1. Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a global health crisis projected to surge in prevalence, is traditionally attributed to peripheral insulin resistance driven by obesity, oxidative stress, and inflammation [

1]. Yet, these models often overlook the critical role of insulin’s structural integrity, particularly its sulfur-dependent disulfide bonds. The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis offers a groundbreaking framework, asserting that mitochondrial dysfunction in intestinal epithelial cells termed mitochondrial suffocation triggers organic sulfur deficiency, leading to insulin misfolding and systemic insulin resistance. This research aims to compile and elucidate evidence linking defective disulfide bond formation to insulin dysfunction, redefining T2DM as a sulfur metabolism disorder and revolutionizing its mechanistic interpretation. Insulin, a 51-amino-acid polypeptide, relies on three disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19) formed through cysteine thiol oxidation to maintain its bioactive conformation for high-affinity insulin receptor binding [

2]. These bonds, dependent on dietary methionine and cysteine via the transsulfuration pathway, are disrupted by mitochondrial suffocation, which impairs adenosine triphosphate production and inhibits cystathionine β-synthase and γ-lyase, reducing cysteine availability [

3,

4,

5,

6]. This sulfur scarcity compromises protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) activity in pancreatic beta cells, leading to aberrant disulfide bond formation and misfolded insulin with reduced receptor affinity [

7]. Such structural defects disrupt phosphoinositide 3-kinase-protein kinase B (PI3K-Akt) signaling, impairing glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation and glucose uptake [

8]. Concurrently, sulfur deficiency elevates reactive oxygen species (ROS), activating nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6), which exacerbate insulin resistance through c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 [

9,

10,

11]. Oxidative stress also weakens gut barrier integrity, promoting toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated endotoxemia and systemic inflammation [

12,

13]. By presenting evidence on disulfide bond formation and its disruption, this study elucidates the gut-mitochondria-sulfur-insulin axis, offering a transformative lens to reinterpret insulin resistance and guide innovative T2DM therapeutic strategies.

2. Methodology

This Review presents the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis, a novel framework proposing that sulfur deficiency, driven by mitochondrial dysfunction in the intestinal epithelium, causes insulin misfolding and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). To develop this hypothesis, we conducted a structured literature synthesis to integrate mechanistic evidence from redox biology, mitochondrial pathology, protein biochemistry, and immunometabolism. A comprehensive literature search was performed across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms, including “sulfur metabolism,” “insulin misfolding,” “disulfide bonds,” “glutathione deficiency,” “mitochondrial dysfunction,” “intestinal epithelium,” “oxidative stress,” “transsulfuration pathway,” “endoplasmic reticulum stress,” “cysteine,” and “type 2 diabetes.” Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to combine terms, ensuring interdisciplinary coverage.

The search included peer-reviewed studies from 1995 to 2025, capturing foundational and recent insights into sulfur-dependent metabolic regulation. From an initial pool of 1,202 articles, 243 duplicates were removed, and 959 unique articles were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 624 were excluded due to irrelevance, insufficient mechanistic focus, non-English language, or inaccessible full texts. Full-text evaluation of 334 articles, based on inclusion criteria (relevance to insulin biosynthesis, disulfide bond integrity, mitochondrial-glutathione axis, and immunological impacts of sulfur deficiency), yielded 113 studies for inclusion. These encompassed in vitro models of insulin folding, animal studies of metabolic stress, human sulfur biomarker data, and pharmacologic trials of sulfur donors (e.g., N-acetylcysteine, methylsulfonylmethane). Data were synthesized to construct a mechanistic model linking mitochondrial dysfunction, cysteine scarcity, glutathione depletion, and insulin misfolding to T2DM pathogenesis. To test the hypothesis, we propose experimental approaches, including: (1) proteomic analyses to detect misfolded insulin in T2DM patients; (2) metabolomic profiling of sulfur metabolites (e.g., cysteine, glutathione) in intestinal and systemic tissues; (3) in vitro studies of enterocyte mitochondrial function under sulfur-deficient conditions; (4) animal models to assess N-acetylcysteine and methylsulfonylmethane effects on insulin structure and glucose homeostasis; and (5) clinical trials to evaluate sulfur donor supplementation in T2DM patients. The synthesis adheres to the SANRA framework, scoring 10/12 for clarity, evidence selection, and conceptual integration. This hypothesis-driven framework aims to redefine T2DM etiology and guide future research into sulfur-centric therapies.

3. Mitochondrial Suffocation as the Origin of Sulfur Deficiency

The intestinal epithelium, a metabolic hub for processing sulfur-containing amino acids, relies on robust mitochondrial function to support energy-intensive nutrient absorption [

14,

15]. In type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), chronic stressors like hyperglycemia and high-fat diets induce mitochondrial dysfunction in enterocytes, termed mitochondrial suffocation, disrupting the electron transport chain (ETC), particularly complexes I and III [

16,

17]. This reduces adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and generates excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), depleting cellular antioxidants and impairing sulfur metabolism [

18,

19]. ROS overproduction exhausts glutathione, a cysteine-dependent tripeptide critical for redox homeostasis, exacerbating cellular damage [

20]. The transsulfuration pathway, converting methionine to cysteine via methionine adenosyltransferase, cystathionine β-synthase, and cystathionine γ-lyase, is compromised by ATP scarcity, reducing cysteine synthesis [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

This cysteine deficiency disrupts glutathione production and protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) activity, impairing insulin’s disulfide bond formation (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19), leading to misfolded insulin with diminished receptor-binding capacity [

26,

27,

28]. Immunologically, mitochondrial suffocation triggers nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) activation, upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6) that promote c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-mediated serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1, disrupting phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling and exacerbating insulin resistance [

29,

30,

31].

Additionally, ROS-induced downregulation of tight junction proteins (occludin, zonula occludens-1) compromises gut barrier integrity, enabling lipopolysaccharide translocation and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated endotoxemia, further amplifying systemic inflammation [

32,

33,

34].This gut-mitochondria-sulfur-insulin axis underscores mitochondrial suffocation as a pivotal driver of sulfur deficiency and T2DM pathogenesis.

4. The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis: A Transformative Framework

The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis redefines type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) by asserting that sulfur deficiency, stemming from mitochondrial dysfunction in intestinal epithelial cells, drives insulin misfolding, a primary trigger of insulin resistance. Insulin, a 51-amino-acid polypeptide comprising A (21 amino acids) and B (30 amino acids) chains, is stabilized by three disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19) formed through cysteine thiol oxidation, essential for its three-dimensional conformation and high-affinity binding to the insulin receptor [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. In pancreatic beta cells, insulin biosynthesis starts with preproinsulin, cleaved to proinsulin, and folded in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) catalyzes disulfide bond formation by oxidizing cysteine residues, a process critically dependent on cysteine availability [

41,

42]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, termed mitochondrial suffocation, impairs the transsulfuration pathway by reducing adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent activity of cystathionine β-synthase and γ-lyase, limiting cysteine synthesis [

43,

44].

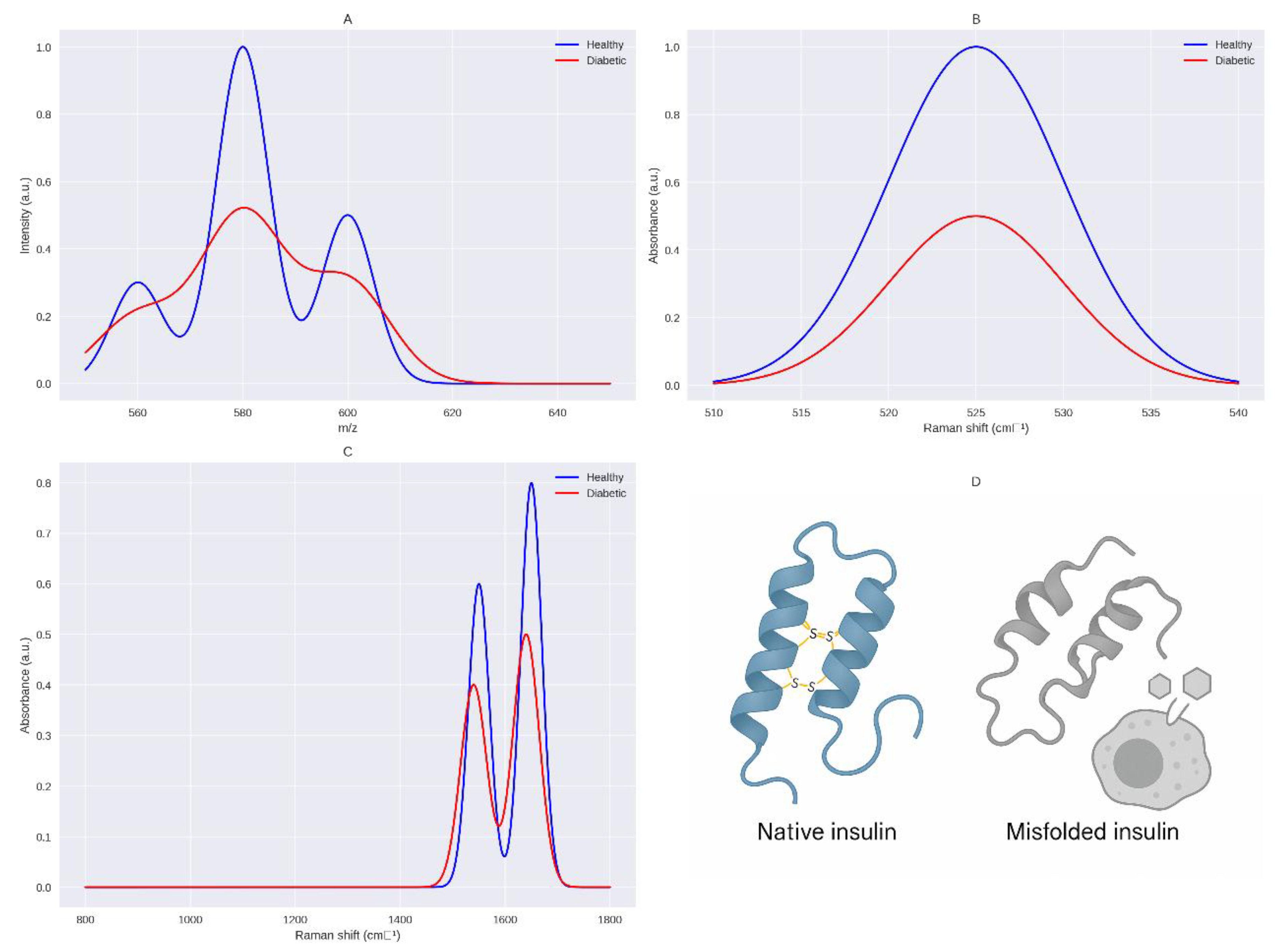

This cysteine scarcity disrupts PDI function, leading to incomplete or aberrant disulfide bonds, producing misfolded insulin with altered tertiary structure, as demonstrated by Raman spectroscopy (510–540 cm

−1) showing reduced bond integrity (

Figure 1) [

45,

46]. Misfolded insulin compromises the insulin signaling cascade, pivotal for glucose homeostasis. Normally, insulin binds the insulin receptor, a tyrosine kinase with extracellular α-subunits and intracellular β-subunits, inducing autophosphorylation at tyrosine residues (Tyr1158, Tyr1162, Tyr1163) [

47,

48]. This recruits insulin receptor substrates (IRS-1/2), activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), which converts phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, triggering protein kinase B (Akt) via phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 [

49,

50]. Akt promotes glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation to the plasma membrane in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, facilitating glucose uptake, and inhibits hepatic gluconeogenesis by suppressing phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase [

51,

52].

