Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells and Cell Culture

2.2. Cell Stimulation and Viability Assay

2.3. Western Blotting

2.4. VEGF-Determination

2.5. VEGF Determination by Immunohistochemistry in Clinical Samples

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Analysis of Public Gene Expression Databases

2.8. Visualisation of Interactions Using Cytoscape

2.9. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

3. Results

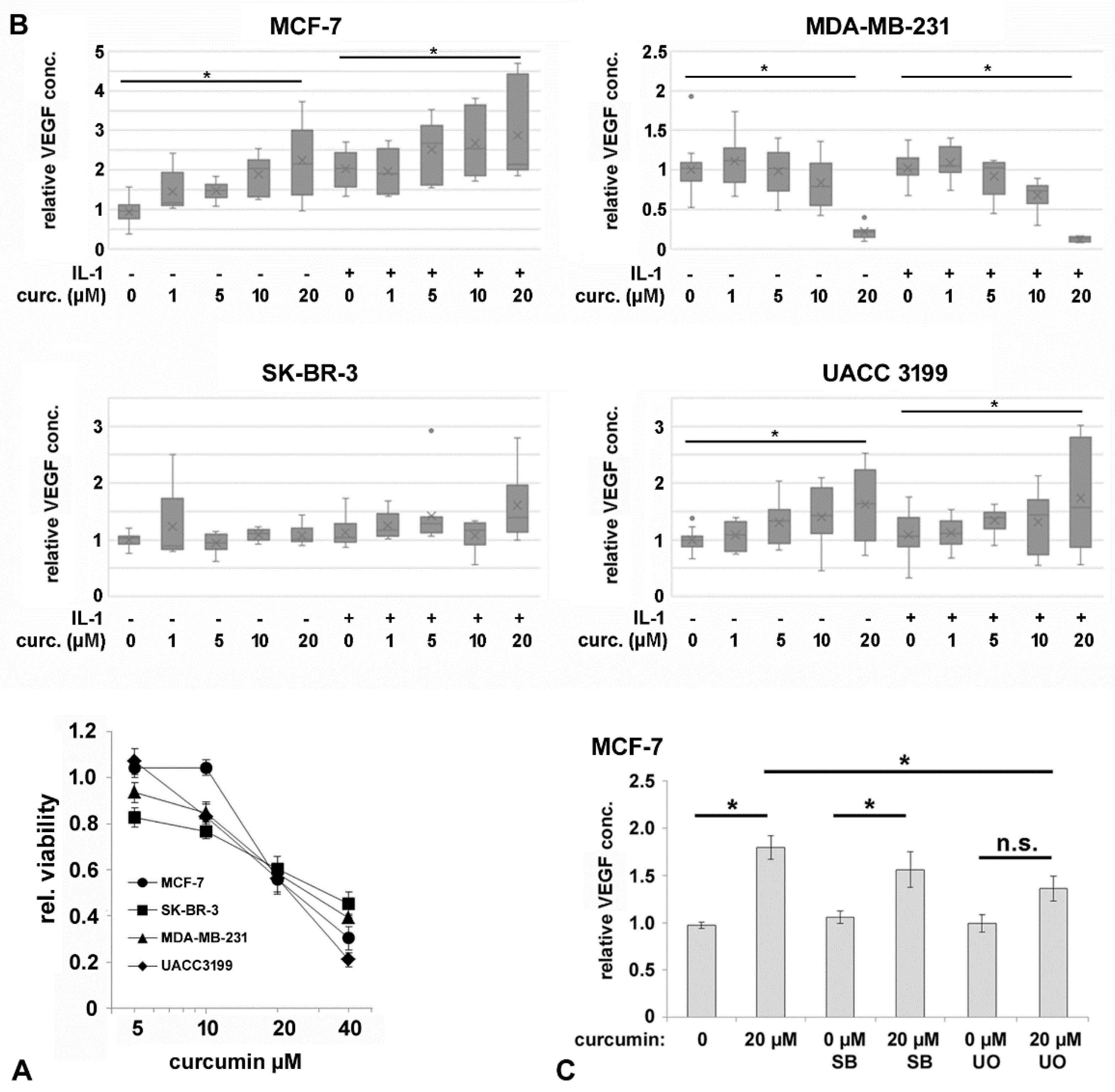

3.1. VEGF-Secretion by Mammary Carcinoma Cell Lines

3.2. VEGF-Expression in Tumor Tissue Samples

3.3. IL-1β Activates NF-kB Signaling in Breast Cancer Cell Lines

3.4. Curcumin Affects IL-1-Mediated Activation of NF-kB and VEGF Secretion

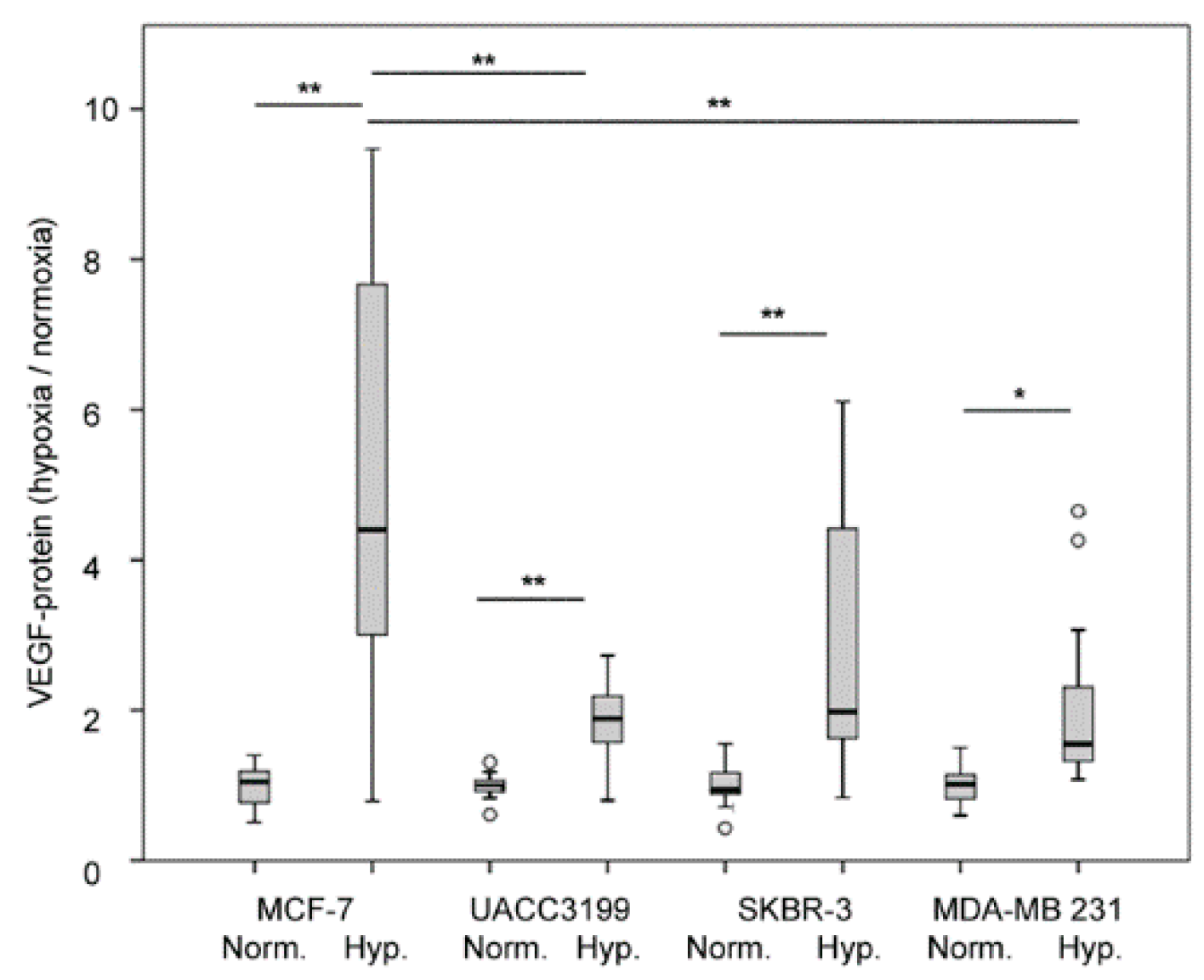

3.5. Effect of Hypoxia on VEGF Secretion

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, L.; Gathani, T. Understanding Breast Cancer as a Global Health Concern. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20211033. [CrossRef]

- Perou, C.M.; Sørlie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; van de Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Rees, C.A.; Pollack, J.R.; Ross, D.T.; Johnsen, H.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Molecular Portraits of Human Breast Tumours. Nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [CrossRef]

- Goldhirsch, A.; Wood, W.C.; Coates, A.S.; Gelber, R.D.; Thürlimann, B.; Senn, H.-J.; Panel members Strategies for Subtypes--Dealing with the Diversity of Breast Cancer: Highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2011, 22, 1736–1747. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M.J.; Harbeck, N.; Nap, M.; Molina, R.; Nicolini, A.; Senkus, E.; Cardoso, F. Clinical Use of Biomarkers in Breast Cancer: Updated Guidelines from the European Group on Tumor Markers (EGTM). Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 2017, 75, 284–298. [CrossRef]

- Anders, C.K.; Abramson, V.; Tan, T.; Dent, R. The Evolution of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: From Biology to Novel Therapeutics. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Meet. 2016, 35, 34–42. [CrossRef]

