1. Introduction

The history of nanotechnology dates to the early sixties of the 20th century when it was discovered that phospholipids when combined with water formed a sphere [

1]. Nanoparticles and nanomaterials are progressively being investigated as delivery vehicles with potential applications in medicine.

Biochemically nanoparticles, first termed liposomes, can be viewed as bilayer spheres formed and comprised of one side of each molecule being water soluble, while the opposite side is insoluble in water. Liposomes exhibit a broad size distribution, typically ranging from approximately 30 nanometers (nm) to several micrometers in diameter, depending on their method of preparation and intended application. Hence categorized as small (20-100 nm), large (100-1000 nm), or oversized (greater than 1000 nm) vesicles. The specific size can influence their behavior, particularly in drug delivery applications [

2] and represent versatile nanoplatforms for the enhanced transport of active natural compounds and pharmaceutical drugs in various matrices of biomedical and nanomedicine applications.

Nanotechnology comprises the science of bioengineering processes that leverage the manipulation of materials at the molecular scale for the elaboration and conversion of particulate matter into a physical state. This conversion produces nanoparticles of sizes of between 1 nm and 100 nm that can be reassembled into nano-systems with improved function [

3]. Nanoparticles hold significance promise to improve medical treatment specificity. It has been often posited that there is an extensive range in the doses administered of many drugs to produce a clinical efficacious result, given the pharmacological effects that have been observed in individual patients [

4]. The individual patient variation in dose requirement is sometimes reflected in the wide scatter in the steady state plasma concentration that follows the same oral dose of a drug given to any group of patients [

5].

Nanoparticles have been gaining prominence in drug delivery systems due to their capacity to enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. These carriers can be engineered for site-specific targeting, improved solubility and physicochemical stability of active pharmaceutical ingredients, and precise control over drug release kinetics. Such properties support the development of personalized treatment regimens with improved clinical outcomes [

3]. Nanotechnology has significantly transformed modern medicine, particularly in the development of advanced drug delivery systems utilizing both natural and synthetic compounds [

6]. These nanocarriers enable precise delivery of therapeutics, enhancing efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity. Due to their small size and tunable surface properties, many nanoparticles demonstrate enhanced pharmacokinetic behavior, including improved absorption, distribution, and retention. These characteristics enable selective targeting of specific cell types, depending on the particle’s composition and functionalization [

6]. Once internalized, nanoparticles can accumulate in subcellular compartments of lysosomes, mitochondria, or the nucleus, with capabilities of modulating intracellular processes. This biochemical ability underpins a favorable therapeutic potential in managing chronic diseases, including diabetes, cancer, and kidney disorders or the management of symptoms such as pain and nausea. Nanoparticles can facilitate precise intracellular drug delivery and minimizing off-target effects [

7].

Drug delivery can be achieved via various routes including for example intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), and oral administration, each with its advantages and disadvantages [

8]. IV drug delivery entails direct administration into the bloodstream via needle insertion into a blood vessel, offering the most rapid onset and complete bioavailability of all delivery routes. In contrast, intramuscular (IM) injection leverages the rich vascular supply of muscle tissue to facilitate systemic absorption. Despite showing efficacy, both IV and IM modalities require needle penetration, often associated with discomfort and reduced patient acceptability [

9].

Oral administration remains the most patient-friendly route, offering both practical and psychological advantages, a route that generally preferred by both patients and healthcare providers [

10,

11]. Consequently, up to 90% of pharmaceutical compounds available for human use are formulated for oral delivery [

11]. Oral delivery can significantly enhance patient adherence to treatment regimens, as it convenient, non-invasive and allows patients to self-administer the drug. Orally administered drugs may be intended to exert their therapeutic effect locally within the GIT or be absorbed through the intestinal epithelium into the systemic circulation to reach distant target sites (e.g., the heart). Despite having widespread clinical preference, the oral route poses significant pharmacological challenges due to the GIT inherent complexity [

12]. The oral-drug delivery complexity is subject to several factors, including the physiological variability of the GIT, enzymatic activity, pH fluctuations, and interactions with food and the intestinal microbiota [

13]. Xenobiotic (e.g., antibiotics) modulation by intestinal bacteria can have detrimental effects on the gut microbiota that can lead to adverse drug effects and gut dysbiosis by promoting inflammatory sequalae in the gut [

11].

The adoption of oro-buccal and or intranasal nanoparticle technology for the delivery of pharmaceutical drugs and or cannabinoids is a plausible posit that can overcome disadvantages of oral administration with first pass metabolism in the intestines.

