1. Introduction

Stroke is a neurological deficit caused by damage to the brain, the central nervous system, and can be broadly categorized into two types: infarction and hemorrhage [

1,

2]. Infarction is the damage to brain neural circuits caused by the closure of blood vessels, while hemorrhage is the damage to nerve cells caused by the rupture of blood vessels [

3]. As a result, stroke can cause various problems, including plegia, language, cognition, and perception [

4]. In addition to these complications, dysphagia is a common complication [

5]. Dysphagia refers to difficulty swallowing and, on average, occurs in about 42-67% of stroke patients [

6], with about half of all patients developing it after an acute stroke [

7]. Stroke causes various symptoms depending on the type and area of the damaged blood vessel, and the middle cerebral artery (MCA), which is the most frequently damaged blood vessel, supplies blood to various areas of the brain, causing functional problems related to the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes [

5]. Therefore, in addition to dysphagia, different symptoms, such as plegia and neglect, may occur [

5]. Particularly, if an infarction occurs in the lateral medulla, it is called ‘lateral medullary syndrome’ or ‘Wallenberg’s syndrome’ [

8]. The lateral medulla contains the main nuclei of swallowing that trigger and control the swallowing reflex, so when it is damaged, dysphagia occurs at a higher rate than in other areas [

9]. Dysphagia, which causes difficulty swallowing, can lead to aspiration of food or saliva, which can increase the risk of complications, such as pneumonia [

7]. In addition, half of the people with dysphagia rely on a nasogastric tube (NGT) as an alternative to oral intake due to the persistence of symptoms [

10]. Dysphagia adversely affects stroke recovery by causing problems with activities of daily living (ADL), such as malnutrition and increased length of hospitalization [

7,

10], as well as decreased quality of life and depression arising from this dependency and fear of a poor prognosis [

11,

12]. Due to these various causes and symptoms, dysphagia is a crucial factor to consider in stroke patients [

13].

Various studies have been conducted using diffusion-weighted images (DWI) to investigate the causes of dysphagia [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. DWI was developed in the 1980s and is a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that uses the diffusive motion of water molecules to image fine structures in the brain (Lebihan et al., 2020). First, Lee et al. (2020) reported that bilateral lesions of the basal ganglia, corona radiata, and internal capsule were critical factors in the cause and severity of early dysphagia in 137 patients with acute ischemic stroke [

14]. Fandler et al. (2017) reported in a study of 332 patients with cerebellar infarction that dysphagia can occur in significant numbers in patients with cerebellar infarction and that additional damage to the pons or severe damage to white matter may increase the risk of dysphagia [

15]. Flowers et al. (2017), on the other hand, reported that the main predictors of dysphagia were medullary, insular, and pontine lesions in 160 patients with acute ischemic stroke [

16]. Wilmskoetter et al. (2019) found that in 68 patients with middle cerebral artery stroke, dysphagia symptoms were mainly seen in cortical regions, subcortical regions, and white matter tracts damage in the right hemisphere [

17]. Fandler et al. (2018) reported in 243 patients with small subcortical infarct (RSSI) that moderate-to-severe dysphagia in RSSI patients was primarily due to bilateral pyramidal tract damage or a combination of bilateral RSSI damage and contralateral vascular lesions. This ability of DWI to image different tissues in the brain has led to several reports on the location of dysphagia [

18].

Diffusion tensor tractography is a device that allows visualization of damaged brain neural tract connections and can measure various metrics such as fractional anisotropy (FA), tract volume (TV), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and mean diffusivity (MD) of neural tracts [

19]. FA is an indicator of the directionality of neural tracts and the alignment of their organizational structure [

20]. Next, TV is a measure of the total volume of neural fiber bundles and is used to assess the overall size of a particular neural tract [

21]. ADC is a diffusion metric that shows how diffuse a neural tract is, and MD is the mean diffusivity [

22]. When a neural tract is damaged, FA and TV values decrease while ADC and MD values increase [

21,

22]. Therefore, DTT has the main advantage of visualizing, quantifying, and evaluating the structural integrity, connectivity, and spatial organization of an entire neural tract using the above metrics [

19]. Furthermore, in viewing neural tract connections using DTT equipment, regions of interest (ROI) are established, representing specific areas of interest [

23]. Specifically, they can be divided into seed ROI and target ROI, where the seed ROI is the starting point of the tract analysis process and the target ROI is the final destination of the connections in the tract that started in the seed ROI [

24].