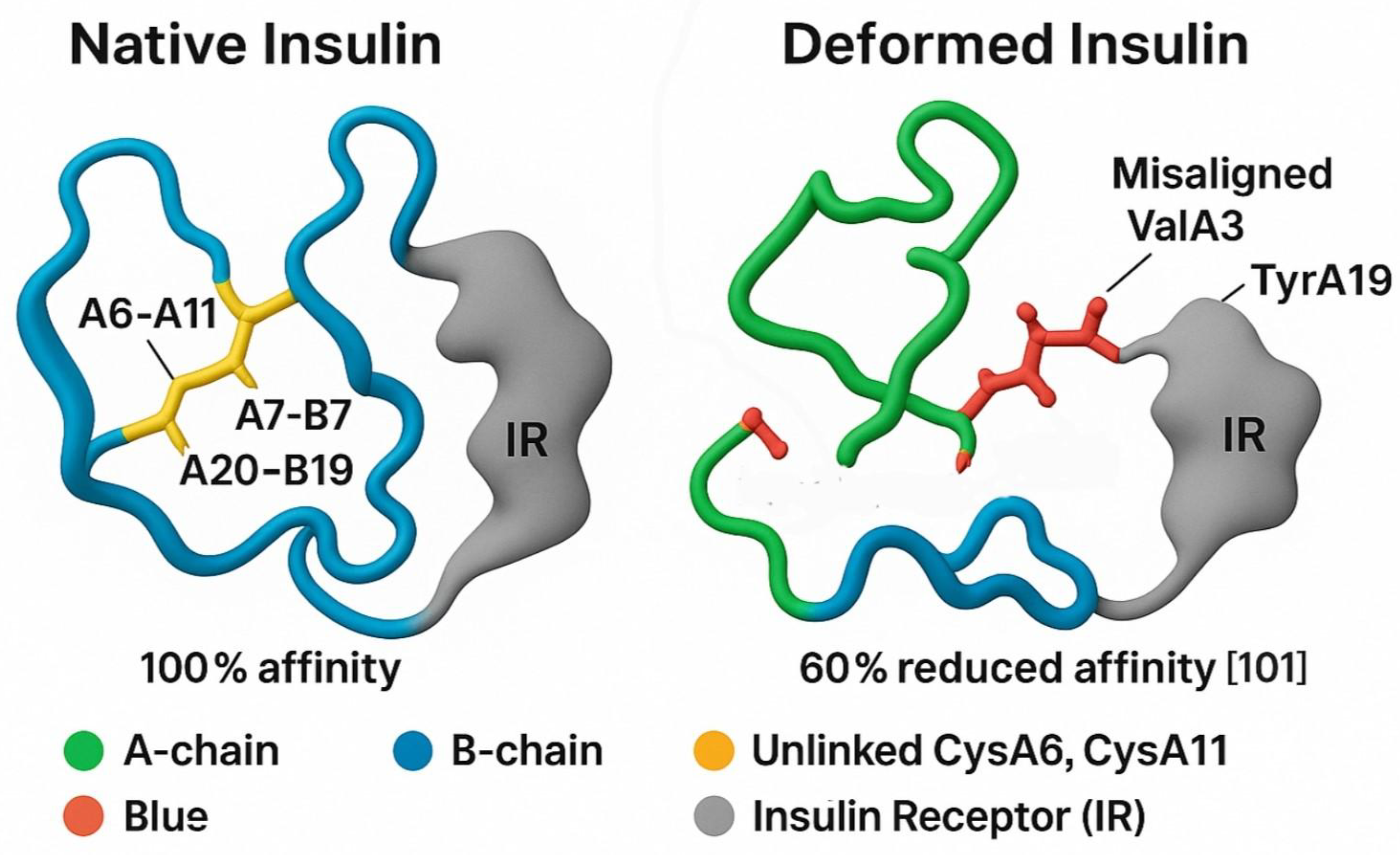

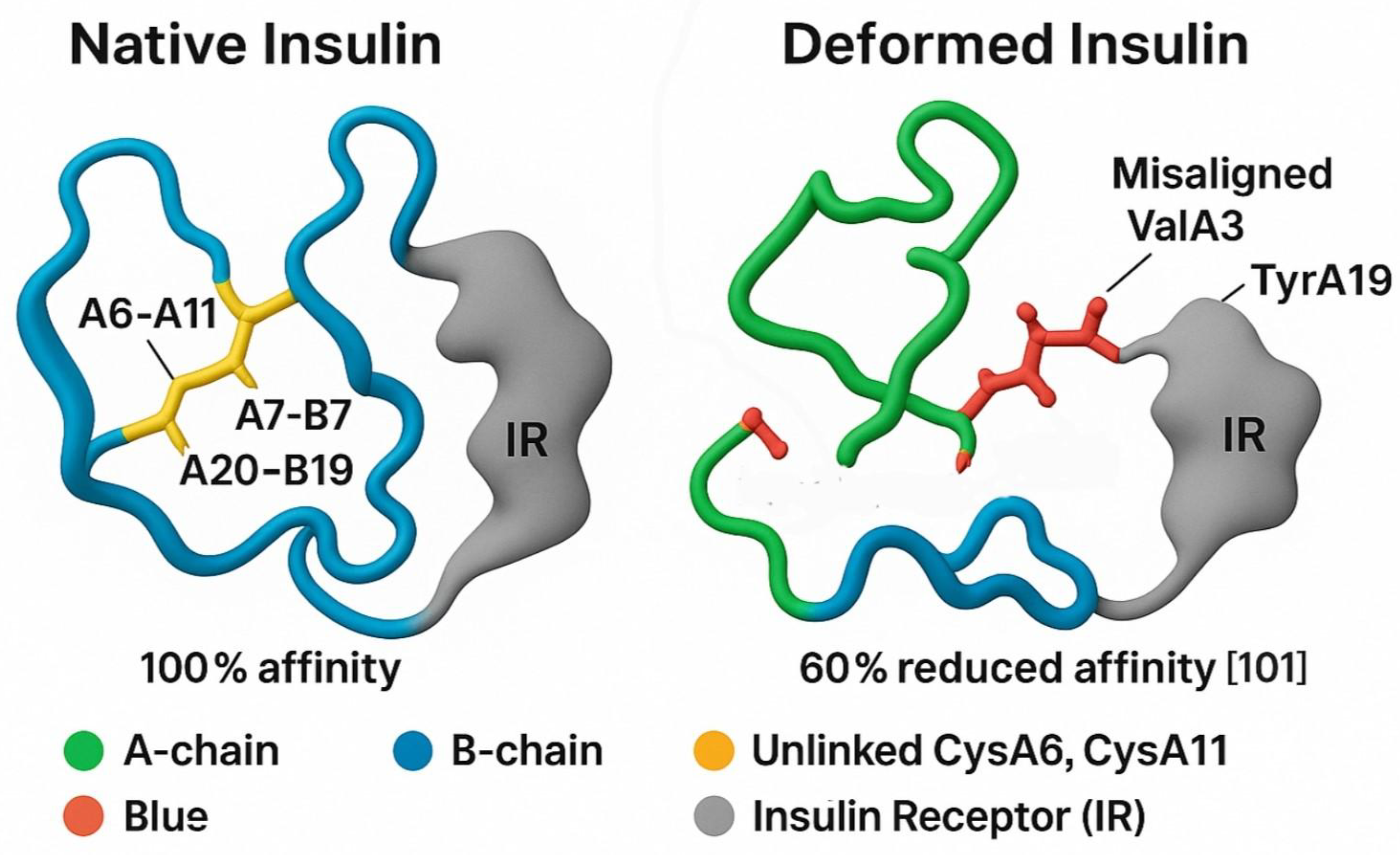

Molecular docking models show that disruption of the A6–A11 disulfide bond misaligns key receptor-binding residues (ValA3, TyrA19), reducing insulin receptor affinity by ~60%, impairing IRS phosphorylation, PI3K-Akt signaling, and GLUT4 translocation, while allowing unchecked hepatic glucose production, driving hyperglycemia (

Figure 2) [

53,

54,

55]. Cysteine deficiency also reduces glutathione synthesis, increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activating nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6) [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

These cytokines induce c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-mediated serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 (Ser307), further disrupting PI3K-Akt signaling, while impaired thioredoxin and peroxiredoxin function exacerbates oxidative stress [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65]. Sulfur deficiency exacerbates metabolic dysregulation through ER stress and immunological cascades. Cysteine scarcity limits PDI activity, causing misfolded insulin to accumulate in the ER, triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) via sensors inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) [

66,

67]. Chronic ER stress activates pro-apoptotic pathways through IRE1/PERK-mediated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein, leading to beta-cell apoptosis and reduced insulin secretion [

66,

67,

68,

69]. Misfolded insulin aggregates further contribute to glucotoxicity, a hallmark of T2DM [

70,

71]. Immunologically, reduced cysteine impairs glutathione synthesis, a critical antioxidant, increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activating nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6) [

56,

60,

72,

73,

74]. These cytokines induce JNK-mediated serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 (Ser307), disrupting PI3K-Akt signaling [

61,

62].

Sulfur deficiency also impairs redox-regulatory proteins thioredoxin and peroxiredoxin, reliant on disulfide bonds, perpetuating oxidative stress [

63,

64]. Additionally, reduced mucin synthesis weakens gut barrier integrity, enabling lipopolysaccharide translocation and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated endotoxemia, amplifying systemic inflammation [

65,

75,

76,

77]. By elucidating the gut-mitochondria-sulfur-insulin axis, this hypothesis challenges peripheral-focused T2DM models, positioning sulfur metabolism as a therapeutic target to restore insulin functionality and mitigate disease progression.

5. Targeting Sulfur Homeostasis: A Revolutionary Therapeutic Approach for Type 2 Diabetes

The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis paves the way for innovative therapeutic strategies to combat insulin resistance by restoring sulfur homeostasis, addressing the molecular and immunological roots of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a cysteine precursor, enhances glutathione synthesis, a critical antioxidant tripeptide formed via glutamate-cysteine ligase and glutathione synthetase, neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced by mitochondrial dysfunction [

78,

79,

80]. By bolstering cysteine availability, NAC supports protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) activity in the endoplasmic reticulum, ensuring proper formation of insulin’s disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19), stabilizing its functional conformation, and reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress from misfolded insulin accumulation [

81].

