Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

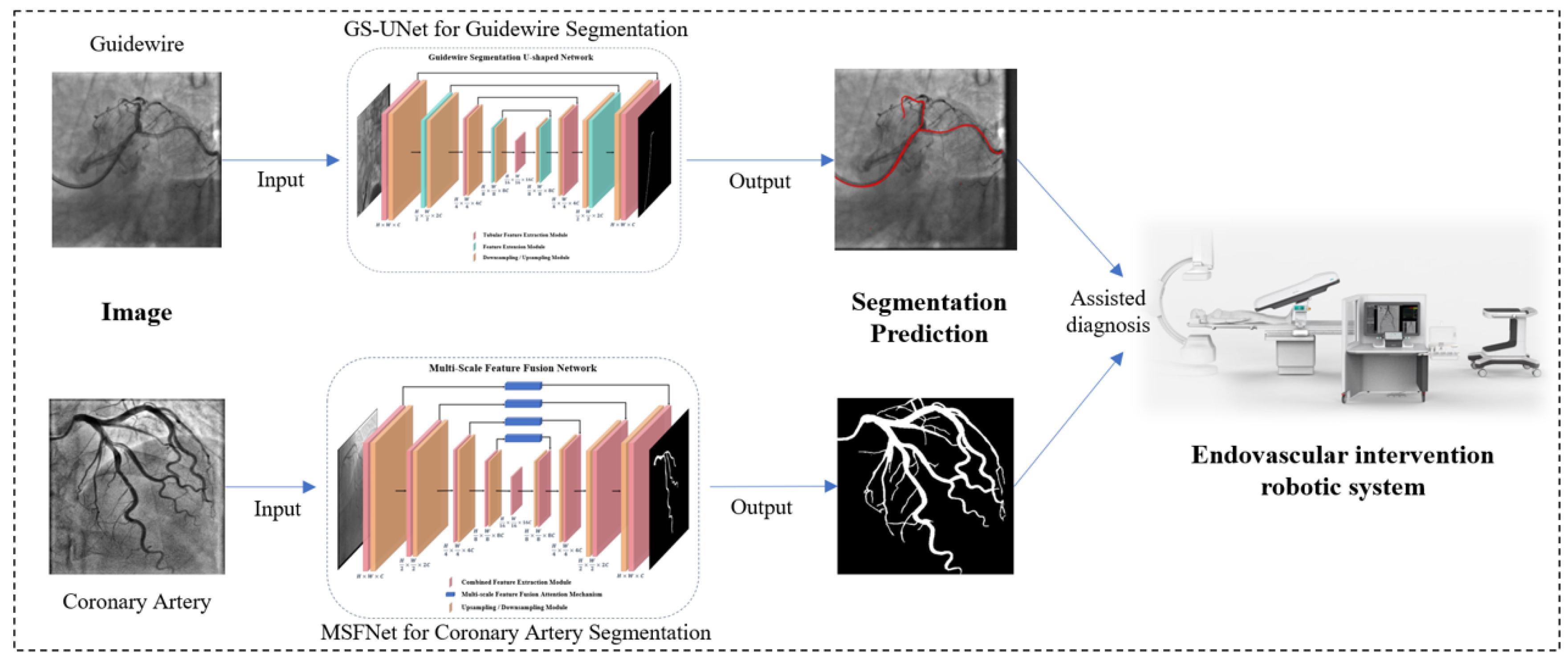

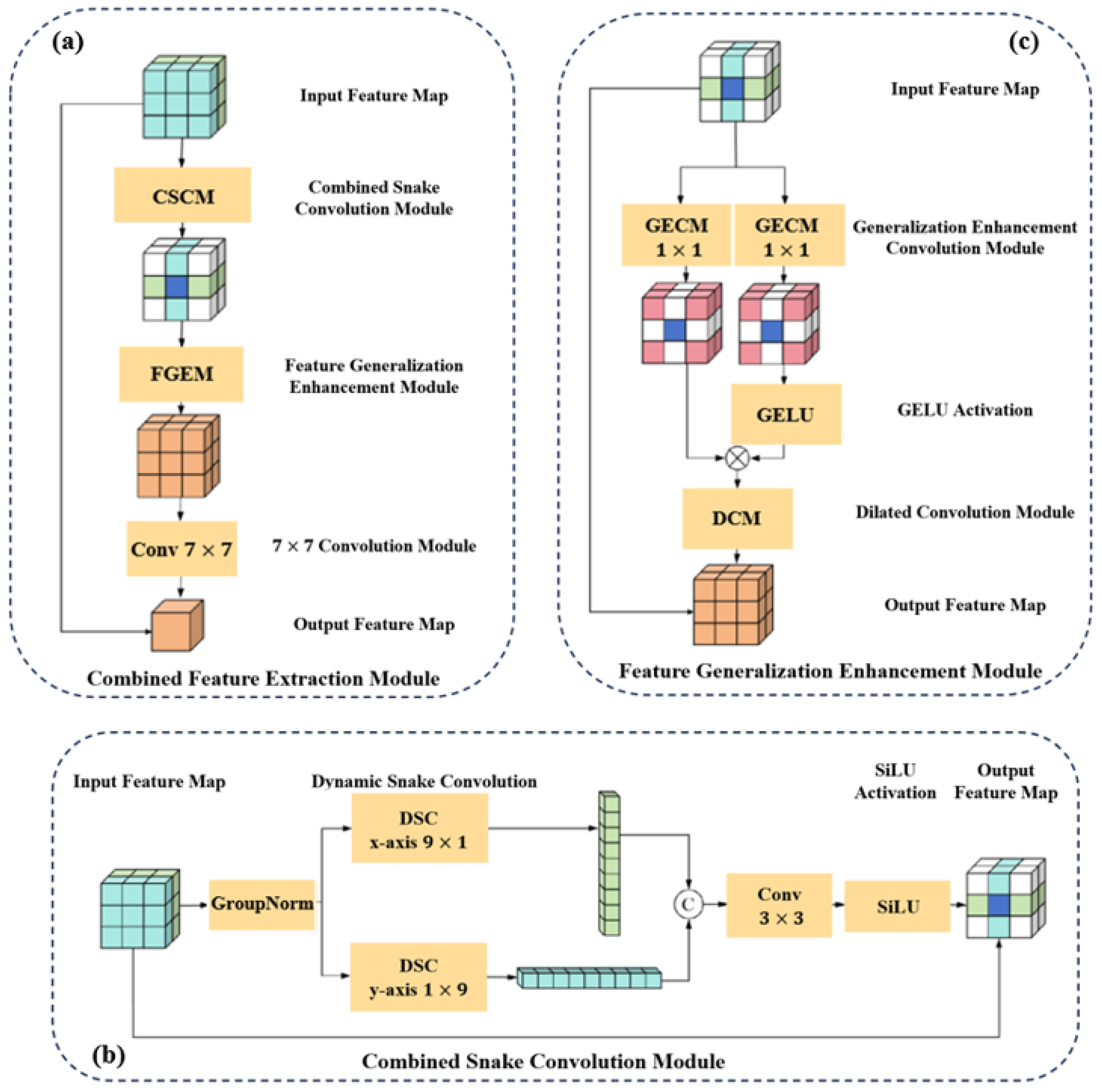

- To accurately identify the elongated morphological structures of guidewires and improve structural integrity, we design a Tubular Feature Extraction Module (TFEM) that significantly enhances the model’s ability to capture tubular features. Building upon this, we develop a Combined Feature Extraction Module (CFEM) tailored to the elongated and tortuous characteristics of vascular morphology. This module combines local detail perception with global structural modeling capabilities, effectively strengthening the response to small-scale vessels and multi-branch structures.

