Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

19 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

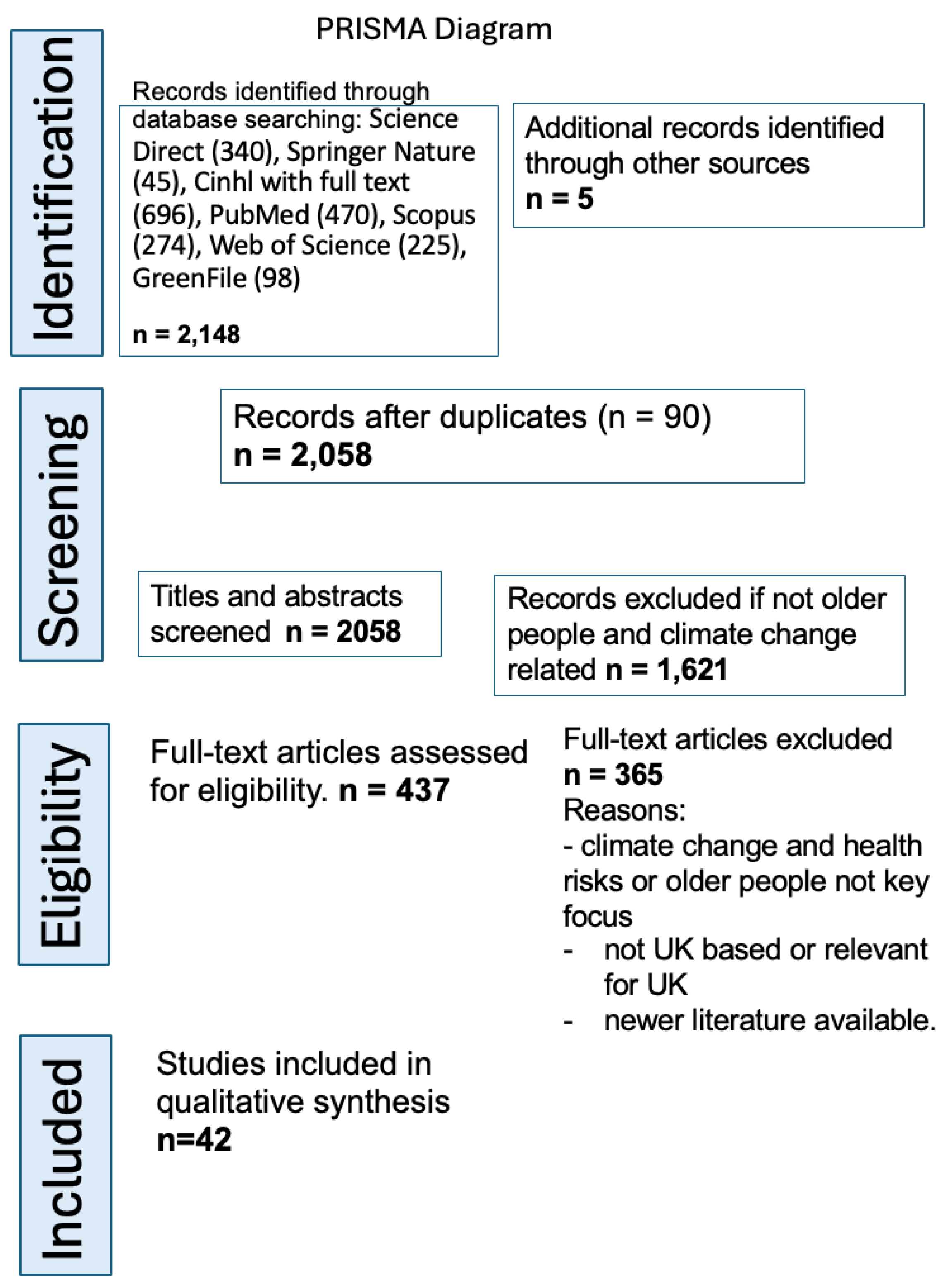

2. Method

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Michel, J.-P. Urbanization and Ageing Health Outcomes. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2020, 24, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageing-Better UK, ‘State of ageing in 2023’, 2023.

- World Health Organisation, ‘A Global Health Strategy for 2025–2028: executive summary.’, 2025, [Online]. Available: https://www.who. 0927.

- Montoro-Ramírez, E.M.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Parra, G.; López-Medina, I.M. Climate change effects in older people's health: A scoping review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B.; Harwood, R.H. The climate and biodiversity crises—impacts and opportunities for older people. Age and Ageing 2023, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U. Brofenbrenner, The ecology of human development : experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press, 1979.

- U. Brofenbrenner and P. Morris, ‘The ecology of developmental processes’, in Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development, 1998, pp. 993–1028.

