I. Introduction

Natural Language Processing (NLP) has changed significantly since the Turing Test was introduced in the 1950s. This test challenged machines to show intelligent behavior similar to humans. Early NLP systems relied on manual symbolic rules and statistical models to process language. However, these methods struggled with the ambiguity, variability, and context dependence that are common in human languages [

6,

7]. The rise of machine learning, especially deep learning, marked a turning point. Models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their gated versions—Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs)—introduced ways to capture

temporal relationships in text sequences, resulting in better management of sequential data and context compared to earlier methods [

8]. Yet, these models processed data sequentially, leading to computational inefficiencies and limiting their ability to understand long-range dependencies due to problems like vanishing gradients and slow training times.

A significant advance came with the introduction of the Transformer architecture by Vaswani et al. in 2017. This design replaced recurrent operations with self-attention mechanisms that allow parallel processing of input tokens [

1]. As a result, models can assess the importance of all tokens in a sequence at the same time, greatly enhancing efficiency and performance for various NLP tasks. The transformer’s scalability and flexibility served as the basis for Large Language Models (LLMs), which use massive datasets and billions or trillions of parameters to learn rich, contextualized representations of language [

2,

5,

13,

14].

LLMs begin processing text by breaking down input into smaller units, then embedding these tokens into high-dimensional vectors. These embeddings go through multiple layers of multi-head self-attention, feed-forward neural networks, residual connections, and layer normalization [

3]. This deep stack of transformations allows LLMs to capture complex syntactic and semantic patterns, supporting a range of language understanding and generation tasks.

Training LLMs usually involves three key stages:

Pretraining: In this phase, models learn general language patterns by predicting masked or next tokens over large amounts of unlabeled text. They use objectives like masked language modeling (e.g., BERT) or causal language modeling (e.g., GPT) [

10,

27]. This stage is computationally demanding and often requires distributed training on GPUs or TPUs while handling billions of tokens.

Fine-tuning: This step involves supervised training on labeled datasets designed for specific tasks such as question answering, summarization, or code generation. This improves accuracy for those tasks [

15].

Alignment: This newer approach uses reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), direct preference optimization (DPO), and prompting strategies like chain-of-thought to make model outputs clearer, safer, and more aligned with what users expect [

59,

58].

LLMs have achieved impressive results in many NLP benchmarks, setting new records in translation, summarization, and reasoning tasks [

10,

18]. Modern models like GPT-3/4 [

10], LLaMA 2/3 [

64], Falcon 180B [

14], and Claude [

59] demonstrate emergent abilities, including few-shot learning and in-context adaptation, allowing them to perform tasks without extra retraining. Advances in model designs have enabled some LLMs to handle context windows as large as 128k tokens, making it easier to process lengthy documents and multi-turn conversations [

12,

68].

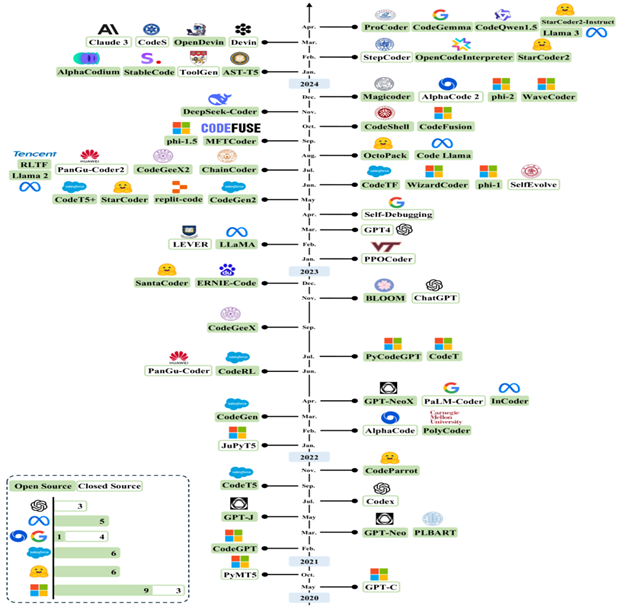

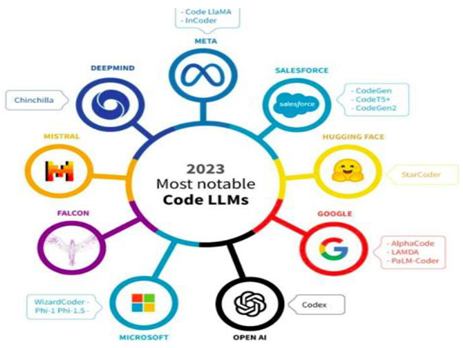

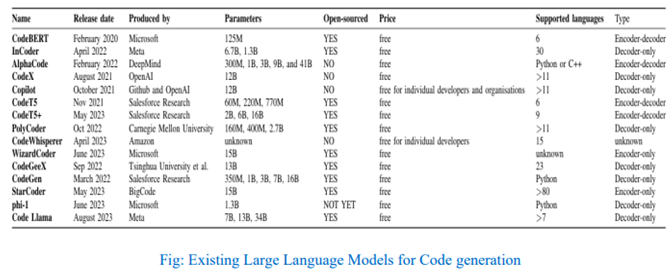

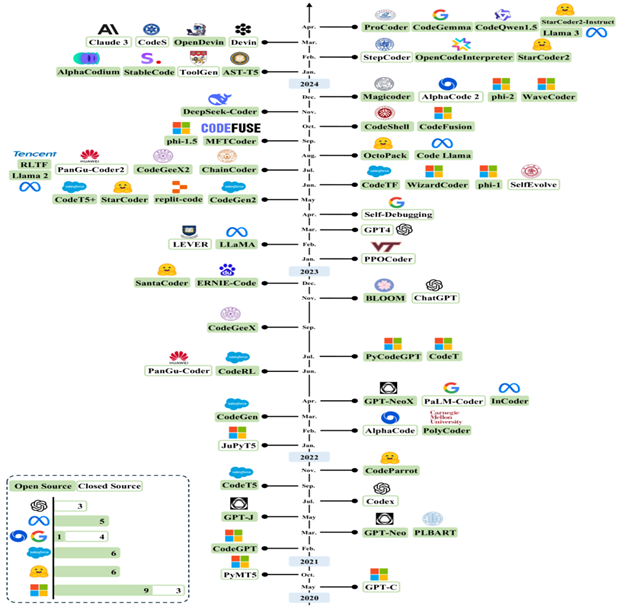

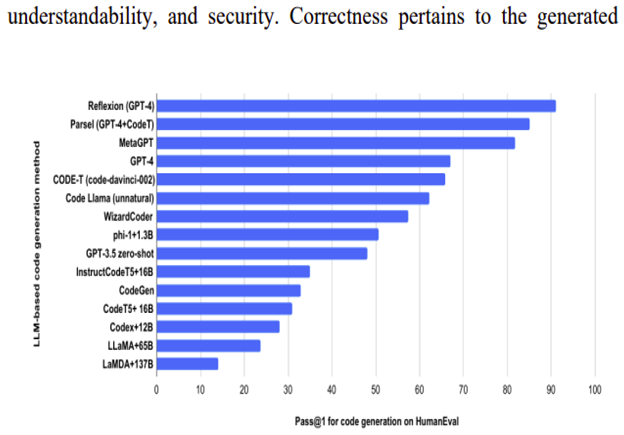

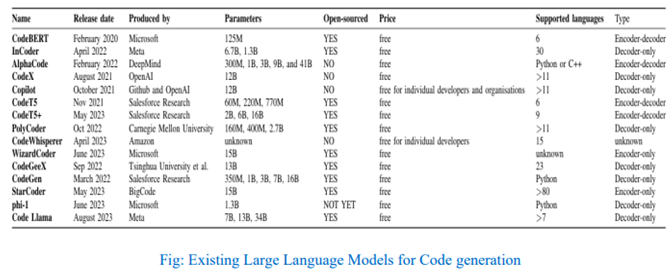

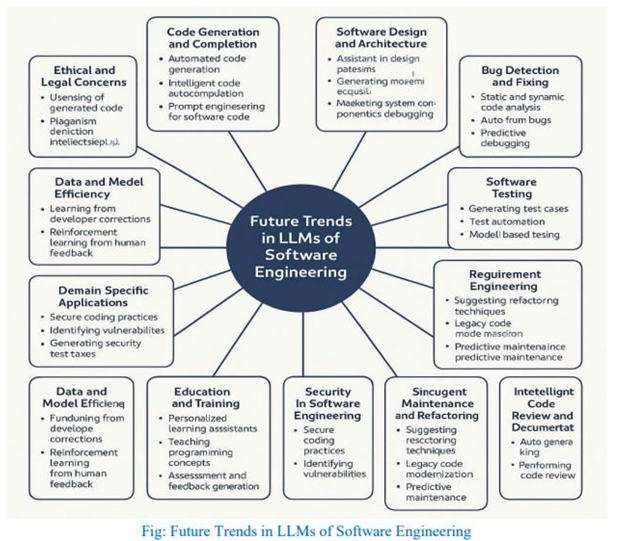

Beyond general NLP, LLMs are transforming software engineering by understanding and generating code. Models such as Codex, CodeT5, and InCoder can write code snippets that are both syntactically correct and semantically meaningful. They assist with tasks like bug detection, refactoring, and documentation [

75,

107,

128]. These features are integrated into developer tools like GitHub Copilot and Visual Studio Code, boosting productivity and collaboration in coding environments [

130]. Their ability to handle multiple languages and frameworks further enhances their value for global development teams [

104].

In cybersecurity, the fast-changing threat landscape—including malware, phishing, ransomware, and supply chain attacks—requires smart and adaptable defenses [

81,

85]. Traditional rule-based systems often struggle to keep up with new threats, prompting the use of LLMs for tasks like threat intelligence analysis, vulnerability scanning, incident triage, and automated penetration testing [

91,

99]. Specialized models like CyberSecBERT and CyberGPT have shown strong results in detecting threats and automating responses [

91,

99].

