Introduction

Mood disorders represent a major global health burden, with depression and bipolar disorder constituting two of the most prevalent and disabling forms. Among them, anxiety-induced depression (AoD) remains understudied in terms of its longitudinal course and neurodevelopmental risks. Emerging evidence suggests that anxiety, particularly when chronic and untreated during adolescence, may serve not only as a comorbid symptom but as a prodromal phase of more severe affective disorders. This paper aims to explore the neurobiological trajectory that links chronic anxiety to depression and, in high-risk individuals, to eventual bipolar conversion. This paper further hypothesizes that AoD may not only heighten bipolar risk but also shape its eventual subtype, favoring Bipolar II or Rapid Cycling due to white matter vulnerabilities.

Theoretical Background

The comorbidity of anxiety and depression has long been recognized, yet most nosological frameworks, such as DSM-5 and ICD-11, conceptualize them as parallel or overlapping disorders rather than causally connected phases in a unified pathological trajectory. However, clinical observations frequently report that early-life anxiety, especially generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and social anxiety, often precedes the onset of major depressive disorder (MDD), suggesting a potential sequential relationship.

Neurodevelopmentally, adolescence represents a period of heightened vulnerability to affective dysregulation due to rapid structural remodeling in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. During this stage, persistent anxiety symptoms may promote maladaptive plasticity in emotion-related circuits, particularly via GABAergic overactivation, disrupted excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance, and stress-induced synaptic pruning. These early neural changes, if unresolved, may transition into the affective and cognitive patterns characteristic of MDD.

More concerningly, a subset of individuals with anxiety-originated depression (AoD) may develop features typical of bipolar disorder (BD) over time, including affective lability, impulsivity, and treatment resistance. This phenomenon raises the hypothesis that AoD constitutes a distinct neuroprogressive subtype of mood disorder, one that differs mechanistically from primary MDD and may require specific early-stage identification and intervention strategies.

Neurobiological Features of Anxiety-Originated Depression

Anxiety-originated depression (AoD) is increasingly recognized as a distinct affective phenotype with neurobiological features that diverge from both primary unipolar depression and traditional comorbid anxiety–depression syndromes. Neurodevelopmental studies suggest that AoD may be associated with early abnormalities in fronto-limbic circuitry, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus—regions central to cognitive control, stress regulation, and emotional processing.

Individuals with AoD often exhibit impaired inhibitory regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in excessive cortisol secretion and disrupted feedback signaling. Chronic cortisol exposure during adolescence—a period of ongoing structural brain maturation—has been shown to contribute to hippocampal volume reduction, altered synaptic remodeling, and decreased neurogenesis in stress-sensitive regions. Importantly, both the PFC and hippocampus are rich in glucocorticoid receptors, rendering them particularly vulnerable to stress-related degeneration.

White matter microstructure also appears compromised in AoD populations. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies have reported decreased fractional anisotropy in the anterior cingulum, corpus callosum, and prefrontal tracts among adolescents and young adults with anxiety-depression features. These abnormalities correlate with poor emotion regulation, heightened internalized distress, and reduced executive function—markers of affective network instability.

In addition, neuroinflammatory alterations, such as increased microglial activation and dysregulated cytokine expression, have been observed in both preclinical stress models and postmortem studies of depressed individuals. These processes may promote aberrant synaptic pruning and myelin degradation, further weakening fronto-limbic integrity. Collectively, these findings suggest that AoD is not simply “depression with anxiety traits” but a biologically unique condition characterized by early-onset inhibitory dysfunction, HPA dysregulation, and white matter vulnerability.

Theoretical Model: Phase-Specific Trajectory of AoD

To synthesize these neurobiological disruptions into a coherent framework, we propose a theoretical model outlining the phased progression of anxiety-originated depression (AoD). This model conceptualizes AoD as a continuum beginning with chronic stress and emotional dysregulation, proceeding through identifiable structural deterioration, and culminating in subtype-specific bipolar transition.

