Submitted:

19 July 2025

Posted:

21 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

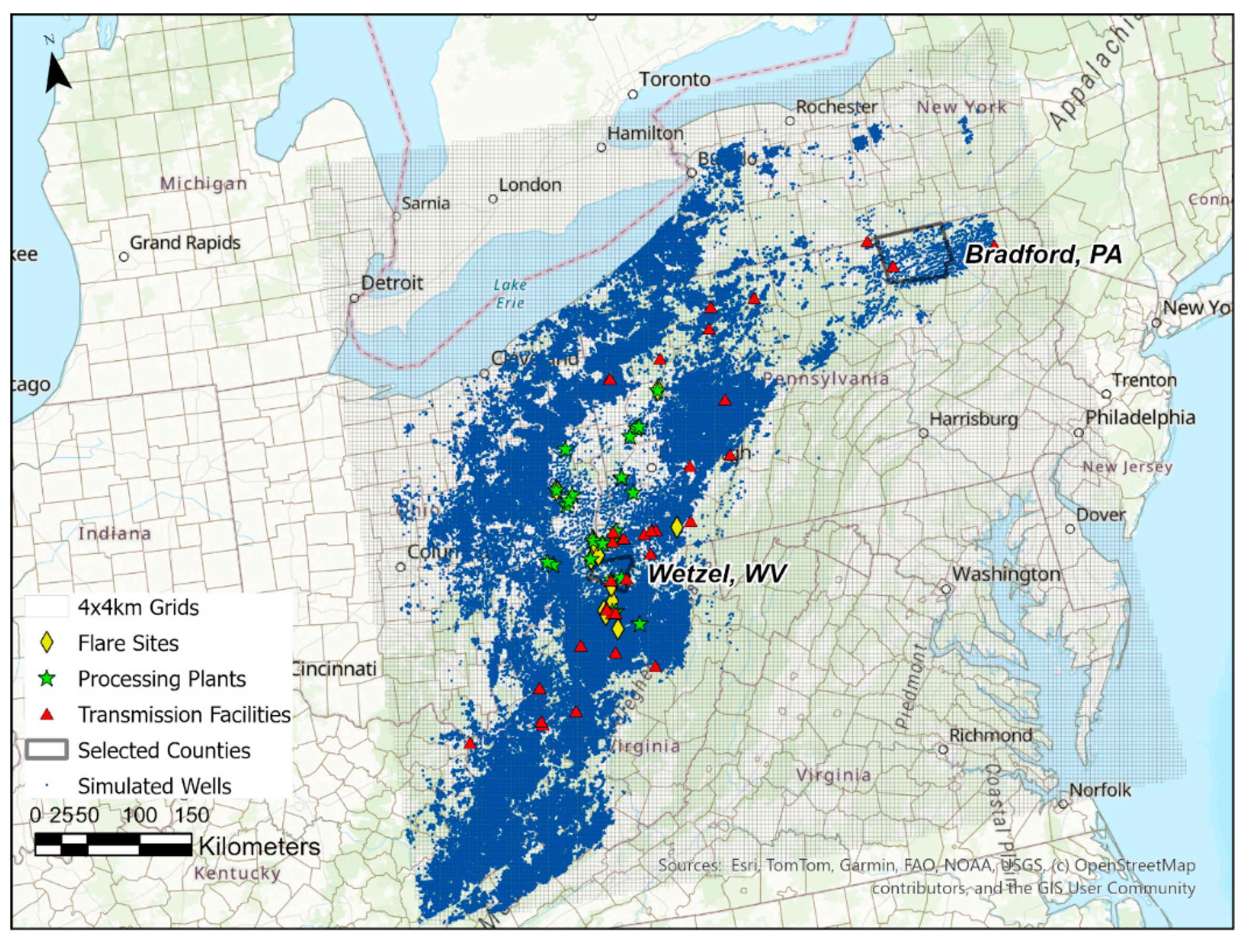

2.1. Study Domain

2.2. Spatial Aggregation

2.3. Emission Compositions

2.4. Emission sources

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. T. Allen, F. J. D. T. Allen, F. J. Cardoso-Saldaña, and Y. Kimura, “Variability in Spatially and Temporally Resolved Emissions and Hydrocarbon Source Fingerprints for Oil and Gas Sources in Shale Gas Production Regions,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 51, no. 20, pp. 12016–12026, Oct. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Petroleum Council, “Charting the Course,” Apr. 2024, Accessed: Jul. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://chartingthecourse.npc.org/documents/Charting_the_Course-V2-FINAL.pdf?a=1739340884.

- D. T. Allen, “Emissions from oil and gas operations in the United States and their air quality implications,” J Air Waste Manage Assoc, vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 549–575, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Modi, Y. M. Modi, Y. Kimura, L. Hildebrandt Ruiz, and D. T. Allen, “Fine Scale Spatial and Temporal Allocation of NOx Emissions from Unconventional Oil and Gas Development Can Result in Increased Predicted Regional Ozone Formation,” ACS ES&T Air, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 130–140, Feb. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. L. Vaughn et al., “Temporal variability largely explains top-down/bottom-up difference in methane emission estimates from a natural gas production region,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 115, no. 46, pp. 11712–11717, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Huang, S. L. Huang, S. Stokes, Q. Chen, and D. T. Allen, “Uncertainties in the Estimated Methane Emissions in Oil and Gas Production Regions Based on Aircraft Mass Balance Flights,” ACS Sustain Chem Eng, vol. 12, no. 29, pp. 11024–11032, Jul. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Schissel and D. T. Allen, “Impact of the High-Emission Event Duration and Sampling Frequency on the Uncertainty in Emission Estimates,” Environ Sci Technol Lett, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 1063–1067, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Enverus.” Accessed: Nov. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://prism.enverus.com/prism/home.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “EPA Facility Level GHG Emissions Data.” Accessed: Jul. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ghgdata.epa.gov/ghgp/main.

