1. Introduction

Microglia typically originate from erythromyeloid progenitors found in the yolk sac during early embryogenesis and migrate to the central nervous system (CNS) occurs early in fetal development [

1]. Under normal conditions, in a state of homeostasis, the microglial population is long-lived and sustained through slow, localized proliferation without external input. However, in disease states, microglia can rapidly proliferate clonally [

2]. Furthermore, as the primary producers of proinflammatory cytokines, microglia are pivotal mediators of neuroinflammation and have the ability to induce or modulate a wide range of cellular responses [

3]. Following a pathological condition, the polarization of microglia to either a pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2) state can significantly influence the outcome [

4]. The excessive activation of M1 microglia during a pathological condition contributes to creating an overly inflammatory environment in the affected brain region, resulting in neuronal injury and neurodegeneration [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, regulating microglial activation is crucial for reducing inflammation during CNS medical conditions [

6,

7].

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) is integral to the development of the nervous system, ensuring proper neural formation and function. In the mature nervous system, the ECS regulates neuronal activity and network function [

9]. The ECS comprises endogenous cannabinoids, cannabinoid receptors, and the enzymes responsible for the synthesis and degradation of endocannabinoids. Endogenous cannabinoids (eCBs) are signaling lipids that activate cannabinoid specific receptors. Among the agonists, 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) and anandamide (AEA [N-arachidonoyl ethanolamine]) are the most well-characterized eCBs. Endocannabinoid signaling is often terminated by hydrolyzing the arachidonic group from either glycerol (2-AG) or ethanolamine (AEA). In the CNS, 2-AG is predominantly hydrolyzed by enzymes such as monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) or alpha/beta-hydrolase domain containing 6 (ABDH6) [

10]. Conversely, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) primarily degrades AEA, effectively terminating its activity [

11]. In terms of receptors, cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1R) and cannabinoid type 2 receptor (CB2R) are the cannabinoid receptors [

9]. Both receptors are G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that primarily couple with inhibitory G proteins. The expression of CB1R on oligodendrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursors, and microglia is significantly lower, and their physiological roles are still being elucidated. CB2R are mainly found in cells of immune origin, including microglia, though they may also be present in neurons, especially under pathological conditions. Activation of the CB2R in microglia typically leads to anti-inflammatory effects [

12]. It has been documented that CB2R activation in microglial cells results in the upregulation of M2 markers, effectively suppressing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and iNOS, while concurrently upregulating anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 [

12]. Furthermore, inhibiting eCB-degrading enzymes can enhance eCB signaling by elevating the levels of endogenous ligands, further contributing to reducing inflammation [

12]. This anti-inflammatory effect is achieved by downregulating proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, and upregulating anti-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-10 [

12]. Nonetheless, the impact of this inhibition on microglial polarization remains uncertain [

12].

Propofol (2,6-diisopropylphenol) is an intravenous anesthetic widely used in clinical practice, known to have anti-inflammatory properties in CNS pathological conditions via modulating the activation of microglia [

8,

13]. Propofol exerts protective and anti-inflammatory effects in CNS pathological conditions through a variety of mechanisms of action, such as maintaining mitochondrial function, reducing oxidative stress, decreasing excitotoxicity, preventing calcium overload, modulating programmed cell death, and promoting neurological recovery [

14]. In a study intended to describe the activity of propofol, they determined that propofol acts as a competitive inhibitor of the anandamide-degrading enzyme, FAAH, which correlates with the observed increase in brain anandamide levels [

15]. Additionally, they showed that propofol administration caused a variable increase in brain 2-AG content [

15]. This is consistent with data indicating that 2-AG is a substrate for FAAH in vitro, although other brain processes, such as the enzyme MAGL, also inactivate 2-AG [

15]. The unchanged metabolism of 2-AG in FAAH knockout mice suggests that propofol may inhibit MAGL or another metabolic pathway, leading to the observed increase in 2-AG levels [

15].

While propofol has been well-documented for protective and anti-inflammatory effects in various CNS pathological conditions, there remains a significant gap in research regarding its impact on microglial activity through the ECS. Specifically, no studies have yet explored how propofol might modulate the endocannabinoid signaling pathways to exert its anti-inflammatory effects in microglial cells. Our hypothesis was that propofol primarily modulates microglia by activating the CB2R. To validate this hypothesis, we treated LPS-stimulated SIM-A9 (microglial) cells with antagonists for both CB2R (AM630) and CB1R (AM281) to observe the changes in microglial viability and production of the cytokines TNF and IL-6 when the cells were treated with and without propofol.

