1. Introduction

Recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC) has a very poor prognosis because of its rapid progression and resistance to treatment [

1]. The treatment goal for patients with R/M HNSCC is not only to prolong their life but also to improve their quality of life (QOL). The head and neck contain organs that have a substantial impact on a patient’s QOL, such as those involved in speech, swallowing, and breathing. Local control of head and neck cancer is thought to not only maintain patients’ QOL but also prolong their survival. Therefore, photoimmunotherapy (PIT) was developed for such local control.

PIT is a cancer treatment method that has attracted attention in recent years. It involves the use of drugs containing photosensitive substances and laser light of a specific wavelength. These drugs are a conjugate of IR700, a photosensitive substance, and antibodies that bind to molecules specifically expressed in the treatment targets [

2]. IR700 has a high absorption rate for red light with a wavelength of 690 nm. When red light is illuminated on the antibody–IR700 conjugate bound to the target molecule, the shape of the conjugate changes, which induces physical stress on the cell membrane. This increases transmembrane water flow, causing extracellular fluid to flow into the cell and leading to cell rupture due to swelling [

3]. Cell rupture leads to necrosis of cancer cells [

4].

The first clinical trial of PIT for head and neck cancer (HN-PIT) was a phase I/IIa trial (the RM-1929-101 trial) conducted in the United States in 2015 [

5]. Its aim was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PIT in patients with unresectable, locally recurrent head and neck carcinoma. In part 1 of the trial, the optimal dose was determined as 640 mg/m

2. In part 2, the trial revealed a complete response (CR) rate of 13.3%, partial response (PR) rate of 30.0%, and unconfirmed overall response rate (ORR) of 43.3%. The disease control rate (DCR), including that of patients with stable disease (SD), was 80.0%. In 2018, a phase I trial was performed with three Japanese participants [

6]. Its purpose was to confirm the safety of PIT for Japanese patients. Based on its results, it was added to the Sakigake Fast Track Review System for unresectable locally advanced or locally recurrent head and neck cancer (LA/LR-HNC) in Japan, and PIT received insurance coverage in 2021. HN-PIT has received conditional early approval, and phase III trials are currently underway. As of 2025, four years have passed since insurance approval in Japan, and real-world data (RWD) have been reported [

7,

8,

9]; however, those reports were limited to data from single institutions, and no large-scale RWD on HN-PIT are available. Therefore, reports of larger numbers of HN-PIT cases are warranted. The aim of this multicenter observational study was to retrospectively evaluate the effectiveness and safety of HN-PIT. We discovered that it has satisfactory effectiveness and an acceptable safety profile.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

In this multicenter, retrospective, observational study, we analyzed patients’ medical records. The study was conducted in compliance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. As this was a multicenter study, it was conducted with the permission of the head of the research institution to which the investigator belonged, after a batch review. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tokyo Medical University and the International University of Health and Welfare (approval nos.: T2024-0065 and 5-24-63).

2.2. Patients

We included patients aged 20–100 years who were treated with HN-PIT for unresectable LA/LR-HNC from January 1, 2021, to August 31, 2024, in the Tokyo Medical University Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, as well as in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, and Head and Neck Oncology Center, of the International University of Health and Welfare, Mita Hospital. Patients who requested not to participate in the study were excluded.

2.3. Outcomes and Assessments

The primary endpoint was time to treatment failure (TTF), defined as the time from the start date of HN-PIT until treatment was discontinued for any reason, including exacerbation of the underlying disease, adverse treatment events, and death from any cause. The secondary endpoints were the ORR, overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and rate of adverse events (AEs). OS was calculated from the start date of HN-PIT to the date of death from any cause. PFS was calculated from the start date of HN-PIT to the date of objective disease progression or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. The ORR was determined as the rate of the best overall response (BOR). The tumor response was assessed according to the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors version 1.1 [

10]. The tumor–node–metastasis classification was determined according to the seventh edition of the Union for International Cancer Control criteria [

11]. AEs were assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 [

12].

2.4. Photoimmunotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer

The treatment involved the intravenous administration of 640 mg/m2 of cetuximab sarotalocan sodium over a period of at least 2 h, followed by laser illumination of the target lesion 20–28 h later. Cetuximab sarotalocan sodium is an antibody–photosensitizer conjugate that combines cetuximab, a chimeric anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody (immunoglobulin G1), with the photosensitizer IR700. Owing to IR700, the conjugate is unstable upon exposure to light. Therefore, the illuminance must be limited to 120 lx or less during preparation of the medication. Accordingly, the infusion bag must remain covered with a special light-shielding cover.

The target lesion was illuminated with red laser light at a wavelength of 690 nm, using the BioBlade laser system (Rakuten Medical KK). The laser system includes photodynamic therapy semiconductor lasers (BioBlade laser, BioBlade laser WR) and probes (a frontal diffuser and side-fire diffuser for superficial illumination, and a cylindrical diffuser for tissue illumination). A diffuser guide tube was used as an auxiliary device for surface illumination, and a needle catheter was used for intra-tissue illumination. The illumination area was set with a safety margin of approximately 5–10 mm, depending on the location and size of the target lesion. The diffuser type was selected according to the illumination area, and either or both surface illumination or internal tissue illumination was used.

