Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

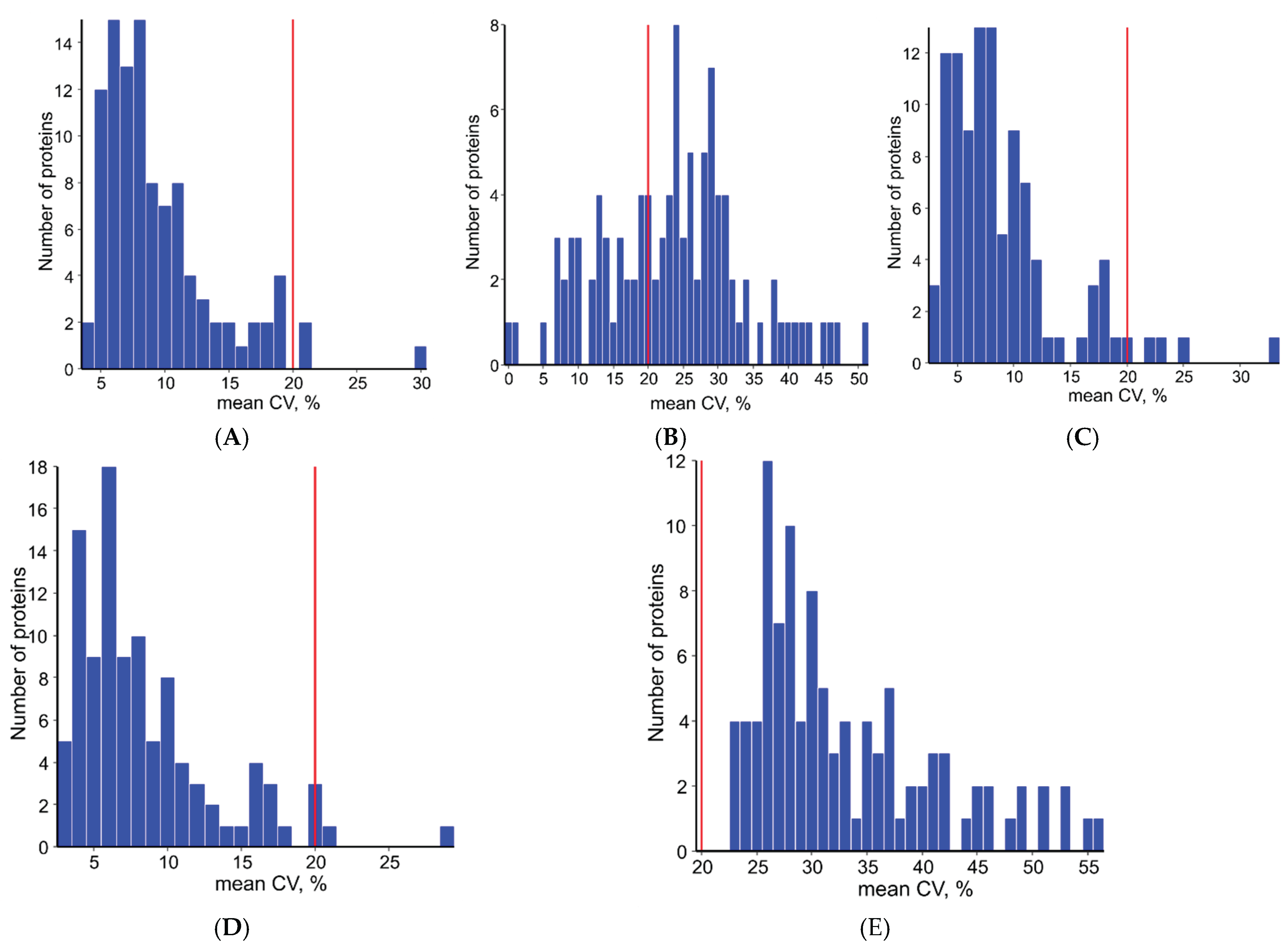

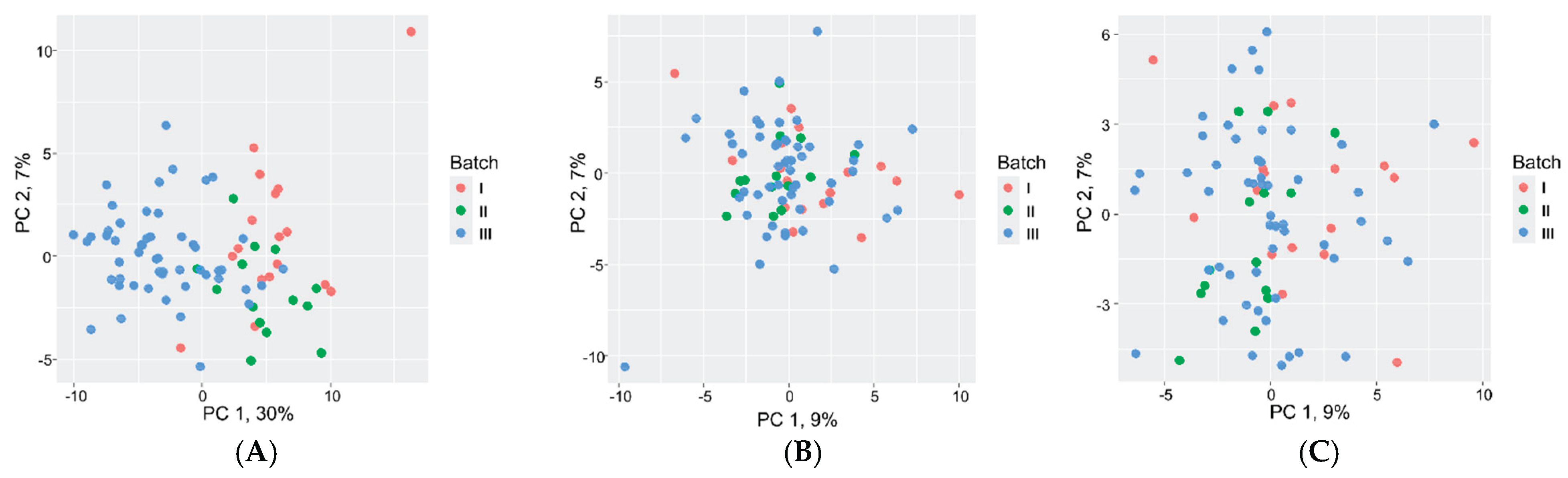

2.2. Data Normalization

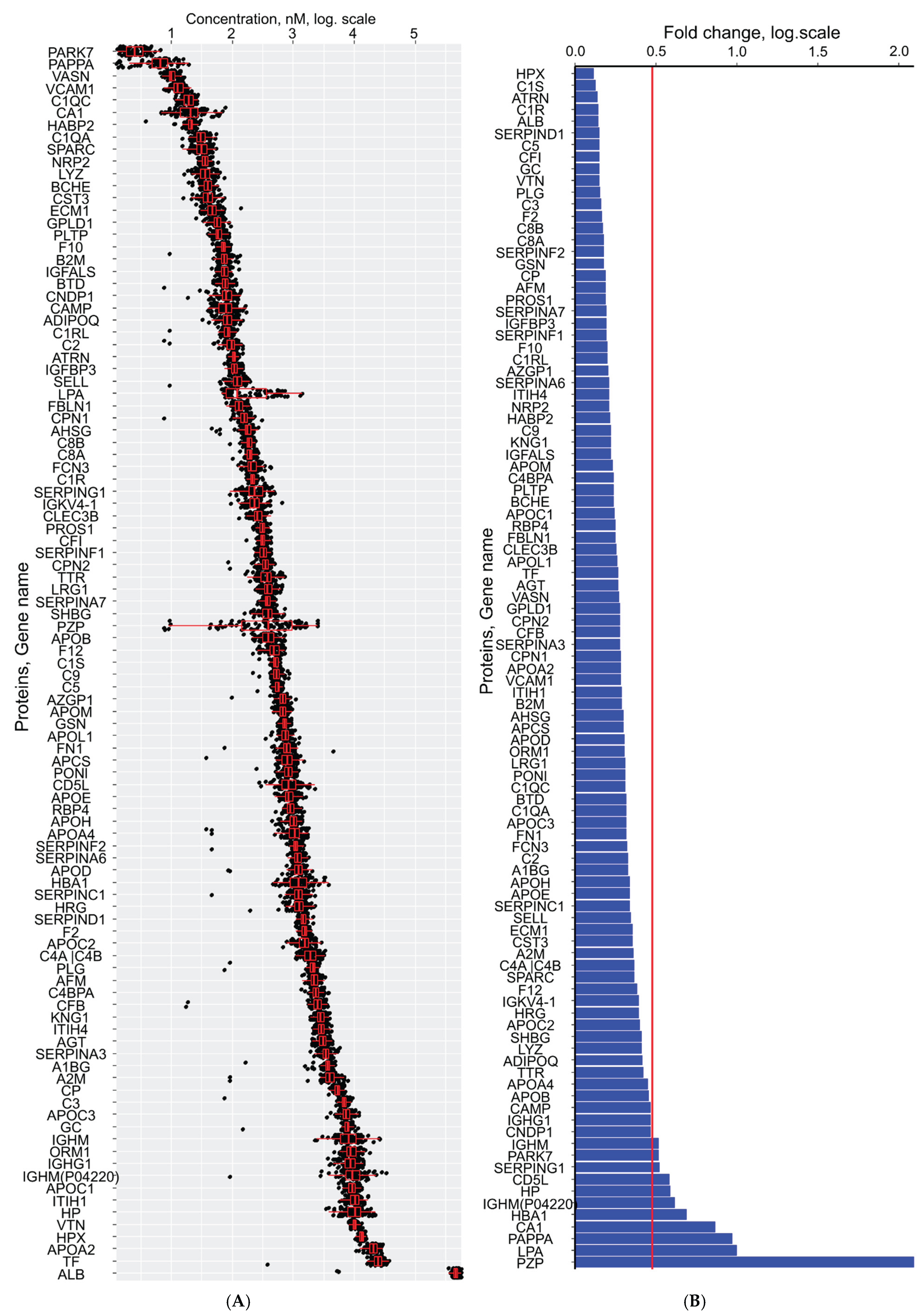