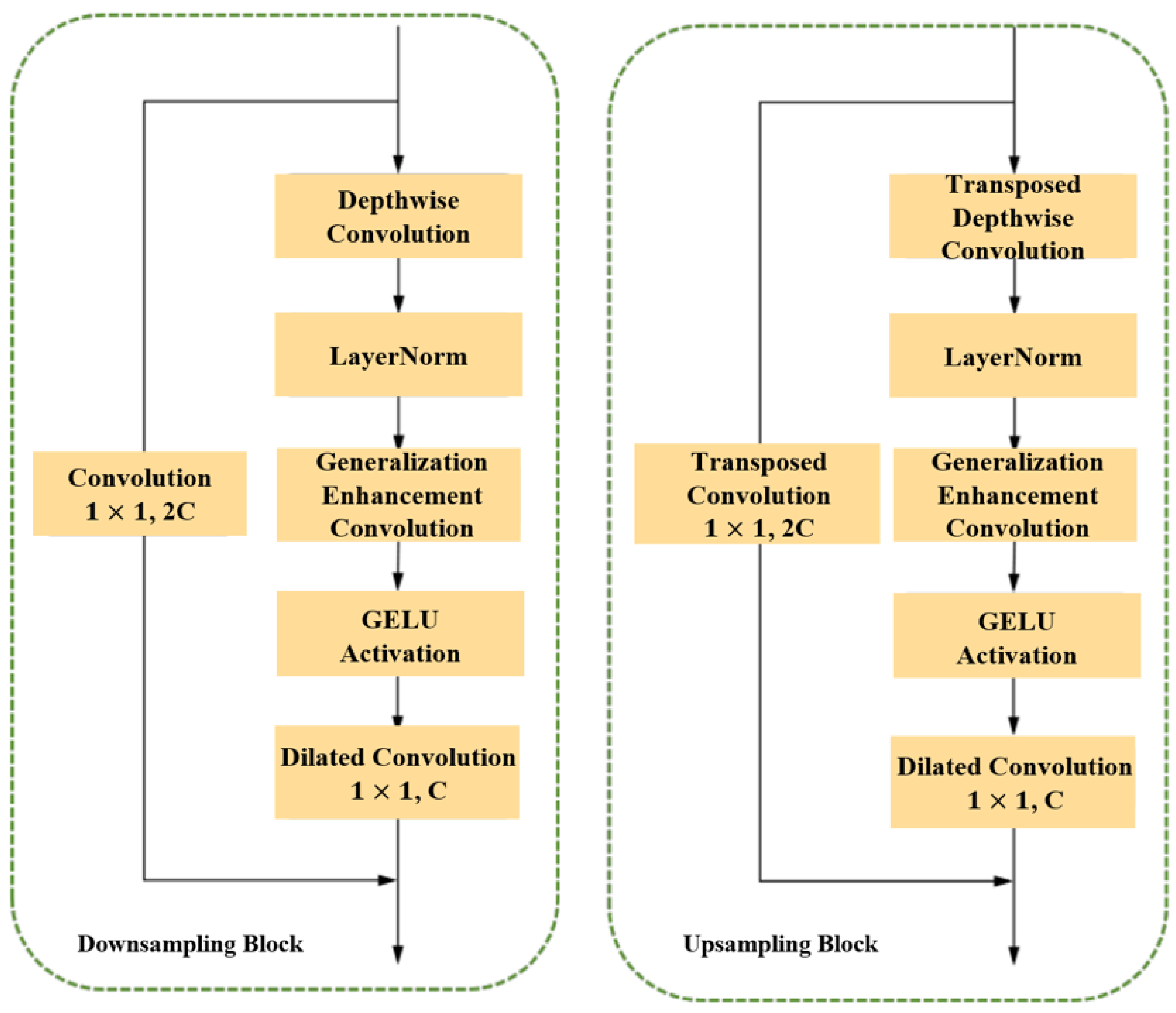

- We propose a Feature Extension Module (FEM) that, while reducing the overall computational complexity of the model, enhances the network’s feature generalization ability, enabling robust discrimination of guidewires with varying shapes and positions. Based on this module, for the task of vessel segmentation, we further design a Feature Generalization Enhancement Module (FGEM) that effectively improves the model’s generalization capacity to image features, enhancing robustness across different imaging modalities and complex backgrounds.