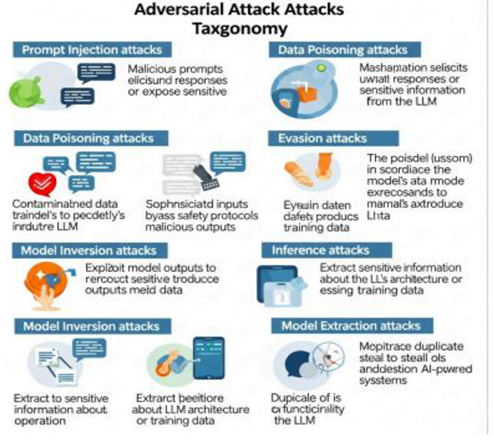

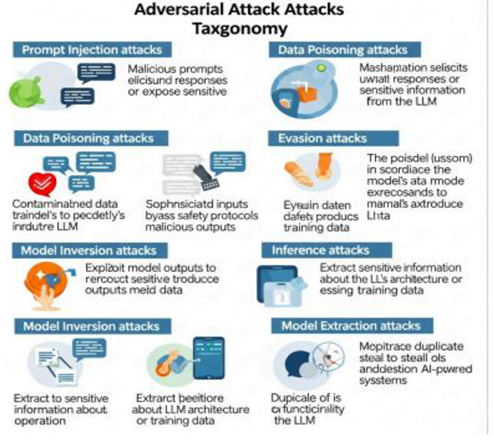

Despite these advances, LLMs also raise new security and ethical issues. Models trained on public data may accidentally memorize sensitive information, creating privacy risks through membership inference attacks or unsafe code generation [

84,

95]. Real-time inference attacks—including prompt injection, adversarial examples, and context poisoning—add extra operational risks [

63,

83]. Additionally, bad actors might misuse LLMs to create phishing campaigns, malware, or misinformation, increasing cybersecurity threats [

88,

96].

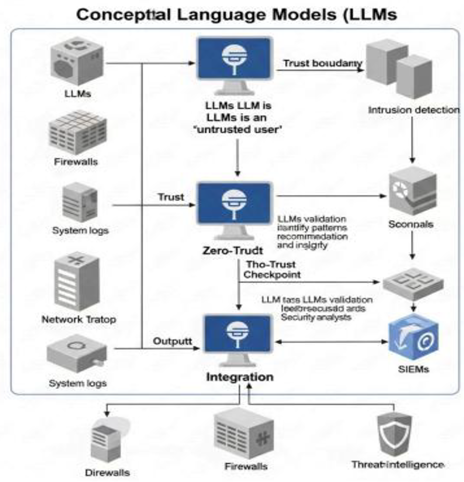

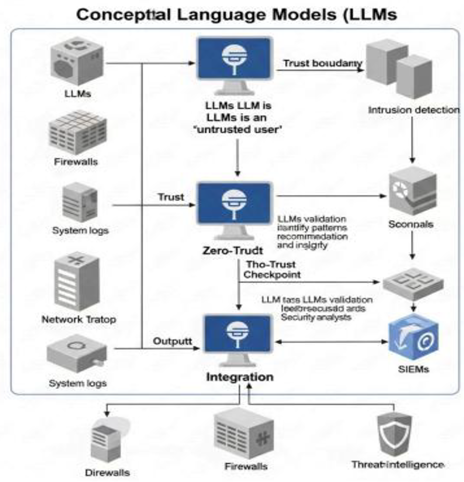

To address these risks, strong strategies are necessary, such as prompt sanitization, context filtering, safety fine-tuning, and using differential privacy methods during training [

65,

66]. Moreover, ensuring model interpretability, validating outputs, and conducting ongoing security audits are important for safe deployment, especially in zero-trust settings [

22,

84].

Research Problem:

Although LLMs have seen considerable success, there is still a lack of comprehensive analysis covering their architectures, training methods, practical applications, and security challenges. Current research often looks at isolated parts without connecting the theoretical foundations to real-world outcomes in software engineering and cybersecurity.

Significance:

As AI becomes more integrated into essential systems, understanding how to maximize the benefits of LLMs while minimizing risks is crucial for advancing automation, security, and ethical AI governance. This insight will help researchers, practitioners, and policymakers build more robust, reliable, and responsible AI systems.

Objectives:

This paper aims to:

Provide a detailed overview of LLM architectures, training techniques, and alignment methods.

Trace the development of LLMs across general-purpose, code-focused, and cybersecurity-oriented models.

Classify known vulnerabilities, attack vectors, and defense strategies targeting LLM systems.

Evaluate the impact of LLMs on software engineering workflows, from requirement analysis to code deployment.

Analyze the role of LLMs in improving cybersecurity threat detection, response, and automation.

Discuss ethical, privacy, and operational challenges in deploying LLMs securely and responsibly.

Contributions:

Our study offers a broad survey that combines theoretical insights with empirical evaluations of 42 major LLMs tested on cybersecurity tasks. We provide a unified framework that connects model design, security issues, and practical applications, giving actionable guidance for safely using LLMs in critical areas. Additionally, we highlight promising research directions aimed at enhancing LLM robustness, adaptability, and ethical deployment.

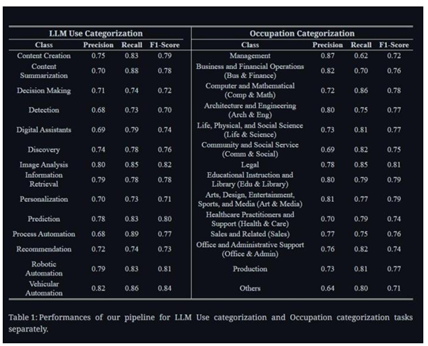

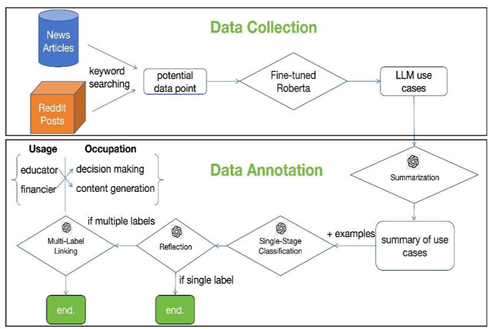

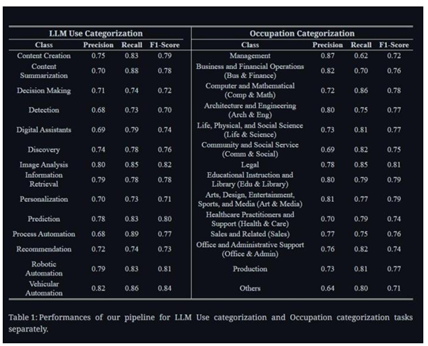

III. Research Outcome And Review

This research offers a detailed overview of Large Language Models (LLMs), tracking their evolution from early statistical methods to modern transformer-based systems. By looking at key components like tokenization, embedding methods, self-attention techniques, and pre training approaches, the paper provides a clear understanding of how current LLMs achieve top performance in natural language processing tasks. The study highlights how the introduction of the Transformer architecture has made it possible for LLMs to scale, be context-aware, and adaptable across various fields.

In reviewing existing models such as BERT, GPT, T5, and LLaMA—both open-source and proprietary—the paper outlines the path of innovation, from bidirectional masked modeling to instruction-tuned and multimodal systems. The comparison of these models, backed by benchmarks like GLUE, HELM, and MMLU, sheds light on their strengths and weaknesses, especially in reasoning, generalization, and safety. The review points out major improvements made possible by large-scale pretraining and fine-tuning. It also discusses the growing significance of prompt engineering and learning from human feedback.

The findings of this study indicate that LLMs are changing software engineering workflows through tasks like code generation, debugging help, and documentation automation. In cybersecurity, LLMs are becoming vital for functions like threat detection, vulnerability assessment, and smart incident response. However, the paper also discusses ongoing risks, including hallucinations, data leaks, prompt-based attacks, and the possible misuse of generative abilities. Current mitigation strategies such as differential privacy, adversarial training, and alignment adjustments are examined within a wider conversation on responsible use.

Overall, the research reinforces the dual nature of LLMs as effective tools for productivity and automation, while also presenting potential security and ethical issues. It stresses the need for clear model evaluation, collaboration across fields, and governance structures that ensure the safe and ethical use of LLMs in real-world applications. By combining a technical review with practical analysis, this study serves as a useful reference for researchers and practitioners looking to push the field forward while upholding accountability and trust in AI systems.

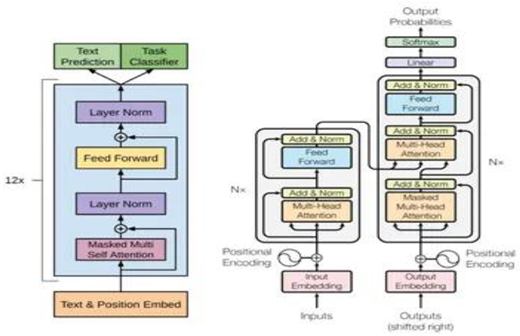

IV. The Large Language Model

Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a significant advancement in the field of artificial intelligence, particularly in natural language processing. These models are designed to generate, understand, and manipulate human language with remarkable fluency. At the heart of modern LLMs is the Transformer architecture, a deep learning model introduced by Vaswani et al. (2017), which replaced traditional sequential models with a parallelizable attention-based mechanism. The Transformer enables LLMs to capture long-range dependencies and semantic relationships across vast amounts of text, making them highly scalable and efficient.LLMs function through several interconnected components: they begin with tokenization and embedding representation to convert raw text into numerical forms, followed by layers of self-attention and multi-head attention to extract contextual meaning. The models are pretrained on massive corpora using unsupervised learning objectives, and later fine-tuned or instruction-tuned for specific tasks. Techniques such as reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) and prompt engineering further enhance their adaptability and alignment with human intent. Today, LLMs are deployed across diverse domains including software engineering, cybersecurity, education, healthcare, and customer service. Their applications range from code generation and text summarization to interactive dialogue and threat detection. For end users, LLMs serve as intelligent assistants that improve efficiency, reduce manual workload, and provide contextual insights.