The importance of identifying the etiology of dysphagia symptoms and the effectiveness of interventions urged a review study to identify the etiology of dysphagia using various instruments [

25]. However, the review only focused on DWI and did not identify constructed connections and detailed indices, such as FA, TV, and MD [

25]. Hence, it is necessary to use DTT, which can visualize neural connections and quantify multiple visual images of neural connections as indices, to identify the neural tracts that cause dysphagia in detail.

Accordingly, this study aimed to review relevant literature on the identification of neural tracts leading to dysphagia after stroke using DTT, to help visualize and quantify structural connectivity between brain regions with metrics, such as FA, TV, and MD.

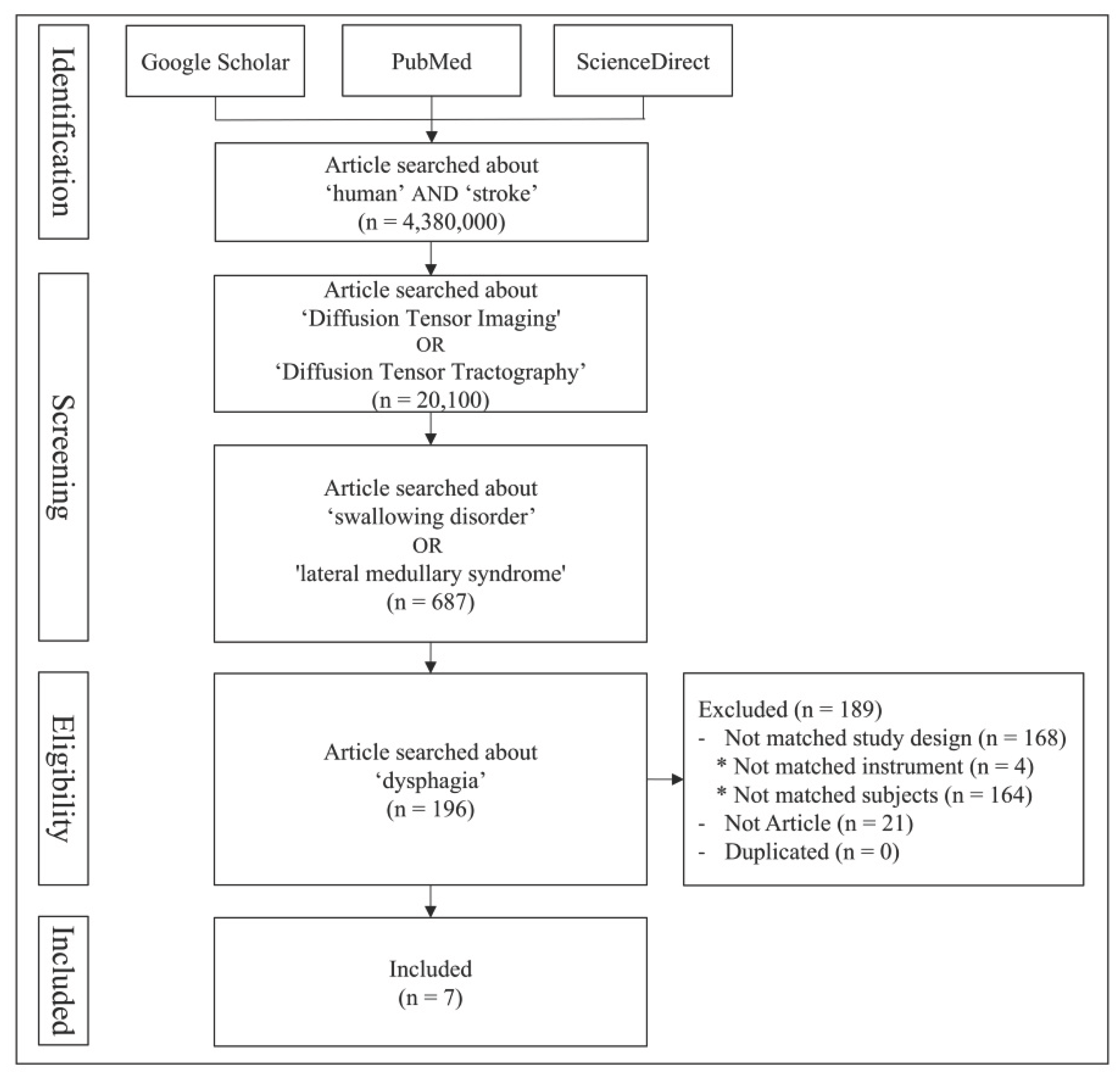

3. Results

Jang et al. (2017) studied the neural tract causing dysphagia in a stroke patient (n = 1, 59 years old, male, left middle cerebral artery infarction) using diffusion tensor tractography. The study subject was wearing a Levin tube due to severe dysphagia after a stroke [