2.3. First Trimester Serum Proteome Profiling

2.4. Associations Between Serum Proteome and Clinical Parameters

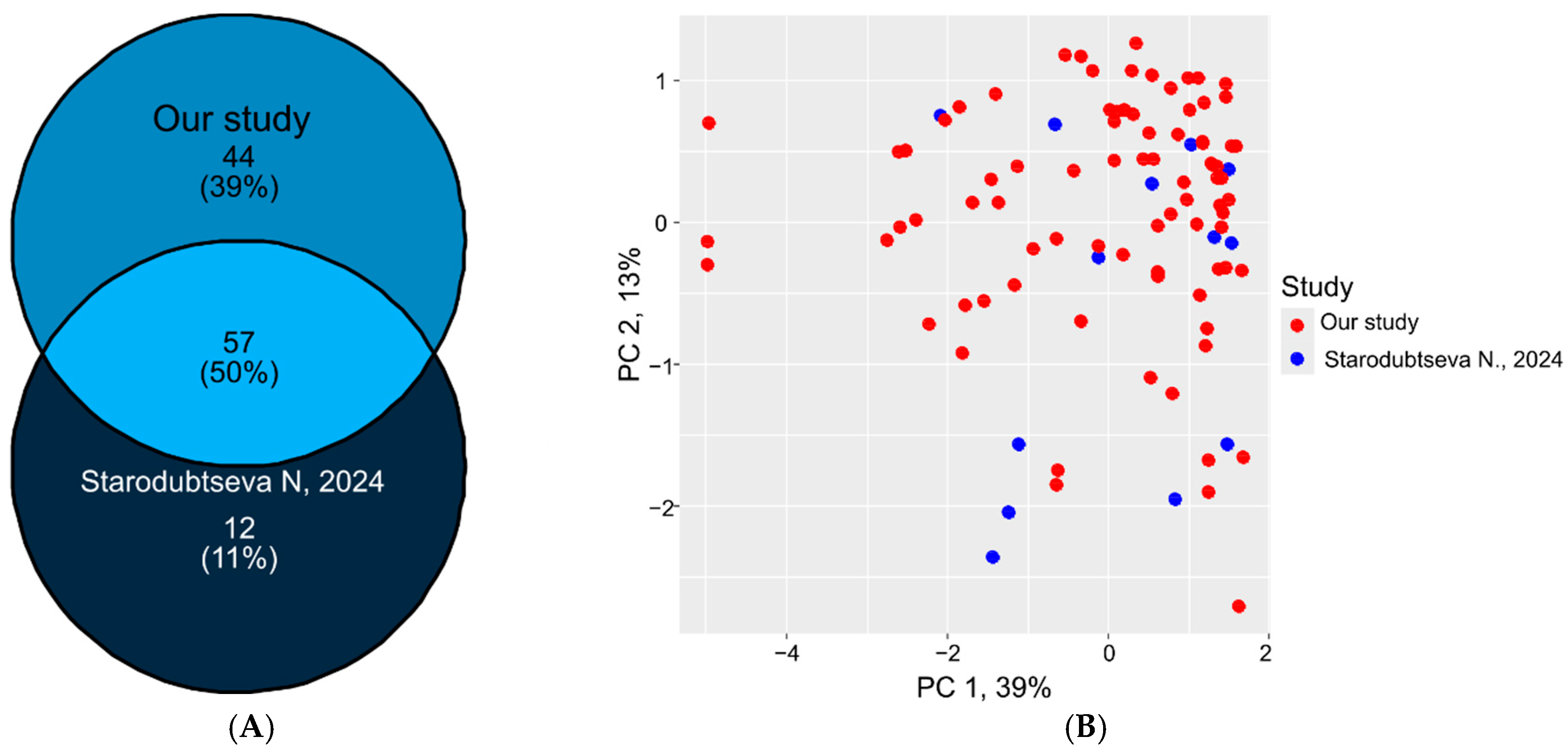

2.5. Proteomic Data Comparison and Validation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

4.2. Sample Preparation

4.3. LC-MRM-MS Analysis

4.4. Data Preprocessing, Quality Control and Quantitative Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis and Normalization