3. Discussion

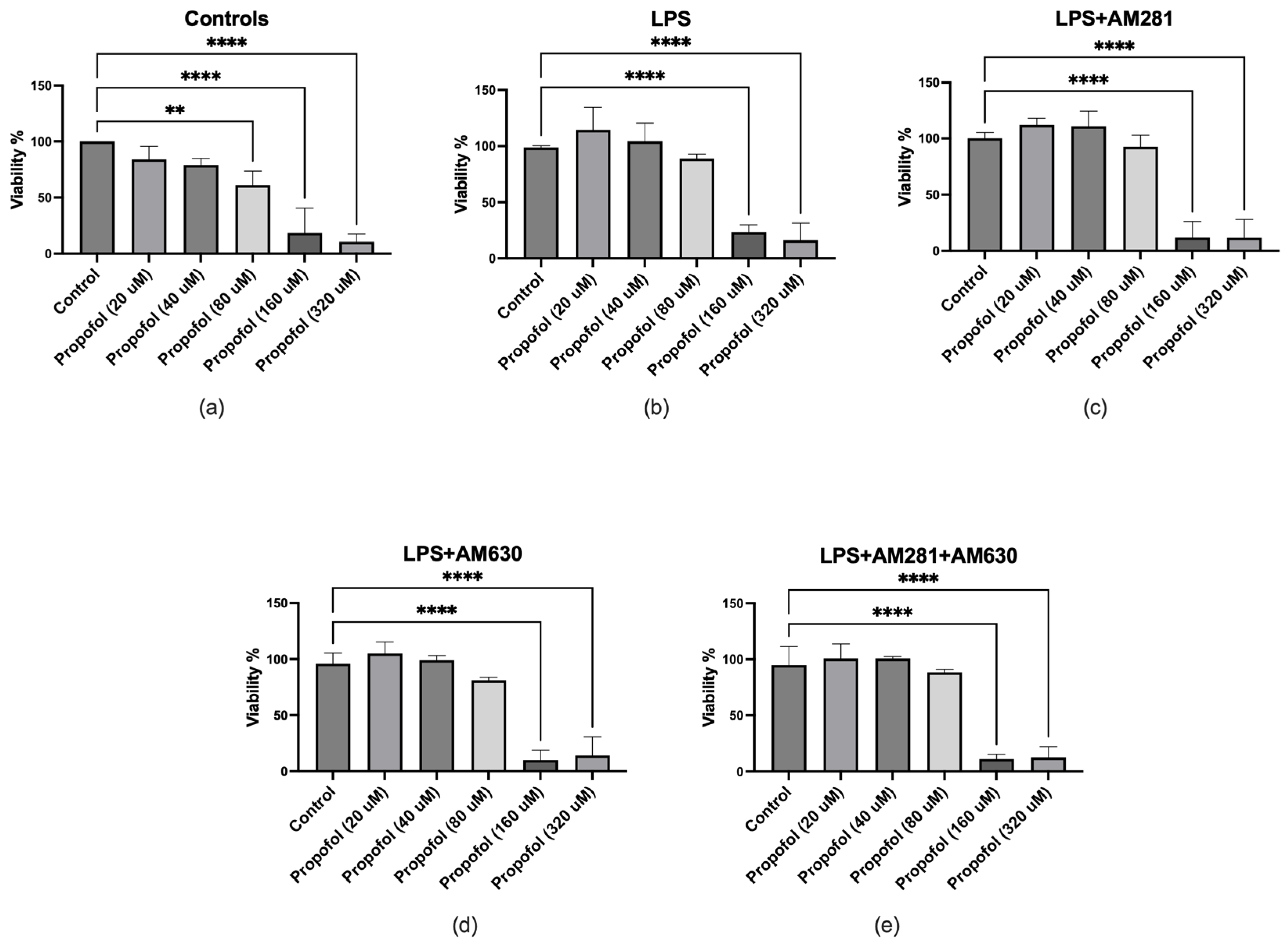

The results of cell viability demonstrate that propofol is safe in concentrations up to 80 μM. This is consistent with previous studieswhere propofol did not significantly impact BV-2 microglial cell viability at concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 μM. However, at 300 μM, cell viability decreased by approximately 81%, indicating cytotoxicity at this high dose [

16].