In the initial phase, sustained anxiety leads to HPA axis dysregulation, resulting in prolonged glucocorticoid elevation. This sets off hippocampal–prefrontal circuit stress, weakening inhibitory control and increasing synaptic instability. In the second phase, neuroanatomical changes become more pronounced: white matter microstructural compromise, reduced top-down regulation, and aberrant synaptic reorganization begin to appear.

If left untreated or improperly managed—particularly through inappropriate pharmacological exposure—AoD can enter a late phase characterized by emotional lability, functional disintegration, and increased risk for bipolar subtype development. This framework bridges structural, neurochemical, and behavioral dimensions of AoD, providing a scaffold for hypothesis-driven research and longitudinal monitoring.

Figure 1.

A tripartite mechanistic model illustrating the neuroprogressive trajectory from Anxiety-Originated Depression (AoD) to subtype-specific bipolar disorder. Corticosteroid-induced molecular damage impairs hippocampal and prefrontal circuits, leading to synaptic instability and white matter vulnerability. Clinically, these alterations manifest as AoD, which may subsequently progress into Bipolar II or Rapid Cycling subtypes due to structural and neurochemical decompensation under chronic stress.

Figure 1 was generated with the assistance of OpenAI’s image generation model based on author-defined conceptual frameworks. These images are intended to illustrate theoretical constructs and proposed methodology, and are not derived from empirical datasets. All schematic content has been validated for scientific accuracy by the authors prior to submission.

Figure 1.

A tripartite mechanistic model illustrating the neuroprogressive trajectory from Anxiety-Originated Depression (AoD) to subtype-specific bipolar disorder. Corticosteroid-induced molecular damage impairs hippocampal and prefrontal circuits, leading to synaptic instability and white matter vulnerability. Clinically, these alterations manifest as AoD, which may subsequently progress into Bipolar II or Rapid Cycling subtypes due to structural and neurochemical decompensation under chronic stress.

Figure 1 was generated with the assistance of OpenAI’s image generation model based on author-defined conceptual frameworks. These images are intended to illustrate theoretical constructs and proposed methodology, and are not derived from empirical datasets. All schematic content has been validated for scientific accuracy by the authors prior to submission.

Neurotoxic Progression and Bipolar Conversion

While some individuals with anxiety-originated depression (AoD) show partial remission with conventional antidepressants, others experience a progressive course marked by neurobiological deterioration and affective instability. Longitudinal clinical research indicates that early anxious-depressive presentations are significantly more likely to convert into bipolar spectrum disorders, particularly Bipolar II and Rapid Cycling subtypes, within 5 to 7 years of onset.

The underlying progression may involve a cumulative neurotoxic cascade driven by stress-mediated glucocorticoid dysregulation. Persistent cortisol elevation leads to hippocampal atrophy, diminished prefrontal compensatory control, and widespread disconnection in emotion-regulatory networks. Notably, high cortisol levels have been correlated with reduced dendritic complexity and synaptic density in stress-sensitive brain regions, as well as impaired myelination and glial support functions.

Adolescent brains are especially susceptible to such changes due to ongoing maturation of fronto-limbic systems. Epigenetic modifications, such as altered BDNF methylation and disrupted miRNA expression (e.g., miR-218), may further impair synaptic remodeling and emotional regulation during this critical window. These molecular disruptions amplify affective lability, behavioral impulsivity, and circadian dysregulation—hallmarks commonly observed in bipolar prodromes.

Functional neuroimaging studies further support this model. Patients with AoD who later develop bipolar disorder often display early reductions in resting-state connectivity between the dorsolateral PFC and limbic structures, along with aberrant activity in the anterior cingulate cortex. These disruptions suggest a neural “decompensation” pattern, in which compensatory circuits fail under sustained affective load, accelerating the transition toward bipolar expression.

Taken together, the transition from AoD to bipolar disorder may not be abrupt but rather a neuroprogressive trajectory shaped by chronic stress exposure, glucocorticoid neurotoxicity, and structural brain vulnerability. Recognizing this process early offers opportunities for targeted intervention before potentially enduring circuit impairment occurs.