4.6. Reference Value Establishment and Clinical Parameter Association

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| PE | Preeclampsia |

| IUGR | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| SIS | Stable isotope-labeled standards |

| NAT | Natural synthetic proteotypic peptides |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| DIA | Data-independent acquisition |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| PEA | Proximity Extension Assay |

| HLOQ | The highest limit of quantification |

| UHPLC | Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography-mass-spectrometry |

| LLOQ | The lowest limit of quantification |

| LOESS | Locally estimated scatterplot smoothing |

| MoM | Multiply of medians |

| MRM | Multiply reaction monitoring |

| MS | Mass-spectrometry |

| QC | Quality control |

| SPE | Solid phase extraction |

| MAP | Mean arterial pressure |

| UtA-PI | Pulsatility index of the left and right uterine arteries |

References

- Beimers, W.F.; Overmyer, K.A.; Sinitcyn, P.; Lancaster, N.M.; Quarmby, S.T.; Coon, J.J. Technical Evaluation of Plasma Proteomics Technologies. J. Proteome Res. 2025, 24, 3074–3087. [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.B.; Suhre, K.; Gibson, B.W. Promises and Challenges of populational Proteomics in Health and Disease. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2024, 23, 100786. [CrossRef]

- Čuklina, J.; Lee, C.H.; Williams, E.G.; Sajic, T.; Collins, B.C.; Rodríguez Martínez, M.; Sharma, V.S.; Wendt, F.; Goetze, S.; Keele, G.R.; et al. Diagnostics and correction of batch effects in large-scale proteomic studies: a tutorial. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2021, 17, e10240. [CrossRef]

- Badrick, T. Biological variation: Understanding why it is so important? Pract. Lab. Med. 2021, 23, e00199. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Gong, C.X.; Duan, C.M.; Huang, J.C.; Yang, G.Q.; Yuan, J.J.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, X.; Yang, Q. Age-Dependent Changes in the Plasma Proteome of Healthy Adults. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2020, 24, 846–856. [CrossRef]

- Murtoniemi, K.; Kalapotharakos, G.; Vahlberg, T.; Räikkonen, K.; Kajantie, E.; Hämäläinen, E.; Åkerström, B.; Villa, P.M.; Hansson, S.R.; Laivuori, H. Longitudinal changes in plasma hemopexin and alpha-1-microglobulin concentrations in women with and without clinical risk factors for preeclampsia. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0226520. [CrossRef]

- García-Bailo, B.; Brenner, D.R.; Nielsen, D.; Lee, H.J.; Domanski, D.; Kuzyk, M.; Borchers, C.H.; Badawi, A.; Karmali, M.A.; El-Sohemy, A. Dietary patterns and ethnicity are associated with distinct plasma proteomic groups. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 352–361. [CrossRef]

- Kononikhin, A.S.; Starodubtseva, N.L.; Brzhozovskiy, A.G.; Tokareva, A.O.; Kashirina, D.N.; Zakharova, N. V.; Bugrova, A.E.; Indeykina, M.I.; Pastushkova, L.K.; Larina, I.M.; et al. Absolute Quantitative Targeted Monitoring of Potential Plasma Protein Biomarkers: A Pilot Study on Healthy Individuals. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2403. [CrossRef]

- Kolenc, Z.; Pirih, N.; Gretic, P.; Kunej, T. Top Trends in Multiomics Research: Evaluation of 52 Published Studies and New Ways of Thinking Terminology and Visual Displays. Omi. A J. Integr. Biol. 2021, 25, 681–692. [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S.; Bartok, B.; Oler, E.; Liang, K.Y.H.; Budinski, Z.; Berjanskii, M.; Guo, A.; Cao, X.; Wilson, M. MarkerDB: An online database of molecular biomarkers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1259–D1267. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.L. The clinical plasma proteome: A survey of clinical assays for proteins in plasma and serum. Clin. Chem. 2010, 56, 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.; Sinha, S.; Shen, D.; Kuhn, E.W.; Keyes, M.J.; Shi, X.; Benson, M.D.; O’Sullivan, J.F.; Keshishian, H.; Farrell, L.A.; et al. Aptamer-Based Proteomic Profiling Reveals Novel Candidate Biomarkers and Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2016, 134, 270–285. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.J.; Wilcox, B.E.; Benz, R.W.; Babbar, N.; Boragine, G.; Burrell, T.; Christie, E.B.; Croner, L.J.; Cun, P.; Dillon, R.; et al. A plasma-based protein marker panel for colorectal cancer detection identified by multiplex targeted mass spectrometry. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2016, 15, 186-194.e13. [CrossRef]

- Landegren, U.; Hammond, M. Cancer diagnostics based on plasma protein biomarkers: hard times but great expectations. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 1715–1726. [CrossRef]

- Tans, R.; Verschuren, L.; Wessels, H.J.C.T.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Tack, C.J.; Gloerich, J.; van Gool, A.J. The future of protein biomarker research in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2019, 16, 105–115. [CrossRef]

