Submitted:

21 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

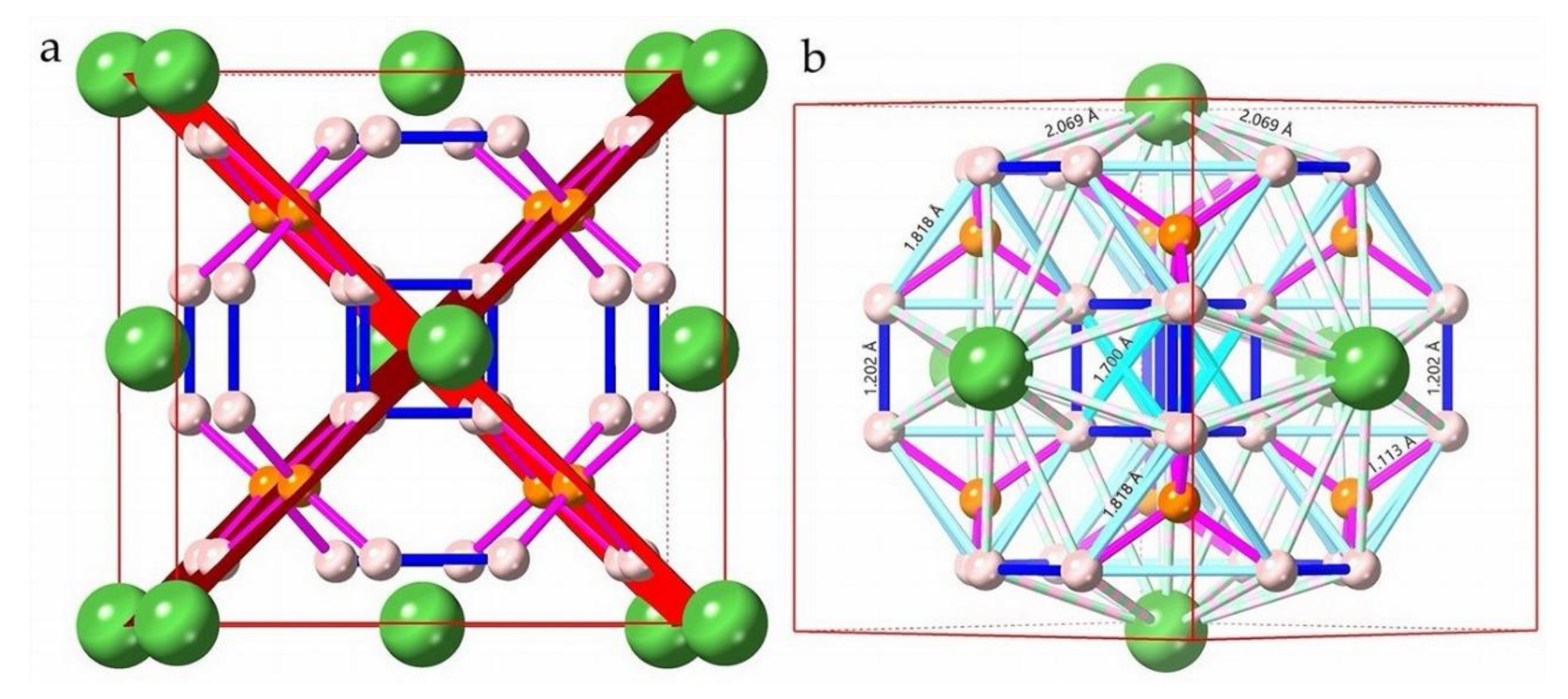

2.1. LaH10 Structure

2.2. Electronic Band Structures