Clinical Translation and Treatment Prioritization

Diagnostic Challenges and Subtype Stratification:

AoD often eludes accurate diagnosis due to its ambiguous presentation. Traditional frameworks rely on current mood symptoms, overlooking developmental trajectories and neurocognitive vulnerabilities. Early-life stress, poor inhibitory control, and white matter anomalies can serve as early indicators of risk. Longitudinal profiling tools, such as digital phenotyping and cognitive inhibition tasks, should be integrated into routine assessment to improve predictive accuracy. Misclassification as unipolar depression may delay appropriate intervention and increase the likelihood of subtype progression.

Pharmacological Vulnerabilities and Ethical Considerations:

Pharmacological intervention remains essential in managing acute depressive and anxious states. However, in AoD, particularly among adolescents, excessive or poorly timed pharmacotherapy may heighten neural fragility. Preclinical evidence suggests SSRIs and benzodiazepines can disrupt mitochondrial function and synaptic energy metabolism, indirectly weakening prefrontal–hippocampal integrity. Without proper phase-specific monitoring, such exposure may accelerate AoD-to-bipolar transition. Therefore, ethical intervention timing is crucial. Non-invasive, psychological-first interventions (CBT, ACT, family systems therapy) should be prioritized, especially in youth. Stratified treatment that matches neurodevelopmental phase and individual risk can prevent irreversible progression.

Integrated Intervention Outlook and Future Directions

The proposed model of anxiety-originated depression (AoD) highlights a progressive disruption of prefrontal–hippocampal connectivity and white matter integrity due to chronic stress, inhibitory imbalance, and potential pharmacological overload. This neuroprogressive cascade underscores the urgency of early-stage recognition and accurate subtype differentiation.

Despite compelling conceptual support, empirical validation of AoD’s conversion pathway to specific bipolar subtypes remains limited. Longitudinal neural datasets are sparse, and there is a marked absence of systematic, high-frequency tracking studies that integrate both behavioral and neuroimaging metrics throughout the transition from unipolar depressive states to bipolar subtypes.

Additionally, the pharmacological risks associated with early intervention—particularly SSRIs and benzodiazepines in adolescents—must be weighed against the cost of untreated progression. While these agents remain front-line treatments in clinical psychiatry, their potential for inducing mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and synaptic instability (as suggested by preclinical studies) raises concern. These effects may be particularly detrimental in AoD patients, whose prefrontal–hippocampal systems are already compromised by stress.

To prevent irreversible neurodegeneration, neuroprotective interventions should be explored. These include anti-inflammatory agents, glutamatergic modulators, and myelin repair strategies. Simultaneously, behaviorally grounded therapies—such as cognitive control training, mindfulness-based stress reduction, CBT, ACT, and Family Systems Therapy—should be prioritized, especially for youth or early-stage cases. These approaches are better aligned with developmental neuroethics and may reduce affective volatility without incurring pharmacological burden.

These ethical dilemmas underscore the need for age-sensitive, subtype-stratified interventions informed by real-time neural and behavioral data.

To bridge this gap, we propose a future research framework that integrates:

Longitudinal, multimodal imaging platforms (e.g., combined fMRI + DTI + EEG) with weekly or biweekly scans during early high-risk periods, to capture temporal fluctuations in neural connectivity;

Simultaneous behavioral tracking (e.g., ecological momentary assessment + cognitive control indices) to model affective instability in real time;

Joint modeling of brain-behavior trajectories, using deep learning or simulation-based prediction, to delineate subtype trajectories;

Stratification by stress exposure, early-life trauma, sleep disruption, and inhibitory phenotype as individual-level moderators;

Inclusion of biopsychosocial risk models, embedding psychological resilience and social buffering factors alongside neural markers.

Importantly, these designs must remain feasible: frequent scans may be ideal but ethically or logistically infeasible for certain populations. Realistic adaptations may involve monthly fMRI + DTI + EEG sessions during defined windows of vulnerability (e.g., adolescence, post-trauma periods), supplemented by home-based cognitive tasks or digital phenotyping to reduce clinical burden.