LLM have rapidly become integral tools in modern life, transforming the way humans interact with technology. Their ability to understand, generate, and process human language allows them to assist in various cognitive and operational tasks. LLMs simplify complex processes, increase productivity, and reduce manual effort across personal and professional domains.LLMs serve as intelligent assistants in a wide range of human-centered tasks by leveraging their advanced language understanding and generation capabilities. One of their most transformative contributions lies in automating repetitive tasks. These models can effortlessly draft emails, generate structured reports, summarize long documents, and manage routine communication, significantly reducing the cognitive and time burden on users. This automation not only boosts individual productivity but also allows professionals to focus on higher-level thinking and strategic decision-making.

In addition to task automation, LLMs enhance decision-making processes by providing real-time insights and synthesizing vast amounts of information into concise, actionable summaries. They can quickly analyze input data, cross-reference it with learned knowledge, and offer contextually relevant suggestions. This functionality is especially valuable in fields like business, healthcare, and education, where timely and informed decisions are critical.

Accessibility is another domain where LLMs demonstrate significant value. Through capabilities like real-time language translation, speech-to-text conversion, and adaptive content generation, they help bridge communication gaps and make information more usable for individuals with disabilities or those who speak different languages. By tailoring responses based on user context, LLMs contribute to creating more inclusive and user-friendly digital experiences.

Moreover, LLMs play a crucial role in boosting human creativity. Whether in writing, coding, design, or music, they offer suggestions, complete partially written content, or generate novel ideas based on a given prompt. By acting as creative collaborators, they can overcome creative blocks and accelerate ideation, making them valuable tools for professionals and hobbyists alike. Finally, LLMs enable seamless and natural communication between humans and machines. Integrated into chatbots, virtual assistants, and conversational interfaces, they allow users to interact with technology using everyday language. This reduces the learning curve and makes complex systems more intuitive to use, enhancing user engagement and satisfaction across various platforms.

LLMs work for us by acting as powerful intermediaries between human intent and computational execution. At their core, these models process user inputs—whether textual commands or spoken language—by interpreting linguistic structure, semantic meaning, and contextual cues to generate coherent, context-aware outputs. The interaction feels natural and human-like because of the sophisticated design principles underlying LLMs.

A fundamental component of this intelligence is the Transformer architecture, which enables LLMs to model complex language patterns and dependencies across long spans of text. Through mechanisms like self-attention and multi-head attention, Transformers allow the model to weigh different parts of the input sequence and understand both local and global relationships in language. This structural design is what empowers LLMs to maintain coherence, track context, and infer user intent effectively.

Before deployment, LLMs undergo extensive pretraining on massive text corpora sourced from books, articles, websites, and code repositories. This phase allows the model to learn the structure of language, general world knowledge, facts, and reasoning strategies. It acquires a statistical understanding of how words, phrases, and concepts are related and used in real-world communication.

After pretraining, models are often fine-tuned on domain-specific datasets to adapt them for specialized use cases—such as legal document generation, clinical report summarization, or software code generation. This targeted fine-tuning sharpens the model’s ability to operate within a particular context, ensuring higher accuracy and relevance in professional applications.

LLMs are also guided by prompting techniques, which involve shaping the model's behavior by carefully crafting input text. Through structured prompts, instructions, or few-shot examples, users can direct the model to perform specific tasks such as translation, question answering, summarization, or creative writing. Advanced prompting strategies have made it possible to use general-purpose LLMs for a wide range of activities without additional retraining. Altogether, LLMs serve as intelligent tools that learn from vast human knowledge and adapt to individual user needs—making them highly versatile agents that enhance productivity, automate tasks, and augment human capabilities in numerous domains.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are revolutionizing a wide range of industries through their ability to understand, generate, and contextualize human language. Their versatility stems from deep pretraining on diverse textual data and their ability to adapt through fine-tuning or prompting. As a result, they serve as intelligent, context-aware assistants capable of performing domain-specific tasks with minimal human intervention. Below is a consolidated overview of the major domains where LLMs are currently applied

In Education, LLMs are transforming learning by acting as personalized tutors. They can explain complex topics in simpler terms, generate quizzes, summarize textbooks, and support students in exam preparation and content creation. Adaptive feedback and multilingual support also make them ideal for inclusive, personalized learning environments.

In Healthcare, LLMs streamline clinical workflows by generating medical notes, summarizing patient histories, checking symptoms, and even supporting diagnostic decision-making. They enhance communication between patients and providers and help with administrative tasks such as insurance coding and claims processing.

Software Engineering has seen rapid adoption of LLMs in tasks like automatic code generation, debugging, writing documentation, and generating tests. These capabilities reduce development time, minimize errors, and augment the productivity of developers, especially in large-scale or open-source projects. In Customer Service, LLMs power intelligent virtual agents and chatbots that can handle queries across multiple languages and platforms. They provide 24/7 support, improve customer satisfaction through personalized interactions, and free up human agents for complex issues.

In the Legal & Compliance sector, LLMs assist with contract analysis, legal research, document summarization, and regulation tracking. They help law firms and corporate legal teams save time and reduce costs by automating document-heavy tasks that traditionally required expert review.

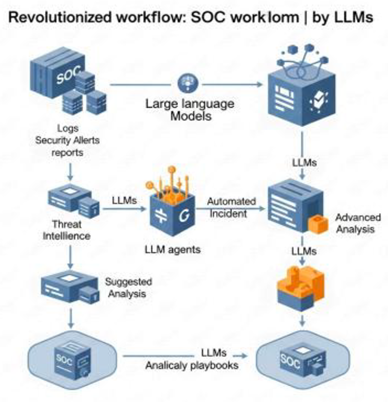

In Cybersecurity, LLMs are emerging as key tools for analyzing log data, identifying threats, summarizing incident reports, and generating security recommendations. They help analysts detect anomalies in real-time and interpret vast volumes of threat intelligence data.

Within the Creative Industries, LLMs fuel artistic and design processes by helping with story generation, music composition, marketing content creation, and even game design. They serve as brainstorming partners and co-creators that can adapt to various creative workflows.

Finance & Banking benefit from LLMs through financial summarization, report generation, risk modeling, and market analysis. They can generate investment memos, simplify financial jargon, and assist analysts in data synthesis and forecasting.

In Human Resources, LLMs are used for resume screening, drafting performance reviews, generating job descriptions, and automating applicant communication—significantly speeding up recruitment cycles and improving candidate experience.

Scientific Research & Academia leverage LLMs for summarizing academic papers, generating literature reviews, drafting manuscripts, and aiding in data extraction from research documents. This facilitates faster and more collaborative research practices.

In E-Commerce & Retail, LLMs personalize shopping experiences by generating product descriptions, automating customer responses, improving search results, and summarizing user reviews—enhancing both sales and customer satisfaction.

Media & Journalism professionals use LLMs to automate headline generation, draft news summaries, transcribe interviews, and fact-check content. These tools allow journalists to focus on investigation and creativity while reducing the time-to-publish.

Finally, in Real Estate & Property Management, LLMs generate property listings, automate responses to prospective buyers, summarize lease agreements, and support customer onboarding with natural language communication.

LLMs serve as transformative tools across disciplines by reducing human effort, accelerating workflows, and enabling intelligent automation. Their ability to interpret natural language, generate relevant outputs, and adapt to domain-specific contexts positions them at the forefront of AI-driven innovation in almost every professional field.

- A.

How LLMs Work

Large Language Models (LLMs) are advanced AI systems designed to understand and generate human language. Internally, they work by processing text in small units called tokens and predicting the most likely next token based on the context of all previous tokens. This process is powered by a special neural network architecture called the Transformer, which uses mechanisms like self-attention to capture complex relationships and dependencies in the text. By training on massive amounts of data, LLMs learn patterns, grammar, and knowledge about language, enabling them to generate coherent and contextually relevant responses one word (or token) at a time.

Tokenization and Embedding in Large Language Models (LLMs)

Large Language Models (LLMs) rely on converting raw natural language text into a numerical format that machines can process. This transformation involves two critical steps: tokenization and embedding.

Tokenization is the initial step that segments raw text into smaller, manageable units called tokens. These tokens serve as the basic input elements for the model. The choice of tokenization strategy greatly affects the model's efficiency and ability to handle diverse language inputs.

Tokens can be whole words, subwords, or individual characters. Traditional word-level tokenization treats each word as a token, but it suffers from issues like a large vocabulary and out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words. Modern LLMs predominantly use subword tokenization methods such as Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) and WordPiece. These approaches split words into smaller, more frequent subword units (e.g., “unhappiness” → “un”, “happi”, “ness”). This method effectively balances vocabulary size and coverage, enabling models to handle rare or new words by composing them from known subwords.

Common algorithms include Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE), which iteratively merges the most frequent pairs of characters or subwords in the training corpus to create a fixed-size vocabulary, WordPiece, which builds the vocabulary to maximize the likelihood of the training data, and SentencePiece, a language-independent method treating text as raw bytes that supports multiple tokenization strategies.

Subword tokenization helps address challenges such as vocabulary explosion, efficient representation of rare words, and improved generalization to unseen text.

After tokenization, each token is mapped to a unique integer ID and then transformed into a dense numerical vector called an embedding. This embedding process enables the model to work with continuous data rather than discrete tokens.

Embedding vectors are high-dimensional continuous vectors (usually 512 to 2048 dimensions) learned during training. They encode semantic and syntactic properties of tokens, such that tokens with similar meanings or usages are represented by vectors close to each other in the embedding space.