- Rammal, M.; Berthier, E. Runoff Losses on Urban Surfaces during Frequent Rainfall Events: A Review of Observations and Modeling Attempts. Water 2020, 12, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousi, E.; Mela, A.; Tseliou, A. Nature-Based Urbanism for Enhancing Senior Citizens’ Outdoor Thermal Comfort in High-Density Mediterranean Cities: ENVI-met Findings. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, P.D.G.; Sánchez-González, D.; Peralta, L.P.G. Urban and Rural Environments and Their Implications for Older Adults’ Adaptation to Heat Waves: A Systematic Review. Land 2024, 13, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- G. Van der Waldt, ‘Constructing theoretical frameworks in social science research.’, J Transdiscipl Res Afr, 2024.

- Haq, G.; Gutman, G. Climate gerontology. Z. fur Gerontol. und Geriatr. 2014, 47, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antal, H.; Bhutani, S. Identifying Linkages Between Climate Change, Urbanisation, and Population Ageing for Understanding Vulnerability and Risk to Older People: A Review. Ageing Int. 2022, 48, 816–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation: National programmes for age-friendly cities and communities: a guide’, Age-Friendly World, 2021.

- Asiamah, N.; Bateman, A.; Hjorth, P.; A Khan, H.T.; Danquah, E. Socially active neighborhoods: construct operationalization for aging in place, health promotion and psychometric testing. Heal. Promot. Int. 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U. Brofenbrenner and S. Ceci, ‘Nature-nurture conceptualized in developmental perspective: a bioecological model.’, Psychol. Rev., no. 101 (4), 568-586., 1994.

- M. Marmot, J. M. Marmot, J. Allen, T. Boyce, P. Goldblatt, and J. Morrison, ‘Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On. Institute of Health Equity’, 2020.

- AgeUK, ‘Age friendly places’. Accessed: Apr. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/active-communities/age_friendly_places_guide.

- Dabelko-Schoeny, H.; Dabelko, G.D.; Rao, S.; Damico, M.; Doherty, F.C.; Traver, A.C.; Sheldon, M.; Castle, N.G. Age-Friendly and Climate Resilient Communities: A Grey–Green Alliance. Gerontol. 2023, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chief Medical Officer annual report 2021. GOV.UK’, 2021.

- Tang, D.; Xie, L. Whose migration matters? The role of migration in social networks and mental health among rural older adults in China. Ageing Soc. 2021, 43, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Smit, E.; Luck, J. Panel Survey Estimation of the Impact of Urbanization in China: Does Level of Urbanization Affect Healthcare Expenditure, Utilization or Healthcare Seeking Behavior? Chin. Econ. 2020, 54, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsager, R. Linking Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation: A Review with Evidence from the Land-Use Sectors. Land 2018, 7, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landauer, M.; Juhola, S.; Söderholm, M. Inter-relationships between adaptation and mitigation: a systematic literature review. Clim. Chang. 2015, 131, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Woolrych, Haq, and B. Latter, ‘Healthy Ageing in a Changing Climate: Creating Inclusive, Age-Friendly, and Climate Resilient Cities and Communities in the UK. Tables and Figures’, 2023.

- UK Government, Climate Change Committee, ‘UK Government & Climate UK Climate change Risk Assessment 2022. In UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 2022.’, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/61e54d8f8fa8f505985ef3c7/climate-change-risk-assessment-2022.

- UK Government Cabinet Office, ‘National Risk Register 2025’, UK Government, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.gov. 2025.

- UK Government, ‘Weather - Health Alerting (WHA) System’. Accessed: Dec. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.gov.

- K. A. Pillemer, J. K. A. Pillemer, J. Nolte, and M. T. Cope, ‘Promoting Climate Change Activism Among Older People’, Gener. San Franc. Calif, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 1–16, 2022.

- Paavola, J. Health impacts of climate change and health and social inequalities in the UK. Environ. Heal. 2017, 16, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, A.J.E.; Cunningham, S.J.K.; Morris, N.R.; Xu, Z.; Rutherford, S.; Binnewies, S.; Meade, R.D. Experimental research in environmentally induced hyperthermic older persons: A systematic quantitative literature review mapping the available evidence. Temperature 2023, 11, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Song, J.; Wang, C.; Chan, P.W. Realistic representation of city street-level human thermal stress via a new urban climate-human coupling system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniassadi, A.; Manor, B.; Yu, W.; Travison, T.; Lipsitz, L. Nighttime ambient temperature and sleep in community-dwelling older adults. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 899, 165623–165623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, S.R.; Feio, M.J. Benefits of urban blue and green areas to the health and well-being of older adults. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, N.; Sharifi, A. Who are marginalized in accessing urban ecosystem services? A systematic literature review. Land Use Policy 2024, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Agency, ‘Flooding in England: A National assessment of flood risk’, 2009.