- Zakharova, N. V; Bugrova, A.E.; Indeykina, M.I.; Fedorova, Y.B.; Kolykhalov, I. V; Gavrilova, S.I.; Nikolaev, E.N.; Kononikhin, A.S. Proteomic Markers and Early Prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochemistry. (Mosc). 2022, 87, 762–776. [CrossRef]

- Starodubtseva, N.; Tokareva, A.; Kononikhin, A.; Brzhozovskiy, A.; Bugrova, A.; Kukaev, E.; Muminova, K.; Nakhabina, A.; Frankevich, V.E.; Nikolaev, E.; et al. First-Trimester Preeclampsia-Induced Disturbance in Maternal Blood Serum Proteome: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10653. [CrossRef]

- Starodubtseva, N.L.; Tokareva, A.O.; Volochaeva, M. V.; Kononikhin, A.S.; Brzhozovskiy, A.G.; Bugrova, A.E.; Timofeeva, A. V.; Kukaev, E.N.; Tyutyunnik, V.L.; Kan, N.E.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics of Maternal Blood Plasma in Isolated Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16832. [CrossRef]

- Gaither, C.; Popp, R.; Mohammed, Y.; Borchers, C.H. Determination of the concentration range for 267 proteins from 21 lots of commercial human plasma using highly multiplexed multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Analyst 2020, 145, 3634–3644. [CrossRef]

- Kitteringham, N.R.; Jenkins, R.E.; Lane, C.S.; Elliott, V.L.; Park, B.K. Multiple reaction monitoring for quantitative biomarker analysis in proteomics and metabolomics. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2009, 877, 1229–1239. [CrossRef]

- Geyer, P.E.; Holdt, L.M.; Teupser, D.; Mann, M. Revisiting biomarker discovery by plasma proteomics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2017, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Álvez, M.B.; Edfors, F.; von Feilitzen, K.; Zwahlen, M.; Mardinoglu, A.; Edqvist, P.H.; Sjöblom, T.; Lundin, E.; Rameika, N.; Enblad, G.; et al. Next generation pan-cancer blood proteome profiling using proximity extension assay. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kotol, D.; Woessmann, J.; Hober, A.; Álvez, M.B.; Tran Minh, K.H.; Pontén, F.; Fagerberg, L.; Uhlén, M.; Edfors, F. Absolute Quantification of Pan-Cancer Plasma Proteomes Reveals Unique Signature in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers (Basel). 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Hüttenhain, R.; Soste, M.; Selevsek, N.; Röst, H.; Sethi, A.; Carapito, C.; Farrah, T.; Deutsch, E.W.; Kusebauch, U.; Moritz, R.L.; et al. Reproducible quantification of cancer-associated proteins in body fluids using targeted proteomics. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 142ra94. [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.M.; Albrecht, V.; Mann, M. MS-Based Proteomics of Body Fluids: The End of the Beginning. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2023, 22, 100577. [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.E.; Mann, M. Mass Spectrometry–Based Proteomics Turns Quantitative. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 252–262. [CrossRef]

- Addona, T.A.; Shi, X.; Keshishian, H.; Mani, D.R.; Burgess, M.; Gillette, M.A.; Clauser, K.R.; Shen, D.; Lewis, G.D.; Farrell, L.A.; et al. A pipeline that integrates the discovery and verification of plasma protein biomarkers reveals candidate markers for cardiovascular disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 635–643. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.J.; Su, E.C.Y.; Tsai, I.L.; Lin, C.Y. Clinical assay for the early detection of colorectal cancer using mass spectrometric wheat germ agglutinin multiple reaction monitoring. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13, 2190. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, M.; Weigl, K.; Tikk, K.; Holland-Letz, T.; Schrotz-King, P.; Borchers, C.H.; Brenner, H. Multiplex quantitation of 270 plasma protein markers to identify a signature for early detection of colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 127, 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Domanski, D.; Percy, A.J.; Yang, J.; Chambers, A.G.; Hill, J.S.; Freue, G.V.C.; Borchers, C.H. MRM-based multiplexed quantitation of 67 putative cardiovascular disease biomarkers in human plasma. Proteomics 2012, 12, 1222–1243. [CrossRef]

- Wortelboer, E.J.; Koster, M.P.H.; Kuc, S.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Bilardo, C.M.; Schielen, P.C.J.I.; Visser, G.H.A. Longitudinal trends in fetoplacental biochemical markers, uterine artery pulsatility index and maternal blood pressure during the first trimester of pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 38, 383–388. [CrossRef]

- Tsiakkas, A.; Duvdevani, N.; Wright, A.; Wright, D.; Nicolaides, K.H. Serum placental growth factor in the three trimesters of pregnancy: Effects of maternal characteristics and medical history. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 45, 591–598. [CrossRef]

