Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

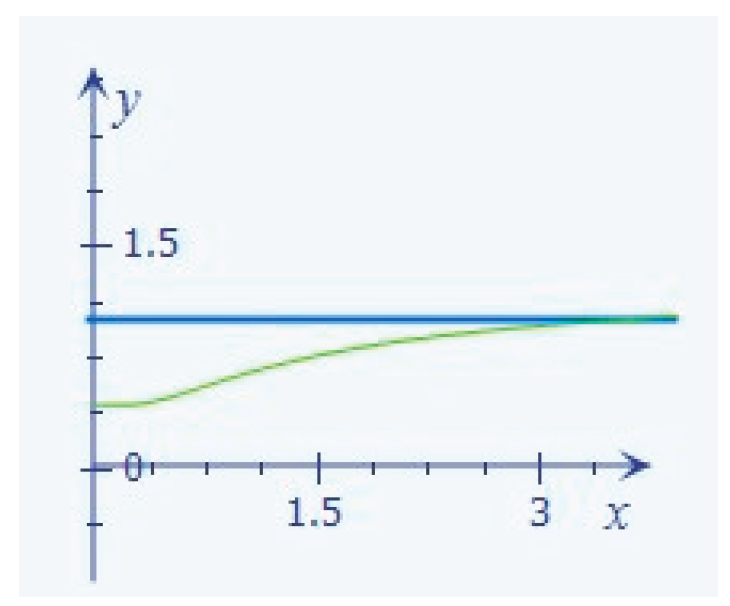

2. Sense of Productivity

3. Method

4. Results and Discussion

Results

Discussion

5. Conclusion

| 1 | See, for example, Bürgenmeier, B. (1992). The Meaning of Productivity. In Socio-Economics: An Interdisciplinary Approach: Ethics, Institutions, and Markets (pp. 129-152). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. |

References

- Ammons, D. N. (2004). Productivity barriers in the public sector. PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND PUBLIC POLICY-NEW YORK-, 107, 139-164.

- Bürgenmeier, B. (1992). The Meaning of Productivity. In Socio-Economics: An Interdisciplinary Approach: Ethics, Institutions, and Markets (pp. 129-152). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Chatterjee, S. (2025a). On the Interrelationship between Learning, Intellect, and Productivity. Intellect, and Productivity (July 03, 2025).

- Chatterjee, S. (2025b). Productivity and Productive Capital: Metaphysical Perspectives.

- Chatterjee, S., & Samanta, M. (2025). Noetic Capital and the Economics of Productivity.

- Coad, A., Pellegrino, G., & Savona, M. (2016). Barriers to innovation and firm productivity. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 25(3), 321-334. [CrossRef]

- Crespi, F., & Pianta, M. (2008). Demand and innovation in productivity growth. International Review of Applied Economics, 22(6), 655-672. [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P. (2002). Modern economics and its critics. Fact and fiction in economics: Models, realism and social construction, 57-89.

- Feldman, A. J. (2019). Power, labour power and productive force in Foucault’s reading of Capital. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 45(3), 307-333. [CrossRef]

- Fried, H. O., Schmidt, S. S., & Lovell, C. K. (Eds.). (1993). The measurement of productive efficiency: techniques and applications. Oxford university press.

- Huczynski, A. (2012). Management gurus. Routledge.

- Jackson, N., & Carter, P. (1998). Management Gurus: What are We to. Organization-Representation: Work and Organizations in Popular Culture, 149.

- Kessler, E. (2020). Wise leadership: A toolbox for sustainable success. Routledge.

- Koskela, L., & Kagioglou, M. (2005). On the metaphysics of production.

- Kumar, P. N. (2024). Significance of Productivity Concept. Productivity, 65(3), 325-331.

- Lopez-Cabrales, A., Valle, R., & Herrero, I. (2006). The contribution of core employees to organizational capabilities and efficiency. Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management, 45(1), 81-109. [CrossRef]

- Maraguat, E. (2019). Hegel on the Productivity of Action: Metaphysical Questions, Non-Metaphysical Answers, and Metaphysical Answers. Hegel Bulletin, 40(3), 425-443. [CrossRef]

- Panda, G. (2019). Employee competencies acting as an intermediary on measuring organizational productivity: a review perspective. International Journal of Mechanical and Production Engineering Research and Development (IJMPERD), 9(2), 195-202. [CrossRef]

- Remes, J., Mischke, J., & Krishnan, M. (2018). Solving the productivity puzzle: The role of demand and the promise of digitization. International Productivity Monitor, (35), 28-51.

- Reuten, G. (2004). Productive force and the degree of intensity of labour: Marx’s Concepts and Formalizations in the Middle Part of Capital I. In The Constitution of Capital: Essays on Volume I of Marx’s Capital (pp. 117-145). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2023). On productivism.

- Siebers, P. O., Aickelin, U., Battisti, G., Celia, H., Clegg, C., Fu, X., ... & Peixoto, A. (2008). Enhancing productivity: the role of management practices. Submitted to International Journal of Management Reviews, Forthcoming.

- Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity?. Journal of Economic literature, 49(2), 326-365.

- Witt, U. (2001). Learning to consume–A theory of wants and the growth of demand. Journal of evolutionary economics, 11(1), 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Zvorikine, A. A. (1962). Science as a direct productive force. Cahiers d'Histoire Mondiale. Journal of World History. Cuadernos de Historia Mundial, 7(1), 959.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).