2. The Gastrointestinal Tract (GIT), Cannabinoids and Pharmaceutical Drugs

2.1. The Intestinal Microbiome / Microbiota

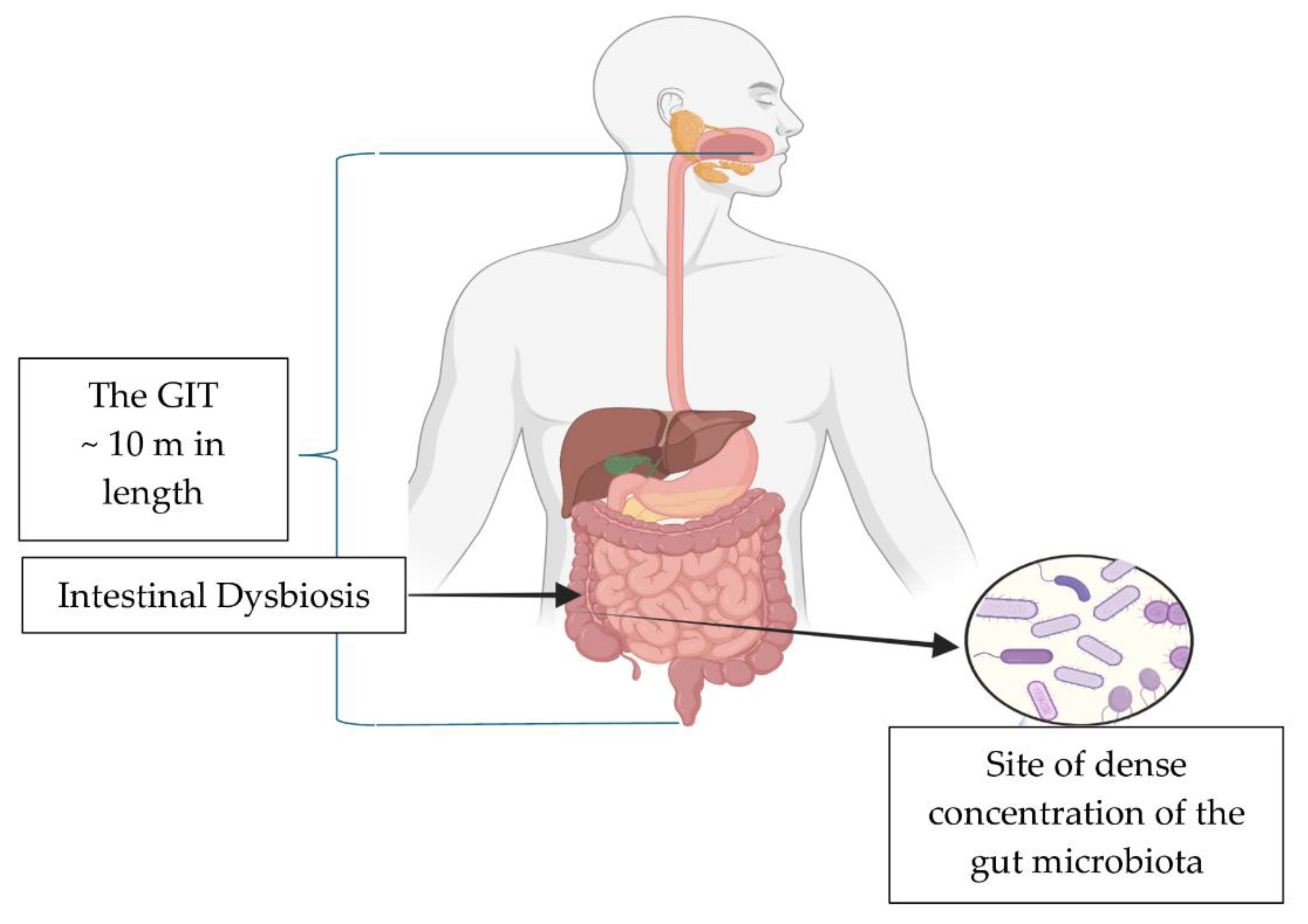

The GIT is approximately a 10-meter-long tube with an entry and exit [

14] (

Figure 1). The healthy gut is in a continuous state of equilibrium of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses. The microbiota in the intestines exerts a strong influence on fluidity in all the function that occur daily whether in the fed or fasted states[

15]. The microbiota symbiosis that exists with the host governs health and disease states[

15]. The combined microbiota -host symbiosis decisively directs and regulates the hematological structures (e.g., mucosal immunity) maintaining the equilibrium of the immune system. Moreover, the steady state also strengthens non-hematological structures (e.g., the intestinal epithelial barrier) by acting in concert to limit gut toxins/pathobionts translocation out of the gut lumen [

15,

16].

The adult human gut harbors a diverse microbial community composed of seven principal bacterial phyla namely

Firmicutes (including

Clostridium,

Lactobacillus, and

Enterococcus),

Bacteroidetes (e.g.,

Bacteroides),

Actinobacteria (e.g.,

Bifidobacterium),

Proteobacteria (e.g.,

Escherichia coli),

Fusobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and

Cyanobacteria. The microbiota plays a fundamental role in maintaining homeostasis, influencing digestion, immunity, and systemic health [

15]. Members of the

Firmicutes and

Bacteroidetes phyla are the dominant constituents of the human gut microbiota and have been implicated in promoting metabolic disturbances associated with obesity and colorectal cancer development [

17].

The cohort of bacteria that inhabit the intestines represents an organ unto itself that has important correlations for nutrient absorption, by metabolizing foods for its own energy needs and for synthesizing for the host, essential beneficial vitamins, minerals and amino acids for absorption and the detoxification / elimination of toxic food compounds produced [

18]. The microbiota cohort in the gut represents a fundamental component of human physiology, exerting significant influence on both health and disease. This complex ecosystem, comprising bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea and helminths that inhabit the GIT play a pivotal role in digestion, immune regulation, nutrient absorption, and the maintenance of mucosal integrity [

19].

The gut metabolites produced by the microbiota, particularly short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, play a pivotal role in modulating the endocannabinoid system (ECS). Fermentation processes of dietary fibers by gut bacteria that produce SCFAs have been shown to influence ECS signalling pathways both locally within the gut, and systemically. Through various interactions, SCFAs can modulate inflammation, gut permeability, and energy homeostasis, all of which are tightly regulated by the ECS. This crosstalk underscores a critical bidirectional relationship whereby microbial activity can influence endocannabinoid tone, while ECS signalling can, in turn, shape the composition and function of the gut microbiota [

20].

SCFAs, particularly butyrate, demonstrate potent anti-inflammatory properties within the GIT and display critical functions in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier. Butyrate serves as a primary energy source for colonocytes and promotes the expression of tight junction proteins, thereby enhancing gut barrier permeability and preventing translocation of pathogens and pro-inflammatory molecules into systemic circulation. SCFAs are produced by various microbiota resident members from the

Coprococcus,

Roseburia,

Facealibacterium, Bifidobacterium,

Lactobacillus,

Lachnospiraceae, Blautia, and

Oscillospira genera. It has been reported that butyrate can provide up to 70% of the energy requisite of intestinal epithelial cells [

21]. This high energy demand is imperative for the maintaining the gut epithelial cell tight-junction protein scaffold[

21]. Additionally, butyrate exerts immunomodulatory effects by inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDACs) through the induced production of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Activities that lead to the suppression of pro-inflammatory gene expression and the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs), further supporting immune homeostasis in the gut environment [

21].

2.2. GIT Dysbiosis

An underestimated factor of importance in influencing drug metabolism, absorption and efficacy is the intestinal resident microbiome [

22]. The intestinal bacterial cohort that inhabits the gut, can alter how drugs are processed, impacting efficacy [

23] and influencing potential side effects [

23]. This effect is progressed from the microbiota's elaboration of enzymes that metabolize orally administered drugs [

23]. The impact of the local gut biochemical activities on host drug-metabolizing enzymes, is central in drug and nutrient absorption and immune system modulation [

23].

Drug absorption is influenced by microbiota function. For example, tryptophan metabolites that gut bacteria elaborate are of critical importance for maintaining the fidelity of the intestinal barrier mucosal integrity and permeability functionality [

24]. Intestinal bacteria metabolizing tryptophan, an essential amino acid, gives rise to tryptophan bioactive molecules (e.g., indole and its derivatives) [

25]. Several intestinal bacterial species have been reported to metabolize tryptophan to indole byproducts, including species such as

Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron,

Proteus vulgaris and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

26,

27] and

Clostridium sporogenes [

28],. Importantly, tryptophan metabolites significantly influence the regulation of host mucosal immunity, actions that promote eubiosis (i.e., a balanced gut microbial cohort). Furthermore, gut bacterial metabolites can upregulate the expression of cannabinoid receptors (CB

1 and CB

2) as well as the enzymes (i.e., fatty acid amide hydrolase [FAAH] and monoacylglycerol lipase [MAGL]) that are involved in the synthesis and degradation turnover of endocannabinoids [

29], provoking chemical reactions that may support cannabinoid ligand binding influencing function and biological activity.