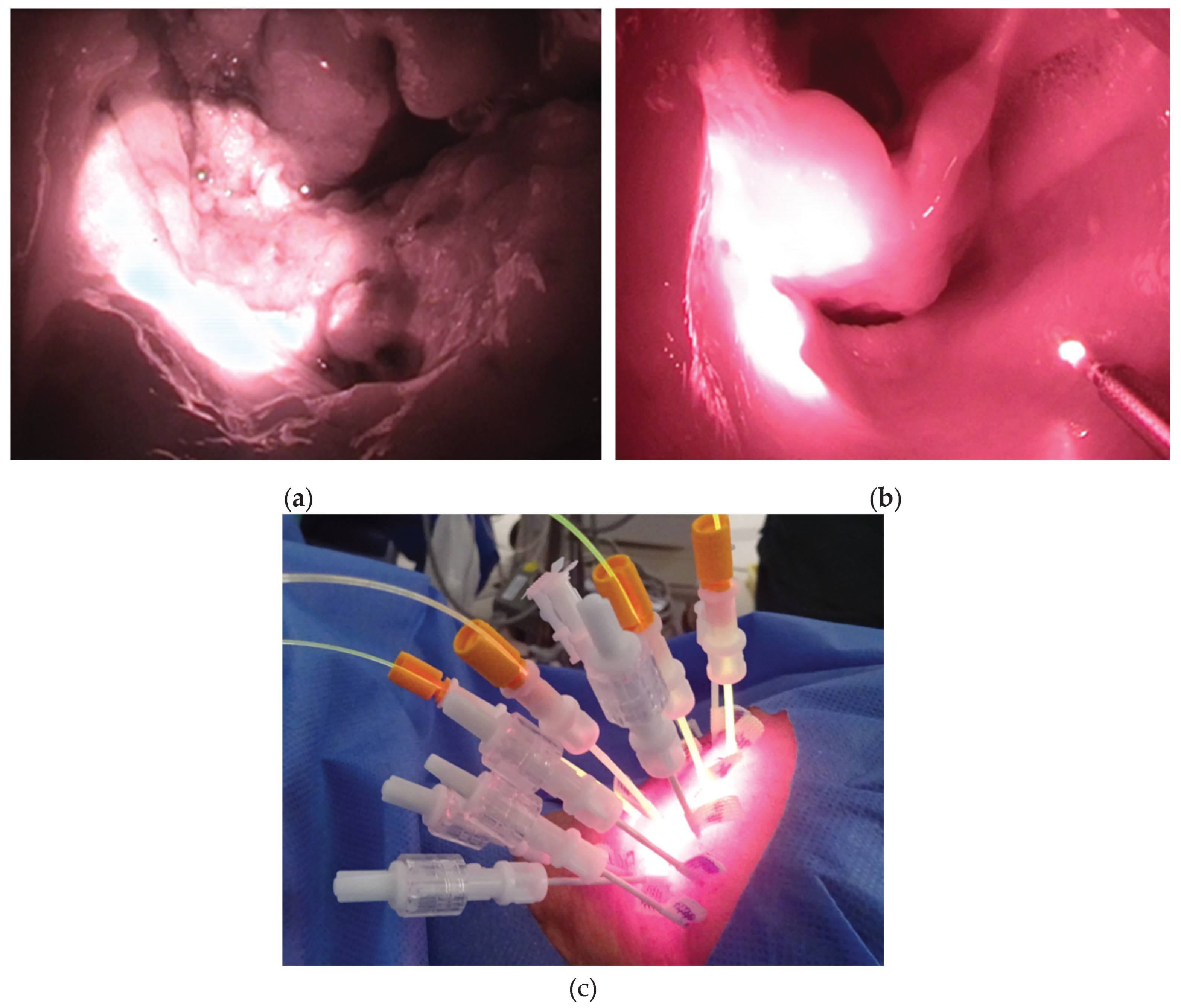

A surface illumination laser light was used for superficial lesions. Depending on the laser equipment and output port used, the laser light was illuminated in a circular pattern from the front or side, within a range of 7–38 mm in diameter (

Figure 1A,B). The illumination distance was approximately 1.7 times the spot diameter, and the target lesion was illuminated perpendicularly. The illumination intensity (laser output density) was fixed at 150 mW/cm

2, the laser illumination time per session was 5 min 33 s, and the light dose was 50 J/cm

2. Illumination was performed in multiple sessions according to the required illumination area and working space. The cylindrical diffuser emits laser light in a cylindrical shape (

Figure 1C). It was inserted into the needle catheter after the tissue was punctured. The cylindrical diffuser had a fluence rate of 400 mW/cm, and the laser illumination time per session was 4 min 10 s with a light dose of 100 J/cm. Needle catheters were available in three lengths: 50, 70, and 100 mm. The appropriate length was selected based on the location of the target lesion and the approach to be used. The necessary number of punctures was performed, taking into consideration the cylindrical illumination area of each needle. Depending on the state of the illuminated lesion, HN-PIT can be repeated for up to four cycles, which has proven safe in a clinical trial [

5], with an interval of at least four weeks between cycles. Even if PD is observed after HN-PIT, HN-PIT can be repeated if further local control is needed and the lesion is accessible to the laser.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The TTF, OS, and PFS were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR [

13] and IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Japan, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Patients

During the study period, 40 patients underwent HN-PIT for unresectable LA/LR-HNC. As none of them declined participation, all 40 patients were included.