- Esri, “World Imagery.” Accessed: Jul. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://services.arcgisonline.com/ArcGIS/rest/services/World_Imagery/MapServer.

- Earth Observation Group, “Global Gas Flaring Observed from Space.” Accessed: Jul. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://eogdata.mines.edu/products/vnf/global_gas_flare.

- D. T. Allen et al., “A Methane Emission Estimation Tool (MEET) for predictions of emissions from upstream oil and gas well sites with fine scale temporal and spatial resolution: Model structure and applications,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 829, p. 154277, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Cardoso-Saldaña, K. F. J. Cardoso-Saldaña, K. Pierce, Q. Chen, Y. Kimura, and D. T. Allen, “A Searchable Database for Prediction of Emission Compositions from Upstream Oil and Gas Sources,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 3210–3218, Mar. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. T. Allen et al., “Measurements of methane emissions at natural gas production sites in the United States,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 110, no. 44, pp. 17768–17773, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Román Colón and L. F. Ruppert, “Central Appalachian basin natural gas database: distribution, composition, and origin of natural gases,” 2015. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “2020 Nonpoint Oil and Gas Emissions Estimation Tool V1.3.” Accessed: Jul. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://gaftp.epa.gov/Air/nei/2020/doc/supporting_data/nonpoint/oilgas/OIL_GAS_TOOL_v1.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks: 1990-2022.” Accessed: Jul. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa. 1990.

- D. Zimmerle et al., “Methane Emissions from Gathering Compressor Stations in the U.S.,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 54, no. 12, pp. 7552–7561, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- ENVIRON International Corporation and Inc. Eastern Research Group, “2011 Oil and Gas Emission Inventory Enhancement Project for CenSARA States,” Dec. 2012. Accessed: Jul. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.arb.ca.gov/ei/areasrc/oilandgaseifinalreport.pdf.