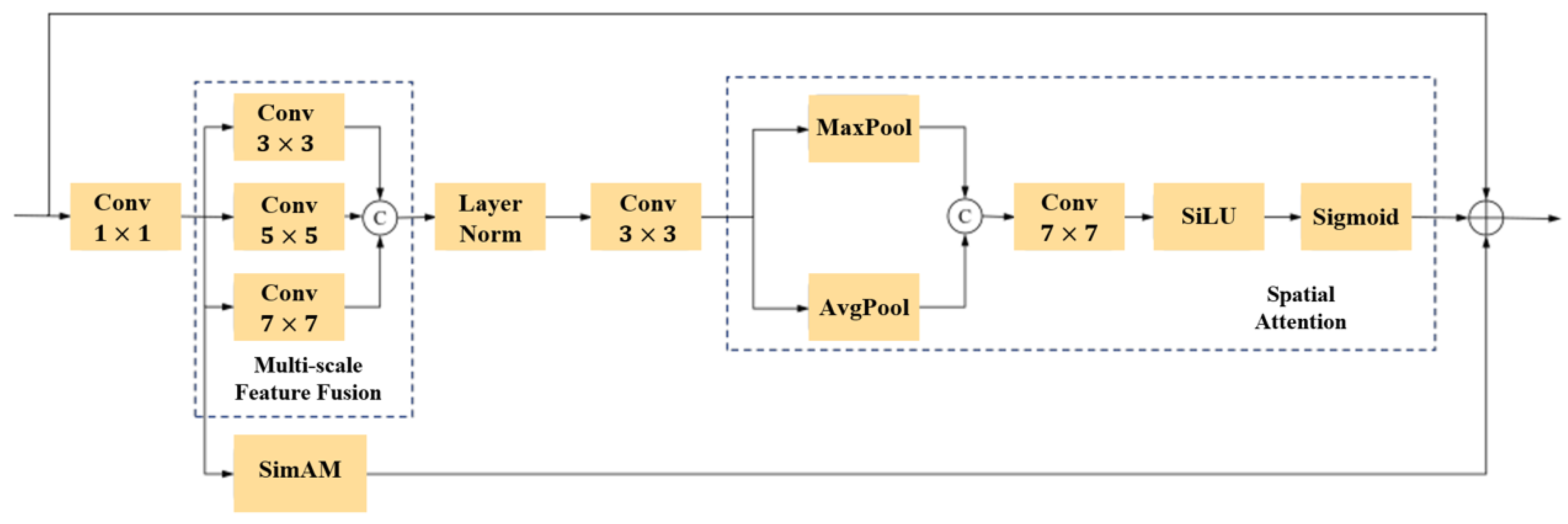

- We introduce a multi-scale feature fusion attention mechanism (MFFA), which aggregates rich spatial contextual information from multiple receptive field scales between the encoder and decoder. Through attention-guided weighting, the model adaptively emphasizes regions relevant to coronary vessels in the image, thereby enhancing attention to fine-grained details and target areas. This leads to more accurate segmentation of vascular regions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional Methods for Guidewires and Coronary Artery Segmentation