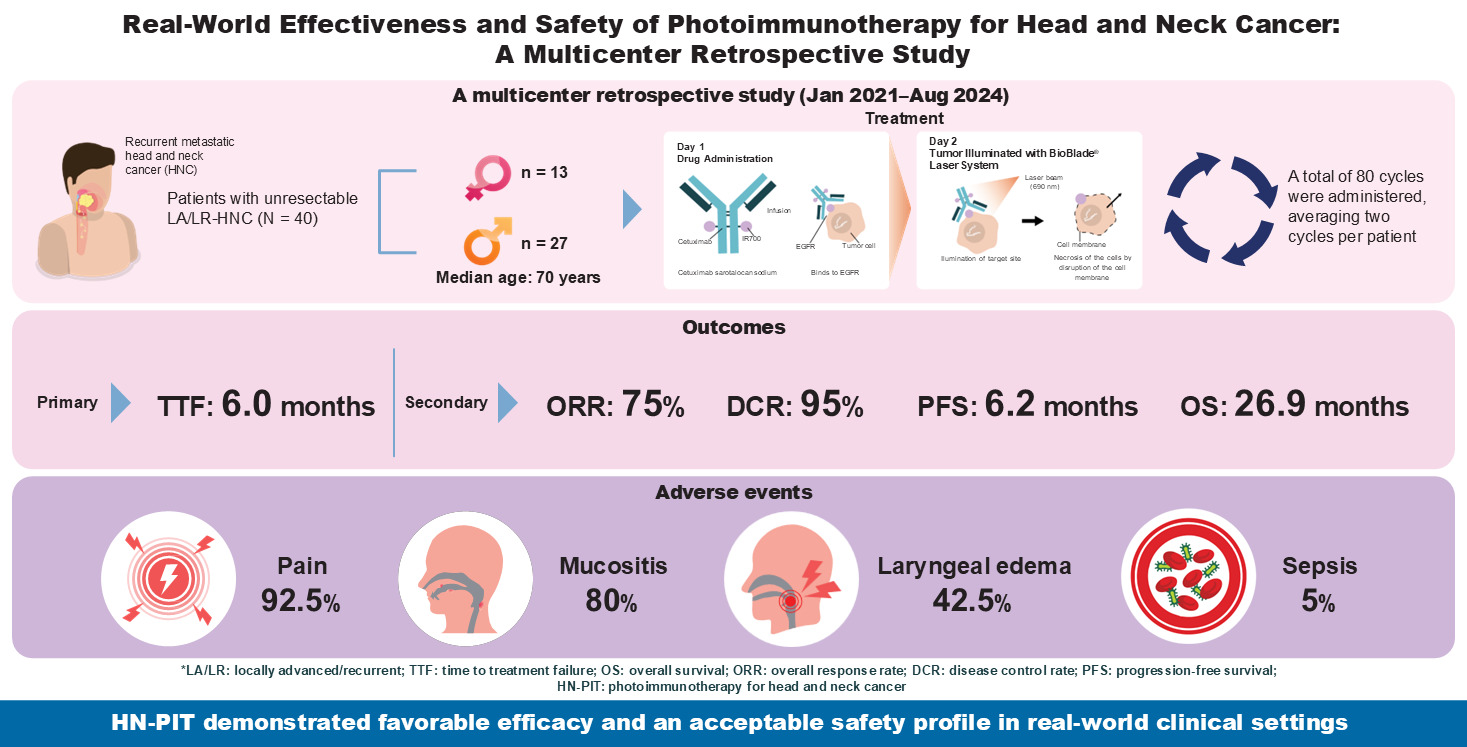

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics. The median age of the patients was 70 years (range, 36–87 years), and 27 of them were males (67.5%). The most common Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status was 0, observed in 32 patients (80%). The most common primary tumor site was the oral cavity (17 patients, 42.5%). This was followed by the oropharynx (seven patients, 17.5%) and nasopharynx (five patients, 12.5%). Eighty cycles of illumination were performed, an average of 2 cycles per patient. The most common target site for laser illumination was the oropharynx (24 sites), followed by the oral cavity (16 sites). As the illuminated sites overlapped owing to progression of the lesions, all subsites of the illuminated areas were counted. Histological analysis revealed that 38 patients (95%) had squamous cell carcinoma. The two patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma were confirmed as EGFR-positive. Regarding treatment history, 31 patients (77.5%) had a history of surgery, and 38 (95.0%) had a history of radiation therapy. In the two patients without a history of radiation therapy, both the primary site and the target lesion were located in the oral cavity.