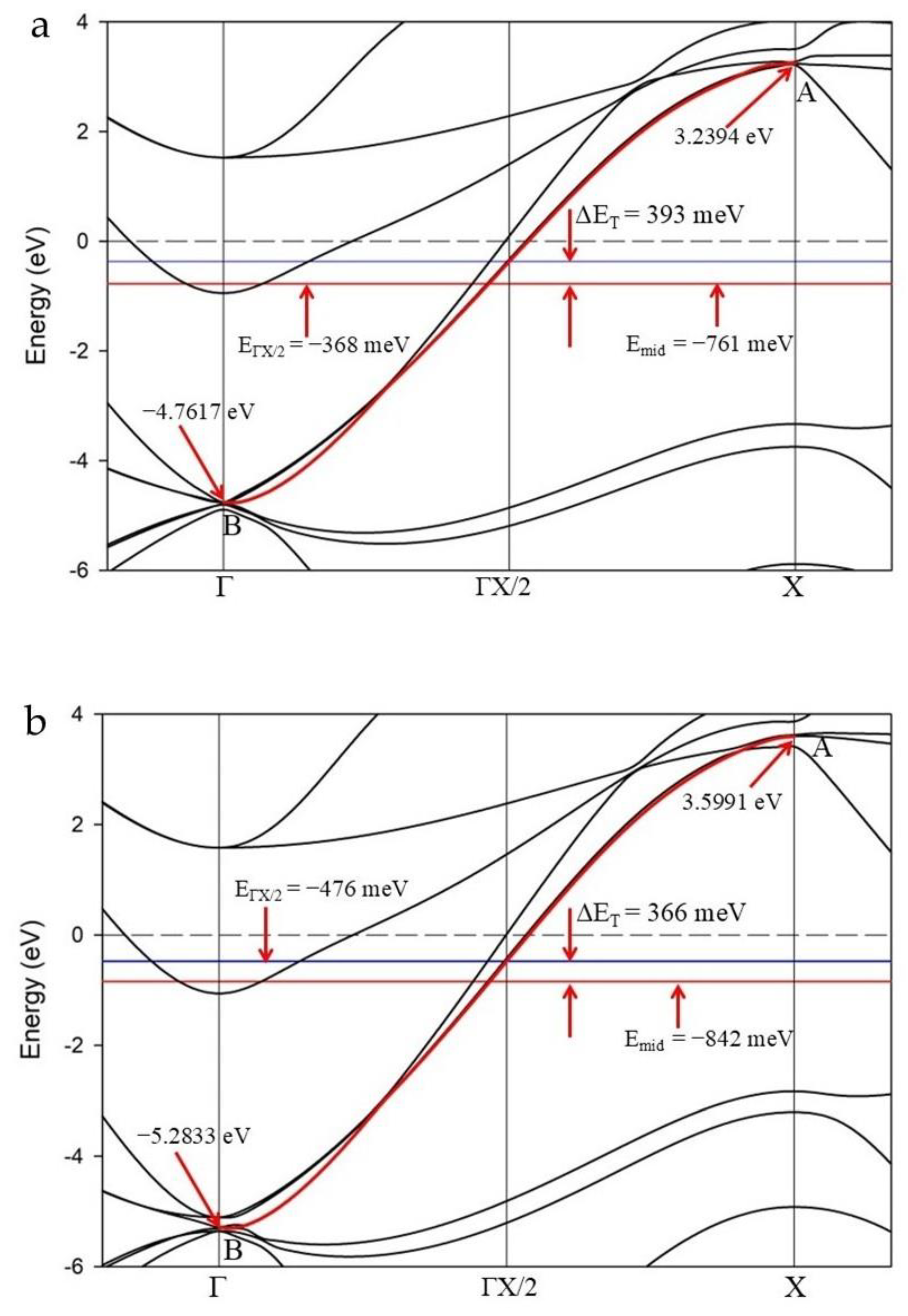

2.2.1. Cosine-Shaped Electronic Bands

2.2.1. Cosine Band Asymmetry

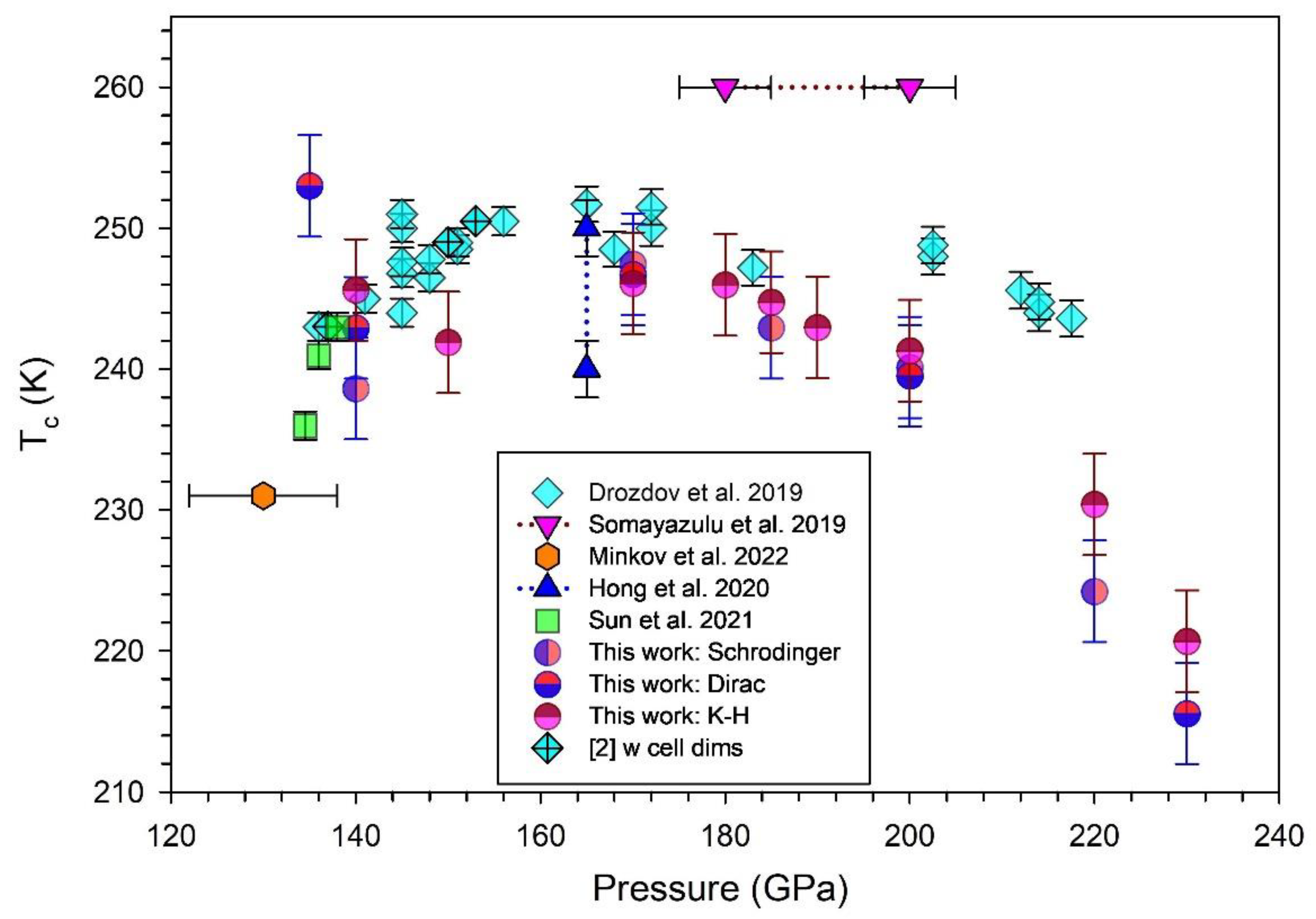

2.2.2. Estimates of Tc

