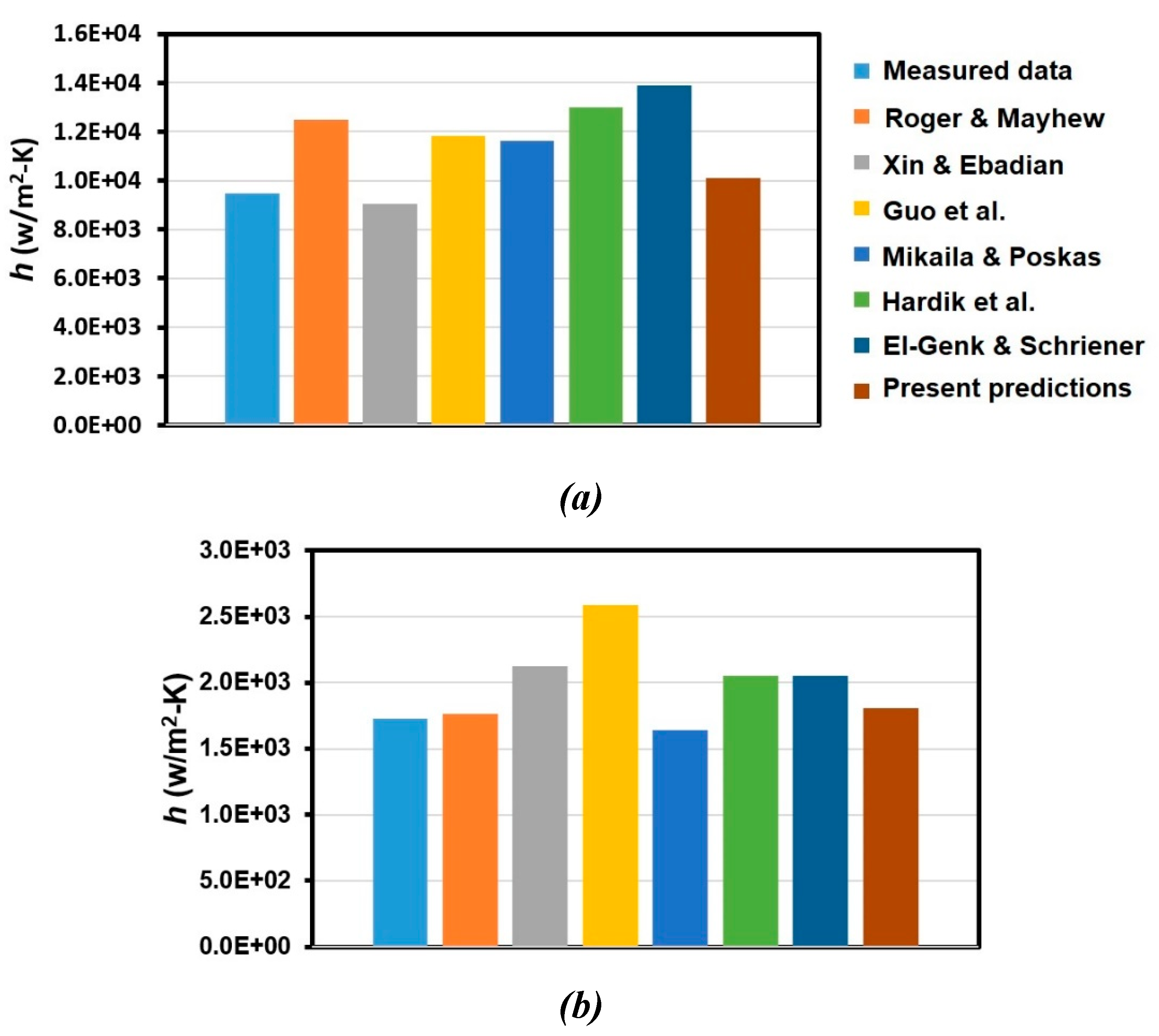

Figure 11 compares the fully-developed heat transfer coefficient for a HCT obtained from the present CFD model, the appropriate correlations, and experiment for Case 2 (a) and Case 3 (b). These correlations include those proposed by Rogers and Mayhew [

20], Mikaila & Poskas [

21], Xin & Ebadian [

22], Guo et al. [

23], Hardik et al. [

24], and El-Genk & Schriener [

25] since Gou et al. [

23] had suggested that these correlations are suitable for predicting the heat transfer coefficient for a HCT. Similar to the comparison in

Figure 10, the agreement between the predicted

h and the measured one is also shown in this figure under different flow conditions. In addition, the calculated

h from the Xin & Ebadian’s correlation [

22] matches with the data better than that from others for Case 2 and the

h calculated using the correlation of Rogers & Mayhew [

20] or Mikaila & Poskas [

21] shows more agreement with the data for Case 3. Therefore, these comparison results strong imply that applicability of various kinds of

h-correlation for the HCTs depends on their flow conditions, which reveals that the contribution of CFD simulation in this area.

