Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Gravitationally Bound Systems: The Current Paradigm

1.2. The Hubble-Lemaître Parameter

1.3. Local Cosmology

2. Mercury and Venus

2.1. Planetary Recession

2.2. The Absence of Natural Satellites

3. Earth and Moon

3.1. Introduction

3.2. Lunar Laser Ranging Program (LLRP)

3.3. Ancient Tidal Rhythmites and Fossil Corals

3.3.1. Introduction

3.3.2. Tidal Rhythmites and Lunar Recession

3.3.3. Fossil Corals and Lunar Recession

3.4. Lunar Relative Mean Motion Acceleration

3.5. The Faint Young Sun Paradox

4. Mars

4.1. The Faint Young Sun Paradox

4.2. Recession of Mars

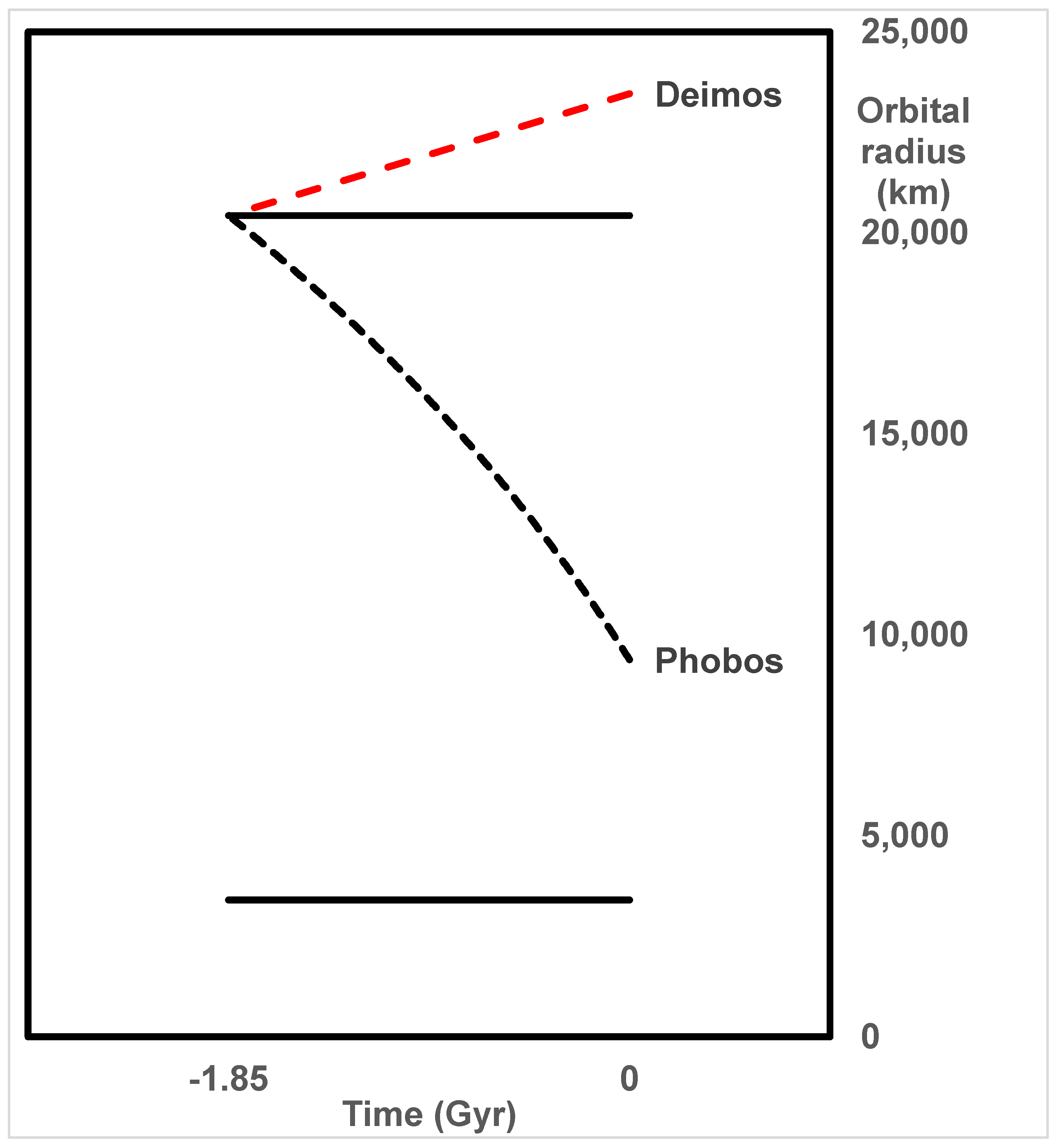

4.3. Deimos and Phobos

4.3.1. Introduction

4.3.2. Recession of Deimos

4.3.3. The Orbit of Phobos

5. Jupiter

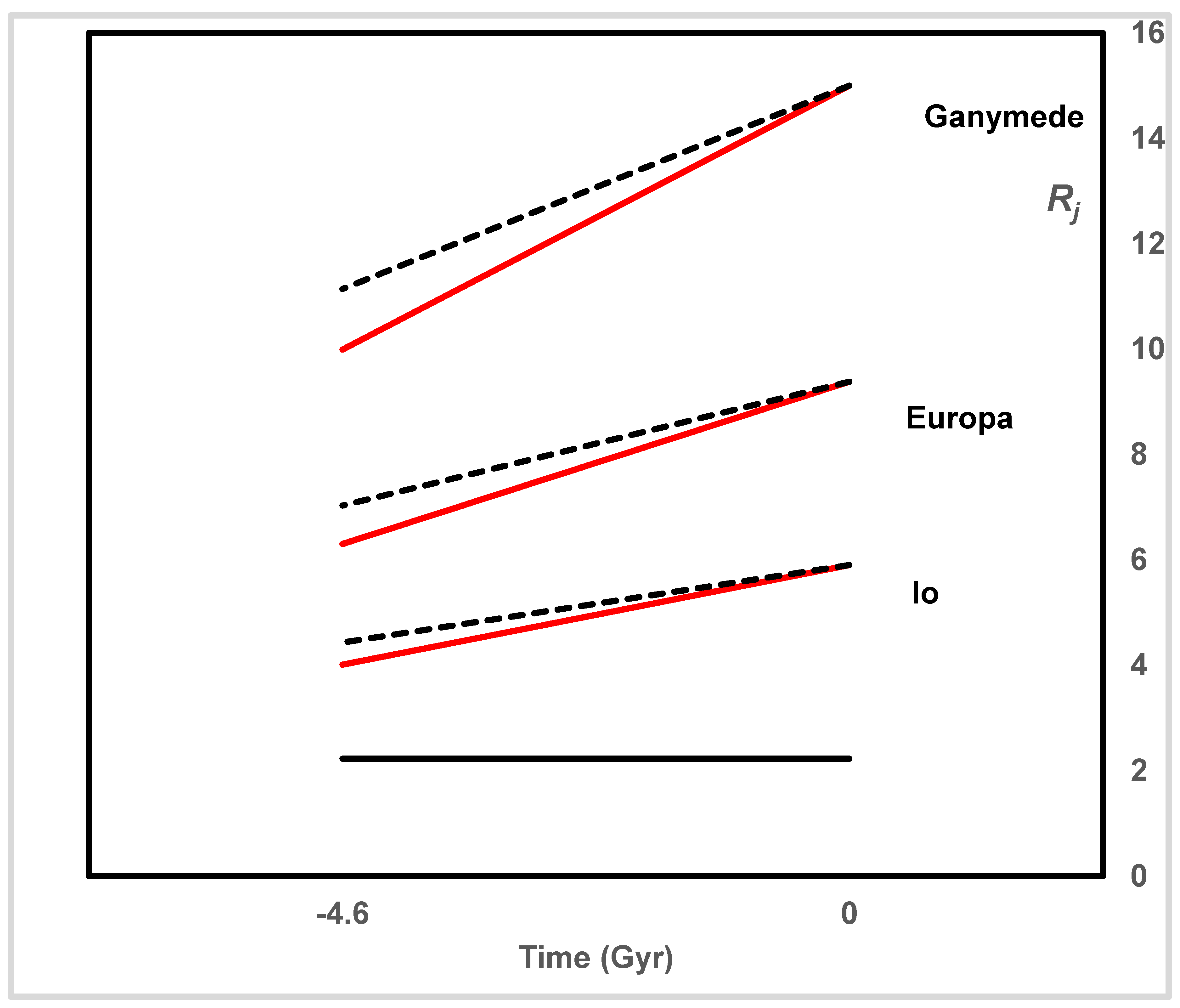

5.1. Jupiter and Its Moons

5.1.1. The Galilean Moons

6. Saturn

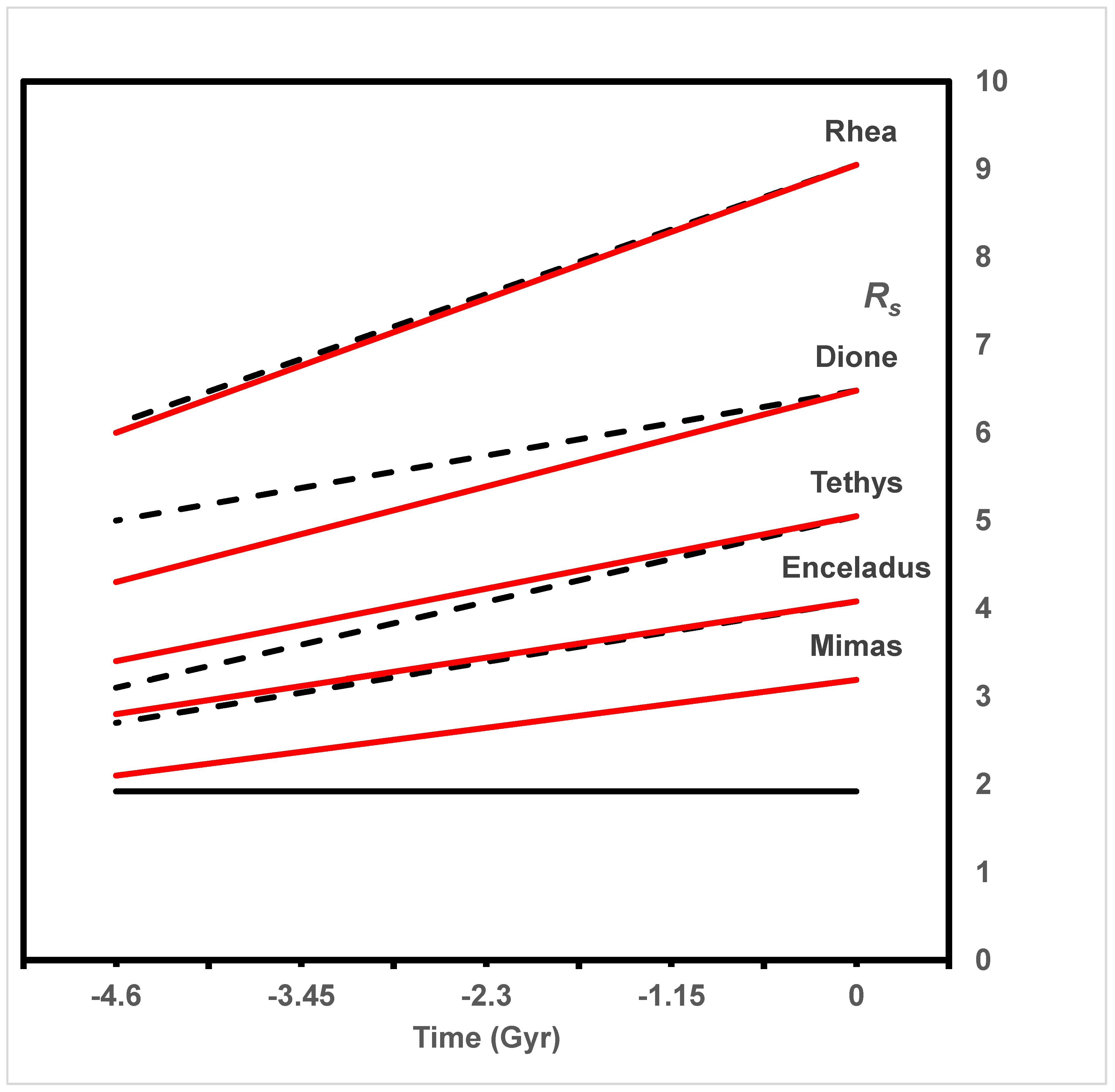

6.1. Saturn and Its Moons

6.1.1. Titan

6.1.2. The Large Inner Moons

7. Uranus

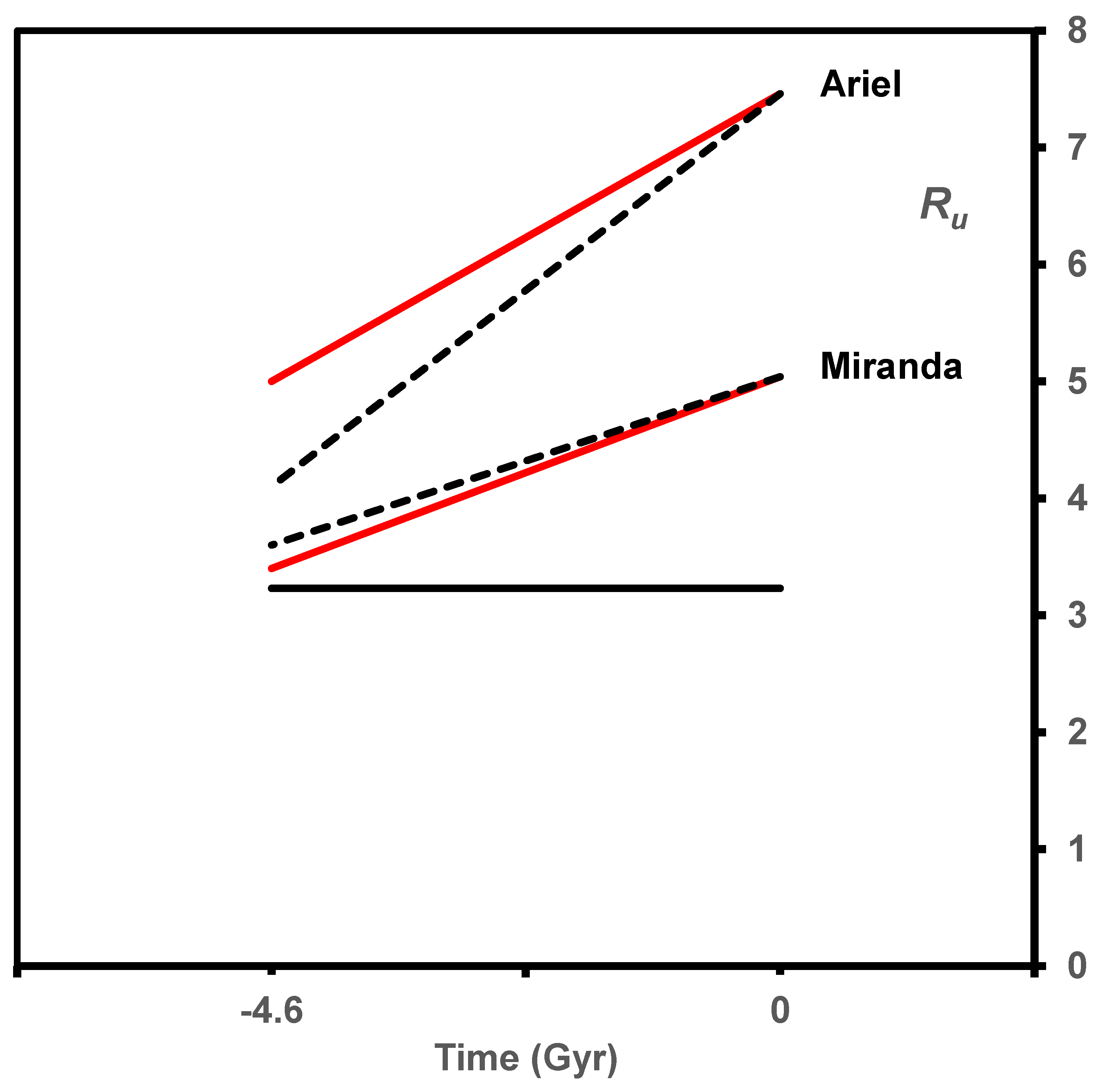

7.1. Uranus and Its Moons

7.1.1. Miranda and Ariel