3.2. Effectiveness

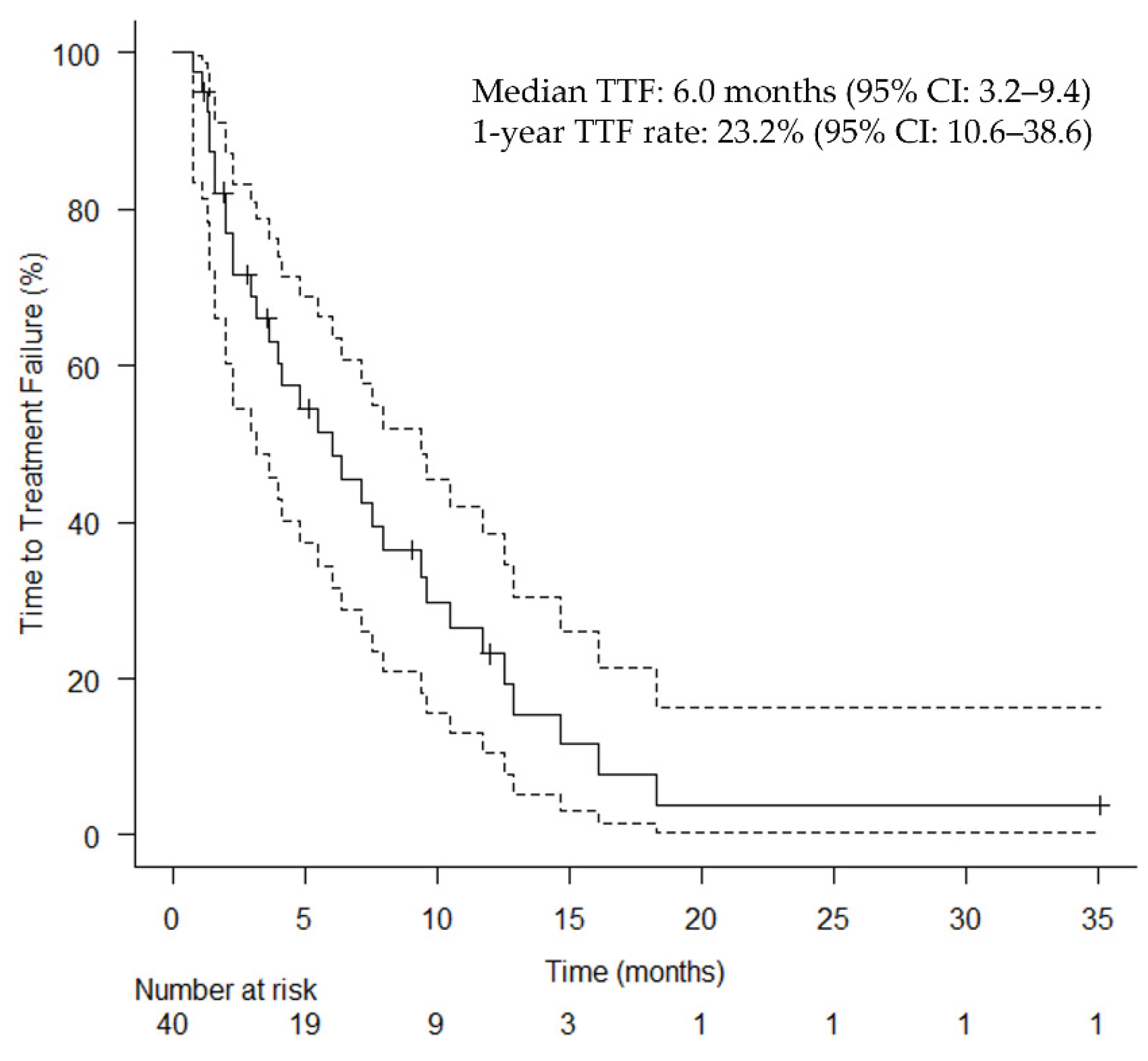

Table 2 summarizes the effectiveness of HN-PIT. The median follow-up duration was 9.86 months (range: 0.8–36.2 months). The median TTF for the primary endpoint was 6.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.2–9.4 months;

Figure 2).