- Rakha, E.A.; Green, A.R. Molecular Classification of Breast Cancer: What the Pathologist Needs to Know. Pathology (Phila.) 2017, 49, 111–119. [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, H.; Muroi, N.; Hayashi, M.; Harada, O.; Hoshi, K.; Fukuma, E.; Abe, A.; Kubota, K.; Imai, Y. Oestrogen Receptor-Negative/Progesterone Receptor-Positive Phenotype of Invasive Breast Carcinoma in Japan: Re-Evaluated Using Immunohistochemical Staining. Breast Cancer Tokyo Jpn. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R. Aromatase and the Breast: Regulation and Clinical Aspects. Maturitas 2006, 54, 335–341. [CrossRef]

- Buus, R.; Sestak, I.; Kronenwett, R.; Denkert, C.; Dubsky, P.; Krappmann, K.; Scheer, M.; Petry, C.; Cuzick, J.; Dowsett, M. Comparison of EndoPredict and EPclin With Oncotype DX Recurrence Score for Prediction of Risk of Distant Recurrence After Endocrine Therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108. [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Brase, J.C.; Ruiz, A.; Prat, A.; Kronenwett, R.; Calvo, L.; Petry, C.; Bernard, P.S.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Weber, K.E.; et al. Prognostic Ability of EndoPredict Compared to Research-Based Versions of the PAM50 Risk of Recurrence (ROR) Scores in Node-Positive, Estrogen Receptor-Positive, and HER2-Negative Breast Cancer. A GEICAM/9906 Sub-Study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 156, 81–89. [CrossRef]

- Buza, N. The Rapidly Evolving Landscape of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) Testing in Endometrial Carcinoma and Other Gynecologic Malignancies. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Metzger-Filho, O.; Tutt, A.; de Azambuja, E.; Saini, K.S.; Viale, G.; Loi, S.; Bradbury, I.; Bliss, J.M.; Azim, H.A.; Ellis, P.; et al. Dissecting the Heterogeneity of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1879–1887. [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, A.; Riedel, F.; Gondos, A.; Sinn, P.; Schirmacher, P.; Marmé, F.; Jäger, D.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Stieber, A.; Lindel, K.; et al. Prognosis of Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes in Routine Clinical Care: A Large Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 734. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Yadav, D.; Jain, M.; Singh, P.K.; Jin, J.-O. Immunotherapy for Breast Cancer Treatment: Current Evidence and Therapeutic Options. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2022, 22, 212–224. [CrossRef]

- Denkert, C.; von Minckwitz, G.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Lederer, B.; Heppner, B.I.; Weber, K.E.; Budczies, J.; Huober, J.; Klauschen, F.; Furlanetto, J.; et al. Tumour-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Prognosis in Different Subtypes of Breast Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 3771 Patients Treated with Neoadjuvant Therapy. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 40–50. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.P.C.; Benvenuti, T.T.; Honda, S.T.; Valle, P.R.; Katayama, M.L.H.; Brentani, H.P.; Carraro, D.M.; Rozenchan, P.B.; Brentani, M.M.; Lyra, E.C.; et al. Influence of the Interaction between Nodal Fibroblast and Breast Cancer Cells on Gene Expression. Tumor Biol. 2010, 32, 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Liu, Y.; Weng, Y.; Wang, W.; Ren, W.; Fei, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; et al. BMP9 Regulates Cross-Talk between Breast Cancer Cells and Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Cell. Oncol. Dordr. 2014, 37, 363–375. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tulotta, C.; Ottewell, P.D. IL-1β in Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2022, 24, e11. [CrossRef]

- Kalinski, T.; Sel, S.; Hütten, H.; Röpke, M.; Roessner, A.; Nass, N. Curcumin Blocks Interleukin-1 Signaling in Chondrosarcoma Cells. PloS One 2014, 9, e99296. [CrossRef]

- Kalinski, T.; Krueger, S.; Sel, S.; Werner, K.; Ropke, M.; Roessner, A. Differential Expression of VEGF-A and Angiopoietins in Cartilage Tumors and Regulation by Interleukin-1beta. Cancer 2006, 106, 2028–2038. [CrossRef]

- Voronov, E.; Shouval, D.S.; Krelin, Y.; Cagnano, E.; Benharroch, D.; Iwakura, Y.; Dinarello, C.A.; Apte, R.N. IL-1 Is Required for Tumor Invasiveness and Angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 2645–2650. [CrossRef]