These embeddings start as random vectors and are optimized through backpropagation to minimize prediction errors during training.

Since Transformer architectures process tokens simultaneously rather than sequentially, embeddings alone lack positional information. To compensate, positional encodings — either fixed sinusoidal patterns or learned vectors — are added to embeddings to encode the order of tokens, preserving sentence structure and word relationships.

Together, tokenization and embedding convert raw text into a rich, numeric representation that forms the foundation for subsequent Transformer layers to understand context, capture linguistic nuances, and generate coherent language.

Tokenization and embedding are fundamental steps that prepare raw text for Large Language Models by segmenting it into meaningful units and representing those units as continuous vectors in a way that preserves semantic and syntactic information. These processes enable LLMs to efficiently model complex language patterns and perform a wide range of natural language understanding and generation tasks.

Embedding

Embedding is a fundamental step in Large Language Models that transforms discrete tokens into continuous numerical vectors residing in a high-dimensional space

This transformation allows the model to represent semantic, syntactic, and contextual information about language in a form that neural networks can efficiently process.

Each token tit_iti from the vocabulary VVV is mapped to a dense vector

where ddd is the embedding dimension—commonly between 512 and 2048 in modern models. These vectors are learned parameters, stored in an embedding matrix

where

denotes the vocabulary size. During training, the embedding for token tit_iti with index kkk is retrieved as:

Initially, the embedding matrix is randomly initialized and refined through backpropagation to minimize the loss function based on prediction errors. Through this process, embeddings capture rich linguistic features: tokens with similar meanings or syntactic roles become geometrically close in the embedding space. This spatial organization enables the model to generalize knowledge about language patterns beyond the explicit training examples.

One remarkable property of embeddings is their ability to encode semantic relationships via vector arithmetic. For instance, the famous analogy:

illustrates how embeddings can capture gender and royalty relationships in a linear algebraic manner.

Embeddings serve as the input to subsequent Transformer layers, where the model applies self-attention and feedforward operations to build contextualized representations that depend on surrounding tokens. Without embeddings, the model would be unable to process discrete text as numerical data.

In large-scale applications, embeddings generated by LLMs are often stored and queried in vector databases. These databases index high-dimensional vectors and support efficient similarity search using metrics such as cosine similarity or Euclidean distance. Vector databases facilitate tasks like semantic search, recommendation, and clustering by retrieving vectors that are close to a query embedding.

The embedding dimensionality adds a crucial role: higher dimensions can encode more nuanced information but increase computational and storage costs, affecting indexing speed and retrieval accuracy in vector databases. Thus, a balance is required between expressiveness and efficiency.

Adding Positional Encoding

Transformers process input tokens in parallel rather than sequentially, which means they lack inherent information about the order of tokens in a sequence. To address this, positional encoding is added to the token embeddings to provide the model with explicit information about token positions, enabling it to capture the sequential structure of language.

Positional encoding vectors are of the same dimensionality ddd as the embeddings, allowing them to be combined via element-wise addition:

where

ei is the embedding vector for token iii,

pi ∈ ℝ

d is the positional encoding vector corresponding to position iii, and

zi is the resulting position-aware input vector fed into the Transformer layers.

One common approach, introduced in the original Transformer paper (Vaswani et al., 2017), uses sinusoidal functions to generate fixed positional encodings, defined as:

where iii is the token position, kkk indexes the embedding dimension, and ddd is the total embedding dimension. This formulation allows the model to easily learn to attend to relative positions and generalize to sequences longer than those seen during training.

Alternatively, learned positional embeddings can be used, where positional vectors pi are parameters optimized during training, enabling potentially more flexible encoding of positional information.

By integrating positional encodings, Transformers gain awareness of token order despite their inherently parallel architecture, which is crucial for capturing syntax and meaning in natural language.

Contextual Representation

After tokens pass through multiple Transformer layers, their vector representations are no longer isolated embeddings tied solely to the token itself. Instead, each token's vector is dynamically updated to incorporate information from the entire input sequence, resulting in a contextual representation.

This means that the meaning encoded in each token’s vector reflects not only the token’s own identity but also its relationships and dependencies with surrounding tokens. For example, the word "bank" will have different contextual vectors depending on whether the sentence relates to a riverbank or a financial institution, enabling the model to disambiguate meanings based on context.

The process of building contextual representations allows the model to capture syntax, semantics, and subtle nuances such as co-reference and polysemy. As a result, the token vectors become highly expressive and task-relevant, improving performance on diverse language tasks including translation, question answering, and text generation.

These context-aware embeddings serve as the foundation for the final prediction or output generation stages of the model, embodying a rich, holistic understanding of the input text as processed through the deep Transformer architecture.

Next Token Prediction

The ultimate goal of a large language model is to generate or predict the next token in a sequence based on the context established by the preceding tokens. After processing the input through multiple Transformer layers and producing rich contextual representations for each token, the model leverages these vectors to estimate a probability distribution over the entire vocabulary for the next possible token.

This prediction is typically performed by passing the contextual vector of the last token through a linear output layer followed by a softmax function, which converts raw scores (logits) into probabilities. The probability distribution reflects the model’s confidence that each token in the vocabulary could follow the given sequence.

By selecting the token with the highest probability—or sampling from this distribution during generation—the model produces coherent and contextually appropriate text. This step is fundamental to applications such as text completion, machine translation, and conversational agents.

Through training on massive corpora, the model learns complex language patterns and token dependencies, enabling it to make highly accurate next-token predictions that capture grammar, semantics, and even pragmatic nuances.

Generating Output

Once the model predicts the probability distribution over the next token, it must convert this distribution into an actual token choice to generate coherent text. The most straightforward approach is to select the token with the highest predicted probability, known as greedy decoding. Alternatively, the model can sample tokens from the probability distribution to introduce variability and creativity, using methods such as random sampling, top-k sampling, or nucleus (top-p) sampling.

After selecting the next token, it is appended to the input sequence, effectively extending the context for the model. This updated sequence is then fed back into the model, which recomputes the contextual representations and predicts the subsequent token.

This iterative process continues token by token, allowing the model to generate text incrementally and produce coherent, contextually relevant sequences of arbitrary length. The quality and fluency of the generated output depend on the model’s training, architecture, and decoding strategy.

This autoregressive generation process underpins many natural language processing tasks such as language modeling, machine translation, dialogue systems, and creative writing applications.

Training (Self-Supervised Learning)

The model learns by comparing its predicted next tokens against the actual tokens in massive text data, adjusting its internal weights to minimize prediction errors.

Training (Self-Supervised Learning)

Large language models are trained using a self-supervised learning approach, which leverages vast amounts of unlabeled text data without the need for manual annotation. The central training objective is to teach the model to predict the next token in a sequence based on its preceding context, effectively learning language structure and semantics through exposure.

During training, the model processes input sequences and generates predicted probability distributions over the vocabulary for each next token. These predictions are then compared to the actual next tokens in the training data using a loss function, commonly the cross-entropy loss, which quantifies the difference between predicted probabilities and true token identities.

The training process involves backpropagation, where gradients of the loss function flow backward through the network to update the model’s internal parameters—such as weights in the embedding matrix, attention layers, and feedforward networks. Optimization algorithms like Adam are used to adjust these parameters incrementally, minimizing prediction errors over time.

By iteratively processing billions of tokens across diverse text corpora, the model gradually captures rich linguistic patterns, grammar, factual knowledge, and even some reasoning capabilities, enabling it to perform a wide range of downstream language tasks after training.

This self-supervised paradigm is key to the scalability and effectiveness of modern large language models, allowing them to learn complex language understanding without explicit human supervision.

Fine-Tuning & Deployment

Following the initial large-scale pre-training phase, where the model learns general language patterns from extensive and diverse text corpora, fine-tuning is often employed to adapt the model to specific tasks or domains. Fine-tuning involves continuing the training process on a smaller, task-specific dataset, which helps the model specialize and improve performance on particular applications such as sentiment analysis, question answering, or domain-specific text generation.

During fine-tuning, the model’s parameters are adjusted to better capture the nuances and requirements of the target task, often with supervised learning using labeled data. This stage can significantly enhance accuracy, relevance, and efficiency compared to relying solely on the general pretrained model.

Once fine-tuned, the model is deployed in real-world environments where it generates human-like text or provides language understanding capabilities. Deployment can take place on cloud servers, edge devices, or embedded systems, depending on the use case and resource constraints.

In deployment, models are optimized for latency, scalability, and robustness, enabling applications such as virtual assistants, automated content creation, translation services, and more. The ability to fine-tune and deploy flexible large language models has been pivotal in advancing natural language processing technologies across industries.

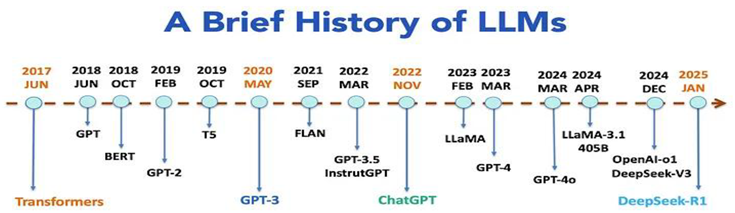

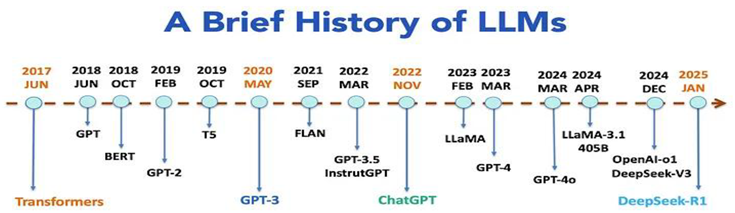

V. The Evolution of LLM

Large Language Models (LLMs) have been one of the biggest advances in AI and natural language processing in the last few years. These models can write coherent text, answer hard questions, translate languages, write code, summarize documents, and even have conversations That sounds a lot like real conversations. They have been successful because they have been able to create better model designs and training methods, thanks to the availability of large datasets and more powerful computers.LLMs did not emerge overnight. It is the outcome of decades of work in deep learning, neural network optimization, statistical language modeling, and computational linguistics. Small datasets, straightforward structures, and strict computational constraints hampered early language models, which frequently produced brittle or grammatically incorrect results. However, language modeling underwent a significant transformation with the advent of deep neural networks, especially transformer-based architectures.