At the molecular level, NAC inhibits c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), a stress kinase activated by ROS and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) at serine residues, disrupting phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (Akt) signaling [

82,

83]. By suppressing JNK, NAC restores IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, enhancing PI3K-Akt signaling and glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation, thus improving glucose uptake [

84]. Immunologically, NAC reduces nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) activation, downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and suppressor of cytokine signaling proteins, mitigating insulin resistance [

85]. Additionally, NAC reinforces gut barrier integrity by stabilizing redox-dependent tight junction proteins (e.g., occludin, zonula occludens-1), reducing lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced endotoxemia via toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling [

86,

87]. Complementing NAC, methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), a bioavailable sulfur donor, supports cysteine synthesis by enhancing cystathionine β-synthase and γ-lyase activity in the transsulfuration pathway, counteracting mitochondrial ATP deficits [

88]. Increased cysteine availability bolsters glutathione production and PDI function, stabilizing insulin structure and improving receptor-binding affinity. MSM also inhibits NF-κB activation, reducing cytokine-driven insulin resistance, and enhances gut barrier function, attenuating TLR4-mediated systemic inflammation [

89]. Recommended dosages, under medical supervision, range from 600–1200 mg/day for NAC and 1000–3000 mg/day for MSM to optimize efficacy and safety [

90]. Within the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis, NAC and MSM target insulin misfolding, endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative damage, and systemic inflammation, offering a groundbreaking approach to restore metabolic homeostasis and redefine type 2 diabetes treatment by addressing its sulfur-dependent molecular origins [

78,

90].

6. Compelling Evidence Supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis

6.1. Clinical and Biochemical Evidence: Cysteine Deficiency and Redox Imbalance

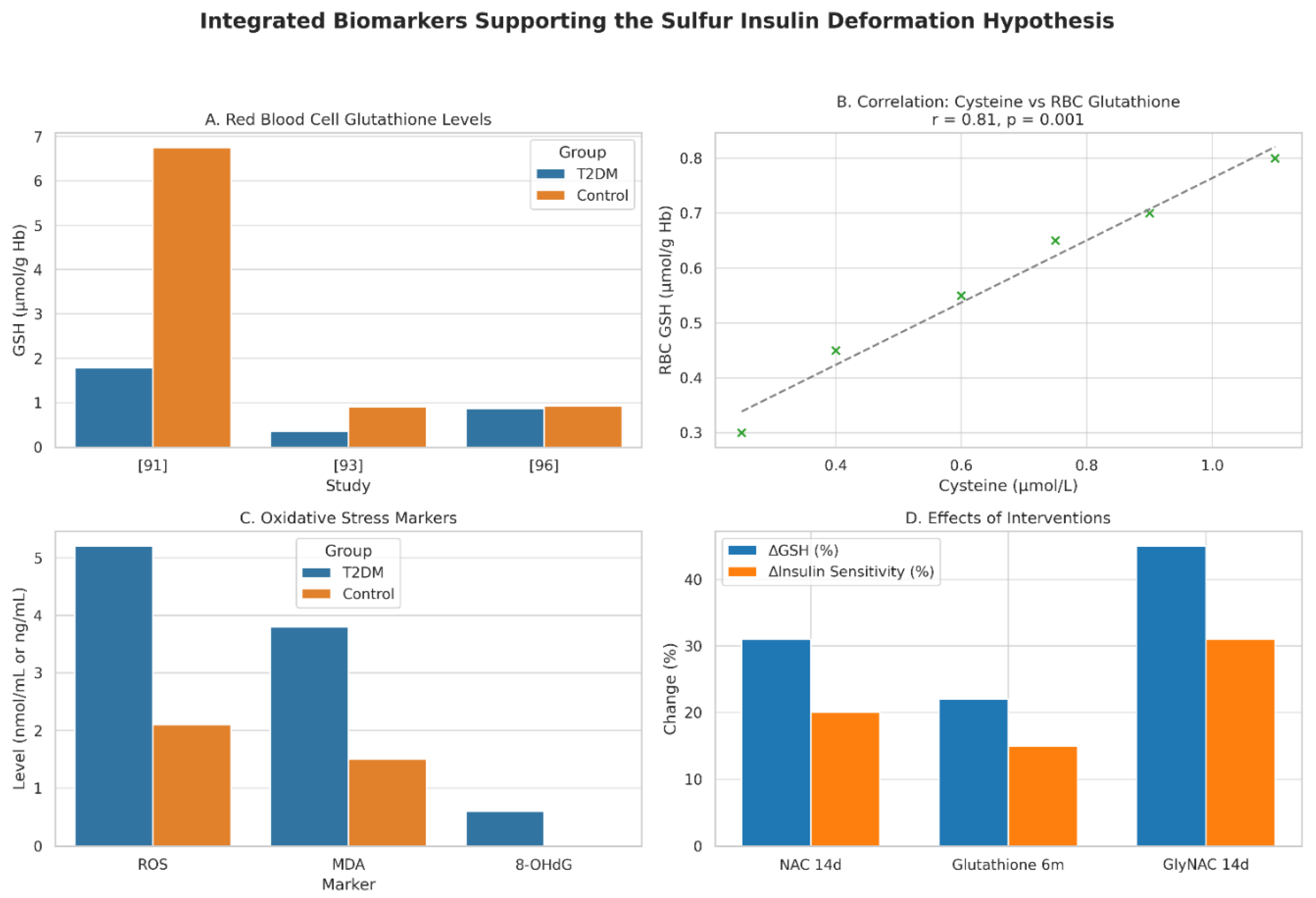

The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis is bolstered by compelling evidence linking cysteine deficiency and impaired glutathione synthesis to insulin misfolding and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) pathogenesis, emphasizing the critical role of disulfide bonds in insulin’s structural and functional integrity. A 2011 study of 12 T2DM patients (HbA1c >7%) revealed a 73.8% reduction in red blood cell (RBC) glutathione (1.78 ± 0.28 vs. 6.75 ± 0.47 µmol/g Hb, P < 0.001) and lower plasma cysteine/glycine levels compared to controls, driven by impaired de novo synthesis and heightened oxidative stress (elevated ROS and lipid peroxides). N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and glycine supplementation for 14 days restored glutathione, reducing oxidative stress and supporting the hypothesis that cysteine scarcity disrupts insulin’s disulfide bonds [

91].

A 2014 study of 79 T2DM patients confirmed reduced cysteine and glutathione levels, with a strong correlation (r = 0.81, P = 0.001) and an inverse relationship with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, r = -0.65, P < 0.05). In vitro, cysteine supplementation in hyperglycemic U937 monocytes restored glutamate-cysteine ligase expression and glutathione, enhanced by vitamin D, suggesting cysteine’s role in counteracting sulfur-dependent insulin dysfunction [

92]. In 2018, 16 T2DM patients (seven without, nine with microvascular complications) showed lower glutathione levels (0.35 ± 0.30 vs. 0.90 ± 0.42 mmol/L, P < 0.01) and synthesis rates (0.50 ± 0.69 vs. 1.03 ± 0.55 mmol/L/day, P < 0.05), particularly in complicated cases, driven by cysteine deficiency and elevated ROS, underscoring sulfur’s role in insulin structural integrity [

93]. A 2022 randomized trial of 250 T2DM patients showed that six months of oral glutathione supplementation increased plasma glutathione, reduced 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG, P < 0.01), and improved HbA1c and insulin sensitivity, especially in patients over 55, indicating age-related glutathione deficits amplify sulfur-based therapeutic benefits [

94]. A 2022 pilot study using GlyNAC (glycine + NAC) in T2DM patients over 14 days increased RBC glutathione (P < 0.01), improved insulin sensitivity by 31% (P < 0.05), and enhanced mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, confirming cysteine’s role in restoring sulfur homeostasis and insulin functionality [

95].

Contrarily, a 2016 study found a non-significant RBC glutathione reduction (0.87 vs. 0.92 µmol/L) but impaired glutathione peroxidase activity (P < 0.05) and elevated malondialdehyde, suggesting increased glutathione consumption under oxidative stress, which may disrupt insulin folding [

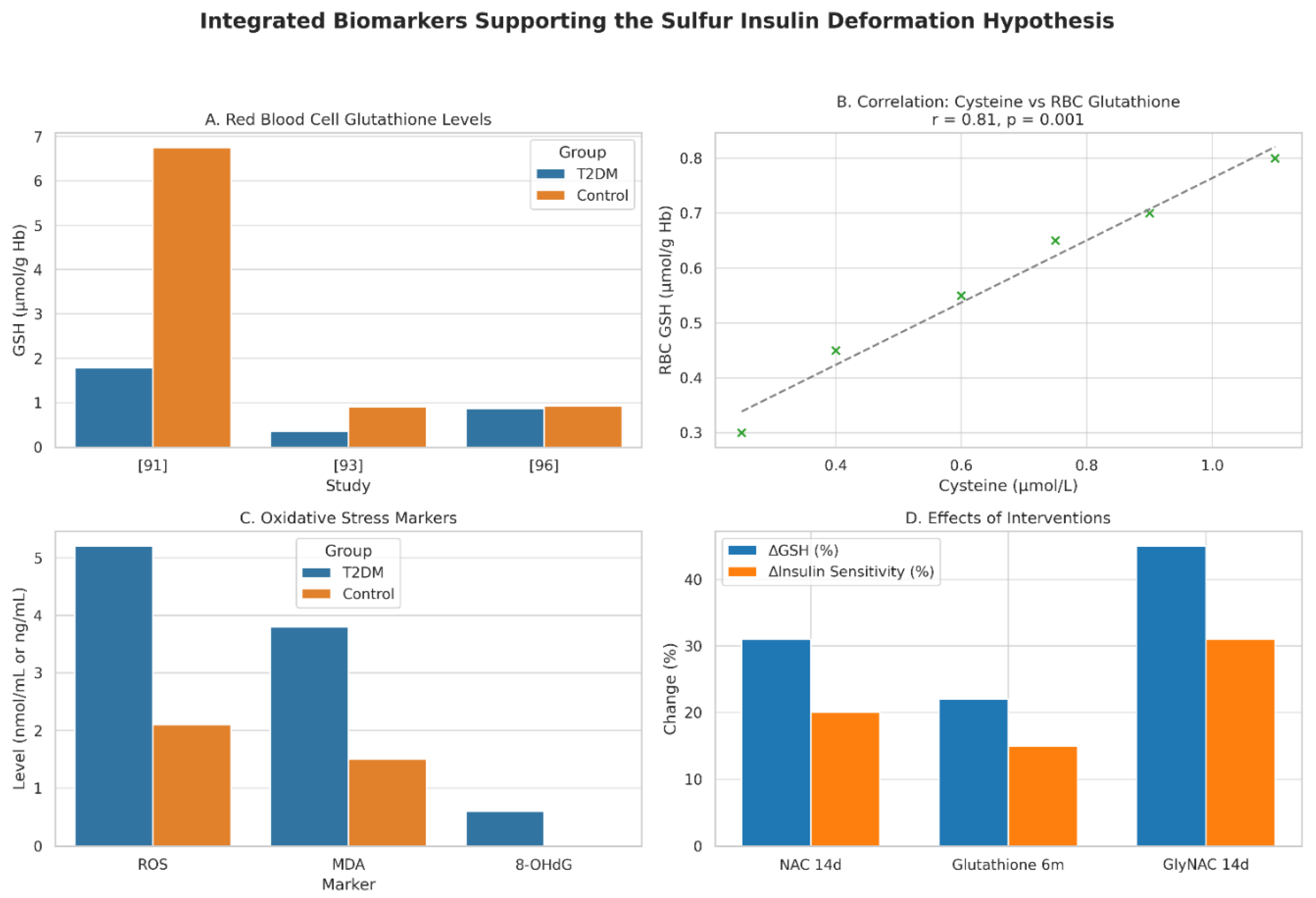

96]. These studies collectively demonstrate that T2DM is marked by 30–73.8% reductions in cysteine and glutathione, driven by impaired synthesis and oxidative stress, fostering a redox environment that impairs insulin’s disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19), critical for its structural stability and receptor binding (

Figure 3).