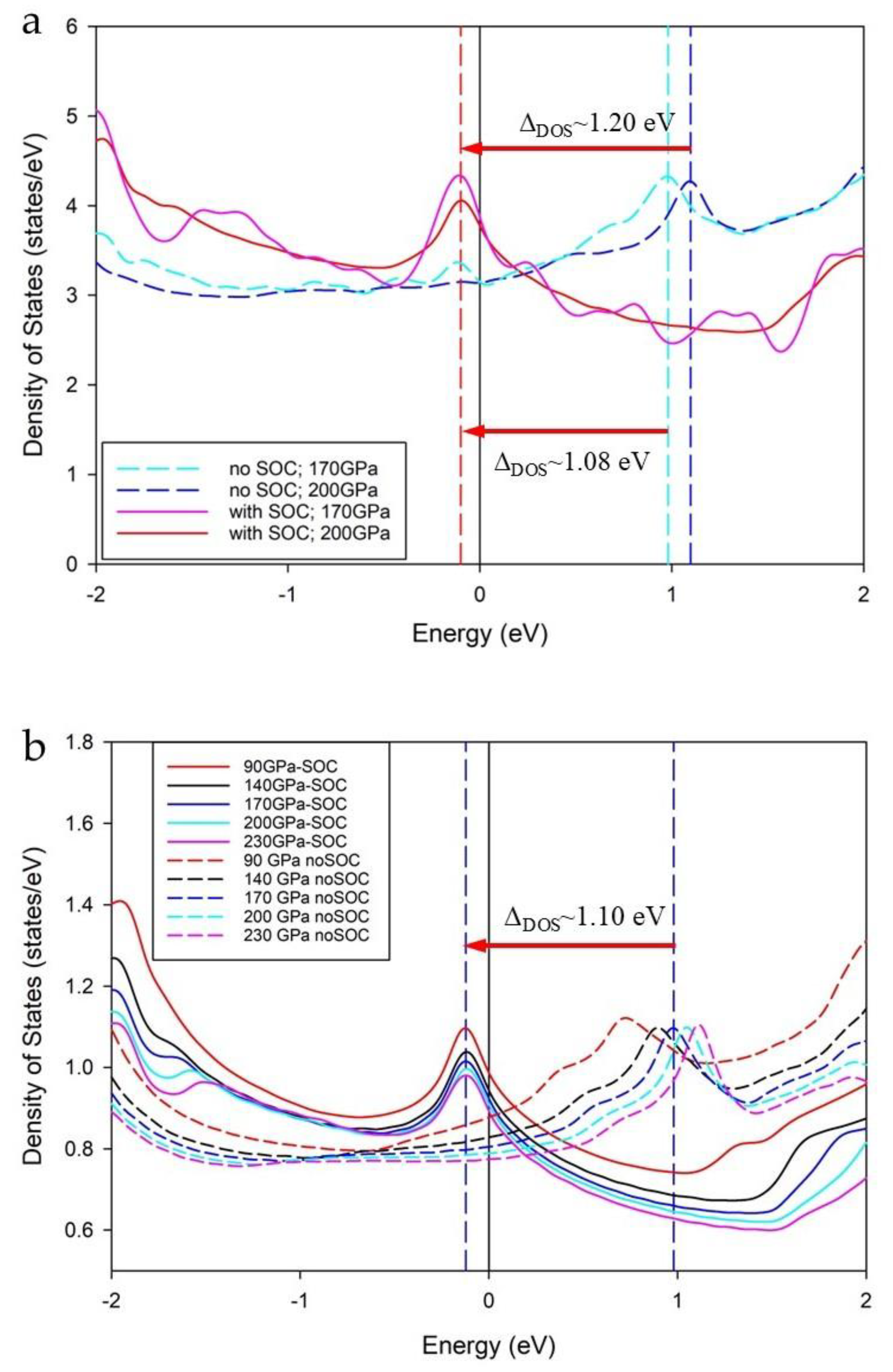

2.4. Density of States – van Hove singularities

3. Discussion

3.1. Atomic Orbitals and Bonding

3.2. Spin Orbit Coupling

- (i)