The field of language modeling underwent a significant change beginning with the introduction of the Transformer architecture by Vaswani et al. in 2017. The foundation for the upcoming generation of LLMs was laid by models such as T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer), GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer), and BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers). On a variety of tasks involving the generation and understanding of natural language, these models demonstrated outstanding performance.

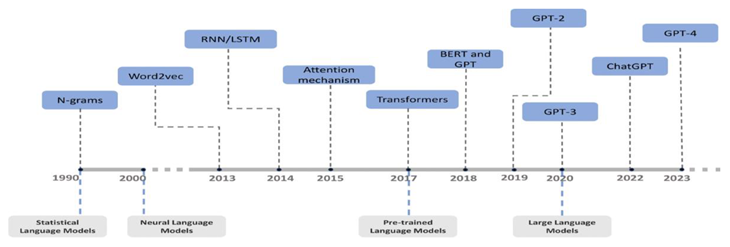

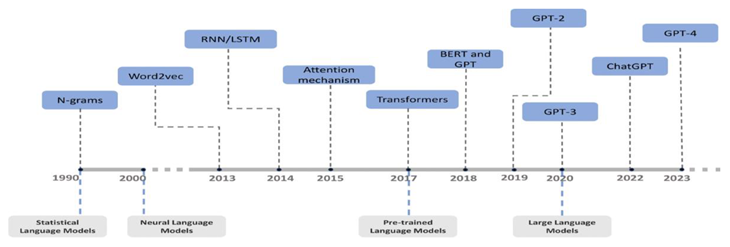

This study maps the evolution of LLMs from the earliest statistical models to the billion-parameter transformers of today. It highlights significant training techniques, architectural advancements, and shifts in research focus that brought large-scale language modeling to its current state. Along with outlining the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead in the continued development of LLM technology, it also addresses the social, ethical, and technical ramifications of applying such potent models in practical applications.

- A.

Early Language Models Before 2017

Natural language processing (NLP) relied heavily on statistical and rule-based techniques prior to the development of large-scale deep learning models. By attempting to use probabilistic methods to capture the structure of language, these early language models laid the groundwork for contemporary LLMs. Despite their apparent simplicity today, these early models significantly advanced our knowledge of language modeling and shaped many concepts found in modern systems.

In early days before large language model era all of the model will trained under statistical and machine learning model.After Transformer model invented,Large language model become growth and growth by passing days.In the early days there are various model was used for trained machine until Transformer model which was developed by Google Inc.After Transformer, Large Language Model become more trending and used.Language understanding systems primarily used symbols in the early days of artificial intelligence. These systems processed language using meticulously crafted grammars, word lists, and sentence structure guidelines. One prominent example is the ELIZA chatbot, which was developed in the 1960s and mimicked conversation using simple scripts and pattern matching. Although rule-based systems were precise and unambiguous in certain contexts, they had trouble scaling up and were unable to accommodate a variety of linguistic inputs.

A move toward statistical language models (SLMs), particularly n-gram models, occurred in the 1990s and early 2000s. These models calculated a word's likelihood by looking at the words that preceded it. For tasks like machine translation and speech recognition, they were straightforward but efficient. For instance, using maximum likelihood estimation or smoothing methods like Kneser-Ney or Good-Turing smoothing, a trigram model would calculate the likelihood of a word based on the two words that preceded it.

Nevertheless, sparsity and context limitations plagued n-gram models. They were less appropriate for complex language tasks since they had trouble capturing long-range dependencies in text. Additionally, their dependence on input windows with a set length limited their capacity for complete idea expression.

Neural language models were developed in response to the limitations of statistical models, and they began to gain traction in the early 2010s. These models employed neural networks to predict the subsequent word in a sequence by representing words as dense vectors, or embeddings. The Neural Probabilistic Language Model (NPLM), first presented by Bengio et al. in 2003, was a seminal work in this field. This model learned distributed word representations and model word sequences using a feedforward neural network.Word embeddings such as Word2Vec (Mikolov et al., 2013) and GloVe (Pennington et al., 2014) represented a significant advancement. Semantically related words appeared near to one another because these models mapped words into high-dimensional vector spaces. This approach greatly enhanced the performance of subsequent NLP tasks and enabled more intricate language representations.

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their enhanced variants, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), gained popularity in order to better capture sequential information. These models maintained a hidden state that contained contextual information while processing input word by word. Even though LSTMs were able to model longer dependencies than conventional RNNs, they were still difficult to train on very long sequences and frequently had issues with vanishing or exploding gradients.

In spite of these issues, LSTM-based models emerged as the top choice for a large number of NLP tasks in the middle of the decade. They were particularly good at text classification, language generation, and machine translation (like Google's sequence-to-sequence model). These architectures facilitated the connection between the transformer-based LLMs that would follow and earlier statistical models.

Even though neural networks significantly improved models, models prior to 2017 still had a number of limitations.

The efficiency of training and parallel processing was restricted by sequential computation.

Their comprehension of global dependencies was limited by brief context windows.

For every new NLP task, task-specific training had to be adjusted from the ground up.

The development of genuinely general-purpose language models was hampered by these constraints. A major shift in model design was made possible by the need for designs that were more flexible, scalable, and context-aware.B. 2.6 The Rise of the Transformer (2017)

The year 2017 was a key moment in the development of language models. Vaswani et al. introduced the Transformer architecture in the important paper “Attention Is All You Need.” This change transformed natural language processing (NLP) by replacing recurrent and convolutional structures with self-attention mechanisms. These mechanisms allowed for the parallel processing of sequences. The Transformer provided a fix for the problems of recurrent models and set the stage for the rapid growth of Large Language Models (LLMs) in the years that followed.

Before the Transformer, most state-of-the-art NLP models were built using Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs). While these models could theoretically model sequences of arbitrary length, they were limited by the need to process tokens sequentially. This led to several critical issues:

Slow training times due to lack of parallelism.

Difficulty capturing long-range dependencies, especially in very long text sequences.

Vanishing gradient problems, making optimization harder over long time steps.

The Transformer architecture was proposed to address these limitations directly. It introduced a novel approach based entirely on self-attention mechanisms, eliminating the need for recurrence and enabling models to process entire sequences simultaneously. This shift allowed for significant improvements in computational efficiency and modeling capacity.

- C.

Core Components of the Transformer

The Transformer consists of an encoder-decoder architecture, although many later models would adopt only one side (encoder or decoder) depending on the task. The key components include:

Multi-Head Self-Attention: Instead of using a single attention mechanism, the Transformer uses multiple attention heads in parallel. This allows the model to learn different types of relationships in the data simultaneously, such as syntactic and semantic dependencies.

Positional Encoding: Since the model lacks recurrence, it cannot inherently understand the order of tokens. To compensate, positional encodings are added to the input embeddings, allowing the model to consider sequence order.Position Encoding is very important .

Feed-Forward Networks: Each layer of the Transformer includes position-wise feed-forward neural networks that add non-linearity and increase model capacity.

Layer Normalization and Residual Connections: These additions stabilize training and allow gradients to flow more effectively through deep networks.

By combining these components, the Transformer achieved state-of-the-art performance across a range of NLP tasks while being faster and more scalable than its predecessors.Transformar is the heart of large language model.Without Transformer model Large language model cant be efficiently work or doing of our task.After Transformar Large Language Model growth more.

The original Transformer model was tested on tasks like English-to-German and English-to-French translation. It outperformed the previous top models in both quality and training speed. The Transformer required much less time to train and could generalize better with large datasets.

This success showed that self-attention was not just a new concept but a strong modeling approach that could be scaled up effectively. The architecture quickly gained a lot of attention and became the standard for a new generation of NLP models.

Perhaps the most important legacy of the Transformer architecture is that it became the foundation for all subsequent large language models. This includes:

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) - which used the encoder.

GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer) - which used only the decoder.

T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) - which used the full encoder-decoder stack.

These models changed the Transformer structure for different purposes. BERT focused on understanding through masked language modeling, while GPT centered on generation with autoregressive modeling. Still, they all relied on the scalability and flexibility of the Transformer for their success.

A key feature of the Transformer was its ability to scale efficiently with data and computation. The architecture allowed for full parallelization during training, making it more effective at using modern GPU/TPU hardware than RNNs. This enabled training on massive datasets and the growth of model sizes from millions to billions, and eventually trillions, of parameters.

Additionally, the quadratic time complexity of self-attention seemed like a drawback at first. However, the benefits in performance and model quality proved to be worth the cost, especially as hardware and optimization methods advanced.

- E.

Industry Adoption and Research Momentum

After the original Transformer paper came out, both academia and industry quickly embraced the architecture. Companies like Google, OpenAI, and Facebook incorporated Transformer models into their systems for tasks such as translation, search, summarization, and recommendation.

Research also changed significantly, focusing more on Transformer-based models. The number of publications that mentioned the Transformer architecture surged in the following years. This growth indicated a new research path focused on scaling and fine-tuning large Transformer-based models for general language understanding and generation.

- D.

BERT and Bidirectional Representations (2018)

While the Transformer architecture laid the groundwork for deep learning in NLP, its full potential for language understanding was realized with BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), introduced by Devlin et al. in 2018. BERT changed the way language models were trained and used. It shifted from task-specific models to pretrained, general-purpose representations. Its success initiated the “pretrain-then-finetune” approach, which became a defining feature of modern LLMs.