8. Neptune

8.1. Neptune and Its Moons

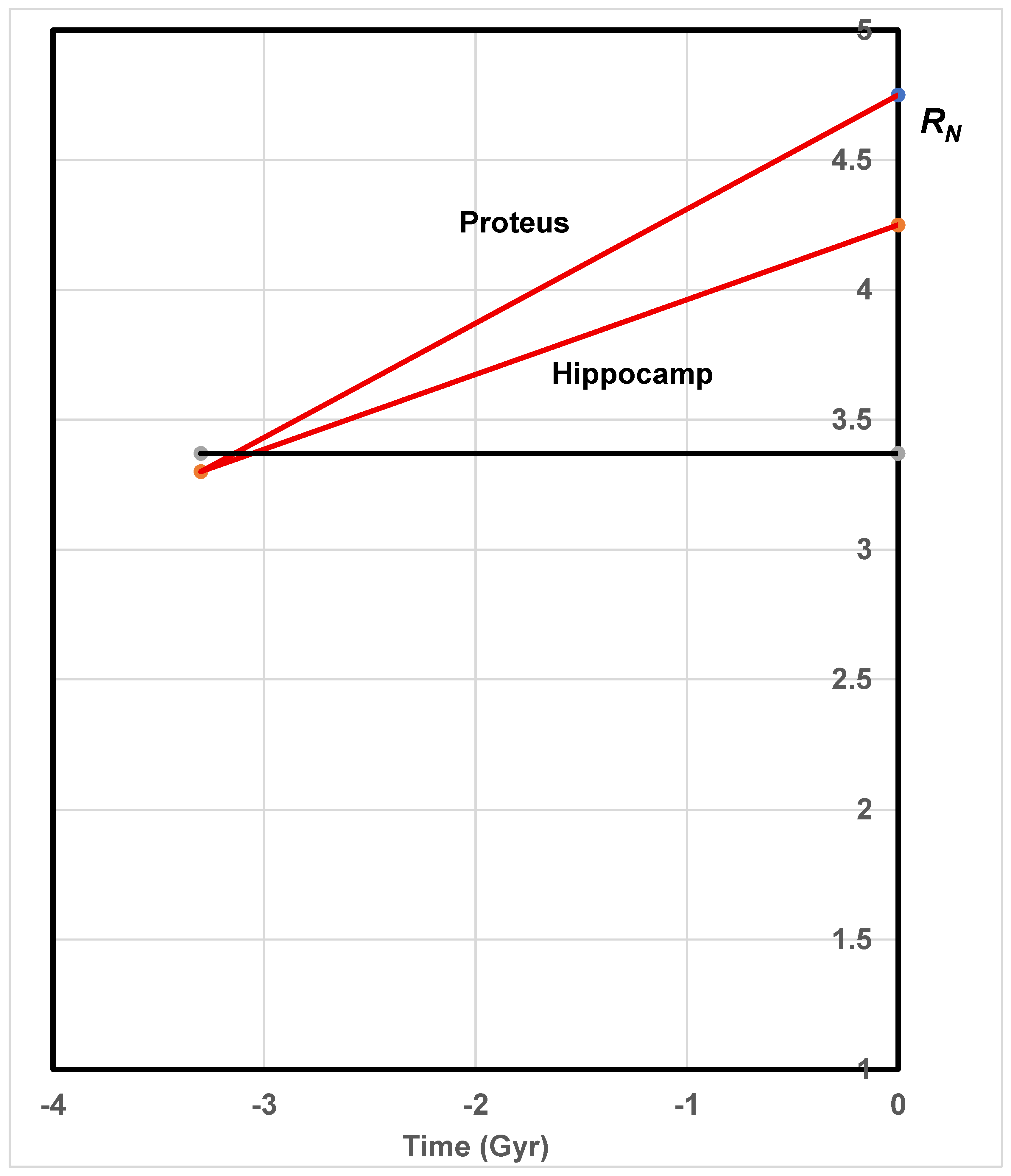

8.1.1. Hippocamp and Proteus

9. Miscellaneous Issues

9.1. The Pioneer ‘Anomaly’

9.2. Condensed Matter

9.3. The Sun and the Gas Giants

9.4. Kuiper Belt Objects

10. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Rees, M. (Ed.) . Universe: the definitive visual guide. Dorling Kindersley Ltd.: London, UK, 2020, ISBN: 978-1-4093-7650-7. 2012.

- Baird, C. S. How long before the expansion of the universe causes our Earth to drift away from the Sun? Available online: https://wtamu.edu/~cbaird/sq/2013/05/04/how-long-before-the-expansion-of-the-universe-causes-our-earth-to-drift-away-from-the-sun/. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Wiegert, C. Physics questions people ask Fermilab. Available online: https://www.fnal.gov/pub/science/inquiring/questions/expandinguniverse.html. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Palma, C. The implications of Hubble’s Law: An expanding universe. Available online: https://www.e-education.psu.edu/astro801/content/l10_p4.html. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Suntola, T. THE DYNAMIC UNIVERSE - Toward a unified picture of physical reality; : CITY, COUNTRY ISBN:.