- the flat/steep band and;

- (ii)

- the van Hove,

3.3. Cosine Shaped Bands

3.4. Cosine Inflection in Real and Reciprocal Space

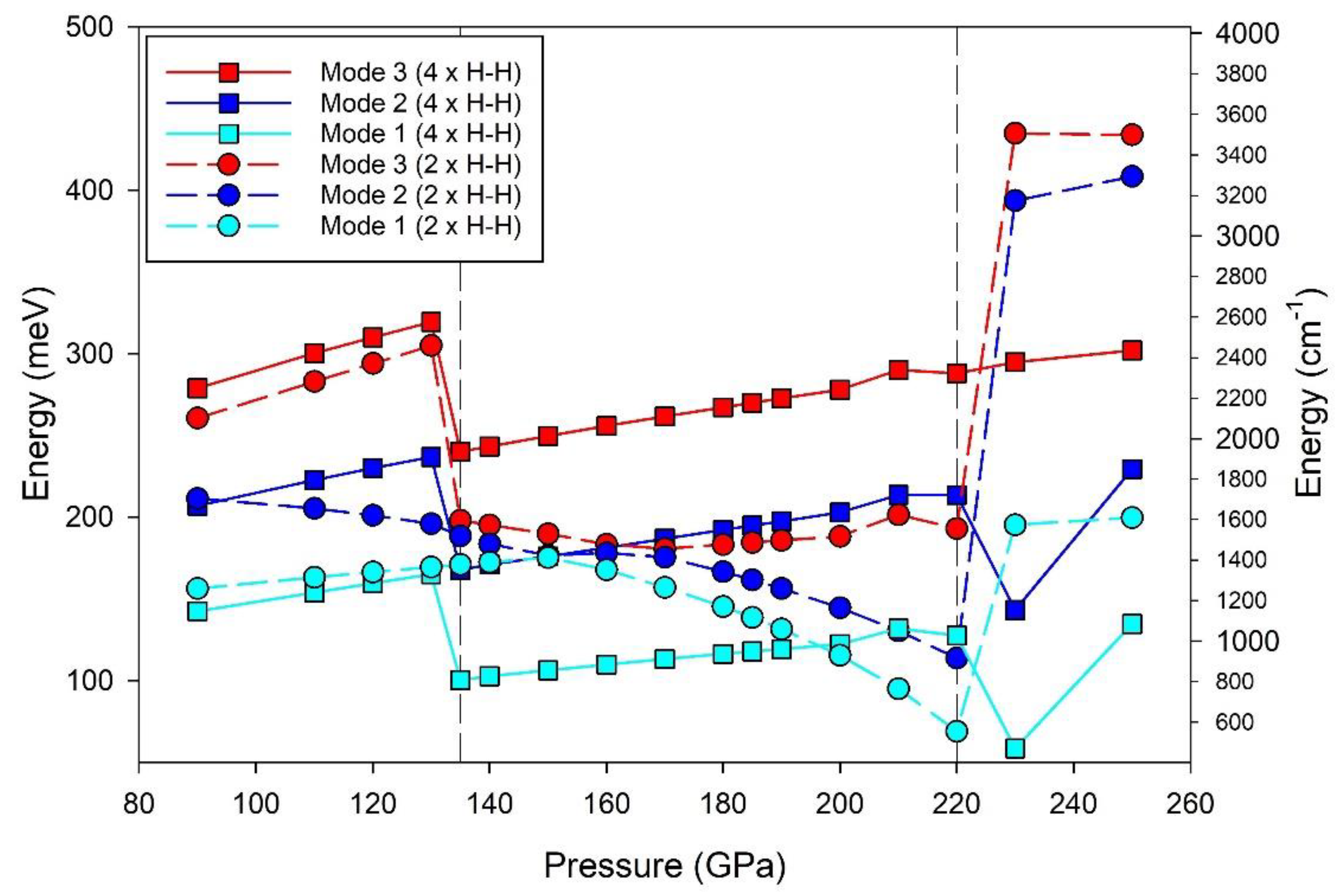

3.5. Lattice Vibrations

3.3. Tight Binding Potentials and Free Electrons

4. Methods

4.1. Calculation Parameters

Choice of DFT parameters

4.2. Superlattices and Symmetry

- (i)

- face centred cubic of space group and

- (ii)

- the reduced primitive lattice (space group P1) of the fcc cubic structure.