2.2. Deep Learning Methods for Guidewires and Coronary Artery Segmentation

3. Methodology

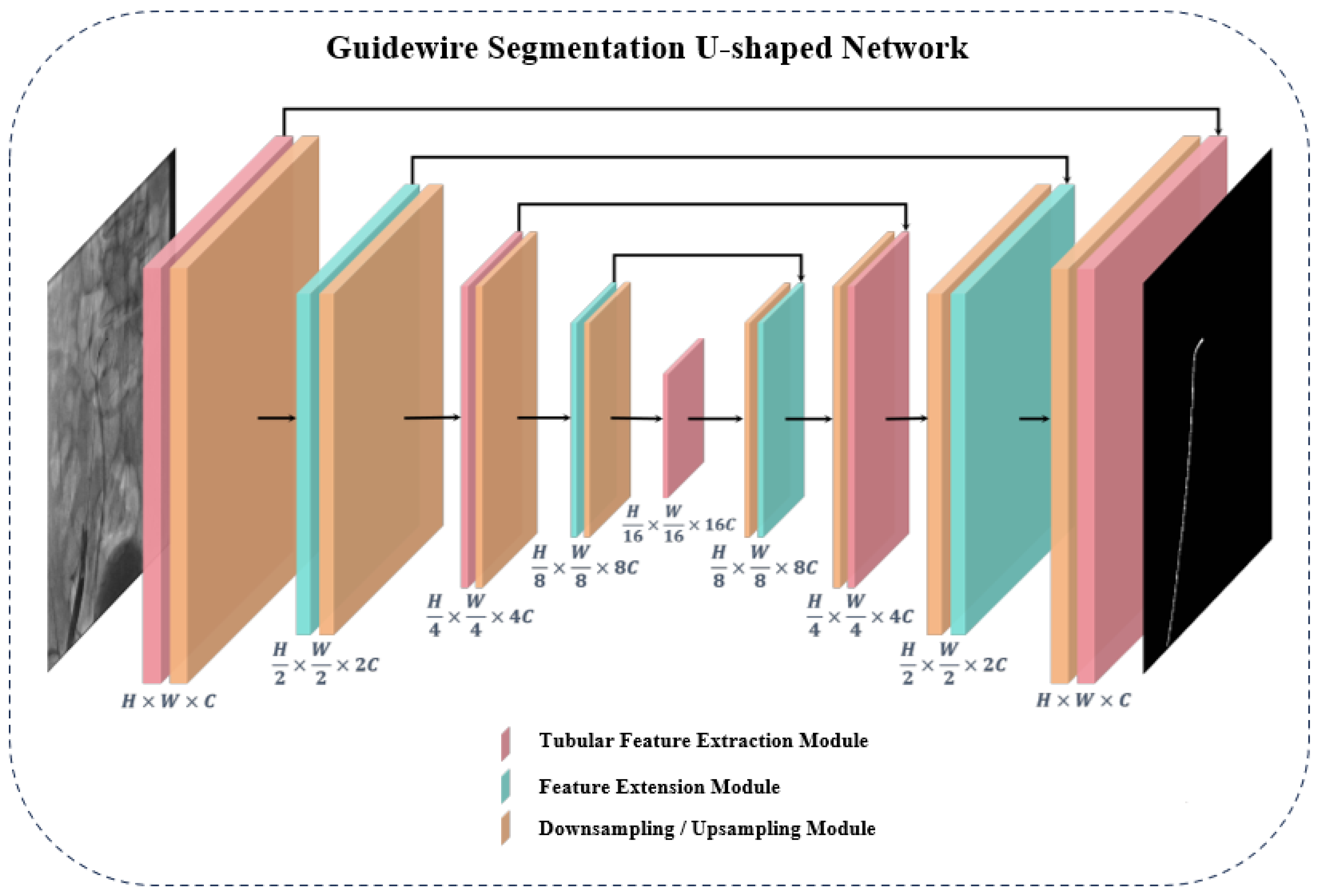

3.1. Overall Architecture of the Guidewire Segmentation Network

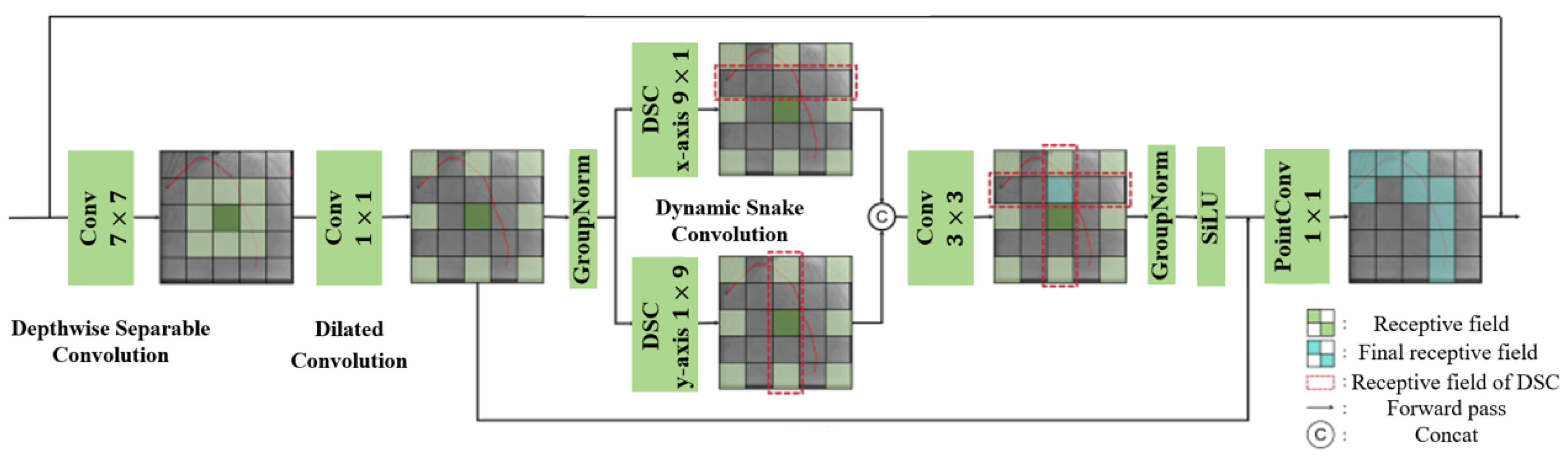

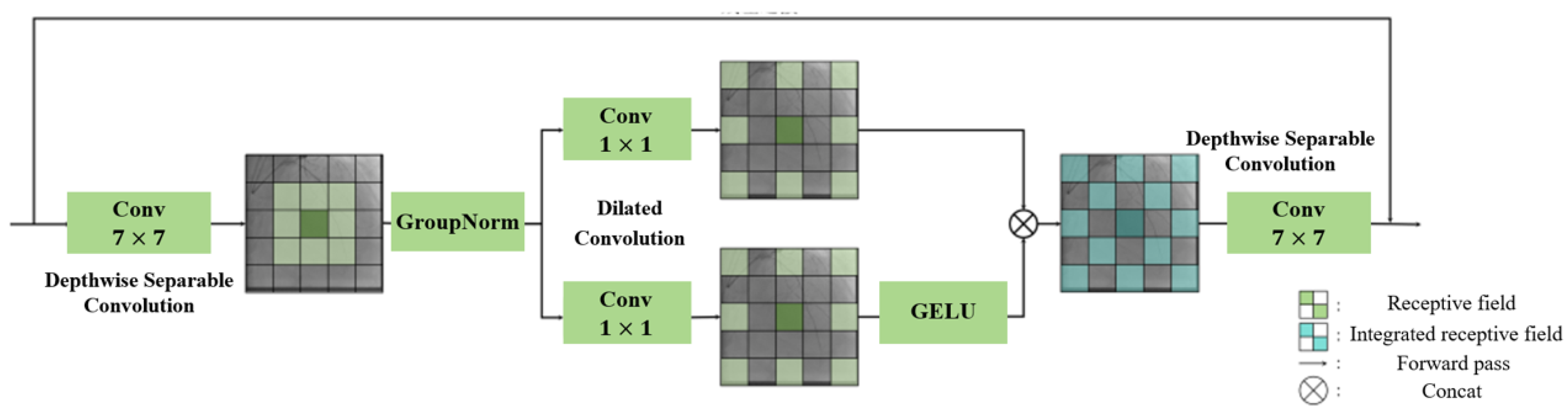

3.1.1. Tubular Feature Extraction Module in Guidewire Segmentation Network

3.1.2. Feature Extension Module in Guidewire Segmentation Network