- Aalders, K.C.; Tryfonidis, K.; Senkus, E.; Cardoso, F. Anti-Angiogenic Treatment in Breast Cancer: Facts, Successes, Failures and Future Perspectives. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 53, 98–110. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.A.; Hassan, M.K.; Naik, M.; Mohapatra, N.; Balan, P.; Korrapati, P.S.; Dixit, M. EEF1A2 Promotes HIF1A Mediated Breast Cancer Angiogenesis in Normoxia and Participates in a Positive Feedback Loop with HIF1A in Hypoxia. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 184–200. [CrossRef]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Bordoloi, D.; Padmavathi, G.; Monisha, J.; Roy, N.K.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, the Golden Nutraceutical: Multitargeting for Multiple Chronic Diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Mohapatra, P.P.; AlHarbi, S.A.; Jahan, N. Curcumin: Not So Spicy After All. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Peschel, D.; Koerting, R.; Nass, N. Curcumin Induces Changes in Expression of Genes Involved in Cholesterol Homeostasis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2007, 18, 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Jurrmann, N.; Brigelius-Flohé, R.; Böl, G.-F. Curcumin Blocks Interleukin-1 (IL-1) Signaling by Inhibiting the Recruitment of the IL-1 Receptor-Associated Kinase IRAK in Murine Thymoma EL-4 Cells. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1859–1864.

- Fu, Z.; Chen, X.; Guan, S.; Yan, Y.; Lin, H.; Hua, Z.-C. Curcumin Inhibits Angiogenesis and Improves Defective Hematopoiesis Induced by Tumor-Derived VEGF in Tumor Model through Modulating VEGF-VEGFR2 Signaling Pathway. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 19469–19482. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.-M.; Shen, Z.-Z.; Liu, C.-H.; Sartippour, M.R.; Go, V.L.; Heber, D.; Nguyen, M. Curcumin Exerts Multiple Suppressive Effects on Human Breast Carcinoma Cells. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 98, 234–240.

- Carroll, C.E.; Ellersieck, M.R.; Hyder, S.M. Curcumin Inhibits MPA-Induced Secretion of VEGF from T47-D Human Breast Cancer Cells. Menopause N. Y. N 2008, 15, 570–574. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Shah, S.P.; Chin, S.-F.; Turashvili, G.; Rueda, O.M.; Dunning, M.J.; Speed, D.; Lynch, A.G.; Samarajiwa, S.; Yuan, Y.; et al. The Genomic and Transcriptomic Architecture of 2,000 Breast Tumours Reveals Novel Subgroups. Nature 2012, 486, 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Barretina, J.; Caponigro, G.; Stransky, N.; Venkatesan, K.; Margolin, A.A.; Kim, S.; Wilson, C.J.; Lehár, J.; Kryukov, G.V.; Sonkin, D.; et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Enables Predictive Modelling of Anticancer Drug Sensitivity. Nature 2012, 483, 603–607. [CrossRef]

- Nass, N.; Brömme, H.-J.; Hartig, R.; Korkmaz, S.; Sel, S.; Hirche, F.; Ward, A.; Simm, A.; Wiemann, S.; Lykkesfeldt, A.E.; et al. Differential Response to α-Oxoaldehydes in Tamoxifen Resistant MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. PloS One 2014, 9, e101473. [CrossRef]

- Ruhs, S.; Nass, N.; Somoza, V.; Friess, U.; Schinzel, R.; Silber, R.-E.; Simm, A. Maillard Reaction Products Enriched Food Extract Reduce the Expression of Myofibroblast Phenotype Markers. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 488–495. [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, A.; Ignatov, T.; Weissenborn, C.; Eggemann, H.; Bischoff, J.; Semczuk, A.; Roessner, A.; Costa, S.D.; Kalinski, T. G-Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor GPR30 and Tamoxifen Resistance in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 128, 457–466. [CrossRef]

- Remmele, W.; Hildebrand, U.; Hienz, H.A.; Klein, P.J.; Vierbuchen, M.; Behnken, L.J.; Heicke, B.; Scheidt, E. Comparative Histological, Histochemical, Immunohistochemical and Biochemical Studies on Oestrogen Receptors, Lectin Receptors, and Barr Bodies in Human Breast Cancer. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1986, 409, 127–147.

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, pl1. [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J.N.; Myers, T.G.; O’Connor, P.M.; Friend, S.H.; Fornace, A.J.; Kohn, K.W.; Fojo, T.; Bates, S.E.; Rubinstein, L.V.; Anderson, N.L.; et al. An Information-Intensive Approach to the Molecular Pharmacology of Cancer. Science 1997, 275, 343–349.

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, P.; Kalinski, T.; Mahotka, C.; Schmitz, M.; Déjosez, M.; Gabbert, H.E.; Gerharz, C.D. Paclitaxel/Taxol Sensitivity in Human Renal Cell Carcinoma Is Not Determined by the P53 Status. Cancer Lett. 2005, 222, 165–171. [CrossRef]

- Nass, N.; Walter, S; Jechorek, D; Weissenborn, C; Ignatov, A.; Haybaeck, J; Kalinski, T. High Neuronatin (NNAT) Expression Is Associated with Poor Outcome in Breast Cancer. Virchows Arch. 2017, 471(1), 23–30.