Before BERT, most language models, like GPT-1 and earlier RNN-based models, operated in one direction. They processed text from left to right or right to left, predicting the next word based on previous context. While this worked well for generating text, these models struggled to capture bidirectional context. This context is crucial for many understanding tasks, like question answering and sentiment analysis.

BERT was created to address this issue. It provided deep bidirectional context by allowing each token to consider all others in both directions at the same time. This approach helped the model gain a richer, more complete understanding of the input sequence. Unlike left-to-right models, BERT could take into account the entire context of a word's surroundings when forming its representation. This significantly boosted performance on a variety of natural language understanding (NLU) tasks.

BERT introduced two new training goals that became standard in future language models:

Masked Language Modeling (MLM): During pre training, 15% of the tokens in each input sequence are randomly replaced with a special [MASK] token. The model is then trained to predict the original token based on its bidirectional context. This technique lets the model learn deep semantic and syntactic patterns without being limited to sequential order.

Next Sentence Prediction (NSP): To help the model understand sentence relationships, which is important for tasks like natural language inference, BERT is trained to predict whether one sentence follows another in a coherent context. This binary classification task improves the model’s understanding of discourse-level relationships.

Together, these goals allowed BERT to learn general-purpose language representations that could then be fine-tuned with little supervision on specific tasks.

Pretraining and Fine-Tuning Paradigm

BERT’s success led to a two-stage process that became key to modern NLP systems:

Pretraining on large datasets like English Wikipedia and BooksCorpus using self-supervised learning tasks (MLM and NSP).

Fine-tuning the pretrained model on downstream tasks, such as sentiment classification, named entity recognition, and question answering, with a small amount of labeled data.

This approach proved much more data-efficient than training models from scratch and significantly lowered the need for task-specific designs. Fine-tuned BERT models quickly set new records across benchmarks like GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation), SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset), and SWAG

BERT's impact was immediate and extensive. It not only achieved top results across many NLP tasks, but it also:

Standardized the use of Transformers for understanding tasks.

Triggered a wave of derivative models such as RoBERTa (by Facebook), ALBERT (by Google), and DistilBERT (by Hugging Face). Each of these modified BERT’s architecture or training method to improve performance or efficiency.

Became the main base model for academic research and industrial applications.

For example, RoBERTa removed the NSP objective and trained longer on more data, which led to better performance. ALBERT introduced weight-sharing and factorization to lower the parameter count without losing accuracy. These variations showed the strength and flexibility of BERT’s main ideas.

Before BERT, transfer learning was not widely used in NLP compared to computer vision, where pretrained models like ResNet and VGG had been popular for a long time. BERT showed that transfer learning in NLP was not only possible but also very effective. It became common to pretrain large models once and reuse them across hundreds of tasks, saving significant time and computational resources.

Additionally, BERT allowed low-resource tasks and languages to benefit from pre trained knowledge. Fine-tuning a single multilingual BERT (mBERT) model let users apply it across many languages, even those with few labeled datasets.

2.15 The GPT Series: Autoregressive Growth

While BERT introduced powerful bidirectional representations for language understanding, OpenAI’s Generative Pretrained Transformer (GPT) series took a different path, focusing on causal (autoregressive) modeling to excel in language generation. Starting with GPT-1 in 2018, the series quickly evolved through GPT-2 (2019), GPT-3 (2020), and eventually to GPT-4 and GPT-4o (2023-2024). This evolution showcased rapid growth in model size, capabilities, and real-world impact. The GPT models confirmed the usefulness of scaling laws, led to a surge of generative AI applications, and fundamentally changed how humans interact with AI.

GPT-1, introduced in June 2018 by OpenAI, was the first large-scale Transformer-based autoregressive language model. Unlike BERT, which focused on understanding in both directions, GPT-1 used a unidirectional (left-to-right) training approach. The main idea was straightforward but transformative: pretrain a decoder-only Transformer on a large text set using a next-word prediction task, then fine-tune it on downstream tasks with supervised data.

GPT-1 had 117 million parameters and was trained on BooksCorpus, which contains over 7,000 unpublished books. Although it was relatively small, GPT-1 showed that a single pretrained model could generalize across tasks such as sentiment classification, question answering, and textual entailment with few changes to the task-specific architecture.

The success of GPT-1 confirmed that:

- -

Autoregressive modeling can achieve strong performance in language understanding and generation.

- -

-Transfer learning works in both directions; models trained for generation can also be used for understanding tasks.

OpenAI released GPT-2, a much larger successor with 1.5 billion parameters trained on WebText, a curated dataset of web pages. GPT-2’s architecture expanded on GPT-1 by increasing its depth, width, and training duration. It maintained the same decoder-only, left-to-right causal Transformer design.

GPT-2 marked a significant moment in AI history for several reasons:

- -

It showed that increasing model size and data volume leads to new behaviors, such as coherent multi-paragraph text generation, zero-shot learning, and in-context reasoning.

- -

OpenAI initially withheld the full model due to concerns over misuse, including disinformation, spam, and automation of fake content. This sparked one of the first major ethical debates about generative models. The model was assessed in both zero-shot and few-shot contexts, where tasks like translation, summarization, and comprehension were attempted without specific training data. GPT-2’s performance in these areas indicated the early signs of general-purpose language ability, although it still fell short compared to fine-tuned models on benchmarks.

2.15 GPT-3: Emergence of Few-Shot Learning

Released in mid-2020, GPT-3 changed the game. With 175 billion parameters, which is over 100 times larger than GPT-2, GPT-3 was trained on a mix of Common Crawl, Wikipedia, books, and other large web datasets. It kept the same Transformer decoder-only structure but pushed the limits of model scaling to a new level.

The most surprising result from GPT-3 was its ability to learn from just a few examples in the input prompt. This in-context learning allowed GPT-3 to tackle tasks like:

- -

Arithmetic and logic puzzles

- -

Translation and summarization

- -

Programming and code completion

- -

Question answering and essay writing

This behavior indicated that the model learned abstract task structures simply from a large amount of language exposure, without needing explicit updates. GPT-3 blurred the line between training and inference, making prompt engineering an important skill for working with language models.

Despite its strengths, GPT-3 also showed several weaknesses:

- -

Lack of consistent reasoning

- -

Susceptibility to prompt sensitivity and incorrect information

- -

Difficulty verifying facts or performing reliable multi-step logic

Still, it formed the basis for many commercial products and APIs, such as OpenAI’s Codex for code generation and ChatGPT for conversations.

In 2023, OpenAI launched GPT-4, a model that kept some details about its size and architecture secret but offered significant performance improvements across the board. It showed:

-Greater factual accuracy

-Fewer hallucinations

-Better support for multiple languages

-More stable behavior across different prompts

More notably, GPT-4 was succeeded by GPT-4-turbo and GPT-4o (omni), which brought multimodal capabilities. This meant accepting not just text but also images, audio, and for GPT-4o, video and live interaction. GPT-4o could process and respond to spoken language and visual inputs in real-time, moving LLMs closer to human-like multimodal understanding.

These newer models also included instruction tuning and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) to better match model behavior with user needs and ethical standards, greatly improving their usability for interactive agents and business applications.

The GPT series provided strong evidence supporting scaling laws, which show that model performance improves as compute, data, and parameters increase. This finding shaped the design of even larger models and led to the idea that “more is different,” where qualitative changes in behavior, like reasoning or abstraction, come from purely quantitative scaling.

Throughout the GPT series, the decoder-only Transformer architecture remained the same, proving it is durable and versatile. The successes of GPT-3 and GPT-4 confirmed that autoregressive language modeling is not only effective for generating text but also capable of zero-shot reasoning, language understanding, and multimodal grounding when scaled appropriately.

The GPT series ushered in the era of generative AI, transforming multiple industries including education, healthcare, law, customer service, and software development. Tools like ChatGPT, GitHub Copilot, and Microsoft Copilot have demonstrated how autoregressive LLMs can augment human productivity at scale. The release of GPT-3 and GPT-4 also reignited debates about AI alignment, misinformation, intellectual property, and labor displacement, prompting global discussions on how to govern and regulate powerful language technologies.

- F.

The Rise of Open-Source Language Models

While large corporations and closed-source research groupsinitially dominated the field of LLMs, the rise of open-source large language models has greatly increased access to advanced NLP technologies. This movement encourages transparency and reproducibility and drives innovation. It allows independent researchers, small businesses, and academic institutions to explore and build on powerful language models.

The open-source LLM movement dates back to earlier pre-transformer models like GloVe, word2vec, and ELMo. These models were released to the public and became widely adopted. However, significant momentum began to build with the development of Transformer-based models. The release of BERT in 2018 by Google marked a major breakthrough in this new era. BERT's source code and pretrained weights were made publicly accessible, leading to a surge in derived models, research papers, and real-world applications.In the following years, Hugging Face’s Transformers library played a key role in shaping the open ecosystem. By standardizing model APIs and hosting thousands of community-shared models, the library lowered barriers to entry and encouraged rapid experimentation. Researchers could now load and fine-tune models with just a few lines of code.

After OpenAI released GPT-3 in 2020 without open weights or training code, several research groups started developing open-source alternatives. These efforts aimed to replicate or closely match the capabilities of proprietary models while promoting transparency and independent validation.

Some key milestones include:

- -

GPT-Neo and GPT-J (2021) by EleutherA: These were some of the first serious attempts to create open GPT-3-style models. GPT-J reached 6 billion parameters and displayed impressive zero-shot capabilities.

- -

GPT-NeoX-20B (2022): This 20-billion-parameter model was trained with open tools and datasets. It matched or outperformed GPT-3 on certain benchmarks while staying freely accessible.

- -

OPT (Open Pre-trained Transformer, 2022) by Meta AI: Meta released a group of decoder-only language models with up to 175 billion parameters to allow researchers to study the behavior of large-scale LLMs. This included transparent training logs and evaluation metrics, marking a significant achievement in open AI research.