Ultimately, anxiety-originated depression presents not only a biological challenge but an ethical inflection point: where the brain’s fragility, the timing of our decisions, and the developmental context of the individual intersect. Future models must reconcile mechanistic precision with personalized, age-appropriate, and ethically sound intervention strategies—offering the potential not only to prevent subtype transitions but also to reshape psychiatric treatment more broadly.

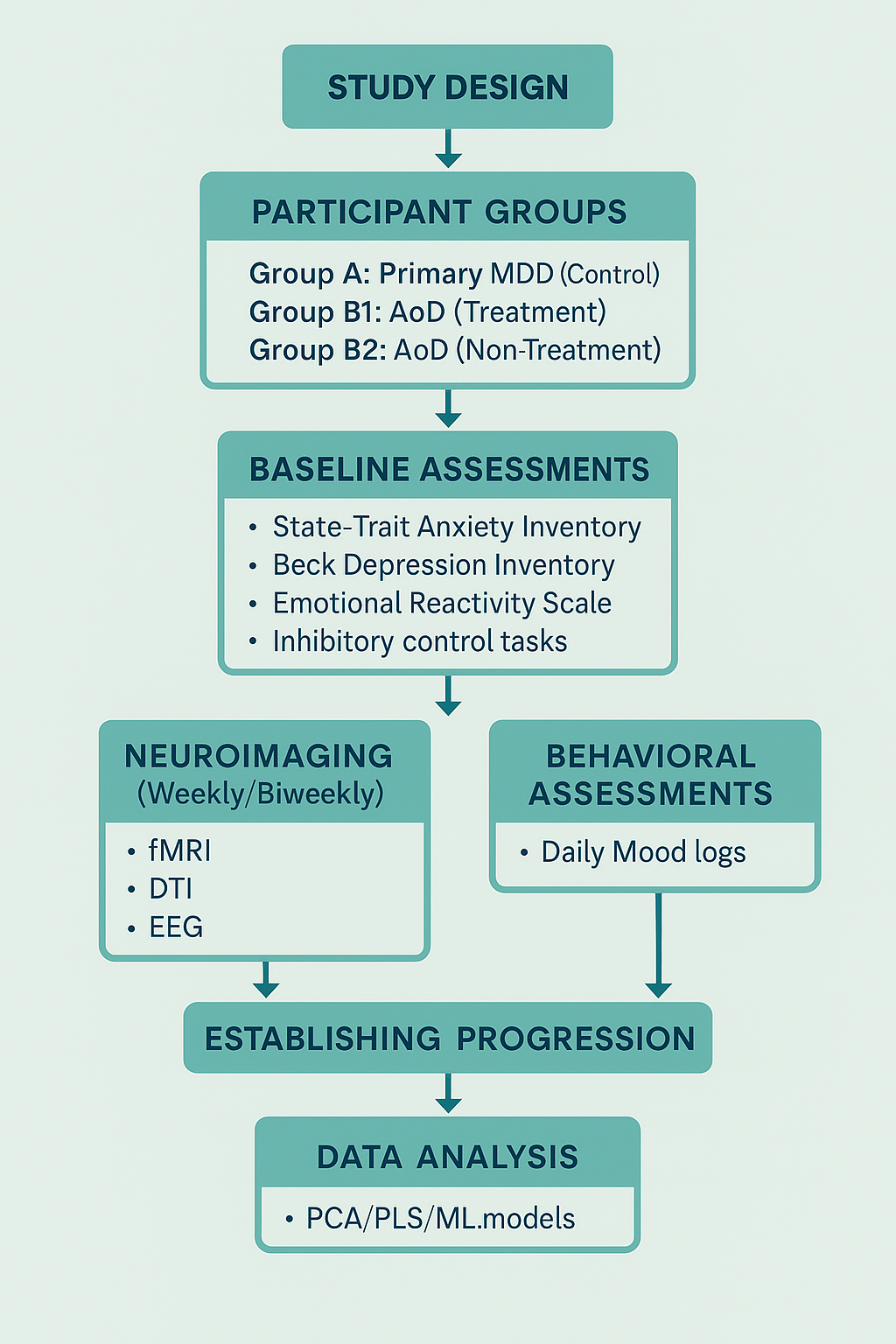

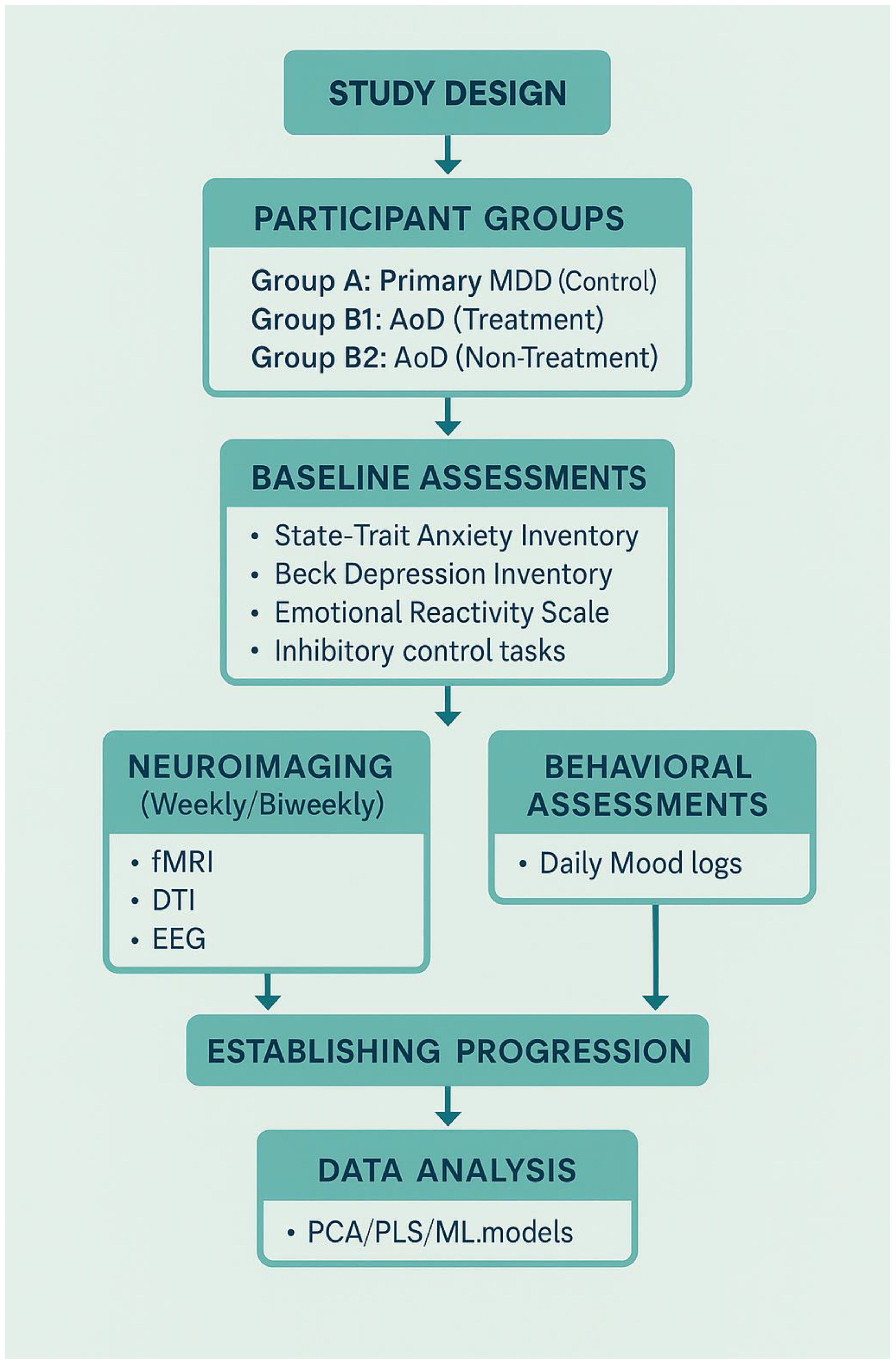

Proposed Experimental Design for Future Research

To validate the neuroprogressive trajectory of anxiety-originated depression (AoD) and clarify its critical intervention window, we propose a longitudinal research protocol that integrates neuroimaging, behavioral tracking, and advanced computational modeling.