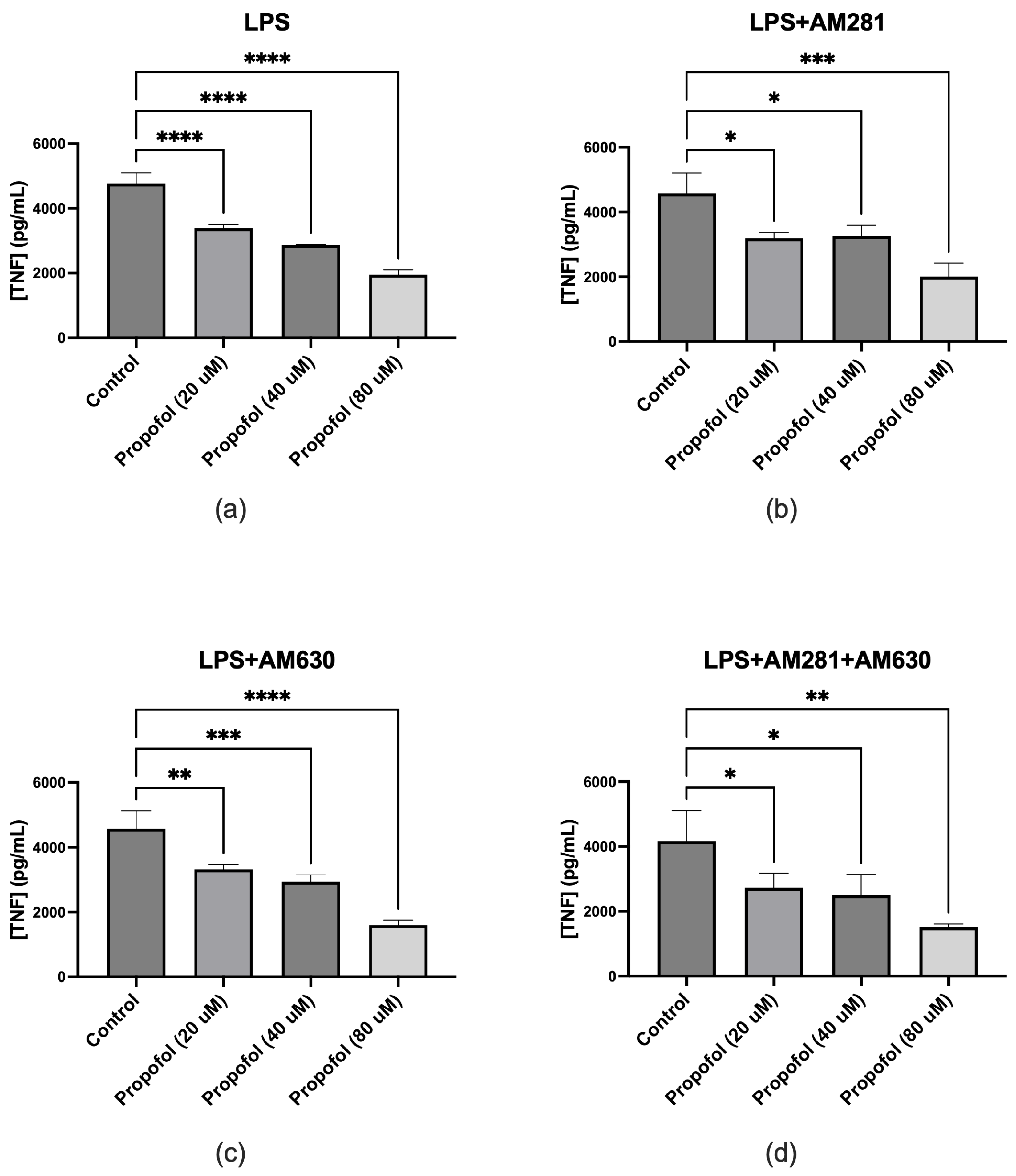

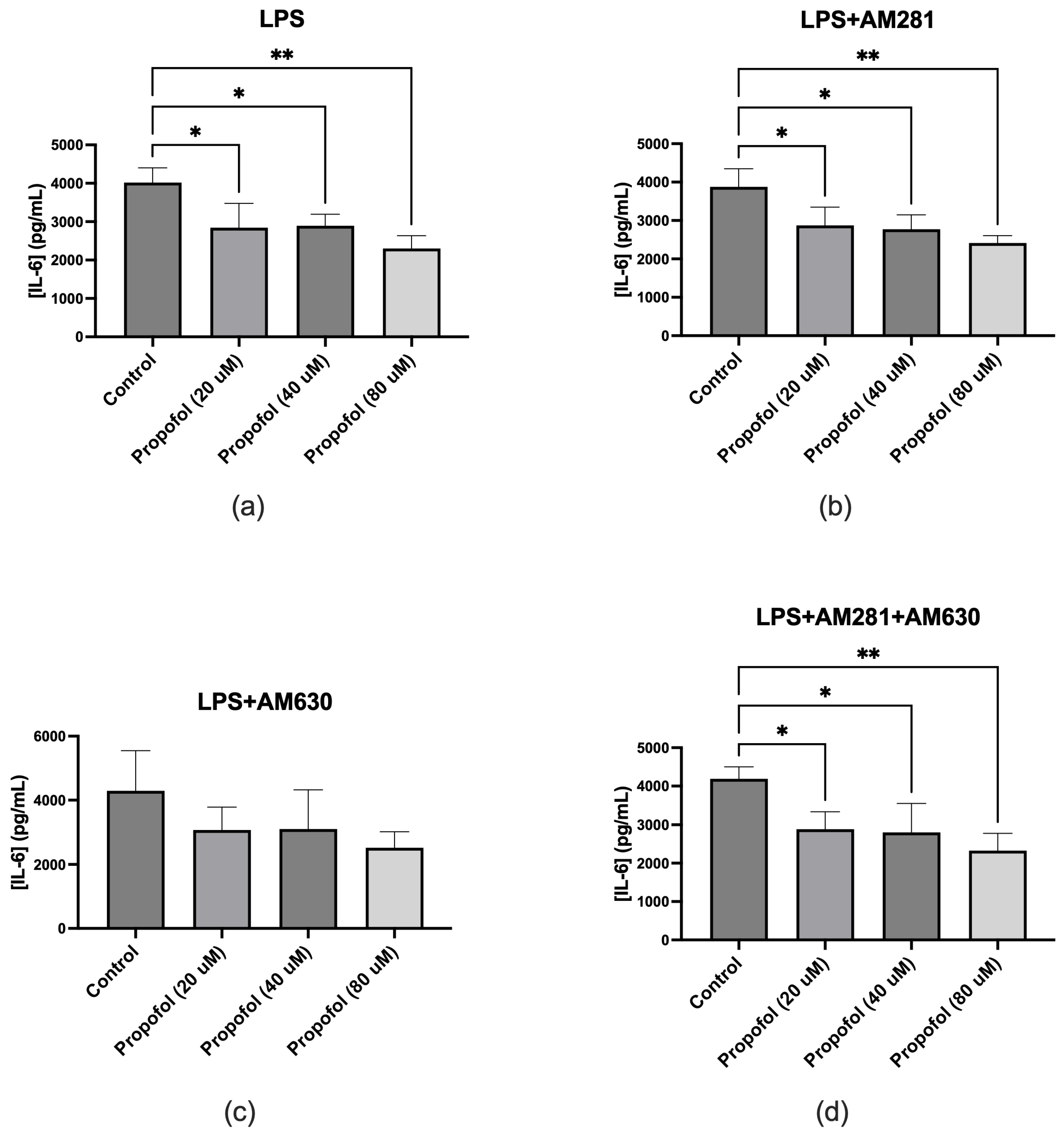

The TNF ELISA results revealed that propofol significantly reduces TNF production in SIM-A9 microglial cells under inflammatory conditions induced by LPS. This anti-inflammatory effect persisted even when CB1R or CB2R were blocked individually or together, indicating that propofol’s suppression of TNF is not mediated by ECS activation. This suggests that propofol may exert its modulatory effects through alternative signaling pathways independent of cannabinoid receptor activation. Furthermore, the IL-6 ELISA results demonstrated that propofol significantly attenuates IL-6 release. This anti-inflammatory effect remained evident even with CB1R blockade. A decrease in IL-6 release was also observed with CB2R blockade, although it was not statistically significant, suggesting that propofol’s ability to reduce IL-6 release may be partially mediated through CB2R. However, when both CB1R and CB2R were blocked simultaneously, propofol still significantly reduced IL-6 production, reinforcing that its anti-inflammatory action may involve alternative signaling pathways. These findings support the view that propofol modulates inflammatory cytokine release through complex, possibly multifaceted regulatory systems beyond cannabinoid receptor activation. The anti-inflammatory effects of propofol through modulation of other cytokine pathways have been confirmed by multiple studies. In a study, propofol demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory effects in both in vitro and in vivo models of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [

17]. Specifically, propofol treatment led to a marked reduction in the production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β and a simultaneous increase in the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. These changes were observed in hypoxia/reoxygenation-injured microglial cells and were associated with decreased microglial activation. The findings suggest that propofol modulates the inflammatory response by downregulating IL-1β and upregulating IL-10, thereby contributing to its neuroprotective effects. In another study, propofol was shown to reduce oxidative stress in CoCl₂-induced hypoxic BV2 microglial cells by significantly decreasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [

18]. CoCl₂ exposure led to elevated ROS levels and reduced antioxidant activity, including diminished superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC). Propofol treatment reversed these effects by restoring SOD and T-AOC levels, thereby inhibiting ROS overproduction and subsequent inflammatory responses. This antioxidative action was associated with suppression of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation and prevention of Hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) stabilization, ultimately reducing proinflammatory signaling. Additionally, propofol improved mitochondrial membrane potential, further supporting its protective role against oxidative damage in microglial cells. Furthermore, in one study, propofol significantly reduced nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-activated BV2 microglial cells, highlighting its anti-inflammatory potential [

19]. The study demonstrated that propofol significantly reduces nitric oxide (NO) production in LPS-activated BV2 microglial cells. LPS stimulation alone caused a 5-fold increase in NO levels compared to the control. However, treatment with propofol at concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 100 μM inhibited this response in a dose-dependent manner. At the highest concentration (100 μM), propofol reduced NO production by approximately 46% during LPS challenge. These effects were consistent at both the transcriptional (iNOS mRNA) and translational levels.

As the anti-inflammatory effects of propofol through modulation of the ECS had not yet been investigated, this study is the first to examine whether propofol’s anti-inflammatory effects may be mediated via the ECS. The ECS is essential for managing microglial activity during neuroinflammation [

20]. Under inflammatory conditions, microglia generally adopt a pro-inflammatory M1 state, releasing cytokines such as IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-6. Activating the ECS, especially via CB2R, mitigates this effect by encouraging a transition to the anti-inflammatory M2 state. This transition results in higher levels of anti-inflammatory markers like IL-10 and Arg-1. However, the