- Thomas, M.; Pidgeon, N.; Whitmarsh, L.; Ballinger, R. Mental models of sea-level change: A mixed methods analysis on the Severn Estuary, UK. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 33, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, N.; Calabria, L.; Marks, E. A meta-ethnography of global research on the mental health and emotional impacts of climate change on older adults. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkling, B.; Haworth, B.T. Flood risk perceptions and coping capacities among the retired population, with implications for risk communication: A study of residents in a north Wales coastal town, UK. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101793–101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Meteorological Office, ‘UK climate projections: Headline findings’, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/metofficegovuk/pdf/research/ukcp/ukcp18_headline_findings_v4_aug22.

- Szewrański, S.; Świąder, M.; Kazak, J.K.; Tokarczyk-Dorociak, K.; van Hoof, J. Socio-Environmental Vulnerability Mapping for Environmental and Flood Resilience Assessment: The Case of Ageing and Poverty in the City of Wrocław, Poland. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2018, 14, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Saenz and C. E. Finch, ‘Air Pollution, Aging and Lifespan: Air Pollution Inside and Out Accelerates Aging’, in Encyclopedia of Biomedical Gerontology, S. I. S. Rattan, Ed., Oxford: Academic Press, 2020, pp. 203–213. [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, H.; Heaviside, C.; Taylor, J.; Picetti, R.; Symonds, P.; Cai, X.-M.; Vardoulakis, S. Assessing urban population vulnerability and environmental risks across an urban area during heatwaves – Implications for health protection. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 610-611, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Christensen, ‘A Critical Reflection of Bronfenbrenner’s Development Ecology Model’, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, N.; Conduah, A.K.; Danquah, E.; Kouveliotis, K.; Eduafo, R. Abuse and Neglect of Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Index Generation, an Assessment of Intensity, and Implications for Ageing in Place. Adv. Gerontol. 2022, 12, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Johar, ‘Community-based heat adaptation interventions for improving heat literacy, behaviours, and Health Outcomes: A systematic review’, Lancet Planet. Health, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Ratwatte, P.; Wehling, H.; Kovats, S.; Landeg, O.; Weston, D. Factors associated with older adults' perception of health risks of hot and cold weather event exposure: A scoping review. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 939859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.R.; Tan, M.P. The contribution of assets to adaptation to extreme temperatures among older adults. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0208121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, L.; Ghio, D.; Grey, E.; Slodkowska-Barabasz, J.; Harris, P.; Sutcliffe, M.; Green, S.; Roberts, H.C.; Childs, C.; Robinson, S.; et al. Optimising an intervention to support home-living older adults at risk of malnutrition: a qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pr. 2021, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinna, S.; Longo, D.; Zanobini, P.; Lorini, C.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Baccini, M.; Cecchi, F. How to communicate with older adults about climate change: a systematic review. Front. Public Heal. 2024, 12, 1347935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, J.N.; Napier, S.; Neville, S.; Clair, V.A.W.-S. Impacts of older people’s patient and public involvement in health and social care research: a systematic review. Age and Ageing 2018, 47, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latter, B. Climate Change Communication and Engagement With Older People in England. Front. Commun. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prina, M.; Khan, N.; Khan, S.A.; Caicedo, J.C.; Peycheva, A.; Seo, V.; Xue, S.; Sadana, R. Climate change and healthy ageing: An assessment of the impact of climate hazards on older people. J. Glob. Heal. 2024, 14, 04101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, P.; Buffel, T. Translating Research into Action: involving older people in co-producing knowledge about age-friendly neighbourhood interventions. Work. Older People 2018, 22, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmistu, S.; Kotval, Z. Spatial interventions and built environment features in developing age-friendly communities from the perspective of urban planning and design. Cities 2023, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huertas, D.S.; Rowe, J.W.; Finkelstein, R.; Carstensen, L.L.; Jackson, R.B. Rethinking the urban physical environment for century-long lives: from age-friendly to longevity-ready cities. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Buskens et al., Healthy Ageing: Challenges and Opportunities of Demographic and Societal Transitions . In Older People: Improving Health and Social Care: Focus on the European Core Competences Framework; B. L. Dijkman, I. Mikkonen, and P. F. Roodbol, Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 9–31. [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Roy, S.; Aloni, O.; Keating, N.; Heyn, P.C. A Scoping Review of Research on Older People and Intergenerational Relations in the Context of Climate Change. Gerontol. 2022, 63, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Date | Country of Origin | Author | Type of Study | Air Pollution | Flooding | Extreme Weather | Healthy/Unhealthy Ageing | Built Env/Infrastructure | Community/Social Engagement | Climate Gerontology | Communication with older people | PPCT Model Variable |