Participant Groups and Screening Strategy

1.Participants will be recruited into three primary groups:

Group A: Primary MDD (Control Group)

Diagnosed with unipolar depression (no prior anxiety diagnosis)

No intervention during study (naturalistic observation)

2.Group B1: AoD – Treatment Group

Diagnosed with anxiety-originated depression (AoD)

Receives stratified intervention (psychological and/or pharmacological, depending on severity)

Group B2: AoD – Non-Treatment Group

Diagnosed with AoD but does not receive active intervention

Included to track natural progression and validate neuroprogressive risk

All groups will consist of first-episode participants (illness duration <6 months). Diagnostic validation will include structured clinical interviews and confirmed history of early-onset anxiety for AoD participants.

To ensure internal consistency and minimize confounds, all participants will undergo the following standardized behavioral assessments prior to baseline:

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II)

Emotional Reactivity Scale

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

Inhibitory control tasks

Daily mood logs for 2 weeks (pre-baseline phase)

Participants deviating significantly from expected clinical trajectories will be excluded post hoc.

To minimize hereditary confounds and better isolate neuroprogressive mechanisms, all participants will be required to have no first-degree family history of bipolar disorder. This exclusion criterion ensures that observed transitions toward bipolarity are not confounded by genetic predisposition, thereby strengthening causal inferences from neurodevelopmental and behavioral data.

Neural and Behavioral Tracking

Participants will undergo weekly or bi-weekly scans over a 6–8 month period using multimodal imaging:

fMRI to monitor emotion regulation circuitry and prefrontal–hippocampal connectivity

DTI to assess white matter microstructure and integrity

EEG to evaluate cortical excitatory/inhibitory balance

These scans will be synchronized with behavioral data collected at key timepoints:

Pre-baseline (2 weeks): Full psychometric battery for stratification

Baseline (T0): First scan and full battery repeated

Follow-up (T1–Tn): Short-form scales and mood logs aligned with each imaging session

Final (Tfinal): Final scan and full battery re-administered

Multimodal datasets will be aligned longitudinally to construct dynamic neurobehavioral progression profiles.

Hypotheses and Outcome Measures

We hypothesize that:

AoD participants will show faster degradation in white matter integrity and reduced prefrontal–limbic coherence compared to those with primary MDD.

Untreated AoD participants will exhibit the steepest trajectory of decline, supporting the neuroprogressive framework.

Behavioral instability (e.g., mood lability, impulse dysregulation) will correlate with circuit-level dysfunction and precede subtype-specific bipolar conversion.

Computational Modeling and Predictive Analysis

To manage and interpret high-dimensional, longitudinal data, the study will implement advanced analytic tools:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) will be used to reduce dimensionality and identify core neurobehavioral components explaining variance.

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression will model the relationships between imaging-derived neural changes (e.g., fMRI coherence, DTI FA) and behavioral symptom scores (e.g., STAI, BDI-II).

Supervised machine learning (ML) techniques—including logistic regression, random forest classifiers, and support vector machines (SVMs)—will be applied to predict individual risk for bipolar transition.

Temporal feature selection and cross-validation will ensure robust generalizability and minimize overfitting.

This modeling framework enables early identification of transition risks, aiding in personalized intervention planning and supporting scalable AI-assisted clinical tools for affective disorder stratification.