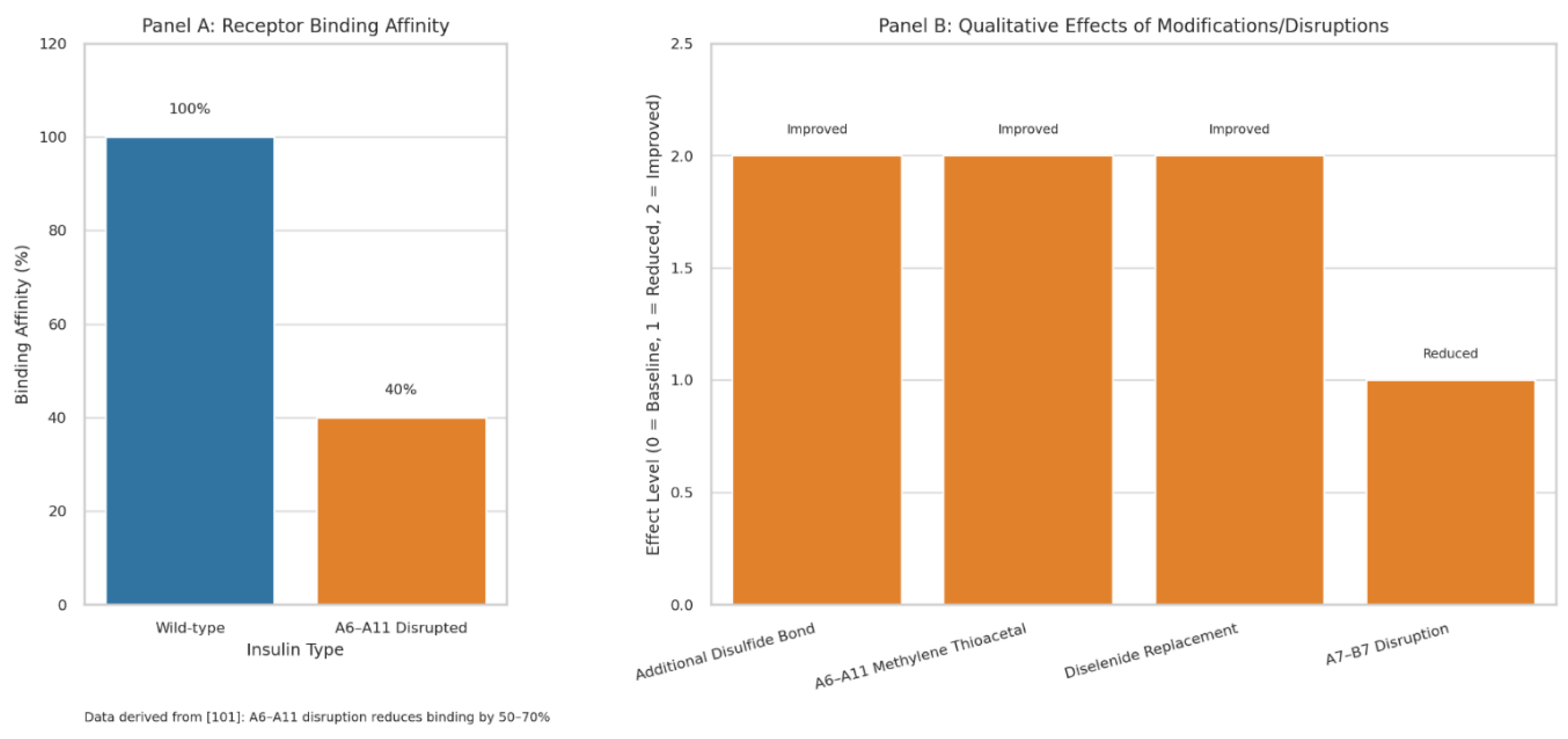

6.2. Structural Impact: Disulfide Bond Disruption and Insulin Misfolding

Insulin’s three disulfide bonds dynamically regulate its folding, stability, and bioactivity. These bonds constrain conformational flexibility, protect against degradation, and enable receptor activation [

97].

Engineering an additional disulfide bond enhanced insulin’s stability without compromising bioactivity, reinforcing its hydrophobic core [

98]. The A6–A11 bond acts as a dynamic hinge, aligning residues (e.g., ValA3, TyrA19) for receptor docking; its disruption in synthetic analogs reduced binding affinity by 50–70%, supporting the hypothesis that sulfur deficiency-induced misfolding impairs insulin function [

99,

100,

101]. Replacing A6–A11 with a methylene thioacetal or diselenide improved foldability and resistance to reductive cleavage, maintaining the A-chain’s α-helical structure [

102,

103,

104].

Mutations disrupting A7–B7 reduced receptor affinity and PI3K-Akt signaling, critical for glucose uptake, aligning with the hypothesis that disulfide bond deformations drive metabolic dysfunction [

105].

Restoring sulfur homeostasis with NAC or similar compounds could stabilize these bonds, offering a novel therapeutic avenue for T2DM (

Figure 4)

Figure 2.

Molecular Docking Model of Native vs. Deformed Insulin with Insulin Receptor. This figure illustrates the structural and functional impact of disulfide bond integrity on insulin-receptor interactions, supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis. Panel A (Native Insulin) depicts the native insulin structure with the A-chain (green) and B-chain (blue) stabilized by disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19, yellow), enabling optimal docking with the insulin receptor (IR, grey) at 100% affinity. Panel B (Deformed Insulin) highlights the consequences of sulfur deficiency, showing the absence of the A6–A11 disulfide bond (indicated as unlinked CysA6, CysA11 in yellow), leading to A-chain misfolding (green). This results in misaligned receptor-binding residues ValA3 and TyrA19 (red), impairing interaction with IR and reducing affinity by 60%. [

101] The legend clarifies the color scheme: green (A-chain), blue (B-chain), yellow (unlinked CysA6, CysA11), red (ValA3, TyrA19), grey (Insulin Receptor, IR). The caption below reads: “Deformation-induced misalignment of ValA3 and TyrA19 impairs insulin receptor binding, supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation,” reinforcing the hypothesis that sulfur deficiency disrupts insulin folding and receptor binding, contributing to insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2.

Molecular Docking Model of Native vs. Deformed Insulin with Insulin Receptor. This figure illustrates the structural and functional impact of disulfide bond integrity on insulin-receptor interactions, supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis. Panel A (Native Insulin) depicts the native insulin structure with the A-chain (green) and B-chain (blue) stabilized by disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19, yellow), enabling optimal docking with the insulin receptor (IR, grey) at 100% affinity. Panel B (Deformed Insulin) highlights the consequences of sulfur deficiency, showing the absence of the A6–A11 disulfide bond (indicated as unlinked CysA6, CysA11 in yellow), leading to A-chain misfolding (green). This results in misaligned receptor-binding residues ValA3 and TyrA19 (red), impairing interaction with IR and reducing affinity by 60%. [

101] The legend clarifies the color scheme: green (A-chain), blue (B-chain), yellow (unlinked CysA6, CysA11), red (ValA3, TyrA19), grey (Insulin Receptor, IR). The caption below reads: “Deformation-induced misalignment of ValA3 and TyrA19 impairs insulin receptor binding, supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation,” reinforcing the hypothesis that sulfur deficiency disrupts insulin folding and receptor binding, contributing to insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Figure 3.

Integrated Biomarkers Supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis. This figure presents a multi-panel visualization of key biomarkers underpinning the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Panel A displays red blood cell (RBC) glutathione levels, highlighting a significant 73.8% reduction in T2DM patients (1.78 ± 0.28 µmol/g Hb) compared to healthy controls (6.75 ± 0.47 µmol/g Hb, P < 0.001), [

91] with additional data from. [

93] (0.35 ± 0.30 vs. 0.90 ± 0.42 mmol/L, P < 0.01) and [

96] (0.87 vs. 0.92 µmol/L, non-significant). Panel B illustrates a strong positive correlation between plasma cysteine and RBC glutathione levels (r = 0.81, P = 0.001) in 79 T2DM and 22 control subjects, [

92] alongside an inverse correlation with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, r = -0.65, P < 0.05). Panel C depicts elevated oxidative stress markers in T2DM, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), malondialdehyde (MDA), and 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), with significant increases (P < 0.01). [

94,

96] Panel D demonstrates the effects of interventions, showing increased RBC glutathione (e.g., +31% with NAC, P < 0.01 [

95]) and enhanced insulin sensitivity (e.g., +31% with GlyNAC, P < 0.05 [

95]) following 14-day or 6-month treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with statistical significance denoted (P < 0.05, P < 0.01). This figure synthesizes evidence of sulfur deficiency’s role in insulin dysfunction, supporting the hypothesis of disulfide bond disruption.

Figure 3.

Integrated Biomarkers Supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis. This figure presents a multi-panel visualization of key biomarkers underpinning the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Panel A displays red blood cell (RBC) glutathione levels, highlighting a significant 73.8% reduction in T2DM patients (1.78 ± 0.28 µmol/g Hb) compared to healthy controls (6.75 ± 0.47 µmol/g Hb, P < 0.001), [

91] with additional data from. [

93] (0.35 ± 0.30 vs. 0.90 ± 0.42 mmol/L, P < 0.01) and [

96] (0.87 vs. 0.92 µmol/L, non-significant). Panel B illustrates a strong positive correlation between plasma cysteine and RBC glutathione levels (r = 0.81, P = 0.001) in 79 T2DM and 22 control subjects, [

92] alongside an inverse correlation with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, r = -0.65, P < 0.05). Panel C depicts elevated oxidative stress markers in T2DM, including reactive oxygen species (ROS), malondialdehyde (MDA), and 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), with significant increases (P < 0.01). [

94,

96] Panel D demonstrates the effects of interventions, showing increased RBC glutathione (e.g., +31% with NAC, P < 0.01 [

95]) and enhanced insulin sensitivity (e.g., +31% with GlyNAC, P < 0.05 [

95]) following 14-day or 6-month treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SD, with statistical significance denoted (P < 0.05, P < 0.01). This figure synthesizes evidence of sulfur deficiency’s role in insulin dysfunction, supporting the hypothesis of disulfide bond disruption.