3.1.3. Sampling Module in the Encoder-Decoder Architecture

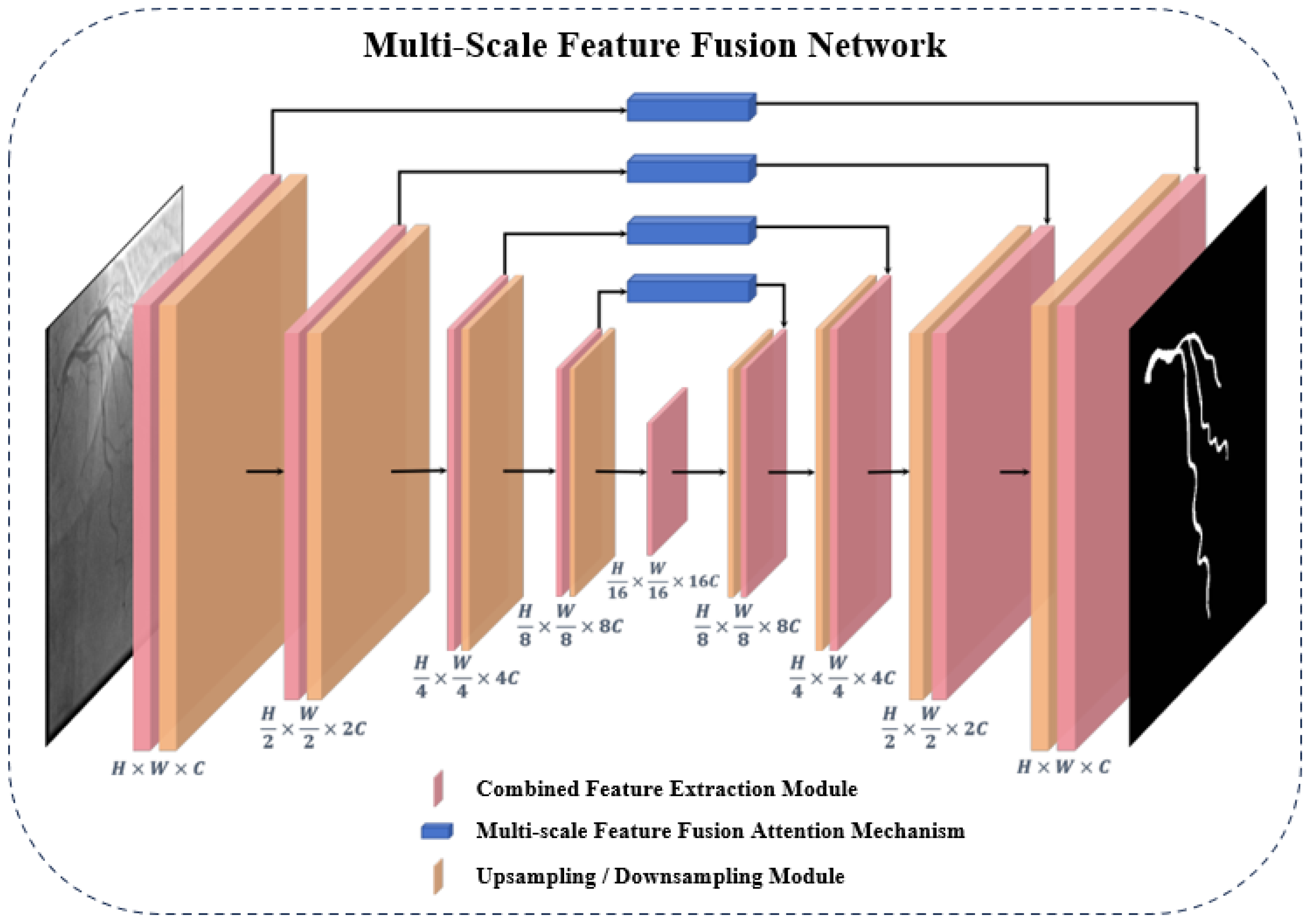

3.2. Overall Architecture of the Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Network

3.2.1. Combined Feature Extraction Module in the Encoder-Decoder Architecture

3.2.2. Multi-scale Feature Fusion Attention Mechanism in Skip Connections