- Inc. Eastern Research Group, “SPECIFIED OIL & GAS WELL ACTIVITIES EMISSIONS INVENTORY UPDATE Prepared for: Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Air Quality Division,” Aug. 2014. Accessed: Jul. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://wayback.archive-it.org/414/20210527185258/https://www.tceq.texas.gov/assets/public/implementation/air/am/contracts/reports/ei/5821199776FY1426-20140801-erg-oil_gas_ei_update.pdf.

- D. T. Allen et al., “Methane Emissions from Process Equipment at Natural Gas Production Sites in the United States: Pneumatic Controllers,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 633–640, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Energy Information Administration, “Natural Gas Monthly Report.” Accessed: Jul. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/naturalgas/monthly/.

- D. T. Allen et al., “Methane Emissions from Process Equipment at Natural Gas Production Sites in the United States: Liquid Unloadings,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 641–648, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Vaughn, B. T. L. Vaughn, B. Luck, L. Williams, A. J. Marchese, and D. Zimmerle, “Methane Exhaust Measurements at Gathering Compressor Stations in the United States,” Environ Sci Technol, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 1190–1196, Jan. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “AP-42: Compilation of Air Emissions Factors from Stationary Sources.” Accessed: Jul. 09, 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/air-emissions-factors-and-quantification/ap-42-compilation-air-emissions-factors-stationary-sources.

| Location | Wells in simulation | Wells eliminated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Horizontal /directional | Vertical | Dry gas 1 | Wet gas 2 | Oil 3 | Wells completed in 2023 | No production or missing production data in 2023, or completed after 2024 | |

| Study domain | 201338 | 20902 | 174536 | 123170 | 42305 | 35863 | 1438 | 11449 |

| Bradford, PA | 1520 | 1507 | 13 | 1520 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 199 |

| Wetzel, WV | 1295 | 541 | 754 | 606 | 491 | 198 | 50 | 177 |

| Well production | Separator | Produced gas compositions | |||||

| Profile ID | Gas-to-oil ratio (SCF/BBL) | API gravity | Separator temperature (°F) | Separator pressure (psia) |

Methane (molar fraction) | Ethane (molar fraction) | Propane (molar fraction) |

| Dry | NA | NA | 63.1 | 278 | 97.4% | 2.11% | 0.0753% |

| Wet | 427083 | 65.7 | 72 | 97.5 | 76.8% | 14.9% | 4.95% |

| Oil | 5206 | 14.4 | 72 | 898 | 51.9% | 13.7% | 7.77% |

| Composition profile: dry | |||||

| Compositions | Methane | Ethane | Propane | Butanes 1 | VOCs |

| Wellstream (molar fraction) | 97.9% | 1.14% | 0.0174% | 0.0004% | 0.0178% (44.3 g/mol) |

| Produced gas (molar fraction) | 97.9% | 1.14% | 0.0174% | 0.0004% | 0.0178% (44.3 g/mol) |

| Water tank flash (kg/bbl) | 0.0824 | 2.75E-3 | 5.10E-5 | 5.23E-05 | 5.23E-5 |

| Condensate tank flash (kg/bbl) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Composition profile: wet | |||||

| Compositions | Methane | Ethane | Propane | Butanes 1 | VOCs |

| Wellstream (molar fraction) | 40.6% | 20.5% | 16.9% | 10.35% | 37.9% (68.5 g/mol) |

| Produced gas (molar fraction) | 63.4% | 23.2% | 9.55% | 2.21% | 12.1% (47.3 g/mol) |

| Water tank flash (kg/bbl) | 0.0626 | 0.0794 | 0.0438 | 0.0350 | 0.0893 |

| Condensate tank flash (kg/bbl) | 3.51 | 16.5 | 40.8 | 43.6 | 84.4 2 |

| Composition profile: oil | |||||

| Compositions | Methane | Ethane | Propane | Butanes 1 | VOCs |

| Wellstream (molar fraction) | 40.6% | 20.5% | 16.9% | 10.4% | 37.9% (68.5 g/mol) |