- Nass, N.; Ignatov, A.; Andreas, L.; Weißenborn, C.; Kalinski, T.; Sel, S. Accumulation of the Advanced Glycation End Product Carboxymethyl Lysine in Breast Cancer Is Positively Associated with Estrogen Receptor Expression and Unfavorable Prognosis in Estrogen Receptor-Negative Cases. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Scheifele, C.; Zhu, Q.; Ignatov, A.; Kalinski, T.; Nass, N. Glyoxalase 1 Expression Analysis by Immunohistochemistry in Breast Cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020, 216, 153257. [CrossRef]

- Czapiewski, P.; Cornelius, M.; Hartig, R.; Kalinski, T.; Haybaeck, J.; Dittmer, A.; Dittmer, J.; Ignatov, A.; Nass, N. BCL3 Expression Is Strongly Associated with the Occurrence of Breast Cancer Relapse under Tamoxifen Treatment in a Retrospective Cohort Study. Virchows Arch. Int. J. Pathol. 2022, 480, 529–541. [CrossRef]

- Győrffy, B. Integrated Analysis of Public Datasets for the Discovery and Validation of Survival-Associated Genes in Solid Tumors. Innov. Camb. Mass 2024, 5, 100625. [CrossRef]

- Cuenda, A.; Rouse, J.; Doza, Y.N.; Meier, R.; Cohen, P.; Gallagher, T.F.; Young, P.R.; Lee, J.C. SB 203580 Is a Specific Inhibitor of a MAP Kinase Homologue Which Is Stimulated by Cellular Stresses and Interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995, 364, 229–233.

- Favata, M.F.; Horiuchi, K.Y.; Manos, E.J.; Daulerio, A.J.; Stradley, D.A.; Feeser, W.S.; Van Dyk, D.E.; Pitts, W.J.; Earl, R.A.; Hobbs, F.; et al. Identification of a Novel Inhibitor of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 18623–18632.

- Nass, N.; Sel, S.; Ignatov, A.; Roessner, A.; Kalinski, T. Oxidative Stress and Glyoxalase-1 Activity Mediate Dicarbonyl Toxicity in MCF-7 Mamma Carcinoma Cells and a Tamoxifen Resistant Derivative. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016. [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, G.; Toi, M.; Gion, M.; Verderio, P.; Dittadi, R.; Hanatani, M.; Matsubara, I.; Vinante, O.; Bonoldi, E.; Boracchi, P.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Protein in Node-Negative Breast Carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997, 89, 139–147.

- Ludovini, V.; Sidoni, A.; Pistola, L.; Bellezza, G.; Angelis, V.D.; Gori, S.; Mosconi, A.M.; Bisagni, G.; Cherubini, R.; Bian, A.R.; et al. Evaluation of the Prognostic Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Microvessel Density in Stages I and II Breast Cancer Patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003, 81, 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, J.; Gast, K.; Quiroga, D.; Lustberg, M.; Williams, N. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Promising Prognostic Biomarkers Currently in Development. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2021, 21, 135–148. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Xing, Z.; Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Qin, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy in Breast Cancer: Molecular Pathway, Potential Targets, and Current Treatment Strategies. Cancer Lett. 2021, 520, 422–433. [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, N.M.; Jaradat, S.K.; Al-Shami, K.M.; Alkhalifa, A.E. Targeting Angiogenesis in Breast Cancer: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives of Novel Anti-Angiogenic Approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Wang, M.; Gralow, J.; Dickler, M.; Cobleigh, M.; Perez, E.A.; Shenkier, T.; Cella, D.; Davidson, N.E. Paclitaxel plus Bevacizumab versus Paclitaxel Alone for Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2666–2676. [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Brown, J.; Parmar, M.; Toi, M.; Suter, T.; Steger, G.G.; Pivot, X.; Mackey, J.; Jackisch, C.; Dent, R.; et al. Final Efficacy and Updated Safety Results of the Randomized Phase III BEATRICE Trial Evaluating Adjuvant Bevacizumab-Containing Therapy in Triple-Negative Early Breast Cancer. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Huang, R.; Rong, Q.; Yang, W.; Shen, X.; Sun, Q.; Shu, D.; Jiang, K.; Xue, C.; Peng, J.; et al. Bevacizumab, Tislelizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel for Previously Untreated Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Phase II Trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011314. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, H. Hypoxia and Cancer Cell Metabolism. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2014, 46, 214–219. [CrossRef]