Dysbiosis of the intestinal refers to an imbalance in the composition and function of the gut microbiota [

30]. The semi-permeable single cell lining of the intestinal barrier is a structure that covers the gut and prevents pathobionts themselves and the potentially pathogenic molecules that they can elaborate (e.g., lipopolysaccharides) from translocating across the gut mucosa and into the systemic circulation that, if breached through the effects that ensue from intestinal dysbiosis, can progress local inflammatory responses and systemic infections [

18,

30,

31].

Dysbiosis involving groups of bacteria in the gut particularly imbalances favoring

Firmicutes over

Bacteroidetes, has been linked to increased energy harvesting from the diet and pro-inflammatory states that may contribute to disease states [

30]. Hence the intestinal microbiota is influenced by a complex interplay of exogenous and endogenous factors [

30]. The influence exerted can produce effects that range from transient shifts to enduring alterations in intestinal microbial composition of gut species such as for example decreased abundance of

F. prausnitzii (i.e., exhibiting anti-inflammatory actions) with increased abundance of

C difficile (e.g., exhibiting pro-inflammatory activities

) with outcomes that span the spectrum from benign to pathogenic respectively [

32,

33].

Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that variations in specific gut bacterial families, including

Peptostreptococcaceae,

Veillonellaceae, and

Akkermansiaceae, can influence the synthesis and degradation of endogenous cannabinoids. These microbial shifts may affect the levels and activity of key endocannabinoid compounds such as anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), thereby altering signaling through cannabinoid receptors in both peripheral and central tissues. This gut microbiota–endocannabinoid interaction is thought to play a role in regulating host metabolic processes, immune responses, and even mood and behavior [

34]. Hence intestinal dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, can disrupt the ECS, potentially impacting cannabinoid signaling, cannabinoid efficacy and overall health.

Physiological conditions encountered in the GIT such as food effects, hormones, gastric pH,

emptying time, and

intestinal transit time vary widely across individuals and populations [

35]. F

luid composition and

enzymatic activity in the small intestine and colon also influencing drug dissolution and absorption. These factors in conjunction with the intestinal cohort of bacteria can metabolize drugs before absorption, contributing to drug bioavailability and with gut dysbiosis a further contributor to drug absorption and bioavailability [

36]. What is critical is the transit time taken to pass through specific locations (e.g., stomach, small bowel, large bowel) of the GIT. Time to transit the GIT can affect drug dosage, especially for pharmaceuticals that are absorbed in specific regions or have region-specific actions (e.g., small bowel) [

36]. Transit through the small intestine can range from 2–8 hours with individual variations, whereas transit through the large bowel can vary between 6–80 hours whether in the fasted or fed state [

35].

3. Medicinal Cannabis

3.1. Medicinal Cannabis for Nausea

Despite advancements in anti-emetic pharmacotherapy and associated nausea, that has included the development of serotonin 5-HT3 and neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonists, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) remains a significant clinical challenge. As so does anticipatory nausea and vomiting in patients expecting to undergo chemotherapeutic treatments [

37]. This adverse effect not only impairs patients’ ability to complete chemotherapy regimens but also ranks among the most distressing complications of cancer treatment. CINV has been associated with a decline in quality of life, as well as deterioration in both physical and cognitive functioning, which may ultimately impact a patient’s willingness to continue therapy.

Cannabinoids, known for their wide-ranging physiological effects on the nervous, immune, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal systems, have been proposed as alternative and potential useful therapeutic agents for the treatment of nausea and vomiting [

38]. An early systematic review and meta-analysis examining the efficacy of synthetic cannabinoids, such as dronabinol, nabilone, and levonantradol, for CINV included 30 clinical studies, some of which compared these agents with placebo, while others used conventional anti-emetics as comparators [

39]. Although limitations related to small sample sizes and heterogeneity in study designs prevent definitive conclusions, available data suggest that dronabinol may be more effective as an acute anti-emetic than some standard anti-emetic therapies.

A small randomized, double-blind study also reported that nabiximols (a standardized cannabis extract, containing tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol as its primary active components), when used as an adjunct to standard anti-emetic regimens, demonstrated efficacy in managing CINV [

40]. Anecdotally, many cancer patients have expressed a preference for smoked cannabis over synthetic cannabinoids, citing superior anti-emetic effects [

41]. However, this observation lacks support from controlled clinical trials. Consequently, cannabinoid therapies are not routinely integrated into oncology protocols, in part due to the absence of standardized formulations, defined dosing strategies, and comprehensive data on patient tolerability in this context. Nevertheless cannabinoids have a potential major role in managing an array of gastrointestinal conditions [

29] if delivered in other modalities that avoid the extensive first pass metabolism that cannabinoids experience when absorbed though the GIT.

3.2. Medicinal Cannabis for Pain

Relief from chronic pain either from cancer or non-cancer related diseases is a commonly cited by patients who express a desire to administer medicinal cannabis [

42,

43]. An extensive meta-analytic review of the literature consisting of 43 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reported a feasible posit for the administration of medicinal cannabis-based-medicines to effectively improve chronic pain treatment and primarily for neuropathic pain [

44]. Additional reports have postulated that cannabinoid-based pharmacotherapies may serve as effective replacement/adjunctive analgesic options [

45].

Neuropathic pain has been the most common form of pain investigated with the administration of medicinal cannabis products to induce an analgesic effect. Investigations have reported that low dose Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ

9-THC) (1.29%) as vaporized cannabis was superior for relieving central or peripheral neuropathic pain, that had been shown to be resistant to standard treatments when compared to placebo [

46]. Additional studies that engaged the oral / oromucosal routes for medicinal cannabis administration often as a crude herbal or dry leaf cannabis extracts, or as synthetic versions of THC (e.g., dronabinol, nabilone), or as plant-derived extracts of THC/CBD (i.e., oromucosal spray (Nabiximols) formulations have shown limited efficacy in chronic neuropathic pain [

43]. When all medicinal cannabis-based-medicines were pooled they were better than placebo in reducing problems associated with sleep disturbances and concomitantly improved psychological distress and health related quality of life [

43]. Medicinal cannabis may also be effective for other types of pain (e.g., nociceptive pain, nociplastic pain). Clinical studies administering smoked cannabis extracts in patients diagnosed with postsurgical or post-traumatic pain [

47] and in those with painful human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neuropathy [

48,

49,

50], have all reported efficacy over placebo the relief of pain, with good tolerability to the medicinal cannabis used [

50].

Although, the effectiveness of medicinal cannabis for chronic pain has been established [

51], all five previous clinical trials of medicinal cannabis for cancer pain (as reviewed by Boland and colleagues [

52]) have failed to reach the efficacy endpoint. Oral administration of cannabis-based medicines with gastrointestinal absorption leads to highly variable systemic concentrations of pharmacologically active constituents leading to slow and erratic an onset of action for analgesic use [

53]. The frequent dosing required of inhaled cannabis for a maintenance analgesic effect given that there is reported a half-life of less than 20 minutes [

53,

54]. Furthermore, the high THC blood concentration (20- to 30-fold higher C

max) after inhalation administration is associated with treatment limiting acute adverse effects and possible long-term respiratory system damage from toxic chemicals associated with smoking or vaporizing with a medicinal cannabis product [

53] (high temperatures involved with vaporized cannabis can oxidize the medicine and excipients) [

55].