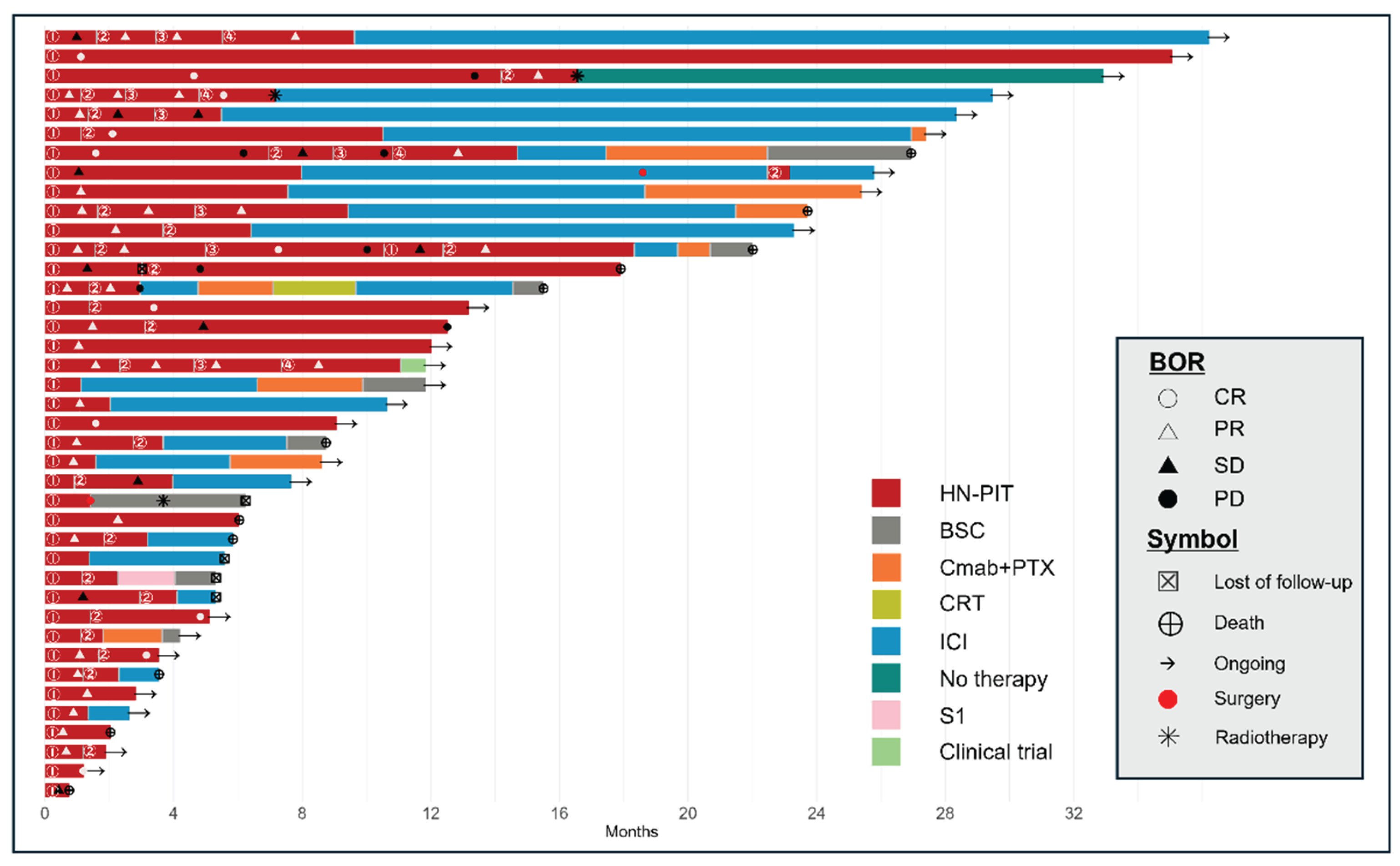

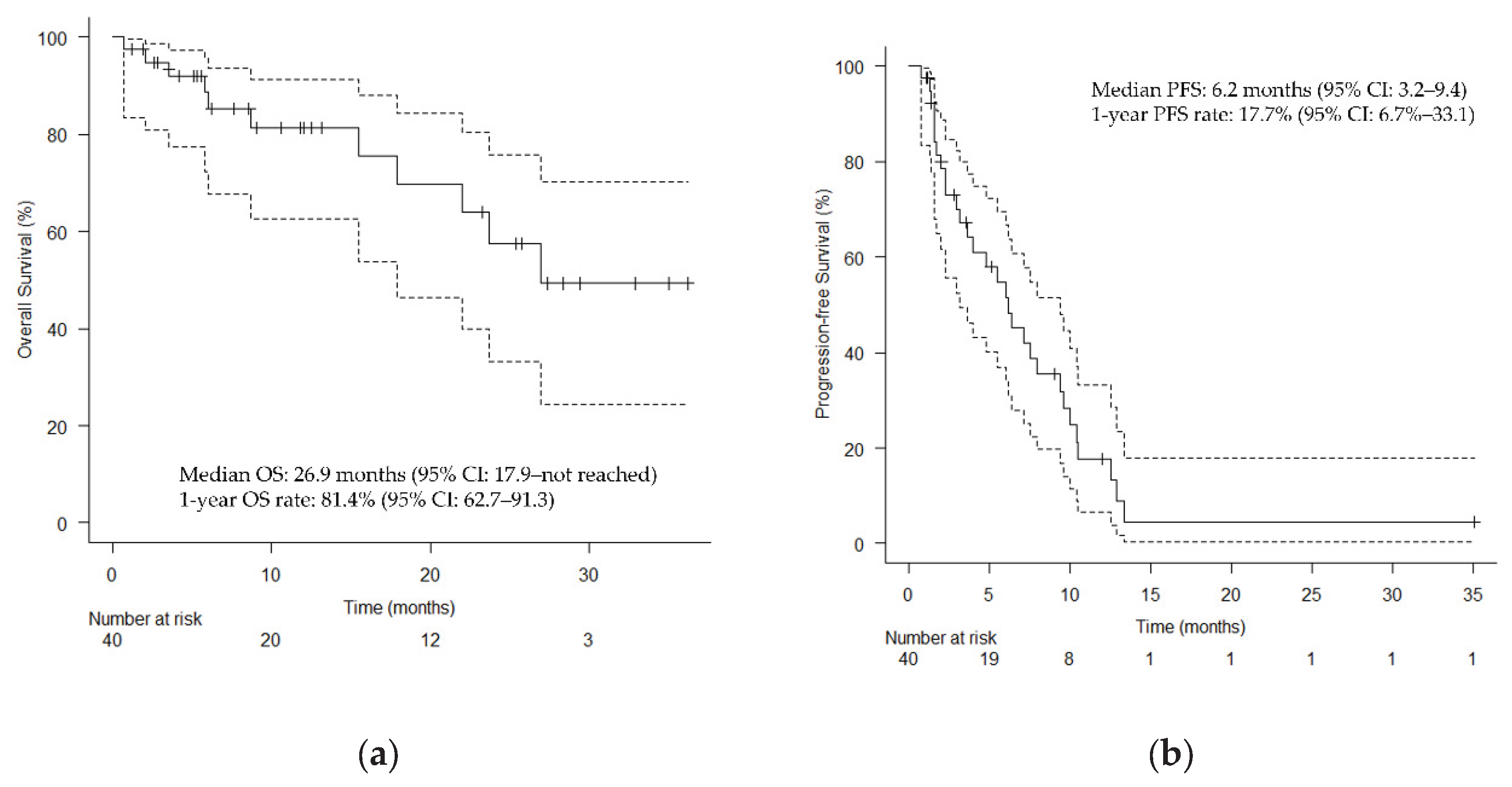

Figure 3 shows the clinical course of all patients who underwent HN-PIT, including sequential treatment, as a swimmer plot. The median OS was 26.9 months (95% CI: 17.9 months–not reached;

Figure 4A), and the median PFS was 6.2 months (95% CI: 3.2–9.4 months;

Figure 4B). The BOR is also summarized in

Table 2: the ORR was 75.0% and DCR was 95.0%.

Table 2. Photoimmunotherapy for Head and Neck Cancer.

CI, confidence interval.

Table 2.

Best overall response.

Table 2.

Best overall response.

| Clinical Outcomes |

No. |

% |

| Objective response rate |

30 |

75.0 |

| Disease control rate |

38 |

95.0 |

| Complete response |

11 |

27.5 |

| Partial response |

19 |

47.5 |

| Stable disease |

8 |

20.0 |

| Progressive disease |

2 |

5.0 |

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of time to treatment failure. Vertical lines show censored events. CI, confidence interval; TTF, time to treatment failure.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of time to treatment failure. Vertical lines show censored events. CI, confidence interval; TTF, time to treatment failure.

Figure 3.

Swimmer plot of the clinical course of patients who underwent photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer. Time to response and duration of survival (red portion of bar graph). Each bar represents a single patient, with the length of the bar corresponding to overall survival. HN-PIT, photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer; BOR, best overall response; BSC, best supportive care; Cmab, cetuximab; CR, complete response; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; PTX, paclitaxel; SD, stable disease; S1, tegafur-gimeracil-oteracil.

Figure 3.

Swimmer plot of the clinical course of patients who underwent photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer. Time to response and duration of survival (red portion of bar graph). Each bar represents a single patient, with the length of the bar corresponding to overall survival. HN-PIT, photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer; BOR, best overall response; BSC, best supportive care; Cmab, cetuximab; CR, complete response; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; PTX, paclitaxel; SD, stable disease; S1, tegafur-gimeracil-oteracil.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves. (a) Overall survival; (b) Progression-free survival. Vertical lines show censored events. CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves. (a) Overall survival; (b) Progression-free survival. Vertical lines show censored events. CI, confidence interval; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

3.3. Safety

All AEs are listed in

Table 3. The most common AE was pain, which occurred in 37 patients (92.5%), and grade 3 pain occurred in five patients (12.5%). Mucositis occurred in 32 patients (80.0%), grade 3 mucositis occurring in 3 patients (7.5%). Hemorrhages were observed in 31 patients (77.5%); however, no grade 3 or higher hemorrhages were observed. Sepsis was observed in two patients (5.0%; grades 4 and 5). Laryngeal edema was observed in 17 patients (42.5%), 4 with grade 4 edema (10.0%).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of HN-PIT. Forty patients underwent 80 HN-PIT cycles in total. This was the largest real-world study to date, in terms of patients and treatment cycles. In regard to effectiveness, the median TTF was 6.0 months, the median OS was 26.9 months, the median PFS was 6.2 months, the ORR was 75%, and the DCR was 95%, all of which were favorable outcomes. The level of safety was also within an acceptable range.