- Carmi, Y.; Voronov, E.; Dotan, S.; Lahat, N.; Rahat, M.A.; Fogel, M.; Huszar, M.; White, M.R.; Dinarello, C.A.; Apte, R.N. The Role of Macrophage-Derived IL-1 in Induction and Maintenance of Angiogenesis. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 2009, 183, 4705–4714. [CrossRef]

- Carmi, Y.; Dotan, S.; Rider, P.; Kaplanov, I.; White, M.R.; Baron, R.; Abutbul, S.; Huszar, M.; Dinarello, C.A.; Apte, R.N.; et al. The Role of IL-1β in the Early Tumor Cell–Induced Angiogenic Response. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 3500–3509. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Han, J.; Nam, S.J.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S. Elevated IL-1β Expression Induces Invasiveness of Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells and Is Suppressed by Zerumbone. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 258, 126–133. [CrossRef]

- Holen, I.; Lefley, D.V.; Francis, S.E.; Rennicks, S.; Bradbury, S.; Coleman, R.E.; Ottewell, P. IL-1 Drives Breast Cancer Growth and Bone Metastasis in Vivo. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 75571–75584. [CrossRef]

- Tulotta, C.; Lefley, D.V.; Moore, C.K.; Amariutei, A.E.; Spicer-Hadlington, A.R.; Quayle, L.A.; Hughes, R.O.; Ahmed, K.; Cookson, V.; Evans, C.A.; et al. IL-1B Drives Opposing Responses in Primary Tumours and Bone Metastases; Harnessing Combination Therapies to Improve Outcome in Breast Cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 95. [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M.; Moneo, M.V.; Carnero, A.; Benitez, J.; Martínez-Delgado, B. Mitotic Catastrophe Cell Death Induced by Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor in BRCA1-Deficient Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 2358–2366. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, B.D.; Bauer, J.A.; Chen, X.; Sanders, M.E.; Chakravarthy, A.B.; Shyr, Y.; Pietenpol, J.A. Identification of Human Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Subtypes and Preclinical Models for Selection of Targeted Therapies. J. Clin. Invest. 2011, 121, 2750–2767. [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Barbieri, A.; Palma, G.; Rea, D.; Luciano, A.; D’Aiuto, M.; Arra, C.; Izzo, F. Dissecting the Role of Curcumin in Tumour Growth and Angiogenesis in Mouse Model of Human Breast Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 878134. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.C.; Arbab, A.S.; Jardim-Perassi, B.V.; Borin, T.F.; Varma, N.R.S.; Iskander, A.S.M.; Shankar, A.; Ali, M.M.; Zuccari, D.A.P. de C. Effect of Curcumin on Pro-Angiogenic Factors in the Xenograft Model of Breast Cancer. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 1285–1296.

- Liu, Q.; Loo, W.T.Y.; Sze, S.C.W.; Tong, Y. Curcumin Inhibits Cell Proliferation of MDA-MB-231 and BT-483 Breast Cancer Cells Mediated by down-Regulation of NFkappaB, cyclinD and MMP-1 Transcription. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2009, 16, 916–922. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, C.P.; Rath, G.; Mathur, S.; Bhatnagar, D.; Ralhan, R. Potent Growth Suppressive Activity of Curcumin in Human Breast Cancer Cells: Modulation of Wnt/Beta-Catenin Signaling. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 181, 263–271. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuan, C. Curcumin Inhibits Growth of Human Breast Cancer Cells through Demethylation of DLC1 Promoter. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 425, 47–58. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Huang, O.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Z.; Shen, A.; Liu, H.; Geng, M.; Shen, K. Curcumin Induces Cell Death and Restores Tamoxifen Sensitivity in the Antiestrogen-Resistant Breast Cancer Cell Lines MCF-7/LCC2 and MCF-7/LCC9. Mol. Basel Switz. 2013, 18, 701–720. [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.M.; Eubank, T.D.; Roberts, R.D.; Wang, Y.; Pore, N.; Maity, A.; Marsh, C.B. M-CSF Signals through the MAPK/ERK Pathway via Sp1 to Induce VEGF Production and Induces Angiogenesis in Vivo. PloS One 2008, 3, e3405. [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Zhao, T.; Xu, C.; Shi, W.; Geng, B.; Shen, J.; Zhang, C.; Pan, J.; Yang, J.; Hu, S.; et al. Oncometabolite Succinate Promotes Angiogenesis by Upregulating VEGF Expression through GPR91-Mediated STAT3 and ERK Activation. Oncotarget 2017. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, B.; Beevers, C.S.; Odaka, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, W.; Shen, T.; et al. Curcumin Inhibits Protein Phosphatases 2A and 5, Leading to Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases and Death in Tumor Cells. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 868–875. [CrossRef]

- Banik, U.; Parasuraman, S.; Adhikary, A.K.; Othman, N.H. Curcumin: The Spicy Modulator of Breast Carcinogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2017, 36, 98. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K.; Resat, H. Constitutive Activation of STAT3 in Breast Cancer Cells: A Review. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 2570–2578. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, H.R.; Nedaeinia, R.; Sepehri Shamloo, A.; Nikdoust, S.; Kazemi Oskuee, R. Novel Delivery System for Natural Products: Nano-Curcumin Formulations. Avicenna J. Phytomedicine 2016, 6, 383–398.