Oral and inhaled administration routes for medicinal cannabis extracts presents a clinical picture that unsatisfactory for the management of pain and this has led to additional proposed routes of administration such as transdermal, transmucosal and intranasal modes of delivery[

56]. Notwithstanding due to their lipophilic nature, cannabinoids show promise as highly regulated prescribed medicines [

56] for continued investigations through the implementation of nanoparticle delivery technologies.

4. Nanotechnology for Effective Cannabinoid and Pharmaceutical Drug Delivery

The implementation of nanotechnologies has transformed innovations in medicine, specifically in diagnostic methods, imaging and importantly in pharmaceutical drug delivery [

57]. Several platforms have been developed to deliver medicines via alternative ways to the oral–GIT route [

58,

59]. The following sections outline examples of nanotechnologies developed specifically as platforms for the delivery of pharmaceutical medicines and for medicinal cannabis molecules (

Table 1).

4.1. Micelles

Micelles are nanoscale aggregates composed of amphiphilic surfactant molecules, typically including lipids, that self-assemble under aqueous conditions. These structures form spherical vesicles characterized by a hydrophilic outer monolayer and a hydrophobic core, enabling the encapsulation of hydrophobic therapeutic agents. The amphiphilic nature of micelles significantly enhances the aqueous solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs, thereby improving their bioavailability. Micelles can typically range in diameter from 10 to 100 nm. Owing to their unique physicochemical properties, micelles have been extensively utilized as drug delivery systems with therapeutic applications [

59].

The continued development of high-quality medicinal cannabis plant extracts and synthetic cannabis formulations [

68,

69] such as

Nabiximols (Sativex® a cannabis extract with equimolar THC and CBD developed by GW Pharmaceuticals ) have been granted approvals (e.g., FDA) for use in multiple-sclerosis-associated inflammatory spasticity in multiple jurisdictions. The oromucosal mouth spray using 50% ethanol delivers with each 100 µL actuation 2.7 mg THC) and 2.5 mg (CBD from

Cannabis sativa L). Furthermore, an additional formulation of an oral CBD solution

Epidyolex® (also from GW Pharmaceuticals, subsequently acquired by Jazz Pharmaceuticals in 2021), the FDA labelled orphan drug, has also been approved and indicated for treatment of seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome in both adults and paediatric patients, in the latter being older than two years of age. Regulatory agencies continue to cite that important clinical requisite continues to be that clinical studies must present patient data with correct and accurate standardized doses that were delivered to achieve optimal therapeutic efficacy [

70].

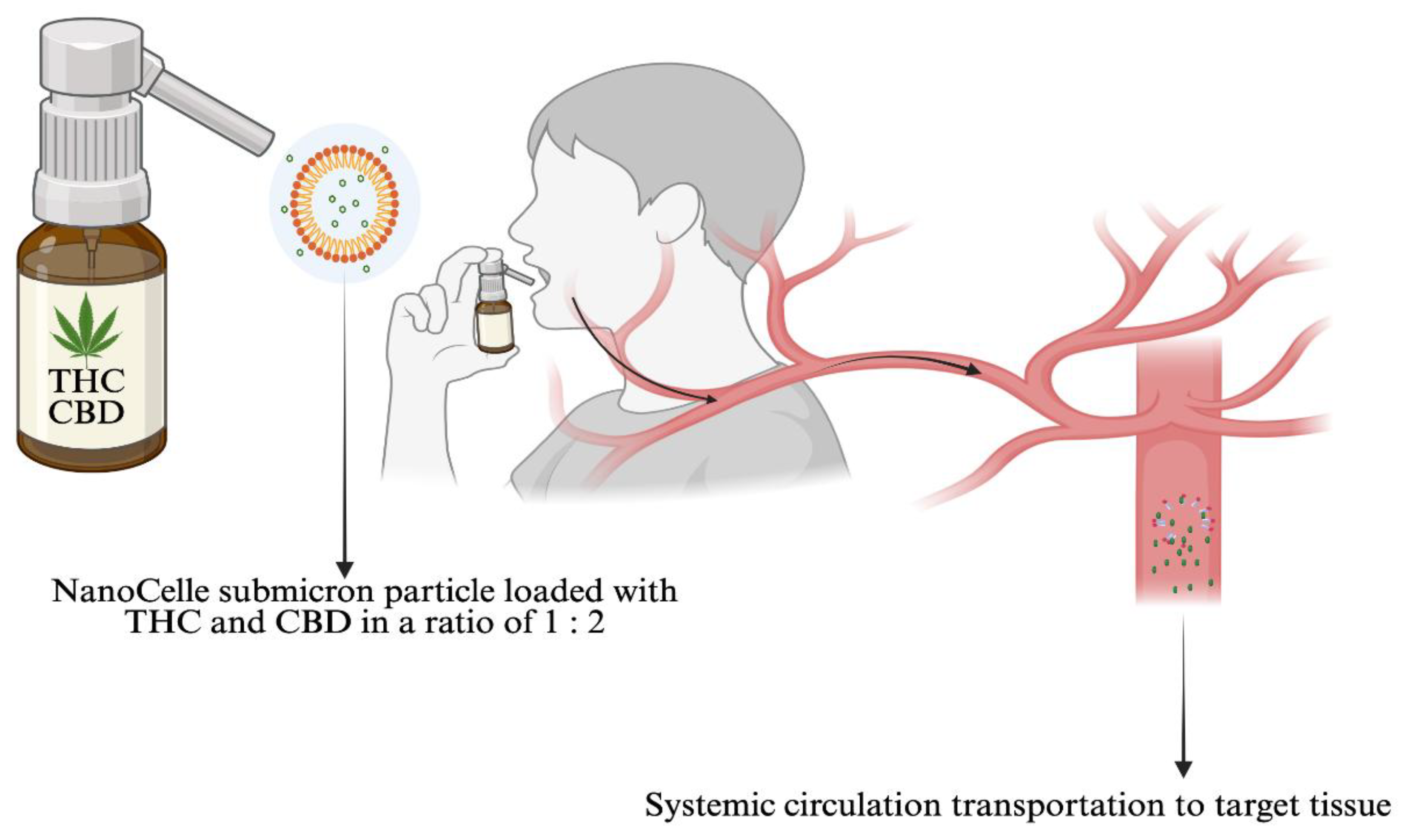

NanoCelle

TM is an innovative submicron particle delivery platform for oral mucous membrane absorption of small lipid soluble molecules such as THC and CBD [

71] or other pharmaceutical medicines that adheres to the chemical properties attributed to micelles. NanoCelle™ is a self-assembled, micellized nanoparticle drug delivery system designed for administration via the oro-buccal mucosa [

59]. Comprising a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic shell, NanoCelle™ particles facilitate passive diffusion of small molecules, such as vitamins (e.g., B12) across the oral mucosal membrane [

72] (

Figure 2). The technology has been extended to deliver cannabinoids [

73,

74], and early clinical trials have demonstrated a favourable safety profile and consistent pharmacokinetics [

71].