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Implementation Detail

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

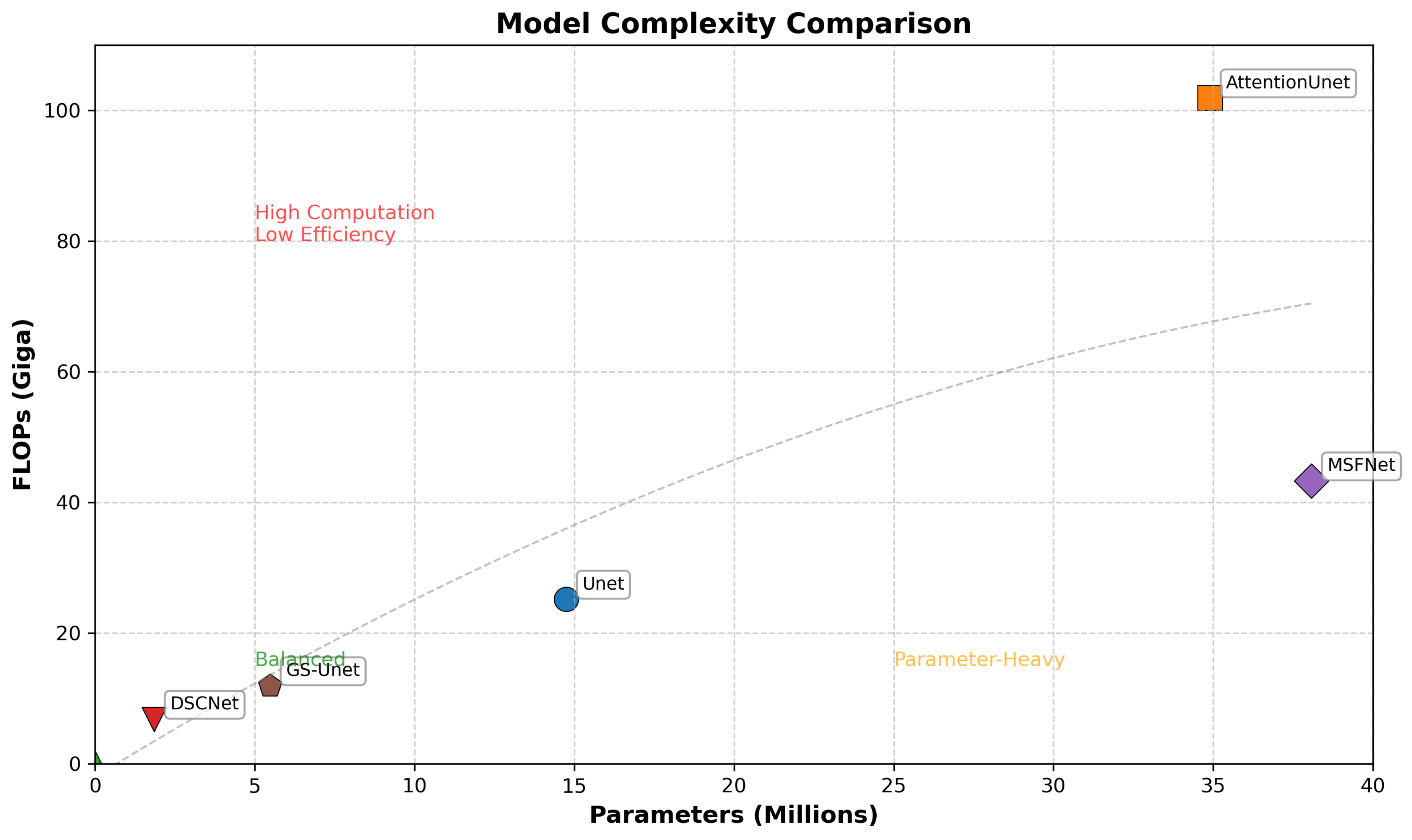

4.4. Results

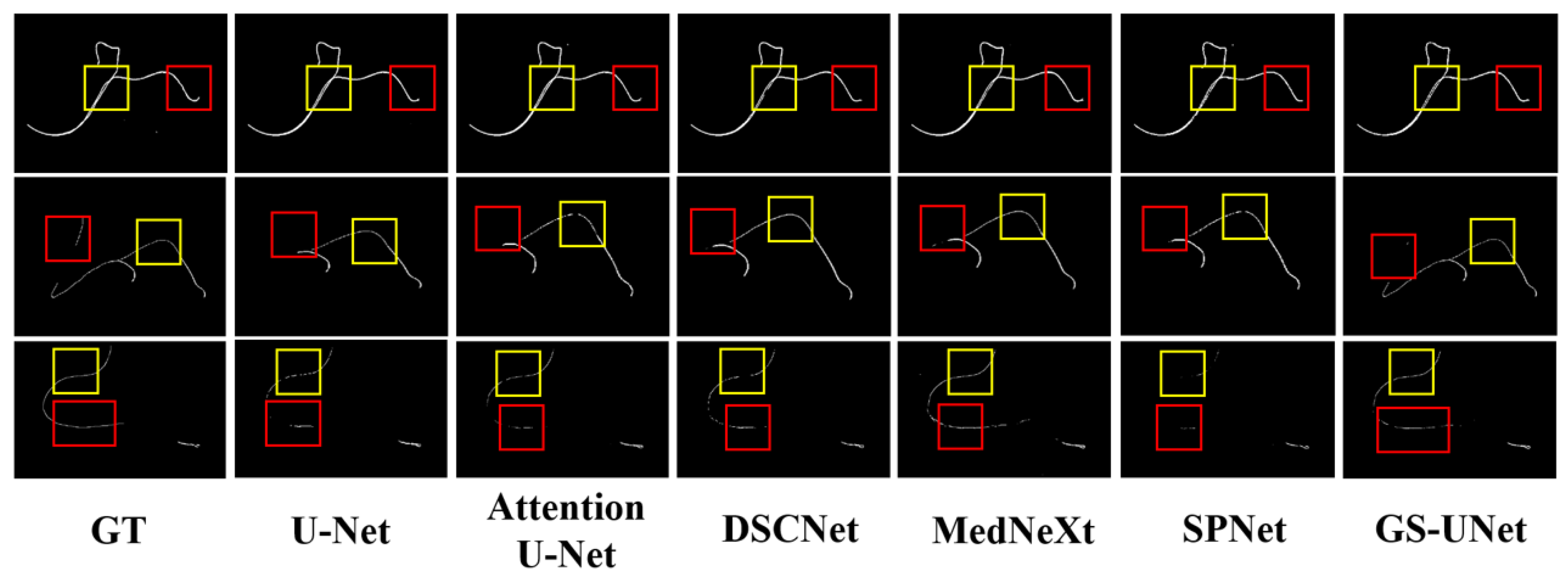

4.4.1. Segmentation Performance on the Guidewire dataset

| Method | DSC↑ | HD95↓ | Recall↑ | Precison↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (% mean) | (mm, mean) | (%, mean) | (%, mean) | |