In the phase 1/2 RM-1929-101 trial [

5], the unconfirmed ORR was 43.3% and the DCR was 80.0%. These rates were more favorable in our study. However, we evaluated the ORR by using the BOR. When effectiveness is evaluated, one must consider that HN-PIT is a combination of systemic therapy and laser illumination, not systemic therapy alone. If the effectiveness is evaluated with a method used for systemic therapy, the results may differ from the actual therapeutic effect. Laser treatment is considered a type of surgery, as many lesions shrink temporarily. This raises the question of whether the ORR is an appropriate measure of the effectiveness of HN-PIT. Furthermore, as HN-PIT often allows for retreatment after PD, PFS is not considered an appropriate measure of its therapeutic effectiveness in clinical practice. Therefore, we selected TTF as the primary endpoint to evaluate the effectiveness of HN-PIT. Considering the specificity of HN-PIT, one might use the period during which disease control is possible through local treatment as a measure of its effectiveness. In cases in which progression is limited to the local area, retreatment with HN-PIT is possible. As shown in the swimmer plot in

Figure 3, we determined that the most appropriate measure of effectiveness was the period during which local control was maintained with HN-PIT. The median PFS in this study 6.2 months was longer than the TTF (6.0 months), but this might have been due to the inclusion of patients who were switched to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment before PD in anticipation of the effects of immune activation via PIT. In basic experiments, the combination of PIT and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors was confirmed to enhance the overall anticancer effects via the activation of dendritic cells with tumor cells killed by PIT, which induced the production of inflammatory cytokines, stimulated T cells, primed antigen-specific T cells, and sustained memory T cell responses [

14,

15]. Therefore, this study included patients for whom curative treatment with PIT was not expected and who were switched to ICI before PD in anticipation of the effects of PIT on the tumor immune environment. This is the first study in which TTF was used as an effectiveness measure for HN-PIT. The results of this study may serve as a reference for future clinical studies on HN-PIT.

Case reports on the effectiveness and safety of HN-PIT have been published sporadically [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], but the two studies of RWD both contained fewer than 20 patients [

7,

25]. In the RM-1929-101 trial [

5], the median OS was 9.30 months (95% CI: 5.16–16.92 months), and the median PFS was 5.2 months (95% CI: 2.10–5.52 months). In this study, the median OS was 26.9 months and the median PFS was 6.2 months. Reasons for the favorable OS may include the possibility that the treatment was administered at an earlier stage of local recurrence than is possible in a clinical trial, as well as the effectiveness of the treatment performed after HN-PIT in this study. As shown in the swimmer plot in

Figure 3, PD-1 inhibitors were frequently selected as the next line of treatment, including for patients with PD despite PIT. Changes in the tumor immune environment caused by HN-PIT might have enhanced the effects of subsequent PD-1 inhibitor administration. Pembrolizumab has been reported as highly effective after HN-PIT in a small sample of patients [

18,

20].

HN-PIT is one treatment option for patients with unresectable LA/LR-HNC; systemic therapy is another. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines [

33], the first-line systemic therapeutic agents are the PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab. The efficacy of nivolumab was demonstrated in the CheckMate 141 trial [

34], with a median OS of 7.5 months (95% CI: 5.5–9.1 months) and a median PFS of 2.0 months (95% CI: 1.9–2.1 months). The efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy was evaluated in the KEYNOTE-048 trial [

35], in which the OS was 12.3 months (95% CI: 10.8–14.9 months) and the median PFS was 3.2 months (95% CI: 2.2–3.4 months) in patients with a combined positive score ≥ 1. As systemic therapy is not a curative treatment for HN-PIT, a complete comparison cannot be made with our study. However, considering not only the survival rate with systemic therapy but also the fact that tumor cells killed by HN-PIT activate local and peripheral T-cell responses, the administration of HN-PIT followed by PD-1 inhibitors after failure may be the best combination at this point.

Rakuten Medical KK is currently collecting surveillance data on post-marketing safety, and they have released an interim report on 157 patients as of Sep 2025. Common AEs included pain at the application site (53.5%), laryngeal edema (21.0%), dysphagia (14.0%) and facial edema (12.1%). In this study, 37 patients (92.5%) experienced pain, and 32 patients experienced mucositis (80.0%), accounting for a considerable proportion of AEs. Pain management is extremely important because it affects patients’ QOL. Our strategy is based on the concept of multimodal analgesia [

36]. Laryngeal edema is another AE that requires attention. It was observed in 17 patients (42.5%) in our study, 4 of whom experienced grade 4 edema. This has been reported even in cases in which the larynx was not the direct target of PIT [

22,

23]. As laryngeal edema can cause airway obstruction, it is a life-threatening AE; therefore, during HN-PIT, measures must be in place for airway management via tracheostomy. The most serious AE in this study was severe infection; one case each of grades 5 and 4 sepsis was observed. Another AE observed in this study, Lemierre’s syndrome, is triggered by infection [

24]. The patient who developed grade 5 sepsis originally had grade 1 mucositis but developed fatal septic shock. This patient’s general condition changed rapidly during hospitalization on the 23rd day after HN-PIT, indicating that careful management of infection after PIT is necessary. The average length of stay after HN-PIT is approximately 2 weeks. Even if a patient with mucositis is discharged in good general health, their health may suddenly deteriorate at home owing to the rapid spread of the infection. Therefore, the patient should be carefully observed for 1–2 months until their mucositis resolves.