26]. DTT was performed at 5 and 9 weeks post-stroke, and the results were compared to those of normal individuals of the same gender and age (control group, n = 3). The DTT results at week 5 revealed that the left CBT was not analyzed due to severe damage, and the right CBT was only marginally analyzed due to severe narrowing at the subcortical white matter level. However, the patient showed improvement in dysphagia at week 9, so the Levin tube was removed and the patient started to eat normally. In addition, the DTT at week 9 showed that the left CBT had not been reconstructed in the same way as it was at week 5, but the right CBT was smoothly reconstructed, extending into the cerebral cortex. Thus, CBT is significantly involved in the pathogenesis of dysphagia; particularly, the recovery of the right CBT is associated with the recovery of dysphagia symptoms, even though the left CBT was not reconstructed. Limitations of this study include the potential for false-negative results due to crossing fibers and partial volume effects imaged using DTT. Second, although the reconstruction of CBT was identified, the parameters of DTT, such as fractional anisotropy, tract volume, and mean diffusivity, were not specified. Finally, the mechanism by which dysphagia improved after restoration of unilateral CBT was not explained.

Yeo et al. (2018) used DTT in stroke patients (experimental group, n = 8, lateral medullary syndrome) and healthy individuals (control group, n = 10) to study the association between damage to the core vestibular pathway (connecting the Parieto-Insular Vestibular Cortex (PIVC) and vestibular nuclei) and symptoms of central vestibular disorder [

27]. The experimental group demonstrated symptoms of central vestibular disorder (vertigo [n = 7], dysphagia [n = 6], ataxia [n = 5], dysarthria [n = 3]). The DTT results for the core vestibular pathway were compared between the two groups. The results presented no significant difference between the two groups in FA and MD of the core vestibular pathway, but both the affected side and non-affected side of the experimental group significantly decreased in tract volume compared to the control group. The results confirm that damage to the core vestibular pathway is highly associated with dysphagia. Some limitations of the research include (1) the small number of subjects, making it difficult to generalize the results; (2) the tract volume of the fiber tract of the core vestibular pathway, which may have been underestimated or overestimated; (3) the contralateral vestibular pathway on the non-affected side that could not be reconstructed; (4) the vestibular nuclei area for seed regions of interest, which was too small to define accurately; and (5) the lack of explanation of the degree of reconstruction of the left and right tracts and the difference between moderate and sub-severe symptoms of central vestibular disorder.

Jang et al. (2020a) examined the prognostic value of CBT parameters (fractional anisotropy and tract volume) and its prediction of dysphagia using DTT in stroke patients (experimental group, n = 42, intracerebral hemorrhage) and normal individuals (control group, n = 22) [

28]. The experimental group was divided into: A group (n = 10): Removal of nasogastric tube in the acute stage (within 2 days after onset), B group (n = 27): NGT removal within 6 months after onset, and C group (n = 5): NGT removal more than 6 months after onset. DTT was taken within 6 weeks of onset and compared to the DTT results of the control group. Compared to the control group, group A had a significant decrease in FA values in the affected side (i.e., CBT only), and group B showed a significant decrease in both FA and TV values in the affected side. However, the C group showed a significant decrease in both FA and TV values of both sides of CBT. A moderate negative correlation (r = 0.430, p < 0.05) was also found, illustrating that the higher the TV value of the affected side CBT in the B group, the shorter the duration of NGT wearing. Another finding presented that damage to the CBT of both sides made it challenging to remove the NGT within 6 months and that recovery was possible within 6 months if only the CBT of the affected side was damaged. Consequently, the current study verified that the identification of CBT parameters (FA, TV) can help recognize the tract responsible for dysphagia in stroke patients and prognostic prediction for recovery. Some limitations of Jang et al.’s (2020a) study are as follows: (1) the small number of study subjects, affecting the generalizability of the results; (2) the presence of subjects with IVH in the experimental group, resulting in an imbalance in the homogeneity of the subjects in the experimental group; (3) the difference in the number of subjects in the two groups, leading to an imbalance in the number of subjects in each subgroup of the experimental group; (4) the mean diffusivity and apparent diffusion coefficient metrics of the neural tracts were not mentioned; and (5) there was no explanation of the mechanism by which dysphagia improved with unilateral CBT.