4.3. Previous Experiments and Calculations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Drozdov, A.P.; Eremets, M.I.; Troyan, I.A.; Ksenofontov, V.; Shylin, S.I. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature 2015, 525, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drozdov, A.P.; Kong, P.P.; Minkov, V.S.; Besedin, S.P.; Kuzovnikov, M.A.; Mozaffari, S.; Balicas, L.; Balakirev, F.F.; Graf, D.E.; Prakapenka, V.B.; et al. , Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures. Nature 2019, 569, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geballe, Z.M.; Liu, H.Y.; Mishra, A.K.; Ahart, M.; Somayazulu, M.; Meng, Y.; Baldini, M.; Hemley, R.J. Synthesis and Stability of Lanthanum Superhydrides. Angew Chem Int Ed 2018, 57, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Sun, Y.; Pickard, C.J.; Needs, R.J.; Wu, Q.; Ma, Y.M. Hydrogen Clathrate Structures in Rare Earth Hydrides at High Pressures: Possible Route to Room-Temperature Superconductivity. Phys Rev Lett 2017, 119, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somayazulu, M.; Ahart, M.; Mishra, A.K.; Geballe, Z.M.; Baldini, M.; Meng, Y.; Struzhkin, V.V.; Hemley, R.J. Evidence for Superconductivity above 260 K in Lanthanum Superhydride at Megabar Pressures. Phys Rev Lett 2019, 122, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, C.J.; Errea, I.; Eremets, M.I. Superconducting Hydrides Under Pressure, in: Marchetti, M.C. Mackenzie, A.P. (Eds.), Ann Rev Cond Matter Phys 2020, pp. 57-76.

- Minkov, V.S.; Bud’ko, S.L.; Balakirev, F.F.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Chariton, S.; Husband, R.J.; Liermann, H.P.; Eremets, M. Magnetic field screening in hydrogen-rich high-temperature superconductors. Nat Comm 2022, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Yang, L.; Shan, P.; Yang, P.; Liu, Z.; Sun, J.; Yin, Y.; Yu, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, Z. Superconductivity of Lanthanum Superhydride investigated using standard four-probe configuration under high pressures. Chin Phys Lett 2020, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Minkov, V.S.; Mozaffari, S.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.M.; Chariton, S.; Prakapenka, V.B.; Eremets, M.; Balicas, L.; Balakirev, F.F. High-temperature superconductivity on the verge of a structural instability in lanthanum superhydride. Nat Comm 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremets, M.I.; Minkov, V.S.; Drozdov, A.P.; Kong, P.P.; Ksenofontov, V.; Shylin, S.I.; Bud’ko, S.L.; Prozorov, R.; Balakirev, F.F.; Sun, D.; et al. , High-Temperature Superconductivity in Hydrides: Experimental Evidence and Details. J Supercond Novel Magnet 2022, 35, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremets, M.I.; Minkov, V.S.; Drozdov, A.P.; Kong, P.P. The characterization of superconductivity under high pressure. Nat Mater 2024, 23, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Y.; Ghosh, S.S.; Pickett, W.E. Compressed hydrides as metallic hydrogen superconductors. Phys Rev B 2019, 100, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaconstantopoulos, D.A.; Mehl, M.J.; Chang, P.H. High-temperature superconductivity in LaH10. Phys Rev B 2020, 101, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errea, I.; Belli, F.; Monacelli, L.; Sanna, A.; Koretsune, T.; Tadano, T.; Bianco, R.; Calandra, M.; Arita, R.; Mauri, F.; et al. , Quantum crystal structure in the 250-kelvin superconducting lanthanum hydride. Nature 2020, 578, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yi, S.; Cho, J.H. Multiband nature of room-temperature superconductivity in LaH10 at high pressure. Phys Rev B 2020, 101, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Wang, C.Z.; Yi, S.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, J.; Cho, J.H. Microscopic mechanism of room-temperature superconductivity in compressed LaH10. Phys Rev B 2019, 99, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Naumov, I.I.; Geballe, Z.M.; Somayazulu, M.; Tse, J.S.; Hemley, R.J. Dynamics and superconductivity in compressed lanthanum superhydride. Phys Rev B 2018, 98, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarco, J.A.; Mackinnon, I.D.R. Superlattices, Bonding-Antibonding, Fermi Surface Nesting, and Superconductivity. Cond Matter 2023, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.C.; Bianconi, A.; Mackinnon, I.D.R.; Alarco, J.A. Superlattice Symmetries Reveal Electronic Topological Transition in CaC6 with Pressure. Crystals 2024, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.C.; Bianconi, A.; Mackinnon, I.D.R.; Alarco, J.A. Superlattice Delineated Fermi Surface Nesting and Electron-Phonon Coupling in CaC6. Crystals 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarco, J.A.; Chou, A.; Talbot, P.C.; Mackinnon, I.D.R. Phonon Modes of MgB2: Super-lattice Structures and Spectral Response. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2014, 16, 24443–24456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarco, J.A.; Shahbazi, M.; Talbot, P.C.; Mackinnon, I.D.R. Spectroscopy of metal hexaborides: Phonon dispersion models. J Raman Spect 2018, 49, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarco, J.A.; Talbot, P.C.; Mackinnon, I.D.R. Phonon dispersion models for MgB2 with application of pressure. Physica C: Supercond Appl 2017, 536, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, A.; Batzner, S.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Aykol, M.; Cheon, G.; Cubuk, E.D. Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature 2023, 624, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebesell, J.; Surta, T.W.; Goodall, R.E.A.; Gaultois, M.W.; Lee, A.A. Discovery of high-performance dielectric materials with machine-learning-guided search. Cell Reports Phys Sci 2024, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Hyde, S.T.; Larsson, K.; Lidin, S. Minimal surfaces and structures - from inorganic and metal crystals to cell-membranes and bio-polymers. Chem Rev 1988, 88, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perenlei, G.; Talbot, P.C.; Martens, W.N.; Riches, J.; Alarco, J.A. Computational prediction and experimental confirmation of rhombohedral structures in Bi1.5CdM1.5O (M = Nb, Ta) pyrochlores. RSC Advances 2017, 7, 15632–15643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, T.; Alarco, J.; Cowie, B.C.C.; Mackinnon, I. Validating the Electronic Structure of Vanadium Phosphate Cathode Materials. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 45505–45520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, T.; Alarco, J.; Cowie, B.C.C.; Mackinnon, I. Regulation of surface oxygen activity in Li-rich layered cathodes using band alignment of vanadium phosphate surface coatings. J Mater Chem A 2022, 10, 24487–24509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarco, J.A.; Gupta, B.; Shahbazi, M.; Appadoo, D.; Mackinnon, I.D.R. THz/Far infrared synchrotron observations of superlattice frequencies in MgB2. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2021, 23, 23922–23932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshman, D.R.; Fiory, A.T. High-TC Superconductivity in Hydrogen Clathrates Mediated by Coulomb Interactions Between Hydrogen and Central-Atom Electrons. J Supercond Novel Magnet 2020, 33, 2945–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelluti, E.; Pietronero, L. Van Hove singularities and nonadiabatic effects in superconductivity. Europhys Lett 1996, 36, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.B.; Shi, Z.P.; Ozerov, M.; Du, Y.H.; Wang, Y.X.; Ni, X.S.; Meng, X.H.; Jiang, X.Y.; Wang, G.Y.; Hao, C.M.; et al. , The discovery of three-dimensional Van Hove singularity. Nat Comm 2024, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urch, D.S. Orbitals and Symmetry, Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, UK, 1970.