The limitations of this study warrant discussion. First, the definition of unresectable head and neck cancer is unclear in terms of indications for HN-PIT. The factors contributing to a status of “unresectability” vary greatly not only among patients but also among surgeons and institutions. The treatment phase during which HN-PIT is administered is also a major factor. In other words, whether it was administered after local recurrence following local treatment or after PD following systemic therapy may affect OS. Furthermore, the treatment schedule of HN-PIT requires careful consideration, because HN-PIT can be administered for up to four cycles. Various opinions exist on this point. For example, some clinicians believe that only one cycle should be performed as curative treatment, and that further cycles may be considered if recurrence is confirmed. A long-term CR has been reported after a single cycle of HN-PIT [

37]. Another option is regular treatments (every 4 weeks) for residual tumors, similar to the strategy with systemic therapy. Furthermore, one might perform one cycle of HN-PIT and quickly transition to PD-1 inhibitor treatment in the hope of eliciting an immune response. In clinical practice, the strategy is determined on a case-by-case basis. Therefore, prospective studies on patient treatment courses and treatment objectives are desirable. Regarding the synergistic effects on the immune system, a phase 3 trial on combined pembrolizumab and HN-PIT as first-line treatment for recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (NCT06699212) is currently underway, and its results are highly anticipated.

The most important goal for physicians in the treatment of patients with head and neck cancer is to improve treatment outcomes without compromising their QOL [

7]. In this study, the median TTF for HN-PIT was 6.0 months. This is a very important endpoint. The treatment algorithm for head and neck cancer prioritizes local treatment, followed by systemic therapy if local treatment is inadequate owing to the appearance of unresectable lesions or distant metastases, and, finally, a transition to best supportive care. The addition of HN-PIT to the treatment strategy for head and neck cancer may extend survival time corresponding to the TTF with HN-PIT. Furthermore, HN-PIT may have a positive effect on subsequent systemic therapy. Ultimately, an extension of OS in patients with head and neck cancer is anticipated. A comparison of the effectiveness of conventional PD-1 inhibitors with that of PD-1 inhibitors after HN-PIT would be intriguing, and we are planning further studies to explore this topic. A comparison between HN-PIT and systemic therapy to determine which is better is meaningless. The most important aspect is the sequential use of all treatments and drugs within the treatment algorithm for head and neck cancer.

5. Conclusions

The effectiveness and safety of HN-PIT were evaluated in 40 patients (80 cycles in total). Regarding its effectiveness, the median TTF was 6.0 months, the median OS was 26.9 months, the median PFS was 6.2 months, the ORR was 75%, and the DCR was 95%. We considered TTF a useful endpoint to evaluate the effectiveness of HN-PIT. Safety was within acceptable levels, but grade 5 AEs were observed; therefore, careful follow-up after HN-PIT is important.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.O.; methodology, I.O.; validation, I.O., O.H., and Y.K.; formal analysis, O.H., Y.K., T.M., K.To., and K.Ts.; investigation, O.H., Y.K., T.M., K.To., and K.Ts.; data curation, I.O., O.H., Y.K., T.M., K.To., and K.Ts.; writing—original draft preparation, I.O.; writing—review and editing, I.O., O.H., Y.K., T.M., K.To., and K.Ts.; visualization, I.O., O.H., Y.K., T.M., K.To., and K.Ts.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committees of Tokyo Medical University and the International University of Health and Welfare (approval nos. and dates: T2024-0065, 30 Oct 2024; 5-24-63, 28 Jan 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because this study was based solely on existing information. Information about the study was made readily available to the research participants on each hospital’s website, and opportunities to decline participation were provided.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all patients and their families for participating in the study. We would also like to thank our medical team and the physicians who participated and collaborated with us in this study. Finally, we would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AE |

Adverse event |

| BOR |

Best overall response |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| CR |

Complete response |

| DCR |

Disease control rate |

| EGFR |

Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| HN-PIT |

Photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer |

| ICI |

Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| LA/LR-HNC |

Locally advanced or locally recurrent head and neck cancer |

| ORR |

Overall response rate |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| PD-1 |

Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| PIT |

Photoimmunotherapy |

| PR |

Partial response |

| QOL |

Quality of life |

| R/M HNSCC |

Recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| RWD |

Real-world data |

| SD |

Stable disease |

| TTF |

Time to treatment failure |

References

- Wiegand, S.; Zimmermann, A.; Wilhelm, T.; Werner, J.A. Survival after distant metastasis in head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res 2015, 35, 5499–5502. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitsunaga, M.; Ogawa, M.; Kosaka, N.; Rosenblum, L.T.; Choyke, P.L.; Kobayashi, H. Cancer cell-selective in vivo near infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting specific membrane molecules. Nat Med 2011, 17, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Ando, K.; Okuyama, S.; Moriguchi, S.; Ogura, T.; Totoki, S.; Hanaoka, H.; Nagaya, T.; Kokawa, R.; Takakura, H.; et al. Photoinduced ligand release from a silicon phthalocyanine dye conjugated with monoclonal antibodies: A mechanism of cancer cell cytotoxicity after near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. ACS Cent Sci 2018, 4, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K.; Takakura, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Ogawa, M. Changes in plasma membrane damage inducing cell death after treatment with near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. Cancer Sci 2018, 109, 2889–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cognetti, D.M.; Johnson, J.M.; Curry, J.M.; Kochuparambil, S.T.; McDonald, D.; Mott, F.; Fidler, M.J.; Stenson, K.; Vasan, N.R.; Razaq, M.A.; et al. Phase 1/2a, open-label, multicenter study of RM-1929 photoimmunotherapy in patients with locoregional, recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3875–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, M.; Okano, S.; Enokida, T.; Ueda, Y.; Fujisawa, T.; Shinozaki, T.; Tomioka, T.; Okano, W.; Biel, M.A.; Ishida, K.; et al. A phase I, single-center, open-label study of RM-1929 photoimmunotherapy in Japanese patients with recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol 2021, 26, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, I.; Okada, T.; Tokashiki, K.; Tsukahara, K. Quality-of-life evaluation of patients with unresectable locally advanced or locally recurrent head and neck carcinoma treated with head and neck photoimmunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, D.; Suzuki, H.; Beppu, S.; Terada, H.; Sawabe, M.; Hanai, N. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy for oropharyngeal cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirakawa, H.; Ikegami, T.; Kinjyo, H.; Hayashi, Y.; Agena, S.; Higa, T.; Kondo, S.; Toyama, M.; Maeda, H.; Suzuki, M. Feasibility of near-infrared photoimmunotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in unresectable head and neck cancer. Anticancer Res 2024, 44, 3907–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobin, L.H; Gospodarowicz, M.K.; Wittekind, C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 7th ed; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5. 2017. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_50 (accessed on 4 Feb 2025).