- Papapavlou Lingehed, G.; Hellberg, S.; Huang, J.; Khademi, M.; Kockum, I.; Carlsson, H.; Tjernberg, I.; Svenvik, M.; Lind, J.; Blomberg, M.; et al. Plasma protein profiling reveals dynamic immunomodulatory changes in multiple sclerosis patients during pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Pernemalm, M.; Sandberg, A.; Zhu, Y.; Boekel, J.; Tamburro, D.; Schwenk, J.M.; Björk, A.; Wahren-Herlenius, M.; Åmark, H.; Östenson, C.G.; et al. In-depth human plasma proteome analysis captures tissue proteins and transfer of protein variants across the placenta. Elife 2019, 8, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; Silva, M.; Papadopoulos, S.; Wright, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Serum pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A in the three trimesters of pregnancy: Effects of maternal characteristics and medical history. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 46, 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Rex, D.A.B.; Schuster, D.; Neely, B.A.; Rosano, G.L.; Volkmar, N.; Momenzadeh, A.; Peters-Clarke, T.M.; Egbert, S.B.; Kreimer, S.; et al. Comprehensive Overview of Bottom-Up Proteomics Using Mass Spectrometry. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2024, 4, 338–417. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E.; Galindo, A.N.; Dayon, L.; Cominetti, O. Assessing normalization methods in mass spectrometry-based proteome profiling of clinical samples. BioSystems 2022, 215–216, 104661. [CrossRef]

- Chua, A.E.; Pfeifer, L.D.; Sekera, E.R.; Hummon, A.B.; Desaire, H. Workflow for Evaluating Normalization Tools for Omics Data Using Supervised and Unsupervised Machine Learning. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2023, 34, 2775–2784. [CrossRef]

- Yalçın, E.; Aslan, S.; Toğaçar, M.; Demir, S.C. A Hybrid Artificial Intelligence Approach for Down Syndrome Risk Prediction in First Trimester Screening. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1444. [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, S.; Momsen, G.; Sundberg, K.; Friis-Hansen, L.; Jørgensen, F.S. First-trimester risk calculation for trisomy 13, 18, and 21: Comparison of the screening efficiency between 2 locally developed programs and commercial software. Clin. Chem. 2011, 57, 1023–1031. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Cortes, M.; Arigita, M.; Falguera, G.; Seres, A.; Guix, D.; Baldrich, E.; Acera, A.; Torrent, A.; Rodriguez-Veret, A.; Lopez-Quesada, E.; et al. Contingent screening for Down syndrome completed in the first trimester: A multicenter study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 39, 396–400. [CrossRef]

- Bugrova, A.E.; Strelnikova, P.A.; Kononikhin, A.S.; Zakharova, N. V; Diyachkova, E.O.; Brzhozovskiy, A.G.; Indeykina, M.I.; Kurochkin, I.N.; Averyanov, A. V; Nikolaev, E.N. Targeted MRM-analysis of plasma proteins in frozen whole blood samples from patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Starodubtseva, N.; Poluektova, A.; Tokareva, A.; Kukaev, E.; Avdeeva, A.; Rimskaya, E.; Khodzayeva, Z. Proteome-Based Maternal Plasma and Serum Biomarkers for Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 776. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency ICH guideline M10 on bioanalytical method validation and study sample analysis; 2022; Vol. 44.

- Bhowmick, P.; Roome, S.; Borchers, C.H.; Goodlett, D.R.; Mohammed, Y. An Update on MRMAssayDB: A Comprehensive Resource for Targeted Proteomics Assays in the Community. J. Proteome Res. 2021, 20, 2105–2115. [CrossRef]

- Kuku, K.O.; Oyetoro, R.; Hashemian, M.; Livinski, A.A.; Shearer, J.J.; Joo, J.; Psaty, B.M.; Levy, D.; Ganz, P.; Roger, V.L. Proteomics for heart failure risk stratification: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Stakhneva, E.M.; Striukova, E.V.; Ragino, Y.I. Proteomic studies of blood and vascular wall in atherosclerosis. Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-databases/clinical-laboratory-improvement-amendments-download-data.

- Rifai, N. Tietz Fundamentals of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics; 8th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2018; ISBN 9780323549738.

- Wang, M.; Jiang, L.; Jian, R.; Chan, J.Y.; Liu, Q.; Snyder, M.P.; Tang, H. RobNorm: Model-based robust normalization method for labeled quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics data. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 815–821. [CrossRef]

- Arend, L.; Adamowicz, K.; Schmidt, J.R.; Burankova, Y.; Zolotareva, O.; Tsoy, O.; Pauling, J.K.; Kalkhof, S.; Baumbach, J.; List, M.; et al. Systematic evaluation of normalization approaches in tandem mass tag and label-free protein quantification data using PRONE. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf201. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.A.; Fraser, D.D.; Daley, M.; Cepinskas, G.; Veraldi, N.; Grazioli, S. The plasma proteome differentiates the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) from children with SARS-CoV-2 negative sepsis. Mol. Med. 2024, 30. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, F.; Utermann, G. Lipoprotein(a): Resurrected by genetics. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 6–30. [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas, S. A Test in Context: Lipoprotein(a): Diagnosis, Prognosis, Controversies, and Emerging Therapies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 692–711. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, F. Lipoprotein(a). Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2022, 270, 201–232. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.P.; Wang, M.; Pirruccello, J.P.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ng, K.; Kathiresan, S.; Khera, A. V. Lp(a) (Lipoprotein[a]) Concentrations and Incident Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease New Insights from a Large National Biobank. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 465–474. [CrossRef]