Broader Implications and Long-Term Utility

Beyond validating AoD trajectories, this research model may elucidate shared neuropathological processes across other psychiatric conditions (e.g., schizophrenia, PTSD, BPD). Longitudinal neural tracking combined with dynamic behavioral modeling may allow for AI-driven prediction pipelines, enabling real-time subtype differentiation, risk stratification, and mechanism-based treatment pathways.

Broader Implications

This experimental model may also illuminate how other psychiatric illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia, PTSD, borderline personality disorder) cause sustained brain injury. High-frequency neural tracking may allow researchers to generate predictive models and personalized risk algorithms, eventually feeding into AI-based clinical tools for real-time subtype stratification and intervention planning.

Conclusion

Anxiety-originated depression (AoD) should be conceptualized not merely as a depressive subtype with anxious features, but as a neuroprogressive trajectory with distinct neurodevelopmental and structural liabilities. Our integrative model illustrates how chronic stress, HPA axis dysregulation, and prefrontal–hippocampal disruption jointly contribute to emotional instability and heighten the risk of bipolar transition—particularly toward Bipolar II or Rapid Cycling subtypes.

Recognizing AoD as a prodromal state allows for earlier and more ethically appropriate intervention strategies. Psychological-first approaches, stratified care, and longitudinal tracking may prevent irreversible network damage and even alter the course or form of future bipolar onset.

As neuroimaging, digital phenotyping, and predictive modeling advance, tailored, age-sensitive strategies can be developed—marking a shift toward preventative psychiatry rooted in biological and developmental insight. Redefining AoD in this manner invites a fundamental shift in both research priorities and clinical care frameworks.

References

- Alloy, L.B.; Abramson, L.Y.; Walshaw, P.D.; Cogswell, A.; Hughes, M.E.; Iacoviello, B.M.; Hogan, M.E. Behavioral approach system (BAS)-relevant cognitive styles and bipolar spectrum disorders: Concurrent and prospective associations. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2015, 124, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Pallucchini, A.; Rizzato, S.; Madaro, D. Anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder comorbidity: A clinical and therapeutic challenge. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2017, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Bollettini, I.; Barberini, M.; Radaelli, D.; Poletti, S.; Locatelli, C.; Colombo, C. Lithium and GABAergic effects on brain activation during emotional tasks in bipolar depression. Psychological Medicine 2011, 41, 2119–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Yeh, P.H.; Bellani, M.; Radaelli, D.; Nicoletti, M.A.; Poletti, S.; Brambilla, P. Disruption of white matter integrity in bipolar depression as a possible structural marker of illness. Biological Psychiatry 2013, 74, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, N.; Sánchez-Moreno, J.; Torres, F.; Goikolea, J.M.; Valentí, M.; Vieta, E.; Martinez-Aran, A. Clinical predictors of rapid cycling in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 2008, 10, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korgaonkar, M.S.; Grieve, S.M.; Etkin, A.; Koslow, S.H.; Williams, L.M.; Gordon, E. Using multimodal neuroimaging to dissect the role of white matter abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry 2014, 19, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, K.; Burdick, K.E.; Wu, J.; Ardekani, B.A.; Szeszko, P.R. Relationship between white matter integrity and cognitive function in early bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 2009, 114, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depue, R.A.; Iacono, W.G. Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Review of Psychology 1989, 40, 457–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibar, D.P.; Westlye, L.T.; van Erp, T.G.M.; Rasmussen, J.; Leonardo, C.D.; Faskowitz, J.; Thompson, P.M. Subcortical volumetric abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Molecular Psychiatry 2018, 23, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, X. Disrupted white matter microstructural integrity in first-episode, drug-naive patients with anxiety disorders. NeuroImage: Clinical 2021, 30, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Su, S.; Liu, C. Longitudinal mapping of rapid cycling and bipolar subtypes using neuroimaging. Journal of Affective Disorders 2023, 326, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, P.; Pauling, M.; Stout, J.; Hozer, F.; Sarrazin, S.; Abé, C.; Houenou, J. Widespread white matter microstructural abnormalities in bipolar disorder: Evidence from mega- and meta-analyses across 3,033 individuals. Biological Psychiatry 2019, 86, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, M.; Malhi, G.S. The difficult lives of bipolar II disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 54, 803–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugi, G.; Hantouche, E.; Vannucchi, G.; Pinto, O.; Vieta, E. Anxiety symptoms as precursors of bipolar disorder: A longitudinal analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneck, C.D.; Miklowitz, D.J.; Calabrese, J.R.; Allen, M.H.; Thomas, M.R.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Sachs, G.S. Phenomenology of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2004, 184 (Suppl. 44), s30–s36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondo, L.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Hennen, J.; Floris, G. Rapid cycling bipolar disorder: Effects of long-term treatments. American Journal of Psychiatry 2003, 160, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, A.F.T. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2009, 10, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; et al. White matter microstructure in bipolar disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Bipolar Disorders 2011, 13, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, R.T.; et al. Oxidative stress in early stage bipolar disorder and the association with response to lithium. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2015, 62, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.L.; et al. Neural mechanisms of reward and threat processing in pediatric anxiety and depression. Biological Psychiatry 2020, 87, 1126–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liston, C.; et al. Stress-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional set-shifting. Journal of Neuroscience 2006, 26, 7870–7874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Glucocorticoids, depression, and mood disorders: structural remodeling in the brain. Metabolism 2005, 54(5 Suppl 1), 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morava, E.; Kozicz, T. Mitochondria and the economy of stress (mal)adaptation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2013, 37, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, W.D.; et al. White matter hyperintensity volume in late-life depression: relationship to clinical response and cognitive function. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2007, 15, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, S.; et al. Structural brain abnormalities in major depressive disorder: A selective review of recent MRI studies. Journal of Affective Disorders 2008, 110, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-06.2006.