findings of this study indicate that the anti-inflammatory effects of propofol, particularly its ability to suppress TNF and IL-6 production in microglial cells, are not solely dependent on CB1R or CB2R activation. While CB2R may play a partial role in mediating IL-6 reduction, the continued effectiveness of propofol in reducing both cytokines even when both cannabinoid receptors are blocked strongly suggests the involvement of alternative receptor-independent pathways in its anti-inflammatory mechanism.

This study has a few limitations that should be considered. First, the microglial cells used were obtained from female mice. Since research increasingly shows that immune responses, particularly within the central nervous system, can differ based on sex, it is possible that microglia from male mice might display varying activation patterns, cytokine release, or sensitivity to propofol and cannabinoid receptor antagonists. Future research should investigate whether these sex-related differences affect propofol's anti-inflammatory effects via the ECS. Second, only a single concentration (1 μM) of the cannabinoid receptor antagonists AM281 and AM630 was tested in this study. While this dosage was informed by previous studies, relying on one concentration restricts the ability to evaluate dose-dependent effects or explore whether higher or lower doses might produce different results. Future experiments using a broader range of antagonist concentrations could better elucidate receptor involvement and potential competitive binding. Finally, this study was conducted exclusively in vitro and has not yet been translated into human models. Although in vitro systems are valuable for exploring cellular mechanisms, they do not fully replicate the complex interactions of a living organism. Therefore, caution must be taken when generalizing these results to human physiology. Future studies involving human-derived microglia or clinical trials will be necessary to validate the relevance of these findings in the context of human neuroinflammation and anesthetic care. These limitations highlight important areas for future investigation that could improve the applicability and robustness of the findings.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Maintenance