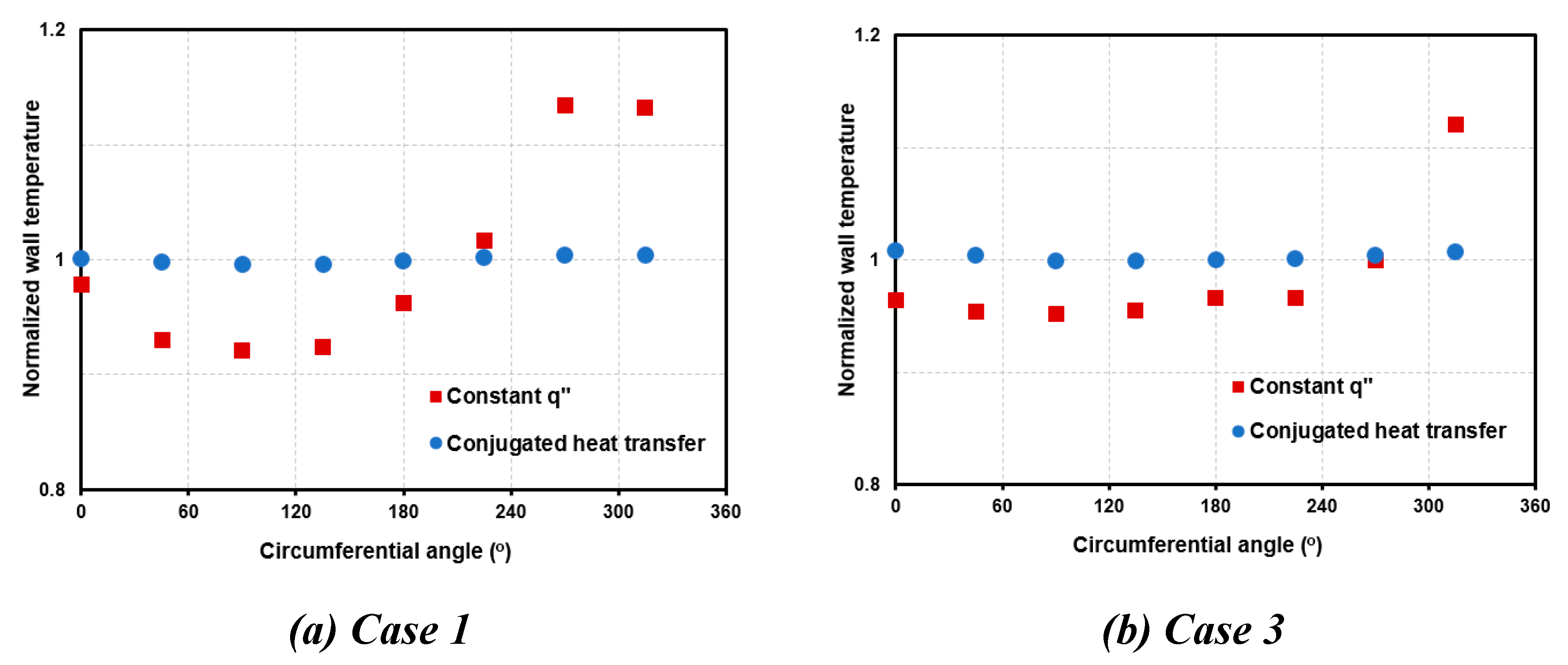

The inhomogeneity of circumferential distributions for single-phase heat transfer characteristics for a vertically helical-coiled tube are clearly shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, which is essentially caused by the constant-heat-flux boundary condition. This boundary condition for CFD simulations is not suitable to investigate the flow and heat transfer behaviors within the HCTHX, as described in the work of Bahrehmand and Abbassi [

26]. The higher wall temperature occurs near the region with inferior heat transfer under the condition of constant

. However, the heat transfer mechanism for a HCT heat exchange is mainly belong to the conjugated heat transfer from the hot fluid in the shell side to the cold fluid in the tube side. The wall heat flux would decrease around the location with the poor heat transfer capability within the tube side, suppressing this higher-wall-temperature phenomenon. Therefore, the conjugated heat transfer effect by including the shell-side solution domain is simulated herein in order to investigate the effect of conjugated heat transfer on the non-uniform characteristics of HCT wall in the HCTHX.

Figure 12 compares the circumferential dependence of normalized temperature predicted using the constant-heat flux BC and the conjugated heat transfer simulation, respectively. The normalized temperature shown on the longitudinal axis is the local wall temperature divided by the average wall temperature. The simulation conditions under the constant-heat-flux cases in Figures 12 (a) and (b) are similar to those for Cases 1 and 3. The inlet mass flux/temperature and pressure of tube side for the conjugated-heat-transfer cases are the same as those for the constant-heat-flux ones. For the conjugated-heat-transfer cases, the mass flowrate in the shell side is set to be 0.2 kg/s. The temperature drops for the shell side in Figures 12 (a) and (b) are set to be 35.6 and 58.1

oC, respectively, so that the heat transfer rate from the shell side to the tube is similar to that set in the constant-heat-flux cases. It can be clearly shown in

Figure 12 that the non-uniform circumferential distribution of heat transfer is essentially caused by the constant-heat-flux boundary condition on the HCT wall. This characteristic can be significantly reduced by actually considering the heat transfer from the shell side.