6.3. Molecular Pathways: PDI Dysregulation, ER Stress and Inflammatory Signaling

The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis, which posits that insulin misfolding due to sulfur deficiency and disrupted disulfide bond formation drives insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), is further substantiated by recent studies elucidating the molecular interplay between endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) activity, and sulfur-dependent pathways in metabolic dysfunction. A cross-sectional study of 553 adults demonstrated significantly elevated serum levels of protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 4 (PDIA4) in 225 newly diagnosed T2DM patients compared to 159 individuals with normal glucose tolerance (P < 0.001), with PDIA4 levels showing strong positive correlations with fasting plasma glucose (r = 0.62, P < 0.01), body mass index (r = 0.58, P < 0.01), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (r = 0.55, P < 0.05), and a robust inverse correlation with insulin sensitivity (r = -0.67, P < 0.01) [

106].

This upregulation of PDIA4, essential for catalyzing disulfide bond formation (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19), likely reflects a compensatory response to ER stress triggered by cysteine scarcity, which impairs insulin’s structural integrity and receptor-binding affinity. In palmitate-induced insulin resistance in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells, PDIA4 overexpression increased inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) by 2.5-fold (P < 0.01), while PDIA4 knockdown reduced insulin resistance by 40% (P < 0.05) and inflammation, with metformin decreasing PDIA4 expression by 35% (P < 0.05), thereby restoring phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling and glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation [

107]. Similarly, in db/db mice, the PDIA4 inhibitor PS1 (IC50 = 4 μM) reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by 50% (P < 0.01) by inhibiting PDIA4 interactions with Ndufs3 and p22 in the electron transport chain complex 1 (ETC C1) and NADPH oxidase (Nox) pathways, improving glucose tolerance, reducing HbA1c by 1.2% (P < 0.05), and enhancing β-cell survival in Min6 cells by 30% (P < 0.05) [

108].

Aberrant S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues, which competes with disulfide bond formation, further disrupts insulin signaling by reducing cysteine thiol availability, impairing insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) tyrosine phosphorylation and exacerbating insulin resistance in target tissues [

109]. Additionally, a study of 45 middle-aged men with varying BMI revealed that obesity-induced ER stress in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) increased mRNA expression of ER stress markers (GRP78, CHOP, XBP-1), inflammatory markers (TLR2, TLR4, CCR2), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-related markers (APP, PS1, PS2) in obese individuals compared to lean controls (P < 0.05), with high glucose and free fatty acids (FFAs) further inducing these markers in cultured PBMCs, suggesting a mechanistic link between sulfur-dependent ER stress and metabolic complications [

110].

In adipose tissue, single-nucleus RNA sequencing identified a maladaptive macrophage subpopulation (ATF4hiPDIA3hiACSL4hiCCL2hi) where PDIA3, another PDI family member, drives pro-inflammatory and migratory properties via ATF4-mediated transcription and RhoA-YAP signaling, with PDIA3-targeted siRNA-loaded liposomes reducing adipose inflammation and high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice (P < 0.05) [

111]. Furthermore, β-cell-specific deletion of PDIA1 in high-fat diet-fed or aged mice increased the proinsulin/insulin ratio in serum and islets (P < 0.01), exacerbated glucose intolerance, and caused ultrastructural abnormalities, including diminished insulin granule content and ER vesiculation, due to impaired disulfide maturation and heightened oxidative stress, underscoring PDIA1’s role in sulfur-dependent proinsulin folding [

112]. Collectively, these findings reinforce the hypothesis that sulfur deficiency, through compromised cysteine availability, heightened ER stress, and dysregulated PDI activity, disrupts insulin’s disulfide bonds, leading to misfolding, reduced receptor affinity, and metabolic dysfunction, while targeting PDI-mediated pathways and sulfur homeostasis offers a promising therapeutic strategy for T2DM and its comorbidities.

6.4. Extracellular Redox-Mediated Insulin Chain Splitting: Emerging In Vivo Evidence for Disulfide Bond Instability

A 2024 study provides the first experimental evidence of insulin chain splitting in human plasma and in vivo, offering near-direct support for the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis through demonstration of disulfide bond disruption via thiol-disulfide exchange. In human plasma incubated with native human insulin (HI) at 1 µM in 80% EDTA-stabilized plasma and 20% PBS buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C, intact HI disappeared over time (up to 97.5% loss by 169.5 hours), with a corresponding appearance of free A-chain and B-chain, as quantified by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) using exact monoisotopic masses confirming disulfides on all cysteines).

This degradation, occurring at redox potentials typical for human plasma (~ -137 mV for GSH/GSSG), highlights the vulnerability of insulin’s disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19) to extracellular reductive stress, where lower redox potential accelerates splitting by facilitating thiol attacks from low-molecular-weight species like glutathione (GSH) or cysteine.

This human-specific finding underscores the physiological relevance of chain splitting, as the study demonstrated that disulphide exchange leads to formation of free A- and B-chains as well as insulin isomers, with the rate dependent on redox status higher GSH levels (lower potential) promoting splitting, while GSH depletion (higher potential) reduces it. In vivo, during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps in rats infused with HI at 2 nmol/kg/min, plasma levels revealed not only HI but also A-chain, B-chain, and an HI isomer, with A-chain appearance rate estimated at 0.40 nmol/kg/min (~20% of infusion rate, based on A-chain clearance kinetics from a separate pharmacokinetic study: volume of distribution 0.26 L/kg, half-life 1.2 min, clearance 0.14 L/kg/min. 2–3). This substantial degradation emphasizes chain splitting as a redox-modulated pathway in circulation. However, if plasma-mediated chain splitting were the primary driver of insulin resistance, a critical paradox emerges: why does intravenous (IV) insulin therapy remain effective in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients, circulating through the same bloodstream yet maintaining glycemic control without degradation apparently limiting its action? Molecularly, this discrepancy arises from differential exposure and kinetics between endogenous and exogenous insulin. Endogenous insulin, secreted into the portal vein, faces immediate first-pass hepatic clearance (~80%), where locally elevated GSH concentrations (contributing ~31% to plasma GSH supply) amplify thiol-disulfide exchange, potentially cleaving bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19) via reductive attacks before systemic release, reducing bioavailable intact molecules for receptor binding. In contrast, IV insulin administered systemically at supraphysiological doses bypasses this hepatic portal exposure, achieving rapid distribution with minimized transit time in reductive environments, allowing sufficient intact HI to bind the insulin receptor (IR) α-subunit, trigger β-subunit autophosphorylation (Tyr1158/1162/1163), recruit IRS-1, activate PI3K-Akt signaling, and promote GLUT4 translocation for glucose uptake. Even if ~20% splitting occurs, the excess dose compensates, ensuring downstream pathway activation. This paradox suggests that extracellular chain splitting functions as a secondary factor, amplifying resistance rather than initiating it. The primary etiology, as posited by the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis, lies in intracellular structural deformation during insulin biosynthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where sulfur deficiency impairs protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) catalysis, leading to misfolded insulin with aberrant disulfide bonds and inherently reduced receptor affinity (e.g., 50–70% loss from A6–A11 disruption).

From this perspective, the study’s findings can be explained molecularly: misfolded endogenous insulin, already destabilized by incomplete PDI-mediated oxidation of cysteine thiols (dependent on transsulfuration-derived cysteine availability), becomes more susceptible to extracellular thiol attacks in plasma, accelerating chain splitting via facilitated reductive cleavage. Properly folded exogenous HI, produced under controlled conditions without sulfur scarcity, exhibits greater disulfide stability, resisting splitting and explaining its efficacy. Thus, if endogenous insulin is structurally deformed and further degraded in circulation, these results indirectly substantiate the hypothesis by linking redox imbalance rooted in mitochondrial suffocation and cysteine/glutathione depletion to diminished insulin bioavailability, reinforcing the need to target the gut-mitochondria-sulfur axis for both intra- and extracellular mitigation [

113].

7. Limitations

While the Sulfur-Insulin Deformation Hypothesis presents a mechanistically coherent and clinically plausible model for the structural origin of insulin resistance, we acknowledge the current absence of direct structural evidence of endogenous insulin misfolding in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This limitation is primarily due to the technical challenges associated with isolating and characterizing native human insulin particularly under pathophysiological conditions using high-resolution proteomic techniques such as LC-MS/MS, NMR spectroscopy, or Raman scattering.

To date, very few studies have successfully extracted and structurally analyzed circulating human insulin directly from diabetic patients, as most available data derive from recombinant or synthetic analogs. The isolation of low-abundance native insulin from plasma, its purification from structurally similar peptides (e.g., C-peptide), and its conformational profiling remain highly resource-intensive and largely inaccessible in low- and middle-income countries.

Thus, this hypothesis is proposed not as a definitive conclusion but as a strategic framework designed to guide further empirical investigation by research institutions equipped with advanced molecular infrastructure. Future validation should include direct conformational analysis of insulin in T2DM patients under varying redox states, along with targeted interventions aimed at restoring sulfur homeostasis.

8. Discussion

The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis redefines type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) as a sulfur metabolism disorder, positing that insulin misfolding, driven by organic sulfur deficiency from mitochondrial dysfunction in intestinal epithelial cells, is a primary driver of insulin resistance. This model challenges conventional paradigms that attribute T2DM to peripheral signaling defects, such as obesity-induced lipotoxicity or inflammation-driven c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-mediated serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Instead, it centers on the structural integrity of insulin’s three disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19), which are critical for its receptor-binding affinity, conformational stability, and bioactivity [

97,

98,

99,

100,

101]. Mitochondrial dysfunction in intestinal epithelial cells impairs the electron transport chain, reducing ATP production and inhibiting cystathionine β-synthase and γ-lyase in the transsulfuration pathway, leading to a 30–73.8% reduction in cysteine and glutathione levels (RBC glutathione: 1.78 ± 0.28 vs. 6.75 ± 0.47 µmol/g Hb, P < 0.001) [

91]. This cysteine scarcity disrupts protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) activity, particularly PDIA1, PDIA3, and PDIA4, which catalyze disulfide bond formation and isomerization, resulting in insulin misfolding, as evidenced by simulated Raman spectroscopy showing reduced S-S stretching (510–540 cm

−1) in sulfur-deficient states [

45,

46].