- Wang, C.; Yi, S.; Cho, J.-H. Pressure dependence of the superconducting transition temperature of compressed LaH10. Phys Rev B 2019, 100, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chachkarova, E.; Plekhanov, E.; Bonini, N.; Weber, C. Exploring the Effect of the Number of Hydrogen Atoms on the Properties of Lanthanide Hydrides by DMFT. Appl Sci 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Orbitron, The University of Sheffield https://winter.group.shef.ac.uk/orbitron/atomic_orbitals/4f/index.html (Accessed on 29/05/2025).

- Visual Polyhedra, https://dmccooey.com/polyhedra/index.html (Accessed on 15/05/2025).

- Fogden, A.; Hyde, S.T. Continuous transformations of cubic minimal surfaces. Eur Phys J B 1999, 7, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, S.T.; Ramsden, S.; Di Matteo, T.; Longdell, J.J. Ab-initio construction of some crystalline 3D Euclidean networks. Solid State Sci 2003, 5, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.J.; Zhang, Y.; Wagner, F.R. Chemical Bonding in Solids, Handbook of Solid State Chemistry, pp. 405-489.

- Lavroff, R.H.; Munarriz, J.; Dickerson, C.E.; Munoz, F.; Alexandrova, A.N. Chemical bonding dictates drastic critical temperature difference in two seemingly identical superconductors. Proc Nat Acad Sci 2024, 121 e2316101121.

- Amundsen, M.; Linder, J.; Robinson, J.W.A.; Zutic, I.; Banerjee, N. Colloquium: Spin-orbit effects in superconducting hybrid structures. Rev Modern Phys 2024, 96, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Simon, A.; Köhler, J. Superconductivity and Chemical Bonding in Mercury. Angew Chem Int Ed 1998, 37, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Simon, A.; Köhler, J. The origin of a flat band. J Solid State Chem 2003, 176, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelluti, E.; Pietronero, L. Nonadiabatic superconductivity: The role of van Hove singularities. Phys Rev B 1996, 53, 932–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.; Hirsch, J.E.; Marsiglio, F. Enhancement of superconducting Tc due to the spin-orbit interaction. Phys Rev B 2018, 97, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, J.; Bouvier, J. Superconductivity and the Van Hove Scenario. J Supercond Novel Magnet 2012, 25, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, R.S. The Van Hove Singularity and High-T Superconductivity: The Role of Nanoscale Disorder and Interlayer Coupling. J Phys Chem Solids 1991, 52, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Shukor, R. Acoustic Debye temperature and the role of phonons in cuprates and related superconductors. Supercond Sci Technol 2002, 15, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Z.; Wang, L.; Ishizuka, J.; Zhang, R.J.; Nogaki, K.; Cheng, Y.W.; Yang, F.Z.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhu, F.Y.; Liu, Z.T.; et al. , Coexistence of near- EF Flat Band and Van Hove Singularity in a Two-Phase Superconductor. Phys Rev X 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.S.; Ferrenti, A.M.; Cava, R.J. Testing whether flat bands in the calculated electronic density of states are good predictors of superconducting materials. J Phys Chem Solids 2021, 151, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, G.P. On the role of fermi energy in determining properties of superconductors: A detailed comparative study of two elemental superconductors (Sn and Pb), a non-cuprate (MgB2) and three cuprates (YBCO, Bi-2212 and Tl-2212). J Supercond Novel Magnet 2016, 29, 2755–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, I.D.R.; Almutairi, A.; Alarco, J.A. Insights from systematic DFT calculations on superconductors, in: Arcos, J.M.V. (Ed.), Real Perspectives of Fourier Transforms and Current Developments in Superconductivity, IntechOpen Ltd., London UK, 2021, pp. 1-29.