- Suntola, T. In a holistic perspective, time is absolute and relativity a direct consequence of the conservation of total energy. Phys. Essays 2021, 34, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Astronomical Union Resolution B4. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1T6FPxirWzZlwwykZy2-lCVmDO78PiMVJ/view (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Knox, L.; Millea, M. The Hubble hunter’s guide. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.03663v1. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Poulin, V. The Hubble tension. Cerncourier, Available online:. Available online: https://cerncourier.com/a/the-hubble-tension/, (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Dumin, Y. V. Is the Hubble constant scale-dependent? Gravitation Cosmol. 2018, 24(2), 171-172. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1712.09340.

- Lee, N.; Braglia, M.; Ali-Haïmond, Y. What it takes to solve the Hubble tension through scale-dependent modifications of the primordial power spectrum. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2504.07966,. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Dumin, Y. A new application of the lunar laser retroreflectors: Searching for the “local” hubble expansion. Adv. Space Res. 2003, 31, 2461–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L. A. Any ideas? New Sci., 1970, 45(684), 127.

- McVittie, G.C. The Mass-Particle in an Expanding Universe. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1933, 93, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnor, W.B. The cosmic expansion and local dynamics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1996, 282, 1467–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnor, W.B. Local Dynamics and the Expansion of the Universe. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 2000, 32, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooperstock, F.I.; Faraoni, V.; Vollick, D.N. The Influence of the Cosmological Expansion on Local Systems. Astrophys. J. 1998, 503, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Available online:. Available online: https://public.nrao.edu/ask/can-one-measure-the-expansion-of-the-universe-within-our-solar-system/. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Einstein, A.; de Sitter, W. On the Relation between the Expansion and the Mean Density of the Universe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1932, 18, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, P. J. E. Cosmology’s century: an inside history of our modern understanding of the Universe; Princeton University Press: Princeton, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-691-20166-5. [Google Scholar]

- Křížek, M. Dark energy and the anthropic principle. New Astron. 2012, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumin, Y. V. On a probable manifestation of Hubble expansion at the local scales, as inferred from LLR data. [CrossRef]

- Dumin, Y.V. TESTING THE DARK-ENERGY-DOMINATED COSMOLOGY BY THE SOLAR-SYSTEM EXPERIMENTS. Proceedings of the MG11 Meeting on General Relativity. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, GermanyDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1752–1754.