Misfolded insulin, with altered tertiary structure, exhibits a 50–70% reduction in receptor-binding affinity (r = -0.65, P < 0.05 for HOMA-IR), impairing tyrosine phosphorylation, IRS-1 recruitment, and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-protein kinase B (PI3K-Akt) signaling, which reduces glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation and promotes hepatic gluconeogenesis via phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase, sustaining hyperglycemia [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

101]. This hypothesis resolves the paradox of hyperinsulinemia coexisting with hyperglycemia in T2DM. While traditional models attribute hyperinsulinemia to compensatory β-cell secretion, they fail to explain the ineffectiveness of endogenous insulin compared to the efficacy of exogenous insulin. Misfolded endogenous insulin, lacking intact disulfide bonds, has diminished bioactivity, whereas exogenous insulin, with native conformation, activates receptors efficiently [

101]. Recent evidence further supports this model, demonstrating that elevated serum PDIA4 levels in 225 T2DM patients compared to 159 controls with normal glucose tolerance (P < 0.001) correlate positively with fasting plasma glucose (r = 0.62, P < 0.01), body mass index (r = 0.58, P < 0.01), and inflammatory markers (r = 0.55, P < 0.05), and inversely with insulin sensitivity (r = -0.67, P < 0.01), suggesting a compensatory upregulation of PDIA4 in response to ER stress induced by sulfur deficiency [

106]. Similarly, β-cell-specific PDIA1 deletion in high-fat diet-fed or aged mice increased the proinsulin/insulin ratio (P < 0.01) and caused ultrastructural abnormalities, including diminished insulin granule content and ER vesiculation, due to impaired disulfide maturation, underscoring PDIA1’s role in sulfur-dependent proinsulin folding [

112]. Immunologically, cysteine deficiency limits glutathione synthesis, increasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activating nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), which upregulates pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) by 2.5-fold in palmitate-induced models (P < 0.01), exacerbating insulin resistance via JNK and suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins [

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

73,

74,

75,

76,

107].

In adipose tissue, a maladaptive macrophage subpopulation (ATF4hiPDIA3hiACSL4hiCCL2hi) drives inflammation via PDIA3-mediated RhoA-YAP signaling, with PDIA3-targeted siRNA-loaded liposomes reducing adipose inflammation and high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice (P < 0.05), highlighting PDI’s role in systemic metabolic dysfunction [

111]. Aberrant S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues, competing with disulfide bond formation, further disrupts insulin signaling by reducing cysteine thiol availability, impairing IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, and exacerbating insulin resistance [

109]. Compromised gut barrier integrity, due to reduced mucin synthesis from cysteine deficiency, amplifies toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated endotoxemia, positioning the gut as a central driver of T2DM [

65,

75,

76]. A study of 45 middle-aged men showed increased mRNA expression of ER stress markers (GRP78, CHOP, XBP-1), inflammatory markers (TLR2, TLR4, CCR2), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)-related markers (APP, PS1, PS2) in obese PBMCs (P < 0.05), linking sulfur-dependent ER stress to metabolic and neurodegenerative comorbidities [

110].

Therapeutically, sulfur donors like N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and GlyNAC restore plasma cysteine and glutathione by 20–40% (P < 0.01), improve insulin sensitivity by 31% (P < 0.05), and enhance mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in T2DM patients [

95]. The PDIA4 inhibitor PS1 (IC50 = 4 μM) reduces ROS by 50% (P < 0.01), improves HbA1c by 1.2% (P < 0.05), and enhances β-cell survival by 30% (P < 0.05) by inhibiting PDIA4 interactions with Ndufs3 and p22 in the electron transport chain complex 1 (ETC C1) and NADPH oxidase (Nox) pathways [

108]. These interventions align with the hypothesis’s emphasis on restoring sulfur homeostasis to stabilize insulin’s disulfide bonds. [

Table 1] compares this hypothesis with traditional models, highlighting its focus on insulin structure and sulfur metabolism. Beyond T2DM, the hypothesis suggests a continuum of sulfur-dependent protein misfolding disorders, including AD, as evidenced by shared ER stress and PDI dysregulation [

110].

The findings from the 2024 investigation into extracellular redox-mediated insulin chain splitting [

113] provide compelling, albeit secondary, evidence supporting the Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis. This study demonstrates that insulin degradation, with up to 97.5% loss in vitro and a 20% degradation rate in vivo (A-chain appearance at 0.40 nmol/kg/min), occurs via thiol-disulfide exchange at plasma redox potentials (~ -137 mV), highlighting a redox-dependent pathway. However, this mechanism is secondary to the primary etiology proposed herein intracellular misfolding due to sulfur deficiency offering direct validation by linking diminished insulin bioavailability to redox imbalance. The notion that plasma-mediated chain splitting is the primary driver of insulin resistance is refuted, as intravenous (IV) insulin therapy remains effective in T2DM patients despite circulating in the same redox environment; if plasma degradation were dominant, all IV insulin would fail, undermining glycemic control.

Instead, the hypothesis posits that endogenous insulin, misfolded during endoplasmic reticulum (ER) biosynthesis due to impaired protein disulfide isomerase (PDIA1, PDIA3, PDIA4) activity from cysteine scarcity, becomes prone to extracellular cleavage. This vulnerability arises from mitochondrial suffocation disrupting transsulfuration, depleting glutathione (GSH) by 30–73.8%, elevating reactive oxygen species (ROS), and accelerating lipid peroxidation, which exacerbates disulfide bond instability (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19). Exogenous insulin, structurally intact under controlled synthesis, resists this secondary degradation, resolving the paradox. Thus, plasma effects amplify, rather than initiate, resistance, reinforcing the need to target the gut-mitochondria-sulfur-insulin axis [

113].

Future studies should employ liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to detect misfolded insulin, metabolomic profiling of sulfur metabolites, and randomized clinical trials to validate the efficacy of NAC, MSM, or PDIA-targeted therapies (e.g., PS1, PDIA3 siRNA). This paradigm, centered on the gut-mitochondria-sulfur-insulin axis, offers a transformative approach to T2DM management and its comorbidities, potentially redefining therapeutic strategies across metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases.

9. Conclusion

The Sulfur Insulin Deformation Hypothesis reimagines type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) as a sulfur metabolism disorder, where mitochondrial dysfunction in intestinal epithelial cells drives cysteine deficiency, destabilizing insulin’s disulfide bonds (A6–A11, A7–B7, A20–B19) and inducing misfolding that impairs receptor-binding efficacy by 50–70%. This structural defect, evidenced by a 73.8% reduction in glutathione levels in T2DM patients, disrupts insulin’s bioactivity, fueling insulin resistance and hyperglycemia despite hyperinsulinemia. Oxidative stress from glutathione depletion and endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction further compromises beta-cell function, perpetuating metabolic disarray. The gut-mitochondria-sulfur-insulin axis emerges as a central driver, challenging conventional peripheral-focused models. Therapeutic interventions like N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and methylsulfonylmethane (MSM), which boost cysteine and glutathione by 20–40%, restore insulin stability and sensitivity, offering a novel strategy to mitigate T2DM. Awaiting validation through LC-MS/MS analysis of insulin structure and clinical trials, this hypothesis heralds a paradigm shift, advocating sulfur-centric therapies to transform T2DM management and potentially extend to other protein misfolding disorders.

Funding information

The authors received no financial support for the research and publication of this article.

Competing interest declaration

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| T2DM |

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| PDI |

Protein Disulfide Isomerase |

| PDIA1 |

Protein Disulfide Isomerase Family A, Member 1 |

| PDIA3 |

Protein Disulfide Isomerase Family A, Member 3 |

| PDIA4 |

Protein Disulfide Isomerase Family A, Member 4 |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| HOMA-IR |

Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| PI3K |

Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| Akt |

Protein Kinase B |

| GLUT4 |

Glucose Transporter Type 4 |

| HbA1c |

Hemoglobin A1c |

| NAC |

N-Acetylcysteine |

| GlyNAC |

Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| TLR4 |

Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| ETC |

Electron Transport Chain |

| JNK |

c-Jun N-terminal Kinase |

| IRS-1 |

Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 |

| IRS-2 |

Insulin Receptor Substrate-2 |

| ER |

Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| UPR |

Unfolded Protein Response |

| IRE1 |

Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1 |

| PERK |

Protein Kinase R-like ER Kinase |

| ATF6 |

Activating Transcription Factor 6 |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| MSM |

Methylsulfonylmethane |

| RBC |

Red Blood Cell |

| LC-MS/MS |

Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| NMR |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| 8-OHdG |