- Young, N.A.; Bruss, M.S.; Gardner, M.; Willis, W.L.; Mo, X.; Valiente, G.R.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jarjour, W.N.; Wu, L.-C. Oral Administration of Nano-Emulsion Curcumin in Mice Suppresses Inflammatory-Induced NFκB Signaling and Macrophage Migration. PloS One 2014, 9, e111559. [CrossRef]

- Bachmeier, B.E.; Killian, P.H.; Melchart, D. The Role of Curcumin in Prevention and Management of Metastatic Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, R.; Takami, A.; Espinoza, J.L. Dietary Phytochemicals and Cancer Chemoprevention: A Review of the Clinical Evidence. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 52517–52529. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Yan, J.; Liang, H. The Clinical Applications of Curcumin: Current State and the Future. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2011–2031.

- Nelson, K.M.; Dahlin, J.L.; Bisson, J.; Graham, J.; Pauli, G.F.; Walters, M.A. The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1620–1637. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | number | VEGF low/high | VEGF high % | p-value |

| All patients | 230 | 122 / 108 | 47.0 % | |

| Histology | ||||

| Ductal | 175 | 85 / 90 | 51.4 % | 0.005 |

| Lobular | 43 | 32 / 11 | 25.6 % | |

| Other | 11 | 4 / 7 | 63.6 % | |

| Menopausal - | 45 | 25 / 20 | 44.4 % | 0.741 |

| Menopausal + | 185 | 97 / 88 | 47.6 % | |

| T < 2 | 117 | 58 / 64 | 54.7 % | 0.294 |

| T ≥ 2 | 113 | 59 / 49 | 43.4 % | |

| Ki67 < 23 | 97 | 50 / 47 | 48.5 % | 0.306 |

| Ki67 ≥ 23 | 52 | 22 / 30 | 57.7 % | |

| N0 | 147 | 80 / 67 | 45.6 % | 0.581 |

| N1 | 82 | 41 / 41 | 50.0 % | |

| G1 | 27 | 14 / 13 | 48.1 % | 0.534 $ |