- Dumin, Y. V. Local Hubble expansion: current state of the problem. [CrossRef]

- King, L.A.; Sipilä, H. Cosmological expansion in the Solar System. Phys. Essays 2022, 35, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křížek, M.; Gueorguiev, V.G.; Maeder, A. An Alternative Explanation of the Orbital Expansion of Titan and Other Bodies in the Solar System. Gravit. Cosmol. 2022, 28, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křížek, M.; Somer, L. Antigravity—Its Manifestations and Origin. Int. J. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 03, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křížek, M.; Somer, L. Manifestations of dark energy in the solar system. Gravit. Cosmol. 2015, 21, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Křižek, M.; Somer, L. Anthropic principle and the local Hubble expansion. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cosmology on Small Scales, Institute of Mathematics, Czech Academy of Science, Prague, Czechia, Křižek M. and Dumin, Y., Eds. Available online: https://css2016.math.cas.cz/proceedingsCSS2016.pdf. (accessed on 21 July 2025). 2016. Available online: https://css2016.math.cas.cz/proceedingsCSS2016.pdf. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Křížek, M.; Somer, L. Mathematical Aspects of Paradoxes in Cosmology; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sipilä, H. Is the Solar System expanding?.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Sipilä, H. Recalculation of the Moon retreat velocity supports expansion of gravitationally bound local systems, In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cosmology on Small Scales, Institute of Mathematics, Czech Academy of Science, Prague, Czechia, 2022, Křižek M. and Dumin, Y., Eds. Available online: https://css2022.math.cas.cz/proceedingsCSS2022.pdf. (accessed on 21 July 2025); Available online: https://css2022.math.cas.cz/proceedingsCSS2022.pdf. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- King, L.A. Recession of Deimos from Mars: A cosmological interpretation. Phys. Essays 2024, 37, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A. Cosmological recession of the Galilean moons from Jupiter. Phys. Essays 2024, 37, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.A. Evolution of Saturn’s Large Inner Moons: An Alternative Explanation. Gravit. Cosmol. 2025, 31, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L. A.; Orbital expansion of the Uranus moons Miranda and Ariel: cosmological interpretation. Phys. Essays 2025, 38(1), 55-56, Available online:. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Leslie-King-5/research. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- King, L.A. Orbital evolution of the Neptunian moons Hippocamp and Proteus. Phys. Essays 2025, 38, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V. Cosmological expansion rate – various measurement results and interpretation. [CrossRef]

- Müller, V. Cosmic expansion clues from the Earth. [CrossRef]

- Steigerwald, W. NASA team studies middle-aged Sun by tracking motion of Mercury. Available online: https://www.nasa.gov/missions/nasa-team-studies-middle-aged-sun-by-tracking-motion-of-mercury/. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Genova, A.; Mazarico, E.; Goossens, S.; Lemoine, F.G.; Neumann, G.A.; Smith, D.E.; Zuber, M.T. Solar system expansion and strong equivalence principle as seen by the NASA MESSENGER mission. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H. S. The rotation of the Earth, and secular acceleration of the Sun, Moon and planets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1939, 99, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnik, Y.B.; Masreliez, C.J. Secular Trends in the Mean Longitudes of Planets Derived from Optical Observations. Astron. J. 2004, 128, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasinsky, G.A.; Brumberg, V.A. Secular increase of astronomical unit from analysis of the major planet motions, and its interpretation. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 2004, 90, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.; Yurukeu, M.; Nnanna, G. How fast is the distance between Earth and the Sun changing in the Solar System? [CrossRef]