- Krarroubi, C.M.; Benayad, N.; Benosman, F.; Djermouni, M.; Kacimi, S.; Zaoui, A. Exploring superconducting signatures in high-pressure hydride compounds: An electronic-structure analysis. Physica C: Supercond Appl 2025, 628.

- Patterson, J.; Bailey, B. Solid-State Physics: Introduction to the Theory, Second ed., Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg Germany 2010.

- Ashcroft, N.W.; Mermin, N.D. Solid State Physics, Saunders, Philadelphia PA USA, 1976.

- Grüner, G. Density waves in solids, 1st ed., CRC Press, Boca Raton FL USA, 1994.

- Harrison, W.A. Applied Quantum Mechanics, World Scientific, Singapore, 2000.

- Canadell, E.; Doublet, M.-L.; Lung, C. Orbital Approach to the Electronic Structure of Solids, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2012.

- Hirsch, J.E. Superconductivity begins with H, World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore, 2020.

- Hirsch, J.E.; Marsiglio, F. Understanding electron-doped cuprate superconductors as hole superconductors. Physica C: Supercond Appl 2019, 564, 29-37.

- Hirsch, J.E. What holes in superconductors reveal about superconductivity. arXiv e-prints, 2025; 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.J.; Segall, M.D.; Pickard, C.J.; Hasnip, P.J.; Probert, M.I.J.; Refson, K.; Payne, M.C. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z Kristallogr 2005, 220, 567–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.; Palmer, S. CrystalMaker: Interactive Crystal and Molecular Modelling, CrystalMaker Software Limited, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom, 2024, pp. 484.

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys Rev Lett 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Chevary, J.A.; Vosko, S.H.; Jackson, K.A.; Pederson, M.R.; Singh, D.J.; Fiolhais, C. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: Applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys Rev B 1992, 46, 6671–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Abedi, A.; Maitra, N.T.; Yamashita, K.; Gross, E.K.U. Electronic Schrodinger equation with nonclassical nuclei. Phys Rev A 2014, 89, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, A.E.; Wills, J.M. Density functional theory for d- and f-electron materials and compounds. Int J Quantum Chem 2016, 116, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saue, T.; Bast, R.; Gomes, A.S.P.; Jensen, H.J.A.; Visscher, L.; Aucar, I.A.; Di Remigio, R.; Dyall, K.G.; Eliav, E.; Fasshauer, E.; et al. , The DIRAC code for relativistic molecular calculations. J Chem Phys 2020, 152, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartók, A.P.; Yates, J.R. Ultrasoft pseudopotentials with kinetic energy density support: Implementing the Tran-Blaha potential. Phys Rev B 2019, 99, 235103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pressure | Symm | Method* | k (Å−1) | SOC | a (Å) | Volume (Å3) | H8c–H32f (Å) | No. of Atoms | Enthalpy (eV x 102) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.005 | No | 5.14007 | 135.802 | 1.18288 | 44 | −6.3522 |

| 140 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.010 | Yes | 5.09088 | 131.940 | 1.14630 | 44 | −48.2289 |

| 170 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.005 | No | 5.06223 | 129.726 | 1.16964 | 44 | −6.1038 |

| 170 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.010 | Yes | 5.00160 | 125.120 | 1.12619 | 44 | −47.9884 |

| 200 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.005 | No | 4.99600 | 124.700 | 1.15865 | 44 | −5.8657 |

| 200 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.010 | Yes | 4.92460 | 119.430 | 1.14630 | 44 | −47.7596 |

| 220 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.005 | No | 4.95667 | 121.779 | 1.14767 | 44 | −5.7119 |

| 220 | Cubic | Schröd | 0.010 | Yes | 4.87850 | 116.107 | 1.09848 | 44 | −47.6126 |

| 140 | Prim | Schröd | 0.005 | Yes | 3.59986 | 32.987 | 1.13829 | 11 | −12.0572 |

| 170 | Prim | Schröd | 0.005 | No | 3.57967 | 32.435 | 1.16955 | 11 | −1.5260 |

| 170 | Prim | Schröd | 0.005 | Yes | 3.53669 | 31.281 | 1.11894 | 11 | −11.9971 |

| 220 | Prim | Schröd | 0.005 | Yes | 3.44964 | 29.027 | 1.09207 | 11 | −11.9031 |

| 90 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | No | 3.75407 | 37.410 | 1.21246 | 11 | −1.6990 |