- Bergmark, C.; Dewan, A.; Orsoni, A.; Merki, E.; Miller, E.R.; Shin, M.J.; Binder, C.J.; Hörkkö, S.; Krauss, R.M.; Chapman, M.J.; et al. A novel function of lipoprotein [a] as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 2230–2239. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Valk, F.M.; Bekkering, S.; Kroon, J.; Yeang, C.; Van Den Bossche, J.; Van Buul, J.D.; Ravandi, A.; Nederveen, A.J.; Verberne, H.J.; Scipione, C.; et al. Oxidized phospholipids on Lipoprotein(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation and an inflammatory monocyte response in humans. Circulation 2016, 134, 611–624. [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, L.; Laurell, C.B. The pregnancy zone protein response during gestation: A metabolic challenge. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 1994, 54, 623–629. [CrossRef]

- Fosheim, I.K.; Jacobsen, D.P.; Sugulle, M.; Alnaes-Katjavivi, P.; Fjeldstad, H.E.S.; Ueland, T.; Lekva, T.; Staff, A.C. Serum amyloid A1 and pregnancy zone protein in pregnancy complications and correlation with markers of placental dysfunction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100794. [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Xuan, C.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X.C.; Liu, Z.G.; He, G.W. Identification of Altered Plasma Proteins by Proteomic Study in Valvular Heart Diseases and the Potential Clinical Significance. PLoS One 2013, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kang, U.B.; Kim, S.; Lee, H.B.; Moon, H.G.; Han, W.; Noh, D.Y. A validation study of a multiple reaction monitoring-based proteomic assay to diagnose breast cancer. J. Breast Cancer 2020, 23, 113–114. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, L.; Erlandsson, L.; Åkerström, B.; Miranda, J.; Paules, C.; Crovetto, F.; Crispi, F.; Gratacos, E.; Hansson, S.R. Hemopexin and α1-microglobulin heme scavengers with differential involvement in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. PLoS One 2020, 15, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kalapotharakos, G.; Murtoniemi, K.; Åkerström, B.; Hämäläinen, E.; Kajantie, E.; Räikkönen, K.; Villa, P.; Laivuori, H.; Hansson, S.R. Plasma heme scavengers alpha-1microglobulin and hemopexin as biomarkers in high-risk pregnancies. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 300. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, U.D.; Gram, M.; Ranstam, J.; Thilaganathan, B.; Åkerström, B.; Hansson, S.R. Fetal hemoglobin, α1-microglobulin and hemopexin are potential predictive first trimester biomarkers for preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2016, 6, 103–109. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.C.S.; Stenhouse, E.J.; Crossley, J.A.; Aitken, D.A.; Cameron, A.D.; Michael Connor, J. Early pregnancy levels of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and the risk of intrauterine growth restriction, premature birth, preeclampsia, and stillbirth. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 1762–1767. [CrossRef]

- Krantz, D.; Goetzl, L.; Simpson, J.L.; Thom, E.; Zachary, J.; Hallahan, T.W.; Silver, R.; Pergament, E.; Platt, L.D.; Filkins, K.; et al. Association of extreme first-trimester free human chorionic gonadotropin-β, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A, and nuchal translucency with intrauterine growth restriction and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1452–1458. [CrossRef]

- Livrinova, V.; Petrov, I.; Samardziski, I.; Jovanovska, V.; Boshku, A.A.; Todorovska, I.; Dabeski, D.; Shabani, A. Clinical importance of low level of PAPP-A in first trimester of pregnancy-An obstetrical dilemma in chromosomally normal fetus. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 1475–1479. [CrossRef]

- Dugoff, L.; Hobbins, J.C.; Malone, F.D.; Porter, T.F.; Luthy, D.; Comstock, C.H.; Hankins, G.; Berkowitz, R.L.; Merkatz, I.; Craigo, S.D.; et al. First-trimester maternal serum PAPP-A and free-beta subunit human chorionic gonadotropin concentrations and nuchal translucency are associated with obstetric complications: A population-based screening study (The FASTER Trial). Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1446–1451. [CrossRef]

- Savvidou, M.D.; Syngelaki, A.; Muhaisen, M.; Emelyanenko, E.; Nicolaides, K.H. First trimester maternal serum free β-human chorionic gonadotropin and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A in pregnancies complicated by diabetes mellitus. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 119, 410–416. [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, R.; Atis, A.; Aydin, Y.; Acar, D.; Kiyak, H.; Topbas, F. PAPP-A concentrations change in patients with gestational diabetes. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. (Lahore). 2020, 40, 190–194. [CrossRef]