- Sapolsky, R.M.; Krey, L.C.; McEwen, B.S. The neuroendocrinology of stress and aging: The glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis. Endocrine Reviews 1986, 7, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nature Reviews Immunology 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cikánková, T.; Fišar, Z.; Hroudová, J. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in bipolar disorder: Effect of the disease and pharmacotherapy. CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets 2019, 18, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Karyotaki, E.; Reijnders, M.; Purgato, M.; Barbui, C. Psychological interventions to prevent the onset of depressive disorders: A meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartzokis, G. Neuroglialpharmacology: Myelination as a shared mechanism of action of psychotropic treatments. Neuropharmacology 2011, 62, 2137–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, E.A.; Breen, G.; Forstner, A.J.; McQuillin, A.; Ripke, S.; Trubetskoy, V.; Sullivan, P.F. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nature Genetics 2019, 51, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insel, T.R. Digital phenotyping: A global tool for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchet, M.D.; et al. Support vector machine classification of major depressive disorder using diffusion-weighted neuroimaging and graph theory. Biological Psychiatry 2017, 81, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, K.L.; et al. Early childhood mental health screening: Recommendations for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20193443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, A.; et al. Developmental trajectory from early anxiety to full-blown bipolar disorder: Longitudinal evidence. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 215, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.L.; et al. Cross-disorder neuroimaging and the dimensional approach to mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; et al. Staging and personalized treatment in bipolar disorder: A position paper. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders 2023, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, C.M.; et al. Functional network dysfunction in anxiety and anxiety disorders across the lifespan: A review of functional connectivity data. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesdo, K.; et al. The natural course of anxiety disorders. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 19, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D.B.; et al. Large-scale brain network abnormalities predict cognitive impairments in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2018, 44, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouleris, N.; et al. Prediction models of functional outcomes for individuals in the clinical high-risk state for psychosis or with recent-onset depression: A multimodal, multicenter machine learning approach. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.C.; et al. Neural plasticity in response to cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: A multimodal imaging study. Molecular Psychiatry 2015, 20, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldapple, K.; et al. Modulation of cortical-limbic pathways in major depression: Treatment-specific effects of cognitive behavior therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry 2004, 61, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).