8-Hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine |

| MDA |

Malondialdehyde |

| Nox |

NADPH Oxidase |

| GRP78 |

Glucose-Regulated Protein 78 |

| CHOP |

CCAAT/enhancer-binding Protein Homologous Protein |

| XBP-1 |

X-box Binding Protein 1 |

| TLR2 |

Toll-Like Receptor 2 |

| CCR2 |

C-C Chemokine Receptor Type 2 |

| APP |

Amyloid Precursor Protein |

| PS1 |

Presenilin 1 |

| PS2 |

Presenilin 2 |

| ACSL4 |

Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member 4 |

| CCL2 |

C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 |

| YAP |

Yes-Associated Protein |

| Ndufs3 |

NADH Dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S Protein 3 |

| p22 |

p22phox (a subunit of NADPH oxidase) |

| MeSH |

Medical Subject Headings |

| SANRA |

Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles |

References

- Wei, J.; Fan, L.; He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C.; Zhao, W. The global, regional, and national burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus attributable to low physical activity from 1990 to 2021: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2025, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinther, T.N.; Norrman, M.; Ribel, U.; Huus, K.; Schlein, M.; Steensgaard, D.B.; Pedersen, T.Å.; Pettersson, I.; Ludvigsen, S.; Kjeldsen, T.; Jensen, K.J.; Hubálek, F. Insulin analog with additional disulfide bond has increased stability and preserved activity. Protein Sci 2013, 22, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas, F.; Moreno-Navarrete, J.M. The impact of H2S on obesity-associated metabolic disturbances. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbodio, J.I.; Snyder, S.H.; Paul, B.D. Regulators of the transsulfuration pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stipanuk, M.H.; Ueki, I. Dealing with methionine/homocysteine sulfur: Cysteine metabolism to taurine and inorganic sulfur. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.; Bhattacharya, R.; Mukherjee, P. Hydrogen sulfide signaling in mitochondria and disease. FASEB J 2019, 33, 13098–13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Thapa, P.; Hao, Y.; Ding, N.; Alshahrani, A.; Wei, Q. Protein disulfide isomerases function as the missing link between diabetes and cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal 2022, 37, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakoff, S.J.; Taha, C.; Rose, E.; Marcusohn, J.; Klip, A.; Skolnik, E.Y. The inability of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation to stimulate GLUT4 translocation indicates additional signaling pathways are required for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92, 10247–10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, D.; Naumovski, N.; Heilbronn, L.K.; Abeywardena, M.; O’Callaghan, N.; Lionetti, L.; Luscombe-Marsh, N. Mitochondrial (dys)function and insulin resistance: From pathophysiological molecular mechanisms to the impact of diet. Front Physiol 2019, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masenga, S.K.; Kabwe, L.S.; Chakulya, M.; Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, J.H.M.; Giacca, A. Role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Cells 2020, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S.; Herkenham, M. Toll-like receptor 4 on nonhematopoietic cells sustains CNS inflammation during endotoxemia, independent of systemic cytokines. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.R.; Nair, B.; Kamath, A.J.; Nath, L.R.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Impact of gut microbiota on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma: Pathways, diagnostic opportunities and therapeutic advances. Eur J Med Res 2024, 29, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, P.S.; Kapur, N.; Barrett, T.A.; Theiss, A.L. Mitochondrial function and gastrointestinal diseases. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 21, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerbette, T.; Boudry, G.; Lan, A. Mitochondrial function in intestinal epithelium homeostasis and modulation in diet-induced obesity. Mol Metab 2022, 63, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinti, M.V.; Fink, G.K.; Hathaway, Q.A.; Durr, A.J.; Kunovac, A.; Hollander, J.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: An organ-based analysis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2019, 316, E268–E285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iheagwam, F.N.; Joseph, A.J.; Adedoyin, E.D.; Iheagwam, O.T.; Ejoh, S.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes: Shedding light on a widespread oversight. Pathophysiology 2025, 32, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.H.; Wang, H.C.; Chang, C.J.; Lee, S.Y. Mitochondrial glutathione in cellular redox homeostasis and disease manifestation. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling. Int J Mol Med 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K.; Nakaki, T. Glutathione in cellular redox homeostasis: Association with the excitatory amino acid carrier 1 (EAAC1). Molecules 2015, 20, 8742–8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, J.; Osaki, T.; Soma, Y.; Matsuda, Y. Critical roles of the cysteine-glutathione axis in the production of γ-glutamyl peptides in the nervous system. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 8044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, B.; Kwakye, J.; Ariyo, O.W.; Ghareeb, A.F.A.; Milfort, M.C.; Fuller, A.L.; Khatiwada, S.; Rekaya, R.; Aggrey, S.E. Major oxidative and antioxidant mechanisms during heat stress-induced oxidative stress in chickens. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, H.J.; Smulders, Y. Overview of homocysteine and folate metabolism. With special references to cardiovascular disease and neural tube defects. J Inherit Metab Dis 2011, 34, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, M.; Stahl, S.; Hellmann, H. Vitamin B6 and its role in cell metabolism and physiology. Cells 2018, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, A.A. Multiple roles of haem in cystathionine β-synthase activity: Implications for hemin and other therapies of acute hepatic porphyria. Biosci Rep 2021, 41, BSR20210935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Chen, S.; Yan, G.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Q.; Lin, S.; Zong, Y.; Chang, H.; Yu Chang, A.C.; Wu, Y.; Hou, C. Cystathionine γ-lyase inhibits mitochondrial oxidative stress by releasing H2S nearby through the AKT/NRF2 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1374720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carelli, S.; Ceriotti, A.; Cabibbo, A.; Fassina, G.; Ruvo, M.; Sitia, R. Cysteine and glutathione secretion in response to protein disulfide bond formation in the ER. Science 1997, 277, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Long, Y. Crosstalk between cystine and glutathione is critical for the regulation of amino acid signaling pathways and ferroptosis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingappan, K. NF-κB in oxidative stress. Curr Opin Toxicol 2018, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, J.; Aran, J.M. Reactive oxygen species: Drivers of physiological and pathological processes. J Inflamm Res 2020, 13, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykiotis, G.P.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1: A novel target for the reversal of insulin resistance. Mol Endocrinol 2001, 15, 1864–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Whitley, C.S.; Haribabu, B.; Jala, V.R. Regulation of intestinal barrier function by microbial metabolites. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 11, 1463–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Kell, D.B.; Pretorius, E. The role of lipopolysaccharide-induced cell signalling in chronic inflammation. Chronic Stress 2022, 6, 24705470221076390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbudi, A.; Khairani, S.; Tjahjadi, A.I. Interplay between insulin resistance and immune dysregulation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Implications for therapeutic interventions. ImmunoTargets Ther 2025, 14, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.Y.; Guo, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Duan, S.S.; Feng, Y.M. Peptide models of four possible insulin folding intermediates with two disulfides. Protein Sci 2003, 12, 2412–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinther, T.N.; Kjeldsen, T.B.; Jensen, K.J.; Hubálek, F. The road to the first, fully active and more stable human insulin variant with an additional disulfide bond. J Pept Sci 2015, 21, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil-Ktorza, O.; Rege, N.; Lansky, S.; Shalev, D.E.; Shoham, G.; Weiss, M.A.; Metanis, N. Substitution of an internal disulfide bridge with a diselenide enhances both foldability and stability of human insulin. Chem Eur J 2019, 25, 8513–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C. Kicking off the insulin cascade. Nature 2006, 444, 833–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Jap, E.; Gubbins, B.; Hagemeyer, C.E.; Karas, J.A. Semisynthesis of A6-A11 lactam insulin. J Pept Sci 2024, 30, e3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, K.; Okumura, M.; Lee, Y.H.; Takei, M.; Tsutsumi, H.; Miyakawa, M.; Koizumi, M.; Inaba, K. Diselenide-bond replacement of the external disulfide bond of insulin increases its oligomerization leading to sustained activity. Commun Chem 2023, 6, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wright, J.; Guo, H.; Xiong, Y.; Arvan, P. Proinsulin entry and transit through the endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic beta cells. Vitam Horm 2014, 95, 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.G.; Knight, S.A.B.; Pandey, A.; Yoon, H.; Pain, J.; Pain, D.; Dancis, A. Cysteine desulfurase is regulated by phosphorylation of Nfs1 in yeast mitochondria. Mitochondrion 2018, 40, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, J.V.; Mascarenhas, R.; Ceric, K.; Ballou, D.P.; Banerjee, R. Disease-causing cystathionine β-synthase linker mutations impair allosteric regulation. J Biol Chem 2023, 299, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuhra, K.; Augsburger, F.; Majtan, T.; Szabo, C. Cystathionine-β-synthase: Molecular regulation and pharmacological inhibition. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, N.S.A.; Zahari, S.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Firdaus-Raih, M.; Low, T.Y.; Mohtar, M.A. Functions and mechanisms of protein disulfide isomerase family in cancer emergence. Cell Biosci 2022, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Chiu, J.; Scartelli, C.; Ponzar, N.; Patel, S.; Patel, A.; Ferreira, R.B.; Keyes, R.F.; Carroll, K.S.; Pozzi, N.; Hogg, P.J.; Smith, B.C.; Flaumenhaft, R. Sulfenylation links oxidative stress to protein disulfide isomerase oxidase activity and thrombus formation. J Thromb Haemost 2023, 21, 2137–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Meyts, P.; Sajid, W.; Palsgaard, J.; Theede, A.M.; Gauguin, L.; Aladdin, H.; Whittaker, J. Insulin and IGF-I receptor structure and binding mechanism. In Madame Curie Biosci Database; 2013; p. NBK6192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilden, P.A.; Siddle, K.; Haring, E.; Backer, J.M.; White, M.F.; Kahn, C.R. The role of insulin receptor kinase domain autophosphorylation in receptor-mediated activities. Analysis with insulin and anti-receptor antibodies. J Biol Chem 1992, 267, 13719–13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Báez, A.; Ayala, G.; Pedroza-Saavedra, A.; González-Sánchez, H.M.; Chihu Amparan, L. Phosphorylation codes in IRS-1 and IRS-2 are associated with the activation/inhibition of insulin canonical signaling pathways. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Cheng, H.; Roberts, T.M.; Zhao, J.J. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Somwar, R.; Bilan, P.J.; Liu, Z.; Jin, J.; Woodgett, J.R.; Klip, A. Protein kinase B/Akt participates in GLUT4 translocation by insulin in L6 myoblasts. Mol Cell Biol 1999, 19, 4008–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.W.; Gang, G.T.; Tadi, S.; Nedumaran, B.; Kim, Y.D.; Park, J.H.; Kweon, G.R.; Koo, S.H.; Lee, K.; Ahn, R.S.; Yim, Y.H.; Lee, C.H.; Harris, R.A.; Choi, H.S. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose-6-phosphatase are required for steroidogenesis in testicular Leydig cells. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 41875–41887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; An, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ji, H.; Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol 2023, 14, 1149239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szablewski, L. Changes in cells associated with insulin resistance. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Tian, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, H.; Dong, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J. Signaling pathways and intervention for therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus. MedComm 2023, 4, e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, S.; Tang, C.; Wang, G.; Du, J.; Jin, H. Hydrogen sulfide regulates insulin secretion and insulin resistance in diabetes mellitus, a new promising target for diabetes mellitus treatment? A review. J Adv Res 2020, 27, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.D.; Sbodio, J.I.; Snyder, S.H. Cysteine metabolism in neuronal redox homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2018, 39, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, A.; Mersal, E.A.; Dawood, A.F.; Abd El-Azim, A.O.; Hasan, O.; Alaqidi, R.; Alotaibi, A.; Alshahrani, M.; Alheraiz, A.; Shawky, T.M. Multifaceted cardioprotective potential of reduced glutathione against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via modulating inflammation–oxidative stress axis. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, G.; Zhao, L.; Hou, X.; Liu, Z.; Bao, T.; Yang, F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Fan, X.; Wang, W. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: New insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Li, Q.; Su, J. Oxidative stress induced by nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) dysfunction aggravates chronic inflammation through the NAD+/SIRT3 axis and promotes renal injury in diabetes. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, L.; Aguirre, V.; Kim, J.K.; Shulman, G.I.; Lee, A.; Corbould, A.; Dunaif, A.; White, M.F. Insulin/IGF-1 and TNF-alpha stimulate phosphorylation of IRS-1 at inhibitory Ser307 via distinct pathways. J Clin Invest 2001, 107, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch-Damti, A.; Potashnik, R.; Gual, P.; Le Marchand-Brustel, Y.; Tanti, J.F.; Rudich, A.; Bashan, N. Differential effects of IRS1 phosphorylated on Ser307 or Ser632 in the induction of insulin resistance by oxidative stress. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2463–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.K.; Vitvitsky, V.; Carballal, S.; Seravalli, J.; Banerjee, R. Thioredoxin regulates human mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase at physiologically-relevant concentrations. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 6299–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y.Q.; Chen, Q. Thioredoxin (Trx): A redox target and modulator of cellular senescence and aging-related diseases. Redox Biol 2024, 70, 103032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velloso, L.A.; Folli, F.; Saad, M.J. TLR4 at the crossroads of nutrients, gut microbiota, and metabolic inflammation. Endocr Rev 2015, 36, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, I.; Gaines, K.S.; Hottel, W.J.; Wishy, R.M.; Miller, S.E.; Powers, L.S.; Rutkowski, D.T.; Monick, M.M. Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 inhibits respiratory syncytial virus replication. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 7537–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetz, C.; Zhang, K.; Kaufman, R.J. Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus mechanisms and impact on islet function. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, N.T.; McGrane, A.; Roberts, L.D. Linking the unfolded protein response to bioactive lipid metabolism and signalling in the cell non-autonomous extracellular communication of ER stress. BioEssays 2023, 45, e2300029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Morales-Scheihing, D.; Butler, P.C.; Soto, C. Type 2 diabetes as a protein misfolding disease. Trends Mol Med 2015, 21, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, E.A.; Almeida, D.C.; Roma, L.P.; Ortis, F.; Carpinelli, A.R. Lipotoxicity and β-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: Oxidative stress linked to NADPH oxidase and ER stress. Cells 2021, 10, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, H.; Murakami, S.; Liu, Z.; Sawa, T.; Takahashi, M.; Izumi, Y.; Bamba, T.; Sato, H.; Akaike, T.; Sekine, H.; Motohashi, H. Sulfur metabolic response in macrophage limits excessive inflammatory response by creating a negative feedback loop. Redox Biol 2023, 65, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, F.F.; Chao, T.H.; Huang, S.C.; Cheng, C.H.; Tseng, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.C. Cysteine regulates oxidative stress and glutathione-related antioxidative capacity before and after colorectal tumor resection. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowla, S.N.; Perkins, N.D.; Jat, P.S. Friend or foe: Emerging role of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells in cell senescence. OncoTargets Ther 2013, 6, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termite, F.; Archilei, S.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Petrucci, L.; Viceconti, N.; Iaccarino, R.; Liguori, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miele, L. Gut microbiota at the crossroad of hepatic oxidative stress and MASLD. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guijarro-Muñoz, I.; Compte, M.; Álvarez-Cienfuegos, A.; Álvarez-Vallina, L.; Sanz, L. Lipopolysaccharide activates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway and proinflammatory response in human pericytes. J Biol Chem 2014, 289, 2457–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, U.; Givvimani, S.; Abe, O.A.; Lederer, E.D.; Tyagi, S.C. Cystathionine β-synthase and cystathionine γ-lyase double gene transfer ameliorate homocysteine-mediated mesangial inflammation through hydrogen sulfide generation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011, 300, C155–C163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala-Valencia, A.C.; Velasco-Hidalgo, L.; Martínez-Avalos, A.; Castillejos-López, M.; Torres-Espíndola, L.M. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on cisplatin toxicity: A review of the literature. Biologics 2024, 18, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.C. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1830, 3143–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkuri, K.R.; Mantovani, J.J.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Herzenberg, L.A. N-Acetylcysteine—A safe antidote for cysteine/glutathione deficiency. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2007, 7, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Banaclocha, M. N-Acetyl-cysteine: Modulating the cysteine redox proteome in neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Gon, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Takeshita, I.; Horie, T. N-acetylcysteine attenuates TNF-alpha-induced p38 MAP kinase activation and p38 MAP kinase-mediated IL-8 production by human pulmonary vascular endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol 2001, 132, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Giraud, J.; Davis, R.J.; White, M.F. c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) mediates feedback inhibition of the insulin signaling cascade. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 2896–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, S.R.; Cooper, D.R. Specific protein kinase C isoforms as transducers and modulators of insulin signaling. Mol Genet Metab 2006, 89, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbagi, O.; Taha, M.; Al-Kushi, A.G.; Alobaidy, M.A.; Baokbah, T.A.S.; Sembawa, H.A.; Azher, Z.A.; Obaid, R.; Babateen, O.; Bokhari, B.T.; Qusty, N.F.; Malak, H.A. Ameliorative effect of N-acetylcysteine against 5-fluorouracil-induced cardiotoxicity via targeting TLR4/NF-κB and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Medicina 2025, 61, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Li, C.; Peng, M.; Wang, L.; Zhao, D.; Wu, T.; Yi, D.; Hou, Y.; Wu, G. N-Acetylcysteine improves intestinal function and attenuates intestinal autophagy in piglets challenged with β-conglycinin. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielska, A.; Matyjek, M.; Kwiatkowska, K. TLR4 and CD14 trafficking and its influence on LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021, 78, 1233–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawiak, A.; Kostecka, A. Regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer and their implications in endocrine therapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butawan, M.; Benjamin, R.L.; Bloomer, R.J. Methylsulfonylmethane: Applications and safety of a novel dietary supplement. Nutrients 2017, 9, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Preez, H.N.; Aldous, C.; Kruger, H.G.; Johnson, L. N-Acetylcysteine and other sulfur-donors as a preventative and adjunct therapy for COVID-19. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci 2022, 2022, 4555490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, R.V.; McKay, S.V.; Patel, S.G.; Guthikonda, A.P.; Reddy, V.T.; Balasubramanyam, A.; Jahoor, F. Glutathione synthesis is diminished in patients with uncontrolled diabetes and restored by dietary supplementation with cysteine and glycine. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Micinski, D.; Huning, L.; Quinn, J.; Dupre, J.; Storey, K.B. Vitamin D and L-cysteine levels correlate positively with GSH and negatively with insulin resistance levels in the blood of type 2 diabetic patients. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014, 68, 1148–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutchmansingh, F.K.; Hsu, J.W.; Bennett, F.I.; Badaloo, A.V.; McFarlane-Anderson, N.; Gordon-Strachan, G.M.; Wright-Pascoe, R.A.; Jahoor, F.; Boyne, M.S. Glutathione metabolism in type 2 diabetes and its relationship with microvascular complications and glycemia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalamkar, S.; Acharya, J.; Kolappurath Madathil, A.; Gajjar, V.; Divate, U.; Karandikar-Iyer, S.; Ghaskadbi, S.; Goel, P. Randomized clinical trial of how long-term glutathione supplementation offers protection from oxidative damage and improves HbA1c in elderly type 2 diabetic patients. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuell, D.; Ford, G.; Los, E.; Stone, W. The role of glutathione and its precursors in type 2 diabetes. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, K.; Naskalski, J.W.; Fedak, D.; Pawlica-Gosiewska, D.; Grudzień, U.; Dumnicka, P.; Małecki, M.T.; Solnica, B. Markers of antioxidant defense in patients with type 2 diabetes. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 2352361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lierop, B.; Ong, S.C.; Belgi, A.; Delaine, C.; Andrikopoulos, S.; Haworth, N.L.; Menting, J.G.; Lawrence, M.C.; Forbes, B.E.; Wade, J.D. Insulin in motion: The A6-A11 disulfide bond allosterically modulates structural transitions required for insulin activity. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 17239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 98 Vinther, T.N.; Pettersson, I.; Huus, K.; Schlein, M.; Steensgaard, D.B.; Sørensen, A.; Jensen, K.J.; Kjeldsen, T.; Hubálek, F. Additional disulfide bonds in insulin: Prediction, recombinant expression, receptor binding affinity, and stability. Protein Sci 2015, 24, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosinski, M.A.; Dhayalan, B.; Chen, Y.S.; Chatterjee, D.; Varas, N.; Weiss, M.A. Structural principles of insulin formulation and analog design: A century of innovation. Mol Metab 2021, 52, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.G.; Choi, K.D.; Jang, S.H.; Shin, H.C. Role of disulfide bonds in the structure and activity of human insulin. Mol Cells 2003, 16, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.C.; Belgi, A.; van Lierop, B.; Delaine, C.; Andrikopoulos, S.; MacRaild, C.A.; Norton, R.S.; Haworth, N.L.; Robinson, A.J.; Forbes, B.E. Probing the correlation between insulin activity and structural stability through introduction of the rigid A6–A11 bond. J Biol Chem 2018, 293, 11928–11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubálek, F.; Cramer, C.N.; Helleberg, H.; Johansson, E.; Nishimura, E.; Schluckebier, G.; Steensgaard, D.B.; Sturis, J.; Kjeldsen, T.B. Enhanced disulphide bond stability contributes to the once-weekly profile of insulin icodec. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Karra, P.; VandenBerg, M.A.; Kim, J.H.; Webber, M.J.; Holland, W.L.; Chou, D.H. Synthesis and characterization of an A6-A11 methylene thioacetal human insulin analogue with enhanced stability. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 11437–11443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil-Ktorza, O.; Rege, N.; Lansky, S.; Shalev, D.E.; Shoham, G.; Weiss, M.A.; Metanis, N. Substitution of an internal disulfide bridge with a diselenide enhances both foldability and stability of human insulin. Chem Eur J 2019, 25, 8513–8521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshinaga, T.; Nakatome, K.; Nozaki, J.; Naitoh, M.; Hoseki, J.; Kubota, H.; Nagata, K.; Koizumi, A. Proinsulin lacking the A7-B7 disulfide bond, Ins2Akita, tends to aggregate due to the exposed hydrophobic surface. Biol Chem 2005, 386, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.C.; Hung, Y.J.; Lin, F.H.; Hsieh, C.H.; Lu, C.H.; Chien, C.Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Li, P.F.; Kuo, F.C.; Liu, J.S.; Chu, N.F.; Lee, C.H. Circulating protein disulfide isomerase family member 4 is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin sensitivity, and obesity. Acta Diabetol. 2022, 59, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Chiang, C.F.; Lin, F.H.; Kuo, F.C.; Su, S.C.; Huang, C.L.; Li, P.F.; Liu, J.S.; Lu, C.H.; Hsieh, C.H.; Hung, Y.J.; Shieh, Y.S. PDIA4, a new endoplasmic reticulum stress protein, modulates insulin resistance and inflammation in skeletal muscle. Frontiers in endocrinology 2022, 13, 1053882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.J.; Chen, W.C.; Kuo, T.F.; et al. Pharmacological and mechanistic study of PS1, a Pdia4 inhibitor, in β-cell pathogenesis and diabetes in db/db mice. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2023, 80, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.L.; Premont, R.T.; Stamler, J.S. The manifold roles of protein S-nitrosylation in the life of insulin. Nature reviews. Endocrinology 2022, 18, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, T.; Yu, L.; Qin, L.; et al. Stress kinases, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and Alzheimer’s disease related markers in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from subjects with increased body weight. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 30890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.-H.; Wang, F.-X.; Zhao, J.-W.; Yang, C.-L.; Rong, S.-J.; Lu, W.-Y.; Chen, Q.-J.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.-N.; Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Song, D.-N.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.-L.; Chen, S.-H.; Yang, P.; Xiong, F.; Yu, Q.-L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S.-W.; Sun, F.; Wang, C.-Y. PDIA3 defines a novel subset of adipose macrophages to exacerbate the development of obesity and metabolic disorders. Cell Metabolism 2024, 36, 2262–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.; Pottekat, A.; Poothong, J.; Yong, J.; Lagunas-Acosta, J.; Charbono, A.; Chen, Z.; Scheuner, D.L.; Liu, M.; Itkin-Ansari, P.; Arvan, P.; Kaufman, R.J. PDIA1/P4HB is required for efficient proinsulin maturation and β cell health in response to diet induced obesity. eLife 2019, 8, e44528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, C.N.; Hubálek, F.; Brand, C.L.; et al. Chain splitting of insulin: An underlying mechanism of insulin resistance? npj Metab Health Dis 2024, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).