Micellar nanoparticles have also been developed for drug administration [

3]. The intravenous injection of a micellar containing paclitaxel was FDA approved for the treatment of several cancers including breast, non-small cell lung, pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancers [

60]. Recent advances in micellar nanoparticles have been posited suitable for cardiovascular targets of diagnosis and treamtments [

75]. In addition nanotechnology-based drug delivery platforms are being developed for the treatment of erectile dysfunction [

76].

Micellar nanoparticles elaborated produce clear, stable aqueous solutions of relatively water insoluble drug components without altering their chemical structures. It provides flexibility that allows the development of nanoparticle aqueous formulations of oro-mucosal, nasal, ocular, and transdermal products without the use of alcohol or first pass passage and metabolism through the GIT.

4.2. Liposomes

Liposomes are spherical vesicles composed of lipid bilayers, with particle sizes typically ranging from 30 nm to several micronmeters. They possess the unique capability to encapsulate both hydrophilic therapeutic agents, within their aqueous core, and hydrophobic agents, within the lipid bilayer structure. Due to their structural versatility, liposomes can be surface modified with polymers, antibodies, and proteins, enabling the incorporation of macromolecular therapeutics such as nucleic acids and crystalline metals [

3]. A commonly cited example is poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-ylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil®), listed as the first FDA-approved nanomedicine. The administration of this approved liposomal drug was employed in the treatment of breast cancer, enhancing drug accumulation within malignant effusions while avoiding an increase in systemic dosage. Notwithstanding, liposomes with dedicated use as drug delivery systems, can sometimes trigger an adverse and severe immune response such as complement activation-related pseudoallergy (CARPA) [

77,

78]. This reaction, characterized by hypersensitivity symptoms, is not a true allergic reaction that is mediated by IgE antibodies is an immune response mediated by the complement system.

Numerous nanodrugs have been approved by the FDA for clinical applications [

3]. Examples include pharmaceuticals for intravenous injections (e.g., amphotericin B) [

79], intramuscular / intrathecal / subcutaneous injections (e.g., daunorubicin) [

80] and specific for subcutaneous injections (e.g., Pegylated IFN-beta-1a) [

60].

4.3. Dendrimers

The size (i.e., less than 100 nm) and structure of dendrimers exhibits branched three-dimensional structure of repeating units extend from a centric core and comprised of peripheral functional groups [

57]. Dendrimers encapsulte therapeutic agents as other nanoparticle structures do, within the interior space of the formed dendrimers. Moreover the therapeutic agents can be attached to surface groups, making dendrimers highly bioavailable and decomposable. Chemical conjugates of dendrimers have been shown to exhibit enhanced antimicrobial, antiprion and antiviral properties when elaborated to encapsulte peptides or saccharides, showing improved solubility and stability on absorption of the therapeutic drugs [

81].

Dendrimer based drug delivery formulations are also under investigations with poly(amidoamine) and proton pump inhibitor dendrimers conjugated with drugs like methotrexate, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin for cancer therapy, and the use of VivaGel™ as a vaginal microbicide [

82].

5. Discussion

The nanotechnology revolution has profoundly influenced nearly every sector of modern society, offering innovative solutions that are better engineered, safer, more sustainable, long-lasting, and increasingly efficacious for the delivery of medicines.

The integration of nanomaterials into products generally occurs via two main approaches. Firstly, as nanoparticles that are incorporated into existing materials to enhance composite performance through the unique physicochemical properties of nanoscale additives. Secondly, as direct use of nanomaterials, such as nanoparticles or nanocrystals to construct novel, high-performance devices [

3]. These scientific advancements have the potential to redefine the capabilities of medical and industrial applications and are shaping the future of technology especially in the medical delivery of medicines for enhanced safety and efficacy of medical treatments.

We have recently shown that intestinal dysbiosis can significantly affect the absorption of cannabinoids (e.g., cannabidiol [CDB]) [

83]. CBD is poorly water soluble, and ingestion via the gut provides poor absorption [

84], and most of the CBD that is absorbed undergoes first-pass metabolism, resulting in a very low bioavailability of about 6% [

84]. Systemic exposure to CBD is increased four-fold by ingestion with a high-fat meal [

86] and five-fold with severe hepatic impairment [

85]. The physiology of the intestines is subject to increased absorption with a high-fat meal because of the formation of bile salt micelles which are naturally formed in the intestines with the action of bacteria admixed with a high fat meal or orally delivered medicinal cannabis medicines (e.g., oil- based formulation CBD) [

83]. Hence the largely natural formed micelles can transport CBD molecules from the intestinal epithelial cells across to the portal/systemic circulation [

83]. Notwithstanding products containing CBD for administration as sublingual oil-based drops still will result in first-pass metabolites of CBD that are ineffective, which indicates that mucous membrane absorption is inefficient [

86]. A proposed alternative is inhaling CBD by smoking or vaping that is known to provide a rapid route of CBD administration, reflecting a time to-peak-plasma-concentration of less than 5 minutes and a bioavailability of 31% [

87]. However, it is accepted that the highest level from CBD inhalation that is achieved was reported associated with increased adverse effects, and the high temperatures required to inhale the cannabinoids increases the likelihood of toxic oxidation products produced and inhaled [

86] by the lungs [

53]. Hence it is feasible to postulate with the current understanding of nanotechnologies that oral mucous membrane absorption could be improved by mimicking the carriage of CBD in natural intestinal micelles. Formulating CBD in synthetic nanoparticle matrices and delivering a proposed drug or the cannabinoid CDB pre-formed as a synthetic nanoparticle across the oro-buccal mucous membrane instead of the intestinal mucous membrane, avoids first pass metabolism in the gut and enhance efficacy [

74].

Nanomedicine and nanocarrier-linked medical approaches are in a rapid flux of development through the science that leverages the biomolecular nanoscale range. These contributions to site-specific delivery of medicines in a controlled manner has given rise to considerable research interest prominent to their potential to enhance bioavailability, decrease adverse side effects, and critically important the avoidance of first-pass metabolism in the intestines. This is especially pertinent to the delivery of cannabinoids and pharmaceutical medicines though the oral-gut route that limits absorption. Therefore, any novel approach that delivers cannabinoids and pharmaceutical medicines via an oral-buccal delivered water-soluble matrix has been shown by a modelling study to provide enhanced bioavailability [

71]. Technologies that provide evidence to support the application of innovative drug delivery platforms (e.g., micellar, dendrimers) to overcome limitations associated with cannabinoid administration via the oral-gut route provide significant credibility for therapeutic use.