| Produced gas (molar fraction) | 50.4% | 24.2% | 16.7% | 6.43% | 24.3% (49.2 g/mol) |

| Water tank flash (kg/bbl) | 0.0149 | 0.0248 | 0.0229 | 0.0289 | 0.0648 |

| Condensate tank flash (kg/bbl) | 0.381 | 2.67 | 12.0 | 23.4 | 35.4 2 |

| Emission sites | Emission sources | Simulated pollutants | Main method for emission estimates | Hydrocarbon compositions | Pre-aggregation |

| Well sites: pre-production |

Drilling engines | Methane, VOCs, NOx | EPA Oil and Gas Tool [16] | EPA Oil and Gas Tool | Not aggregated |

| Hydraulic fracturing pumps | Methane, VOCs, NOx | EPA Oil and Gas Tool [16] | EPA Oil and Gas Tool | Not aggregated | |

| Completion flowbacks | Methane, Ethane, VOCs | MEET [12] | Wellstream | Not aggregated | |

| Well sites: production |

Artificial lift engines | Methane, ethane, VOCs, NOx | EPA Oil and Gas Tool [16] | County-throughput produced gas composition and EPA Oil and Gas Tool | Aggregated |

| Associated gas venting | Methane, ethane, VOCs | EPA Oil and Gas Tool [16] | Produced gas | Aggregated | |

| Condensate tank flash | Methane, ethane, VOCs | MEET [12] | Condensate tank flash | Aggregated | |

| Water tank flash | Methane, ethane, VOCs | MEET [12] | Water tank flash | Aggregated | |

| Leaks | Methane, ethane, VOCs | MEET [12] | Varying compositions | Aggregated | |

| Pneumatic controllers | Methane, ethane, VOCs | MEET [12] | Produced gas | Aggregated | |

| Chemical injection pumps | Methane, ethane, VOCs | MEET [12] | Produced gas | Aggregated | |

| Heaters | Methane, ethane, VOCs, NOx | EPA Oil and Gas Tool [16] | County-throughput produced gas composition and EPA Oil and Gas Tool | Aggregated | |

| Liquid unloadings | Methane, ethane, VOCs | MEET [12] | Produced gas | Not aggregated | |

| Gathering & boosting | Site-total emissions | Methane, ethane, VOCs, NOx | Zimmerle et al. [18] | Grid cell throughput produced gas | Not applicable |

| Gas processing sites | Site-total emissions | Methane, ethane, VOCs, NOx | GHGRP [9] | Grid cell throughput produced gas | Not applicable |

| Gas transmission sites | Site-total emissions | Methane, ethane, VOCs, NOx | GHGRP [9] | Grid cell throughput produced gas | Not applicable |

| Flare sites | Site-total emissions | Methane, ethane, VOCs, NOx | VIIRS [11] | Grid cell throughput produced gas | Not applicable |

| Simulated source | Equipment | Unit | Dry wells | Wet wells | Oil wells |

| Leaks | Meter / piping | Count per well | 0.93 | NA | |

| Chemical injection pumps | Chemical injection pumps | Count per well | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Pneumatic controllers | Pneumatic controllers | Count per well | 0.97 | 0.63 | 0.29 |

| High bleed | Fraction | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0% | |

| Low bleed | Fraction | 17.3% | 23.4% | 43.8% | |

| Intermittent bleed | Fraction | 82.5% | 76.6% | 56.7% | |

| Heaters | Heaters | Count per well | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Liquid unloading | Unloadings with plunger lifts | Fraction | 4.0% | NA | |

| Unloadings without plunger lifts | Fraction | 6.8% | NA | ||

| Well type | Methane, kg per meter drilled | VOCs, kg per meter drilled | NOx, kg per meter drilled |