Jang et al. (2020b) studied the prognostic value of CBT parameters and its prediction of dysphagia symptoms using DTT in stroke patients (experimental group, n = 20, lateral medullary infarction) and normal individuals (control group, n = 20) [

29]. The experimental group comprised patients who had experienced or were currently wearing an NGT due to dysphagia post-infarction. The experimental group was divided into two subgroups: A group (n = 16): NGT removal within 6 months of onset and B group (n = 4): NGT removal more than 6 months after onset. DTT of both groups was taken within 6 weeks of onset and compared with the results of the control group. The results revealed that the FA values of CBT in the affected hemisphere were significantly lower in group B. Moreover, the TV values of CBT in both hemispheres were significantly reduced in both groups compared to the control group, although there was no significant difference between groups A and B. Furthermore, the damage was severe enough that the CBT on the affected side was not reconstructed in 3 out of 4 subjects in group B. This suggests that LMI-induced dysfunction in the affected hemisphere may be related to the lack of reconstruction. This study demonstrated that the extent and recovery of LMI-induced dysphagia are associated with CBT damage and confirmed that DTT can be used for the prognostic prediction of dysphagia from the early stages of damage. Limitations of this study are as follows: (1) the small number of subjects in this study, makes it challenging to generalize the findings; (2) the imbalance in the number of subjects in each subgroup of the experimental group; (3) the analysis of the underlying fiber architecture, which may not be complete in regions of fiber complexity and crossing; and (4) the MD and ADC values of the neural tracts were not mentioned.

Jang et al. (2020c) studied the association between the vestibulospinal tract and central vestibular disorder symptoms causing dysphagia using DTT in a stroke patient (n = 1, 56 years old, male, right lateral medullary syndrome due to right posterior inferior cerebellar artery infarction) [

30]. DTT was taken on average at 2 weeks post-onset and compared to the results of 6 normal individuals of similar age. The results showed no damage to the bilateral medial VST and left lateral VST of the experimental group and no significant differences in FA or MD from the control group. However, the right lateral VST of the experimental group was not reconstructed after damage to the extent that the FA and MD metrics was difficult to measure. Central vestibular disorder symptoms persisted at the 6-week post-injury assessment. This study demonstrated that central vestibular disorder symptoms in patients with lateral medullary syndrome due to PICA infarction resulted from lateral VST damage. The study’s limitations, which affected the generalizability of the results, are as follows: the case report study covered narratives specific to the study subjects; only a small number of subjects were involved in the study; the small size of the vestibular nuclei made it impossible to precisely position the ROI; the fiber tracts could be underestimated; dysphagia, one of the core symptoms of central vestibular disorder, was not discussed in detail; and the TV and ADC values of the nerve tracts were not specified.

Jang et al. (2020d) studied stroke patients (experimental group, n = 7, lateral medullary syndrome due to dorsolateral medullary infarction) and normal individuals (control group, n = 10) using DTT to compare parameters according to medial and lateral vestibulospinal tract damage and determine the association of central vestibular disorder with dysphagia [

31]. The experimental group presented with typical central vestibular disorders ([dysphagia: n = 6], [vertigo: n = 6], [ataxia: n = 4], [dysarthria: n = 3]). DTT was performed at an average of 2 weeks after onset, and FA, MD, and TV of the CST were measured together for comparative analysis of medial and lateral VST and motor function and compared with DTT results of 10 control subjects. The results showed that in the CST and medial VST, FA, MD, and TV in both sides were not significantly different from the control group, but in the lateral VST, FA values in the non-affected side were significantly reduced compared to the control group, and both FA and TV values in the affected side were significantly reduced compared to the control group. These findings suggest that metric analysis of lateral VST using DTT can help assess central vestibular sign symptoms such as dysphagia in patients with lateral medullary syndrome and in planning future interventions. Some limitations of this study are as follows: the small number of subjects in the study; the small size of the vestibular nuclei, which prevented the researchers from precisely positioning the ROI; the lack of data on long-term follow-up, the researchers may have underestimated or overestimated the fiber tracts of the VST, and the researchers could not reconstruct the full length of the lateral VST.