- -

BLOOM (2022) by BigScience: Trained by over 1,000 researchers from 70 countries, BLOOM became the first multilingual open LLM with up to 176 billion parameters. It supported over 40 languages and was trained on open data with open governance, highlighting the strength of community-driven research. These models showed that high-quality LLMs could be trained and released openly without sacrificing performance. This sparked a surge of innovation, reproducibility, and ethical discussions.

In early 2023, Meta released LLaMA (Large Language Model Meta AI), which included a series of compact yet powerful language models ranging from 7 billion to 65 billion parameters. Unlike earlier models that focused on large-scale performance, LLaMA models were designed to be efficient and accessible to researchers with standard hardware. LLaMA models outperformed GPT-3 despite their smaller size, thanks to more advanced pre-training methods and better architectural tuning.Although initially limited to non-commercial use, the leak of LLaMA weights led to a major shift. Developers quickly adjusted and fine-tuned LLaMA to create variants such as:

- -

Alpaca (Stanford): Fine-tuned LLaMA using instruction-following data, creating lightweight ChatGPT-style assistants.

- -

Vicuna (UC Berkeley): Built on LLaMA with conversational tuning, closely mimicking ChatGPT-level interactions.

- -

WizardLM, Orca, Koala, Baize: Community-created instruction-tuned LLMs developed from LLaMA and its derivatives, each adding unique features like reasoning or multi-turn dialogue.

In response, Meta released LLaMA 2 in July 2023 under a more flexible commercial license. LLaMA 2 models (7B, 13B, and 70B) showed excellent performance on both general NLP tasks and dialogue generation. Their release marked a new era, allowing companies, governments, and researchers to use cutting-edge LLMs without relying on proprietary APIs.

The growth of open-source LLMs has been boosted by strong tools and infrastructure. Here are some examples:

Hugging Face Transformers: The main hub for open models, datasets, tokenizers, and evaluation tools.

PEFT (Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning) and LoRA: Techniques to fine-tune large models with minimal computing power by updating only a small number of parameters. RLHF pipelines: Open versions of reinforcement learning with human feedback, allowing developers to align models with user preferences.

Open LLM Leaderboards: Platforms like LMSYS and Hugging Face's leaderboard now rank open models based on standards like MMLU, ARC, and HELM. These tools enable independent teams to train, fine-tune, and deploy state-of-the-art language models on limited resources.

Open-source LLMs have made language intelligence accessible to more people. Startups, educators, developers, and nonprofits can now create LLM-powered applications without depending on centralized providers. This shift drives innovation, encourages localization

However, open-source development also brings specific risks: The spread of unsafe or unaligned models due to the lack of safeguards. Security dangers, such as LLMs being used for phishing, malware creation, or spreading false information.

Resource inequality, where only a few organizations can afford to train models with more than 100B parameters.License fragmentation, with some models having unclear or restrictive terms.

These challenges call for shared governance, improved alignment techniques, and open collaboration among academia, industry, and society.

The landscape of large language models (LLMs) in 2025 is defined by rapid diversification, agent, and a major shift toward user-controllable, specialized, and effective models. As foundational models become common, research and industry are shifting focus from scale to capability, usability, and alignment. Below are the most significant trends shaping the LLM space in 2025.

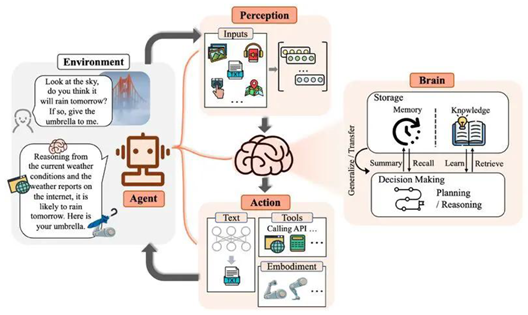

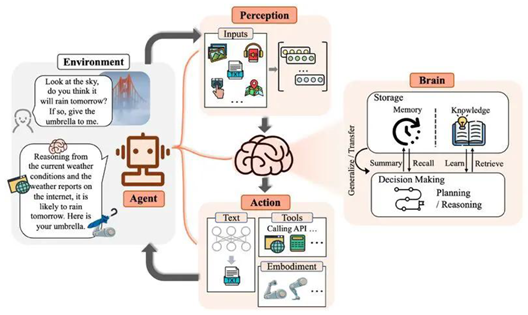

One of the key changes in 2025 is the move from passive LLMs to agentic LLMs, which are models that can reason, plan, and interact on their own in digital environments. Supported by frameworks like OpenAI’s GPT-4o Agents, Meta’s LLaMA Agent, and Autogen by Microsoft, these systems can browse the internet, manage files, trigger APIs, and carry out multi-step tasks with little supervision. This new agent approach is transforming fields like coding, data analysis, customer support, and virtual robotic process automation (RPA).Agent becomes more popular after LLM becomes popular.Agent becomes very helpful in our normal days.A LLM agent is an autonomous system powered by a large language model. It can perceive inputs, reason about tasks, and take actions, often by calling tools or APIs. Unlike basic chatbots, LLM agents can plan multi-step tasks, interact with external environments, and change as needed. They are often used in AI workflows such as automation, coding assistants, or independent research agents.After the success of models like GPT-4o and Gemini 1.5, real-time multimodal LLMs have become standard in 2025. These models can process live video, audio, images, and text at the same time, allowing for applications in telemedicine, tutoring, smart surveillance, and assistive technology. For example, GPT-4o can engage in natural voice conversations, understand screenshots, interpret visual documents, and respond in milliseconds, paving the way for a new type of interactive AI assistant.

As general-purpose models become saturated, 2025 is seeing a rise in domain-specific LLMs that are often fine-tuned on industry-specific datasets. From legal and biomedical LLMs, such as BioLLaMA and LegalMistral, to localized language assistants that support underrepresented languages and dialects, researchers are utilizing open checkpoints like Mistral, LLaMA 3, and Phi-3 to create models suited for specialized, high-accuracy use.

The competition for context window length has intensified, with Claude 3.5, GPT-4o, and Mamba models supporting over 1 million token context lengths. Furthermore, vector-based retrieval is being closely integrated, allowing for semantic memory and long-term reasoning. Instead of recalculating answers, models can dynamically retrieve past conversations, documents, or facts, mimicking the ability to "think over time."

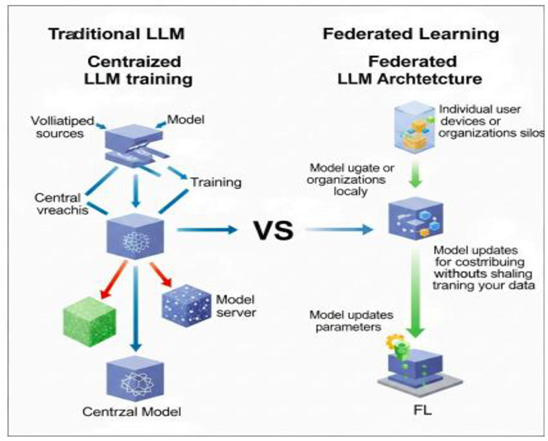

In response to increasing privacy and latency concerns, on-device LLMs are gaining popularity in 2025. Models like Gemma, TinyLLaMA, and EdgeGPT now operate on smartphones, laptops, and IoT devices with impressive accuracy and near-instant inference. This enables local, offline AI, which is crucial for privacy-sensitive sectors such as healthcare, finance, and government services.

With rising global regulation, LLM alignment and safety are significant research areas. Tools like HELM, Open LLM Arena, and LMSYS Chatbot Arena are used to compare models for helpfulness, honesty, and harmlessness. In 2025, scalable oversight, constitutional AI, and autonomous alignment loops are central to responsible development.

In this part, we traced the history of large language models (LLMs) from early rule-based systems to modern transformer-based architectures. We discussed key advancements like attention mechanisms, pretraining, and fine-tuning, which allowed for the development of general-purpose models. We also highlighted how open-source ecosystems have made LLMs more accessible and adaptable. Finally, we examined the latest trends in 2025, including real-time multimodal models, agent-based systems, domain-specific fine-tuning, and on-device deployment. This shows a shift toward smarter, more interactive, and efficient AI.

VI. Role in Cybersecurity

Large Language Models (LLMs) have truly changed the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and show great promise in improving our cybersecurity defenses. These models excel at processing and understanding large amounts of text. This makes them essential for any language-related task. The key behind LLMs is their foundation: deep neural networks trained on massive datasets and a specific architecture called the "transformer."

This transformer uses a smart "self-attention" mechanism that helps the model determine the importance of different words in a sentence, allowing it to understand their context. This innovative architecture, especially the transformer's self-attention, enables LLMs to achieve "human-like language understanding and predictive capabilities." It is not just a technical detail; it means LLMs can go beyond strict rules and recognize complex, evolving attack patterns.

Older models, like RNNs and LSTMs, struggled with remembering long sequences and processing information in parallel. Transformers, with their self-attention, surpassed these limits and can understand context over very long text spans. This deep contextual awareness allows LLMs to detect subtle, evolving attack patterns and vulnerabilities from unstructured security data, which is a major improvement over traditional signature-based methods.

This capability means LLMs can identify hidden attack patterns, examine how attackers behave, predict future threats, and even provide real-time defensive support.

This research summary will systematically explore the exciting possibilities and practical applications of LLMs in cybersecurity. We'll weave together insights from network security, artificial intelligence, and even human-centered design. The report will bring together the latest research, highlight the main challenges, and point towards future directions for using LLMs in network security, combining views from universities, industry, and government.

A. LLMs Superpower for Cybersecurity

LLMs are very good at understanding natural language. They can grasp context and subtle meanings, which lets them produce responses that feel quite human and relevant. This makes them essential for analyzing and interpreting security reports, threat intelligence, and log files effectively. Their versatility means they can handle a wide range of tasks, generating text.