| U-Net | 85.56 | 11.956 | 86.69 | 85.41 |

| Attention U-Net | 85.87 | 10.113 | 84.64 | 86.16 |

| DSCNet | 85.90 | 11.350 | 86.86 | 85.75 |

| MedNeXt | 86.11 | 10.179 | 86.81 | 86.01 |

| SPNet | 82.91 | 20.995 | 83.63 | 83.65 |

| GS-UNet | 86.31 | 8.685 | 86.88 | 86.69 |

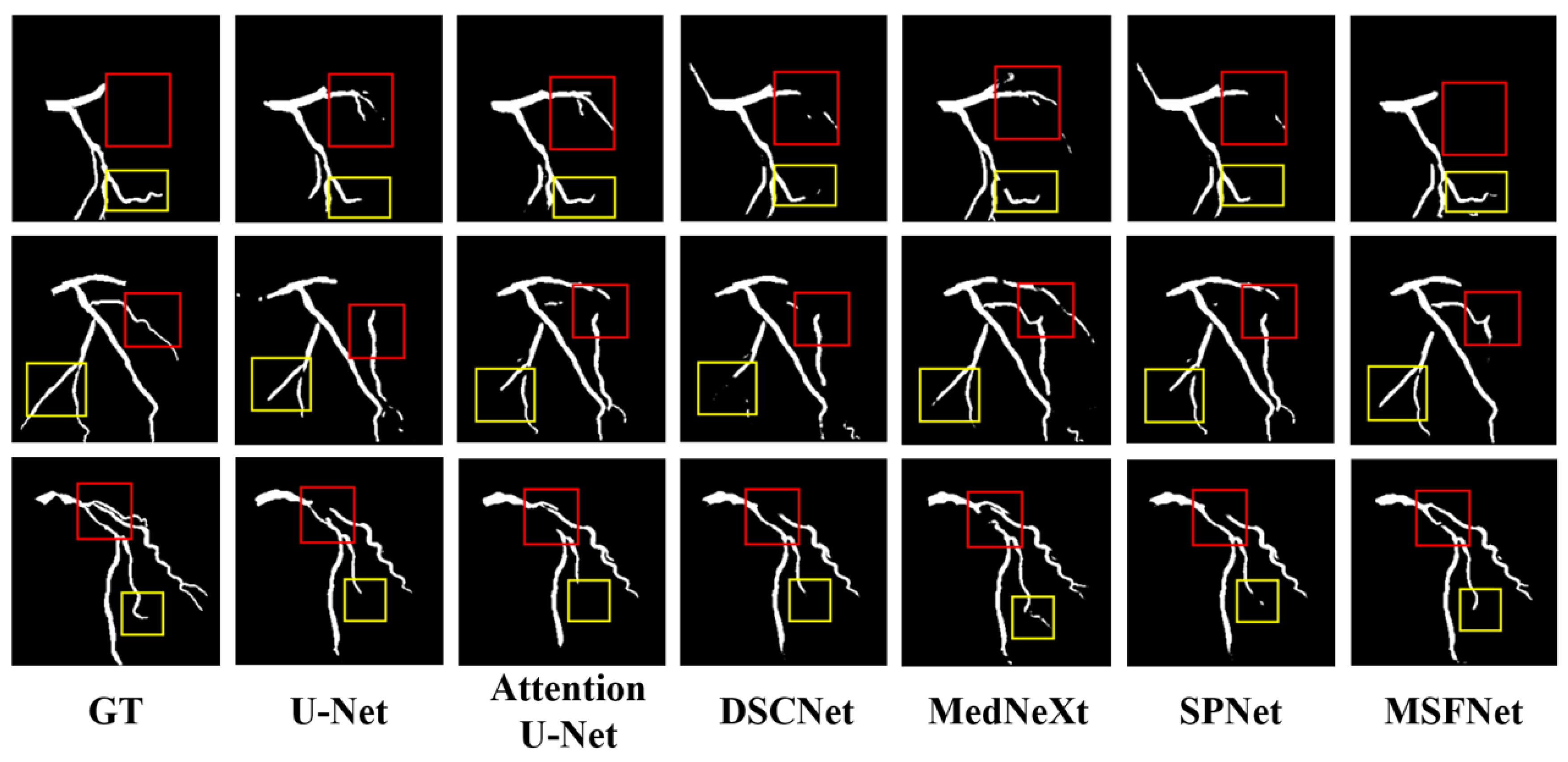

4.4.2. Segmentation Performance on the ARCADE dataset

| Method | DSC↑ | HD95↓ | Recall↑ | Precison↑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (% mean) | (mm, mean) | (%, mean) | (%, mean) | |