6. Conclusions

Bypassing first pass metabolism in the gut is a fundamental and important characteristic of nanomedicines. It is hence possible to elaborate nanoparticles that are clear solutions, in a stable aqueous matrix. Producing relatively insoluble drug components without altering their chemical structures is an important feature of nanomedicines drug delivery platforms. These nanomedicines provide flexibility that allows the development of nanoparticle aqueous formulations of oro-mucosal, nasal, ocular, and transdermal products without the use of alcohol for enhanced delivery bypassing first pass passage and metabolism through the GIT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.V; writing—original draft preparation, L.V..; writing—review and editing, J.D.H.; E.H.; D.R.; S,H. All authors read and agreed to the publish the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

L.V.; J.D.H.; D.R.; S.H. declare having a conflict of interest with nanoparticle research and publications. There were no funders involved in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the manuscript.

References

- Sharma VK, and Agrawal MK. A Historical Perspective of Liposomes-a Bio Nanomaterial. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 45, 2963–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, D. , and M. A. Kiselev. Methods of Liposomes Preparation: Formation and Control Factors of Versatile Nanocarriers for Biomedical and Nanomedicine Application. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A., A. R. Z. Almotairy, H. Henidi, O. Y. Alshehri, and M. S. Aldughaim. Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of the Implication of Nanoparticles' Physicochemical Properties on Responses in Biological Systems. Polymers (Basel).

- Mitchell, M. J., M. M. Billingsley, R. M. Haley, M. E. Wechsler, N. A. Peppas, and R. Langer. Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 101–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R. L. Drug Absorption in Gastrointestinal Disease with Particular Reference to Malabsorption Syndromes. Clin Pharmacokinet 1977, 2, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S. , and S. Mitragotri. Challenges Associated with Penetration of Nanoparticles across Cell and Tissue Barriers: A Review of Current Status and Future Prospects. Nano Today 2014, 9, 223–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, S. , and F. Zuhair. Advancing Nanomedicine through Electron Microscopy: Insights into Nanoparticle Cellular Interactions and Biomedical Applications. Int J Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 2847–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homayun, B., X. Lin, and H. J. Choi. Challenges and Recent Progress in Oral Drug Delivery Systems for Biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Rodger, M. A. , and L. King. Drawing up and Administering Intramuscular Injections: A Review of the Literature. J Adv Nurs 2000, 31, 574–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, M. S., M. Kazi, M. A. Alsenaidy, and M. Z. Ahmad. Advances in Oral Drug Delivery. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 618411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiardes, S. , and C. Christodoulou. Orally Administered Drugs and Their Complicated Relationship with Our Gastrointestinal Tract. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Vinarov, Z., M. Abdallah, J. A. G. Agundez, K. Allegaert, A. W. Basit, M. Braeckmans, J. Ceulemans, M. Corsetti, B. T. Griffin, M. Grimm, D. Keszthelyi, M. Koziolek, C. M. Madla, C. Matthys, L. E. McCoubrey, A. Mitra, C. Reppas, J. Stappaerts, N. Steenackers, N. L. Trevaskis, T. Vanuytsel, M. Vertzoni, W. Weitschies, C. Wilson, and P. Augustijns. Impact of Gastrointestinal Tract Variability on Oral Drug Absorption and Pharmacokinetics: An Ungap Review. Eur J Pharm Sci 2021, 162, 105812. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., H. Jia, X. Cai, H. Zhong, Q. Feng, S. Sunagawa, M. Arumugam, J. R. Kultima, E. Prifti, T. Nielsen, A. S. Juncker, C. Manichanh, B. Chen, W. Zhang, F. Levenez, J. Wang, X. Xu, L. Xiao, S. Liang, D. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Chen, H. Zhao, J. Y. Al-Aama, S. Edris, H. Yang, J. Wang, T. Hansen, H. B. Nielsen, S. Brunak, K. Kristiansen, F. Guarner, O. Pedersen, J. Doré, S. D. Ehrlich, P. Bork, and J. Wang. An Integrated Catalog of Reference Genes in the Human Gut Microbiome. Nat Biotechnol 2014, 32, 834–41. [Google Scholar]