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, M.A.; Okamura, S.M.; De Magalhaes Filho, C.D.; Bergeron, D.M.; Rodriguez, A.; West, M.; Yadav, D.; Heim, R.; Fong, J.J.; Garcia-Guzman, M. Cancer-targeted photoimmunotherapy induces antitumor immunity and can be augmented by anti-PD-1 therapy for durable anticancer responses in an immunologically active murine tumor model. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2023, 72, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaya, T.; Friedman, J.; Maruoka, Y.; Ogata, F.; Okuyama, S.; Clavijo, P.E.; Choyke, P.L.; Allen, C.; Kobayashi, H. . Host immunity following near-infrared photoimmunotherapy is enhanced with PD-1 checkpoint blockade to eradicate established antigenic tumors. Cancer Immunol Res 2019, 7, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, I.; Okada, T.; Tokashiki, K.; Tsukahara, K. Photoimmunotherapy for managing recurrent laryngeal cancer cervical lesions: A case report. Case Rep Oncol 2022, 15, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omura, G.; Honma, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Shinozaki, T.; Itoyama, M.; Eguchi, K.; Sakai, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Watanabe, T.; Ohara, A.; et al. Transnasal photoimmunotherapy with cetuximab sarotalocan sodium: Outcomes on the local recurrence of nasopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, S.; Ehara, H.; Donishi, R.; Taira, K.; Fukuhara, T.; Fujiwara, K. Therapeutic host anticancer immune response through photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer may overcome resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Case Rep Oncol 2024, 17, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makino, T.; Sato, Y.; Uraguchi, K.; Naoi, Y.; Fukuda, Y.; Ando, M. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy for salivary duct carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx 2024, 51, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanyu, K.; Okamoto, I.; Tokashiki, K.; Tsukahara, K. A case of successful treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor after head and neck photoimmunotherapy. Case Rep Oncol 2024, 17, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibutani, Y.; Sato, H.; Suzuki, S.; Shinozaki, T.; Kamata, H.; Sugisaki, K.; Kawanobe, A.; Uozumi, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Hayashi, R. A case series on pain accompanying photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, I.; Okada, T.; Tokashiki, K.; Tsukahara, K. Two cases of emergency tracheostomy after head and neck photoimmunotherapy. Cancer Diagn Progn 2024, 4, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushihashi, Y.; Masubuchi, T.; Okamoto, I.; Fushimi, C.; Yamazaki, M.; Asano, H.; Aoki, R.; Fujii, S.; Asako, Y.; Tada, Y. A case of photoimmunotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma requiring emergency tracheostomy. Case Rep Oncol 2024, 17, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, M.; Okamoto, I.; Ito, T.; Tokashiki, K.; Tsukahara, K. Lemierre’s syndrome after head and neck photoimmunotherapy for local recurrence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol 2024, 17, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, D.; Shimabukuro, T.; Suzuki, H.; Beppu, S.; Terada, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hanai, N. Predictive factors for the efficacy of head and neck photoimmunotherapy and optimization of treatment schedules. Cancer Diagn Progn 2025, 5, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki, T.; Matsuura, K.; Okano, W.; Tomioka, T.; Nishiya, Y.; Machida, M.; Hayashi, R. Eligibility for photoimmunotherapy in patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent head and neck cancer and changes before and after systemic therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idogawa, H.; Shinozaki, T.; Okano, W.; Matsuura, K.; Hayashi, R. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with photoimmunotherapy. Cureus 2023, 15, e49315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushihashi, Y.; Masubuchi, T.; Okamoto, I.; Fushimi, C.; Hanyu, K.; Yamauchi, M.; Tada, Y.; Miura, K. Photoimmunotherapy for local recurrence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A case report. International Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery 2022, 11, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, S.; Ehara, H.; Donishi, R.; Morisaki, T.; Ogura, T.; Taira, K.; Fukuhara, T.; Fujiwara, K. Photoimmunotherapy with surgical navigation and computed tomography guidance for recurrent maxillary sinus carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx 2023, 50, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishikawa, T.; Terada, H.; Sawabe, M.; Beppu, S.; Nishikawa, D.; Suzuki, H.; Hanai, N. Utilization of ultrasound in photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer: A case report. J Ultrasound 2023, 28, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Kano, S.; Suzuki, M.; Hamada, S.; Idogawa, H.; Tsushima, N.; Ashikaga, Y.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Soyama, T.; Hida, Y.; et al. SlicerPIT: Software development and implementation for planning and image-guided therapy in photoimmunotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol 2024, 29, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, R.; Ito, T.; Kawabe, H.; Tsutsumi, T.; Asakage, T. Mixed reality-supported near-infrared photoimmunotherapy for oropharyngeal cancer: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2024, 86, 5551–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Head and Neck Cancers Version 2.2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck_blocks.pdf (accessed on 31 Jan 2025).

- Ferris, R.L.; Blumenschein, G., Jr.; Fayette, J.; Guigay, J.; Colevas, A.D.; Licitra, L.; Harrington, K.; Kasper, S.; Vokes, E.E.; Even, C.; et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtness, B.; Harrington, K.J.; Greil, R.; Soulières, D.; Tahara, M.; de Castro, G., Jr.; Psyrri, A.; Basté, N.; Neupane, P.; Bratland, Å.; et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2019, 394, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, I. Photoimmunotherapy for head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Auris Nasus Larynx 2025, 52, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, I.; Okada, T.; Tokashiki, K.; Tsukahara, K. A case treated with photoimmunotherapy under a navigation system for recurrent lesions of the lateral pterygoid muscle. In Vivo 2022, 36, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).