| G2 | 132 | 74 / 58 | 43.9 % | |

| G3 | 71 | 34 / 37 | 52.1 % | |

| ER - | 46 | 21 / 25 | 54.3 % | 0.322 |

| ER + | 184 | 101 / 83 | 45.1 % | |

| Luminal A | 127 | 74 / 53 | 41.7 % | 0.201 |

| Luminal B | 57 | 27 / 30 | 52.6 % | |

| PR - | 101 | 50 / 51 | 50.5 % | 0.355 |

| PR + | 129 | 72 / 57 | 44.2 % | |

| HER2 - | 182 | 98/ 84 | 46.2 % | 0.745 |

| HER2 + | 48 | 24 / 24 | 50.0 % | |

| No TNBC | 198 | 109 / 89 | 44.9 % | 0.181 |

| TNBC | 32 | 13 / 19 | 59.4 % | |

| No Radiotherapy | 72 | 49 / 23 | 31.9 % | 0.003 |

| Radiotherapy | 158 | 73 / 85 | 53.8 % | |

| No Chemotherapy | 122 | 69 / 53 | 43.4 % | 0.290 |

| Chemotherapy | 108 | 53 / 55 | 50.9 % | |

| No endocrine therapy | 39 | 17 / 22 | 56.4 % | |

| Tamoxifen | 126 | 70 / 56 | 44.4 % | 0.424 |

| Aromatase Inhibitor | 64 | 34 / 30 | 46.9 % | |

| No Tamoxifen relapse |

80 | 43 / 37 | 46.3 % | 0.710 |

| Tamoxifen relapse |

46 | 27 / 19 | 41.3 % |

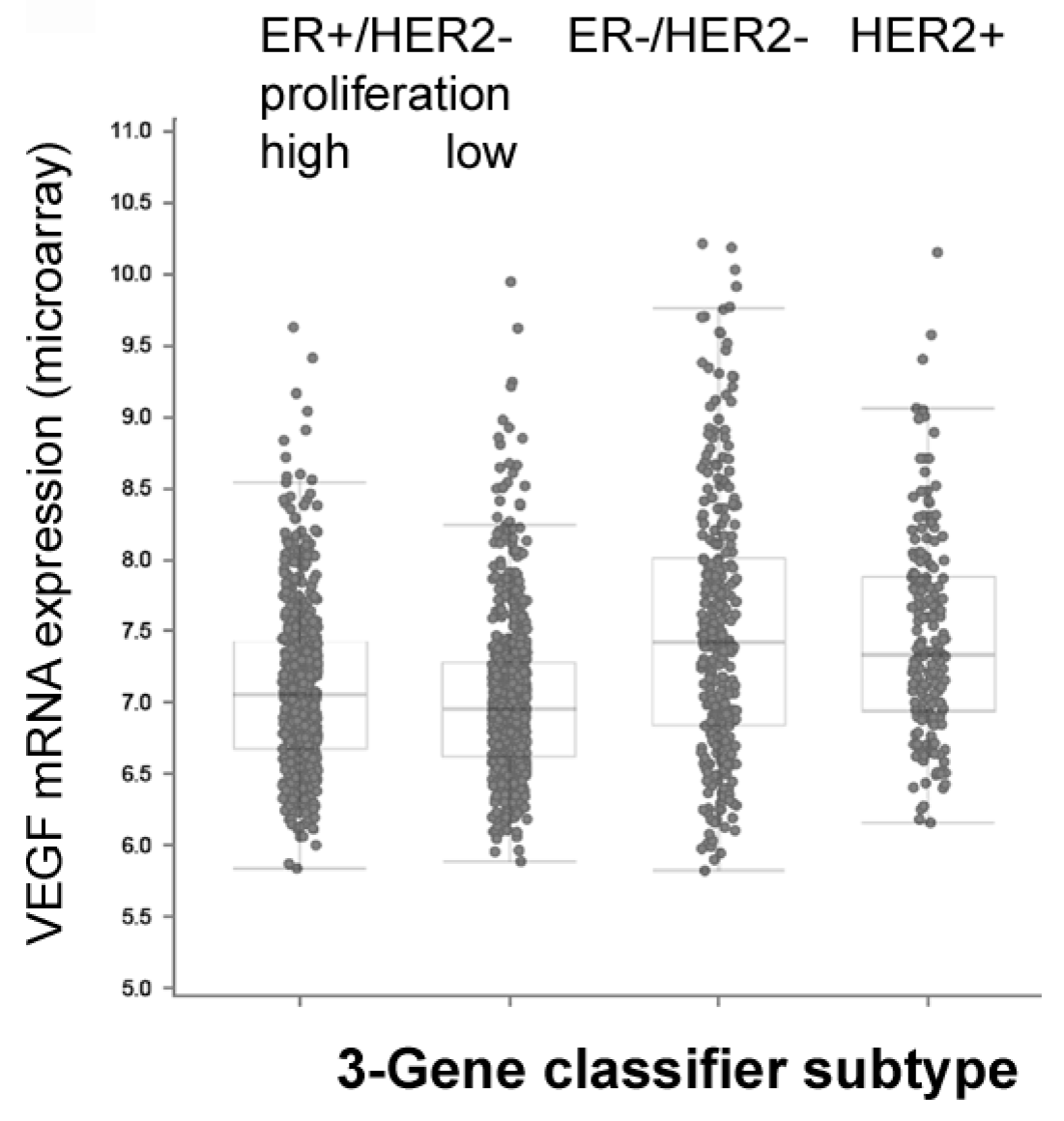

| BC subtype | Expression levels in METABRIC study (log-scale) Mean ± standard error */ ** One Way ANOVA p < 0.05 / 0.01 |

| VEGF-A | |

| ER -/+ | 7.58 ± 0.04 / 7.07 ± 0.02 ** |

| PR -/+ | 7.36 ± 0.03 / 7.04 ± 0.02 ** |

| HER2 -/+ | 7.16 ± 0.02 / 7.41 ± 0.04 ** |

| TNBC -/+ | 7.11± 0.02 / 7.60± 0.05 ** |

| IL1B | |

| ER -/+ | 6.68 ± 0.03 / 6.54 ± 0.02 ** |

| PR -/+ | 6.59 ± 0.02 / 6.56 ± 0.02 |

| HER2 -/+ | 6.60 ± 0.02 / 6.37 ± 0.04 ** |

| TNBC -/+ | 6.53 ± 0.02 / 6.81 ± 0.04 ** |

| HIF1A | |

| ER -/+ | 7.00 ± 0.03 / 6.57 ± 0.02 ** |

| PR -/+ | 6.79 ± 0.02 / 6.56 ± 0.02 ** |

| HER2 -/+ | 6.62 ± 0.02 / 6.98 ± 0.04 |

| TNBC -/+ | 6.61± 0.02 / 6.97 ± 0.03 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).