| 90 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | Yes | 3.73471 | 36.835 | 1.17919 | 11 | −12.1657 |

| 140 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | No | 3.63462 | 33.952 | 1.18286 | 11 | −1.5881 |

| 140 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | Yes | 3.59988 | 32.988 | 1.13831 | 11 | −12.0572 |

| 170 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | No | 3.57960 | 32.433 | 1.16967 | 11 | −1.5260 |

| 170 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | Yes | 3.53667 | 31.280 | 1.11894 | 11 | −11.9971 |

| 200 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | No | 3.53272 | 31.176 | 1.15872 | 11 | −1.4664 |

| 200 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | Yes | 3.48221 | 29.857 | 1.10215 | 11 | −11.9399 |

| 220 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | Yes | 3.44963 | 29.027 | 1.09206 | 11 | −11.9031 |

| 230 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | No | 3.49193 | 30.108 | 1.14191 | 11 | −1.4091 |

| 230 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | Yes | 3.43429 | 28.642 | 1.08730 | 11 | −11.8851 |

| 250 | Prim | K-H | 0.005 | Yes | 3.40526 | 27.921 | 1.07826 | 11 | −11.8498 |

| P (GPa) | SOC | ΔEL (eV) | ELmax (eV) | Emid (eV) | EΓX/2 (eV) | ΔET (meV) | ΔEgap (meV) | Tc (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | No | na | na | 0.70728 | 0.5220 | 185.3 | 92.6 | 233.2 |

| 140 | No | na | na | 0.54649 | 0.3420 | 204.5 | 102.2 | 257.4 |

| 170 | No | na | na | 0.45515 | 0.2490 | 206.2 | 103.1 | 259.5 |

| 200 | No | na | na | 0.36578 | 0.1432 | 222.6 | 111.3 | 280.2 |

| 230 | No | na | na | 0.27890 | 0.0613 | 217.6 | 108.8 | 273.9 |

| 100 | Yes | 0.0977 | −0.0405 | −0.74490 | −0.3130 | 431.9 | 108.0 | 271.8 |

| 110 | Yes | 0.1004 | −0.0353 | −0.75782 | −0.3260 | 431.8 | 108.0 | 271.8 |

| 130 | Yes | 0.1053 | −0.0262 | −0.77889 | −0.3540 | 424.9 | 106.2 | 267.4 |

| 135** | Yes | 0.1065 | −0.0243 | −0.76507 | −0.3620 | 403.1 | 100.8 | 253.7 |

| 140 | Yes | 0.1076 | −0.0222 | −0.76113 | −0.3680 | 393.1 | 98.3 | 247.4 |

| 150 | Yes | 0.1098 | −0.0187 | −0.77359 | −0.3850 | 388.6 | 97.1 | 244.6 |

| 170 | Yes | 0.1139 | −0.0124 | −0.80301 | −0.4120 | 391.0 | 97.8 | 246.1 |

| 180 | Yes | 0.1159 | −0.0103 | −0.81384 | −0.4230 | 390.8 | 97.7 | 246.0 |

| 185 | Yes | 0.1169 | −0.0090 | −0.81889 | −0.4300 | 388.9 | 97.2 | 244.8 |

| 190 | Yes | 0.1178 | −0.0080 | −0.82403 | −0.4380 | 386.0 | 96.5 | 243.0 |

| 200 | Yes | 0.1196 | −0.0063 | −0.84157 | −0.4510 | 390.6 | 97.6 | 245.8 |

| 220 | Yes | 0.1231 | −0.0032 | −0.84209 | −0.4760 | 366.1 | 91.5 | 230.4 |

| 230 | Yes | 0.1248 | −0.0022 | −0.84265 | −0.4920 | 350.7 | 87.7 | 220.7 |

| 250 | Yes | 0.1279 | −0.0011 | −0.83064 | −0.5090 | 321.6 | 80.41 | 202.4 |

| Pressure (GPa) | No SOC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosine Band Amplitude | Interatomic Distance | ||||||||

| 4VSSσ (eV) | V (eV) |

d (Å) |

d/3 (Å) | H8c–H32f (Å) |

H32f–H32f (Å) |

||||

| 140 | 2.77338 | 0.6933 | 3.6831 | 1.2277 | 1.1828 | 1.2042 | |||

| 170 | 2.91491 | 0.7287 | 3.5926 | 1.1975 | 1.1696 | 1.1805 | |||

| 200 | 3.04240 | 0.7606 | 3.5165 | 1.1721 | 1.1587 | 1.1600 | |||

| With SOC | |||||||||

| Cosine Band Amplitude | Interatomic Distance | ||||||||

| 4VSSσ (eV) | V (eV) |

d (Å) |

d/2 (Å) | H8c–H32f (Å) |

H32f–H32f (Å) |

||||

| 140 | 8.00114 | 2.0003 | 2.1684 | 1.0842 | 1.1390 | 1.2303 | |||

| 170 | 8.35034 | 2.0876 | 2.1226 | 1.0613 | 1.1190 | 1.2088 | |||

| 200 | 8.70794 | 2.1770 | 2.0785 | 1.0393 | 1.1021 | 1.1896 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).