| Horizontal | 0.83 | 0.036 | 0.0029 |

| Vertical | 0.26 | 0.014 | 0.0014 |

| Factor scenarios | Unit | Methane | VOCs | NOx |

| EPA defaults | Total emissions per event (kg) | 0.37 | 5.1 | 127 |

| Emission rate (kg/hr) | 0.0011 | 0.015 | 0.38 | |

| Alternative factors developed for Texas basins – used in the base case simulation | Total emissions per event (kg) | 15 | 203 | 5082 |

| Emission rate (kg/hr) | 0.045 | 0.61 | 15 |

| State | Methane, kg/hr/well | VOCs, kg/hr/well | NOx, kg/hr/well |

| KY | 4.53e-03 | 5.83e-04 | 4.47e-02 |

| NY | 1.59e-06 | 2.04e-07 | 1.57e-05 |

| OH | 5.86e-05 | 7.54e-06 | 5.78e-04 |

| PA | 4.53e-03 | 5.83e-04 | 4.47e-02 |

| VA | 4.53e -03 | 5.83e-04 | 4.47e-02 |

| WV | 4.53e -03 | 5.83e-04 | 4.47e-02 |

| State | Heating values, BTU/SCF | Methane, kg/hr/heater | VOC, kg/hr/heater | NOx, kg/hr/heater |

| PA | 1036 | 6.48e-04 | 1.55e-03 | 1.64e-02 |

| WV | 1082 | 6.20e-04 | 1.48e-03 | 1.57e-02 |

| KY | 1055 | 6.36e-04 | 1.52e-03 | 1.61e-02 |

| NY | 1032 | 6.50e-04 | 1.55e-03 | 1.65e-02 |

| OH | 1066 | 6.29e-04 | 1.51e-03 | 1.59e-02 |

| VA | 1050 | 6.39e-04 | 1.53e-03 | 1.62e-02 |

| Number of wells with liquid unloadings with plunger lifts | Number of wells with liquid unloadings without plunger lifts | |