Summarizing, translating, and answering questions all happen without needing specific training for each task. In cybersecurity, this means creating security policies, writing

code, or even crafting malicious prompts, which we will discuss later. Large language models (LLMs) can handle routine tasks like summarizing and rephrasing content. This is a big help for writing reports and analyzing security incidents.

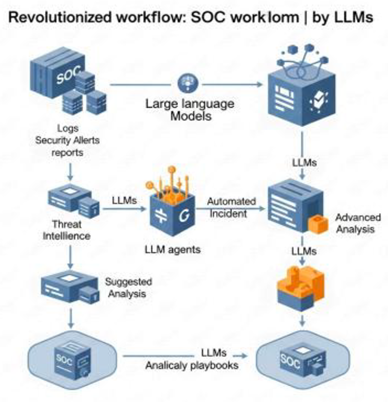

A new type of model, called "agentic LLMs," is becoming an important tool. These models can automate complex tasks and support reasoning-driven security analysis. They can break down complicated, multi-step security problems into smaller, more manageable parts. This leads to more structured and logical solutions. This shift means LLMs are not just processing text anymore; they are evolving into automated or semi-automated systems that can make complex decisions and interact with the outside world. This fundamentally changes how security operations are conducted.

While traditional LLMs mainly do text-in, text-out tasks, agentic LLMs include planning modules, memory systems, and tool integration. This allows them to plan actions based on natural language input and interacting with the external world. This ability is important for automating multi-step security workflows, such as complete incident response playbooks or penetration tests. They go far beyond just analyzing reports.learning and adaptation process that static rules simply can't offer.LLMs can develop effective anomaly detection systems by constantly monitoring network traffic, system logs, and user behavior. This helps in early threat detection. They can uncover hidden attack patterns and vulnerabilities by sifting through historical data.

LLMs can identify "unusual patterns or deviations from the norm." This shifts cybersecurity from merely reacting to known attacks to proactively spotting threats before they fully emerge. This represents a significant improvement compared to traditional signature-based detection, which often falls behind new attack variations. Traditional methods depend on predefined rules or signatures. New, unseen attacks can bypass these. LLMs, trained on large datasets, learn what is "normal" and can detect subtle anomalies that do not match any known signatures. This ability makes it possible to catch zero-day threats or novel attack patterns. This capability provides continuous monitoring.

LLMs can develop effective anomaly detection systems by constantly monitoring network traffic, system logs, and user behavior. This helps in early threat detection. They can uncover hidden attack patterns and vulnerabilities by sifting through historical data.

LLMs can identify "unusual patterns or deviations from the norm." This shifts cybersecurity from merely reacting to known attacks to proactively spotting threats before they fully emerge. This represents a significant improvement compared to traditional signature-based detection, which often falls behind new attack variations. Traditional methods depend on predefined rules or signatures. New, unseen attacks can bypass these. LLMs, trained on large datasets, learn what is "normal" and can detect subtle anomalies that do not match any known signatures. This ability makes it possible to catch zero-day threats or novel attack patterns. This capability provides continuous monitoring.

| Cyber Attack Phase |

Task Category |

Detection Target |

Detection Approach |

Techniques |

| Reconnaissance |

System-based Reconnaissance Detection |

Advanced adversaries in Smart Satellite Networks |

Transform network data into contextually suitable inputs |

Transformer-based MHA |

| |

System-based Reconnaissance Detection |

Malicious user activities |

Use three self-designed agents to detect log les |

CoT reasoning, PbE paradigm, EMAD mechanism |

| |

System-based Reconnaissance Detection |

Aack early detection, threat intelligence gathering, aacker's behavior analysis |

Use LLM-based honeypot to simulate realistic shell responses |

CoT prompting, Few-shot learning, Session management |

| |

Human-based Reconnaissance Detection |

Malicious web pages |

Use question-and-answer detection example to guide LLM |

K-means clustering, Few-shot Prompting |

| |

Human-based Reconnaissance Detection |

Phishing Sites |

Translate email into LLM-readable format and use CoT |

Prompt Engineering, CoT prompting |

| Foothold Establishment |

Malware Detection and Analysis |

Malicious software (code snippets, textual descriptions) |

Analyze textual descriptions and code snippets |

BERT fine-tuning |

| |

Vulnerability Detection and Repair |

Security aws in code repositories and bug reports |

Analyze code, identify patterns, generate patches |

GPT-3, Prompt Engineering, Semantic Processing |

| Lateral Movement |

Security |

Anomalies in network trace and logs |

Continuously monitor network tracking, system logs, user behavior |

Advanced anomaly detection systems |

| |

Incident Response Automation |

Critical events, security reports, logs |

Assess and summarize events, generate scripts, aid report writing |

LLM agents, Knowledge management |

| |

Penetration Testing |

Complex, multi-step, security-bypassing |

Automate creation and analysis of code call chains |

PentestGPT, Chain-of-Thought prompting |

LLMs are better at detecting phishing attempts by analyzing the content of emails and messages. They identify suspicious language patterns or links. Systems like ChatSpamDetector use GPT-4 and have shown impressive detection abilities for phishing emails, achieving an accuracy of 99.70%. They also provide clear reasoning for their choices. These systems can spot sender spoofing, brand impersonation, and various social engineering tactics.

While LLMs greatly improve phishing detection, their ability to generate text also allows attackers to create very convincing phishing emails and realistic social engineering attacks. This leads to an ongoing competition, where advances in defense are quickly matched by new offensive tactics. LLMs can generate text that resembles human writing, which is both helpful and harmful. It helps detect subtle language cues in phishing emails, but attackers can use this same skill to create more believable, personalized, and evasive phishing messages.

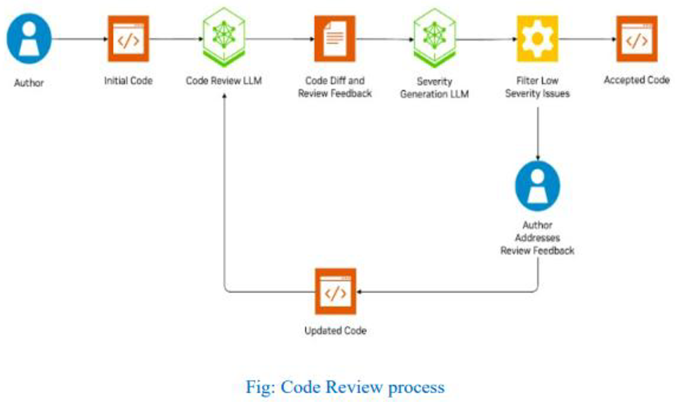

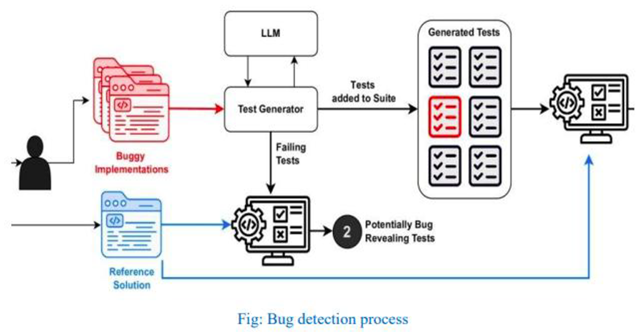

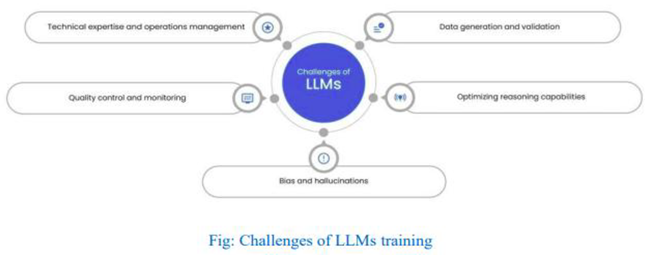

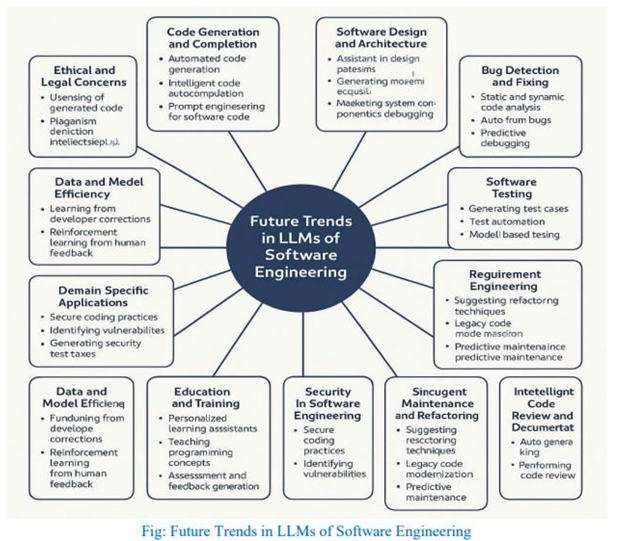

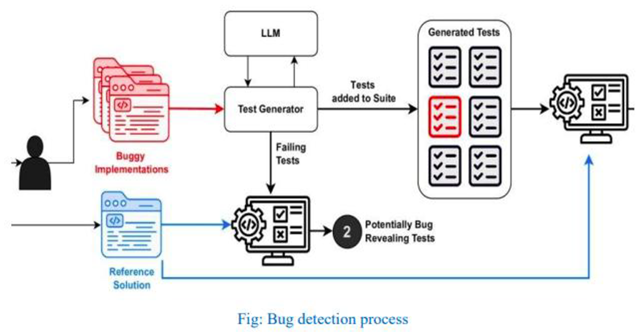

This means the effectiveness of LLM-based defenses is not fixed. It requires constant updates to keep up with changing AI-driven attacks.