- Poon, L.C.Y.; Zymeri, N.A.; Zamprakou, A.; Syngelaki, A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Protocol for measurement of mean arterial pressure at 11-13 weeks’ gestation. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2012, 31, 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Plasencia, W.; Maiz, N.; Bonino, S.; Kaihura, C.; Nicolaides, K.H. Uterine artery Doppler at 11 + 0 to 13 + 6 weeks in the prediction of preeclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 30, 742–749. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, B.X.; Pratt, B.S.; Egertson, J.D.; MacCoss, M.J.; Smith, R.D.; Baker, E.S. Using Skyline to Analyze Data-Containing Liquid Chromatography, Ion Mobility Spectrometry, and Mass Spectrometry Dimensions. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 29, 2182–2188. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, J.; Lim, M.S.; Seong, S.J.; Seo, J.J.; Park, S.M.; Lee, H.W.; Yoon, Y.R. Quantile normalization approach for liquid chromatography- mass spectrometry-based metabolomic data from healthy human volunteers. Anal. Sci. 2012, 28, 801–805. [CrossRef]

- Ballman, K. V.; Grill, D.E.; Oberg, A.L.; Therneau, T.M. Faster cyclic loess: Normalizing RNA arrays via linear models. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 2778–2786. [CrossRef]

- Bolstad, B.M.; Irizarry, R.A.; Astrand, M.; Speed, T.P. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.E.; Li, C.; Rabinovic, A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 2007, 8, 118–127. [CrossRef]

- Leek, J.T.; Johnson, W.E.; Parker, H.S.; Jaffe, A.E.; Storey, J.D. The SVA package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 882–883. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Reshaping data with the reshape package. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 21, 1–20.

- Wickham, H. Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis: ggplot2; 2008; ISBN 978-0-387-78170-9.

- Kolde, R. pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps; 2025.

| Clinical Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 30.5 (27.4; 32.8) 20.5 - 37.3 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.2 (19.2; 23.0) 15.6 - 30.1 |

| Gestational age at blood collection, weeks | 12.4 (12.1; 12.9) 11.3 - 13.9 |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks | 39.5 (39; 40.2) 37.5 - 41.2 |

| Uterine myoma, n(%) | 8(10%) |

| Anemia during pregnancy, n(%) | 27(33%) |

| Fetal sex (male) | 41(49%) |

| Parity, n(%) | 1 - 40(48%) 2 - 32(39%) 3 - 10(12%) 4 - 1(1%) |

| 1st screening | |

| PAPPA, mLU/mL | 3.03 (2.08; 4.59) 0.598 - 9.761 |

| PAPPA, MoM | 0.95 (0.65; 1.47) 0.196 - 4.271 |

| PlGF, pg/ml | 25.3 (20.2; 35) 13.3 - 54 |

| PlGF, MoM | 0.84 (0.61; 1.03) 0.374 - 1.521 |

| free β-HGC, ng/ml | 52.61 (37.38; 75.54) 12.57 - 224.31 |

| free β-HGC, MoM | 0.99 (0.78; 1.2) 0.533 - 1.667 |

| UtA-PI | 1.57 (1.29; 2.02) 0.89 - 2.655 |

| UtA-PI, MoM | 0.99 (0.78; 1.2) 0.533 - 1.667 |

| MAP, mmHg | 83.33 (77.46; 86.46) 66 - 98.833 |

| MAP, MoM | 0.98 (0.94; 1.04) 0.8027 - 1.1755 |

| Risk of PE | 1357.5 (516.75; 2816.5) 63 - 15320 |

| Risk of IUGR | 554 (377; 877) 81 - 2501 |

| Risk of preterm delivery | 2115.5 (890; 3209.75) 5 - 5026 |

| Clinical | Direction of Association | Protein (Gene Name) |

|---|---|---|

| BMI | direct | ATRN, CA4BPA, CP, F12, C1QA, C1R, C3, CFB, CFI, HP, HABP2, APCS |

| reverse | AHSG, SERPINC1, APOA4, APOD, CA1, HBA1, IGFBP3, SERPING1, AZGP1 | |

| Age | direct | SERPIND1 |

| reverse | A2M | |

| Parity | direct | AGT, APOC3, CNDP1, CA1, IGHG1, KNG1, PLG |

| reverse | ATRN, F12, SERPINA6, SELL, PAPPA, ALB | |

| Gestational age at blood collection | direct | VTN |

| reverse | HRG | |

| Uterine myoma | direct | KNG1 |

| reverse | APOA4, SPARC | |

| Male fetal sex | direct | BTD, CA1 |

| reverse | SERPINA3, APOH, CP, C5, C9, HBA1, LRG1, PROS1, AZGP1 |

| Screening | LC-MS | R | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IU/ml | nM | 0.65 | <0.001 |

| MoM | nM | 0.56 | <0.001 |

| MoM | MoM | 0.58 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).