| 2021 | Israel, US, Canada, UK, South Africa | Ayalon et al |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | Context Macrosystem |

|||||

| 2023 | Israel, UK, South Africa | Ayalon et al | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | X | Context Chronosystem |

|||

| 2019 | The Netherlands | Buskens et al | Longitudinal | X | Context Chronosystem |

|||||||

| 2023 | UK | Davies & Harwood | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | X | X | Time | ||

| 2014 | UK and C anda | Haq & Gutman | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Context Chronosystem |

|

| 2022 | UK | Latter |

Cross-sectional | X | X | X | Proximal Processes | |||||

| 2024 | UK | Marinova et al | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | Context Microsystem |

||||

| 2024 | Spain | Montoro-Ramírez et al | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | X | X | Context Exosystem |

||

| 2017 | UK | Paavola |

Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | X | X | Context Microsystem |

||

| 2021 | UK | Payne et al | Cross-sectional | X | X | Context Microsystem |

||||||

| 2024 | UK USA Canada & Switzerland | Prina et al | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Context Chronosystem |

|

| 2023 | UK, Denmark, Ghana | Asiamah et al | Longitudinal | X | X | X | Context Mesosystem |

|||||

| 2022 | Ghana, Italy | Asiamah et al | Cross-sectional | X | X | X | Context Mesosystem |

|||||

| 2024 | UK The Netherlands, Russia | Bobrova et al | Longitudinal | X | Context Microsystem |

|||||||

| 2024 | USA | Dabelko-Schoeny et al | Longitudinal |

X | X | X | X | X | Context Macrosystem |

|||

| 2024 | Canada | Doiron et al |

Cross-sectional |

X | X | X | Context Macrosystem |

|||||

| 2024 | Bangladesh, Japan, Lebanon | Haque & Sharifi | Longitudinal | X | X | X | Context: Exosystem |

|||||

| 2022 | China, USA | Huang,et al |

Cross-sectional |

X | X | X | Context: Microsystem Personal Characteristics |

|||||

| 2020 | Switzerland | Michel |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | X | X | X | Context: Chronosystem Time |

||

| 2023 | Estonia, USA | Salmistu & Kotval | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | Proximal Processes | ||||

| 2024 | Portugal | Serra & Feio | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | X | X | Personal Characteristics | ||

| 2015 | The Netherlands | Van Dijk et al | Cross-sectional | X | X | X | x | Proximal Processes | ||||

| 2021 | The Netherlands, Poland, UK | van Hoof et al |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | X | Context: Macrosystem |

||||

| 2021 | USA | Wang et al |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Context Chronosystem |

|

| 2017 | China | Wang et al |

Cross-sectional |

X | X | Context: Microsystem |

||||||

| 2015 | UK | Webb |

Longitudinal |

X | X | Personal Characteristics | ||||||

| 2024 | Denmark, UK, Germany | Poulsen et al |

Cross-sectional |

X | X | Context: Microsystem |

||||||

| 2021 | China, Canada, USA, Norway, Germany | Yin et al |

Cross-sectional |

X | X | Time | ||||||

| 2020 | USA | Saenz & Finch |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | Context: Microsystem |

|||||

| 2024 | Spain | Grela et al |

Longitudinal | X | X | X | Time | |||||

| 2023 | USA | Baniassadi et al |

Longitudinal |

Context: Microsystem |

||||||||

| 2022 | UK | Ratwatte et al |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | X | Context: Exosystem |

||||

| 2017 | The Netherlands, Hong Kong, Austrailia, Poland, | van Hoof et al |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | Context: Microsystem |

|||||

| 2020 | Canada | Kafeety et al | Longitudinal | X | X | X | X | Proximal Processes | ||||

| 2018 | UK | Nunes |

Cross-sectional |

X | X | X | X | Context: Microsystem Proximal Processes |

||||

| 2020 | UK | Walking & Haworth | Cross-sectional |

X | X | X | Proximal Processes | |||||

| 2018 | Poland | Szewrański et al | Cross-sectional | X | X | X | X | X | Context: Macrosystem |

|||

| 2015 | UK | Thomas et al |

Cross-sectional | X | X | X | Context: Macrosystem Time |

|||||

| 2024 | Hungary, Spain, The Netherlands, Denmark, Italy, UK, Portugal, Germany, Greece, Slovenia | Buzasi et al |

Cross-sectional |

X | X | Context: Macrosystem |

||||||

| 2024 | Italy | Pinna et al |

Longitudinal |

X | X | X | Context: Microsystem Proximal Processes |

|||||

| 2018 | New Zealand | Baldwin et al | Longitudinal | X | X | Proximal Processes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).