Wang et al. (2023) investigated the treatment effect of post-stroke dysphagia with repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) using DTT in stroke patients (n = 61). The FA of CBT of 61 subjects was measured using DTT [

32]. In addition, 31 subjects with high CBT integrity were divided into three groups and given the following rTMS treatments: 5 Hz rTMS (n = 11), 1 Hz rTMS (n = 10), and a control group (Sham rTMS (n = 10). Then, 30 participants with low CBT integrity were equally divided into three groups: 5 Hz rTMS (n = 10), 1 Hz rTMS (n = 10), and control (Sham rTMS, n = 10). For rTMS, the higher the number of Hz, the stronger the stimulation; for Sham rTMS, no current was delivered, but the same frequency, stimulation duration, and sound environment as 5 Hz was used. The Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study (VFSS), the Standardized Swallowing Assessment (SSA), Penetration Aspiration Scale (PAS), and Dysphagia Outcome Severity Scale (DOSS) were used to assess dysphagia. The results indicated that the high CBT integrity group showed a significant recovery of dysphagia symptoms at 5 Hz and 1 Hz compared to Sham, without significant difference between 5 Hz and 1 Hz. However, the low CBT integrity group showed recovery of dysphagia symptoms only at 5 Hz. Additionally, significant treatment effects on SSA, PAS, and DOSS were found in both high and low CBT integrity groups, implying that high-frequency rTMS intervention is a more effective intervention for the recovery of dysphagia symptoms due to severe CBT impairment. The paper’s limitations include the lack of long-term follow-up of dysphagia symptoms; the small number of studied subjects; the lack of explicit focus on addressing the association between CBT and dysphagia; and the use of only FA measures of CBT, excluding MD and TV.

4. Discussion

This study reviewed seven articles, focusing on the type of tracts that cause dysphagia in stroke patients using diffusion tensor tractography (

Table 1).

First, regarding the tracts involved in causing dysphagia, the corticobulbar tract(CBT) was found to be the most common among the four studies. Specifically, in the case of CBT, cases of dysphagia symptoms improved with the recovery of the right CBT alone, even when the left CBT was not recovered [

26,

28]. This outcome can be explained by the “bilateral cortical representation” of Broadbent’s law from previous studies [

33]. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that muscles involved in survival, such as breathing and swallowing, are controlled by the bilateral cerebral cortex so that damage to one side of the tract does not directly result in complete loss of function [

33,

34].

Another tract implicated in the development of dysphagia was the vestibulospinal tract, reported in two studies [

30,

31]. On the other hand, one study considered the core vestibular pathway as a factor [

27]. Injury to the VST has been associated with multiple symptoms of central vestibular disorders (e.g., vertigo, ataxia, aphasia), particularly showing a strong correlation with dysphagia in patients with lateral medullary syndrome [

27,

30,

31]. Similarly, damage to the CVP was also frequently associated with central vestibular disorders, including dysphagia [

27].

Specifically, in the reviewed DTT parameters, fractional anisotropy appeared as the most commonly reported [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], followed by tract volume [

28,

29,

31], and mean diffusivity [

27,

30,

31]. Furthermore, one study demonstrated the neural tract injury by comparing images directly with those of healthy controls, without employing specific parameters [

26]. Additionally, correlations between changes in these parameters and dysphagia severity were identified, with FA and TV values of the CBT and VST exhibiting a negative correlation, indicating that lower FA and TV values reflected greater tract damage. Moreover, certain studies went beyond identifying tracts responsible for dysphagia and evaluated prognostic predictions of dysphagia recovery, such as prolonged use of nasogastric tube correlated with the severity of neural tract injury [

28,

29].

Next, in terms of the study subjects, three studies included patients with lateral medullary syndrome due to stroke [

27,

30,

31], two studies examined patients with infarction [

26,

29], one study investigated patients with cerebral hemorrhage [

28], and one study involved stroke patients without differentiating infarction from hemorrhage or patients with complex brain injury. DTT imaging was typically performed within an average of 14 days after stroke onset, with all studies conducting initial imaging no later than six weeks post-onset.

Regarding the study designs, cohort studies were the most frequent, as reported in four papers [

27,

28,

29,

31], followed by two case studies [

26,

30], and one pilot study [

32]. Identified limitations across these studies included incomplete reporting of certain measurable parameters through DTT [

26,

29,

30,

32], the small sample size, limiting generalizability [

29,

30,

32], potential false-negative results in regions where neural fibers cross intricately due to technical limitations of DTT equipment [

29,

30,

32], absence of long-term follow-up assessments [

30,

32], and difficulties in accurately defining regions of interest due to the small size of certain neural nuclei [

30].

Nevertheless, this review identified major neural tracts responsible for dysphagia using DTT and further highlighted its potential for predicting dysphagia recovery outcomes. This paper provides valuable clinical insights to practitioners and is significant as the first DTT review specifically addressing dysphagia. Still, future studies that would address the aforementioned limitations to further enhance understanding of neural tracts involved in dysphagia are recommended.