- Azzouz LL, and Sharma S. Physiology, Large Intestine. In StatPearls Publishing. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Bäckhed, F., R. E. Ley, J. L. Sonnenburg, D. A. Peterson, and J. I. Gordon. Host-Bacterial Mutualism in the Human Intestine. Science 2005, 307, 1915–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasaly, N., P. de Vos, and M. A. Hermoso. Impact of Bacterial Metabolites on Gut Barrier Function and Host Immunity: A Focus on Bacterial Metabolism and Its Relevance for Intestinal Inflammation. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 658354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K., H. Geng, C. Ye, and J. Liu. Dysbiotic Alteration in the Fecal Microbiota of Patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e0429123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecher, B. The Roles of Inflammation, Nutrient Availability and the Commensal Microbiota in Enteric Pathogen Infection. Microbiol Spectr 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, W. M., H. Tilg, M. Van Hul, and P. D. Cani. Gut Microbiome and Health: Mechanistic Insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P. D. , and C. Knauf. How Gut Microbes Talk to Organs: The Role of Endocrine and Nervous Routes. Mol Metab 2016, 5, 743–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L. M. T. How Important Are Fatty Acids in Human Health and Can They Be Used in Treating Diseases? Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2420765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, E. F., C. G. Gahan, S. A. Joyce, and B. T. Griffin. The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Drug Metabolism and Clinical Outcome. Yale J Biol Med 2016, 89, 375–82. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H., J. He, and W. Jia. The Influence of Gut Microbiota on Drug Metabolism and Toxicity. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2016, 12, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., L. Vitetta, J. D. Henson, and S. Hall. Intestinal Dysbiosis, the Tryptophan Pathway and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int J Tryptophan Res 2022, 15, 11786469211070533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Modulation of Immunity by Tryptophan Microbial Metabolites. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1209613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, Y., S. Jie, D. R. Linden, S. Ghatak, R. A. T. Mars, B. B. Williams, M. Pu, J. L. Sonnenburg, M. A. Fischbach, G. Farrugia, L. Sha, and P. C. Kashyap. Bacterially Derived Tryptamine Increases Mucus Release by Activating a Host Receptor in a Mouse Model of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. iScience 2020, 23, 101798. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotti, P., B. Hennart, C. Thieffry, G. Jausions, E. Faure, T. Grandjean, M. Thepaut, R. Dessein, D. Allorge, B. P. Guery, K. Faure, E. Kipnis, B. Toussaint, and A. Le Gouellec. Tryptophan Catabolism in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Potential for Inter-Kingdom Relationship. BMC Microbiol 2016, 16, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, D., M. H. Spitzer, W. Van Treuren, B. D. Merrill, A. J. Hryckowian, S. K. Higginbottom, A. Le, T. M. Cowan, G. P. Nolan, M. A. Fischbach, and J. L. Sonnenburg. A Gut Bacterial Pathway Metabolizes Aromatic Amino Acids into Nine Circulating Metabolites. Nature 2017, 551, 648–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z., D. Baik, and R. Schey. The Role of Cannabinoids in Regulation of Nausea and Vomiting, and Visceral Pain. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2015, 17, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G. A. , and T. Hennet. Mechanisms and Consequences of Intestinal Dysbiosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017, 74, 2959–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., J. Lyu, and S. Wang. The Role of Intestinal Microbes on Intestinal Barrier Function and Host Immunity from a Metabolite Perspective. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1277102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGruttola, A. K., D. Low, A. Mizoguchi, and E. Mizoguchi. Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016, 22, 1137–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak, M. Górna, D. Woźniak, J. Przysławski, and S. Drzymała-Czyż. Association between Gut Dysbiosis and the Occurrence of Sibo, Libo, Sifo and Imo. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castonguay-Paradis, S., S. Lacroix, G. Rochefort, L. Parent, J. Perron, C. Martin, B. Lamarche, F. Raymond, N. Flamand, V. Di Marzo, and A. Veilleux. Dietary Fatty Acid Intake and Gut Microbiota Determine Circulating Endocannabinoidome Signaling Beyond the Effect of Body Fat. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 15975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, N., G. Falony, L. O. Dragsted, T. R. Licht, J. Raes, and H. M. Roager. Advancing Human Gut Microbiota Research by Considering Gut Transit Time. Gut 2023, 72, 180–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugihara, M., S. Takeuchi, M. Sugita, K. Higaki, M. Kataoka, and S. Yamashita. Analysis of Intra- and Intersubject Variability in Oral Drug Absorption in Human Bioequivalence Studies of 113 Generic Products. Mol Pharm 2015, 12, 4405–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, D., V. Prasanna, A. Firdous, and S. Thakur. A Systemic Review on Chemotherapy Induced Nausea and Vomiting- Risk and Clinical Management with Alternative Therapies. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2025, 44, 100938. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, I. M., K. Bohlke, D. I. Abrams, H. Anderson, L. G. Balneaves, G. Bar-Sela, D. W. Bowles, P. R. Chai, A. Damani, A. Gupta, S. Hallmeyer, I. M. Subbiah, C. Twelves, M. S. Wallace, and E. J. Roeland. Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Adults with Cancer: Asco Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2024, 42, 1575–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado Rocha, F. C., S. C. Stéfano, R. De Cássia Haiek, L. M. Rosa Oliveira, and D. X. Da Silveira. Therapeutic Use of Cannabis Sativa on Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting among Cancer Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2008, 17, 431–43. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, M., E. Pérez, S. Abanades, X. Vidal, C. Saura, M. Majem, E. Arriola, M. Rabanal, A. Pastor, M. Farré, N. Rams, J. R. Laporte, and D. Capellà. Preliminary Efficacy and Safety of an Oromucosal Standardized Cannabis Extract in Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010, 70, 656–63. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, T., D. J. Levinthal, B. U. K. Li, S. E. Tarbell, K. A. Adams, R. M. Issenman, I. Sarosiek, S. S. Jaradeh, R. N. Sharaf, S. Sultan, C. D. Stave, A. A. Monte, and W. L. Hasler. Role of Chronic Cannabis Use: Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Vs Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 31 Suppl 2, no. Suppl 2019, 2, e13606. [Google Scholar]

- Boehnke, K. F., S. Gangopadhyay, D. J. Clauw, and R. L. Haffajee. Qualifying Conditions of Medical Cannabis License Holders in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019, 38, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucke, M., T. Phillips, L. Radbruch, F. Petzke, and W. Hauser. Cannabis-Based Medicines for Chronic Neuropathic Pain in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018, 3, Cd012182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aviram, J. , and G. Samuelly-Leichtag. Efficacy of Cannabis-Based Medicines for Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Physician 2017, 20, E755–e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanes, J. A., Z. E. McKinnell, M. A. Reid, J. N. Busler, J. S. Michel, M. M. Pangelinan, M. T. Sutherland, J. W. Younger, R. Gonzalez, and J. L. Robinson. Effects of Cannabinoid Administration for Pain: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2019, 27, 370–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilsey, B., T. Marcotte, R. Deutsch, B. Gouaux, S. Sakai, and H. Donaghe. Low-Dose Vaporized Cannabis Significantly Improves Neuropathic Pain. J Pain 2013, 14, 136–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, M. A., T. Wang, S. Shapiro, A. Robinson, T. Ducruet, T. Huynh, A. Gamsa, G. J. Bennett, and J. P. Collet. Smoked Cannabis for Chronic Neuropathic Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cmaj 2010, 182, E694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R. J., W. Toperoff, F. Vaida, G. van den Brande, J. Gonzales, B. Gouaux, H. Bentley, and J. H. Atkinson. Smoked Medicinal Cannabis for Neuropathic Pain in Hiv: A Randomized, Crossover Clinical Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 672–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohler, N. L., J. L. Starrels, L. Khalid, M. A. Bachhuber, J. H. Arnsten, S. Nahvi, J. Jost, and C. O. Cunningham. Cannabis Use Is Associated with Lower Odds of Prescription Opioid Analgesic Use among Hiv-Infected Individuals with Chronic Pain. Subst Use Misuse 2018, 53, 1602–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D. I., C. A. Jay, S. B. Shade, H. Vizoso, H. Reda, S. Press, M. E. Kelly, M. C. Rowbotham, and K. L. Petersen. Cannabis in Painful Hiv-Associated Sensory Neuropathy: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Neurology 2007, 68, 515–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine, Health, Division Medicine, Health Board on Population, Practice Public Health, Review Committee on the Health Effects of Marijuana: An Evidence, and Agenda Research. The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health. In The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US).