| U-Net | 72.26 | 76.013 | 69.63 | 77.88 |

| Attention U-Net | 72.51 | 72.021 | 70.01 | 78.12 |

| DSCNet | 73.48 | 69.527 | 73.60 | 75.24 |

| MedNeXt | 75.10 | 61.960 | 72.50 | 80.02 |

| SPNet | 55.90 | 79.391 | 59.92 | 54.17 |

| MSFNet(without MFFA) | 75.39 | 61.877 | 73.20 | 79.64 |

| MSFNet | 76.74 | 57.836 | 74.87 | 80.66 |

5. Limitation

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

References

- Khan, S.Q.; Ludman, P.F. Percutaneous coronary intervention. Medicine 2022, 50, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimagli, A.; Spadaccio, C.; Myers, A.; Demetres, M.; Rademaker-Havinga, T.; Stone, G.W.; Spertus, J.A.; Redfors, B.; Fremes, S.; Gaudino, M.; et al. Quality of life after percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting. Journal of the American Heart Association 2023, 12, e030069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhalil, M. An Overview of Current Advances in Contemporary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Current Cardiology Reviews 2022, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvandi, M.; Javid, R.N.; Shaghaghi, Z.; Farzipour, S.; Nosrati, S. An in-depth analysis of the adverse effects of ionizing radiation exposure on cardiac catheterization staffs. Current Radiopharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, W.T.; Sharieff, W.; Jolly, S.S.; Hong, T.; Kutryk, M.J.; Graham, J.J.; Fam, N.P.; Chisholm, R.J.; Cheema, A.N. Characterization of operator learning curve for transradial coronary interventions. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions 2011, 4, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C.d.L.; Abreu, L.C.d.; Ramos, J.L.S.; Castro, C.F.D.d.; Smiderle, F.R.N.; Santos, J.A.d.; Bezerra, I.M.P. Influence of burnout on patient safety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina 2019, 55, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, T.M.; Shah, S.C.; Pancholy, S.B. Long distance tele-robotic-assisted percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of first-in-human experience. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 14, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ajczak, P.; Ayesha, A.; Sahin, O.K.; Freeman, P.I.; Majeed, M.W.; Righetto, B.B.; Obi, O.; Moreno, G.J.; Krishna, M.M.; Mulenga, K.F.; et al. Comparison between robot-assisted and manual percutaneous coronary intervention-an updated systematic review, meta-analysis, propensity-matched investigation, and trial sequential analysis. Cardiovascular Intervention and Therapeutics 2025, pp. 1–16.

- Covello, B.; McKeon, B. Fluoroscopic angiography assessment, protocols, and interpretation; StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2022.

- Popov, M.; Amanturdieva, A.; Zhaksylyk, N.; Alkanov, A.; Saniyazbekov, A.; Aimyshev, T.; Ismailov, E.; Bulegenov, A.; Kuzhukeyev, A.; Kulanbayeva, A.; et al. Dataset for automatic region-based coronary artery disease diagnostics using X-ray angiography images. Scientific data 2024, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, D.; Kaur, Y. Various image segmentation techniques: a review. International journal of computer science and Mobile Computing 2014, 3, 809–814. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Quan, R.; Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, F. Advances in medical image segmentation: A comprehensive review of traditional, deep learning and hybrid approaches. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthilkumaran, N.; Vaithegi, S. Image segmentation by using thresholding techniques for medical images. Computer Science & Engineering: An International Journal 2016, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amri, S.S.; Kalyankar, N.; Khamitkar, S. Image segmentation by using edge detection. International journal on computer science and engineering 2010, 2, 804–807. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.; Bischof, L. Seeded region growing. IEEE Transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 1994, 16, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zeng, G.; Body, M.; Hacid, M.S. Seeded region growing: an extensive and comparative study. Pattern recognition letters 2005, 26, 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, Y.; Fateh, M.; Rezvani, M.; Abolghasemi, V.; Anisi, M.H. ResBCDU-Net: a deep learning framework for lung CT image segmentation. Sensors 2021, 21, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.; Badiei Khuzani, M.; Vasudevan, V.; Huang, C.; Ren, H.; Xiao, R.; Jia, X.; Xing, L. Machine learning techniques for biomedical image segmentation: an overview of technical aspects and introduction to state-of-art applications. Medical physics 2020, 47, e148–e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, T.Y.; Basah, S.N.; Yazid, H.; Safar, M.J.A.; Saad, F.S.A. Performance analysis of image thresholding: Otsu technique. Measurement 2018, 114, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.S. Comparative study among Sobel, Prewitt and Canny edge detection operators used in image processing. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol 2018, 96, 6517–6525. [Google Scholar]

- Forcadel, N.; Le Guyader, C.; Gout, C. Generalized fast marching method: applications to image segmentation. Numerical Algorithms 2008, 48, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisha, R.; Khan, A. Morphological operations for image processing: understanding and its applications. NCVSComs-13 2013, 13, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G.; Jordan, M.; Ilono, P. Deep convolutional neural networks in medical image analysis: A review. Information 2025, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, R.; Nishio, M.; Do, R.K.G.; Togashi, K. Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology. Insights into imaging 2018, 9, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Qin, C.; Qiu, H.; Tarroni, G.; Duan, J.; Bai, W.; Rueckert, D. Deep learning for cardiac image segmentation: a review. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine 2020, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention. Springer, 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. Unet++: A nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International workshop on deep learning in medical image analysis. Springer; 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention u-net: Learning where to look for the pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 7132–7141.

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 3–19.

- Yao, W.; Bai, J.; Liao, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, M.; Xie, Y. From cnn to transformer: A review of medical image segmentation models. Journal of Imaging Informatics in Medicine 2024, 37, 1529–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision. Springer, 2022, pp. 205–218.

- Urrea, C.; Vélez, M. Advances in Deep Learning for Semantic Segmentation of Low-Contrast Images: A Systematic Review of Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sensors 2025, 25, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; He, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023, pp. 6070–6079.

- Kaiser, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Chollet, F. Depthwise separable convolutions for neural machine translation. arXiv, 2017; arXiv:1706.03059. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; He, K. Group normalization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 3–19.

- Niu, Z.; Zhong, G.; Yu, H. A review on the attention mechanism of deep learning. Neurocomputing 2021, 452, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, R.Y.; Li, L.; Xie, X. Simam: A simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 11863–11874.

- Roy, S.; Koehler, G.; Ulrich, C.; Baumgartner, M.; Petersen, J.; Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P.F.; Maier-Hein, K.H. Mednext: transformer-driven scaling of convnets for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, 2023, pp. 405–415.

- Qi, Y.; He, Y.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, G. Dynamic snake convolution based on topological geometric constraints for tubular structure segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2023, pp. 6070–6079.

- Hou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, M.M.; Feng, J. Strip pooling: Rethinking spatial pooling for scene parsing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020, pp. 4003–4012.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).