- Wade, N. Three Origins of the Moon. Nature 1969, 223, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, J.O.; Bender, P.L.; Faller, J.E.; Newhall, X.X.; Ricklefs, R.L.; Ries, J.G.; Shelus, P.J.; Veillet, C.; Whipple, A.L.; Wiant, J.R.; et al. Lunar Laser Ranging: A Continuing Legacy of the Apollo Program. Science 1994, 265, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Z.; Lei, Y. Experimental measurement of growth patterns on fossil corals: Secular variation in ancient Earth-Sun distances. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 4010–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.E. Geological constraints on the Precambrian history of Earth's rotation and the Moon's orbit. Rev. Geophys. 2000, 38, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, R.; Arima, M. Tidal rhythmites and their implications. Earth-Science Rev. 2005, 69, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azarevich, V.L.L.; Azarevich, M.B. Lunar recession encoded in tidal rhythmites: a selective overview with examples from Argentina. Geo-Marine Lett. 2017, 37, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, P.G.K.; Pompea, S.M. Nautiloid growth rhythms and dynamical evolution of the Earth–Moon system. Nature 1978, 275, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeder, A.M.; Gueorguiev, V.G. On the relation of the lunar recession and the length-of-the-day. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2021, 366, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapront, J.; Chapront-Touzé, M.; Francou, G. A new determination of lunar orbital parameters, precession constant and tidal acceleration from LLR measurements. Astron. Astrophys. 2002, 387, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagan, C.; Mullen, G. Earth and Mars: Evolution of Atmospheres and Surface Temperatures. Science 1972, 177, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feulner, G. The faint young Sun problem. Rev. Geophys. 2012, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, B.K.; Tupper, A.S.; Pudritz, R.E.; Higgs, P.G. Constraining the Time Interval for the Origin of Life on Earth. Astrobiology 2018, 18, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumin, Y.V.; Savinykh, E.S. Křížek–Somer Anthropic Principle and the Problem of Local Hubble Expansion. Gravit. Cosmol. 2025, 31, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squyres, S.W. Urey prize lecture: Water on Mars. Icarus 1989, 79, 229–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.; Cavosie, A.J.; Fougerouse, D.; Ciobanu, C.L.; Rickard, W.D.A.; Saxey, D.W.; Benedix, G.K.; Bland, P.A. Zircon trace element evidence for early hydrothermal activity on Mars. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadq3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeder A., M.; Bouvier, P. Scale invariance, metrical connection and the motions of astronomical bodies. Astron. Astrophys. 1979, 73, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Castelvecchi, D. First up-close images of Mars’s little-known moon Deimos. Nature 2023, 617, 19–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, A.; Khan, A.; Efroimsky, M.; Kruglyakov, M.; Giardini, D. Dynamical evidence for Phobos and Deimos as remnants of a disrupted common progenitor. Nat. Astron. 2021, 5, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MMX Martian Moons Exploration. Available online: https://www.mmx.jaxa.jp/en/. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Shor, V.A. The motion of the Martian satellites. Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 1975, 12, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/mars/moons/phobos/. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Available online: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/europa-clipper/. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- The European Space Agency, Juice_Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Juice. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Lari, G.; Saillenfest, M.; Fenucci, M. Long-term evolution of the Galilean satellites: the capture of Callisto into resonance. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 639, A40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainey, V.; Arlot, J.-E.; Karatekin, Ö.; Van Hoolst, T. Strong tidal dissipation in Io and Jupiter from astrometric observations. Nature 2009, 459, 957–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, M.; Rhoden, A.R. Evolution of Saturn’s mid-sized moons. Nat. Astron. 2019, 3, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, J.; Luan, J.; Quataert, E. Resonance locking as the source of rapid tidal migration in the Jupiter and Saturn moon systems. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 458, 3867–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćuk, M.; Dones, L.; Nesvorný, D. DYNAMICAL EVIDENCE FOR A LATE FORMATION OF SATURN’S MOONS. Astrophys. J. 2016, 820, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, L.F.A.; Kegerreis, J.A.; Estrada, P.R.; Ćuk, M.; Eke, V.R.; Cuzzi, J.N.; Massey, R.J.; Sandnes, T.D. A Recent Impact Origin of Saturn’s Rings and Mid-sized Moons. Astrophys. J. 2023, 955, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainey, V.; Casajus, L.G.; Fuller, J.; Zannoni, M.; Tortora, P.; Cooper, N.; Murray, C.; Modenini, D.; Park, R.S.; Robert, V.; et al. Resonance locking in giant planets indicated by the rapid orbital expansion of Titan. Nat. Astron. 2020, 4, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmo, F. Strong Tidal Dissipation at Uranus? Planet. Sci. J. 2023, 4, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, M.R.; de Pater, I.; Lissauer, J.J.; French, R.S. The seventh inner moon of Neptune. Nature 2019, 566, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showalter, M.R. The rings and small moons of Uranus and Neptune. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2020, 378, 20190482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banfield, D.; Murray, N. A dynamical history of the inner Neptunian satellites. Icarus 1992, 99, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.A.; Swindle, T.D.; Kring, D.A. Support for the Lunar Cataclysm Hypothesis from Lunar Meteorite Impact Melt Ages. Science 2000, 290, 1754–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.D.; Laing, P.A.; Lau, E.L.; Liu, A.S.; Nieto, M.M.; Turyshev, S.G. Study of the anomalous acceleration of Pioneer 10 and 11. Phys. Rev. D 2002, 65, 082004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachièze-Rey, M. Cosmology in the solar system: the Pioneer effect is not cosmological. Class. Quantum Gravity 2007, 24, 2735–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, S.J.; Bromley, B.C. THE FORMATION OF PLUTO'S LOW-MASS SATELLITES. Astron. J. 2013, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, C.A.; Asphaug, E.; Emsenhuber, A.; Melikyan, R. Capture of an ancient Charon around Pluto. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 18, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmology on Small Scales. Institute of Mathematics, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Available online:. Available online: https://css2024.math.cas.cz/proceedingsCSS2024.pdf. (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Kuhn, T. S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed.; The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, 1970. ISBN: 0-226-45804-0.