- 2017 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

- Boland, E. G., M. I. Bennett, V. Allgar, and J. W. Boland. Cannabinoids for Adult Cancer-Related Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020, 10, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, E. B. Cannabis and Pain. Pain Med 2019, 20, 2083–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huestis, M. A., J. E. Henningfield, and E. J. Cone. Blood Cannabinoids. I. Absorption of Thc and Formation of 11-Oh-Thc and Thccooh during and after Smoking Marijuana. J Anal Toxicol 1992, 16, 276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. D. , and A. G. Winterstein. Potential Adverse Drug Events and Drug-Drug Interactions with Medical and Consumer Cannabidiol (Cbd) Use. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, N. Della Pepa, S. Oliaro-Bosso, E. Pessione, D. Gastaldi, and F. Dosio. Cannabinoid Delivery Systems for Pain and Inflammation Treatment. Molecules 2018, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo D, Kiselev MA, and Caccamo MT. Smart Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery Application: Development of Versatile Nanocarrier Platforms in Biotechnology and Nanomedicine. J Nanomater 2019, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, S. , and N. K. Wong. Nanotechnology and Its Use in Imaging and Drug Delivery (Review). Biomed Rep 2021, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. , and H. Sharma. Emerging Applications of Nanotechnology in Drug Delivery and Medical Imaging: Review. Curr Radiopharm 2023, 16, 269–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventola, C. L. Progress in Nanomedicine: Approved and Investigational Nanodrugs. P t 2017, 42, 742–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett, K., E. Onel, E. R. Viscusi, and K. Jones. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Dose-Ranging Study Comparing Wound Infiltration of Depofoam Bupivacaine, an Extended-Release Liposomal Bupivacaine, to Bupivacaine Hcl for Postsurgical Analgesia in Total Knee Arthroplasty. Knee 2012, 19, 530–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Q. Ye, M. Lu, S. T. Chen, H. W. Tseng, Y. C. Lo, and C. Ho. A New Approach to Deliver Anti-Cancer Nanodrugs with Reduced Off-Target Toxicities and Improved Efficiency by Temporarily Blunting the Reticuloendothelial System with Intralipid. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 16106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passero, F. C., Jr. Grapsa, K. N. Syrigos, and M. W. Saif. The Safety and Efficacy of Onivyde (Irinotecan Liposome Injection) for the Treatment of Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Following Gemcitabine-Based Therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2016, 16, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfayez, M., H. Kantarjian, T. Kadia, F. Ravandi-Kashani, and N. Daver. Cpx-351 (Vyxeos) in Aml. Leuk Lymphoma 2020, 61, 288–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlmann, C. H. , and M. Gross-Langenhoff. Efficacy and Tolerability of Leuprorelin Acetate (Eligard®) in Daily Practice in Germany: Pooled Data from 2 Prospective, Non-Interventional Studies with 3- or 6-Month Depot Formulations in Patients with Advanced Prostate Cancer. Urol Int 2018, 100, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishburn, C. S. The Pharmacology of Pegylation: Balancing Pd with Pk to Generate Novel Therapeutics. J Pharm Sci 2008, 97, 4167–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N. , and S. Stephens. Certolizumab Pegol. MAbs 2010, 2, 137–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, T. P., C. Hindocha, S. F. Green, and M. A. P. Bloomfield. Medicinal Use of Cannabis Based Products and Cannabinoids. Bmj 2019, 365, l1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacher, P., N. M. Kogan, and R. Mechoulam. Beyond Thc and Endocannabinoids. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2020, 60, 637–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grotenhermen, F. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Cannabinoids. Clin Pharmacokinet 2003, 42, 327–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S. E. B. Schultz, A. J. McLachlan, J. D. Henson, and L. Vitetta. Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability of Cannabinoids Administered Via a Novel Orobuccal Nanoparticle Formulation (Nanocelle™) in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitetta, L. Zhou, R. Manuel, S. Dal Forno, S. Hall, and D. Rutolo. Route and Type of Formulation Administered Influences the Absorption and Disposition of Vitamin B(12) Levels in Serum. J Funct Biomater 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S., B. E. Butcher, A. J. McLachlan, J. D. Henson, D. Rutolo, S. Hall, and L. Vitetta. Pilot Clinical and Pharmacokinetic Study of Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (Thc)/Cannabidiol (Cbd) Nanoparticle Oro-Buccal Spray in Patients with Advanced Cancer Experiencing Uncontrolled Pain. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0270543. [Google Scholar]

- Vitetta, L., B. Butcher, J. D. Henson, D. Rutolo, and S. Hall. A Pilot Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetic Study of an Oro-Buccal Administered Cannabidiol-Dominant Anti-Inflammatory Formulation in Healthy Individuals: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Single-Blinded Study. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1361–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang, C., K. Zhou, D. Wu, and H. Zhu. Nanoparticles as a Novel Platform for Cardiovascular Disease Diagnosis and Therapy. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 8831–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari Priya, V. M., A. A. Ganapathy, M. G. Veeran, M. S. Raphael, and A. Kumaran. Nanotechnology-Based Drug Delivery Platforms for Erectile Dysfunction: Addressing Efficacy, Safety, and Bioavailability Concerns. Pharm Dev Technol 2024, 29, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, J., P. Bedocs, Z. Rozsnyay, Z. Weiszhár, R. Urbanics, L. Rosivall, R. Cohen, O. Garbuzenko, G. Báthori, M. Tóth, R. Bünger, and Y. Barenholz. Liposome-Induced Complement Activation and Related Cardiopulmonary Distress in Pigs: Factors Promoting Reactogenicity of Doxil and Ambisome. Nanomedicine 2012, 8, 176–84. [Google Scholar]

- Crisafulli, S., P. M. Cutroneo, N. Luxi, A. Fontana, C. Ferrajolo, P. Marchione, L. Sottosanti, G. Zanoni, U. Moretti, S. Franzè, P. Minghetti, and G. Trifirò. Is Pegylation of Drugs Associated with Hypersensitivity Reactions? An Analysis of the Italian National Spontaneous Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System. Drug Saf 2023, 46, 343–55. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, J. D. U. S Food and Drug Administration Approval of Ambisome (Liposomal Amphotericin B) for Treatment of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis 1999, 28, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, A. M., M. A. Alnuhait, and T. Alqahtani. The Clinical Safety and Efficacy of Cytarabine and Daunorubicin Liposome (Cpx-351) in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2025, 8, e70199. [Google Scholar]

- Tiriveedhi, V., K. M. Kitchens, K. J. Nevels, H. Ghandehari, and P. Butko. Kinetic Analysis of the Interaction between Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimers and Model Lipid Membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1808, 209–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., B. Li, L. Qiu, X. Qiao, and H. Yang. Dendrimer-Based Drug Delivery Systems: History, Challenges, and Latest Developments. J Biol Eng 2022, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, J. D. Vitetta, M. Quezada, and S. Hall. Enhancing Endocannabinoid Control of Stress with Cannabidiol. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasinu, P. S., S. Phillips, M. A. ElSohly, and L. A. Walker. Current Status and Prospects for Cannabidiol Preparations as New Therapeutic Agents. Pharmacotherapy 2016, 36, 781–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L., B. Gidal, G. Blakey, B. Tayo, and G. Morrison. A Phase I, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Single Ascending Dose, Multiple Dose, and Food Effect Trial of the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Highly Purified Cannabidiol in Healthy Subjects. CNS Drugs 2018, 32, 1053–67. [Google Scholar]

- Guy GW, and Flint ME. A Single Centre, Placebo-Controlled, Four Period, Crossover, Tolerability Study Assessing, Pharmacodynamic Effects, Pharmacokinetic Characteristics and Cognitive Profiles of a Single Dose of Three Formulations of Cannabis Based Medicine Extracts (Cbmes) (Gwpd9901), Plus a Two Period Tolerability Study Comparing Pharmacodynamic Effects and Pharmacokinetic Characteristics of a Single Dose of a Cannabis Based Medicine Extract Given Via Two Administration Routes (Gwpd9901 Ext). Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics 2004, 3, 35–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, A., J. E. Lindgren, S. Andersson, S. Agurell, H. Gillespie, and L. E. Hollister. Single-Dose Kinetics of Deuterium-Labelled Cannabidiol in Man after Smoking and Intravenous Administration. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom 1986, 13, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).