SIM-A9 female mouse microglia cells (ATCC, Cat# CRL-3265, Manassas, VA, USA) were removed from -80°C storage. A T25 tissue culture flask was prepared with 10 mL of pre-warmed complete growth medium (e.g., DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin) and placed in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO₂ to equilibrate. The frozen cell vial was rapidly thawed in a 37°C water bath, then transferred into the T25 flask containing pre-warmed medium. Cells were incubated for 24 hours after which the medium was replaced with fresh complete medium. Once cells reached approximately 80–90% confluence, the supernatant was transferred to a 50 mL conical tube, and 0.25% trypsin-EDTA was added to the flask. The flask was returned to the 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator for 15 minutes to facilitate cell detachment. Any remaining attached cells were dislodged by gentle tapping and rinsing with fresh medium; the resulting cell suspension was combined with the previously collected supernatant and centrifuged at 1000 rpm, 4°C for 5 minutes. Cells were subsequently passaged in a 1:4 ratio until Passage 7 (P7).

4.2. Drug Preparations

Propofol (Thermo Scientific, Cat# L06841.14, Waltham, MA, USA) was prepared at final concentrations of 0, 20, 40, 80, 160, and 320 µM in serum-free medium (SFM). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# L2630, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used at 100 ng/mL, while the CB1R antagonist AM281 (Tocris Bioscience, Cat# 1115, Bristol, UK) and CB2R antagonist AM630 (Tocris Bioscience, Cat# 1120, Bristol, UK) were each used at 1 µM. All drug stocks were made in 100% DMSO; when diluted for final use, none of the treatment wells exceeded 0.5% DMSO. Control wells received only SFM, and vehicle-control wells received 0.5% DMSO (in SFM) without any active drug. Drug-treatment wells were prepared by mixing the appropriate volumes of each working solution in SFM just prior to application to cells, ensuring that the total DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.5%.

4.3. Plating, Treatment, and Sample Collection

Cells at Passage 7 were harvested for plating into 96-well plates. The supernatant was transferred to a 50 mL tube and the cell layer was incubated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA at 37°C, 5% CO₂ for 15 minutes. After cell detachment, the suspension was again collected in the 50 mL tube and centrifuged at 1000 rpm, 4°C for 5 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of complete medium. A 1:50 dilution was prepared by adding 10 µL of the resuspended cells to 490 µL of complete medium; 10 µL of this diluted suspension was mixed with 10 µL of trypan blue or ink solution, and 10 µL of the mixture was transferred to a counting chamber. Cells were seeded in three 96-well plates (n=3) at a density of ~10,000 cells/well. Cells were then plated (150 µL/well) and incubated for 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO₂ to allow attachment and recovery. After 48 hours, media from each well was aspirated and replaced with 150 µL of the respective treatment solutions. All treatments were performed in duplicate and the plates were incubated for another 24 hours. The plates were then centrifuged at 1000 rpm, 4°C for 5 minutes, and 100 µL of supernatant from each well was collected and stored at -80°C for subsequent TNF and IL-6 ELISA assays.

4.4. Viability Assay

Following supernatant collection, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent (APExBIO, Cat# CK04, Boston, MA, USA) was added to each well and the plates incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂. The absorbance of the formazan product in the centrifuged wells was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Finally, the viability test results were calculated using the following formula:

As: Absorbance of treated wells.

Ab: Absorbance of blank wells.

Ac: Absorbance of control wells (SFM).

4.5. TNF and IL-6 ELISAs

TNF and IL-6 levels were measured using commercial ELISA kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 88-7324 for TNF and Cat# 88-7064 for IL-6, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Each supernatant sample was thawed, added to the ELISA plate, and processed through the blocking, washing, and detection steps as specified. Absorbance readings of each well were used to determine cytokine concentrations by comparison to standard curves generated using known concentrations of TNF and IL-6.

4.6. Statistical Methods

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA; version 10.4.2). Data were first assessed for distribution using tests for normality and lognormality, with the Shapiro-Wilk test applied for assessing normality. For comparisons between groups, an ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.