| Planet | Current mean orbital radius (AU) |

Mean orbital radius (AU) in 7 Gyr |

Predicted recessional velocity from the Sun (m yr-1) |

| Mercury | 0.39 | 0.58 | 4.18 |

| Venus | 0.72 | 1.08 | 7.78 |

| Earth | 1.00 | 1.50 | 10.8 |

| Mars | 1.52 | 2.28 | 16.4 |

| Jupiter | 5.20 | 7.80 | 56.1 |

| Saturn | 9.54 | 14.4 | 103 |

| Uranus | 19.2 | 29.9 | 207 |

| Neptune | 30.1 | 45.0 | 324 |

| Planet |

Synchronous orbital radius (Rsyn, km) |

Hill radius (RH, km) |

| Mercury | 242,843 | 180,000 |

| Venus | 1,535,681 | 1,000,000 |

| Earth | 35,786 | 1,500,000 |

| Mars | 20,429 | 980,000 |

| Jupiter | 160,052 | 51,000,000 |

| Saturn | 111,606 | 62,000,000 |

| Uranus | 82,674 | 67,000,000 |

| Neptune | 83,395 | 115,000,000 |

| Moon | Orbital eccentricity | Semi-major axis (km/103) |

Sidereal period (days) |

Mass (kg/1015) |

| Phobos | 0.0151 | 9.38 | 0.320 | 10.7 |

| Deimos | 0.00033 | 23.5 | 1.26 | 1.5 |

| Moon | Orbital eccentricity | Semi-major axis (km/106) |

Semi-major axis (RJ) |

Sidereal period (days) |

Mass (kg/1023) |

| Io | 0.0041 | 0.422 | 5.90 | 1.76 | 0.893 |

| Europa | 0.0090 | 0.671 | 9.38 | 3.53 | 0.480 |

| Ganymede | 0.0013 | 1.07 | 15.0 | 7.16 | 1.48 |

| Callisto | 0.0074 | 1.88 | 26.3 | 16.7 | 1.08 |

| Method | Io | Europa | Ganymede | Callisto |

| Lari et al.[69] | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.84 | 0 |

| Hubble-Lemaître law | 0.41 | 0.67 | 1.09 | 1.89 |

| Moon | Relative mean motion acceleration (a)/10-10 yr-1 |

Mean (a)/10-10 yr-1 |

| Io | +0.144 +/- 0.01 | } } 0.62 } |

| Europa | -0.43 +/- 0.10 | |

| Ganymede | -1.57 +/- 0.27 | |

| Hubble-Lemaître parameter/(10-10 yr-1) | 0.71 | |

| Moon | Orbital eccentricity | Semi-major axis (km/106) |

Sidereal period (days) |

Mass (kg/1020) |

| Mimas | 0.020 | 0.186 | 0.94 | 0.375 |

| Enceladus | 0.005 | 0.238 | 1.37 | 1.08 |

| Tethys | 0.001 | 0.295 | 1.89 | 6.17 |

| Dione | 0.002 | 0.378 | 2.74 | 11.0 |

| Rhea | 0.001 | 0.527 | 4.52 | 23.1 |

| Titan | 0.029 | 1.22 | 15.9 | 135 |

| Iapetus | 0.028 | 3.56 | 79.3 | 18.1 |

| Moon |

Current orbital radius (km/105) |

Rs at current position |

Rs tidal at t = 0 |

Orbital advance (km/105) since t = 0 |

Orbital radius (km/105) at t = 0 |

Rs Local expansion at t = 0 |

Recessional velocity (cm yr-1) |

| Rhea | 5.27 | 9.05 | 6.1 | 1.8 | 3.47 | 6.0 | 3.9 |

| Dione | 3.77 | 6.48 | 5.0 | 1.3 | 2.47 | 4.3 | 2.8 |

| Tethys | 2.95 | 5.05 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 1.95 | 3.4 | 2.2 |

| Enceladus | 2.38 | 4.08 | 2.7 | 0.78 | 1.60 | 2.8 | 1.7 |

| Mimas | 1.86 | 3.19 | 2.1 | 0.64 | 1.22 | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| Moon | Semi-major axis (km/105) |

Current relative orbital radius (Ru) |

Estimated relative orbital radius (Ru) at t = 0 Nimmo [76] |

∆Ru Nimmo [76] |

Predicted relative orbital radius (Ru) at t = 0 ‘H-L’ |

∆Ru ‘H-L’ |

| Miranda | 1.29 | 5.04 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 1.6 |

| Ariel | 1.91 | 7.46 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 2.5 |

| Umbriel | 2.66 | 10.4 | - | - | 7.0 | 3.4 |

| Titania | 4.36 | 17.0 | - | - | 11.4 | 5.6 |

| Oberon | 5.83 | 22.8 | - | - | 15.3 | 7.5 |

| Moon | Sidereal period (days) | Semi-major axis (km) | Mass (kg) |

| Hippocamp | 0.9500 | 105,283 | ~ 2 x 1016 |

| Proteus | 1.1223 | 117,646 | ~ 3.9 x 1019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).