| Basin | 6685 | 11214 |

| Bradford, PA | 10 | 17 |

| Wetzel, WV | 34 | 62 |

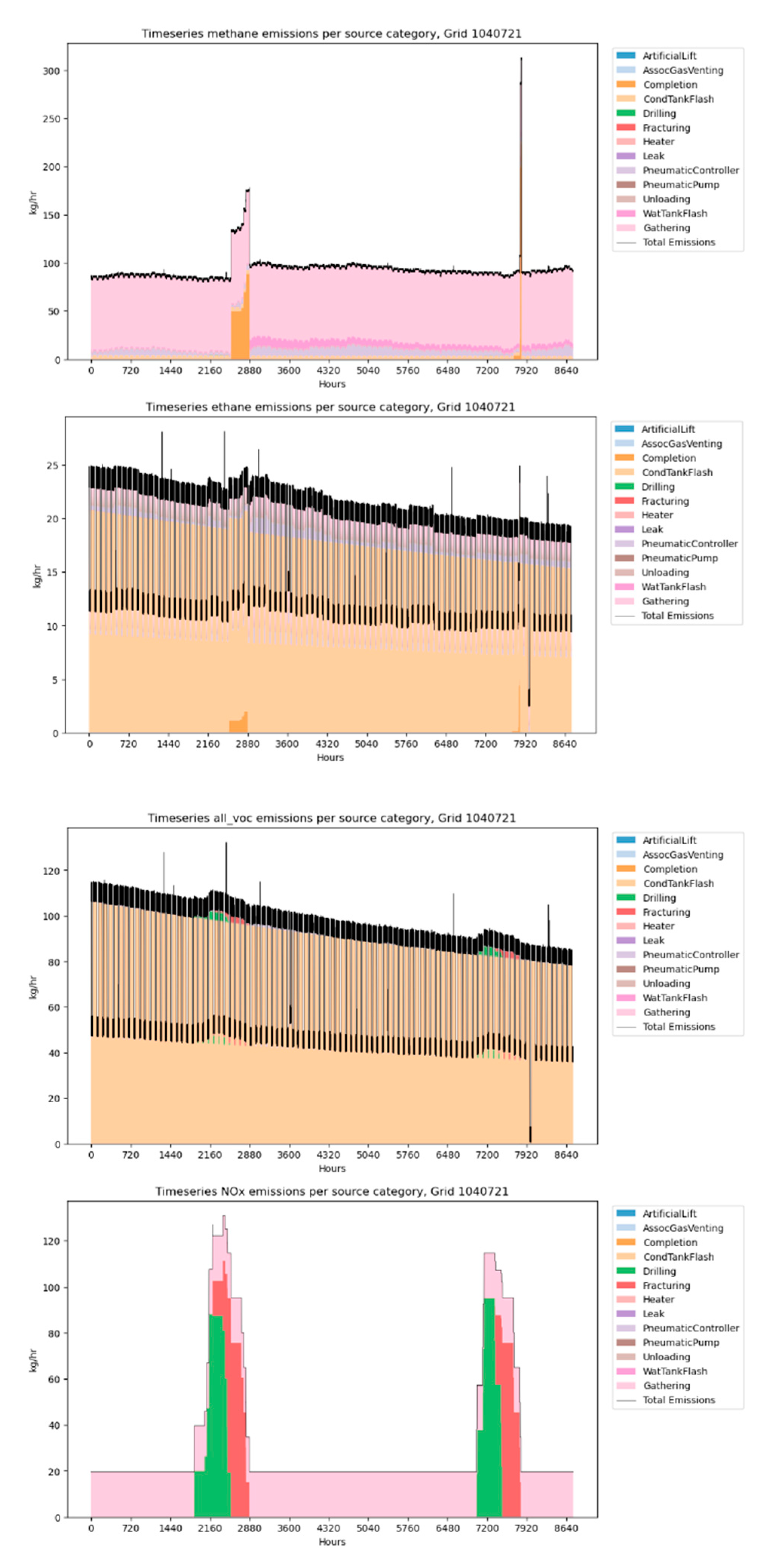

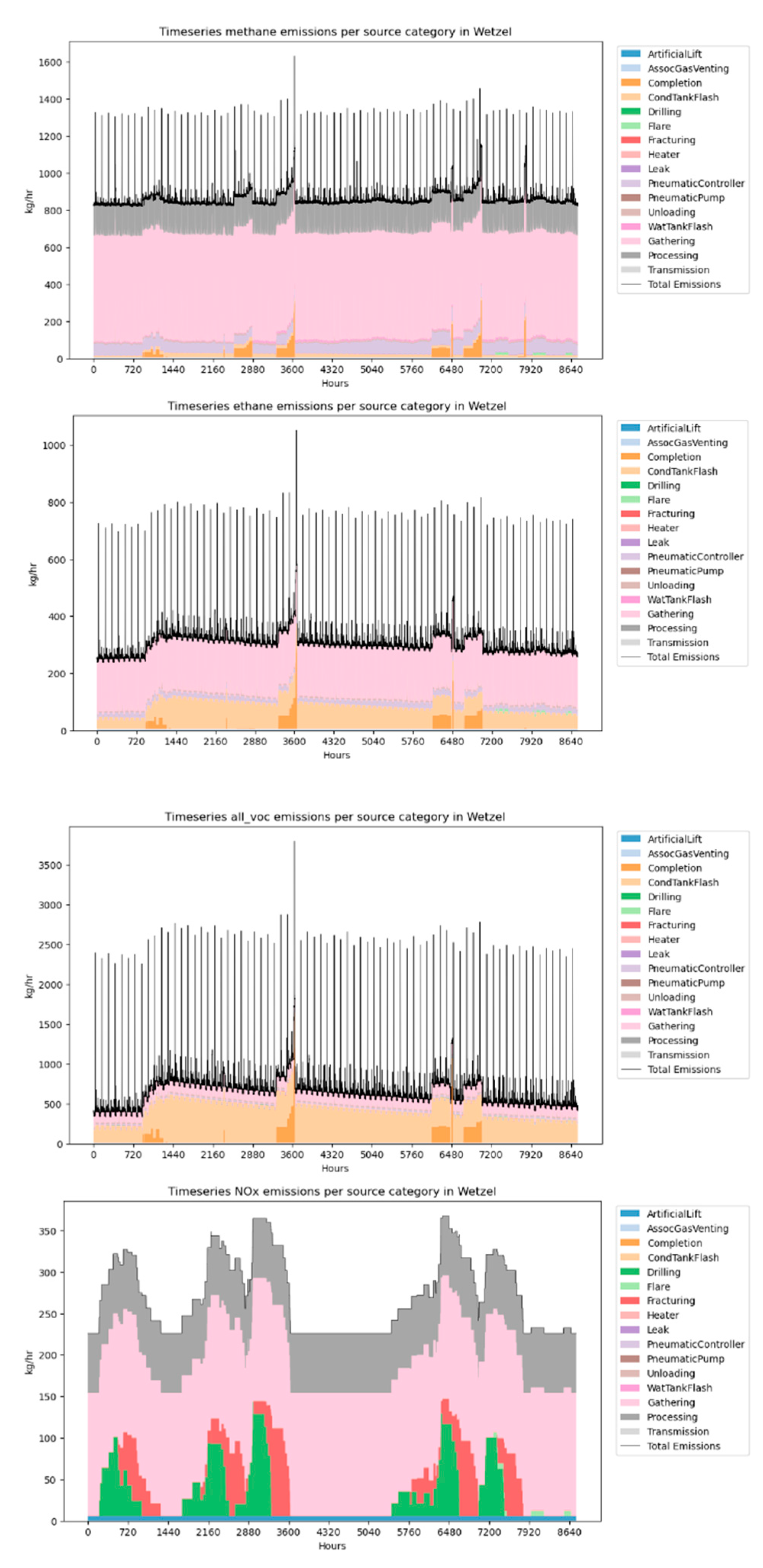

| Emission rates statistics (kg/hr) | mean | median | 75% | 90% | max |

| Basin | |||||

| Methane | 69822 | 69902 | 72811 | 76098 | 93545 |

| Ethane | 16885 | 16668 | 17346 | 18375 | 22613 |

| VOCs | 33898 | 32645 | 35104 | 39678 | 54081 |

| NOx | 13300 | 13331 | 13540 | 13709 | 13997 |

| Wetzel County, WV | |||||

| Methane | 860 | 843 | 864 | 898 | 1629 |

| Ethane | 307 | 300 | 323 | 341 | 1051 |

| VOCs | 651 | 631 | 731 | 803 | 3796 |

| NOx | 272 | 266 | 317 | 337 | 368 |

| Selected grid cell in Wetzel County, WV | |||||

| Methane | 94 | 91 | 96 | 98 | 313 |

| Ethane | 19 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 28 |

| VOCs | 83 | 90 | 100 | 107 | 132 |

| NOx | 34 | 20 | 20 | 95 | 131 |

| Emissions | Basin | Wetzel, WV | Bradford, PA | Distribution of ratios among 173 counties | ||||||

| mean | Std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | ||||

| Methane | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 18 |

| Ethane | 1.3 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 18 |

| VOCs | 1.6 | 5.8 | 2.5 | 5.3 | 6.2 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 5.5 | 41 |

| NOx | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 9.3 |

| Emissions | Selected grid cell | Distribution of ratios among 36 grid cells in Wetzel, WV | ||||||

| mean | std | min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | ||

| Methane | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 4.0 | 24 |

| Ethane | 1.4 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 6.1 | 29 |

| VOCs | 1.5 | 15 | 24 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 19 | 126 |

| NOx | 6.7 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 8.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).